Abstract

The morphology of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), characterized by central sheets and peripheral tubules, is controlled by membrane-shaping proteins. However, the role of lipids in ER morphogenesis remains elusive, despite the ER being the major site for lipid synthesis. Here, by examining the role of eighteen phosphatidic acid (PA)-generating enzymes in ER morphology, we identify lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase 2 (AGPAT2) as a critical factor in mouse and human cells. AGPAT2 produces PA in the glycerophospholipid/triacylglycerol biosynthesis pathway, and its mutations cause congenital generalized lipodystrophy. We find that AGPAT2-generated PA drives ER tubulation through gene knockout, 3D structural analysis by FIB-SEM, super-resolution microscopy, lipidomics, AlphaFold, and in vitro reconstitutions of ER tubulation and AGPAT2 activity. AGPAT2 interacts with and supplies PA to the PA-binding, dynamin-related GTPase, DRP1, which subsequently tubulates the ER in a manner independent of GTP hydrolysis and oligomerization, distinct from its function in mitochondrial division. Consistently, the reduction of PA levels by ectopic expression of a PA phosphatase, LIPIN1, transforms ER tubules into sheets. Our results reveal an unforeseen interplay between lipid biosynthesis and membrane organization in the ER.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ER establishes a unique morphology with sheets and tubules and plays crucial roles in cellular functions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. ER sheets, contiguous to the nuclear membrane, create rough ER which is essential for protein translation and post-translational modification. In contrast, ER tubules, which are involved in lipid synthesis and signaling, form dynamic platforms, that interact with other organelles such as the plasma membrane, mitochondria, endosomes, lipid droplets, and P-bodies10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Previous studies have elucidated mechanisms that contribute to ER morphology through multiple ER-resident integral membrane proteins. These include reticulons and DP1/Yop1p, responsible for tubule formation; atlastin, which fuses ER tubules; lunapark/Lnp1p, crucial for the formation of three-way junctions in ER tubules; and Climp-63, which is involved in the formation of ER sheets19,20,21,22. However, in contrast to these protein factors, the role of lipids in ER morphology is unknown.

Dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) is a soluble protein and key member of the dynamin superfamily, known for severing the membranes of mitochondria and peroxisomes23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Beyond these organelles, DRP1 also localizes to the ER, where it contributes to the tubulation of the ER membrane31,32. The mechanism through which DRP1 induces ER tubulation differs significantly from its role in mitochondrial division. Mitochondrial division is governed by the oligomerization and GTP hydrolysis activities of DRP1. In contrast, ER tubulation does not depend on these activities31. Instead, an 18-amino-acid region in the variable domain (D-octadecapeptide) drives ER tubulation31. Therefore, DRP1 utilizes a unique mechanism for membrane deformation and ER tubulation. Notably, both DRP131 and D-octadecapeptide (Supplementary Fig. 1) preferentially bind to phosphatidic acid (PA). However, whether PA is required for ER morphogenesis remains unknown.

In this study, we performed a gene knockdown screen targeting enzymes responsible for PA production at the ER. Our data revealed that a specific lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase, AGPAT2, cooperates with DRP1 to regulate ER morphology.

Results

AGPAT2 is required for ER morphogenesis

PA is produced through three major biosynthetic pathways: two phospholipases D (PLDs) generate PA from phosphatidylcholine (PC), ten diacylglycerol kinases (DGKs) create PA from diacylglycerol (DAG), and six lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferases (AGPATs) produce PA by adding a fatty acid to lysoPA from acyl-CoA (Fig. 1a)33. To test whether any of these enzymes are required for ER morphogenesis, we individually knocked down all 18 PA-producing enzymes in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) using esiRNAs and siRNAs (Supplementary Fig. 2a). As a negative control, esiRNA targeting RLuc was used. ER morphology was assessed by laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy of MEFs expressing an ER marker, GFP-SEC61β, using anti-GFP antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We previously reported that ER tubules constitute ~50% of the ER in wild-type (WT) MEFs31. In the initial screen, we set a threshold of approximately half the WT level as the criterion for a positive hit. This degree of reduction can be readily identified by visual inspection without quantification. Among the 18 enzymes tested, only knockdown of a lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase beta, AGPAT2) met this criterion in two experimental replicates (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

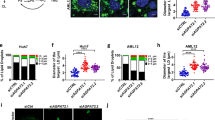

a Biosynthetic pathways of PA in the ER. b MEFs expressing an ER marker (GFP-SEC61β) were transduced with lentiviruses carrying scramble, AGPAT1, or AGPAT2 shRNAs. Cells were subjected to laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-GFP antibodies. Boxed areas are enlarged. Cells are outlined by a dotted line. c Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments; 10 cells were analyzed in each experiment). d, e Knockdown of AGPAT1 (d) and AGPAT2 (e) was confirmed by qPCR. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). f AGPAT2-KO MEFs were generated by CRISPR. The KO cells were rescued by ectopically expressing HA-tagged AGPAT2 via lentiviral transduction. ER morphology was analyzed using GFP-SEC61β. g Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments; 10 cells were analyzed in each experiment). h Human U2OS cells were treated with control Rluc or AGPAT2 esiRNAs. i Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). j AGPAT2 knockdown was confirmed by qPCR. Mean ± SD n = 3 experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (c, g) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (d, e, i, j). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The role of AGPAT2 in ER morphology was further confirmed by shRNA knockdown (Fig. 1b, c, e), CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout (KO) in MEFs (Fig. 1f, g; and Supplementary Fig. 3), and esiRNA-mediated knockdown in human U2OS cells (Fig. 1h–j). Altered ER morphology in AGPAT2-KO cells was rescued by expressing AGPAT2-HA, demonstrating its specificity (Fig. 1f, g). To analyze the 3D ultrastructure of the peripheral ER, we performed focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM)34 on WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs, along with DRP1-KO MEFs, in which ER tubulation is decreased31 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Consistent with the data from laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, 3D reconstruction of the ER structure demonstrated ER sheets at the cell periphery in AGPAT2-KO and DRP1-KO cells, in contrast to WT cells, which contained a network of tubules of the ER (Fig. 2a, b, and Supplementary Movies 1–3).

a The dimensions of the imaged blocks (width × height × thickness) were 8.1 × 6.8 × 0.4 µm for WT cells, 8.0 × 7.0 × 0.5 µm for DRP1-KO cells, and 8.4 × 6.4 × 0.5 µm for AGPAT2-KO cells. Representative fields of view for each sample are shown. b Aligned and reconstituted 3D images are presented. Boxed areas are enlarged.

AGPAT1 is another lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase closely related to AGPAT233. In the knockdown screen, AGPAT1 esiRNA did not affect ER morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2b). This result was confirmed using shRNA (Fig. 1b–d). In addition, further knockdown of AGPAT1 did not affect ER morphology in AGPAT2-KO MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Moreover, the altered ER morphology in AGPAT2-KO MEFs was not rescued by the expression of AGPAT1 (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). Collectively, these data show that AGPAT1 is not involved in the regulation of ER morphology.

Since ER stress affects ER morphology35, we assessed ER stress by examining markers such as BIP and CHOP expression levels, as well as phosphorylation of eIF2α. The results show that ER stress is not elevated in AGPAT2-KO cells compared to WT cells (Fig. 3). As a positive control, we treated cells with tunicamycin and confirmed robust activation of the ER stress response (Fig. 3).

a WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against ER stress markers, including BiP, eIF2α, phospho-eIF2α, and CHOP, along with tubulin as a loading control. As a positive control, WT cells were treated with 10 µg/ml tunicamycin for 24 h to induce ER stress. b Quantification of band intensity. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The topology of AGPAT2

AGPAT2 is an integral membrane protein with a single predicted transmembrane domain in the ER based on TmAlphaFold36,37 (Fig. 4a). To determine its topology, we expressed C-terminally FLAG-tagged AGPAT2 in MEFs (Fig. 4b). As a control, we co-expressed SEC61β, which is fused to HA at its C-terminus facing the ER lumen (Fig. 4b). We then performed laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies to FLAG and HA under different membrane permeabilization conditions using saponin (which selectively permeabilizes the plasma membrane) or Triton X-100 (which permeabilizes both the plasma and ER membranes). In the absence of detergents, we observed essentially no staining of AGPAT2-FLAG or SEC61β-HA (Fig. 4b–d). When the plasma membrane was permeabilized with saponin, we detected AGPAT2-FLAG but not SEC61β-HA (Fig. 4b–d). Conversely, when all membranes were permeabilized with Triton X-100, we detected both AGPAT2-FLAG and SEC61β-HA (Fig. 4b–d). These data suggest that the C-terminus of AGPAT2 faces the cytosol (Fig. 4e).

