Abstract

Inspired by information sensing, storage, and processing capabilities of natural systems, mechanical computing built upon intelligent matters is emerging toward directly perceiving environmental changes and making autonomous decisions. However, challenges remain in achieving general-purpose mechanical computing architecture due to the trade-off between programmability and scalability. Here, we present a mechanical programmable gate array, a scalable architecture integrating dynamic activation mechanisms for general-purpose computing. By mapping local factored Quine-McCluskey logic functions onto bistable origami switch-based logic units and embedding conductive networks, we create low-redundancy, high-stability logic modules. A robotic activation mechanism, guided by magnetic instructions, dynamically configures the logic array for all input combinations, ensuring complete programmability and scalability. The architecture also interfaces with storage units for iterative processes like function reuse and neural network weight updates. With programmability, scalability, and adaptability, this approach lays the foundation for decision-making materials with applications spanning distributed edge computing and embodied intelligent robotics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With advancements in additive manufacturing, materials science, and structural engineering1,2,3,4, mechanical computing capable of directly sensing changes in the external environment and making autonomous decisions through built-in computational functionalities is leading a unique paradigm for intelligent matters5,6,7,8,9. Significant progress has been achieved in specific mechanical computing functionalities and small-scale computational tasks, including bistable memory10,11,12, multistable memory13,14,15,16, reprogrammable logical functions7,17, mechanical integrated circuit materials8,18,19, in-memory mechanical computing20, and mechanical logic embedded robots3,9,21.

General-purpose computing enables users to program and scale resources as needed, allowing the flexible execution of diverse computational tasks without being restricted to application-specific custom hardware and offering a high-level platform for prototyping computational machines. Electronic22, quantum23,24, and DNA25 computing have evolved from task-specific to general-purpose, enlightening the need for mechanical systems to develop general-purpose capabilities that integrate programmability and scalability to enhance adaptability and autonomy in complex environments22,26. Programmability allows dynamic adjustment of logical behavior, providing flexibility and adaptability. Scalability enhances computational power by handling large-scale tasks through resource addition and distributed computing. Mechanical systems currently rely on mechanically reconfigurable structures for programmability7,17, but scalability is limited by assembly complexity and damping effects27. Embedding conductive networks in mechanical metamaterials can integrate strain-gated switches, enabling monolithic metamaterial circuits for scalable functionalities8,28. However, switch coupling complicates independent activation, hindering programmability.

Here, we develop a scalable and programmable mechanical integrated circuit architecture for general-purpose mechanical computing. The architecture consists of an array of spatially discrete logical modules that are on-demand accessible and internally routable. The basic logic unit, composed of multiple bistable origami switches, is designed to enable a low-redundancy and scalable integrated circuit network. Drawing inspiration from the lookup table (LUT), the fundamental building block of a field-programmable gate array (FPGA), we assemble basic logic units to represent all possible input combinations (minterms), forming an array of configurable logic modules (LMs). Programmability is achieved through an origami-controlled addressing robot with input stimulus that sequentially configures the outputs of all minterms in response to magnetic instructions, thereby enabling dynamic reconfiguration of the circuit array and realizing a mechanical programmable gate array (MPGA). Furthermore, the MPGA interfaces with storage units for computational reuse, supporting complex functionalities and neural network updates. This general-purpose architecture, with programmability, scalability, and reusability, promises autonomous decision-making and environment interaction for robotics, edge computing, and embodied intelligence.

Results

The proposed MPGA computational architecture supports both low-redundancy application-specific computing and general-purpose computing. Notably, any mechanical computing system that satisfies the following three conditions can inherently implement the MPGA computational architecture:

-

1)

Embedded Conductive Networks: each unit incorporates embedded wires to form switching circuits, thereby constructing the foundational framework of integrated circuits (IC).

-

2)

Bistability: units exhibit bistable characteristics, enabling the storage of output results corresponding to various input combinations, which establishes the basis for programmability.

-

3)

Activating Mechanism: the system includes an addressing robot capable of sequentially activating specific spatial input combinations (minterms) in response to external environmental instructions. Instructions can be software-generated to reconfigure the MPGA’s function.

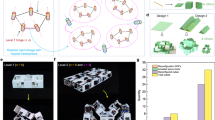

To satisfy the above conditions, we employ bistable Kresling origami as the mechanical switching structure for both the integrated circuit and its activation control. The bistability of Kresling origami imparts non-volatility to the mechanical computing system, enabling the switching state to be preserved without continuous energy input, thereby facilitating data storage. Moreover, the intrinsic chirality of the Kresling structure allows for the implementation of basic logic gates such as Buffer and Not. To reduce redundancy, we embed i switches within a single Kresling origami to construct Buffer(i) or Not(i), such as Buffer(4) or Not(4), where the i is omitted when i = 1 (Fig. 1a). In application-specific computing, this design is particularly efficient for Boolean expressions with identical literals. For example, implementing f = AB + ACD + BCD with a traditional transistor-based system requires a separate unit for each literal occurrence, totaling eight units, while our origami-based system reuses a single unit for each identical literal (A, B, C, D), reducing the required units to four (Fig. 1b).

a Conceptual schematic of the bistable origami switches. Blue represents left-handed origami, and pink represents right-handed origami. b Schematic diagram of low redundancy for application-specific computing functions. The Boolean function f = AB + ACD + BCD requires eight units to be implemented through transistor-based switches, whereas it only requires four units through origami bistable switches (OBS). c Schematic diagram of the programmability, scalability, and reusability of MPGA. Programmability is achieved through the routing of the embedded conductive networks and the addressing of the mobile robot. Gray squares represent deactivated logic modules, while cyan squares represent activated ones. Scalability can be achieved through the series-parallel and parallel computing of MPGA. Reusability is achieved through the mobility of the computing system driven by its own computational results.

To achieve general-purpose computing, we engineered an MPGA that integrates diverse functional LMs built with Buffer and Not units (Fig. 1c). Each functional module in the MPGA is assigned a unique address and pre-configured with internal routing paths, enabling parallel output of computational results. Guided by magnetic instructions, the origami-controlled addressing robot sequentially activates function modules at designated positions to realize dynamic reconfiguration of combinational logic operations. Provided that the functional modules cover all minterms (i.e., all possible input combinations), the MPGA can be programmed to implement arbitrary combinational logic functions. By serially, parallelly, or hierarchically stacking simple MPGA modules, the system achieves scalability in computational complexity under unlimited computational resources, supporting multi-input, multi-output operations. Once programmed for specific functions, the MPGA produces computational outputs that can autonomously direct a host robot on which it is mounted to designated coordinates, where the outputs are stored and retrieved along with new inputs in subsequent computational cycles, enabling the repeated execution of the specific functions using the same MPGA. This computational reuse methodology enables bitwise scalability of arithmetic operations under constrained resources, and supports iterative algorithms frameworks such as neural network weight update processes, establishing foundational capabilities for autonomous environmental adaptation and dynamic system interactions in physical domains.

