Abstract

Cellular systems governing protein folding depend on functional redundancy and diversification to maintain proteostasis. Here, using Caenorhabditis elegans, we show two homologous ER-resident HSP70 chaperones, HSP-3 and HSP-4, have overlapping and distinct roles in ER proteostasis and organismal physiology. Their expression and function vary by tissue, age, and stress, impacting ER stress resistance, reproduction, body size, and lifespan. We also find HSP-3 and HSP-4 uniquely regulate dietary restriction and reduced insulin signaling-mediated longevity in C. elegans. Notably, knockdown of hsp-4, but not hsp-3, induces autophagy and enhances tolerance to protein aggregation stress; this process requires the ortholog of ER-Phagy receptor Sec-62 (C18E9.2) and IRE-1. Finally, human cell data suggests that the dissociation of chaperone Binding Immunoglobulin Protein (BiP) from IRE-1 during times of ER stress promotes autophagy by enhancing the interaction of IRE-1 and Sec-62. These findings reveal how ER chaperone diversification maximizes stress resilience and suggest a BiP-dependent regulation of autophagy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gene duplications generate paralogs that encode distinct proteins. This process drives genetic evolution and ensures organismal survival1,2. Although structurally similar, evolutionary pressure pushes the development of distinct functions of these seemingly redundant proteins3. Current literature suggests only ~25% of duplicated genes can compensate for loss of function of their respective counterpart—however, almost always in a severely reduced capacity4,5.

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are highly conserved molecular chaperones which maintain protein homeostasis (proteostasis) under physiological and stress-induced conditions6. These proteins are categorized based on their molecular size and distinguished by subcellar compartmentalization and function. Chaperones of the 70 kilodalton heat shock protein (HSP70) family have been implicated in cardiovascular disease7, various cancers8,9,10, and numerous neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease11 and Parkinson’s disease12.

As eukaryotes evolved, the proteome diversified and became more complex, accumulating proteins rich in beta folds or amino acid expansion sequences. To support proper folding of these often misfolding-prone proteins, protein quality control systems expanded and differentiated. One key adaptation included the expression of a functionally expanded panel of HSP70 family chaperones13,14. For example, the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, expresses at least seven, and humans at least thirteen, HSP70 family chaperones15, with many sharing overlapping subcellular localization16. Homology-based functional predictions and shared expression patterns suggest at least partial functional overlap between these distinct chaperones. However, reliance on such predictions without experimental validation may lead to incomplete or inaccurate conclusions of paralogous protein function(s), while prohibiting the identification of newly acquired protein activities.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is required across taxa to properly fold nascent proteins and regulate interorganellar signaling to maintain cellular proteostasis—processes essential to sustain life17. Misfolded proteins within the ER are detected and refolded by HSPs or cleared through evolutionarily conserved mechanisms which navigate crosstalk between the ER and other organelles, such as the unfolded protein response of the ER (UPRER)18 and ER-selective autophagy (ER-Phagy)19.

The UPRER is mediated by three canonical ER transmembrane proteins: Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 (IRE-1), Protein Kinase R-like ER Kinase (PERK), and Activating Transcription Factor 6 (ATF-6). ER stress triggers specific transcriptional responses unique to each UPRER mediator to mitigate protein misfolding burden20. ER-phagy is the degradation of ER-specific cargo through canonical autophagy mechanisms19. ER-phagy requires transmembrane receptors to recruit cytosolic autophagy-related proteins to the ER membrane. These proteins assist in engulfing the ER-membrane (and luminal components) into autophagosomes for subsequent degradation and recycling. This process rids the ER of misfolded proteins and reduces the size of the ER to its homeostatic size following the resolution of ER stress19. ER-Phagy and the UPRER are co-regulated; however, the mechanistic details of this relationship remain elusive21.

In human cells, the essential ER-resident HSP70 family chaperone, Binding-Immunoglobulin Protein (BiP), contributes to protein (re)folding while regulating UPRER activation and select forms of ER-Phagy. In unstressed cells, binding of BiP to IRE-1, PERK, or ATF-6 prevents the activation of each of the three arms of the UPRER. Upon increased protein misfolding, BiP dissociates from the UPRER mediators, thus derepressing the UPRER and activating transcriptional programs aimed at restoring proteostasis22,23,24. BiP also activates FAM134B-mediated ER-Phagy to help efficiently restore ER proteostasis25,26. Still, how a single HSP70 family chaperone fulfills this multitude of critical activities, as well as the extent of BiP’s regulation of ER-mediated signaling mechanisms, remains incompletely understood.

Of the seven canonical HSP70 family chaperones found in C. elegans, four are cytosolic (HSP-1, C12C8.1, F44E5.4, F44E5.5) and a single HSP70 chaperone is found in the mitochondria (HSP-6); but, unlike humans, two distinct BiP-like proteins are found exclusively in the ER (HSP-3, HSP-4)15. Although hsp-3 is transcribed at higher levels than hsp-4, previous work showed hsp-3 and hsp-4 transcripts are both stress responsive and partially regulated by the UPRER27,28. However, despite a well-described transcriptional relationship between these two chaperones suggesting potential functional compensation28, evidence showing hsp-4, but not hsp-3, is required for proper cuticle formation during worm development indicates currently unknown independent functions of these paralogs29.

Here, we describe the overlapping and distinct functions of C. elegans BiP orthologs, HSP-3 and HSP-4, in stress resilience, body growth, reproduction, lifespan, and autophagy. Our data further suggest a conserved link between HSP-4/BiP’s regulation of autophagy through IRE-1 and the putative ER-phagy receptor C18E9.2/Sec-62. Overall, our findings highlight how diversified HSP70 chaperones cooperate to optimize stress resilience and maintain proteostasis in metazoans.

Results

HSP-3 and HSP-4 proteins have distinct expression profiles

C. elegans express two ER-resident HSP70 family chaperones (HSP-3 and HSP-4), while human cells express a single ER-resident HSP70 family chaperone (BiP) to maintain ER proteostasis. To better understand the roles of HSP-3 and HSP-4, we generated HSP-3::wrmScarlet (PHX4377) and HSP-4::wrmScarlet (PHX4415) fusion protein reporters using CRISPR/Cas9. RT-qPCR confirmed HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet were expressed at similar levels to hsp-3 and hsp-4 in wild type (WT) animals (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). To confirm HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet are functional, we assessed the development of these reporter strains when grown on E. coli expressing siRNA against the reciprocal chaperone, knowing that at least one functional BiP ortholog is required for proper development30,31,32. Both transgenic strains developed similar to controls (pos-1 siRNA) even in the absence of the respective paralog, suggesting HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet are functional proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1c). POS-1 is a zinc-finger transcription factor that is only expressed during early embryonic development; pos-1 siRNA was used as a control, as pos-1 knockdown results in embryonic lethality but does not affect the physiology of late larval and adult animals nor the expression of hsp-3 or hsp-4 (Supplementary Fig. 2)30,33.

We next determined the temporal expression of both HSP-3 and HSP-4 via immunoblotting. HSP-3::wrmScarlet levels were greater than HSP-4::wrmScarlet throughout development and in day 1 adult worms. Relative HSP-3::wrmScarlet abundance peaked 48 h after development during the L3/L4 stages and was reduced upon entering adulthood; in contrast, HSP-4::wrmScarlet protein levels were lowest throughout larval development and highest during early adulthood (Fig. 1a, b, Supplementary Fig. 1d). HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet levels increased throughout the worm body with increased age; maximum HSP-3::wrmScarlet protein levels was observed in day 5 adults, whereas peak HSP-4::wrmScarlet abundance occurred in day 10 adults (Supplementary Figs. 3a–d).

Representative western blot (a) and quantification (b) of PHX4377 (HSP-3::wrmScarlet) or PHX4415 (HSP-4::wrmScarlet) collected 24’, 48’, and 72’ after synchronization onto pos-1 siRNA. Membranes were probed with an anti-RFP (Chromotek, Cat #6g6) and anti-alpha tubulin (DSHB, Cat #12G10) antibody. n = 3 biological replicates. c Representative confocal images of PHX4377 and PHX4415 grown on pos-1 siRNA 24’, 48’, and 72’ after synchronization. Quantification (d) and representative confocal images (e) of PHX4377 grown on indicated siRNA and treated with 10 μg/mL of tunicamycin (Tm) or equivalent volume of M9 for 24 h. Quantification (f) and example confocal images (g) of PHX4415 grown on indicated siRNA and treated with 10 μg/mL of Tm or equivalent volume of M9 for 24 h. h Development assays of WT animals grown on indicated siRNA treated with M9 or 2.5 μg/mL of tunicamycin (Tm) as eggs. i Chronic Tm stress survival assay of WT worms grown on indicated siRNA transferred to plates treated with 20 μg/mL of Tm or equivalent volume of M9 as day 1 adults. M9 treatment: n = 110 (pos-1), n = 92 (hsp-3), n = 105 (hsp-4); Tm treatment: n = 133 (pos-1), n = 130 (hsp-3), n = 143 (hsp-4). For (c, e, g) images were taken at the midline and scalebars represent 100 μm. For (b, d, f, h) biological replicates (n = 3) are distinguished by color; triangles are average of technical replicates (circles). Source data are provided in the Source Data file. b, d–f, h Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. b pprotein x time = 0.0002; pprotein < 0.0001; ptime < 0.0001. d ptreatment x siRNA = 0.1; ptreatment < 0.0001; psiRNA < 0.0001. f ptreatment x siRNA < 0.0001; ptreatment < 0.0001; psiRNA < 0.0001. h ptreatment x siRNA < 0.0001; ptreatment < 0.0001; psiRNA < 0.0001. i Log-rank Mantel-Cox test. p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Error bars: s.d.

