Abstract

In this study, stochastic multi-objective allocation of wind turbines (WTs) in radial distribution networks is performed using a new multi-objective improved horse herd optimizer (MOIHHO) and an unscented transformation (UT) method for modeling the uncertainties of WTs power and network load. The objective function aims to minimize power loss, improve reliability, and reduce the costs associated with wind turbines (WTs), presenting these goals as a three-dimensional function. The Multi-Objective Improved Horse Herd Optimizer (MOIHHO) is derived from an enhanced version of the traditional horse herd optimizer. This enhancement utilizes mirror imaging based on convex lens principles to address issues of premature convergence. Additionally, the decision-making process is designed to identify the final fuzzy solution among the non-dominant solutions within the Pareto front set. The simulation results are presented with and without considering uncertainty in two scenarios of deterministic and stochastic WT allocation on 33- and 69-bus distribution networks and different objectives are compared. Also, the effect of incorporating uncertainties are evaluated on power loss and reliability using the MOIHHO. Moreover, the superiority of the MOIHHO is investigated in achieving better objective function value compared with conventional MOHHO, multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOSPO), multi-objective gray wolf optimizer (MOGWO), and multi-objective gazelle optimization algorithm (MOGOA). The obtained results demonstrated that considering the UT-based stochastic scenario, the power losses cost is increased, and the reliability is weakened for 33- and 69-bus networks in comparison with the deterministic scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation and background

In comparison to low-current transmission, line power losses in distribution networks are greater because of high electrical current as well as low voltage; this results in increased energy costs and deteriorating voltage features1. These inevitable losses pose a significant obstacle to the network’s successful operation. Therefore, minimizing power losses is a critical concern for numerous power companies worldwide2. Several approaches can be employed to mitigate line losses, among which distributed generations (DGs) stand out as one of the most prevalent3. In recent years, there has been a noticeable surge in the worldwide adoption of renewable energy sources, driven by the imperative to safeguard the environment and also promote environmental sustainability. Wind (WT) and other renewable energy-based distributed energy sources4 are advantageous solutions for meeting the rising load demand at a low energy cost. Wind energy-based power production is expanding at an accelerated rate on a global scale. Depending on WT technology, the incorporation of wind-based DG into power infrastructures results in a distinct penetration level4. A greater degree of network penetration may result in atypical conduct, including significant power outages and voltage fluctuations5. Nevertheless, the optimal distribution of WT ensures that the network operates at its intended level of penetration during typical business hours. However, modifying the intrinsic power of these sources presents a significant obstacle to the efficient and economical functioning of the power network6. The presence of unpredictability in input data presents network administrators, investors, and decision-makers with substantial obstacles and operational challenges7,8. To solve the issue of the allocation of WT resources in the electricity distribution network, it is thus essential to account for uncertainties.

Related works and research gaps

Various studies have investigated the allocating the renewable energy sources in radial distribution networks incorporating different objectives, optimization methods, and deterministic and stochastic approaches. The grey wolf-teaching learning method, a fuzzy decision-making-based multi-objective evolutionary method described in9, is designed to optimize the allocation of the WTs in distribution networks to decrease losses and enhance reliability. For the allocation of distributed generation (DGs)10, proposes a cost-benefit method based on reduced power acquired and anticipated disruption cost of the distribution network. The approach utilizes a hybrid particle swarm optimization and gravitational search algorithm (PSOGSA). The ant lion optimizer (ALO) is utilized in11 for allocation of WTs in networks to minimize the losses and improve voltage conditions. Convergent barnacles mating optimizer, a single-objective optimization problem described in12, is implemented for stochastic scheduling of renewable generation and appropriate storage system management. A cost-minimizing objective is established in13 to employ an analytical approach to reduce the expenses associated with power loss, DG installation, operation, and maintenance, as well as power derived from the post for DG placement and sizing. An approach for dynamic network reconfiguration utilizing a wild goats algorithm (WGA) and exchange market al.gorithm (EMA) hybrid is described in14. The reconfiguration issue is adequately mitigated and power quality is improved via the utilization of the ALO, as proposed in15. MPSO is suggested as a method for network reconfiguration and allocating the DG in16. The non-dominated arranging genetic algorithm-II is utilized in17 to generate the Pareto solution set for the optimal sitting and sizing of the renewable resources, considering consideration the dispersion percentage and energy supplementing linked characteristic. The DGs allocation in distribution networks for reducing power loss and voltage deviation via the PSO and grasshopper optimization algorithm (GOA) is described in18. In19, a multi-objective optimization structure is presented to allocate the PVs in distribution networks considering seasonal and hourly variation of PV generation to minimize the unbalance factor, and power loss, and also voltage security improvement via a modified grey-wolf optimizer (MGWO). To maximize the promotion effect of renewable energy policies, in20 the optima allocation of PVs, WTs, and energy storage is established in distribution network incorporating several policy objectives using a NSGA-II‐PSO method. To improve the voltage stability margin21, presents a novel structure according to the multi-objective artificial hummingbird algorithm (MOAHA) for the best utilization and scaling of renewable resources, as well as an efficient energy storage operation strategy. The authors of22 employ turbulent flow of water-based optimization (TFWO) to optimize the placement and planning of WTs in a distribution network with aim of minimizing the production costs, enhance reliability, and reduce losses in response to variations in load consumption behavior throughout the COVID-19 conditions. In23, the authors propose a solution to the distribution network scheduling issue that addresses flicker generated by WTs. This solution takes into account power quality concerns and employs the crow search algorithm (CSA) to minimize losses, flicker emission, and voltage deviation. A Weibull distribution function derived from a probabilistic model is introduced in reference5 to facilitate the optimal sitting and sizing of the WTs utilizing the PSO. An optimized WTs allocation in distribution networks is executed in24 using an enhanced Salp swarm algorithm (ISSA) to decrease power loss costs and enhance network dependability. A structure for optimally placing and scaling WTs in distribution networks is presented in25. This framework uses a multi-objective artificial hummingbird algorithm (AHA) to minimize losses, voltage variation, and investment costs. An effective method for achieving optimum allocating the renewable units in the networks is presented in reference26. This method takes into account the uncertainties associated with energy production and loading through the use of Monte Carlo simulation and the AHA. A probabilistic approach for minimizing total losses while analyzing the steady-state operational circumstances of an active electrical distribution system with WT generation is presented in27. In28, optimal operation of DGs in distribution network is performed to minimize power loss incorporating the uncertainty of wind and PV resources based on fast forward scenario reduction using PSO.

Research gaps as identified in the literature are as follows:

-

1.

The majority of studies, including5,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, have neglected to account for modeling uncertainties, such as those associated with renewable energy sources and distribution network demand. Consider the unpredictability of consumption and power generation from renewable sources. Consequently, the magnitude of demand or renewable generation in an actual situation may deviate from the projected value in the scenario linked to the deterministic model. Low reliability characterizes the outcomes produced by the deterministic model in this instance. Hence, given the circumstances, stochastic modeling of uncertainties is required, an aspect that has been neglected in previous studies5,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

-

2.

The literature review indicates that the Monte Carlo simulation method (MCS) is a widely used technique for simulating uncertainty in the optimal distribution of energy resources within a network26,27,28. The MCS necessitates immense quantities of data containing probability distributions. In making forecasts for values derived from probability distribution functions, a random selection process is used. As a result, the principal drawbacks of this approach are its time-intensive nature and the significant reliance of its results on the specified scenario.

-

3.

The literature review reveals that meta-heuristic algorithms are of paramount importance when it comes to the optimization of energy systems. Nonetheless, it is possible that a meta-heuristic method is not optimal for resolving every optimization issue. The No Free Lunch (NFL) theory29 posits that when it comes to the case of complicated issues, robust algorithms are needed that avoid premature convergence. The optimization methods are undergoing enhancements to enhance efficacy and prevent the occurrence of local optimal traps, with the ultimate goal of achieving more precise solutions.

Contributions

Here’s an extended version of the contributions for the paper titled “A Multi-objective Improved Horse Herd Optimizer Based on Convex Lens Imaging for Stochastic Optimization of Wind Energy Resources in Distribution”:

-

1.

