Abstract

A thorough understanding of vegetation resilience to climate variability is critical for sustaining ecosystem functions and terrestrial carbon sinks. Although the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a key driver of global extreme weather events and vegetation dynamics, its impacts on vegetation resilience remain unclear. Here we estimate global present-day (1981–2018) and future (2015–2100) vegetation resilience using a lag-1 autocorrelation analysis of global leaf area index (LAI) time series and investigate its teleconnection to ENSO. Our findings reveal that ENSO significantly affects vegetation resilience across 53% of the global vegetated area. Within these regions, 15% are linked primarily to large-scale atmospheric synchrony with ENSO, 51% are mainly shaped by ENSO-driven local climate anomalies, and the remaining 34% are influenced by both processes. Future projections suggest that the area impacted via ENSO-driven climate anomalies may expand by 7-10%, with Eastern Siberia and northern North America newly affected. Our study provides a coherent global assessment of vegetation resilience sensitivity to ENSO, identifies teleconnected hotspots and potential influential pathways, and informs targeted restoration and climate-adaptive ecosystem governance under climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vegetation resilience refers to the capacity of vegetation to maintain or recover its structure and function following disturbances1. However, the intensification of global climate change poses a significant threat to this resilience. Previous studies have predominantly focused on the relationship between resilience and temperature and precipitation patterns2,3,4, often neglecting the remote impacts of global climate oscillations such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). As the largest natural perturbation to the global climate on an interannual timescale5, ENSO significantly affects rainfall and temperature dynamics, thereby reshaping the distribution of meteorological hazards such as droughts and floods6,7, as well as secondary hazards such as wildfires8. These disruptions affect core ecological functions, including species composition, nutrient cycling, and energy flow, ultimately undermining vegetation resilience9. Moreover, with global warming, ENSO variability is expected to increase10, potentially amplifying its influence on plant growth and ecosystem stability worldwide11,12. Understanding the impact of ENSO on vegetation resilience is crucial for guiding nature-based solutions—such as reforestation, biodiversity protection, and climate-smart land management—that contribute to the UN Sustainable Development Goals13.

ENSO is a coupled ocean–atmosphere phenomenon involving periodic fluctuations in sea temperature and atmospheric pressure in the tropical Pacific14. It typically develops during the boreal summer and decays in the following spring15,16, with peak intensity usually occurring between December and February17. Through large-scale atmospheric circulation anomalies, ENSO alters regional patterns of temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation18,19, thereby disrupting vegetation biophysical processes20. Specifically, the alternating warm (El Niño) and cold (La Niña) phases of ENSO exert complex and spatially heterogeneous vegetation responses12. El Niño typically raises temperature and solar radiation in tropical and subtropical regions, yet its impact on precipitation varies, causing wetter conditions in some areas and drought in others, potentially exacerbating or alleviating vegetation water stress21,22,23. For instance, El Niño-driven shifts in the Intertropical Convergence Zone modify regional precipitation patterns, decreasing precipitation in West and northern Central Africa, while increasing it in East and southern Central Africa24, thus creating a contrasting north-south gradient in vegetation dynamics. Conversely, La Niña generally exhibits the opposite climatic signals, particularly over tropical land areas where temperature and precipitation patterns respond in antiphase, thereby partially offsetting the effects of El Niño25,26. However, this compensatory mechanism is modulated by variation in the location of equatorial warming and by nonlinear ocean–atmosphere interactions, leading to spatial asymmetries in the timing and intensity of vegetation response to ENSO phases27. Consequently, some regions, such as the Amazon rainforest, are highly sensitive to El Niño28,29, while others, like Australian shrublands, experience alternating impacts from both phases30.

More critically, high-intensity ENSO events can lead to irreversible declines in vegetation resilience. A notable example is the 2015–2016 extreme El Niño event, during which humid forests in Africa and the Americas experienced sustained reductions in aboveground carbon storage. Even after climate conditions normalized in 2017, recovery remained slower than in dryland ecosystems31,32. This contrast highlights that the effects of ENSO on vegetation are not solely determined by event intensity but are also influenced by ecosystem type, regional climatic conditions, and water availability33. Nevertheless, the magnitude and spatial distribution of ENSO’s effects on vegetation resilience remain poorly understood. This knowledge gap is particularly concerning given projections that ENSO events will undergo significant shifts in frequency, intensity, and impact patterns under a warming climate34,35, potentially exhibiting unprecedented disturbance characteristics that further complicate global vegetation resilience dynamics. Thus, a systematic assessment of the multi-scale impacts of diverse ENSO phases is urgently needed, with a particular focus on temporal and spatial variability across ecosystems and climate regions, as well as sustainability and evolution in future scenarios.

The critical slowing down theory (CSD) provides a framework for detecting ecosystem instability by suggesting that declining recovery rates precede state transitions, which can be identified by statistical signals like increased variance and higher first-order autocorrelation36,37,38. In this article, we applied this framework to quantify global-scale changes in vegetation resilience using remotely sensed Leaf Area Index (LAI) data since 1981. We hypothesized that ENSO influences on global vegetation resilience operate via two complementary perspectives: the atmospheric synchronization teleconnection, which captures the large-scale statistical association between ENSO events and resilience anomalies, independently of local climate variables; while the climate-mediated teleconnection, which reflects indirect influence transmitted through ENSO-driven anomalies in temperature, precipitation, and radiation (see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1). Together, these pathways reflect ENSO’s dual role as a synchronizer of global variability and a modulator of local climate conditions. Additionally, we used simulations from the CMIP6 model to analyze how ENSO’s impacts on vegetation resilience may evolve in the future. We present a coherent global-scale evaluation of how vegetation resilience responds to ENSO, pinpointing teleconnected hotspots and revealing key pathways of influence. These findings improve our understanding of the teleconnection between vegetation growth and extreme climate, supporting nature-based solutions and informing sustainable development efforts.

Results

Historical characteristics of vegetation resilience dynamics

We quantified vegetation resilience at the pixel level using lag-1 autocorrelation (AC) derived from 5-year moving windows of GLASS LAI data (1981–2018), and assessed its long-term trend (see Methods). This global assessment indicates that 41.56% of vegetated areas have experienced a statistically significant decline in resilience over the past 40 years, with considerable spatial heterogeneity (Fig. 1a). The most significant declines in resilience are observed in northern North America, the Amazon, northern Europe, eastern Australia, and northern and Southeast Asia, which exhibit the greatest increase in AC (Fig. 1a). Compared with the trend in variance, another CSD indicator, 78.4% of areas exhibit consistent resilience trends in both AC and variance estimates (see Methods, Fig. 1 b, c).

a lag-1 autocorrelation (AC) trend and b variance trend derived from Global Land Surface Satellite Leaf Area Index (GLASS LAI) data from 1981 to 2018. Trends are quantified using the Kendall’s tau statistic. Red regions indicate significant increases in AC or variance, which are indicative of declining vegetation resilience. c Trend agreement between AC and variance. d LAI time series trend (1981–2018). e Proportion of autocorrelation increase (ΔAC > 0) or decrease (ΔAC < 0) in greening (ΔLAI > 0) and browning (ΔLAI < 0) among different vegetation types. Vegetation types: ENF Evergreen Needleleaf Forests, EBF Evergreen Broadleaf Forests, DNF Deciduous Needleleaf Forests, DBF Deciduous Broadleaf Forests, MF Mixed Forests, CS Closed Shrublands, OS Open Shrublands, WS Woody Savannas. Basemap data© Esri; Garmin; GEODIS; GMI; CIA World Factbook.