Next, we used confocal microscopy to determine the spatial distribution of HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet. Tissue distribution of HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet was similar and expressed throughout the body during larval development (Fig. 1c). In the early adult hermaphrodite, HSP-3::wrmScarlet was highly expressed throughout the worm body, with peak expression in the intestine and neurons. HSP-4::wrmScarlet was found in all tissues as well but at lower levels, with maximal expression observed in the spermatheca—in alignment with previously described hsp-4 transcriptional reporters34 (Fig. 1c). These HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet expression patterns were largely consistent with tissue-specific transcriptional profiles from single-cell RNA-sequencing studies and tissue-specific expression prediction programs35,36 (Supplementary Fig. 13).

These results show HSP-3 and HSP-4 protein expression is both distinct and dynamic, adapting to age-dependent needs.

BiP orthologs show different UPRER and ER-stress-responses

To define how ER stress affects HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet expression and tissue distribution, we treated day one adult worms with the SERCA inhibitor, thapsigargin (Tg), or the N-linked glycosylation inhibitor, tunicamycin (Tm) for 24 h. Tg treatment increased HSP-4::wrmScarlet, but not HSP-3::wrmScarlet levels (Supplementary Figs. 3k, l, n, o), whereas Tm exposure increased both HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet proteins (Fig. 1d–g). Tissue-specific analysis showed Tm-induced expression increases of HSP-4::wrmScarlet were observed throughout the entire worm, whereas HSP-3::wrmScarlet upregulation was primarily restricted to the intestine and head neurons (Supplementary Figs. 3e–j). HSP-3::wrmScarlet levels were unaltered by the addition a 10-fold increase in Tg concentration, suggesting HSP-3::wrmScarlet levels are insensitive to this specific ER-stressor in adult animals (Supplementary Fig. 3m).

We next assessed the involvement of the UPRER on regulating HSP-3::wrmScarlet or HSP-4::wrmScarlet protein levels in basal and ER stress conditions. ire-1 knockdown reduced HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet protein levels in control (M9)-treated animals; however, neither loss of pek-1 nor atf-6 altered protein levels of buffer-treated worms of either genotype (Fig. 1d–g, Supplementary Figs. 3k, l, n, o). HSP-3::wrmScarlet levels following Tg treatment were unaltered by knockdown of any of the individual UPRER sensors (Supplementary Figs. 3k, l), but ire-1 was required to upregulate HSP-3::wrmScarlet following Tm exposure (Fig. 1d, e). Loss of either ire-1 or atf-6 restricted the upregulation of HSP-4::wrmScarlet in response to Tg treatment (Supplementary Figs. 3n, o), whereas only ire-1 was required to upregulate HSP-4::wrmScarlet following Tm exposure (Fig. 1f, g). However, pek-1 knockdown further upregulated HSP-4::wrmScarlet in response to Tm compared to control siRNA, with strong expression observed in the intestine (Fig. 1f, g). The requirement of ire-1 to upregulate HSP-3::wrmScarlet and HSP-4::wrmScarlet was in agreement with previously published individual worm and bulk gene expression data sets of larval stage animals treated with Tm, suggesting a strong connection between hsp-3 and hsp-4 transcription and protein translation in response to ER stress34,37,38. However, the observed effects of pek-1 and atf-6 knockdown in regulating HSP-4::wrmScarlet levels under ER stress was not previously reported, to the best of our knowledge, and possibly reflect age-dependent changes in UPRER regulation.

Altogether, these data indicate IRE-1 is required for HSP-3 and HSP-4 protein expression in both stress-free and ER-stress environments. Our results further confirm divergent ER stress- and UPRER-specific responses of HSP-3 and HSP-4 expression.

Age-specific roles for HSP-3 and HSP-4 to mitigate ER stress

As HSP-3 and HSP-4 proteins exhibit significant changes in temporal and spatial expression, we hypothesized both proteins may have adopted unique roles in proteostasis maintenance and worm physiology. To test this, we assessed if HSP-3 or HSP-4 are required for worm survival following sustained ER stress induced by Tm exposure. We found knockdown of hsp-4 during development did not affect ER-stress resistance, whereas hsp-3 knockdown moderately improved tolerance to Tm-induced ER stress (Fig. 1h). Knockdown of hsp-4 significantly reduced survival when day 1 adult animals were exposed to Tm, compared to both Tm-treated animals on control siRNA and M9-treated worms on hsp-4 siRNA; in contrast, Tm treatment of worms lacking hsp-3 did not affect survival compared to Tm-treated animals grown on control siRNA (Fig. 1i, Supplementary Fig. 4a). However, M9 and Tm-treated animals grown on hsp-3 siRNA showed similar survival and were both shorter lived than M9-treated animals on control siRNA, complicating the interpretation of these findings.

Altogether, these results suggest HSP-3 and HSP-4 have age-dependent roles and requirements in mitigating exogenous ER stress.

HSP-3 or HSP-4 loss elicits distinct transcriptional changes

Similar to BiP in human cells, HSP-3 and HSP-4 are proposed to regulate UPRER-mediated gene transcription by repressing IRE-1, PEK-1, and ATF-6 in C. elegans38. To test this, we performed bulk RNA-sequencing of larval stage 4 (L4) animals with reductions of either hsp-3 or hsp-4 transcripts via RNA interference. Principal component analysis showed loss of either hsp-3 or hsp-4 resulted in distinct and consistent clustering (Fig. 2a). Next, we confirmed neither hsp-3 nor hsp-4 knockdown reduced transcription of the paralogous chaperone, indicating the target specificity of the siRNA (Fig. 2b, c).

a Principal components analysis of L4 WT (N2) worms grown on control (pos-1), hsp-3, or hsp-4 siRNA. Volcano plots of gene transcripts on hsp-3 (b) or hsp-4 (c) siRNA relative to control. Venn diagrams depicting the number distinct and overlapping genes upregulated (d) or downregulated (e) on hsp-3 and/or hsp-4 siRNA relative to control. Linear regression analyses of genes upregulated (f) or downregulated (g) in animals grown either hsp-3 or hsp-4 siRNA. Gene ontology (GO) analyses of biological processes upregulated on hsp-3 (h) or hsp-4 (i) siRNA relative to control. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of biological processes downregulated on hsp-3 (j) or hsp-4 (k) siRNA relative to control. Plots of the relative log-fold change of gene transcripts related to indicated biological processes which are altered on hsp-3 (l) or hsp-4 (m) siRNA. For all plots a cutoff of 1.5-fold change was used. Differential gene expression was determined by performing a quasi-likelihood F-test (QLF-test) for each indicated comparison (2-sided).

Compared to control (pos-1) siRNA, knockdown of hsp-3 and hsp-4 upregulated 83 and 240 distinct genes, respectively, while 126 common genes were upregulated in both conditions. Loss of hsp-3 downregulated 65 unique genes and knockdown of hsp-4 downregulated 236 different genes (Fig. 2d–g). 65 genes were downregulated in both conditions, including numerous vitellogenin genes (e.g., vit-1, vit-3, and vit-4), which encode proteins that provide nutrients to embryos during development (Fig. 2g)39. Regression analysis showed a moderate correlation (R2 = 0.43) between genes altered upon hsp-3 and hsp-4 knockdown, suggesting a partially overlapping but largely distinct transcriptional response (Fig. 2f, g). A complete list of genes altered by each condition is available in Supplementary Tables 6–8.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed worms lacking hsp-3 significantly upregulate genes related to protein refolding and chaperone production (e.g., small heat shock proteins hsp-16.2 and hsp-16.48), whereas loss of hsp-4 increased transcripts related to ER-signaling and cellular responses to stress (Fig. 2f, h, i, l, m). Loss of either hsp-3 or hsp-4 upregulated genes related the UPRER and NAD-cap decapping, which regulates RNA transcription40 (Fig. 2h, i, l, m). hsp-3 knockdown reduced transcripts involved in vitamin transport and various metabolic processes, while loss of hsp-4 reduced transcripts linked to peptidoglycan metabolism and catabolism—specifically 5 lysozyme genes (lys-1, lys-4, lys-7, lys-8, and lys-10)—as well as lipid metabolism (Fig. 2g, j–m).

These results suggest HSP-3 and HSP-4 engage in both overlapping and distinct biological pathways. Our data further imply that loss of either hsp-3 or hsp-4 results in a transcriptional response resembling the UPRER, which is supported by an increase in ER expansion observed upon hsp-3 and hsp-4 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 14a).

HSP-4 is required for fecundity and body growth

Our transcriptomic analysis showed numerous vitellogenin genes are downregulated by hsp-3 or hsp-4 knockdown (Fig. 2l, m). Furthermore, basal HSP-4::wrmScarlet expression peaks in the spermatheca (Fig. 1c) and previous data has suggested a potential role for HSP-4 in gonad development32,34. We thus hypothesized HSP-3 and HSP-4 are required for proper C. elegans reproduction. To test this, we assessed vitellogenin (VIT-1, VIT-2, and VIT-3) expression using established reporter strains41. We observed a reduction in VIT-1 and VIT-3 protein in developing eggs of day 1 adults upon loss of hsp-3 or hsp-4, consistent with the results of our RNA-seq experiments. Co-localization of VIT-1 or VIT-3 with VIT-2 was also severely diminished in developing eggs (Fig. 3a, b). In fecundity experiments, worms lacking hsp-4 laid significantly less eggs than those lacking hsp-3 or controls throughout early adulthood (Fig. 3c). Animals deficient in hsp-3 laid less eggs on day 1 but more eggs on day 3 of adulthood compared to controls, indicating a delay in egg laying (Fig. 3c). These results suggest HSP-3 and HSP-4 are required for proper yolk assembly and affect reproductive aging in C. elegans.

