Abstract

Flight trajectory prediction is a fundamental task in air traffic control. While our previous WTFTP framework leveraged wavelet-based time-frequency analysis for trajectory prediction, its iterative single-horizon paradigm suffers from error accumulation in long-horizon forecasts. Here, the WTFTP+ framework is proposed to enhance multi-horizon prediction performance while further exploring the potential of time-frequency analysis in flight trajectory prediction tasks. An encoder-decoder neural architecture is designed to generate wavelet components of predicted trajectories, where a direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm is employed to mitigate the cumulative errors of the WTFTP. Additionally, a time-frequency bridging mechanism is proposed to explore intrinsic correlations among multi-scale flight patterns to enhance the learning ability of wavelet components. Experiments on real-world datasets demonstrate that WTFTP+ not only retains the superior single-horizon prediction performance of WTFTP but also significantly improves multi-horizon prediction accuracy, achieving over 40% mean deviation error reduction at the 5-minute horizon compared with WTFTP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The aviation industry has undergone significant growth over the past few decades, with global passenger traffic reaching 8.7 billion in 2023. The increasing flights are providing heightened complexity to current air traffic control (ATC) systems1. To ensure operational safety and efficiency in congested airspace, trajectory-based operations (TBO) have emerged as a promising solution in future ATC frameworks, exemplified by initiatives such as the next generation air transportation system (NextGen) in the United States and the Single European Sky ATM Research (SESAR) in Europe2. Unlike existing ATC systems that rely on pre-assigned static flight routes, TBO focuses on dynamic, real-time trajectory planning via precise trajectory prediction and sharing to adapt to evolving airspace conditions. As a fundamental technique of the TBO, flight trajectory prediction (FTP) has attracted significant attention from both academic researchers and industry practitioners3,4,5.

Accurate FTP plays a pivotal role in ATC systems by enhancing coordination, optimizing airspace management, and improving decision-making in real-time ATC operations6,7,8,9,10. In recent years, FTP methods were implemented by well-designed technical frameworks, from traditional physical modeling to state-of-the-art deep learning techniques. Specifically, early FTP methods generally depended on physics-based models with aerodynamics and kinematics equations to capture the motion dynamics of aircraft11,12,13. Subsequently, filter-based FTP methods were proposed to refine predictions through iterative updates based on observed positions by particle filters14, Kalman filters15,16, etc. Although these methods achieved the desired performance improvements, they still struggle to capture transition patterns due to the high dependency on dynamic models and are prone to error accumulation over extended future horizons, thereby limiting their multi-horizon prediction capability. With the development of artificial intelligence techniques17,18, data-driven methods have emerged as primary approaches for FTP modeling, which learns complex transition patterns and temporal-spatial dependencies by fitting large-scale historical trajectory data19, and finally enable more accurate and adaptive trajectory predictions in various conditions20,21,22,23,24. Nevertheless, most existing data-driven FTP methods primarily focus on advancing temporal-spatial modeling techniques, while often overlooking the exploration of the frequency domain. The inability to model time-frequency patterns inevitably impairs performance in relatively high maneuver scenarios.

In our previous work22, a wavelet transform-based flight trajectory prediction (WTFTP) framework is proposed to tackle the single-horizon FTP tasks, which leverages time-frequency analysis to capture global flight trends and local motion details represented by wavelet components (WTCs). The descriptions of the time-frequency analysis and WTCs can be found in Supplementary Information (Section “Multi-resolution analysis”). Thanks to the time-frequency perspective for the transition modeling of flight trajectory, the WTFTP achieved significant performance improvements in various ATC scenarios, especially during the critical maneuver flight phase. As analyzed in the discussion, the WTFTP still suffers from a performance degradation in multi-horizon prediction due to the iterative prediction paradigm. It is believed that the following two issues are the key to further improving the performance and applicability of time-frequency analysis in the FTP tasks:

-

As a single-horizon prediction framework, the performance of the WTFTP is limited by larger error accumulation in multi-horizon prediction, providing only inferior applicability in real-world ATC operations. Specifically, the WTFTP performs the multi-horizon prediction in an iterative manner, where the previous predictions are regarded as pseudo observations to forecast trajectory sequences over an extended time horizon. The pseudo observations inevitably introduce substantial cumulative errors with horizon-wise propagations and further impact the prediction of high-frequency wavelet components, thereby degrading the accuracy of multi-horizon predictions.

-

In general, the WTFTP utilizes an encoder-decoder architecture to estimate multi-scale wavelet coefficients to support the FTP task, in which multiple decoders are dedicatedly designed to perform the learning process corresponding to multiple wavelet scales. Considering the orthogonality of the approximation subspace of wavelet components, each decoder performs an independent prediction process without desired feature interaction. A detailed description of the orthogonal space formulation under multi-scale analysis is provided in Supplementary Information (Section “Multi-resolution analysis”). However, in real-world scenarios, flight transition patterns are tightly coupled with inherent dependencies (e.g., driven by a turning maneuver, the trajectory may present a flight trend generally shifting from one direction to another from a macro perspective). It is believed that rigorous mathematical assumptions of orthogonality may hinder performance in the FTP tasks, since the lack of interaction of multi-scale wavelet components ignores the essential inherent dependencies within flight patterns across different time-frequency scales.

To address the mentioned limitations, in this work, an FTP framework, called WTFTP+, is proposed to improve the previous WTFTP framework to enhance multi-horizon FTP performance. The WTFTP+ retains the core concept of time-frequency analysis from the WTFTP framework, i.e., generating the optimal wavelet coefficients based on the observations and constructing the future trajectory sequence using inverse discrete wavelet transform (IDWT) operation. In this paradigm, the WTFTP+ framework not only can fully exploit the advantages of the time-frequency modeling technique but also is able to mitigate the error accumulation problem in multi-horizon prediction scenarios.

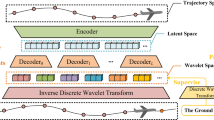

As depicted in Fig. 1, to mitigate the problem of error accumulation of the iterative multi-horizon prediction, the WTFTP+ is designed in a direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm with a generalized encoder-decoder architecture. The encoder is applied to extract the temporal-spatial features from the observed trajectory sequence, while the decoder is used to generate the optimal wavelet coefficients for the predicted horizons. The improved Transformer-style neural network serves as the backbone of the WTFTP+ framework to facilitate the time-frequency domain interaction.

The WTFTP+ framework is implemented with an encoder-decoder architecture, in which the encoder is employed to extract the abstract features from the observed trajectory sequence, while the decoder is applied to generate the optimal wavelet coefficients for the predicted horizons. In the decoder, to avoid breaking orthogonality of multi-scale wavelet components, the orthogonal wavelet components are first bridged into the time domain for promotive interaction, and subsequently bridged back into the wavelet domain to obtain enhanced features of inherent dependencies within multi-scale flight patterns.

Unlike the multiple decoders in the WTFTP framework, the WTFTP+ is designed with a single-decoder architecture, where the scale-aware wavelet component decoder (SAWCD) is proposed to generate predictions by considering the underlying correlations among the multi-scale flight patterns. Specifically, to obtain the required feature interaction, as well as retain the component orthogonality, a time-frequency bridging mechanism is proposed to support the learning of the multi-scale wavelet coefficients, in which wavelet-domain-to-time-domain (W2T) and time-domain-to-wavelet-domain (T2W) blocks with the learnable transform matrices are proposed to bridge the domain gap. In addition, a cross-domain attention (CDA) mechanism is designed to establish the underlying correlations between observations and the predictions. The above two mechanisms are expected to simultaneously learn the flight transition patterns from both the time and frequency domains, thereby improving the overall performance of FTP tasks.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed WTFTP+ framework, experiments are conducted on a real-world flight trajectory dataset collected from an industrial ATC system. Furthermore, several competitive baselines are also selected to provide a comprehensive evaluation and comparison. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework outperforms the baselines across nearly all prediction horizons and evaluation metrics. Notably, WTFTP+ achieves approximately a 40% relative reduction in mean deviation error (MDE) for the 5-min prediction horizon compared to the previous WTFTP framework. All the proposed technique improvements are confirmed by extensive ablation studies. Most importantly, intuitive visualizations and in-depth analyses are conducted to investigate the interpretability and generalizability of the proposed WTFTP+ framework. It is believed that the proposed WTFTP+ framework not only broadens the scope of the time-frequency analysis for FTP modeling but also provides a powerful and practical tool for the modern ATC systems and downstream applications. In summary, the proposed WTFTP+ framework contributes to the FTP research in the following ways:

-

Based on the previous WTFTP work, an enhanced framework called WTFTP+ is proposed to achieve the multi-horizon FTP task by employing a direct prediction paradigm, which effectively addresses the error accumulation in long-horizon predictions.