a A structure of ER membrane-embedded AGPAT2 predicted by TmAlphaFold is presented. b WT MEFs expressing AGPAT2-FLAG and SEC61β-HA were subjected to laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-FLAG and anti-HA antibodies. The selective permeabilization of the plasma membrane by saponin (not affecting the ER membrane) versus the complete membrane permeabilization by Triton X-100 was used to discern protein localization. c Intensity of AGPAT2-FLAG and SEC61β-HA was quantified and normalized to the average of that in cells treated with Triton X-100. Mean ± SD (n = 10 cells). d Summary of the data, illustrating the differential accessibility of AGPAT2-FLAG and SEC61β-HA under selective versus complete membrane permeabilization conditions. e A model for AGPAT2 topology. f–i WT MEFs expressing mCherry-SEC61β were transduced with lentiviruses carrying AGPAT2-FLAG (f) or RTN4A-GFP (h) and subjected to laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies to FLAG and mCherry (f) and GFP and mCherry (h). Intensity of SEC61β, AGPAT2, and RTN4A was quantified (g, i). Mean ± SD (n = 30 cells). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (c) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (g, i). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

AGPAT2 is preferentially localized at ER tubules

ER-shaping proteins show preferential localization to specific ER subdomains. For instance, the ER tubulating protein, reticulon 4 A (RTN4A), is enriched in ER tubules, while the ER sheet-forming protein Climp-63 is predominantly found in sheets19. To investigate the intra-ER localization of AGPAT2, we compared the localization of AGPAT2-FLAG with that of RTN4A-GFP in cells expressing mCherry-SEC61β, which is uniformly distributed in the ER membrane (Fig. 4f–i). We found that AGPAT2-FLAG was preferentially enriched in ER tubules (Fig. 4f, g), to a degree similar to RTN4A-GFP (Fig. 4h, i). This localization, together with the knockdown and knockout phenotypes showing decreased ER tubules, suggests that AGPAT2 plays a significant role in ER tubulation.

AGPAT2 functions in ER tubulation together with DRP1

Two ER tubulating proteins, DRP1 and the reticulon RTN4A, function through distinct mechanisms31. RTN4A induces ER tubulation by oligomerizing and inserting wedges into the ER membrane22, while DRP1 facilitates ER tubulation by inserting D-octadecapeptide in the variable domain31. To determine whether AGPAT2 works together with RTN4A or DRP1 in ER morphogenesis, we ectopically expressed AGPAT2-FLAG in WT, RTN4A-KO, and DRP1-KO cells (Fig. 5a, b). Complementing the data from AGPAT2 depletion and localization studies, the ectopic expression of AGPAT2 increased the levels of ER tubules in WT cells (Fig. 5a, b; WT). Similarly, in RTN4-KO cells, the overexpression of AGPAT2 led to increased ER tubules, indicating that RTN4A is not required for AGPAT2-induced ER tubulation (Fig. 5a, b; RTN4A-KO). In contrast, the overexpression of AGPAT2 in DRP1-KO cells did not induce ER tubulation (Fig. 5a, b; DRP1-KO). Therefore, AGPAT2’s ability to mediate ER tubulation depends on DRP1. Taken together, these data suggest that AGPAT2 and DRP1 collaboratively contribute to ER tubule formation within the same pathway. Further supporting this notion, DRP1 overexpression increased ER tubules in RTN4A-KO cells but not in AGPAT2-KO cells (Fig. 5c, d), and RTN4A overexpression induced ER tubulation in AGPAT2-KO cells (Fig. 5e, f).

a WT, RTN4A-KO, and DRP1-KO cells were transfected with AGPAT2-FLAG. The ER was visualized using mCherry-SEC61β. b Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). c AGPAT2-KO and RTN4A-KO MEFs were transfected with DRP1. The ER was visualized using GFP-SEC61β. d Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). e WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs were transfected with RTN4A-GFP. The ER was visualized using mCherry-SEC61β. f Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (b, f) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (d). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To test whether the loss of AGPAT2 affects the expression levels of reticulons, we analyzed their protein abundance by Western blotting. Among the four reticulons in mice, RTN3 and RTN4 are highly expressed in MEFs, whereas RTN1 and RTN2 are expressed at very low levels or are undetectable (www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/home). Therefore, we examined RTN3A and RTN4A levels in WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs. We found that RTN3A levels remained unchanged between genotypes, while RTN4A levels were modestly increased in AGPAT2-KO MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 6). We speculate that this upregulation may represent a compensatory response to reduced ER tubules in AGPAT2-KO cells. We also examined the level of the sheet-forming protein Climp-63 and found it to be reduced in AGPAT2-KO MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 6), which may similarly reflect a compensatory mechanism.

In vitro reconstitution of AGPAT2- and DRP1-mediated ER tubulation

To further investigate the functional relationship between AGPAT2 and DRP1, we developed an in vitro reconstitution of ER tubulation using purified ER and recombinant DRP1 (Fig. 6). We isolated ER from WT, DRP1-KO, and AGPAT2-KO MEFs and incubated them with DRP1. To distinguish DRP1’s function in mitochondrial division, GTP was omitted from the reaction. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that purified WT ER contains both sheets and tubules and the addition of DRP1 did not alter these structures (Fig. 6a, b). In contrast, isolated DRP1-KO ER predominantly displayed sheet structures without tubules, and incubation with DRP1 induced tubulation of the membrane (Fig. 6a, b). As a negative control, recombinant GFP did not tubulate the ER (Fig. 6c). The intracellular concentration of DRP1 has been estimated to be 0.5 µM38. DRP1 significantly induced ER tubulation below this concentration (0.3 µM) in our assay (Fig. 6d, e). Similar to DRP1-KO ER, AGPAT2-KO ER primarily exhibited sheet morphology. However, in sharp contrast to DRP1-KO ER, DRP1 was unable to induce tubulation of AGPAT2-KO ER membranes (Fig. 6a, b). These data indicate that AGPAT2 is essential for DRP1 to tubulate the ER membrane in vitro.

a The ER was purified from WT, DRP1-KO, and AGPAT2-KO MEFs and incubated with 1 µM recombinant DRP1 in the absence of GTP for 3 h. The morphology of the ER membrane was analyzed by transmission electron microscopy with negative staining. b The length of ER tubules was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 15 tubules). c GFP does not tubulates the ER in vitro. The ER isolated from Drp1-KO MEFs was incubated with 1 µM GFP for 3 h. d DRP1 tubulates the ER membrane in a dose-dependent manner in vitro. The ER isolated from Drp1-KO MEFs was incubated with varying amounts of DRP1 in the absence of GTP for 3 h. e The length of ER tubules was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 15 tubules). f ER membranes purified from DRP1-KO MEFs were incubated with 1 µM recombinant WT DRP1 or DRP1(K38A, G350D) in the absence of GTP for 3 h. g The length of ER tubules was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 10 tubules). (h) Tubule widths of purified ER (WT) and DRP1-induced tubules from DRP1-KO ER (WT and mutant) were quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 15 tubules). i ER membranes purified from WT MEFs were incubated with the indicated antibodies for 3 h. j The length of ER tubules was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 10 tubules). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (b, e, g, h, j). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We previously reported that DRP1’s GTPase activity and oligomerization are not required for ER tubulation in cells31. To test whether these activities are also dispensable in vitro, we used recombinant DRP1 harboring the K38A and G350D mutations, which impair GTP hydrolysis and oligomerization, respectively31. The mutant protein tubulated isolated DRP1-KO ER as effectively as the WT protein (Fig. 6f, g). It has been shown that tubules generated from liposomes and purified DRP1 measure ~60 nm in diameter and become constricted to ~40 nm upon GTP hydrolysis, a change proposed to represent a step in mitochondrial division39. Importantly, the width of purified ER tubules was ~30 nm, narrower than these reported values (Fig. 6h). Moreover, ER tubules induced by both WT and mutant DRP1 were also ~30 nm (Fig. 6h). These findings indicate that neither GTP hydrolysis nor oligomerization is required for DRP1-mediated ER tubulation in vitro, distinguishing this process from mitochondrial division.

To determine whether PA is responsible for the defect in DRP1-mediated tubulation of AGPAT2-KO ER, we added soluble 8:0 PA and DRP1 to in vitro reactions using AGPAT2-KO/DRP1-depleted ER. PA restored ER tubulation in a dose-dependent manner, but only when both PA and DRP1 were present (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). In contrast, no such structures were observed in a mixture of DRP1 and PA alone, without ER, as a negative control (Supplementary Fig. 7c). These findings indicate that AGPAT2 is required to supply PA for DRP1-mediated ER membrane tubulation. It remains possible that 8:0 PA inserted into the membrane and stimulated DRP1-dependent tubulation, or alternatively, that PA activated DRP1 as a soluble lipid without membrane integration.

To ask if ER tubules in WT ER membranes are generated by endogenous DRP1, we incubated WT ER with antibodies against DRP1 or, as a negative control, TOM20. Incubation with the DRP1 antibody—but not the TOM20 antibody—led to the loss of ER tubules (Fig. 6i, j). Therefore, endogenous DRP1 is required to maintain ER tubular structures. We speculate that the antibody-mediated inhibition does not occur through direct interference with membrane-embedded regions of DRP1, but rather through binding to other domains, thereby altering its conformation to one less favorable for membrane association or deformation.

