Abstract

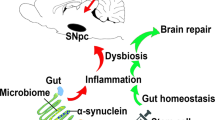

Emerging evidence suggests that Parkinson’s disease (PD) may have its origin in the enteric nervous system (ENS), from where α-synuclein (αS) pathology spreads to the brain1,2,3,4. Decades before the onset of motor symptoms, patients with PD suffer from constipation and present with circulating T cells responsive to αS, suggesting that peripheral immune responses initiated in the ENS may be involved in the early stages of PD1,5,6,7. However, cellular mechanisms that trigger αS pathology in the ENS and its spread along the gut–brain axis remain elusive. Here we demonstrate that muscularis macrophages (ME-Macs), housekeepers of ENS integrity and intestinal homeostasis, modulate αS pathology and neurodegeneration in models of PD8,9. ME-Macs contain misfolded αS, adopt a signature reflecting endolysosomal dysfunction and modulate the expansion of T cells that travel from the ENS to the brain through the dura mater as αS pathology progresses. Directed ME-Mac depletion leads to reduced αS pathology in the ENS and central nervous system, prevents T cell expansion and mitigates neurodegeneration and motor dysfunction, suggesting a role for ME-Macs as early cellular initiators of αS pathology along the gut–brain axis. Understanding these mechanisms could pave the way for early-stage biomarkers in PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

There is growing awareness that the ENS may represent the initial site of αS pathology in PD. Constipation is one of the earliest and most common symptoms in patients with PD and probably reflects ENS dysfunction1,10. The concept of body-first PD is strongly supported by postmortem and multimodal imaging studies showing early Lewy pathology in the ENS of patients with PD, suggesting a caudo-rostral distribution from the intestine to the brainstem and other brain regions2,11. Further, intestinal injections of αS in mice result in the hierarchical spread of Lewy pathology to the brain, strongly implicating the ENS in early stages of disease3,4. However, little is known about the cellular and molecular mechanisms that could trigger the onset of αS pathology in the ENS and progression to the brain.

Tissue-resident macrophages are specialized phagocytes that orchestrate numerous niche-specific functions critical for tissue homeostasis12. In the intestine, macrophages facing the microbiota are continually replaced by blood monocytes and are strategically positioned in the murine lamina propria to engulf penetrating pathogens13. By contrast, ME-Macs reside in the muscularis externa (ME) and support the functional integrity of the myenteric plexus, a network of enteric neurons integral to gastrointestinal motility8,9,14. ME-Macs colonize the murine intestine before birth, are self-maintained but gradually replaced throughout life and maintain enteric neuronal health through the production of neurotrophic factors and the clearance of debris. In the ageing murine intestine, ME-Macs accumulate αS and express PD-associated genes Gba1 and Lrrk2, raising the intriguing question of whether ME-Macs could confer risk in body-first PD pathology15. Whereas central nervous system (CNS)-resident macrophages have been implicated in αS pathology, the role of ENS-resident ME-Macs remains unclear7,16,17.

Here we show that ME-Macs are necessary for the formation and distribution of αS pathology in the intestine and the CNS. In mouse models of PD, including αS transgenic mice and ME injections of patient-derived-αS, ME-Macs, but not enteric neurons, contain misfolded, aggregated αS that coincides with endolysosomal activation in ME-Macs. Mechanistically, we found that ME-Macs in PD mouse models modulate T cell expansion in the ENS. We further show that T cells invade the CNS as αS pathology progresses, and preventing T cell egression ameliorated neurodegeneration. Functionally, we show that injection of anti-CSF1R with anti-CCR2 into the ME, targeting ME-Macs, ameliorated αS pathology in both the ENS and CNS, abolished T cell migration along the gut–brain axis and improved motor defects and neurodegeneration in mouse models of synucleinopathy. Together, our results uncover the role of ME-Macs in the onset and progression of αS pathology and motor impairments along the gut–brain axis in body-first PD.

ME-Macs engulf and modify αS pathology

We first investigated the onset of αS pathology in the ENS versus CNS in 3KL αS transgenic mice, in which αS expression is driven by Thy1 and the 3K construct introduces phenotypic amplification of familial E46K mutations promoting αS tetramer destabilization and aggregation18. 3KL mice demonstrate key features of PD pathology including progressive cortical pathological αS, hereafter defined as s129p+ αS, selective neuronal loss and l-DOPA responsive motor impairments at 8 months of age18. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on mechanically separated duodenal ME demonstrated significantly increased s129p+ αS surrounding HuC/D+ myenteric ganglia, a specialized group of enteric neurons within the ME, of 3KL versus wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 1a–c) at 3 months. We focused on the duodenum, a region highly innervated by the vagus nerve. We also observed s129p+ αS in the ME of postmortem PD tissues (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Further, increased total gut transit time was observed in 3-month 3KL versus WT, suggesting impaired ENS function and constipation (Fig. 1d). However, we found no changes in murine myenteric ganglia and glial volume, measured by HUC/D and glial fibrillary acidic protein, indicating the absence of neuronal death despite αS and enteric pathology (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d). To investigate underlying molecular changes, we performed digital spatial profiling (DSP) on duodenal myenteric plexus in 3-month 3KL versus WT mice using a multiplexed antibody panel consisting of PD-associated targets (Fig. 1e). We observed increased expression of proteins related to autophagy and lysosomal biology in myenteric ganglia of 3KL versus WT, including PINK1, LRRK2 and VPS35 that are associated with familial PD (Fig. 1e). Of note, DSP confirmed upregulation of s129p+ αS in myenteric plexus and elevated total αS levels in both the lamina propria and myenteric plexus (Extended Data Fig. 1e). In the brain, we observed increased punctate αS s129p+ staining in cholinergic neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus of 3KL animals at 6 months compared with age-matched WT controls (Extended Data Fig. 1f–k).

a, Schematic of gut cross-section. b, Confocal image of duodenal myenteric plexus of 3-month WT versus 3KL. c, Quantification of s129p+ αS pathology: n = 6–8 mice; 1 datapoint, average of 1 mouse; 3–10 ROIs per mouse. Three experiments, data analysed using an unpaired t-test. d, Whole gastrointestinal transit time in 3-month WT versus 3KL, n = 9–10. Two experiments, unpaired t-test. e, Hierarchically clustered heatmap of ROI-specific nCounter digital counts across PD-relevant protein targets in duodenal myenteric plexus of 3-month WT versus 3KL, n = 2, 2–3 ROIs per mouse. f–j, Confocal images of engulfed αS by murine MHCII+ duodenal (f) and human CD209+ jejunal (g) ME-Macs, quantified murine LAMP1 lysosomal volume (h) and engulfment of s129p in murine (i) and αS (2F12) in human (j) LAMP1+ lysosomes. n = 8 mice per genotype (h,i) and n = 6 NHC and 8 PD postmortem samples (j). Two experiments, Mann–Whitney test (h–j). k, Volcano plot showing differentially expressed proteins in sorted ME-Macs of 3-month WT versus 3KL. n = 2 per genotype, with 3 mice pooled per biological unit. l, Biological processes enriched in 3-month 3KL ME-Macs, one-sided hypergeometric test. m, Schematic of SAA on sorted duodenal ME-Macs versus enteric neurons. n,o, αS aggregation kinetics through SAA in duodenal enteric neurons (n) and ME-Macs (o). p, SAA-positive versus negative count in different cell lysates. A sample was counted positive if aggregation onset (lag time) was at least 2 h shorter than negative control (PBS). n = 11 (enteric neurons), n = 12 (ME-Macs). Six experiments, Fisher’s exact test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (error bars). FC, fold change; GI, gastrointestinal; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ThT, thioflavin T. Scale bars, 50 μm (a); 10 μm (b); 5 μm (f–j), insets 2 μm (f–j).

Inflammation has been linked to the initiation and progression of αS pathology, and many PD risk genes are enriched in immune cells7,19. Macrophages are the most abundant innate immune cells in the intestinal layers. ME-Macs have a crucial role in maintaining ENS integrity, with their loss leading to constipation8,9,14. We observed no significant differences in ME-Mac distribution across the duodenum, jejunum and ileum of 3-month WT versus 3KL animals (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of ME and lamina propria revealed unaltered differentiation of intestinal macrophages from monocyte precursors at 3 months, 4 months and 6 months of age13 (Extended Data Fig. 2c–f). By contrast, ME-Macs demonstrated increased expression levels of CSF1R and major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) (Extended Data Fig. 2g). We questioned whether ME-Macs, as professional phagocytes of the ENS, engage in the clearance of accumulating αS in surrounding myenteric neurons (Fig. 1f–j and Extended Data Fig. 2h,i). We assessed levels of lysosomal LAMP1 in ME-Macs and found an almost twofold increase in LAMP1 expression in ME-Macs from 3KL versus WT (Fig. 1h). We observed a roughly 14-fold increase in s129p+ αS engulfment by ME-Macs (that is, in LAMP1+ lysosomes) in 3-month 3KL mice compared with age-matched WT controls and a similar 14-fold increase in ME-Macs in postmortem jejunum of PD versus neurologically healthy control (NHC) participants (Fig. 1i,j and Supplementary Table 1a). Further, we found significant (P ≤ 0.05) differential expression of 474 proteins using mass spectrometry in sorted CX3CR1hiCD11clo ME-Macs of 3-month 3KL versus WT mice including lysosomal GRN, CTSB and CD68 (Fig. 1k and Extended Data Fig. 2k). Observed downregulated proteins included NDUFV3, NDUFB10, NDUFA4 and NDUFA7, part of the mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase complex that has been implicated in PD20 (Fig. 1k). Notably, 3-month 3KL ME-Macs acquire signatures related to phagosome maturation and lysosome pathways (collectively referred to as the coordinated lysosomal expression and regulation network)21, suggesting continuing clearance response in ME-Macs exposed to s129p+ αS and confirming our DSP data (Fig. 1l and Extended Data Fig. 2j).