Optimal and Multi-objective Placement of Wind Turbines (WTs): The paper proposes a comprehensive approach to optimally place WTs within 33-, real 45-, and 69-bus radial distribution networks. The objective is to minimize power losses, reduce generation costs associated with WTs, and enhance the network’s reliability. This is achieved by reducing the energy not provided (ENP) to customers, ensuring that the network becomes more resilient to fluctuations in both supply and demand.

-

2.

Stochastic Modeling Using the Unscented Transformation (UT): The research introduces the utilization of the unscented transformation (UT)30 to effectively model the inherent uncertainties associated with renewable energy production and fluctuating network demand. By incorporating these stochastic variables, the study presents a more realistic scenario for the allocation of WTs, allowing for robust and uncertainty-resilient decision-making.

-

3.

Novel Multi-objective Metaheuristic Algorithm – MOIHHO: The study proposes the multi-objective improved horse herd optimizer (MOIHHO), which builds upon the conventional horse herd optimizer (HHO)31. A unique feature of the MOIHHO is its adoption of a convex lens imaging strategy to enhance the convergence behavior of the algorithm. This helps overcome premature convergence, a common issue in traditional optimization algorithms. Additionally, a fuzzy decision-making approach is employed to finalize the solution, ensuring a balance between conflicting objectives.

-

4.

Comprehensive Validation and Comparative Analysis: To demonstrate the robustness and superiority of the proposed MOIHHO, its performance is rigorously tested against several state-of-the-art multi-objective optimization algorithms. These include the multi-objective conventional horse herd optimizer (MOHHO), multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO), multi-objective grey wolf optimizer (MOGWO)32, and multi-objective gazelle optimization algorithm (MOGOA)33. The comparative analysis highlights the efficacy of MOIHHO in solving the complex placement problem with a higher degree of accuracy and reliability.

Paper organization

In Sect. 2, the formulation of the issue is elaborated. Section 3 describes the proposed multi-objective optimizer named MOIHHO and its implementation to solve the WTs allocation issue. In Sect. 4, the unscented transformation method to model the uncertainties is outlined. The findings and analyses of the simulations are given in Sect. 5, while the conclusions of the research are summarized in Sect. 6.

Problem formulation

Objective function

Fuzzy multi-objective allocating the WTs in radial distribution networks is accomplished in this study by integrating fuzzy decision-making with a new multi-objective meta-heuristic algorithm named MOIHHO to minimize power loss, thereby enhancing network reliability and minimizing WT cost minimization. Following this, the objective function and restrictions of the problem are formulated.

Cost of power loss

The reduction of power losses stands as a paramount operational function of distribution networks. The determination of the distribution network overall losses is established through the computation of line currents and overall losses. As follows, the total cost of energy loss during the one-year study period is calculated9,11,22:

Where, \(\:A{P}_{Loss}\) is total power loss, Rl and Xl are the line l ohmic resistance and also reactance, Nl denotes the network lines number, \(\:{V}_{i}\:\) is the bus i voltage, \(\:{V}_{j}\:\) clears the voltage of bus j, and \({\mathchar'26\mkern-10mu\lambda _{loss}}\) is cost of loss per kW (0.06 $/kW)9,11,22.

Reliability improvement

Another advantage of optimizing the application of WT in a distribution network is its reliability. Certain consumers might experience extended periods of service disruptions while the fault is being resolved in the network lines9,11,34. Additionally, certain customers residing in faulted segments of the network who are supplied in an islanding condition may be autonomously segregated from the faulted segment. Under such circumstances, WT possesses the capability to reinstate power to the downward segment of the faulty branch, thereby improving the network’s dependability. The optimal allocation of WTs has the potential to decrease the cost of the network caused by the customer’s disruption. The reliability is stated in this analysis as the energy not-provided (ENP) of the distribution network. The definition of the reliability-based ENP is computed by9,11,34

Where, \({\xi _i}\) is the line length, \(\ell\) denotes the quantity of loads that are interrupted as a result of the line i outage, \({\Omega _i}\) represents the annual outage value per km, \(\phi\) indicates the load disruption caused by the line i outage, and \({\tau _i}\) is the time required to resolve the fault. Also, InfR and IntR are the inflation and interest rates.

WTs cost

The cost of the WT application comprises expenditures for investment, operation, and maintenance. The subsequent costs are delineated34.

Where, \(\:{\varpi\:}_{WT}^{INV}\), \(\:{\varpi\:}_{WT}^{OPR}\) and \(\:{\varpi\:}_{WT}^{MAN}\) are investment, operation and maintenance costs, respectively.

\(\:{\varpi\:}_{WT}^{INV}(\$/MWh)\) is an initial payment associated with the acquisition and installation of each WT as defined by34

Where, the cost of procuring and installing units ith WT is denoted by\(\:\:{\varpi\:}_{i}^{investment}\).

An essential factor with respect to WT units is the operational cost, denoted as\(\:{\:\varpi\:}_{WT}^{OPR}(\$/MWh-year)\)34.

In this case, \(\varpi _{i}^{{operation}}\) represents the operational cost of the ith WT and can be computed as34

The annual cost denoted as \(\:{\varpi\:}_{WT}^{MAN}\:(\$/MWh-year)\) comprises the interest and inflation rates. It can be mathematically represented as follows34:

The maintenance cost of the ith WT, denoted as\(\:{\:\varpi\:}_{i}^{\text{maintenance}}\), can be computed as follows34:

Constraints

When addressing the allocation problem of WTs, the objective function is optimized while taking into account the inequality and equality constraints as described below9,11,22,34.

Power balance constraint

The injected power of active and reactive by the post and WTs should be equivalent to power lost in the network lines and active and reactive power consumed using the load during the operation of the distribution network. Therefore, the total transmitted and demanded power in the network should be equal in algebraic form9,11,22,34:

Where, Nwt is number of wind turbines, l refers to the line numbers, N is number of buses, Nwt denotes number of distributed generation as wind turbines, \(\:{P}_{Post}\:\) and \(\:{Q}_{Post}\:\) is power of active and reactive related to the bus of slack, \(\:{P}_{WT}\:\) and \(\:{Q}_{WT}\:\) are WT active and reactive power, \(\:{P}_{Lineloss}\) and \(\:{Q}_{Lineloss}\:\) denote active and reactive loss and\(\:\:Pd\), and \(\:Qd\:\) indicate the active and reactive network demand, respectively.

Bus voltage constraint

Throughout the optimization procedure, the voltage deviations of the network circuits must remain within the permissible range. The buses voltage should remain among the predetermined allowable range, which consists of the minimum and maximum limitations specified below9,11,22,34:

Where, \(\:{\vartheta\:}_{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}\:\) and \(\:{\vartheta\:}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\:\) are tuned 0.95 p.u. and 1.05 p.u., respectively.

WT capacity constraint

The greatest power of active and reactive that can be accommodated in WT is 0.75 times the sum of the active and reactive power depleted in the network branches and the active and reactive load9,11,22,34.

Where, APWT, and RQWT are WT power of active and reactive, respectively.

Furthermore, minimum and maximal generation constraints apply to WTs9,11,22,34:

Where, \(\:A{P}_{WT}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}\:\) and \(\:A{P}_{WT}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\:\) are lower and upper active power of wind turbine, and\(\:\:R{Q}_{WT}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}\), and\(\:\:R{Q}_{WT}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\:\) are lower and upper reactive power of wind turbine, respectively.

Line capacity constraint

The capacity of the network branches to transport electrical current is finite. Overcapacity may result in harm to the network lines. The magnitude of the complex power emitted by each line (\(\:{\varUpsilon\:}_{\mathcal{l}i}\)) is defined by9,11,22,34

Where, \(\:{\varUpsilon\:}_{\mathcal{l}i,rated}\:\) is maximum allowable capacity of the network line.

Recommended optimizer

In this study, a new multi-objective improved horse herd optimizer (MOIHHO) is proposed for allocating the WTs in distribution networks. In following the formulation of this method is described.

Mathematical programming and meta-heuristic approaches are employed to address optimization problems. While mathematical programming methods ensure reaching the optimal solution, meta-heuristic approaches do not offer such a guarantee. However, meta-heuristic methods can handle large-scale and complex optimization problems, whereas mathematical programming methods may struggle as the problem size grows. Mathematical programming relies on derivatives, meaning the Lagrange function is calculated, followed by deriving the Kuhn-Tucker conditions to solve the problem. Differentiability is achieved when the problem is convex, but the stochastic allocation of wind turbines (WT) in a radial distribution network based on utility theory (UT) is non-convex. Thus, the issue of differentiability arises, though solutions exist, they tend to be complex. In essence, solving such problems involves intricate mathematical algorithms. On the other hand, meta-heuristic algorithms allow for easier problem-solving without introducing excessive complexity or computational costs. Hence, this study adopts meta-heuristic methods to avoid complications and manage computational expenses.