Spatial patterns of historical changes in global vegetation resilience contrast with the dynamics of global vegetation greening. Regions such as the Amazon, south-central Africa, Southeast Asia, and western Oceania have experienced a widespread increase in greenness—measured by rising LAI—over the last four decades (see Methods, Fig. 1d), yet these areas have concurrently witnessed significant declines in resilience (Fig. 1a). In addition, over 40% of greening vegetation in global open shrublands, grasslands, evergreen broadleaf forests, and deciduous broadleaf forests exhibited a decline in resilience (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings highlight the simultaneous occurrence of accelerated vegetation greening and declining resilience worldwide.

Controlling factors of historical changes in global vegetation resilience

We used a random forest (RF) regression framework at the global scale to attribute temporal changes in vegetation resilience (AC) to ENSO variability and other environmental factors. This model focused on in-situ climate variability and ENSO as the key explanatory variables, incorporating other static in-situ factors such as topography and climate seasonality as constraints to reduce background interference (see Methods). The analysis reveals that climate seasonality exerts the strongest influence on shaping interannual variation, followed by climatic variability and topography (Fig. 2a; model R2 = 0.79). Among the controlling variables, temperature and radiation seasonality exert the strongest climatic control on resilience, and ecosystems experiencing low intra-annual variability are especially prone to resilience loss. Elevation emerges as the key terrain factor, with partial dependence analyses showing that high, steep, and well-drained landscapes are particular hotspots of vulnerability (Fig. 2e and f).

a Variables’ importance scores from the Random Forest (RF) model. Partial dependence plots (PDPs) show the influence of key predictors from each variable group on lag-1 autocorrelation (AC): b climatic variables, including El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), precipitation, temperature, and radiation; c Lag effects of ENSO at 1-, 2-, and 3-year intervals; d Climate-mediated teleconnection effects, calculated as the product of ENSO and in-situ climate variables. Positive and negative extremes represent high anomaly values associated with El Niño and La Niña events, respectively, while values near zero indicate low anomalies; e climatic seasonality, represented by intra-annual coefficient of variation (CV) of precipitation, temperature, and radiation (e.g., temperature_seas indicates temperature seasonality); and f topographic factors, including elevation, slope, and Height Above Nearest Drainage (HAND); lower HAND values denote poorer drainage potential. Basemap data ©Esri; Garmin; GEODIS; GMI; CIA World Factbook.

Focusing on baseline in-situ climatic factors (excluding ENSO effects), temperature had the strongest influence on resilience, followed by radiation, while precipitation had a relatively minor effect (Fig. 2a). These factors exhibited non-monotonic impacts, with resilience peaking under optimal climatic conditions (approximating climatological means, temperature = 275–280 K; precipitation = 50–100 mm/a; solar radiation = 100–150 W/m2), and declining when conditions deviated from this range (Fig. 2b, and Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, at a global scale, low precipitation, high temperature, and elevated solar radiation had a stronger impact on vegetation resilience compared to high precipitation, low temperature, and low radiation (Fig. 2b).

Although in-situ factors collectively explain a larger proportion of the resilience variation, ENSO teleconnections remain a critical global-scale forcing, driving resilience anomalies. ENSO primarily influences vegetation resilience through the climate-mediated teleconnection, driven by ENSO-induced climate anomalies, which exert a stronger impact than ENSO’s atmospheric synchronization teleconnection (Fig. 2a). Specifically, reduced vegetation resilience is closely associated with anomalously high temperatures, low precipitation, and enhanced solar radiation during El Niño events, as well as with low-temperature and low-precipitation anomalies under La Niña conditions (Fig. 2d). While these climate-mediated effects dominate overall, the atmospheric synchronization teleconnections of ENSO still matter: vegetation responds more rapidly and strongly to El Niño events than to La Niña during the event year (Fig. 2b). However, the lagged response of vegetation to ENSO is often a result of regional disparities, including distance from the tropical oceans and local topography like elevation and terrain complexity. With increasing lag time, the global impact of extreme La Niña events becomes more pronounced and, by the third year (the lag = 2), surpasses that of El Niño in shaping vegetation resilience dynamics (Fig. 2c). This temporal difference likely stems from the contrasting durations of the two phenomena: La Niña often persists into the second year and re-strengthens in the winter, whereas El Niño tends to terminate shortly after reaching its peak stage39.

An independent analysis targeting intact forest regions (see Methods) indicates that after excluding areas affected by human activities, vegetation responses to ENSO remain broadly consistent with the global-scale patterns (Supplementary Fig. 4). This suggests that while anthropogenic disturbances can influence vegetation responses at local scales, the large-scale climate–vegetation coupling associated with ENSO persists.

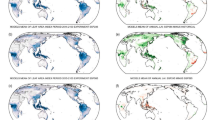

ENSO synchronization teleconnection affecting vegetation resilience

We applied a Pearson Chi-square test to evaluate whether vegetation resilience is temporally synchronized with ENSO over a long historical period, after removing the effects of in-situ climate variables (see Methods). The resulting spatial pattern indicates that 26% of vegetated regions exhibited significant relationships between vegetation resilience anomalies and the ENSO events (P < 0.05), with resilience demonstrating higher sensitivity to El Niño than La Niña events (Fig. 3a). Specifically, 6% of vegetated areas showed increased resilience during La Niña events, while 3.3% exhibited decreased resilience. During El Niño events, 9.4% of areas experienced increased resilience and 7.4% experienced decreased resilience (Fig. 3a). The detrimental impacts of El Niño were predominantly concentrated in northern Asia, Europe and America, and the southern Amazon, whereas the negative effects of La Niña were primarily distributed in southern Amazon and Central Asia and Africa (Fig. 3a). Evergreen broadleaf forests, grasslands and open shrublands were identified as the vegetation types most affected by these climatic phenomena (Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, the positive impacts of El Niño and La Niña are more spatially dispersed, with affected vegetation resilience distributed across most continents (Fig. 3a). These spatial distributions remained consistent across varying lag times. However, it is noteworthy that the spatial extent of El Niño’s synchronous negative impact decreased with increasing lag time, while the area experiencing negative impacts from La Niña remained relatively stable. Beyond a twelve-month lag, La Niña’s negative impact area exceeds that of El Niño (Supplementary Fig. 6), whereas the global-scale Random Forest analysis indicates that La Niña’s cumulative impact becomes dominant only after three years (Fig. 2c). This apparent difference reflects the distinct metrics captured by the two approaches—spatial extent versus aggregated strength—yet both consistently point to La Niña’s growing dominance with increasing lag time.

a Synchronization impact of El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on resilience. b Regional differences in lag-1 autocorrelation (AC) trends between affected and unaffected regions during 1981–2018. The dashed line represents the regional average. The inset box in the top right corner magnifies the difference in regional averages. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between groups based on both the Whitney U-test and Student’s t-test: p < 0.05(*); p < 0.01(**); p < 0.001(***). Climate-mediated teleconnection effects on vegetation resilience: c–e Impacts of ENSO-induced anomalies in temperature, solar radiation, and precipitation on vegetation resilience, respectively. f, g Combined impact of these climate anomalies during El Niño and La Niña on vegetation resilience, respectively; h Overall impact of ENSO-induced climate anomalies on vegetation resilience. Plus (+) and minus (−) signs indicate positive and negative impacts, respectively, with numbers indicating impact intensity, calculated as the sum of individual ENSO-climate anomaly impacts. Basemap data © Esri; Garmin; GEODIS; GMI; CIA World Factbook.