Basic logic

Research has shown that the non-rigid origami structure Kresling exhibits exceptional programmability in force, stiffness, chirality, and stability29,30,31. Variations in geometric parameters and shapes of Kresling structures generate distinct energy landscapes, enabling monostable, bistable, and multistable configurations32,33,34,35. We therefore selected Kresling origami as our fundamental building unit, engineering its geometry for bistability. Notably, three-dimensional chiral bistable structures, including modular chiral origami, 3D auxetic materials, and tetra-chiral cylindrical tubes, can also serve as fundamental building units within our framework36,37,38. Based on the Kresling geometric model, we designed a bistable origami with a significant height difference between stable states, laying the groundwork for origami switches (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1.1). To further establish foundations for qualitative state transition, we established design maps through a theoretical mechanical model of Kresling origami that depict how polygon sides, initial height, and rotational angle influence critical torque (maximum restoring torque) and corresponding critical rotational angle during bistable transitions (Supplementary Note 2.3).

Due to high precision and repeatability11,39, magnetic actuation was selected to drive the state transition of the bistable chiral origami with a cap (Fig. 2a). For a magnetized cap, the induced magnetic torque under an in-plane magnetic field is given by: TB = V(M × B) = VMBsin(θ), where B represents the external magnetic field, V represents the volume of the magnetic cap, M represents its magnetization, θ represents the angular difference between the external magnetic field and cap magnetization direction. State transition occurs when the external magnetic torque exceeds the torque barrier (critical torque) of the bistable origami at the critical rotational angle Δφ in the folding/deploying process (Supplementary Note 2.3), resulting in a nonvolatile state after field removal. Taking the folding process of the right-handed origami unit as an example (Fig. 2b), the sustained magnetic torque exceeding the restoring torque throughout the whole process ensures successful State2-to-State1 transition, with an external magnetic field of B = 16 mT oriented at α = 100°. Experimental and analytical critical magnetic field strengths required for state transition across various external magnetic field directions are presented in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 24a.

a Schematic of the bistable chiral origami with a magnetic cap and its two stable states. b Torque required to fold the left-handed and right-handed origami and magnetic torque versus cap rotation angle |Δφ| at given magnetic field (α = 100°, B = 16 mT). The critical torque required for the left-handed origami to complete the transition is −2.98 N mm, with a critical rotation angle of −12.68°. For the right-handed origami, the critical torque is 2.78 N mm, with a critical rotation angle of 12.52°. Clockwise directions are defined as negative, and counterclockwise directions as positive. c Relationship between the magnitude and direction of the critical external magnetic field required for a right-handed origami-based Buffer unit to transition from stable state 2 to stable state 1. d Logical schematic and structural design of Buffer and Not units. Clockwise torque is indicated by pink arrows, and counterclockwise torque by blue arrows. e Relationship between the magnitude and direction of the critical external magnetic field required for two Buffer units to transition from the initial state (00) to the other three states. f Logical schematic, structural design, and Boolean response of the AND gate and OR gate under four states, with digital output represented by the conductivity of internal wires as indicated by the illumination of a series-connected LED. g Logical schematic, truth table, structural design, and Boolean response at Set and Reset states.

Based on this magnetically actuated bistable origami, we define the logic input of the unit structure as the direction of torque applied to the top surface of the origami, where clockwise and counterclockwise torques are defined as 1 and 0, respectively. To enable interaction with conventional computing systems and facilitate assembly or modularization, a conductive network is integrated into the origami logic unit, and the output is defined as the conduction state of the origami switch. Consequently, basic units composed of right- and left-handed origami structures can perform the logic functions of Buffer and Not gates, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. To quantify the unit’s robustness against interference, we tested the critical acceleration required for inter-well transitions of the Buffer unit in both stable states. Results indicate that at the most vulnerable frequency of 45 Hz (approximately half the natural frequency), the unit can withstand external disturbance accelerations up to 40 m/s2 (Supplementary Note 2.5). Moreover, we evaluated structural durability through cyclic compression tests and fatigue life simulation. Experimental results confirm negligible degradation after 10,000 compression cycles, with Goodman theory predicting a fatigue life of 6.58 × 107 cycles (Supplementary Note 2.4).

Based on switching circuit theory, fundamental logic gates can be constructed by connecting two basic units in series or parallel. To minimize magnetic interference, separators are placed between units for smooth state transitions. In a dual-unit system, magnetic caps have orthogonal magnetization directions (offset by 90°), ensuring distinct stable states under a uniform external magnetic field. By adjusting the external magnetic field’s direction and strength, simultaneous clockwise and/or counterclockwise torque can be applied. The differentiated magnetic response characteristics allow precise control of each unit’s state based on external magnetic field variations, enabling traversal of all input combinations. Upon reaching the critical magnetic threshold, the units collaboratively transition among states, such as from 00 to 01, 10, or 11 (Fig. 2e). Experimental results for other state transitions are in Supplementary Fig. 24b–d. Methods for controlling input states in systems with multi units are detailed in the Supplementary Note 3.3. By connecting two Buffer units in series (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Video 1), the embedded circuit conducts only when both switches are closed, achieving the AND function with the logical expression Q = AB. An OR gate with the logical expression of Q = A + B is similarly implemented by the parallel connection of two Buffer units, conducting when either switch is closed. LED lights controlled by switching circuits visually represent output results, with on and off states corresponding to output values of 1 and 0, respectively. Implementation for NAND, NOR, XOR, and XNOR logic gates is in Supplementary Note 6.1 and Fig. 27.

With the structural bistability, the system maintains its stable states even after the magnetic field is removed, rendering it suitable for nonvolatile multi-bit information memory. This property allows the Buffer unit to function as a basic sequential logic element—a D-latch, capable of storing 1 bit of data. Additionally, we explored another fundamental sequential logic element: the SR latch. As shown in Fig. 2g, an additional magnetic cap is integrated at the base of the origami and mounted on a rotatable ball bearing, enabling free rotation of the bottom cap as an extra input port. In this configuration, the upper magnetic cap handles the Set input, while the bottom magnetic cap handles the Reset input, with the output Q represented by the conduction state of the circuit, thereby fulfilling the logical requirements of an SR latch.

Complex logic functions

Building upon the basic logic, we further construct complex computational logic functions. For combinational logic, we propose a logic synthesis algorithm based on the Local Factored Quine-McCluskey (LF-QM) method, aiming to implement customized computational functions using the minimum number of basic units and embedded switches. In principle, any combinational logic function can be realized through a combination of basic units and interconnecting conductive networks. The implementation steps are as follows:

-

1)

Logic Expression Construction: based on the logic diagram, a truth table is drawn, and the QM method is applied to convert the logical expression derived from the truth table into a Sum of Products (SOP) form.

-

2)

Logic Expression Optimization: we apply the distributive law of Boolean algebra to locally factorize the SOP expression, reducing the number of logical operations and literals in the expression. The LF-QM algorithm delineated in the Supplementary Note 4 yields the optimal LF-QM expression, characterized by the minimal count of literals and identical literals.

-

3)

Physical Realization of the Logic Expression: according to Boolean algebra, any Boolean function f(A0,A1,…,An−1) = g(A0,A1,…,An−1, A0’,A1’,…,An−1’) can be constructed using identical literals (Ai or Ai’) and the logical connectives AND (.) and OR (+). The identical literals Ai and Ai’ are implemented using Buffer(Bi) and Not(Ni) units, respectively, where Bi and Ni represent the number of occurrences of Ai and Ai’ in the expression. The interconnecting conductive network is then configured to match the structure of the logic expression, with AND operations implemented via serial connections and OR operations via parallel connections.

