Abstract

Insecticides are vital to combating world food shortages and transmission of vector-borne human diseases. Increasing insecticide resistance necessitates discovery of novel compounds against underutilized targets. Nanchung (Nan) and Inactive (Iav), the transient receptor potential vanilloid-type (TRPV) channels in insects, likely form a heteromeric channel (Nan-Iav) and are localized in mechanosensory chordotonal organs which confer gravitaxis, hearing and proprioception. Several insecticides, such as afidopyropen (AP), target Nan-Iav through unknown mechanisms. Effective against piercing-sucking (hemipteran) insects, AP disrupts chordotonal functions preventing feeding. AP can bind to Nan alone, but only Nan-Iav exhibits channel activity with agonists including endogenous nicotinamide (NAM). Despite its importance as an insecticide target, much is unknown about Nan-Iav, such as channel assembly, modulator binding sites, and Ca2+-dependent regulation, hampering further insecticide development. Here we present the cryo-electron microscopy structures of hemipteran Nan-Iav with calmodulin bound in the apo state and with AP and NAM bound to cytosolic ankyrin repeat domain (ARD) interfaces. Unexpectedly, we found that Nan alone can form a pentamer, stabilized through AP-mediated ARD interactions. Our study provides molecular insights into insecticide and agonist interactions with Nan-Iav, highlighting the importance of the ARD on channel function and assembly, while also probing regulation by Ca2+.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The disparity of global food insecurity in the context of severe climate change is a major hurdle for the 21st century that has cascading effects on society1,2. According to the 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report published by the World Health Organization, moderate to severe food insecurity affects around 2.33 billion people globally and is a persistent issue3,4. Unfortunately, it is estimated that 20–30%, or more, of crop yield is lost annually due to insect pests and pathogens, with global warming expected to exacerbate pesticide resistance and crop vulnerability4,5,6,7,8. Insecticide development is crucial not only to protect crops from pests and to mitigate insect-mediated pathogen transmission, but to control vector-borne human diseases like dengue, malaria, and Chagas disease, where insecticide resistance is on the rise5,9,10,11.

Among the major targets for neurotoxic insecticides, the heteromeric TRPV channel, Nanchung (Nan)-Inactive (Iav), was discovered only in the last decade to be the target of a class of insecticides that includes the commercial insecticides pymetrozine and pyrifluquinazon12,13,14. A semi-synthetic insecticide, afidopyropen (AP), was more recently developed and commercialized as several products powered by Inscalis® Active insecticide, which binds with sub-nanomolar potency15. AP exhibits low acute toxicity to pollinators, beneficial insects, and other non-target organisms, while relieving resistance pressure off other insecticides when used according to its label instructions16,17,18. Nan and Iav are widely conserved across insect species and are found co-expressed only in the chordotonal stretch receptor neurons of the antennae and appendages, where they are both required for hearing, gravity perception and proprioception13,16,19,20,21,22. Acting via a unique mechanism, AP, pymetrozine, and pyrifluquinazon stimulate Nan-Iav to ultimately silence proprioceptive signaling13,16,23. For piercing-sucking (hemipteran) insects such as aphids and whitefly, loss of proprioception compromises their ability to feed and ultimately leads to death13,24. Interestingly, AP exhibits both high and low affinity binding to Nan-Iav complexes and Nan alone, respectively. AP binding to Nan-Iav induces currents, but binding to Nan alone does not stimulate channel activity. Iav alone does not bind AP at all16. This suggests that either Nan and Iav associate to form different Nan-Iav channel assemblies (e.g., different stoichiometries or different arrangements within the same stoichiometry), or that AP binds to multiple sites. Additionally, the natural agonist, nicotinamide (NAM), binds to Drosophila Nan-Iav with micromolar affinity, exhibiting effects similar to AP in vitro16,25 and inhibiting fecundity and feeding in aphids, leading to mortality25,26. These data leave us with many questions. It is unclear, for instance, how Nan-Iav heteromers assemble, where small molecule modulators bind, and how these small molecules modulate channel function, resulting in silencing proprioception. It also remains to be explained why Nan alone has no activity while exhibiting reduced binding affinity for AP, whereas Nan-Iav heteromers are active and bind AP with higher affinity. Finally, little is known about the Ca2+-dependent regulation of Nan-Iav function and how it fits into neuronal signaling processes13,21.

In this work, we use cryo-EM together with electrophysiology and radioligand binding to reveal how Nan-Iav assembles and binds small molecule modulators. Additional discoveries of constitutively bound calmodulin (CaM) to Iav, and an AP-stabilized Nan pentamer, provide important insights into channel regulation by calcium, channel assembly, and the determinants of ligand binding affinity. Importantly, we demonstrate the central role of the ARD in these processes. Our study on a fully intact insect channel with cognate agricultural insecticide bound27,28,29 will hopefully facilitate insecticide development to improve efficacy, specificity and extend application of TRPV-targeted compounds to other species to combat the global issues of food insecurity and the spread of vector-borne human diseases.

Results

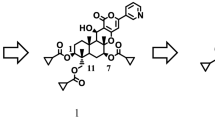

NAM and AP bind competitively to Stink bug Nanchung-Inactive

NAM, a natural agonist, and AP, a pyropene insecticide, are very different in size but share a 3-pyridyl ring (Fig. 1a), which has been shown to be critical for AP activity17. NAM competes with [3H]-AP for binding to stink bug Nan-Iav (Fig. 1b), exhibiting much lower affinity (Ki = 108 µM) than unlabeled AP (Ki = 0.01 nM). Whole-cell electrophysiology shows Nan-Iav is robustly stimulated by 1 mM NAM (Fig. 1c), exhibiting an apparent EC50 of ~0.1 mM (Supplementary Fig. 1a), comparable to the EC50 of 14 µM for Drosophila Nan-Iav25. NAM-evoked currents are non-desensitizing upon prolonged or repeated application and are reversible upon washout (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Although the insecticide AP essentially binds irreversibly in a manner competitive with NAM, the current elicited by AP is much weaker compared to NAM (Fig. 1b, c)16. This current is inhibited by the classic pore blocker ruthenium red (RR) (Fig. 1c). Thus, NAM is a low-affinity, high-efficacy agonist and AP is a high-affinity, low-efficacy agonist, indicating that irreversible AP binding locks the channel in a very low activity conformation—behavior more akin to an allosteric inhibitor. To understand how these two very differently behaving but related compounds interact with Nan-Iav to regulate channel function, we sought out structures of Nan-Iav with these compounds bound.

a NAM and AP share a common 3-pyridyl ring. b Displacement of [3H]-AP by NAM and unlabeled AP to Nan-Iav containing membranes. Ki values were computed using the Cheng-Prusoff equation (25 pM [3H]-AP). Data is represented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3 technical replicates). c Whole cell electrophysiology recordings of HEK293T cells overexpressing Nan-Iav at ±60 mV. Currents are robustly and reversibly stimulated by 1 mM NAM with competitive, irreversible binding of AP. Ruthenium red (RR) blocks channel conduction. Inset more clearly shows the effect of AP on outward current. d Overview of the cryo-EM reconstructions for Nan-Iav-CaM under different conditions and their respective models, as seen from the side. e Bottom-up (cytoplasmic) view of apo Nan-Iav-CaM and Nan+AP pentamer, denoting the Nan CTH. f Comparison of structural similarities and differences amongst TRPV3, Nan, and Iav+CaM with additional features highlighted in gray and the rotation of AR1 in Nan and Iav relative to the ARD and AR1 of TRPV3. The red arrows indicate the presence of longer loops in Nan in comparison with TRPV3 and Iav. The light blue arrows indicate the CTHs of Nan and Iav. Source data are provided as a source data file.