ENSO climate-mediated teleconnection affecting vegetation resilience

RF inference (Fig. 2d) suggests that ENSO-induced climate anomalies trigger resilience changes. By overlapping resilience-climate (Supplementary Fig. 7) and ENSO-climate (Supplementary Fig. 8) linkages, we reveal spatially heterogeneous coupling patterns, where ENSO-driven climate anomalies negatively affected 23% of vegetation resilience, predominantly in the Amazon rainforest and Brazilian Plateau region in central South America, the Congo Basin in south-central Africa, and northeastern Australia (Fig. 3h). Conversely, positive effects were observed in 22% of regions, primarily in northern Australia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Southeast Plains of South America (Fig. 3h). Among all anomalous events, 59% of the positive impacts were attributed to El Niño and 41% were linked to La Niña, while 63% of the negative impacts were associated with El Niño and 37% with La Niña (Fig. 3f, g). Particularly, the resilience of evergreen broadleaf forests in the Amazon and savannas in the Brazilian Plateau were negatively affected by El Niño-induced anomalies, including decreased precipitation, increased temperature, and increased solar radiation (Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). In contrast, La Niña-driven anomalies had considerable positive effects on the resilience of grasslands and open shrublands in northern Australia, although parts of the mountainous regions in northeastern Australia experienced negative resilience impacts from La Niña, driven by reductions in radiation, temperature, and precipitation (Fig. 3c-e and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). On a global scale, evergreen broadleaf forests, open shrublands, woody savannas, and savannas experienced the most pronounced negative impacts, whereas grasslands showed resilience linked to ENSO-driven solar radiation and precipitation variability (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

Impact of ENSO on the long-term vegetation resilience trend

To analyze the impact of ENSO events on the long-term resilience trend, we compared the historical AC trend between ENSO-affected and non-ENSO-affected regions. ENSO-affected regions, defined as areas experiencing synchronization or climate-mediated impacts, cover 53% of global vegetation. Within these regions, 15% are influenced directly by ENSO’s synchronization, 51% are affected solely through ENSO-induced climate anomalies (for example, abnormal temperature, precipitation, and radiation), and the remaining 34% are subject to both effects. In terms of ENSO phases, 61% of affected regions are linked to El Niño, while 39% are associated with La Niña.

Regardless of considering ENSO as a whole or its individual phases, the historical decline in vegetation resilience was significantly more pronounced in negatively affected regions compared to positively affected and non-ENSO-affected regions (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1–3). In contrast, the positive impact of ENSO did not lead to a corresponding increase in resilience. Specifically, no significant difference was observed between positively affected or non-ENSO-affected regions under the overall impact of ENSO or La Niña (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 3). Moreover, the resilience decline in positively affected regions under the impact of El Niño was higher than that in non-ENSO-affected regions (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table. 2). This suggests that even in regions where ENSO initially enhances vegetation resilience, long-term instability caused by alternating climate stress events, asymmetry in impact intensity, and lagging effects may contribute to the “pseudo-gain” trap of the positive ENSO effect.

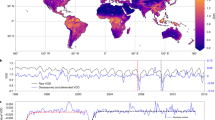

Future global vegetation resilience and its response to future changes in ENSO

Leveraging simulated LAI and climate projections from CMIP6, we evaluated future trajectories of vegetation resilience and examined their links to climate change across three emission scenarios (SSP126, SSP245, and SSP370) (see Methods). Our results indicate that 33-39% of vegetated regions are anticipated to undergo a further decline in resilience across three future climate scenarios, with an average decline trend of 0.12 in these affected areas. Notably, Western Siberia and Northern Europe were identified as emerging areas of declining vegetation resilience in all three scenarios (Fig. 4a). Regarding ENSO teleconnections, projected warming is expected to weaken the synchronization impact of ENSO on vegetation resilience, decreasing from 21.4% under SSP126 to 21.1% under SSP245 and 13.5% under SSP370 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). In parallel, ENSO-driven climate anomalies are projected to strengthen, affecting approximately 51–55% of global vegetation areas and marking a 6-10% increase compared to historical levels (Fig. 4c). These changes in ENSO-resilience patterns highlight newly vulnerable regions. For instance, under three scenarios, extensive regions across Siberia, as well as northern North America under SSP126 and SSP370, are projected to experience adverse impacts from La Niña-associated radiation and temperature anomalies (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 10). These findings underscore the increasing complexity of ENSO-vegetation interactions in the context of climate change and emphasize the urgent need for targeted research and conservation strategies in these newly identified vulnerable regions.

a Resilience trend under SSP 126, SSP 245, and SSP 370, respectively. ENSO impacts on vegetation resilience under the three scenarios, including b atmospheric synchronization effects and c climate-mediated effects transmitted through ENSO-driven anomalies. Plus (+) and minus (−) signs indicate positive and negative impacts, respectively, with numbers indicating impact intensity, calculated as the sum of individual grid-level impacts. Basemap data © Esri; Garmin; GEODIS; GMI; CIA World Factbook.

Discussion

This research provides a comprehensive analysis of the climatic drivers of vegetation resilience, uniquely incorporating the remote impacts of global climate oscillations such as ENSO. Using an RF model, we disentangled the effects of in-situ climate variables (temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation) from those of ENSO and their interactions, revealing how ENSO shapes resilience patterns across global, regional, and biome-specific scales. Projections further indicate evolving impacts of ENSO under future climate scenarios. One key finding is that 53% of global vegetation over the past four decades has been influenced by ENSO, either through synchronization or climate-mediated effects. These impacts are both asymmetric and delayed, with El Niño and La Niña events exerting opposing yet destabilizing effects on vegetation resilience, contributing to long-term declines in resilience, most notably in the Amazon, Southeast Asia, Central Africa, southern North America, and Australia (Fig. 3).

