Abstract

S-type anion channel homologs (SLAH) are widely expressed in various plant tissues and play a key role in anion transport, which is crucial for plant adaptation to both biotic and abiotic stresses. In this study, we employ cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to analyze four SLAH channel complexes from Arabidopsis thaliana: the homotrimeric SLAH3 channel, the 2SLAH1 + SLAH3+tRNA complex, the 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complex, and the 3SLAH1+tRNA complex. Critically, our studies reveal that tRNA directly binds to and occupies the intracellular entrance of the SLAH1 homotrimer and the 2SLAH1 + SLAH3 heterocomplex. Electrophysiological experiments confirm tRNA’s role as a potent inhibitory regulatory subunit: RNase-mediated tRNA degradation robustly activates SLAH1 currents, while targeted mutagenesis of SLAH1 tRNA-interacting residues phenocopy this activation and enhanced ABA-induced stomatal closure. Combining with structural biology, electrophysiology, and biochemistry, we comprehensively examine the key residues in SLAH1 and SLAH3 that are responsible for the anion permeation. This mechanistic advancement provides a deeper understanding of the molecular basis for plant stress tolerance and identifies specific molecular targets for future engineering crops.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants face diverse biotic and abiotic stresses. Biotic stress includes biological factors like infections, diseases, or pests that impair growth1,2,3, whereas abiotic stress involves environmental conditions such as salinity, drought, high temperatures, UV radiation, or nutrient deficiencies4. Investigating plant responses and regulatory pathways under stress is crucial for improving resilience and crop yield5. Guard cells and stomata, essential for gas exchange, photosynthesis, transpiration, and immunity6,7, also impact global carbon and water cycles, playing a critical role in enhancing crop productivity and water-use efficiency8,9. Electrophysiological studies have identified two types of membrane anion channels in guard cells10,11,12,13: R-type (rapid-type) and S-type (slow-type). R-type14,15, also known as quick-activating anion channel, mediates rapid currents16 and is activated by depolarization, inactivating with hyperpolarization. S-type channels, including the SLAC/SLAH family, activate more slowly11,12 and regulate stomatal opening via anionic efflux11,12.

The Arabidopsis genome encodes five SLAC/SLAH members: SLAC1, SLAH1, SLAH2, SLAH3, and SLAH417,18. Among these, SLAC1 has been the most extensively researched19,20,21,22,23,24, focusing on its structure, function, and regulatory mechanisms. SLAC1 primarily mediates the efflux of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and Cl−, with a stronger preference for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\). Since the discovery of anion currents in plants and the functional characterization of SLAC1 from the SLAC/SLAH family, additional SLAH channel proteins have been identified17,18. SLAH3 is broadly expressed in roots, guard cells, mesophyll cells, pollen tubes, stems, hypocotyls, and nectar glands25,26,27,28,29,30. SLAH3 shows permeability to both \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and Cl−, though Cl− permeability is relatively lower, with a \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\):Cl− permeability ratio of 20:128,29,31,32. SLAH3 activation requires kinase activity and increased extracellular \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) concentrations. Functional studies reveal SLAH3’s involvement in regulating stomatal movements29, balancing nitrogen and potassium33, sensing acid toxicity in root cells34, facilitating the transport of Cl− from roots to shoots35, influencing pollen tube growth36, and reducing ammonium toxicity in roots26.

While research on SLAC1 and SLAH3 is thorough, fewer studies address SLAH1 and SLAH217,18, and SLAH4 remains largely unexplored17,18. Currently, only the three-dimensional structure of SLAC1 has been resolved23,37, while the structural and functional details of other members are still unknown. In this work, we employ cryo-EM to analyze the structures of the SLAH3 homotrimer, SLAH1-tRNA complex, and the heteromeric complexes of 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3+tRNA and 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3. We identify tRNA molecules that inhibit SLAH1 channel activity, validate kinase-mediated regulation of SLAH proteins, and elucidate how different SLAH protein combinations control anion transport through electrophysiological assays. These findings enhance our understanding of plant stress resistance mechanisms and contribute valuable knowledge for advancing agricultural development.

Results

Structural determination of the AtSLAH3 channel

To explore the molecular mechanism of SLAH family-mediated anion transport, we transfected Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells with a GFP-tagged AtSLAH3 plasmid and a plant protein kinase CPK21 plasmid. With the increase in the clamped voltage, AtSLAH3 generated substantial currents (Fig. 1a), findings consistent with the previous study29 that SLAH3 mediates S-type anion currents when co-expressed with CPK21 in Xenopus oocytes. To delve deeper into the underlying anion transport mechanism of AtSLAH3, we overexpressed and purified the AtSLAH3 protein in HEK293F cells and resolved its structure at 2.63 Å using cryo-EM (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2). The map reconstructed using single-particle cryo-EM revealed clear structural details for the transmembrane region, extracellular loops, and most intracellular loops, except for the loop between TM8 and TM9, which might be due to its flexibility (Fig. 1c, d and Extended Data Fig. 2). Like AtSLAC1, AtSLAH3 forms a trimer, with each monomer consisting of 10 transmembrane helices. TM1, TM3, TM5, TM7, and TM9 are arranged in a pentagonal structure, critical for substrate transport. TM2, TM4, TM6, TM8, and TM10 create the outer layer, with longer helices at greater inclinations. Each monomer also contains two additional cytosol helix (CH) domains (CH1 and CH2), which may contribute to channel gating.

a Representative whole-cell current traces and I/C-V curves of untransfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (n = 3) and CHO cells overexpressing WT AtSLAH3-EGFP with CPK21 (n = 5). Cells were held at −30 mV and subjected to voltage steps from −100 mV to +100 mV (20 mV increments, 800 ms duration). Data were represented as means ± SEM. b Cryo-EM map of the homotrimeric SLAH3 complex, with each protomer shown in distinct colors, viewed from TM region. c Ribbon model of the AtSLAH3 complex, with each protomer shown in distinct colors, showing transmembrane views. d Ribbon model of an individual SLAH3 protomer viewed from the cytosolic side, with each transmembrane helix labeled. e Channel translocation pathway calculated using HOLE software70, with key residues highlighted. f The interactions between the N-termini, C-termini, and TM regions of SLAH3 inhibits the channel pore (left). The magnified view of the interactions (right) shows different domains color-coded: N-termini (blue) and C-termini (red). g Bar graph comparing whole-cell current densities of SLAH3 and mutant channels expressed in CHO cells. Data were represented as means ± SEM, and p-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (a) and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (g). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The channel narrows on the extracellular side and widens intracellularly. A “plug”-like structure composed of the N- and C-termini, along with CH1 and CH2, blocks the channel in its inactive state (Fig. 1c, d). We further analyzed the ion conduction pathway and identified four key residues involved in transport: F346, V403, F517, and F336 (Fig. 1e). Sequence alignment between AtSLAH3 and AtSLAC1 revealed high similarity, particularly in elongated N- and C-termini (Extended Data Fig. 3). The structural comparison showed that these key residues correspond to F276, V336, F450, and F266 in AtSLAC1 (Extended Data Fig. 4). Their arrangement is consistent in both channels. Notably, F517 (F450 in AtSLAC1) is the only fully conserved residue across the SLAC/SLAH family, located centrally in the pore and playing a pivotal role in gating (Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4). This suggests that AtSLAH3 and AtSLAC1 might share similar ion transport mechanisms, driven by these key residues. To gain deeper insights into the functional roles of these amino acids in the SLAH3 channel, we systematically introduced alanine substitutions at a total of 10 residues located within the N-termini, C-termini, CH-domains, and loop regions connecting the transmembrane domains (Fig. 1f). Current measurements of the mutants revealed that the N-terminal mutations Y227A, E234A, E236A, and R257A significantly enhanced the anion currents. Additionally, the R333A mutation on the lateral side of the TM3 helix and the Y515A mutation on the lateral side of the TM9 helix also increased the currents (Fig. 1g). These results further confirm that disrupting both the intracellular plug of SLAH3 and the interactions within its transmembrane region can partially activate SLAH3 channel activity.

