Abstract

Cell division and specification are crucial for plant development and coping with diverse environmental cues. Most land plants rely on symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi to cope with soil nutrient limitations by forming arbuscules in root inner cortex cells. What determines the AM susceptibility of these inner cortex cells is currently unknown. Here we show that DELLA transcriptional regulators control the number of inner cortex cells with an AM-susceptible identity at the root stem cell niche of Medicago truncatula in a dose-dependent manner. Genetic analyses suggest that this activity converges with the well-known mobile SHORT-ROOT transcription factor regulating ground tissue development. Furthermore, we show that MtDELLA1 protein moves from the stele/endodermis to the cortex in the mature part of the root to facilitate arbuscule formation. We propose that the formation of a root inner cortex cell identity controlled by mobile DELLA and SHORT-ROOT is a fundamental basis for AM symbiosis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. Biological materials are available on request from the corresponding authors. RNA-seq data are deposited at a public information centre (China National Center for Bioinformation, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/) under BioSample accessions SAMC5252845–SAMC5252850. The M. truncatula A17 genome v.5.0 is available at https://medicago.toulouse.inra.fr/MtrunA17r5.0-ANR/, the Medicago Tnt mutant centre is available at https://medicago-mutant.dasnr.okstate.edu/mutant/index.php and Phytozome v.13 (ref. 64) is available at https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov.

References

Luginbuehl, L. H. & Oldroyd, G. E. D. Understanding the arbuscule at the heart of endomycorrhizal symbioses in plants. Curr. Biol. 27, 952–963 (2017).

Di Ruocco, G., Di Mambro, R. & Dello Ioio, R. Building the differences: a case for the ground tissue patterning in plants. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20181746 (2018).

Xiao, T.-T., van Velzen, R., Kulikova, O., Franken, C. & Bisseling, T. Lateral root formation involving cell division in both pericycle, cortex and endodermis is a common and ancestral trait in seed plants. Development 146, dev182592 (2019).

Limpens, E., van Zeijl, A. & Geurts, R. Lipochitooligosaccharides modulate plant host immunity to enable endosymbioses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 53, 311–334 (2015).

MacLean, A. M., Bravo, A. & Harrison, M. J. Plant signaling and metabolic pathways enabling arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Cell 29, 2319–2335 (2017).

Sieberer, B. J., Chabaud, M., Fournier, J., Timmers, A. C. & Barker, D. G. A switch in Ca2+ spiking signature is concomitant with endosymbiotic microbe entry into cortical root cells of Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 69, 822–830 (2012).

Choi, J., Summers, W. & Paszkowski, U. Mechanisms underlying establishment of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 56, 135–160 (2018).

Floss, D. S., Levy, J. G., Levesque-Tremblay, V., Pumplin, N. & Harrison, M. J. DELLA proteins regulate arbuscule formation in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E5025–E5034 (2013).

Yu, N. et al. A DELLA protein complex controls the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in plants. Cell Res. 24, 130–133 (2014).

Heck, C. et al. Symbiotic fungi control plant root cortex development through the novel GRAS transcription factor MIG1. Curr. Biol. 26, 2770–2778 (2016).

Floss, D. S. et al. A transcriptional program for arbuscule degeneration during AM symbiosis is regulated by MYB1. Curr. Biol. 27, 1206–1212 (2017).

Seemann, C. et al. Root cortex development is fine-tuned by the interplay of MIGs, SCL3 and DELLAs during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. N. Phytol. 233, 948–965 (2022).

Harberd, N. P., Belfield, E. & Yasumura, Y. The angiosperm gibberellin–GID1–DELLA growth regulatory mechanism: how an ‘inhibitor of an inhibitor’ enables flexible response to fluctuating environments. Plant Cell 21, 1328–1339 (2009).

Jin, Y. et al. DELLA proteins are common components of symbiotic rhizobial and mycorrhizal signalling pathways. Nat. Commun. 7, 12433 (2016).

Fonouni-Farde, C. et al. DELLA-mediated gibberellin signalling regulates Nod factor signalling and rhizobial infection. Nat. Commun. 7, 12636 (2016).

Gutjahr, C. Phytohormone signaling in arbuscular mycorrhiza development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 20, 26–34 (2014).

Roppolo, D. et al. A novel protein family mediates Casparian strip formation in the endodermis. Nature 473, 380–383 (2011).

Dong, W. et al. An SHR–SCR module specifies legume cortical cell fate to enable nodulation. Nature 589, 586–590 (2021).