ENSO events exert asymmetric teleconnection effects on vegetation resilience, with El Niño–associated regions exhibiting more pronounced declines (Fig. 2). Specifically, over one-third of vegetated areas experience significant resilience changes during El Niño events, compared to only about 20% during La Niña (Fig. 3). Mechanistically, these effects are primarily mediated by regional climate: ENSO-driven anomalies in temperature, precipitation, and radiation trigger extremes—such as heatwaves, droughts, floods—that can impair photosynthesis, water regulation, and root function40,41, ultimately slow canopy recovery. Our Random Forest analysis confirms that such anomalies, particularly those linked to El Niño (high temperature and radiation, water stress) and La Niña (cold and dry conditions), are significantly associated with resilience decline globally (Fig. 2). Even intact, high-biomass forests are vulnerable: our targeted analysis shows that resilience loss occurs in these systems under ENSO-related stresses (Supplementary Fig. 4), consistent with previous findings that tall canopies and deep-root systems depend heavily on stable water supply and become vulnerable under persistent ENSO pressure42. In addition to climate-mediated effects, ENSO may influence ecosystems through other pathways. For example, ENSO-driven circulation anomalies can intensify savanna burning8 and facilitate long-range smoke transport to adjacent forests43,44, reducing incoming solar radiation and limiting canopy productivity45. ENSO-modulated shifts in commodity prices (for example, palm oil)46,47, may also accelerate tropical deforestation and fragmentation48, further weakening forest resilience. These hypothesized pathways remain speculative and warrant further investigation.

Although ENSO affects vegetation resilience through these synchronization or climate-mediated mechanisms, ecosystem responses vary due to interactions between ENSO’s asymmetric teleconnections, ecosystem traits, and human activities. In particular, tropical forests, tropical savannas, and grasslands experience a higher frequency and intensity of ENSO-induced extreme events, leading to the most pronounced disruptions in ecosystem function and resilience. In addition, our model highlights topographic features—particularly high elevation, steep slopes, and well-drained regions—as key predictors of low resilience and strong ENSO responses (Fig. 2f). These landscapes often support vegetation with shallow roots, limited soil depth, and poor water and nutrient retention, resulting in reduced buffering capacity49. In parallel, climatic seasonality drives divergent vegetation adaptive strategies, which in turn influence regional sensitivity to ENSO. While low-latitude regions with weak seasonality exhibit strong resilience shifts globally (Fig. 2e), ecosystems in areas with high intra-annual precipitation variability—such as northern Asian shrublands, Siberian tundra, eastern Amazon rainforest, and Sahelian grasslands—also show heightened sensitivity compared to adjacent regions with similar rainfall and vegetation types (Fig. 3a). This supports prior findings3,40,50 that stable water availability enhances post-disturbance recovery.

Equally important, anthropogenic disturbances exacerbate these patterns51. Highly fragmented tropical and temperate forests, such as those in the Amazon, Central Africa, and parts of North America and Southeast Asia, exhibit heightened sensitivity to ENSO (Fig. 3a), likely due to intensified edge effects that increase temperatures and reduce humidity, amplifying climate stressors52,53,54. Intensive agriculture drives land degradation, biodiversity loss, and hydrological disruption, further destabilizing adjacent ecosystems55,56. For instance, we found that mixed forests along the Eurasian agro-ecological transition zone show more negative responses to La Niña when located near croplands (Fig. 3a), suggesting that surrounding land use and landscape configuration—such as proximity to agricultural fields—can alter vegetation sensitivity to ENSO.

Our global synthesis extends prior regional evidence by integrating isolated observations into the coherent global assessment of vegetation resilience sensitivity to ENSO. The identified ENSO sensitivity hotspots—such as the southeastern Amazon, Sahelian margins, Southeast Asia, Australia, Central Africa, and Central America—broadly align with earlier studies linking reduced resilience to recurrent droughts, floods, and water limitations2,57,58,59,60,61,62, thereby validating our approach. More importantly, the synthesis reveals that ENSO acts as a synchronizing agent, imposing a common rhythm of resilience loss across climatically unstable ecosystems worldwide. As climate change intensifies, this global perspective becomes critical3. Our findings provide actionable insights for identifying vulnerability hotspots and demonstrate the importance of integrating ENSO forecasts into ecosystem restoration and climate-informed conservation planning, with tropical and subtropical forests prioritized for their biodiversity, carbon storage, and climatic sensitivity. In contrast, some boreal forests, such as mixed forests in Northern Europe, show higher resilience and minimal ENSO sensitivity (Figs. 1a and 3a), indicating that ENSO need not be a central concern in these regions. These insights point toward the need for regionally differentiated strategies.

Despite these insights, uncertainties remain. Data limitations stem from the inconsistencies across climate models, remote sensing products, and SST measurements in characterizing ENSO and LAI. Even using a multi-model ensemble, ENSO projections in most Earth system models (ESMs) are still biased from observations due to uncertain atmospheric feedbacks17,63, and LAI deviations are largely driven by models’ underestimation of seasonal phenology64. Integrating field observations with remote sensing and models is needed to better constrain projections and improve vegetation–ENSO coupling in future studies. Methodologically, critical slowing down (CSD) indicators—such as increasing variance or autocorrelation—provide a theoretical framework for detecting system stability changes without abrupt disturbances37. However, they capture only theoretical resilience shifts rather than actual recovery rates or critical transitions65. Moreover, the application of CSD indicators requires long time series, yet large-scale observational records often combine data from multiple sensors with different processing steps, introducing biases in trends and significance estimates66,67. Noise and non-stationarity can further inflate signals, causing false positives. More conservative significance testing (for example, surrogate time-series methods)68, and cross-validation across multiple datasets and indicators would strengthen the robustness of resilience estimates.

Methods

Historical vegetated and regional climate data

The historical vegetation dynamic was indicated by the long-term leaf area index (LAI) product of the Global Land Surface Satellite (GLASS) V5 dataset, which was generated from Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) satellite data69. The dataset spans 1981–2018, with a temporal resolution of eight days and a spatial resolution of 0.05°70,71. After outlier (LAI > 10 or LAI < 0) removal, the LAI data were aggregated into monthly means. As a critical structural variable, LAI captures key vegetation processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, and transpiration72. Moreover, LAI is more resistant to saturation than Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)72,73 and provides a longer and more consistent temporal record than Vegetation Optical Depth (VOD)74, making it a robust indicator for evaluating vegetation resilience over time. Regional climate data were obtained from the ERA5-land reanalysis dataset, which provides monthly near-surface (2 meters) air temperature (°C), monthly precipitation (m), and monthly surface solar radiation (j/m2). These variables were processed and downloaded via the Google Earth Engine platform, with surface solar radiation converted to W/m². All data were bilinearly aggregated to a 0.5° resolution, as is typically recommended75. ENSO variability was represented by monthly sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTA) in the Niño 3.4 region (5°S – 5°N and 170°W – 120°W), obtained from the NOAA ERSSTV5 dataset76. All variables were analyzed over the period 1981–2018. Historical trajectories of these variables are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

CMIP6 data

To project future changes, we use the simulated climate and vegetation time series from the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6)77, including monthly SST, LAI, near-surface air temperature, precipitation, and surface solar radiation. These projections were generated under the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (SSP 126, SSP 245, SSP 370), covering the period 2015 to 2100. The climate factors (precipitation, temperature, radiation, and SST) and LAI were derived as multi-model averages to mitigate potential model-specific biases and provide a more robust, ensemble-based estimate of future climate projections (the models are listed in Supplementary Tables 4–6). All variables were bilinearly aggregated to a horizontal grid of 1° × 1°.