Architecture of Nanchung-Inactive-calmodulin heteromer

The brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys), which we utilized for our structural studies on insecticide binding to Nan and Iav, is an invasive hemipteran pest in 40 US states, Canada, and several European countries30. We first generated a bicistronic construct for robust co-expression of Nan and Iav (Supplementary Fig. 1c), because while Nan alone can form intact AP-stabilized channels, Iav cannot (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e)16. We further found that the presence of Ca2+ affects the gel filtration (GF) profile of Nan-Iav, where EDTA yields a sharper peak compared to when Ca2+ is present (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g). We therefore determined structures of stink bug Nan-Iav by cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to high resolution in the apo (2.82 Å), NAM-bound as-isolated (2.49 Å) and +EDTA (2.85 Å), and AP-bound states +CaCl2 (3.08 Å) and +EDTA (3.01 Å) (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Figs. 2–6, Table 1). We also isolated Nan-only channel stabilized by AP (3.28 Å) (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 7). In attempts to get the Nan-only structure we observed predominantly pentameric channels, but only when AP was incubated with the cells or membranes prior to solubilization, which was time dependent (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Moreover, the insecticide pymetrozine (PM) exhibits competitive binding with [3H]-AP to Nan-Iav expressing HEK293 cells (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Likewise, we also observed Nan pentamers stabilized by PM (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Attempts to isolate intact channels of apo Nan were unsuccessful.

We found that Nan-Iav tetramers always follow a 2:2 stoichiometry, with alternating Nan and Iav protomers in a C2 symmetric fashion (Fig. 1e). Nan and Iav are readily differentiated based on their C-termini. In the case of Nan, the C-terminal helix (CTH) lies against the ARD, whereas the CTH of Iav extends away from the membrane and, to our surprise, a native calmodulin (CaM) was found to bind to the CTH of Iav.

The overall topology of Nan and Iav follow the typical TRPV design31, where Nan, Iav and TRPV all have 6 ankyrin repeats (ARs) within the ARD (Fig. 1f). The transmembrane domain (TMD) can be divided into the voltage sensor-like domain (VSLD), comprising transmembrane helices S1-S4, and the pore region, comprising S5 and S6 as well as the pore loop (PL) and pore helix (PH). Finally, the TMD and ARD are linked via the coupling domain (CD), which lies adjacent the TRP helix that leads from S6 to the CTH. A common distinguishing feature of Nan and Iav is the tilt of AR1 with respect to the rest of the ARD (~100° in Nan and ~60° in Iav). Nan also possesses structured linkers between AR1-AR2 (63-140) and AR3-AR4 (202-249), long extracellular loops between S1-S2 (residues 427-584) and S5-PH (720-739) that can coordinate Ca2+ (as we will discuss later). The main distinctive feature of Iav is the extended CTH to which CaM is bound.

Nan-Iav-CaM heteromer has two distinct ARD junctions

Within the tetramer the cytosolic domain is stabilized by interactions between the ARD from one protomer and CD from a neighboring protomer (Fig. 1e). Due to the heteromeric nature of Nan-Iav-CaM, there are two such interfaces, which we term the tight and loose junctions (Fig. 2a). The tight junction is where the Nan ARD binds to the Iav CD, and the loose junction occurs where the ARD of Iav binds to the CD of Nan. The tight junction is characterized by having a several fold greater contact interface than the loose junction (Supplementary Fig. 9a–f) and consequently is less dynamic and better resolved than the loose junction. Additionally, within the loose junction, we observed a peptide-like density which we assigned as part of the N-terminus of Iav, although we were not able to assign the primary sequence (Supplementary Fig. 9g).

a Bottom-up (cytoplasmic) view of surface representation of Nan-Iav-CaM with contact surface bolded to show more extensive contacts and NAM binding to the tight junction, and less extensive contacts at the loose junction. b NAM binds to a cavity in the ARD of Nan, with inset showing viewing pose. c NAM binding site and cryo-EM density, highlighting important residues, as schematically depicted in (d). e Equilibrium dissociation constants (Ki) of NAM determined by competition with [3H]-AP and utilizing the Cheng-Prusoff equation and the respective [3H]-AP Kd values for mutants (Table 3). Affinities exceeding 10 mM could not be accurately determined. Fitted NAM Ki values are plotted as mean ± 95% confidence intervals (CI), from titration curves shown in Supplementary Fig. 11c. f A representative whole-cell electrophysiology recordings (+60 mV) for WT Nan-Iav and NanY177A-Iav showing the effects on NAM and AP binding. g Current density plots for WT Nan-Iav and NanY177A-Iav, where means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) are plotted, n = 4 biological replicates. Students two-tailed t-test results: ns = not significant (P = 0.3446), ***represents P < 0.001 (P = 0.00048). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Identification of the binding site for the agonist nicotinamide

TRPV channels most typically interact with small molecule agonists/antagonists through binding to the transmembrane region32,33,34,35 or CDs36. Unexpectedly, density for NAM was identified within a cavity formed by the ARD of Nan at the tight junctions (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 10). This stoichiometry of 2:1 NAM:Nan-Iav-CaM agrees with previous biochemical data for Drosophila Nan-Iav25. The binding pocket for NAM is largely formed by the long loops connecting ARs 1-3 of Nan (Fig. 2b) and is completed by the CD β-sheets of Iav, leaving a small lateral opening to the cytoplasm (Fig. 2c). A density is also present in the apo map, but it is smaller, weaker, featureless, and offset from the NAM density (Supplementary Fig. 10). The pocket is comprised largely of hydrophobic (Nan: V137, L147) and aromatic residues (Nan: Y24, Y172, Y177, F213, Iav: Y325, W323), including acidic residues Nan: E139 and E180 (Fig. 2c, d). NAM binds deep within the pocket, stabilized largely through a π-stacking interaction between NanY177 and the 3-pyridyl ring of NAM (Fig. 2c, d). To probe the contributions of individual amino acids, we performed mutagenesis and functionally characterized them through binding experiments and whole cell electrophysiology. Ki values for NAM binding were calculated by cold competition binding assays against [3H]-AP (Supplementary Fig. 11). The direct binding affinity (Kd) of [3H]-AP to each mutant was used in the calculation of NAM Ki, therefore accounting for differences in AP binding affinity between mutants. Mutation of NanY177 to alanine lowers NAM binding affinity >100 fold (Ki > 10 mM, Fig. 2e and Table 2) and abolishes NAM-induced channel activity (Fig. 2f). Because the channel activity of the mutant elicited by 10 µM AP was not significantly impacted, the channel integrity for this mutant is maintained (Fig. 2g). The importance of the p-stacking interaction is highlighted by the partial restoration of NAM binding to the NanY177F mutant, albeit with ~10-fold weaker affinity than WT (Fig. 2e). IavW323 and IavY325 are also critical for NAM binding as alanine mutations of these residues eliminated NAM binding. Mutation of NanY172 to alanine, however, did not eliminate NAM binding, but raising the Ki for NAM by two orders of magnitude, whereas mutation to phenylalanine only increased Ki by ~10-fold (Fig. 2e and Table 2).