Gallagher, K. L., Paquette, A. J., Nakajima, K. & Benfey, P. N. Mechanisms regulating SHORT-ROOT intercellular movement. Curr. Biol. 14, 1847–1851 (2004).

Lucas, W. J., Ham, B. K. & Kim, J. Y. Plasmodesmata—bridging the gap between neighboring plant cells. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 495–503 (2009).

Dolan, L. et al. Cellular organisation of the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Development 119, 71–84 (1993).

Skawińska, M. et al. in The Model Legume Medicago truncatula (ed. de Bruijn, F. J.) 709–725 (Wiley, 2019).

Lévy, J. et al. A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science 303, 1361–1364 (2004).

Fonouni-Farde, C. et al. Gibberellins negatively regulate the development of Medicago truncatula root system. Sci. Rep. 9, 2335 (2019).

Hiratsu, K., Matsui, K., Koyama, T. & Ohme-Takagi, M. Dominant repression of target genes by chimeric repressors that include the EAR motif, a repression domain, in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 34, 733–739 (2003).

Shaar-Moshe, L. & Brady, S. M. SHORT-ROOT and SCARECROW homologs regulate patterning of diverse cell types within and between species. N. Phytol. 237, 1542–1549 (2023).

Choi, J. W. & Lim, J. Control of asymmetric cell divisions during root ground tissue maturation. Mol. Cells 39, 524–529 (2016).

Helariutta, Y. et al. The SHORT-ROOT gene controls radial patterning of the Arabidopsis root through radial signaling. Cell 101, 555–567 (2000).

Wu, S. et al. A plausible mechanism, based upon Short-Root movement, for regulating the number of cortex cell layers in roots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16184–16189 (2014).

Ortiz-Ramírez, C. et al. Ground tissue circuitry regulates organ complexity in maize and Setaria. Science 374, 1247–1252 (2021).

Paquette, A. J. & Benfey, P. N. Maturation of the ground tissue of the root is regulated by gibberellin and SCARECROW and requires SHORT-ROOT. Plant Physiol. 138, 636–640 (2005).

Bertolotti, G. et al. A PHABULOSA-controlled genetic pathway regulates ground tissue patterning in the Arabidopsis root. Curr. Biol. 31, 420–426 (2021).

Blanco-Touriñán, N., Serrano-Mislata, A. & Alabadí, D. Regulation of DELLA proteins by post-translational modifications. Plant Cell Physiol. 61, 1891–1901 (2020).

Yoshida, H. et al. DELLA protein functions as a transcriptional activator through the DNA binding of the indeterminate domain family proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7861–7866 (2014).

Fukazawa, J. et al. DELLAs function as coactivators of GAI-ASSOCIATED FACTOR1 in regulation of gibberellin homeostasis and signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 2920–2938 (2014).

Long, Y. et al. Arabidopsis BIRD Zinc Finger Proteins jointly stabilize tissue boundaries by confining the cell fate regulator SHORT-ROOT and contributing to fate specification. Plant Cell 27, 1185–1199 (2015).

Moreno-Risueno, M. A. et al. Transcriptional control of tissue formation throughout root development. Science 350, 426–430 (2015).

Pimprikar, P. et al. A CCaMK–CYCLOPS–DELLA complex activates transcription of RAM1 to regulate arbuscule branching. Curr. Biol. 26, 987–998 (2016).

Liu, Q. et al. Transcriptional landscape of rice roots at the single-cell resolution. Mol. Plant 14, 384–394 (2021).

Cervantes-Pérez, S. A. et al. Cell-specific pathways recruited for symbiotic nodulation in the Medicago truncatula legume. Mol. Plant 15, 1868–1888 (2022).

Frank, M. et al. Single-cell analysis identifies genes facilitating rhizobium infection in Lotus japonicus. Nat. Commun. 14, 7171 (2023).

Ubeda-Tomás, S. et al. Root growth in Arabidopsis requires gibberellin/DELLA signalling in the endodermis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 625–628 (2008).

Delaux, P. M. et al. Comparative phylogenomics uncovers the impact of symbiotic associations on host genome evolution. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004487 (2014).

Bravo, A. et al. Genes conserved for arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis identified through phylogenomics. Nat. Plants 2, 15208 (2016).

Pimprikar, P. & Gutjahr, C. Transcriptional regulation of arbuscular mycorrhiza development. Plant Cell Physiol. 4, 678–695 (2018).

