Abstract

Data-driven fault detection and diagnosis (FDD) for buildings’ heating, ventilating, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems has gained popularity in recent years. However, the scarcity of well-labeled data that represents true fault symptoms presents a challenge for developing new FDD methods. Furthermore, there is growing interest in applying transfer learning (TL) for building applications, where well-labeled data from one building is used to diagnose faults in a related but different building. Successful evaluation of TL algorithms requires at least two datasets that share similarities yet exhibit differences in some operational conditions. Unfortunately, the lack of comparative studies to identify suitable dataset pairs has slowed the progress of TL or other inter-dataset studies. To address these challenges, this paper focuses on the air handling unit (AHU), a key HVAC subsystem, and 1) presents the publication of eight new datasets, operating under fault-free and various faulty conditions; and 2) conducts a comprehensive study on AHU fault datasets to identify dataset pairs and their associated faults that are most suitable for evaluating TL algorithms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

The building sector accounts for approximately 40% of global energy consumption1, highlighting a great potential to reduce energy use and carbon emissions through improving building operation efficiency. The concept of smart buildings has therefore emerged, which integrates advanced data-driven technologies to optimize energy performance and maintain occupant comfort in real time2. Among the key applications of data-driven smart buildings, data-driven fault detection and diagnosis (FDD) of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems plays a critical role due to its significant impact on building energy use and carbon emission3, equipment life, occupant comfort4, and indoor air quality5. In addition, the growing emphasis on grid-interactive buildings, which can reliably provide load-flexibility services to the grid, underscores the importance of having fault-free HVAC systems, providing further motivation for FDD technology development6.

Compared to traditional rule-based FDD approaches, data-driven methods for HVAC FDD have gained much popularity in recent decades due to their potential for improved performance while being less time-consuming or dependent on experts7,8. In these methods, operational data collected from building automation systems (BAS) and sensors are employed by FDD software tools to automatically detect equipment issues and degrading performance9. Overall, support vector machine (SVM), Bayesian networks, and principal component analysis (PCA) have been the most popular algorithms for data-driven HVAC FDD in the literature8. Apart from them, deep learning-based models have attracted much attention in recent years due to their advanced feature extraction ability, where convolutional neural networks (CNN), and recurrent neural networks (RNN) have been the most popular ones10.

Although the results of such algorithms are promising, many papers have declared that the lack of well-labeled data, representing the true fault symptoms, is the main barrier to testing the effectiveness of data-driven algorithms and developing new ones8,11. While large volumes of operational data can be exported from today’s building control and automation systems, much of them are unsuitable for algorithm training due to data quality issues, the presence of unknown and unlabeled faults, and extreme difficulty in assembling a large-scale dataset that captures climate, HVAC configuration, and operational diversities. This makes the development of well-labeled and validated data, especially for less-investigated faults and building operation modes, a crucial task and challenge.

Furthermore, many studies12,13,14 have documented a decline in models’ diagnosis performance when the operational conditions (such as building load or equipment size) and, consequently, the distribution of the testing data differ from the training data. Thus, a growing body of literature has started to focus on the application of transfer learning (TL) in HVAC FDD, where researchers deal with distribution discrepancies between datasets15 by leveraging rich labeled data from one dataset, known as the source domain, to solve a new but related task in the shifted dataset, referred to as the target domain12. TL for fault diagnosis using limited labeled target domain16,17, completely unlabeled target domain18,19,20, and multiple source domains21 are the most popular research areas in this field.

However, a successful evaluation of the proposed TL methods is only possible by having at least two datasets with the same main characteristics, such as control strategy or operating season, but different to some extent in other disturbances, such as occupancy load, system design (e.g., variable air volume (VAV) vs. constant air volume (CAV) systems), and equipment size. Nevertheless, the scarcity of well-labeled HVAC fault data, as well as the lack of a comprehensive study on existing datasets to identify appropriate dataset pairs and their associated faults that meet the above-mentioned TL criteria (i.e., sharing similarities in some aspects while differing in others) place a huge hurdle in successfully developing and testing new TL algorithms for the HVAC FDD field.

Prior works, such as the LBNL FDD datasets22,23 and NISTIR-6964 project24, represent foundational contributions to AHU fault data, and provide case studies demonstrating how these datasets can be utilized for FDD purposes. This research builds upon those early efforts through the following key advancements: (1) Expanding the collection of datasets with enhanced features, longer fault durations, and diverse building configurations, making them valuable complements to existing public AHU fault data, especially for data-intensive FDD algorithms. (2) Incorporating under-investigated faults, including gradual faults (especially relevant for fault prognosis) and cyber-attacks. (3) Conducting a comprehensive study of existing datasets to identify suitable dataset pairs and corresponding faults to facilitate data preparation for TL algorithms. Beyond FDD applications, this work broadens the applicability of these datasets for TL algorithm development and performance evaluation.