Biochemical characterization and structural determination of the AtSLAH3-SLAH1 heterocomplex

A previous study35 showed that SLAH1 and SLAH3 are co-expressed in xylem parenchyma cells, and their interaction was further suggested when co-expressed in oocytes. To verify whether SLAH1 and SLAH3 co-localize in planta, we transiently co-expressed SLAH1-GFP and SLAH3-mCherry in Arabidopsis protoplasts and performed fluorescence co-localization analysis. The analysis revealed that SLAH1 and SLAH3 exhibited co-localization at the membrane (Fig. 2a), findings consistent with the previous study35. To verify the interaction between SLAH1 and SLAH3, we performed pull-down assays with tagged versions of SLAH1 and SLAH3 (Strep tag and Flag tag) (Fig. 2b). We confirmed the interaction between SLAH1 and SLAH3 by co-expressing and purifying them with different tags, demonstrating that SLAH1 and SLAH3 can form heterodimeric channel complexes in vitro. Expression tests confirmed that SLAH1 is more highly expressed than SLAH3 in vitro (Fig. 2b). To further investigate, we overexpressed SLAH3 (Strep-tagged) and SLAH1 (without tag), followed by affinity purification and cryo-EM analysis. Two distinct conformations of the complex emerged from subsequent 3D classification. Finally, we obtained a 3.03 Å heterocomplex for conformation 1 and a 3.18 Å heterocomplex for conformations 2 (Extended Data Fig. 5). These high-resolution maps enabled us to confirm that the conformation 1 heterocomplex contains 2 SLAH1 and 1 SLAH3, whereas the conformation 2 heterocomplex contains 1 SLAH1 and 2 SLAH3.

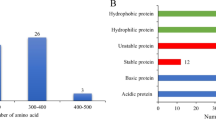

a Co-expressed fluorescently tagged AtSLAH1 and AtSLAH3 colocalized in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Confocal images were collected from cells at 16 h after transfection. Scale bars, 10 μm. Each experiment was repeated independently for three times with similar results; b In vitro pull-down assays confirmed that SLAH1 and SLAH3 can form hetero-oligomers using different tagged versions; Each experiment was repeated independently for three times with similar results; c Electrophoretic nucleic acid identification with the right lanes showing nucleic acid digestion by DNase and RNase; Each experiment was repeated independently for three times with similar results; d RNA sequencing revealed the abundance of distinct RNA types, with tRNA accounting for 87.45% of the total RNA population. e RNA sequencing revealed distinct abundance profiles across RNA species of varying lengths, with 75-nt tRNA constituting the predominant fraction; f Displaying sequencing results of the 75-nt tRNA, with the X-axis depicting different types of tRNA and the Y-axis representing abundance values of each tRNA; g Three-dimensional structural topology of tRNA-His-GTG-1-1.

tRNA binding on the SLAH3-SLAH1 heterocomplexes

Interestingly, in the cryo-EM map of the 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3 complex, we identified an additional density shaped like an inverted “L” (Extended Data Fig. 5). This region did not correspond to unmodeled domains of SLAH1 or SLAH3 and was absent in both the 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 and SLAH3 trimer complexes. This density, containing a double-helical structure, suggested the presence of nucleic acids. To identify the type of nucleic acid, we performed phenol-chloroform extraction on the proteins purified via affinity chromatography, followed by nucleic acid electrophoresis (Fig. 2c). The results showed nucleic acid fragments between 50 bp and 100 bp. DNase treatment did not affect the bands, while RNase treatment eliminated them, confirming that the nucleic acids isolated from the SLAH1/SLAH3 complex are RNA (Fig. 2c). Further RNA sequencing revealed that 87.45% of the nucleic acids were tRNA (Fig. 2d). These tRNAs were approximately 75 nucleotides long (Fig. 2e), consistent with our gel results. Sequencing data identified that tRNA-His-GTG-1-1 is the predominant type of tRNA, responsible for histidine transport within the cell (Fig. 2f). Hence, we incorporate this representative tRNA model into our heterocomplex (Fig. 2g).

In the 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3 + tRNA complex, tRNA binds asymmetrically, forming two contact interfaces between SLAH1 and SLAH3 (Fig. 3a). Hydrophobic interactions between their transmembrane regions primarily sustain these interfaces. At interface 1, near the anticodon loop of tRNA, R287 from TM1 of SLAH1 interacts with the carbonyl oxygen of SLAH3. TM1 of SLAH1 also forms extensive hydrophobic contacts with TM3 and TM5 of SLAH3, stabilizing this interface (Fig. 3b). At interface 2, closer to the T loop of tRNA, interactions mainly involve hydrophobic contacts between TM3 of SLAH3 and TM4 and TM5 of SLAH1. Additionally, Y440 and Q441 from the intracellular loop of SLAH3 interact hydrophobically with Y167 and T174 of SLAH1. In the 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complex without tRNA (Fig. 3c), similar polar and hydrophobic interactions stabilize the heterotrimer. Due to the heterotrimeric nature of the complex, two distinct interfaces (designated Interface 3 and Interface 4) are formed between SLAH1 and SLAH3. Interface 3 is supported by polar interactions involving R287 and Y319 from SLAH1 with K377 and E419. At interface 4, R499, Y480, K483, and Y529 form polar interactions with I164 and E207 (Fig. 3d).

a Cryo-EM map and ribbon model of the 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3+tRNA complex, with SLAH1 in blue, SLAH3 in purple, and tRNA in yellow. b Hydrophobic and polar interactions within the 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3 + tRNA complex, highlighting the regions near the 5′ and 3′ ends of the tRNA with interface 1 and interface 2 noted. c Cryo-EM map and stick model of the 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complex, showing transmembrane and intracellular views. d Hydrophobic and polar interactions within the 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complex, similarly depicted with interface 3 and interface 4 noted.

tRNA binds on the SLAH1 to inhibit channel function

Our aforementioned studies suggested that tRNA primarily binds between two SLAH1 monomers but is absent in SLAH3 homomeric complexes and the 2SLAH3 + 1SLAH1 heteromeric complex. We speculate that tRNA preferentially interacts with SLAH1. To validate this, we overexpressed and purified SLAH1 and determined its 3D structure via cryo-EM. We observed tRNA binding in the SLAH1 homotrimer (Fig. 4a, b and Extended Data Fig. 6). Pore radius analysis of AtSLAH1 reveals the existence of three-layer constriction sites that maintain the AtSLAH1 in a closed state. The first layer, formed by L133, S54, and F311, functions as the gate-controlled hydrophobic layer. F307, located in the middle section of the channel and conserved among the SLAH family, constitutes the second layer. Of additional importance at the third layer, Y123 interacts with R47, constituting the narrowest region of SLAH1 together with I244 (Fig. 4c, d). Notably, R47 and Y123 are conserved only in the SLAH1/4 branch, whereas a glycine residue and a phenylalanine occupy the corresponding positions in SLAH2, SLAH3, and SLAC1, respectively (Fig. 4d).

a Cryo-EM map of the homotrimeric SLAH1-tRNA complex, with each protomer in a different color and tRNA in red; b Ribbon model of the AtSLAH1-tRNA complex, showing both transmembrane and intracellular views; c Ribbon model of a SLAH3 protomer viewed from the cytosol, with labeled transmembrane helices; d SLAH1 channel translocation pathway, calculated using HOLE software, with key residues indicated. e Whole-cell current traces, I/C-V curves, and bar graph summary of CHO cells expressing SLAH1 (n = 5) or SLAH1 + OST1 (n = 5). Pipette solution containing 10 mM RNase A induced whole-cell currents significantly higher than background levels (n = 5). Data were represented as means ± SEM, and p-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (e, middle) and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (e, right). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Unlike SLAH3, SLAH1 lacks sufficient termini to form a “plug” below the transmembrane region, allowing tRNA to occupy the channel aperture, maintaining the channel in an inactive state (Extended Data Fig. 7). Electrophysiological recordings of SLAH1 on CHO cells revealed no significant currents, even with increased depolarized voltage and/or co-expressed with OST1 kinase (Fig. 4e). We assumed that the binding of tRNA might exert a regulatory role for the function of SLAH1. As expected, with the adding of 10 mM RNase A in the pipette solution, presumed to degrade tRNA to further decrease the binding extent of tRNA on SLAH1, we observed robust currents of SLAH1 (Fig. 4e). These results suggested that tRNA blocks the channel aperture, and its removal by RNase A activates the activity of channel, underscoring the inhibitory role of tRNA.