Tadege, M. et al. Large-scale insertional mutagenesis using the Tnt1 retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 54, 335–347 (2008).

Limpens, E. et al. RNA interference in Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 983–992 (2004).

Zhou, W. et al. A jasmonate signaling network activates root stem cells and promotes regeneration. Cell 177, 942–956 (2019).

Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 (1998).

Javot, H. et al. Medicago truncatula mtpt4 mutants reveal a role for nitrogen in the regulation of arbuscule degeneration in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant J. 68, 954–965 (2011).

Limpens, E. et al. Medicago N2-fixing symbiosomes acquire the endocytic identity marker Rab7 but delay the acquisition of vacuolar identity. Plant Cell 21, 2811–2828 (2009).

An, J. et al. A Medicago truncatula SWEET transporter implicated in arbuscule maintenance during arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. N. Phytol. 224, 396–408 (2019).

Mcgonigle, G. T., Miller, M. H., Evans, D. G., Fairchild, G. L. & Swan, J. A. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. N. Phytol. 115, 495–501 (1990).

Trouvelot, A., Kough, J. & Gianinazzi-Pearson, V. in Physiological and Genetical Aspects of Mycorrhizae (eds Gianinazzi-Pearson, V. & Gianinazzi, S.) 217–221 (INRA, 1986).

Xiao, T. T. et al. Fate map of Medicago truncatula root nodules. Development 141, 3517–3528 (2014).

Musielak, T. J., Schenkel, L., Kolb, M., Henschen, A. & Bayer, M. A simple and versatile cell wall staining protocol to study plant reproduction. Plant Reprod. 28, 161–169 (2015).

Kurihara, D., Mizuta, Y., Sato, Y. & Higashiyama, T. ClearSee: a rapid optical clearing reagent for whole-plant fluorescence imaging. Development 142, 4168–4179 (2015).

Ursache, R., Andersen, T. G., Marhavy, P. & Geldner, N. A protocol for combining fluorescent proteins with histological stains for diverse cell wall components. Plant J. 93, 399–412 (2018).

Op den Camp, R. et al. LysM-type mycorrhizal receptor recruited for rhizobium symbiosis in nonlegume Parasponia. Science 331, 909–912 (2011).

Engler, C. et al. A Golden Gate modular cloning toolbox for plants. ACS Synth. Biol. 3, 839–843 (2014).

Engler, C., Gruetzner, R., Kandzia, R. & Marillonnet, S. Golden Gate shuffling: a one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS ONE 4, e5553 (2009).

Wang, P. et al. Medicago SPX1 and SPX3 regulate phosphate homeostasis, mycorrhizal colonization, and arbuscule degradation. Plant Cell 33, 3470–3486 (2021).

Pecrix, Y. et al. Whole-genome landscape of Medicago truncatula symbiotic genes. Nat. Plants 4, 1017–1025 (2018).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186 (2012).

Cenci, A. & Rouard, M. Evolutionary analyses of GRAS transcription factors in angiosperms. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 273 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. SHORT-ROOT paralogs mediate feedforward regulation of D-type cyclin to promote nodule formation in soybean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2108641119 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Geurts and R. Heidstra for critical reading of the paper. We also appreciate B. Scheres and I. Blilou for helpful discussion. We thank M. J. Harrison for providing della mutants. The original M. truncatula Tnt1 insertion lines used in this research project, which are jointly owned by the Centre National De La Recherche Scientifique, were obtained from Oklahoma State University (successor-in-interest from Noble Research Institute, LLC) and were created through research funded, in part, by grants from the National Science Foundation, NSF no. DBI-0703285 (J. Wen) and NSF no. IOS-1127155 (J. Wen). The AtCOR promoter was provided by W. Kohlen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A. and E.L. conceptualized the project. J.A., W.C., K.A. and E.L. developed the methodology. J.A., E.L., L.F., W.C., K.A., Y.W., G.L., M.Z., Q.C., J.H. and X.M. conducted the investigation. J.A. and E.L. visualized the results, acquired the funding and were responsible for project administration. E.L. supervised the project. J.A. and E.L. wrote the original draft of the paper. J.A., E.L. and T.B. reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Joop Vermeer and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 M. truncatula root meristem, arbuscule position in root cortical layers and the expression pattern of MtDELLA1.