Traditional HHO

The HHO is modeled based on the horses’ daily lives. The HHO is modeled by taking into account various behaviors of the horse life at various ages including grazing (G), hierarchy (H), sociability (S), imitation (I), defense structure (D), and roaming (R)31.

The representation of the horses’ motion during each iteration is given through31.

Where, \(\:{X}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) is the position of horse m at iteration Iter, \(\:{X}_{m}^{(Iter-1),AGE}\:\) is the location of horse m at iteration Iter-1, AGE is the horse age range, Iter is the present iteration, and \(\:{\overrightarrow{V}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) is the horse speed vector. \(\:\delta\:\) is horses age among 0 and 5 yrs, \(\:\gamma\:\) for the horses within 5 to 10 yrs, \(\:\beta\:\) denotes the horses among 10 to 15 yrs and \(\:\alpha\:\) refers to the horses greater than 15 yrs. In the responses matrix incorporated in the algorithm, the primary 10% of the matrix denote the horses of\(\:\:\alpha\:\), the next 20% is the horses of\(\:\:\beta\:\), also the \(\:\gamma\:\) and \(\:\delta\:\) including 30% and 40% of the remained horses31.

The motion vector of horses across various age categories during each iteration is specified outlined below31.

Lifelong habit patterns exhibited by horses are detailed as follows:

Grazing (G)

Using a factor of g, the grazing region for each horse is modeled. The horses are permitted to graze indefinitely in their lifetimes. The equine grazing habit model is provided as follows31.

Where, the horse i’s moving parameter is denoted by\(\:{\overrightarrow{G}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\), which the trend of decrease with each repetition corresponds to \(\:{w}_{g}\) for a linear fashion. \( \rlap{--} l \) and \( \rlap{--} u \) are minimum and maximum values of the area of grazing, and \( p \) is a random number ((0, 1)), and g is selected 1.5 for the horses, regardless of age31.

Hierarchy (H)

The horses are primarily supervised by a commander who oversees humans. Additionally, both stallions and mares are capable of commanding a herd of wild horses. The desire of a horses herd to travel with the more strong and knowledgeable horse (in addition to horses and ) is denoted by the value of h in the algorithm. The presentation of this sequential habit is presented by31.

Where, \(\:{\overrightarrow{H}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) is the horse best location impact in view of velocity and \(\:{X}_{*}^{(Iter-1)}\) is the best horse location.

Sociability (S)

The horses maintain the social environment to ensure their survival and well-being. Their behavior in society is denoted by the parameter s and is manifested using a tendency to move the position of the other horses. The majority of horses and are more concerned with herd life, as illustrated follows31.

Where, \(\:{\overrightarrow{S}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) is the vector of horse i social motion related to the horse i, \(\:{s}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) indicates the horse i motion direction with respect to the livestock within the iteration. With the consideration of the coefficient ωs, the value of \(\:{s}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\) decreases with each iteration. AGE denotes the age span of each horse, while N is the overal horses number.

Imitation

horses’ behavior of imitation is illustrated in Fig. 1. Their actions are replicated by the horses, including locating an appropriate pasture. The emulation of horses is investigated based on a factor of i. The habit of imitation is greater in juvenile horses31.

Where, \(\:{\overrightarrow{I}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) is the movement of the horse i vector with respect to a horse at positions\(\:\:\widehat{X}\), \(\:pN\) is the horses percentage that obtained the greatest locations (10% of the total horses).

The imitation behavior of the horses31.

Defense mechanism (D)

The horses exhibit defensive performances by fleeing from their adversaries and yielding, both of which are deemed suboptimal reactions. The defensive conduct of horses is stated via the factor d. In the subsequent model, the horses’ defensive behavior is represented by a coefficient that is negative in order to deter them from unpleasant solutions31.

In the provided information, \(\:{w}_{d}\:\) denotes the decreasing rate for each iteration, \(\:qN\) signifies the number of horses with the worst possible locations, and \(\:{\overrightarrow{D}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) indicates the horse i escaping vector.

Roaming

Horses forage and move from grassland to pasture for food in the wild. The coefficient r characterizes the irregular movements that constitute a wandering behavior. This habit is more prevalent in juvenile horses and gradually disappears as they mature. The definition of roaming habit is defined by.

Where, \(\:{\overrightarrow{R}}_{m}^{Iter,AGE}\:\) denotes the vector i for horse velocity used to arbitrarily escape local optimal, and \(\:{w}_{r}\) signifies the reducing in constant for each iteration.

The HHO pseudo-code is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1: Horse herd optimization |

a) Principal framework: Implementation of the algorithm’s parameter and variable set; b) Initial measuring: Randomized distribution of horses throughout a search space; c) Fitness Assessment: Determine the fitness per horse in accordance with the geographical location. d) Age calculation: the age of every horse (α, β, γ, δ) is determined; e) Pace application: each horse velocity is evaluated about its age; and f) Assessment of new positions: the search space is modified to reflect the latest locations of each horse. g) Convergence requirement: Return to step c as long as the algorithm terminates and the convergence requirement is satisfied. |

Improved HHO (IHHO)

The study literature suggests that traditional optimizers struggle to find the best solution in complicated issues, often getting stuck in local optimums. To address this, special integration techniques are recommended as a partial solution. This research applies a mirror imaging technique based on convex lens imaging to combat premature convergence in the traditional HHO. The HHO tends to get trapped in local optimal and experience premature convergence due to problem complexity and combined structures. Therefore, employing specific methods to enhance HHO’s performance in complex conditions and prevent premature convergence and local optimum trapping is crucial.

Oppositional-based learning, a successful optimization technique, expands the search domain by computing opposition solutions at current positions, thereby locating additional suitable answers to optimization problems. Lens imaging learning35, a variation of opposition-based learning, is derived from convex lens imaging principles in optics. In this process, an object positioned on the opposite side of a convex lens is refracted to the other side, yielding more optimal solutions. This study integrates the mirror imaging concept36 with convex lens imaging, drawing inspiration from the process. By using the mirror imaging based on convex lens imaging, the technique generates symmetric opposition answers, thereby broadening the range of possible solutions. This approach enhances the optimization steps via enabling it to move away from local optima.

Figure 2 illustrates the mirror imaging technique that utilizes convex lens imaging. The search area for the answer along the x-axis in two-dimensional space is [L, U], while the mirror area is represented on the y-axis by the positive half-axis, which corresponds to the convex mirror region. The region reflecting the surface is the negative half-axis. Consider the individual (\(\:\theta\:\)) of a horse to be in the original mirror region, which has an x-axis projection (X) and a height (H). A practical representation (\(\theta\)) can be acquired through convex lens imaging. This yields an opposition individual (\(\:{\theta\:}^{*}\)) of \(\theta\), denoted using a height \({\Psi ^*}\) and a projection (\({X^*}\)) along the x-axis. By mirroring \(\:{\theta\:}^{*}\) using the principle of surface mirror image, a new opposition individual (\(\:{\theta\:}^{**}\)) is generated, which consists of the height \({\Psi ^*}\) and the projection (\(\:{X}^{**}\)), where \(\left| {{X^{**}}} \right|=\left| {{X^*}} \right|\). Ultimately, \(\theta\) yields \(\:{\theta\:}^{*}\) and \(\:\:{\theta\:}^{**}\).

The mirror imaging according to convex lens imaging35.

In accordance with the convex lens imaging principle, \(\:{\theta\:}^{*}\) is obtained using its starting point of coordinates (O) as its base point\(\:{\:\theta\:}^{*}\); the coordinates of this point are calculable using Eq. (35)35.

U represents the highest limit, while L denotes the lowest limit, let\(\:\:\kappa\:=\frac{\varPsi\:}{{\varPsi\:}^{*}}\)35.