ENSO variability was represented by the Monthly SSTA averaged over the Niño 3.4 region. Monthly SSTAs in future projected scenarios were constructed by removing the monthly climatology (historical monthly mean), and applying a quadratic detrending to remove the long-term warming trend78,79, then standardizing by dividing by historical monthly SSTA standard deviation63. The projected SSTA trajectories under different scenarios are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

Landcover and terrain data

We used landcover data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) land cover type product (MCD12C1)80. The maps employed the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) classification scheme, provided at yearly intervals with 0.05° resolution. For this study, we assumed that land cover remains unchanged, thus utilizing the map of 2000 (the median time) to represent the global distribution of vegetated land. We used the GLAD Intact Forest Landscapes dataset for the year 200081, which provides a global map of forests without significant disturbance.

Global elevation data in the year 2000 was derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) Version 3 product, which offers a resolution of 30 m82. The slope was calculated based on this elevation data. The Height Above Nearest Drainage (HAND) data, obtained from Google Earth Engine83, were derived from SRTM elevation data and provide a more accurate representation of groundwater accessibility and hydrological buffering capacity84. Finally, all data were aggregated to a spatial resolution of 0.5° and 1°, respectively.

Climate zones data

The Köppen-Geiger World map is used to define the climate zones in our analysis. We aggregate the 31 climate zones into five major zones (tropical, arid, humid temperate, temperate, continental, and polar) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Vegetation resilience calculation

Assessing vegetation resilience generally requires estimating the time needed to return to equilibrium85, but large-scale direct measurement is challenging. Natural systems experience continuous random disturbances86, and external shocks vary in intensity and frequency across regions87, making experimental assessments of recovery rates difficult. However, theoretical studies suggest that a system’s response to disturbances can be predicted through its internal variability37,88. The dynamics of an ecosystem can be modeled using the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process89, using the following equation:

Where \({X}_{t}\) is the system state variable, \(\mu\) is the steady-state mean of the system, \(\theta\) is the recovery rate, \(\sigma\) is the noise intensity, and \(d{W}_{t}\) is the standard Wiener process. Discretizing this process over the time step \(\varDelta t\), the equation is:

If the time step \(\varDelta t\) is small, the terms involving \(\mu\) and the scaling of noise can be approximated, leading to the model yielding the first-order autoregressive process67:

The lag-1 autocorrelation coefficient (\(\alpha\)) can be shown:

The variance (VAR) of the discretized time series can be shown:

These equations indicate that as a system approaches a critical threshold, recovery \(\theta\) slows, leading to an increase in variance and AC. Thus, these metrics are considered to be early warning signals of ecosystem state shifts36.

In this study, lag-1 AC was used as a resilience indicator, and variance was also calculated to verify the robustness of AC. The lag-1 AC was estimated using a first-order autoregressive model fitted via least squares:

Where \({X}_{t}\) is a subset of the LAI time series, \({X}_{t+1}\) is the lag-1 time series, and \(\alpha\) is the AC coefficient. \(\varepsilon\) is the residual error.

The variance was estimated as the average of the squared deviations from the mean:

Where \({X}_{i}\) is the \(ith\) element in the LAI subset, \(\mu\) is the mean of the subset, and \(n\) is the number of elements in the subset.

In this study, the GLASS LAI dataset and CMIP6-derived LAI data under three scenarios were used to calculate historical and future vegetation resilience. However, prior to measuring the resilience metrics, it is necessary to remove the impact of long-term trends of LAI time series. STL (Seasonal-Trend decomposition using LOESS) is a widely used time series decomposition method. It gradually extracts trend and seasonal components through an iterative smoothing process and finally obtains the residual90. We employed STL decomposition through the stl() function in the ‘stats’ package in R for each grid. This method robustly separates the LAI timeseries into three components: a long-term trend, a fixed seasonal cycle trend (by using ‘periodic’ option in s.window parameter), and a residual component91,92. Then, the residual components of the LAI timeseries were utilized to calculate the lag-1 AC and variance. The ar.ols() and var() function in ‘stats’ package in R were employed to calculate the lag-1 autocorrelation and variance on the sliding windows of 5 years. To investigate the effect of window size on the resilience trends, we also calculated AC with a sliding window of 10 years (Supplementary Fig. 12). Note that only the regions where AC > 0 were involved in this study. For the LAI data preprocessing, we did not fill the data gap because the relationship between the AC of the gap-free and gapped time series has been proven to be very close to being one-to-one67. We also excluded the grids of croplands (where human management may strongly disturb the response of crops to ENSO) and non-vegetation types, so that our analysis focuses on the vegetation of non-crop ecosystems.

Vegetation resilience and greenness trend

To assess the historical vegetation resilience trends, we calculated the Kendall tau value for the AC and the variance time series using a 5-year sliding window at each grid from 1981 to 2018. This rank-based correlation coefficient is independent of data distribution, allowing for consistent trend comparisons across regions. Using the cor.test() function with the Kendall method from the R package ‘stats’, we estimated resilience trends with a 95% confidence level. The trend directions of variance and AC were largely consistent across most regions (Fig. 1c). Additionally, we calculated the AC trend using a 10-year window, which indicated a spatial pattern qualitatively similar to that of the 5-year window (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 12). AC trends under future scenarios were also calculated (Fig. 4).

Long-term LAI trend was quantified using Kendall’s tau at p < 0.05 to represent vegetation greenness change (Fig. 1d). We then overlaid the AC and LAI trend maps to assess the spatial coupling between greenness and resilience.