The catalytic activity of AGPAT2 is critical for ER tubulation

To determine whether the enzymatic activity of AGPAT2 is required for maintaining ER morphology, we introduced mutations in the conserved catalytic motifs of AGPAT2-HA and expressed the mutants in AGPAT2-KO MEFs33,40,41 (Fig. 7a–c). While WT AGPAT2 successfully rescued the ER morphology in the KO cells, all the mutants failed to do so (Fig. 7a–c). Hence, the PA-producing activity of AGPAT2 is critical for maintaining proper ER morphology. To assess the role of AGPAT2 in PA production, we developed a biochemical assay to measure the activity of PA production from lysoPA in vitro by incubating purified ER membranes with two substrates of AGPAT2: fluorescent lysoPA-TopFlour and acyl-CoA (Fig. 7d). We then analyzed the production of PA-TopFlour using thin-layer chromatography. Our results indicated that PA production is greatly decreased in AGPAT2-KO ER membranes compared to WT ER membranes, underscoring the significance of AGPAT2 in PA production within the ER (Fig. 7e, f).

a A structure of ER membrane-embedded AGPAT2 predicted by TmAlphaFold is presented. Mutations introduced in the three catalytic motifs of AGPAT2 are shown in red. b AGPAT2-KO MEFs expressing the ER marker (GFP-SEC61β) were transduced with lentiviruses carrying WT and mutant AGPAT2-HA. Cells were subjected to laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-GFP and anti-HA antibodies. Boxed areas are enlarged. Cells are outlined by a dotted line. c Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). d We developed an in vitro assay to measure lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase activity. Fluorescently labeled lysophosphatidic acid (LPA-TopFluor) and acyl-coenzyme A (Acyl-CoA) were incubated with ER purified from WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs. e PA-TopFluor was detected using thin layer chromatography followed by fluorescence imaging. f PA-TopFluor amounts were quantified and normalized relative to those made in WT ER. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). g AGPAT2 makes PA from LPA, while LIPIN1 generates diacylglycerol from PA in the glycerophospholipid/triacylglycerol biosynthesis pathway. h AGPAT2-KO MEFs expressing mCherry-SEC61β were transduced with lentiviruses carrying AGPAT2-HA along with WT LIPIN1 and enzymatically-inactive LIPIN1 (D712A). Cells were subjected to laser confocal immunofluorescence microscopy with antibodies to mCherry, HA, and FLAG. Boxed areas are enlarged. Cells are outlined by a dotted line. i Quantification of ER morphology. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (c, i) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (f). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further investigate whether PA is critical for ER tubulation, we ectopically expressed WT HA-LIPIN1 in AGPAT2-KO MEFs that were also expressing AGPAT2-FLAG. LIPIN1 catalyzes the dephosphorylation of PA to DAG, thus its overexpression is expected to downregulate PA-mediated functions42 (Fig. 7g). Our results showed that the expression of WT HA-LIPIN1 significantly reduced the number of ER tubules (Fig. 7h, i; HA-LIPIN1). In contrast, a catalytically-inactive mutant of LIPIN1-HA did not influence the ER tubules42 (Fig. 7h, i; D712A). Thus, these data indicate that PA, produced by AGPAT2, plays a pivotal role in maintaining ER morphology.

We confirmed that LIPIN1 overexpression decreases PA levels using lipid mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In contrast, DAG levels remained unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 8a). One possibility is that although LIPIN1 overexpression increases DAG production, the DAG is rapidly converted into downstream products such as triacylglycerols or other phospholipids. Alternatively, because DAG is 30–40 times more abundant than PA (Supplementary Fig. 8a), the conversion of PA to DAG may not be detectable upon LIPIN1 overexpression.

AGPAT2 and DRP1 interact

PA is predominantly synthesized in the ER and serves as a major precursor for the biosynthesis of phospholipids and triacylglycerol43,44,45,46,47. Remarkably, PA is dynamic, short-lived, and stealthy in nature—large amounts are produced and then rapidly transformed into other lipids or transported to mitochondria43,44,45,48. Consistent with the exceptionally transient nature of PA, only small amounts are detected in the ER by mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 8b), and it is undetectable by the PA biosensor PASS at steady state45,49,50,51,52 (Supplementary Fig. 9). To address how this stealthy lipid is supplied to ER morphogenesis, we tested whether AGPAT2 interacts with DRP1 through co-immunoprecipitation. We found that AGPAT2-FLAG co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous DRP1 (Fig. 8a, b). Furthermore, the co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous AGPAT2 and DRP1 was also confirmed in human HEK293T cells without ectopic expression (Fig. 8c, d). In contrast, AGPAT1, a closely related enzyme to AGPAT2, showed less co-immunoprecipitation with DRP1 (Fig. 8e, f). These results suggest that AGPAT2 is in close proximity to DRP1.

a HEK293T cells were transfected with AGPAT2-FLAG and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies. Whole cell lysates and immunoprecipitates (IP) were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. b Quantification of DRP1 signal intensity in the IP fraction. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). c Immunoprecipitation of HEK293T cells with anti-DRP1 antibodies. d Quantification of AGPAT2 signal intensity in the IP fraction. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). e Immunoprecipitation of HEK293T cells expressing AGPAT2-FLAG or AGPAT1-FLAG with anti-FLAG antibodies. Western blotting of lysates and immunoprecipitates. f Quantification of DRP1 signal intensity in the IP fraction. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). g–j Airyscan superresolution microscopy of WT MEFs (g, h) and AGPAT2-KO MEFs (i, j), both of which expressed mCherry-SEC61β, with antibodies to mCherry and DRP1. Box regions are enlarged. g, h 3D reconstitution of serial Z-stack images showing ER (red) and DRP1 (green) in the box 3. k The ER and mitochondrial fractions were obtained from WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs using differential centrifugation. Each fraction was analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies to DRP1 along with marker proteins for the ER (CLIMP63), cytosol (ACTIN), and mitochondria (TIM23). l Band intensity of DRP1 in the ER fraction was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed Student’s t-test (b, d, f, l). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The interaction with AGPAT2 and its generated PA does not seem to be required for the ER localization of DRP1. We examined the localization of DRP1 in WT and AGPAT2-KO MEFs using immunofluorescence super-resolution Airyscan microscopy with anti-DRP1 antibodies. In WT MEFs, 3D reconstruction of images revealed that DRP1 is associated with the ER marked by mCherry-SEC61β, displaying a snake-like pattern (Fig. 8g, h, and Supplementary Movie 4). In AGPAT2-KO cells, DRP1 also exhibited an association with the ER (Fig. 8i, j, Supplementary Movie 5). Furthermore, biochemical fractionation confirmed indistinguishable co-fractionation of DRP1 with the ER in both WT and AGPAT2-KO cells (Fig. 8k, l). These data suggest that AGPAT2 and PA are involved in the functions of DRP1 but not its localization.

PA modulates the AGPAT2-DRP1 interaction

To further examine the interaction of AGPAT2 with DRP1, we expressed three catalytically inactive mutants of AGPAT2-FLAG in AGPAT2-KO cells and performed co-immunoprecipitation with endogenous DRP1. All three mutants co-immunoprecipitated with DRP1 much less efficiently than WT AGPAT2-FLAG did (Fig. 9a, b). These data suggest that either the mutations affect the conformation of AGPAT2, disrupting its co-immunoprecipitation with DRP1, or that AGPAT2’s enzymatic activity (i.e., the production of PA) is important for the AGPAT2-DRP1 co-immunoprecipitation. To test these two models, we expressed the PA phosphatase LIPIN1 in AGPAT2-KO cells carrying WT AGPAT2-FLAG. Results showed that WT LIPIN1, but not the enzymatically inactive mutant LIPIN1 (D172A), decreased co-immunoprecipitation between WT AGPAT2-FLAG and DRP1 (Fig. 9c, d). These data suggest that AGPAT2-produced PA plays an important role in the interaction of AGPAT2 and DRP1.

a AGPAT2-KO HEK293T cells expressing different AGPAT2-FLAG constructs were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibodies. b Band intensity of DRP1 in the IP fraction was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). c Immunoprecipitation of HEK293T cells expressing WT HA-LIPIN1 or enzymatically-inactive HA-LIPIN1 (D712A). d Band intensity of DRP1 was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). e GFP-fused DRP1 constructs used in co-immunoprecipitation assays are shown. f DRP1-KO HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated AGPAT2 and GFP-DRP1 constructs. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using GFP-Trap beads. g Band intensity of AGPAT2-FLAG in the IP fraction was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). h Interaction of DRP1 and AGPAT2 predicted by AlphaFold 3 is shown. i, k DRP1-KO HEK293T cells expressing the indicated AGPAT2 and DRP1 domains were analyzed by immunoprecipitation using GFP-Trap beads. j, l Band intensity of AGPAT2-FLAG in the IP fraction was quantified. Mean ± SD (n = 3 experiments). m Model for the role of AGPAT2 in lipid biosynthesis and ER tubulation. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey (b, d, l) and two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Sidak (g, j). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To understand how PA affects the AGPAT2-DRP1 interaction, we first compared the co-immunoprecipitation of AGPAT2-FLAG with GFP fused to full-length DRP1 (GFP-FL) and DRP1 consisting of the GTPase and stalk domains, lacking the PA-binding variable domain53 (GFP-GS) (Fig. 9e–g). We used DRP1-KO HEK293T cells to avoid the contribution of endogenous DRP1. WT AGPAT2 similarly co-immunoprecipitated with both GFP-FL and GFP-GS (Fig. 9f, g). Consistent with these data, AlphaFold3 suggests that AGPAT2 interacts with DRP1 near the junction of the GTPase and stalk domains53 (Fig. 9h). Distinct from GFP-FL, which showed reduced co-immunoprecipitation with the mutant AGPAT2 (H98A, D103N), GFP-GS lacking the variable domain did not show reduced co-immunoprecipitation with the mutant (Fig. 9f, g). These data suggest that the variable domain inhibits the interaction of DRP1 with AGPAT2 when AGPAT2 does not produce PA.