-

A Transformer-based encoder-decoder neural architecture is proposed to obtain expected wavelet coefficients, in which a SAWCD is designed to perform feature extraction towards intra-scale (i.e., within a certain scale) flight patterns while capturing the inherent correlations of inter-scale (i.e., among different scales) flight patterns.

-

The time-frequency bridging mechanism is designed in the SAWCD to enable bidirectional transforms of multi-scale representations across wavelet and time domains, as well as capture inter-scale intrinsic dependencies through the time domain interaction.

-

Extensive experiments conducted on a real-world trajectory dataset demonstrate that the proposed WTFTP+ framework outperforms competitive baselines. The results further validate the effectiveness of the proposed direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm and the time-frequency bridging mechanism in enhancing FTP performance.

Results

Problem definition

In general, the short-term FTP tasks can be formulated as temporal-spatial sequential modeling problems, which aim to predict the flight status over a few minutes based on observations. Let the trajectory sequence \(\{{{{\bf{P}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}| i=N-M,N-M+1,\cdots \,,N-1\}\) represent the past M observations, where each trajectory point Pi consists of six attributes:

where Lon, Lat, and Alt correspond to the longitude, latitude, and altitude, respectively, while Vx, Vy, and Vz denote the velocities along the longitudinal, latitudinal, and vertical directions.

The single-horizon FTP methods aim to estimate the state of the trajectory point at the next time step, which can be described as:

where fs(⋅) denotes the single-horizon FTP model, and \({\hat{{{\bf{P}}}}}_{N}\) represents the predicted trajectory point at the next time step. For H-step horizon prediction tasks, existing single-horizon methods typically employ an iterative approach, where previous predicted values are recursively used as pseudo observations for subsequent predictions, which can be formulated as follows:

It is clear that the single-horizon FTP methods suffer from error accumulations and low efficiency for multi-horizon predictions scenarios. Therefore, the WTFTP+ is designed as a direct multi-horizon FTP model to further improve both prediction accuracy and inference efficiency. To be specific, the direct multi-horizon FTP method outputs the trajectory states over the entire H-step prediction horizon in a single inference process, which can be described as:

where the fm(⋅) represents the direct multi-horizon FTP model.

Dataset and evaluation metrics

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, a real-world dataset19 collected from an industrial ATC system in China is applied to train and evaluate the proposed WTFTP+ framework. The dataset covers the period from February 19 to February 27, 2021, with 20-second intervals, and the regions of interest are [94.616°, 113.689°], [19.305°, 37.275°], [0, 12500] meters for longitude, latitude, and altitude, respectively. The first 7 days of data serve as the training set, while the data from the 8th and 9th days are for the validation and test. It is noted that the mentioned data splits are applied to all experiments to ensure experimental fairness.

During the model evaluation, 4 metrics are applied to measure the FTP performance, including mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root of mean square error (RMSE), and MDE. Specifically, the MAE, MAPE, and RMSE are standard metrics to evaluate the performance for each trajectory attribute separately. The MDE metric is introduced to measure the distance in nautical mile (NM) between predicted and ground truth trajectory points in three-dimensional (3D) earth space. Moreover, considering the real-time requirements of practical ATC systems, the mean time cost (MTC) metric is introduced to evaluate the computational efficiency of models in multi-horizon prediction scenarios. The detailed definitions of these metrics can be found in our previous work23,25.

Comparison methods

In this work, a total of 7 competitive baselines with diverse technical frameworks are selected to validate the effectiveness of the proposed WTFTP+ framework, as listed below:

-

Kalman filter: a classical recursive state estimation algorithm that predicts and corrects flight states by integrating historical observations with system dynamics models15.

-

CNN-LSTM: a recurrent neural network-based FTP model, in which one-dimensional convolution kernel is employed to extract the trajectory point embeddings, and long short-term memory (LSTM) network is applied to capture the temporal dependencies, implemented by referring to26.

-

FlightBERT: an FTP framework that proposes the binary encoding to represent the trajectory attributes and converts the FTP task into a multi-binary classification problem4.

-

WTFTP: a time-frequency analysis based FTP framework proposed in our previous work, which validates the effectiveness of wavelet analysis in the FTP tasks22.

-

Attn-LSTM: a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) LSTM network that utilizes an attention mechanism to predict multiple future time steps directly27.

-

TD-Transformer: a Transformer network that directly predicts the multi-horizon trajectory in an autoregressive manner. In addition, a trend decomposition (TD) strategy28 is applied to enhance the model performance.

-

FlightBERT++: an enhanced FTP framework of the FlightBERT, which addresses the limitations of high-bit misclassifications errors23.

Based on the inference style of the multi-horizon prediction, the baselines are further categorized into iterative prediction models (Kalman filter, CNN-LSTM, FlightBERT, WTFTP) and direct prediction models (Attn-LSTM, TD-Transformer, and FlightBERT++). Iterative prediction models perform one-step prediction in an inference procedure, where the predicted results are used as pseudo observations to iteratively obtain multi-horizon predictions. In contrast, the direct prediction models generate multi-horizon prediction results in a single inference pass.

Experimental configuration

The trajectory encoder consists of 4 Transformer encoder layers, while 2 improved Transformer decoder (ITD) layers are applied to construct the SAWCD. The hidden state dimension is set to 128 for both the trajectory encoder and the SAWCD. The multi-head attention mechanism is utilized for the trajectory encoder and the SAWCD to enhance the feature extraction ability of the model, in which the number of attention heads is set to 4. The level of wavelet analysis is 4, using the Haar wavelet basis with a filter length of 2. The symmetric extension is selected to ensure continuity at the boundaries of the trajectory. The L2 regularization weight in the loss function is set to 1 × 10−4 to ensure consistency with the magnitude of the wavelet component loss.

For the FlightBERT and FlightBERT++ baselines, experimental configurations follow the original works4,23. As to remaining baselines and the proposed WTFTP+ framework, the z-score normalization is applied to longitude and latitude attributes to address their sparse distributions, while other attributes are normalized to the [0, 1] range using the min-max method. In the training process, the batch size is set to 1024, and the number of training epochs is 150. The Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 10−3 is used to train all deep learning models.

All experiments are implemented using the open-source deep learning framework PyTorch 1.9.0. The models are trained on a server with an Ubuntu 16.04 operating system, 8 NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 GPUs, an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-7820X @ 3.6 GHz CPU, and 128 GB of memory.

Overall results and quantitative analysis

Table 1 presents the overall prediction performance of the WTFTP+ framework and other baseline models, with the predictions for 1-, 3-, 9-, and 15-step horizons (corresponding to 20 s, and 1, 3, 5 min) reported in terms of the four mentioned FTP metrics. In general, predictions for 1- and 3-step horizons reflect short-horizon prediction accuracy, while those for 9- and 15-step horizons demonstrate the ability to capture long-range dependencies. From the proposed evaluation metrics, the WTFTP+ framework outperforms the baseline models across almost all prediction horizons. Specifically, the WTFTP+ shows significant improvements in the MDE metric, obtaining approximately 26%, 22%, and 13% reduction relative to the best baseline (FlightBERT++) for 1-, 3-, and 9-step horizons, respectively, and achieving comparable performance for 15-step horizon. The following key conclusions can be drawn from the results:

-

(1)

For the multi-horizon FTP task, direct prediction methods significantly outperform their iterative counterparts. Although the Attn-LSTM model shows inferior performance compared to other direct prediction methods for 9- and 15-step horizons, it still effectively captures long-range dependencies in flight trajectories. Compared to the best iterative prediction method (FlightBERT), Attn-LSTM achieves approximately 14% and 25% MDE reduction for 9- and 15-step horizons, respectively, also outperforming in other metrics. In contrast, the iterative prediction methods suffer from substantial noise by using the prediction results as pseudo observations29,30, leading to considerable error accumulation as the prediction horizon increases. By considering the previous prediction as pseudo observations, due to the fixed input length, more collected trajectory points will be removed from the input sequence, thereby diminishing prior knowledge and further degrading performance. Therefore, the WTFTP+ framework is implemented in a direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm and achieves an expected performance improvement. Most importantly, the WTFTP+ addresses the limitations of the WTFTP framework, which supports our motivation in this work and provides a promising time-frequency analysis solution for the FTP task.