The number of distinct convex lens-imaging projection sites along the x-axis varies depending on the thickness of the lens. To increase the range of convex lens imaging solutions, the thickness of the lens can be adjusted continuously (scaling factor), thus obtaining additional solutions for mirror imaging. Scaling enhances the optimizer’s ability for local exploitation. In this study, a nonlinear dynamic scaling factor approach is employed to improve the Horse Herd Optimizer (HHO). A significant value is initially obtained during the algorithm’s iteration, allowing the HHO to explore extensively across regions of varying dimensions, thereby enhancing population diversity. To enhance local search capability, smaller values are acquired within each iteration of the algorithm, focusing on a modified search around the optimal individual. Equation (37) specifies the nonlinear dynamic scaling factor35:

Where, \({\kappa _{\hbox{max} }}\) and \({\kappa _{\hbox{min} }}\) are the upper and lower scaling factors, and T denotes the iterations maximum number of iterations and these factors are considered\(\:{\kappa\:}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}=10\), and \(\:{\kappa\:}_{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}=9\).

By expanding Eq. (38) into z-dimensional space, the presentation is obtained35:

Flowchart of the IHHO is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Multi-objective IHHO (MOIHHO)

In a multi-objective (MO) optimization framework, problems are characterized by the presence of multiple solutions that form the Pareto front. Each solution on this front represents a trade-off between competing objectives. Notably, certain Pareto-optimal solutions allow for reduced compromise between objectives, striking a balance that satisfies multiple criteria simultaneously. To identify the most appropriate solution from this set, a fuzzy decision-making method is often applied. The primary goal of this approach is to minimize the given objective function, which is formulated to reflect the competing demands of the system being optimized. The formulation of this kind of optimization is aimed at minimizing the subsequent function9:

In this context, the symbols o, m, and p represent the objectives and constraints, respectively, while [Li, Ui] denotes the upper and lower bounds for the ith variable. Within the realm of multi-objective (MO) optimization, traditional operators struggle to directly compare various solutions. However, Pareto dominance principles offer a method to assess two solutions by considering their performance across multiple objectives. Addressing a multi-objective problem typically involves exploring a set of potential solutions, where each solution independently satisfies its respective objective without relying on other solutions. The ultimate goal is to find an accurate approximation of the Pareto-optimal front, ensuring comprehensive coverage of all objectives and providing solutions that maintain monotonicity across the objective space.

In addressing the MO problems using the MOIHHO, the optimization process begins by incorporating an archive mechanism. This archive serves to store and retrieve the most accurate estimates of the Pareto-optimal solutions. While the positions of the search agents remain static in MOIHHO, the selection of candidate member positions is guided by the archive. To overcome challenges related to sparse populations along the Pareto front, an optimal position is identified to extend the front. This is achieved by dividing the search space into sub-hyper-spheres, representing the hyper-sphere that encompasses all solutions. Additionally, the best and worst objective values of the Pareto solutions are determined. A roulette wheel selection mechanism is then used to elect solutions for each sub-region, with predefined probabilities guiding the selection process. This strategy ensures diversity across the Pareto front while maintaining a balance between exploration and exploitation within the search space9.

Where, Ni represents the Pareto answer number at the i-th area, while c denotes a fixed value.

The jth objective function, which takes into account the determination of an answer from a Pareto set fj via the membership function j, is as follows9:

Where, \(\:{f}_{j}^{min}\) and \(\:{f}_{j}^{max\:}\) refer to the lower and upper value of the jth objective function.

The membership function µj for each objective can be presented, where the degree of satisfaction for each objective function is represented on a scale from zero to one. This scale acts as a fuzzy membership function, ranging from 0 to 1. The value of µj reflects the satisfaction level of the objective, where µj = 1 indicates full satisfaction and µj = 0 signifies complete dissatisfaction. By employing this fuzzy membership approach, decision-makers are provided with a clear representation of satisfaction levels for each objective. Moreover, this method facilitates the normalization of objectives with different units, allowing them to be uniformly expressed within the range of 0 to 1.

The membership function \(\:{\mu\:}_{j}\) is defined as follows9:

Where, n represents the objective functions number and m denotes the number of solution. A compromise is optimally resolved by a solution in which the value of µi is greater.

To address multi-objective optimization challenges, the fuzzy decision-making process begins by utilizing fuzzy logic to manage the uncertainty and vagueness often present in evaluating solutions. This approach offers a flexible, intuitive method by assigning membership degrees to each solution based on its performance across multiple objectives. These membership degrees reflect how well a solution satisfies each objective, allowing for a more nuanced comparison of solutions. The evaluation of the final solution is based on two types of criteria: objective metrics and subjective considerations. Objective metrics include measures like how effectively the solution balances trade-offs among various objectives and its closeness to the true Pareto front. On the other hand, subjective considerations may involve expert judgment, stakeholder preferences, or real-world priorities. These subjective factors are incorporated into the decision-making process using linguistic variables and fuzzy rules. By combining both objective and subjective factors, the fuzzy decision-making process enables a thorough assessment of solutions. It helps navigate the inherent trade-offs in multi-objective optimization, guiding decision-makers toward a final solution that offers a balanced compromise between competing objectives. This ensures that the selected solution aligns not only with quantitative performance measures but also with qualitative preferences and real-world considerations.

The MOIHHO implementation

The flowchart of the IHHO to solve the problem is depicted in Fig. 4. Also, the following are the procedures required for executing MOIHHO to resolve the multi-objective allocation of WTs in the network while minimizing the losses and WT generation costs, and increasing reliability through fuzzy decision-making:

Step 1) Initiate the network data including bus and line data, WT techno–economic data as well as population size, the greatest number of algorithm iterations, and the highest number of archives of the algorithm.

Step 2) Initiate the population of the MOIHHO and produce random variables.

The search boundaries of the model parameters are presented as follows: The two WTs is allocated in each distribution network. The lower and upper bound of each WT power size is considered 0, and 2 MW, respectively. For 33-, 45-, and 69-bus network the lower bound for installation location in the network is selected 2 (Bus 2), and the upper bound is considered 33, 45, and 69, respectively. Also, the lower and upper bound of each WT power factor are established 0, and 1, respectively. Also, the mentioned constrains presented in Eqs. (10)-(17) should be satisfied during the optimization process to create the feasible solution.

Step 3) Normalize the objective function by employing the Pareto front.

Step 4) Once each objective function has been normalized, it is calculated utilizing Eq. (45).

Step 5) Calculate the greatest and lowest values by assessing the objective function value-based sorting operation on the horses.

Step 6) Update the horses position.

Step 7) Calculate the objective functions and normalize them. If the achieved solution corresponds to the better objective function value, replace the correspond best horse with the old one.

Step 8) Are the convergence requirements met? If so, go to Step 9; if not, proceed to Step 6.

Step 9) Save the optimal solution and stop the MOIHHO.

UT based–stochastic approach

The Unscented Transformation (UT)30 is applied as an uncertainty model to tackle the stochastic multi-objective placement of wind turbines (WTs) in the distribution network. Its goal is to improve network reliability while simultaneously minimizing power losses and WT generation costs, all within the context of uncertainties in network demand and renewable generation. Unlike the computationally intensive Monte Carlo simulation, the UT offers a more efficient alternative by reducing computational complexity and execution time, without requiring any prior assumptions. The UT excels in modeling risks and uncertainties, which are inherent to decision-making in power systems. The primary idea behind the UT is that it is easier to approximate a probability density function (PDF) than to calculate the result of a nonlinear function transformation. The UT capitalizes on this by using a set of strategically selected elements, known as sigma points, along with corresponding weights, to represent the PDF. This approach allows for the efficient derivation of important metrics like the mean, variance, and other characteristics of the system’s response to different scenarios. By operating on these sigma points, the UT captures the effects of uncertainty with fewer samples compared to traditional methods, such as Monte Carlo simulations, which require a much larger sample size.

One of the key advantages of the UT lies in its simplicity and the fact that it does not demand high-dimensional sample sizes to deliver accurate results. In this study, the parameter “n” is used to indicate the level of uncertainty in the input vector (U), and the method generates 2n + 1 scenarios (with n set to 2 in this case). Despite the limited number of scenarios and without employing any scenario reduction techniques, the computational burden is significantly lessened, leading to faster calculations. The UT efficiently computes the covariance and mean of the final outcomes, which ensures that the methodology remains computationally feasible even when handling complex systems with stochastic uncertainties. Additionally, the UT’s strength in accurately simulating the propagation of uncertainty in nonlinear systems makes it highly suitable for renewable energy applications, where variability and unpredictability are key challenges. This methodology not only enhances the decision-making process in WT allocation but also maintains computational efficiency, making it an ideal choice for real-time power network operations. Through this study, the UT demonstrates its effectiveness in optimizing network reliability and reducing operational costs under uncertainty.