Representative confocal images of day 1 adult MQD2798 (vit-2(crg9070[vit-2::gfp]); vit-1(hq503[vit-1::mCherry]) (a) and MQD2775 (vit-3(hq485[vit-3::mCherry]); vit-2(crg9070[vit-2::gfp]) (b) grown on indicated siRNA. Scale bars are 50 μm. c Timed egg laying (TEL) assay of WT worms grown on indicated siRNA and day of adulthood. Each circle represents an individual worm, and each triangle represents the average of eggs laid by all worms. d Body area quantification of WT worms grown on indicated siRNA and day of adulthood. e Body area quantification of worms overexpressing (OE) DBL-1 (BW1940, (ctIs40[dbl-1(+) + sur-5::GFP])) on indicated siRNA and day of adulthood. For d, e each circle represents an individual worm, and each triangle represents the average body size of that given biological replica. For c–e biological replicates (n = 3) are distinguished by color; triangles are average of technical replicates (circles). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. c–e Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. c page x siRNA < 0.0001; page < 0.0001; psiRNA < 0.0001. d page x siRNA < 0.0001; page < 0.0001, and psiRNA < 0.0001. e page x siRNA = 0.003; page < 0.0001; psiRNA < 0.0001. p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Error bars: s.d.

As HSP-4 is required for proper cuticle formation29, we assessed if HSP-3 or HSP-4 are involved in regulating worm body growth. Worms lacking hsp-3 were similar in size to controls through early adulthood but showed a reduction in body size with age (Fig. 3d). Contrastingly, worms lacking hsp-4 failed to increase in size with age (Fig. 3d). Overexpression (OE) of DBL-1, a TGF-β ligand required and sufficient to enlarge body size in C. elegans42, did not rescue the reduction in body size of worms lacking hsp-3 or hsp-4 (Fig. 3e). These data suggest a proper balance of HSP-3 and HSP-4 is required to regulate body size in C. elegans through the engagement of non-canonical body-growth mechanisms.

Age- and tissue-specific paralog expression affect lifespan

HSP-3 and HSP-4 expression patterns show dynamic age-dependent tissue distributions (Fig. 1a–c, Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). We thus tested how loss of either paralog may affect worm lifespan. Life-long depletion of either hsp-3 or hsp-4 reduced lifespan compared to controls; however, worms lacking hsp-3 were significantly shorter lived compared to worms lacking hsp-4 (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 4b). We observed a similar trend in survival using both established null alleles of hsp-3 (hsp-3(ok1083)) and hsp-4 (hsp-4(gk514)), as well as in WT-like animals with neurons hypersensitized to RNAi43 (Fig. 4b, c, Supplementary Figs. 5a, b).

a Survival curves of WT animals grown on indicated siRNA from hatching (n = 74 (pos-1), n = 81 (hsp-3), n = 74 (hsp-4)). b Survival curves of WT (N2), RB1104 (hsp-3(ok1083)), and VC1099 (hsp-4(gk514)) grown on pos-1 siRNA (n = 93 (N2), n = 177 (RB1104), n = 138 (VC1099)). c Survival curve of animals hypersensitive to siRNA knockdown in neurons on indicated siRNA (TU3311 (uIs60[unc-119p::YFP + unc-119p::sid-1])) (n = 69 (pos-1), n = 49 (hsp-3), n = 54 (hsp-4)). Survival curves of WT worms grown on hsp-3 or hsp-4 siRNA after larval development (d) or only during larval development (e) (For d, n = 88 (pos-1), n = 60 (hsp-3), n = 63 (hsp-4); for e, (n = 95 (pos-1), n = 116 (hsp-3), n = 83 (hsp-4)). Survival curves of worms sensitive to siRNA only in the intestines (f IG1839, (frSi17[mtl- 2p::rde-1 3’UTR]; frIs7[nlp-29p::GFP + col-12p::DsRed]; rde-1(ne300))), germline (g DCL569, (mkcSi13[sun-1p::rde-1::sun-1]; rde-1(mkc36)]), muscle (h WM118, (neIs9[myo-3::HA::rde-1 + rol-6(su1006)]; rde-1(ne300)]), or neurons (i MAH677, (sqIs71[rgef-1p::GFP + rgef-1p::sid-1]; sid-1(qt9)]) on indicated siRNA (for f, n = 61 (pos-1), n = 47 (hsp-3), n = 34 (hsp-4); for g, n = 117 (pos-1), n = 108 (hsp-3), n = 103 (hsp-4); for h, n = 63 (pos-1), n = 80 (hsp-3), n = 71 (hsp-4); for i, n = 19 (pos-1), n = 59 (hsp-3), n = 38 (hsp-4)). j Survival curve of DA1116 (eat-2(ad1116)) on indicated siRNA (n = 101 (pos-1), n = 125 (hsp-3), n = 89 (hsp-4)). k Survival curve of KAE9 (seaSi40[eft-3p::fmo-2 + H2B::GFP] + [Cbr-unc-119(+)]; unc-119(ed3)]) on indicated siRNA (n = 100 (pos-1), n = 105 (hsp-3), n = 49 (hsp-4)). l Survival curve of CB1370 (daf-2(e1370)) grown on indicated siRNA (n = 142 (pos-1), n = 106 (hsp-3), n = 73 (hsp-4)). Log-rank Mantel-Cox test. p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

We then performed experiments in which hsp-3 or hsp-4 expression was reduced only during specific life stages. Knockdown of hsp-4, but not hsp-3, during adulthood was sufficient to shorten worm lifespan (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 4c). Conversely, hsp-3 loss only during larval development reduced lifespan, whereas knockdown of hsp-4 during the larval stages did not affect worm longevity (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 4d). RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that worms treated with hsp-3 siRNA only during development regained basal hsp-3 transcript levels within 48 h after completion of RNAi treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

Next, we sought to define which tissues are most dependent on HSP-3 and HSP-4 expression. Using established worm strains that enable tissue-restricted RNAi-mediated gene knockdown44,45,46, we found that life-long loss of hsp-3 in the intestine did not shorten lifespan, but intestine-specific loss of hsp-4 lead to matricide and early worm death (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 5d). Animals with hsp-3 or hsp-4 ablation in the germline only were short lived, with hsp-4 deficient worms showing a significantly more severe lifespan shortening than those lacking hsp-3 (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. 5e). Muscle-restricted knockdown of hsp-3 or hsp-4 decreased lifespan compared to controls to a similar extent (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 5f). Animals with neuron-specific loss of hsp-4 were short lived, but lifespan of worms with pan-neuronal loss of hsp-3 was similar to controls (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Fig. 5c).

These results indicate different tissue- and age-specific needs for HSP-3 and HSP-4 in regulating lifespan in C. elegans.

HSP-3 loss enhances lifespan of daf-2 mutants

We next asked if HSP-3 or HSP-4 contribute to the longevity of long-lived mutants. Loss of hsp-3 and hsp-4 reduced lifespan in a genetic model of dietary restriction, as well as in animals over-expressing Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase (FMO)-2 (Fig. 4j, k, Supplementary Fig. 6a, b)47,48. In both models, animals lacking hsp-4 were significantly shorter lived than those which lacked hsp-3 but both were shorter lived than controls (Fig. 4j, k, Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Together, these data indicate HSP-3 and HSP-4 contribute to dietary restriction-mediated longevity. hsp-4 knockdown significantly shortened lifespan in insulin-signaling deficient daf-2(e1370) mutants49, but loss of hsp-3 significantly extended their longevity (Fig. 4l, Supplementary Fig. 6c). Combined, these data suggest HSP-3 and HSP-4 play dynamic roles in regulating different models of longevity in C. elegans.

HSP-4 loss improves protein misfolding-induced paralysis

We next tested if HSP-3 or HSP-4 were required to buffer against protein aggregation-induced ER stress. Although there is a lack of ER-specific protein aggregation models in C. elegans, there is evidence which suggests unrestricted HSP-3 and HSP-4 affect protein aggregation dynamics of misfolding polyQ::YFP outside of the ER30. Furthermore, hsp-3 and hsp-4 transcripts are upregulated in animals expressing human amyloid beta (aβ1-42) in the body wall muscle50,51, suggesting the possibility HSP-3 and HSP-4 may help mitigate aβ1-42-induced protein misfolding stress. Therefore, we assessed aβ1-42-mediated paralysis in hsp-3- and hsp-4-deficient worms at aggregation-restrictive (20 °C, “non-inducive”) and permissive (25 °C, “inducive”) temperatures. At permissive temperatures, hsp-3 and hsp-4 loss significantly increased the paralysis rates in aβ1-42-expressing worms compared to controls (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Consistent with trends observed in lifespan assays (Fig. 4a–c), loss of hsp-3 increased the rate of worm paralysis compared to worms lacking hsp-4 (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Worms lacking hsp-3 showed similar rates of paralysis at both the inducive and non-inducive temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 7a). However, loss of hsp-4 at the inducive temperature reduced the rate of paralysis compared to control siRNA (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 7a).