-

(2)

For iterative prediction methods, the time-frequency analysis-based model (WTFTP) achieves superior short-horizon prediction accuracy compared to other models, while the FlightBERT obtains the best performance for 9- and 15-step horizons. Specifically, WTFTP focuses on capturing multi-scale transition patterns from observed trajectories and predicting short-horizon trajectory transition, which validates the effectiveness and efficiency of the time-frequency analysis in the FTP task, as outlined in previous work22. However, the pseudo observations during the iterative prediction impact the ability of WTFTP to predict high-frequency wavelet components, leading to the performance degradation over longer prediction horizons. Benefiting from the capability of the Transformer in capturing long-range dependencies as well as binary encoding, FlightBERT achieves the best performance at longer predictions. However, FlightBERT fails to capture overall trends and fine-grained local details, which limits its performance in short-horizon predictions. In addition, the Kalman filter-based FTP method only obtains inferior performance, especially facing longer prediction horizon scenarios, because it relies solely on pseudo observations without real collected measurement updates during the iterative prediction process.

-

(3)

As to direct prediction methods, WTFTP+ not only achieves a higher performance in short horizons but also outperforms other baseline models at long horizons. TD-Transformer generally outperforms the Attn-LSTM in terms of almost all evaluation metrics, which confirms that the Transformer-based models are more effective in capturing long-range dependencies than the LSTM architecture. Benefiting from the differential prediction mechanism and non-autoregressive inference architecture, FlightBERT++ mitigates high-bit misclassifications and achieves substantial performance improvements over FlightBERT. Although obtaining comparable performance to WTFTP+ for 15-step horizon, FlightBERT++ still exhibits an obvious performance gap for 1-, 3-, 9-, and 15-step horizons, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed WTFTP+ framework. WTFTP+ exhibits slightly higher RMSE in the altitude dimension, primarily due to the limited adaptability of unified time-frequency modeling to the distinct variation patterns of altitude compared with longitude and latitude (see Discussion). In addition, FlightBERT++ achieves marginally better MAPE at the 15-step horizon, which can be attributed to its tendency to focus on long-term trend modeling. In contrast, WTFTP+ consistently achieves lower absolute errors and spatial deviations across most horizons and demonstrates a balanced capability in both short- and long-term prediction, which aligns with our motivation of leveraging wavelet analysis to capture both local details and global trends.

-

(4)

Based on the time-frequency analysis capabilities derived from the WTFTP framework, WTFTP+ significantly enhances the ability to capture multi-scale flight patterns in long-range scenario, and finally reaches a state-of-the-art performance for the FTP task in this dataset. As illustrated in Table 1, WTFTP+ achieves relative error reductions of approximately 40% and 34% for 1- and 15-step horizons, respectively. It is believed that the performance improvements can be attributed that: On the one hand, WTFTP+ utilizes the direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm to address the error accumulation of the WTFTP. On the other hand, the proposed time-frequency bridging mechanism promotes the feature extraction and interaction towards multi-scale flight patterns and enables inherent correlations to enhance the trajectory prediction. By combining the mentioned two improvements, the WTFTP+ harvests the higher prediction performance across multiple prediction horizons in the proposed metrics.

In summary, the experimental results demonstrate that time-frequency analysis not only facilitates higher prediction performance in single-horizon scenarios but also enables effective multi-horizon FTP tasks. As an enhancement of the WTFTP framework, WTFTP+ addresses error accumulation and orthogonality challenges by incorporating a direct prediction paradigm and a time-frequency bridging mechanism, which enable the WTFTP+ framework to better leverage time-frequency analysis to improve the FTP performance.

Evaluation across different flight phases

In ATC, flight trajectories are typically divided into different phases: takeoff/climb, cruise, and approach/descent. In general, the FTP task for the takeoff/climb and approach/descent phases are more challenging due to external factors such as control instructions and airspace congestion. Furthermore, according to the Global Flight Accident Report31 issued by the Federal Aviation Administration, takeoff/climb and approach/descent phases account for 21% and 46% of total accidents, respectively, whereas the cruise phase accounts for only 9%. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate the prediction performance across different flight phases to validate the reliability of the proposed WTFTP+ framework for real-world applications.

In this section, the flight trajectories in the test set are further split into trajectory segments according to the above three flight phases, and the best baseline FlightBERT++ in the direct multi-horizon prediction methods serves as the comparison. Table 2 presents the prediction performance of two methods across three flight phases. The results indicate that WTFTP+ demonstrates superior performance by outperforming FlightBERT++ in the MDE metric across almost all prediction horizons. Specifically, both WTFTP+ and FlightBERT++ exhibit a higher prediction accuracy during the cruise phase compared to the maneuvering phases (takeoff/climb and descent/approach). It can be attributed that the complex transition patterns in both horizontal and vertical dimensions during maneuvering phases that result in additional challenges for the FTP task. Fortunately, WTFTP+ achieves notable performance improvements during these maneuvering phases over FlightBERT++, benefiting from time-frequency analysis in modeling multi-scale flight patterns. By leveraging time-frequency analysis, the WTFTP+ framework captures global and local transition patterns in different scales. In addition, the time-frequency bridging mechanism enhances inherent dependencies of inter-scale patterns, and the direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm further contributes to the prediction performance in multi-horizon scenarios. Therefore, WTFTP+ is able to learn trajectory transition during maneuvering phases and providing high-confidence predictions for real-world ATC operations. In summary, through an analysis of performance across different flight phases, it can be concluded that the WTFTP+ framework not only retains the single-horizon prediction advantages of the WTFTP framework but also harvests superior performance in multi-horizon scenarios by integrating a time-frequency bridging mechanism and a direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm.

Visualization and qualitative analysis

To intuitively demonstrate the prediction performance of the WTFTP+ framework and other selective baselines, as shown in Fig. 2, a total of 4 representative flight trajectories are selected from the test set to perform the visualization of the predicted trajectories in both 3D space and the two-dimensional (2D) plane (i.e., latitude-longitude horizon). The selected trajectories concern common flight phases (such as climb, descent, and turns) and complex maneuvering scenarios (such as the coupling of descent and turns). In the 3D visualizations, the altitude is measured in 10 meters. Based on the analysis of these visualizations, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

The WTFTP+ framework achieves higher visualized predictions in both common and complex flight scenarios. In climb and descent scenarios, the WTFTP+ provides excellent prediction accuracy for latitude and longitude, as well as effectively captures transition trends in the altitude dimension. For instance, as the common descent and climb trajectory with relatively simple transition patterns in Fig. 2a, b, e, f, the WTFTP+ and most baseline methods can achieve the desired performance (overlapped to the ground truth) due to the simple motion patterns, but prediction deviations from the ground truth can be gradually observed for longer prediction horizons in certain baselines. The FlightBERT++ (best baseline) still suffers from similar issues, i.e., short-horizon deviations directly affect subsequent trajectory predictions, even if the designed differential binary mechanism can mitigate high-bit misclassification errors. Similar to the quantitative analysis, the Kalman filter-based method exhibits larger error accumulation at longer horizons without real-time observations. In contrast, for more complex flight scenarios, such as the coupled descent and right-turn case during the approach phase shown in Fig. 2c, d, it can be seen that the WTFTP+ framework significantly outperforms other baselines in the visualization results. Except for the CNN-LSTM, Kalman filter, and WTFTP affected by error accumulation, other baseline models can only capture long-term and turn-right trends but fail to accurately predict the latitude-longitude transition during the descent phase. Although the deviations occurred in the last 6-step prediction horizons, the WTFTP+ provides the best performance, i.e., superior latitude-longitude prediction capabilities and comparable altitude prediction accuracy, which also validates the motivation of the time-frequency analysis in this work.