The problem’s overarching structure is articulated as y = f(x), embodying a nonlinear nature and influenced by uncertain parameters, where x and y denote input and output vectors, respectively. Utilizing the UT, as delineated in Ref.30, facilitates the determination of output mean and covariance (denoted by µx and σx) for more comprehensive analysis. The below approach presents finding the mentioned two parameters:

Step A

Select 2n + 1 samples as the beginning date for the uncertain parameters30.

Where, \(\:x\in\:{R}^{n}\) is vector of uncertain input, \(\:{\mu\:}_{x}\:\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{X}\:\) are mean and covariance of x, and \(\:{W}^{0}\:\) refers to the mean value weighted value of x, is equal to r.

Step B

Determine the weights for each sample30.

Step C

The sample 2n + 1 value represents the nonlinear function utilized to generate the consequence samples as specified in Eq. (53).

Where, \(\:y\in\:{R}^{r}\) indicates vector of uncertainty with r elements.

Step D

Compute and for variable30.

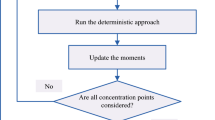

The flowchart of UT based–stochastic approach process is depicted in Fig. 5.

The flowchart of UT based–Stochastic Approach30.

Simulation results and discussion

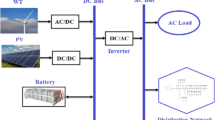

Network data

This study proposes a MOIHHO with the fuzzy method for deterministic and stochastic multi-objective allocation of WTs in the networks with the goals of minimizing power losses and WT generation costs while improving reliability. The suggested method is executed on 33-, 45-, and 69-bus distribution networks. Figures 6, 7 and 8 illustrate these networks, respectively. The network data, which consists of bus and line information, is obtained from Refs37,38,39. The load consumption on the 33-bus network is 2300 kVAr and 3720 kW. Additionally, the 69-bus network has 3800 kW and 2690 kVAr load demand. The 45-bus network is shown in Fig. 8. The 45-bus network has a 66 kV voltage, 100 MW apparent power, and a 2826.42 MVA load capacity38,39.

The annual line outage rate is calculated to be 0.046 per km, as stated in Ref34. The reliability of additional devices within these systems is assumed to be 100%. The repair time for a line in an outage condition is considered 8 h34. Annually, the load increases by 10%. Fuzzy multi-objective allocating two WTs in 33-bus and 69-bus distribution networks is the subject of this study. A maximal capacity of 2 MW is designated for each WT. The estimated investment, operation, and maintenance costs for WT are selected $150,000 per unit, $29 per MWh, and $7 per MWh, respectively34,40. Furthermore, the chosen interest and inflation rates are 12% and 9%, respectively34. Additionally, the cost per kW of power loss is selected $0.06 according to Ref11. The MOIHHO’s problem-solving capability is evaluated in comparison with the MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA. The maximum number of iterations, population size, and archives integrated with the algorithms are considered as 50, 150, and 300, respectively. The values specified in the reference papers of each algorithm are taken into account for the general and adjustable parameters. The proposed methodology is executed on a personal computer equipped with a Corei7 (3.1 GHz, 1 TB) in MATLAB software.

Simulation scenarios

The following simulation scenarios are taken into account in this study:

Scenario#1

Deterministic fuzzy multi-objective allocating two WTs using the MOIHHO in.

-

33-bus distribution network.

-

69-bus distribution network.

-

Real 45-bus distribution network.

Scenario#2

Stochastic fuzzy multi-objective allocation of two WTs using the unscented transformation (UT) and MOIHHO considering uncertainty in.

-

33-bus distribution network.

-

69-bus distribution network.

-

Real 45-bus distribution network.

Scenario#3

Stochastic fuzzy multi-objective allocation of two WTs using the UT considering interest rate variation (IRV) effect in.

-

33-bus distribution network.

-

69-bus distribution network.

-

Real 45-bus distribution network.

Results of scenario#1

In this section, the results of deterministic multi-objective allocation of WTs in the 33-, 59- and 69-bus networks to minimize the power losses cost and WT generation cost as well as the reliability improvement are presented without considering the uncertainty using the MOIHOH.

The 33-bus network, scenario#1

The results of WTs allocation in the 33-bus distribution network using the MOIHOH are presented for Scenario #1. Figure 9 illustrates the Pareto front obtained through MOIHOH, showcasing a balanced trade-off among the three distinct objectives. The fuzzy multi-objective optimization approach facilitates an effective compromise by distributing the set of Pareto-optimal solutions across the different objectives. Ultimately, the optimal solution is determined through fuzzy decision-making, as depicted in Fig. 9. Based on this figure and the final fuzzy decision, key performance metrics such as the loss cost, ENP for subscribers, and the WT power cost have been calculated. Specifically, the results show a loss cost of $16,593.47, an ENP of 1.39 MWh per year, and a WT power cost amounting to $881,764.91.

This approach emphasizes the strength of fuzzy decision-making in handling multi-objective problems by providing a structured framework for balancing competing goals. By applying MOIHOH, the solution space is explored comprehensively, ensuring that each objective—whether it be minimizing costs, optimizing energy supply reliability, or reducing operational expenses—is considered in a fair and logical manner.

The numerical results of the WT allocation, utilizing the MOIHOH approach integrated with fuzzy decision-making, for the 33-bus distribution network are displayed in Table 1 for Scenario #1. The results reveal significant improvements across all objectives when compared to the base network. Specifically, the optimal integration of WTs has led to a considerable reduction in both power loss costs and the ENP for subscribers.

According to the data in Table 1, it is evident that the proposed MOIHOH approach outperforms other algorithms, including MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA, in optimizing the objectives. The MOIHOH successfully installs two wind turbines of 709 kW and 1185 kW capacities at buses 13 and 30, respectively, with power factors of 0.90 and 0.86. This optimal placement reduces power loss costs from $106,528.26 to $16,593.47, while the ENP is minimized from 6.69 MWh per year to 1.39 MWh per year. Additionally, the MOIHOH yields a WT generation cost of $881,764.91 and enhances the minimum voltage from 0.9130 p.u. in the base network to 0.9796 p.u. This demonstrates that the MOIHOH not only identifies the ideal sizes and power factors for WT installation but also achieves a superior balance between competing objectives, ultimately leading to better overall performance.

By integrating fuzzy decision-making into the MOIHOH, the approach effectively handles the complexity of multiple objectives, providing a well-rounded solution that enhances the network’s performance while optimizing energy generation and distribution costs. The superior results confirm MOIHOH’s effectiveness in solving multi-objective optimization problems in distribution networks.

The performance of the MOIHHO algorithm is evaluated in comparison with four other algorithms: MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA, over 25 independent runs. This assessment is based on the use of the C index (CI) as a key performance metric. The C index is a tool designed to compare the effectiveness of two algorithms in solving multi-objective optimization problems. It quantifies the percentage of solutions produced by the proposed algorithm that outperform those generated by the competing algorithms. Essentially, the CI highlights the superiority of one algorithm’s Pareto solutions over another.

In this study, the CI is used as a benchmark to assess the ability of these algorithms to optimally allocate wind energy resources within a 33-bus distribution network under Scenario #1. By analyzing and comparing the Pareto solutions generated by each algorithm, the CI provides a clear indication of how well each method performs in handling the deterministic wind turbine placement problem. Through this comparison, the MOIHHO’s performance is scrutinized against the alternatives, focusing on how effectively it balances multiple objectives. A higher CI value for MOIHHO would indicate that it delivers a greater proportion of superior solutions, demonstrating its ability to provide more optimal and diverse trade-offs in the complex task of wind energy allocation within the distribution network. This evaluation not only validates the robustness of MOIHHO but also offers insights into the relative strengths and weaknesses of the other algorithms in addressing multi-objective optimization challenges in power distribution systems.