We then asked whether s129p+ αS engulfed by 3KL ME-Macs shows altered pathological activity compared with WT ME-Macs and enteric neurons. We adapted the αS seed amplification assay (SAA) to isolated ME-Macs and enteric neurons to detect prion-like misfolded αS by means of templated aggregation of monomeric αS, which results in amplified binding to thioflavin T22 (Fig. 1m). Notably, lysates from isolated ME-Macs of 3-month 3KL demonstrated accelerated aggregation response within 10 hours in contrast to WT ME-Macs, suggesting increased aggregation activity in 3KL ME-Macs (Fig. 1n,o). No activity was observed in isolated enteric neurons from either 3-month 3KL or WT mice, despite the expression of total αS in enteric neurons but absence in ME-Macs (Fig. 1n–p and Extended Data Fig. 2l). The presence of αS aggregates in 3KL ME-Macs was further confirmed using the amyloid-binding dye Amytracker in isolated ME-Macs by flow cytometry (Extended Data Fig. 2m). In line with SAA data, we observed increased Amytracker signal in ME-Macs of 3-month 3KL versus WT mice but did not find positive signal in lamina propria Macs (Extended Data Fig. 2m,n). Together, these results indicate ME-Macs as potential modulators of αS amyloid aggregates in the ENS.

To further explore the gut–brain axis in synucleinopathy, we directly injected human PD brain-extracted αS fibrils (PD) versus identically extracted human neurological healthy control (NHC) brain preparations into ME of SncaWT/GFP knock-in mice3,4,23 (Extended Data Fig. 3a–e and Supplementary Table 1b). We used a purification protocol specifically designed to select for amyloid and other highly insoluble proteins24. The brain-extracted αS fibrils are hereafter designated as PD-αS and NHC-αS, respectively. Duodenal injection of PD-αS but not NHC-αS in ME increased endogenous αS expression in myenteric ganglia (Fig. 2a,b). We observed significant upregulation of s129p+ αS immunoreactivity at 1 month and 3 months postinjection, predominantly around neuronal cell bodies and to a lesser extent, in extraganglionic neurons, similar to 3-month 3KL (Fig. 2a–d). Prolonged total gut transit time was found post-PD-αS injection (Fig. 2e). Significant increase of s129p+ αS inclusions was observed at 3 months post-PD-αS injection in the brainstem (Fig. 2f,g). Further, an increased fraction of s129p+ αS in dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) was observed, suggesting a potential route for pathological spread from the ENS to the CNS (Fig. 2h,i). We observed a selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc at 3 months post-PD-αS versus NHC-αS injections (Fig. 2j,k and Extended Data Fig. 3f). By contrast, no dopaminergic neuronal loss was observed in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), consistent with the region-specific dopaminergic neuronal vulnerability in patients with PD25 (Fig. 2k). We then investigated whether ME-Macs engulfed s129p+ αS in response to PD-αS injections and observed a roughly 13-fold increase in lysosomal s129p+ αS in ME-Macs in PD-αS-injected animals compared with NHC-αS-injected controls at 1 month postinjection (Extended Data Fig. 3g–i). However, we found no overt production of inflammatory cytokines in the ME, suggesting the absence of local inflammation in the ME induced by αS injections (Extended Data Fig. 3j). These data indicate that body-first αS pathology, triggered by PD-αS injection into the ME, propagates from the ENS to the CNS, leading to region-specific dopaminergic neuron loss.

a,b, αS s129p+ pathology in duodenal myenteric plexus at 1 month (a) and 3 months (b) post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS injection. c, Quantification of αS-GFPhigh cells per mm2 at 1 month and 3 months postinjection. n = 6 for αS-NHC, 1 month; n = 8 for αS-PD, 1 month; n = 5 for αS-NHC and αS-PD, 3 months. Two experiments. d, Quantification of αS s129p+ pathology at 1 month and 3 months postinjection. One datapoint, average of 1 mouse, 5–9 ROIs per mouse. n = 6 mice for αS-NHC, 1 month; n = 8 for αS-PD, 1 month; n = 5 mice for αS-NHC and n = 6 mice for αS-PD, 3 months. Two experiments. e, Gastrointestinal transit time at 1 month and 3 months postinjection. n = 7 mice for αS-NHC, n = 6 mice for αS-PD, 1 month; n = 7 mice for αS-NHC, n = 5 mice for αS-PD, 3 months. Two experiments, data analysed using two-way ANOVA (c–e) with Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test (d). f, Widefield images of s129p+ αS pathology in brainstem at 3 months postinjection, blue arrows highlight αS inclusions. g, Quantification of s129p+ αS pathology in brainstem at 1 month and 3 months postinjection, n = 4 mice for αS-NHC, 1 month and n = 5 mice for αS-NHC, 3 months; αS-PD, 1 month and 3 months. Two experiments, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. h, αS s129p+ pathology in SNpc at 3 months post-NHC versus PD-extract injection. i, CTCF of s129p αS normalized to total αS, n = 5 mice per group. Two experiments, unpaired t-test. j, TH+ immunostainings in SNpc and VTA using DAB, 3 months post-treatment. brightfield micrograph of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc. k, Unbiased stereological quantification of TH+ cells in SNpc and VTA, n = 7 mice for αS-NHC, SNpc and VTA, n = 8 mice for αS-PD, SNpc and VTA. Three experiments, mixed-effect model with multivariate t-distribution posthoc test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (error bars). Scale bars, 100 μm (a,b), insets 20 μm (a,b,j); 20 μm (f,j); 50 μm (h); 500 µm (j). DA, dopaminergic.

A gut-to-brain T cell axis in PD

Recent studies reported increased CD3+ T cell numbers in intestinal biopsies of constipated patients with PD versus healthy control participants and in PD mouse models that show prodromal constipation26,27. Further, increased numbers of T cells are found in the plasma and brain of patients with PD, but with unknown origin5,6,28. In addition to endolysosomal pathways, proteomic signature analysis on isolated ME-Macs from 3KL mice revealed upregulation of antigen presentation and leukocyte migration pathways (Fig. 1l and Extended Data Fig. 2j). MHCII, which enables antigen presentation to T cell receptors (TCRs), was found increased on ME-Macs (Extended Data Fig. 2g). These data suggest a potential engagement of adaptive immune cells after ME-Mac uptake of pathological αS. Hence, we asked whether CD3+ T cells are expanded in the ENS in response to αS pathology. IHC on myenteric plexus of 3-month 3KL versus WT mice showed increased numbers of CD3+ T cells in 3-month 3KL mice (Fig. 3a–c). Of note, T cells were primarily found adjacent to myenteric ganglia (Fig. 3a,b). Flow cytometry confirmed increased proportions of CD3+ T cells among total CD45+ cells isolated from 3-month ME, with an increased CD4+ to CD8+ ratio in 3-month 3KL mice (Fig. 3d–e and Extended Data Fig. 4a). This is in line with previous studies demonstrating a predominant role for CD4+ T cell responses in αS pathology in mice and human PD29. Of note, T cell expansion was less obvious in the lamina propria (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Further, the increased proportions of CD3+CD4+ T cells in myenteric plexus were also observed in the ME PD-αS versus NHC-αS injection model, as demonstrated by IHC and flow cytometry (Fig. 3f–j). We assessed T cells in the ME of human patients with PD by performing IHC on postmortem jejunum and observed similar expansion of CD4+ T cells in myenteric plexus of PD versus NHC patients (Fig. 3k,l and Supplementary Table 1a). Together, these results show that CD4+CD3+ T cells regionally infiltrate the ME of PD mouse models and patient tissues.