We validated the experimental feasibility of this method through the design of a full adder. The full adder has three inputs (A, B, Cin) and two outputs (Cout and S), with the logic diagram and truth table shown in Fig. 3a, b. After extracting common factors and simplifying the QM expressions (Fig. 3c), the LF-QM logic expressions for Cout and S can be written as: Cout = A(B+Cin)+BCin; S = Cin (AB + A’B’) + Cin’(AB’ + A’B). These expressions contain 6 identical literals and a total of 15 literals, requiring 6 basic units and 15 embedded switches for circuit implementation. The basic unit with the most switches is the Buffer(4) for input variable B, which internally integrates four switches. The circuit network is laid out in a combination of series and parallel configurations, with adjacent literals in the expression corresponding to neighboring units, as illustrated in Fig. 3c. The experimental setup and results for the full adder are shown in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. S30 and S31.

Flowchart for constructing a full adder based on the LF-QM method, including a logical schematic, b truth table, c simplified Boolean functions of digital outputs (LF-QM expressions), and circuit network layout, and d experimental Boolean response under four input states. e Comparative analysis of the number of units required for different levels of functional complexity in state-of-the-art mechanical computing technologies3,7,8,9,20,28,50,51. Experimental demonstration of an asynchronous two-bit binary counter, including f logical schematic (Top), a mobile robot with an integrated counter and a seven-segment display for visualization (Bottom), g circuit network layout, with regions enclosed by the same colored block belonging to the same unit, h two-layer experimental platform comprising a lower Magnetic Field Region and an upper Robotic Path, and i real-time digital outputs of A0 and A1 units characterized by voltages collected via a wireless acquisition module. In (h), the orange ellipse represents the magnetic field, while the arrow at its center indicates the direction of the magnetic field.

To further demonstrate its applicability, we used this method to implement more complex combinational logic circuits, including a two-bit adder and a two-bit multiplier (Supplementary Notes 6.2 and 6.3), with integrated circuit diagrams and experimental details provided in Supplementary Figs. 32–35. We conducted a benchmark comparison of recent research in mechanical computing by assessing functional completeness and the number of required units (Fig. 3e) with their primary methods for constructing complex combinational logic summarized in Supplementary Table 4. As combinatorial logic complexity increases, our method’s low-redundancy advantage becomes more pronounced. For a 2-bit adder implementation, our design requires only 8 functional units versus 26 in the prior approach28, achieving a 69% component reduction.

To demonstrate complex sequential logic functionality, we designed an asynchronous binary counter composed of two D-latches (Fig. 3f). The A1 and A0 buffer units of the counter sequentially transition through the states 00 to 01, 01 to 10, and 10 to 11 in response to three successive external magnetic field excitations, which serve as clock signals. For intuitive visualization, we incorporated Not units and circuit layouts to control a seven-segment display, sequentially showing numbers 0, 1, 2, and 3 (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 36 and Video 2). To monitor the output voltage, we devised a switching circuit connected in series with a stable power source and a resistor. Real-time voltage changes across the resistor were collected via a wireless acquisition module, with high and low voltages corresponding to output values of 1 and 0. Snapshots of the experiment and real-time voltage signals are shown in Fig. 3h, i.

Architecture and scalability of MPGA

The MPGA’s programming foundation relies on an origami-controlled addressing robot with input stimulus, which perceives the external magnetic environment and navigates to designated LM locations to activate them. The sensing and control units, composed of Buffer units A0 and A1 (Fig. 4a), demonstrate the addressing functionality. For instance, a robot with A0 and A1 units continuously moves forward; passing position 1 changes the A1A0 state from 11 to 01, and passing position 2 changes it from 01 to 00 (Additional cases in Supplementary Fig. 38). Based on the critical magnetic fields required to trigger transition from states 11 or 01 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 24b), the direction ranges of magnetic field at positions 1 and 2 can be inferred, assuming sufficient magnetic field strength. For instance, at position 1, the initial magnetization directions of A0 and A1 are 240° and 150°, respectively. With the inverted installation of units, the fact that A1 rotates clockwise to state 0 while A0 is in state 1 indicates that the external magnetic field angle lies within the range of [330°, 360°) ∪ [0°, 60°] (Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Video 3).

a Schematic of a mobile robot integrating two sensing units (A0, A1). When the motion of the robot is not controlled by the sensing units, the two units function solely as sensors; when the motion is controlled by the sensing units, they not only sense the external magnetic field but also control the motion of the robot. b Example of magnetic field sensing functionality. As the mobile robot passes through two unknown magnetic fields, the approximate directions of the fields can be inferred from the state transitions of the two units. The green arrow indicates the direction of two magnetic caps when the initial state of A1A0 is 11. The orange arrow indicates the direction of the external magnetic field. The four slices in the pie chart correspond to the angular ranges of the external magnetic field that cause transitions from the initial state 11 to 00, 01, 10, and those that maintain the initial state, respectively. c Addressing robot with reprogrammable trajectories. When the sensing units serve as an automatic control system for addressing, the motion behavior of the robot is governed by the states of the two units. d For a 3 × 3 address array, the relationship between the set of Desired addresses, the corresponding States set, and the magnetic field layout.

Building upon this sensing capability, we constructed an addressing robot capable of autonomous addressing under a predefined external magnetic field layout. The on-robot LMs control its basic motions. Specifically, the outputs of A0 and A1 were used to control the motors of the left and right wheels of a robot, enabling it to achieve forward motion (11), clockwise rotation (10), counterclockwise rotation (01), and stopping (00), enabling it to follow a desired motion trajectory in response to the external magnetic field environment (Fig. 4c). By equipping discretized positions in the operating space with different addresses (ai), a corresponding set of States can be generated based on the Desired addresses set, enabling precise addressing operations. As shown in Fig. 4d, for a 3 × 3 address array, to visit the Desired addresses (1, 4, 5, 8, 9), the external magnetic field stimuli applied at designated positions (magnetic instruction) generate the state sequence States (11, 10, 11, 01, 11, 10, 11), successfully traversing the specified addresses. Similarly, for the Desired addresses (2,3,6,7), the state sequence States (11, 10, 11, 01, 11, 01, 11, 10, 11) can be generated to complete the traversal. Importantly, the addressing robot itself is controlled by the mechanical computing system, preserving the system’s fully mechanical nature. While alternative addressing methods (e.g., manual input, input via movement of loading arms11) are possible, they compromise autonomy or integration and cost. Our robot-based approach enables low-cost, scalable, and automated control without compromising mechanical integrity, making it an appropriate choice for implementing mechanical programmability.

