Abstract

Rare coding variants shape inter-individual differences in human phenotypes1. However, the contribution of rare non-coding variants to those differences remains poorly characterized. Here we analyse whole-genome sequence (WGS) data from 347,630 individuals with European ancestry in the UK Biobank2,3 to quantify the relative contribution of 40 million single-nucleotide and short indel variants (with a minor allele frequency (MAF) larger than 0.01%) to the heritability of 34 complex traits and diseases. On average across phenotypes, we find that WGS captures approximately 88% of the pedigree-based narrow sense heritability: that is, 20% from rare variants (MAF < 1%) and 68% from common variants (MAF ≥ 1%). We show that coding and non-coding genetic variants account for 21% and 79% of the rare-variant WGS-based heritability, respectively. We identified 15 traits with no significant difference between WGS-based and pedigree-based heritability estimates, suggesting their heritability is fully accounted for by WGS data. Finally, we performed genome-wide association analyses of all 34 phenotypes and, overall, identified 11,243 common-variant associations and 886 rare-variant associations. Altogether, our study provides high-precision estimates of rare-variant heritability, explains the heritability of many phenotypes and demonstrates for lipid traits that more than 25% of rare-variant heritability can be mapped to specific loci using fewer than 500,000 fully sequenced genomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Most human traits are heritable and influenced by thousands of DNA variants. Whereas the nature and effect size of most causal genetic variants remain largely unknown, previous studies have nonetheless quantified, using a variety of methods, an overall contribution to trait heritability from observable genetic variation4,5,6,7,8. For example, one study9 showed, on average across 1,000 traits, that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are common in European ancestry populations explain approximately 9% of phenotypic variance, with trait-specific estimates ranging from 5% to 49%.

The overall proportion of phenotypic variance explained by additive genetic effects of SNPs, also known as SNP-based heritability \(({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2})\), is a critical parameter that determines the statistical power of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and provides an upper bound for the performance of trait prediction from genomic data. So far, although GWAS have identified thousands of SNPs associated with many traits and diseases, the amount of phenotypic variance explained by GWAS-detected associations \(({h}_{{\rm{GWAS}}}^{2})\) remains, for most traits, substantially lower than \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\). The gap between \({h}_{{\rm{GWAS}}}^{2}\) and \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\) was previously referred to as ‘hiding heritability’10 and is expected to vanish as GWAS sample sizes increase4. Consistent with this prediction, a recent GWAS of human height including more than 5 million individuals has now demonstrated convergence between \({h}_{{\rm{GWAS}}}^{2}\) and \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\) (ref. 11). Estimates of \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\) have long been restricted to common SNPs (typically, with a minor allele frequency (MAF) larger than 1% or 5%) because of relatively small experimental sample sizes available and a lack of reliable, cost-effective and scalable technologies to measure rarer genetic variation. Consequently, these estimates are systematically lower than traditional estimates of narrow sense heritability (that is, heritability due to additive genetic effects) from pedigree-based studies \(({h}_{{\rm{PED}}}^{2})\) (ref. 12). Various factors have been proposed to explain the gap between \({h}_{{\rm{PED}}}^{2}\) and \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\) (based on common variants) also known as ‘still-missing heritability’10. Those factors include genetic variation not well tagged by common SNPs (including rare variants and structural variants), shared environmental effects between close relatives and non-additive genetic effects (for example, interactions between genetic variants or between genetic variants and shared environment between relatives), which may have inflated estimates of additive genetic variation from pedigree-based studies. Overall, quantifying the contribution of these different factors is crucial for designing optimal experiments to identify causal genetic variation for complex traits and disease.

Since 2022, a series of studies using data from the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) programme have generated whole-genome sequence (WGS)-based estimates of \({h}_{{\rm{SNP}}}^{2}\) (hereafter denoted \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\)) for height and body mass index (BMI)13 as well as for smoking-related traits14, type 2 diabetes15 and coronary artery disease16. Despite WGS enabling better measurement of rare genetic variation compared with reference-based imputation, the previous WGS-based studies were still limited by their sample sizes (N of about 25,000) such that reported estimates of \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) had standard errors as large as 10%. This limitation has made it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the recovery of the still-missing heritability from WGS data. More recently, whole-exome sequence (WES) data of more than 300,000 participants in the UK Biobank (UKB) have been used to obtain more precise estimates of the role of rare coding variants1 (comprising less than 3% of the genome), but a substantial gap remains for rare non-coding variants.

In this study, we address these previous limitations using WGS data from 347,630 unrelated individuals with European ancestry in the UKB3 to accurately quantify the contribution of coding and non-coding SNPs (MAF > 0.01%) to the heritability of 34 complex traits and diseases. On average across traits, we show that coding and non-coding WGS variants account for 17% and 83% of estimated \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) (21% versus 79% for the rare-variant component of \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\)), respectively; and that WGS variants overall account for approximately 88% of pedigree-based heritability estimated from 171,446 pairs of relatives. We complemented these analyses by conducting GWAS of all phenotypes in a larger sample of 452,618 individuals with European ancestry (347,630 unrelated individuals plus all their relatives in the UKB) and identify 886 associations across traits involving rare variants (0.01% < MAF < 1%). For lipid-related quantitative traits these rare-variant associations (RVAs) explain more than one-quarter of their overall rare-variant heritability. Our GWAS results indicate that a substantial amount of the still-missing heritability of complex traits is already mappable using the GWAS experimental design applied to WGS data of fewer than 500,000 individuals.

Overview of study design

We analysed 490,542 genomes included in the second tranche of WGS data released by the UKB in December 20233. We focused our main analyses on 40,575,204 autosomal sequence variants (including bi-allelic and multi-allelic SNPs and indels) with a MAF > 0.01% (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) in a genetically homogeneous sample of 347,630 conventionally unrelated individuals (that is, with a genomic relationship coefficient lower than 0.05) sampled from a larger subgroup of 452,618 UKB participants with European ancestry (Methods). We selected 41 complex phenotypes spanning a wide range of human traits and common diseases (Supplementary Table 3) and showing a marginally significant estimate of \({h}_{{\rm{PED}}}^{2}\) from 171,446 pairs of relatives in the UKB. We then estimated \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) for these 41 traits using the GREML-LDMS method17 implemented in MPH v.0.53.2 (ref. 18). Heritability estimates for all 41 phenotypes are reported in Supplementary Table 4.

In subsequent sections of the paper, we focus on 34 phenotypes with both a significant \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) (two-sided Wald test P < 0.05/41 ≈ 0.001) and a marginally significant rare-variant heritability estimate (P < 0.05). We report in the main text estimates of \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) \(({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2})\) from our most conservative correction for population stratification (Methods). Sensitivity analyses of the effect on \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) of varying the number of principal components and birthplace clusters fitted as fixed effects are reported in Extended Data Fig. 1. These sensitivity analyses notably show that heritability estimates are robust to covariate-adjustment for most traits. However, uncorrected estimates of \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) for educational attainment and fluid intelligence score were significantly inflated by fine-scale geographical structures in the United Kingdom that were not fully captured by genotypic principal components. This underscores the importance of using geographical information to inform and correct biases affecting heritability estimates19,20, especially for behavioural traits involved in migration patterns21,22.

Estimates of heritability from WGS data

Across 34 selected phenotypes, \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) ranged between 0.075 (standard error (s.e.) 0.010) for the number of children and 0.709 (s.e. 0.006) for height, with an average of 0.284 (s.e. 0.002) (Fig. 1a and Table 1). Our estimates for height, BMI (0.339 (s.e. 0.009)) and smoking status (0.174, s.e. 0.015) were all consistent with previous studies based on WGS data from the TOPMed consortium13,14 (Table 2). We also compared our GREML estimates of \({h}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) with those obtained using Haseman–Elston (HE) regression23. We found highly concordant results across both approaches, except for height (HE 0.862, s.e. 0.01) and educational attainment, measured as the number of years of schooling completed (HE 0.464, s.e. 0.011; GREML 0.347, s.e. 0.009) (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 5). These discrepancies are expected because assortative mating on both traits24 is known to differentially affect estimates from these two methods25. In fact, assortative mating-adjusted HE-regression estimates (Methods) for height and educational attainment were 0.702 (s.e. 0.008) and 0.353 (s.e. 0.007), respectively (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 6), which is more consistent with GREML estimates.

