Abstract

Cortical slow waves reflect the need for sleep, and their presence indicates a state of disconnection and homeostatic regulation. However, little is known about the neural signatures of sleep need beyond the cortex. Here we performed chronic, continuous, 48-h Neuropixels recordings in male rats to capture hippocampal activity over sleep/wake cycles. We show that hippocampal sharp waves (SPWs) and, to some extent, ripples and dentate spikes (DSs) closely reflect sleep need. Hippocampal SPWs occurred during behavioral sleep and, unlike cortical slow waves, also during quiet wake. The expression of hippocampal SPW, ripple and DS during cortical wakefulness was negatively correlated with that during subsequent cortical sleep, suggesting that these events fulfill similar homeostatic functions. Moreover, the slow-to-fast gamma ratio was always high during SPW, consistent with a switch to a partially disconnected mode. We propose that SPWs define a partially disconnected, homeostatically regulated, unitary state of the hippocampus, which we refer to as ‘hippocampal sharp wave sleep’.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All processed data needed to reproduce statistical results and figures are publicly available at https://gin.g-node.org/grahamfindlay/Findlay_et_al_2025_Nature_Neuroscience ref. 108. Access to unprocessed data is available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Code availability

All original code is available at https://github.com/grahamfindlay/Findlay_et_al_2025_Nature_Neuroscience ref. 106.

References

Campbell, S. S. & Tobler, I. Animal sleep: a review of sleep duration across phylogeny. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 8, 269–300 (1984).

Rattenborg, N. C. & Ungurean, G. The evolution and diversification of sleep. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 156–170 (2023).

Shaw, P. J., Cirelli, C., Greenspan, R. J. & Tononi, G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287, 1834–1837 (2000).

Anafi, R. C., Kayser, M. S. & Raizen, D. M. Exploring phylogeny to find the function of sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 109–116 (2019).

Brodt, S., Inostroza, M., Niethard, N. & Born, J. Sleep—a brain-state serving systems memory consolidation. Neuron 111, 1050–1075 (2023).

Cirelli, C. & Tononi, G. The why and how of sleep-dependent synaptic down-selection. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 125, 91–100 (2022).

Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Sleep and the price of plasticity: from synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron 81, 12–34 (2014).

Huber, R., Felice Ghilardi, M., Massimini, M. & Tononi, G. Local sleep and learning. Nature 430, 78–81 (2004).

Sawada, T. et al. Prefrontal synaptic regulation of homeostatic sleep pressure revealed through synaptic chemogenetics. Science 385, 1459–1465 (2024).

Bartram, J. et al. Cortical Up states induce the selective weakening of subthreshold synaptic inputs. Nat. Commun. 8, 665 (2017).

González-Rueda, A., Pedrosa, V., Feord, R. C., Clopath, C. & Paulsen, O. Activity-dependent downscaling of subthreshold synaptic inputs during slow-wave-sleep-like activity in vivo. Neuron 97, 1244–1252 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Slow-wave sleep drives sleep-dependent renormalization of synaptic AMPA receptor levels in the hypothalamus. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002768 (2024).

Mittermaier, F. X. et al. Membrane potential states gate synaptic consolidation in human neocortical tissue. Nat. Commun. 15, 10340 (2024).

Squarcio, F., Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Effects of non-rapid eye movement sleep on the cortical synaptic expression of GluA1-containing AMPA receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 60, 3961–3972 (2024).

Buzsáki, G. Hippocampal sharp wave-ripple: a cognitive biomarker for episodic memory and planning. Hippocampus 25, 1073–1188 (2015).

Norimoto, H. et al. Hippocampal ripples down-regulate synapses. Science 359, 1524–1527 (2018).

Spano, G. M. et al. Sleep deprivation by exposure to novel objects increases synapse density and axon–spine interface in the hippocampal CA1 region of adolescent mice. J. Neurosci. 39, 6613–6625 (2019).

Giri, B. et al. Sleep loss diminishes hippocampal reactivation and replay. Nature 630, 935–942 (2024).

Durán, E., Oyanedel, C. N., Niethard, N., Inostroza, M. & Born, J. Sleep stage dynamics in neocortex and hippocampus. Sleep 41, zsy060 (2018).

Vyazovskiy, V. et al. Local sleep in awake rats. Nature 472, 443–447 (2011).

Borbely, A. A., Daan, S., Wirz-Justice, A. & Deboer, T. The two-process model of sleep regulation: a reappraisal. J. Sleep Res. 25, 131–143 (2016).

Borbély, A. A. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum. Neurobiol. 1, 195–204 (1982).