Electrostatic analysis of the SLAH1 homotrimer indicates a strong positive charge in the intracellular region, facilitating interactions with negatively charged tRNA (Fig. 5a, b). Since tRNA spans two SLAH1 monomers, only one tRNA binds in both homomeric (3SLAH1) and heteromeric (2SLAH1 + SLAH3) complexes. Hydrogen bonds between tRNA’s phosphate diester groups and lysine/arginine residues in the SLAH1 channel—K175, R176, K240, R242, K293, K296, R297, R356—ensure stable binding and block ion transport (Fig. 5c). Among these, only R176 exhibits high homology within the SLAH/SLAC family, whereas the other positively charged residues are exclusive to the SLAH1/SLAH4 branch (Extended Data Fig. 4). To validate the inhibitory effect of tRNA on SLAH channels, we generated alanine substitutions at eight positively charged lysine (K) and arginine (R) residues (K/R mutant) within the SLAH1-tRNA interaction interface, as identified in the structural model. First, electrophysiological measurements in CHO cells revealed that this SLAH1(K/R mutant) significantly enhanced SLAH1 anion currents without requiring exogenous RNase treatment (Fig. 5d). Subsequently, validation in Arabidopsis protoplasts demonstrated that, phenocopying the CHO cell results, the SLAH1(K/R mutant) attenuated the tRNA-mediated suppression of SLAH1 channel activity (Fig. 5e).

a Model and representative density map of tRNA; b The intracellular region of SLAH1, exhibiting strong positive electric potential, binds to negatively charged tRNA. In contrast, the top view of SLAH1 displays a strong negative charge; c Hydrogen bond interactions between tRNA and the highly charged K and R residues in the intracellular area maintain the structural stability of tRNA; d Representative whole-cell current traces and I/C-V curves of CHO cells overexpressing SLAH1 + OST1 (n = 5) or SLAH1(K/R mutant)+OST1 (n = 11). Data were represented as means ± SEM. e Representative whole-cell current traces and I/C-V curves of Arabidopsis protoplast overexpressing SLAH1 + OST1 (n = 3) or SLAH1(K/R mutant)+OST1 (n = 5). Data were represented as means ± SEM. f Overexpression of Arabidopsis mutant AtSLAH1(K/R mutant) enhanced ABA-induced stomatal closure more than AtSLAH1 in Nb leaves. Data are means ± SD (n = 50), and p-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (d) and two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (e). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Scale bars, 5 μm.

To further investigate the role of tRNA binding in SLAH1 during stomatal closure, we transiently expressed AtSLAH1, AtSLAH1(K/R mutant), AtSLAH3, and an empty vector control (EV) in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana (Nb) and assessed their responses to ABA-induced stomatal closure. AtSLAH1-expressing leaves exhibited a degree of ABA-induced stomatal closure similar to the EV control (Fig. 5f). In contrast, leaves expressing the AtSLAH1(K/R mutant) showed enhanced ABA-induced stomatal closure, comparable to leaves expressing AtSLAH3 (Fig. 5f). These findings indicate that, unlike wild-type AtSLAH1, the AtSLAH1(K/R mutant) activates SLAH1 channel function, likely due to the disruption of tRNA-mediated inhibition.

Structural comparison between the four SLAH homo and hetero complex

In total, we resolved four complexes: SLAH1-tRNA, 2SLAH1 + SLAH3 + tRNA, SLAH1 + 2SLAH3, and 3SLAH3 (Extended Data Fig. 8). Structural comparison of the 3SLAH1+tRNA and 2SLAH1 + SLAH3 + tRNA complexes revealed that tRNA resides between two SLAH1 monomers in both, indicating that the binding of tRNA requires at least two SLAH1 monomers in the complex. However, spatial displacement of the bound tRNAs occurs due to complex composition differences. Specifically, in transitioning from the 3SLAH1 to the 2SLAH1 + SLAH3 complex, the SLAH1 monomer near the 5′ and 3′ end of tRNA shifts clockwise, particularly in the outer helix (Extended Data Fig. 8a). No major conformational changes occurred in the other SLAH1 monomer present in both complexes. In addition, the 3SLAH3 and 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complexes showed minimal conformational changes in their SLAH3 proteins (Extended Data Fig. 8b).

In the four SLAH transporter complex structures we resolved, the asymmetric binding of tRNA and the structural differences between the SLAH1 and SLAH3 monomers result in the present structures theoretically containing six distinct SLAH1 monomer (designated as SLAH1-1′ to SLAH1-6′) and four distinct SLAH3 monomer (designated as SLAH3-1′ to SLAH3-4′) (Extended Data Fig. 9a). Pore size analysis of the individual SLAH1 and SLAH3 monomers reveals that all monomers adopt a closed conformation with the narrowest constriction site below 1 Å (Extended Data Fig. 9b, d, e, and g), which likely represents the lowest-energy state of SLAH family proteins in the absence of external stimuli. While minor conformational variations are observed among the key pore-lining residues across different SLAH1 and SLAH3 monomers (Extended Data Fig. 9c and f), all structures consistently correspond to the closed state.

Ion permeation of the SLAH family

Previous studies have shown that SLAH1 cooperates with SLAH3 to regulate the anion transportation from root to shoot35, of which the molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Akin to previous study, SLAH3 exhibits a marked anion (Cl−) preference, which was demonstrated by a positively shifted reversal potentials (Erev) when the decrease of Cl− rather than Na+ concentration in bath solution (Fig. 6a). For SLAH1, even with the adding of 10 mM intracellular RNase A, we could only obtain very small currents in the NaCl solution that was set to assess the ion selectivity (Fig. 6b). The small currents made us impossible to assess the anion preference directly, as the influence of background currents of blank cell became non-ignorable at this condition. However, the comparison of Erev at 0 and 10 min showed that along with the activation of SLAH1, the Erev was significantly right shifted, indicating an increase of anion preference that might be mediated by the activation of SLAH1 (Fig. 6c). These findings suggest that both SLAH1 and SLAH3 facilitate anion transport.

a Reversal potential (Erev) shifts of SLAH3 under different bath conditions: high NaCl (blue) (n = 4), low NaCl (red) (n = 5), and low Na+ (green) (n = 5). Data were represented as means ± SEM. b Representative whole-cell current traces and I–V curves recorded at 0 min and 10 min from blank CHO cells (n = 6) and CHO cells transfected with SLAH1 + OST1 (n = 12). Pipette solution contained 10 mM RNase A. c Bar graph showing the shift in SLAH1 reversal potential between 0 min and 10 min (ΔErev) induced by 10 mM RNase A included in the pipette solution (n = 12), and blank CHO cells (n = 6). Data were represented as means ± SEM, and p-values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired t-test. **p < 0.01 (SLAH1 compared with Blank cell). Data were represented as means ± SEM. d Whole-cell current traces, I/C-V curves, and bar graph summary of CHO cells expressing WT SLAH1 (n = 4), R47A (n = 4), or R198A mutants (n = 5). Data were represented as means ± SEM. P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (d, middle). ***p < 0.001 (R47A compared with SLAH1); ###p < 0.001 (R198A compared with SLAH1). P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (d, right). **p < 0.01 (R47A and R198A compared with SLAH1).