Random forest model

We utilized random forest regression to identify the nonlinear relationship between long-term vegetation resilience dynamics and environmental factors. Random forest regression is a robust machine-learning model that can decouple the interactions and identify key drivers of change93. By integrating spatial features to capture regional differences and time series data to address temporal changes, it effectively analyzes global patterns of vegetation resilience under climate change94. In this research, the response variable was the annual time series of AC, which characterizes vegetation resilience. Predictor variables included a combination of climatic and terrain factors. Climatic predictors consisted of the annual mean near-surface (2 m) air temperature, annual mean of monthly total precipitation, and annual mean of monthly accumulated surface shortwave radiation, as well as the annual ENSO index. The annual ENSO index was represented by the mean sea surface temperature anomaly (SSTA) over the Niño 3.4 region, calculated as the average over December–February (DJF) using the NOAA ERSST v5 dataset to capture the peak phase of ENSO events17. All climatic variables were computed at the pixel level. The regression model incorporated an interaction term between ENSO and climate factors, as well as a lag term. Climate factors from the preceding three years represented the lagged effect, while the interaction terms (temperature × ENSO, precipitation × ENSO, and radiation × ENSO) characterized how resilience sensitivity to climate changes varies with ENSO intensity95,96. DEM, slope, and HAND were included in the model as the terrain predictors to control potential interference with terrain background heterogeneity. In addition, intra-annual variations in temperature and precipitation may influence vegetation resilience by favoring species with distinct adaptive traits. To account for potential differences in resilience due to climatic seasonality, we included multi-year mean seasonality indices (monthly coefficient of variation) of precipitation, radiation, and temperature as covariates in the model. We employed the ‘ranger’ package in R to train the model with 40% of the global vegetated pixels and validated it using another 10% of pixels, both randomly selected after stratified allocation based on vegetation type proportions. The number of decision trees was set as 500, as the model’s performance had reached stability at this level, and the number of splits was determined as the square root of the number of selected predictors. We then plotted partial dependence plots to illustrate the relationships between AC and the predictors and their marginal contribution to the AC trend. To examine whether human activities influence the observed climate–resilience coupling, we used intact forest ecosystems—largely free from direct land-use impacts—as a control group and trained an additional RF model using data exclusively from these areas (Supplementary Fig. 4).

ENSO’s impact on resilience

To map the spatial distribution of ENSO’s synchronization impact on vegetation resilience, we first removed the effects of in-situ climate by fitting, at each grid cell, a multiple linear regression of resilience on precipitation, temperature, and radiation. We then used a Chi-square test, a nonparametric test method suitable for categorical variables97, to examine whether El Niño or La Niña events triggered anomalies in adjusted vegetation resilience. Positive and negative anomalies in vegetation resilience were defined as standardized AC anomalies (Z-scores) exceeding +2 or falling below –2, respectively, corresponding approximately to the upper and lower 5% tails of the distribution. Similarly, the definition of El Niño or La Niña events was defined based on the commonly accepted criterion: a monthly SSTA greater than 1 °C or less than −1 °C98,99. El Niño and La Niña were tested separately. When both were significant for a cell (FDR-adjusted P < 0.05), we labeled the dominant phase as the one showing the stronger association. To analyze the lagged effect, Chi-square coefficients were calculated between the ENSO event time series and AC anomaly time series in a lag of 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months (Supplementary Fig. 6). We also performed a similar analysis for the three scenarios in the future period (2015–2100) (Fig. 4b). This approach helps reveal the spatial imprint of ecosystem responses that are temporally aligned with ENSO rhythms, including delayed effects, beyond what can be explained by in-situ climate variability.

We then assessed the climate-mediated impact of ENSO, representing the portion of ENSO’s influence on resilience that is mediated through in-situ climatic variables (precipitation, temperature, and solar radiation). This was quantified by evaluating how ENSO-driven climate anomalies affected vegetation resilience. Linear regression was used to measure the co-variation between climatic variability and AC dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 7), and Chi-square tests were applied to assess the association between ENSO events and climatic anomalies (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 8). By spatially overlaying these relationships, the impact on resilience was coded as either positive (“1”) or negative (“−1”). For example, if resilience and precipitation were positively correlated, and ENSO events predominantly caused negative precipitation anomalies in the region, the ENSO-precipitation impact on resilience was recorded as “−1”. We summed the climate-mediated effects of key ENSO–climate variables to quantify their overall impact (Fig. 3c–h). This analysis was also conducted for future scenarios (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Statistical significance test of regional AC trend

Similar to the climate-mediated impacts, we also quantified the positive and negative atmospheric synchronization impacts as “+1” and “−1”, respectively, and then summed both synchronization (Fig. 3a) and climate-mediated (Fig. 3h) impacts to derive the total impact. Based on these total impacts, we classified the global vegetated areas into three categories for each ENSO type (El Niño, La Niña, and overall ENSO): (i) ENSO-positively affected regions, where the sum of synchronization and climate-mediated effects is greater than zero; (ii) ENSO-negatively affected regions, where the sum is less than zero; and (iii) no ENSO impact regions, where the sum equals zero. Pairwise comparisons were then conducted between these categories using Student’s t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test11 (Fig. 3b). In each test, 5000 samples were randomly selected from each category, and both tests were repeated 10 times to obtain multiple P-values. If the majority of P-values for a given comparison were significant (P < 0.05), the Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to control for Type I errors (false positives) due to multiple comparisons100,101. Results were considered statistically significant when both the raw and adjusted P-values were below 0.05. The statistical test results are presented in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3.

Data availability

The long-term LAI product used in this study was derived from the GLASS V5 dataset (1981–2018), which was generated from AVHRR and MODIS satellite data (https://www.glass.hku.hk). ENSO variability was represented by monthly SSTA in the Niño 3.4 region, which can be obtained from the NOAA ERSSTV5 dataset (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/month/). Simulated climate and LAI time series data for the period of 2000–2020 in this study are available from CMIP6 outputs (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search). Landcover data were acquired from the MODIS product (MCD12C1) (https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12C1.061). The Intact Forest Landscapes (IFL) dataset for the year 2000 can be acquired from the GLAD Intact Forest Landscapes dataset (https://intactforests.org/data.ifl.html). Elevation data can be derived from the SRTM Version 3 product, with a resolution of 30 meters (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl1v003/). The Height Above Nearest Drainage (HAND) data are available through Google Earth Engine (https://gee-community-catalog.org/projects/hand/). The Köppen-Geiger climate zones map is accessible at (http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/present.htm). The basemap of world continents used in this study was Esri “World Continents” Feature Layer (ArcGIS Online; Item ID: 57c1ade4fa7c4e2384e6a23f2b3bd254)102. The raster data of the global vegetation resilience calculated in this study and source data for Figs. 1–4 have been deposited in Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28874465.

Code availability

The code used for both the modeling and analyses can be found in the following Figshare repository: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28874465.

References

Forzieri, G., Dakos, V., McDowell, N. G., Ramdane, A. & Cescatti, A. Emerging signals of declining forest resilience under climate change. Nature 608, 534–539 (2022).

Ciemer, C. et al. Higher resilience to climatic disturbances in tropical vegetation exposed to more variable rainfall. Nat. Geosci. 12, 174–179 (2019).

Smith, T. & Boers, N. Global vegetation resilience linked to water availability and variability. Nat. Commun. 14, 498 (2023).

Hossain, M. L., Li, J., Lai, Y. & Beierkuhnlein, C. Long-term evidence of differential resistance and resilience of grassland ecosystems to extreme climate events. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195, 734 (2023).

Carré, M. et al. Holocene history of ENSO variance and asymmetry in the eastern tropical Pacific. Science 345, 1045–1048 (2014).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M. et al. A multiscalar global evaluation of the impact of ENSO on droughts. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JD016039 (2011).

Ward, P. J. et al. Strong influence of El Niño Southern Oscillation on flood risk around the world. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 15659–15664 (2014).

Cardil, A. et al. Climate teleconnections modulate global burned area. Nat. Commun. 14, 427 (2023).