We hypothesize that the GTPase and/or stalk domains interact with AGPAT2 while the variable domain regulate such interactions. Indeed, GFP-GTPase domain (GFP-G) or GFP-stalk domain alone (GFP-S) co-immunoprecipitated with AGPAT2 (Fig. 9i, j). Further supporting the inhibitory role of the variable domain, both GFP-G and GFP-S co-immunoprecipitated similarly with WT and the mutant AGPAT2 (H98A, D103N) (Fig. 9i, j). In contrast, the variable domain does not co-immunoprecipitate with AGPAT2 (Fig. 9k, l). These data suggest that the variable domain promotes the association of DRP1 with AGPAT2 when AGPAT2 produces PA, creating a robust mechanism by which PA enhances both the DRP1–AGPAT2 interaction and ER tubulation.

Since the variable domain regulates DRP1 oligomerization54, we investigated whether oligomerization contributes to PA-mediated regulation of the DRP1–AGPAT2 interaction. We performed a co-immunoprecipitation assay using the oligomerization-defective G350D mutant and found that DRP1 (G350D) interacts more strongly with enzymatically inactive AGPAT2 (H98A, D103N) than WT DRP1 (Supplementary Fig. 10). These results suggest that inhibition involves DRP1 oligomerization. Due to the unstructured nature of the variable domain, it is poorly resolved in existing structural models of DRP1, and how this domain interacts with or influences the GTPase and stalk domains remains largely unknown55,56,57,58. Nonetheless, oligomerization may facilitate intermolecular interactions within DRP1 oligomers such that the variable domain physically hinders interaction with AGPAT2. Alternatively, oligomerization may induce conformational changes in the GTPase or stalk domains that enhance their interaction with AGPAT2 in the absence of PA.

Finally, the interaction between DRP1 and AGPAT2 raised the question of whether AGPAT2 is required for ER tubulation because its loss depletes the majority of PA in the ER, or because AGPAT2 supplies PA directly to DRP1, thereby stimulating DRP1-mediated ER tubulation without altering overall PA levels. To test these possibilities, we performed lipidomics on purified ER membranes using shotgun mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 8b)59,60,61. Our results revealed that the steady-state level of PA and other phospholipids, was comparable in ER purified from WT and AGPAT2-KO cells. These findings suggest that AGPAT2 does not regulate ER morphology by altering steady-state PA levels, but rather by supplying PA to DRP1 through their direct interaction.

Discussion

Protein factors have been identified and extensively studied for their roles in controlling the elaborate morphology of the ER19,20,21,22. In the current study, we uncover the roles of a lipid, PA, and its producing enzyme, AGPAT2, in ER morphogenesis. This discovery stems from a comprehensive set of approaches, including gene knockout, volume electron microscopy via FIB-SEM, super-resolution microscopy, lipidomics, molecular structural analysis using AlphaFold, and in vitro reconstitutions of ER tubulation and AGPAT2 activity.

Our data demonstrate that PA, generated by AGPAT2, drives the tubulation of the ER membrane both in cells and in vitro. The loss of AGPAT2 reduces ER tubules in cells, while its overexpression increases them. The enzymatic activity of AGPAT2 is essential for its role in ER tubulation. Consistent with this function, AGPAT2 is preferentially enriched in ER tubules. Our findings also indicate that PA collaborates with the dynamin-related GTPase DRP1 in ER tubulation: ER tubulation driven by AGPAT2 overexpression requires DRP1, and vice versa, in cells. Moreover, our in vitro ER tubulation assay shows that the activity of DRP1 in transforming ER sheets into tubules requires PA. DRP1 has been reported to form ER tubules through the D-octadecapeptide located within the unstructured loop of its variable domain, independently of its GTPase activity31. We show that PA binds to the D-octadecapeptide and facilitates its insertion into the ER membrane (Fig. 9m). The small head group of PA gives this phospholipid a cone shape. This unique shape can deform the membrane and increase its curvature. However, since ER tubulation depends on both PA and DRP1, the shape of PA alone is not sufficient to create the extreme curvature of ER tubules.

After synthesis in the ER membrane, PA is rapidly transported to mitochondria or converted to other lipids in the ER43,44,45,48. The interaction of AGPAT2 with DRP1 likely facilitates DRP1’s efficient capture of the remarkably transient phospholipid PA for ER tubulation. Our data suggest that this interaction is mediated by the GTPase and stalk domains of DRP1 and is promoted by PA. Therefore, PA plays dual roles in the AGPAT2-DRP1 interaction and in DRP1-mediated membrane tubulation in the morphogenesis of the ER.

AGPAT2 plays a vital role in the biosynthesis of glycerophospholipids and triacylglycerols33. Mutations in AGPAT2 in humans are associated with congenital generalized lipodystrophy, which is characterized by a profound loss of adipose tissue62. Hence, our study demonstrates a key function of AGPAT2 at the nexus of lipid metabolism and organelle morphology. This function involves collaboration with the biosynthetic enzyme LIPIN1 and the ER-shaping protein DRP1 (Fig. 9m).

Previous studies using the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have shown that ER membrane expansion into sheet structures can be induced by lipid synthesis or ER stress63,64,65,66,67,68. In our current study, we first tested the role of ER stress and found no induction of ER stress in AGPAT2-KO cells. Second, we performed lipidomic analysis and found similar levels of PA and other phospholipids in WT and AGPAT2-KO ER. Therefore, the increase in ER tubules is not simply due to PA depletion in AGPAT2-KO cells. Third, our in vitro assays distinguish between lipid biosynthesis and ER morphogenesis, as these assays do not involve lipid production.

Excellent studies have reported that purified DRP1 can oligomerize on liposomes containing various negatively charged phospholipids, with cardiolipin being the most potent stimulator39,69,70,71. These findings suggest that DRP1 can interact with different negatively charged phospholipids and tubulate synthetic membrane vesicles without the involvement of other proteins. GTP hydrolysis by DRP1 drives the constriction of these membrane tubules39, and this GTP-regulated membrane constriction likely underlies the function of DRP1 in mitochondrial division. In contrast, the role of DRP1 in ER tubulation does not appear to require its oligomerization or GTPase activity31 (Fig. 6f, g). Taken together, these results suggest that DRP1 may employ two distinct membrane deformation mechanisms: one for mitochondrial division and another for ER tubulation. We also note that the D-octadecapeptide in the variable domain of DRP1 preferentially interacts with saturated PA (Supplementary Fig. 1) and tubulates liposomes31. Saturated PA may promote this interaction through a mechanism involving phase separation. It will be critical to further dissect the biochemical properties of DRP1 in regulating these two different organelles. Another fundamental question is whether DRP1 directly tubulates ER membranes or instead regulates other ER tubulation proteins in cells. We look forward to future investigations to address these key questions in ER morphogenesis.

Methods

Cells

WT, AGPAT2-KO, DRP1-KO31, and RTN4A-KO31 MEFs were grown in IMDM medium (12440061, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% FBS. WT, AGPAT2-KO, and DRP1-KO HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM media (10-017-CV, Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS. U2OS cells (HTB-96, ATCC) were cultured in DMEM medium containing 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360-070, Gibco). KO cells were generated using the GeneArt CRISPR Nuclease Vector with OFP Reporter Kit (A21174, Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The target sequences for AGPAT2 (mouse: ACCGACCTTGGCGTAGAACC; human: AGGTACATGATGAGGCCCAC) and DRP1 (human: GCCTGTAGGTGATCAACCTA) were cloned into the vector and transfected into WT MEFs (for mouse AGPAT2) or HEK293T cells (for human AGPAT2 and DRP1). Based on the OFP fluorescent signal, transfected cells were sorted into 96-well plates as single cells at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Flow Cytometry and Immunology Core. The knockouts of AGPAT2 and DRP1 were screened and confirmed by DNA sequencing and/or Western blotting.