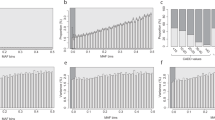

a, Estimates of heritability from WGS data (denoted \({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) on the x axis) for 34 phenotypes with a marginally significant rare-variant heritability. Results for a larger set of phenotypes are available in Supplementary Table 4. Heritability estimates for binary traits are reported on the liability scale (Methods). All estimates were adjusted for covariates described in the Methods section. b, Comparison between the common-variant component (x axis) and the rare-variant component of \({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) (y axis). c, Comparison between WGS-based (x axis) and pedigree-based (y axis; \({h}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\)) estimates of heritability. Pedigree-based estimates for height (HT), educational attainment (EA) and fluid intelligence score (FI) were adjusted for assortative mating as described in Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 6. In a–c, error bars represent s.e.s. Correlation between heritability estimates reported in b and c were calculated using a Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) over n = 34 traits. The P value measuring the significance of these correlations is denoted as P in the corresponding panel and is based on a two-sided Pearson’s correlation test. d, Partitioning of pedigree-based narrow sense heritability into common-variant, rare-variant and missing components. The x axis represents the ratio \({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}/{h}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\). Phenotype names with an asterisk * indicate cases where \({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2} > {h}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\). The dotted vertical line indicates 88%, that is the mean ratio of \({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) to \({h}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) across 34 phenotypes.

Overall, we observed a significant, yet moderate, correlation between the rare-variant and common-variant components of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) (Pearson’s correlation R = 0.55, two-sided test P = 8.5 × 10−4; Fig. 1b). The average rare-variant heritability across traits was 0.063 (s.e. 0.002), which represents about 22% of the mean \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) across traits. Educational attainment showed the largest contribution of rare variants to its estimated heritability with approximately 43% of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) accounted for by rare variants. By contrast, SNPs with 0.01% < MAF < 1% contributed less than 12% of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) for bone mineral density and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Finally, we also quantified genetic correlations between phenotypes and found highly concordant estimates from common and rare variants (Supplementary Note 1, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7).

Comparison with pedigree-based estimates

Next, we compared \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) with pedigree-based estimates of narrow sense heritability \(({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2})\) from 171,446 pairs of relatives in the UKB (Fig. 1c). Pairs of individuals were labelled as relatives when their genomic relationship coefficient (estimated as an allelic correlation; Methods) exceeded 0.05. Comparison with pedigree-based heritability estimates obtained from the same cohort minimizes systematic differences due to phenotype definition and measurement error. We estimated pedigree-based heritability using statistical models accounting for non-additive genetic effects and assortative mating (Methods and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) but also report estimates based on a model assuming that all resemblance between relatives is due to additive genetic effects (Supplementary Table 8).

Overall, we found no significant difference between \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) and \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) (two-sided Wald test P > 0.05) for 25 phenotypes, including 15 quantitative traits with s.e. of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) lower than 3%, suggesting their pedigree-based narrow sense heritability is largely explained by WGS data (Table 1). Furthermore, we defined the explained heritability ratio (EHR) as the ratio of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) to \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\). EHR is expected to vary between 0 and 1 such that large values indicate a substantial amount of pedigree-based heritability is accounted for by observed WGS variants. Across phenotypes, EHR varied between 0.34 (s.e. 0.04) for telomere length and 1.29 (s.e. 0.26) for alanine aminotransferase levels, with an average of 0.88 (median is 0.87), suggesting that additive genetic effects at WGS variants explain most of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) for these traits (Fig. 1d).

In summary, we report significant estimates of rare-variant heritability for 34 phenotypes with high precision (s.e. between 0.6% and 2.7% for quantitative traits and 1.5% to 3.0% for binary traits), we highlight at least 15 traits whose narrow sense heritability appears to be fully explained by WGS data, and show that WGS data, on average, captures approximately 88% of the pedigree-based narrow sense heritability, with differences across traits probably explained by statistical power and genetic architecture.

Heritability enrichment at coding loci

We partitioned \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) to assess the relative contribution of coding and non-coding variants (Methods and Supplementary Table 9). Consistent with previous studies, we found a significant enrichment of heritability in coding variants (that is, 0.71% of all 40 million in our primary analyses; Supplementary Table 2), which contributed 17.5% of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) on average across traits (Fig. 2a). Stratified by allele frequency, coding variants accounted for 21.0% of rare-variant heritability and 16.9% of common-variant heritability (Fig. 2a). However, relative to the proportion of coding variants included in our primarily analyses this implies a 36-fold and 26-fold heritability enrichment for common and rare variants, respectively (Supplementary Table 10). Heritability enrichment in coding variants was significantly correlated (across traits) between common-variant and rare-variant heritability (Pearson’s correlation R = 0.56; two-sided test P = 5.6 × 10−4; Fig. 2b). Yet, such a moderate correlation implies that differences in heritability enrichment between common and rare variants can be expected across traits. For example, heritability enrichment in coding variants for type 2 diabetes was only significant for common variants (21-fold, s.e. 2.3) but not for rare variants (tenfold, s.e. 6.0). Overall, we identified three phenotypes (including two common diseases) showing a significant greater-than-sixfold heritability enrichment (two-sided Wald test P < 10−6; Supplementary Table 10) in coding variants, which was only detected with common variants but not with rare variants (two-sided Wald test: P > 0.05). Whereas the latter set of observations could be explained by a lack of statistical power to detect heritability enrichment with rare variants (and with disease), it is also consistent with coding deleterious variants being kept at much lower frequencies than the ones spanned by our primary analyses and thus contributing less to trait heritability for variants with MAF > 0.01%. To further characterize heritability enrichment for trait-altering variants, we discuss in Supplementary Note 2 further analyses of heritability enrichment in regulatory variants in close vicinity of genes and in genomic regions that are conserved across species (Supplementary Table 10 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

a, This panel represents, across 34 phenotypes, the ratio of proportion of phenotypic variance explained by coding variants \(({h}_{{\rm{c}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{d}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{g}}}^{2})\) over that explained by all WGS variants \(({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2})\). The contribution to \({h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) from coding and non-coding variants were estimated jointly (Methods). The blue (and dashed) vertical line represents the mean of \({h}_{{\rm{C}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{d}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{g}}}^{2}/{h}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) across phenotypes. \({h}_{{\rm{C}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{d}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{g}}}^{2}\) was further partitioned into jointly estimated contributions from rare and common coding variants. The purple vertical line represents the mean across phenotypes of the ratio of phenotypic variance explained by common coding variants over that explained by all common variants. The green vertical line represents the mean across phenotypes of the ratio of phenotypic variance explained by rare coding variants over that explained by all rare variants. b, This panel compares heritability enrichment in coding variants between common variants (x axis) and rare variants (y axis). Error bars represent s.e.s. The correlation between heritability enrichment for common and rare variants was calculated using a Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) over n = 34 traits. The P value measuring the significance of that correlation is denoted as P in the bottom-right corner of the panel and is based on a two-sided Pearson’s correlation test.

In summary, our results confirm that coding variants disproportionally contribute to trait heritability and show that heritability enrichment in coding variants is relatively smaller for rare variants compared with common variants and that it varies across traits.