a, Edu-staining of M. truncatula root tips. Green star indicates quiescent center cells. C3-C5, inner cortex in between red and yellow dotted lines; C1-C2 in between blue and yellow dotted lines. b, Representative view of transverse sectioned Medicago mycorrhized roots after four wpi (weeks inoculation) with Rhizophagus irregularis. ep, epidermis; c1-c5, cortical cell layers 1-5; en, endodermis; pc, pericycle. Arbuscules are indicated by an arrow. c, Transverse view of pMtDELLA1::NLS–3xGFP activity in endodermis and stele in the mature part of the root. The arrowhead indicates endodermis. d, e, Confocal images of pMtDELLA1:: NLS–3xGFP transformed M. truncatula roots grown for four weeks without inoculation. d, pMtDELLA1 activity in stele and endodermis above the root differentiation zone. e, pMtDELLA1 activity in the root meristem. f, g, Confocal images of pMtDELLA1::NLS–3xGFP transformed M. truncatula roots inoculated with R. irregularis for four weeks. f, pMtDELLA1::NLS–3xGFP activity in the stele of the mature root part. g, pMtDELLA1::NLS–3xGFP activity in entire root meristem. All scale bars, 50 μm. c–g, The experiments were repeated twice with similar results. Each result represents more than five independent biological lines.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The expression pattern of AtCASP1::NLS–3xGFP in the Medicago roots.

a, b, pAtCASP1::NLS–3xGFP activity in transformed M. truncatula ecotype Jemalong A17 root tips (a) and mature roots (b). c, d, pAtCASP1::CASP1:NLS–3xGFP activity in transformed M. truncatula ecotype Jemalong A17 root colonized with R. irregularis for four weeks. (c) root meristem. (d) mature root part. The arrowhead indicates arbuscule. e-f, pAtCASP1:: NLS–3xGFP activity in transformed M. truncatula ecotype R108 roots inoculation with (f) or without (e) R. irregularis for four weeks. g, h, pAtCASP1::NLS–3xGFP activity in transformed M. truncatula della1della2 mutant roots inoculation with (h) or without (g) R. irregularis for four weeks. All roots were Clearsee treated and stained with calcofluor white. All scale bars, 50 µm. a–h, The experiments were repeated more than twice with similar results. Each result represents more than five independent biological lines.

Extended Data Fig. 3 MtDELLA1 is mobile in Medicago and Arabidopsis roots.

a–f, Transgenic roots of Medicago. All scale bars, 50 µm. a-b, pAtSCR::GFP–GUS activity in the endodermis of transformed M. truncatula ecotype A17 root. (a) GFP channel. (b) Overlay of GFP channel and bright field channel. en, endodermis. c, Confocal image of pAtSCR:MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed M. truncatula ecotype A17 root. d, Confocal image of pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed M. truncatula della1della2 root inoculated with R. irregularis for four weeks. The arrowhead indicates arbuscule. e, f, Confocal image of pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed M. truncatula ecotype A17 root inoculated with rhizobium strain S. meliloti 2011 for three weeks. (e) GFP channel. (f) Overlay of GFP channel and bright field channel. Fluorescence from MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP was observed in multiple cortex layers. All the experiments were repeated more than twice with similar results. g-j, Transgenic roots of Arabidopsis. All scale bars, 25 µm. (g and i) pAtSCR::GFP-GUS activity in Arabidopsis mature root (g) and root tip (i) after 5 DAG (days after germination). (h and j) Expression of pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP in Arabidopsis mature root (h) and root tip (j). (h) Arabidopsis roots were counterstained with propidium iodide (PI). (g, i and j) Arabidopsis roots were treated with Clearsee solution for one week and cell walls stained with calcofluor white (purple). Each result represents eight independent transformation lines. Arrow indicate GFP signaling. ep, epidermis; co, cortex; en, endodermis.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The cortex expression promoter analysis and MtDELLA1 regulate Medicago cortex formation at root meristem zone.

a, Histochemical staining for pAtCOR::GUS transformed M. truncatula roots shows promoter activity in all cortex cell layers. Scale bars, 25 µm. n five independent transgeninc plants show the similar results. b, The outer cortex of pAtCOR::2NLS–MtDELLA1-∆18 transformed della1della2 root did not form arbuscules after six wpi. Arrowhead indicate arbuscules. Scale bars, 50 µm. n = four independent transgenic plants. c–f, Confocal microscopy image of Medicago WT or della1della2 transgenic root meristems. Roots colonized with R. irregularis for six weeks. Green dots indicate cortical cell layers. The arrowheads indicate epidermis. All scale bars, 50 µm. c, Empty vector transformed WT R108 root. d, pAtCOR::MtDELLA1 transformed della1della2 root. e, pAtCOR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed della1della2 root. f, pMtDELLA1::GFP–Mt–DELLA1-∆18 transformed wild type root. c-f, The experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 5 MtDELLA1-∆18 stabilization and induction of additional root cortex layers is impaired in the dmi3 mutant.

