Abstract

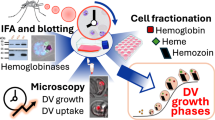

Bovine lactoferrin (bLF) is a 77 kDa glycoprotein that is abundant in bovine breast milk and exerts various bioactive functions, including antibacterial and antiviral functions. Few studies have explored bLF activity against parasites. We found that bLF affects hemozoin synthesis by binding to heme, inhibiting heme iron polymerization necessary for Plasmodium berghei ANKA survival in infected erythrocytes, and also binds to hemozoin, causing it to disassemble. In a challenge test, bLF administration inhibited the growth of murine malaria parasites compared to untreated group growth. To determine whether the iron content of bLF affects the inhibition of malaria growth, we tested bLFs containing different amounts of iron (apo-bLF, native-bLF, and holo-bLF), but found no significant difference in their effects. This indicated that the active sites were located within the bLFs themselves. Further studies showed that the C-lobe domain of bLF can inhibit hemozoin formation and the growth of P. berghei ANKA. Evaluation of pepsin degradation products of the C-lobe identified a 47-amino-acid section, C-1, as the smallest effective region that could inhibit hemozoin formation. This study highlights bLF’s potential as a novel therapeutic agent against malaria, underscoring the importance of its non-iron-dependent bioactive sites in combating parasite growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria, one of the world’s major infectious diseases, causes tremendous human suffering in subtropical and tropical regions, with 247 million infections and 619,000 deaths annually1. In particular, the spread of areas of infection south of the Sahara has become a major problem2. Malaria is transmitted by Plasmodium parasites, which enter the human body via bites from the Anopheles mosquito3. Preventive measures include the use of insecticide-treated bed nets and the administration of antimalarial drugs4,5. The choice of effective drugs is limited by the different morphologies of Plasmodium parasites in the infected host. No candidate with broad-spectrum efficacy in either form has been identified. In addition, studies have revealed the emergence of strains resistant to chloroquine (CHQ)6 and artemisinin (ART)7, representative and widely used antimalarial drugs. Meanwhile, many antimalarial drugs are poorly soluble in water, which can lead to higher doses required for drug efficacy and more severe side effects5,8. Therefore, the choice of drug to administer for treatment and the method of administration must be carefully considered9.

Against this background, for first-line treatment the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends combining artemisinin with other drugs (artemisinin combination therapy: ACT) rather than using it alone10. Although ACT is an effective strategy, the emergence of strains resistant to existing drugs used in ACT is increasing the geographical area where ACT is ineffective10. As a result, there is a constant need for new antimalarial drug candidates. Ideally, these candidates should have properties that make it difficult for drug resistance to emerge and have few side effects.

In the life cycle of Plasmodium species, in the human host, sporozoites from the salivary glands are first introduced subcutaneously via the bites of Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes. Subcutaneously injected sporozoites reach the liver and, after development and multiple hepatocyte divisions, differentiate into merozoites11. Merozoites are released into the bloodstream in large numbers and rapidly bind to and invade erythrocytes. The invading merozoites grow and divide, releasing many more merozoites. This cycle of merozoite invasion and release is repeated. During this cycle, the parasites digest hemoglobin, which is present in large quantities, as a source of nutrients for growth12. The heme iron released by the digestion of hemoglobin is toxic to the parasite13,14, so the parasite polymerizes heme into an insoluble crystalline form called hemozoin15,16. Many drugs, including CHQ, exert their medical effects by inhibiting this heme-to-hemozoin reaction17,18. Focusing on this metabolism, we screened our natural product extraction library for compounds that inhibit this reaction. We found that bovine lactoferrin (bLF), a protein found in milk, acts on heme iron and affects hemozoin formation.

bLF is a glycoprotein with a molecular weight of approximately 77 kDa found in bovine milk that belongs to the transferrin family. Many useful functions of bLF have been reported, including immunomodulatory ones19,20. It is particularly effective at killing pathogens and acts against a wide range of bacteria and viruses. bLF has two structurally unique symmetrical lobes (N-lobe, C-lobe), each of which can bind an iron atom21. It has strong iron-binding capacity, which contributes to eliminating bacterial pathogens. The surface of the N-lobe is positively charged and interacts directly with the surface structure of viruses and bacteria, inactivating pathogens in an iron-independent manner21. In addition, an antimicrobial peptide present in the N-lobe22 is produced during pepsin digestion of bLF in the gastrointestinal tract and has been shown to have anti-pathogenic potential superior to that of bLF. Although bLF is known to exhibit efficacy against numerous pathogens via multiple mechanisms, few reports on its effectiveness against parasites have been published. Nonetheless, the mechanism of action is known to be complex and to depend on the type of parasite21,23,24,25. The involvement of immunocompetent cells in this is also debated, for which clear evidence is still lacking.

In this study, bLF was found to have potential as an antimalarial drug by interacting with heme iron. We also found that bLF interacts with hemozoin. Existing antimalarial drugs do not exhibit this latter interaction, so we believe bLF has potential as a new type of drug. We also confirmed the inhibitory effect of bLF on the growth of malaria parasites through malaria infection experiments in a mouse model.

Result and discussion

Hemozoin inhibition and degradation of bovine lactoferrin

A hemozoin formation inhibition assay was used to assess bLF’s antimalarial activity. This assay exploits the difference in absorption wavelengths between heme (405 nm) and hemozoin (620 nm) and is easily performed in vitro. Heme spontaneously promotes hemozoin formation during incubation at 37 °C for 4 h with Tween-20. We investigated whether bLF inhibited this polymerization reaction. The degree of hemozoin polymerization (in hemozoin-forming units) was calculated using the formula provided in Fig. 1a. Milli-Q (MQ) water was a negative control. Hemozoin formation was observed from reaction initiation and increased consistently thereafter. In contrast, chloroquine (CHQ), an established antimalarial drug, inhibited hemozoin formation throughout the reaction. Meanwhile, bLF demonstrated a concentration-dependent ability to inhibit hemozoin formation. Notably, at concentrations lower than that of CHQ, bLF exhibited comparable or greater hemozoin-inhibiting ability (Fig. 1a).

bLF Effects on Hemozoin Formation, Heme Binding, and Hemozoin Degradation. (a) Inhibition of Hemozoin Formation by bLF. Differential Absorption of Heme (405 nm) and Hemozoin (620 nm) was calculated using the equation depicted in the figure and is denoted as the hemozoin formation unit. Measurements were conducted throughout 0–4 h. MQ acts as a negative control for hemozoin formation. CHQ represents 1 mM chloroquine, a positive control known for inhibiting hemozoin formation. bLF was tested at 0.5, 5, and 50 µM concentrations. All experiments were performed in triplicate. (b) Hem binding assay. The interaction between heme and bLF was examined through co-precipitation. Tubes display the samples pre and post-mixing, followed by centrifugation. The co-precipitate (complex) of heme and bLF is highlighted within the white dotted circle. (c) SDS-PAGE analysis of heme-bound lactoferrin. Sup represents the sample before mixing bLF and heme, while Ppt represents the precipitate formed after mixing bLF and heme and washing twice with PBS. The samples were treated with SDS buffer to release the bound proteins and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. The gel shows bands corresponding to bLF in the Ppt lanes, indicating that a significant amount of bLF is bound to heme. Duplicate lanes for both Sup and Ppt demonstrate the reproducibility of the results. (d) Hemozoin degradation by bLF. The degradation efficacy of hemozoin was evaluated by artificially synthesizing hemozoin in tubes, followed by bLF addition. After a 4-h degradation reaction, the tubes were inspected and documented. The contents were separated into supernatant (Sup.) and precipitate (Ppt.), with each examined microscopically. Magnifications were 200× for the supernatant and 400× for the precipitate. Undegraded hemozoin remain as a precipitate, similar to MQ. However, successful degradation results in a heme-derived brown color within the tube. The microscope field of view presents a representative image.

Lactoferrin is known to bind to various metal ions, notably iron26, including via potentially traditional and novel iron-binding sites26. Lactoferrin’s potential to bind heme has also been elucidated by assessing its interaction with various milk proteins27,28. In hemozoin inhibition assays, the pH tends to be acidic. To rule out that bLF binds heme exclusively under acidic conditions, we conducted a heme-binding assay under neutral conditions and confirmed bLF/heme iron binding. In this assay, we established conditions where neither bLF nor heme precipitates. However, when both are present, a precipitate forms (Fig. 1b), indicating a direct interaction between heme and bLF.

Furthermore, we have validated this interaction by thoroughly washing the precipitate and treating it with SDS buffer to release the bound proteins. Sup is the sample before mixing bLF and heme, and Ppt is the sample of the precipitate formed after mixing bLF and heme, which was washed twice with PBS. Subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis showed a band corresponding to bLF in the Ppt sample, indicating that a significant amount of bLF is indeed bound to heme. The amount of bLF released from the Ppt sample was almost equivalent to before binding (Fig. 1c). These results provide strong evidence for the direct binding of heme to lactoferrin. CHQ binds heme iron, inhibiting further polymerization by capping hemozoin polymer29, explaining its therapeutic efficacy. These observations led us to hypothesize that bLF binds to heme iron, preventing its polymerization into hemozoin.

Here, we also examined whether bLF acts on pre-formed hemozoin, rather than simply inhibiting its formation. Because hemozoin degradation releases heme, adversely affecting the malaria parasite, this could be an approach to combating malaria. We constructed a system for assaying hemozoin degradation via visual and microscopic observations. After hemozoin formation in tubes using Tween-20, test substance was added and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Both supernatant and precipitate were then visually and microscopically examined (Fig. 1d). For both MQ water and CHQ, no hemozoin degradation occurred; most hemozoin remained precipitated and the supernatant remained clear without heme-specific coloration. Microscopy revealed abundant hemozoin in the sediment. CHQ reportedly does not interact with hemozoin, in line with our findings30. Meanwhile, bLF exhibited degradative effects. The supernatant turned heme-like brown, and microscopic examination revealed degradation of supernatant-contained hemozoin into smaller, more delicate particles, which then dispersed into heme. Unlike in MQ water and CHQ, the sediment contained a little hemozoin, but these particles were noticeably smaller in size.

These results suggest that bLF interacts with both heme and hemozoin, displaying potential for antimalarial activity, while its medicinal properties may differ from those of CHQ. To further evaluate bLF’s antimalarial efficacy physiologically, we employed a rodent malaria infection model (Fig. 2).

Parasitemia of Plasmodium berghei infected mice. C57BL/6 mice were infected with P. berghei ANKA strain by intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 104 parasitized RBCs (pRBCs). At various time intervals post-infection, parasitemia were monitored by microscopy using Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. Percentage parasitemia was defined as the number of pRBCs out of the total number of RBCs multiplied by 100. (a) Protocol detailing parasite infection, bLF administration, and blood sampling. (b) Parasitemia in bLF-treated mice. Black squares on dotted line represent the PBS-treated group, black circles on the solid line represent the bLF-treated group. (c) Influence of various iron states in bLF (native, apo, holo) on parasitemia. The graph displays data from day 5 post-infection. %inhibition denotes the relative reduction in parasite growth compared to the PBS control. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS control, assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Rodent malaria challenge

Here, we employed the lethal Plasmodium berghei as a challenge parasite to assess bLF’s antimalarial activity. Mice were first infected on Day 0, followed by intraperitoneal administration of bLF at 20 mg per injection on Days 1 and 4 (Fig. 2a). Blood parasitemia levels were monitored under conditions where, without treatment, death would typically occur within a week. In the PBS-treated controls, parasitemia levels exceeded 8% within a week, leading to all mice dying. Meanwhile, in the bLF-treated group, trends towards inhibiting P. berghei growth were observed on Days 5 and 6, although these were not significant (Fig. 2b).

As bLF is an iron-binding protein involved in iron transport and considering iron’s physiological importance, we investigated whether bLF’s iron status influenced P. berghei growth. Following previous methods, we produced both apo- and holo-forms of bLF (Supplementary Fig. S1, Table S1). Malaria infection experiments were conducted using three bLF forms (native, apo, and holo) possessing distinct iron statuses (Fig. 2c). Here, parasitemia is represented by a box-and-whisker plot specifically highlighting Day 5 when inhibition of parasite proliferation was observed. Inhibitory efficacy was quantified as % inhibition, benchmarked against the infection rate for PBS: 25.2% for native bLF, 44.8% for apo-bLF, and 57.8% for holo-bLF. Differences compared with PBS-group findings achieved statistical significance for holo-bLF (P = 0.0158), a tendency for significance for apo-bLF (P = 0.0859), and no significance for native bLF (P = 0.3422). This suggests that the inhibitory efficiency increased with changes in iron status. Nevertheless, the difference between apo- and holo-forms was not significant, and no direct correlation between iron content and parasitemia was identified.

Inhibition of hemozoin formation or hemozoin degradation was also evaluated in the context of iron-related functionalities. The results demonstrated maintenance of both hemozoin formation inhibition and hemozoin degradation, irrespective of iron status (Supplementary Fig. S2). While no marked differences were evident, there were trends that these two capacities were enhanced for the apo-form over the holo-form. Notably, regarding hemozoin degradation, the precipitate exhibited a larger particle size in the holo-form, suggesting that iron status influences hemozoin-bLF interaction. To ascertain whether bLF’s capacity to inhibit hemozoin formation is linked to its iron-chelating ability, we assessed the inhibitory potential of the iron-chelating agents deferiprone (DFP) and deferoxamine (DFO) on hemozoin formation. We found that DFP and DFO cannot inhibit hemozoin formation. Furthermore, we evaluated the combined effects of in vitro mixing of bLF with DFP or bLF with DFO. DFP and DFO still did not inhibit hemozoin formation (data not shown), suggesting that mere chelating ability is insufficient to inhibit hemozoin formation.