-

(2)

As the prediction horizon increases, direct multi-horizon prediction methods demonstrate higher learning capabilities for long-range dependency compared to iterative multi-horizon prediction methods, as that of the quantitative results in Table 2. For instance, the iterative WTFTP and CNN-LSTM frameworks show significant prediction errors from the ground truth at longer horizons, as illustrated in step 4 of Fig. 2b, step 7 of Fig. 2d, and step 5 of Fig. 2f. Even the FlightBERT, which achieves the best multi-horizon performance among iterative methods, still suffers from considerable prediction deviations in long-horizon predictions, such as step 5 of Fig. 2h. It can be also observed that the performance limitations of iterative multi-horizon methods are deteriorated in altitude prediction. In contrast, direct multi-horizon prediction methods obtain higher prediction accuracy, which can be attributed that its unique prediction paradigm to mitigate error accumulation and sufficient modeling towards the entire historical prior information to enhance prediction robustness. It is also noted that the direct multi-horizon prediction methods only obtain marginal performance improvement in short-horizon prediction accuracy, particularly within 3 steps, whereas the WTFTP+ framework achieves both desired multi-horizon prediction performance and reliable short-horizon forecasting confidence, as concluded in the quantitative analysis of Section “Overall results and quantitative analysis”.

a, b 3D and 2D visualization for descending scenario. c, d 3D and 2D visualization for descending and turn right scenario. e, f 3D and 2D visualization for climbing scenario. g, h 3D and 2D visualization for turn right scenario. It is noted that, since the Kalman filter-based FTP method suffers from significant error accumulations in the descending and turn right scenario, its results are not displayed in (c, d) for better visualization and comparison. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Computational performance

To further evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed WTFTP+ framework, Fig. 3 presents the model parameters and computational efficiency of WTFTP+ and selected data-driven baseline models. The vertical axis is log-scaled to improve readability and distinguishability. To ensure the comparison fairness, the batch size and prediction horizons is fixed to 1 and 15 for all models, respectively.

Although the Kalman filter-based FTP method achieves superior MTC performance (0.64 ms), its prediction error rapidly propagates to reduce the performance as the prediction horizon increases (as shown in Table 1), which demonstrates its inapplicability for long-horizon prediction scenarios. Except for FlightBERT and FlightBERT++, the number of model parameters of all models is maintained within the order of millions. Although FlightBERT++ adopts a non-autoregressive prediction mechanism and obtains a faster inference speed, it still requires additional computational overhead for the binary encoding process in practice. Prior works have reported that the average visual reaction time of air traffic controllers can reach up to 170 ms32. Therefore, all FTP models except FlightBERT can meet real-time operational requirements. The slower performance of FlightBERT is primarily due to its base transformation of trajectory attributes, which further burdens computational overhead during iterative multi-horizon prediction. Compared with the WTFTP framework, WTFTP+ removes the multi-decoder structure but increases the latent feature dimensionality and incorporates a Transformer-style backbone, thereby resulting in larger trainable parameters than that of the WTFTP framework. Fortunately, the proposed WTFTP+ follows a direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm, achieving 15-step predictions within 24 ms even under four-level wavelet decomposition. In summary, considering both the model parameters and MTC measurement, WTFTP+ achieves a favorable balance between model complexity and computational efficiency, while maintaining superior prediction accuracy and robustness across multi-horizon prediction scenarios. The results indicate that the WTFTP+ is a promising solution for the real-world operational ATC systems, further supporting real-time downstream applications, such as conflict detection and decision-making.

Case study

Unlike the previous WTFTP, the WTCs generated by the WTFTP+ are applied to obtain only the predicted trajectory sequence without reconstructing the observed trajectory sequence. Considering the multi-scale feature analysis described in our previous work22, a flight trajectory with climbing and right-turning is selected to analyze flight trends and motion details represented by WTCs and intuitively correlate multi-scale flight patterns. Since the length of the low-frequency component is one in the 4th level of wavelet analysis, only the 1–3 levels of wavelet components are presented in Fig. 4. Figure 4k displays the flight profile of the WTFTP+ and selected baselines. Figure 4a–i show horizon-plane flight patterns derived from different WTCs. Specifically, y-axis label indicates the longitude (Lon) or latitude (Lat) transition pattern at certain wavelet scales \({\{H{i}_{i}\}}_{i\in [1,3]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) represents the case of motion details at the i-th level of wavelet analysis, while Lo3, Lo0 are flight trend and time-domain trajectory, respectively.

a, b The ground truth and predicted trajectory along the longitude and the latitude, respectively. c–j Trends and details illustrated by multi-scale WTCs in the WTFTP+ framework, which are obtained by the IDWT procedure of the involved WTCs (the involved one is indicated in parentheses of y-axis label. Not involved ones will be replaced by zeros). x-axis represents time steps. k The selected trajectory in the 3D earth space. Since the Kalman filter-based FTP method suffers from significant error accumulations, its results are not displayed for better visualization. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

As illustrated in Fig. 4k, a predominant northeastward flight trend (i.e., increasing latitude and longitude) is presented within 3 steps of prediction horizon, while steps 4–6 capture the local motion details of a right turn. The subsequent 6 steps maintain an approximate southeastward flight trend. From step 13, the aircraft performs a deceleration accompanied by a right turn, resulting in a heading shift toward the southwest. Meanwhile, the altitude of the aircraft is gradually increasing throughout this maneuver process. Based on the above observations, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

The multi-scale wavelet components provide an enriched diversity of flight patterns. In previous work22, it was established that low- and high-frequency WTCs represent global flight trends and local motion details, respectively. Considering the multi-level wavelet analysis, Fig. 4c, g capture the flight patterns corresponding to low-frequency WTCs. Compared to level-1 and level-2 wavelet components, the level-3 exhibits higher frequency resolution and lower time resolution, showing an overall upward trend in longitude and a downward trend in latitude. However, they fail to capture the fine-grained details, such as the longitude initially decelerated, increasing, and the latitude slightly increasing before decreasing. Figure 4d–f and h-j illustrate high-frequency components in the form of oscillations, with time resolution gradually increasing as the analysis level decreases and manifested by a higher discriminability on the occurrence time of extrema. The multi-scale high-frequency WTCs demonstrate more intricate flight patterns, i.e., their oscillation amplitudes present local maneuverability, with the slope of latitude and longitude in the time domain proportional to the oscillation amplitude in the wavelet domain, for example, as shown between steps 1–4 and steps 6–9 in Fig. 4a, f. On the other hand, the phase changes indicate shifts in local transition direction, for example as observed in steps 12–14 in Fig. 4a, f. From the prediction results of the WTFTP+, the absence of the prior intent information fails to capture the phase changes of high-frequency components near step 13, resulting in a deviation at the end of the predicted trajectory. Nevertheless, the proposed model accurately captures the trend and details in earlier-step horizons, demonstrating expected performance advantages over other selective baseline models.