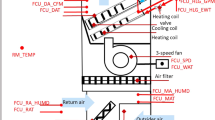

To achieve the above-mentioned objectives, this paper firstly documents eight new air handling unit (AHU) fault datasets, covering various building configurations, control strategies, seasons, and injected faults with expanded duration and feature sets. AHU is specifically investigated in this study since it is the most commonly-used secondary HVAC equipment in commercial buildings, significantly impacting building energy use (accounting for nearly 35% of total HVAC energy consumption in commercial buildings25) as well as occupant comfort compared to many other HVAC components26,27,28. Figure 1 schematically illustrates the major components of a typical single-duct AHU, including supply and return fans for air circulation, heating and cooling coils for air conditioning, three dampers for regulating airflow between AHU and outdoor environment, various sensors and actuators, and a controller that processes sensor measurements to generate control signals29. Various faults may occur in any AHU component, disrupting its normal operation and leading to performance degradation. Some common faults include stuck or leaking dampers or valves, biased temperature sensors, and fan failures30. Although the main AHU components (e.g., cooling coil, fans, and dampers) are the same among the datasets introduced in this paper, the detailed diagrams may differ. Thus, the detailed schematic for each AHU is provided in the corresponding dataset folder in the shared repository.

Schematic diagram of a single-duct AHU (adapted from29).

Table 1 illustrates the eight AHU datasets described in this paper. Notice that the control strategies used for the AHUs can be categorized as either: (1) rule-based control (RBC) or traditional control or (2) ASHRAE Guideline 36-based control31 (G36 hereinafter). G36 provides high-performance sequences of operation for HVAC systems, offering standardized control sequences that enhance energy efficiency, system stability, and code compliance compared to conventional control strategies. Due to high interconnectivity of components under G36 control, fault symptoms at the component level may propagate through the whole system, leading to cascading fault impacts32. Consequently, G36 responds to faults in a different and more sophisticated manner than RBC strategies32. This difference in fault behavior motivated the categorization of datasets into RBC and G36-based datasets.

Table 1 also provides key information for each dataset, including the system type (whether the data come from a real building or a simulated environment), the number of features (measured or computed variables such as sensor and control signals), the sampling rate (time interval between successive data points), and fault duration (the period over which faults were introduced or observed).

Additionally, a detailed comparative study of both publicly available AHU fault datasets and the datasets presented in this paper is conducted to identify suitable dataset pairs and their corresponding faults, providing researchers with resources for evaluating their TL algorithms. Notably, the results of this section can also be used for other inter-class studies, such as cross-building fault-symptoms comparisons, but TL remains the primary use case of this work.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: Methods section provides detailed information on the facilities used for data generation, AHU specifications, the list of faults, and a comparative study among datasets. Data Records presents a summary table of the datasets along with a link for public access to the described datasets. Technical Validation includes examples of validation processes to ensure data accuracy. The paper concludes with Usage Notes and Code Availability sections.

Methods

As illustrated in Table 1, the datasets presented in this study were generated using a diverse range of facilities, system configurations, control strategies, weather conditions, and implemented faults. Detailed descriptions of these facilities, HVAC system characteristics, and faults are described in Section 2.1. Additionally, a comparative analysis of the FDD datasets is presented in Section 2.2 to facilitate cross-datasets studies and to enhance their usability for various applications.

Datasets description

The eight datasets, as summarized in Table 1, are described in detail in this section.

RBC-ASHRAE1312

This dataset, generated as part of the ASHRAE-1312 project33, has been a popular dataset for examining FDD algorithms in the last two decades. It comprises (1) real data collected from the AHUs located at the Iowa energy resource station (ERS), where the AHUs were operated under fault-free or various faulted conditions; and (2) simulated data collected from a validated virtual testbed representing the AHUs at the ERS. A shorter and limited version of this dataset is already publicized in the reference22. This study includes the ASHRAE-1312 dataset with expanded features and a more completed list of faults. To avoid repetition, the system configuration and control sequences is not provided in this paper, since a detailed description is already available in ASHRAE RP-131233. A more detailed description of the faults is provided below.

A total of 18, 12, and 19 faults were injected in the ERS testbed during the summer, winter, and spring seasons, respectively. These faults were classified into four categories: controlled device, equipment, controller, and sensor. Each fault scenario is paired with corresponding fault-free scenario for analyzing its symptoms. In accordance with FDD terminology, the fault free scenario is also referred to as the as baseline scenario in this paper, representing normal operation of the system33. Due to the extensive list of faults, only detailed descriptions of two fault categories (controlled device and equipment) are provided in Table 2 to offer an overview of the dataset.

RBC-Nesbitt

Nesbitt Hall, a seven-story mixed-use commercial building on Drexel University’s campus in Philadelphia, PA, USA, was selected as the test building for faulted data generation from 2016 to 2018. The HVAC system configuration in the building is depicted in Fig. 2, which consists of a water-cooled chiller system, three AHU systems that supply several VAV terminal units, and a hydronic heating system. Detailed information on the building is included in the reference34.

(a) HVAC system configuration at Nesbitt Hall; and (b) Nesbitt Hall at the campus of Drexel University (adapted from34).