The findings imply that, while bLF’s interaction with heme in vitro is modulated by its iron content, this has minimal influence on inhibiting malaria parasite growth in vivo. We deduce that bLF protein’s intrinsic properties are chiefly responsible for this growth-inhibitory effect.

Given that the protein’s functionality is intricately tied to its structural attributes, its tertiary conformation or primary structure is crucial. To further elucidate this, we examined transferrin family members (Fig. 3) and lactoferrin from another species, human (hLF) (Supplementary Fig. S3), to assess their roles in inhibiting hemozoin formation and promoting hemozoin degradation. In the broader transferrin family, beyond lactoferrin, we investigated hen egg transferrin (Otf), apo/holo-forms of bovine serum transferrin (bTF), and apo/holo-forms of human serum transferrin (hTF). Each examined transferrin type inhibited hemozoin formation. While both bLF and TF bind to heme, this potentially involves different mechanisms27,28, which may influence their respective capabilities.

Evaluation of the functional roles of various transferrin families (OTf, ovotransferrin, bTF (apo), bovine serum transferrin apo-form, bTF (holo), bovine serum transferrin holo-form, hTF (apo), human serum transferrin apo-form, hTF (holo), human serum transferrin holo-form: (a) inhibition of hemozoin formation, and (b) degradation of hemozoin. For (a), various transferrin was tested at 50 µM concentrations. All tests were conducted in triplicate. In (b), samples were standardized to a 50 µM concentration. The microscope field of view presents a representative image.

They were also able to degrade hemozoin (Fig. 3b). The differences between the apo- and holo-types varied in a transferrin species-dependent manner. Regarding hemozoin degradation, serum transferrin appeared less effective. The larger particle size of the precipitate suggested that serum transferrin might have reduced efficacy to degrade hemozoin. Besides bLF, hLF was also evaluated. While bLF strongly inhibited hemozoin formation, hLF exhibited weaker activity, which also decreased more rapidly (Supplementary Fig. S3). Similarly, hLF’s ability to degrade hemozoin was weaker than that of bLF, as evidenced by the aggregate size in the precipitate. These differences were despite high structural homology between hLF and bLF—69% identity and 92% similarity at the amino acid level. The isoelectric points (pI) of bLF and hLF are approximately 8.0 and 6.0, respectively. For hemozoin inhibition, the solution’s pH was 5.2, but was adjusted to 7.0 in the degradation analysis. Under these conditions, both bLF and hLF exhibited a positive charge in the inhibition environment, with that of bLF being significantly higher. Conversely, in the degrading environment, bLF retained a positive charge while hLF assumed a negative one. Such differences could significantly impact their functions. Considering the pI of other transferrins, those of OTf, bTF, and hTF are approximately 6.0, 6.8, and 5.231,32, respectively, which all differ from that of bLF. Thus, while pI differences may influence function, functional differences should not be solely due to pI, as hLF and OTf share the same pI but differ functionally.

bLF, a transferrin family member, stands out because of its superior functionality, despite high sequence and structural homology with other family members. Its distinctiveness is underscored by its multifunctionality, as evidenced by various studies. This multifunctionality may stem from lactoferrin’s structural composition, which includes both conserved domains and intrinsically disordered regions33.

Comparative analysis revealed that transferrin family members can both inhibit hemozoin formation and facilitate hemozoin degradation, to varying extents (Fig. 3). Despite structural similarity of up to 90% and 50%–70% amino acid sequence resemblance, the interaction with heme or hemozoin—a common function of transferrins—is influenced by primary sequence variations. Furthermore, the apo- and holo-forms of transferrins exhibit non-uniform conformational changes upon iron binding and release, which are significant and vary by transferrin type34,35. Thus, the specific structural regions interacting with heme or hemozoin, particularly the alterations induced by iron binding, may play critical roles in determining the functional efficiency of transferrin members.

Separation of N-lobe and C-lobe of bLF

Next, we dissected the structure of bLF to determine which regions are critical for heme binding. As previously mentioned, bLF is a member of the transferrin family and exhibits a lobe structure composed of two lobes: the N-lobe and the C-lobe, connected by a hinge region19. Each lobe is further subdivided into two domains: N1/N2 domains and C1/C2 domains (Fig. 4a)19. Lactoferrin’s multiple roles are attributed to the N-lobe23. Drawing upon existing literature36,37 describing the use of protease treatments to separate the lobes, we endeavored to isolate bLF’s N-lobe from the full-length protein.

Structural Overview and Purification of bLF C-Lobe. (a) Structural Overview of Lactoferrin: Lobe Configuration (N-lobe, C-lobe) and Constituent Domains (N-lobe including N1 domain (Green) and N2 domain (Red), C-lobe including C1 domain (Blue) and C2 domain (Light yellow)), hinge region (yellow). (b) 12.5% SDS-PAGE/CBB of tryptic degradation products of lactoferrin. M, molecular weight, lane 1: intact bLF, lane 2: trypsin-treated bLF. (c) CM cation-exchange chromatography was used to analyze the tryptic degradation products of lactoferrin. The unbound fraction, which did not adhere to the cation exchange resin and passed through as the unretained fraction, was subsequently subjected to size exclusion gel chromatography (d). The first peak in size exclusion gel chromatography was analyzed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE/CBB analysis, and a 37 kDa band was confirmed.

However, the purification process proved inefficient, with the desired level of separation not being achieved. Consequently, we shifted our focus to lactoferricin, a functional peptide found in the N-lobe of bLF reported to possess several beneficial properties38,39,40. Lactoferricin is situated within the N1 domain and is prominently located on the N-lobe’s surface.

We hypothesized that lactoferricin, given its location, might interact with heme and hemozoin, and proceeded to validate its functionality. Unexpectedly, lactoferricin inhibited neither hemozoin formation nor its degradation (Supplementary Fig. S4). Given the limited literature on the C-lobe’s functional properties compared with the extensive literature on the N-lobe, we shifted our focus to the C-lobe. In fact, recent findings have ascribed anti-inflammatory properties to this lobe34,41. Following the work of Nilisha et al.37, which demonstrated efficient C-lobe isolation through partial bLF digestion with trypsin, we employed a similar approach (Fig. 4b–d).

Upon partial digestion with trypsin, we observed four distinct degradation products on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4b). We identified a band at approximately 37 kDa, which we hypothesized to be the C-lobe. The C-lobe’s pI is 7.15, rendering it slightly negatively charged at pH 8.0. Leveraging this property, we conducted cation exchange chromatography using CM Sepharose at pH 8.0 As expected, the C-lobe did not bind to the resin and eluted in the flow-through (Fig. 4c). We subsequently subjected this flow-through fraction to gel filtration chromatography, resulting in target protein purification at approximating 37 kDa, which we confirmed as the C-lobe (Fig. 4d).

Antimalarial function of C-lobe

The isolated C-lobe was assessed for hemozoin formation inhibition and hemozoin degradation induction. The results indicated that, while the C-lobe was not as effective as bLF, it could inhibit hemozoin formation comparably to CHQ (Fig. 5a). Similarly, heme-binding assays showed that the C-lobe binds heme as well as bLF (Fig. 5b), we established conditions where neither bLF nor heme precipitates alone. However, when both are present, a precipitate forms, indicating a direct interaction between heme and bLF (Fig. 1b). Further validation showed that the C-lobe also forms a precipitate with heme under the same conditions, similar to bLF. These results provide strong evidence for the direct binding of heme to both bLF and the C-lobe. However, the C-lobe demonstrated diminished efficacy in hemozoin degradation compared with full-length bLF (Fig. 5c). hLF, known for its modest inhibition of hemozoin formation, similarly exhibited limited degradation potential (Supplementary Fig. S3). While the C-lobe retained its inhibitory potential against hemozoin formation, its capacity for hemozoin degradation was attenuated, implying partial overlap, but not complete congruence, of the binding sites of bLF for hemozoin and heme. Thus, we postulate that the C-lobe’s interaction with hemozoin is insufficient in isolation, emphasizing the significance of the entire bLF molecule in this interaction. This phenomenon is likely to be more related to the overall protein structure than primary sequence differences. We hypothesize that multiple molecules collaborate to achieve hemozoin degradation by encapsulating it.

Functional Roles of bLF C-Lobe: Inhibition of Hemozoin Formation, Heme Binding, and Hemozoin Degradation. Evaluation of the functional roles of bLF C-lobe: (a) inhibition of hemozoin formation, (b) heme binding, and (c) degradation of hemozoin of bLF C-lobe. For (a), samples were tested at 0.5, 5, and 50 µM concentrations. All tests were conducted in triplicate. In (b, c), samples were standardized to a 50 µM concentration. The co-precipitate (complex) of heme and bLF or C-lobe is highlighted within the black dotted circle. The microscope field of view presents a representative image.

After discovering the C-lobe’s ability to inhibit hemozoin formation, we performed a murine malaria infection test to assess its inhibition of malaria parasite growth. PBS treatment was used for a negative control, while bLF treatment served as a reference control. Given that the C-lobe has approximately half the molecular weight of bLF, the molarity of the C-lobe is doubled. Therefore, a double molar group (2 × mol) relative to the bLF-treated group was also evaluated to ensure a fair comparison (Fig. 6a).

Anti-malarial function of C-lobe with malaria challenge test. The malaria challenge was conducted as described in Fig. 2 legend. (a) Protocol detailing parasite infection, bLF administration, and blood sampling. (b) Parasitemia in samples-treated mice. Black squares on dotted line represent the PBS-treated group, black circles on the solid line represent the bLF-treated group, cross mark on dotted line represent the bLF (2 × mol), white circles on the solid line represent the C-lobe treated group. (c) The graph displays data from day 5 post-infection. %inhibition denotes the relative reduction in parasite growth compared to the PBS control. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS control, assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

As observed in the initial infection experiment, significant malaria parasite growth began from Day 4, with parasitemia increasing on Days 5 and 6 in the PBS group. Conversely, bLF consistently inhibited growth up to Days 4 and 5, but this effect diminished by Day 6. The C-lobe and the bLF (2 × mol)—matched for molarity with the C-lobe—demonstrated significant suppression of malaria parasite growth (Fig. 6b). Specifically, on Day 5, the %inhibition was 66.2%, 81.8%, and 78.5% for bLF, 2 × mol, and C-lobe groups, respectively (Fig. 6c). This emphasizes the pivotal role of the C-lobe in inhibiting parasite growth. These findings indicate that inhibiting hemozoin formation is crucial for suppressing malaria parasite growth. Furthermore, heme binding ability contributes more significantly than hemozoin degradation capacity.

Uncovering heme-binding regions within bLF’s C-lobe

Given the C-lobe’s demonstrated capacity to inhibit hemozoin formation, we conducted a detailed investigation into its heme-binding sites through a proteolytic degradation approach (Supplementary Fig. S5). Subjecting the C-lobe to pepsin yielded degradation products that, as verified by SDS-PAGE, exhibited a molecular weight under 10 kDa. Remarkably, subsequent evaluation of this degradation product’s capacity to inhibit hemozoin formation revealed that the proteolytically processed product at 50 µM maintained its inhibitory effect against hemozoin formation, mirroring the effects of 5 µM bLF and CHQ. However, diminished efficacy was noted at reduced concentrations. This suggests that, although a significant heme-binding domain may exist within the pepsin-digested C-lobe fragment, its efficacy is markedly less than that of both bLF and the intact C-lobe. As such, we hypothesized that the heme-binding domain alone may be insufficient for substantial hemozoin inhibition. We thus focused on regions within the pepsin degradation products that maintain secondary structure, particularly those on the C-lobe’s surface and in the hinge region. These regions were chosen for peptide synthesis, extending to encompass several amino acids flanking them. These sequences and their spatial orientation in the 3D structure and delineated in Fig. 7a, Supplementary Table S2.

Exploration of binding sites for C-lobes interacting with heme. (a) Regions on the bLF surface that retain their secondary structure, including fragments resulting from trypsin treatment, are designated as C-1a (red), C-1b (green), C-2 (blue), and hinge (yellow)., On the right, the molecular surface model (front and side) is described; (b) Assessment of the ability to inhibit hemozoin formation of various region derived C-lobe. various samples were tested at 50 µM concentrations. All tests were conducted in triplicate.

Various regions’ ability to inhibit hemozoin formation was evaluated, revealing that the C-1a region was as or more effective than CHQ; the C-1b region was initially as effective as CHQ, but this eventually attenuated (Fig. 7b). The C-1a region is located on the C-lobe’s N-terminal side and features a sheet-helix-sheet-helix arrangement. This area is prominently nestled within a substantial groove between N- and C-lobes (Fig. 7a, side view). We hypothesized that the C-1a region is crucial for heme binding and aimed to meticulously analyze this structure to identify the specific areas essential for heme interaction.