-

(2)

For the same flight pattern, the orthogonal multi-scale components can provide shared and complementary clues. For instance, the latitude component initially increases and then decreases in steps 1–6 (reach an extremum at step 4). Although the Hi1 and Hi2 components of latitude distribute in orthogonal approximation spaces, Fig. 4i, j both clearly reveal the phase changes in step 1–6 horizons, indicating a shift in the local transition direction within this time window. Figure 4i identifies that the maneuver occurs in around steps 1–6, while Fig. 4j further refines it to steps 4–5, benefiting from higher time resolution. A similar pattern can be observed in the longitude component in steps 12–14, where the transition direction changes. In addition, the comparison between Fig. 4e, f as well as Fig. 4i, j, shows a correspondence for the transition of wavelet-domain oscillation amplitudes, i.e., with the rate of longitude decreasing and the rate of latitude increasing. In fact, even flight trends and motion details with distinct dynamic characteristics also have indicative relationships. The end of the observed trajectory demonstrates a general northeastward flight trend, with Fig. 4c, g showing an increase in longitude and a decrease in latitude from a macro perspective, suggesting that the future trajectory will evolve from northeast to southeast. Meanwhile, Fig. 4i, j reveal a phase change in the latitude within steps 1–6, while Fig. 4e and f show no phase change until step 12. It is indicated that the trajectory trend will shift from northward to southward motion, with the eastward transition trend reflecting a deceleration, further supporting the prediction that the future trajectory will generally evolve from northeast to southeast.

By investigating the flight trends and motion details represented by multi-scale WTC, WTFTP+ achieves higher performance and interpretability for multi-horizon trajectory prediction. In addition, it can be seen that multi-scale WTCs within orthogonal spaces also present certain correlations to provide shared and complementary clues. Actually, this is the key motivation for WTFTP+ to introduce the time-frequency bridging mechanism, which facilitates the interactions of multi-scale flight patterns and further enhances wavelet feature representations. Consequently, the proposed WTFTP+ further strengthens both the prediction performance and the interpretability of time-frequency analysis via the bridging bypass.

Ablation study

In this section, extensive ablation experiments are conducted to evaluate the contribution of the proposed technical improvement of the WTFTP+ framework, focusing on the levels of wavelet analysis and the time-frequency bridging mechanism.

Levels of the wavelet analysis. Based on the 15-step prediction horizon in this work, the maximum decomposition level under the Haar wavelet basis is set to 4. Table 3 presents the prediction performance of WTFTP+ in terms of the levels of wavelet analysis from 1 to 4. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

The prediction performance of WTFTP+ is progressively improved with the increasing of the levels of wavelet analysis. In short-horizon predictions, only marginal performance improvements are obtained from additional wavelet levels. As in the comprehensive MDE metric, by employing two or higher level of the wavelet analysis, both 1- and 3-step horizon prediction errors are approximately 0.12 and 0.23 NM, respectively, which indicates that a single-level wavelet analysis is already able to obtain desired short-horizon prediction performance. In addition, it can be seen that a higher level of wavelet analysis can provide increasing performance improvement for longer prediction horizons. By leveraging time-frequency analysis to capture both global flight trends and local motion details, WTFTP+ effectively learns multi-scale transition patterns in long-range trajectory sequences. Furthermore, by the incorporation of direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm and time-frequency bridging, WTFTP+ has the ability to address the limitations of WTFTP, i.e., the impaired modeling of wavelet component dependencies caused by insufficient time resolution in high-level wavelet analysis. The time-frequency bridging mechanism is able to enhance the multi-scale representations and further build interactions across different wavelet scales. Finally, the proposed model significantly enhances the robustness of multi-scale features, even facing wavelet components with critically low time resolution at certain scales.

-

(2)

As can be seen from the results, the WTFTP+ demonstrates improved prediction accuracy for the latitude-longitude plane with increasing levels of wavelet analysis, the performance and robustness exhibit a gradual decline in the altitude prediction. The results can be attributed that the continuous transition patterns of the latitude-longitude plane inherently incorporates abundant flight trends and motion details, which allows the WTFTP+ to fully leverage the time-frequency analysis capabilities to support the FTP task. However, as in RMSE metrics, the stability of the altitude prediction progressively deteriorates with additional wavelet levels. It can be attributed that during the cruise phases (i.e., dominated flight phase in the operation), the altitude component provides limited motion details to facilitate effective multi-scale feature learning of the proposed WTFTP+. Fortunately, the improvements in terms of the MAE and MAPE metrics are still able to validate the altitude prediction in higher levels of wavelet analysis, demonstrating the fundamental capability of WTFTP+ to capture critical transition patterns in the vertical dimension.

Time-frequency bridging mechanism. Table 4 reports the performance of the WTFTP+ framework with or without the time-frequency bridging mechanism. In addition, the prediction results with different levels of wavelet analysis from 1 to 4 are also reported to investigate the performance improvements by incorporating the time-frequency bridging mechanism. The following conclusions can be observed from the ablation experiments:

-

(1)

In general, the time-frequency bridging bypass can enhance the FTP performance of the WTFTP+. By considering the error distributions across different levels between Tables 3 and 4, it is demonstrated that the proposed time-frequency bridging mechanisms improves the learning capability to capture multi-scale flight patterns. By extracting inherent time-frequency correlations among multi-scale features, the WTFTP+ framework empowered by 4 levels of wavelet analysis reaches the state-of-the-art performance in this dataset, i.e., under 1.1 NM of MDE benchmark at the 15-step horizon prediction. It can also be seen that the proposed framework with time-frequency bridging mechanism also degrades robustness for the 1 level of wavelet analysis in latitude and longitude prediction (as shown in Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore, the prediction performance for the 1-step horizon in Table 4 only show marginal improvements with increasing levels of wavelet analysis, as the same in Table 3. The results indicate that a higher level of wavelet analysis can significantly benefit long-range predictions, while the resulting improvement on short-horizon prediction remains limited, as short-horizon predictions primarily rely on recent correlated trajectory patterns more than multi-scale feature interactions.

-

(2)

The WTFTP+ framework demonstrates robust prediction performance even without the time-frequency bridging bypass. As to the 1-step horizon prediction, the WTFTP+ inherits the superior performance from the WTFTP, thereby validating the effectiveness of time-frequency analysis for the FTP task. Referred to baseline performance in Table 1, the WTFTP+ has higher performance over other baseline models at 1-, 3-, and 9-step horizons even without leveraging the time-frequency bridging enhancement. The results also demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves both higher accuracy in single-step prediction by leveraging time-frequency analysis and competitive multi-horizon performance by the scale-aware decoder with direct multi-horizon prediction paradigm. Correspondingly, the experimental results also validate that the time-frequency bridging mechanism with the addition of bridging bypass obtains expected performance improvements, especially the lower MDE metric in all prediction horizons compared to that of without bridging bypass.

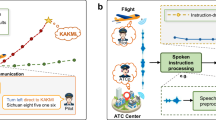

Integrating ATC instruction into WTFTP+ framework

In real-world ATC operation, the ATC instructions issued by ATC controllers are a critical factor influencing flight trajectory evolution. Existing FTP methods with only historical observations typically suffer from a significant performance degradation during instruction-driven maneuvering phases. In our previous work25, a spoken instruction-aware flight trajectory prediction (SIA-FTP) framework was proposed to incorporate textual ATC instructions into the FTP process through a 3-stage progressive multi-modal learning strategy. The results confirmed that integrating spoken instructions is a key factor in ensuring robust prediction performance during instruction-driven phases. In this section, to validate the scalability and generalizability, the SIA-FTP with the proposed WTFTP+ is also performed by replacing the FlightBERT++ backbone to implement a multi-modal FTP model with instruction-aware ability. For the multi-modal fusion process, the instruction embedding is concatenated with the observed trajectory embeddings along the temporal dimension as shown in Fig. 5a, which serves as an informative prior knowledge for the FTP task. In this context, all other experimental configurations are the same with that of in the original SIA-FTP framework25. During the test phase, these models are evaluated on the test set with only instruction-driven maneuvering trajectories.

a The neural architecture of SIA-FTP with WTFTP+ backbone. b The performance comparison of WTFTP+, integrating ATC instruction into WTFTP+, and SIA-FTP. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

The experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 5. Compared to the original WTFTP+ framework, the WTFTP+ model enhanced with ATC instructions demonstrates approximately a 20% improvement in performance at the 9- and 15-step prediction horizons. These results indicate that the WTFTP+ framework exhibits strong generalizability and can serve as a robust foundational model for trajectory prediction, with the flexibility to incorporate additional modalities (such as ATC instructions) to further enhance predictive performance. Compared to the SIA-FTP framework, WTFTP+, integrating ATC instructions, harvests superior performance at short-horizons (step 1-3), which can be attributed that the wavelet-based decomposition enables WTFTP+ to effectively capture fine-grained motion details. Meanwhile, in the longer horizons (step 9-15), the WTFTP+ also achieves comparable performance with the SIA-FTP framework, with only 0.04 NM and 0.14 NM MDE gap, respectively. The performance results from that the relatively small parameter size, i.e., 1.2M in WTFTP+ vs. 44.13M in SIA-FTP, may impact the learning capacity to fully exploit the multi-modal information during the fusion process. The detailed experimental results and more exploration of the integration strategies can be found in Supplementary Information (Section “Integrating ATC instruction into WTFTP+ framework”).