GMC101 (dvIs100[unc-54p::A-beta-1-42::unc-54”-UTR]) paralysis assays at 20 °C (a) and 25 °C (b). Number of animals and median paralysis data is in Supplementary Table 5. HE250 (unc-52(e669su250)) (c) and CB1157 (unc-54(e1157)) (d) paralysis assays scored 48 h post-transfer to 25 °C as day 1 adults. Biological replicates distinguished by color (n = 3); triangles: average of technical replicates (circles). Western blot (e) and quantifications (f, g) of day 1 adult DA2123 (adIs2122[lgg-1p::GFP::lgg-1) on indicated siRNA. h Representative confocal images of day 1 adult MAH215 (sqIs11[lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1]) on indicated siRNA. Arrows: autophagosome and autolysosome. Scale bars: top three rows (20 μm); inset (5 μm). i. Representative confocal images of day 1 adult MAH215 1 h post-exposure to 100 μM of bafilomycin (BafA) or equivalent volume of DMSO. Scale bar: 20 μm. Representative western blot (j) and quantifications (k, l) of day 1 adult DA2123 grown on indicated siRNA. Representative western blot (m) and quantification (n) of DA2123 (“WT”) and MTX339 (“XBP-1s OE”; adIs2122[lgg-1p::GFP::lgg-1]; agd925[sur-5p::xbp-1s; myo-2::rfp]). Membranes were probed with an anti-GFP (Roche, Cat #11814460001) and anti-alpha tubulin antibody (DSHB, Cat #12G10). f, g, k, l, n Shapes represent biological replicates (n = 3). Source data are provided in the Source Data file. a, b Log-rank Mantel-Cox test. c, d Two-way ANOVA followed by Uncorrected fisher’s LSD. c ptemperature x hsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001; ptemperature < 0.0001; phsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. d ptemperature x hsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001; ptemperature < 0.0001; phsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. f, g One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. k, l, n Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. k pUPRER siRNA x hsp-4 siRNA = 0.005; pUPRER siRNA = 0. 1; phsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. l pUPRER siRNA x hsp-4 siRNA = 0.08; pUPRER siRNA = 0.1; phsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. n pgenotype x hsp-4 siRNA = 0.07; pgenotype=0.001; phsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Error bars: s.d.

Given the unexpected finding hsp-4 knocked delayed paralysis in aβ1-42-expressing animals, we then wondered if the loss of hsp-4 could delay paralysis in other established protein misfolding models. Knockdown of hsp-4 significantly decreased paralysis of animals with loss of function mutations in the C. elegans’ HSPG2 ortholog52, as well as animals with a temperature-sensitive loss of function allele in the worm ortholog of Myosin Heavy Chain II53, after both 24 and 48 h following transfer to 25 °C (Fig. 5c, d, Supplementary Fig. 7b–d). In contrast, hsp-3 knockdown did not alter paralysis after 24 h in all models tested, but we observed an ~8–9% reduction in paralyzed animals after 48 h in the inducive condition compared to controls (Supplementary Figs. 7g–j). hsp-4 knockdown delayed paralysis in worms with a loss of function mutation in the ortholog of human UNC45B54 and delayed uncoordinated-related paralysis in animals which express pan-neuronal human TDP-4355 (Supplementary Figs. 7e, f). Notably, we did not observe changes in paralysis upon knockdown of hsp-3 or hsp-4 at the non-inducive temperature (15 °C) in any paradigm assessed (Fig. 5c, d, Supplementary Figs. 7b–j).

As a whole, these data suggest loss of hsp-4 broadly improves stress resistance against numerous protein misfolding stressors across different tissues.

HSP-4 knockdown increases autophagy through IRE-1

The finding that loss of hsp-4 improved stress tolerance in multiple protein misfolding models was unexpected. Thus, we hypothesized that loss of hsp-4 triggers an increase in cytosolic protein turnover through an unknown protein degradation mechanism, such as autophagy.

Autophagy maintains proteostasis by delivering cargo in autophagosomes to lysosomes for protein degradation and recycling56. Autophagosome formation requires cytosolic ATG8/LC3, which is recruited to and subsequently incorporated into autophagosome membranes (i.e., lipidated); upon fusion with the lysosome, contents of the newly-formed autolysosome are then degraded57. In C. elegans, relative autophagic activity (autophagic flux) can be assessed by probing lysate of worms expressing a GFP::LGG-1 (LC3 ortholog) fusion protein via immunoblotting. This method allows for delineation of the total abundance of GFP::LGG-1, lipidated GFP::LGG-1 (reflective of total autophagosomes), and processed GFP (reflective of autolysosomal degradation)58.

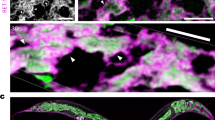

To test our hypothesis, we knocked down hsp-3 or hsp-4 in these GFP::LGG-1 expressing worms59. hsp-3 loss did not affect GFP::LGG-1 processing or lipidation; however, hsp-4 knockdown significantly increased the amount of both lipidated and processed GFP::LGG-1 (Fig. 5e–g, Supplementary Fig. 8a). We confirmed these results using a second model to observe autophagosome formation and processing, in which LGG-1 is fused with both mCherry and GFP60. Since GFP is quenched by the acidic lysosomal environment while mCherry is resistant to pH-dependent quenching, this model can distinguish between autophagosomes (GFP- and mCherry-positive) and autolysosomes (mCherry-positive). We observed the formation of large GFP/mCherry-positive vesicles upon hsp-4 knockdown which was not observed upon pos-1 or hsp-3 RNAi (Fig. 5h). Treatment of these animals with the autolysosome formation inhibitor, bafilomycin, lead to an abundance of GFP- and mCherry-positive vesicles in hsp-4 knockdown animals compared to controls (Fig. 5i, Supplementary Fig. 15a). Together, these results suggest that loss of HSP-4, but not HSP-3, increases autophagy in C. elegans.

To test if the upregulation of autophagy upon hsp-4 loss was mediated through the UPRER, we knocked down hsp-4 in combination with ire-1, pek-1, or atf-6 in GFP::LGG-1 expressing animals. ire-1;hsp-4 double-knockdown prevented the increase in GFP::LGG-1 lipidation and processing, whereas the simultaneous knockdown of pek-1 or atf-6 with hsp-4 still resulted in increased autophagy (Fig. 5j–l, Supplementary Fig. 8b). Using RT-qPCR, we confirmed hsp-4 knockdown efficiency was unaffected by combinations of siRNA in all conditions (Supplementary Figs. 8c–e).

To determine if canonical IRE-1 signaling was sufficient to increase autophagy akin to hsp-4 knockdown, we overexpressed spliced XBP-1 in GFP::LGG-1 animals using established alleles61. Spliced XBP-1 OE increased autophagy compared to WT controls, but hsp-4 knockdown further boosted GFP::LGG-1 processing compared to control siRNA in these worms (Fig. 5m, n, Supplementary Fig. 9a). These results suggest the upregulation of autophagy upon hsp-4 knockdown requires IRE-1 but is at least partially independent of canonical IRE-1/XBP-1 signaling.

HSP-4 knockdown boosts autophagy via Sec-62/C18E9.2

Given IRE-1, but not XBP-1 signaling, was required to upregulate autophagy upon hsp-4 knockdown, we next tested if loss of hsp-4 triggered an increase in autophagy via an unidentified conserved ER-Phagy receptor in C. elegans. To test this, we screened all known ER-Phagy receptors predicted to be conserved in C. elegans (C18E9.2/Sec-62, RET-1/RTN3, CDKR-3/CDK5, and ATLN-1/ATL3). C18E9.2;hsp-4 double knockdown inhibited the upregulation of GFP::LGG-1 lipidation and processing (Fig. 6a–c, Supplementary Fig. 9b). In agreement with these results, we did not observe the formation of GFP/mCherry-positive vesicles in mCherry::GFP::LGG-1-expressing animals in which we knocked down both C18E9.2 and hsp-4 (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Fig. 15b). hsp-4 knockdown efficacy was unaffected by combinatory knockdown with C18E9.2 siRNA (Supplementary Figs. 9c–e). Combinatorial knockdown of hsp-4 with neither ret-1 nor cdkr-3 prevented the induced upregulation of LGG-1 processing and lipidation (Supplementary Figs. 10a–f). Furthermore, upon hsp-4 knockdown, atln-1 KO animals showed a similar upregulation of GFP::LGG-1 processing compared to WT controls but reduced GFP::LGG-1 lipidation (Supplementary Figs. 10g–i). Altogether, these results suggest the primary upregulation of autophagy triggered by hsp-4 knockdown is mediated through C18E9.2.