The insecticide afidopyropen binds to the same site as nicotinamide

AP binds competitively with NAM (Fig. 1b, c) to the tight junction at Nan-Iav interfaces (Fig. 3a), where it directly increases tight junction contact area (Supplementary Fig. 9) by completely filling the highly conserved and generally electronegative cavity (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Fig. 10b, d). The maximized contact made by AP to the protein, including many hydrophobic residues and two acidic residues, drives the picomolar affinity of AP to Nan-Iav (Fig. 3c, d). This maximized contact with the cavity makes the contributions of any one residue to binding less critical. However, the π-stacking interaction between NanY177 and the 3-pyridyl of AP remains the single most critical interaction. NanY177F has a similar Kd for [3H]-AP binding as WT, whereas NanY177A exhibits a ~200-fold greater Kd than WT (Fig. 3e and Table 3). Additionally, NanY172A exhibits a ~100-fold increase in [3H]-AP Kd while NanY172F is only 3-fold different, indicating NanY172 may form weak or indirect H-bonds with AP hydroxyl/carbonyl groups. In Iav, both alanine mutations of IavY325 and IavW323 reduce binding of [3H]-AP by 61-fold and 17-fold relative to WT, respectively. These trends are similar when comparing Ki values determined by cold AP competition of [3H]-AP (Table 4).

a Bottom-up (cytoplasmic) view of the surface representation of Nan-Iav-CaM showing bolded contact surfaces and AP binding to the tight junction. b Nan binding pocket electrostatics with AP bound. c AP binding site and cryo-EM density, highlighting important residues, as schematically depicted in (d). e Equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) of [3H]-AP, as tabulated in Table 3. Fitted AP Kd values are plotted as mean ± 95% confidence intervals (CI), from titration curves shown in Supplementary Fig. 11a. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Conformational changes induced by ligand binding to Nan-Iav

Based on our structural and functional data, we conclude that the tight junction between ARDs serves as the binding site for the natural agonist and insecticide (AP) to Nan-Iav. This is likely true for the other insect TRPV-specific commercial insecticides, pymetrozine, which binds competitively with [3H]-AP (Supplementary Fig. 8b)16, and its derivative deacetyl-pyrifluquinazon13. Moreover, the conformational changes elicited by agonist or insecticide binding differentially control channel activity. Next, we compared the interface geometry and contact area between protomers in the cytoplasmic domain for the different states (Supplementary Fig. 9a–f).

Compared to apo, binding of NAM induces an apparent 7.2° clockwise rotation of the N-terminal half of the Nan ARDs when viewed from the cytoplasm, imparting a greater contact area at the tight junction (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). This motion of the Nan ARD is coupled to a shift in the CTH of Iav, with CaM apparently shifting by 4.6 Å. The loose junction, however, does not significantly change upon NAM binding.

a bottom-up (cytoplasmic) view highlighting the structural changes of the ARDs between apo and NAM (as-is) Nan-Iav-CaM. b bottom-up (cytoplasmic) view highlighting the structural changes of the ARDs between apo and AP(+Ca2+) Nan-Iav-CaM. c Side view showing structural changes between apo, NAM (as-is) and AP (+Ca2+), where the only changes observed are of the ARD. d bottom-up view (top panel) and side view (lower panel) of Nan-Iav-CaM +AP showing the effects of Ca2+ on CaM (red surface representation) conformation. e Structural overlay of AP-bound Nan-Iav-CaM structures (as indicated by color coding), where Ca2+ is present (+Ca2+) or absent (+EDTA). Conformational changes are limited to the CTH and ARD of Iav. f CaM (red surface) binds to Iav CTH, where Iav(W701) inserts into the CaM cavity. The C-terminal truncation of the CTH from A697 is indicated by the outlined region. g Whole-cell electrophysiology recordings (±60 mV) of WT Nan-Iav and Nan-Iav(∆697-C) and Nan-IavW701A demonstrate reduced inhibition by Ca2+ when CaM binding is disrupted. The bar graphs quantify the inhibition from 1 mM Ca2+ on inward (top panel) and outward (lower panel) currents. Means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) are plotted, and biological replicate numbers (n) are indicated under the respective bars. Statistical significance was calculated by ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test: ns = not significant (P = 0.861 for inward current, P = 0.882 for outward current), **represents P < 0.01 (P = 0.00523 for WT vs ∆C-ter, P = 0.00467 for WT vs W701A), ***represents P < 0.001. h A model for channel gating by agonist binding to the ARD of Nan-Iav-CaM, where channel opening induces Ca2+ influx, which binds to CaM to subsequently inhibit channel conductance. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Binding of AP, however, induces a much more substantial conformational change, where the entire Nan ARDs rotate clockwise with the N-terminal half rotating by 11.1° and C-terminal half by 7.8° (Fig. 4b). This whole-ARD rotation of Nan affects both the tight and loose junctions, yielding a more square geometry to the ARD tetramer (Supplementary Fig. 9d). This effect is likely brought about by the much larger size of AP, which introduces an additional ~400 Å2 of contact at the tight junction (Supplementary Fig. 9a, d).

When viewed from the side, the motions of the Nan ARD induced by NAM and AP appear to raise the ARDs up towards the membrane (Fig. 4c). These lateral and vertical rotations of the ARD induced by NAM and AP binding are expected to be transmitted via the CD to induce changes in the pore region for channel opening, as similar motions were observed in other TRPV channels34,35,37,38. However, there is a lack of significant conformation change in the CD and pore region, so the channels in all our structures are closed (Supplementary Fig. 12). This may be a consequence of detergent solubilization of Nan-Iav, where the lack of a lipid membrane weakens coupling between the ARDs and the pore, as is often observed in agonist-bound TRP channel structures36,39,40,41.

Calcium regulation of Nan-Iav through calmodulin

Upon initially solving the structure of the Nan-Iav complex, we were puzzled by an unexpected density below the ARD of Iav. Through careful analysis of the cryo-EM density, we modeled the N-lobe of adventitiously-bound human CaM grasping the C-terminal helix of Iav (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 13a), which was confirmed by Western blot (Supplementary Fig. 13a–c). To probe the possible regulation by Ca2+ through CaM, we determined the structures of Nan-Iav-CaM +AP in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ as well as 5 mM EDTA. Addition of Ca2+ still only resolved the Ca2+-bound N-lobe of CaM bound to the Iav CTH (Fig. 4d), where we observed density consistent with two Ca2+ ions bound in the +Ca2+ condition (Supplementary Fig. 13d). Chelation of Ca2+ by 5 mM EDTA revealed loss of these Ca2+ densities (Supplementary Fig. 13e) as well as binding of the CaM C-lobe across the tight junction to the adjacent Nan ARD while the Ca2+-free CaM N-lobe remains bound to the Iav CTH (Fig. 4d, e). This mostly induces a change in the Iav CTH and a slight change in the Iav ARD. Again, we did not observe any significant conformational changes within the transmembrane region (Supplementary Fig. 12b, d).

Electrophysiological recordings of WT Nan-Iav in HEK293T cells show a Ca2+-dependent inhibition of current, where 1 mM Ca2+ inhibits inward and outward currents ~50 and ~20%, respectively (Fig. 4g). Mutating two conserved Ca2+-coordinating residues in the extracellular loop of Nan did not change the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of Nan-Iav (Supplementary Fig. 14), leaving intracellular CaM-Iav as the potential regulatory site. Both, mutation of IavW701 to alanine—which inserts into the CaM pocket (Fig. 4f)—or C-terminal truncation of Iav (Iav∆(697-986)) results in a significant reduction in the CaM signal on Western blot (Supplementary Fig. 13a–c). Both also exhibit significantly reduced inhibition by Ca2+, where inhibition of inward current is particularly affected (~10% current inhibition) (Fig. 4g). This data suggests that Ca2+-dependent binding of the C-lobe of CaM to Nan may regulate channel function by modulating ARD conformation, as summarized in the proposed model depicted in Fig. 4h.