Plasmids and lentiviruses

Plasmids carrying GFP-SEC61β (15108) and RTN4A-GFP (61807) were obtained from Addgene. mCherry-SEC61β plasmids were constructed by replacing GFP with mCherry in the GFP-SEC61β plasmid. Plasmid transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). WT HA-LIPIN1 and the HA-LIPIN1(D712A) mutant were generated previously42. To construct AGPAT2 plasmids, AGPAT2 was PCR-amplified from cDNAs derived from MEFs and HEK293T cells and then cloned into either the pHR-SIN plasmid or the Clontech pEGFP plasmid, replacing the GFP gene. Mutations in the highly conserved amino acid residues in the catalytic motifs were introduced through site-directed mutagenesis using PCR with primers carrying specific mutations33,40,41. The WT and mutant alleles were confirmed by DNA sequencing of the plasmids. Epitopes, HA and FLAG, were fused to AGPAT2 by adding their sequences in PCR primers. To produce lentiviruses, the pHR-SIN plasmids carrying GFP-SEC61β, mCherry-SEC61β, AGPAT2-FLAG, AGPAT2-HA, AGPAT1-FLAG, RTN4A-GFP, and HA-LIPIN1 were co-transfected into HEK293T cells along with two other plasmids, pHR-CMV8.2ΔR and pCMV-VSVG, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)31. Two days after transfection, the supernatant containing the released viruses was collected from the transfected cells. The viruses were quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. To generate shRNA lentiviruses, the following target sequences were cloned into pLKO.1: Scramble (CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG), AGPAT1 (CGTTCTGAGGAGCAATCTATC), and AGPAT2 (CCTGTGTCATCATCTCTAATC).

Knockdown screen

WT MEFs expressing GFP-SEC61β were individually transfected with 18 esiRNAs (6 AGPATs, 2 PLDs, 9 DGKs, 1 control RLuc) and one silencer select siRNA for Dgkz, as its esiRNA was not available, using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in two independent experiments. The cells were fixed with pre-warmed 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature and were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 8 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with anti-GFP antibodies to enhance the GFP-SEC61β signal, in PBS containing 0.5% BSA, followed by incubation with Alexa 488 anti-rabbit IgG (A21206, Invitrogen). The samples were examined using a Zeiss LSM800 laser scanning confocal microscope. In control cells (RLuc knockdown), ER tubules constituted ~50% of the ER network. Based on our previous work, we set a threshold of approximately half the control level as the criterion for a positive hit31. This level of reduction can be readily identified by visual inspection without quantification. Therefore, to efficiently screen many genes, we qualitatively assessed ER morphology without percentage quantification. In all knockdown conditions, ER tubule levels were comparable to those in control cells, except for AGPAT2 knockdown, which consistently showed a marked reduction in ER tubules in both experimental replicates.

qPCR

Cells were plated on 24-well plates. Total RNAs were purified from the cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed using the ReadyScript cDNA Synthesis Mix (RDRT, Sigma-Aldrich). qPCR was performed using the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (A25741, Thermo Fisher Scientific). GAPDH was used as the reference gene. The following primers were used:

Mouse AGPAT1: CCCTACGTGGTTGTGTCCAA and AGTAGCTCACGCTTGGCAAT

Mouse AGPAT2: CCAAGGTCGGTCTCTACTGC and GCGAAGGCCATACACGTACTTG

Human AGPAT2: GACGGTGGAGAACATGAGCATC and GGAGACGATGACACAGGGAC

Mouse GAPDH: AAGGTCATCCCAGAGCTGAA and CTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA

Human GAPDH: CATGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCCT and AGTCCTTCCACGATACCAAAGT

Western blotting

Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The primary antibodies used were: DRP1 (1:2000, 611113, BD Biosciences), TIM23 (1:1000, 611223, BD Biosciences), HA (1:10000, NB600-362, Novus Biologicals), RTN4 (1:1000, ab47085, Abcam), RTN3 (1:1000, 12055-2-AP, Proteintech), GAPDH (1:10000, MA5-15738, Thermo Fisher Scientific), tubulin (1:1000, 2125, Cell Signaling Technology), FLAG (1:2000, F7425, Sigma-Aldrich), AGPAT2 (1:1000, 14937S, Cell Signaling Technology), Climp-63 (1:100, sc-393544, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), BiP (1:1000, 3183, Cell Signaling Technology), eIF2α (1:1000, 2103, Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-eIF2α (1:1000, 3597, Cell Signaling Technology), CHOP (1:1000, 2895, Cell Signaling Technology), GFP31,72 and actin (1:1000, sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunocomplexes were visualized using fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies, including Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000, A21202, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000, A21206, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-goat IgG (1:2,000, A21467, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000, A31571, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:2,000, A31573, Invitrogen), and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-goat IgG (1:2,000, A21447, Invitrogen), and detected with a Typhoon Molecular Imager (Amersham). To quantify band intensity, bands were boxed and mean values were measured using NIH Fiji software31. Background intensity was also measured in the corresponding region in a negative control lane and subtracted from the band intensity.

Lipid dot blot assay

Membrane lipid strips (P-6002, Echelon) were rehydrated and blocked in PBS containing 3% fatty acid free BSA (A3070, Sigma) and 1% Tween-20 for 1 hour at room temperature42. After washing in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), the membranes were incubated with 1 μg/ml GFP (Ag33633, Proteintech) or GFP-D-octadecapeptide in 2 ml of binding buffer (100 mM NaCl and 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) overnight at 4 °C with gentle mixing. The membranes were washed in PBST three times for 10 min and incubated with anti-GFP antibodies in PBST containing 3% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The immunocomplexes were visualized using fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies.

Liposome flotation assay

DOPC (850457), DPPG (840455), DPPS (840037), and rhodamine-DPPE (810158) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. DPPA (L-4116), DPCL (L-C160), PI(4)P (P-4016), and PI(4,5)P₂ (P-4516) were obtained from Echelon Biosciences. Lipids were mixed at a molar ratio of 84:1:15 for POPC:rhodamine-DPPE:variable lipid(s)42. The lipids were dried under a stream of nitrogen gas for 5 minutes, followed by further drying in a SpeedVac overnight. The dried lipid film was resuspended to a final concentration of 2 mM in 150 mM KCl and 20 mM MES (pH 7.0), vortexed for 1 h, and subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen and a 42 °C heat block. Unilamellar liposomes were generated by extrusion through a 400 nm polycarbonate membrane (21 passes)42. Liposomes (1 mM total lipid) were incubated with 1 μM GFP or GFP-D-octadecapeptide in a final volume of 200 μl at 4 °C for 1 h with gentle mixing. The mixture was diluted in 1.728 M sucrose and 20 mM MES (pH 7.0) to a final volume of 1.25 ml and placed at the bottom of an ultracentrifuge tube. A sucrose step gradient was formed by overlaying 2.9 ml of 1.25 M sucrose in 20 mM MES (pH 7.0), followed by 0.85 ml of 0.25 M sucrose in the same buffer. The samples were centrifuged at 55,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C using an SW55Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter). Two 2.5-ml fractions were collected from the top. Liposomes were recovered in the upper fractions42. Both upper and lower fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-GFP antibodies.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed with pre-warmed 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature in 8-well chambered coverglasses42. The cells were then permeabilized with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 8 min at room temperature. Alternatively, to selectively permeabilize the plasma membrane, cells were treated with PBS containing 5% BSA and 0.1% saponin for 30 min at room temperature. Following permeabilization, cells were washed with PBS containing 1% BSA. They were then incubated with primary antibodies in PBS with 0.5% BSA, followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibodies. The primary antibodies used were: DRP1 (1:300, 611113, BD Biosciences), PDH subunit E2/E3bp (1:300, ab110333, Abcam), FLAG (1:300, 66008-3-Ig, Proteintech), GFP (to enhance GFP-SEC61β)31,72, mCherry (1:10000, M11217, Invitrogen, to enhance mCherry-SEC61β), and HA (1:300, NB600-362, Novus Biologicals, to detect AGPAT2-HA and HA-LIPIN1). Immunocomplexes were visualized using fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies, including Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:400, A21206, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:400, A10037, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-goat IgG (1:400, A11057, Invitrogen), and Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-rat IgG (1:400, ab175475, Abcam). The samples were examined using a Zeiss LSM800 laser scanning confocal microscope73.

To quantify ER morphology, we measured the area of the cell occupied by the ER—whether composed of tubules or sheets—using the ER marker SEC61β fused to GFP31. The total ER area was defined as the combined area occupied by ER tubules and sheets. The area of ER tubules was calculated by subtracting the sheet area from the total ER area. To determine the relative abundance of tubular ER, the tubule area was divided by the total ER area, yielding the percentage of the area occupied by the tubular form (Tubular ER %). This measurement reflects the spatial coverage of the ER tubule network within the cell, rather than the membrane surface area of individual tubules. All measurements were performed using NIH Fiji software.

For quantifying the distribution of mCherry-SEC61β, AGPAT2-FLAG, and RTN4A-GFP in the ER, the relative fluorescence intensity of the signal from these proteins in the area covered by ER tubules was measured in comparison to the total fluorescence intensity. For super-resolution imaging, the samples were viewed using a Zeiss LSM880-Airyscan FAST Super-resolution Single-point, laser scanning confocal microscope. Image analysis was performed using Zen and Imaris software31.

Focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM)

WT, DRP1-KO, and AGPAT2-KO MEFs were pre-fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4, Electron Microscopy Sciences) at Johns Hopkins University and then shipped to the University of Michigan’s Microscopy Core34 overnight at ice temperature. The cells were subjected to post-fixation in a mixture of 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO₄) and 1% potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 15 min at ice temperature. The fixed cells were then contrasted with 1% thiocarbohydrazide, 1% OsO₄, and 1% uranyl acetate, each for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were further treated with Walton’s lead aspartate for 10 min at 60 °C. The cells were dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%) and embedded in Durcupan resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in beam capsules. After thermal polymerization at 70 °C for 48 hours, the glass coverslip was removed by liquid nitrogen, and the cell monolayer was transferred to the surface of the resin block. The samples were serially sectioned from the side of the resin block close to the coverslip using a Leica EM ARTOS 3D ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems) with a diamond knife (DiATOME). 600 µm × 600 µm sections with 1 µm thickness were obtained. Six to seven serial sections were manually transferred to a 10 × 10 mm Si wafer by submerging the Si wafer as 3 quarters as into the diamond knife trough filled with water and inclined facing the diamond knife edge. The serial sections were anchored to the horizontal line between the Si chip and water. Then water in the diamond knife trough was very slowly drained until the sections were attached on the Si wafer and the sections were dried on a heat block at 45 °C for 3 h. During these processes, the order of the serial sections was maintained. The serial sections on the Si wafer were coated with a 5 nm thick carbon layer using a Leica EM ACE 600 high vacuum coater (Leica Microsystems). The first or second section from each group (1-2 µm from the bottom of the cells, where the ER is usually observed) was observed using an EVO 15 LaB6 SEM (Carl Zeiss USA) at 10 keV with a high-definition backscattered detector to identify regions containing the ER in these sections. The ER was imaged at 1000 × magnification, with ~10 nm resolution and a 6144 × 4608-pixel output prior to FIB-SEM analysis.

For FIB-SEM analysis, samples were imaged using a FEI Helios Nanolab 650 Dual Beam system equipped with a gas injection system for platinum deposition and milling, at the Michigan Center for Materials Characterization. Using back-scattered electron imaging at 10 kV accelerating voltage, we located the same region of interest containing the ER. Once the region of interest was found, a platinum rectangle was deposited on a 6 × 8 μm region at 10 kV and 0.8 nA, followed by a protective deposition of carbon at 30 kV and 0.23 nA. Rough trenches around the region were cut using 30 kV and 9.3 nA beam current. The region of interest was lift-out and transferred to a new Si wafer using a micromanipulator (Omniprobe 200). The sample face was polished using 2.5 nA and 0.79 nA beam currents. The selected block was sequentially cut and imaged to obtain an image stack for 3D reconstruction using Auto Slice and View G3 V1.3 software. FIB cuts were made using 30 kV accelerating voltage and 80 pA beam current, while image of the block face was done using the SEM at 2 kV, set in backscatter mode. The field of view of the SEM and the slice thickness were set to produce 5 nm cubic voxels. The dimensions of the imaged blocks (width × height × thickness) were 8.1 × 6.8 × 0.4 µm for WT cells, 8.0 × 7.0 × 0.5 µm for DRP1-KO cells, and 8.4 × 6.4 × 0.5 µm for AGPAT2-KO cells. The resulting stack of images was aligned and reconstructed using Avizo v.9.3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Imaris 9.3 (Oxford Instruments). Manual segmentation was performed to determine the boundaries of the ER features contained in the image stack dataset34.

Isolation of the ER

Cells were cultured, washed with ice-cold PBS, and placed on ice. Homogenization buffer [10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4) containing 0.22 M mannitol, 0.07 M sucrose, and protease inhibitors (11836170001, Roche)] was added, and cells were collected using a cell scraper31. The cells were washed twice for 5 min each at 4 °C. To isolate the ER and mitochondria, cells were homogenized with 10 strokes using a syringe fitted with a 27-gauge needle in the same buffer. The postnuclear supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 800 g for 5 min and then for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was further separated into an ER-enriched supernatant and a mitochondria-enriched pellet by centrifugation at 8000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The ER-enriched supernatant was further clarified by centrifugation at 17,400 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Finally, the supernatant was separated into the ER pellet and the cytosolic supernatant by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4 °C31. To isolate the ER for in vitro AGPAT2 activity assays, cells were homogenized with 30 strokes using a PYREX homogenizer (7725T-5) and purified as described above.

Lipidomics

Lipid species were profiled using a multidimensional mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics approach74. The protein concentration of each isolated ER sample was quantified using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225, Thermo Scientific). Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard. An adequate amount of each sample (equivalent to 0.1 mg protein) was transferred into a disposable glass culture test tube. A premixed solution of lipid internal standards (IS), including di14:1 choline glycerophospholipid (PC), di16:1 ethanolamine glycerophospholipid (PE), di15:0 phosphatidylglycerol (Na) (PG), di14:0 phosphatidylserine (Na) (PS), di14:0 phosphatidic acid (Na) (PA), and 17:0 lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), was added prior to lipid extraction for quantification of the targeted lipid species75. Lipid extraction was performed using a modified Bligh and Dyer procedure74. The organic and aqueous phases were collected separately into new glass tubes.

The aqueous phase was used to extract LPA. Briefly, an equal volume of 4% formic acid in methanol was added to the aqueous phase and vortexed for 30 s. A HybridSPE cartridge was preconditioned twice with 2 ml of methanol. The aqueous solution was then loaded onto the cartridge to recover and enrich LPA species from biological matrices. The SPE column was washed twice with 2 ml of methanol, and the lipids trapped in the column were eluted with 4 ml of 20% ammonium methanol solution and dried under a nitrogen stream76. The lipid extract for LPA analysis was resuspended at 100 μl/mg of protein in methanol and stored at -20 °C until use.

The organic phase from the Bligh and Dyer extraction was used to isolate other lipids. To minimize oxidation and preserve lipid integrity, the lipid extracts were flushed with nitrogen gas, sealed with caps, and stored at -80 °C. Before lipidomic analysis, the extracts were resuspended in a chloroform:methanol mixture (1:1, v/v) at 500 μL/mg of protein. A 10 μl aliquot of each extract was used for derivatization of PE and DAG, respectively77,78. All samples were analyzed within one month of extraction.

For shotgun lipidomics, individual lipid extracts were further diluted to a final concentration of ~500 fmol total lipids per μL for mass spectrometric analysis. Data acquisition for PC, PE, and LPA was performed on a TSQ Altis triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Data acquisition for PS, PG, PA, and PI was performed on a Q-Exactive hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). An automated nanospray ion source (TriVersa NanoMate, Advion Bioscience) was used for sample introduction59.

Data were processed following standard principles of shotgun lipidomics, including ion peak selection, baseline correction, and isotope deconvolution61,75,79. Internal standards were applied to correct for extraction efficiency and matrix effects. Minimal batch variation was observed due to normalization procedures. Final lipid levels were expressed as nmol per mg of protein. Details on the linear dynamic range, signal-to-noise threshold, and quality control procedures followed previously established protocols59,74.

DRP1 expression and purification

Rosetta 2(DE3) pLysS competent cells (Novagen) were transfected with pET15b vectors carrying DRP1 and were grown in LB containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol overnight at 37 °C42. 1 ml of the culture was diluted into 1 L of the same growth medium and continued to grow for 3–5 hours at 37 °C. The culture was cooled down on ice, and 0.1 mM of IPTG was added. The expression of His6-DRP1 (mouse isoform 3, Uniprot: Q8K1M6-3)80,81, His6-DRP1 (K38A, G350D), and His6-GFP-D-octadecapeptide was induced overnight at 16 °C. The bacteria were washed twice with PBS by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C in a JLA8.1000 rotor and harvested and froze at -80 °C. The frozen cell pellets were resuspended in 40 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM imidazole, 1 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) and sonicated on ice for 10 × 5 sec at setting 5 and then 10 × 5 sec at setting 2 using a Fisher Scientific Sonic dismembrator model 100. The cell homogenate was centrifuged at 1935 × g for 15 min at 4 °C in JA-20X, and the supernatant was further clarified at 20,100 × g for 15 min at 4 °C in JA-20X. After being passed through a membrane filter with a pore size of 0.45 μm, the lysate was incubated with 2 ml of pre-washed 50% Ni-NTA beads (His-Bind Resin, Novagen) overnight at 4 °C and placed in a 15-ml column (Poly-prep chromatography column, Bio-Rad). The beads were washed with 3 ml of lysis buffer, 15 ml of lysis buffer, 3 ml of wash buffer (40 mM imidazole, 1 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4), and 15 ml of wash buffer. The His6-tagged recombinant proteins were eluted from the column using 3 × 0.9 ml of elution buffer (250 mM imidazole, 1 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) and collected it into nine 300-μl fractions. After confirming the purification of proteins using SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining of each fraction, the peak fractions (typically fractions #3 and 4) were collected and diluted into 15 ml of lysis buffer without imidazole. The residual imidazole was removed by passing the solution three times through an Amicon Ultra Centrifugation Filter (50 kDa MWCO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified proteins were mixed with final 20% DMSO, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C.