Overview of GWAS analyses

We performed GWAS analyses of all 34 phenotypes with the primary goal to assess how much of their rare-variant heritability can already be mapped to single loci using WGS data from 452,618 genomes. More comprehensive and trait-focused GWAS analyses using WGS data in the UKB have been conducted in previous studies26,27,28,29. Across traits, we detected 12,129 independent associations (two-sided Wald test P < 5 × 10−9), including 11,243 common-variant associations (CVAs) and 886 RVAs (Supplementary Table 11). The 12,129 independent associations involved 10,924 unique variants (10,164 unique common variants and 760 unique rare variants; Extended Data Fig. 4). RVAs were only detected for 30 traits (Supplementary Table 12) and 64% of them had a MAF > 0.1%, reflecting that power to detect associations with rarer variants remains limited. Among all genome-wide significant variants, 848 (that is, about 8%) were associated with at least 2 traits (Supplementary Table 13). The most pleiotropic CVA was the SLC39A8 missense variant rs13107325 (MAF = 7.5%), associated with 14 different traits, whereas a rare indel (rs754165241) within the fourth intron of ASGR1 (MAF = 0.8%) was associated with up to 9 different traits (Supplementary Table 13).

After winner’s curse correction30,31, we found each RVA to explain on average 0.027% of phenotypic variance compared with 0.023% for CVAs. On average across traits, the cumulative proportion of phenotypic variance explained by CVAs and RVAs represents 31% (range across traits 1.9–56%) and 11% (range across traits 0.2–50%) of the average common-variant and rare-variant heritability, respectively (Fig. 3a,b). Interestingly, 18% of all RVAs involved at least one lipid-related trait (dyslipidaemia n = 11; triglycerides levels n = 35; LDL n = 41 and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol n = 72, Supplementary Table 12), which only represent 12% of the 34 traits analysed. This 1.5-fold enrichment (that is, 18%/12%) suggests that rare variants associated with lipids tend to have larger effect sizes than those associated with other traits. Consistently, RVAs for HDL and LDL altogether account for more than one-third of their estimated rare-variant heritability (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 14). We replicated this last result in an independent sample of approximately 67,000 unrelated individuals with European ancestry in the Alliance for Genomic Discovery (AGD) cohort (Methods and Supplementary Note 3). We found that RVAs for LDL (40 out of 41 passed quality control in AGD) and HDL identified in the UKB altogether explain 0.9% of LDL variance and 1.8% of HDL variance, respectively. This represents approximately 34% and 29%, respectively, of LDL and HDL rare-variant heritability (Supplementary Table 15). Alkaline phosphatase (ALK) was the only non-lipid trait with more than one-third of its estimated rare-variant heritability already accounted for by 61 RVAs (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 12). These 61 ALK-associated RVAs cumulatively explained 3% of ALK variance in the AGD European ancestry sample, equivalent to 26% of rare-variant heritability estimated in the UKB. Two ALK-associated RVAs (rs79257782 and rs73728135) had frequencies larger than 3% in individuals with African ancestry in AGD (N = 15,690) and showed significant association with ALK (two-sided Wald test P < 5 × 10−8) with effect sizes highly consistent with those observed in individuals with European ancestry from both UKB and AGD (Supplementary Table 16). SNP effects for LDL-associated, HDL-associated and ALK-associated RVAs in participants with European and African ancestry from AGD are reported in Supplementary Table 16.

a, Proportion of WGS-based heritability explained by trait-associated variants. Left bars compare the variance explained by RVAs relative to the estimated heritability attributable to rare variants. Right bars compare the variance explained by CVAs relative to the estimated heritability attributable to common variants. Vertical dashed lines represent average proportions across phenotypes. b, Distribution of variance explained by RVAs as a function of the distance to nearest common variant. The P value shown at the top-left corner of the panel is based on a two-sided F-test with 2 and 879 degrees of freedom. Here, n denotes the number of RVAs in the corresponding annotation. A few RVAs were further annotated with the corresponding trait and the closest gene. The boxplots shown here represent the first quartile, the median and the third quartile of the corresponding distribution. c, Average of density of CVA within an increasing window size (x axis) around each RVA. Error bars represent s.e.s.

We found that 362 of 886 = 41% of RVAs were located within genomic loci covered by WES technologies (of these, 353 were coding and 9 non-coding), which represents a 41-fold enrichment relative to the proportion of WGS variants within those loci. However, and consistent with previous studies2, RVAs explaining large amounts of phenotypic variance were also detected outside WES-covered loci. That notably includes rs754165241 (mentioned above as the most pleiotropic RVA), in which a short deletion (allele frequency 0.8%) was associated with a 1.43 (s.e. 0.01) standard deviation (s.d.) increase in ALK levels, thus explaining around 3% of the phenotypic variance. This was the largest amount of variance explained observed across all associations. Note that rs754165241 was previously associated with ALK and lipids levels in the Trøndelag Health (HUNT) Study32, in a recent study27 and replicates in our AGD analyses (Supplementary Table 16).

Summary statistics for all 12,129 independent associations are available in Supplementary Table 11. We also present and discuss further analyses in Supplementary Note 4 quantifying the gain of WGS over imputation for detecting and fine-mapping trait-associated loci. We notably quantify the improvement in fine-mapping resolution from using WGS instead of imputed SNPs, while highlighting that existing imputation panels may still be missing common haplotypes in European ancestry populations (Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6, Supplementary Tables 17–19 and Supplementary Data).

Genomic distribution of RVAs

Next, we sought to characterize the genomic distribution of RVAs by quantifying, post hoc, how much genomic annotations contribute to differences in per-SNP variance explained at trait-associated loci. We focused on four genomic annotations with previous evidence of heritability enrichment across many complex traits33. These four annotations are: (1) distance between each RVA and their closest CVA (hereafter denoted DCCVA, distance to closest common variant association) for the same trait, (2) broadly defined coding regions including all variants captured by WES, (3) conserved regions across mammals defined using the Zoonomia phylogenetic score34 and (4) variant functional roles on canonical transcripts as described by Sequence Ontology35.

Among those four annotations, DCCVA was the only one significantly (P < 0.05) predictive of per-SNP variance explained (R2 = 0.007; two-sided F-test with 2 and 879 degrees of freedom P = 1.85 × 10−2; Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 5) whereas other annotations (such as PrimateAI3D36; Supplementary Fig. 6) were also predictive of the magnitude of effect sizes (Extended Data Fig. 7 and Methods). Therefore, we focus below on DCCVA and further characterize colocalization patterns between RVAs and CVAs across 19 phenotypes, each with at least 10 RVAs detected.

We observed a significant enrichment of RVAs near CVAs, with a median DCCVA of 27 kilobases (kb) across all trait–RVA pairs (Supplementary Fig. 7). The strongest and weakest colocalizations were observed for ALK (median DCCVA across 61 RVAs 5 kb) and C-reactive protein levels (median DCCVA across 27 RVAs 1.7 megabases (Mb)), respectively. For each trait, the significance of RVA–CVA colocalization was assessed relative to random subsets of SNPs matched on size (that is, the same number of SNPs as the trait-specific number of associations), MAF and linkage disequilibrium (LD) score distributions (Supplementary Fig. 7). We also assessed RVA–CVA colocalization by quantifying the density, within a specified genomic window on both sides, of CVAs around each RVA11. On average across traits, we found a mean density of 1.8 CVAs within 100 kb of each RVA (Fig. 3c).

Finally, we found that genomic loci with high density of CVAs also tend to have a high density of RVAs (Extended Data Fig. 8). Previous studies have shown that high density of associations is partly explained by imperfect tagging of underlying structural variants11. Therefore, we sought to quantify the relationship between RVA and CVA density and the presence of structural variants associated with the same trait (Methods). Overall, we found that loci where RVAs share their locations with at least 2 other RVAs (within 100 kb) are also associated with a 1.8-fold increase in the probability of colocalization with a structural variant associated with the same trait (Supplementary Fig. 8). By contrast, 100-kb-density of CVAs larger than 2 increases the probability of colocalization between CVAs and structural variants by 1.4-fold (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Collectively, these results indicate that CVAs and RVAs colocalize (nearby genes; Supplementary Fig. 9) and that RVAs detected closer to CVAs tend to explain more phenotypic variance (and thus heritability) than those located further away.