Higgins, S. I., Conradi, T. & Muhoko, E. Shifts in vegetation activity of terrestrial ecosystems attributable to climate trends. Nat. Geosci. 16, 147–153 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Increased ENSO sea surface temperature variability under four IPCC emission scenarios. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 228–231 (2022).

Singh, J. et al. Enhanced risk of concurrent regional droughts with increased ENSO variability and warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 163–170 (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Asian-Australian summer monsoons linkage to ENSO strengthened by global warming. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 8 (2023).

Seddon, N. et al. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190120 (2020).

Wang, C. A review of ENSO theories. Natl. Sci. Rev. 5, 813–825 (2018).

Dannenberg, M. P. et al. Large-scale reductions in terrestrial carbon uptake following Central Pacific El Niño. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL092367 (2021).

Lin, A. & Li, T. Energy Spectrum characteristics of boreal summer intraseasonal oscillations: climatology and variations during the ENSO developing and decaying phases. J. Clim. 21, 6304–6320 (2008).

Cai, W. et al. Changing El Niño–Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 628–644 (2021).

Alizadeh, O. A review of ENSO teleconnections at present and under future global warming. WIREs Clim. Change 15, e861 (2024).

Wang, C. & Picaut, J. Understanding ENSO physics—A review. Earth’s. Clim.: Ocean–Atmos. Interact., Geophys. Monogr. 147, 21–48 (2004).

Dudenhöffer, J.-H., Luecke, N. C. & Crawford, K. M. Changes in precipitation patterns can destabilize plant species coexistence via changes in plant–soil feedback. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 546–554 (2022).

Fan, L. et al. Dominant role of the non-forest woody vegetation in the post 2015/16 El Niño tropical carbon recovery. Glob. Change Biol. 30, e17423 (2024).

Anttila-Hughes, J. K., Jina, A. S. & McCord, G. C. ENSO impacts child undernutrition in the global tropics. Nat. Commun. 12, 5785 (2021).

Pavlakis, K. G., Hatzianastassiou, N., Matsoukas, C., Fotiadi, A. & Vardavas, I. ENSO surface shortwave radiation forcing over the tropical Pacific. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 5565–5577 (2008).

Ivory, S. J., Russell, J. & Cohen, A. S. In the hot seat: Insolation, ENSO, and vegetation in the African tropics. J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 118, 1347–1358 (2013).

Timmermann, A. et al. El Niño–Southern Oscillation complexity. Nature 559, 535–545 (2018).

Hoerling, M. P., Kumar, A. & Zhong, M. El Niño, La Niña, and the nonlinearity of their teleconnections. J. Clim. 10, 1769–1786 (1997).

Taschetto, A. S. et al. El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate 309-335, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119548164.ch14 (2020).

Bennett, A. C. et al. Sensitivity of South American tropical forests to an extreme climate anomaly. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 967–974 (2023).

Restrepo-Coupe, N. et al. Asymmetric response of Amazon forest water and energy fluxes to wet and dry hydrological extremes reveals onset of a local drought-induced tipping point. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 6077–6092 (2023).

Gillett, Z. E., Taschetto, A. S., Holgate, C. M. & Santoso, A. Linking ENSO to Synoptic Weather Systems in Eastern Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104814 (2023).

Wigneron, J.-P. et al. Tropical forests did not recover from the strong 2015–2016 El Niño event. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay4603 (2020).

Machado-Silva, F. et al. Drought Resilience Debt Drives NPP Decline in the Amazon Forest. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 35, e2021GB007004 (2021).

Fancourt, M. et al. Background climate conditions regulated the photosynthetic response of Amazon forests to the 2015/2016 El Nino-Southern Oscillation event. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 209 (2022).

Hu, K., Huang, G., Huang, P., Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Intensification of El Niño-induced atmospheric anomalies under greenhouse warming. Nat. Geosci. 14, 377–382 (2021).

Wang, H.-J., Zhang, R.-H., Cole, J. & Chavez, F. El Niño and the related phenomenon Southern Oscillation (ENSO): The largest signal in interannual climate variation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96, 11071–11072 (1999).

Dakos, V., van Nes, E. H., D’Odorico, P. & Scheffer, M. Robustness of variance and autocorrelation as indicators of critical slowing down. Ecology 93, 264–271 (2012).

Scheffer, M., Carpenter, S. R., Dakos, V. & Nes, E. H. v. Generic Indicators of Ecological Resilience: Inferring the Chance of a Critical Transition. Annu. Rev. Ecol., Evol. Syst. 46, 145–167 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Global Greening Major Contributed by Climate Change With More Than Two Times Rate Against the History Period During the 21th Century. Glob. Change Biol. 31, e70126 (2025).

Okumura, Y. M. & Deser, C. Asymmetry in the duration of El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 23, 5826–5843 (2010).

McDowell, N. et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? N. Phytol. 178, 719–739 (2008).

Xiao, L. et al. The dominant influence of terrain and geology on vegetation mortality in response to drought: Exploring resilience and resistance. CATENA 243, 108156 (2024).

Allen, C. D. et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Ecol. Manag. 259, 660–684 (2010).

Ansmann, A. et al. Dust and smoke transport from Africa to South America: Lidar profiling over Cape Verde and the Amazon rainforest. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL037923 (2009).

Holanda, B. A. et al. African biomass burning affects aerosol cycling over the Amazon. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 154 (2023).

Yue, X. & Unger, N. Fire air pollution reduces global terrestrial productivity. Nat. Commun. 9, 5413 (2018).

Ubilava, D. The Role of El Niño Southern Oscillation in Commodity Price Movement and Predictability. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 100, 239–263 (2018).

Callahan, C. W. & Mankin, J. S. Persistent effect of El Niño on global economic growth. Science 380, 1064–1069 (2023).

Villoria, N., Garrett, R., Gollnow, F. & Carlson, K. Leakage does not fully offset soy supply-chain efforts to reduce deforestation in Brazil. Nat. Commun. 13, 5476 (2022).

Cartwright, J. M., Littlefield, C. E., Michalak, J. L., Lawler, J. J. & Dobrowski, S. Z. Topographic, soil, and climate drivers of drought sensitivity in forests and shrublands of the Pacific Northwest, USA. Sci. Rep. 10, 18486 (2020).

Malhi, Y. et al. Exploring the likelihood and mechanism of a climate-change-induced dieback of the Amazon rainforest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 20610–20615 (2009).

Bourgoin, C. et al. Human degradation of tropical moist forests is greater than previously estimated. Nature 631, 570–576 (2024).

Nunes, M. H. et al. Forest fragmentation impacts the seasonality of Amazonian evergreen canopies. Nat. Commun. 13, 917 (2022).

Su, Y. et al. Pervasive but biome-dependent relationship between fragmentation and resilience in forests. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02776-7 (2025).

Albert, J. S. et al. Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon. Science 379, eabo5003 (2023).

Foucher, A. et al. Inexorable land degradation due to agriculture expansion in South American Pampa. Nat. Sustain. 6, 662–670 (2023).