In vitro ER tubulation assay

Freshly purified ER (7.5 µg of proteins in 50 µl) was incubated with or without recombinant DRP1 protein and 8:0 PA (830842, Avanti) in 150 mM KCl and 20 mM MES (pH 7.0) at 23 °C for 3 h. We selected 8:0 PA based on preliminary experiments comparing the solubility of PA species with different acyl chain lengths (8:0 and 10:0) under our assay conditions, in which 8:0 PA remained soluble while 10:0 PA (830843, Avanti) precipitated out of solution. As a negative control, GFP protein (Ag33633, Proteintech) was used. For negative-stain electron microscopy, 20 μl of the samples were placed on EM grids (CF400-CU-UL, Electron Microscopy Sciences) that had been glow-discharged using a Quorum GloQube-D (Laughton)31. After an incubation period of 2 min, the grids were washed three times with 150 mM KCl and 20 mM MES (pH 7.0), stained with 0.1% uranyl acetate and 0.04% Tylose for 30 seconds twice, and then air-dried. The samples were examined using a Hitachi 7600 transmission electron microscope31. The length of tubules was analyzed using NIH Fiji software. Small vesicles with an area less than 0.05 µm2 were excluded from the analysis.

To test the effect of antibodies on ER tubules, freshly purified ER (7.5 µg of protein in 50 µl) was incubated with 12.5 µg/ml of TOM20 antibody (612278, BD Biosciences) or DRP1 antibody (611113, BD Biosciences) in a buffer containing 150 mM KCl and 20 mM MES (pH 7.0) at room temperature for 3 h. Electron microscopy sample preparation, negative staining, and length analysis were performed as described above.

In vitro AGPAT2 activity assay

Freshly isolated ER (30 µg of proteins) was incubated with 50 µM 18:0 acyl-CoA (870718, Avanti) and 10 µM lysoPA-TopFluor (810280, Avanti) in 200 µl of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 1 mg/ml of fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (A7030, Sigma) for 10 min at 37 °C. Lipids were extracted using 200 µl of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) at room temperature for 1 h with gentle agitation. The extracted lipid samples were applied to a TLC plate (60805, Sigma) and developed in a solvent system of chloroform/ethanol/water in a ratio of 65:25:4 (v/v/v). NBD-PA (810174 P, Avanti) was used as lipid markers. After development, the TLC plates were dried and the lipid spots were visualized and scanned using a Typhoon imager system.

Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were cultured in 10-cm dishes and transfected with various plasmids using Lipofectamine 300042. Two days after transfection, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, placed on ice, and lysed with 0.5 ml of ice-cold 1x lysis buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail (11836170001, Roche)]. The samples were gently homogenized by pipetting on ice for 15 min. The homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C in a microcentrifuge twice. A total of 500 µl of the supernatants was then incubated with either 10 µl of Anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (A2220, Sigma), GFP-Trap (ChromoTek), or 10 µl of Protein A-Sepharose 4B (101041, Life Technologies) combined with 5 µl of DRP1 antibody (110-55288, Novus Biologicals) for 3 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with 1x lysis buffer. The clarified cell lysates and immunoprecipitated fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using antibodies specific for DRP1 (611113, BD), FLAG (F7425, Sigma), AGPAT2 (14937S, Cell Signaling), and GAPDH (MA5-15738, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Immunocomplexes were visualized using fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies and detected using a Typhoon Molecular Imager (Amersham). To quantify band intensity, bands were boxed and mean values were measured using NIH Fiji software31. Background intensity was also measured in the corresponding region in a negative control lane and subtracted from the band intensity.

Statistical and Reproducibility

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10. Sample sizes were not predetermined by statistical methods, and experiments were not blinded. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized, and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during either the experiments or the outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the main text, the Supplementary Information, and the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Nixon-Abell, J. et al. Increased spatiotemporal resolution reveals highly dynamic dense tubular matrices in the peripheral ER. Science 354, aaf3928 (2016).

Terasaki, M. et al. Stacked endoplasmic reticulum sheets are connected by helicoidal membrane motifs. Cell 154, 285–296 (2013).

Guo, Y. et al. Visualizing intracellular organelle and cytoskeletal interactions at nanoscale resolution on millisecond timescales. Cell 175, 1430–1442.e1417 (2018).

Chen, S., Novick, P. & Ferro-Novick, S. ER structure and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 25, 428–433 (2013).

Schroeder, L. K. et al. Dynamic nanoscale morphology of the ER surveyed by STED microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 218, 83–96 (2019).

Terasaki, M. A finer look at a fine cellular meshwork. Science 354, 415–416 (2016).

Gubas, A. & Dikic, I. ER remodeling via ER-phagy. Mol. Cell 82, 1492–1500 (2022).

Palade, G. Intracellular aspects of the process of protein synthesis. Science 189, 867 (1975).

Terasaki, M., Song, J., Wong, J. R., Weiss, M. J. & Chen, L. B. Localization of endoplasmic reticulum in living and glutaraldehyde-fixed cells with fluorescent dyes. Cell 38, 101–108 (1984).

Voeltz, G. K., Sawyer, E. M., Hajnoczky, G. & Prinz, W. A. Making the connection: How membrane contact sites have changed our view of organelle biology. Cell 187, 257–270 (2024).

Parlakgul, G. et al. Regulation of liver subcellular architecture controls metabolic homeostasis. Nature 603, 736–742 (2022).

Naon, D. et al. Splice variants of mitofusin 2 shape the endoplasmic reticulum and tether it to mitochondria. Science 380, eadh9351 (2023).

Lewis, S. C., Uchiyama, L. F. & Nunnari, J. ER-mitochondria contacts couple mtDNA synthesis with mitochondrial division in human cells. Science 353, aaf5549 (2016).

Scorrano, L. et al. Coming together to define membrane contact sites. Nat. Commun. 10, 1287 (2019).

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. ER-mitochondria tethering by PDZD8 regulates Ca(2+) dynamics in mammalian neurons. Science 358, 623–630 (2017).

Korobova, F., Ramabhadran, V. & Higgs, H. N. An actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the ER-associated formin INF2. Science 339, 464–467 (2013).

Hernandez-Alvarez, M. I. et al. Deficient Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Phosphatidylserine Transfer Causes Liver Disease. Cell 177, 881–895.e817 (2019).

Tamura, Y., Kawano, S. & Endo, T. Organelle contact zones as sites for lipid transfer. J. Biochem 165, 115–123 (2019).

Shibata, Y. et al. Mechanisms determining the morphology of the peripheral ER. Cell 143, 774–788 (2010).

Hu, J. et al. A class of dynamin-like GTPases involved in the generation of the tubular ER network. Cell 138, 549–561 (2009).

Hu, J. et al. Membrane proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum induce high-curvature tubules. Science 319, 1247–1250 (2008).

Voeltz, G. K., Prinz, W. A., Shibata, Y., Rist, J. M. & Rapoport, T. A. A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 124, 573–586 (2006).

Murata, D., Arai, K., Iijima, M. & Sesaki, H. Mitochondrial division, fusion and degradation. J. Biochem 167, 233–241 (2020).

Kraus, F., Roy, K., Pucadyil, T. J. & Ryan, M. T. Function and regulation of the divisome for mitochondrial fission. Nature 590, 57–66 (2021).

Kameoka, S., Adachi, Y., Okamoto, K., Iijima, M. & Sesaki, H. Phosphatidic acid and cardiolipin coordinate mitochondrial dynamics. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 67–76 (2018).

Giacomello, M., Pyakurel, A., Glytsou, C. & Scorrano, L. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 204–224 (2020).

Friedman, J. R. & Nunnari, J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature 505, 335–343 (2014).

van der Bliek, A. M., Sedensky, M. M. & Morgan, P. G. Cell Biology of the Mitochondrion. Genetics 207, 843–871 (2017).

Quintana-Cabrera, R. & Scorrano, L. Determinants and outcomes of mitochondrial dynamics. Mol. Cell 83, 857–876 (2023).

Tamura, Y., Itoh, K. & Sesaki, H. SnapShot: mitochondrial dynamics. Cell 145, 1158 (2011).

Adachi, Y. et al. Drp1 Tubulates the ER in a GTPase-Independent Manner. Mol. Cell 80, 621–632.e626 (2020).

Yamada, S., Sato, A., Ishihara, N., Akiyama, H. & Sakakibara, S. I. Drp1 SUMO/deSUMOylation by Senp5 isoforms influences ER tubulation and mitochondrial dynamics to regulate brain development. iScience 24, 103484 (2021).

Takeuchi, K. & Reue, K. Biochemistry, physiology, and genetics of GPAT, AGPAT, and lipin enzymes in triglyceride synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296, E1195–E1209 (2009).