In total, 17 faults were injected into the HVAC system of the Nesbitt Hall. These faults were selected for implementations based on safety considerations, facility capabilities, and minimizing impact on the indoor environment. Additionally, three naturally occurred faults, observed during the data collection period, were also included. This list of all 20 faults is presented in Table 3, and details on data collection are discussed in the reference35.

RBC-5wk

The remaining datasets (RBC-5wk and all datasets with G36 control strategy) were created using a virtual testbed developed in Modelica, an object-oriented dynamic modeling solution, Buildings Library 7.0.036. This Modelica virtual testbed37, referred to as the MedOffice virtual testbed hereafter, is based on and verified against the medium-sized office prototype model developed by the U.S. Pacific Northwest National Lab38 in EnergyPlus39. The original EnergyPlus model has three floors, but only the middle floor, featuring five zones with a VAV AHU, was simulated here for simplicity. Additionally, a chilled water plant system and a boiler hot water system (conforming to ASHRAE RP-171131) were added to the MedOffice virtual testbed, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Modelica implementation of the medium-sized office building (adapted from43).

As shown in Fig. 4, the MedOffice virtual testbed represents a single-duct multi-zone VAV AHU connected with five VAV terminal boxes that serve five zones (four exterior and one interior zone) on one floor. It consists of component models such as VAV system with terminal reheat unit model, building envelope model, and a model for air flow through building leakage and through open doors based on wind pressure and flow imbalance of the HVAC system.

Schematic of the MedOffice virtual testbed (adapted from43).

The chilled water is supplied by a central chiller plant which consists of a chiller, a waterside economizer, a cooling tower, and associated one chilled water pump and one cooling water pump. The boiler, fed by natural gas, supplies hot water to the AHU heating coil. The system was sized based on the location, which includes two different ASHRAE climate zones: 3 A (Tuscaloosa, AL) and 5 A (Chicago, IL).

Traditional control sequence from the ASHRAE 2006 standard for common HVAC systems40 was adopted for the AHU in the MedOffice virtual testbed to develop the RBC-5wk dataset. As an example, the AHU supply air temperature (SAT) control sequence is described here, since it provides both a representative overview of the implemented control strategy and a reference point for comparison with G36-based datasets41: The heating coil valve, outside air damper, and cooling coil valve were modulated in sequence to maintain the SAT setpoint. The SAT was maintained at a constant value depending on the operation models. For example, the SAT cooling setpoint was set as 12 °C during occupied hours and 30 °C during unoccupied hours. SAT heating setpoint was set at 10 °C for preheating purposes and worked in coordination with the reheat valve at the VAV terminal box to meet the heating requirements. The controller of the terminal units tracked the room air temperature set point based on a ‘dual maximum with constant volume heating’ logic42. For the detailed implementation of this control logic, please refer to the model ‘Buildings.Examples.VAVReheat.ASHRAE2006’ of Modelica building library36.

Using the MedOffice virtual testbed with weather conditions for Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, data from multiple fault scenarios were collected, as detailed in Table 4. The first week of each fault scenario was simulated under the fault-free condition, and the following four weeks were simulated under the associated fault scenario.

G36-1wk

The G36 datasets were developed using the same MedOffice virtual testbed as RBC-5wk, but employed a different control sequence, namely G36, for the AHU section. A brief description of the SAT control as an example of G36 control sequences is provided below to be compared with RBC-5wk section, explained in section 2.1.3. A more detailed description of G36 is provided in references31,43,44.

As recommended by G36, the SAT control loop is to reset SAT setpoints based on the zone temperatures and outdoor air temperature. The range of outdoor air temperatures (16–21 \(^\circ C\)) was used to maximize airside economizer hours. The SAT setpoint was reset from its minimum value (e.g., 12 \(^\circ C\)) when the outdoor air temperature reached its maximum value or above (e.g., 21 \(^\circ C\)), proportionally up to the maximum SAT (e.g., 18 \(^\circ C\)) when the outdoor air temperature reached its lower bound (e.g., 16 \(^\circ C\)). The SAT setpoint was reset using ‘trim and response (T&R)’ logic, which is explicitly modeled in the Modelica models31.

To develop the G36-1wk dataset, a total of 359 fault scenarios, distributed across the cooling, shoulder, and heating seasons, were simulated using the MedOffice virtual testbed with Chicago, IL weather condition. These faults were categorized into seven various types: sensor, duct & pipe, valve & damper, HVAC equipment, control, schedule, and design & construction. Due to the extensive list of faults, detailed description of only sensor and HVAC equipment categories for the heating season is provided in Table 5 to offer an example of the dataset. Each fault scenario was simulated over a week and assumed to be active continuously throughout the week. All fault scenarios have a one-minute interval sampling rate. Detailed information on fault impact analysis, fault injection methods, and evaluated key performance indexes (KPIs) is available in32.