Discussion

In this work, to address the performance gap of the previous WTFTP framework, a WTFTP+ framework is proposed to explore the effectiveness of time-frequency analysis techniques for direct multi-horizon FTP tasks. To this end, a Transformer-style encoder-decoder neural network is designed to generate the multi-scale wavelet components of the future trajectory sequence, which advances the time-frequency analysis ability of the WTFTP framework. To capture the underlying correlations among the multi-scale wavelet components, a time-frequency bridging mechanism is designed to enable bidirectional transformations of multi-scale representations across the wavelet and time domains by improving the Transformer decoder layer. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that the proposed WTFTP+ framework is able to generate accurate predictions over multiple prediction horizons with lower error accumulation. Furthermore, the proposed framework exhibits strong interpretability by visualizing the horizon-plane flight patterns derived from multi-scale wavelet components. Most importantly, the extensibility is also validated through the integration of ATC instructions, confirming its adaptability to more complex, instruction-driven air traffic scenarios. It is believed that the WTFTP+ framework not only provides a time-frequency perspective on multi-horizon FTP modeling but also offers a practical and extensible solution for modern ATC systems.

Although the proposed WTFTP+ framework achieves the expected performance improvements for multi-horizon FTP tasks, its prediction performance on the altitude attribute can be further enhanced compared to selected baselines (as shown in Table 1). As described in Section “Ablation Study”, the transition patterns derived from wavelet components in the altitude attribute differ significantly from those in the longitude and latitude attributes. It can be attributed to the fact that altitude typically exhibits noticeable changes only during climbing or descending maneuvers, whereas longitude and latitude undergo continuously changes throughout flight operations. Consequently, the unified time-frequency modeling across longitude, latitude, and altitude attributes may limit the predictive accuracy of the altitude attribute. In future work, the following potential directions can be further explored to address this limitation:

-

(1)

Designing attribute-independent modeling strategies that decouple vertical dynamics from horizontal motion, thereby capturing the sparse yet abrupt transition patterns of altitude more effectively. Meanwhile, it is essential to design an appropriate interaction mechanism to capture the inherent dependencies between vertical and horizontal dynamics. A channel-attention mechanism may then be employed to capture inter-channel correlations, which alleviates the limitations of unified modeling across attributes with distinct dynamic characteristics while preserving their potential dependencies.

-

(2)

Incorporating multi-modal information such as vertical rate, aircraft performance parameters, and weather conditions (e.g., wind and temperature) to enrich the altitude-related input features. These additional modalities provide complementary cues about vertical dynamics that are not fully captured by position and velocity alone. By integrating such heterogeneous data, the model can achieve a more comprehensive understanding of altitude variations, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy.

Methods

The proposed WTFTP+ framework

In the flight process, the overall motion trends of the aircraft are typically determined by historical transition patterns, flight plans, and real-time ATC instructions. To be specific, for a certain route, the longitude and latitude always evolve along the heading between two consecutive waypoints, indicating that the planned route (in the flight plans) can imply the overall flight trend. At the same time, local variations are introduced by weather conditions, aircraft performance parameters, and pilot-specific operations. In other words, a flight trajectory can be regarded as a combination of global trends and local details. While different flights in similar scenarios may follow similar overall trends, their local motion details often vary significantly, which limits the prediction accuracy of the conventional FTP approaches. Fortunately, the wavelet transform provides an intuitive solution to this challenge by decomposing time series into multi-scale components, thereby decoupling global trends from local details.

Thanks to the effectiveness of the time-frequency analysis, the proposed WTFTP+ framework inherits the core concept of the WTFTP framework, i.e., generating optimal wavelet coefficients to achieve the FTP. Based on the mentioned limitations in WTFTP, the resulting improvements lie in that the WTFTP+ framework directly generates wavelet coefficients of predicted multiple horizons, while WTFTP only performs single-horizon predictions and achieves the multi-horizon prediction in an iterative manner. To this end, an improved Transformer-style encoder-decoder neural architecture is designed to build the FTP model, primarily including four key modules: a trajectory encoder, a wavelet component prompt, a scale-aware wavelet components decoder (SAWCD), and multiple prediction heads. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the overall prediction paradigm is described as follows.

a The complete prediction procedure. The network generates the optimal wavelet coefficients (i.e., \({\{{{{\bf{Q}}}}_{i}\}}_{i\in [0,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) in L levels of wavelet analysis) based on the observations, as the core concept of time-frequency analysis of the WTFTP. b The network consists of four key modules: a trajectory encoder, a wavelet component prompt, a multi-scale-aware wavelet component decoder cascaded by improved Transformer decoder (ITD) layers, and multiple prediction heads for generating \({\{{{{\bf{Q}}}}_{i}\}}_{i\in [0,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\). c The trajectory encoder projects observed trajectory sequence into abstract embeddings, and wavelet component prompt yields initial wavelet embeddings composed of low-frequency embedding derived from tail of observed trajectory and learnable high-frequency embeddings.

Let \({{{\bf{P}}}}_{N-M:N-1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{6\times M}\) be a trajectory sequence observed over the last M timestamps. The trajectory encoder is designed to project the trajectory sequence into high-dimensional trajectory embeddings \({{\bf{TE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times M}\):

where d represents the dimension of trajectory embeddings.

The objective of the SAWCD is to generate multi-scale wavelet components that imply the time-frequency features of predicted horizons. Specifically, the initial wavelet embedding (IWE) is firstly constructed by wavelet component prompt to serve as the input to the SAWCD, including initial low-frequency embedding (IL) and initial high-frequency embedding (IH). Since tail vector of trajectory (defined in this study as the trajectory attributes at the last historical time step minus that at the previous time step) is approximately aligned with the trajectory transition trend, it is utilized to construct the prompt of the low-frequency flight pattern, i.e., IL. Considering that it is hard to infer the local motions of predicted horizons from the past horizons, a couple of learnable parameters are trained from historical data to represent high-frequency wavelet embeddings, i.e., IH.

As shown in Fig. 6b, the IWE and TE are fed to the SAWCD to obtain optimal wavelet components (OWC), in which the CDA is introduced to fuse historical temporal features into multi-scale flight patterns, and time-frequency bridging mechanism is designed to promote inter-scale inherent correlating. It can be described as follows:

The SAWCD is implemented by two parallel branches.

-

Main branch: follows a Transformer-style architecture, where cross-domain interactions are performed under the assumption that time-domain trajectories lie in the approximate space at a certain scale and multi-scale features are distributed within its subspaces.

-

Bypass branch: serves as a time-frequency bridging bypass: wavelet-domain features are first transformed into the time domain via the W2T block, then a self-attention mechanism is designed to capture intrinsic relationships within the time-domain sequences and build the correlations among multi-scale features. The processed features are transformed back into wavelet components through the T2W block to support subsequent time-frequency interactions.

In this work, the dual-branch of the SAWCD focuses on effectively capturing flight transition patterns from both the time and wavelet domains while preserving the orthogonality of wavelet components to facilitate accurate trajectory prediction.

To obtain the multi-horizon trajectory, a set of prediction heads are designed to project the corresponding scale of time-frequency representations into wavelet components. During the prediction procedure, a differential prediction strategy is utilized to avoid unnecessary prediction of the direct-current component, and the inverse discrete wavelet transformation of OWC is applied to obtain the differential sequence of predicted horizons. Finally, an inversely difference operation is employed to obtain trajectory attributes of the next K horizons. The prediction process can be described as:

where IDWT(⋅) is the inverse discrete wavelet transform operation, and IDIFF(⋅) represents the inversely difference operation.