Nanchung pentamerization is induced by AP binding

Our initial attempts to purify Nan without added ligand proved futile, so AP was added to Nan expression cultures to help stabilize the channel, incubating for 30 min prior to harvesting. In gel filtration traces we noted the peak sharpens with longer AP incubation (Supplementary Fig. 8a). The 2D class averages from the 30 min AP sample showed a range of oligomeric states, with protomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers and pentamers clearly discernable (Fig. 5a). This is consistent with the gel filtration profile from short AP incubation being broader in the low molecular weight range compared to the sharp profile from long AP incubation (Supplementary Fig. 8a). We note that it is possible that poor particle alignments in the 2D classification or flexibility could contribute to these apparent monomer/dimer/trimer classes, but that such classes are only visible in the dataset where AP was incubated only 30 min before cell harvest, and not in the dataset where AP was incubated with cells from the time of baculovirus infection. Interestingly, dimer and trimer classes exhibited a contact angle more consistent with that of a pentamer (~108°), as opposed to a tetramer (~90°) (Fig. 5b). While NAM was unable to stabilize Nan alone, we also observed pentamers when incubating with another insecticide, PM (Supplementary Fig. 8c). Intrigued by the pentameric class, AP was included from the start of Nan expression allowing us to solve the structure of the Nan+AP pentamer. While the ARD stably assembles into a pentamer with full AP occupancy of each binding pocket, it is not C5 symmetric (Supplementary Fig. 9f). We were unable to resolve the pore domain (S5-pore helix-S6), indicating it is dynamic and heterogeneous. This data suggests that AP binding induces Nan-alone to slowly assemble into non-functional pentameric channels.

a Representative 2D class averages Nan incubated with AP briefly before extraction, showing side views (upper) and bottom-up views (lower) of various oligomeric states. Angle of protomer contact is estimated by the red lines. b Comparison of tight junction contact angle and contact area (bolded surface), AP binding (as red sticks), and contact angle for Nan-Iav-CaM (upper panel) and Nan+AP pentamer (lower panel). The bracketed area (*) indicates interior contact comparison for Nan-Iav-CaM tight junction versus Nan+AP pentamer. c Cartoon representation of the AP binding sites of Nan-Iav tetramers and Nan pentamers with dashed lines indicating possible hydrogen bonds. d [3H]-AP binding to WT and mutant Nan-only membranes showing dissociation constants (Kd). Data are plotted as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3 technical replicates). e A model for AP-induced pentamerization of Nan in membranes with excess Nan to Iav. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Inspection of the binding site shows that AP binds nearly identically to pentameric Nan as in Nan-Iav-CaM heteromers (Fig. 5c). This is reflected in the similar [3H]-AP binding affinities between Nan-Iav (Kd = 0.017 nM, Fig. 3e) and Nan-only (Kd = 0.089 nM, Fig. 5d). The differences in the binding site are in the CD of the adjacent Iav/Nan protomer. The critical IavW323 is conserved as NanW341, and IavF322 is NanY340; however, IavY325 is NanI343 (Fig. 5c). This change alters the deepest part of the cavity where the 3-pyridyl ring of AP binds. This renders AP more sensitive to mutation of NanY177, where NanY177A in Nan-only lacks measurable binding of [3H]-AP and NanY172A has a 7.5-fold higher Kd for [3H]-AP compared to WT Nan (Fig. 5d). This altered cavity architecture around the 3-pyridyl of AP likely explains the drop in binding affinity for AP to Nan-alone relative to Nan-Iav.

We next analyzed the inter-subunit contacts to probe the reason for Nan pentamerization. Nan-Iav-CaM is stabilized by extensive contacts in the TM region and additional contacts in the cytosolic domain, resulting in ~86° and ~94° contact angles at the tight junction and loose junctions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 9a–e). In Nan-Iav-CaM +AP the tight junction interface has ~1300–1400 Å2 of buried surface area (Supplementary Fig. 9d, e), which includes the AP site and additional interior contacts denoted by the bracketed region in Fig. 5b. Pentameric Nan, however, only has stable contacts at the ARD interface, and the total buried surface area is lower (~1100 Å2) with reduction in interior contacts and additional exterior contacts (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 9f). AP itself makes up ~22% (~250 Å2) of this interface, which is consistent with NAM (a much smaller molecule) being unable to stabilize Nan-only channels. Together, these effects explain why AP binding is a necessary pre-requisite for oligomerization of Nan and determines the wider 108° geometry of the Nan-Nan interface that drives pentamerization (Supplementary Fig. 9f).

Discussion

Our structural analyses of the insect Nan-Iav TRP channel reveals several intriguing features unique to this channel. First, while most TRP channels are homomeric, mammalian heteromeric TRP channels adopt a 1:3 ratio of protomers42,43. We show that Nan-Iav, however, exhibits a 2:2 stoichiometry. Moreover, this unique stoichiometry naturally possesses two different interfaces at the cytoplasmic ARD, with our study unequivocally demonstrating that one of these interfaces of Nan-Iav acts as the binding site for endogenous agonist and insecticides. The importance of the ARD interface for mammalian homomeric TRP channel gating has been established36, and binding of a synthetic compound to this interface in TRPV2 was recently shown44. Interestingly, NAM binding invokes a strong current, which is reversible by washing due to its rather weak binding affinity. In contrast, the current induced by AP is weak but sustained, with its slow off rate contributing to a binding affinity six orders of magnitude tighter than for NAM. It is therefore conceivable that the high-affinity but low-efficacy insecticide, AP, may act by preventing the natural agonist NAM from reaching its cognate site within TRPV. Additionally, the irreversible binding of AP conformationally locks the channel, acting like a partial inhibitor. Despite all our structures exhibiting a closed pore, the differential effects of NAM and AP binding on ARD conformation must be communicated to the pore. This locking of channel function in a weakly conductive state, as observed in our electrophysiology experiments, may also contribute to the insecticidal action of AP to affect chordotonal function and thus disrupt various physiological processes in the insect, such as feeding, movement, hearing, and oviposition13,16,19,22. Although the AP binding site is highly conserved among a diverse array of insect species, only certain piercing, sucking insects are effectively targeted15,16,17. Factors such as the pharmacokinetics and feeding biology of the insects would also determine insecticidal effects and efficacy.

Surprisingly, we found that AP drives progressive assembly of Nan monomers into pentameric assemblies. Three lines of data suggest that the Nan TMD cannot self-assemble to yield a defined functional pore: It is known that both Nan and Iav are required for channel function13,16,19,21, it was not possible to obtain the 3D reconstruction of Nan alone without the addition of AP, and the pore region of the Nan-AP pentamer is heterogenous and unresolved. We also note that NAM is unable to stabilize Nan alone, but another insecticide, PM, also stabilizes Nan pentamers (Supplementary Fig. 8c). We therefore propose a model (Fig. 5e) where, given an excess of Nan over Iav in the membrane, Nan-Iav heteromers will stably form and remain intact, while excess Nan likely exists as only weakly associated oligomers. Addition of insecticide (AP) stabilizes inter-ARD contacts by first binding to Nan protomers. Over time, protomers assemble into oligomers and ultimately pentamers. This differs from the reported TRPV3 pentamer, which was proposed to arise from rearrangement of existing tetramers45. While this model applies to the interpretation of over-expression systems, it is possible similar processes occur in vivo. Nan is known to be more widely expressed than Iav, Nan also reportedly interacts with insect TRPA, known as water witch, for hygrosensation, and that a portion of Nan and/or Iav localize to the ER, especially under over-expression conditions13,46,47,48. This flexible association of Nan would best be accommodated if Nan alone exists as weakly associated non-functional oligomers or monomers. Nan pentamerization may therefore represent an additional level of regulation by insecticides targeting this channel. AP binding to Nan does not appear to disrupt heteromers but AP-induced Nan pentamerization reduces the available pool of Nan for functional heteromer formation at the plasma membrane. For instance, pentamer formation and thus Nan sequestration may contribute to the long-lasting effects and persistence that has been reported for insecticides like PM and AP49,50,51. We acknowledge, however, that our study lacks evidence for pentamer formation in native insect cells, and we believe this is an avenue worth pursuing in future studies.