Vyazovskiy, V. V. et al. Cortical firing and sleep homeostasis. Neuron 63, 865–878 (2009).

Watson, B. O., Levenstein, D., Greene, J. P., Gelinas, J. N. & Buzsáki, G. Network homeostasis and state dynamics of neocortical sleep. Neuron 90, 839–852 (2016).

Huber, R., Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Exploratory behavior, cortical BDNF expression, and sleep homeostasis. Sleep 30, 129–139 (2007).

Leemburg, S. et al. Sleep homeostasis in the rat is preserved during chronic sleep restriction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15939–15944 (2010).

Bragin, A., Jando, G., Nadasdy, Z., van Landeghem, M. & Buzsaki, G. Dentate EEG spikes and associated interneuronal population bursts in the hippocampal hilar region of the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 73, 1691–1705 (1995).

Penttonen, M., Kamondi, A., Sik, A., Acsady, L. & Buzsaki, G. Feed-forward and feed-back activation of the dentate gyrus in vivo during dentate spikes and sharp wave bursts. Hippocampus 7, 437–450 (1997).

McHugh, S. et al. Offline hippocampal reactivation during dentate spikes supports flexible memory. Neuron 112, 3768–3781 (2024).

Dijk, D. J. EEG slow waves and sleep spindles: windows on the sleeping brain. Behav. Brain Res. 69, 109–116 (1995).

Isomura, Y. et al. Integration and segregation of activity in entorhinal-hippocampal subregions by neocortical slow oscillations. Neuron 52, 871–882 (2006).

Maingret, N., Girardeau, G., Todorova, R., Goutierre, M. & Zugaro, M. Hippocampo-cortical coupling mediates memory consolidation during sleep. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 959–964 (2016).

Sirota, A., Csicsvari, J., Buhl, D. & Buzsáki, G. Communication between neocortex and hippocampus during sleep in rodents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 2065–2069 (2003).

Werth, E., Dijk, D. J., Achermann, P. & Borbely, A. A. Dynamics of the sleep EEG after an early evening nap: experimental data and simulations. Am. J. Physiol. 271, R501–R510 (1996).

Sebastian, E. R. et al. Topological analysis of sharp-wave ripple waveforms reveals input mechanisms behind feature variations. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 2171–2181 (2023).

Buzsáki, G. Hippocampal sharp waves: their origin and significance. Brain Res. 398, 242–252 (1986).

Colgin, L. L. et al. Frequency of gamma oscillations routes flow of information in the hippocampus. Nature 462, 353–357 (2009).

Aery Jones, E. A. et al. Dentate gyrus and CA3 GABAergic interneurons bidirectionally modulate signatures of internal and external drive to CA1. Cell Rep. 37, 110159 (2021).

Oliva, A., Fernández-Ruiz, A., Fermino de Oliveira, E. & Buzsáki, G. Origin of gamma frequency power during hippocampal sharp-wave ripples. Cell Rep. 25, 1693–1700 (2018).

Carr, M. F., Karlsson, M. P. & Frank, L. M. Transient slow gamma synchrony underlies hippocampal memory replay. Neuron 75, 700–713 (2012).

Vanderwolf, C. H. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 26, 407–418 (1969).

Cirelli, C. & Tononi, G. The many unknowns of partial sensory disconnection during sleep: a review of the literature. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 8, 9 (2024).

Osorio-Forero, A. et al. Noradrenergic circuit control of non-REM sleep substates. Curr. Biol. 31, 5009–5023 (2021).

De Vivo, L. et al. Ultrastructural evidence for synaptic scaling across the wake/sleep cycle. Science 355, 507–510 (2017).

Vyazovskiy, V., Cirelli, C., Pfister-Genskow, M., Faraguna, U. & Tononi, G. Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for net synaptic potentiation in wake and depression in sleep. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 200–208 (2008).

Esser, S. K., Hill, S. L. & Tononi, G. Sleep homeostasis and cortical synchronization: I. Modeling the effects of synaptic strength on sleep slow waves. Sleep 30, 1617–1630 (2007).

Olcese, U., Esser, S. K. & Tononi, G. Sleep and synaptic renormalization: a computational study. J. Neurophysiol. 104, 3476–3493 (2010).

King, C., Henze, D. A., Leinekugel, X. & Buzsáki, G. Hebbian modification of a hippocampal population pattern in the rat. J. Physiol. 521, 159–167 (1999).

Gruart, A., Munoz, M. D. & Delgado-Garcia, J. M. Involvement of the CA3–CA1 synapse in the acquisition of associative learning in behaving mice. J. Neurosci. 26, 1077–1087 (2006).

Kumar, A. Long-term potentiation at CA3–CA1 hippocampal synapses with special emphasis on aging, disease, and stress. Front. Aging Neurosci. 3, 7 (2011).

Whitlock, J. R., Heynen, A. J., Shuler, M. G. & Bear, M. F. Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science 313, 1093–1097 (2006).

Takeuchi, T. et al. Locus coeruleus and dopaminergic consolidation of everyday memory. Nature 537, 357–362 (2016).

Behrens, C. J., van den Boom, L. P., de Hoz, L., Friedman, A. & Heinemann, U. Induction of sharp wave-ripple complexes in vitro and reorganization of hippocampal networks. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1560–1567 (2005).

Buzsaki, G. Long-term changes of hippocampal sharp-waves following high frequency afferent activation. Brain Res. 300, 179–182 (1984).

Ponomarenko, A. A., Lin, J. S., Selbach, O. & Haas, H. L. Temporal pattern of hippocampal high-frequency oscillations during sleep after stimulant-evoked waking. Neuroscience 121, 759–769 (2003).

Eschenko, O., Ramadan, W., Molle, M., Born, J. & Sara, S. J. Sustained increase in hippocampal sharp-wave ripple activity during slow-wave sleep after learning. Learn. Mem. 15, 222–228 (2008).

Girardeau, G., Cei, A. & Zugaro, M. Learning-induced plasticity regulates hippocampal sharp wave-ripple drive. J. Neurosci. 34, 5176–5183 (2014).

Miyawaki, H. & Diba, K. Regulation of hippocampal firing by network oscillations during sleep. Curr. Biol. 26, 893–902 (2016).

Miyamoto, D., Marshall, W., Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Net decrease in spine-surface GluA1-containing AMPA receptors after post-learning sleep in the adult mouse cortex. Nat. Commun. 12, 2881 (2021).

Sadowski, J. H., Jones, M. W. & Mellor, J. R. Sharp-wave ripples orchestrate the induction of synaptic plasticity during reactivation of place cell firing patterns in the hippocampus. Cell Rep. 14, 1916–1929 (2016).

Findlay, G., Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. The evolving view of replay and its functions in wake and sleep. Sleep Adv. 1, zpab002 (2020).

Joo, H. R. & Frank, L. M. The hippocampal sharp wave–ripple in memory retrieval for immediate use and consolidation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 744–757 (2018).

Tang, W., Shin, J. D., Frank, L. M. & Jadhav, S. P. Hippocampal-prefrontal reactivation during learning is stronger in awake compared with sleep states. J. Neurosci. 37, 11789–11805 (2017).

Staresina, B. P., Niediek, J., Borger, V., Surges, R. & Mormann, F. How coupled slow oscillations, spindles and ripples coordinate neuronal processing and communication during human sleep. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1429–1437 (2023).

Chang, H. et al. Sleep microstructure organizes memory replay. Nature 637, 1161–1169 (2025).

Farrell, J. S., Hwaun, E., Dudok, B. & Soltesz, I. Neural and behavioural state switching during hippocampal dentate spikes. Nature 628, 590–595 (2024).

Senzai, Y. & Buzsaki, G. Physiological properties and behavioral correlates of hippocampal granule cells and mossy cells. Neuron 93, 691–704 (2017).

Buzsaki, G. et al. Nucleus basalis and thalamic control of neocortical activity in the freely moving rat. J. Neurosci. 8, 4007–4026 (1988).

Tononi, G., Boly, M. & Cirelli, C. Consciousness and sleep. Neuron 112, 1568–1594 (2024).

Frank, M. G. Sleep phylogeny. Sleep Med. Clin. 20, 19–24 (2025).

Jang, R. S., Ciliberti, D., Mankin, E. A. & Poe, G. R. Recurrent hippocampo-neocortical sleep-state divergence in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2123427119 (2022).

Magnin, M. et al. Thalamic deactivation at sleep onset precedes that of the cerebral cortex in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3829–3833 (2010).

Nobili, L. et al. Dissociated wake-like and sleep-like electro-cortical activity during sleep. Neuroimage 58, 612–619 (2011).

Bernardi, G. et al. Neural and behavioral correlates of extended training during sleep deprivation in humans: evidence for local, task-specific effects. J. Neurosci. 35, 4487–4500 (2015).

Nir, Y. et al. Selective neuronal lapses precede human cognitive lapses following sleep deprivation. Nat. Med. 23, 1474–1480 (2017).

Mascetti, G. G. Unihemispheric sleep and asymmetrical sleep: behavioral, neurophysiological, and functional perspectives. Nat. Sci. Sleep 8, 221–238 (2016).