Building upon origami-controlled robotic addressing with embedded conductive network routing for LMs, we established the MPGA. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the MPGA architecture is composed of three functional layers: the bottom layer of magnetic instructions for encoding distinct addressing pathways, the intermediate layer of an addressing robot with magnetic input for passed LMs, and the upper layer of a programmable logic array layer composed of LMs spatially arranged and interconnected via a predefined conductive network to enable routing. Inspired by the LUT concept in FPGA design, LMs located at different spatial positions were configured to represent all possible input combinations(minterms). For instance, a two-input logic function f (X0, X1) has four (22) minterms: \({m}_{0}^{2}\) (X1’X0’), \({m}_{1}^{2}\) (X1’X0), \({m}_{2}^{2}\) (X1X0’), and \({m}_{3}^{2}\) (X1X0), as illustrated in Fig. 5b. Each minterm is assigned a unique address a(i + 1), with the activation indicators of these minterms denoted as ci. The implemented logic function can be expressed using the following logical equation:

Here, \({m}_{i}^{n}\) represents the ith minterm consisting of n input variables; for n = 1, it is simplified to mi. Initially, ci are set to 0. When the addressing robot reaches a specific address, the carried magnetic field acts as both the input signal and the activation trigger for the corresponding minterm. This changes the associated ci value from 0 to 1. The bistable property of the origami structure provides stable memory storage for this activation. Using pre-configured internal parallel routing, arbitrary two-input, one-output logic functions can be programmed. For example, with the magnetic instruction 1, the addressing path sequentially passes through addresses (a1, a2, a4), activating minterms\(\,{m}_{0}^{2}\), \({m}_{1}^{2}\), and \({m}_{3}^{2}\) and setting c0, c1, and c3 to 1. This results in the function \({f}_{1}\left({X}_{1}{,X}_{0}\right)={m}_{0}^{2}{+{m}}_{1}^{2}+{m}_{3}^{2}=\varSigma {m}^{2}({{\mathrm{0,1,3}}})\). Alternatively, with the magnetic instruction 2, the path passes through addresses (a1, a3, a4), activating minterms\(\,{m}_{0}^{2}\), \({m}_{2}^{2}\), and \({m}_{3}^{2}\), yielding \({f}_{2}\left({X}_{1}{,X}_{0}\right)={m}_{0}^{2}{+{m}}_{2}^{2}+{m}_{3}^{2}=\varSigma {m}^{2}({{\mathrm{0,2,3}}})\). This approach allows flexible programming of various logic functions according to different magnetic instructions. Apparently, magnetic instructions corresponding to specific functions can be easily generated through designed software, as detailed in Supplementary Note 8.

a Workflow diagram of the MPGA. b Layout of individual LMs in a 2 × 2 array for general-purpose computation. The LMs at addresses a1–a4 are \({m}_{0}^{2}\)(X1’X0’), \({m}_{1}^{2}\)(X1’X0), \({m}_{2}^{2}\)(X1X0’) and \({m}_{3}^{2}\)(X1X0), respectively. c Layout of individual LMs in a 2 × 2 array for application-specific computation, specifically for half-adder and half-subtractor functions. The LMs at addresses a1–a4 are XOR, Buffer, Not, and Buffer, respectively. d Logical schematics of the half-adder and half-subtractor. The half-adder is implemented by traversing addresses 1, 3, and 4, while the half-subtractor is implemented by traversing addresses 1, 2, and 4. e Experimental images of computations 0−1 = −1 and 0 + 1 = 1. Green and purple trajectory lines with indicator arrows represent the movement paths of the addressing robot for performing the half-adder and half-subtractor computations, respectively. Indicator LEDs for computational outputs and active positions are magnified for clarity.

To validate the MPGA design, we demonstrated the reconfiguration between half-adder and half-subtractor functionalities by arranging appropriate LMs in a 2 × 2 array. Specifically, the LM1 to LM4, corresponding to addresses a1–a4, were configured as XOR, Buffer, Not, and Buffer logic gates, respectively (Fig. 5c). The internal routing paths are shown in Supplementary Fig. 40. Under magnetic instruction 1, LM1, LM2, and LM4 are sequentially activated. In this configuration, the XOR gate in LM1 generates the Sum output S = X⊕Y, while the Buffer gates in LM2 and LM4 form an AND gate to produce the Carry output C = X∧Y, thereby completing the half-adder functionality (Fig. 5d). Similarly, under magnetic instruction 2, LM1, LM3, and LM4 are activated. The XOR gate in LM1 produces the Difference output D = X⊕Y, whereas the Not and Buffer gates in LM3 and LM4 form a Not-AND circuit to compute the Borrow output B = (¬X)∧Y, achieving the half-subtractor functionality.

To facilitate visualization, indicator LEDs were incorporated to represent computational outputs and active positions (Supplementary Fig. 40). The two inputs and four outputs of the circuits were represented by the ON/OFF states of LEDs. Position indicator LEDs monitored the activation status of LMs at each address, controlled by switch units S1 to S4. Additionally, S2 and S4 also controlled the “+” and “=” indicators on the digital display, clearly showcasing the addition or subtraction process. Under input conditions X = 0 and Y = 1, we successfully executed two distinct computation tasks by altering the magnetic instruction: addition (0 + 1 = 1) and subtraction (0−1 = −1) (Fig. 5e). Detailed computational processes and additional cases are provided in Supplementary Fig. 41 and Supplementary Video 4.

To enable flexible execution of large-scale computational tasks, we present the scalable strategy for MPGA consisting of the input and output expansions via serial-parallel arrangements of small-scale MPGAs with parallel computation. For input expansion, we propose a parameter-efficient, minimal-unit architecture with simplified input configuration, termed Input Expansion 1 in Supplementary Fig. 42a. This method uses three basic components: a 1-input MPGA, m0(Not), and m1 (Buffer). An n-input MPGA can be constructed by serially connecting two (n−1)-input MPGAs with m0 and m1, followed by parallel connections. Thus, the function \(f\left({X}_{n-1},\ldots,{X}_{1}{,X}_{0}\right)\) can be expressed as:

where \({f}_{1}\) and \({f}_{2}\) are (n−1)-input functions. Through recursive derivation, an n-input MPGA can ultimately be constructed using three basic components. This approach requires 2n+1-2 basic units, provides 2n programmable parameters, and introduces no redundancy, ensuring high integration density. Furthermore, as all basic components are single-input, the operation remains straightforward. Alternative input expansion techniques, involving Input Expansion 2 with a single component but lower integration and Input Expansion 3 with simpler interconnections but complex input operations, are discussed within the Methods and Supplementary Note 9.1. In addition to 1-input MPGAs, multi-input MPGAs (e.g., 2-input MPGAs) can also serve as basic components for similar input expansion, albeit requiring more units, with details provided in Supplementary Note 9.2 and Supplementary Fig. 43. In practical applications, the optimal input expansion approach can be selected based on prioritized factors and operational constraints. For example, when minimizing the number of units is the primary objective, expansion based on 1-input MPGAs via Input Expansion 1 is recommended.