We also show that Nan-Iav is regulated by Ca2+ through a constitutively bound CaM. Importantly, this Ca2+-dependent CaM regulation of Nan-Iav is distinct from other ion channels, such as the voltage-gated Na+ and TRPV5/6 channels52,53,54,55,56,57. In the Nav1.2 channel, the CaM C-lobe binds to the C-terminal domain (CTD) helix, and Ca2+ induces binding of the N-lobe to the distal part of the CTD56. In TRPV5/6 channels, CaM C-lobe binds to the CTH, and Ca2+ induces the N-lobe to extend up towards the pore to block cation permeation53,54. We propose a model for Ca2+ regulation of Nan-Iav-CaM function (Fig. 4h) where the CaM N-lobe is constitutively bound to the CTH of Iav, and in a resting (low [Ca2+] state) the CaM C-lobe interacts with Nan to stabilize the ARD conformation for channel opening. Binding of agonists/insecticides to the channel induces pore opening, resulting in an influx of Ca2+. This Ca2+ then binds to CaM and induces the C-lobe to dissociate from the ARD of Nan. This modulates ARD movements to induce Ca2+-dependent inhibition or desensitization, since prevention of CaM binding essentially eliminates the inhibitory effect of Ca2+. The quick recovery of the channel current upon washout of calcium (Fig. 4g) suggests this mechanism serves to rapidly respond to neuronal signaling through Ca2+. Additionally, the extensive unresolved C-terminus of Iav is reported to have additional roles in channel targeting and current regulation21.

Finally, our studies present high-resolution structures of an insecticide-insect TRP channel complex of agricultural significance, which has not been previously done to the best of our knowledge. The caveat being that our insect channel was structurally and functionally characterized from human-derived cells (HEK293S GnTi–), rather than insect cells. With the rising concerns of insecticide resistance and continued pressures of food security and vector-borne human diseases, our work provides important information that will facilitate the development of new insecticides for the benefit of human health and global food security. Insecticides like AP have been shown to be effective against select pests while having an environmentally friendly profile by having low acute toxicity to beneficial pollinators, when used according to respective label instructions13,16. Moreover, tests of some AP derivatives on mosquitos resulted in their eventual inability to fly17. Knowledge of how these modulatory compounds bind to Nan-Iav provides a means to more easily modify existing compounds or develop novel ones, for more effective and specific targeting to insect pests. Our work shows that the ARD interface of Nan-Iav is critical not only for the modulation of activity by endogenous and insecticide compounds and Ca2+-CaM, but also for channel assembly. We speculate that the disruption of heteromer assembly by small molecules could be a unique and promising avenue for the development of ion channel inhibitors.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Full length brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys) Nanchung and Inactive were selected for its superior stability in detergent from a screen of 8 orthologs. The synthetic genes were codon optimized for human expression and cloned into pBacMam pCMV-DEST vector (Life Technologies) using XhoI and EcoRI such that they are in frame with HRC-3C protease (PPX) -cleavable C-terminal GFP-FLAG-10xHis and mCherry-FLAG-10xHis tags for expression alone58. The primers used for cloning Nan and Iav into pBacMam are:

Nan-F 5′ TTATCGCTCGAGCCACCATGGGCAACACCGAGAGC,

Nan-R 5′ TTATCGGAATTCGCGCTGAAGGGGTTCTTGTTCTTGG,

Iav-F 5′ TTATCGCTCGAGCCACCATGGGCATCATCTGGGGCTCTG,

Iav-R 5′ TTATCGGAATTCGCCATAGAATCCTGGTCGCTGGGC.

To ensure co-expression of Nan and Iav, we utilized a bicistronic construct where Iav-GFP-10xHis and Nan-mCherry-FLAG are separated by the picornavirus P2A peptide59, allowing ribosome skipping and translation of two separate polypeptides (Supplementary Fig. 1c). This construct was cloned into a modified pEZTBM vector (Addgene plasmid # 74099; http://n2t.net/addgene:74099; RRID:Addgene_74099)60. Cloning was achieved by first inserting the P2A sequence into the multiple cloning site of pEZTBM using the primers: 5′ AGCAGGTGATGTTGAAGAAAACCCCGGGCCTGTCGACACTGCAGGGATCCGAGGTACCAAGC, 5′ TGCTTTAGCAGAGAGAAGTTTGTGGCGCCGCTGCCCGCGGCCGCCTCGAGG, followed by blunt-ended ligation. A 3′ NotI site was introduced into the Iav construct (5′ CACCACCATCACCATCACGCGGCCGCTGATAATCTAGAGCCTGC, 5′ GCAGGCTCTAGATTATCAGCGGCCGCGTGATGGTGATGGTGGTG), then XhoI and NotI were used to insert Iav-PPX-GFP-10xHis into the pEZTBM-P2A construct. Finally, Nan-PPX-mCherry-FLAG was amplified and cloned into this vector using the primers: 5′ CCCTCGAGCCACCGTCGACATGGGCAACACCG, 5′ GAGACTGCAGGCGGTACCTCTAGATTATCACTTGTCATCGT followed by digestion with SalI and KpnI, then ligation.

Bacmid was prepared by transformation of the pBacMam or pEZTBM constructs into DH10Bac (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Baculovirus was prepared by transfecting 50 mL of Sf9 cells at 1 M/mL with 100 µg of bacmid using 300 µg PEI and incubating for 15 min in ESF media prior to addition to the cells. The virus was passaged twice to boost viral titre by infecting 300 mL cultures of Sf9 cells at 2 M/mL with 5%(v/v) of the preceding passage of virus.

Purification of stink bug Nanchung-Inactive heteromer: Nan-Iav was expressed in HEK293S GnTI- cells (ATCC), where 1.2–1.8 L cultures at 1–1.5 M/mL were infected with 3% (v/v) baculovirus and cultured for ~1 day at 37 °C. Expression was induced by supplementation with 10 mM Na-Butyrate and the cultures incubated at 30 °C for 48 h with 130 rpm aeration, 8% CO2, and 100% humidity. Cultures were harvested and resuspended in 50TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10%(w/v) glycerol) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/mL aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, 2 mg/mL iodoacetamide and a small quantity of Bovine DNAse I. The cell suspension was then sonicated 3x 30 s on ice, then extracted with 20 mM DDM, 2 mM CHS for 1 h on a rotator at 4 °C. Lysates were clarified at 16,000x rpm, 4 °C for 30 min and incubated for 1.5 h with 2 mL anti-FLAG SM2 resin. Resin was then washed with 5 CV wash buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 550 mM NaCl, 10%(w/v) glycerol, 10 mM MgATP, 0.02% GDN), 5 CV wash buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 550 mM NaCl, 10%(w/v) glycerol, 0.02% GDN), 10CV wash buffer 3 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10%(w/v) glycerol, 0.02% GDN), and eluted with 5 CV elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10%(w/v) glycerol, 0.02% GDN, 0.2 mg mL−1 FLAG peptide). The FLAG eluents were then diluted two-fold with wash buffer 3 and incubated for 1.5 h with 1 mL Co2+-TALON resin at 4 °C on a rotator. The Resin was then washed with 5 CV wash buffer 2, 5 CV wash buffer 5 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10%(w/v) glycerol, 0.02% GDN), and eluted with 5 CV elution buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 10%(w/v) glycerol, 250 mM imidazole, 0.02% GDN). The concentrated eluent was further purified on a Superose 6 Increase (Cytiva) column equilibrated with 20TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl) with 5%(w/v) glycerol and 0.02% GDN. Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated to 1–2 mg/mL, then 2% DMSO added for grid freezing. For Nan-Iav with NAM (as-is), 100 mM NAM was included in the extraction and purification with 2 mM included in the gel filtration buffer, then 50 mM included prior to grid freezing. For Nan-Iav +NAM + EDTA, 5 mM EDTA was included during the extraction and throughout the purification, except for steps immediately preceding and during Co2+-TALON purification. NAM was added at 20 mM 15 min prior to grid freezing. For Nan-Iav +AP, 50 µM AP was included prior to grid freezing and either 5 mM EDTA or 5 mM CaCl2 was included throughout the purification, starting from extraction. EDTA was omitted during the steps immediately preceding and during Co2+-TALON purification.