Jun, J. J. et al. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature 551, 232–236 (2017).

Cavelli, M. L. et al. Sleep/wake changes in perturbational complexity in rats and mice. iScience 26, 106186 (2023).

Voigts, J., Newman, J. P., Wilson, M. A. & Harnett, M. T. An easy-to-assemble, robust, and lightweight drive implant for chronic tetrode recordings in freely moving animals. J. Neural Eng. 17, 026044 (2020).

De Vivo, L. et al. Loss of sleep affects the ultrastructure of pyramidal neurons in the adolescent mouse frontal cortex. Sleep 39, 861–874 (2016).

Newman, S. M., Paletz, E. M., Obermeyer, W. H. & Benca, R. M. Sleep deprivation in pigeons and rats using motion detection. Sleep 32, 1299–1312 (2009).

Putzeys, J. et al. Neuropixels data-acquisition system: a scalable platform for parallel recording of 10 000+ electrophysiological signals. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 13, 1635–1644 (2019).

Schomburg, E. W. et al. Theta phase segregation of input-specific gamma patterns in entorhinal-hippocampal networks. Neuron 84, 470–485 (2014).

Combrisson, E. et al. Visbrain: a multi-purpose GPU-accelerated open-source suite for multimodal brain data visualization. Front. Neuroinform. 13, 14 (2019).

Combrisson, E. et al. Tensorpac: an open-source Python toolbox for tensor-based phase-amplitude coupling measurement in electrophysiological brain signals. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008302 (2020).

Scheffer-Teixeira, R. et al. Theta phase modulates multiple layer-specific oscillations in the CA1 region. Cereb. Cortex 22, 2404–2414 (2012).

Kemere, C., Carr, M. F., Karlsson, M. P. & Frank, L. M. Rapid and continuous modulation of hippocampal network state during exploration of new places. PLoS ONE 8, e73114 (2013).

Chintaluri, C. et al. kCSD-Python, reliable current source density estimation with quality control. PLoS Comput. Biol. 20, e1011941 (2024).

Potworowski, J., Jakuczun, W., Leski, S. & Wojcik, D. Kernel current source density method. Neural Comput. 24, 541–575 (2012).

Alterovitz, G. & Ramoni, M. F. (eds). Systems Bioinformatics: An Engineering Case-Based Approach (Artech House Publishers, 2007).

Kay, K. et al. A hippocampal network for spatial coding during immobility and sleep. Nature 531, 185–190 (2016).

Dvorak, D., Chung, A., Park, E. H. & Fenton, A. A. Dentate spikes and external control of hippocampal function. Cell Rep. 36, 109497 (2021).

Santiago, R. M. M. et al. Waveform-based classification of dentate spikes. Sci. Rep. 14, 2989 (2024).

Headley, D. B., Kanta, V. & Paré, D. Intra- and interregional cortical interactions related to sharp-wave ripples and dentate spikes. J. Neurophysiol. 117, 556–565 (2017).

Lacourse, K., Delfrate, J., Beaudry, J., Peppard, P. & Warby, S. C. A sleep spindle detection algorithm that emulates human expert spindle scoring. J. Neurosci. Methods 316, 3–11 (2019).

Vallat, R. & Walker, M. P. An open-source, high-performance tool for automated sleep staging. eLife 10, e70092 (2021).

Buccino, A. P. et al. SpikeInterface, a unified framework for spike sorting. eLlife 9, e61834 (2020).

Pachitariu, M., Steinmetz, N., Kadir, S., Carandini, M. & D, H. K. Kilosort: realtime spike-sorting for extracellular electrophysiology with hundreds of channels. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/061481 (2016).

Chapuis, G. et al. Spike sorting pipeline for the international brain laboratory. Channels 10, 6 (2022).

Varol, E. et al. Decentralized motion inference and registration of Neuropixel data. In IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) (IEEE, 2021).

Garcia, S. et al. A modular implementation to handle and benchmark drift correction for high-density extracellular recordings. eNeuro https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0229-23.2023 (2024).

Petersen, P. C., Siegle, J. H., Steinmetz, N. A., Mahallati, S. & Buzsáki, G. CellExplorer: a framework for visualizing and characterizing single neurons. Neuron 109, 3594–3608 (2021).

Laird, N. M. & Ware, J. H. Random effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 38, 963–974 (1982).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Bretz, F., Hothorn, T. & Westfall, P. Multiple Comparisons Using R (CRC Press, 2011).

Findlay, G. github.com/grahamfindlay/Findlay_et_al_2025_Nature_Neuroscience. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.17364618 (2025).