G36-5wk

The baseline (i.e., when the system is considered fault-free, as discussed in section 2.1.1) and three specific fault scenarios of G36-1wk were chosen to be simulated over an extended period of five weeks during the cooling season. This longer simulation time aimed to capture a broader variation of influencing conditions such as outdoor air and system load; thereby enhancing the generalization of FDD algorithms and increasing the training samples for data-intrusive ones such as deep learning-based models. The three selected faults, detailed in Table 6, occurred in three critical and fault-prone components, namely the cooling coil valve, outdoor air damper, and supply duct.

G36-Degrad

Unlike instantaneous faults, gradually degrading faults must be simulated over an extended period (e.g., one year) to accurately capture the progressive impact of the degrading component on system performance45. Three types of commonly observed degrading faults, i.e. fouling (airside and waterside), duct leaking, and sensor bias, were modeled by adding time-dependent degradation functions in the MedOffice virtual testbed for the component that the fault affects. Table 7 summarizes the fouling faults and their method of imposition, which was by modifying the component’s heat transfer behavior and pressure drop across it46,47. Table 8 summarizes those for the non-fouling faults.

The weather profile for Tuscaloosa, AL was used to simulate the degradation faults. All fault scenarios were conducted over a full year (from January 1st to December 31st), with one exception: The condenser waterside fouling fault was excluded until a specific hot day (the 170th day of the year), as the cooling plant was inactive prior to that day. Further details about fault injection and evaluations are described in48.

G36-Cyber

This dataset was designed to evaluate various cyber-attacks (active treats) for a typical building HVAC system. Cyber-attack faults are increasingly critical in HVAC systems for two main reasons: Firstly, the communication protocols for BAS are not designed with security as a primary requirement. Secondly, with more connected devices, a vulnerability in one component can be used to access data, attack, and compromise other components, or even worse, the larger power grid49,50,51,52.

Two primary types of cyber-attacks were modeled in this regard: the data-intrusion attack that corrupted the data integrity, and the denial-of-service (DoS) attack that undermined communication between the controller and the plant. The attacks were injected during peak load periods to analyze their impact on both building service and grid service. As shown in Table 9, the timing of the attacks varied to demonstrate the flexibility of threat modeling. The quantified impact assessment on the building’s operational performance can be found in43,53.

G36-HIL

Hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testbed provides a cost-effective method to evaluate how a fault affects certain perspectives of a real system. In this dataset, the MedOffice virtual testbed, described in section 2.1.4, was integrated with a set of real BAS control system to form a HIL testbed54,55,56, as depicted in Fig. 5. This HIL testbed, referred to as the MedOffice-HIL testbed hereafter, comprised three main components: (1) a real-time dSPACE machine, that emulated the virtual building modeled in Modelica. (2) A set of BAS controllers of chiller, boiler, AHU and VAV box, which adopted G36 control logic for different HVAC equipment. Their control commands were sent to the virtual building through the real-time HIL machine. (3) A computer server, which hosted the software environment for all the hardware and customized services such as a master program that controlled the experiments. The MedOffice-HIL testbed was capable of emulating both physical faults and cyber-attacks in real-time without requiring actual building zones or HVAC equipment56, while able to emulate fault symptoms in a real control system. The description of injected faults is included in Table 10.

The MedOffice-HIL testbed at Texas A & M University (adapted from37).

Dataset limitations

While the datasets presented in this study offer controlled, well-labeled, and reproducible (for simulated cases) data for research purposes, several limitations should be noted:

-

1.

No multi-fault scenarios: Each fault scenario includes only a single fault at a time. In real building operations, multiple faults can occur concurrently and interact in complex ways, which may alter system responses compared to the isolated-fault conditions represented here.

-

2.

Simplified actuator and component failure modeling: The faults represented in this study capture common HVAC component issues (e.g., valve stuck, damper leakage) through parameter changes or overrides. However, they do not include full physical degradation or abrupt mechanical failures (e.g., motor burnout, actuator linkage breakage), which may produce different symptom patterns.

-

3.

Absence of stochastic sensor noise and control feedback variability: For all simulated data, sensor measurements are noise-free except for cases where a bias or scaling error is explicitly modeled. Likewise, control system behavior is deterministic and idealized, without the small fluctuations and delays often present in real BAS networks. For data collected from real systems, such as RBC-Nesbitt, real-world issues including sensor noise and communication delays were present.

These limitations should be considered when applying the datasets to FDD, transfer learning, or other smart building applications, particularly when adapting algorithms developed with these datasets to real-world systems.

Comparative study and dataset pairs

Datasets pool

The datasets discussed above have broad applications in smart building technology development. However, given that one of the objectives of this paper is to facilitate the data preparation for TL algorithms, this section identifies suitable dataset pairs and corresponding faults for TL purposes. To be consistent with TL nomenclature, a datasets is also referred to as a ‘domain’ in this section. The domain pairs were chosen to satisfy the TL assumption, i.e., while there are some discrepancies between the domains (such as simulation vs. real, different weather conditions, etc.), they share similarities in other aspects (such as control strategy, operation season, etc.).

