Abstract

Highly photostable red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) are invaluable for dual-color fluorescence microscopy, including super-resolution microscopy. Here we present mScarlet3‑S2, an RFP that exhibits a 29-fold improvement in photostability over its predecessor, mScarlet3, and outperforms other existing RFPs. This high photostability enables prolonged 2D and 3D imaging using both structured illumination microscopy and stimulated emission depletion microscopy. Using mScarlet3‑S2, we achieved over 150 Z-stacks in 3D STED imaging, revealing the architecture of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in detail. Key findings facilitated by mScarlet3‑S2 include nonplanar ER junctions, nuclear envelope (NE) invaginations, 3D maps of ER–NE contacts, diverse contact morphotypes (punctate, ribbon-like and branched) and polarized ER–NE junction distributions. These findings redefine our structural understanding of the ER–NE interface and demonstrate the value of mScarlet3‑S2 in revealing subcellular complexity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Widely used live-cell super-resolution (SR) imaging techniques, including stimulated emission depletion (STED)1 and structured illumination microscopy (SIM)2, have overcome the optical diffraction limit, enabling groundbreaking biological discoveries. However, in STED microscopy, high-power laser illumination—essential for depleting fluorescence in the donut-shaped area to achieve nanoscale resolution1—often accelerates photobleaching of conventional fluorescent proteins (FPs), leading to rapid signal decay and compromising long-term or three-dimensional (3D) imaging. Similarly, SIM requires repetitive acquisition of multiple patterned illumination frames, especially for 3D SIM, which necessitates 15 images per layer reconstruction, imposing stringent demands on FP photostability to maintain reconstruction fidelity. Consequently, the broader application of these techniques in live-cell imaging remains constrained by the limited availability of FPs that combine high photostability and brightness. Developing photostable FPs with high brightness is challenging, as it requires multiparameter optimization to prevent trade-offs between key properties3,4,5. Advances include blue-emitting Azurite6 and EBFP27, yellow-emitting FP mGold8 and the highly photostable green FP (GFP) StayGold—a mutant of wild-type GFP from Ceratocystis uchidae—which exhibits photostability an order of magnitude greater than existing GFPs while retaining high molecular brightness3. Monomeric StayGold9,10,11 derivatives now enable long-term SR imaging of rapid subcellular dynamics. However, red FPs (RFPs) that simultaneously achieve high photostability and brightness are currently lacking, constraining long-term, high-resolution live-cell imaging and multiplexing capabilities in state-of-the-art SR microscopy.

In this work, we used mScarlet3 as a template to develop a series of RFPs with enhanced photostability. Among them, mScarlet3-S2—the most photostable variant—exhibits 29-fold higher photostability than the template and is the RFP suitable for dual-color 3D STED. Using mScarlet3-S2, we performed the detailed mapping of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–nuclear envelope (NE) junctions near the nuclear periphery by STED. Spatial analysis revealed a nonrandom, polarized distribution of ER–NE contact sites along the nuclear membrane. SR imaging also identified ultrastructural features in perinuclear ER domains, including both planar three-way junctions and complex 3D junctional architectures. These structures suggest that ER membrane topology is diverse and enriches existing models of organelle connectivity.

Results

Evolution of photostable mScarlet3-S2 from mScarlet3

Screening photostable FPs via high-throughput methods such as flow cytometry is challenging because brightness and photostability are uncorrelated, preventing direct identification of highly photostable clones based on brightness alone. To overcome this, we developed a semi-automated system (Supplementary Fig. 1) that irradiates bacterial clones expressing RFP mutants with high-intensity light-emitting diode (LED) light and automatically compares their fluorescence intensities before and after irradiation. To address protein expression heterogeneity between colonies, expression levels were standardized using mStayGold (mSG) as an internal control. Photobleaching resistance was quantified as the ratio of the mutant’s normalized fluorescence intensity to that of mSG, measured before and after irradiation.

mScarlet variants exhibit a trade-off between brightness and photostability: mScarlet3 is the brightest RFP but lacks top-tier photostability12, while mScarlet-H, the most photostable, has lower brightness compared with mScarlet33,4. To develop an RFP with both high brightness and photostability, using mScarlet-H as a template risks compromising stability when enhancing brightness. Therefore, we chose mScarlet3 as the template for evolution, aiming to improve its photostability while maintaining sufficient brightness. We started with random mutagenesis and identified mutants with photostability surpassing mScarlet3 and approaching that of mScarlet-H. However, subsequent rounds of random mutagenesis failed to yield further improvements, promoting a switch to directed evolution. Inspired by the substantial enhancement from mutating methionine 163 to histidine in mScarlet4, we introduced the same mutation into mScarlet3. The resulting mScarlet3-M163H variant exhibited substantially improved photostability compared with mScarlet3, although only marginally better than mScarlet-H. We designated this variant as mScarlet3-M163H and proceeded with further optimization through site-directed evolution.

The decomposition of FP chromophores involves molecular oxygen, which photochemically reacts with the chromophores in their singlet or triplet excited states13. Because histidine at position 163 is critical for chromophore interaction and photostability in mScarlet-H and mScarlet3-M163H, we hypothesized that nearby amino acids—which undergo conformational changes upon illumination—could influence photostability. To test this, we conducted site-saturation mutagenesis on residues within 5 Å of M163H and screened the resulting mutants using the custom-built system to identify variants with enhanced properties.

We selected 12 sites (P63, M66, W143, S146, I161, K162, A164, L165, Y173, L174, A175 and F177) for saturation mutagenesis and found that some mutations at oxidation-prone residues such as M66, Y173 and F177 exhibited much higher photostability than mScarlet3. These promising mutants were further screened in mammalian cells using laser illumination. We fused mScarlet-H, mScarlet3 and its variants to H2B in human U-2 OS cells and evaluated photostability using wide-field (WF) microscopy and spinning disk (SD) confocal microscopy.

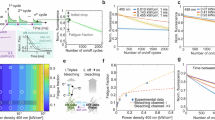

Several mutants demonstrated enhanced photostability compared with mScarlet3-M163H (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The optimal variant, designated mScarlet3-S2 (mScarlet3-M163H/M66Q, ‘S2’ indicating stable version 2), exhibited 29-, 21- and 11-fold greater photostability than mScarlet3 under WF illumination at 1.9, 5.2 and 25 W cm−2 laser power, respectively (Fig. 1a–d and Table 1). Similarly, mScarlet3-S2 showed superior photostability in fixed cells under SD confocal microscopy at varying light intensities (Extended Data Fig. 2). By contrast, mScarlet3-M163H showed 18-, 10- and 4.7-fold improvements under identical conditions. Notably, mScarlet3-S2 surpassed the photostability of mScarlet-H, by factors of 2.0 (1.9 W cm−2), 2.6 (5.2 W cm−2) and 2.8 (25 W cm−2), while mScarlet3-M163H achieved approximate 1.3-fold enhancement at both power levels.

a–c, Photostability of red-emitting mScarlet variants expressed in live U-2 OS cells under continuous WF illumination at 1.9 W cm−2 (n = 5, 4, 4 and 4 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3) (a), 5.2 W cm−2 (n = 7, 5, 6 and 6 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3) (b) and 25 W cm−2 (n = 4, 4, 4 and 4 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3) (c), respectively. Fluorescence intensity at each time point was normalized to the initial value and plotted as intensity versus time. d, The decay time constant of FPs versus WF illumination power. e,f, Absorbance, excitation and emission spectra of mScarlet3-S2 (e) and mScarlet3-M163H (f). g, pH titration curves of mScarlet variants, n = 3 biological replicates. h, Fluorescence maturation kinetics of mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3 in solution at 37 °C. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 biological replicates. i,j, Cellular brightness of mScarlet3 variants in mammalian cells; U-2 OS cells were transfected with mTurquoise2-P2A-RFP plasmids, and all cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h after transfection: the distribution of brightness (no gating was used, and all cells were collected) (i); the red-to-cyan fluorescence intensity ratio for each cell was statistically analyzed to assess the relative brightness of the mScarlet3 variants (j). n = 3,247, 3,763, 3,838 and 3,788 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3, respectively. For the box-and-whisker plots, the center line represents the median, the box spans the interquartile range (IQR; 25th to 75th percentiles) and whiskers extend to 1.5× IQR. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Sample sizes (n) are indicated above each group. k, Integral plot of actual brightness over time under 5.2 W cm−2 confocal imaging, calculated using the formula \(C\left(t\right)={\sum }_{t}\hat{F}\left(t\right)\), where C is cumulative fluorescence intensity, \(\hat{{F}}\) is averaged fluorescence intensity per frame and t is time point (n = 4, 4, 4 and 4 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3). l, Confocal photobleaching of mScarlet variants under 5.2 W cm−2, with the y axis scaled to cellular brightness.

Fluorescence properties of mScarlet3-S2

We compared the fluorescence properties of mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3-M163H with mScarlet3. Excitation and emission spectra analysis showed that, while both variants had blue-shifted excitation maxima compared with the parent protein, their emission profiles remained similar (Fig. 1e,f and Table 1). We then measured molecular brightness and observed that the engineered variants performed comparably to mScarlet-H (Table 1). Intriguingly, mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H universally displayed inverse correlations between photostability and quantum yields, while extinction coefficients showed no systematic relationship with photostability (Table 1). These observations indicate a preferential trade-off between quantum yield and photostability, rather than extinction coefficient-dependent stabilization mechanisms. Both mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3-M163H exhibit broad pH stability, with apparent pKa values of 3.3 and 3.4, respectively (Fig. 1g), probably attributed to fluorophore protonation. Their chromophore maturation rates were comparable and substantially faster than that of mScarlet-H (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 3). Size-exclusion chromatography and organized smooth ER (OSER) assay14 confirmed the monomeric nature of mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3-M163H, consistent with mScarlet3 and mScarlet-H (Extended Data Fig. 3). Finally, mScarlet3-S2 effectively localized to tubulin, mitochondria, Lamin and H2B, demonstrating its suitability as a live-cell imaging probe (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Under identical imaging conditions, both mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3-M163H exhibited mean cellular brightness comparable to mScarlet-H but dimmer than mScarlet3 (Fig. 1i,j). Integrated signal intensity analysis confirmed that mScarlet3 initially produced a stronger signal owing to its superior brightness (Fig. 1k and Extended Data Fig. 5). However, mScarlet3-S2 delivered substantially more signal in later frames, benefiting from its exceptional photostability (Fig. 1k and Extended Data Fig. 5). When comparing mScarlet3-S2 with mScarlet3 under brightness-matched conditions, mScarlet3-S2 showed lower initial residual fluorescence intensity owing to its reduced brightness (Fig. 1l). However, after 109 consecutive frames, its superior stability resulted in higher residual fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1l). Intriguingly, all three proteins emitted green light in addition to red, with mScarlet3 showing the strongest green emission peak under 450-nm excitation (Extended Data Fig. 6). Two-photon spectra (Extended Data Fig. 7) also indicate that mScarlet3-S2 emits weak green light alongside strong red fluorescence. To assess potential interference with green-red dual-color imaging, we expressed mTurquoise2 with mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3, mSG or mEmerald using P2A peptides. This enabled fluorescence comparison normalized to equivalent mTurquoise2 levels. Flow cytometry revealed substantially lower green emission from mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3 versus mSG/mEmerald (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Confocal imaging confirmed that mScarlet3-S2 pairs effectively with mSG/mEmerald for dual-color imaging (Extended Data Fig. 8b). We also tested photochromism under alternating blue and green excitation and found that both mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3 are nonphotochromic, in contrast to TagRFP-T (Extended Data Fig. 9).

mScarlet3-S2 enables 2D and 3D STED imaging

We imaged F-actin structures in U-2 OS cells labeled with mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet-H using standard confocal and STED microscopy. For STED imaging, we used a 775-nm laser (190 mW) for emission depletion and a 561-nm pulsed diode laser for excitation. Under identical STED conditions, mScarlet3-S2 retained 26% of its original fluorescence intensity, resolving abundant actin structures with significantly improved clarity (Fig. 2a,b). By contrast, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H retained only 4% and 2% of their intensity, respectively, resulting in the loss of actin structures owing to their lower photostability (Fig. 2a,b). To quantify spatial resolution, we calculated actin cross-sections (Fig. 2a) and fit them with Gaussian distributions to determine the full width at half maximum (FWHM). The actin tip showed a FWHM of ~316 nm in the confocal image and ~53 nm in the STED image (Fig. 2c).

Actin structures in U-2 OS cells were labeled with Lifeact (an actin-binding peptide) fused to FPs. Cells were fixed 24 h after transfection. a, Confocal (left and right) and STED (middle) images of actin structure imaged with mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet-H, respectively. The STED images (middle column) are magnified views of the boxed regions in the confocal images. The right column shows confocal images after STED imaging. Scale bar, 5 μm. b, Ratio of averaged fluorescence intensity in boxed areas after STED imaging (right column of a) versus before STED (left column of a). For each FP, five images were analyzed. Individual dots represent independent measurements derived from two independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test; **P < 0.01 (P = 0.00185), ****P < 0.0001 (P = 4.19 × 10−9). c, FWHM measurements of actin filaments of confocal (Conf.) and STED images (arrows, a, top row). d, Color-coded 3D distributions (XY and YZ views) of ER labeled by mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet-H in U-2 OS cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, Stacked bar chart of the accumulated fluorescence intensity of whole-stack scanning. f, A 3D reconstruction of the entire ER in U-2 OS cells labeled with sec61β-mScarlet3-S2. g, Structures of sec61β-mScarlet3-S2-labeled invagination reconstructed by Imaris software. The arrowhead and arrows indicate structures resembling NR and NR-like channels. h, XZ view (11.4 µm y-slice) showing NR-like intranuclear channels in confocal (top) and STED (bottom) modes. The hollow arrowhead indicates the NF, while the solid arrowhead and solid arrow denote the NR and NR channels, respectively.

Building on promising 2D STED results, we evaluated mScarlet3-S2 for 3D STED imaging. Previously, 3D STED Z-stacks with FPs were challenging owing to limited photobleaching resistance and cumulative photobleaching. We labeled the ER with mScarlet3-S2, using mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H as reference RFPs. The 3D STED Z-stacks were acquired on a commercial instrument, with 85% of the depletion beam energy (190 mW) directed along the Z-axis. Cells expressing different RFPs were scanned with a 50-nm Z-step. Remarkably, mScarlet3-S2 enabled 3D STED imaging, allowing over 110 Z-frames for the complete 3D reconstruction of the ER around the nucleus (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Video 1), as well as fine-scale ER distribution throughout the whole cell (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Video 2). By contrast, under the same conditions, the fluorescence signal from mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H diminished rapidly with increasing Z-scan layers (Fig. 2d,e), dropping too low for STED imaging by the tenth and second Z-stack, respectively (Supplementary Videos 3 and 4). Using mScarlet3-S2 labeling combined with 3D STED microscopy, we resolved intricate cave-like architectures formed by invaginated ER (Fig. 2g). These structures include vertically oriented, stalactite-like ER invaginations spanning the nuclear lumen, characterized by a pronounced hourglass morphology: flared, trumpet-like termini connected by a constricted central tubule (Fig. 2g). Clustered invaginations frequently coalesced into branched, tree trunk-like assemblies (Fig. 2g). In addition, basal nuclear membrane protrusions resembling upward-jutting rock formations were observed (Fig. 2g). Leveraging the superior Z-axis resolution of 3D STED, we further identified distinct Sec61β-labeled ER-derived invaginations through the NE, including structures such as nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR)15, NE folds (NF) and hollow, hourglass-shaped NR channels resembling stalactites (Fig. 2h). These ultrastructural details, unresolved by conventional confocal imaging (Fig. 2h), highlight mScarlet3-S2’s capacity to delineate complex ER–nuclear membrane interactions at nanoscale resolution by 3D STED.

mScarlet3-S2 enables dual-color 3D STED

Dual-color 3D STED imaging presents formidable challenges, requiring two fluorescent molecules with distinct emission wavelengths, high photostability, brightness and efficient depletion at the same wavelength. These demands are intensified as each molecule undergoes two depletion cycles. So far, no FPs have been reported for dual-color 3D STED imaging. Leveraging mScarlet3-S2’s performance in 3D STED, we explored its potential for dual-color 3D STED imaging.

The ER–NE junction is critical for nuclear membrane integrity, lipid synthesis, protein translocation and ER–nucleus communication16. However, its structural and organizational details remain poorly characterized, primarily owing to the lack of 3D SR reconstructions of ER–NE interfaces. To address this gap and determine if invaginated ER structures result from coordinated ER and NE invagination, we performed dual-color 3D STED imaging of U-2OS cells co-expressing HaloTag-Sec61β labeled with BD626HTL17 (ER marker) and mScarlet3-S2-laminA/C (nuclear lamina marker) (parameters: 155 Z-stacks, 50 µm pinhole size, 775 nm STED beam, 50 nm Z-step). Notably, mScarlet3-S2 exhibited robust photostability during dual-color 3D STED imaging, enabling complete NE reconstruction (Fig. 3a). Examination of the entire NE and ER revealed kidney-like ellipsoid structures for the nucleus and a complex 3D architecture for the ER, featuring diverse domains such as flat cisternal regions and highly curved tubular regions (Fig. 3a). A 3D reconstruction of the NE revealed a diverse intranuclear network of NRs (Fig. 3b). Close examination showed that most invaginations involved simultaneous protrusions of the ER and nuclear lamina, which may indicate type II NR18 (Fig. 3c). Beyond single NR invaginations, we observed clusters of NRs resembling tree roots, where larger-diameter trunks (~3 μm) coexisted with smaller-diameter branches (~0.3 μm) (Fig. 3d). Occasionally, a few ER-only protrusions extended from the nuclear lamina (Fig. 3d,e). Notably, leveraging the high stability of mScarlet3-S2, we generated the 3D distribution map of ER–NE junctions on the nuclear membrane (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Video 5), identifying three morphotypes: punctate (67.9%), ribbon-like (24.6%) and branched ribbons (7.5%). Quantitative analysis revealed a polarized distribution of ER–NE junctions, with higher density at the adherent (basal) nuclear membrane than at the apical side, and no junctions detected in the NR (Fig. 3f). In the peripheral ER network, we observed abundant planar three-way junctions in either ‘T’ or ‘Y’ shapes, consistent with prior reports19, as well as two unreported structures: a non-coplanar three-way junction and a four-way junction—with three branches in the XY plane and a fourth orthogonal branch—defining a previously unrecognized 3D structural motif (Fig. 3g). These findings address key gaps in ER–NE junction architecture and reveal principles of ER topological organization.

a, A 3D STED reconstruction of the nuclear lamina (mScarlet3-S2, left) and ER (HaloTag-conjugated BD626HTL, right) in fixed U-2 OS cells. Cells were cotransfected with HaloTag-Sec61β and mScarlet3-S2-laminA/C. After 24 h, cells were incubated with 10 nM BD626HTL for 30 min at 37 °C, washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Scale bar, 5 μm. b, Imaris-reconstructed dual-color 3D image of the ER (pink) and nuclear membrane with NR channels (cyan). Scale bar, 5 μm. c, Enlarged view of the blue rectangle in b showing simultaneous invagination of the ER and nuclear lamina. Scale bar, 5 μm. d, Enlarged view of the rectangle in b revealing NR channels of varying diameters and morphologies. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, XY, XZ and YZ cross-sections of U-2 OS cells co-expressing HaloTag-Sec61β and mScarlet3-S2-laminA/C, with arrows marking ER-only protrusions. Scale bar, 5 μm. The experiment was independently repeated twice, with three technical replicates each, yielding similar results. f, Imaris-reconstructed ER–NE junctions at the top and bottom of the nucleus (left). Scale bar, 5 μm. Magnified views of ER–NE junctions (yellow boxes) displaying ribbon-like (1), branched ribbon (2) and punctate (3) morphologies (right). Area ratios of ER–NE junctions to nuclear membranes (top versus bottom) are shown in the lower right corner. Surface plots of ER and lamina were generated using Imaris software, and the top and bottom views of the rendered images were captured using the snapshot tool. The areas of ER and lamina were measured in ImageJ, and their area ratio was subsequently calculated. Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test; *P < 0.05 (P = 0.0438). Scale bar, 1 μm. g, Imaris-reconstructed of planar three-way ER junctions (top) and nonplanar three-way/four-way ER junctions (bottom). Scale bar, 1 μm. The excitation and emission wavelengths are 561 nm (excitation) and 571–630 nm (emission) for red, and 640 nm (excitation) and 650–755 nm (emission) for far red, respectively.

mScarlet3-S2 enables long-term 2D and 3D SIM imaging

We next used SIM to assess mScarlet3-S2’s photostability and long-term SR imaging performance, using mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H as reference RFPs. Time-lapse sparse deconvolution SIM20 images of Lifeact-labeled actin showed that, under identical conditions, mScarlet3-S2 exhibited significantly higher photostability than mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3 (Fig. 4). mScarlet3-S2 enabled continuous imaging of actin with consistent brightness and clearly distinguishable filaments up to frame 200, while mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H lost 58% and 66% of their signal intensity at frame 100, respectively, impairing SIM reconstruction (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Videos 6–8). The signal decay of mScarlet3 was even more severe—by frame 45, fluorescence intensity had dropped by 88.6%, making actin structures unresolvable (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Video 9). At an illumination intensity of 25 W cm−2, mScarlet3-S2 exhibited 3.7-, 4.4- and 82.7-fold higher photostability than mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3, respectively, as quantified by the half-bleaching time (t1/2) (Fig. 4c). Owing to its superior stability, the abundance and length of mScarlet3-S2-labeled actin filaments remained nearly unchanged from initial image to frame 200 (Fig. 4d,e). By contrast, mScarlet3-M163H-, mScarlet-H- and mScarlet3-labeled actin filaments were difficult to reconstruct and shortened significantly by frame 200 owing to fluorescence bleaching (Fig. 4d,e). Similarly, mScarlet3-S2 labeling maintained clear and trackable mitochondrial cristae structures even at frame 100, while mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H labeling degraded progressively by frame 50 and became indistinguishable by frame 100 (Fig. 4f,g). mScarlet3-S2 exhibited 4.0- and 4.4-fold higher photostability than mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H, respectively (Fig. 4h), as determined by the half-bleaching time ratio (Fig. 4i). Under SIM imaging conditions, no significant difference in photostability was observed between mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H (Fig. 4h,i).

a, Time-lapse SIM images of live COS-7 cells expressing Lifeact-fused mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H or mScarlet3. The experiment was independently repeated four times, with ten technical replicates each, yielding similar results. b, Photobleaching curves of the labeled actin filaments. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from four biological independent replicates. mScarlet3-S2, n = 20; mScarlet3-M163H, n = 22; mScarlet-H, n = 22; mScarlet3, n = 24. c, Half-bleaching time under conditions in b. For the box-and-whisker plots, the center line represents the median, the box spans the interquartile range (IQR; 25th to 75th percentiles) and whiskers extend to 1.5× IQR. Sample sizes (n) are indicated above each group. Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test; ****P < 0.0001 (P = 8.5 × 10−29 (mScarlet3 versus mScarlet3-S2), P = 8.52 × 10−21 (mScarlet-H versus mScarlet3-S2), P = 1.35 × 10−20 (mScarlet3-M163H versus mScarlet3-S2)). d, Normalized fluorescence density of frame 200 to frame 1. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological independent replicates, with three technical replicates each. Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test; ****P < 0.0001 (P = 1.79 × 10−20 (mScarlet3 versus mScarlet3-S2), P = 8.19 × 10−10 (mScarlet3-M163H versus mScarlet3-S2), P = 6.35 × 10−15 (mScarlet-H versus mScarlet3-S2)). e, Superplot showed quantified length of actin filaments after segmentation and skeletonization. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological independent replicates (n = 1,333, 4,239, 2,545 and 2,996 for number of actin filaments labeled by mScarlet3, mScarlet-H, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet3-S2 at frame 1, and n = 2,000, 5,850, 3,242 and 3,030 at frame 200, respectively). Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test; ****P < 0.0001 (P = 2.33 × 10−18 (mScarlet3, F1 versus F200), P = 2.88 × 10−35 (mScarlet-H, F1 versus F200), P = 4.06 × 10−10 (mScarlet3-M163H, F1 versus F200)), n.s. P = 0.79. f, Time-lapse SIM images of live COS-7 cells expressing PHB2-fused mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H. Scale bars, 2 μm. g, Intensity profile along the red lines marking mitochondrion cristae in f. h, Photobleaching curves of mitochondrial intensity in f. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological independent replicates. mScarlet3-S2, n = 25; mScarlet3-M163H, n = 22; mScarlet-H, n = 20; mScarlet3, n = 21. i, Half-bleaching time under conditions in h. For the box-and-whisker plots, the center line represents the median, the box spans the interquartile range (IQR; 25th to 75th percentiles) and whiskers extend to 1.5× IQR. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Sample sizes (n) are indicated above each group. Significance was calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test; ****P < 0.0001 (P = 1.8 × 10−21 (mScarlet-H versus mScarlet3-S2), P = 1.67 × 10−21 (mScarlet3-M163H versus mScarlet3-S2)), n.s. P = 0.22.

Furthermore, a 3D SIM image stack approximately 2 μm in thickness was captured to visualize mitochondrial cristae in fixed cells (Fig. 5a). Although each layer in the 3D SIM reconstruction requires 15 images, accelerating photobleaching of FP, the superior photostability of mScarlet3-S2 enabled imaging over 400 layers. Even after multiple imaging loops, mitochondrial cristae remained clearly resolved. Specifically, mScarlet3-S2 fluorescence intensity decreased to 50% by loop 8 (Fig. 5b), yet the highly organized, lamellar structure of cristae was accurately resolved even at loop 20 (Fig. 5c). By contrast, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H fluorescence intensity dropped to 50% by loop 4 and loop 2, respectively (Fig. 5b). Consequently, reconstruction of cristae structure was not feasible beyond loop 7 for mScarlet3-M163H and at loop 4 for mScarlet-H owing to rapid fluorescence decline (Fig. 5c). Volumetric imaging of mitochondrial cristae throughout the entire cell is shown in Fig. 5d. Cristae were well visualized in both the XY and XZ plane (Fig. 5e), even after 20 imaging loops, owing to the high photostability of mScarlet3-S2. By contrast, cristae structure could not be resolved beyond loop 9 with mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet-H labeling owing to severe photobleaching (Fig. 5e).

a, Volumetric 3D SIM imaging at 25 W cm−2 irradiance (left) and repetitive collection of 30 loops with 20 Z-stacks for each loop (right). b, Mean fluorescence intensities per cell across different loops. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. from three biological independent replicates. mScarlet3-S2, n = 17; mScarlet3-M163H, n = 9; mScarlet-H, n = 10. c, Reconstructed 3D SIM images (ninth Z-plane) of fixed COS-7 cells expressing PHB2-fused mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet-H. Scale bars, 1 μm. d, Color-coded 3D distributions of mitochondria (labeled with Tom20–mScarlet3-S2) in a fixed COS-7 cell, e, Color-coded horizontal (left) and vertical (right) sections from fixed COS-7 cells expressing PHB2-fused mScarlet3-S2 (loop 20), mScarlet3-M163H (loop 9) or mScarlet-H (loop 9). Scale bars, 10 μm (left images) and 200 nm (right images). The experiment was independently repeated three times, with ten technical replicates each, yielding similar results.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically engineered RFPs by targeting oxidation-prone residues near critical structural sites, generating a series of photostable variants. The optimized variant, mScarlet3-S2, shows a 29-fold improvement in photostability over its parent mScarlet3 under WF illumination, surpassing all existing RFPs. Compared with the previously top-performing mScarlet-H3,4, mScarlet3-S2 exhibits 4.3-fold greater photostability, 3.2-fold faster maturation and slightly higher cellular brightness (1.1-fold). Compared with its parent protein mScarlet3, mScarlet3-S2 exhibits substantially improved photostability but is much dimmer, with brightness comparable to mCherry and mScarlet-H—still sufficient for both standard and SR imaging. The reduced brightness may lower the signal-to-noise ratio when labeling very low-expression proteins. By contrast, mScarlet3 performs better with very low excitation energies or minimal imaging frames. Owing to its superior photostability, mScarlet3-S2 outperforms mScarlet3 at higher laser intensities, such as in SIM and STED microscopy. Although mScarlet3-S2 displays minimal GFP-like emission, this is compatible with dual-color imaging when paired with mSG or mEmerald under optimized blue-light excitation. Our work addresses the longstanding bottleneck in RFPs, enabling prolonged 2D/3D SIM sessions and dual-color 3D STED imaging over 150 Z-frames, thereby overcoming photobleaching limitations for 3D STED microscopy and facilitating dynamic processes tracking in live cells.

The development of RFPs is critical for advancing STED microscopy and its biological applications by overcoming technical limitations and expanding imaging capabilities. First, RFPs enable direct STED imaging of genetically labeled live specimens—including tissues, nematodes and zebrafish—without synthetic dyes. This bypasses dye penetration issues in thick samples, simplifying preparation while maintaining physiological relevance. Second, RFPs are uniquely compatible with near-infrared probes for multicolor STED imaging. Unlike GFP, which requires separate depletion lasers when paired with red or NIR dyes, RFPs can share a single depletion wavelength with NIR probes. This eliminates coaxial alignment challenges, reduces calibration complexity and avoids wavelength-switching delays. Our study demonstrates this advantage using mScarlet3-S2 paired with the HaloTag dye BD626HTL17. Finally, RFPs offer practical benefits over far-infrared emitters by remaining visible under standard stereomicroscopes. This facilitates genetic screening, allowing labeled specimens to be identified before seamless transition to STED imaging.

Dual-color 3D STED imaging with mScarlet3-S2 and BD626HTL resolves ER–NE junction spatial heterogeneity and reveals ER topological details. The discovery of three ER–NE junction morphotypes—punctate, ribbon-like and branched ribbons—suggests functional specialization, with distinct geometries possibly regulating lipid transfer, nuclear–cytoplasmic communication or membrane remodeling. The higher basal junction density may reflect polarized cellular activities such as mechanosensitive signaling or localized protein synthesis, while their absence in NE invaginations implies spatial segregation of functionally distinct membrane domains. We propose that nuclear membranes lacking ER junction stabilization are more prone to invagination. The discovery of nonplanar three- and four-way ER junctions as 3D structural motifs challenges the conventional view of ER networks as purely planar or tubular, revealing greater complexity in ER self-organization. These findings advance our understanding of ER–NE crosstalk and architecture. Future studies should address key mechanistic questions: (1) Do distinct ER–NE junction morphotypes correlate with specific molecular cargos (for example, lipids, calcium or signaling proteins) or mechanical roles? (2) What molecular drivers (for example, cytoskeletal forces and membrane curvature proteins) establish the basal–apical asymmetry in junction density, and how are four-way junctions dynamically assembled? (3) Could ER–NE junction perturbations contribute to pathologies such as nuclear envelopathies or ER stress-related diseases, and might junction morphology serve as a diagnostic biomarker? Addressing these questions will require live-cell 3D SR imaging, functional perturbations and integrative modeling to bridge molecular mechanisms with organelle-level topology.

Note that, during submission, mScarlet3-H (mScarlet3-M163H in our Article), was published21. We show that mScarlet3-S2 exhibits up to 11-fold greater photostability than mScarlet3-H (110 versus 10 Z-stacks) under STED microscopy conditions.

Methods

Plasmid construction

To construct the plasmids pRSETA-mScarlet-H and pRSETA-mScarlet3, codon-optimized sequences of mScarlet-H and mScarlet3 for mammalian expression were synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology, amplified and inserted into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of the pRSETA vector. For maturation measurements, mScarlet-H, mScarlet3, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet3-S2 sequences were amplified and cloned into the BamHI/SalI sites of pQE-30 (You Biotechnology, VT1282), generating pQE-30-mScarlet-H, pQE-30-mScarlet3, pQE-30-mScarlet3-M163H and pQE-30-mScarlet3-S2 plasmids. The H2B sequence was fused in-frame with mScarlet-H, mScarlet3, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet3-S2 and inserted into the NheI/EcoRI sites of pEGFP-N1. For the OSER assay, the mScarlet sequence in pCytERM-mScarlet22 was replaced with mScarlet-H, mScarlet3, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet3-S2. To label the cytoskeleton and NE, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet3-S2 were fused with α-tubulin or LaminA/C and cloned into the pEGFP-C1 (NheI/BglII) backbone to replace EGFP, producing pmScarlet3-M163H/mScarlet3-S2-α-Tubulin and pmScarlet3-M163H/mScarlet3-S2-LaminA/C. For mitochondria labeling, mScarlet3-M163H and mScarlet3-S2 were inserted into pMLS-mScarlet by replacing the mScarlet cDNA. For cellular brightness measurements, mTurquoise2 was synthesized, amplified and inserted into the NheI/BglII sites of pEGFP-N1 to generate pmTurquoise2. mScarlet-H, mScarlet3, mScarlet3-M163H or mScarlet3-S2 were then fused with P2A and cloned into the XhoI/SalI sites of pmTurquoise2. Restriction enzymes were purchased from NEB. The sequence of PHB2 was directly synthesized. To generate the PHB2-mScarlet3, PHB2-mScarlet3-S2, PHB2-mScarlet3-M163H and PHB2-mScarlet-H constructs, the PHB2 sequence was PCR-amplified, digested with restriction enzymes and inserted into the NheI/XhoI sites of the respective H2B-mScarlet3, H2B-mScarlet3-S2, H2B-mScarlet3-M163H and H2B-mScarlet-H vectors. The sequences of plasmids are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Screening

The mutation libraries were transformed into BL21 (DE3) competent cells (Tsingke Biotechnology), plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing 50 µg ml−1 ampicillin and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Screening was performed using a custom setup (Supplementary Fig. 1), where a high-power LED (560 nm) was positioned on one side of a stereomicroscope (Olympus MVX10) equipped with a halogen lamp (X-cite120Q, Lumin Dynamics) and a camera (5D MarkII, Canon). A guide rail driven by a stepper motor enabled automatic plate transport between the LED and the microscope. Images were captured via a filter cube (mCherry-A-OXL, Olympus) with excitation/emission filters at 562/40 nm and 641/75 nm, respectively, and the screening was automated via a controller (TC45, TOPCNC Automation Technology). Key parameters such as LED power (0–110 mW cm−2 for 560 nm), illumination time, camera exposure time and cycle number were adjustable. MATLAB software analyzed the clone properties from each image, and clones with desired traits were selected, cultured and sequenced. For eukaryotic cell screening, U-2 OS cells transfected with H2B–RFP fusions were imaged using the home-made WF microscope described below.

Cell culture and transfection

U-2 OS cells (ECACC 92022711) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 Ham (Sigma-Aldrich, D6421) with 15 mM HEPES, sodium bicarbonate, 6 mM l-glutamine (Gibco, 25030-081), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, F7524), 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco, 15140-122) at 37 °C with 5% CO2. COS-7 cells (ATCC, CRL-1651) were kindly provided by Professor Heping Cheng (Peking University) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (ThermoFisher, C11995500BT) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin. At ~80% confluency, cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin (Gibco) for passaging or transfection. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668-019) in Opti-MEM reduced-serum medium (Gibco, 31985-062) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For live imaging, cells were cultured in confocal dishes (Cellvis, D35-14-1-N) using phenol red-free medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, F7524) and maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 during imaging. For fixed cell imaging, culture medium was removed and cells were fixed for 15 min at 37 °C using prewarmed 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Electron Microscopy Sciences, 157-8), washed three times with PBS and imaged in PBS.

Protein expression and purification

A single clone of BL21 (DE3) transformed with pRSETA-RFP plasmid was inoculated into 2 ml LB medium in a 15-ml tube and cultured overnight. One milliliter of this culture was transferred to 200 ml LB in a 500-ml flask and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.8 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 16 °C for 20 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl and 50 mM NaH2PO4) with 1 mg ml−1 lysozyme, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime), then lysed by ultrasonication. Proteins were purified using Ni-NTA His-Bind resin (Qiagen), followed by gel filtration (Superdex 200, GE Healthcare), and stored in PBS (pH 7.4) for further analysis.