Zhou, Z. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation regulates mitochondrial dynamics in brown adipocytes. Science 368, 54–60 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Deep learning-based morphological classification of endoplasmic reticulum under stress. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 767866 (2021).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Dobson, L. et al. TmAlphaFold database: membrane localization and evaluation of AlphaFold2 predicted alpha-helical transmembrane protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D517–D522 (2023).

Hatch, A. L., Ji, W. K., Merrill, R. A., Strack, S. & Higgs, H. N. Actin filaments as dynamic reservoirs for Drp1 recruitment. Mol. Biol. Cell 27, 3109–3121 (2016).

Francy, C. A., Alvarez, F. J., Zhou, L., Ramachandran, R. & Mears, J. A. The Mechanoenzymatic Core of Dynamin-related Protein 1 Comprises the Minimal Machinery Required for Membrane Constriction. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 11692–11703 (2015).

Yamashita, A. et al. Topology of acyltransferase motifs and substrate specificity and accessibility in 1-acyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1. Biochim Biophys. Acta 1771, 1202–1215 (2007).

Yamashita, A. et al. Glycerophosphate/Acylglycerophosphate acyltransferases. Biol. (Basel) 3, 801–830 (2014).

Adachi, Y. et al. Coincident phosphatidic acid interaction restrains Drp1 in mitochondrial division. Mol. Cell 63, 1034–1043 (2016).

Vance, J. E. Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells. Traffic 16, 1–18 (2015).

Tatsuta, T., Scharwey, M. & Langer, T. Mitochondrial lipid trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 44–52 (2014).

van Meer, G., Voelker, D. R. & Feigenson, G. W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. cell Biol. 9, 112–124 (2008).

Tamura, Y., Kawano, S. & Endo, T. Lipid homeostasis in mitochondria. Biol. Chem. 401, 821–833 (2020).

Shi, Y. & Burn, P. Lipid metabolic enzymes: emerging drug targets for the treatment of obesity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 695–710 (2004).

Zhang, J. et al. De novo labeling and trafficking of individual lipid species in live cells. Mol. Metab. 61, 101511 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Temporal production of the signaling lipid phosphatidic acid by phospholipase D2 determines the output of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 84–95 (2014).

Holthuis, J. C. & Menon, A. K. Lipid landscapes and pipelines in membrane homeostasis. Nature 510, 48–57 (2014).

Harayama, T. & Riezman, H. Understanding the diversity of membrane lipid composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 281–296 (2018).

Nishioka, T., Frohman, M. A., Matsuda, M. & Kiyokawa, E. Heterogeneity of phosphatidic acid levels and distribution at the plasma membrane in living cells as visualized by a Foster resonance energy transfer (FRET) biosensor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35979–35987 (2010).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature, 630, 493–500(2024).

Clinton, R. W., Francy, C. A., Ramachandran, R., Qi, X. & Mears, J. A. Dynamin-related Protein 1 Oligomerization in Solution Impairs Functional Interactions with Membrane-anchored Mitochondrial Fission Factor. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 478–492 (2016).

Rochon, K. et al. Structural basis for regulated assembly of the mitochondrial fission GTPase Drp1. Nat. Commun. 15, 1328 (2024).

Kalia, R. et al. Structural basis of mitochondrial receptor binding and constriction by DRP1. Nature 558, 401–405 (2018).

Perez-Jover, I. et al. Allosteric control of dynamin-related protein 1 through a disordered C-terminal Short Linear Motif. Nat. Commun. 15, 52 (2024).

Frohlich, C. et al. Structural insights into oligomerization and mitochondrial remodelling of dynamin 1-like protein. EMBO J. 32, 1280–1292 (2013).

Han, X., Yang, K. & Gross, R. W. Microfluidics-based electrospray ionization enhances the intrasource separation of lipid classes and extends identification of individual molecular species through multi-dimensional mass spectrometry: development of an automated high-throughput platform for shotgun lipidomics. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22, 2115–2124 (2008).

Wang, M., Wang, C., Han, R. H. & Han, X. Novel advances in shotgun lipidomics for biology and medicine. Prog. Lipid Res. 61, 83–108 (2016).

Yang, K., Cheng, H., Gross, R. W. & Han, X. Automated lipid identification and quantification by multidimensional mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics. Anal. Chem. 81, 4356–4368 (2009).

Patni, N. & Garg, A. Congenital generalized lipodystrophies—new insights into metabolic dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11, 522–534 (2015).

Papagiannidis, D. et al. Ice2 promotes ER membrane biogenesis in yeast by inhibiting the conserved lipin phosphatase complex. EMBO J. 40, e107958 (2021).

Han, G. S., Kwiatek, J. M., Hu, K. S. & Carman, G. M. Catalytic core function of yeast Pah1 phosphatidate phosphatase reveals structural insight into its membrane localization and activity control. J. Biol. Chem. 300, 105560 (2024).

Siniossoglou, S., Santos-Rosa, H., Rappsilber, J., Mann, M. & Hurt, E. A novel complex of membrane proteins required for formation of a spherical nucleus. EMBO J. 17, 6449–6464 (1998).

Han, G. S., Siniossoglou, S. & Carman, G. M. The cellular functions of the yeast lipin homolog PAH1p are dependent on its phosphatidate phosphatase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37026–37035 (2007).

Schuck, S., Prinz, W. A., Thorn, K. S., Voss, C. & Walter, P. Membrane expansion alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress independently of the unfolded protein response. J. Cell Biol. 187, 525–536 (2009).

Santos-Rosa, H., Leung, J., Grimsey, N., Peak-Chew, S. & Siniossoglou, S. The yeast lipin Smp2 couples phospholipid biosynthesis to nuclear membrane growth. EMBO J. 24, 1931–1941 (2005).

Macdonald, P. J. et al. A dimeric equilibrium intermediate nucleates Drp1 reassembly on mitochondrial membranes for fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 1905–1915 (2014).

Ugarte-Uribe, B., Muller, H. M., Otsuki, M., Nickel, W. & Garcia-Saez, A. J. Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) promotes structural intermediates of membrane division. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 30645–30656 (2014).

Lu, B. et al. Steric interference from intrinsically disordered regions controls dynamin-related protein 1 self-assembly during mitochondrial fission. Sci. Rep. 8, 10879 (2018).

Senoo, H. et al. Phosphorylated Rho-GDP directly activates mTORC2 kinase towards AKT through dimerization with Ras-GTP to regulate cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 867–878 (2019).

Yamada, T. et al. Mitochondrial Stasis Reveals p62-mediated ubiquitination in parkin-independent mitophagy and mitigates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metab. 28, 588–604 (2018).

Wang, M. & Han, X. Multidimensional mass spectrometry-based shotgun lipidomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 1198, 203–220 (2014).

Wang, M., Wang, C. & Han, X. Selection of internal standards for accurate quantification of complex lipid species in biological extracts by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry-What, how and why? Mass Spectrom. Rev. 36, 693–714 (2017).

Wang, C., Wang, M. & Han, X. Comprehensive and quantitative analysis of lysophospholipid molecular species present in obese mouse liver by shotgun lipidomics. Anal. Chem. 87, 4879–4887 (2015).

Han, X., Yang, K., Cheng, H., Fikes, K. N. & Gross, R. W. Shotgun lipidomics of phosphoethanolamine-containing lipids in biological samples after one-step in situ derivatization. J. Lipid Res 46, 1548–1560 (2005).

Wang, M., Hayakawa, J., Yang, K. & Han, X. Characterization and quantification of diacylglycerol species in biological extracts after one-step derivatization: a shotgun lipidomics approach. Anal. Chem. 86, 2146–2155 (2014).

Yang, K. & Han, X. Accurate quantification of lipid species by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry - Meet a key challenge in lipidomics. Metabolites 1, 21–40 (2011).

Itoh, K. et al. A brain-enriched Drp1 isoform associates with lysosomes, late endosomes, and the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 11809–11822 (2018).

Itoh, K. et al. Brain-specific Drp1 regulates postsynaptic endocytosis and dendrite formation independently of mitochondrial division. Elife 8, e44739 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Iijima and Sesaki labs for their invaluable discussions and technical assistance. This work is supported by grants from NIH: R35GM131768 (MI), R35GM144103 (HS), and R35GM130292 and R01DK137794 for 3D analysis (LQ). Lipidomics analysis at Barshop Institute for longevity and Aging Studies, University of Texas Health San Antonio was partially supported by NIH grants (P30AG013319 and P30AG044271).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.A., M.I., H.S. Investigation: Y.A., M.T. (F.I.B.-S.E.M.), W.J.C. (F.I.B.-S.E.M.), A.H.H. (F.I.B.-S.E.M.), M.P. (Lipidomics), M.I. Resources: M.I., G.D., H.S. Funding acquisition: M.I., X.H. (Lipidomics), L.Q. (F.I.B.-S.E.M.), H.S. Project administration: M.I., H.S. Supervision: M.I., X.H. (Lipidomics), L.Q. (F.I.B.-S.E.M.), H.S. Writing–original draft: Y.A., M.I., H.S. Writing – review & editing: Y.A., M.T., L.Q., M.I., H.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions