Abstract

The leukodystrophy Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is caused by myelin protein proteolipid protein gene (PLP1) mutations. PMD is characterized by oligodendrocyte death and CNS hypomyelination; thus, increasing oligodendrocyte survival and enhancing myelination could provide therapeutic benefit. Here, we use the PMD mouse model Jimpy to determine the impact of the integrated stress response (ISR) on the oligodendrocyte response to mutant PLP expression. Male Jimpy animals in which the ISR-triggering eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 2α kinase, protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), is inactivated have an extended lifespan that correlates with increased oligodendrocyte survival and enhanced CNS myelination. Inactivation of downstream components of the ISR pathway, in contrast, does not rescue oligodendrocytes or myelin. Phosphorylated eIF2α inhibits the exchange factor eIF2B, resulting in diminished protein synthesis. Treatment with small molecule eIF2B activators 2BAct and ISRIB increases oligodendrocyte survival, CNS myelination, and doubled the Jimpy lifespan. These results suggest that ISR modulation could provide therapeutic benefit to PMD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leukodystrophies represent a class of genetic disorders that result in abnormal central nervous system (CNS) myelin, which is produced by oligodendrocytes1. Leukodystrophies are relatively rare, approximately one in 7500 births, but many lead to severe clinical symptoms resulting in childhood mortality2. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease (PMD) is a hypomyelinating X-linked leukodystrophy caused by mutations in the proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1) gene encoding the highly expressed CNS protein, proteolipid protein (PLP), which is exclusively expressed by myelinating cells3. Oligodendrocyte apoptosis is thought to be the primary cause of myelin abnormalities in PMD patients. Although stem cell approaches designed to replace mutant oligodendrocytes have shown promise4,5, and antisense oligonucleotides against the PLP1 transcript dramatically increase the lifespan of PMD mouse models6, there are currently no approved therapies for PMD7.

The severity of PMD varies based on the type of mutation8. Most PMD cases are caused by duplications of the entire PLP1 gene locus, resulting in increased PLP expression9. Loss-of-function PLP1 alleles result in relatively mild clinical symptoms, whereas missense and frameshift mutations lead to severe developmental abnormalities and early lethality10. PLP1 point mutations that result in non-conservative amino acid substitutions lead to more severe clinical outcomes than conservative substitutions10. PLP is a highly conserved integral membrane protein that passes the lipid bilayer multiple times11. A subset of the more severe PLP1 mutations has been shown to disrupt PLP transport through the secretory pathway, resulting in accumulation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This cytotoxic buildup gradually kills oligodendrocytes, ultimately causing axonal swelling and neurodegeneration12. PLP accumulation in the ER activates the unfolded protein response (UPR) arm of the integrated stress response (ISR)13. The ISR is a protective response to various cellular stresses that activates one of four eIF2α kinases, including the PKR-like ER kinase (PERK)14. Phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α results in the attenuation of protein synthesis and cellular protection15. The PERK pathway is rapidly activated by ER stress in an effort to restore protein homeostasis in the secretory pathway. In addition to the PERK pathway, ER stress also activates the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) arms of the UPR to ameliorate proteotoxicity by enhancing the transcription of chaperone genes and degradation of misfolded or aggregated polypeptides16. Ultimately, if the cellular stress cannot be resolved, a maladaptive response is activated that results in the apoptotic elimination of the stressed cells17.

A number of animal models with Plp1 mutations have proven useful in the study of PMD disease pathogenesis18. These include the shaking pup canine model, the myelin-deficient rat model, as well as a number of mouse models of varying severity19. The Jimpy mouse model is the result of a 74 base pair deletion in the Plp1 gene that causes a frameshift in the open reading frame, which changes the carboxy terminus11,20. Although the Plp1 mutation of Jimpy mice is not an authentic mutation of a human disease allele, these mice recapitulate the cellular, molecular and neurologic features seen in severe “connatal” forms of human PMD21. Jimpy mice, which exhibit tremors and seizures, and die at about postnatal day 21, have dramatically reduced numbers of oligodendrocytes and lack CNS myelin22,23. The PERK arm of the UPR/ISR has been shown to be activated in Jimpy oligodendrocytes24.

Previously, we have shown that oligodendrocytes in the presence of an inflammatory environment, in vitro and in vivo, also activate the PERK arm of the UPR/ISR25,26. In this protective state, a subset of mRNA transcripts that encode cytoprotective proteins is preferentially translated. Our studies and those of others have demonstrated that an enhanced or prolonged stress response, using either genetic or pharmacologic approaches, provides increased protection to oligodendrocytes in the presence of inflammation27,28,29. Here, we examined whether manipulating the ISR results in an altered oligodendroglial response to mutant PLP expression in Jimpy mice. We found that inhibition of the ISR in Jimpy oligodendrocytes, either genetically or pharmacologically, increased oligodendrocyte survival, enhanced CNS myelination, and prolonged lifespan.

Results

Perk inactivation increases Jimpy oligodendrocyte survival, CNS myelination, and lifespan

PERK is one of four stress-sensing kinases that trigger the UPR arm of the ISR by phosphorylating eIF2α30. To determine the potential role that this pathway plays in modulating the response of oligodendrocytes against the ER stress caused by the Jimpy Plp1 mutation, we crossed Jimpy mice, which normally die at around postnatal day 21 (PND 21) with Perk heterozygous mice. Jimpy males that were heterozygous for the Perk null allele (Jimpy; Perk+/−) displayed a significantly longer lifespan than Jimpy males on a WT background (Fig. 1a, b). Homozygous Perk null mice die shortly after birth31; so to further examine the role of the PERK pathway in oligodendrocytes in response to chronic ER stress, we crossed female mice that carry the Jimpy mutation with mice that contain a conditional (floxed) Perk allele32. These mice were crossed to Olig2-Cre mice, which express Cre throughout the oligodendrocyte lineage33. Previously, we have shown that PERK is dispensable for normal oligodendrocyte development and CNS myelination34,35. The Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre animals lived ~2 weeks longer than the Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice (Fig. 1a, b), suggesting that PERK activity is detrimental to Jimpy mice. Despite their prolonged lifespan, the Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre animals displayed similar tremor and seizure symptoms as Jimpy control animals.

a Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing the overall survival of Jimpy mice (n = 20), Jimpy;Perk+/− mice (n = 22), Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice (n = 31), Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice (n = 32). ****p < 0.0001 indicating statistically significant change between Jimpy mice and Jimpy;Perk+/− mice as well as between Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice using Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. b Average survival days of four mouse lines. p = 0.0029 (Jimpy vs Jimpy;Perk+/−), p < 0.0001(Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). c Representative images of ASPA and MBP staining of corpus callosum from WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2 mice at PND 19. d Quantification of the number of ASPA+ oligodendrocytes in corpus callosum (n = 3 mice/group). p < 0.0001 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl, WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre), p = 0.0353 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). e Representative images of Caspase 3 (casp3) and Olig2 staining of corpus callosum from WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2 mice at PND 19. Arrows point to Casp3+/Olig2+ apoptotic cells. f Quantification of the number of Casp3+Olig2+ oligodendrocytes in corpus callosum (n = 5 WT mice, n = 3 Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice, n = 4 Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice). p = 0.0033 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p = 0.0181 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). Values are mean ± SEM. ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Groups (b, d, f) were compared using one-way ANOVA with Turkey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further assess the impact of Perk inactivation on Jimpy oligodendrocytes, we examined these mice histologically at PND 19, which is close to the end of the expected lifespan of Jimpy controls. Antibodies against aspartoacylase (ASPA, mature oligodendrocytes)36, breast carcinoma-amplified sequence 1 (BCAS1, differentiating oligodendrocytes)37, and Olig2 (oligodendrocyte lineage cells)38 were used to characterize the oligodendrocyte lineage in the Jimpy mice. Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice had a significant lower density of ASPA immunoreactive (+) mature oligodendrocytes in the corpus callosum compared to wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 1c, d). However, the oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutant Jimpy animals (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre) had a substantially higher density of ASPA+ oligodendrocytes than control Jimpy mice (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl). A similar change was found in newly differentiating oligodendrocytes (BCAS1+Olig2+) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b), whereas the total number of Olig2+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells remained unchanged between Jimpy control and Perk mutant Jimpy animals (Supplementary Fig. 1a, c). Notably, the number of apoptotic oligodendrocyte lineage cells labeled by caspase 3 (Casp3+Olig2+) was significantly reduced in Perk mutant Jimpy mice (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre) (Fig. 1e, f). Together, these data provide further support that PERK deletion in oligodendroglia partially ameliorates the loss of mature and newly differentiating Jimpy oligodendrocytes.

Jimpy mutant mice display severe CNS hypomyelination39, which is reflected by minimal myelin basic protein (MBP) immunoreactivity in the corpus callosum of control Jimpy mice (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl) (Fig. 1c). In contrast, oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutant Jimpy animals (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre) exhibited higher MBP immunoreactivity, suggestive of increased myelination (Fig. 1c). Consistent with this possibility, at the electron microscopic (EM) level, myelin was absent in the Jimpy mice on a Perkfl/fl background. In contrast, myelinated sheaths were observed in Jimpy mice lacking Perk (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre), though reaching only ~10% of the axons myelinated in WT mice (3 × 105/mm2) (Fig. 2a, b). Consistently, a large number of degenerating axons labeled by the DegenoTag antibody40, which specifically recognizes a neoepitope in the neurofilament light chain that becomes exposed during axonal degeneration39 and demyelination41, were present in the brains of Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice, while a significant reduction in Degenotag+ axons was observed in Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre animals (Fig. 2c, d). Moreover, Western blots revealed that a significant increase in myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and MBP in the oligodendrocyte-specific Perk KO Jimpy animals compared to control Jimpy mice (Fig. 2e–g). Similarly, real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) studies showed a comparable partial rescue of Mbp and Mag mRNA levels when Perk is deleted on the Jimpy background (Fig. 2h). Together, these data indicate that inhibition of the PERK pathway overcomes some of the detrimental effects of mutant PLP expression in Jimpy mice, allowing partial CNS myelination.

a Representative EM images of axons in corpus callosum from WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice at PND 19. b Quantification of the number of myelinated axons in corpus callosum (n = 3 mice/group). p < 0.0001 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl, WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre), p = 0.0204 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). c Representative DegenoTag staining of corpus callosum from WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice at PND 19. d Quantification of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DegenoTag marked degenerated axons in corpus callosum (n = 4 WT mice, n = 3 Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice, n = 3 Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice). p = 0.0013 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p = 0.0213 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). e Representative immunoblot analysis for MAG and MBP in the brains from WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice at PND 19. f, g Quantitative densitometric analysis for MAG and MBP relative to b-actin (n = 4 mice/group). p < 0.0001 (MAG/actin: WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl, WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre), p = 0.001 (MBP/actin: WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p = 0.001(MBP/actin: WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre), p = 0.008 (MBP/actin: Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). h Relative mRNA levels of Mbp and Mag from brain tissues of WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice at PND 19 (n = 4 mice/group). p = 0.0003 (Mbp: WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p = 0.0489 (Mbp: Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre), p = 0.0168 (Mag: WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p < 0.0001 (Mag: Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). Values are mean ± SEM. ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Groups in b and d were compared using one-way ANOVA with Turkey post hoc test. Groups in h was compared using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Groups in f and g were compared using two-tailed unpaired Welch’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Perk inactivation increases Jimpy OPC proliferation and reduces astrogliosis

Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) are distributed throughout the CNS in a uniform, tiled manner where they account for ~5% of all cells42. OPCs represent the only mitotic stage in the oligodendrocyte lineage and have the capacity to replenish lost oligodendrocytes while maintaining OPC numbers42,43. To determine whether the increased survival of oligodendrocytes in Jimpy mice with a diminished ISR response affects the OPC population, we quantified OPC density in the corpus callosum of Jimpy oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutants (Fig. 3), through immunostaining with anti-platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα). There was no significant difference in OPC density between the groups at PND 19 (Fig. 3a, b). OPCs exhibit homeostasis and proliferate to maintain a constant density when their numbers are reduced. To determine if the inability to form oligodendrocytes in Jimpy mice leads to persistent recruitment of OPCs and enhanced homeostatic proliferation, we assessed OPC proliferation using immunostaining against Ki67. The density of proliferating OPCs (PDGFRα+ Ki67+ cells) in the Jimpy samples (24/mm2) was about 69% lower than WT controls (77/mm2) (Fig. 3a, c). This reduction was partially rescued in the oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutant Jimpy animals, with the density of the double positive cells increasing to 51/mm2, reaching 67% of the mitotic OPCs (PDGFRα+ Ki67+) observed in WT animals. When normalized to the total number of PDGFRα+ OPCs, the percentage of proliferating OPCs was not significantly different from controls, indicating that OPCs in Jimpy oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutants remain highly mitotically active (Fig. 3d). On the WT background, the oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutation (Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre) does not change the populations of OPCs (Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting its effects are specific to the context of PLP deficiency. These results suggest that the rate of OPC proliferation (and homeostatic replacement) is reduced in Jimpy mice and that this change is partially rescued when Perk is deleted.

a Representative images of PDGFRα and Ki67 staining of corpus callosum from WT mice, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice at PND 19. Arrow heads point to the examples of PDGFRα+ Ki67+ cells. b Quantification of the number of PDGFRα+ OPCs in corpus callosum. c Quantification of the number of PDGFRα+ki67+ proliferating OPCs in corpus callosum. p = 0.0001 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p = 0.0271 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre), p = 0.0238 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). d Quantification of the percentage of PDGFRα+ki67+ cells in total PDGFRα+ OPCs in corpus callosum. p = 0.0003 (WT vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl), p = 0.0005 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). Groups in b, c and d (n = 5 WT mice, n = 4 Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice, n = 3 Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice). Values are mean ± SEM. ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Turkey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CNS hypomyelination in PMD is often accompanied with neuroinflammation, which has been suggested to play a detrimental role in disease progression44. Enhanced microglial activation (IBA1+) and astrogliosis (GFAP+) were observed in control Jimpy mice (Supplementary Fig. 3). Similar numbers of hypertrophic microglia were observed in the Jimpy mice with the Perk mutation (Supplementary Fig. 3a, c); however, the number of GFAP+ astrocytes was significantly reduced in Jimpy mice lacking Perk in oligodendrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 3b, d). Together, these results suggest that Perk deletion in oligodendroglia correlates with enhanced OPC differentiation in Jimpy mice and reduced astrocytic reactivity, thereby partially alleviating the neuroinflammatory pathology.

Downstream ISR inactivation fails to correct Jimpy oligodendrocyte deficits

GADD34 and CHOP are downstream ISR target genes, and RT-qPCR analysis revealed a significant upregulation of Gadd34 and Chop expression in the CNS of Jimpy mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a). GADD34 is the regulated co-factor of the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) that dephosphorylates p-eIF2α to return stressed cells to proteostasis45, and its increased expression upon stress contributes to the termination of the ISR. Previously, we have shown that oligodendrocytes from Gadd34 mutant mice, which display a prolonged ISR response, are more resistant to the presence of IFN-γ in vitro and in vivo46. We also have found that Gadd34 mutant mice display an ameliorated experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) disease course that correlates with reduced oligodendrocyte death27. To determine if a prolonged ISR response impacts the viability of Jimpy oligodendrocytes, we crossed the Jimpy mutation onto a homozygous mutant Gadd34 background (Gadd34ΔC/ΔC). The lifespan of Jimpy;Gadd34 mutants (Jimpy; Gadd34ΔC/ΔC) was indistinguishable from that of Jimpy;Gadd heterozygous (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c). There was also no difference in the density of CC1+ oligodendrocytes at PND19 in Jimpy mice with the Gadd34 mutation (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e), in contrast to the observed protection of oligodendrocytes upon prolongation of the ISR in inflammation-mediated demyelination models27,46.

CHOP is a transcription factor that is activated in response to ER stress and other stressors that induce the ISR. CHOP has been shown to contribute to apoptosis that occurs in response to prolonged, unmitigated ER stress47. To examine the impact of CHOP in Jimpy oligodendrocytes, we crossed the Jimpy mutation onto a homozygous Chop null background48. The overall lifespan of the Jimpy mutants was slightly increased by the Chop mutation (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Although consistent, the average survival increased by less than 2 days in Jimpy; Chop−/− mutants (22.4 days) over that of Jimpy;Chop heterozygous (20.7 days) (Supplementary Fig. 4c). However, there was no increase in the density of oligodendrocytes in Jimpy mice when CHOP was deleted (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e).

Pharmacological ISR attenuation increases Jimpy myelination and lifespan

Phosphorylated eIF2α, which occurs as a result of PERK activation, interacts with and inhibits the guanine exchange factor eIF2B, resulting in diminished protein synthesis, and increased expression of the transcription factor ATF4 and its target genes49. Small molecule activators of eIF2B (such as ISRIB and 2BAct) have the ability to rescue protein synthesis and attenuate the ISR by allosterically antagonizing phosphorylated eIF2α, thus desensitizing cells from stress50,51. We next evaluated whether pharmacological ISR attenuation with 2BAct impacts the lifespan of Jimpy mutant mice and viability of Jimpy oligodendrocytes. Jimpy female carrier mice were mated with WT males and fed chow containing 100 μg/mg of 2BAct, which has been shown to rescue eIF2B activity, attenuating the ISR52,53. Following birth, the dams and pups were continuously maintained on the 2BAct diet. Jimpy males on the control diet displayed the tremoring phenotype typical of the mutant animals and lived an average of 18.1 days. In contrast, Jimpy mice on the 2BAct diet, while still presenting tremor, survived approximately twice as long as Jimpy mice on the control diet (Fig. 4a, b). This increased survival was associated with an increased number of ASPA+ oligodendrocytes in the white matter area of corpus callosum, cerebellum and brainstem of Jimpy+2BAct mice at PND 19 (Fig. 4c, e, and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, e, f). Consistently, myelinated axons were absent from these regions in Jimpy mice, but detectable in Jimpy mice on the 2BAct diet (Fig. 4d, f, and Supplementary Fig. 5c, d, g, h). Furthermore, myelin protein gene expression was significantly increased at both PND14 and PND19 in the Jimpy mice treated with 2BAct (Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast to the Jimpy; Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre mice, no differences in the density of PDGFRα+ or NG2+ OPCs, nor OPC proliferation, as determined by Ki67 staining and EdU incorporation, were observed in the 2BAct-treated Jimpy animals at PND 19 (Fig. 5).

a Kaplan–Meier survival curve showing the overall survival of Jimpy mice with control diet (n = 17) and 2BAct diet (n = 13). ****p < 0.0001 indicating statistically significant change between two groups, using Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. b Average survival days of two treatment groups. ****p < 0.0001. c Representative images of ASPA staining of corpus callosum from four groups at PND 19: WT mice + control diet, WT mice + 2BAct diet, Jimpy mice + control diet and Jimpy mice + 2BAct diet. d Representative EM images of axons in corpus callosum from four groups at PND19. e Quantification of the number of ASPA+ oligodendrocytes in corpus callosum (n = 5 mice/group). p < 0.0001 (WT+Ctrl vs Jimpy+Ctrl), p = 0.0006 (Jimpy+Ctrl vs Jimpy+2BAct). f Quantification of the number of myelinated axons in corpus callosum (n = 4 mice/WT+Ctrl, 3 mice/WT+2BAct, 4 mice/Jimpy+Ctrl, 5 mice/Jimpy+2BAct). p = 0.0008 (WT+Ctrl vs Jimpy+Ctrl), p = 0.0013 (Jimpy+Ctrl vs Jimpy+2BAct). Values are mean ± SEM. ns - non-significant, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Groups were compared using two-tailed unpaired Welch’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

a Representative images of PDGFRα and Ki67 staining of corpus callosum from four groups mice at PND 19: WT mice + control diet, WT mice + 2BAct diet, Jimpy mice + control diet and Jimpy mice + 2BAct diet. Arrow heads point to the examples of PDGFRα+ Ki67+ cells. b Representative images of NG2, Olig2 and EdU staining of corpus callosum from the same groups of mice. c Quantification of the number of PDGFRα+ OPCs in corpus callosum (n = 5 mice/WT+Ctrl, 4 mice/WT+2BAct, 4 mice/Jimpy+Ctrl, 4 mice/Jimpy+2BAct). p = 0.0018 (WT+2BAct vs Jimpy+2BAct). d Quantification of the number of PDGFRα+ki67+ proliferating OPCs in corpus callosum (n = 5 mice/WT+Ctrl, 3 mice/WT+2BAct, 4 mice/Jimpy+Ctrl, 4 mice/Jimpy+2BAct). p = 0.0001 (WT+Ctrl vs Jimpy+Ctrl), p = 0.011 (WT+2BAct vs Jimpy+2BAct). e Quantification of the number of NG2+ OPCs in corpus callosum (n = 3 mice/group). f Quantification of the number of EdU+Olig2 + NG2+ proliferating OPCs in corpus callosum (n = 3 mice/group). Values are mean ± SEM. ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Turkey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

RNAseq pathways: Perk rescues myelination whereas 2BAct targets inflammation

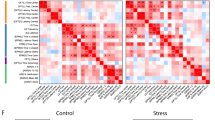

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutants on Jimpy mice, we performed bulk RNAseq analysis of brain samples from Perkfl/fl, Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre, Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice and Jimpy; Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre mice at PND19. There were 893 significantly upregulated genes and 629 significantly downregulated genes in Jimpy mice on the Perkfl/fl background (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl) compared to Perkfl/fl mice, and the introduction of Olig2-driven PERK knockout into Jimpy mice elicited significant upregulation of 112 genes and significant downregulation of 22 genes as compared to Jimpy mice (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl) (Fig. 6a, b, and Supplementary Data 1). Notably, several myelin sheath-related genes (Mbp, Plp1, Mag, Mog and Mobp) as well as genes related to oligodendrocyte terminal differentiation (Klk6, Opalin, and Ermn) were downregulated in Jimpy mice (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl) but rescued by the oligodendrocyte-specific PERK knockout in Jimpy Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre mice (Fig. 6c). Indeed, gene set enrichment analyzes indicated that the top downregulated gene sets in Jimpy mice (Jimpy; Perkfl/fl) compared to Perkfl/fl control mice included those related to oligodendrocytes, glial cell differentiation, and cholesterol biosynthesis, and these changes were rescued by the oligodendrocyte-specific PERK knockout (Fig. 6d, e, and Supplementary Data 2). Notably, we did not observe significant changes in the ER stress pathways and UPR response in Jimpy mice, perhaps because so few oligodendrocytes remain at this stage. The oligodendrocyte-specific PERK knockout Jimpy mice, however, showed upregulated gene sets involved in ER protein folding. This includes several target genes from the ATF6 pathway (Hspa5 and Hsp90b1) and the IRE1 pathway (Hspa5 and P4hb), the other arms of the UPR (Fig. 6f). In line with these findings, increased immunofluorescent intensities of ATF6, GRP78 (Hspa5) and GRP94 (Hsp90b1) were observed in Olig2+ cells of Jimpy mice lacking Perk in oligodendrocytes, with GRP78 and GRP94 reaching significance (Supplementary Fig. 7a–c,e–g). To assess ISR pathway activation, we queried the expression of a panel of 95 ISR target genes identified by Clustering by Inferred Co-Expression (referred to as ISR CLIC)53. We found that the ISR CLIC gene set was significantly upregulated in Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice compared to control mice and downregulated by PERK knockout in Jimpy Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre mice (Fig. 6e). Consistently, the volcano plots of ISR CLIC genes showed that the ISR gene Trib3 was upregulated in Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice compared to Perkfl/fl control mice and downregulated in Jimpy Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre mice. The significant changes were also reflected in immunostaining (Supplementary Fig. 7d, h). In contrast, Atf3 was upregulated in Jimpy; Perkfl/fl mice and further increased in Jimpy Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre mice (Fig. 6g, h, and Supplementary Data 3). The upregulation of ATF3 has been associated with inflammation that is not always dependent on ISR induction53.