Discussion

In this study, we report precise estimates of rare-variant heritability for 34 complex phenotypes, including 23 quantitative traits for which standard errors of heritability estimates were lower than 1%. We show, on average across traits, that heritability attributable to additive genetic effects at WGS variants is approximately 88% of that estimated from relatives in the UKB. We highlight at least 15 quantitative traits with no significant difference between WGS-based and pedigree-based estimates, suggesting their heritability may no longer be missing. Although more precise pedigree-based estimates from future studies may still reveal statistical differences from WGS-based estimates for those 15 traits, our results demonstrate that any such differences are likely to be small.

Our results also reveal substantial still-missing heritability for number of children and telomere length with less than half of their pedigree-based heritability accounted for by sequenced variants with MAF > 0.01%. The average still-missing heritability observed across traits, which we estimated to be approximately 12% of \({h}_{{\rm{PED}}}^{2}\), can be explained by several sources. For example, ultra-rare variants (MAF < 0.01%) not included in our primary analyses, long structural variants not well tagged by SNPs sequenced using short-read WGS technologies, gaps in the current hg38 genome build accounting for about 8% of the genome37,38, (and thus potentially about 8% of \({h}_{{\rm{PED}}}^{2}\)) but also non-additive genetic effects (for example, interactions between variants or correlations between genes and the environment), which might have inflated pedigree-based estimates despite our attempts to model them (Methods). How much these different sources contribute to the residual still-missing heritability of specific traits remains an open question that future research will illuminate. Nevertheless, we describe below extra analyses that can inform the contributions of these factors.

Across traits, patterns of heritability enrichment in coding regions were correlated between common and rare variants. However, this correlation was moderate (Pearson’s correlation R = 0.56; s.e. 0.12), suggesting that significant differences in functional enrichment between common-variant and rare-variant heritability exist for specific traits (for example, vitamin D). We also observed differences in functional enrichment between common-variant heritability and rare-variant heritability for other annotations (Supplementary Note 2, Supplementary Table 10 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). In addition, we found that coding variants explain a larger fraction of heritability for rare variants (that is, approximately 21%) compared with common variants (that is, about 17%). However, relative to the size of the genome covered by these annotations, our findings imply a larger heritability enrichment in coding regions for variants with MAF > 1% (that is, 36-fold) compared with variants with MAF < 1% (that is, 26-fold). These results further indicate that GWAS-derived analyses (for example, polygenic scores methods integrating information from functional annotations39,40,41) assuming similar enrichment in functional annotations irrespective of MAF may be suboptimal, and that modelling potential interactions between functional annotations and MAF might help address this limitation.

Our GWAS analyses show that a substantial amount of the rare-variant heritability of lipid-related traits can already be mapped to specific loci. In particular, we found that 41 rare variants associated with LDL (Supplementary Table 12) together account for 1% of phenotypic variance, which is more than a third of its estimated rare-variant heritability (Fig. 3). However, for many traits, it appears that much larger sample sizes are required to explain the same fraction of rare-variant heritability. Moreover, consistent with previous studies, we found a strong colocalization between RVAs and CVAs. For example, 97% of RVAs detected for height were located within 100 kb of previously identified height-associated loci (Extended Data Fig. 9). Extended Data Fig. 9 also shows a lower enrichment of height heritability within GWAS-associated loci for variants with MAF between 0.001% and 0.1%, suggesting that future WGS-based GWAS of height may still identify novel loci, although the proportion of variance explained by yet-to-be-discovered associations will be vanishingly smaller. Overall, the genomic colocalization of rare-variant heritability and common-variant heritability can be utilized to improve GWAS discovery for rare (and ultra-rare) non-coding variants, for example, by aggregating pathogenic variants within loci containing CVAs in burden test analyses42.

Our study also allowed to empirically assess the limits of statistical methodologies such as LD score regression5, which have previously been used to estimate the heritability of complex traits using GWAS summary statistics. We found that LD score regression estimates were still well-calibrated for variants with a MAF > 0.1% but were substantially biased when SNPs with MAF < 0.1% were included (Supplementary Fig. 10). Recently, the Burden Heritability Regression methodology was proposed to estimate the contribution of rare coding variants to the heritability of complex traits1. This method uses summary statistics from gene-specific burden tests and thus could not straightforwardly be extended to analyse non-coding variants in WGS data. Overall, future research is needed to improve the reliability of methods using GWAS summary statistics to estimate rare-variant heritability and our study could serve as a benchmark to develop those approaches.

Our study has several limitations. First, our analyses were restricted to individuals with European ancestries because of the limited sample sizes of other ancestry groups in the UKB (N < 12,000), especially for studying rare variants. To date, there is a crucial need for heritability studies in other ancestry groups to better benchmark the accuracy of polygenic predictors of complex traits (including risk of disease) and refine understanding of their genetic architectures. Recent studies focusing on common variants have shown consistent heritability estimates between ancestry groups43. However, future large scale and multi-ancestries studies using WGS data and family-based designs are still needed to bridge the gap.

Second, our primary analyses focused on variants with a MAF larger than 0.01% to ensure comparability with estimates previously reported in the literature and, most importantly, to improve the precision of our estimates. Nevertheless, we also performed secondary analyses including ultra-rare variants (Methods, Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 20) and found, on average across traits, that including those yielded a ±6% variation around \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) obtained from SNPs with MAF > 0.01%. The most notable change was observed for number of children for which \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{WGS}}}^{2}\) increased from 0.074 up to 0.126 (that is, a 1.7-fold increase; Supplementary Fig. 11), which is no longer statistically different from its pedigree-based estimate (\({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}=0.151\), s.e. 0.028; two-sided Wald test P > 0.05). Overall, the relatively small contribution of ultra-rare variants for most traits aligns with the fact that EHR was uncorrelated with statistics measuring the strength of natural selection, which otherwise would have predicted a larger contribution from this class of variants (Supplementary Note 5, Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 21). However, these secondary analyses should be taken with caution as biases affecting SNP-based heritability estimates from ultra-rare variants are not fully understood and further research is needed before we can reliably apply statistical methods such as GREML in this context. For example, we observed significantly negative estimates of heritability for many traits (Supplementary Fig. 11b and Supplementary Table 20), which classically indicates model misspecification44.

Third, estimates of the rare-variant heritability for most common diseases analysed in this study were not significantly different from zero, reflecting a lack of precision of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) for diseases obtained using population-based (that is, not ascertained for a specific condition) biobank data. Consequently, our quantification of the average contribution of rare variants to trait heritability might be inflated because it was obtained from phenotypes with marginally significant rare-variant heritability estimates. Future studies may improve on these results by using case–control designs, larger experimental sample sizes and larger sets of traits.

Fourth, our study focused on autosomal variants, such that the contribution of sex chromosomes remains unclear. However, previous studies have shown that common X-chromosome variants contribute, on average across 20 complex traits, less than 3% of the SNP-based heritability estimated from autosomes45. Therefore, assuming the relative contribution of rare variants to \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) is similar between the X chromosome and the autosomes, we could extrapolate that accounting for X-chromosome variants would only inflate \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) by up to 1.03-fold, thus contributing a small amount of the average still-missing heritability across traits.

Fifth, our study used the hg38 genome build that, compared with the more recent telomere-to-telomere (T2T) genome builds, misses approximately 8% of DNA sequence37,38. Directly quantifying the contribution of genetic variation absent from hg38 will therefore require recalling variants for the entire UKB, which is not available at present. Nevertheless, we show in Supplementary Note 6 (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 22) using the LD score regression methodology that common variants outside hg38 contribute 4.7% more common-variant heritability (on average across traits) than those in hg38. This gain in heritability is less than the 9.6% increase in the total number of common variants detected with T2T, suggesting that genomic regions outside hg38 are relatively depleted of heritability signal.

Sixth, pedigree-based heritability estimates for diseases (on an underlying liability scale) reported in this study are based on the prevalence of those diseases in the UKB. Therefore, given the healthy-volunteer bias affecting UKB participation46, we expect those estimates to be downwardly biased.

In conclusion, our study fills important gaps in the quantification of heritability from rare variants, and thereby significantly reduces uncertainty regarding how much other factors (for example, non-additive effects) might contribute to the missing heritability of human phenotypes. Our results indicate that future polygenic scores integrating rare variants may improve their predictive power by up to 20% and that discovery of rare trait-associated variants is likely to occur within loci already detected by current GWAS.

Methods

Ethics declaration

This research used data from participants in the UKB study for discovery and from the Vanderbilt University’s biorepository of DNA (BioVU) linked to de-identified medical records for replication of specific results. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant in UKB study. The BioVU study was designed as an opt-out biobank. The UKB study received ethics approval from the North West Centre for Research Ethics Committee (no. 11/NW/0382) and the BioVU study from the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board.

Research collaboration framework

This study mainly used WGSs called with DRAGEN 3.7.8 from 490,542 UKB2,3 participants (data field 24310). Further analyses used SNP-array genotypes and imputed genotypes from two reference panels: Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) plus UK10K and TOPMed. This work is the result of a collaboration between teams at Illumina Inc. (UKB application ID 33751) and The University of Queensland (UKB application ID 12505). All WGS analyses were performed under Illumina’s application. All analyses requiring WGS data or SNP-array data imputed with TOPMed reference panel were performed on the DNA Nexus platform, whereas analyses not requiring individual-level data or not cloud-restricted were performed on local computing clusters.

Selection of samples of European ancestry using SNP-array data

The first sample selection was performed using principal component loadings computed from 1000 Genomes (1KG) for 207,965 autosomal SNPs on the 488,377 samples with SNP-array data available and selecting samples within 3 s.d. of the 1KG reference European ancestry population mean for the first 10 principal components (455,516 samples of European ancestry retained). We selected samples having both SNP-array and WGS data available and consenting to data use to have 452,618 samples of European ancestry in the GWAS analyses.

Processing of raw WGS data

We defined stringent quality control steps to ensure high quality of the remaining genotypic information. We first individually processed each one of the 136,477 autosomes chunks of raw Binary Variant Call Format data. In the first step, we kept all samples and removed variants with the following conditions: minor allele count (MAC) < 30, non-‘PASS’ variant and variants with more than 200 alleles. Multi-allelic variants were split into separate rows and long allele names fewer than 100 characters were renamed. We merged each chunk into a single file containing all autosomes variants of MAC > 30 and all WGS samples (about 130 million variants). We then applied a second quality control step, keeping only the European ancestry samples identified previously, normalizing variants on GRCh38 reference genome and applying the following filters: genotype missingness more than 0.1, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P = 10−8 and sample missingness threshold of 0.05. We had a total of \({M}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}=40,575,204\) SNPs and indels. These samples were used in GWAS analyses. We computed a genomic relationship matrix (GRM) for these 452,618 samples from 583,191 genotyped SNPs of MAF > 0.01. We extracted a sparse GRM with non-zero entries for pairs of relatives with a genomic relationship coefficient (calculated as an allelic correlation, equation (1)) above 0.05 and used it to estimate pedigree-based heritability. We also extracted a set of 347,630 unrelated European ancestry samples for the GREML analyses for which we generated a new set of WGS genotypes. Finally, we computed allele frequencies from the full 452,618 set and the LD scores from the smaller 347,630 set with a block size of 1 Mb and an overlap of 500 kb between blocks.

Grouping variants for GREML-LDMS and covariates processing

To compute MAF and LD partitioned GRMs, each variant was assigned in one of four MAF (0.01–0.1%, 0.1–1%, 1–10%, 10–50%) and further assigned an LD bin (on the basis of the median LD score statistic within each MAF bin) (Supplementary Table 2). LD score statistics were calculated for each SNP as the sum of squared correlations between allele counts at that SNP and that of all nearby SNPs within a 1-Mb window. Sample relatedness between individuals i and k was computed using the following estimator47:

where xij is the minor allele count at SNP j for individual i, M the number of variants used to quantify relatedness and pj the MAF at SNP j.

As a secondary analysis, we further quantified the contribution to trait heritability from ultra-rare variants (MAF < 0.01%) by including an extra GRM in both our GREML and HE analyses. Given that unrelated individuals are unlikely to share ultra-rare variants, this extra GRM was assumed to be diagonal (in fact, it is diagonal dominant) with diagonal elements (Dii for individual i) calculated as

In equation (2), M = 760,525,073 denotes the total number of ultra-rare variants, Mk the number of ultra-rare variants found in exactly k out of N individuals and Sik is the number of variants of count k in the sample (for example, number of singletons when k = 1) that individual i carries. We show in Supplementary Note 3 how equation (2) can be derived from equation (1).

Phenotypes and covariates quality control

From the initial set of 40 million variants, we computed a set of genotypic principal components for each MAF/LD bin independent variants. Parameters for LD pruning was a window of 1 Mb and a R2 = 0.1 for variants of MAF > 0.01 and R2 = 0.01 for MAF < 0.01. In total, 325,484 common variants and 2,435,866 rare variants were retained and 30 genotypic principal components for each bin (that is, 8 × 30 = 240 principal components in total) were computed in the set of unrelated samples using the randomized matrix algorithm implemented in PLINK2 (ref. 48). To obtain genotypic principal components for the full sample set, we computed the loading for each variant then projected them for a per-sample score. For samples included in both sets, the mean correlation between computed and projected genotypic principal components was more than 0.999, with the minimum correlation at 0.982.

We included as base covariates sex, year of birth, assessment centres, fasting time at blood sample collection, month of assessment and prescription drug usage. For the drug usage information, we extracted the field 20003 of the UKB, mapped it to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification codes and grouped in large categories (statins, diuretics, anti-hypertensive, beta-blockers, calcium blockers, angiotensins)49. Furthermore, we also grouped individuals on the basis of their north and east birth coordinates (UKB fields 129 and 130) with a k-means clustering, with different numbers of clusters (10, 20, 50, 100). Individuals with missing birth location (typically, those born outside the United Kingdom) were grouped into a separate cluster. All fasting times greater than 24 h were merged into a single group. Similarly, missing data for assessment centres and month of assessment were grouped into distinct groups. We binarized each of these sets of covariates including each possible year of birth, dropped unused levels for each phenotype and standardized each covariate to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. To reduce data dimensionality (and reduce collinearity), we applied a singular-value decomposition on the covariate matrix from which we selected the top singular vectors associated with eigenvalues explaining in total greater than 99% of the total variance.

Phenotypes were selected on the basis of data availability and clinical relevance. Phenotypes were standardized within each sex to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. For quantitative traits, samples with phenotypic values above 6 s.d. were excluded. Further specific quality control procedures were performed on a trait-dependant basis (Supplementary Table 3).

For each of the 41 phenotypes, we generated 5 sets of covariates on the basis of the singular-value decomposition of the base covariates, the base covariates and principal components, the covariates principal components and the 4 different numbers of k-means-based birth clusters. In total, we fitted as covariates the singular-value decomposition of six different sets of covariates, generated on either the unrelated or full (related) sets of samples.

GREML-based estimates

After generating several sets of covariates and/or phenotypes, we used MPH18 to obtain GREML and Haseman–Elston (HE) regression heritability estimates. HE estimates were obtained by initializing all variance components to 0 (except the residual variance initialized to 1) then performing one iteration of the minimum norm quadratic unbiased estimation implemented in MPH18, which is equivalent to HE regression and allows a proper adjustment for covariates. Our primary analyses used GRMs calculated for each of the eight MAF/LD groups of SNPs and several sets of covariates. Analyses aiming at partitioning \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) across various genomic annotations were obtained using a larger number of GRMs as described below. SNP-based heritability estimates of binary traits were converted on the liability by multiplying them by \(K(1-K)/[\phi {({\varPhi }^{-1}(K))}^{2}]\), where K denotes the prevalence of the binary trait in the population (here the entire sample of 452,618 European ancestry participants in the UKB), ϕ and Φ−1 are the probability density function and quantile function of a standard normal distribution, respectively.