We next sought to explore the molecular basis of how SLAH1 and SLAH3 control the transport ratio of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\)/Cl−. An almost equimolar nitrate-to-chloride solutions (pipette/bath: 140 mM Cl−/135 mM \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) were set to assess the relative nitrate-to-chloride of SLAHs. When SLAH3 channels were expressed alone, a reversal voltage of approximately −32 mV was observed, suggesting that SLAH3 channels have notably greater permeability to \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) than to Cl− (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Mutation of key hydrophobic phenylalanine residues in the permeation pathway (F336A, F346A, F517A) did not significantly alter SLAH3 nitrate ion selectivity (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Similarly, when we expressed the SLAH1 channel protein alone, the Erev was only very slightly shifted (−7 ± 2 mV), demonstrating a comparable permeability to \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) and Cl− (Extended Data Fig. 10b, c). Mutagenesis at the key hydrophobic phenylalanine residues (F307A and F311A) or the lower constriction site (Y123A) also didn’t significantly alter nitrate-to-chloride permeation of SLAH1 (Extended Data Fig. 10b, c).

However, the R47A and R198A mutations dramatically reduced whole-cell SLAH1 currents to near-background levels, indicating that residues R47 and R198 are critical for anion permeation through the channel (Extended Data Fig. 11). Notably, R47 and R198 are positively charged amino acids whose side chains project into the permeation pathway. These residues are highly conserved within the SLAH1/SLAH4 clade but are absent in other SLAH family members (Extended Data Fig. 3). R47 is positioned at the lower end and R198 at the upper part of the transmembrane region. The presence of these positive charges on opposite sides of the membrane influences anion recruitment and transport function, underlying the differences in anion permeability among SLAH family proteins.

Dynamic interactions within SLAH homo and hetero complex in planta

To further validate and investigate its potential dynamics interactions between SLAH1 and SLAH3 in planta, we employed Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) to assess their interactions under ABA treatment (Fig. 7). In Nicotiana benthamiana (Nb) leaves transiently co-expressing AtSLAH1-cYFP and AtSLAH3-nYFP, weak BiFC signal was detected under mock conditions. However, the interaction intensity increased after 3 h of ABA treatment, and subsequently diminished after 6 h of ABA exposure. This dynamic pattern confirmed their intrinsic interactions within SLAH1 and SLAH3 and suggests ABA-induced changes in the hetero complex formation.

Confocal images of Nb leaves treated with mock, ABA (3 h), ABA (6 h), or water (6 h) after ABA (6 h). BiFC assay showed the interaction between AtSLAH1-cYFP and AtSLAH3-nYFP, AtSLAH1-cYFP and AtSLAH1-nYFP with co-expression of AtSLAH3, AtSLAH3-cYFP, and AtSLAH3-nYFP with co-expression of AtSLAH1. AtSLAH1-cYFP and AtCNGC1-nYFP, AtSLAH3-cYFP and AtCNGC1-nYFP were used as negative controls. Scale bars, 20 μm. Each experiment was repeated independently for three times with similar results.

To model the condition where both SLAH1 and SLAH3 are present, we consistently co-expressed both channels in subsequent experiments (Fig. 7 and Extended Data Fig. 12). When SLAH1 was co-expressed with AtSLAH3-cYFP and AtSLAH3-nYFP in Nb, the homomeric interaction of SLAH3 showed a tendency to strengthen with ABA treatment. Conversely, when SLAH3 was co-expressed with AtSLAH1-cYFP and AtSHAH1-nYFP, the homomeric interaction of SLAH1 exhibited a weakening trend upon ABA application. Following the wash-out of the ABA stress signal, the signal intensity of the SLAH1 homomeric complex recovered. These findings suggest that the assembly of SLAH channels in an overexpression system in planta is a dynamic process. Over the course of ABA induction, the SLAH channel complex appears to transition from SLAH1 homomers, to SLAH1-SLAH3 hetero complex, and finally to SLAH3 homomers. This dynamic shift in heteromeric complex assembly likely represents an adaptive response mechanism enabling plants to adjust to changing environmental conditions.

Discussion

Chloride and nitrate ions are vital for plant growth, with specific ion transporters and channels regulating their uptake and utilization38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Both an excess and a deficit of these ions can harm plant health, making the maintenance of optimal ion concentrations critical. Based on our structural and electrophysiological models, we propose the precise regulatory mechanisms of the SLAH protein family on anions in the root xylem vessels (Extended Data Fig. 13). Under normal physiological conditions, SLAH1 is highly expressed and predominantly forms SLAH1-SLAH3 heterocomplexes in root xylem parenchyma cells. This complex configuration facilitates Cl− efflux, enabling efficient root-to-shoot Cl− translocation. This process supports optimal growth, increasing fresh weight and biomass. Upon abiotic stress (e.g., drought, salinity), the ABA signaling pathway is activated. Recent studies46,47,48,49,50 indicate stress triggers accumulation of free amino acids via enhanced synthesis. This metabolic shift leads to a corresponding increase in tRNA abundance within the cell. The elevated tRNA pool provides ligands for specific binding to SLAH1. As revealed by our structural and mutagenesis data, tRNA binds via hydrogen bonds to key positively charged residues (Lys/Arg) within the intracellular vestibule of SLAH1. This binding stabilizes SLAH1 in a closed conformation, physically occluding the ion conduction pathway and preventing anion efflux. Crucially, this inhibition likely overrides activation by kinases like OST1 (Fig. 4e), effectively locking the channel closed. Concomitantly, ABA signaling downregulates SLAH1 expression35. The combination of SLAH1 inhibition by tRNA and reduced SLAH1 protein levels shifts the equilibrium towards the formation of SLAH3 homotrimers. SLAH3, activated by stress-induced signals (e.g., cytosolic acidosis, kinases), mediates robust NO₃− efflux. This anion flux is critical for driving stomatal closure, reducing transpirational water loss, and enhancing plant survival under stress. The model proposed based on our structural data and the N. benthamiana overexpression system necessitates further testing at the endogenous level in Arabidopsis, as the low native expression levels and the regulation by relevant signaling factors need to be considered.

The SLAH/SLAC protein family displays structural homology; however, notable differences exist in their selectivity for anions, which is primarily influenced by the precise spatial arrangement of amino acids along the ion permeation pathway. SLAC1 and SLAH3 channels are structurally homologous, both being gated by phenyl groups in the transmembrane region, such as F517 in SLAH3 and F450 in SLAC1, resulting in a permeation pathway that is tight in the middle and gradually open at both ends. In contrast, SLAH1 features not only the conserved phenylalanine gating site but also narrower gating sites on either side, including the F311 position on the upper side of the transmembrane region and the R47-Y123 interaction site at the lower end. This arrangement creates a pocket-like structure that is tight at both ends and relatively wide in the middle.