a,b, CD3+ T cells in duodenal myenteric plexus of 3-month WT (a) versus 3KL (b) mice. Inset, ROI for counting. c,d, CD3+ T cells in 3KL myenteric plexus per ROI, quantified by IHC (c) and FACS (percentage of ME CD45+ cells) (d). n = 6 mice (WT), n = 7 mice (3KL) (c) or n = 10 mice (WT), n = 12 mice (3KL) (d). Two (c) and four (d) experiments, data analysed using an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction (c,d). e, FACS plots of CD4+CD8+ ME T cells in 3-month WT versus 3KL. f,g, CD3+ T cells in duodenal myenteric plexus post-NHC-αS (f) versus PD-αS (g). Inset, ROI used for counting. h,i, CD3+ T cells in 3KL myenteric plexus per ROI, quantified by IHC (h) and FACS (percentage of ME CD45+ cells) (i). n = 6–7 (h) or n = 4 (i) mice per genotype. Two experiments, unpaired i-test (h) with Welch’s correction (i). j, FACS plots of CD4+CD8+ ME T cells post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS. k,l, DAB staining of ME CD4+ T cells in jejunum of PD versus NHC patients (k) and quantification (l). n = 7–8 per disease status. Two experiments, unpaired t-test. m,n, CD3+ T cells in dura mater of 3-month 3KL versus WT (m) or 1 month post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS (n) quantified by FACS (percentage of total dura mater CD45+ cells), n = 4 mice (WT), n = 6 mice (3KL) (m) or n = 4 mice per treatment (n). Two experiments, unpaired t-test. o, Schematic of T cell photoconversion in VHD mice, 5 days post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS. p, Dendra-red CD3+ T cells in dura mater at 1 month post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS injection and UV versus non-UV photoconversion, n = 5–6 per genotype. Note minor leakage in the absence of UV illumination. Four experiments, two-way ANOVA. q, Dendra-red versus dendra-green CD3+ T cells in dura mater, 1 month post-PD-αS injection and UV illumination in ME. Representative of five mice (overview). r, Boxplot quantifying clonotype overlap between ME and dura mater through the Jaccard index (Methods, equation (1)) of NHC-αS- and PD-αS-injected groups for α (A) and β (B) TCR chains. Bonferroni-adjusted unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. Data are shown as boxplots: the median is the central line; hinges indicate the first and third quartiles; whiskers extend to the most extreme values within the 1.5× interquartile range and points beyond the whiskers are plotted as individual outliers. s, Alluvial plots of the top ten most frequent T cell clone β chains in ME and dura mater of one representative mouse from PD-αS. t, Boxplot quantifying the clonotype overlap between the ME and dura mater through the expanded index (Methods, equation ( 3)) of NHC-αS- and PD-αS-injected groups for α (A) and β (B) TCR chains. Bonferroni-adjusted unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (error bars). Scale bars, 500 μm (a,b,f,g); 50 μm (k); 1 mm (q); insets 50 μm (a,b,f,g); 25 μm (q).

Next, we asked whether T cells could distribute from the ENS to CNS according to the spatiotemporal distribution of αS pathology. Many studies have demonstrated infiltration of CD3+ T cells into the CNS in preclinical models of PD and postmortem tissue, but the peripheral site of origin remained elusive29. We first evaluated CD3+ T cell numbers in the dura mater, a peripheral-brain interface in the leptomeninges that allows access of T cells into the brain parenchyma30. We found that CD3+ T cells were significantly elevated in the dura mater of PD-αS-injected and 3KL mice (Fig. 3m,n and Extended Data Fig. 4c). To test whether dural CD3+ T cells could originate from the intestine, we injected PD-αS versus NHC-αS in Vav-H2B-Dendra2 (VHD) mice expressing H2B-dendra2 protein under control of haematopoietic Vav, allowing tracking of dendra2 photoconverted immune cells31 (Fig. 3o). Ultraviolet (UV) exposure of ME from VHD mice caused irreversible photoconversion in ME CD3+ T cells, Ly6G+ neutrophils and CD11b+ myeloid cells at 24 hours post-UV illumination (Extended Data Fig. 4d–f). UV exposure did not label circulating CD3+ T cells in the blood at 1 hour post-UV (Extended Data Fig. 4g). We characterized photoconversion kinetics in T cells at 3 days, 7 days and 31 days post-UV illumination and PD-αS injection and detected circulating dendra-red+ T cells in the blood between 3 days and 7 days postillumination but declining at 31 days, whereas photoconverted T cells were increasingly observed in the dura mater between 7 days and 31 days postillumination (Fig. 3p and Extended Data Fig. 4h,i). Notably, roughly 2% of lymphocytes are dendra-negative, probably reflecting incomplete Vav promoter efficiency. A small percentage of T cell photoconversion was detected in the lamina propria, highlighting their potential contribution to the dura mater T cell pool (Extended Data Fig. 4h). Minor dendra-red cell presence was observed in dura mater of control illuminated αS-treated mice, indicating slight leakiness of the model (Fig. 3p and Extended Data Fig. 4j). In addition, photoconverted CD64+ cells were detected in the dura mater of PD-αS-injected mice, suggesting migration of myeloid cells from the duodenum (Extended Data Fig. 4k). Whole-mount imaging of the dura mater of PD-αS-injected mice confirmed presence of dendra-red CD3+ T cells (Fig. 3q and Extended Data Fig. 4l,m). Together, these data indicate expansion of ME T cells in the context of αS pathology, and that a proportion of intestinal T cells migrates to the dura mater.

To confirm that T cells in the ME and brain were clonally related, and to measure clonal expansion, we performed TCR sequencing on ME and dura mater, striatum and hippocampus samples collected 10 days post-NHC-αS and PD-αS injection. The number of TCRs recovered from striatum and hippocampus at this early time point was very small, so we focused analysis on the dura mater. The diversity (inverse Simpson) of the repertoires showed a trending decrease following PD-αS injection, suggestive of antigen-driven clonal expansion (Extended Data Fig. 5a). In agreement with the increased dendra-red CD3+ T cells observed in PD-αS-injected mice, there was an increase in TCR sequence sharing between ME T cells and dura mater T cells following injection of PD-αS (Fig. 3r). The degree of overlap was greater for TCRα than for TCRβ, reflecting the higher diversity of the TCRβ32. Many of the TCRs shared between ME and dura mater showed significant clonal expansion, consistent with previous antigen recognition (Fig. 3s and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). A trend for increased sharing of expanded ME T cells to the dura mater in PD-αS-injected versus NHC-αS-injected mice was observed (Fig. 3t). Taken together, these data indicate expansion of ME T cells in the context of αS pathology, and that a proportion of expanded intestinal T cells migrates to the dura mater, potentially mediated by PD-αS.

ME-Mac–T cell crosstalk through TGFβ1

We next explored whether the observed T cell expansion involved crosstalk with ME-Macs that are reactive to αS pathology. IHC and 3D reconstruction revealed close proximity between ME-Macs and T cells in the myenteric plexus of 3-month 3KL mice and patients with PD (Fig. 4a). To elucidate transcriptional changes in ME-Macs and T cells on αS pathology and cellular interactions among them, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) using the 10X Genomics platform on fluorescence-activated cell-sorted duodenal ME CD3+ cells and ME-Macs of 4-month 3KL and WT mice, a time point chosen to capture profiles after initial T cell expansion (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). After quality control, we ran unsupervised clustering on 2,748 cells and identified clusters of ME-Macs (Adgre1 and Csf1r) and T cells (Cd3 and Cd8a) (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 6b–d). We found three transcriptionally distinct ME-Mac subclusters based on Cd163 and Ccr2 expression, resembling previously described tissue-resident macrophage subtypes associated with blood vessels (Lyz2, Mrc1, Pf4) and neurons (H2-Dma, H2-Aa, Cd74)33 (Fig. 4b, Extended Data Fig. 6d and Supplementary Table 2). Cd163+ ME-Macs expressed transcripts involved in leukocyte migration and chemotaxis, whereas Ccr2+ ME-Macs were enriched in transcripts related to antigen processing (Extended Data Fig. 6e). The third cluster, hereafter referred to as Cd163−Ccr2− ME-Macs, demonstrated upregulation of genes related to leukocyte migration and cytokine signalling. We validated the presence of CD163+, CCR2+ and CD163−CCR2− IBA1+ ME-Macs using flow cytometry and IHC (Fig. 4c,d and Extended Data Fig. 6f–l). Flow cytometry revealed no differences in absolute subcluster numbers between WT and 3KL mice at 3–4 months (Extended Data Fig. 6h). However, CCR2+ ME-Macs were generally significantly fewer in 3KL mice, reaching significance at 6 months. IHC showed altered proportions of CD163+ and CD163−CCR2− ME-Macs in 3-month-old 3KL mice but no differences in PD-αS- versus NHC-αS-injected animals (Extended Data Fig. 6i–l).

a, Confocal images of ME-Macs and ME T cells in 3-month 3KL and PD postmortem ME. Representative of more than four experiments. b, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of unsupervised clustering of ME-Macs and T cells from ME assigned into colour-coded subclusters. scRNA-seq data obtained from fluorescence-activated cell-sorted ME-Macs and ME CD3+ cells of 4-month 3KL and WT subjected to 10X Genomics scRNA-seq (n = 2,748 cells). Four biologically independent samples were used, and samples were sequenced in n = 2 batches from WT versus 3KL. One sample represents ME pooled from 4 mice. c,d, FACS plots (c) and confocal images (d) demonstrating CD163+, CCR2+ and CD163−CCR2− duodenal ME-Macs in 3-month WT versus 3KL (c) or 3KL (d). Data representative of three experiments. e,f, Confocal images (e) of s129p engulfment by CD163+ and CCR2+ duodenal ME-Macs in 3-month WT versus 3KL and quantification (f), n = 4 per genotype. One experiment, two-way repeated measures ANOVA. g, Heatmap showing top ligands expressed in ME-Macs ranked on the basis of area under the precision–recall curve (AUPRC) with 3KL T cells as receivers. h, Circos plot showing ligand–receptor pairs between ME-Macs and T cells in 4-month 3KL. Bottom, top eight ligands expressed by 3KL ME-Macs. Top, differentially expressed receptors in 3KL versus WT T cells. i,j, Confocal images (i) of duodenal ME T cells in Cx3cr1+/+.Tgfb1LoxP versus Cx3cr1CreERT2.Tgfb1LoxP at 10 days post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS injection and quantification (j), n = 4 mice (CTRL, NHC-αS and PD-αS; FLOX, NHC-αS) and n = 5 mice (FLOX, PD-αS). Two experiments, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (error bars). Scale bars, 30 μm (3KL, a); 50 μm (PD, a); 100 μm (d); 50 μm (i). AUPRC, area under the precision–recall curve.