Volcano plots highlighting significant (FDR < 0.05, Log2FC > 0.5) differentially expressed genes between Jimpy;Perkfl/fl and Perkfl/fl (a) and between Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl brains at PND 19 (b). c Expression changes in individual genes associated with myelin sheath formation and oligodendrocyte differentiation. *adj-p < 0.05, **adj-p < 0.01, ***adj-p < 0.001, ****adj-p < 0.0001 in Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl comparison. Gene set enrichment analysis of MSigDB C2 and C5 gene sets (d), and ISR and Hallmark gene sets (e) in Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Perkfl/fl and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl comparisons. f FPKM of ATF6 and IRE1 target genes in Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre and Jimpy;Perkfl/fl (n = 4 mice/group). Values are mean ± SEM. *p = 0.0219 (Hspa5), **p = 0.0059 (Hsp90b1), *p = 0.0159 (Pdia3), **p = 0.005 (P4hb). Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Groups were compared using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Volcano plots highlighting ISR CLIC genes in Jimpy;Perkfl/fl vs Perkfl/fl (g) and in Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre vs Jimpy;Perkfl/fl brains at PND 19 (h), significantly changed (FDR < 0.05, Log2FC > 0.5) ISR CLIC genes denoted in dark red. n = 3 (Perkfl/fl mice), n = 4 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice) and n = 4 (Jimpy;Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre). For (a, b, g, h), differential expression was determined using a two-sided, moderated t-test with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons. For (d, e), gene set enrichment was analyzed using a two-sided, competitive gene set test CAMERA with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We also characterized the effect of pharmacologically inhibiting the ISR in Jimpy mice through RNAseq analysis of brain samples from WT and Jimpy mice on control or 2BAct-supplemented diets at PND19. We identified 107 significantly upregulated genes and 315 significantly downregulated genes in Jimpy mice on control diet vs WT mice on control diet (Fig. 7a, and Supplementary Data 4). When Jimpy mice were on the 2BAct diet, 91 genes were significantly upregulated, and 98 genes significantly downregulated compared to control diet (Fig. 7b, and Supplementary Data 4). Though several myelin-related oligodendrocyte terminal differentiation genes were significantly rescued by 2BAct diet in Jimpy mice, the extent of these fold changes was relatively small compared to the rescue observed in oligodendrocyte-specific PERK mutant Jimpy mice (Figs. 6c and 7c). Notably, gene set enrichment analysis indicated that 2BAct significantly reversed inflammatory responses affected by the Jimpy mutation, including immature neutrophils and interferon gamma and interferon alpha pathways (Fig. 7d, e, and Supplementary Data 5). Consistent with these findings, immunostaining of the corpus callosum showed that 2BAct significantly reduced microglial activation at PND19, although no remarkable change was observed in astrocytes of Jimpy mice (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, unlike the oligodendrocyte-specific PERK mutant, 2BAct did not rescue the gene sets associated with oligodendrocytes, glial cell differentiation, or cholesterol homeostasis, (Figs. 6d,e, and 7d,e). Like the PERK mutant, 2BAct significantly downregulated the ISR CLIC gene set (Fig. 7e–g, and Supplementary Data 6).

Volcano plots highlighting significant (FDR < 0.05, Log2FC > 0.5) differentially expressed genes in the brains between Jimpy+control diet and WT+control diet (a) and between Jimpy+2BAct diet and Jimpy+control diet at PND 19 (b). c Expression changes in individual genes associated with myelin sheath formation and oligodendrocyte differentiation. *adj-p < 0.05, **adj-p < 0.01, ***adj-p < 0.001 in Jimpy+2BAct diet vs Jimpy+control diet comparison. Gene set enrichment analysis of MSigDB C2 and C5 gene sets (d), and ISR and Hallmark gene sets (e). Volcano plots highlighting ISR CLIC genes in Jimpy+control diet vs WT+control diet (f) and in Jimpy+2BAct diet vs Jimpy+control diet comparisons at PND 19 (g), significantly changed (FDR < 0.05, Log2FC > 0.5) ISR CLIC genes denoted in dark red. n = 3 mice/WT+ control group, n = 4 mice/Jimpy+control group, n = 3 mice/WT+2BAct group, n = 3 mice/Jimpy+control group. For (a, b, f, g), differential expression was determined using a two-sided, moderated t-test with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons. For (d, e), gene set enrichment was analyzed using a two-sided, competitive gene set test CAMERA with Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In addition, we analyzed the differentially expressed genes in Jimpy mice at earlier timepoints, PND7 and PND14, on 2BAct-medicated versus control diets (Supplementary Fig. 9). These analyzes indicate that there are more significantly changed genes at PND7 (n = 735 in Jimpy control vs WT control diet; n = 2056 in Jimpy 2BAct vs Jimpy control diet) and PND14 (n = 5558 in Jimpy control vs WT control diet; n = 5217 in Jimpy 2BAct vs Jimpy control diet) compared to PND19 (Supplementary Fig. 9a–d, and Supplementary Data 4). At PND7, cholesterol biogenesis, as well as hallmark cell cycle-related gene sets, such as E2F transcription factor target sets and G2M checkpoint genes were upregulated in 2BAct-treated Jimpy mice as compared to control diet (Supplementary Fig. 9e, g, and Supplementary Data 5). At PND14, the most significantly upregulated gene sets in Jimpy mice included development-related sets such as MYC targets and gene sets related to ion channel activities. Treatment with 2BAct significantly attenuated the expression of these gene sets in Jimpy mice (Supplementary Fig. 9f, h, and Supplementary Data 5). Notably, and in contrast with PND19, the ISR CLIC genes as a set did not show significant enrichment in Jimpy mice over WT mice on a control diet at PND7 and PND14 (Fig. 7e), nor was the signature significantly altered by 2BAct diet in Jimpy mice. However, many individual ISR genes that were significantly up- or downregulated in Jimpy mice versus WT mice on control diets were significantly reversed in Jimpy mice on the 2BAct-supplemented diet (Supplementary Fig. 10a–f, and Supplementary Data 6).

Together, the RNAseq data demonstrated that both oligodendrocyte-specific Perk inactivation and 2BAct can attenuate the upregulated ISR pathways in Jimpy mice at PND 19. In addition, the Perk mutation rescued the gene sets related to oligodendrocyte markers, glial cell differentiation, and cholesterol homeostasis, while 2BAct partially attenuated these markers but mainly reversed inflammation related responses in PND19 Jimpy mice.

ISR inhibition promotes Jimpy oligodendrocyte maturation in vitro

To further assess the impact of cell autonomous eIF2B activation on Jimpy oligodendrocytes, we examined oligodendrocyte differentiation in vitro in the presence ISRIB, which is a 2BAct analog that has a longer half-life in cell culture media54. OPCs were isolated from postnatal day 5 to 7 Jimpy pups and, after expansion in proliferation media supplemented with PDGFA, were placed in differentiation media containing either vehicle or increasing concentrations of ISRIB (1 μM, 2.5 μM or 5 μM). After 48 h (day 2), Jimpy oligodendrocytes in either control or ISRIB-containing differentiation media expressed MBP and extended branched processes (Supplementary Fig. 11a). However, by 72 h (day 3), few MBP+ oligodendrocytes were present in the Jimpy control cultures, whereas the ISRIB treated cells displayed numerous MBP+ cells that continued to mature over the next 2 days of culture (Fig. 8, and Supplementary Fig.11a). The ISRIB rescue of the Jimpy oligodendrocytes occurred in a dose-dependent manner with the most significant changes occurring at a concentration of 5 μM ISRIB (Fig. 8b, c). At day 4 and day 5 in differentiation media, Jimpy cultures treated with 5 μM ISRIB contained over 50% of the number of MBP+ oligodendrocytes observed in the WT cultures (Fig. 8a–c). Notably, ISRIB did not alter the density of oligodendrocytes in WT cultures (Supplementary Fig. 11b, c). These data demonstrate a cell-autonomous impact of ISR inhibition on oligodendrocyte differentiation and survival.