In the C-1a region, as illustrated by the ribbon model in Supplementary Fig. S6, structural elements were identified starting with the initial sheet designated as S1, followed by a helix labeled H1, another sheet termed S2, and concluding with a helix known as H2. From this secondary structure, we designed divided peptides, evaluated their ability to inhibit hemozoin formation (Supplementary Fig. S7), and calculated the inhibition ratio of hemozoin formation (Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, the truncated version of C-1a, S1H1S2, devoid of the final H2, exhibited virtually no functionality. In contrast, S1H1, excluding H2 and S2, demonstrated some functionality. While both S1 and H1 individually displayed potential, both S1H1S2 and H1S2H2 had limited function. This suggests that S1 or H1 does not guarantee functionality, establishing that the full-length C-1a structure is the critical minimum for heme interaction.

Previously identified functional regions of the C-lobe include an antimicrobial peptide in the C2 domain and an antiviral peptide in the loop region of the C1 domain34,42. However, the region discovered here does not match any of these regions and could be novel. The C-1a region, the smallest region required for heme binding as determined here, is thought to bind heme and thereby inhibit π-π binding, which is vital for heme polymerization. In addition to its role in inhibiting hemozoin formation, we also explored bLF’s involvement in hemozoin degradation. Our findings suggest that hemozoin binding is not solely attributable to the C-1a region. Instead, multiple bLF molecules may be involved in degradation via C-1a and other potential binding sites. This is supported by the observed attenuation of the C-lobe in hemozoin degradation (Fig. 5c).

Furthermore, our investigation into hemozoin degradation in the transferrin family (Fig. 3) indicated that conformational changes in the protein influence its degradation capacity. Rather than a precise interaction between the heme and the protein binding site, this suggests dynamic activity throughout the entire molecule. While bLF typically binds two iron molecules per molecule, under specific conditions it can associate with over 70 iron molecules per molecule (FeLf)26. FeLf forms a micelle-like structure, where Lf is interconnected across multiple layers by iron and bicarbonate ions26. Concerning hemozoin interaction, we postulate that several lactoferrins might employ the heme iron binding site to construct giant micelles encircling hemozoin, thus breaking down the insoluble hemozoin and converting it into heme.

Docking and molecular dynamics simulations to explore heme binding in specific proteins

To confirm how heme binds to the C-1a region, we performed docking simulations using the structures of heme, bLF, and two transferrin proteins (OTf, hLF) for which crystal structures have already been determined. The top five of 300 heme and various transferrin (bLF, OTf, and hLF) binding poses obtained by the calculations are shown in Fig. 8. bLF had two top five poses interacting with the C-1a region as a heme-binding region (Fig. 8a). The remaining two were located in a groove near the hinge region opposite the C-1a region, with the last one predicted to bind to the N-2 domain in the N-lobe. The calculations suggest that the bLF C-1a region is not the only binding site, and multiple potential binding sites exist. Expanding on the interaction of heme with C-1a, it was found to interact with the last helix (H2) of the C-1a region, which did not function in inhibiting hemozoin formation (Supplementary Fig. S6, Table S3). This suggests that the C-1a region’s three-dimensional structure is essential and constitutes a space pocket suitable for heme binding. In two binding poses (Fig. 8b, c), it is observed that heme interacts with charged amino acids (Glu388, Asp315, Asp379, or Lys386) in the C-1a region, suggesting its binding to C-1a. However, interactions with surrounding regions outside C-1a result in heme being positioned within the spatial pocket between the C-lobe and N-lobe. This positioning of heme correlates with a higher capacity to inhibit hemozoin formation associated with bLF or the C-lobe compared with C-1a. Therefore, while the C-1a region is crucial for heme binding, the surrounding environment is also important in exerting the final inhibitory effect.

Docking simulation of heme and various transferrin family (bLF, OTf, and hLF). (a) Top 5 predicted binding poses of bLF (PDB: 1BLF) to heme, showing the C-1a region in red. (b, c) Magnified view of the two poses that bind to the C-1a region, with the amino acids interacting with the ligand on the right and the region's surface where the ligand interacts with the receptor on the bottom. Top 5 poses predicted to bind heme and (d) OTf (PDB:1OVT, 1AIV), or (e) hLF (PDB:1LFG, 1CB6), and C-1a homology regions are shown in red. (f) Multiple sequence alignment of the C-1a region among bLF, hLF, OTf, and bTF. The analysis reveals high sequence similarity, indicating a structurally conserved region, suggesting that transferrins possessing the C-1a region have the potential to bind heme.

Next, calculations were also performed for OTf (native: 1OVT, apo: 1AIV), a transferrin family member whose conformation has been determined and retains the function of inhibiting hemozoin formation. The results showed that, in native OTf, one of the top five poses could bind to the C-1a homology region; in the Apo OTf, four of the top five poses interacted with the C-1a homology region, one of which also interacted with the hinge region. Here, we exclusively assessed the inhibitory potential of native OTf on hemozoin formation. Although slightly weaker than that of bLF, native OTf demonstrated comparable efficacy (Fig. 3). We attribute this functionality to heme binding within a structural domain similar to the C-1a homologous region in OTf, as seen with bLF. Furthermore, in the Apo form, as opposed to the native state, enhanced binding to the C-1a homologous region may occur. Thus, evaluating the Apo form’s capacity to inhibit hemozoin formation may yield functionality superior to that of bLF.

Calculations were then conducted for hLF, which exhibits lower capacity to inhibit hemozoin formation than bLF (Supplementary Fig. S3). hLF exists in both apo- and holo-type conformations, and calculations using these structures (holo: 1LFG, apo: 1CB6) revealed that heme did not bind to the region homologous to C-1a.

In the calculated poses involving heme binding, interaction with Glu388, located at the C-1a region’s end, was consistently observed. However, despite hLF also possessing Glu388, calculations for hLF revealed no heme binding near the C-1a region. These findings suggest that, while the presence of charged amino acids in the C-1a region contributes to heme binding, the overall structural characteristics, including the surrounding environmental context, play crucial roles in determining the final heme-binding capacity.

The findings from Fig. 3 imply that, while bLF’s interaction with heme in vitro is modulated by its iron content, this has minimal influence on inhibiting malaria parasite growth in vivo. We deduce that bLF protein’s intrinsic properties are chiefly responsible for this growth-inhibitory effect. Given that the protein’s functionality is intricately tied to its structural attributes, its tertiary conformation or primary structure is crucial. Comparative analysis revealed that transferrin family members can both inhibit hemozoin formation and facilitate hemozoin degradation, to varying extents (Fig. 3). Despite structural similarity of up to 90% and 50%–70% amino acid sequence resemblance, the interaction with heme or hemozoin—a common function of transferrins—is influenced by primary sequence variations.