We next examined whether CD163+ and CCR2+ ME-Macs showed increased capacity to engulf s129p+ αS in PD models. In 3-month 3KL mice, both populations showed increased αS engulfment compared with WT (Fig. 4e,f). Similarly, in the injection model, αS engulfment was increased in both ME-Mac subsets 1 month post-PD-αS injection (Extended Data Fig. 6m,n). These findings indicate that ME-Macs show an enhanced ability to internalize αS in the context of PD-associated pathology.

To evaluate how ME-Macs could modulate T cells transcriptionally, we used NicheNet on our scRNA-seq data to predict ligand–receptor interactions between ME-Macs and T cells34 (Fig. 4g,h and Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). We focused on disease-specific interactions under 3KL conditions, selecting receptor transcripts that were differentially expressed in T cells and corresponding ligands expressed by 3KL ME-Macs. The ligand with the highest regulatory potential was Tgfb1, which was predominantly expressed by CCR2+ and CD163+ ME-Macs, whereas its canonical receptor Tgbr2 was expressed by ME T cells35 (Fig. 4g,h and Extended Data Fig. 7c). We next investigated the role of TGFβ1 in ME-Mac–T cell crosstalk in the context of αS pathology. Tamoxifen-treated Cx3cr1CreERT2.Tgfb1LoxP mice were injected with NHC-αS or PD-αS injections 4 months later, when Tgfb1 deletion is retained only in self-maintaining macrophages8 (Extended Data Fig. 7d–f). Notably, PD-αS failed to induce T cell expansion in Cx3cr1CreERT2.Tgfb1LoxP mice, unlike in Cx3cr1+/+.Tgfb1LoxP and NHC-αS controls (Fig. 4i,j). Whereas absolute IBA1+ ME-Mac counts, CD163+ or CCR2+ proportions, and lysosomal numbers remained unchanged, a proportional increase in CD163−CCR2− IBA1+ ME-Macs was observed in both genotypes (Extended Data Fig. 7g–j). T cell numbers in the lamina propria were unaffected12 (Extended Data Fig. 7k,l).

ME-Mac targeting reduces PD pathology

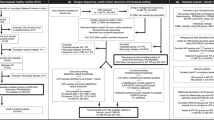

We next asked whether ME-Macs could directly modulate the expansion of T cells to the brain in response to αS pathology. We aimed to deplete ME-Macs by injecting anti-CSF1R antibody (AFS98) into duodenal ME at 24 hours before αS treatment9 (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 8a). We combined anti-CSF1R with anti-CCR2 antibody (MC21) treatment to circumvent immediate monocyte replenishment and to extend the depletion of ME-Macs in the myenteric plexus8. Of note, this approach resulted in minor depletion of other immune cells, including reduced numbers of ME monocytes, ME eosinophils and lamina propria monocytes at 5 days post-treatment, as well as decreased circulating neutrophils at 5 days and circulating monocytes at 24 hours and 5 days post-treatment (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). Microglia and border-associated macrophages were not affected by this treatment (Extended Data Fig. 8d). T cell expansion on PD-αS versus NHC-αS injection was abolished in the myenteric plexus at 1 month post-anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 versus IgG treatment, suggesting that ME-Macs are potentially involved in the T cell expansion in αS models (Fig. 5b,c). Further, we observed amelioration of s129p+ αS pathology at 1 month post-PD-αS injection in mice pretreated with anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 compared with IgG, suggesting the contribution of ME-Macs in the progression of αS pathology along the ENS (Fig. 5d). Given that fractions of T cells could travel from the ME to the dura mater on PD-αS treatment, we next asked whether ME-anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 could alter T cell expansion in the CNS. We focused on the brainstem and striatum that sequentially undergo αS pathology per Braak staging11. We found a significant increase in CD3+ cell number in the brainstem of 3 months post-PD-αS versus NHC-αS injection; however, this increase was abolished when mice were pretreated with anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 (Fig. 5e,f). In addition, s129p+ αS pathology was ameliorated in the brainstem, suggesting that ME-Macs contribute to the progression of αS pathology from ENS to CNS (Fig. 5g). Next, we focused on the striatum, a region highly innervated by dopaminergic neurons, the degeneration of which is suggested to underlie motor symptoms in PD36. We observed increased CD3+ cell numbers in the dorsal border of the striatum adjacent to the corpus callosum at 3 months post-PD-αS versus NHC-αS injection, whereas mice pretreated with anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 failed to initiate CD3+ cellular expansion (Fig. 5h–j). We next investigated whether the directed depletion of ME-Macs could ameliorate motor behaviour on αS pathology. Animals injected with PD-αS versus NHC-αS showed impaired performance on a slowly accelerating rotarod at 3 months postinjection; however, this deficit was reversed in mice pretreated with anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 (Fig. 5k). Consistent with this, pretreatment with anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 also mitigated the region-specific loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc induced by PD-αS (Fig. 5l–n). Finally, treatment with fingolimod, which downregulates the sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor and prevents lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes37, mitigated PD-αS-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the SNpc specifically, suggesting a role for T cell trafficking in αS-mediated neurodegeneration (Fig. 5o,p). Together, our data suggest that ME-Macs modulate T cell response along the gut–brain axis in the context of αS pathology. Prolonged anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 treatment of the ME prevents T cell expansion and ameliorates s129p+ αS pathology in the ENS and CNS, while preventing T cell egression into the bloodstream reduced neurodegeneration. Together, our findings suggest that manipulation of the gut–immune–brain axis could modulate motor phenotype and ameliorate neurodegeneration in PD.

a, Schematic of directed ME-Mac depletion using anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 treatment. b, Confocal images of CD3+ T cells, IBA1+ ME-Macs and αS in duodenal myenteric plexus of NHC-αS versus PD-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 versus IgG treatment, 1 month postinjection. c,d, Quantification of CD3+ T cells (c) and s129p+ αS pathology (d) in myenteric plexus at 1 month post-NHC-αS versus PD-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 versus IgG treatment. n = 5 mice for NHC-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2; n = 6 mice for PD-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2; n = 7 mice for NHC-αS and PD-αS, IgG (c) or n = 5 mice for NHC-αS, IgG and anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2; n = 8 mice for PD-αS, IgG and n = 6 mice for PD-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 (d). Two experiments, data analysed using two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. e,f, Confocal images of CD3+ T cells in brainstem at 3 months post-treatment (e) and quantification (f), n = 6 mice. Two experiments, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. g, S129p+ αS pathology in brainstem at 3 months post-treatment, n = 5 mice. Two experiments, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. h–j, Confocal images of CD3+ T cells in forebrain (h) (inset, dorsal border of the striatum) at 3 months post-treatment (i) and quantification (j), n = 5 mice for NHC-αS, IgG and anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 and n = 7 mice for PD-αS, IgG and anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2. Two experiments, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. k, Latency to fall on an accelerating rotarod at 3 months post-treatment, n = 20 mice for NHC-αS, IgG; n = 27 mice for PD-αS, IgG; n = 10 mice for NHC-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2; n = 14 mice for PD-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 over seven experiments, two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test. l, TH+ immunostainings in SNpc and VTA of ventral midbrain sections using DAB, 3 months post-treatment. m,n, Unbiased stereological quantification of TH+ cells in SNpc (m) and VTA (n), n = 5 mice for NHC-αS and PD-αS, IgG; n = 6 mice for NHC-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2; n = 7 mice for PD-αS, anti-CSF1R/anti-CCR2 over three experiments. Two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test (m). NS, not significant. o,p, TH+ immunostainings using DAB, 3 months post-PD and fingolimod treatment (o) and unbiased stereological quantification (p), n = 5 mice. One experiment, unpaired t-test. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (error bars). Scale bars, 50 μm (b,h,e,f,i); 500 µm (l,o).

Discussion

Our work suggests that ME-Macs contribute to the initiation and spreading of pathological αS along the gut–brain axis in PD. We found that ME-Macs modulate s129p+ αS pathology on engulfment and facilitate T cell expansion from ENS to CNS. Consistently, directed ME-Mac depletion ameliorates the progression of αS pathology towards the brainstem and motor dysfunction. These results indicate ME-Macs as early cellular mediators of αS pathology along the gut–brain axis, presenting cellular mechanisms that may underlie body-first PD.