Output expansion can be achieved through parallel operation of m n-input, 1-output MPGAs to form an n-input, m-output MPGA system (Supplementary Fig. 42b). As an example, we demonstrated the reprogrammable functionalities of a full adder and a full subtractor using a 3-input, 2-output MPGA, comprising two parallel 3-input, 1-output MPGAs (MPGA1 and MPGA2), implemented via Input Expansion 1(Supplementary Fig. 42c). MPGA1 was programmed to generate the carry-out (Cout) of the full adder, while MPGA2 produced the sum (S). The MPGAs operated in parallel to realize full adder functionality. Since the difference (D) output of the full subtractor shares the same logic expression as the sum (S), reconfiguring MPGA1 to generate the borrow (B) output enabled full subtractor functionality. To further illustrate the programmability and scalability of the MPGA, a 4-input, 4-output MPGA was designed and demonstrated for programming the logic functions of a 2-bit adder and a 2-bit multiplier. This MPGA comprises four parallel 4-input, 1-output MPGAs (designated MPGA1–MPGA4), which were programmed to generate the output sets (P0, S0), (P1, S1), (P2, C), and P3, respectively (Fig. 6a). Each 4-input, 1-output MPGA was realized through the Input Expansion 1 methodology, yielding a structure with 16 addressable positions and 30 LMs (Fig. 6b). To ensure a deterministic zero-output state in the unprogrammed configuration, the minterms associated with the input variable B0 were configured to output 0. Thus, only input variable B0 was left in an undefined state, whereas the remaining inputs (B1, A0, and A1) were fixed to logic 0 (Fig. 6c). Under the specific input condition A1A0B1B0 = 1111, the system successfully executed two distinct computational tasks, addition (3 + 3 = 6) and multiplication (3 × 3 = 9), with MPGA2 generating P1 = 0 and S1 = 1 via distinct address activation sequences (Fig. 6d). Detailed programming sequences, calculation procedures, and additional computational cases are provided in Supplementary Note 10.1 and Supplementary Video 6. Owing to its reconfigurable architecture, this 4-input, 4-output MPGA is generalizable to arbitrary combinational logic functions with up to four inputs and four outputs, as exemplified by its applicability to a 2-bit subtractor.

a Schematic illustration of the programmable functionality of a 2-bit adder and a 2-bit multiplier based on a 4-input, 4-output MPGA. b Top view and circuit layout details of a 4-input, 1-output MPGA, with the four rows of modules (from top to bottom) corresponding to inputs A1, A0, B1, and B0. c Structural details of a 4-input, 1-output MPGA, comprising 15 m0 modules and 15 m1 modules, corresponding to Not(1) and Buffer(1) units, respectively. The inputs for the first three rows (A1, A0, B1) are fixed at logic 0, while the bottom row (B0) is maintained in an undefined state, with all outputs fixed at logic 0. d Experimental demonstration of the programmed address paths in MPGA2 for generating P1(2-bit multiplier) and S1(2-bit adder) outputs. Purple and green trajectory lines with indicator arrow represent the movement paths of the addressing robot for performing the P1 and S1 computations, respectively.

Previous research has demonstrated that the computational capabilities of mechanical computing systems based on switching circuit theory can be expanded through serial-parallel arrangements of switches8. Conversely, systems built upon cascaded logic gates can have their computational power extended via logic gate cascading or registers7,20,25. As our MPGA framework is also constructed upon switching circuits, the input and output expansions we propose for the MPGA are similarly realized through serial-parallel circuit arrangements. Furthermore, specifically for our MPGA framework, we analyze the impact of different input expansion schemes on integration density, input complexity, the number of components, and interconnection complexity. This analysis offers valuable references for expanding computational functionality under resource or technology-constrained conditions.

Computation functional reuse

For facilitating iterative algorithms, we leverage the interactions between the MPGA and the memory unit to enable computation functional reuse. For mechanical computing systems with heterogeneous input-output physical quantities, reusing computational functions typically requires additional mechano-electro-mechanical conversion devices, such as electroactive liquid crystal elastomer actuators19, voice coil motor actuators40, and conductive super-coiled polymer actuators9. These devices typically generate unidirectional force and necessitate extra mechanical components to convert this force into the input torque required by our computational units. To address this, we propose a method that leverages the motion path of the computational function to convert its output voltage into input stimulus for memory units, enabling interaction between the output electrical signal and input magnetic excitation and serving as a low-cost, and autonomously reusable approach for computation–memory interaction.

Implementation of high-bit adders by reusing full adders was demonstrated to illustrate the path-stored computation reuse methodology (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 61). An m-bit ripple carry adder is typically composed of m full adders connected in series, where the carry-out of the (k-1)th full adder (Cout, k−1) is connected to the carry-in of the kth full adder (Cin, k), and the carry-in of the first full adder (Cin, 0) is grounded (logic 0). In cases where a single full adder is used, memory units are employed to store intermediate outputs and feed them back as input for the next operation. Based on this principle, when a 3-input, 2-output MPGA is configured as an adder or subtractor and reused m times, it can function as a reconfigurable m-bit adder/subtractor. Specifically, this functionality is realized through a four-layer experimental platform (Fig. 7b) comprising a memory stimulus layer (Layer 1), a mobile MPGA layer (Layer 2), an addressing robot layer (Layer 3), and a magnetic instruction layer (Layer 4). The mobile MPGA layer is a mobile device equipped with a 3-input, 2-output MPGA depicted in Supplementary Fig. 42c, indicating that the MPGA is not static but possesses the capability for dynamic movement directed by the output of its computations. The logic units within the mobile MPGA layer are discretely arranged, with those controlled by the input variables X0 and X1 (including the corresponding Buffer and Not units) positioned at the bottom to sense activation and program the adder or subtractor. Meanwhile, units responsible for controlling the storage of carry or borrow (input variable X2), as well as those for storing output results (S1 and S0), are located at the top to sense storage excitation, enabling the retention of intermediate and final results. Detailed experimental procedures are provided in Supplementary Note 10.2 and Supplementary Fig. 55.

a Reprogrammable schematic of an m-bit adder and m-bit subtractor based on a 3-input 2-output MPGA. b Schematic of the experimental platform for a two-bit adder implemented using the MPGA. c Schematic of the experimental platform for a two-bit adder constructed with predefined full adder functionality. d Schematic of the mobile full adder in Layer 2, and e the truth table for the motion control of the mobile robot. f Computational workflow of the two-bit adder, showing the magnetic field layouts of Layer 1 and Layer 3, and the trajectory map of Layer 2. Light green, green, and dark green indicate the trajectories for computational tasks 0 + 3 = 3, 2 + 0 = 2, and 3 + 3 = 6, respectively. g Experimental images corresponding to the three computational tasks above. Blue and orange circles represent the magnetic fields serving as memory stimulus and input stimulus, respectively, with the arrows at their centers indicating the direction of the magnetic fields.

Since the reconfiguration of the MPGA has been experimentally verified, we focus here on demonstrating computation reuse. We present a 2-bit adder implementation by using the full adder twice. According, the MPGA is customized directly to the full adder. Then the magnetic instruction layer (Layer 4) and the addressing robot layer (Layer 3) are simplified to an input stimulus layer, and the mobile MPGA layer is replaced with a mobile full adder circuit layer. The input variables X0, X1, and X2 correspond to A, B, and C, respectively (Fig. 7c). The mobile full adder is depicted in Fig. 7d, with its motion controlled by its outputs S and Cout (Fig. 7e). The internal routing paths of the units on the mobile robot are in Supplementary Fig. 56. The computational process is outlined in Fig. 7f.

Step 1: The mobile fuller adder begins in the forward state. Along the forward path, the adder, under the influence of the lower-layer input stimulus, inputs the least significant bits of the two addends, A0 and B0, into the A and B units. Then, it computes their sum, S, and carry, Cout. The resulting output voltages move the mobile adder to the designated position where the input stimulus (storage stimulus) for C and S0 units is placed.

Step 2: The mobile fuller adder is then activated by the upper-layer storage stimulus, storing the computed results Cout and S into the C and S0 units. At this stage, the C unit holds the carry, Cin.

Step 3: The adder is reactivated again by the lower-layer input stimulus to input the next pair of addends, A1 and B1, into the A and B units. It computes their sum, S, and the new carry, Cout. The resulting output voltages move the mobile adder to the designated position where the input stimulus (storage stimulus) for C and S1 units is placed.