A previous study34 established SLAH3 as a sophisticated molecular switch that directly senses cytosolic acidosis through two specific histidine residues (H330 and H454), triggering a unique activation mechanism involving the dissociation of the inactive multimer into active monomers (Extended Data Fig. 14a). Critically, this acidification-dependent activation operates independently of kinase phosphorylation pathways. Structural analyses reveal that both H330 and H454 reside within intracellular loop regions. H454, located intracellularly to TM7, forms an interaction network with E234 in the N-terminus and Y515 in TM9, while H330, within the CH2 domain, engages in a cation-π interaction with R333 in TM3 (Extended Data Fig. 14b, c). Our prior mutational studies established the functional importance of residues E234, E236, R333, and Y515, as substitutions at these sites enhance SLAH3 channel activity in the presence of kinases. Under low pH conditions, these histidine residues likely serve as primary proton sensors. Protonation of their imidazole rings is expected to induce conformational changes through the formation of hydrogen bonds and charge interactions with neighboring acidic residues, such as glutamate. This mechanism, wherein histidine protonation remodels the polar interaction network, is well documented for proton sensing in proteins like GPR451. To conclusively elucidate the molecular basis of acidification-induced SLAH3 activation, determination of the three-dimensional structure of SLAH3 under acidic conditions is essential.

Our current research on the SLAH1 and SLAH3 complexes raises the question of whether other members of the SLAH family also form heteromeric complexes, given their high sequence homology. To investigate this, we differentially tagged each of the four SLAH family proteins with either Strep or Flag tags. We then co-transfected pairwise combinations into cells, including SLAH1 + SLAH2, SLAH1 + SLAH4, SLAH2 + SLAH3, SLAH2 + SLAH4, and SLAH3 + SLAH4, in addition to the characterized SLAH1 + SLAH3 complex. Surprisingly, pull-down assay followed by Western blot analysis revealed that all pairwise combinations of SLAH family proteins can form heteromeric complexes in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 15). This observation prompted us to revisit the study by Paloma Cubero-Font et al.35, where SLAH1 was co-expressed with each member of the Arabidopsis SLAC/SLAH anion channel family. Functional assays showed that SLAH1 exclusively activated SLAH3, with no effect on SLAC1, SLAH2, or SLAH4. Combining our in vitro pull-down results with prior functional study, we conclude that while the high sequence homology within the SLAH family allows promiscuous physical interactions in vitro, SLAH1 specifically assembles with SLAH3 to form a functional complex in vivo. Further studies are therefore required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying this discrepancy between in vitro interaction potential and in vivo functional specificity within the SLAH family.

tRNA is crucial for protein synthesis, serving as an adaptor that links the genetic instructions in nucleic acid sequences to the proteins encoded by genes52,53,54. Any dysregulation of tRNAs—whether due to alterations in their abundance or function—can result in detrimental effects, potentially contributing to various human diseases, including neurological disorders and cancer55. A recent study56 underscores the vital role of tRNA in apoptosis, as tRNA can bind to cytochrome c and inhibit the activation of caspases. Furthermore, a tRNA-bridged dimeric structure of proton-activated chloride channel was observed57, further reinforcing the role of tRNA in cell death. The strong negative charge on the surface of tRNA enables it to interact with positively charged proteins in cells, thereby influencing the physiological functions of these binding proteins. Our discovery of tRNA regulating the ion channel SLAH/SLAC in plant cells broadens the scope of tRNA biology and offers valuable insights into the regulation of ion channels.

In conclusion, this study focused on SLAH proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana to investigate how plants manage nitrate and chloride ions to cope with abiotic stress—a key question in plant science. By overexpressing SLAH family proteins, we analyzed four distinct SLAH complex states. Through electrophysiological studies and mutation experiments, we clarified how tRNA inhibits SLAH1 activity and how SLAH1 functions as a regulatory subunit in coordination with SLAH3 to control anion transport. These findings offer a theoretical basis for enhancing plant stress resistance through targeted regulation of ion transport mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich: NaCl (S9888); HEPES (4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid; H3375). In addition, protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (04693116001) were obtained from Roche. Detergent LMNG (NG310) was obtained from Anatrace. Strep-Tactin resin (2-1208-500) and D-desthiobiotin (2-1000-005) were ordered from IBA. For cell culture, the human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293F cell line (R79007) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The HEK293F cell culture medium (SMM 293-TII) was obtained from Sino Biological; the Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (SV30010) was ordered from Hyclone. We obtained the transfect reagents Polyethylenimine (PEI, Linear, MW 25000; 23966) from Polysciences.

Cell culture and transfection

For protein expression and purification, the optimized coding cDNA for Arabidopsis thaliana SLAH1 (Uniprot: Q5E930) and SLAH3 (Uniprot: Q9FLV9), including a C-terminus tandem twin Strep-tag, was cloned into the pcDNA3.1(−) vector. HEK293F cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 1× penicillin/streptomycin in a Multitron-Pro shaker (Infors, 120 r.p.m.) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. In brief, for 1 L culture of HEK293F cells, 1 mg SLAH1 or SLAH3 plasmid was pre-incubated with 3 mg 25-kDa linear PEIs (Polysciences) in 50 ml fresh medium for 30 min prior to adding the mixture to cells. The transfected cells were cultured for 48 h before harvest. For the expression of the SLAH1/SLAH3 heterocomplex, 0.75 mg of SLAH1 plasmid and 0.75 mg of SLAH3 plasmid were mixed with 3 mg of PEI per 1 L of HEK293F cells.

Protein expression and purification for cryo-EM analysis

For one batch of protein purification, about six liters of transfected cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 × g. All procedures below were carried out at 4 °C or on ice.

For SLAH3 complex purification, harvested cells were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor, and then lysed by high-pressure homogenizer. After removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 45 min, the cell membrane fraction was pelleted by a 150,000 × g ultracentrifugation for 1 h. The membrane fraction was resuspended and solubilized in lysis buffer plus 1% (w/v) LMNG for 2 h with gentle rotation. After ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was passed through a column filled with Strep-Tactin Sepharose resin. The resin was washed 50 CV (column volume) with wash buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 0.005% (w/v) LMNG. The target SLAH3 protein was eluted with wash buffer plus 10 mM desthiobiotin. The eluted SLAH3 protein was concentrated to a final volume of approximately 100 μl by a 100 kDa cut-off centrifugal filter (Millipore) and further purified by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Superose 6 5/150, GE Healthcare) in SEC buffer containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.002% (w/v) LMNG, and 0.02% (w/v) DDM. The SEC fractions corresponding to the SLAH3 complex were collected for cryo-EM sample preparation. The peak fractions were concentrated to 20 mg/ml for grid preparation. A similar protocol was employed for the purification of the SLAH1 complex and the SLAH1/SLAH3 heterocomplex.

Electron microscopy sample preparation and imaging

The cryo-EM grids of SLAH family proteins were prepared using Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) at 8 °C and 100% humidity. 3–4 μL aliquots of samples at a concentration of 20 mg/ml were applied onto glow-discharged holey carbon grids (Quantifoil Au R1.2/1.3 300 mesh). After a waiting time of 5 s, the grids were blotted for 3 s and plunged into liquid ethane for quick freezing. The grids were screened on a Tecnai Arctica microscope (FEI) operated at 200 kV using a Falcon II direct electron detector (FEI). The qualified grids were transferred into a Titan Krios microscope (FEI) operated at 300 kV equipped with an energy filter (slit width 20 eV; GIF Quantum LS, Gatan) for data acquisition.

For the SLAH3 complex, images were recorded using a K3 submit direct electron detector (Gatan) and a GIF Quantum energy filter (slit width of 20 eV) in a super mode at a nominal magnification of 105,000 × g, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 0.4187 Å. Date acquisition was performed automatically using AutoEMation2.058 in a movie mode, with a frame exposure time of 0.08 s and a total exposure time of 2.56 s, resulting in a total of 32 frames per stack, and the total dose rate for each stack was approximately 50 e− Å−2. All 32 frames in each stack were aligned and summed using the whole-image motion correction program MotionCor259 and binned to a pixel size of 0.8374 Å.

For the SLAH1 complex, images were recorded similar to those of SLAH3 samples, except that the detector was equipped with a spherical aberration (CS) corrector and the final binned pixel size was 0.8697 Å.