a Representative images of MBP of cultured WT and Jimpy oligodendrocytes in the presence of DMSO or 5 µM of ISRIB at day 4 and day 5. b Quantification of the number of MBP+ cells in culture exposed to DMSO or different concentrations of ISRIB (1 µM, 2.5 µM and 5 µM) at day 4. n = 4 biological replicates. p < 0.0001 (WT DMSO vs Jimpy DMSO), p = 0.001 (WT DMSO vs Jimpy 1 µM), p = 0.017 (WT DMSO vs Jimpy 2.5 µM). c Quantification of the number of MBP+ cells in culture exposed to DMSO or different concentrations of ISRIB (1 µM, 2.5 µM and 5 µM) at day 5. Biological replicates were n = 4 for all groups, except Jimpy cells treated with 5 µM of ISRIB (n = 3). p < 0.0001 (WT DMSO vs Jimpy DMSO, WT DMSO vs Jimpy 1 µM, WT DMSO vs Jimpy 2.5 µM), p = 0.0022 (WT DMSO vs Jimpy 5 µM). Values are mean ± SEM. ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Groups were compared using one-way ANOVA with Turkey post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

PMD is caused by mutations in the PLP1 gene and is characterized by the widespread developmental loss of oligodendrocytes, which leads to severe CNS hypomyelination resulting in a calamitous clinical condition3. PLP is an abundantly expressed multi-pass membrane protein found in CNS myelin. Peripheral nerve function is generally normal in patients with PMD, which likely reflects the dramatically lower level of PLP expression by Schwann cells55. A myriad of PMD mutations in the PLP1 gene disrupt the transport of the protein through the secretory pathway of oligodendrocytes, resulting in activation of the UPR, which includes the PERK branch that phosphorylates eIF2α, inducing the ISR56. Therapeutic strategies that would protect oligodendrocytes from the devastating impact of mutant PLP expression would likely provide considerable benefit7. In the current study, we have examined the effect of manipulating the ISR on the PMD mouse model, Jimpy, showing that ISR inhibition protects Jimpy oligodendrocytes, allowing for increased CNS myelination, reduced axonal damage, and a significantly extended lifespan.

Previously, we have shown that oligodendrocytes from mice heterozygous for a Perk null mutation display dramatically increased sensitivity to the presence of IFN-γ in the CNS25. Moreover, mice homozygous for an oligodendrocyte-specific Perk mutation are significantly more sensitive to EAE induction, which correlates with increased oligodendrocyte death34. Here, we observed a significantly increased lifespan of Jimpy mice and enhanced oligodendrocyte survival when the Perk gene was specifically inactivated in Jimpy oligodendrocytes. Consistent with these results, a previous study using oligodendrocytes derived from PMD patients’ human pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) observed that the PERK inhibitor GSK2656157 mobilized PLP into cell processes and restored cell morphology8. The analysis of distinct models of oligodendrocyte dysfunction provides insight into the function of the ISR in cells faced with diverse cytotoxic insults. Inflammation creates a relative mild and usually transient cytotoxic environment, against which the ISR can provide short-term protection. In this context, an enhanced or prolonged ISR can be beneficial. In contrast, mutations in the abundantly expressed Plp1 gene result in a continuous source of improperly folded mutant proteins in the ER that activates a maladaptive UPR, resulting in the programmed cell death of the mutant oligodendrocytes. This chronic ISR, the PERK branch of the UPR, also suppresses cholesterol biosynthesis, thereby affecting oligodendrocyte maturation57. Inhibiting the ISR in this setting provides protection to chronically stressed oligodendrocytes and preserves their capacity for maturation. Although ISR activation leads to a cytoprotective reduction of overall protein synthesis, including presumably the mutant PLP1 protein, inhibiting the maladaptive ISR response appears to provide protection to Jimpy mice.

The MBP immunostaining observed in Jimpy mice is somewhat enigmatic, since these mice lack detectable CNS myelin by EM, which represents the gold standard for myelin quantification. This suggests that the increased MBP immunoreactivity observed in Jimpy animals with a reduced ISR response may not exclusively reflect enhanced myelination. One possibility is that the MBP signal in these animals may originate, at least in part, from microglia. Previous studies have demonstrated that microglia can engulf MBP transcripts during development and in demyelinating disorders58,59. These transcripts may be translated within Jimpy microglia, thereby contributing to the observed MBP immunoreactivity.

Although the inactivation of the Perk gene resulted in a substantial increase in Jimpy lifespan, which correlated with increased oligodendrocyte survival and CNS myelination, inactivation of the downstream ISR factor GADD34 had no impact on Jimpy mouse survival or neuropathology. GADD34 is a PP1 phosphatase co-factor that dephosphorylates P-eIF2α, such that its inactivation prolongs the ISR45. Therefore, it is not particularly surprising that its absence is not beneficial since the ISR has a clear detrimental impact on Jimpy oligodendrocytes. Another ISR downstream target CHOP has been shown to be a pro-apoptotic factor that is thought to mediate the maladaptive response of the ISR47; therefore, it might be expected that its inactivation would diminish oligodendrocyte cell death. We showed here that genetically deleting Chop slightly extended the lifespan of Jimpy mice but had no impact on oligodendrocyte survival. A previous study showed that CHOP has an anti-apoptotic impact on oligodendrocytes that express a distinct mutant Plp1 allele60,61. These results indicate that the ISR has the potential to activate CHOP-independent cell death pathways, perhaps in a cell type specific manner55.

OPCs are abundant oligodendrocyte precursors found throughout the CNS42. In addition to serving as the source of oligodendrocytes during development, these cells have the capacity to differentiate into myelinating cells to replace lost oligodendrocytes in adults. OPC differentiation triggers a mitotic response, ensuring that OPC numbers are replenished43. Therefore, we expected that in Jimpy mutants there would be a continuous effort to replace the dying oligodendrocytes, resulting in an increase in homeostatic OPC proliferation. We were surprised to find that although the number of OPCs remained constant in Jimpy mice relative to WT controls, the percentage of mitotic OPCs was decreased in the mutant animals. Inhibition of the ISR rescued the number of mitotic OPCs to some extent, but not to control levels. Since our previous work demonstrated that PERK activity is not required for oligodendrocyte development or myelination, the increased OPC proliferation observed here is unlikely to be intrinsically driven by the PERK mutation34,35. One possibility is that the mutant PLP-induced oligodendrocyte death leads to an extensive, continuous effort to replace these cells, exhausting the mitotic capacity of the precursor cells.

RNAseq analysis of Jimpy CNS revealed an upregulation of ISR gene sets, accompanied by reduced expression of genes related to cholesterol synthesis, myelin formation and oligodendrocyte differentiation. This transcriptional profile is consistent with findings from a recent vanishing white matter disease (VWMD) model, which identified impaired cholesterol biosynthesis as a critical output of sustained ISR activation in oligodendrocytes57. Importantly, inactivating Perk in oligodendrocytes resulted in a reduction of the ISR pathway in Jimpy mice and rescued these transcriptional markers, aligning with the observation of improved oligodendrocyte survival and myelin integrity. In particular, the ISR gene Trib3 was significantly downregulated in oligodendrocyte specific Perk mutant Jimpy mice. TRIB3, regulated by ATF4-CHOP, contributes to the induction of apoptosis by inhibiting the protein kinase AKT62,63. It will be particularly interesting to explore the precise molecular impact of TRIB3/AKT on cell death and whether loss of TRIB3 may contribute to oligodendrocyte survival in the Jimpy model. Conversely, another ISR gene, Atf3, was upregulated in Jimpy mice and even more so in Perk knockout Jimpy mice. ATF3 can be induced during ER stress and other stress conditions and is thought to be a pro-apoptotic factor in conjunction with CHOP64. However, it was previously shown that the Atf3 null mutation had no effect on oligodendrocyte death and animal lifespan in two distinct PMD mouse models65. Perhaps ATF3 executes CNS protection by regulating other pathways in addition to the UPR, such as regulating the inflammatory response53,66,67. Additionally, the upregulation of the IRE1 and ATF6 of UPR arms, suggests a compensatory effect to restore proteostasis in oligodendrocytes lacking PERK.

In 2BAct-treated Jimpy mice, age-dependent changes in gene expression were revealed by RNAseq. Pathways related to development and the cell cycle were largely affected by 2BAct treatment in the early stages (PND7 and 14), but the ISR pathway was attenuated at PND19. Interestingly, 2BAct partially rescued oligodendrocyte markers as well as differentiation genes, and also reduced certain inflammatory responses at PND19. Activation of an immune response has been observed in PMD autopsy samples and PMD mouse models44,68. Although direct research is limited, it is possible that 2BAct regulates the immune response by influencing the ISR pathways in the immune cells in Jimpy mice. Alternatively, other cell types that develop an ISR might have a non-cell autonomous impact on the immune cells. Future studies incorporating single-cell sequencing may reveal additional cell-specific mechanisms.