Step 4: The adder receives storage stimulus from the upper layer, storing the computed results Cout and S into the C and S1 units. At this point, the C, S1, and S0 units store the final results for the two addends A1A0 and B1B0. By reusing the adder twice, we achieve the functionality of a 2-bit adder, completing the calculation A1A0 + B1B0 = CS1S0.

Under varying input stimulus, the path of the mobile full adder and the corresponding computation functions are shown in Fig. 7f. Experimental snapshots of the 2-bit addition computations 0 + 3 = 3, 3 + 3 = 6, and 2 + 0 = 2, are shown in Fig. 7g (Supplementary Video 5), with real-time voltage results provided in Supplementary Fig. 57. More generally, by incorporating a fractal design based on a ternary junction structure at the input positions and applying self-similar extensions of input and memory excitations, the adder can be reused multiple times to form multi-bit adders (Supplementary Note 10.3 and Fig. 58).

Through interaction with memory units, computational functions can be repeatedly executed. This also provides the foundational design for weight updates in neural networks. For example, in a simplified binary neural network model, the goal is to predict the output by fitting the linear expression Yt = wX + b, where X is the input and w and b are the weight parameters to be optimized. The training process is guided by analyzing the error E, defined as the difference between the predicted output Yp and the actual output Yt. Parameters w and b are updated through a conditional exhaustive search algorithm to minimize this error, allowing the network output to converge toward the target value and thus facilitating network learning and model optimization. The process starts with predicting the output using a 1-bit multiplier (equivalent to an AND gate) and a 1-bit adder to calculate Yt based on the current values of w and b. A 2-bit comparator then compares Yp with Yt to determine the error. Based on this error, the parameters are adjusted: if the error is greater than 0, the counter’s current count value is decreased, reducing w and b; otherwise, w and b are increased. This process is repeated iteratively until the error approaches zero, completing the training for the current parameters. Detailed implementation plans can be found in Supplementary Note 10.4 and Supplementary Fig. 59. Notably, if the weight update algorithm is constructed using MPGA, the input-output relationships can be flexibly reprogrammed. For example, through reprogramming, the fitting function can be changed from Yt = wX + b to Yt = wX−b. This flexibility is crucial for developing self-learning and adaptive capabilities in bio-inspired intelligent systems, as it enables the system to adjust its learning strategies based on changes in the physical environment and evolving task demands. This adaptability fosters more effective interaction with the environment and enhances the system’s overall performance.

Discussion

Our MPGA computational architecture achieves programmability by routing capabilities provided by embedded conductive network pathways and the addressing functionality of origami-controlled robots. The low-redundancy nature of the functional modules is primarily realized through basic units containing multiple switch circuits and the LF-QM logic optimization algorithm mapped onto improved units. The MPGA architecture is akin to the configurable LUTs in FPGAs, providing flexibility for computational functions. The resulting programmable computational system retains the scalability of embedded integrated circuits, allowing large-scale MPGA construction by extending small MPGA modules. Furthermore, when combined with the memory capabilities, MPGA can repeatedly perform identical computational tasks, supporting iterative algorithms such as bitwise scalable arithmetic operations and neural network weight updates, and facilitating the development of bio-inspired self-learning mechanical systems. The proposed MPGA system offers a general-purpose mechanical computing architecture that synergizes programmability, scalability, and reusability to enhance the computational capabilities of mechanical systems.

The current architecture is built upon the bistable properties of the Kresling structure to realize binary computation. In recent years, researchers have developed stable mechanical memory in multistable systems through mechanisms such as gradient structural parameters14, geometric frustration16, and coupling kinematic bifurcation13. These strategies offer a promising foundation for designing Kresling-based structures with multistable characteristics, enabling the exploration of mechanical computing architectures beyond binary logic. The automation of magnetic instruction layout in MPGA systems can further enhance system flexibility and efficiency41. Furthermore, the scale-independent physical mechanisms inherent in our architecture, coupled with advancements in additive manufacturing technology1, allow for further miniaturization and mass fabrication42,43.

The integration of computational and memory modules in the MPGA architecture establishes a unified sense-compute-store framework. This enables intelligent systems to execute elementary decision-making functions in response to external environments through embodied logic5,44 and effectively reduces data transmission burdens in localized edge computing45,46,47,48. Besides, MPGA’s programmability significantly enhances functional versatility when robots encounter diverse task scenarios. Consequently, MPGA is well-suited for embodied intelligent robotics and distributed edge computing applications49, thereby laying the foundation for autonomous decision-making and self-learning intelligent matter with robust environmental adaptability and offering a promising pathway for compact, efficient, and decentralized computation in future intelligent systems. While current mechanical computing systems exhibit limitations in handling complex deep learning tasks compared to mature electronic systems, their unique advantages in environmental adaptability and integrated sensing-computing capability make them particularly suitable for replacing conventional electronics in extreme operating conditions.

Methods

Origami unit and magnetic cap fabrication

The preparation of the origami structure is achieved by cutting and folding PET sheets. We used a digital cutting machine to precisely cut the modified Kresling crease pattern on a 0.075-mm-thick PET sheet. These patterns were then folded into shape, and hexagons were attached to the bottom and top sides of the origami structure using quick-drying adhesive. The hexagons, made of 0.015-mm-thick PET sheets, were designed with a circular hole in the center for the wiring network. The use of thicker material for the hexagons ensures sufficient stiffness and prevents them from bending. We also studied the mechanical performance changes of the origami structure after multiple compression cycles. As shown in the Supplementary Fig. 3, we present the force-displacement response of the designed origami structure after 100 folding cycles. We observed that the mechanical response stabilized after approximately 90 cycles. Therefore, to ensure consistency, all samples underwent up to 100 folding cycles prior to the magnetic actuation and mechanical tests reported in this study.

On top of the origami unit, we fixed the magnetic cap using double-sided adhesive. The magnetic cap was made by mixing PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning Co., Ltd) with neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) particles, creating a homogeneous mixture containing 70% by mass of NdFeB. The mixture was poured into a laser-cut aluminum alloy mold, which consists of two stacked aluminum plates. The upper plate was cut into a periodic hexagonal pattern. After pouring the mixture, an additional layer of aluminum alloy was added to ensure the flatness of the top and bottom surfaces of the magnetic cap. The whole assembly was then placed in an oven and cured at 100 °C for 1 h. After curing, the magnetic cap was magnetized to saturation using a 2 T pulse magnetic field magnetizer (DPM1, Beijing Eusci Earth Technologies Ltd.). The magnetization strength of the magnetic cap was measured to be M = 173 kA/m using a Superconducting Quantum Interference Device magnetometer (MPMS3, Quantum Design).

Magnetic actuation method

A custom-built three-dimensional Helmholtz coil system (PS-3HM368, Hunan Paisen Technology Co., Ltd.) is used to generate a uniform three-dimensional magnetic field. Three sets of standard Helmholtz coils are arranged perpendicular to each other on the x-y, y-z, and x-z planes, forming an operable magnetic space with dimensions of x × y × z = 120 × 80 × 40 mm. The uniformity of this magnetic space is 99%. The input current precisely controls the strength and direction of the in-plane magnetic field. The coil can generate a uniform magnetic field of ±15 mT along the z-axis, ±25 mT along the y-axis, and ±30 mT along the x-axis. Magnetic Control Input Method for a multi-unit system can be seen in Supplementary Note 3.

Circuit network layout and unit assembly

The embedded wire paths in the unit primarily consist of copper tape, copper enameled wire, and spring contacts. Circular holes are pre-cut at the centers of the top and bottom faces of the Kresling origami, the center of the magnetic cap, and the bottom of the external frame. A copper wire passes sequentially through the bottom frame, the origami, and the magnetic cap. One end of the wire extends from the bottom of the frame and serves as one terminal of the electrical output, while the other end is connected to a copper foil adhered to the top surface of the magnetic cap. Five recessed slots are pre-fabricated on the top of the outer frame to accommodate spring contacts. These contacts are conductive and have a retractable end designed to make contact with the copper foil once the origami deploys. The opposite end is exposed on the top surface of the outer frame, serving as the other terminal of the output. The origami is affixed to the inner wall of the frame, the magnetic cap is attached to the origami, and the copper foil is attached to the magnetic cap—all using double-sided adhesive tape. The Buffer (1) gate requires only one switch, so a single spring-loaded contact is embedded at the center of the top frame, and the copper foil on the magnetic cap covers the entire surface. The Not (4) gate, in contrast, requires four switches; therefore, four symmetrically arranged spring contacts are embedded on the top surface, and the copper foil on the magnetic cap is divided into four electrically isolated segments.

Two-input single-output logic gates, such as AND and OR, are implemented by connecting two Buffer (1) units in series and parallel, respectively. To reduce magnetic interference between adjacent caps, a spacer plate is inserted between them. Electrical connections in series and parallel configurations are established using conductive copper tape. The unit frames are equipped with corresponding mortise-and-tenon structures, allowing the units to be connected in the horizontal and vertical directions on the plane, thereby constructing larger-scale computational systems. The connections between the wire paths of the units are made through the copper tape layout on the upper and lower surfaces of the computational system. To connect corresponding switches of two units in series, the copper tapes at the bottom or top of the two-unit frames can be connected. To connect them in parallel, the copper tapes at the top and bottom of both unit frames need to be connected.

Experimental digital state characterization

The input and output of various computational functions (such as counters, half adders, half subtractors, and two-bit adders) built within the computational framework were experimentally tested and verified against the corresponding truth tables for digital inputs and outputs. Specifically, the digital state of input variables is characterized by the output state of the corresponding Buffer units for those input variables. Depending on the actuator (such as LED lights, motors, or resistors), a corresponding stabilized power supply is provided to the switch conductive network. The input and output states are characterized by voltage levels. A voltage reading close to the corresponding divided voltage of the actuator is considered a digital output of 1, while a voltage reading of 0 V is considered a digital output of 0.

Voltage data acquisition method

The voltage of the units located on the mobile robot is real-time collected by a wireless acquisition module on the robot. The wireless acquisition module used is the OpenBCI Cyton eight-channel Biosensing Boards, which features a PIC32MX250F128B microcontroller providing ample local memory and fast processing speed. The Analog Front-End chip is an ADS1299, offering high-gain, low-noise analog-to-digital conversion (ADC) with a 24-bit channel resolution. The RFduino radio module enables wireless communication with a computer through the OpenBCI USB Bluetooth communication module. During the experiment, data is sampled at a frequency of 250 Hz on each channel. The voltage of the stationary units is collected using a wired data acquisition board. The acquisition borad is the eight-channel USB2AD7606, with the AD706 as the main control chip. It uses USB 2.0 high-speed communication with a 16-bit channel resolution. In the experiment, data is also sampled at a frequency of 250 Hz on each channel.

LF-QM expression

The logic expressions for the outputs S (Sum) and C (Carry) of the full adder can be written in the following form based on the truth table:

S = A’B’Cin + A’BCin’ + AB’Cin’ + ABCin

C = ABCin + ABCin’ + AB’Cin + A’BCin

After simplifying using the QM method, the SOP expressions are as follows:

S = A’B’Cin + A’BCin’ + AB’Cin’ + ABCin

C = AB + ACin + BCin

The expression further simplified using the LF-QM method is as follows:

The logic expressions for the outputs S1, S0, and C of the two-bit adder can be written in the following form based on the truth table:

C = A0’B0’A1B1 + A0’B0A1B1 + A0B0’A1B1 + A0B0A1B1 + A0B0A1B1 ’ + A0B0 A1’B1

S1 = A0B0A1B1 + A0B0A1’B1’ + A0’B0A1B1’ + A0’B0’A1B1’ + A0’B0’A1’B1 + A0’B0A1’B1 + A0B0’ A1B1’ + A0B0’A1’B1

S0 = A0B0’ + A0’B0

After simplifying using the QM method, the SOP expressions are as follows:

C = A1B1 + A0B0A1 + A0B0B1

S1 = A0B0A1B1 + A0B0A1’B1’ + A0’A1B1’ + A0’A1’B1 + B0’A1B1’ + B0’A1’B1

S0 = A0B0’ + A0’B0

The expression, further simplified using the LF-QM method, is as follows, the algorithm output interface is shown in the Supplementary Fig. 26a:

C = A1B1 + A0B0(A1 + B1)

S1 = A0B0(A1B1 + A1’B1’) + (A0’ + B0’)(A1B1’ + A1’B1)

S0 = A0B0’ + A0’B0

Alternative input expansion techniques

For Input Expansion 2, it consists of only one type of component, namely the 1-input 1-output MPGA. By serially chaining 2n−1 rows of n 1-input 1-output MPGAs, followed by parallel connections, an n-input MPGA can be realized. Its logic expression is:

This approach also requires n.2n basic units, but n.2n−1 1-input MPGAs, each with two programmable parameters, leading to n.2n programmable parameters overall. However, it introduces (n−1).2n redundant parameters, lowering integration density despite simplifying input operations.

For Input Expansion 3, the MPGA can be scaled directly using the LUT concept via constructing all input combinations (\({m}_{i}^{n}\)) corresponding to n-input variables (X0 to Xn−1), as defined by the following logic function of n-input MPGA:

This method requires n.2n basic units, with 2n programmable parameters, matching the number of minterms without redundancy. However, as n increases, each minterm involves n inputs, raising the complexity of magnetic field input stimuli and operations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the manuscript or the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Song, Y. et al. Additively manufacturable micro-mechanical logic gates. Nat. Commun. 10, 882 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Structural multi-colour invisible inks with submicron 4D printing of shape memory polymers. Nat. Commun. 12, 112 (2021).

Conrad, S. et al. 3D-printed digital pneumatic logic for the control of soft robotic actuators. Sci. Robot. 9, eadh4060 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Small-scale soft grippers with environmentally responsive logic gates. Mater. Horiz. 9, 1431–1439 (2022).

Kaspar, C., Ravoo, B. J., van der Wiel, W. G., Wegner, S. V. & Pernice, W. H. P. The rise of intelligent matter. Nature 594, 345–355 (2021).

Yasuda, H. et al. Mechanical computing. Nature 598, 39–48 (2021).

Mei, T., Meng, Z., Zhao, K. & Chen, C. Q. A mechanical metamaterial with reprogrammable logical functions. Nat. Commun. 12, 7234 (2021).