To broaden the scope of this section, we considered three other popular datasets for AHU fault diagnosis, which are already publicized. These datasets are:

-

1.

NISTIR-6964 dataset24, containing three faults (namely: supply air temperature sensor offset, recirculation air damper stuck open, and heating coil valve leakage) that were injected into the ERS test facility. Since the NIST-6964 dataset and the RBC-ASHRAE1312 dataset were generated from the same test facility with similar principles, these two datasets are considered to belong to the same domain called ASHRAE-NIST.

-

2.

LBNL 2019 dataset22: This dataset contains two main subsets: (a) MZVAV-1 (called LBNL-2019-1 hereinafter), containing six intensities of outdoor air temperature sensor bias injected to a simulated building in Chicago, IL, USA. And (b) SZVAV and SZCAV (called LBNL-2019-2 hereinafter), containing data of seven and 14 faults injected into a real building (FLEXLAB facility in Berkely, CA, USA), respectively.

-

3.

LBNL 2022 dataset23 (called LBNL-2022 hereinafter), containing 20 annual faults of a simulated office building in Chicago, IL, USA.

Pairing principle

The process used to identify suitable domain pairs and corresponding faults is outlined below. An example of this process is shown in Fig. 6 as well.

Step 1) Group domains by control strategy: Since control strategies strongly influence fault symptoms (see Section 1), domains with different control strategies cannot be paired for TL applications. Accordingly, the domains were divided into two groups:

-

a)

RBC: ASHRAE-NIST, RBC-5wk, RBC-Nesbitt, and LBNL-2019-1

-

b)

G36: G36-1wk, G36-5wk, G36-Degrad, G36-Cyber, G36-HIL, LBNL-2019-2, and LBNL-2022

Step 2) Identify candidate pairs within each group: A complete list of domain pairs was identified within each group, resulting in 6 RBC pairs and 21 G36 pairs. For each pair, domains’ similarities and differences were determined. For example, both ASHRAE-NIST and RBC-5WK domains represent medium-sized office buildings as their testbeds. However, ASHRAE-NIST is based on Iowa city, USA weather conditions, while RBC-5wk simulated a building located in Chicago, USA.

Step 3) Match corresponding faults: Faults were matched across paired domains based on two criteria:

-

a)

Seasonal alignment: Fault symptoms can vary significantly by season, so only faults occurring in the same season were matched. For instance, ASHRAE-NIST includes faults from summer, transitional (spring and autumn), and winter seasons. However, RBC-5wk includes only summer faults. Therefore, only summer faults could be matched for this pair.

-

b)

Match by fault type, not exact intensity: Within each season, faults were firstly categorized based on the source component (e.g., malfunctioned cooling coil valve, return fan, etc.). Within each device category, faults were then matched by the symptom rather than the exact fault intensity.

For example, consider the faults affecting the cooling coil valve. The CooCoiValStuck_0 and CooCoiValStuck_15 faults in ASHRAE-NIST, and CooCoiValStuck_0, CooCoiValStuck_5, and CooCoiValStuck_15 faults in RBC-5wk, all correspond to the cooling coil valve being stuck at lower-than-normal position (stuck at either 0%, 5%, or 15% open positions). Thus, these faults are expected to exhibit similar symptoms in the systems, although their intensity (symptom magnitude) may be different. Figure 7 illustrates how these faults impacted three selected features, showing each fault caused the features to have higher-than-normal values, though with different magnitudes.

Impact of cooling coil stuck lower-than-normal faults on (a) ASHRAE-NIST domain and (b) RBC-5wk domain. Arrows indicate the overall impact of faults on each feature. In (a), both faults resulted in higher-than-normal values for all three features. In (b), all three faults similarly led to higher-than-normal values for all three features.

Another example can be the TSup_p1.7 and TSup_p2.8 faults from the same domain pair, both affecting the supply air temperature sensor with a positive bias (1.7 °F and 2.8 °F, respectively). As shown in Fig. 8, these faults produced the same symptoms in the features, but differ in their intensity. This fault-matching approach allows TL researchers to work with varying fault intensities among domain pairs, ensuring that their algorithms are scalable, robust, and ready for real-world applications.

Following this process, a comprehensive list of domain pairs and matched faults was generated. Due to the extensive list of pairs, two example pairs are listed in Table 11 to offer an overview, while the complete list is available in the data folder under ‘DomainPairs.pdf’. Please note, in this table, faults names are shown in abbreviated form for clarity and brevity, with definitions provided in the accompanying PDF for each dataset.

Data Records

The datasets are stored on figshare57. A summarized description of the datasets is provided in Table 12. For each system, the FDD data are stored in individual comma-separated value (CSV) files, and each file contains one fault type under one fault intensity. Datasets are recorded at intervals of either one or five minutes to reflect system operations, which can be re-sampled to any higher interval to fit the needs of specific applications.

Each dataset is accompanied by a pdf document (named ‘00_explanations.pdf’) containing essential details including building and system information (model or experimental facility description, control strategy, data sampling rate, etc.), fault cases (fault types, intensities, abbreviations, etc.), and any extra information, required to better comprehend the datasets.