In contrast to familial PD, sporadic PD is probably the result of interacting genetic and environmental factors that influence the region-specific onset and cell-to-cell progression of αS38,39. In parallel, the Braak staging system implies that in body-first patients with PD, initial deposition of pathological αS occurs in the ENS before it migrates and distributes to the CNS11. In the brain, αS pathology further spreads in a rostro-caudal manner from inferior brain regions to midbrain regions where it perturbs normal motor functions. We observed early αS pathology in the ENS of 3KL αS transgenic mice, coinciding with increased gastrointestinal transit time. Further, we found evidence that PD-αS directly injected into the ME could propagate to the brain and cause progressive neurodegeneration and motor impairments in mice, highlighting its significance as a model for studying αS propagation along the gut–brain axis. Notably, we observed region-specific s129p+ αS deposition in the ENS correlated with the upregulation of PINK1, LRRK2 and VPS35, associated with late-onset PD and involved in lysosomal biology40,41. This is in line with previous work demonstrating endolysosomal dysfunction in mice injected with αS fibrils into the ME, probably reflecting the continuing clearance of αS aggregates by macrophages and underscoring the key role of non-neuronal cells in impaired αS degradation3. The observed increase in total gut transit time in these mice suggests that ENS integrity could be directly affected by phosphorylated αS. The slow-transit phenotype was ameliorated by 3 months postinjection, suggesting that intestinal immune responses can resolve with time.

Our study highlights a central role for ME-Macs in the development of αS pathology along the gut–brain axis. ME-Macs are self-maintaining macrophages that have a crucial role in ENS homeostasis and function8,9. In PD mouse models, we found that ME-Macs have an increased level of engulfed s129p+ αS and upregulated autophagy and lysosomal clearance pathways. Furthermore, SAA results indicate that ME-Macs contain most of pathological misfolded αS compared with enteric neurons, suggesting the role of macrophages in misfolding and progression of pathological αS19,24. This raises the possibility that ME-Macs, although acting as a clearance mechanism, may also provide a microenvironment that promotes protein aggregation, consistent with observations of low-level physiological αS aggregates. Directed depletion of ME-Macs prevented the distribution of s129p+ αS inclusions along myenteric neurons of the ENS and CNS. However, we note that our depletion strategy also caused a slight reduction in eosinophils and monocyte numbers. Further, ME-Macs express PD risk factors linked to endolysosomal pathways, including Gba1, Lrrk2, Vps35 and Ctsd, the last involved in αS degradation41. These findings suggest that ME-Macs serve as early modulators of αS pathology. Of interest, microglia have been shown to phagocytose extracellular αS through the initiation of autophagy but then fail to clear the internalized αS in the brains of human αS-overexpressing mouse models19,42. These studies and our findings highlight tissue-resident macrophages along the gut–brain axis as key contributors to αS misfolding. Whereas our model uses direct administration of pathogenic αS fibrils, the endogenous triggers of αS aggregation in the human gut remain undefined43. Environmental and intrinsic factors may trigger αS aggregation in the gut. Pesticide exposure (for example, rotenone) induces enteric αS pathology in rodents44. Viral infections (for example, norovirus) upregulate αS expression, and ageing is associated with progressive accumulation and phosphorylation of αS in mice44. These mechanisms provide potential links between our models and human PD pathophysiology. Further research is needed to unravel the mechanisms governing αS uptake and degradation and to determine whether targeting specific pathways in microglia and ME-Macs can modify disease progression. Of note, pharmacological inhibition of LRRK2 reduces αS pathology and its propagation in neocortex, striatum and corpus callosum through enhanced lysosomal clearance of αS45. Further experiments are warranted to determine the role of ME-Macs in αS misfolding and the role of LRRK2 and GBA1 herein.

Our study in body-first PD models further suggests that early ME-Mac dysfunction promotes local T cell expansion, enabling their migration to the CNS. We further observed expansion of CD3+ T cells in the ENS of body-first PD models. CD4+ T cell infiltration has been observed in postmortem human PD samples6. Moreover, αS-overexpressing mouse models deficient in CD4+ T cells are protected against midbrain neuronal loss, and recent work demonstrated αS-reactive circulating CD4+ T cells in patients with early-stage PD, but with unknown origin5,6,29. Here we show that T cells can infiltrate and expand in ME of PD models, coinciding with αS propagation and spread to the CNS. Treatment with fingolimod mitigated neurodegeneration in PD-αS-injected mice, supporting the role for αS-induced T cell trafficking in disease progression; however, the broader immunomodulatory effects of fingolimod warrant further investigation to clarify specificity. CD3+ T cells migrate from ME to the dorsal border of the striatum and lateral ventricle, possibly through the ependymal epithelial layer that intersects the ventricles and parenchyma. The ependymal layer was recently suggested as a potential entry site of infiltrating leukocytes and demonstrates an extensive amount of aggregated αS in patients with PD46. Alternatively, circumventricular organs lacking tight junctions and featuring fenestrations, such as the area postrema or subfornical organ, may serve as entry points for gut-derived immune cells47. However, the underlying mechanisms driving T cell trafficking and entry into the CNS, remain unclear. Peripheral T cells have been demonstrated to enter the CNS by means of recognition of a mitochondria-derived antigen, thereby driving dopaminergic neuronal loss in Pink1-deficient mice35. Systemic lipopolysaccharide induces the recruitment of T cells and monocytes to the brain in the context of αS pathology, suggesting that peripheral inflammation may act as a trigger for immune cell infiltration in PD48. Thus, T cell trafficking from the ENS to the CNS may be driven by αS-induced neuronal inflammation, coupled with human leukocyte antigen-associated αS peptide presentation by antigen-presenting cells in the CNS.

Finally, directed ME-Macs depletion reduces CD3+ T cell expansion and αS pathology, raising key questions about the mechanisms by which ME-Macs and T cells communicate. First, the role of dendritic cells, as the quintessential antigen-presenting cells, remains unclear in this process. ME-Macs upregulate MHCII in the presence of αS pathology, consistent with the genetic association between the human leukocyte antigen region and PD, although this has not yet been specifically described for tissue-resident macrophages49. A critical future objective is to determine which lysosomal antigens are presented on MHCII by ME-Macs following αS engulfment. Alternatively, ME-Macs may transfer unprocessed antigens to dendritic cells for subsequent T cell priming. Of note, CD163+ ME-Macs are enriched in perivascular-associated genes and are resemblant of border-associated macrophages in the CNS, recently implicated in the recruitment and activation of CD4+ T cells in an αS-overexpressing mouse model16,50. Consistent with our findings and enhanced expression of MHCII on ME-Macs, depletion of BAM led to reduced expansion of CD4+ T cells and prevention of disease progression16. The location and timing of ME T cell priming, particularly within secondary lymphoid organs such as Peyer’s patches and mesenteric lymph nodes, remain to be elucidated. Notably, our findings suggest that TGFβ in ME-Macs has a key role in modulating T cell expansion in response to αS pathology, as depletion of TGFβ in ME-Macs ameliorated the αS-induced T cell increase. TGFβ is critical for driving T cell differentiation into either regulatory or Th17 phenotypes; yet cytokines such as IL-6 ultimately dictate the final fate of these T cells. Understanding these pathways will provide essential insights into the interplay between ME-Macs and T cells in synucleinopathy.

The gut–brain axis in PD has been extensively implicated in clinical settings, however, the cellular mediators involved in this process have been unclear. The unique properties of ME-Macs, such as their ability to engulf and modify αS aggregates, as well as their impact on T cell expansion and migration, highlight their significance in the earliest stages of αS pathology in PD. Targeting ME-Macs could offer potential therapeutic avenues for modulating αS pathology and its progression in PD or, alternatively, represent a valuable diagnostic biomarker for early immune changes in PD pathogenesis.

Methods

Mice

All experiments were performed in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and following local ethical advice. Experimental procedures were approved by the UK Home Office and ethical approval was granted through consultation with veterinary staff at University College London (UCL). For all experiments, mice were obtained from the following sources and subsequently bred side by side in cages: C57BL/6J (WT) mice were obtained from Charles River UK, C57BL/6-Tg(Thy1-SNCA*E35K*E46K*E61K)3798Nuber/J (3KL) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. VHD (B6.tg(HD2)) mice were obtained from V. Cerovic (Institute of Molecular Medicine, RWTH Aachen). Sncatm1.1Kluk/J (SncaWT/GFP) were obtained from K. Luk (Perelman School of Medicine, University of Philadelphia). Cx3cr1CreERT2.Tgfb1LoxP animals were obtained from M. Greter (University of Zurich). Different strains were bred in the same location to harmonize environmental factors. All animals were housed under temperature-controlled (temperature, 23.1 °C; humidity, 30–60%) and pathogen-free conditions with 12 h light–12 h dark cycle with an ad libitum supply of food and water. Both male and female age-matched mice were used in this study: WT, VHD, SncaWT/GFP. Both male and female 3KL mice were used. Animals of 3–4 months were used for ME injection experiments.