Selya, A. S., Rose, J. S., Dierker, L. C., Hedeker, D. & Mermelstein, R. J. A practical guide to calculating Cohen’s f2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Front. Psychol. 3, 111 (2012).

Findlay, G. gin.g-node.org/grahamfindlay/Findlay_et_al_2025_Nature_Neuroscience. G-Node https://doi.org/10.12751/G-NODE.XZMV31 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to C. Punke for sleep scoring, to K. Driessen for many helpful conversations and for helping in developing methods, to D. Retzlaff for managing over half a petabyte of data, to B. Karsh for SpikeGLX and his eagerness to accommodate the unique challenges of multiday continuous recordings and to R. Mao, J. Ellefson, S. Loschky and F. Squarcio for the help with SDs. This work was supported fully or in part by U.S. Department of Defense grant (W911NF1910280 to C.C. and G.T.), NIH grant (1R01GM116916 to G.T.) and the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation (to G.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C., G.T. and G.F. designed the study and wrote the paper. G.F. and M.L.C. collected the data. G.F. and T.B. analyzed the data. G.F. and W.M. performed the statistical analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Neuroscience thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

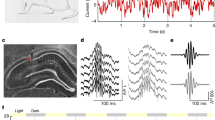

Extended Data Fig. 1 Examples of single-unit activity during NREM sleep associated with sharp waves (SPWs) and dentate spikes (DSs).

a, Subset of thalamic, neocortical, and subcortical regions from the full dataset is shown, chosen to illustrate diversity of modulation. In 11 of 16 subjects, additional Neuropixel probes were implanted in more anterior and/or posterior regions of the brain, including frontal and visual cortical areas and striatum. Hippocampal pyramidal cells, narrow interneurons, and wide interneurons were classified on the basis of their NREM waveform and autocorrelogram shapes102. Perievent time histograms were computed using 25 ms bins for windows extending ±10 s around each event, then Z-scored relative to this entire window. Only cells that could be tracked continuously for the full 48 h of experiments featuring sleep deprivation with novel object exposure are shown, ±1 s around event, shaded regions represent standard error of the mean. CA1 (n = 20), CA3 (n = 45), DG (dentate gyrus; n = 35). b, Same for thalamic single units. Po (posterior medial nucleus; n = 298), LP (lateral posterior nucleus; n = 182), VPM (ventral posterior medial nucleus; n = 126), CL (central lateral nucleus; n = 44), LD (lateral dorsal nucleus; n = 26). c, Same for neocortex. PPC (parietal association cortex; n = 72), M2 (secondary motor cortex; n = 275), PrL (prelimbic cortex; n = 234), Cg1 (cingulate area 1; n = 81), VO (ventral orbital cortex; n = 54), MO (medial orbital cortex; n = 49), IL (infralimbic cortex; n = 38), V2 (secondary visual cortex; n = 28). d, Same for CPu (caudate putamen; n = 30), CLA (claustrum; n = 58), BRF (brainstem reticular formation; n = 36), ZI (zona incerta; n = 36) and OB (olfactory bulb; n = 21).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Comparison of sleep architecture by experiment type (novelty and locomotion).

a, Proportion of total time spent in each state (‘fractional occupancy’). There are no significant differences between novelty (n = 16 subjects) and locomotion (n = 8 subjects) experiments in baseline or recovery. b, Same data, but presented to facilitate comparison between baseline and recovery. Sleep deprivation in both experiments induces similar increases in NREM occupancy, and novelty also increases time spent in REM sleep. Black bars represent significant differences, assessed using general linear hypothesis tests on mixed effects models. Gray bars indicate that either a main effect or post hoc test was nonsignificant. The gray dot in a indicates a p-value between 0.05 and 0.1. All tests were two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Information, and Methods for details). Boxplots show medians and quartiles. Whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5 IQRs from the nearest hinge. c, Mean cumulative distribution functions for bout duration, separated by sleep stage (columns), experiment type (row) and presleep or postsleep deprivation (color), with 95% confidence intervals. Sleep deprivation in both novelty and locomotion experiments produces a clear rightward shift of NREM bout duration, and locomotion results in longer REM bouts without changes in time spent in REM sleep (b).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Slow wave, sharp wave, ripple and dentate spike properties by experiment type.