For the SLAH1/SLAH3 heterocomplex, cryo-EM data were collected on a 300 kV Titan Krios G3i equipped with a Gatan K3 detector, a GIF Quantum energy filter (slit width of 20 eV), and a spherical aberration (CS) corrector. Micrographs were recorded with a defocus range of −1.3 to –1.8 μm. The total dose was about 50 e− Å−2 for each stack. Data collection was done using EPU data acquisition software in super resolution mode with a calibrated pixel size of 0.54 Å. All 32 frames in each stack were aligned and summed using the MotionCor2 and binned to a pixel size of 1.08 Å.

Image processing and 3D reconstruction

To investigate the transport mechanism of the SLAH family, we collected three data batches: 1329 images of SLAH3, 2862 images of the SLAH1 + SLAH3 heteromeric complex, and 1013 images of SLAH1. Image processing was performed using cryoSPARC software60.

For the data set of the SLAH3 complex, micrographs were imported, and the CTF corrections were performed using Patch CTF estimation. After the deletion of bad micrographs, 200 micrographs were used for automatic picking by blob picker, and these particles were subjected to 2D classification. The class averages representing projections of the SLAH3 complex in different orientations were chosen as templates for template picking from the whole dataset. A total of 1418 K particles were picked from 1329 micrographs. These particles were extracted and binned 4 times and subjected to 2D classification. After three rounds of 2D classification, 586 K particles in good 2D averages were chosen. These particles were subjected to the ab initio reconstruction. The maps of each class were measured in Chimera61, and the particles from the best class were selected and re-extracted to the original pixel size. After another round of ab initio reconstruction, three different states of the SLAH1 complex were identified. The best particles for SLAH3 complex were used for 3D reconstruction by non-uniform (NU) refinement62 to further improve data quality. Finally, a 2.63 Å resolution map with C3 symmetry imposed was obtained. The local resolution maps of the SLAH3 complex were calculated using local resolution estimation in cryoSPARC and displayed in ChimeraX63.

Similar data processing procedures were applied for the dataset of the SLAH1 complex. Finally, due to the binding of tRNA in the cytosol side of SLAH1, we imposed C1 on the final best particles and obtained a 3.18 Å resolution map of the SLAH1-tRNA complex.

For the data set of SLAH1 + SLAH3 heterocomplex, ab-intial classification clearly distinguished two different states of the complex. From further calculations using NU-refinement and CTF refinement, we obtained a 3.03 Å resolution map for 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3 + tRNA complex and a 3.18 Å resolution map for 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complex.

RNA sequencing and data analysis

Overexpressed SLAH1 proteins were obtained following affinity chromatography and gel-filtration chromatography. RNA was extracted using a phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation.

tRNA was isolated from total RNA using the Denaturing Urea Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Urea PAGE) method. Over 2 μg total RNA was resolved on 7.5% Urea PAGE gels (7 M Urea) and recovered within a size window of 60–100 nt for tRNA.

The demethylation section in rtStarTM tRF&tiRNA Pretreatment Kit was used for tRNA m1A&m3C demethylation treatment. A 50 μL demethylation reaction mixture was prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Then, 40 μL nuclease-free water and 10 μL 5 × Stop Buffer were added to terminate the reaction. Demethylated tRNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Demethylated tRNA was partially hydrolyzed according to Hydro-tRNAseq method. Partially hydrolyzed tRNA fragments were converted to barcoded small RNA sequencing libraries using NEBNext® Multiplex Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina® kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The completed libraries were qualified and quantified by the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. An equal amount of Hydro-tRNAseq libraries was mixed for the following sequencing on an Illumina sequencer. The DNA fragments in well-mixed libraries were denatured with 0.1 M NaOH to generate single-stranded DNA molecules, and loaded onto the reagent cartridge at a loading concentration. The sequencing run was performed on Illumina sequencer.

Sequencing quality was examined by FastQC software, and trimmed reads (trimmed 3′-adaptor bases by cutadapt) were aligned to the cytoplasmic mature-tRNA sequence obtained from GtRNAdb and the mitochondrial mature-tRNA sequences obtained from mitotRNAdb using BWA software. For tRNA alignment, the maximum mismatch was 2. The tRNAs expression profiling was calculated based on uniquely mapped reads and including mapped reads, respectively. The differentially expressed tRNAs were screened based on the count value with the R package edgeR. Principal Component Analysis, correlation analysis, Hierarchical Clustering, scatter plots, venn plots, and volcano plots were performed with the differentially expressed tRNAs in R or Python environment for statistical computing and graphics.

Model building

Models of full-length SLAH1 and SLAH3 were predicted on AlphaFold64,65. Sequence alignment and secondary structure prediction of SLAH1 and SLAH3 were used to aid the model building. The predicted model of SLAH3 was docked into the cryo-EM map with a resolution of 2.63 Å in Chimera and manually adjusted in Coot to acquire the atomic model of SLAH361,66. Model refinement was performed on the main chain of the atomic models using the real_space_refine module of PHENIX67 with secondary structure and geometry restraints to avoid over-fitting.

According to small RNA sequencing, the tRNA (His-GTG-1-1) is the most dominant class among the 75 nt tRNA candidates. The tRNA (His-GTG-1-1) sequence is: GCCGUGAUCGUAUAGUGGUUAGUACUCUGCGUUGUGGCCGCAGCAACCUCGGUUCGAAUCCGAGUCACGGCACCA. The 3D structure model for tRNA was predicted using trRosettaRNA68 and manually adjusted to fit in the map using COOT.

Then, the model of SLAH1 and tRNA was used initial model for the model building of the 3SLAH1 + tRNA complex. Similar procedures were performed for the 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH1 + tRNA complex and the 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 complex. Cryo-EM data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table S1.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording and data analysis

The DNA encoding SLAH1 or SLAH3 was subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(−) with or without an N-terminal GFP-tag. Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO) were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 100 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were transiently transfected with SLAH1 and/or SLAH3 or both using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Electrophysiology experiments were performed 24−48 h after transfection. Patch pipettes were pulled with P-97 (SUTTER INSTRUMENT) and heat polished to a resistance of 3–8 MΩ. Patch-clamp recordings were done with an Axopatch 200B amplifier and Axon Digidata 1550 A driven by Clampex10 software (Molecular Devices).

For the recording of anion (Cl−) mediated currents, pipettes were filled with the solution containing 150 mM HCl and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 adjusted with NMDG, and cells were bathed with bath solution containing 150 mM HCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 with NMDG. For the assessment of anion (Cl−) selectivity of SLAH3, pipettes were filled with the solution containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 3 mM Mg-ATP and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2 with NMDG, bath solution including three types that were high NaCl bath solution (135 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 with NMDG), low NaCl bath solution (9 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 260 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 with NMDG) and low Na+ bath solution (9 mM NaCl, 126 mM NMDG-Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 with NMDG). For the assessment of anion (Cl−) selectivity of SLAH1, the testing paradigm was the same as that of SLAH3, except that the pipette solution was supplemented with 10 mM RNase A, and the bath solution applied was only the low NaCl solution. For the assessment of relative nitrate-to-chloride permeabilities, the pipette solution containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgATP, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2 with NMDG, and the bath solution containing 135 mM NaNO3, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 with NMDG. Whole-cell currents were evoked by 800 ms voltage steps from −100 mV to +100 mV in 20 mV increments. All recordings were performed at room temperature (approximately 25 °C). All values were measured using Clampfit 10.6 Software.

Plant materials, vector construction, and growth conditions

For protoplast transformation, A. thaliana Col-0 were grown under an 8 h-light/16 h-dark photoperiod (22 °C–18 °C). Nicotiana benthamiana (Nb) plants were grown under a 16 h-light/8 h-dark photoperiod (24 °C−26 °C). For protoplast transformation, the coding sequences of AtSLAH1, AtSLAH17M, AtSLAH3, and AtOST1were amplified and inserted into pUC19 vector.