Purification of stink bug Nanchung or Inactive with long AP incubation: Nan-mCherry-FLAG or Iav-mEGFP-6xHis were expressed in HEK293S GnTI- cells from a 250 mL culture at 1 M/mL infected with 6% (v/v) baculovirus and cultured with 10 µM AP for ~1 day at 37 °C. Expression was induced by supplementation with 10 mM Na-Butyrate and the cultures incubated at 30 °C for 48 h with 130 rpm aeration 8% CO2, 100% humidity. Cultures were harvested and resuspended in TBS supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/mL aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, and a small quantity of Bovine DNAse I. AP (1 µM) was maintained throughout the purification. The cell suspension was then sonicated 3 × 30 s on ice, then extracted with 20 mM DDM: 2 mM CHS for 1 h on a rotator at 4 °C. Lysates were clarified at 16,000x rpm, 4 °C for 30 min and incubated for 1.5 h with 0.5 mL anti-FLAG SM2 resin (for Nan) or 0.5 mL Co2+-TALON resin (for Iav). Purification proceeded as above using the respective buffers for FLAG or His purification. Eluents were then concentrated with a 100 kDa MWCO spin concentrator to ~1 OD280, then treated with PreScission protease (PPX) treatment to remove the fluorescent protein and purification tag for 25 min at 4 °C with 1 mM DTT and a 1:10 (w/w) ratio of protease:eluted protein. Samples were then further concentration to <500 µL and further purified on a Superose 6 Increase column equilibrated with 20TBS + 0.02% GDN + 1 µM AP. Peak fractions for Nan+AP were pooled and concentrated to 2.9 mg/mL, then 2% DMSO added for grid freezing.

Purification of stink bug Nanchung with short AP incubation: Nan-mCherry-FLAG was expressed in HEK293S GnTI- cells from a 1.3 L culture at 1 M/mL infected with 3% (v/v) baculovirus and cultured for 1 day at 37 °C. Expression was induced by supplementation with 10 mM Na-Butyrate and the cultures incubated at 25 °C for 48 h with 130 rpm aeration 8% CO2, 100% humidity. Thirty minutes before harvesting 10 µM AP was added, after which cultures were harvested and processed as above, with 1 µM AP maintained throughout the purification. Following sonication, protein was extracted with 1% Digitonin for 1 h on a rotator at 4 °C and clarified lysates incubated for 1.5 h with 1.5 mL anti-FLAG SM2 resin. Purification proceeded as above using the respective buffers for FLAG purification except 0.08% Digitonin was used in place of GDN. Ten CV each of wash buffers 1–3 and 5CV elution buffer were used. Eluents were then concentrated with a 50 kDa MWCO spin concentrator to ~0.2 OD280 then treated with preScission protease treatment to remove the fluorescent protein and purification tag for 1 h at 4 °C with 0.1 mM DTT and a 1:10 (w/w) ratio of protease:eluted protein. Samples were then further concentration to <500 µL and purified on a Superose 6 Increase column equilibrated with 20TBS + 0.08% Digitonin +1 µM AP. Peak fractions for Nan+AP were pooled and concentrated to 2.9 mg/mL then 2% DMSO added for grid freezing.

Sample preparation for cryo-EM

Stink bug Nanchung and Inactive samples: Grids were frozen using an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV set to 8 °C and 100% humidity. Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 300 Cu +2 nM C grids were glow discharged for 30 s in a PELCO EasyGlo glow discharger (0.37 mBar, 15 mA). Sample was then applied to the grid (3 µL), blotted for 8–10 s and plunge frozen in liquid ethane.

Stink bug Nanchung + AP: Grids were frozen using a Leica EM GP2 Plunge Freezer set to 4 °C and 80% humidity. UltrAufoil R1.2/1.3 300 Au grids were glow discharged for 3 min in a PELCO EasyGlo glow discharger (15 mA, 0.39 mBar). A 3 µL aliquot of the sample was incubated on the grid in the chamber for 1 min, blotted for 1.5 s and then plunge frozen in liquid ethane.

Cryo-EM data acquisition and processing

Single particle micrograph images were collected at on a Titan Krios G2 transmission electron microscope (FEI) operated at 300 keV, equipped with a K3 camera and Gatan BioQuantum energy filter set to 20 eV at a pixel size of 1.08 A/pix at the specimen level (nominal magnification of 81,000x) and a gradient of defocus values ranging from −0.8 to −2.2 µm. Movies of 40 frames each were collected using Latitude S (Gatan), with a nominal dose rate of 25 e– px−1 s−1 over 2.4 s exposure to give a total dose of ~60 e– Å−2.

Movies were beam-induced motion corrected and dose-weighted using MotionCor2 in RELION 4.061. Estimation of contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters was estimated in cryoSPARC using patch CTF estimation62. Micrographs exhibiting ≥4 Å CTF fit resolution were rejected from further analysis. Generally, a subset of 500–1000 micrographs was used for blob picking in cryoSPARC and, following curation, several rounds of 2D classification were conducted to obtain clean references for template-based particle picking. Particles were then extracted with a 64-pixel box with 4x binning. Several rounds of 2D classification were conducted to remove junk particle classes. Initial 3D models were reconstructed using ab initio reconstruction and refined using non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. 3D classification in cryoSPARC or RELION was used to classify based on heterogeneity in the ARD. No significant heterogeneity in the membrane domain was observed. Classes were refined with C1 and C2; those exhibiting a higher resolution for C2 were deemed C2 symmetric and imported into RELION for Bayesian polishing. Particles were then transferred back to cryoSPARC for final non-uniform refinement and local refinement. Final resolutions and particle numbers are given in Table 1.

In the case of processing of the Nan+AP pentamer, many attempts were made to improve the resolution of the membrane domain, particularly the pore region, using techniques like signal subtraction and TMD masking. However, these attempts proved unproductive due to what is likely an extremely disordered pore region and heterogenous TMD in general. Final resolution was calculated using an auto-generated mask from non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC, which focused most heavily on the ARD, which was resolved to a much higher resolution than the membrane domain (VSLD in particular).

Model building and refinement

The initial model for the apo stink bug Nanchung and Inactive was built de novo using Coot63 and AlphaFold264 models of stink bug Nan and Iav were used to help confirm low confidence areas. Calmodulin was modeled using rigid body fitting of the Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free models from PDB 4JPZ56 and 1CFD65, respectively. Spherical refinement was used to adjust the models, ensuring correct stereochemistry and good geometries. Phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine were then modeled into clear lipid densities and ligands NAM and AP were placed into their corresponding densities at the tight junctions, with restraint files generated from isomeric SMILES strings using eLBOW in PHENIX66. Models were then subjected to real space refinement in PHENIX with local grid search and global minimization with secondary structure restraints. The MolProbity server was used to guide model refinement and structural analyses and illustrations were performed using PyMOL and UCSF Chimera X67,68,69. For analysis of pore dimensions the HOLE server was used70, and sequence conservation was mapped using the Consurf server71.

Western blot analysis

WT and Iav mutants of Nan-Iav were expressed in 300 mL cultures and purified by a single FLAG purification step, as detailed above. Eluted fractions were concentrated and mixed 1:1 (v/v) with 2X Laemmli sample buffer +5 M Urea, heated to 99 °C for 90 s, then immediately run on SDS-PAGE. Protein was transferred to 0.45 µm PVDF, then blocked with 5% BSA in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl. Membranes were incubated at 4 °C for 48 h with the respective primary antibodies diluted in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20 at 4 °C: rabbit anti-CaM (1:1000) Cell Signaling 4830S (lot: 4); mouse anti-His (1:3000, Invitrogen MA1-21315). After extensive washing, blots were incubated at 25 °C for 1 h with 1:5000 diluted IRDye800CW anti-rabbit (LI-COR 926-32211) or anti-mouse (LI-COR 926-32212) secondary antibodies, respectively. Blots were extensively washed, then imaged on a LiCor Odyssey fluorescence imager.