Note that the goal of the WTFTP+ framework is to predict the wavelet coefficients of the future trajectory sequence by considering the time-frequency features of the observations. During the training process, the mean squared error (MSE) loss is used to quantify the difference between the predicted and actual wavelet coefficients, thereby driving the optimization of the neural network parameters. The implementation details of each module are described in the following sections.

Trajectory encoder

The trajectory encoder is constructed by trajectory point embedding block and Transformer encoder blocks, which aims to extract the spatial-temporal dependencies of the observations. Specifically, to better learn the latent features from the observations, it is essential to map the trajectory points to high-dimensional embedding space to extract discriminative spatial features. Similar to the WTFTP framework, a simple yet effective trajectory point embedding block is employed to project the trajectory point into embedding space, which can be described as:

where \({{{\bf{P}}}}_{N-M:N-1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times M}\) is the observed trajectory sequence, and \({{\bf{I}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{M\times D}\) represents its attribute embeddings. \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times (D//2)}\) and \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{(D//2)\times D}\) are learnable transformation matrices. \({{{\bf{b}}}}_{i1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{D//2}\) and \({{{\bf{b}}}}_{i2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{D}\) are bias vectors. σ(⋅) represents the ReLU activation function. M is the number of observed trajectory points, and D is the feature space dimension. // denotes the floor division operator.

The WTFTP+ framework employs the Transformer encoder33 to extract the temporal dependencies among observed trajectory points. Since the self-attention mechanism is permutation-invariant, a positional encoding (PE) strategy is designed to establish the relative positional relationships of trajectory sequence. Therefore, the observed trajectory embeddings TE can be obtained as follows:

where TransformerEncoder(⋅) is multi-layer Transformer encoder. PE(⋅) applies sine and cosine functions to generate positional embeddings with dimension of D and add them into I.

Scale-aware wavelet component decoder

The SAWCD is stacked by several ITD layers, which incorporates time-frequency analysis capabilities by the proposed CDA and time-frequency bridging mechanism. Specifically, the initial wavelet embedding IWE is constructed to serve as the input of the SAWCD, which is further sequentially fed to the ITD layers into generate multi-scale wavelet component representations. As shown in Fig. 6b, the core architecture of the ITD layer follows the standard Transformer decoder layer with the following improvements:

-

The scale-aware mechanism is incorporated into the self-attention and feed-forward network to preserve the orthogonality of inter-scale features, allowing the model to learn single-scale flight transition pattern during the training procedure.

-

Since the multi-scale features are distributed in mutually orthogonal subspaces of the observed trajectory approximation space, the CDA is designed to incorporate embeddings of the observed trajectory sequence into the multi-scale features.

-

Most importantly, a time-frequency bridging mechanism is proposed to extract inherent time-frequency correlations among multi-scale features while maintaining their orthogonality, which serves as the bridging bypass in the decoder.

Initial wavelet embedding

The initial wavelet embedding consists of two stacked parts: the initial low-frequency (IL) embeddings and the initial high-frequency (IH) embeddings. These embeddings are arranged in a descending order of time resolution, and the embeddings of the same resolution are sequentially grouped as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. In general, low-frequency wavelet components represent the global trend of the trajectory sequence, while the high-frequency wavelet components imply the local motion details. In this work, the attribute difference between the last historical step and its previous step is defined as the prompt for future flight trend, which is transformed into a high-dimensional vector and replicated to generate the \({{\bf{IL}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{L}\times D}\), as shown below:

where \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{d1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times D//2}\) and \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{d2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{D//2\times D}\) are learnable weight matrices. \({{{\bf{b}}}}_{d1}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{D//2}\) and \({{{\bf{b}}}}_{d2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{D}\) are learnable bias vectors. tL is the sequence length of low-frequency wavelet component in level-L wavelet analysis. The operation REP(a, b) replicates the vector a along the column dimension for b times.

For initial high-frequency components, considering the complicated predictability of future local motions under incomplete maneuvering intentions, a couple of learnable parameters are employed to model the distribution of fast dynamics from historical data. In addition, considering the orthogonality of inter-scale wavelet components, a learnable scale encoding (SE) strategy is proposed to enhance the scale discriminability of the initial embeddings. The PE strategy is also applied to enhance sequential discriminability along the temporal dimension. Mathematically, the initial wavelet embedding can be obtained by:

where \({{\bf{IWE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times D}\) serves as the input of the SAWCD, which corresponds to the wavelet components of the future flight trajectory. \({{\bf{IH}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{({t}_{A}-{t}_{L})\times D}\) is the learnable IH embedding. \({{\bf{SE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{(L+1)\times D}\) is the learnable scale embedding. L is the level of wavelet analysis. \({\{{t}_{i}\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) stands for the sequence length of level-i wavelet component, while \({t}_{A}={t}_{L}+{\sum }_{i=1}{L}{t}_{i}\) stands for that of stacked wavelet components in L levels of wavelet analysis. The \({\{{t}_{i}\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) can be calculated below:

where H is the predicted steps.

Scale-aware self-attention

To investigate sequential dependency of intra-scale flight patterns, in each ITD layer, the self-attention mechanism is applied to obtain enhanced wavelet embedding (EWE) derived from IWE. Therefore, a scale-aware self-attention (SA2) mechanism is designed to preserve temporal causality and prevent inter-scale feature leakage by employing a well-crafted mask matrix. The residual connection, followed by layer normalization (LN), is utilized to retain the learned semantics during the information propagation process. The inference process can be described as follows:

where \({{\bf{EWE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times D}\) is the enhanced wavelet embeddings. The attention weight \({{\bf{W}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times {t}_{A}}\) is calculated by:

where \({{{\bf{Q}}}}_{I},{{{\bf{K}}}}_{I}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times (D/m)}\) are the query and key features of IWE. m is the number of heads. \({{{\bf{Mask}}}}_{sa2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times {t}_{A}}\) is the mask matrix.

Cross-domain attention

To learn the underlying flight transition patterns of the observation sequence, a CDA mechanism is utilized to incorporate the prior transition patterns from observed trajectory representation into enhanced wavelet embeddings. Since multi-scale features are generally distributed in the subspace of the time-domain approximation space, the CDA is expected to perform feature interaction between the trajectory encoder and the SAWCD, which learn wavelet-domain flight pattern from observed trajectory. Specifically, attention weights are obtained using: EWE serves as the queries, and the observed trajectory representation TE serves as both keys and values, as shown below:

where \({{\bf{FWE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times D}\) is the output, i.e., fused wavelet embedding. Similarly, the residual connection, followed by LN, is utilized to retain semantics during the information propagation process.

Time-frequency bridging

Although the CDA effectively extracts informative flight transition patterns from the observed trajectory, due to the orthogonality of these wavelet components, it is still hard to capture inherent dependency between global trend and local motion patterns. In this work, a time-frequency bridging mechanism is proposed to extract the intrinsic correlations across multi-scale wavelet components to preserve the wavelet orthogonality, which is expected to fully leverage the time-frequency analysis capability of wavelet transform in the FTP task. Note that time-frequency bridging mechanism is performed in parallel with the CDA procedure as a bypass operation on EWE, which achieves an effective and efficient feature learning. Specifically, the bridging bypass first transforms multi-scale components of enhanced wavelet embeddings into a unified time domain by a trainable W2T block. Then time-domain self-attention is designed to establish the interaction bridge for inter-scale features and capture significant dependency among multi-scale flight patterns. To facilitate subsequent procedure, a trainable T2W block is proposed to regain time-frequency representations to support the whole time-frequency analysis for the FTP task.