There are no FDA-approved therapies for PMD. Nevertheless, cell transplantation studies have shown promise in providing clinical benefit to PMD infants5. Human CNS stem cells (HuCNS-SCs) were surgically implanted into the frontal lobe white matter of a few early-onset PMD patients, and most of the recipients showed some gains in neurological function, albeit modest, and MRI revealed persistent HuCNS-SC engraftment and donor-derived myelin4,69. More recently, an antisense oligonucleotide approach to the Plp1 mRNA has shown exciting potential6. Mouse Plp1 null mutants and human patients with PLP1 deletions display relatively mild neurological symptoms, suggesting that the PMD mutant alleles have a dominant adverse impact on oligodendrocyte function10,70. Therefore, the suppression of mutant PLP expression should provide benefit. This possibility was confirmed in the study from the Tesar group that demonstrated that a single dose of an antisense Plp oligonucleotide rescued most symptomatic parameters of the Jimpy mouse mutant, including oligodendrocyte numbers, CNS myelin, and lifespan6. These cell and genetic therapeutic approaches have great promise, and it will be exciting to follow their development in the clinic. In combination with these approaches, it could prove useful to implement a pharmacological approach to inhibit the ISR to prolong the lifespan of the mutant PMD oligodendrocytes. Fosigotifator, an eIF2B clinical candidate, is currently in clinical trial for another leukodystrophy, VWMD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05757141). ISR inhibition could provide sufficient time for the cell and genetic therapies to become effective. Combination therapies might ultimately provide further clinical benefit to PMD patients.

Methods

Mouse lines and survival study

All animal experiments were executed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine (IS00027307). Heterozygous Jimpy (Plp1jp) female mice were kindly provided by Paul Tesar, and the Perk heterozygous, Chop null and Gadd34ΔC/ΔC mice were a generous gift of David Ron. The Perkfl/fl mice were obtained from Douglas Cavener, and the Olig2-Cre mice were a gift from David Rowitch. Jimpy female mice were crossed with either Perk+/−, Perkfl/fl, Chop−/− or Gadd34ΔC/ΔC to generate Jimpy;Perk+/−, Jimpy;Perkfl/fl, Jimpy;Chop−/−, and Jimpy; Gadd34ΔC/ΔC mice. Jimpy;Perkfl/fl mice were then crossed with Olig2-Cre mice to produce Jimpy;Perkfl/fl; Olig2-Cre, in which the Olig2 promotor driven Cre recombinase inactivates Perk specifically in oligodendrocytes. All mice were housed in temperature-controlled specific pathogen–free facilities under 12-h light–dark cycles in the Center for Comparative Medicine at Northwestern University. Only male mice were used in the experiments. The survival study endpoint was defined by the signs of moribundity, including but not limited to lateral recumbency or immobility, lack of response to stimulation, inability to eat or drink and hypothermia71.

Drugs

eIF2B activators 2BAct and ISRIB were provided by Calico Life Sciences LLC. Pregnant female Jimpy mice were exposed to 100 mg/kg of 2BAct in chow, with exposure continuing for both the dams and pups after birth. Identical animal chow without 2BAct was used as control. ISRIB was first dissolved in DMSO, and final concentrations of working solution in cell culture medium were 1 μM, 2.5 μM and 5 μM.

OPC isolation and cell culture

OPCs were isolated and purified following a immunopanning method72. Briefly, mouse brain cortices from 5 to 7 Jimpy or WT pups were collected and digested with papain (#9001734, Worthington) at 37 °C. Cells were triturated, suspended, and sequentially immunopanned on plates coated with Ran-2, GalC, and O4 antibodies from a hybridomal supernatant. OPCs adhering to the anti-O4 coated plate were trypsinized and seeded on poly-D-Lysine-coated plates in growth media supplemented with PDGFRA (#100-13A, PeproTech) for proliferation. After expansion, cells were plated into differentiating medium supplemented with T3 (#T6397, Sigma) in the presence or absence of ISRIB.

Immunofluorescence and immunocytochemistry

Male mice were anaesthetized by 1.2% avertin and transcardially perfused first with 0.9% NaCI followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (#158127, Sigma). Brains were harvested, post-fixed with 4% PFA overnight and embedded in O.C.T compound (#4853, Sakura Finetek). Sagittal cerebral frozen sections were prepared in a series of 10 μm on a cryostat. Tissue sections or fixed cell culture were incubated with primary antibodies against ASPA (1:1000; #GTX13389, Genetex), MBP(1:50; #ab24567, Abcam), PDGFRα (1:50; #AF1062, R&D), Ki67(1:100; #ab15580, Abcam), CC1 (1:100; OP80, Millipore), NG2 (1:100, Dwight Bergles’s house antibody), Olig2 (1:500; #AB9610, Millipore), NF-L-DegenoTag (1:1000; #MCA-6H63, Encor Biotech), IBA1 (1:500, #81728-1RR, Proteintech), GFAP (1:200, #AB5541, Millipore), cleaved caspase 3 (1:400, #9661S, Cell signaling), BCAS1 (1:1000, #445003, Synaptic Systems), ATF6a (1:50, #sc-166659, Santa Cruz), GRP94 (1:200, #10979-1-AP, Proteintech), Bip (1:100, #sc-166490, Santa Cruz), and TRIB3 (1:50, #A01414, Boster Bio) followed by appropriate species-specific fluorescent labeled secondary antibodies mounting and cover-slipping with HardSet™ Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (#H-1500-10, VECTASHIELD). The sections were scanned with a fluorescent research slide scanner (VS200, Evident). For tissue section staining, the number of immunopositive cells from at least five serial brain sections was quantified in each animal. For oligodendrocyte culture staining, numbers of MBP+ cells were counted in multiple image fields of culture from at least 3 different animals for each condition. The quantification was performed on Image J analysis software (NIH Image software) and Halo image analysis software (Indica Labs). The representative images were acquired under a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope.

EdU labeling

Labeling of dividing OPCs was carried out by intraperitoneal injection of EdU (5-ethynyal-2-deoxyuridine, # 900584, Sigma) into Jimpy mice at 5 mg/kg body weight on PND 17 and PND18. Brain tissues were harvested on PND19. EdU staining was performed free-floating by treating the 35 μm of frozen section at room temperature with the EdU Click-it reaction kit (#C10340, Molecular Probes) and the Alexa fluor 647 dye (#A20006, ThermoFisher) for 30 min after the standard immunofluorescence.

Electron microscopy (EM)

Male mice were anaesthetized by 1.2% avertin and transcardially perfused with EM fixative made of 2.5% glutaraldehyde (#00710-5, Polysciences), 4% PFA in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (#11652, EMS) buffer at pH 7.4. After 2 weeks of fixation at 4 °C, brains were dissected, washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate and then postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (# 19152, EMS) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate. Sections were then dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol followed by incubation in propylene oxide (PO, #20401, EMS). Samples were then infiltrated with increasing ratio of PO: Epon-812 resin mixture (1:1 and 1:2, 2 h each), following by immersion of 100% Epon-812 resin mixture overnight. Epon 812 resin mixture was prepared using EMBed-812 (#14900, EMS), DDSA (#13710, EMS), NMA (#19000, EMS), and BDMA (#11400, EMS). Tissue were embedded in fresh Epon-812 resin mixture and polymerized at 60 °C for 48 h. Semi-thin sections (1 μM thickness) were stained with toluidine blue, and then samples were ultrathin (60–90 nM thickness) sectioned on a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome. Grids containing ultrathin sections were examined on a FEI Tecnai Spirit G2 transmission electron microscope. Axon counts were performed using Image J and averaged from 10 images (area per image = 240 μm2) in each mouse.

Western-blot

Male mice were anaesthetized by 1.2% avertin and transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS and then homogenized in cold RIPA buffer (#R0278, Sigma) containing Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (#PI78441, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a motorized homogenizer. Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. A total 30 μg of protein lysates was separated by SDS-PAGE (#4561095, Bio-Rad) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Fig. 2e). The blots were incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-MBP (1:1000; # 808403, BioLegend), anti-MAG (1:1000; #346200, Invitrogen), and anti-β-actin (1:2000; # A2066, Sigma-Aldrich). The blots were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000; Invitrogen) and the signals were detected by chemiluminescence on a Bio-Rad ChemiDocTM Imager. The bands were analyzed using Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad).