Electrophysiology

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin. Once cultures in 6-well plates reached ~50–70% confluency, 15%(v/v) baculovirus was added and the cells were incubated for ~18 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 100% humidity. To induce expression, 10 mM Na-butyrate was added, and the cultures were moved to an incubator at 30 °C, 5% CO2, 100% humidity for 2 days of expression. Cells were then seeded onto glass slides and used for electrophysiology recordings the next day. Cells with good expression were identified under fluorescence microscope utilizing GFP and/or mCherry fluorescence. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were done at room temperature (20–22 °C) for activation by nicotinamide (NAM), AP, and inhibition by ruthenium red (RR). Data were acquired with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) and currents were low-pass filtered at 2 kHz and digitally sampled at 5–10 kHz (Digidata 1440 A). Pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass using a P-1000 puller and polished to final resistances between 2 and 4 MΩ (Sutter Instrument). A 90% series resistance compensation was used in all whole-cell recordings. The external solution contained 140 mM NaCl and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The intracellular solution containing 135 mM CsCl, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.4 with CsOH. After breaking the cell membrane, the cell was allowed to equilibrate with the pipette solution for 2 min before recording was carried out. All electrophysiological data analyses were done using Igor Pro 6.2 (Wavemetrics).

Membrane preparation and [3H]-AP binding assay

HEK293S GnTi cells grown in 300 mL suspension culture at a density of 1–1.5 M/mL were infected with 3% (v/v) baculovirus and kept for ~1 day at 37 °C, proceeded by 48 h incubation at 25 °C with 130 rpm aeration and 5% CO2. Cultures were harvested and resuspended in 8 mL of ice-cold 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.3) containing 1% (w/v) protease inhibitor mixture (Halt; Thermo Fisher). Membranes were then prepared by homogenizing the cell suspension by sonication, pelleting debris at 300 × g for 10 min and pelleting of membranes at 50,000 × g for 2 h. The membranes were then resuspended in 0.5 mL of binding buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2) and stored at −80 °C16. Briefly, [3H]-AP binding studies were performed in 96-well U-bottom polypropylene plates13,16. Membranes (100 µL) were resuspended in binding buffer containing Tween-20 (0.0025% final) and [3H]-AP; 200 µL was used for saturation binding and 800 µL for displacement binding experiments, where competing ligands were also included. Per replicate, 60–100 µg of membranes were incubated for 3 h at room temperature. Assay mixtures were then filtered through Multiscreen HTS + 96 Hi Flow FC filters (EMD Millipore) that were pre-treated with 0.1% polyethyleneimine. Filters were then washed thrice with 200 µL of ice-cold binding buffer. Following the addition of scintillation cocktail, radioactivity was measured using a Wallac 1450 Microbeta counter. A 500-fold excess of cold AP was used to obtain non-specific binding signal levels. Ki values (one site) for NAM and AP binding were calculated from the Cheng-Prusoff equation (Eq. 1)72. Where Kd is the determined Kd for [3H]-AP binding, [R] is the concentration of [3H]-AP used (based on the Kd for each mutant), and IC50 is the apparent IC50 from the curve fits, using GraphPad Prism 7.0. [3H]-AP was custom prepared by RC TRITEC AG (Teufen, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Igor Pro 6.2, Excel Office 365, and GraphPad Prism 7.0. All quantitative data are represented as means ± SEM. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed by Student’s two-tailed unpaired t-test. Comparisons among more than two groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. Differences were considered significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, as appropriate. Kd, Ki and their asymmetrical 95% confidence intervals were determined using GraphPad Prism 10.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

For initial model building, calmodulin models PDB 4JPZ, and 1CFD were used. Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes 9NVN (Nan-Iav-CaM in the apo state), 9NVO (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with nicotinamide), 9NVP (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with nicotinamide, EDTA), 9NVQ (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with afidopyropen, with calcium), 9NVR (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with afidopyropen, EDTA), 9NVS (pentameric Nan in complex with afidopyropen). The corresponding cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under the accession codes EMD- 49844 (Nan-Iav-CaM in the apo state), EMD-49845 (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with nicotinamide), EMD-49846 (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with nicotinamide, EDTA), EMD-49847 (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with afidopyropen, with calcium), EMD-49848 (Nan-Iav-CaM in complex with afidopyropen, EDTA), EMD-49849 (pentameric Nan in complex with afidopyropen). Source data for functional assays are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mirzabaev, A. et al. Severe climate change risks to food security and nutrition. Clim. Risk Manag. 39, 100473 (2023).

Hadley, K. et al. Mechanisms underlying food insecurity in the aftermath of climate-related shocks: a systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 7, e242–e250 (2023).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 (FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO, 2024).

Maienfisch, P. & Mangelinckx, I. S. Recent Highlights in the Discovery and Optimization of Crop Protection Products (Academic Press, 2021).

Popp, J., Pető, K. & Nagy, J. Pesticide productivity and food security. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 33, 243–255 (2013).

Savary, S. et al. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 430–439 (2019).

Deutsch, C. A. et al. Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 361, 916–919 (2018).

Ma, C.-S. et al. Climate warming promotes pesticide resistance through expanding overwintering range of a global pest. Nat. Commun. 12, 5351 (2021).

Oerke, E.-C. & Dehne, H.-W. Safeguarding production—losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop Prot. 23, 275–285 (2004).

Wilson, A. L. et al. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0007831 (2020).

Sparks, T. C. et al. Insecticides, biologics and nematicides: updates to IRAC’s mode of action classification—a tool for resistance management. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 167, 104587 (2020).

Raisch, T. & Raunser, S. The modes of action of ion-channel-targeting neurotoxic insecticides: lessons from structural biology. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 1411–1427 (2023).

Nesterov, A. et al. TRP channels in insect stretch receptors as insecticide targets. Neuron 86, 665–671 (2015).

Huang, Z. et al. Insect transient receptor potential vanilloid channels as potential targets of insecticides. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 148, 104899 (2023).

Goto, K. et al. Synthesis and insecticidal efficacy of pyripyropene derivatives. Part II—Invention of afidopyropen. J. Antibiot. 72, 661–681 (2019).

Kandasamy, R. et al. Afidopyropen: new and potent modulator of insect transient receptor potential channels. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 84, 32–39 (2017).

Goto, K. et al. Synthesis of pyripyropene derivatives and their pest-control efficacy. J. Pestic. Sci. 44, 255–263 (2019).

Horikoshi, R. et al. Afidopyropen, a novel insecticide originating from microbial secondary extracts. Sci. Rep. 12, 2827 (2022).

Gong, Z. et al. Two interdependent TRPV channel subunits, inactive and nanchung, mediate hearing in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 24, 9059–9066 (2004).

Matsuura, H., Sokabe, T., Kohno, K., Tominaga, M. & Kadowaki, T. Evolutionary conservation and changes in insect TRP channels. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 228 (2009).

Li, B., Li, S., Zheng, H. & Yan, Z. Nanchung and Inactive define pore properties of the native auditory transduction channel in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2106459118 (2021).

Kavlie, R. G. & Albert, J. T. Chordotonal organs. Curr. Biol. 23, R334–R335 (2013).

Wang, L.-X. et al. Pymetrozine activates TRPV channels of brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 153, 77–86 (2019).

Harrewijn, P. & Kayser, H. Pymetrozine, a fast-acting and selective inhibitor of aphid feeding. In situ studies with electronic monitoring of feeding behaviour. Pestic. Sci. 49, 130–140 (1997).

Upadhyay, A. et al. Nicotinamide is an endogenous agonist for a C. elegans TRPV OSM-9 and OCR-4 channel. Nat. Commun. 7, 13135 (2016).