Let low- and high-frequency features in wavelet analysis at the i-th level be \({{{\bf{Lo}}}}_{i},{{{\bf{Hi}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{i}\times D}\), respectively. Taking L = 3 levels of wavelet analysis as an example, the time-frequency bridging process is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 5 by cascading W2T block, time-domain self-attention, and T2W block. The W2T procedure can be described as follows:

where \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i}^{lw2t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2{t}_{i}\times {t}_{i-1}}\) is learnable inverse wavelet transform matrix at the i-th level of the W2T procedure, and \({{{\bf{b}}}}_{i}^{lw2t}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{i-1}}\) serves as learnable bias. ALT(Loi, Hii) alternate the rows of Loi and Hii along the time dimension. Notably, the learnable inverse wavelet transform matrix consists of: i) a sparse matrix constructed from wavelet filter parameters (as described in Supplementary Information, Section “The wavelet-to-time domain procedure”), and ii) learnable parameters to pad the sparse elements in i). Thus, the W2T procedure is able to achieve the inverse wavelet transform-like operations, in which the design of the learnable parameters facilitates adaptive adjustment of the bridging bypass and promotes the interaction of inter-scale features.

Through iterative process of Eq. (18), low- and high-frequency features at the same level are jointly reconstructed into the lower-frequency. As the level i decreases in the W2T procedure, the time resolution of Loi goes higher, which are ultimately transformed into Lo0 in time domain. Then, the self-attention mechanism is employed to perform feature interactions by extracting inherent correlations within Lo0, as shown below:

where \({\hat{{{\bf{Lo}}}}}_{0}\) represents the output time-domain features. TSA(⋅) represents time-domain self-attention. In addition, the residual connection followed by LN is utilized to retain semantics during information propagation.

As an inverse operation, the T2W procedure aims to regain time-frequency representations to facilitate subsequent inference, which in practice transforms \({\hat{{{\bf{Lo}}}}}_{0}\) into multi-scale wavelet features, as shown below:

where \({\hat{{{\bf{Lo}}}}}_{i},{\hat{{{\bf{Hi}}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{i}\times D}\) represent low- and high-frequency features in T2W procedure at the i-th level. \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i}^{lt2wl},{{{\bf{W}}}}_{i}^{lt2wh}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{i-1}\times {t}_{i}}\) are learnable low- and high-frequency wavelet transform matrix at the i-th level of the T2W procedure. \({{{\bf{b}}}}_{i}^{lt2wl},{{{\bf{b}}}}_{i}^{lt2wh}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{i}}\) serve as learnable low- and high-frequency bias vectors. The learnable low- and high-frequency wavelet transform matrices are constructed in the similar way with the learnable inverse wavelet transform matrices (as described in Supplementary Information, Section “The time-to-wavelet domain procedure”), and also consist of two parts, the wavelet filter parameters and the learnable parameters. After the time-frequency bridging, \({\hat{{{\bf{Lo}}}}}_{L}\) serves as the low-frequency component, while \({\{{\hat{{{\bf{Hi}}}}}_{i}\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) serve as the multi-scale high-frequency components. Finally, the bridged wavelet embeddings \({{\bf{BWE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times D}\) is obtained by concatenating the \({\hat{{{\bf{Lo}}}}}_{L}\) and \({\{{\hat{{{\bf{Hi}}}}}_{i}\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\). The T2W procedure is the inverse process of the W2T procedure. As the level i increases, the time-domain feature \({\hat{{{\bf{Lo}}}}}_{0}\) is decomposed back into wavelet domain with frequency resolution gradually going higher.

Scale-aware feed-forward network

In each ITD layer, the FWE and BWE are aggregated and further extracted in the scale-aware feed-forward networks (SAFFNs) by a shared architectures with unique parameters, preserving the orthogonality of inter-scale features and yielding complete wavelet embeddings \({{\bf{CWE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times D}\). The SAFFN can be expressed as:

where \({{\bf{MWE}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{A}\times D}\) is the sum of FWE and BWE. \({\hat{{{\bf{Q}}}}}_{0}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{L}\times D}\) is the low-frequency components of the CWE, while \({\{{\hat{{{\bf{Q}}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{t}_{L-i+1}\times D}\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) are the multi-scale high-frequency components. \({\{{{{\bf{SAFFN}}}}_{i}(\cdot )\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) represents the scale-aware feedforward network for Hii, while SAFFN0(⋅) for LoL. Similarly, the residual connection followed by LN is also utilized to retain semantics during information propagation.

Prediction and post-processing

Due to the multi-scale and orthogonality properties of wavelet components, multiple prediction heads are required to map complete wavelet embeddings of the last ITD layer to obtain wavelet components of certain predicted horizons. Each prediction head is implemented by multi-layer perceptrons (MLP) (i.e., two linear layers with an ReLU activation function). The prediction process can be described as follows:

where \({\{{{{\rm{PredictionHead}}}}_{i}(\cdot )\}}_{i\in [1,L]\cap {\mathbb{Z}}}\) represents the i-th prediction head for generating Qi, i.e., the desired WTCi according to definition of wavelet component in our previous work22.

Subsequently, to achieve the FTP task with trajectory attributes of predicted horizons, the IDWT operation is applied to transform predicted wavelet components back to the time domain, further reconstructing the predicted future trajectory sequence, as in our previous work22. Mathematically, the prediction for the j-th attribute \({\hat{{{\bf{P}}}}}_{N:N+H-1}^{{\prime} }[j-1,:]\) is shown as:

where \({{\rm{TRIM}}}(\cdot )\) is applied to crop out the redundant segments at the end of the trajectory sequence due to the signal extension, i.e., the first H elements along the time dimension retained. IDIFF(⋅) represents the inverse difference operation to avoid unnecessary prediction for the direct-current component.

Loss function

To facilitate the learning of multi-scale flight patterns, the MSE loss function performed on wavelet components is proposed to update the learnable parameters of the WTFTP+ framework, following the similar strategy to the WTFTP framework. Furthermore, an L2 regularization penalty is applied to optimize the learnable parameters within the W2T and T2W transform matrices. This regularization constrains the deviation from the standard wavelet filters, thereby preserving the effectiveness of the time-frequency bridging process. The loss function is formulated as follows:

where \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{w2t},{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{t2w}\) are one part of the loss function and the L2 regularization for the W2T and T2W transform matrices, respectively. epoch and total_epoch are the current and total epochs during the training procedure, whereby a proper ratio allows the learnable parameters to have a broader optimization exploration space in the early stages of training, while gradually converging toward the wavelet filter as training progresses. The details of \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{w2t},{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{t2w}\) are described as follows:

where β is the weight for both of the L2 regularizations. L is the level of wavelet analysis. lde is the number of decoder layers. \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i,j}^{lw2t},{{{\bf{b}}}}_{i,j}^{lw2t}\) are the W2T transform matrix and bias vector at the j-th level of wavelet analysis in the i-th layer of the ITD. \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i,j}^{lt2wl},{{{\bf{b}}}}_{i,j}^{lt2wl}\) are the T2W transform matrix and bias vector at the j-th level of wavelet analysis in the i-th layer of the ITD for the low-frequency, while \({{{\bf{W}}}}_{i,j}^{lt2wh},{{{\bf{b}}}}_{i,j}^{lt2wh}\) for the high-frequency. ∥⋅∥2 is the Euclidean norm. Since the spectral norm is difficult to calculate for transform matrices in time-frequency bridging, the Frobenius norm, ∥⋅∥F, is utilized to optimize the upper bound of the spectral norm.

The MSE loss of the wavelet component, i.e., \({\sum }_{k=0}^{L}{{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{wavelet}^{k}\), is calculated by:

where hL−k is the length of WTCk22, satisfying hL−k = tL−k+1 except hL = tL. d = 6 is the number of trajectory attributes. \({\hat{c}}_{i,j}^{k}\) is the value of the i-th predicted wavelet coefficient in the j-th attribute of WTCk after applying the DWT operation to the future trajectory differential sequence, while \({c}_{i,j}^{k}\) is the ground truth.

Data availability

We are not authorized to publicly release the whole dataset used during the current study concerning safety-critical issues. Nonetheless, the processed example samples are provided at https://zenodo.org/records/17624336 (ref. 34). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code is publicly available at https://zenodo.org/records/17624336 (ref. 34).

References

Han, Y., Wang, M. & Leclercq, L. Leveraging reinforcement learning for dynamic traffic control: a survey and challenges for field implementation. Commun. Transp. Res. 3, 100104 (2023).