Pedigree-based estimates

Pedigree-based estimates of narrow sense heritability \(({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2})\) were obtained from a set of 171,446 pairs of relatives (GRM value greater than 0.05) identified in the UKB. For all traits except height, educational attainment and fluid intelligence score, we modelled the phenotypic covariance between relatives (conditionally on a set of covariates X) using the following model:

where yi and yj are the phenotypes of individuals i and j, πij their observed GRM value and δij a direct indicator variable that equals 1 when i = j and 0 otherwise. Parameters \({\sigma }_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}\), \({\sigma }_{{\rm{NA}}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{{\rm{E}}}^{2}\) capture additive genetic effects, non-additive genetic effects (including effects of shared environments that are correlated with πij) and residual effects, respectively. We estimated these parameters using a computationally efficient maximum-likelihood procedure implemented in R (‘Code availability’). We then used resulting estimates to calculate \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) as \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}=\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}}/(\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{E}}}^{2}}+\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}}+\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{N}}{\rm{A}}}^{2}})\).

For height, educational attainment and fluid intelligence, which are known to be subject to assortative mating (AM), we used a similar model to ref. 50, that is

where \({d}_{{ij}}={\log (\pi }_{{ij}})/\log (0.5)\) measures the degree of relatedness between pairs of individuals, θ denotes the correlation between genetic values of mates in a population undergoing assortative mating for many generations, and \({\sigma }_{{\rm{AM}}}^{2}={\sigma }_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}\theta \). The first order approximation in equation (4) assumes that θ ≪ 1.

Using estimates of \({\sigma }_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{{\rm{E}}}^{2}\), we then calculated \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) as \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\,=\,\) \(\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}}/(\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{E}}}^{2}}+\hat{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{A}}}^{2}})\). Note that \({\sigma }_{{\rm{AM}}}^{2}\) does not affect the phenotypic variance because its contribution is multiplied \({\log (\pi }_{{ii}})\approx 0\) (in outbred populations). Standard errors for both models (equations (3) and (4)) were obtained using the delta method. We used the TetraHer module51 implemented in the LDAK software tool52 to estimate the heritability of binary traits (under models defined by equations (3) and (4)) directly on the liability scale using the prevalence in the entire sample of European ancestry participants. All analyses were adjusted for the same set of covariates used for GREML analyses.

For each trait, we calculated the EHR as \({\rm{E}}{\rm{H}}{\rm{R}}={\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}/{\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\). Standard errors of EHR were calculated using the delta method assuming the sampling correlation between \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) and \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{P}}{\rm{E}}{\rm{D}}}^{2}\) is zero. This assumption is supported by the fact that pairs of individuals contributing to each estimator are non-overlapping.

Heritability enrichment in coding variants

We partitioned \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) to assess the relative contribution of coding and non-coding variants to trait heritability. Specifically, we focused on coding variants within loci covered by WES technologies. We identified these WES loci using the Resource field 3803 (based on IDT xGen Exome Research Panel v.1.0 and 100 bp flanking region upstream and downstream of each capture target). In total, 408,096 (that is, 1% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%) variants were included in the WES-covered regions and 40,167,108 variants were not. We used the Nirvana pipeline version 3.22.0 (Code availability section) to predict the functional consequence of each variant. We defined a set of coding and non-coding variants on the basis of different consequence categories (Supplementary Table 2). Each of the eight MAF and/or LD groups of variants was then split into three subgroups defined as coding variants within WES loci (0.71% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%), non-coding variants within WES loci (0.29% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%) and variants outside WES loci (99% of all WGS variants with MAF > 0.01%). We then calculated a GRM for each of the 24 resulting subsets of variants. We ran GREML analyses simultaneously fitting those 24 GRMs and also fitting the full set of covariates. We defined the heritability enrichment in coding variants using the following equation:

where \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{C}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{d}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{g}}}^{2}\) is the overall contribution to \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) from coding variants and MCoding the total number of coding variants used in the analysis, that is approximately 0.71% of 408,096. Standard errors of \(\hat{E}({\rm{c}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{d}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{g}})\) were derived using the delta method. We used a similar approach to define and calculate heritability enrichment in other functional annotations (for example, in non-coding variants within WES loci or in variants within loci that are conserved across species). These further analyses are described in the Supplementary Note 1.

GWAS analyses

We performed associations analyses between 34 phenotypes and WGS variants using Regenie53 while fitting all covariates used for heritability estimation (including 100 k-means for birth coordinates). We computed the step 1 leave-one-chromosome-out genomic predictors using 500,999 LD-pruned common variants (LD r2 > 0.9, window size 10 Mb, MAF > 0.05). We then used these predictors for step 2 in both WGS and imputed datasets. We used a stringent P value threshold of 5 × 10−9 to determine genome-wide significance. We used PLINK54 to clump genome-wide significant associations for each trait into independent loci. The PLINK parameters used to perform clumping were an LD r2 < 0.01 between lead SNPs located within 1 Mb of each other.

To further ensure the statistical independence of our associations, we performed a joint analysis fitting all clumped SNPs simultaneously, then only retained genome-wide significant SNPs from the joint analysis. Joint analyses were performed independently for each chromosome while fitting the same covariates as in marginal GWAS analyses and corresponding leave-one-chromosome-out genomic predictors to account for stratification and cryptic relatedness as implemented in Regenie. Joint analyses used multivariate linear regression for quantitative traits and Firth’s penalized logistic regression for binary traits. Specifically, we used the R package logistf (‘Code availability’) to perform Firth’s correction following the procedure described in ref. 53.

We quantified the proportion of variance explained (on the observed scale) by different sets of associations using the following equation:

where m is the number of SNPs in the focal set of association, \({\hat{\beta }}_{jm}\) and \({\hat{\beta }}_{jc}\) the (winner’s curse corrected30,31) estimated marginal and conditional effect size of SNP j, respectively. For binary traits, we calculated \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{G}}{\rm{W}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) as the proportion of liability variance explained by trait-associated variants using the R code provided in ref. 55 (‘Code availability’) with winner’s curse corrected effect sizes (on the observed scale), and allele frequencies and prevalence from the entire sample set. We calculated \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{G}}{\rm{W}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) for CVA and RVAs separately then compared these quantities with their corresponding components of \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{W}}{\rm{G}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) (Fig. 3a). We re-assessed \({\hat{h}}_{{\rm{G}}{\rm{W}}{\rm{A}}{\rm{S}}}^{2}\) for LDL, HDL and ALK in an independent sample of European ancestry participants of the AGD cohort as described in Supplementary Note 2.

We annotated GWAS-identified variants using Gencode v.39 (ref. 56) to determine their position relative to genes and IDT xGen Exome Research Panel (described above) to assess whether a variant lies within a WES locus. We binned trait-associated variants as a function of their distance to the nearest gene. For annotations, we annotated variants using different methods with respect to their functional role. We used unified rank scores annotations provided by dbSNFP57,58 to evaluate the association of rare variants effect sizes with their predicted pathogenic effects. We selected the main annotations (AlphaMissense59, CADD60, Polyphen2 (ref. 61), Revel62, SIFT63) as well PrimateAI3D36, SpliceAI64 and PromoterAI65. We selected a 0.1 and |0.1| thresholds to define pathogenicity in SpliceAI and PromoterAI, respectively. For all other annotations, we used their normalized percentile score and defined pathogenicity as scores above the third quintile of each standardized scores distribution (Supplementary Fig. 6). Conserved variants were defined as variants with Zoonomia phylogenetic score above 2.27, as done previously34.

Finally, we used SuSiE66,67 to fine-map GWAS loci into 95% credible sets. Loci were defined as genomic regions within a 250-kb window on each side of an independent associations. Effect sizes of binary traits were converted to the liability scale using the method in ref. 55.