Technical Validation

Since various systems were utilized for datasets generation, the details of validation processes to ensure data accuracy vary as well. For the sake of brevity, an example of validation process for a single dataset (i.e., G36-5wk) is provided in this section, and readers are referred to the cited publications in each dataset folder for details on experimental facility or simulated model validation.

Regarding the G36-5wk dataset, functional testing was conducted to validate the baseline (fault-free) behavior of the model. This testing verified that system operation aligned with the designed control sequences and reflected fault-free operational behaviors. For example, Fig. 9(a) shows simulated measurements of the zonal temperature and cooling coil valve for the single-duct AHU system. The data trends were examined to confirm that the system operates according to the defined schedule, with occupied hours from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., and a cooling setpoint that modulates from 30 °C during unoccupied times to 24 °C during occupied times. The data trends were further inspected to verify whether the modeled proportional-integral-derivative (PID) parameters for the cooling valve controller were configured to output appropriate control signals, which was confirmed by the smooth trend and absence of significant oscillations in the plotted signal for the cooling coil valve command. Similar validation processes were conducted for other variables as well.

After verifications of the fault-free operational state, additional tests were conducted for each fault scenario. These tests evaluated (a) whether the imposed fault condition was accurately reflected in the data, and (b) whether the expected symptoms of the fault were reflected in other operational trends.

A single fault of G36-5wk dataset (outdoor air damper stuck fully open) is chosen to illustrate the fault validation procedure. As shown in Fig. 9(b), the fault condition was confirmed by observing that outdoor air damper position (black dashed line) was fixed at 1.0 (fully open position), while its control signal was mainly at 0.0 (black solid line) in the controller’s attempt to close it. The initial and main symptoms of this fault were an increased outdoor air flow rate (see purple lines), leading to a reduction in return air flow rates (see green lines) compared to those in the baseline. Similar verification steps were performed for all fault types and intensities in the dataset for model validation.

Usage Notes

A complete inventory of the data was developed to assist users in comprehending the content and form of the data, and the associated AHU systems, controls, and faults. The data itself consists of time-series that can be analyzed with any software tools chosen by the user.

Data availability

The dataset is available at figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29297999.

Code availability

The Modelica buildings library is freely available for download42. A Windows or Linux-based computer with licensed Dymola software was used to run Modelica models to generate datasets presented in this paper. In addition, free program such as OpenModelica58 can be used to run Modelica models as well. HVACSIM+ is freely available, upon request from NIST, and has no operating system requirements. The Modelica simulation code and workflow used to generate the G36-Cyber dataset are openly available on GitHub59.

This repository contains: (1) The complete Modelica models of the G36-controlled medium office building testbed used for cyber-attack simulations. (2) Attack/fault injection modules implementing both data-intrusion and DoS attacks consistent with the described scenarios. (3) A simulation workflow for reproducing the six cyber-attack scenarios. And (4) instructions for running the models in Dymola or OpenModelica, including required library versions and simulation parameters.

The scripts and Modelica models in this repository can be directly used to regenerate the published G36-Cyber dataset. This repository can also serve as a template for generating other fault types described in the simulated datasets (i.e., G36-1wk, G36-5wk, G36-Degrad, G36-Cyber, and G36-HIL) by modifying the fault injection modules, enabling broader fault simulation studies beyond cyber-attacks. For the RBC-ASHRAE1312 dataset, related documentation and any available code can be obtained from the official ASHRAE Website60. Finally, the RBC-Nesbitt dataset was collected from a real building system; therefore, no code was used for data collection or generation.

References

Cao, X., Dai, X. & Liu, J. Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade. Energy and buildings 128, 198–213 (2016).

Malkawi, A. et al. Design and applications of an IoT architecture for data-driven smart building operations and experimentation. Energy and Buildings 295, 113291 (2023).

Granderson, J. et al. Characterization and survey of automated fault detection and diagnostic tools. Report No. LBNL-2001075, (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2017).

Zhang, R. & Hong, T. Modeling of HVAC operational faults in building performance simulation. Applied Energy 202, 178–188 (2017).

Ginestet, S., Marchio, D. & Morisot, O. Evaluation of faults impacts on energy consumption and indoor air quality on an air handling unit. Energy and Buildings 40, 51–57 (2008).

Granderson, J. et al. A labeled dataset for building HVAC systems operating in faulted and fault-free states. Scientific data 10, 342 (2023).

Mulumba, T., Afshari, A., Yan, K., Shen, W. & Norford, L. K. Robust model-based fault diagnosis for air handling units. Energy and Buildings 86, 698–707 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. A review of data-driven fault detection and diagnostics for building HVAC systems. Applied Energy 339, 121030 (2023).

Lin, G., Kramer, H., Nibler, V., Crowe, E. & Granderson, J. Building analytics tool deployment at scale: Benefits, costs, and deployment practices. Energies 15, 4858 (2022).