We also performed multiple sequence alignments to determine the sequence similarity and differences in conserved regions between these transferrins. The analysis revealed that the C-1a region has high sequence similarity among bLF, hLF, OTf, and bTF, indicating a structurally conserved region (Fig. 8g). This suggests that transferrins possessing the C-1a region have the potential to bind heme. However, the differences in the interaction with heme are likely due to the overall conformational differences of the molecules, significantly influenced by the iron content of the transferrins. Our study suggests that bLF has an optimal conformation for heme binding and retention, which may explain its superior heme-binding capacity.

Furthermore, we conducted molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for bLF to support our docking studies. The MD simulation results showed that heme remains stably bound to the C-1a region of bLF throughout the simulation, supporting the docking results (see Supplemental Video Files 1 and 2). These findings suggest that the heme-lactoferrin interaction is stable and corroborates the docking simulation results.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that bLF can engage with heme and hemozoin, suppressing malaria parasite growth upon in vivo administration. For this therapeutic effect to manifest, human erythrocytes must internalize bLF via lactoferrin receptors (LR)43.

Infection experiments suggest that mice possess analogous receptors, facilitating bLF uptake by infected erythrocytes. Furthermore, studies indicate that oxidants and metal ions can modulate the binding affinity of erythrocyte LR43. This shift in affinity is also influenced by the status of metal ions bound to lactoferrin43, potentially accounting for the observed reduction in parasitemia by bLF(apo) and bLF(holo) (Fig. 2c).

Another potential mechanism entails a direct interaction between lactoferrin and blood-borne parasites. Prior in vitro studies demonstrated that LF damages erythrocyte membranes, impeding growth through injury to both erythrocyte and parasite membranes44. This is believed to stem from the ROS generation by iron attached to lactoferrin44. Under such circumstances, primarily the holo-lactoferrin would function, aligning with observations that holo-bLF was more effective in curtailing parasitemia. Nonetheless, in this study, the difference from apo-bLF was not statistically significant.

Furthermore, current antimalarial medications are low-molecular-weight entities, whereas bLF is a biomacromolecule that is broken down in the body, anticipated to exhibit a brief half-life in blood. This would necessitate frequent dosing to curtail malaria parasite growth, but complete parasite eradication remains elusive. Upon discerning the precise uptake and metabolism of bLF by erythrocytes, more refined strategies for bLF administration and its drug formulation at the point of delivery can be devised. LF encapsulation in acid-resistant, enteric-soluble capsules has been explored to augment its transport efficiency and strategies for macromolecular protectant binding45. The fusion of hLF with the Fc region of Ig to extend its half-life in blood has also been documented46. This research identified the C-lobe, notably the C-1a region, as a pivotal segment for inhibiting malaria parasite growth in bLF. Given that they are smaller than bLF as a whole, these regions could also diminish immune system clearance. Coupled with the abovementioned strategies, this knowledge paves the way for innovative drug designs centered on the C-lobe and C-1a regions.

Methods

Reagents

bLF was obtained from Morinaga (Tokyo, Japan) or purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Chloroquine diphosphate (CHQ), ovotransferrin, and lactoferricin B were purchased from Wako. Hemin chloride, human lactoferrin, bovine transferrin (apo and holo), human transferrin (apo and holo), and other basic reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Japan. All of the various peptides used in the experiments were chemically synthesized by Scrum Inc. (Osaka, Japan).

Apo- and holo-bLF

Apo-bLF and holo-bLF were produced in accordance with previously reported methods47. To calculate the iron binding ratio, the amount of protein in apo- and holo-bLF prepared as described above was quantified using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). The iron content was determined using Test-Waco (Wako), and the binding molar ratio was calculated by dividing the iron concentration by the protein concentration. The results of iron saturation of the prepared apo- and holo-bLF are shown in Supplementary Table S1. In this study, native bLF, which contains its natural iron content, and apo-bLF, which was prepared by reducing the iron content through dialysis, were used. Additionally, holo-bLF, which was prepared by increasing the iron content through dialysis, was also used. These samples' iron content and preparation methods are detailed in the Methods section, Supplementary Table S1, and Figure S1 (powder and liquid forms).

Purification of C-lobe

bLF was partially digested with trypsin in accordance with the method of Nilisha et al.37, which was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. After stopping the degradation reaction, the products partially degraded by trypsin were applied to a CM cation exchange column (HiTrapCM, FF; GE Healthcare, IL, USA) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0). The column-unbound and -bound fractions were collected, the former of which was then subjected to Superdex 200 pg gel filtration chromatography using ÄKTA Prime Plus (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) (flow rate: 0.8 ml/min, fraction size: 1 mL). The first eluting peak obtained by gel filtration chromatography (identified by SDS-PAGE analysis as Fig. 4d, 37 kDa band corresponding to the C-lobe) was fractionated. Next, the fraction was dialyzed to replace the solvent with ultrapure water and lyophilized to a powder, designated the bLF C-lobe.

Hemozoin inhibition assay

To assess the inhibition of hemozoin formation, a slightly modified version of a procedure previously reported by Nguyen et al.48 was used. In this method, Tween-20 is used as an inducer for the polymerization of hemin to hemozoin. To each well of a 96-well plate (Non-treated 96 well/Flat Bottom; Iwaki, Osaka, Japan), 20 µL/well of 200 mM H2SO4 and 50 µL/well of 200 µM heme solution were added. Each test sample was then added in an appropriate volume (20 to 80 µL) and diluted with ultrapure water to a total volume of 150 µL/well. Then, 50 µL of Tween-20 (0.048 g/L, immediately before use) was added (total 200 µL) and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The absorbance peak at 405 nm, the most prominent peak for heme, and the peak at 620 nm, whose intensity was increased by hemozoin formation, were measured over time during the 4-h incubation. The proportions of heme and hemozoin in the solution were calculated by subtracting the absorbance at each reaction time point (1, 2, 3, 4 h) from the absorbance at the start of the reaction (0 h) and are expressed as the rate of hemozoin formation, as shown by the formula in Fig. 1. In this assay, effective inhibition of hemozoin formation results in absorbance values that are lower, potentially even negative, similar to those observed with the positive control (CHQ, 1 mM). Such values are indicative of significant inhibitory activity.

Evaluation of the inhibition of hemozoin formation requires multiple plates, given that the assay does not support concurrent testing of numerous samples on a single plate. To account for inter-plate discrepancies, results across experiments were adjusted using the efficacy of CHQ, expressed as the percentage inhibition of hemozoin formation.

Heme binding assay

To assess the binding affinity of various samples to heme iron, 50 µL of heme (final 50 µM) and 20 µL of the sample (final 50 µM) were introduced into a tube. The volume was then brought up to 200 µL using MQ water. After thorough mixing, the solution was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. Visual inspection was then performed to identify the presence of any precipitate in the microtubes after centrifugation. A visible precipitate suggested successful binding, whereas its absence and a persistent brown coloration, characteristic of heme iron, indicated no binding activity. Additionally, to further validate the binding interaction, the precipitate was thoroughly washed twice with PBS to remove any unbound heme or protein. The washed precipitate was then treated with SDS buffer to release the bound proteins. The samples were subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis.