Human tissue samples

All tissue samples were donated with the full, informed consent. Accompanying clinical and demographic data of all cases used in this study were stored electronically in compliance with the 1998 Data Protection Act. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the NHS Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with the Human Tissue Authority’s code of practice and standards under licence number 12198, with an approved material transfer agreement. Consent has been obtained for sharing of individual-level data. Use of Translational Pathology Core Laboratory-derived human tissues was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board, which waived the informed consent requirement for specimens acquired from the Translational Pathology and Core Laboratory (TPCL) (IRB 11-002504). Specimens were deidentified and age was provided as a 5-year age range.

Tamoxifen treatment

Cx3cr1CreERT2.Tgfb1LoxP and littermate control mice were orally gavaged 3 times (every other day) with 5 mg of tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich T5648) dissolved in corn oil at around 6 weeks of age.

Tissue isolation for histology

Mice were deeply anaesthetized using pentobarbital and were transcardially perfused with 15 ml of ice-cold filtered PBS (Gibco) followed by 15 ml of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (ThermoFisher). To obtain tissue from the ME, the small intestine was isolated, stored in ice-cold PBS and cut open longitudinally. Ice-cold PBS was used to clean the tissue from luminal debris. The tissue was stretched on a Sylgard plate, and the ME was carefully peeled off using surgical tools. Isolated ME was further fixed in ice-cold 4% PFA for 20 min and preserved at −20 °C in cryoprotectant solution (10% sucrose, ethylene glycol) until stained. From the lamina propria (cross-sections), 2-cm long pieces of small intestine were isolated and luminal contents were gently flushed with ice-cold PBS using a syringe. The tissue was further fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight and excess PFA was washed with 3 × 10 min in ice-cold PBS. The tissue was dehydrated using 30% sucrose solution in PBS and frozen vertically in embedding moulds (Epredia) with optimal cutting temperature medium (Sakura) before cryo-sectioning. Sections of 20–25 μm were mounted on microscopy slides (Epredia) until staining. The brain was isolated from the skull and was further fixed, frozen and sectioned as described for cross-sections above. Sections were preserved at −20 °C in cryoprotectant solution until stained. To obtain whole mounts of dura mater, the skull cap containing the dura mater was removed from the mouse skull and stored fixed in ice-cold 4% PFA at 4 °C for 2 h. After fixation, the dura mater was carefully removed.

Tissue isolation for FACS and cell sorting

Mice were anaesthetized using pentobarbital and were transcardially perfused with 15 ml of ice-cold filtered PBS. Collected tissues were stored in ice-cold Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (RPMI-1640) (Gibco) completed with 5% FBS (Gibco) and 20 mM HEPES (Gibco). To obtain single-cell suspensions from the ME, peeled ME was cut in 1–2-mm pieces and digested with 2 mg ml−1 Collagenase type IV and 0.8 mg ml−1 dispase in RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with 2% HEPES (Gibco), 2% FBS (Gibco) and 50 μg ml−1 DNase for 1 h at 37 °C with continuous agitation. The single-cell suspensions were then homogenized with a potter grinder and strained through 70-μm cell strainers (BD Falcon). From the lamina propria, the remaining tissue following isolation of the ME, containing the lamina propria and submucosa layers, was washed with ice-cold Hank’s buffered saline solution (Gibco) supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) and 20 mM HEPES for 8 min. Single-cell suspensions of lamina propria were prepared by digestion with 0.85 mg ml−1 Collagenase Type V (Sigma-Aldrich) in MEMα (Lonza) supplemented with 2% HEPES, β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco) and DNase for 30 min at 37 °C with continuous agitation. For the brain and dura, brains were quickly isolated from the skull, and brainstem was dissected from the rest of the brain tissue on ice using chilled instruments. The dorsal part of the skull was carefully removed, and meningeal dura mater was peeled off of the skull cap. The tissues were finely chopped using chilled razorblades and transferred to tubes containing ice-cold RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 20 mM HEPES medium. Single-cell suspensions from brainstem were prepared using the Dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue chunks were pelleted by centrifugation at 300g for 2 min at 4 °C followed by medium removal and resuspension in a mix of buffer Z with enzymes A, P and Y. For digestion of meningeal dura mater, chopped tissue was resuspended in 0.5 mg ml−1 Collagenase P, 0.8 mg ml−1 Dispase II and 250 U ml−1 DNase1 and digested for 30 min. Single-cell suspensions from all tissues were then blocked with rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 antibodies (BD Biosciences) used at the recommended dilution for 12 min before incubation with primary antibodies diluted at recommended dilutions (Supplementary Table 3) in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, 0.78 mM EDTA) containing Fc block for 20 min at 4 °C. Dead cells were excluded using Live/Dead near-infrared dye staining (Invitrogen) diluted in PBS or 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Precision Count Beads (BioLegend) were used for absolute cell counting and analysed using the following formula: absolute cell count (cells per μm) = cell count/beads count × bead concentration. Flow cytometry data were analysed using FACSDiva software (v.4.0) and FlowJo software (Treestar).

Cell sorting was performed on a BD Aria III (BD Biosciences). For scRNA-seq (Fig. 4) and proteomics (Fig. 1), live CX3CR1hiCD11b+CD11c− ME-Macs and CD3+ cells (Extended Data Fig. 6a) were sorted in DMEM supplemented with 30% FBS and resuspended in PBS with 0.04% BSA.

Immunofluorescence

For free-floating sections, fixed ME or brain sections were permeabilized with 0.5% (ME) or 0.3% (brain) Triton X-100 at room temperature for 1 h followed by blocking with blocking buffer (5% donkey or goat serum (Abcam) and 0.5% or 0.3% Triton X-100 (ThermoFisher Scientific)) at room temperature for 1 h. Primary antibodies diluted at their recommended concentrations (Supplementary Table 3) in blocking buffer were added and the tissue was incubated at 4 °C overnight. Following 4 15-min PBS washes, the tissue was incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 2 h at room temperature and was washed again with PBS. Secondary antibody aliquots were centrifuged at 15,000g for 15 min before dilution in blocking buffer. Tissue was incubated for 5 min with DAPI (Roche) before being mounted on Prolong Gold Antifade Mounting Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). For on-slide staining, for the gut cross-sections, slides were washed in PBS to remove excess optimal cutting temperature medium before permeabilizing with 0.3% Triton and blocking with 5% goat or donkey serum for 15 min. For dura mater whole-mount images, sections were washed 2 times with PBS and blocked for 1.5 h at room temperature with 10% normal donkey serum (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS containing 0.3% Triton (Sigma-Aldrich) (PBS-T). Subsequently, the sections were stained with primary antibodies in 3% normal donkey serum/PBS-T (overnight, 4 °C). The following day, the samples were washed three times with PBS-T and once with PBS. The tissues were then stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich)/PBS solution for 30 min at room temperature and washed twice with PBS. Finally, the sections were mounted using Mowiol 4-88 (Polysciences Inc.) mounting solution (prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions) and stored at 4 °C. Dura mater whole mounts were imaged using a Phenoimager (Akoya Biosciences), or Nikon SoRa Spinning Disk Confocal using a ×10/×20 objective for large overview images and ×40/×60 objective for zoom-ins, all other tissues were analysed using a LSM800 (Zeiss), a LSM980 or Leica Stellaris STED microscope using a ×100 1.4 numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion Plan-Apochromat objective. All images were processed and analysed with Fiji (National Institutes of Health, NIH) and QuPath51. For T cell quantification (Figs. 3–5), we analysed 1–2 regions of interest (ROIs) (159.72 µm × 159.72 µm) per 4–5 adjacent ganglia in the duodenum, with data represented per ROI. Glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive myenteric glial cells were 3D-reconstructed using Imaris software (Bitplane), and their volume was calculated following background subtraction. For each mouse, four ROIs were analysed per ganglion. HuC/D+ neurons were quantified in two adjacent ganglia within the duodenum, with a ganglion defined as a cohesive aggregate of HuC/D-positive cells. Extraganglionic cells were excluded from the analysis.

Single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) (RNAscope) and smFISH combined with IHC

To detect single RNA molecules, the RNA probe for Tgfb1 (407751) as well as the RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Detection Reagents v2 (323110) kit were purchased from ACD BioTechne. ME tissue was cryosectioned at 20 μm and was collected on Superfrost Plus Gold Slides (ThermoFisher K5800AMNZ72) and dried at room temperature overnight. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the standard IHC protocol as described above was used.

Brain IHC

Free-floating 15-μm or 25-μm (for brainstem and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus) or 30-μm (SNpc) serial coronal sections were cut with a Leica CM1860 cryostat. The tissue was then treated with 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min. For staining with mouse anti-s129p antibodies, the samples were then incubated in M.O.M. blocking solution from mouse-on-mouse Elite Peroxidase Kit (Vector laboratories, PK-2200) prepared according to the manufacturer’s instruction for 1.5 h. The tissue was then blocked for another 5 min in M.O.M. diluent from the kit. Then, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies against s129p αS (1:10 000; BioLegend, clone P-syn/81A, 825701) for 12 h at 4 °C. The following day, the sections were treated with M.O.M. Biotinylated Anti-Mouse IgG Reagent from M.O.M. Elite Peroxidase Kit (PK-2200) prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 1 h at room temperature, and subsequently transferred into ABC solution (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) for 10 min at room temperature, and visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (DAB Substrate Kit, Vector Laboratories). Sections were then transferred onto the glass slides, air dried, sequentially dehydrated in PBS, 70%, 100% ethanol and 100% xylene, and mounted. The images were taken on an Axioscope 5 microscope (Zeiss). For staining with rabbit anti-s129p antibodies, the free-floating sections were treated with 0.3% triton for 30 min, 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min and blocked in 20% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.3% triton for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were then incubated with primary antibodies against s129p αS (1:20 000; Abcam, EP1536Y) for 12 h at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:200, Vector, Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG Antibody (H+L), Biotinylated, BA-1000-1.5) for 1 h at room temperature, subsequently transferred into ABC solution (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, PK-6100) for 45 min at room temperature and visualized with DAB (DAB Substrate Kit, Vector Laboratories).

s129p αS analysis

Fiji (NIH) was used to measure the total area of s129p αS signal in the total myenteric plexus and brainstem.