GWAS of imputed SNPs from HRC + UK10K and TOPMed panels

We ran similar GWAS analyses (to those described above) simply replacing WGS variants with imputed variants from different panels: the HRC + UK10K imputation panel and the TOPMed imputation panels. We applied similar quality control thresholds to both datasets (MAF > 0.01%, hardcalls genotyping missingness rate less than 0.1, sample missingness <0.05, imputation quality INFO score greater than 0.3 and Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium test P > 10−8). We processed the HRC + UK10K-imputed data locally, while TOPMed-imputed genotypes were processed on the DNA Nexus platform. After the quality control process, we were left with 35,152,666 variants for HRC + UK10K imputation and 35,657,593 for TOPMed imputation. For each dataset, we ran Regenie on dosage genotypes for each of the 34 quantitative and binary phenotypes. We used the leave-one-chromosome-out predictions derived from the step 1 computed on WGS data. We used the same clumping and joint analysis parameters described above to identify independent loci. A fine-mapping analysis with SuSiE (as described above) was also performed for each imputed dataset with similar parameters.

Association between variant density and structural variants

For each CVA, we calculated the density of other CVAs (associated with the same trait) within a window of 100 kb. We hereafter refer this quantity as the CVA–CVA density. We perform the same calculations for RVAs and similarly defined an RVA–RVA density for each RVA. Next, we then assigned each of the GWAS variants to an LD block on the basis of European ancestry-specific GRCh38 LD definitions68. We then used publicly available independent associations for tandem repeats (VNTR) and copy-number variants (CNV) and matched them with the traits in our study (20 out of 34 traits, 8,839 unique variants, 9,542 in total). We used ref. 69 for VNTRs, ref. 70 for array-called CNVs (CNVARRAY) and ref. 71 for WES-called CNVs (CNVWES) to inform of the presence or absence of VNTR, CNVARRAY and CNVWES in proximity of a trait-matched GWAS significant variant. We had 3,397 GWAS variants (3,049 common and 348 rare) located on the same chromosome as a structural variant associated with the same trait. We found 300 out of these 3,397 located within 100 kb (172 common and 128 rare). Finally, we fitted two logistic regression models (for common and rare variants separately) regressing a binary indicator of the presence of a nearby (within 100 kb) trait-associated structural variant onto a binary indicator of CVA–CVA or RVA–RVA density equal or larger than 2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Individual-level data of UKB participants can be accessed on application to the UKB (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). Results of fine-mapping analyses of GWAS loci identified in this study are available in Supplementary Data. Data used to generate Figs. 1–3 and Extended Data Figs. 1–9 are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17255322)72. Owing to the nature of the AGD dataset and commercial limitations, individual-level raw data are not available. Genotypes of participants in the 1000 Genomes Project were downloaded under the hg38 genome build at https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/2.0/resources and the T2T genome build (chm13v2.0) at https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/human-pangenomics/index.html?prefix=T2T/CHM13/assemblies/variants/1000_Genomes_Project/chm13v2.0/. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Analyses were performed using publicly available software. Statistical analyses were performed using R (v.4.1.0, v.4.2.1) available from the R site at https://cran.r-project.org/. Firth’s penalized logistic regression was implemented using the R package logistf (v.1.26.1) available through the R site at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/logistf/index.html. GWAS analyses were performed using REGENIE available through GitHub at https://rgcgithub.github.io/regenie/. Genotype data quality control, including filtering and LD pruning, as well as allelic scoring was performed with PLINK v.1.90b6.20 available at https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/ and PLINK2 v.2.00a6LM (authors S. Purcell and C. Chang) available at https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink/2.0/. Fine mapping was performed with SuSiE available through GitHub at https://stephenslab.github.io/susieR/index.html implemented in the R package susieR v.0.12.35. Illumina Nirvana annotation was performed using v.3.22.0 available through GitHub at https://illumina.github.io/NirvanaDocumentation/ and at https://www.illumina.com/science/genomics-research/articles/Connected-Annotations-blog.html. Variance component estimations were performed using MPH v.0.54.0 available through GitHub at https://jiang18.github.io/mph/. Variance component estimation for family-based analyses were performed using a custom R scripts available on GitHub available at https://github.com/loic-yengo/REML-with-sparse-relationship-matrices. Liability scale estimates of pedigree-based heritability for binary traits were obtained using LDAK’s TetraHer module available at https://dougspeed.com/tetraher/. Variance explained by SNPs on the liability scale was obtained using the code provided in ref. 63 and on GitHub at https://github.com/tianwu1117/EStrans/blob/main/EStrans.R. LD scores between hg38 and T2T genome builds were calculated using a custom C++ code available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16550864)73. R scripts used to generate Figs. 1–3 and Extended Data Figs. 1–9 are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17255322)72.

References

Weiner, D. J. et al. Polygenic architecture of rare coding variation across 394,783 exomes. Nature 614, 492–499 (2023).

Halldorsson, B. V. et al. The sequences of 150,119 genomes in the UK Biobank. Nature 607, 732–740 (2022).

Carss, K. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of 490,640 UK Biobank participants. Nature 645, 692–701 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 42, 565–569 (2010).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. K. et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291–295 (2015).

Speed, D. et al. Reevaluation of SNP heritability in complex human traits. Nat. Genet. 49, 986–992 (2017).

Hou, K. et al. Accurate estimation of SNP-heritability from biobank-scale data irrespective of genetic architecture. Nat. Genet. 51, 1244–1251 (2019).

Patxot, M. et al. Probabilistic inference of the genetic architecture underlying functional enrichment of complex traits. Nat. Commun. 12, 6972 (2021).

Palmer, D. S. et al. Analysis of genetic dominance in the UK Biobank. Science 379, 1341–1349 (2023).

Witte, J. S., Visscher, P. M. & Wray, N. R. The contribution of genetic variants to disease depends on the ruler. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 765–776 (2014).

Yengo, L. et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 610, 704–712 (2022).

Polderman, T. J. C. et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 702–709 (2015).

Wainschtein, P. et al. Assessing the contribution of rare variants to complex trait heritability from whole-genome sequence data. Nat. Genet. 54, 263–273 (2022).

Jang, S. K. et al. Rare genetic variants explain missing heritability in smoking. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1577–1586 (2022).

Wessel, J. et al. Rare non-coding variation identified by large scale whole genome sequencing reveals unexplained heritability of type 2 diabetes. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.13.20221812 (2020).

Rocheleau, G. et al. Rare variant contribution to the heritability of coronary artery disease. Nat. Commun. 15, 8741 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Genetic variance estimation with imputed variants finds negligible missing heritability for human height and body mass index. Nat. Genet. 47, 1114–1120 (2015).

Jiang, J. MPH: fast REML for large-scale genome partitioning of quantitative genetic variation. Bioinformatics 40, btae298 (2024).

Mathieson, I. & McVean, G. Differential confounding of rare and common variants in spatially structured populations. Nat. Genet. 44, 243–246 (2012).

Zaidi, A. A. & Mathieson, I. Demographic history mediates the effect of stratification on polygenic scores. eLife 9, e61548 (2020).

Galinsky, K. J., Loh, P. R., Mallick, S., Patterson, N. J. & Price, A. L. Population structure of UK Biobank and ancient Eurasians reveals adaptation at genes influencing blood pressure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 1130–1139 (2016).

Patterson, N. et al. Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age. Nature 601, 588–594 (2022).

Haseman, J. K. & Elston, R. C. The investigation of linkage between a quantitative trait and a marker locus. Behav. Genet. 2, 3–19 (1972).

Yengo, L. et al. Imprint of assortative mating on the human genome. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 948–954 (2018).

Border, R. et al. Assortative mating biases marker-based heritability estimators. Nat. Commun. 13, 660 (2022).

Burren, O. S. et al. Genetic architecture of telomere length in 462,666 UK Biobank whole-genome sequences. Nat. Genet. 56, 1832–1840 (2024).