a-b, Representative cross section of Medicago WT and della1della2 mutant roots. Scale bars, 50 μm. c, Medicago WT R108 transformed with empty vector and della1della2 mutant transformed with empty vector or immobile 2NLS–MtDELLA1-∆18 6 wpi with R. irregluaris. n number of independent transgenic plants. The circles represent individual data from independent transgenic roots, circles of the same color represent roots from same transgenic plants. The bars and the error bars indicate mean values ± s.d. All data were analysed using ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The P value were calculated on the basis of means of independent transgenic plants. d, e, Representative image of pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed Medicago roots showing thick root phenotype without inoculation with AM fungi. d, Bright field image of pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed Medicago hairy roots. e, DsRed signal as marker for the pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transgenic roots. Arrowhead, indicates thick transgenic roots. *, indicate normal transgenic root. All scale bars, 500 μm. f, Western blot result of MtDELLA1-∆18 in pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed M. truncatula dmi3 roots inoculation or non-inoculation with R. irregualris for four weeks. Per replicate two independent transgenic roots were pooled. g, Representative longitudinal section of pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed Medicago dmi3 mutant root showing the short thick root phenotype without inoculation with AM fungi. Scale bar, 100 μm. a, b, d, e and g, All the experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 6 MtDELLA1-∆18 stimulates cortex formation upon rhizobium inoculation.

a–c, Cross section images of Medicago WT roots expressing empty vector (a) and pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP (b and c). d, Root of Medicago della1della2 mutant expressing pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP. (a, c, d) Roots three weeks after inoculation with transgenic S. meliloti 2011 (Sm2011–GFP). (b) Roots mock treated. C1 to C9, indicate the number of cortical layers 1 to 9. All scale bars, 50 µm. (a-d) for each construct/lines five to eight biological replicates were observed with similar results from two independent experiments. e, Quantification of cortical cell layers in (b) and (d). n, number of independent transgenic plants. The circles represent individual data collected from individual transgenic roots; circles of the same colour represent roots from the same transgenic plants. The bars and error bars are presented as mean values ± s.d. All data were analysed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. The P value was calculated based on means of independent transgenic plants.

Extended Data Fig. 7 RNA-seq data in MtDELLA2 and phenotype of root cortical cell layers in Mtdella1della2della3 roots.

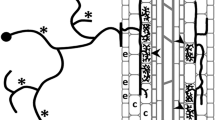

a, Medicago WT and Mtdella1della2 mycorrhized root RNA-seq data mapping of MtDELLA2 transcripts using CLCbio genomics workbench. Green and red color reads indicate reads members of a broken pair. Green indicates forward direction mapped; red color reads indicate reverse direction mapped. Tnt1 insertion position indicated by NF4302 on coding sequences of MtDELLA2. b, The FPKM values of MtDELLA2 in Medicago WT and Mtdella1della2 mycorrhized roots at 9 days after inoculation with Rhizophagus irregularis (n= biological replicates). The bars and error bars indicate mean values ± s.e.m. All data were analysed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. c, Quantification of cortex layers in Mtdella1della2della3 roots. #1 and #2 represent independent experiments. The roots were counted 13 DAG (days after germination). n the number of independent mutant plants. Each circle represents individual data collecting from independent plants. Error bars are presented as mean values ± SD. All data were analysed using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test compared to the WT control. d-g, Longitudinal and transverse view of Medicago WT and Mtdella1della2della3 mutant roots. ep, epidermis; c, cortical cell layers; en, endodermis. pc, pericycle. (d and e) Medicago wild type. (f and g) Mtdella1della2della3. All scale bars, 50 µm. c-g, The experiments were repeated twice.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Loss of Medicago SCR does not affect mycorrhization.