Hemozoin degradation assay

In the microtubes, 60 µL/tube of 200 mM H2SO4, 150 µL/tube of 1.5 mM heme solution, 150 µL of Tween-20 (0.08 g/L, immediately before use), and 240 µL of ultrapure water (total 600 µL/tube, for one sample) were added to the hemozoin preparation. After preparation, hemozoin was generated by incubation at 37 °C overnight. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and removed. The resulting precipitate (hemozoin) was suspended in 540 µL of Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.4). A further 60 µL of each sample was added, giving 600 µL of reaction solution. After incubation of the reaction solutions at 37 °C for 4 h, the degree of hemozoin degradation was assessed by visual observation of the microtubes and observation of the supernatant and precipitate of the reaction solutions with a light microscope (20× or 40× magnifications).

Mice, pathogen administration, and parasitemia

All animal care and experiments were approved by Kitasato University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval Number: 20-116), and all experiments including animal subjects were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE-guidelines 2.0 and the Guidelines of Animal Experiments of Kitasato University. Mice were anesthetized using a combination of three anesthetic agents (e.g., medetomidine, midazolam, and butorphanol) before being humanely sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

Plasmodium berghei (ANKA strain) was raised from frozen stock and maintained by serial passage in Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice (Charles River Laboratories Japan Inc., Yokohama, Japan). Ten thousand P. berghei were administered intraperitoneally to 6-week-old C57BL/6 male mice (Charles River Laboratories Japan Inc.). Three mice were used in each group, and these experiments were repeated two to three times. The presented data are representative of these multiple experiments. A total of 200 μL of native bLF, apo-bLF, holo-bLF, C-lobe domain of bLF, or PBS (negative control) was administered intraperitoneally at Days 1 and 4 after infection. Parasitemia was measured daily using blood smears with Giemsa staining. Mann–Whitney U test was used for statistical analysis (p < 0.05).

Pepsin degradation of C-lobe

A 5% aqueous solution was prepared using 5 mg of purified C-lobe and adjusted to pH 2.5 with 1N HCl. Subsequently, 10 µL of pepsin (0.52 mg/mL) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, with reference to the report by Tomita et al.38. The enzymatic reaction was then terminated by heating at 80 °C for 2 min, followed by ice-cooling. The reaction products were subjected to 12.5% Tris-Tricin SDS-PAGE to determine the degradation efficiency, and these were used as C-lobe pepsin degradation products for analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

Sequence and structural homology analysis

Sequences for different lactoferrins (LF) and transferrins (TF) were obtained from the NCBI GenBank database using the following accession IDs: bovine lactoferrin (bLF: NP_851341), human lactoferrin (hLF: 1LFG_A), ovotransferrin (OTf: CAA26040), bovine transferrin (bTF: NP_803450), and human transferrin (hTF: NP_001054.2). These sequences were analyzed using Genetyx software (Genetyx-MAC ver. 22.0.4, GENETYX Corporation) to calculate sequence similarity. Additionally, structural homology was assessed using the Phyre2.0 web service (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index).

Docking simulation

The crystal structure of bLF (PDB: 1BLF), OTf (PDB: 1OVT, 1AIV), and hLF (PDB: 1LFG, 1CB6) were used in this study. The obtained structure was optimized using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE version 2022, Chemical Computing Group) for docking simulations. The structure of the ligand (heme) was generated with chemdraw and optimized using MOE. Compound docking analysis was performed using the MOE-Dock program. The force field was applied using MMFF94, targeting the entire molecule, including known pockets. The binding methodology was adapted to fix the receptor, and the ligand could move upon binding. As for docking assessments, 300 candidate docking poses were generated and evaluated using the London dG score (E-score, kcal/mol), which estimates the binding free energy of the ligand from a given pose, to filter them down to the top five poses.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

We conducted MD simulations for bLF/heme to further validate the docking results using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE version 2022, Chemical Computing Group). The initial structure of the bLF/heme complex was taken from the top docking pose. The system was solvated in water, and the AMBER force field was used for the protein and heme. Energy minimization was performed to remove any bad contacts, followed by a 100 ps–10 ns equilibration run at 300 K. Finally, a production MD simulation was run for 100 ps under the same conditions. The time step was set to 2 fs, and all bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, and a cutoff of 12 Å was applied for van der Waals interactions. Trajectory analysis was performed using the MD Player tool included in MOE. All other settings and parameters were as per the default configurations provided by MOE.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [M.T.], upon reasonable request.

References

WHO. World malaria report 2022 https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022.

White, N. J. Severe malaria. Malar. J. 21, 284 (2022).

Cowman, A. F., Berry, D. & Baum, J. The cellular and molecular basis for malaria parasite invasion of the human red blood cell. J. Cell Biol. 198, 961–971 (2012).

Mosqueira, B. et al. Efficacy of an insecticide paint against malaria vectors and nuisance in West Africa–part 2: Field evaluation. Malar. J. 9, 341 (2010).

Birkholtz, L. M., Alano, P. & Leroy, D. Transmission-blocking drugs for malaria elimination. Trends Parasitol. 38, 390–403 (2022).

Fidock, D. A. et al. Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol. Cell. 6, 861–871 (2000).

Le Bras, J. & Durand, R. The mechanisms of resistance to antimalarial drugs in Plasmodium falciparum. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 17, 147–153 (2003).

Memvanga, P. B. & Nkanga, C. I. Liposomes for malaria management: the evolution from 1980 to 2020. Malar. J. 20, 327 (2021).

Saadeh, K., Nantha Kumar, N., Fazmin, I. T., Edling, C. E. & Jeevaratnam, K. Anti-malarial drugs: Mechanisms underlying their proarrhythmic effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 179, 5237–5258 (2022).

Ashley, E. A., Pyae-Phyo, A. & Woodrow, C. J. Malaria. Lancet. 391, 1608–1621 (2018).

Meibalan, E. & Marti, M. Biology of malaria transmission. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 7, 1–15 (2017).

Counihan, N. A., Modak, J. K. & de Koning-Ward, T. F. How malaria parasites acquire nutrients from their host. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9, 649184 (2021).

Wunderlich, J., Rohrbach, P. & Dalton, J. P. The malaria digestive vacuole. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 4, 1424–1448 (2012).

Tripathy, S. & Roy, S. Redox sensing and signaling by malaria parasite in vertebrate host. J. Basic Microbiol. 55, 1053–1063 (2015).