Zhang, F., Saeed, N. & Sadeghian, P. Deep learning in fault detection and diagnosis of building HVAC systems: A systematic review with meta analysis. Energy and AI 12, 100235 (2023).

Matetić, I., Štajduhar, I., Wolf, I. & Ljubic, S. A review of data-driven approaches and techniques for fault detection and diagnosis in HVAC systems. Sensors 23, 1 (2022).

Zhu, X., Du, Z., Jin, X. & Chen, Z. Fault diagnosis based operation risk evaluation for air conditioning systems in data centers. Building and Environment 163, 106319 (2019).

Zhu, X., Zhang, S., Jin, X. & Du, Z. Deep learning based reference model for operational risk evaluation of screw chillers for energy efficiency. Energy 213, 118833 (2020).

Ghalamsiah, N. et al. Unsupervised domain adaptation for HVAC fault diagnosis using contrastive adaptation network. Energy and Buildings, 115659 (2025).

Liang, X., Li, P., Chen, S., Jin, X. & Du, Z. Partial domain adaption based prediction calibration methodology for fault detection and diagnosis of chillers under variable operational condition scenarios. Building and Environment 217, 109099 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Transfer learning-based strategies for fault diagnosis in building energy systems. Energy and Buildings 250, 111256 (2021).

Li, G., Chen, L., Liu, J. & Fang, X. Comparative study on deep transfer learning strategies for cross-system and cross-operation-condition building energy systems fault diagnosis. Energy 263, 125943 (2023).

Lu, N., Xiao, H., Sun, Y., Han, M. & Wang, Y. A new method for intelligent fault diagnosis of machines based on unsupervised domain adaptation. Neurocomputing 427, 96–109 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Chen, H., Li, S. & An, Z. Unsupervised domain adaptation via enhanced transfer joint matching for bearing fault diagnosis. Measurement 165, 108071 (2020).

Chen, P., Zhao, R., He, T., Wei, K. & Yang, Q. Unsupervised domain adaptation of bearing fault diagnosis based on join sliced Wasserstein distance. ISA transactions 129, 504–519 (2022).

Fan, C., He, W., Liu, Y., Xue, P. & Zhao, Y. A novel image-based transfer learning framework for cross-domain HVAC fault diagnosis: From multi-source data integration to knowledge sharing strategies. Energy and Buildings 262, 111995 (2022).

Granderson, J. & Lin, G. Data Sets for Evaluation of Building Fault Detection and Diagnostics Algorithms. OpenEI https://doi.org/10.25984/1824861 (2019).

Granderson, J. et al. LBNL Fault Detection and Diagnostics Datasets. OpenEI https://doi.org/10.25984/1881324 (2022).

Castro, N., Schein, J., Park, C., Galler, M. & Bushby, S. Results from simulation and laboratory testing of air handling unit and variable air volume box diagnostic tools. Report No. NISTIR 6964, (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2003).

Lecamwasam, L., Wilson, J. & Chokolich, D. Guide to best practice maintenance & operation of HVAC systems for energy efficiency. (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012).

Norford, L. et al. Demonstration of fault detection and diagnosis methods in a real building. Report No. ASHRAE 1020-RP, (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers, 2000).

Carling, P. Comparison of three fault detection methods based on field data of an air-handling unit/discussion. ASHRAE Transactions 108, 904 (2002).

Schein, J., Bushby, S. T. & House, J. Results from laboratory testing of embedded air handling unit and variable air volume box fault detection tools. Report No. NISTIR 7036, (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2003).

Milesi-Ferretti, N. S., Galler, M. A., Bushby, S. T. & Choiniere, D. Evaluating the Performance of DABO and HVAC-Cx Commissioning Tools using the Virtual Cybernetic Building Testbed. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2015).

Nehasil, O., Dobiášová, L., Mazanec, V. & Široký, J. Versatile AHU fault detection–Design, field validation and practical application. Energy and Buildings 237, 110781 (2021).

ASHRAE. ASHRAE Guideline 36-2021: High-Performance Sequences of Operation for HVAC Systems (2021).

Lu, X., Fu, Y., O’Neill, Z. & Wen, J. A holistic fault impact analysis of the high-performance sequences of operation for HVAC systems: Modelica-based case study in a medium-office building. Energy and Buildings 252, 111448 (2021).

Wen, J. & Li, S. Tools for evaluating fault detection and diagnostic methods for air-handling units. Report No. ASHRAE 1312-RP, (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers, 2011).

Chen, Y., Wen, J. & Lo, J. Using weather and schedule-based pattern matching and feature-based principal component analysis for whole building fault detection—Part I development of the method. Journal of Engineering for Sustainable Buildings and Cities 3, 011001 (2022).

Chen, Y. Data-driven Whole Building Fault Detection and Diagnosis. (Drexel University, 2019).

Wetter, M., Zuo, W., Nouidui, T. S. & Pang, X. Modelica buildings library. Journal of Building Performance Simulation 7, 253–270 (2014).