a, Diagram of MtSCR gene structure and Mtscr1-1 Tnt1 insertion position. b, Quantification of mycorrhization level in M. truncatula WT or scr1-1 roots four wpi with R. irregularis according to ref. 50. F%, frequency of analyzed root fragments that are mycorrhized; M%, intensity of infection in the whole roots; m%, intensity of infection in mycorrhized root fragments; A%, arbuscule abundance in entire root fragments; a%, arbuscule abundance in mycorrhized root fragments. n 3 biological repeats. Each circles represent data from independent transgenic plants. The bars and error bars indicate mean values ± s.e.m. All data were analysed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. c, d, Confocal images showing cortex layers and arbuscules in Medicago WT R108 or Mtscr1-1 transformed roots, six wpi with R. irregularis. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results. (c) Empty vector transformed wild type roots as positive control. (d) pAtSCR::MtDELLA1-∆18–GFP transformed Mtscr1-1 root. Roots six wpi with R. irregularis. ep, epidermis; C1-C9, cortical cell layers; en, endodermis; pc, pericycle. All scale bars, 50 µm. The root cell walls were visualized by SCRI Renaissance 2200 staining and fungal structures with WGA-Alexa Fluor 488. The arrows indicate arbuscules. N > 3 independent biological transgenic lines.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Phylogenetic tree of Medicago SHR genes and Tnt insertion position of shr mutants.

a, Phylogenetic tree of the Medicago SHR gene family. Medicago SHR gene sequences were obtained from M. truncatula genome v4.0 and v5.0 using blastp of A. thaliana (At) SHR protein sequence. MtSHR1, MtrunA17_Chr5g0401131; MtSHR2, MtrunA17_Chr4g0054071; MtSHR3, MtrunA17_Chr2g0329591. Oryza sativa (Os), Glycine max (Gm) and Solanaceae lycopersicum (Sl) SHR were retrieved from Phytozome v13 (ref. 64,65). The other GRAS family gene members obtained in according to ref. 65. Soybean SHRs were obtained with ref. 66. Neighbor-joining method was used with 2000 bootstraps. b, MtSHR1, MtSHR2 and MtSHR3 gene structure and Tnt1 insertion position of respective mutants.

Extended Data Fig. 10 MtDELLA converges with SHR to control root cortex number.

a, Overexpression of SHR1 (pLjUBQ::MtSHR1) triggers additional cortical cell layers with AM susceptibility for hosting arbuscules. Roots at three wpi with R. irregularis. ep, epidermis; C1-C11, cortical cell layers 1-11; en, endodermis. b, Confocal images of ground tissue layers in Medicago WT R108 and shr1shr3 mutant roots at four DAG. ep, epidermis; C1-C5, cortical cell layers 1-5; en, endodermis; pc, pericycle. c, Quantification of cortical cell layers in (b). No significance difference was observed. d, Quantification of cortical cell layers in shr single mutants. e, Quantification of root cortical cell layers in Medicago WT R108 with or without inoculation with R. irregularis for four weeks. P-value, Mtshr1 vs. Mtshr2 = 0.5045; Mtshr1 vs. Mtshr2 = 0.9721; Mtshr1 vs. Mtshr2 = 0.5763. f-j, MtDELLA1 also converges with SHR to control cortex number upon rhizobium inoculation for three weeks. f-i, Confocal images of indicated transgenic medicago wild type and Mtshr1shr3 roots inoculated or not inoculated with rhizobium Sm2011 for three weeks. g, the number of ground tissue layers including cortical cell layers and endodermis; pc, pericycle. (f) pAtCASP1::GFP–MtDELLA1-∆18 transformed wild type roots without inoculation. (g) pAtCASP1::GFP–MtDELLA1-∆18 transformed wild type roots inoculated with Sm2011. (h) pLjUBQ::SHR2–SRDX pAtCASP1::GFP-MtDELLA1–∆18 transformed Mtshr1shr3 without inoculation. (i) pLjUBQ::MtSHR2–SRDX pAtCASP::GFP–MtDELLA1-∆18 transformed Mtshr1shr3 inoculated with Sm2011. j, Quantification of the number of ground tissue (cortex and endodermis) layers in indicated transgenic lines. (c), (d), (e) and (j) The circles represent data from independent transgenic roots, circles of the same color represent roots from same transgenic plants. The bars and error bars indicate mean values ± s.d. n, number of independent plants. All data were analysed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests (e) or ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (d, j). The P value were calculated on the basis of means of independent plants. All scale bars, 50 µm.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots and statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots and statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 10

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

An, J., Fang, L., Cremers, W. et al. A mobile DELLA controls Medicago truncatula root cortex patterning to host arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nat. Plants 11, 2156–2167 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02114-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02114-6