Outhwaite, C. L., McCann, P. & Newbold, T. Agriculture and climate change are reshaping insect biodiversity worldwide. Nature 605, 97–102 (2022).

Seddon, A. W. R., Macias-Fauria, M., Long, P. R., Benz, D. & Willis, K. J. Sensitivity of global terrestrial ecosystems to climate variability. Nature 531, 229–232 (2016).

Flores, B. M. et al. Floodplains as an Achilles’ heel of Amazonian forest resilience. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 4442–4446 (2017).

Buxton, J. E. et al. Quantitatively monitoring the resilience of patterned vegetation in the Sahel. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 571–587 (2022).

Suescún, D. et al. ENSO and rainfall seasonality affect nutrient exchange in tropical mountain forests. Ecohydrology 12, e2056 (2019).

Cai, W., Van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. Teleconnection pathways of ENSO and the IOD and the mechanisms for impacts on Australian rainfall. J. Clim. 24, 3910–3923 (2011).

Rodman, K. C. et al. A changing climate is snuffing out post-fire recovery in montane forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 2039–2051 (2020).

Beobide-Arsuaga, G., Bayr, T., Reintges, A. & Latif, M. Uncertainty of ENSO-amplitude projections in CMIP5 and CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. 56, 3875–3888 (2021).

Park, H. & Jeong, S. Leaf area index in Earth system models: how the key variable of vegetation seasonality works in climate projections. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 034027 (2021).

Boers, N. Observation-based early-warning signals for a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 680–688 (2021).

Smith, T. et al. Reliability of resilience estimation based on multi-instrument time series. Earth Syst. Dynam. 14, 173–183 (2023).

Smith, T. & Boers, N. Reliability of vegetation resilience estimates depends on biomass density. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1799–1808 (2023).

Ben-Yami, M., Skiba, V., Bathiany, S. & Boers, N. Uncertainties in critical slowing down indicators of observation-based fingerprints of the Atlantic Overturning Circulation. Nat. Commun. 14, 8344 (2023).

Liang, S. et al. A long-term Global LAnd Surface Satellite (GLASS) data-set for environmental studies. Int. J. Digit. Earth 6, 5–33 (2013).

Xiao, Z. et al. Long-Time-Series Global Land Surface Satellite Leaf Area Index Product Derived From MODIS and AVHRR Surface Reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 54, 5301–5318 (2016).

Xiao, Z., Liang, S. & Jiang, B. Evaluation of four long time-series global leaf area index products. Agric. Meteorol. 246, 218–230 (2017).

Fang, H., Baret, F., Plummer, S. & Schaepman-Strub, G. An Overview of Global Leaf Area Index (LAI): Methods, Products, Validation, and Applications. Rev. Geophys. 57, 739–799 (2019).

Zeng, Y. et al. Structural complexity biases vegetation greenness measures. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1790–1798 (2023).

Van Passel, J. et al. Critical slowing down of the Amazon forest after increased drought occurrence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2316924121 (2024).

Feng, Y. et al. Reduced resilience of terrestrial ecosystems locally is not reflected on a global scale. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 88 (2021).

Huang, B. et al. NOAA Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature (ERSST), Version 5. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://doi.org/10.7289/V5T72FNM (2017).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Liu, Y., Cai, W., Lin, X., Li, Z. & Zhang, Y. Nonlinear El Niño impacts on the global economy under climate change. Nat. Commun. 14, 5887 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Central-Pacific El Niño-Southern Oscillation less predictable under greenhouse warming. Nat. Commun. 15, 4370 (2024).

Friedl, M. & Sulla-Menashe, D. MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 0.05Deg CMG V061. NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center, https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12C1.061 (2022).

Potapov, P. et al. The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013. Sci. Adv 3, e1600821 (2017).

JPL, N. NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Global 1 arc second. NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center, https://doi.org/10.5067/MEASURES/SRTM/SRTMGL1.003 (2013).

Donchyts, G. et al. Global 30m height above the nearest drainage. Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly (2016).

Chen, S. et al. Amazon forest biogeography predicts resilience and vulnerability to drought. Nature 631, 111–117 (2024).

Runge, K. et al. Monitoring Terrestrial Ecosystem Resilience Using Earth Observation Data: Identifying Consensus and Limitations Across Metrics. Glob. Change Biol. 31, e70115 (2025).

Scheffer, M. et al. Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature 461, 53–59 (2009).

Smith, T., Traxl, D. & Boers, N. Empirical evidence for recent global shifts in vegetation resilience. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 477–484 (2022).

Marconi, U. M. B., Puglisi, A., Rondoni, L. & Vulpiani, A. Fluctuation–dissipation: Response theory in statistical physics. Phys. Rep. 461, 111–195 (2008).

Bartoszek, K., Glémin, S., Kaj, I. & Lascoux, M. Using the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process to model the evolution of interacting populations. J. Theor. Biol. 429, 35–45 (2017).

RB, C. STL: A seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on loess. J. Stat. 6, 3–73 (1990).

Boulton, C. A., Lenton, T. M. & Boers, N. Pronounced loss of Amazon rainforest resilience since the early 2000s. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 271–278 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Vegetation resilience does not increase consistently with greening in China’s Loess Plateau. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 336 (2023).

Delavaux, C. S. et al. Native diversity buffers against severity of non-native tree invasions. Nature 621, 773–781 (2023).

Liu, M., Trugman, A. T., Peñuelas, J. & Anderegg, W. R. L. Climate-driven disturbances amplify forest drought sensitivity. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 746–752 (2024).

Jaccard, J. & Turrisi, R. Interaction effects in multiple regression. (Sage, 2003).

Balli, H. O. & Sørensen, B. E. Interaction effects in econometrics. Empir. Econ. 45, 583–603 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. Eastern-Pacific and Central-Pacific Types of ENSO Elicit Diverse Responses of Vegetation in the West Pacific Region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096666 (2022).

Geng, X., Kug, J.-S. & Kosaka, Y. Future changes in the wintertime ENSO-NAO teleconnection under greenhouse warming. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 81 (2024).

Iizumi, T. et al. Impacts of El Niño Southern Oscillation on the global yields of major crops. Nat. Commun. 5, 3712 (2014).

Pike, N. Using false discovery rates for multiple comparisons in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 278–282 (2011).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. On the adaptive control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing with independent statistics. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 25, 60–83 (2000).

Esri. “World Continents” [basemap]. Scale Not Given. ArcGIS Online. 2020. https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=57c1ade4fa7c4e2384e6a23f2b3bd254. (15 June 2024).

Acknowledgements

This study is financially supported by the National Key R&D Plan of China (2024YFF1306600) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42377321).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. conceived the study and designed the study methodology. W.Z. and Z.D. collected the data, W.Z. and J.W. did the data analysis and visualization, and drafted the manuscript. Z.W., C. Li, H.Z., and L.C. Stringer reviewed and edited the manuscript. Z.W. supervised all the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Matheus Nunes and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, W., Li, C., Zhang, H. et al. ENSO amplifies global vegetation resilience variability in a changing climate. Nat Commun 17, 267 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66987-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66987-z