Western blot (a) and quantifications (b, c) of day 1 adult DA2123 (adIs2122[lgg-1p::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6(su1006)]) grown on indicated siRNA and probed with an anti-GFP (Roche, Cat #11814460001) and anti-alpha tubulin antibody (DSHB, Cat #12G10). Shapes represent biological replicates (n = 3). d Representative confocal images of day 1 adult MAH215 (sqIs11[lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6) on indicated siRNA. Scale bars are 20 μm. GMC101 (dvIs100[unc-54p::A-beta-1-42::unc-54’‘-UTR + mtl-2p::GFP]) paralysis assays at the non-inducive (e) and inducive temperatures (f). HE250 (unc-52(e669su250)) (g) and CB1157 (unc-54(e1157)) (h) paralysis assays grown on indicated siRNA scored 48 h post-transfer to 25 °C as day 1 adults. i Survival curves of WT worms on indicated siRNA. j Body area quantification of WT worms on indicated siRNA and day of adulthood. Western blot (k) and l quantification of co-immunoprecipitation assays of Tm-treated A549 cells pulling on IRE-1 and probed for IRE-1 (Cell Signaling, Cat #3294S; Rabbit IgG, Cell Signaling, Cat #7074S), Sec-62 (Abcam, Cat #EPR9212; Light Chain-Specific Rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, Cat #D4W3E), and BiP (Proteintech, Cat #66574; Mouse IgG, Cell Signaling Cat #7076S). Number of animals and median lifespan/paralysis data is in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. For g, h, j, l biological replicates (n = 3) are distinguished by color; triangles are average of four technical replicates (circles). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. b, c, g, h, j Two-way ANOVA followed by Uncorrected fisher’s LSD: b pC18E9.2 siRNA x hsp-4 siRNA = 0.003; pC18E9.2 siRNA = 0.001; phsp-4 siRNA = 0.001. c pC18E9.2 siRNA x hsp-4 siRNA = 0.01; pC18E9.2 = 0.07; phsp-4 siRNA = 0.01. g pC18E9.2 siRNA x hsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001; pC18E9.2 siRNA < 0.0001; phsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. h pC18E9.2 siRNA x hsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001; pC18E9.2 siRNA < 0.0001; hsp-4 siRNA < 0.0001. j psiRNA x age < 0.0001; psiRNA < 0.0001; page < 0.0001. (e, f, g). Log-rank Mantel-Cox test. p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Error bars: s.d.

Given C18E9.2 lacks a predicted luminal HSP70-binding J-domain, a direct interaction of HSP-4 with C18E9.2 would be unlikely. We thus asked if HSP-4’s regulation of C18E9.2 was indirect through the J-domain containing Sec-63 ortholog and Sec-62/C18E9.2 binding partner, DNJ-29. In human cells, BiP binds to the J-domain of Sec-63 to assist in protein refolding through the Sec-61/Sec-62/Sec-63 protein translocation complex62,63. However, both hsp-4;dnj-29 double knockdown still exhibited enhanced autophagy (Supplementary Figs. 10j–l).

As a whole, our work supports a model in which HSP-4, but not HSP-3, regulates ER-cytosolic crosstalk and autophagy through engagement of the ER-Phagy receptor C18E9.2/Sec-62 and IRE-1, but is independent of canonical IRE-1 signaling.

C18E9.2 is required for select HSP-4-specific phenotypes

Having established direct links between HSP-4, C18E9.2, and autophagy, we repeated the previously shown paralysis assays to determine whether C18E9.2 is required for the observed reductions in paralysis upon hsp-4 knockdown (Fig. 5a–d). hsp-4;C18E9.2 double knockdown did not alter the rate of paralysis of aβ1-42-expressing worms compared to hsp-4 knockdown alone at the non-inducive temperature (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Fig. 11b). At the inducive temperature, C18E9.2 knockdown alone reduced paralysis compared to control siRNA; however, double knockdown of C18E9.2 and hsp-4 at the inducive temperature increased the rate of paralysis back to that of controls (Fig. 6f, Supplementary Fig. 11b). Furthermore, C18E9.2 was required to delay paralysis in hsp-4 deficient animals in all previously described models which we assessed (Fig. 6g, h, Supplementary Figs. 11d, e). We then tested if C18E9.2 was required for the changes in lifespan, body size, and fecundity we observed in hsp-4 deficient animals. Loss of C18E9.2 alone slightly extended lifespan, but animals with knockdown of hsp-4 and C18E9.2 together were shorter lived than those lacking hsp-4 and controls (Fig. 6i, Supplementary Fig. 11a). Furthermore, worms lacking both C18E9.2 and hsp-4 were significantly larger than worms lacking hsp-4 alone but were still stunted in growth compared to controls (Fig. 6j). However, knockdown of C18E9.2 was not sufficient to rescue the egg laying deficiency of hsp-4 knockdown worms (Supplementary Fig. 11c).

These data suggest that hsp-4 loss increases autophagy through the ER-Phagy receptor, C18E9.2, and is required for resistance to protein misfolding-induced paralysis and blunted body growth upon hsp-4 knockdown. However, the observed decreases in fecundity and lifespan upon hsp-4 knockdown are not linked to C18E9.2-dependent autophagy.

ER-stress alters IRE-1 and Sec-62 interaction in human cells

Given our worm data linking orthologs of BiP, Sec-62, and IRE-1 independently of spliced XBP-1 signaling, we hypothesized that ER stress induces BiP to release IRE-1, enabling IRE-1 to bind Sec-62 and enhance autophagy in mammalian cells. This model predicts BiP binding to IRE-1 limits IRE-1/Sec-62 interaction. To test this, we stressed A549 cells with Tm for 24 h, followed by a 24-h recovery and subsequent immunoprecipitation of IRE-1. This process increases autophagy (Supplementary Fig. 12b). In line with our hypothesis, Sec-62 co-immunoprecipitated with IRE-1, but increased BiP/IRE-1 binding correlated with reduced Sec-62 pulldown (Fig. 6k, l, Supplementary Fig. 12a). Thus, BiP represses IRE-1 to limit autophagy by modulating IRE-1 and Sec-62 interaction (Fig. 7).

Created in BioRender Urban, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/c23g777 (left). Created in BioRender. Urban, N. (2025) https://BioRender.com/n51o675 (right).

Discussion

In this study, we define how two C. elegans’ BiP orthologs, HSP-3 and HSP-4, functionally overlap and diverge to maximize ER stress resilience and contribute to worm physiology. We define distinctive roles for both paralogs in ER and non-ER stress resistance, reproduction, body size growth, lifespan, and autophagy regulation. Our results suggest a conserved mechanism linking HSP-4/BiP-mediated regulation of IRE-1 to C18E9.2/Sec-62-associated autophagy. Altogether, these data define largely distinct roles for HSP-3 and HSP-4 in orchestrating a variety of physiological functions.

Previous studies suggested compensatory regulation between hsp-3 and hsp-4, but tissue-specific paralog functions have been reported, such as HSP-4’s involvement in cuticle function and paralog-specific roles in gonadal and intestinal development28,29,32. Our RNA-sequencing (Fig. 2), ER-stress resistance (Fig. 1), lifespan (Fig. 4) and autophagy regulation data (Figs. 5–6) further support the notion these proteins are functionally distinct. Our temporal and tissue-specific analysis of HSP-3 and HSP-4 in the context of lifespan (Fig. 4), ER-stress resistance (Fig. 1h, i), and protein expression (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2) suggest a greater diversification of HSP-3 and HSP-4 function within individual tissues at distinct life stages. Together, these data suggest there are aging-specific demands which may require a switch in protein quality control mechanisms from direct chaperone-mediated protein (re)folding to broader transcriptional regulation with increased age. We thus postulate that HSP-3 and HSP-4 evolved divergent roles supporting distinct aspects of the worm’s life cycle. Altogether, our data are consistent with a model in which HSP-3 largely represents the canonical ER-resident HSP70 chaperone responsible for de novo and misfolded protein (re)folding, while HSP-4 is primarily engaged in orchestrating interorganellar signaling and ER stress mitigation pathways (Fig. 7). However, our understanding of the tissue- and-age-specific mechanism(s) by which HSP-3 and HSP-4 regulate proteostasis remains incomplete.

We identified two contexts in which hsp-3, but not hsp-4, knockdown improved survival (Figs. 1h, 4l). Previous work showed that hsp-3 knockdown in polyQ-expressing animals upregulates non-ER resident HSP16 and HSP70 family chaperones, providing additional support to improve stress resistance to polyQ-aggregation stress during development30. The RNA-sequencing results presented here (Fig. 2) confirm these results and show that loss of hsp-3 in wild type animals also upregulates small heat shock proteins (e.g., hsp-16.1, hsp-16.2, hsp-16.48) and cytosolic HSP70s (e.g., hsp-70). It is plausible this upregulation of cytosolic chaperones may contribute to the improved development and survival in these contexts.

Our paralysis experiments (Fig. 5a–d, Fig. 6e–h, Supplementary Figs. 7 and 11) suggest the hsp-4 knockdown-induced autophagy upregulation primes the worm to temporarily combat protein-misfolding stress but does not fully explain other hsp-4 knockdown-specific phenotypes (e.g., reductions in lifespan, body size, and egg laying) (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 11). Furthermore, this upregulation is insufficient to counteract ER-specific stress, as hsp-4 knockdown animals treated with Tm are short lived (Fig. 1). This suggests HSP-4 function extends beyond regulating autophagy, likely including roles in protein refolding and regulating other ER stress responses. Building on these worm findings, our human cell data suggest a possible relationship where the binding of BiP to IRE-1 regulates a direct interaction between IRE-1 and the ER-Phagy receptor, Sec-62. We postulate this interaction enhances the recruitment of LC3 to the LC3-binding domain of Sec-62, thus stimulating increases in ER-membrane protein-mediated autophagy (Fig. 7). This model aligns well with recent data in which IRE-1 was suggested to indirectly alter ER-Phagy64.

While the tools to study ER-phagy in mammalian cells are relatively new but rapidly expanding, there are currently no such tools available to study ER-Phagy in C. elegans. Our experiments identify ER membrane-resident C. elegans proteins and receptors (e.g., ortholog of the mammalian ER-phagy receptor, Sec-62), which mediate the observed physiological changes and phenotypes. While these proteins are conserved across species and strongly suggest the phenotypes are a result of ER-Phagy, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that macroautophagy or other forms of autophagy may be contributing as well. Similarly, while our analysis of the development of the HSP-3::wrmScarlet- and HSP-4::wrmScarlet-expressing animals suggests that these mutant proteins are functional enough for development, we also cannot exclude the possibility that the enzymatic activity of these proteins may not be completely identical to WT proteins due to lack of HSP-3 and HSP-4-specific activity assays in vivo.

In summary, we identify both redundant and specialized functions for HSP-3 and HSP-4 and propose a BiP-dependent mechanism controlling ER proteostasis through Sec-62-mediated autophagy. These findings underscore the importance of distinguishing individual paralog functions to understand conserved proteostasis mechanisms across species.

Methods

C. elegans maintenance and strains

Worms were maintained at 20 °C on peptone rich (8P) nematode growth media (NGM) plates spotted with OP50-1 E. coli (Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC)), except for those noted in Supplementary Table 1 that were maintained at 15 °C. All experiments were performed at 20 °C unless otherwise stated. Worms were fed for at least two generations before being used for experiments. Hermaphroditic animals were used in all experiments. A detailed list of strain information can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Strains were backcrossed at least 3–5x to N2 worms prior to use in experiments, except RB1104 and VC1099 due to sterility issues upon backcrossing. All strains used in this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Generation of reporter strains

PHX4377 (hsp-3::wrmScarlet) and PHX4415 (hsp-4::wrmScarlet) were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology by SunyBiotech (Fujian, China). wrmScarlet sequences were inserted immediately upstream of the XDEL sequence of the endogenous hsp-3 or hsp-4 locus. All strains were backcrossed at least 3–5x to N2 worms prior to use in experiments.

Gene knockdown via RNA interference

HT115 E. coli expressing siRNA against the gene of interest are from either the Vidal or Ahringer siRNA library and described in Supplementary Table 2. To prepare siRNA, single E. coli colonies were inoculated into 5x cultures of Lauria broth (LB) media (Genesee Scientific, Cat #11-118) supplemented with 100 mg/mL carbenicillin (diluted 1:1000, GoldBio, Cat #C-103-25) and shaken overnight (37 °C). The following day, the 5x culture was spun down at 2633 × g for 10–15 min. The supernatant was removed, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 1x fresh LB media (e.g., 5 mL of overnight culture resuspended in 1 mL of fresh LB). 100 mg/mL carbenicillin (diluted 1:1000) and 1 M isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (diluted 1:200; Dot Scientific, Cat #DSI5600-25) were added to the 1x culture. Bacteria were spotted on standard nematode growth media (NGM) plates supplemented with 1 M IPTG (1:1000, induces siRNA expression), 100 mg/mL carbenicillin (1:1000, antibiotic) and 10 mg/mL nystatin (1:1000, antifungal; Dot Scientific, Cat #DSN82020-10). Once dry, plates were used immediately or kept at 4 °C for no more than 2-3 days. For all double knockdown experiments (e.g., hsp-4/C18E9.2), equal amounts of siRNA with similar OD were mixed in a 1:1 ratio to account for any potential dosage effects on siRNA efficacy and single knockdown controls were mixed with equal volumes of pos-1 siRNA as indicated in the figure. Knockdown of all siRNA used in this study were validated previously30 or via here RT-qPCR (see RT-qPCR and Supplementary Figs. 1, 9, and 10) using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. A qualitative plate of a 1:1 mixture of E. coli expressing hsp-3 and hsp-4 was used to ensure functional siRNA for all experiments (data not shown).

Synchronization via hypochlorite treatment

Heterogeneously aged worms were washed in 1–2 mL of M9 buffer and collected in a 1.7 mL Eppendorf tube. Worms were gravity separated for 3–5 min and washed with fresh M9 (repeated 3-4x). M9 was then removed and replaced with 1 mL of hypochlorite solution (56 mL ddH2O, 14.4 mL 5 N NaOH, 7.2 mL 7.55% bleach). Tubes were shaken at 1200 rpm in a tabletop heat block at 20 °C for 7–10 min until worm bodies were not observed. Eggs were spun at 1600 rcf for 30 s, bleach was removed, and eggs were washed with 1 mL of M9. Washing was repeated twice. Eggs were washed a final time with M9 and spun at 2900 rcf for 3 min, resuspended in ~100 μL of M9, and plated.

C. elegans development assays

HT115 E. coli expressing the designated siRNA were prepared and spotted onto NGM/RNA interference plates as described above (see Gene knockdown via RNA interference). Worms were synchronized and eggs were spotted onto NGM/RNA interference plates. Total eggs were counted, and plates were incubated in a 20 °C incubator for the time described in the figure. The number of larval stage 4 worms or older were then scored and compared to the number of eggs on the plate. For super plots, biological replicates are distinguished by color. Circles represent individual technical replicates and triangles represent the average development of each biological replicate.

RNA-extraction, cDNA generation, and RT-qPCR analysis

Worms were synchronized and grown on the described siRNA for 72 h unless otherwise stated. For RNA extraction, ~500-1000 worms were washed 3x via gravity separation in M9 and lysed using the Direct-zolTM RNA MiniPrep Plus Kit (Zymo Research, Cat #R2070) following the manufacturers instruction in a Qiagen TissueLyser III (5 min, 30 Hz). cDNA generation was completed using Applied Biosystems™ High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Fisher Scientific, Cat #43-688-14) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR analysis was done using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix for RT-qPCR (Applied Biosystems™, Cat #A25742) master mix. Primers used for RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

C. elegans fluorescent image acquisition and analysis

For tunicamycin, thapsigargin, and aging imaging assays, worms were immobilized in 10 μL of 25 mM tetramisole hydrochloride (Santa Cruz, Cat #sc-215963) dissolved in M9 buffer, placed on a 2% agarose pad on a glass microscope slide, and covered with a round glass coverslip. For quantification analysis, worms were imaged using a Keyonce BZ-X700 fluorescent microscope at 10x magnification. Image analysis was done using a custom generated semiautomatic pipeline in Cell Profiler (version 4.2.1). This pipeline is available online (https://github.com/urbanni/BiP-Orthologs.git) and images are available on Zenodo (see “Data Availability”). Representative confocal images for Tm experiments were taken using a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal laser scanning microscope. Representative worms were straightened using the “Straighten” feature in Fiji (version 2.14). For MAH215 (sqIs11[lgg-1p::mCherry::GFP::lgg-1 + rol-6]) imaging, day 1 adult animals were immobilized in 10 μL of 0.01% NaN3 dissolved in sterile M9. For ER-morphology experiments, an agarose mounting pad (10% agarose in M9 buffer) was prepared prior to imaging by briefly heating the agarose solution and flattening it between two slides (#1.5, VWR). Approximately 3 μL of 0.1 μm Polybead microsphere suspension (Polysciences) was added to the pad. Gravid day 1 adult worms were picked into the bead solution, and a coverslip (#1.5, VWR) was added to immobilize the worms. Imaging was performed on an Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope with a Yokogawa CSU-W1 spinning disc (Nikon), a Plan Apo λ objective (100×/1.45) (Nikon) using type LDF immersion oil (Cargille Labs), and a Prime 95B sCMOS camera (Teledyne Photometrics). GFP::SEC-61.B was imaged using 488 nm excitation (dichroic mirror Di01-T405/488/568/647-13 × 15 × 0.5 (Semrock)), with an ET525/36 m emission filter (Chroma). Additionally, DIC images (89101 m emission filter) and autofluorescence images were obtained for each worm to identify gut granules. Focal planes were selected at nuclear midlines for intestinal ring int1 and the anterior region of hypodermal hyp7. For analysis of ER-morphology, images were blinded with a Fiji script called blind-files, provided as part of the Lab-utility-plugins update site. Then, files were subjected to automated 2-D deconvolution, denoising via the Denioise.ai module, and rolling-ball background removal with identical settings for each tissue in NIS-Elements Advanced Research (NIS-AR, Nikon). For intestinal images, the Qualitative Annotations plugin in Fiji was used to score ER morphology. For hypodermal images, a ROI was drawn on the hypodermis (excluding nuclei) in NIS-AR, and ER intensity and morphologic features were measured on segmented images, using the same threshold for all images. Images were taken in two independent repeats, and data were pooled prior to statistical analysis. Prism (v10, GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis and plot generation. Statistical tests, p-values, and sample sizes are indicated in figure legends.

Bafilomycin (BafA) treatment

Animals were synchronized and maintained at 20 °C for 3 days. 50 mM stocks of Bafilomycin A1 (“BafA”), AdipoGen Life Sciences, Cat #AG-CN2-2001-M001) dissolved in DMSO or equivalent amount of DMSO were diluted to 100 uM in ddH2O and brought to the equivalent volume of bacteria spotted on the plate (e.g., 500 uL BafA solution for 500 uL of spotted bacteria). Solution was spread across the bacterial lawn and left to dry in the dark. Once dry, plates were kept in the dark for 1 h, then animals were transferred to the treated plates. Images were taken 1 h following transfer.

ER stress, development, and survival assays

Worms were synchronized and grown on the described siRNA for 72 h. Thapsigargin (Invitrogen, Cat #T7458) was dissolved in DMSO to a final concentration of 1 mM. Tunicamycin (Tocris Biosciences, Cat #35-161-0) was dissolved in basic M9 (pH 9.5–10) to a final concentration of 1.0 mg/mL. Plates were spotted with the amount of Tg or Tm as described in the figure and figure legend 24 h before eggs or animals were transferred and stored at 4 °C overnight. For both florescence imaging and survival assays, day 1 adult worms were transferred to a chemical or solvent treated plate and kept at 20 °C. Images were taken 24 h after transfer unless otherwise stated. Development assays were scored for the presence of L4 or older animals 72 h after synchronization.

Bulk RNA-sequencing and analysis

Synchronized N2 worms were exposed to siRNAs as described above and maintained for 48 h (until approximately larval stage 4). Animals were collected, washed repeatedly with M9 as described above, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until processing. RNA extraction was done as described above (see RNA-extraction, cDNA generation, and RT-qPCR analysis). Three biological replicates were collected and then processed by the University of Michigan Advanced Geonomics Core. The library was prepared using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB, Cat #E7490L) and NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, Cat #E7770L). Sample sequencing was done using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4. The reference genome, Wbcel235, was used to map reads using STAR (v2.7.8a)65 and count estimates were assigned using RSEM (v1.3.3)66. Differential expression analysis was performed with edgeR (v3.19, Bioconductor)67. ShinyGO (v0.80)68 was used to generate graphical representations of enriched gene ontology (GO) terms. Volcano plots were generated using the EnhancedVolcano package (v.1.22.0)69. 1.5-fold change was used as a cutoff for differential expression. Raw data of RNA-sequencing experiments were disclosed in Van Pelt et al.30 and reanalyzed for this publication. RNA-sequencing data can be found in Supplementary Tables 6–8.

Timed egg laying (fecundity) assays

Worms were synchronized onto HT115 E. coli expressing the described siRNA and maintained for 72 h. Worms were transferred to 35 mm NGM-IPTG plates spotted with 150 μL of the described siRNA-expressing bacteria and maintained at 20 °C for 3.5 h (1 worm per plate). Following the timed egg lay, worms on the same siRNA were then transferred to a shared 60 mm NGM-IPTG plate of the described siRNA and maintained at 20 °C until the next timepoint. Total number of eggs laid on each plate were then counted. Timed egg lays began 72 h (Day 1), 144 h (Day 3), and 192 h (Day 5) after synchronization.

Body area assays

Worms were synchronized onto HT115 E. coli expressing the described siRNA. Animals were imaged 72 h (Day 1), 144 h (Day 3), and 192 h (Day 5) after synchronization. Worms were transferred to fresh siRNA plates after imaging was complete on Day 1 and Day 3 to maintain cohort synchronization. Image analysis was done using a custom generated semiautomatic pipeline in Cell Profiler (version 4.2.1) described above (see C. elegans florescent image acquisition and analysis).

C. elegans lifespan assays

Worms were synchronized and transferred to assay plates 72 h. For knockdowns “From Birth”, eggs were spotted directly on HT115 E. coli expressing siRNA and remained on that siRNA for the duration of the experiment. For knockdowns during “Adulthood Only”, worms were synchronized onto pos-1 siRNA against and transferred after 72 h to the indicated siRNA. For knockdowns during the “Larval Only” stages, worms were synchronized onto the described siRNA and maintained for 72 h, then transferred to pos-1 siRNA for the remainder of the experiment. Worms were transferred 5-10 min to an intermediate plate without bacteria to rid worms of previous siRNA before being transferred to fresh plates. Worms were transferred every ~48 h to fresh plates for the first 6–7 days as needed to maintain a synchronized population as needed. Worms were scored as alive or dead every 1–2 days; worms which failed to produce movement spontaneously or after being gently prodded with a platinum worm pick were considered dead and removed. Unless otherwise stated, all siRNA experiments were “From Birth”. Each biological replica is the aggregate of 3 technical replicas (individual NGM/siRNA plate). All experiments were done at 20 °C, with the exception of long-lived mutants which were allowed to develop at 15 °C until they reached adulthood, in which time animals were then transferred to 20 °C. the number of animals and median lifespan data per experiment is in Supplementary Table 4.

Paralysis assays

For GMC101 (dvIs100 [unc-54p::A-beta-1-42::unc-54 3’-UTR + mtl-2p::GFP]) animals were synchronized onto the indicated siRNA and grown at 20 °C for 72 h. Worms were then moved to 60 mm plates containing fresh siRNA and transferred to either a 20 °C (non-inducive) or 25 °C (inducive) incubator. Animals were scored for paralysis every 1–2 days, and paralyzed worms were removed from the plate. For HE250 (unc-52(e669su250)), CB1157 (unc-54(e1157)), CB286 (unc-45(e826)), and CL6049 (dvIs62 [snb-1p::hTDP-43/3’ long UTR + mtl-2p::GFP]), animals were synchronized onto indicated siRNA and grown at 15 °C for 5 days. Then day 1 adults were transferred to 25 °C and scored accordingly. Paralysis was defined as the inability to complete a full body movement in either direction spontaneously or when prodded with a platinum wire worm pick. If needed, worms were transferred to fresh plates after 2 and 4 days of adulthood to maintain a synchronized cohort and ensure adequate food availability. After all control worms at the inducive temperature paralyzed, the remaining non-paralyzed worms were counted and censored. Number of animals paralyzed/censored and day of median paralysis data per experiment is in Supplementary Table 5.

C. elegans protein lysate preparation

Synchronized worms were washed with sterile M9 into a 1.7 mL Eppendorf tube and washed 2-3x using gravity separation. Thereafter, the remaining M9 was removed after brief centrifugation. Worms were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Frozen samples were resuspended in 150–200 μL of sterile filtered worm lysis buffer (HEPES (20 mM, 7.4 pH), NaCl (20 mM), MgCl2 (200 mM), and Nonidet P-40 (0.5%)) spiked with protease inhibitor cocktail (PierceTM Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets, EDTA-free, ThermoFisher, Cat #A32961), transferred to reinforced tubes containing a steel lysis ball, and mechanically lysed using a Qiagen TissueLyser III (7.5 min, 30 Hz). Lysate was cleared at 16,100 rcf (4 °C, 15 min) twice, transferring to a precooled tube after each transfer. The soluble fraction was collected, and protein lysate concentration was determined using the PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher, Cat #23227) following the manufacture’s instruction. For western blot, equal amount of protein lysate was brought to equal volume with worm lysis buffer and combined with 4x Laemmli Protein Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad, Cat #1610747) prepared per the manufacturer’s instruction. Samples were boiled for 5 min at 100 °C, allowed to cool, and excess moisture was spun down briefly using a tabletop centrifuge. Samples were then used immediately or stored at −20 °C.

Immunoblotting

Prepared protein lysates were subject to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes using the Bio-Rad Trans-Blot® Turbo System (Bio-Rad, Cat #1704150) and Trans-Blot® Turbo RTA Transfer Kit, PVDF (Bio-Rad, Cat #1704272). Membranes were then trimmed and blocked at least 1 h at room temperature with gentle rocking. The blocking buffer was then removed, and membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C with gentle rocking. Primary antibody was then removed, and membranes were washed 3× (5–10 min each) with 0.1% TBS-T. Membranes were then incubated and gently rocked with HRP-conjugated secondaries 1 h. Antibody was removed and membranes were washed 3x with 0.1% TBS-T (5 min each). HRP-conjugates were detected using ProSignal Dura ECL Reagent (Prometheus Protein Biology Products, Genesee Scientific, Cat #20-301) following the manufacturer’s instructions and imaged using an Invitrogen iBright1500. If required, membranes were stripped using OneMinute® Western Blot Stripping Buffer (GM Biosciences, Cat #GM6001) following the manufacturers instruction, washed vigorously with ddH2O, then rehydrated in 0.1% TBS-T for 10 min. Membranes were then treated as described above. Immunoblot quantification was done using Fiji (version 2.14). A list of blocking buffers, antibodies, and dilutions used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 3. No adjustment was done to the blots following image acquisition. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1, 8, 9, 10, and 11.

A549 cell maintenance and tunicamycin treatment

A549 cells were obtained from ATCC (Cat # CCL-185) and cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 μg/mL penicillin and streptomycin mixture. Cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were regularly checked for the presence of mycoplasma via PCR. For ER stress assays, cells were plated in 10 cm plates overnight and subsequently treated for the listed amount of time with 10 μg/mL of tunicamycin dissolved in DMSO (Tocris Biosciences, Cat #35-161-0) before harvesting.

Co-immunoprecipitation assays

A549 cells were lysed with RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat #R0278) containing protease inhibitor (PierceTM Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Mini Tablets, EDTA-free, ThermoFisher, Cat #A32961) for 15 min on ice and sonicated at 20% for 30 s on ice. Cell debris was spun down at 16,100 rcf (4 °C, 15 min), and protein quantification was performed using the DCTM Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, Ca #5000112). Cell lysates were pre-cleared using PierceTM Protein A Magnetic beads (ThermoFisher, Cat #88846) for 1 h at 4 °C, and the beads were removed using a magnetic rack. 200 μg of cell lysate was incubated with 3 μL of IRE-1 antibody (Cell Signaling, 14C10, Cat #3294) overnight at 4 °C. 20 μL of Protein A Magnetic beads were added to the mixture for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rocking. The immunoprecipitated proteins were isolated from the cell lysate mixture using a magnetic rack and isolated beads were washed three times with the cell lysis buffer. The bound proteins were released from the beads by adding SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. The membranes were probed using the antibodies listed in Supplementary Table 3 and imaged as described above (see Immunoblotting). The tunicamycin treatment and immunoprecipitation assay was performed three separate times and the bands were quantified using the online Image Lab software from Bio-Rad (v 6.1.0).