Spectral properties and pK a measurement

Absorbance was measured with an ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (Agilent, 8454). Excitation and emission spectra were measured on a fluorescence spectrophotometer (F7000, Hitachi), with excitation at 500 nm or 450 nm for emission and at 650 nm for excitation. Full excitation (680–1,300 nm) and emission spectra (380–800 nm) of mScarlet3-S2 under two-photon excitation were determined using Leica Stellaris DIVE. The molar extinction coefficient (EC) and quantum yield (QY) were calculated by comparing the sample with mScarlet-I3 (extinction coefficient 105,000, quantum yield 0.65) as a ref. 12. The purified FP was added to a cuvette and diluted with 1× PBS to achieve an absorbance of around 0.1 at the characteristic absorption peak. The EC of the sample protein (EC(a)) is determined by scaling the reference protein’s extinction coefficient (EC(ref)) based on the ratio of their absorption values at 280 nm and at the protein’s maximum absorption wavelength. Specifically, the absorption at 280 nm and at the maximum absorption wavelength of the sample protein are compared with those of the reference protein. EC(a) = EC(ref) × ABS280(ref) × ABSmax(a)/[ABSmax(ref) × ABS280(a)]. The quantum yield of the sample protein (QY(a)) is calculated by adjusting the reference protein’s quantum yield (QY(ref)) using the ratio of their absorbance at the excitation wavelength and the integrated emission peak areas. The absorbance at the excitation wavelength and the emission peak area for both the sample and reference protein are used to determine the quantum yield of the sample relative to the reference. QY(a) = QY(ref) × ABSex(ref) × Area(a)/[Area(ref) × ABSex(a)].

For pKa measurements, 1 µl of concentrated protein (30 mg ml−1) was added to 100 µl of pH buffer (pH 2.2–10) in 96-well clear-bottomed plates. The pKa values (pH at which fluorescence emission reaches 50% of maximum) were recorded. Buffers with pH ≤8.0 were prepared with Na2HPO4 and citric acid; buffers with pH ≥9 were made using glycine and sodium hydroxide. The maximum fluorescence values at each pH were plotted and fit to the DoseResp function to estimate the pKa using the data analysis and graphing software OriginPro 2018C.

Chromophore maturation

The in vitro protein maturation procedure was performed as previously described23, with slight modifications. Transformed Escherichia coli cells (XL1 Blue strain, pQE system) were grown overnight in LB medium with ampicillin and 2% D-glucose. Then, the cells were diluted to an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm and transferred to 50-ml tubes filled to the brim. The tubes were sealed and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C to deplete oxygen. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and the tubes were resealed to limit oxygen. Three hours later, the cells were collected by centrifugation, subjected to sonication at 4 °C. The proteins were resuspended in PBS (pH 7.4) and incubated at 37 °C for maturation. Fluorescence intensity (excitation at 550 nm, emission at 587 nm) was measured every 2 min using a Varioskan LUX system (Thermo Scientific). To obtain the fraction of immature protein, the difference between the maximum and mean fluorescence values was divided by the fluorescence increase relative to time point zero24. Intensities were plotted and fit to the ExpDec1 function to estimate maturation using OriginPro 2018C. The fraction of immature proteins was calculated by transforming the mean fluorescence of each time point into the fraction of immature protein using the following formula: 1 − (F(t) − Ft=0)/(Fmax − Ft=0).

Photochromic behavior measurement

U-2 OS cells were transfected with H2B-FPs. After 24 h, the photochromic behavior was analyzed using WF microscopy. In brief, at time zero, the cells were illuminated with a 561-nm laser. The excitation light was manually alternated between 561 nm at 8.47 W cm−2 and 488 nm at 3.95 W cm−2 or 405 nm at 2.82 W cm−2 every 2 s for multiple illumination cycles. The mean intensity was determined per cell, and the background was subtracted. The mean intensities immediately after (I2) and before (I1) 488- or 405 nm-induced switching were used to calculate the photochromic behavior. The photochromic amplitude (Ph chr) was calculated using equation (1): Ph chr = (I2 − I1)/I2 × 100%, where Ph chr is the photochromic amplitude, I1 is the mean intensity immediately before 488 or 405 nm light and I2 is the mean intensity immediately after 488 or 405 nm light.

WF imaging

The WF system used an Olympus IX83 inverted fluorescence microscope with a 100×/numerical aperture (NA) 1.49 oil objective. A 561-nm laser (Cobolt Jive 500–561 nm) was controlled by an AOTFnC-400.650-TN filter (AA Opto-Electronic), expanded via a GCO-2503 beam expander (Daheng Optics) and directed through mirrors (PF10-03-P01, Thorlabs) and a tube lens (ITL200, Thorlabs) to focus on the objective’s back focal plane. Emitted fluorescence passed through a multiband filter cube, a dichroic mirror (ZT405/488/561/640-phase R, Chroma) and an emission filter (FF01-446/523/600/647-25, Semrock), then through a high-speed filter wheel (HS-625, Finger Lakes) with a 617-73 filter, before reaching the scientific complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (sCMOS) camera (Hamamatsu Flash 4.0V2 C11440-22CU).

Laser power was measured at the objective’s focal plane using a calibrated power meter (Thorlabs PM100D). Concurrently, full-field fluorescence images were acquired to determine the illumination area. Energy density was then calculated by dividing the measured power by this area. Detailed parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Confocal imaging

Confocal dishes with glass bottoms (Cellvis, D35-20-1-N) were coated with 10 μg μl−1 fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, 11080938001) for 15 min at 37 °C. U-2 OS cells were transfected with the plasmid that labels different organelles. Twenty-four hours later, images were captured using an FV3000 confocal laser scanning microscope (EVIDENT Life Science) with a 60× oil objective lens. The images were quantified and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Detailed parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

SIM setup

The SIM system utilizes a commercial Olympus IX83 inverted fluorescence microscope with objectives (×100/1.49 oil for 2D SIM, ×100/1.7 HI oil for TIRF-SIM) and a multiband dichroic mirror (ZT405/488/561/640-phase R, Chroma) as described previously20. Laser light at 488 nm and 561 nm (Sapphire 488LP-200 and 561LP-200, Coherent) is combined and power-adjusted via acoustic optical tunable filters (AOTF, AA Opto-Electronic). The lasers are coupled to a polarization-maintaining single-mode fiber (QPMJ-3AF3S, Oz Optics) and collimated by a lens (CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda 2× NA 0.10, Nikon). Diffraction is achieved using a polarizing beam splitter, half-wave plate and spatial light modulator (SLM) (3DM-SXGA, ForthDD), with focused beams directed onto the intermediate pupil plane. A stop mask blocks zero-order and stray light, allowing only ±1 order beams to pass. A polarization rotator is used to modulate the illumination pattern. The light is then focused on the objective’s back focal plane, where fluorescence emitted by the sample passes through filters and is split by an image splitter (W-VIEW GEMINI, Hamamatsu). Finally, the fluorescence is captured by an sCMOS camera (Flash 4.0 V3, Hamamatsu). Power measurement was performed by switching to WF imaging mode. A power meter (Thorlabs) was positioned directly at the objective lens side, ensuring the probe fully covered the illumination spot. The excitation light power was set to 80%, and the measurement was recorded. Irradiance was calculated by dividing the measured power value by the imaging field area (65 μm × 65 μm).