Sattar, S., Martinez, M. T., Ruiz, A. F., Hanna-Rose, W. & Thompson, G. A. Nicotinamide inhibits aphid fecundity and impacts survival. Sci. Rep. 9, 19709 (2019).

Hadiatullah, H. et al. Recent progress in the structural study of ion channels as insecticide targets. Insect Sci. 29, 1522–1551 (2022).

Shen, H. et al. Structural basis for the modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels by animal toxins. Science 362, eaau2596 (2018).

Raisch, T. et al. Small molecule modulation of the Drosophila Slo channel elucidated by cryo-EM. Nat. Commun. 12, 7164 (2021).

Valentin, R. E., Nielsen, A. L., Wiman, N. G., Lee, D.-H. & Fonseca, D. M. Global invasion network of the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys. Sci. Rep. 7, 9866 (2017).

Zubcevic, L. et al. Conformational ensemble of the human TRPV3 ion channel. Nat. Commun. 9, 4773 (2018).

Kwon, D. H. et al. Heat-dependent opening of TRPV1 in the presence of capsaicin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28, 554–563 (2021).

Singh, A. K., Saotome, K., McGoldrick, L. L. & Sobolevsky, A. I. Structural bases of TRP channel TRPV6 allosteric modulation by 2-APB. Nat. Commun. 9, 2465 (2018).

Kwon, D. H. et al. TRPV4-Rho GTPase complex structures reveal mechanisms of gating and disease. Nat. Commun. 14, 3732 (2023).

Pumroy, R. A. et al. Structural insights into TRPV2 activation by small molecules. Nat. Commun. 13, 2334 (2022).

Zubcevic, L., Borschel, W. F., Hsu, A. L., Borgnia, M. J. & Lee, S.-Y. Regulatory switch at the cytoplasmic interface controls TRPV channel gating. eLife 8, e47746 (2019).

Nadezhdin, K. D. et al. TRPV3 activation by different agonists accompanied by lipid dissociation from the vanilloid site. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn2453 (2024).

Kwon, D. H., Zhang, F., Fedor, J. G., Suo, Y. & Lee, S.-Y. Vanilloid-dependent TRPV1 opening trajectory from cryoEM ensemble analysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 2874 (2022).

Yin, Y. et al. Molecular basis of neurosteroid and anticonvulsant regulation of TRPM3. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 32, 828–840 (2025).

Pumroy, R. A. et al. Molecular mechanism of TRPV2 channel modulation by cannabidiol. eLife 8, e48792 (2019).

Zubcevic, L. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the TRPV2 ion channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 180–186 (2016).

Won, J. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the heteromeric TRPC1/TRPC4 channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 32, 326–338 (2025).

Su, Q. et al. Structure of the human PKD1-PKD2 complex. Science 361, eaat9819 (2018).

Rocereta, J. A. et al. Structural insights into TRPV2 modulation by probenecid. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 32, 1019–1029 (2025).

Lansky, S. et al. A pentameric TRPV3 channel with a dilated pore. Nature 621, 206–214 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Drosophila hygrosensation requires the TRP channels water witch and nanchung. Nature 450, 294–298 (2007).

Kandasamy, R., Costea, P. I., Stam, L. & Nesterov, A. TRPV channel nanchung and TRPA channel water witch form insecticide-activated complexes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 149, 103835 (2022).

Wong, C.-O. et al. A TRPV channel in Drosophila motor neurons regulates presynaptic resting Ca2+ Levels, synapse growth, and synaptic transmission. Neuron 84, 764–777 (2014).

Liu, X. et al. Persistent toxicity and dissipation dynamics of afidopyropen against the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer) in cabbage and chili. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 252, 114584 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of afidopyropen on biological traits of the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sluzer). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 180, 104981 (2022).

Song, X.-Y. et al. Resistance monitoring of nilaparvata lugens to pymetrozine based on reproductive behavior. Insects 14, 428 (2023).

Andrews, C., Xu, Y., Kirberger, M. & Yang, J. J. Structural aspects and prediction of calmodulin-binding proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 308 (2020).

Yelshanskaya, M. V., Nadezhdin, K. D., Kurnikova, M. G. & Sobolevsky, A. I. Structure and function of the calcium-selective TRP channel TRPV6. J. Physiol. 599, 2673–2697 (2021).

Dang, S. et al. Structural insight into TRPV5 channel function and modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 8869–8878 (2019).

Pitt, G. S. & Lee, S.-Y. Current view on regulation of voltage-gated sodium channels by calcium and auxiliary proteins. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 25, 1573–1584 (2016).

Wang, C. et al. Structural analyses of Ca2+/CaM interaction with NaV channel C-termini reveal mechanisms of calcium-dependent regulation. Nat. Commun. 5, 4896 (2014).

Wang, C., Chung, B. C., Yan, H., Lee, S.-Y. & Pitt, G. S. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of a NaV C-terminal domain, a fibroblast growth factor homologous factor, and calmodulin. Structure 20, 1167–1176 (2012).

Fornwald, J. A., Lu, Q., Wang, D. & Ames, R. S. Gene expression in mammalian cells using BacMam, a modified baculovirus system. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 388, 95–114 (2007).

Wang, Y., Wang, F., Wang, R., Zhao, P. & Xia, Q. 2A self-cleaving peptide-based multi-gene expression system in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Sci. Rep. 5, 16273 (2015).

Morales-Perez, C. L., Noviello, C. M. & Hibbs, R. E. Manipulation of subunit stoichiometry in heteromeric membrane proteins. Structure 24, 797–805 (2016).

Zivanov, J. et al. A Bayesian approach to single-particle electron cryo-tomography in RELION-4.0. eLife 11, e83724 (2022).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold | Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03819-2.

Kuboniwa, H. et al. Solution structure of calcium-free calmodulin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 768–776 (1995).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Struct. Biol. 75, 861–877 (2019).

MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation - Williams - 2018 - Protein Science - Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/doi/10.1002/pro.3330.

DeLano, W. L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, 2002).

UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis - Meng - 2023 - Protein Science - Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.lib.duke.edu/doi/full/10.1002/pro.4792.

Smart, O. S., Neduvelil, J. G., Wang, X., Wallace, B. A. & Sansom, M. S. P. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 354–360 (1996).

Celniker, G. et al. ConSurf: using evolutionary data to raise testable hypotheses about protein function. Isr. J. Chem. 53, 199–206 (2013).

Newton, P., Harrison, P. & Clulow, S. A novel method for determination of the affinity of protein: protein interactions in homogeneous assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 13, 674–682 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Cryo-EM data were screened and collected at the Duke University Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (SMIF). We thank Nilakshee Bhattacharya at SMIF for assistance with the microscope operation. We thank Thomas Gurganus for his contributions on tissue culture and protein expression work. This research was supported by BASF and a National Institutes of Health grant R35NS132231 (S.Y.L.). DUKE SMIF is affiliated with the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network, which is in part supported by the NSF (ECCS-2025064).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G.F. conducted biochemical preparation, sample freezing, grid screening, single-particle 3D reconstruction, Y.S. collected data and helped with data processing, and C.-G.P. performed electrophysiological characterization, all under the guidance of S.-Y.L., S.-Y.L., and J.G.F. performed model building and refinement. R.K. carried out radioactive tracer binding assays. A.N. coordinated the Duke-BASF collaboration and guided R.K. in conducting biochemical characterizations and contributed to scientific discussions. M.W. provided computational chemistry analyses. N.R. provided project management and strategic steering, and contributed to scientific discussions. J.G.F. and S.-Y.L. wrote the paper with input from the rest of the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Theodore Wensel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fedor, J.G., Kandasamy, R., Park, CG. et al. Visualizing insecticide control of insect TRP channel function and assembly. Nat Commun 17, 595 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67287-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67287-2