a, Same data as Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1, separated by experiment. In this and the following panels, bars above plots indicate general linear hypothesis tests on mixed effects models (n = 29 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 animals). Black bars reflect post hoc comparisons that were significant. Black bars with triangular endcaps indicate the presence of a significant interaction between experiment and condition, assessed using an asymptotic likelihood ratio test. Black bars with circular endcaps reflect the absence of a significant interaction between experiment and condition, but a significant main effect of condition. All tests were two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons (see Supplementary Table 1 and Methods for details). Note that in the dual experiment, the time elapsed between early and late extended wake is longer than for novelty and locomotion, and the time elapsed between early and late recovery sleep is shorter. b, Same data as Fig. 2e, separated by experiment. c, Same data as Fig. 2f, separated by experiment. d, Same data as Fig. 3e, separated by experiment. e, Cortical power in the 2–6 Hz range during extended wake, replicating20. Power was computed identically to SWA, but for the frequencies of interest (2–6 Hz). As for SWA, a linear mixed effects model was created using all six conditions of interest (early and late baseline NREM sleep, early and late extended wake, early and late recovery NREM sleep) and tested for an interaction of condition with the 2–6 Hz power. After finding a significant interaction (p < 1 × 10−7; f2 = 0.447), we performed post hoc tests for a difference between early and late extended wake, which were significant for novelty (p = 0.017; d = 0.873; n = 12 subjects) and locomotion (p = 0.017; d = 1.23; n = 6 subjects), but not dual (p = 0.182; d = 0.755; n = 5 subjects). Boxplots show medians and quartiles. Whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5 IQRs from the nearest hinge. f, Neocortical single unit mean firing rates in early and late baseline NREM sleep (ON periods; blue), early and late extended wake (green), and early and late recovery NREM sleep (red), for putative pyramidal cells (n = 721), narrow interneurons (n = 83), and wide interneurons (n = 55). All data are from novelty experiments, and only cells that could be tracked continuously for the full 48 h were analyzed. Bars above plots indicate post hoc tests performed on mixed effects models. Examination of residual plots revealed that model assumptions of constant variance and normality were better satisfied by square-root transformation of firing rates than log transformation, so the former was used for statistical analyses. The full model was formulated with condition as primary covariate and a nested random effects structure, with unique cell ID nested inside subject. A main effect of condition was found in every case, followed by post hoc tests for comparisons between conditions. The somewhat paradoxical increase in pyramidal cell firing rates from early to late recovery sleep may be explained by the relatively short elapsed duration between the two conditions (relative to early and late baseline sleep), since late recovery sleep was constrained to fall within the light cycle, to account for the known effects of immediate light exposure on cortical SWA (Methods). During this period, NREM sleep is prioritized over REM sleep, the latter of which may be associated with the largest decreases in firing rate24. g, As in f, but for hippocampal single units (putative pyramidal cells, n = 27; narrow interneurons, n = 57; wide interneurons, n = 16). See Methods (spike sorting) for details. In f,g, boxen plots show the median and quartiles, and a number of additional quantiles proportional to the size of the data: In both f and g, additional boxes show the 12.5% and 87.5% quantiles. In f only, outer boxes show the 6.25% and 93.75% quantiles.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Measures of locomotor and exploratory activity during sleep deprivation.

a, Comparing EMG levels across conditions shows no significant differences between early and late extended wake, regardless of experiment, suggesting that increases in SPW-ripples during sleep deprivation are not attributable to muscle fatigue. Right, same extended wake data, faceted by experiment type (novelty, n = 12 subjects; locomotion, n = 6 subjects; dual, n = 5 subjects) and showing within-subject changes. b, Hippocampal theta shows a strong, significant increase over the course of extended waking in both novelty and locomotion experiments (the lack of change from early to late dual extended wake should be interpreted with care, since it is a comparison of forced locomotion (early) to novelty (late)). The increase in theta during sleep deprivation is the opposite of what one might expect if muscle fatigue had increased during sleep deprivation. c, Over long timescales theta power on its own may be confounded by broader homeostatic tendencies. Taking the ratio of hippocampal theta to hippocampal delta effectively normalizes theta to account for broader spectral changes. The theta:delta ratio does not change significantly from early to late extended wake in novelty experiments. It shows a slight but significant increase in locomotion experiments, and a slight but significant decrease in dual experiments. Black bars represent significant differences, assessed using general linear hypothesis tests on mixed effects models. All tests were two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons (see Supplementary Table 1 for p-values and effect sizes, and Supplementary Information for confidence intervals; see Methods for details). In a–c, boxplots show medians and quartiles. Whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5 IQRs from the nearest hinge. d, Normalizing theta by delta (or overall spectral power) still produces a measure that behaves similarly to theta in most respects and provides information complementary to EMG. The black solid line indicates the presence of a significant linear relationship in the absence of an interaction with experiment type. Linear relationships and 95% confidence intervals are model expectations estimated using a marginal effects method (see Supplementary Table 1 for p-values and effect sizes, and Supplementary Information for confidence intervals; see Methods for details).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparison of sharp wave, ripple and dentate spike properties during sleep deprivation with novel objects after free behavior versus after forced locomotion.