Let’s denote 1 and 2 as the Pareto solutions generated by two distinct methods. The metric (1, 2) quantifies the percentage of answers in set 2 that are dominated by answers in set 1. This comparison method provides valuable insights into the relative efficacy of each algorithm in addressing the allocation challenge by41

Where, 1 and 2 represent the Pareto solutions within sets 1 and 2, respectively. Calculating the average across n independent executions yields the CI, serving as a comparative measure. A higher CI indicates a more favorable Pareto solution. This approach allows for a nuanced understanding of the quality of solutions generated by each algorithm, guiding the selection of the most effective one to address the optimization task at hand.

As per Table 2, the CIs have been computed for various algorithms. The findings reveal that in rows 2, 4, 6, and 8, the MOIHHO surpasses MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA with domination rates of 91.23%, 70.40%, 76.43%, and 83.97%, respectively, on average. Moreover, the MOIMRFO demonstrates superior performance in attaining enhanced Pareto front solutions compared to MOMRFO, MOPSO, and MOGWO methodologies. This evidence underscores the effectiveness of MOIMRFO in achieving more favorable outcomes in the optimization process.

The 69-bus network, scenario#1

This section presents the results of using the MOIHHO algorithm to allocate wind turbines (WTs) in the 69-bus distribution network for Scenario #1. The Pareto solution set generated by MOIHHO is depicted in Fig. 10, showcasing a range of trade-offs between the objectives. Through the fuzzy multi-objective approach, the Pareto solutions are distributed in a manner that achieves a balanced compromise between the three distinct goals. Ultimately, the final fuzzy solution is determined using the fuzzy decision-making process, as shown in Fig. 10. Based on this fuzzy solution, key performance metrics such as the losses cost, the Expected Energy Not Supplied (ENP) for subscribers, and the cost of WT power have been calculated. Specifically, the losses cost has been reduced to $11,896.13, the ENP is minimized to 2.81 MWh per year, and the WT power cost has been estimated at $866,181.92.

For Scenario #1, Table 3 outlines the numerical results of multi-objective WT allocation using the MOIHOH algorithm integrated with fuzzy decision-making for the 69-bus distribution network. Each objective has seen marked improvements relative to the base network. The optimal placement of WTs significantly reduced both power loss costs and the subscribers ENP, in comparison to the base network. The results in Table 3 demonstrate that the proposed MOIHOH algorithm consistently outperforms other algorithms such as MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA across multiple objectives. Specifically, the MOIHOH installed two WTs with capacities of 1450 kW and 403 kW at buses 61 and 64, respectively, with power factors of 0.87 and 0.90. This placement achieved a notable reduction in ENP, lowering it from 11.85 MWh per year to 2.81 MWh per year, and reduced the power loss cost from $131,595.99 to $11,896.13. Furthermore, the MOIHOH calculated the cost of WT generation to be $866,181.92, while improving the minimum voltage level from 0.9041 p.u. in the base network to 0.9735 p.u.

In summary, MOIHOH effectively identified the optimal decision variables for WT placement, achieving a more favorable trade-off between various objectives. By balancing the minimization of power losses, reducing ENP, and enhancing voltage levels, the MOIHOH delivered superior performance across all goals compared to other algorithms. This highlights the algorithm’s capability in optimizing WT allocation for improved energy efficiency, reliability, and overall network performance. Moreover, the integration of fuzzy decision-making further strengthened its ability to handle complex multi-objective scenarios, making it a powerful tool for distribution network optimization.

As shown in Table 4, the CIs have been calculated for various algorithms applied to the 69-bus network. The results indicate that in rows 2, 4, 6, and 8, the MOIHHO outperforms MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA with average domination rates of 85.40%, 67.58%, 72.46%, and 85.66%, respectively. Additionally, the MOIMRFO exhibits superior performance in generating improved Pareto front solutions compared to MOMRFO, MOPSO, and MOGWO approaches. This data highlights the effectiveness of MOIMRFO in achieving more optimal results in the optimization process.

Results of scenario#2

In this section, the results of stochastic multi-objective allocation of WTs in the 33- and 69-bus networks considering uncertainty are given for minimizing the power losses cost and WT generation cost as well as the reliability improvement via the unscented transformation (UT) and the MOIHOH. The impact of incorporating the uncertainties of WTs production and also network load is evaluated on the problem solving and different objectives.

The 33-bus network, scenario#2

The results of using MOIHOH for the stochastic allocation of WTs in the 33-bus network for scenario 2, incorporating the uncertainties of wind power generation as well as network load demand, are given in this section. The final fuzzy solution and the collection of Pareto solutions obtained through MOIHOH based on fuzzy decision making are shown in Fig. 11. The fuzzy multi-objective method allocates the set of Pareto solutions among different objectives in a way that establishes a logical balance between all three objectives. As a result, the final fuzzy solution is found via the fuzzy decision-making approach shown in Fig. 11. The final fuzzy answer demonstrated that the values of the annual cost of power loss, ENP related to network subscribers, and power cost of WTs are obtained $17620.53, 1.47 MWh/yr and $892,434.19, respectively.

The results of the stochastic allocation of wind turbines (WTs) using the multi-objective MOIHOH algorithm in the 33-bus distribution network for Scenario #2 are summarized in Table 5. The findings show that the values of key objectives, including power loss costs and the Expected Energy Not Supplied (ENP), have significantly improved compared to the base network due to the optimal injection of both active and reactive power from the wind turbines. As illustrated in Table 5, the MOIHOH method achieves lower power loss costs and ENP compared to other algorithms such as MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA. By selecting superior decision variables, MOIHOH proves more effective in optimizing these objectives. Specifically, two WTs with capacities of 868 kW and 1042 kW are installed at buses 13 and 30, respectively, with power factors of 0.87 and 0.85. This configuration reduces the cost of power losses from $106,528.26 in the base network to $17,620.53, and decreases the ENP from 6.69 MWh per year to 1.47 MWh per year. Additionally, the cost of WT power generation using the MOIHOH method is calculated to be $892,434.19.

Furthermore, the MOIHOH method has improved the minimum voltage in the network, raising it from 0.9130 p.u. in the base network to 0.9786 p.u. This demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to optimize WT placement by delivering a balanced trade-off between different objectives. By providing more accurate values for the decision variables, MOIHOH achieves superior overall performance in the distribution network. In conclusion, the multi-objective optimization approach of MOIHOH successfully balances various competing goals, such as minimizing costs, enhancing energy reliability, and improving voltage profile.

The 69-bus network, scenario#2

In this section, the results of the multi-objective WT allocation in the 69-bus network using MOIHOH with a stochastic approach are presented. The Pareto front curve obtained from MOIHOH is shown in Fig. 12. According to this figure, the MOIHOH multi-objective method is capable to determine the final solution by distributing the Pareto front between different objectives and making a compromise between all three objectives, using a fuzzy decision-making approach. As demonstrated in Fig. 12, the final solution indicates that the cost of losses, ENP, and cost of WTs are $13,770.27, $2.91 MWh/yr, and $880,237.17, respectively.

The results of stochastic and multi-objective allocation of WTs in the 33-bus distribution network using MOIHOH and fuzzy decision-making for Scenario #2 are detailed in Table 6. Each objective, including power loss cost and ENP, has been reduced through the optimal injection of power from WTs when compared to the base network. As shown in Table 6, MOIHOH has successfully improved the overall network performance by achieving lower power loss costs and enhancing subscriber reliability (indicated by lower ENP).

To address the stochastic nature of the problem, MOIHOH has installed two WTs with capacities of 801 kW and 1092 kW at buses 57 and 61, respectively, with power factors of 0.86 and 0.85. This strategic placement of WTs results in a significant reduction in power loss cost, from $131,595.99 to $13,770.27, and a decrease in ENP from 11.85 MWh per year to 2.91 MWh per year. Additionally, the cost of wind power generation is calculated to be $880,237.17. Furthermore, MOIHOH has improved the minimum voltage level in the network, raising it from 0.9041 p.u. in the base network to 0.9711 p.u.

By optimally siting the WTs and ensuring their capacities align with network requirements, MOIHOH has achieved a more favorable balance between competing objectives. This improved balance allows for better overall performance in the distribution network. As a result, MOIHOH surpasses the performance of other algorithms such as MOHHO, MOPSO, MOGWO, and MOGOA, leading to superior outcomes in both energy efficiency and system reliability.