For the BIFC assay, the coding sequences of AtSLAH1, AtSLAH1(R/K mutant), or AtSLAH3 were amplified and inserted into pEG100-cYFP/nYFP vector. For Stomatal aperture quantification, the coding sequences of AtSLAH1, AtSLAH1(R/K mutant), or AtSLAH3 were amplified and inserted into pE1766 vector.

Transient expression in A. thaliana protoplasts and electrophysiological recording

Procedures for protoplast transformation were described previously69. A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts were isolated from 3 to 4-week-old Col-0 plants. Leaf slices from the fifth, sixth, and seventh true leaves of these plants were digested in enzyme solution for 3 h. The suspension was centrifuged and washed twice with W5 solution. Plasmids were transformed into protoplasts using DNA-PEG–calcium transfection. The transfected protoplasts were incubated at 22 °C for 16 h in WI solution and then were used for subsequent assays.

For the electrophysiological recording in protoplast, pipettes with a resistance of 10–20 MΩ were filled with the solution containing 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM EGTA, 3 mM Mg-ATP, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM mannitol, pH 7.2 with NMDG. Three concentrations of mannitol (150 mM, 100 mM, and 50 mM) were tested in the bath solution, and the final bath solution composition was determined to be 135 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, and 100 mM mannitol, pH 7.4 with NMDG. Whole-cell currents were evoked by 800 ms voltage steps from −100 mV to +100 mV in 20 mV increments. All recordings were performed at room temperature (approximately 25 °C). All values were measured using Clampfit 10.6 Software.

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression

The Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101) strains containing the indicated constructs were cultivated at 28 °C overnight, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 200 μM acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 5.6), kept under dark for 2 h (OD600 = 0.1–0.6), and subsequently syringe-infiltrated into Nb leaves as Agro-infiltration.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

For BIFC assay, the coding sequences of AtSLAH1 and AtSLAH3 were cloned into pEG100 vector to construct fusions expressing cYFP and nYFP. All of the constructs were introduced into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. Discs were removed from these leaves using a hole puncher at 42 h, 45 h, 48 h, and treated with ABA (final concentration: 100 μM) for time gradients. Discs were removed from these leaves using a hole puncher at 36 h and treated with water for 6 h after ABA (final concentration: 100 μM) for 6 h. Leaf discs subjected to different ABA treatments were harvested from the same leaf following the grouping scheme of the BiFC assay. Confocal imaging was performed using the Zeiss LSM880 at 48 h after Agro-infiltration.

Stomatal aperture quantification

For AtSLAH1, AtSLAH1(R/K mutant) or AtSLAH3 overexpression regulated stomatal aperture, 3–4 leaves from 4-week-old Nb plants were syringe infiltrated and subsequently flooded with Agrobacterium strains containing the indicated constructs in a buffer with 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20. At 36 h after Agro-infiltration, Stomatal aperture quantification leaves of the Nb were harvested and floated on stomatal opening buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM MES-KOH, pH 6.15) with the abaxial surfaces exposed to light for 3 h, and subsequently treated with mock or ABA (final concentration: 10 μM) for 1 h.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The 3D cryo-electron microscopy density map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the following accession codes: 3SLAH3 EMDB:63691; PDB:9M7R, 1SLAH1 + 2SLAH3 EMDB:63692; PDB:9M7S, 3SLAH1 + tRNA EMDB:63693; PDB:9M7U, 2SLAH1 + 1SLAH3+tRNA EMDB:63695, PDB:9M7W. The source data underlying Figs. 1a, g, 2b, c, 4e, 5d–f, 6a–d and Supplementary Figs. 10, 12, and 14 are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ouhibi, C. et al. Salt stress mitigation by seed priming with UV-C in lettuce plants: growth, antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds. Plant Physiol. Biochem 83, 126–133 (2014).

Zhu, J. K. Plant salt tolerance [Review]. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 66–71 (2001).

Singhal, R. K. et al. Crucial cell signaling compounds crosstalk and integrative multi-omics techniques for salinity stress tolerance in plants. Front Plant Sci. 12, 670369 (2021).

Dawood, M. F. A., Abeed, A. H. A. & Aldaby, E. E. S. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles model growth kinetic traits of some wheat cultivars under different water regimes. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 24, 129–140 (2019).

Gupta, A., Rico-Medina, A. & Caño-Delgado, A. I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 368, 266–269 (2020).

Nunes, T. D. G., Zhang, D. & Raissig, M. T. Form, development and function of grass stomata. Plant J. 101, 780–799 (2020).

Franks, P. J. & Farquhar, G. D. The mechanical diversity of stomata and its significance in gas-exchange control. Plant Physiol. 143, 78–87 (2007).

Daszkowska-Golec, A. & Szarejko, I. Open or close the gate – stomata action under the control of phytohormones in drought stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 138 (2013).

Yang, J., Li, C., Kong, D., Guo, F. & Wei, H. Light-mediated signaling and metabolic changes coordinate stomatal opening and closure. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 601478 (2020).

Hedrich, R., Busch, H. & Raschke, K. Ca2+ and nucleotide dependent regulation of voltage dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. EMBO J. 9, 3889–3892 (1990).

Linder, B. & Raschke, K. A slow anion channel in guard cells, activating at large hyperpolarization, may be principal for stomatal closing. FEBS Lett. 313, 27–30 (1992).

Schroeder, J. I. & Keller, B. U. Two types of anion channel currents in guard cells with distinct voltage regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 5025–5029 (1992).

Raschke, K., Shabahang, M. & Wolf, R. The slow and the quick anion conductance in whole guard cells: their voltage-dependent alternation, and the modulation of their activities by abscisic acid and CO 2. Planta 217, 639–650 (2003).

Meyer, S. et al. AtALMT12 represents an R-type anion channel required for stomatal movement in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 63, 1054–1062 (2010).

Hoekenga, O. A. et al. AtALMT1, which encodes a malate transporter, is identified as one of several genes critical for aluminum tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9738–9743 (2006).

Sasaki, T. et al. Closing plant stomata requires a homolog of an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 354–365 (2010).

Dreyer, I., Gomez-Porras, J. L., Riaño-Pachón, D. M., Hedrich, R. & Geiger, D. Molecular evolution of slow and quick anion channels (SLACs and QUACs/ALMTs). Front. Plant Sci. 3, 263 (2012).

Kashtoh, H. & Baek, K.-H. Structural and functional insights into the role of guard cell ion channels in abiotic stress-induced stomatal closure. Plants 10, 2774 (2021).

Brandt, B. et al. Reconstitution of abscisic acid activation of SLAC1 anion channel by CPK6 and OST1 kinases and branched ABI1 PP2C phosphatase action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10593–10598 (2012).

Chan, C. et al. STRESS INDUCED FACTOR 2 regulates Arabidopsis stomatal immunity through phosphorylation of the anion channel SLAC1. Plant Cell 32, 2216–2236 (2020).

Brandt, B. et al. Calcium specificity signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis guard cells. Elife 4, e03599 (2015).

Deng, Y. -n. et al. Structure and activity of SLAC1 channels for stomatal signaling in leaves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2015151118 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Structure of the Arabidopsis guard cell anion channel SLAC1 suggests activation mechanism by phosphorylation. Nat. Commun. 13, 2511 (2022).

Lee, Y. et al. Cryo-EM structures of the plant anion channel SLAC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana suggest a combined activation model. Nat. Commun. 14, 7345 (2023).

Geiger, D. et al. Activity of guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is controlled by drought-stress signaling kinase-phosphatase pair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21425–21430 (2009).