Hempelmann, E. & Egan, T. J. Pigment biocrystallization in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 18, 11 (2002).

Rosenthal, P. J. & Meshnick, S. R. Hemoglobin catabolism and iron utilization by malaria parasites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 83, 131–139 (1996).

Padmanaban, G. & Rangarajan, P. N. Heme metabolism of Plasmodium is a major antimalarial target. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268, 665–668 (2000).

Slater, A. F. Chloroquine: mechanism of drug action and resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Pharmacol. Ther. 57, 203–235 (1993).

Rosa, L., Cutone, A., Lepanto, M. S., Paesano, R. & Valenti, P. Lactoferrin: A natural glycoprotein involved in iron and inflammatory homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1–26 (2017).

Moreno-Exposito, L. et al. Multifunctional capacity and therapeutic potential of lactoferrin. Life Sci. 195, 61–64 (2018).

Drago-Serrano, M. E., Campos-Rodriguez, R., Carrero, J. C. & de la Garza, M. Lactoferrin: Balancing ups and downs of inflammation due to microbial infections. Int J Mol Sci. 18, 1–25 (2017).

Ahmadinia, K., Yan, D., Ellman, M. & Im, H. J. The anti-catabolic role of bovine lactoferricin in cartilage. Biomol Concepts. 4, 495–500 (2013).

Zarzosa-Moreno, D. et al. Lactoferrin and its derived peptides: An alternative for combating virulence mechanisms developed by pathogens. Molecules. 25, 1–48 (2020).

Anand, N., Kanwar, R. K., Sehgal, R. & Kanwar, J. R. Antiparasitic and immunomodulatory potential of oral nanocapsules encapsulated lactoferrin protein against Plasmodium berghei. Nanomedicine (Lond). 11, 47–62 (2016).

Anand, N. Antiparasitic activity of the iron-containing milk protein lactoferrin and its potential derivatives against human intestinal and blood parasites. Front. Parasitol. 2, 1–14 (2024).

Hu, F. et al. Studies of the structure of multiferric ion-bound lactoferrin: A new antianemic edible material. International Dairy Journal. 18, 1051–1056 (2008).

Orino, K. Heme-binding ability of bovine milk proteins. Biometals. 33, 287–291 (2020).

Saito, N., Iio, T., Yoshikawa, Y., Ohtsuka, H. & Orino, K. Heme-binding of bovine lactoferrin: The potential presence of a heme-binding capacity in an ancestral transferrin gene. Biometals. 31, 131–138 (2018).

Sullivan, D. J. Jr., Gluzman, I. Y., Russell, D. G. & Goldberg, D. E. On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine’s antimalarial action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 11865–11870 (1996).

Fitch, C. D. & Kanjananggulpan, P. The state of ferriprotoporphyrin IX in malaria pigment. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 15552–15555 (1987).

Wu, J. & Acero-Lopez, A. Ovotransferrin: Structure, bioactivities, and preparation. Food Res Int. 46, 480–487 (2012).

Petren, S. & Vesterberg, O. The N-acetylneuraminic acid content of five forms of human transferrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 994, 161–165 (1989).

Albar, A. H., Almehdar, H. A., Uversky, V. N. & Redwan, E. M. Structural heterogeneity and multifunctionality of lactoferrin. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 15, 778–797 (2014).

Sharma, S., Sinha, M., Kaushik, S., Kaur, P. & Singh, T. P. C-lobe of lactoferrin: the whole story of the half-molecule. Biochem Res Int. 2013, 271641 (2013).

Anderson, B. F., Baker, H. M., Norris, G. E., Rumball, S. V. & Baker, E. N. Apolactoferrin structure demonstrates ligand-induced conformational change in transferrins. Nature. 344, 784–787 (1990).

Sharma, S., Singh, T. P. & Bhatia, K. L. Preparation and characterization of the N and C monoferric lobes of buffalo lactoferrin produced by proteolysis using proteinase K. J. Dairy Res. 66, 81–90 (1999).

Rastogi, N. et al. Preparation and antimicrobial action of three tryptic digested functional molecules of bovine lactoferrin. PLoS ONE. 9, e90011 (2014).

Tomita, M. et al. Potent antibacterial peptides generated by pepsin digestion of bovine lactoferrin. J. Dairy Sci. 74, 4137–4142 (1991).

Wakabayashi, H., Takase, M. & Tomita, M. Lactoferricin derived from milk protein lactoferrin. Curr. Pharm. Des. 9, 1277–1287 (2003).

Gifford, J. L., Hunter, H. N. & Vogel, H. J. Lactoferricin: a lactoferrin-derived peptide with antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor and immunological properties. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 2588–2598 (2005).

Ashby, B., Garrett, Q. & Willcox, M. Bovine lactoferrin structures promoting corneal epithelial wound healing in vitro. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 2719–2726 (2011).

Mir, R. et al. The structural basis for the prevention of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal tract damage by the C-lobe of bovine colostrum lactoferrin. Biophys. J. 97, 3178–3186 (2009).

Taleva, B., Maneva, A. & Sirakov, L. Essential metal ions alter the lactoferrin binding to the erythrocyte plasma membrane receptors. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 68, 13–24 (1999).

Fritsch, G., Sawatzki, G., Treumer, J., Jung, A. & Spira, D. T. Plasmodium falciparum: inhibition in vitro with lactoferrin, desferriferrithiocin, and desferricrocin. Exp. Parasitol. 63, 1–9 (1987).

Ono, T. et al. Potent anti-obesity effect of enteric-coated lactoferrin: decrease in visceral fat accumulation in Japanese men and women with abdominal obesity after 8-week administration of enteric-coated lactoferrin tablets. Br. J. Nutr. 104, 1688–1695 (2010).

Shiga, Y. et al. Hinge-deficient IgG1 Fc fusion: Application to human lactoferrin. Mol Pharm. 14, 3025–3035 (2017).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Effect of iron saturation level of lactoferrin on osteogenic activity in vitro and in vivo. J. Dairy Sci. 96, 33–39 (2013).

Huy, N. T. et al. Simple colorimetric inhibition assay of heme crystallization for high-throughput screening of antimalarial compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 350–353 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 17H04073, 24K01933. We also thank Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O. conducted experiments related to purification. M.K., M.G., T.K., and M.M. primarily performed biochemical experiments. A.H. conducted animal experiments. K.S., D.H., and H.I. contributed to valuable discussions regarding the manuscript. K.K. conducted animal experiments and wrote the main manuscript text. T.K. conducted MD simulation analysis. H.I. and T.M. contributed to manuscript writing and overall organization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Obayashi, M., Kimura, M., Haraguchi, A. et al. Bovine lactoferrin inhibits Plasmodium berghei growth by binding to heme. Sci Rep 14, 20344 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70840-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70840-6