RT- qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from brain tissue samples of PND 19 mice using AurumTM total RNA fatty and fibrous tissue kit (#7326830, Bio-Rad). Reverse transcription was performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (#1708891, Bio-Rad). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR was performed on a CFX96 RT-PCR detection system using SYBR Green technology (#1725271, Bio-Rad). The relative gene expression levels were normalized to that of the housekeeping gene Gapdh. The primer sequences of the target genes were as follows: Mbp-f: TGTCACAATGTTCTTGAAGAAATGG, Mbp-r: TGTCACAATGTTCTTGAAGAAATGG; Mag-f: CTGCTCTGTGGGGCTGACAG, Mag-r: AGGTACAGGCTCTTGGCAACTG; Cnp-f: CTCTACTTTGGCTGGTTCCTGAC,

Cnp-r: GCTTCTCCTTGGGTTCATCTCC; Gapdh-f: TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA; Gapdh-r: TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGGA.

RNAseq and analysis

To analyze the effect of Perk mutation on Jimpy mice, mouse brains from four different mouse lines (Perkfl/fl, Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre, Jimpy; Perkfl/fl, Jimpy; Perkfl/fl;Olig2-Cre) were harvested at PND19. To analyze the 2BAct effect on Jimpy mice, mouse brains from four groups of mice (WT control diet, WT 2BAct, Jimpy control diet, and Jimpy 2BAct) were harvested at PND 7, PND 14 and PND 19. RNA was extracted from brain tissues, and the stranded total RNA-seq was conducted in the Northwestern University NUSeq Core Facility. Briefly, total RNA examples were checked for quality on Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 and quantity with Qubit fluorometer. The Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep, Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus kit was used to prepare sequencing libraries. The kit procedure was performed without modifications. This procedure includes rRNA depletion, remaining RNA purification and fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, 3′ end adenylation, Illumina adapter ligation, library PCR amplification and validation. lllumina HiSeq 4000 Sequencer was used to sequence the libraries with the production of single-end, 50 bp reads. The quality of DNA reads, in fastq format, was evaluated using FastQC. Adapters were trimmed, and reads of poor quality or aligning to rRNA sequences were filtered. The cleaned reads were aligned to the Mus musculus genome (mm10) using STAR73. Read counts for each gene were calculated using htseq-count74 in conjunction with a gene annotation file for mm10 obtained from UCSC (University of California Santa Cruz; http://genome.ucsc.edu). For differential gene expression analysis, we used the limma-voom pipeline75 to normalize data, define contrasts, and to fit a linear model. edgeR’s “filterByExpr” function was used to determine genes with sufficiently large counts to retain for statistical analysis, and the “calcNormFactors” function was used to calculate TMM scaling factors for each sample. Observational-level weights were computed using limma’s “voomWithQualityWeights” function to prepare data for linear modeling using the “lmFit” and “eBayes” functions. Differential expression results were used as input for the “seas” function (with parameters: methods = ‘camera’, feature.max.padj = 0.05, feature.min.logFC = 0.5, inter.gene.cor = 0.01, feature.bias = “size”) in the sparrow R package76 to test for enrichment of Hallmark, C2, and C5 gene sets from the Molecular Signatures Database77.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 10 was used to perform statistical analyzes. All results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance for these data was determined by Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test, unpaired t-tests/Welch test, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey post hoc test for multiple group experiments, two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Significance levels were set at p < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The RNA-seq raw data of mice generated in this study can be accessed at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the access code GSE277705. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wolf, N. I., Ffrench-Constant, C. & van der Knaap, M. S. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies - unravelling myelin biology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 17, 88–103 (2021).

Bonkowsky, J. L. et al. The burden of inherited leukodystrophies in children. Neurology 75, 718–725 (2010).

Khalaf, G. et al. Mutation of proteolipid protein 1 gene: from severe hypomyelinating leukodystrophy to inherited spastic paraplegia. Biomedicines 10, 1709 (2022).

Gupta, N. et al. Long-term safety, immunologic response, and imaging outcomes following neural stem cell transplantation for Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Stem Cell Rep. 13, 254–261 (2019).

Osorio, M. J. et al. Concise review: stem cell-based treatment of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Stem Cells 35, 311–315 (2017).

Elitt, M. S. et al. Suppression of proteolipid protein rescues Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Nature 585, 397–403 (2020).

Elitt, M. S. & Tesar, P. J. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease: on the cusp of myelin medicine. Trends Mol. Med. 30, 459–470 (2024).

Nevin, Z. S. et al. Modeling the mutational and phenotypic landscapes of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease with human iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 617–634 (2017).

Sistermans, E. A., de Coo, R. F., De Wijs, I. J. & Van Oost, B. A. Duplication of the proteolipid protein gene is the major cause of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Neurology 50, 1749–1754 (1998).

Garbern, J. Y. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease: genetic and cellular pathogenesis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 64, 50–65 (2007).

Nave, K. A. & Milner, R. J. Proteolipid proteins: structure and genetic expression in normal and myelin-deficient mutant mice. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 5, 65–91 (1989).

Ruskamo, S. et al. Human myelin proteolipid protein structure and lipid bilayer stacking. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 79, 419 (2022).

Clayton, B. L. L. & Popko, B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in disorders of myelinating glia. Brain Res. 1648, 594–602 (2016).

Costa-Mattioli, M. & Walter, P. The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science 368, eaat5314 (2020).

Pavitt, G. D. & Ron, D. New insights into translational regulation in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a012278 (2012).

Walter, P. & Ron, D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334, 1081–1086 (2011).

Hetz, C. & Papa, F. R. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol. Cell 69, 169–181 (2018).

Duncan, I. D. The PLP mutants from mouse to man. J. Neurol. Sci. 228, 204–205 (2005).

Duncan, I. D., Kondo, Y. & Zhang, S.-C. The myelin mutants as models to study myelin repair in the leukodystrophies. Neurotherapeutics 8, 607–624 (2011).

Dautigny, A. et al. The structural gene coding for myelin-associated proteolipid protein is mutated in jimpy mice. Nature 321, 867–869 (1986).

Nave, K. A. & Boespflug, O. X-linked developmental defects of myelination: from mouse mutants to human genetic diseases. Neuroscientist 2, 33–43 (1996).

Sidman, R. L., Dickie, M. M. & Appel, S. H. Mutant mice (quaking and jimpy) with deficient myelination in the central nervous system. Science 144, 309–311 (1964).

Meier, C. & Bischoff, A. Oligodendroglial cell development in jimpy mice and controls. An electron-microscopic study in the optic nerve. J. Neurol. Sci. 26, 517–528 (1975).

Southwood, C. & Gow, A. Molecular pathways of oligodendrocyte apoptosis revealed by mutations in the proteolipid protein gene. Microsc. Res. Tech. 52, 700–708 (2001).

Lin, W., Harding, H. P., Ron, D. & Popko, B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates the response of myelinating oligodendrocytes to the immune cytokine interferon-gamma. J. Cell Biol. 169, 603–612 (2005).

Lin, W. & Popko, B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disorders of myelinating cells. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 379–385 (2009).

Chen, Y. et al. Sephin1, which prolongs the integrated stress response, is a promising therapeutic for multiple sclerosis. Brain 142, 344–361 (2019).

Way, S. W. et al. Pharmaceutical integrated stress response enhancement protects oligodendrocytes and provides a potential multiple sclerosis therapeutic. Nat. Commun. 6, 6532 (2015).

Way, S. W. & Popko, B. Harnessing the integrated stress response for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 15, 434–443 (2016).

Pakos-Zebrucka, K. et al. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 17, 1374–1395 (2016).

Harding, H. P. et al. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in perk-/- mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol. Cell 7, 1153–1163 (2001).

Zhang, P. et al. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 3864–3874 (2002).

Zawadzka, M. et al. CNS-resident glial progenitor/stem cells produce Schwann cells as well as oligodendrocytes during repair of CNS demyelination. Cell Stem Cell 6, 578–590 (2010).