In novelty experiments, subjects are sleep deprived using novel objects after a night of free behavior. In dual experiments, subjects are sleep deprived using novel objects after forced locomotion (conveyor). a, Comparing the first hour of novel object exposure in both cases shows that SPW rate and amplitude are higher after forced locomotion. b-c, As for SPW rate and amplitude, ripple rate, DS rate, and DS amplitude are higher after forced locomotion. Boxplots show all subjects (n = 16), including the subset (n = 11), who did not experience novel object exposure after forced locomotion. Boxplots show medians and quartiles. Whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5× IQRs from the nearest hinge. Black bars represent significant differences, assessed using asymptotic likelihood ratio tests on mixed effects models (see Supplementary Table 1 for p-values and effect sizes, and Supplementary Information for confidence intervals; see Methods for details). Pair plots show only subjects who received both kinds of novel object exposure within the same experiment (that is, ‘dual’ experiments) (n = 5).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Effect of REM sleep on SPW rate and amplitude.

We identified all episodes of REM sleep that were ‘sandwiched’ on either side by episodes of NREM sleep, and possibly preceded by IS. That is, we found all NREM1 → REM → NREM2 and NREM1 → IS → REM → NREM2 sequences. We then computed the change in mean within-subject, Z-scored SPW rate and amplitude from pre-REM (NREM1) to post-REM (NREM2). a, Left, the distribution of changes in NREM SPW amplitude from pre-to-post-REM sleep. Right, the same changes in SPW amplitude as a function of the sandwiched REM sleep bout’s duration. b, Same as a, but for SPW rate.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Relationships between cortical DS, SPW and spindles.

a, Consistent with recent reports29, most DSs were not expressed within +/− 50 ms of an SPW (median (IQR) 91.8% (90.1–93.2%), n = 29 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 subjects). b, Cross-correlograms of DS-ripple coupling during Wake, NREM sleep, IS and REM sleep. There was a small increase in the probability of ripples around the time of DSs, and a smaller increase in the probability of DSs around the time of ripples, also replicating29. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals for the mean (n = 29 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 subjects). c, Various spindle properties during early and late baseline NREM sleep, and early and late recovery NREM sleep. d, Spindle and DS detection rates in wake, NREM sleep, intermediate state (IS) and REM sleep. Although spindle rates were high in IS sleep relative to NREM sleep, DS rates were not. In c and d, black bars represent significant differences, assessed using general linear hypothesis tests on mixed effects models. Gray bars indicate that either a main effect or post hoc test was nonsignificant. All tests were two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons (see Supplementary Table 1 for p-values and effect sizes, and Supplementary Information for confidence intervals; see Methods for details). Boxplots show medians and quartiles. Whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5 IQRs from the nearest hinge. e, Little-to-no coupling of DS to spindles was observed. Right, normalized or ‘excess’ ripple probabilities, after accounting for covariation of event rates at timescales greater than 2 s (shift-predictor method, 1 s jitter, 100 surrogates each). Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals for the mean. f, Ripple probability was consistently modulated by spindle occurrence. g, No qualitative difference was observed in the spindle-ripple cross-correlogram profile either over or between baseline and recovery NREM sleep. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals for the mean (n = 29 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 subjects) in e–g.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Additional analyses of cortical and hippocampal sleep needs.

a, Time points (1 h each) used for comparison (as in Fig. 4). b, Lack of significant correlation between SPW-ripple and DS rebounds between early recovery sleep and matched circadian time in baseline (n = 28 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 animals). c, Lack of correlation between cortical SWA rebound and changes in most hippocampal parameters (ripple frequency being the exception) during recovery sleep (n = 28 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 animals). In this and the following panels, the asterisk on the x-axis indicates that the hippocampal parameter did not show a significant difference across the interval being considered (for example, early and late recovery sleep in c). d, As in c, but for the baseline day (n = 28 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 animals). e,f, Same as c and d but, analogously to Fig. 4, expanded to include additional cortical regions (64 observations across 13 cortical areas) and the possibility of an interaction with neocortical region—primary visual (V1; n = 6), secondary visual (V2; n = 14), primary motor (M1; n = 4), secondary motor (M2; n = 10), medial parietal association (mPPC; n = 8), lateral parietal association (lPPC; n = 4), prelimbic (PrL; n = 5), cingulate (Cg1; n = 4), infralimbic (IL; n = 3), ventral orbital (VO; n = 3), medial orbital (MO; n = 1), entorhinal (EC; n = 1), retrosplenial (RS; n = 1). For analysis, areas were grouped (see Methods for details)—M1 and M2 into motor cortex (n = 14), V1 and V2 into visual cortex (n = 20), mPPC and lPPC into parietal association cortex (n = 12), VO, MO, IL, PrL, and Cg1 into frontal cortex (n = 16), and EC and RS into parahippocampal cortex (n = 2). Solid gray and gold lines indicate significant linear relationships in the presence of an interaction between experiment and the covariate (not region), and black solid lines indicate the presence of a significant linear relationship in the absence of an interaction. The solid green line in e indicates a negative correlation between DS amplitude decline and cortical SWA decline only in visual cortex following locomotion. Interactions and main effects were assessed using asymptotic likelihood ratio tests, and post hoc tests were performed using general linear hypothesis tests. All tests were performed on linear mixed effects models, were two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons. Linear relationships and 95% confidence intervals are model expectations estimated using a marginal effects method (see Supplementary Table 1 and Methods for details).