El Helou, C., Grossmann, B., Tabor, C. E., Buskohl, P. R. & Harne, R. L. Mechanical integrated circuit materials. Nature 608, 699–703 (2022).

Yan, W. et al. Origami-based integration of robots that sense, decide, and respond. Nat. Commun. 14, 1553 (2023).

Yasuda, H., Tachi, T., Lee, M. & Yang, J. Origami-based tunable truss structures for non-volatile mechanical memory operation. Nat. Commun. 8, 962 (2017).

Chen, T., Pauly, M. & Reis, P. M. A reprogrammable mechanical metamaterial with stable memory. Nature 589, 386–390 (2021).

Guo, X., Guzmán, M., Carpentier, D., Bartolo, D. & Coulais, C. Non-orientable order and non-commutative response in frustrated metamaterials. Nature 618, 506–512 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Reprogrammable and reconfigurable mechanical computing metastructures with stable and high-density memory. Sci. Adv. 10, eado6476 (2024).

Xin, L., Li, Y., Wang, B. & Li, Z. Magnetic poles enabled kirigami meta-structure for high-efficiency mechanical memory storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310969 (2024).

Novelino, L. S., Ze, Q., Wu, S., Paulino, G. H. & Zhao, R. Untethered control of functional origami microrobots with distributed actuation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24096–24101 (2020).

Sirote-Katz, C. et al. Emergent disorder and mechanical memory in periodic metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 15, 4008 (2024).

Pal, A. & Sitti, M. Programmable mechanical devices through magnetically tunable bistable elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2212489120 (2023).

El Helou, C., Buskohl, P. R., Tabor, C. E. & Harne, R. L. Digital logic gates in soft, conductive mechanical metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 12, 1633 (2021).

El Helou, C., Hyatt, L. P., Buskohl, P. R. & Harne, R. L. Intelligent electroactive material systems with self-adaptive mechanical memory and sequential logic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2317340121 (2024).

Mei, T. & Chen, C. Q. In-memory mechanical computing. Nat. Commun. 14, 5204 (2023).

He, Q., Ferracin, S. & Raney, J. R. Programmable responsive metamaterials for mechanical computing and robotics. Nat. Comput. Sci. 4, 567–573 (2024).

Ruiz-Rosero, J., Ramirez-Gonzalez, G. & Khanna, R. Field programmable gate array applications—a scientometric review. Computation 7, 63 (2019).

Bogaerts, W. et al. Programmable photonic circuits. Nature 586, 207–216 (2020).

Debnath, S. et al. Demonstration of a small programmable quantum computer with atomic qubits. Nature 536, 63–66 (2016).

Lv, H. et al. DNA-based programmable gate arrays for general-purpose DNA computing. Nature 622, 292–300 (2023).

Hack, J. J. On the promise of general-purpose parallel computing. Parallel Comput. 10, 261–275 (1989).

Byun, J., Pal, A., Ko, J. & Sitti, M. Integrated mechanical computing for autonomous soft machines. Nat. Commun. 15, 2933 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Mechanical system with soft modules and rigid frames realizing logic gates and computation. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2200374 (2023).

Cai, J., Deng, X., Zhou, Y., Feng, J. & Tu, Y. Bistable behavior of the cylindrical origami structure with Kresling pattern. J. Mech. Des. 137, 061406 (2015).

Masana, R., Dalaq, A. S., Khazaaleh, S. & Daqaq, M. F. The Kresling origami spring: a review and assessment. Smart Mater. Struct. 33, 043002 (2024).

Berre, J., Geiskopf, F., Rubbert, L. & Renaud, P. Toward the design of Kresling tower origami as a compliant building block. J. Mech. Robot. 14, 045002 (2022).

Misseroni, D. et al. Origami engineering. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 4, 40 (2024).

Huang, C., Tan, T., Hu, X., Yang, F. & Yan, Z. Bio-inspired programmable multi-stable origami. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 051902 (2022).

Cao, M. et al. Multistable bi-modulus Kresling origami with superior foldability and stiffness: An analytical design model. Eng. Struct. 330, 119955 (2025).

Rodriguez-Feliciano, R. & Wang, K. W. Synthesis of a highly programmable multistable Kresling origami-inspired unit cell. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 284, 109768 (2024).

Fang, X. et al. Large recoverable elastic energy in chiral metamaterials via twist buckling. Nature 639, 639–645 (2025).

Wang, J. X., Yang, Q. S., Wei, Y. L. & Tao, R. A novel chiral metamaterial with multistability and programmable stiffness. Smart Mater. Struct. 30, 065006 (2021).

Fu, M., Liu, F. & Hu, L. A novel category of 3D chiral material with negative Poisson’s ratio. Compos. Sci. Technol. 160, 111–118 (2018).

Bolopion, A., Bouchebout, S. & Régnier, S. Fast, repeatable and precise magnetic actuation in ambient environments at the micrometer scale. J. Micro Bio Robot. 13, 55–66 (2017).

Jiang, R. et al. Modular bistable mechanical metamaterials: a versatile platform for piezoelectric self-charging, sensing, and logic operations. Mater. Today 83, 96–112 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Active mechanical haptics with high-fidelity perceptions for immersive virtual reality. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 643–655 (2023).

Zhao, T. et al. Modular chiral origami metamaterials. Nature 640, 931–940 (2025).

Miskin, M. Z. et al. Electronically integrated, mass-manufactured, microscopic robots. Nature 584, 557–561 (2020).

Jiang, Y., Korpas, L. M. & Raney, J. R. Bifurcation-based embodied logic and autonomous actuation. Nat. Commun. 10, 128 (2019).

Khan, W. Z., Ahmed, E., Hakak, S., Yaqoob, I. & Ahmed, A. Edge computing: a survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 97, 219–235 (2019).

Zhang, L., Tan, T., Chen, Y. & Yan, Z. Programmable logic functions-integrated acoustic in-sensor computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2423314 (2025).

Zhou, F. & Chai, Y. Near-sensor and in-sensor computing. Nat. Electron. 3, 664–671 (2020).

Huang, H. et al. Fully integrated multi-mode optoelectronic memristor array for diversified in-sensor computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 93–103 (2025).

Cao, K., Liu, Y., Meng, G. & Sun, Q. An overview on edge computing research. IEEE Access 8, 85714–85728 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Thermal computing with mechanical transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401244 (2024).

Jiao, Z. et al. Reprogrammable, intelligent soft origami LEGO coupling actuation, computation, and sensing. Innovation 5, 100549 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shanghai Key Technology Research and Development Program “Pioneer Program” (Grant No. 25XF3200300, Z.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.12572395, T.T.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.12572176, Z.Y.). The authors thank Prof. Wang Dong for providing the three-dimensional Helmholtz coil system, and Dr. Wang Jinqiang for his technical assistance with the equipment operation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., T.T., and Z.Y. conceived the ideas and designed the research. Y.C. and Z.Y. established the theoretical model. Y.C. performed the experiments. Y.C., T.T., and Z.Y. analyzed the data. Y.C., T.T., and Z.Y. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. Z.Y. supervised the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yanbin Li, Jared Butler, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Tan, T. & Yan, Z. General-purpose mechanical computing enabled by origami circuit reconfiguration with robotic addressing and activation. Nat Commun 16, 10483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65464-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65464-x