For image reconstruction, we applied Wiener deconvolution using a North filter (30-pixel setting for frequency optimization) with a defocus elimination parameter of 0.5 for 2D SIM processing. The 3D SIM datasets required additional slice reconstruction. To enhance resolution, sparse deconvolution was then performed using MicroscopeX FINER software (v1.1.15e) with predefined parameters, including sample type specification (actin/mitochondrial cristae) and sparse regularization level (level 1). Detailed parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

STED microscopy

STED images were acquired using an Abberior Facility Line fluorescence microscope (Abberior Instruments GmbH) mounted on a motorized inverted IX83 microscope (Olympus UPlanXAPO 60×, NA 1.42). The system is equipped with a 775-nm pulsed STED laser and 561-nm and 640-nm excitation lasers.

Imaging and image processing were performed using Fiji (1.54f) and Imaris (10.2.0). All images are presented as raw data unless otherwise stated. Detailed parameters are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Oligomerization property analysis

Size-exclusion chromatography of the purified proteins (3 mg ml−1) was performed using mScarlet3 (monomer), dTomato (dimer) and StayGold (dimer) as controls. The oligomerization property of FPs were also measured with an OSER assay14. The FPs were fused to the cytoplasmic end of an ER signal-anchor membrane protein (CytERM). U-2 OS cells expressing CytERM-FP fusions were imaged by confocal microscopy (Zeiss, LSM980) and analyzed. Manual quantification was performed to count the number of cells with and without whorls.

Cellular brightness measurement

For measurement of the practical brightness of mScarlet3 variants expressed in mammalian cells, U-2 OS cells were transfected with pmTurquoise2-P2A-RFP plasmids and analyzed by flow cytometry 24 h after transfection. The ratio of the red versus the cyan fluorescence intensity of each cell was statistically analyzed to assess the relative brightness of the mScarlet3 variants.

Photostability measurement in living mammalian cells

To compare photostability, images were acquired using the custom-built WF microscope and the Nikon CSU-X1 SD microscope. The cells were imaged with a 561-nm laser at ~5.2 W cm−2, ~1.9 W cm−2 and ~25 W cm−2 at 1-s intervals. Fluorescence intensities were measured for the H2B variants using Fiji. The datapoints were normalized to the first intensity measurement.

Data analysis, statistics and reproducibility

All images were processed in Fiji (ImageJ 1.52p). Data were analyzed with Excel (2010) and plotted by OriginPro 2018C unless otherwise specified. Data were analyzed by Student’s paired t-test for two groups. All the values were shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Data were repeated with several technical and biological replicates as indicated. All data with statistical analyses were replicated across at least three biologically independent samples.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The remaining image files are available from the corresponding author upon request, as the total size of the files acquired for this study exceeds the 20 GB limit of the Figshare repository. The maps and sequences of vectors are available via the Addgene repository (pRSETA-mScarlet3-S2, no. 246871; H2B-mScarlet3-S2, no. 246872; Lifeact-mScarlet3-S2, no. 246873; mScarlet3-S2-Sec61B, no. 246874; mScarlet3-S2-LaminA/C, no. 246875). The cDNA sequence of mScarlet3-S2 has been deposited at GenBank (accession code PX508343).

References

Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19, 780–782 (1994).

Gustafsson, M. G. Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy. J. Microsc. 198, 82–87 (2000).

Hirano, M. et al. A highly photostable and bright green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1132–1142 (2022).

Bindels, D. S. et al. mScarlet: a bright monomeric red fluorescent protein for cellular imaging. Nat. Methods 14, 53–56 (2017).

Shaner, N. C. et al. Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 5, 545–551 (2008).

Mena, M. A., Treynor, T. P., Mayo, S. L. & Daugherty, P. S. Blue fluorescent proteins with enhanced brightness and photostability from a structurally targeted library. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1569–1571 (2006).

Ai, H. W., Shaner, N. C., Cheng, Z. H., Tsien, R. Y. & Campbell, R. E. Exploration of new chromophore structures leads to the identification of improved blue fluorescent proteins. Biochemistry 46, 5904–5910 (2007).

Lee, J. et al. Versatile phenotype-activated cell sorting. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb7438 (2020).

Ando, R. et al. StayGold variants for molecular fusion and membrane-targeting applications. Nat. Methods 21, 648–656 (2024).

Ivorra-Molla, E. et al. A monomeric StayGold fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 1368–1371 (2024).

Zhang, H. B. et al. Bright and stable monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from StayGold. Nat. Methods 21, 657–665 (2024).

Gadella, T. W. Jr et al. mScarlet3: a brilliant and fast-maturing red fluorescent protein. Nat. Methods 20, 541–545 (2023).

Dean, K. M. et al. High-speed multiparameter photophysical analyses of fluorophore libraries. Anal. Chem. 87, 5026–5030 (2015).

Costantini, L. M., Fossati, M., Francolini, M. & Snapp, E. L. Assessing the tendency of fluorescent proteins to oligomerize under physiologic conditions. Traffic 13, 643–649 (2012).

Echevarría, W., Leite, M. F., Guerra, M. T., Zipfel, W. R. & Nathanson, M. H. Regulation of calcium signals in the nucleus by a nucleoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 440–446 (2003).

Bragulat-Teixidor, H., Ishihara, K., Szücs, G. M. & Otsuka, S. The endoplasmic reticulum connects to the nucleus by constricted junctions that mature after mitosis. EMBO Rep. 25, 3137–3159 (2024).

Zhang, J. W. et al. A palette of bridged bicycle-strengthened fluorophores. Nat. Methods 22, 1276–1287 (2025).

Malhas, A., Goulbourne, C. & Vaux, D. J. The nucleoplasmic reticulum: form and function. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 362–373 (2011).

Lipowsky, R. et al. Elucidating the morphology of the endoplasmic reticulum: puzzles and perspectives. ACS Nano 17, 11957–11968 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Sparse deconvolution improves the resolution of live-cell super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 606–617 (2022).

Xiong, H. Y. et al. A highly stable monomeric red fluorescent protein for advanced microscopy. Nat. Methods 22, 1288–1298 (2025).

Liu, A. Y. et al. pHmScarlet is a pH-sensitive red fluorescent protein to monitor exocytosis docking and fusion steps. Nat. Commun. 12, 1413 (2021).

Pennacchietti, F. et al. Fast reversibly photoswitching red fluorescent proteins for live-cell RESOLFT nanoscopy. Nat. Methods 15, 601–604 (2018).