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical analysis was done in Graphpad Prism (v10.4.0) and described in the figure legend, with the exception of RNA-sequencing analysis which was performed using Rstudio as described previously30. For super plots, the average of each biological replicate (n = 3) was used for analysis. Error bars represent standard deviation unless otherwise stated in the figure legend. Sample sizes were determined by standards for the C. elegans field as described above. Experimenters were blinded during assessment and analysis. No data were excluded from analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive under accession code CRA031491. The images of C. elegans used for analysis have been deposited in Zenodo (PHX4377 Tm and Tg: [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17391224]; PHX4415 Tm and Tg: [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17392620]; PHX4377 and PHX4415 Aging: [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17391837]; Body size images: [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17392925]. The Cell Profiler pipeline used for image analysis is available on Github [https://github.com/urbanni/BiP-Orthologs.git]. The florescence intensity, body size, development, egg laying, and western quantification data as well as survival/paralysis data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The semi-automated Cell Profiler pipeline is available online on Github [https://github.com/urbanni/BiP-Orthologs.git].

References

Zhang, J. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 292–298 (2003).

Sémon, M. & Wolfe, K. H. Consequences of genome duplication. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17, 505–512 (2007).

Fenech, E. J., Ben-Dor, S. & Schuldiner, M. Double the fun, double the trouble: paralogs and homologs functioning in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 89, 637–666 (2020).

Ihmels, J., Collins, S. R., Schuldiner, M., Krogan, N. J. & Weissman, J. S. Backup without redundancy: genetic interactions reveal the cost of duplicate gene loss. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 86 (2007).

Plata, G. & Vitkup, D. Genetic robustness and functional evolution of gene duplicates. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 2405–2414 (2014).

Hu, C. et al. Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm 3, e161 (2022).

Liu, P. et al. Targeting extracellular heat shock protein 70 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced heart failure through resolution of toll-like receptor 2-mediated myocardial inflammation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012338 (2019).

Kluger, H. M. et al. Using a xenograft model of human breast cancer metastasis to find genes associated with clinically aggressive disease. Cancer Res 65, 5578–5587 (2005).

Gao, G. et al. The prognostic significance of Hsp70 in patients with colorectal cancer patients: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. BioMed. Res. Int. 2021, 5526327 (2021).

Guo, D. et al. Suppression of HSP70 inhibits the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia via TAK1/Egr-1. Biomed. Pharmacother. 119, 109399 (2019).

Dou, F. et al. Chaperones increase association of tau protein with microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 721–726 (2003).

Witt, S. N. Hsp70 molecular chaperones and Parkinson’s disease. Biopolymers 93, 218–228 (2010).

Rebeaud, M. E., Mallik, S., Goloubinoff, P. & Tawfik, D. S. On the evolution of chaperones and cochaperones and the expansion of proteomes across the Tree of Life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2020885118 (2021).

Yu, E. M. et al. The complex evolution of the metazoan HSP70 gene family. Sci. Rep. 11, 17794 (2021).

Hasnain, P. & Kaneko, G. Phylogenetic annotation of Caenorhabditis elegans heat shock protein 70 genes. MicroPublication Biol. 2022, https://doi.org/10.17912/micropub.biology.000633 (2022).

Radons, J. The human HSP70 family of chaperones: where do we stand?. Cell Stress Chaperones 21, 379–404 (2016).

Chen, X., Shi, C., He, M., Xiong, S. & Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 352 (2023).

Raghunath, A., Panneerselvam, L., Sundarraj, K. & Perumal, E. Heat Shock Proteins and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. In Heat Shock Proteins and Stress Vol 15. Heat Shock Proteins. (eds Asea, A.A.A., Kaur, P.) 39–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90725-3_3 (Springer International Publishing, 2018).

Loi, M., Fregno, I., Guerra, C. & Molinari, M. Eat it right: ER-phagy and recovER-phagy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 46, 699–706 (2018).

Hetz, C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 89–102 (2012).

Su, S. et al. Sec62 promotes gastric cancer metastasis through mediating UPR-induced autophagy activation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 79, 133 (2022).

Pobre, K. F. R., Poet, G. J. & Hendershot, L. M. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone BiP is a master regulator of ER functions: getting by with a little help from ERdj friends. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 2098–2108 (2019).

Pincus, D. et al. BiP binding to the ER-stress sensor Ire1 tunes the homeostatic behavior of the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000415 (2010).

Kopp, M. C., Larburu, N., Durairaj, V., Adams, C. J. & Ali, M. M. U. UPR proteins IRE1 and PERK switch BiP from chaperone to ER stress sensor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 26, 1053–1062 (2019).

Chipurupalli, S. et al. Cancer cells adapt FAM134B/BiP mediated ER-phagy to survive hypoxic stress. Cell Death Dis. 13, 357 (2022).

Lacy, S. M. et al. FICD (FIC Domain Protein Adenylyl Transferase) Deficiency Protects Mice From Hypertrophy‐Induced Heart Failure and Promotes BiP (Binding Immunoglobulin Protein) ‐Mediated Activation of the Unfolded Protein Response and Endoplasmic Reticulum‐Selective Autophagy in Cardiomyocytes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 14, e040192 (2025).

Snutch, T. P., Heschl, M. F. P. & Baillie, D. L. The Caenorhabditis elegans hsp70 gene family: a molecular genetic characterization. Gene 64, 241–255 (1988).

Kapulkin, W. J., Hiester, B. G. & Link, C. D. Compensatory regulation among ER chaperones in C. elegans. FEBS Lett. 579, 3063–3068 (2005).

Zha, J., Ying, M., Alexander-Floyd, J. & Gidalevitz, T. HSP-4/BiP expression in secretory cells is regulated by a developmental program and not by the unfolded protein response. PLOS Biol. 17, e3000196 (2019).

Van Pelt, K. M. & Truttmann, M. C. Loss of FIC-1-mediated AMPylation activates the UPRER and upregulates cytosolic HSP70 chaperones to suppress polyglutamine toxicity. PLoS Genet. 21, e1011723 (2025).

Truttmann MC, Pincus D, Ploegh HL. Chaperone AMPylation modulates aggregation and toxicity of neurodegenerative disease-associated polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801989115 (2018).

Sasagawa, Y., Yamanaka, K. & Ogura, T. ER E3 ubiquitin ligase HRD-1 and its specific partner chaperone BiP play important roles in ERAD and developmental growth in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Cells 12, 1063–1073 (2007).

Tabara, H., Hill, R. J., Mello, C. C., Priess, J. R. & Kohara, Y. pos-1 encodes a cytoplasmic zinc-finger protein essential for germline specification in C. elegans. Dev. Camb. Engl. 126, 1–11 (1999).

Calfon, M. et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415, 92–96 (2002).

Gao, S. M. et al. Aging atlas reveals cell-type-specific effects of pro-longevity strategies. Nat. Aging 4, 998–1013 (2024).

Kaletsky, R. et al. Transcriptome analysis of adult Caenorhabditis elegans cells reveals tissue-specific gene and isoform expression. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007559 (2018).

Shen, J., Snapp, E. L., Lippincott-Schwartz, J. & Prywes, R. Stable binding of ATF6 to BiP in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 921–932 (2005).

Shen, X. et al. Complementary signaling pathways regulate the unfolded protein response and are required for C. elegans development. Cell 107, 893–903 (2001).

Perez, M. F. & Lehner, B. Vitellogenin—yolk gene function and regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Physiol. 10, 1067 (2019).

Topisirovic, I., Svitkin, Y. V., Sonenberg, N. & Shatkin, A. J. Cap and cap-binding proteins in the control of gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2, 277–298 (2011).

Zhai, C. et al. Fusion and expansion of vitellogenin vesicles during Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal senescence. Aging Cell 21, e13719 (2022).

Morita, K. A Caenorhabditis elegans TGF-beta, DBL-1, controls the expression of LON-1, a PR-related protein, that regulates polyploidization and body length. EMBO J. 21, 1063–1073 (2002).

Calixto, A., Chelur, D., Topalidou, I., Chen, X. & Chalfie, M. Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nat. Methods 7, 554–559 (2010).

Watts, J. S. et al. New Strains for Tissue-Specific RNAi Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 10, 4167–4176 (2020).

Zou, L. et al. Construction of a germline-specific RNAi tool in C. elegans. Sci. Rep. 9, 2354 (2019).

Yigit, E. et al. Analysis of the C. elegans argonaute family reveals that distinct argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell 127, 747–757 (2006).

Avery, L. The genetics of feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 133, 897–917 (1993).

Leiser, S. F. et al. Cell nonautonomous activation of flavin-containing monooxygenase promotes longevity and health span. Science 350, 1375–1378 (2015).

Kenyon, C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A. & Tabtiang, R. A. C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366, 461–464 (1993).

McColl, G. et al. Utility of an improved model of amyloid-beta (Aβ1-42) toxicity in Caenorhabditis elegans for drug screening for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 7, 57 (2012).

Lin, H. et al. Autophagy regulation influences β-amyloid toxicity in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Front Aging Neurosci. 14, 885145 (2022).

Gidalevitz, T., Ben-Zvi, A., Ho, K. H., Brignull, H. R. & Morimoto, R. I. Progressive disruption of cellular protein folding in models of polyglutamine diseases. Science 311, 1471–1474 (2006).

Anderson, P. & Brenner, S. A selection for myosin heavy chain mutants in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 81, 4470–4474 (1984).

Barral, J. M., Bauer, C. C., Ortiz, I. & Epstein, H. F. Unc-45 mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans implicate a CRO1/She4p-like domain in myosin assembly. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1215–1225 (1998).

Ash, P. E. A. et al. Neurotoxic effects of TDP-43 overexpression in C. elegans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 3206–3218 (2010).

Yang, Z. & Klionsky, D. J. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr. Top. Microbiol Immunol. 335, 1–32 (2009).

Wang, L., Ye, X. & Zhao, T. The physiological roles of autophagy in the mammalian life cycle. Biol. Rev. 94, 503–516 (2019).