Results comparison

Comparison for the 33-bus network

The comparison between the deterministic and stochastic multi-objective allocation of wind turbines (WTs) for the 33-bus network, obtained in scenarios 1 and 2 using the MOIHHO, is summarized in Table 7. According to the results, the power loss cost increased from 16,593.47 kW in the deterministic case to 17,620.53 kW in the stochastic case. Similarly, the ENP rose from 1.39 MWh/year to 1.47 MWh/year, while the cost of WTs increased from $881,764.91 to $892,434.19 when accounting for uncertainty through the UT compared to the deterministic allocation of WTs. Additionally, the stochastic multi-objective allocation caused a slight reduction in the minimum voltage, dropping from 0.9796 p.u. to 0.9786 p.u. These changes indicate that the incorporation of stochastic factors in the allocation process leads to a 6.19% increase in power loss costs and a 5.75% increase in ENP compared to the deterministic method. The results emphasize the significant impact of uncertainty on network performance. Ignoring these uncertainty factors can lead to suboptimal decision-making, as network operators may fail to account for load variations and the inherent fluctuations in renewable energy output. Therefore, considering stochastic variations is essential for improving network reliability and ensuring optimal system performance under varying operating conditions.

A graphical comparison of various objectives in Scenarios 1 and 2 using the MOIHHO for the 33-bus network is depicted in Fig. 13. As shown in the figure, incorporating uncertainty has led to a weakening of each objective in the study. In other words, considering the inherent uncertainties within the stochastic model provides the network operator with a more precise understanding of the losses cost, reliability, and renewable energy generation costs. This accurate information enables the operator to make informed and effective decisions. On the other hand, the deterministic model is unable to deliver this level of insight or achieve the same results.

The inclusion of uncertainties allows the model to capture real-world conditions, which often fluctuate and are unpredictable, thereby offering a more realistic assessment of network performance. This level of detail ensures that decisions made regarding the allocation of resources, such as wind turbines, are more robust and better suited to handle the variability in both energy supply and demand. Consequently, the stochastic model equips operators with the tools necessary to optimize system reliability and cost-efficiency, whereas a deterministic approach would fall short in addressing the complexities introduced by uncertainty.

The variation in losses and the voltage profile of the 33-bus network for different deterministic and stochastic scenarios is illustrated in Figs. 14 and 15. As shown, taking into account the uncertainty in production and network load results in an increase in both losses and bus voltage deviations. In other words, the presence of uncertainty leads to higher losses and a deterioration in network voltage conditions.

Comparison for the 69-bus network

Table 8 provides a comparison between the outcomes of deterministic and stochastic multi-objective WT allocation for the 69-bus network using the MOIHHO combined with fuzzy decision-making. When uncertainty, modeled through UT, is taken into account, the power loss cost increases from 11,896.13 kW to 13,770.27 kW, while the Energy Not Supplied (ENP) rises from 2.81 MWh/year to 2.91 MWh/year. Additionally, the WT installation cost grows from $866,181.92 to $880,237.17. The inclusion of stochastic factors also results in a decrease in the network’s minimum voltage, from 0.9735 p.u. to 0.9711 p.u. The results indicate that the stochastic allocation of WTs for the 69-bus network leads to a 15.75% increase in power loss cost and a 3.55% increase in ENP compared to the deterministic allocation. These findings highlight the substantial influence of uncertainty on network performance, as ignoring stochastic variations can lead to underestimating costs and performance degradation. The integration of stochastic methods in WT allocation is crucial for enhancing the accuracy of network planning and ensuring the system can adapt to fluctuations in load demand and renewable energy generation. This approach allows network operators to make more informed decisions, optimizing both performance and reliability in real-world operating conditions.

Figure 16 provides a graphical comparison of different objectives in Scenarios 1 and 2 for the 69-bus network using the MOIHHO. This figure demonstrates that the incorporation of uncertainty has negatively impacted each of the objectives studied. Essentially, by accounting for the inherent uncertainties inherent in the stochastic model, the network operator acquires accurate insights into loss costs, reliability, and renewable energy generation costs, which facilitates more informed decision-making. In contrast, the deterministic model does not achieve this level of effectiveness.

The ability to consider these intrinsic uncertainties allows the network operator to better understand the variability in energy supply and demand, ultimately leading to more resilient and adaptable strategies. This level of insight is crucial for optimizing network performance and ensuring reliability under varying conditions. On the other hand, the deterministic model’s inability to incorporate such uncertainties results in a less comprehensive understanding of potential risks and challenges, making it less suitable for effectively managing the complexities of modern power systems. Overall, this analysis underscores the significance of utilizing stochastic approaches to enhance decision-making and improve network outcomes.

Figs. 17–18, illustrate the fluctuation of power loss and the voltage oscillations of the 33-bus network under various deterministic and stochastic conditions. Considering generation and network load uncertainty, it is evident that there has been a weakening in both losses and bus voltage deviations. It is clear in this case, the impact of uncertainty is linked to deteriorating network voltage conditions and increased losses.

The real Alexandria 45-bus network, scenarios#1, and 2

Table 9 provides a comparison between the outcomes of deterministic and stochastic multi-objective WT allocation for the real Alexandria 45-bus network using the MOIHHO combined with fuzzy decision-making. When uncertainty, modeled through UT, is taken into account, the power loss cost increases from 25,492.38 kW to 28,292.62 kW, while the ENP rises from 1.15 MWh/year to 1.09 MWh/year. Additionally, the WT installation cost grows from $860,350.22 to $889,350.22. The inclusion of stochastic factors also results in a decrease in the network’s minimum voltage, from 0.9385 p.u. to 0.9366 p.u. The results indicate that the stochastic allocation of WTs for the 45-bus network leads to a 10.98% increase in power loss cost and a 5.22% increase in ENP compared to the deterministic allocation. These findings highlight the substantial influence of uncertainty on network performance, as ignoring stochastic variations can lead to underestimating costs and performance degradation. The integration of stochastic methods in WT allocation is crucial for enhancing the accuracy of network planning and ensuring the system can adapt to fluctuations in load demand and renewable energy generation. This approach allows network operators to make more informed decisions, optimizing both performance and reliability in real-world operating conditions.

Results of interest rate effect, (Scenario#3)

In this scenario, the results of stochastic fuzzy multi-objective allocation of two WTs using the UT incorporating the interest rate variation (IRV) effect are presented on three 33-, 45-, and 69-bus distribution networks according to Tables 10, 11 and 12, respectively. Based on the results obtained from Tables 10, 11 and 12 for different distribution networks, it can be seen that with the increase in interest rate, the amount of power injected by wind turbines into the network has decreased, which is due to the reduction of wind turbine costs due to the increase in interest rate and On the contrary On the other hand, it has been observed that the increase in interest rate has increased network losses and weakened reliability (increasing ENP). Also, the minimum network voltage has been reduced. Therefore, the result has shown that the increase/decrease in interest rate weakens/strengthens the network performance based on the power injection of wind turbines in distribution networks.

Comparison with previous studies

The multi-objective allocating the WTs in the 33- and 69-bus network is studied for minimizing the losses cost and WT generation cost as well as the reliability improvement without considering the uncertainty using the MOIHOH. A comparison is made in Table 13, between the deterministic multi-objective outcomes of the MOIHOH and the results of42, which used a backtracking search optimizer (BSO) for allocation of the DGs in the 33-bus network using the weight coefficients approach and the aim of reducing voltage deviation and losses. The findings present that the MOIHOH achieves lower losses than the BSO (($16593.47/(0.06*8760 hrs) = 31.57 kW). Furthermore, a comparison in Table 14 is done among the outcomes of the MOIHOH for 69-bus networks and the outcomes of the allocation of WTs in the distribution network via CSA, SGA, and PSO as described in43. This comparison validates the superior performance of the MOIHOH, which achieved the lowest losses (($11896.13/(0.06*8760 hrs) = 22.63 kW).

Conclusion

In this paper, stochastic multi-objective allocating the WTs in radial distribution networks was performed via MOIHHO and UT considering the WTs generation and network demand uncertainties for minimizing the power loss, enhancing the reliability as well as WTs cost minimization. The optimal site, size, and power factor of WTs were found in the networks using the MOIHHO. The simulation outcomes were presented with and without considering uncertainty in two scenarios of deterministic and stochastic WT allocation. The outcomes of the simulations were presented as follows:

-

In deterministic WTs allocation, the losses cost declined by 84.42%, and 90.96% for 33- and 69-bus networks, and also the reliability is enhanced by 79.22%, and 76.28% for these networks, respectively.