Myenteric plexus

Individual channels were first Z-projected and background-subtracted (10-pixel rolling ball radius). Next, threshold channels were empirically determined and then consistently applied to each channel for all subjects. For quantifying s129p, the Analyze Particles tool in ImageJ was used to quantify the total area of s129p (per myenteric ganglia or calculated per mm2). For the brainstem (for immunofluorescence), Z-stacks were taken of the entire tissue thickness within the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus at 1-μm Z-step increments. Images were analysed in Fiji (NIH), in which individual channels were first Z-projected and thresholded empirically and a median filter of 0.5 pixels was applied to determine only punctate staining of total and s129p αS. This was consistently applied to each channel for all subjects. ROIs were drawn around choline acetyltransferase-positive cells with the freehand selections tool. The Analyze Particles tool in Fiji was used to quantify the total number of puncta and the percentage of punctate staining within each choline acetyltransferase-positive cell by applying ROIs to the corresponding total and s129p αS channels. For the brainstem (for DAB), first, colour deconvolution with H DAB vectors was used. Then, the background was subtracted with a rolling ball radius of 50 pixels from the images, followed by adjusting the threshold to measure the fibrillar inclusions of s129p αS. Total signal area was measured for each image, and the data were normalized to the average of the control group in each staining batch. Alternatively, the optical density of the DAB signal was measured in Fiji by first calibrating the software according to the ImageJ User guide. The optical density of individual cell bodies was then measured and the background optical density was subtracted. Mean values for each mouse were then calculated.

SNpc

Z-stacks were taken of the entire tissue thickness within the SNpc at 1-μm Z-step increments. Images were analysed in Fiji (NIH), where channels were split, the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) channel was Z-projected and ROIs were drawn around TH+ cells as well as at least one ROI to measure background fluorescence. These ROIs were applied to the total and s129p αS channels and area, mean fluorescence and integrated density were measured for each cell at each plane of the Z-stack. Corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) for each TH+ cell was determined with the following equation: CTCF = integrated density − (area of selected cell × mean fluorescence of background readings). For SNpc s129p αS analysis, data were normalized to total αS and all data were then normalized to the mean of the NHC-αS group value.

TH and Nissl IHC

For TH IHC, brains were sagittally hemisected at the midline following removal of the hindbrain. The left hemisects were embedded in 10% sucrose, 0.5% glutaraldehyde in chicken egg yolk. The sample was allowed to polymerize for 5 min before being stored at −80 °C until sectioning. Embedded brains were sectioned into 30-μm slices using a Leica CM1860 cryostat and stored in cryoprotection solution at −20 °C until used for staining. All staining was performed in free-floating baskets (made in-house). Free-floating sections were washed once in PBS pH 7.5 for 5 min at room temperature on a horizontal rocker. Sections were then blocked in 5% BSA + 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Following 3 × 5 min wash in PBS, sections were incubated in anti-TH antibody (Immunostar 22941) diluted 1:1,000 in 2% BSA + 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for roughly 16 h at 4 °C. Following 3 × 5-min washes in PBS, sections were incubated in biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Avidin-biotin complex elite kit (ABC, Vector labs PK-6100) (1:50 in PBS) was prepared 30 min before use according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were then washed 3× for 5 min in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in ABC. Following a final 3 × 5-min wash in PBS, sections were incubated for 10 min in DAB solution (1 tablet Sigma D4418-50 set, 15 ml of PBS + 4.5 μl of H2O2). Sections were then washed once in PBS (5 min) and once in dH2O before being mounted onto slides and dried for roughly 30 min at 37 °C, and then covered with a glass coverslip with a polyvinyl alcohol-based mounting media (made in-house). All counting was performed blinded for treatment type and images were taken using a ×20 objective on a Leica Mica microscope acquiring z-stacks with a 0.7 μm z-step size. Stacked image tiles were loaded into StereoInvestigator desktop (MBF Bioscience). Stereological quantification was performed using the optical fractionator method from StereoInvestigator, analysing every sixth 30-μm coronal section serially for the SNpc and VTA ROIs. Using a counting frame of 50 × 50 μm snapped to 1-μm increments and a systematic random sampling grid size of 100 × 100 μm, TH+ cells were quantified unbiasedly52,53.

For Nissl staining, mounted sections containing SNpc and VTA used in the TH+ cell body quantifications were Nissl stained on top using a cresyl violet acetate-based solution to stain Nissl bodies (nucleoli and rough ER) purple. Slides were washed for 5 min in dH2O and then submerged in Nissl staining solution (4.5 g cresyl violet acetate, 45 ml of 100% ethanol, 450 ml of distilled water) for 8 min before destaining for 10 s in 2% acetic acid in ethanol, 30 s in 100% ethanol and 1 min in 100% ethanol. Sections were cleared in xylene for 10–15 min, before mounting with DPX mounting media (Cellpath SEA-1304-00A) and glass coverslips. TH+ neurons and Nissl+ neurons only (not glial cells) were quantified by unbiased stereology using the same parameters as the TH+ cell body quantifications53,54. The Nissl stain is most intense in nucleoli and in the rough endoplasmic reticulum of neurons and less in glia cells, enabling differentiation on the basis of staining patterns.

Nanostring DSP

Here, 5-μm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections of the myenteric plexus were deparaffinized and incubated with antibodies against bIII-tubulin to select myenteric ganglia as segmented ROI, according to the manufacturer’s instructions and ref. 55. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Each ROI was manually drawn around myenteric ganglia in the myenteric plexus (geometric segments), encompassing both neurons and glial cells, resulting in a total of 2–3 analysed ROIs per slide. Each slide was incubated with an antibody panel conjugated to a unique UV-photocleavable oligonucleotide tag. Selected ROIs were individually illuminated with UV light using NanoString’s GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler System (NanoString Technologies). Cleaved oligonucleotides were collected in 96-well plates and optical barcodes were analysed using the NanoString nCounter system. Obtained digital counts were normalized for signal-to-noise ratio using Rat IgG2b and Rabbit IgG. Internal housekeeping proteins included Histone H3, S6 and GAPDH.

TCR sequencing and analysis

RNA extracted was extracted from tissue samples and the TCR α and β genes were sequenced using an established quantitative sequencing pipeline, which uses unique molecular barcodes to correct for PCR bias, and sequencing errors56,57. The fastq files were processed and annotated using the in-house open-source computational pipeline Decombinator V5 (ref. 58). Plots were prepared using Python v.3.12.4, Plotly and Scipy. The NHC-αS- and PD-αS-injected groups were compared using a Bonferroni-adjusted unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. The Jaccard index is defined as

where A and B are each a set of clonotypes in a tissue. To compute the expanded index, let c(σ) be the count of clonotype σ transcripts in the sample it is found in, and EA be the expanded subset of A such that

Then the expanded index is computed by

Mass spectrometry on sorted ME-Macs

Protein lysates from sorted duodenal ME-Macs were digested using the single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample-preparation method59. Samples were processed in accordance with the published methodology. Briefly, samples were reduced and alkylated using tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine and iodoacetamide, respectively. Alkylated proteins were then bound to the Sera-Mag SpeedBeads (ThermoFisher Scientific) by raising the organic solvent content of the buffer to above 70%. Proteins could then be washed using ethanol and acetonitrile before digestion within the same sample tube to reduce protein loss. Proteins were digested through the addition of 100 ng of Trypsin/Lys-C mix (Pierce) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and leaving it at 37 °C at 300g overnight. Digested peptides were cleaned by binding them to the beads by means of increasing the organic solvent content of the buffer to above 95%. Samples were washed using 100% acetonitrile before being eluted from the beads using 2% DMSO. Peptide samples were then acidified to a final concentration of 0.1% Formic acid before injection onto the mass spectrometer. Acidified peptide samples were analysed on a Bruker TIMS-TOF Pro 2 using an EvoSep One. Samples were prepared onto an EvoTip in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were loaded onto the mass spectrometer using the ‘20 samples per day’ HPLC method provided by EvoSep using 100% water as a buffer A and 100% Acetonitrile as buffer B. The samples were acquired in data-independent acquisition mode with trapped ion mobility spectrometry on. Resultant data files were searched using DIA-NN v.1.8 (ref. 60). Search was performed against the UniProt SwissProt Mouse database in direct search mode. The double-pass neural network classifier was used and protein inference was using the protein IDs from the FASTA file. Precursor ion generation for the library used the default settings with a precursor false discovery rate at 1%. Mass accuracy and MS1 accuracy were set at 10 ppm each and the match between runs setting was enabled. Differential analysis data were analysed and visualized using CURTAIN v.2.0 (ref. 61).