Li, G. et al. A hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testbed for cyber-physical energy systems in smart commercial buildings. Science and Technology for the Built Environment 30, 415–432 (2024).

DOE. Commercial Prototype Building Models https://www.energycodes.gov/prototype-building-models#Commercial.

EnergyPlus https://energyplus.net/.

ASHRAE. Sequences of Operation for Common HVAC Systems (2006).

Wetter, M., Hu, J., Grahovac, M., Eubanks, B. & Haves, P. in Building Performance Modeling Conference and SimBuild.

LBNL. Modelica Buildings Library https://simulationresearch.lbl.gov/modelica.

Fu, Y. et al. Modeling and evaluation of cyber-attacks on grid-interactive efficient buildings. Applied Energy 303, 117639 (2021).

ASHRAE. ASHRAE Guideline 36-2018: High performance sequences of operation for HVAC systems. (2018).

Pradhan, O. M. S. A Dynamic Bayesian Network Framework for Data-Driven Fault Diagnosis and Prognosis of Smart Building Systems. (Drexel University, 2023).

Yang, L., Braun, J. E. & Groll, E. A. The impact of fouling on the performance of filter–evaporator combinations. International journal of refrigeration 30, 489–498 (2007).

Cremaschi, L., Spitler, J. D., Lim, E. & Ramesh, A. Waterside fouling performance in brazed-plate-type condensers for cooling tower applications. HVAC&R Research 17, 198–217 (2011).

Chu, M., Lu, X., Fu, Y., O’Neill, Z. & Wen, J. in Proceedings of eSim 2022: 12th Conference of IBPSA-Canada (eSim, Vol. 12). IBPSA-Canada, Vancouver, Canada.

Tushar, W. et al. Internet of things for green building management: disruptive innovations through low-cost sensor technology and artificial intelligence. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 35, 100–110 (2018).

Peacock, M. Anomaly detection in bacnet/ip managed building automation systems (2019).

Roth, A. & Reyna, J. Grid-interactive efficient buildings technical report series: Whole-building controls, sensors, modeling, and analytics. Report No. DOE/GO-102019-5230, (US Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) 2019).

Li, G. et al. A critical review of cyber-physical security for building automation systems. Annual Reviews in Control 55, 237–254 (2023).

Fu, Y., O’Neill, Z. & Adetola, V. A flexible and generic functional mock-up unit based threat injection framework for grid-interactive efficient buildings: A case study in Modelica. Energy and Buildings 250, 111263 (2021).

O’Neill, Z. et al. Securing Grid-interactive Efficient Buildings (GEB) through Cyber Defense and Resilient System (CYDRES). (Texas A & M Univ., College Station, TX,United States., 2024).

Li, G. et al. CYDRES: CYber Defense and REsilient System for securing grid-interactive efficient buildings. Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings, Cities, and Transportation, 307–309 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Emulation and detection of physical faults and cyber-attacks on building energy systems through real-time hardware-in-the-loop experiments. Energy and Buildings, 114596 (2024).

Ghalamsiah, N. et al. Labeled Datasets for Air Handling Units Operating in Faulted and Fault-free States. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29297999 (2025).

OPENMODELICA (The Open Source Modelica Consortium (OSMC)).

BE-HVACR-Group. Modelica G36 Cyber Datasets Codes. GitHub https://github.com/BE-HVACR/Modelica_G36-Cyber_Datasets (2025).

Li, S. & Wen, J. Development and Validation of a Dynamic Air Handling Unit Model. ASHRAE Website, ASHRAE Bookstore In Partnership with Accuris https://store.accuristech.com/standards/or-10-007-rp-1312-development-and-validation-of-a-dynamic-air-handling-unit-model-part-i?product_id=1712375 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by funds from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) award under the grant number 2309030 entitled “PIRE: Building Decarbonization via AI-empowered District Heat Pump Systems”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Naghmeh Ghalamsiah led the overall data gathering effort and data comparison section, wrote the original manuscript, reviewed and edited the manuscript. Jin Wen curated and synthesized the RBC-ASHRAE1312 dataset and documented the data, guided the curation of other datasets, reviewed and edited the manuscript. Guowen Li curated and synthesized the G36-HIL and RBC-5wk datasets and documented the data, wrote the original manuscript, reviewed and edited the manuscript. Yimin Chen curated and synthesized the RBC-Nesbitt dataset and documented the data. Xing Lu curated and synthesized the G36-1wk dataset and documented the data. Yangyang Fu curated and synthesized the G36-Cyber dataset and documented the data. Mengyuan Chu curated and synthesized the G36-Degrad and G36-5wk datasets and documented the data. Zheng O’Neill supervised the curation, synthesizing, and documentation of RBC-5wk, G36-1wk, G36-5wk, G36-Degrad, G36-Cyber, G36-HIL datasets, reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghalamsiah, N., Wen, J., Li, G. et al. Labeled Datasets for Air Handling Units Operating in Faulted and Fault-free States. Sci Data 13, 15 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06179-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-06179-y