Balleza, E., Kim, J. M. & Cluzel, P. Systematic characterization of maturation time of fluorescent proteins in living cells. Nat. Methods 15, 47–51 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grants 2024YFC3406600 and 2022ZD0211900 to P.X. and 2022YFC3400600 to L.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 92254306, 21927813 and T2394513 to P.X. and 32227802 and 31970704 to L.Y.) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB37040301 to P.X.). We thank Y. Teng and Q. Bian (Center for Biological Imaging, Institute of Biophysics) for the support on microscopy imaging; J. Jia (Core Facility, Institute of Biophysics) for flow cytometry technical assistance; Y. Feng (Center for Biological Imaging, Institute of Biophysics) for Imaris analysis support; J. Li (Institute of Biophysics) for the support on fluorescence spectrophotometer; and Y. Fu (Center of Instrument Innovation Development and Technical Service, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for mechanical part processing. We thank J. Liu (Center of Medical and Health Analysis, Peking University Health Science Center) for the two-photon imaging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. Xu and L.Y. conceived and supervised the study. L.Y. and Y.D. engineered mScarlet3-S2 and measured its properties. W.H. built the E. coli stable-FP screening setup. K.W. and S.Z. performed SIM imaging. Y.D., and F.X. analyzed data. K.Z. cultured cells. L.Y., D.Q. and T.L. performed STED imaging. L.Y., L.C., L.P., Z.C. and P. Xia participated in the guidance of SIM and STED imaging. P. Xu and L.Y. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.Q. is an employee of Optofem Technology Limited. T.L. is an employee of Abberior Instruments Beijing Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Methods thanks Jianshu Dong, Joachim Goedhart and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Rita Strack and Nina Vogt, in collaboration with the Nature Methods team. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Sequence alignment.

Amino acid sequence alignment of mScarlet3, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet3-S1-1, mScarlet3-S1-2, mScarlet3-S1-3 and mScarlet3-S2. The mutation sites are shaded in grey.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Photostable properties of mScarlet variants with spinning disc (SD) confocal microscopy.

Fixed U-2 OS cells expressing various mScarlet variants were continuously illuminated at a, 1.9 W/cm2 (n = 4, 7, 4, 4 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3), b, 5.2 W/cm2 (n = 4, 4, 4, 4 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3), and c, 25 W/cm2 (n = 4, 4, 4, 4 for mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H and mScarlet3) respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Fluorescent intensity at different timepoints were normalized to the initial fluorescence intensity. Plotted as measured intensity versus time. d, The decay time constant of FPs versus SD illumination power.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Monomeric properties of FPs.

a, Size-exclusion chromatography of mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet3, mScarlet-H, StayGold and dTomato. b, The organized smooth endoplasmic reticulum (OSER) assay of variant FPs. Statistical analysis of the number of normal cells expressing mScarlet variant-labeled CytEMR is shown. c, Representative images of normal cells expressing mScarlet variant-labeled CytEMR, as well as abnormal cells expressing StayGold and dTomato. Scale bars, 10 μm. The experiment was independently repeated three times, with two technical replicates each, yielding similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Protein labeling and imaging using mScarlet3-S2 and mScarlet3-M163H.

Representative images of cells expressing mScarlet3-S2 or mScarlet3-M163H-labeled α-tubulin, mitochondria, Lamin, and H2B. Scale bars, 10 μm. The experiment was repeated independently three times, with two technical replicates each, yielding similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Integral plot of actual brightness over time.

Cumulative fluorescence intensity over time under a, 1.9 W/cm² and b, 25 W/cm² confocal imaging, calculated using the formula C(t)=\({\sum }_{t}\hat{F}(t)\), where C is cumulative fluorescence intensity, \(\hat{F}\) is averaged fluorescence intensity per frame, and t is time point. Sample sizes were n = 4, 7, 4, 4 (mScarlet3-S2, mScarlet3-M163H, mScarlet-H, mScarlet3) at 1.9 W/cm² and n = 4 for each variant at 25 W/cm².

Extended Data Fig. 6 Emission curves under single-photon excitation upon 450-nm illumination.

a–d, Purified protein (0.1 mg/mL) was used to analyze were used to analyze the emission spectra of mScarlet3 (a), mScarlet3-S2 (b), mScarlet3-M163H (c), and mScarlet-H (d) recorded with 450-nm excitation measured by the fluorescence spectrophotometer F7000. Protein purification was performed for three biologically independent replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Two-photon excitation and emission spectra of mScarlet3-S2.

a,b, Purified protein (0.1 mg/mL) was used to analyze a, the excitation spectrum (680-1300 nm, emission at 600 nm) and b, the emission spectrum (380-800 nm) under excitation at 920 nm (blue) and 1045 nm (red).

Extended Data Fig. 8 mScarlet3-S2 is suitable for dual-color imaging when combined with mStayGold or mEmerald.

a. Fluorescence intensity distribution of various fluorescent proteins. U-2 OS cells transfected with mTurquoise2-P2A-mScarlet3-S2, mTurquoise2-P2A-mScarlet3, mTurquoise2-P2A-mSG, or mTurquoise2-P2A-mEmerald were collected, and fluorescence intensity of all cells in the green channel versus the blue channel by flow cytometry was plotted. No gating was used, and all cells were collected. k represents the slope of the linear regression. b. Dual-color imaging of mScarlet3-S2 with green fluorescent proteins. Live U-2OS cells were co-transfected with either: H2B-mScarlet3-S2 and Tom20-Emerald, or 2×MLS-mScarlet3-S2 and H2B-mStayGold. Images were acquired using Airyscan microscopy. Scale bar: 5 μm. Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 980 with Airyscan 2. The experiment was independently repeated three times with two technical replicates each, yielding similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Photochromic behavior of RFPs in U-2 OS cells.

a–g, The cells were WF illuminated with alternating light of 561 nm and 405 nm (a–c) or 488 nm (e–g) lights for multiple illumination cycles. Boxplot of all determined photochromic amplitudes (blue arrows) of RFPs determined with 5 illumination cycles are presented in (d) and (h). d, n = 15 cells for mScarlet3-S2, n = 10 cells for mScarlet3 and n = 15 cells for TagRFP-T. h, n = 15 cells for mScarlet3-S2, n = 5 cells for mScarlet3 and n = 15 cells for TagRFP-T. For the box-and-whisker plots, the center line represents the median, the box spans the interquartile range (IQR; 25th to 75th percentiles), and whiskers extend to 1.5× IQR. Outliers are plotted as individual points. Sample sizes (n) are indicated above each group.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–3.

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2

Supplementary Table 1. Plasmid maps of key constructs. Supplementary Table 2. Summary of imaging parameters.

Supplementary Video 1

3D reconstruction of the ER labeled by mScarlet3-S2 around the nucleus

Supplementary Video 2

ER distribution throughout the whole cell

Supplementary Video 3

3D reconstruction of the ER labeled by mScarlet3-M163H around the nucleus

Supplementary Video 4

3D reconstruction of the ER labeled by mScarlet-H around the nucleus

Supplementary Video 5

ER-NE junctions on the nuclear membrane

Supplementary Video 6

Time-lapse imaging of mScarlet3-S2 labeled actin

Supplementary Video 7

Time-lapse imaging of mScarlet3-M163H labeled actin

Supplementary Video 8

Time-lapse imaging of mScarlet-H labeled actin

Supplementary Video 9

Time-lapse imaging of mScarlet3 labeled actin

Supplementary Data 1

Statistical source data of Supplementary Fig. 2.

Supplementary Data 2

Statistical source data of Supplementary Fig. 3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data of Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data of Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data of Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data of Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data of Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 2.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 6.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 7.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 8.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data of Extended Data Fig. 9.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, Y., He, W., Wang, K. et al. A highly photostable monomeric red fluorescent protein for dual-color 3D STED and time-lapse 3D SIM imaging. Nat Methods 23, 143–152 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02962-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-025-02962-2

This article is cited by

-

Year in review 2025

Nature Methods (2026)