Whole gastrointestinal transit function

An amount of 6% carmine red dye containing 1% methylcellulose was administered by oral gavage in 3-month-old 3KL mice or at 1 month and 3 months post-ME injection to determine the total gastrointestinal transit time. This parameter represents the time required for the mice to expel faeces containing the carmine red dye, starting from the moment of oral gavage.

Directed depletion of ME-Macs

Depletion of ME-Macs was carried out using a published protocol adapted to our purpose9. Mice were injected with 15 µg g−1 αCSF1R (clone AFS98, Bio XCell) versus IgG2a control (clone 2A3, Bio XCell) into the ME, 24 h before injection with NHC-αS versus PD-αS. Mice were orally gavaged with 15 µg αCCR2 (MC21, kindly provided by M. Mack, Universität Regensburg) daily for 7 days after AFS98 treatment to restrain ME-Mac replenishment.

Fingolimod treatment

T cell egression was targeted by oral administration of fingolimod (FTY720, Cambridge Biosciences) at a dose of 0.5 mg kg−1 through gavage on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 following PD-αS treatment. Fingolimod was dissolved in ethanol (2 mg ml−1) and saline. Saline containing 2 mg ml−1 ethanol was used as vehicle control.

Quantification of s129p αS engulfment

Engulfment analysis was performed as previously described but adapted to ME62. Mouse ME was immunostained with MHCII, LAMP1 and s129p αS, and human ME was immunostained with CD209 (ref. 63), LAMP1 and 2F12. Two regions and 3–6 ROIs were acquired for each mouse and human sample, respectively, on a ×63 1.4 NA objective Zeiss 800 microscope. For mouse, 60–80 z-stack planes were taken with 0.27-μm spacing and raw images were processed in Imaris (Bitplane) for analysis, after background subtractions. A mask was applied in MHCII+ LAMP1+ reconstructed lysosomes for s129p αS, and the percentage engulfment of s129p αS within lysosomes was calculated using the following formula: volume of engulfed material (s129p or 2F12 within LAMP1)/total ME-Mac volume × 100.

Sequential extraction of insoluble fraction from human brain

Sequential extraction from human brain was performed according to ref. 24. Briefly, 0.5 mg of brain tissue was homogenized in high salt (HI) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 750 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, pH 7.40) containing protease inhibitors. After ultracentrifugation at 100,000g for 30 min at 4 °C, supernatant was removed and fresh HI buffer added. The same steps were subsequently repeated with HI buffer containing 1% Triton, HI buffer with 1% Triton and 30% sucrose, HI buffer with 1% sarkosyl and finally in PBS to resuspend the sarkosyl-insoluble fraction of the brain homogenate enriched in aggregated αS. In the absence of pathology, the sample is expected to contain minimal random contaminants, with samples showing comparable total αS levels between disease and NHC groups64. Postmortem brain samples used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table 1b.

αS SAA

Flash-frozen PD brain tissue (500 µg, frontal cortex, Braak VI, absent copathology) was homogenized and subjected to serial extraction as described earlier. For the SAA reaction to amplify and monitor αS aggregates, 10 μl of brain-derived seed was incubated with recombinant monomeric αS at 42 °C in a BMG FLUOstar Omega plate reader to amplify amyloid αS by incorporating monomeric αS into the growing aggregate22. Before each SAA experiment, lyophilized monomeric protein was dissolved in 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8), filtered using a 0.22-mm filter and the concentration of recombinant protein was measured by use of absorbance at 280 nm using a Nanodrop One spectrophotometer. Brain-derived insoluble protein was tip-sonicated for 30 s (1 s off, 1 s on) at 30% of amplitude and added to a 96-well plate with 230 mM NaCl, 0.4 mg ml−1 αS and a 3-mm glass bead (Millipore Sigma, no. 1040150500). Repeated shaking (1 min incubation, 1 min double-orbital shaking at 400 rpm) disrupts the aggregates to produce an expanded population of converting units. The amyloid dye thioflavin T was used in adjacent wells to monitor the increase in fibrillar content through fluorescence readings at 480 nm every 30 min until the signal plateaued towards the end of the amplification interval of 4 days. The lag time of each sample was defined as the time at which the average, background corrected thioflavin T fluorescence of the sample reached 5% of its own maximum fluorescence. For SAA on isolated ME-Macs and neurons, single-cell suspensions were isolated from the ME using the magnetic-activated cell sorting method (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-097-142). ME tissues were first homogenized as described earlier and centrifuged at 400g for 7 min. The resulting cell suspension was incubated with a CD11b antibody (Miltenyi Biotec) for 30 min at 4 °C to label CD11b+ cells. The suspension was then passed through a magnetic-activated cell sorting magnetic column, and the flow-through containing CD11b− cells was collected for subsequent neuronal isolation. For the isolation of enteric neurons, CD11b− cells were processed using the Adult Neuron Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, catalogue no. 130-126-602). Briefly, cells were incubated with the Adult Non-Neuronal Cell Biotin-Antibody for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 400g for 7 min. The pellet was incubated with anti-biotin microbeads for 10 min and subsequently applied to a magnetic-activated cell sorting magnetic column. The flow-through from this step represented the enriched enteric neuronal fraction. Isolated ME-Macs and enteric neurons were then lysed to obtain protein extracts. Tip sonication was performed for 30 s (1 s off, 1 s on) at 30% amplitude to ensure efficient lysis. Lysed cells were subjected to SAA as described above.

Recombinant αS expression and purification

Briefly, plasmid pET21a-SNCA was expressed in BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli. After cell lysis, αS was purified by use of ion exchange chromatography (5 ml HiTrap Q HP columns, GE Life Sciences, 17516301) and size exclusion chromatography (13 ml of HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR, GE Life Sciences) using the ÄKTAprime plus fast protein liquid chromatography system and subsequently lyophilized in protein low binding tubes (Eppendorf)65.

αS ELISA

Samples were processed and analysed as described before using 2F12 (MABN1817, Merck) as a capture, SOY1 (Merck, MABN1818) as a sulfo-tagged detection antibody on an MSD enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) platform65. For sulfotag labelling of detection antibodies, 200 μl of SOY1 antibody (1.37 mg ml−1 in PBS) was incubated at room temperature for 2 h with 16 μl of 3 nmol μl−1 MSD NHS-Sulfotag reagent (150 nmol freshly suspended in 50 μl of PBS). Next, 250 μl of PBS was added to antibody solutions, concentrated using Amicon ultra filter tubes (10,000 molecular weight cut off), and brought up to 500 μl of PBS again. This was repeated five times to dilute out the tag reagent. Protein concentration was subsequently measured using BCA assay. For plate preparation, MSD Standard plates were coated with 30 µl of 200 ng filtered 2F12 (1 mg ml−1) from recently filtered batches diluted in PBS and stored overnight at 4 °C. Plates were then tapped out, blocked with 150 µl per well in 5% MSD blocker A in 0.01% PBS-T, sealed and placed on an orbital shaker for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were subsequently washed 5 times with 150 µl of PBS-T per well, samples were added in 2% SDS in PBS-T with 1% MSD blocker A, as well as recombinant αS at different concentration gradients in PBS-T with 1% MSD blocker A (0.5% NP-40) (Meso Scale Diagnostics LLC) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with orbital shaking. Plates were washed 5 times with 150 µl of 0.1% PBS-T per well before the addition of detection antibody solution: that is, 30 µl per well of 200 ng sulfo-tagged SOY1 antibody in PBS-T with 1% MSD blocker A. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with orbital shaking and protected from light. After 5 washes with PBS-T, 150 µl of 2× MSD reader buffer diluted in MilliQ water was added and the plate was read using a Meso Sector S 600.

Proteinase K digest

Sarkosyl-insoluble and SAA-amplified samples were treated with 1 µg ml−1 of proteinase K (Roche, 3115836001) at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle shaking. The digestion was stopped by adding NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, NP0007) and boiling the sample at 95 °C for 7 min. Samples were then loaded onto a Novex 16% Tricine gels (Invitrogen) for protein separation. After electrophoresis, gels were incubated in 20% ethanol for 5 min at room temperature and blotted onto iBlot 2 Nitrocellulose Regular Stacks (Invitrogen) using the iBlot 2 Dry Blotting system (Invitrogen). The membrane was rinsed in ultrapure water and incubated in 4% PFA/PBS for 30 min at room temperature. The membranes were blocked in Odyssey blocking buffer (PBS)/PBS buffer 1:1 (LI-COR) or casein buffer 0.5% (BioRad) for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-αS clone 42 (BD Biosciences). After three washes in PBS-T 0.1%, the membrane was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG F(Ab)2 conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP), Abcam) in blocking solution. Membranes were washed in PBS-T 0.1% and then the signal was detected using the Invitrogen iBright imaging system and the Luminata Crescendo Western HRP substrate (Millipore).

Endotoxin analysis of insoluble fractions