Hussien, Y., Cavener, D. R. & Popko, B. Genetic inactivation of PERK signaling in mouse oligodendrocytes: normal developmental myelination with increased susceptibility to inflammatory demyelination. Glia 62, 680–691 (2014).

Clayton, B. L., Huang, A., Kunjamma, R. B., Solanki, A. & Popko, B. The integrated stress response in hypoxia-induced diffuse white matter injury. J. Neurosci. 37, 7465–7480 (2017).

Traka, M. et al. Nur7 is a nonsense mutation in the mouse aspartoacylase gene that causes spongy degeneration of the CNS. J. Neurosci. 28, 11537–11549 (2008).

Fard, M. K. et al. BCAS1 expression defines a population of early myelinating oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaam7816 (2017).

Zhou, Q., Wang, S. & Anderson, D. J. Identification of a novel family of oligodendrocyte lineage-specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Neuron 25, 331–343 (2000).

Duncan, I. D., Hammang, J. P., Goda, S. & Quarles, R. H. Myelination in the jimpy mouse in the absence of proteolipid protein. Glia 2, 148–154 (1989).

Shaw, G. et al. Uman-type neurofilament light antibodies are effective reagents for the imaging of neurodegeneration. Brain Commun. 5, fcad067 (2023).

Abdelhak, A. et al. Markers of axonal injury in blood and tissue triggered by acute and chronic demyelination. Brain 148, 3011–3020 (2025).

Bergles, D. E. & Richardson, W. D. Oligodendrocyte development and plasticity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 8, a020453 (2015).

Hughes, E. G., Kang, S. H., Fukaya, M. & Bergles, D. E. Oligodendrocyte progenitors balance growth with self-repulsion to achieve homeostasis in the adult brain. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 668–676 (2013).

Marteyn, A. & Baron-Van Evercooren, A. Is involvement of inflammation underestimated in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease?. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 1572–1578 (2016).

Novoa, I., Zeng, H., Harding, H. P. & Ron, D. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2alpha. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1011–1022 (2001).

Lin, W. et al. Enhanced integrated stress response promotes myelinating oligodendrocyte survival in response to interferon-gamma. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 1508–1517 (2008).

Zinszner, H. et al. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 12, 982–995 (1998).

Marciniak, S. J. et al. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 18, 3066–3077 (2004).

Wek, R. C., Anthony, T. G. & Staschke, K. A. Surviving and adapting to stress: translational control and the integrated stress response. Antioxid. Redox Signal. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2022.0123 (2023).

Sidrauski, C. et al. Pharmacological dimerization and activation of the exchange factor eIF2B antagonizes the integrated stress response. eLife 4, e07314 (2015).

Zyryanova, A. F. et al. ISRIB blunts the integrated stress response by allosterically antagonising the inhibitory effect of phosphorylated eIF2 on eIF2B. Mol. Cell 81, 88–103.e6 (2021).

Maurano, M. et al. Protein kinase R and the integrated stress response drive immunopathology caused by mutations in the RNA deaminase ADAR1. Immunity 54, 1948–1960.e5 (2021).

Wong, Y. L. et al. eIF2B activator prevents neurological defects caused by a chronic integrated stress response. eLife 8, e42940 (2019).

Sidrauski, C., McGeachy, A. M., Ingolia, N. T. & Walter, P. The small molecule ISRIB reverses the effects of eIF2α phosphorylation on translation and stress granule assembly. eLife 4, e05033 (2015).

Garbern, J. Y. et al. Proteolipid protein is necessary in peripheral as well as central myelin. Neuron 19, 205–218 (1997).

Inoue, K. Cellular pathology of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease involving chaperones associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front. Mol. Biosci. 4, 7 (2017).

Lin, K. et al. Chronic integrated stress response causes dysregulated cholesterol synthesis in white matter disease. JCI Insight 10, e188459 (2025).

Li, Q. et al. Developmental heterogeneity of microglia and brain myeloid cells revealed by deep single-cell RNA sequencing. Neuron 101, 207–223.e10 (2019).

Schirmer, L. et al. Neuronal vulnerability and multilineage diversity in multiple sclerosis. Nature 573, 75–82 (2019).

Gow, A. & Wrabetz, L. CHOP and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in myelinating glia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19, 505–510 (2009).

Southwood, C. M., Garbern, J., Jiang, W. & Gow, A. The unfolded protein response modulates disease severity in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Neuron 36, 585–596 (2002).

Ohoka, N., Yoshii, S., Hattori, T., Onozaki, K. & Hayashi, H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J. 24, 1243–1255 (2005).

Luo, H. R. et al. Akt as a mediator of cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11712–11717 (2003).

Ku, H.-C. & Cheng, C.-F. Master regulator activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) in metabolic homeostasis and cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 556 (2020).

Sharma, R., Jiang, H., Zhong, L., Tseng, J. & Gow, A. Minimal role for activating transcription factor 3 in the oligodendrocyte unfolded protein response in vivo. J. Neurochem. 102, 1703–1712 (2007).

Kwon, J.-W. et al. Activating transcription factor 3 represses inflammatory responses by binding to the p65 subunit of NF-κB. Sci. Rep. 5, 14470 (2015).

Khuu, C. H., Barrozo, R. M., Hai, T. & Weinstein, S. L. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) represses the expression of CCL4 in murine macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 44, 1598–1605 (2007).

Southwood, C. M., Fykkolodziej, B., Dachet, F. & Gow, A. Potential For cell-mediated immune responses in mouse models of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Brain Sci. 3, 1417–1444 (2013).

Gupta, N. et al. Neural stem cell engraftment and myelination in the human brain. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 155ra137 (2012).

Klugmann, M. et al. Assembly of CNS myelin in the absence of proteolipid protein. Neuron 18, 59–70 (1997).

Toth, L. A. Defining the moribund condition as an experimental endpoint for animal research. ILAR J. 41, 72–79 (2000).

Dugas, J. C. & Emery, B. Purification and culture of oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013, 810–814 (2013).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq — a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015).

Lianoglou, S. Sparrow: take command of set enrichment analyses through a unified interface. R package version 1.10.1 at https://github.com/lianos/sparrow.

Liberzon, A., Birger, C., Thorvaldsdóttir, H. & Ghandi, M. The molecular signatures database hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Paul Tesar, David Ron, Doug Cavener and David Rowitch for generously providing mouse strains used in the study. We would like to thank Ani Solanki (University of Chicago), Erdong Liu (Northwestern University), Samatha Wills, Alvin Chapagai, Taha Gabr, and Metin Aksu (Loyola University Chicago) for technical support. This research was supported by NIH grants 5R01NS034939 and 1R35NS137478 to B.P. B.P. and D.E.B. are supported by the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and B.P. receives funding from the Rampy MS Research Foundation. Y.C. is the recipient of a National Multiple Sclerosis Society Career Transition Fellowship TA-2008-37043. Imaging work was performed at the Northwestern University Center for Advanced Microscopy generously supported by NCI CCSG P30 CA060553 awarded to the Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C., R.K., L.K., M.D., K.B., I.S., Y.H.C., J.C.Z., J.E.V.B., S.E., and G.N. performed the experiment. K.L. and C.C. analyzed the RNAseq data. Y.C., R.K., D.B., C.S., and B.P. planned the study. Y.C. and B.P. wrote the manuscript with substantial contribution from R.K., K.L., J.E.V.B., D.B., and C.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Brian Popko is on the scientific advisory board of InFlectis Biosciences, which has an interest in modulating the ISR for neurodegenerative disorders. There is no conflict with the current study. Rejani B. Kunjamma, Karin Lin, and Caitlin F. Connelly (at time of contribution) are employees of Calico Life Sciences LLC and have no additional financial interests to declare. Carmela Sidrauski is an employee of Calico Life Sciences LLC and is listed as an inventor on a patent application WO2017193063 describing 2BAct. 2BAct was used in this study to treat Jimpy mice. This composition of matter patent covering 2BAct and related analogs has been published. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Kunjamma, R.B., Lin, K. et al. Integrated stress response inhibition prolongs the lifespan of a Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease mouse model by increasing oligodendrocyte survival. Nat Commun 17, 1285 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68045-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68045-0