Hawkes, G. et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis identifies rare, large-effect noncoding variants and regulatory regions associated with circulating protein levels. Nat. Genet. 57, 626–634 (2025).

Hawkes, G. et al. Whole-genome sequencing in 333,100 individuals reveals rare non-coding single variant and aggregate associations with height. Nat. Commun. 15, 8549 (2024).

Hawkes, G. et al. Whole-genome sequencing analysis of anthropometric traits in 672,976 individuals reveals convergence between rare and common genetic associations. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.24.639925 (2025).

Palmer, C. & Pe’er, I. Statistical correction of the Winner’s Curse explains replication variability in quantitative trait genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006916 (2017).

Zhong, H. & Prentice, R. L. Bias-reduced estimators and confidence intervals for odds ratios in genome-wide association studies. Biostatistics 9, 621–634 (2008).

Nielsen, J. B. et al. Loss-of-function genomic variants highlight potential therapeutic targets for cardiovascular disease. Nat. Commun. 11, 6417 (2020).

Finucane, H. K. et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat. Genet. 47, 1228–1235 (2015).

Sullivan, P. F. et al. Leveraging base-pair mammalian constraint to understand genetic variation and human disease. Science 380, eabn2937 (2023).

Eilbeck, K. et al. The Sequence Ontology: a tool for the unification of genome annotations. Genome Biol. 6, R44 (2005).

Gao, H. et al. The landscape of tolerated genetic variation in humans and primates. Science 380, eabn8153 (2023).

Schneider, V. A. et al. Evaluation of GRCh38 and de novo haploid genome assemblies demonstrates the enduring quality of the reference assembly. Genome Res. 27, 849–864 (2017).

Nurk, S. et al. The complete sequence of a human genome. Science 376, 44–53 (2022).

Hu, Y. et al. Leveraging functional annotations in genetic risk prediction for human complex diseases. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005589 (2017).

Márquez-Luna, C. et al. Incorporating functional priors improves polygenic prediction accuracy in UK Biobank and 23andMe data sets. Nat. Commun. 12, 6052 (2021).

Zheng, Z. et al. Leveraging functional genomic annotations and genome coverage to improve polygenic prediction of complex traits within and between ancestries. Nat. Genet. 56, 767–777 (2024).

Fiziev, P. P. et al. Rare penetrant mutations confer severe risk of common diseases. Science 380, eabo1131 (2023).

Tsuo, K. et al. All of Us diversity and scale improve polygenic prediction contextually with greatest improvements for under-represented populations. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.06.606846 (2025).

Steinsaltz, D., Dahl, A. & Wachter, K. W. On negative heritability and negative estimates of heritability. Genetics 215, 343–357 (2020).

Sidorenko, J. et al. The effect of X-linked dosage compensation on complex trait variation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3009 (2019).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1026–1034 (2017).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Galinsky, K. J. et al. Fast principal-component analysis reveals convergent evolution of ADH1B in Europe and East Asia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 456–472 (2016).

Wu, Y. et al. Genome-wide association study of medication-use and associated disease in the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 10, 1891 (2019).

Kemper, K. E. et al. Phenotypic covariance across the entire spectrum of relatedness for 86 billion pairs of individuals. Nat. Commun. 12, 1050 (2021).

Speed, D. & Evans, D. M. Estimating disease heritability from complex pedigrees allowing for ascertainment and covariates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 111, 680–690 (2024).

Speed, D., Hemani, G., Johnson, M. R. & Balding, D. J. Improved heritability estimation from genome-wide SNPs. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 1011–1021 (2012).

Mbatchou, J. et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 1097–1103 (2021).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, s13742-015-0047–8 (2015).

So, H.-C., Gui, A. H. S., Cherny, S. S. & Sham, P. C. Evaluating the heritability explained by known susceptibility variants: a survey of ten complex diseases. Genet. Epidemiol. 35, 310–317 (2011).

Frankish, A. et al. GENCODE 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D916–D923 (2021).

Liu, X., Jian, X. & Boerwinkle, E. dbNSFP: A lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum. Mutat. 32, 894–899 (2011).

Liu, X., Li, C., Mou, C., Dong, Y. & Tu, Y. dbNSFP v4: a comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med. 12, 103 (2020) .

Cheng, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 381, eadg7492 (2025).

Kircher, M. et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 46, 310–315 (2014).

Adzhubei, I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7, 248–249 (2010).

Ioannidis, N. M. et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 877–885 (2016).

Ng, P. C. & Henikoff, S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 11, 863–874 (2001).

Jaganathan, K. et al. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell 176, 535–548.e24 (2019).

Jaganathan, K. et al. Predicting expression-altering promoter mutations with deep learning. Science 389, eads7373 (2025).

Wang, G., Sarkar, A., Carbonetto, P. & Stephens, M. A simple new approach to variable selection in regression, with application to genetic fine mapping. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 82, 1273–1300 (2020).

Zou, Y., Carbonetto, P., Wang, G. & Stephens, M. Fine-mapping from summary data with the “sum of single effects” model. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010299 (2022).

MacDonald, J., Harrison, T., Bammler, T., Mancuso, N. & Lindström, S. Ancestry-specific maps of GRCh38 linkage disequilibrium blocks for human genome research. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.04.483057 (2022).

Mukamel, R. E. et al. Protein-coding repeat polymorphisms strongly shape diverse human phenotypes. Science 373, 1499–1505 (2021).

Hujoel, M. L. A. et al. Influences of rare copy-number variation on human complex traits. Cell 185, 4233–4248.e27 (2022).

Hujoel, M. L. A. et al. Protein-altering variants at copy number-variable regions influence diverse human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 56, 569–578 (2024).

Wainschtein, P. & Yengo, L. Data for h2WGS paper figures. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17255322 (2025).

Yengo, L. SNP-based heritability captured outside of the hg38 genome build. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16550864 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants of the UKB. L.Y. is supported by the Australian Research Council (grant no. FT220100069) and the Snow Medical Research Foundation. P.M.V. was funded by the Australian Research Council (grant no. FL180100072) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant no. 113400). This research has been conducted using the UKB Resource under application numbers 12505 and 33751. S.S. was supported in part by grant nos. NIH R35GM3406, NIH R01HG006399 and NSF CAREER 1943497. We are grateful to B. Neale, B. Pasaniuc, M. Keller, J. Yang, L. Evans, W. Zou, R. Walters, V. Hivert, D. Evans, Y. Wang, A. Martin and P.-R. Loh for helpful discussions at various stages of the project. The samples and structured clinical data used for the analyses described here were obtained from NashBio based on data derived from Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s BioVU biobank, which is supported by institutional funding, private agencies and federal grants including National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded Shared Instrumentation grant nos. S10OD017985, S10RR025141 and S10OD025092; as well as CTSA grant nos. UL1TR002243, UL1TR000445 and UL1RR024975. We are especially grateful to BioVU participants, who generously volunteered to take part in research. The sequencing of 250,000 WGS individuals from BioVU was funded by the AGD consisting of NashBio, Illumina and industry partners Amgen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, GSK, Merck and Novo Nordisk. DNA sequencing was performed at deCODE genetics using Illumina sequencing technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and P.W. designed the study. K.K.-H.F. and L.Y. supervised the work. P.W., Y.Z., J. Schwartzentruber, P.P.F., J. Sidorenko, H.W., I.K. and L.Y. performed statistical analyses. R.B., N.Z., S.S., M.E.G., J.Z. and P.M.V. reviewed the paper and provided guidance. J.M. and P.P.F. performed quality control of phenotype and genetic data of the AGD dataset. I.K. performed the replication analyses in the AGD dataset. P.W. and L.Y. wrote the paper with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.W., J. Schwartzentruber, I.K., P.P.F., J.M. and K.K.-H.F. are employed by Illumina, Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks David Balding and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Sensitivity analyses showing the effect of covariates adjustment on WGS-based heritability estimates.