-

In the stochastic allocation using the UT, the power loss cost, and ENP were increased by 15.75%, and 3.55% for the 33-bus network, and also these values are raised by 6.19%, and 5.75% for 69-bus network, respectively compared to the deterministic allocation.

-

The results showed that improving the performance of conventional MOHHO based on mirror imaging based on convex lens imaging with more accurate determination of decision variables led to achieving better values of each of the objectives.

-

The proposed MOIHHO demonstrated superior performance in achieving better objective values in contrast with the conventional MOHHO, MOSPO, MOGWO, and MOGOA.

-

The proposed methodology has significant implications for stakeholders in the renewable energy sector, offering a robust framework for optimizing wind turbine allocation and improving network performance in distribution systems.

-

Stochastic multi-objective allocation of WTs integrated with hydrogen storage in large distribution networks is suggested for future work incorporating the forecasted data based on the machine learning algorithms.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Silveira, C. L. B., Tabares, A., Faria, L. T. & Franco, J. F. Mathematical optimization versus metaheuristic techniques: a performance comparison for reconfiguration of distribution systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 196, 107272 (2021).

Miller, M., Paternina, J. L., Contreras, S. F., Cortes, C. A. & Myrzik, J. M. Optimal allocation of renewable energy systems in a weak distribution network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 235, 110649 (2024).

Fu, J. et al. A novel optimization strategy for line loss reduction in distribution networks with large penetration of distributed generation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 150, 109112 (2023).

Avar, A. & Ghanbari, E. Optimal integration and planning of PV and wind renewable energy sources into distribution networks using the hybrid model of analytical techniques and metaheuristic algorithms: a deep learning-based approach. Comput. Electr. Eng. 117, 109280 (2024).

Ahmed, A. et al. Probabilistic generation model for optimal allocation of wind DG in distribution systems with time varying load models. Sustainable Energy Grids Networks. 22, 100358 (2020).

Naderipour, A. et al. Deterministic and probabilistic multi-objective placement and sizing of wind renewable energy sources using improved spotted hyena optimizer. J. Clean. Prod. 286, 124941 (2021).

Davoudkhani, I. F., Dejamkhooy, A. & Nowdeh, S. A. A novel cloud-based framework for optimal design of stand-alone hybrid renewable energy system considering uncertainty and battery aging. Appl. Energy. 344, 121257 (2023).

Kamal, M. et al. Photovoltaic/Hydrokinetic/Hydrogen Energy System sizing considering uncertainty: a Stochastic Approach using two-point Estimate Method and Improved Gradient-Based Optimizer. Sustainability. 15 (21), 15622 (2023).

Nowdeh, S. A. et al. Fuzzy multi-objective placement of renewable energy sources in distribution system with objective of loss reduction and reliability improvement using a novel hybrid method. Appl. Soft Comput. 77, 761–779 (2019).

Arulraj, R. & Kumarappan, N. Optimal economic-driven planning of multiple DG and capacitor in distribution network considering different compensation coefficients in feeder’s failure rate evaluation. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 22 (1), 67–77 (2019).

Ali, E. S., Elazim, A., Abdelaziz, A. Y. & S. M., & Ant lion optimization algorithm for optimal location and sizing of renewable distributed generations. Renew. Energy. 101, 1311–1324 (2017).

Fan, G., Li, M., Chen, X., Dong, X. & Jermsittiparsert, K. Analysis of a multi-objective hybrid system to generate power in different environmental conditions based on improved the barnacles mating optimizer Algorithm. Energy Rep. 7, 2950–2961 (2021).

Bhargava, V., Sinha, S. K. & Dave, M. P. Co-ordinated optimal control of distributed generation in primary distribution system in presence of solar PV for loss reduction and voltage profile improvement. Energ. Syst., pp.1–21 (2021).

Jafari, A., Ganjehlou, H. G., Darbandi, F. B., Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. & Abapour, M. Dynamic and multi-objective reconfiguration of distribution network using a novel hybrid algorithm with parallel processing capability. Appl. Soft Comput. 90, 106146 (2020).

Moghaddam, M. J. H. et al. A new model for reconfiguration and distributed generation allocation in distribution network considering power quality indices and network losses. IEEE Syst. J. 14 (3), 3530–3538 (2020).

Essallah, S. & Khedher, A. Optimization of distribution system operation by network reconfiguration and DG integration using MPSO algorithm. Renew. Energy Focus. 34, 37–46 (2020).

Shen, H. et al. Multi-objective capacity configuration optimization of an integrated energy system considering economy and environment with harvest heat. Energy. Conv. Manag. 269, 116116 (2022).

Tolba, M. A., Rezk, H., Al-Dhaifallah, M. & Eisa, A. A. Heuristic optimization techniques for connecting renewable distributed generators on distribution grids. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 14195–14225 (2020).

Maji, S. & Kayal, P. A simplified multi-objective planning approach for allocation of distributed PV generators in unbalanced power distribution systems. Renew. Energy Focus. 48, 100541 (2024).

Huan, J. et al. Multi-objective Capacity Estimation of wind-solar-energy Storage in Power grid Planning Consideration Policy Effect (IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution, 2024).

Abid, M. S., Apon, H. J., Nafi, I. M., Ahmed, A. & Ahshan, R. Multi-objective architecture for strategic integration of distributed energy resources and battery storage system in microgrids. J. Energy Storage. 72, 108276 (2023).

Feng, L. et al. Robust operation of distribution network based on photovoltaic/wind energy resources in condition of COVID-19 pandemic considering deterministic and probabilistic approaches. Energy. 261, 125322 (2022).

Ghaffari, A., Askarzadeh, A. & Fadaeinedjad, R. Optimal allocation of energy storage systems, wind turbines and photovoltaic systems in distribution network considering flicker mitigation. Appl. Energy. 319, 119253 (2022).

Fathi, R., Tousi, B. & Galvani, S. Allocation of renewable resources with radial distribution network reconfiguration using improved salp swarm algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 132, 109828 (2023).

Belbachir, N., Kamel, S., Hassan, M. H. & Zellagui, M. Optimizing energy management of hybrid wind generation-battery energy storage units with long-term memory artificial hummingbird algorithm under daily load-source uncertainties in electrical networks. J. Energy Storage. 78, 110288 (2024).

Ramadan, A., Ebeed, M., Kamel, S., Ahmed, E. M. & Tostado-Véliz, M. Optimal allocation of renewable DGs using artificial hummingbird algorithm under uncertainty conditions. Ain Shams Eng. J. 14 (2), 101872 (2023).

Hemeida, M. G. et al. Optimal probabilistic location of DGs using Monte Carlo simulation based different bio-inspired algorithms. Ain Shams Eng. J. 12 (3), 2735–2762 (2021).

Mahmoud, E. et al. Impact of uncertainties in wind and solar energy to the optimal operation of DG based on MCS. Ain Shams Eng. J., p.102893 (2024).

Garcia-Martinez, C., Rodriguez, F. J. & Lozano, M. Arbitrary function optimisation with metaheuristics: no free lunch and real-world problems. Soft. Comput. 16, 2115–2133 (2012).

MiarNaeimi, F., Azizyan, G. & Rashki, M. Horse herd optimization algorithm: a nature-inspired algorithm for high-dimensional optimization problems. Knowl. Based Syst. 213, 106711 (2021).

Nowdeh, S. A., Naderipour, A., Davoudkhani, I. F. & Guerrero, J. M. Stochastic optimization–based economic design for a hybrid sustainable system of wind turbine, combined heat, and power generation, and electric and thermal storages considering uncertainty: A case study of Espoo, Finland. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 183, p.113440, (2023).

Mirjalili, S., Saremi, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Coelho, L. D. Multi-objective grey wolf optimizer: a novel algorithm for multi-criterion optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 47, 106–119 (2016).

Agushaka, J. O., Ezugwu, A. E. & Abualigah, L. Gazelle optimization algorithm: a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic optimizer. Neural Comput. Appl. 35 (5), 4099–4131 (2023).