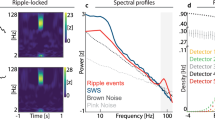

Extended Data Fig. 9 Slow:fast gamma ratios by region.

a, Slow:fast gamma ratio in 1-s bins when SPWs are present (SPW-wake, NREM) or absent (no-SPW wake) (n = 29 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 subjects). Boxplots show medians and quartiles. Whiskers are drawn to the farthest datapoint within 1.5× IQRs from the nearest hinge. b, As in a, subdividing the 1-s epochs based on the number of SPW (n = 47,028,743 epochs across 29 sessions of 3 kinds from 16 animals). Given that (1) the association of higher slow/fast gamma with higher numbers of SPW is present in most areas, (2) is not maximal in the stratum radiatum, where artifactual gamma should be highest (for example, stratum oriens c.f. stratum radiatum), and (3) is present in bins with only 1 SPW, it is unlikely that the entire association is driven by the artifactual increase in slow gamma induced by ripple chains39. c, As in b, but showing slow gamma only. Note the association of SPW number with slow gamma in remote, upstream regions that are dominant sources of physiological slow gamma (DG and CA3), where no SPW-associated waveform that can induce artifactual gamma is present. Boxen plots show the median for each distribution in b and c, and the logarithm of each distribution’s size determines the number of quantile ranges shown, so that each level accounts for half of the remaining probability mass, and the outermost boxes approximate the data’s Tukey fences.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Power spectral densities by region and condition.

a, Time points (1 h each) used for comparison. b, Mean power spectral density (PSD) and 95% confidence interval, colored by condition according to a. c, Comparisons between PSD in b, expressed as percent change. For example, NREM rebound (dark purple) is the percent change in early recovery NREM power spectral density relative to late baseline NREM. All comparisons are performed within-subject before averaging. Shaded regions show 95% confidence intervals. For space reasons, all data presented are from novelty experiments. No qualitative differences were observed for locomotion or dual experiments. As expected, the largest modulation is of cortical low frequencies, being ~150–200% higher in early recovery sleep than in late (circadian-matched) baseline sleep. The next largest modulation is of ripple power in the stratum pyramidale, being ~ 50–150% higher in early recovery sleep than in late baseline sleep, and of low frequencies in the stratum oriens, being ~50–80% higher in early recovery sleep than in late baseline sleep. Rebound in hippocampal high frequencies is more moderate (~20–40%) elsewhere.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5 and Supplementary Note (statistical data).

Supplementary Table 1

Exact P values and effect sizes for main text Figs. 2d-i, 3e-f, 4b-e, 5a,c, Extended Data Figs. 2a-b, 3a-f, 4a-d, 5a-c, 7c-d, 8b-f, and Supplementary Fig. 5c. All tests were performed on LME models, were two-sided and corrected for multiple comparisons. Interactions and main effects were assessed using asymptotic likelihood ratio tests, and post hoc tests were performed using general linear hypothesis tests. All other statistical data, including test statistics, regression coefficients, confidence intervals and effect sizes for nonsignificant results, can be found in the Supplementary Note, and all statistical code is publicly available on GitHub. See Methods for details. For Fig. 4d,e and Extended Data Fig. 8e,f, results of tests for interactions are reported in the following order: region–experiment–covariate/experiment–covariate/region–covariate/experiment–region.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Findlay, G., Cavelli, M.L., Bugnon, T. et al. A hippocampal ‘sharp-wave sleep’ state that is dissociable from cortical sleep. Nat Neurosci (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02141-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02141-8