Zheng, X., He, K., Kleist, T., Chen, F. & Luan, S. Anion channel SLAH 3 functions in nitrate-dependent alleviation of ammonium toxicity in Arabidopsis. Plant, Cell Environ. 38, 474–486 (2015).

Qiu, J., Henderson, S. W., Tester, M., Roy, S. J. & Gilliham, M. SLAH1, a homologue of the slow type anion channel SLAC1, modulates shoot Cl− accumulation and salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 4495–4505 (2016).

Schmidt, C. & Schroeder, J. I. Anion selectivity of slow anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells (large nitrate permeability). Plant Physiol. 106, 383–391 (1994).

Geiger, D. et al. Stomatal closure by fast abscisic acid signaling is mediated by the guard cell anion channel SLAH3 and the receptor RCAR1. Sci. Signal. 4, ra32–ra32 (2011).

Geiger, D. et al. Guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is regulated by CDPK protein kinases with distinct Ca2+ affinities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8023–8028 (2010).

Negi, J. et al. CO2 regulator SLAC1 and its homologues are essential for anion homeostasis in plant cells. Nature 452, 483–486 (2008).

Vahisalu, T. et al. SLAC1 is required for plant guard cell S-type anion channel function in stomatal signalling. Nature 452, 487–491 (2008).

Liu, B. et al. The anion channel SLAH3 interacts with potassium channels to regulate nitrogen–potassium homeostasis and the membrane potential in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 35, 1259–1280 (2023).

Lehmann, J. et al. Acidosis-induced activation of anion channel SLAH3 in the flooding-related stress response of Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 31, 3575–3585.e3579 (2021).

Cubero-Font, P. et al. Silent S-type anion channel subunit SLAH1 gates SLAH3 open for chloride root-to-shoot translocation. Curr. Biol. 26, 2213–2220 (2016).

Gutermuth, T. et al. Pollen tube growth regulation by free anions depends on the interaction between the anion channel SLAH3 and calcium-dependent protein kinases CPK2 and CPK20. Plant Cell 25, 4525–4543 (2013).

Chen, Y. -h. et al. Homologue structure of the SLAC1 anion channel for closing stomata in leaves. Nature 467, 1074–1080 (2010).

Colmenero-Flores, J. M., Franco-Navarro, J. D., Cubero-Font, P., Peinado-Torrubia, P. & Rosales, M. A. Chloride as a beneficial macronutrient in higher plants: new roles and regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4686 (2019).

Broyer, T. C., Carlton, A. B., Johnson, C. M. & Stout, P. R. Chlorine - a micronutrient element for higher plants. Plant Physiol. 29, 526–532 (1954).

White, P. J. & Broadley, M. R. Chloride in soils and its uptake and movement within the plant: a review. Ann. Bot.-Lond. 88, 967–988 (2001).

Raven, J. A. Chloride: essential micronutrient and multifunctional beneficial ion. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 359–367 (2017).

Dechorgnat, J. et al. From the soil to the seeds: the long journey of nitrate in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 1349–1359 (2011).

O’Brien, J. A. et al. Nitrate transport, sensing, and responses in plants. Mol. Plant 9, 837–856 (2016).

Ye, J. Y., Tian, W. H. & Jin, C. W. Nitrogen in plants: from nutrition to the modulation of abiotic stress adaptation. Stress Biol. 2, 4 (2022).

Zayed, O. et al. Nitrogen journey in plants: from uptake to metabolism, stress response, and microbe interaction. Biomolecules 13, 1443 (2023).

Draper, S. R. Amino-acid changes associated with low-temperature treatment of Lolium-perenne. Phytochemistry 11, 639 (1972).

Fougere, F., Lerudulier, D. & Streeter, J. G. Effects of salt stress on amino-acid, organic-acid, and carbohydrate-composition of roots, bacteroids, and cytosol of alfalfa (medicago-sativa L). Plant Physiol. 96, 1228–1236 (1991).

Kaplan, F. & Guy, C. L. β-amylase induction and the protective role of maltose during temperature shock. Plant Physiol. 135, 1674–1684 (2004).

Usadel, B. et al. Multilevel genomic analysis of the response of transcripts, enzyme activities and metabolites in rosettes to a progressive decrease of temperature in the non-freezing range. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 518–547 (2008).

Lugan, R. et al. Metabolome and water homeostasis analysis of suggests that dehydration tolerance is a key response to osmotic stress in this halophyte. Plant J. 64, 215–229 (2010).

Wen, X. et al. Evolutionary study and structural basis of proton sensing by Mus GPR4 and Xenopus GPR4. Cell 188, 653–670.e624 (2025).

Phizicky, E. M. & Hopper, A. K. tRNA biology charges to the front. Gene Dev. 24, 1832–1860 (2010).

O’Donoghue, P., Ling, J. Q. & Söll, D. Transfer RNA function and evolution. RNA Biol. 15, 423–426 (2018).

Schimmel, P. The emerging complexity of the tRNA world: mammalian tRNAs beyond protein synthesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 19, 45–58 (2018).

Orellana, E. A., Siegal, E. & Gregory, R. tRNA dysregulation and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet 23, 651–664 (2022).

Mei, Y. D. et al. tRNA binds to cytochrome c and inhibits caspase activation. Mol. Cell 37, 668–678 (2010).

Chi, P. L. et al. Molecular insights into the inhibition of proton-activated chloride channel by transfer RNA. Cell Res. 34, 743–745 (2024).

Lei, J. L. & Frank, J. Automated acquisition of cryo-electron micrographs for single particle reconstruction on an FEI Tecnai electron microscope. J. Struct. Biol. 150, 69–80 (2005).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera-a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Punjani, A., Zhang, H. & Fleet, D. J. Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat. Methods 17, 1214–1221 (2020).

Goddard, T. D. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583 (2021).

Varadi, M. et al. AlphaFold protein structure database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D439–D444 (2022).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 58, 1948–1954 (2002).

Wang, W. K. et al. trRosettaRNA: automated prediction of RNA 3D structure with transformer network. Nat. Commun. 14, 7266 (2023).

Yoo, S. D., Cho, Y. H. & Sheen, J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1565–1572 (2007).

Smart, O. S., Goodfellow, J. M. & Wallace, B. A. The pore dimensions of gramicidin A. Biophys. J. 65, 2455–2460 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Tsinghua University Branch of China National Center for Protein Sciences (Beijing) for providing the cryo-EM facility support. We thank Dr. XiaoMin Li and Dr. Fan Yang for the data collection. The computation was completed using the Yanglab GPU workstation. This work was supported by funds from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1302701 for M.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32030056 for M.Y.; 82371533 for Z.L.; 82271582 for B.Z.), the Scientific Project of Beijing Life Science Academy (2024301QPIA01 to J.X.; 2025300CB0030 to S.Z.; 2024300CC0180 to C.L.; 2023300CA0090 to M.Y.), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (22ZR1449300 for Z.L.), the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (22XD1402400 for Z.L.), the Biomedical Engineering Special Program of ‘Science and Technology Innovation Projects’ from Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (23S11900600 for B.Z.), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (GZC20231291).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., M.Y., J.X., B.Z., and J.M. conceived the project. S.Z., B.Q., C.L., R.L., X.C., Jian.Y., Jing.Y., M.C., and B.L. performed protein purification, EM sample preparation, data collection, and structural determination. X.H., N.X., Y.S., and Y.L. performed cell culture, electrophysiology experiment, and data analysis. X.W., Z.H., D.W., and K.C. performed the RNA extraction and sequencing. K.Y., J.F., and T.L. perform the planta assay with the help of T.Q. S.Z. and B.Z. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors contributed to the discussion of the data and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shangyu Dang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Huang, X., Wang, X. et al. Structural insights into the coordinated regulation of the SLAH family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun 17, 585 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67283-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67283-6