Abstract

Traditional Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control systems often encounter challenges related to nonlinearity and time-variability. Original dung beetle optimizer (DBO) offers fast convergence and strong local exploitation capabilities. However, they are limited by poor exploration capabilities, imbalance between exploration and exploitation phases, and insufficient precision in global search. This paper proposes a novel adaptive PID control algorithm based on enhanced dung beetle optimizer (EDBO) and back propagation neural network (BPNN). Firstly, the diversity of exploration is increased by incorporating a merit-oriented mechanism into the rolling behavior. Then, a sine learning factor is introduced to balance the global exploration and local exploitation capabilities. Additionally, a dynamic spiral search strategy and adaptive \(t\)-distribution disturbance are presented to enhance search precision and global search capability. The BPNN is employed to fine-tune both PID and network parameters, leveraging its powerful generalization and learning ability to model nonlinear system dynamics. In the simplified motor experiments, the proposed controller achieved the lowest overshoot (0.5%) and the shortest response time (0.012 s), with a settling time of 0.02 s and a steady-state error of just 0.0010. In another set of experiments, the proposed controller recorded an overshoot and response time of 0.7% and 0.0010 s, across five DC motor tests. These results demonstrate the proposed adaptive PID control algorithm has superior performance in optimizing control system parameters, as well as improving system robustness and stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Literature review

The PID control algorithm has been used in industrial process control applications for many years1. Although the PID control algorithm has existed for a long time2, it is still the most popular control algorithm in the process and manufacturing industry today3. While effective in various industrial applications4, the traditional PID algorithm faces challenges with complex and nonlinear systems5. Parameter tuning often relies on trial and error6. Additionally, it lacks stability and robustness against disturbances and parameter changes7. In the context of DC motor control, traditional PI controllers have been widely applied and studied. However, traditional PI controllers also have limitations in managing nonlinearity and dynamic uncertainty, such as overshoot, response time delay, and difficulty in adjusting control parameters. These issues become more prominent in complex systems with different loads and speeds8.

Several studies have focused on improving the structure of the traditional PID controller by integrating neural networks and other advanced methodologies. Zhu et al. developed a hybrid-optimized BP neural network PID controller for agricultural applications, improving control performance by enhancing the efficiency of initial weights9. Maraba and Kuzucuoglu introduced a PID neural network controller for speed control of asynchronous motors, combining the benefits of artificial neural networks with the strengths of the classic PID controller10. Cong and Liang developed a nonlinear adaptive PID-like neural network controller using a mix of locally recurrent neural networks, enhancing the controller’s ability to adapt to nonlinear and time-variant system dynamics11. Ambroziak and Chojecki designed a PID controller optimized for air handling units (AHUs) by combining nonlinear autoregressive models, fuzzy logic, and FST-PSO metaheuristics, achieving superior performance in HVAC systems12. Aygun et al. presented a PSO-PID controller for regulating the bed temperature in a circulating fluidized bed boiler, leveraging the strengths of particle swarm optimization (PSO) to improve control precision13. Dahiya et al. proposed a hybrid gravitational search algorithm optimized PID and fractional-order PID (FOPID) controller to address the automatic generation control problem, demonstrating enhanced system stability and performance14. In recent years, several advanced PID variants have also been developed to handle nonlinear and complex systems. Suid and Ahmad designed a sigmoid-based PID (SPID) controller for the Automatic Voltage Regulator (AVR) system, employing a Nonlinear Sine Cosine Algorithm (NSCA) to optimize its parameters, which significantly improved the transient response and steady-state errors of the AVR system15. Sahin et al. proposed a sigmoid-based fractional-order PID (SFOPID) controller for the Automatic Voltage Regulator (AVR) system16. Ghazali et al. proposed a multiple-node hormone regulation neuroendocrine-PID (MnHR-NEPID) controller for nonlinear MIMO systems, improving control accuracy by introducing interactions between hormone regulation nodes based on adaptive safe experimentation dynamics (ASED)17. Kumar and Hote proposed a PIDA controller design using an improved coefficient diagram method (CDM) for load frequency control (LFC) of an isolated microgrid, enhancing control stability through maximum sensitivity constraints18.

Various optimization tools have been developed to dynamically adjust PID parameters for improved control performance. Shi et al. introduced the RBF-NPID algorithm, utilizing radial basis function (RBF) neural networks to dynamically adjust PID parameters, leading to more effective contrsol in complex systems19. Hanna et al. developed an adaptive PID algorithm (APIDC-QNN) that uses quantum neural networks combined with Lyapunov stability criteria for stable parameter optimization, enhancing system robustness20. Zhao and Gu proposed an adaptive PID method for car suspensions, where a radial basis function neural network is used to fine-tune the PID parameters, improving ride quality and suspension control21. Kebari et al. optimized PID parameter values based on real-time task demand and the cumulative sum of previous demands, providing a more responsive control system22. Similarly, Gupta et al. employed a hybrid swarm intelligence algorithm to adjust PID gains for stabilizing the active magnetic bearing (AMB) system under unstable conditions23. Faria et al. found that a PSO-based PID tuning strategy offers a practical solution for enhancing the effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) techniques, demonstrating the utility of swarm intelligence in medical applications24. Nanyan et al. proposed an improved Sine Cosine Algorithm (ISCA) to optimize PID controllers for DC-DC buck converters, demonstrating enhanced transient response and robustness compared to traditional algorithms25. Mourtas et al. utilized the beetle antennae search (BAS) algorithm for robust tuning of PID controllers, achieving superior performance in stabilizing feedback control systems with significantly reduced computational time26. Ghith and Tolba introduced a hybrid Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA) and Artificial Gorilla Troop Optimization (GTO) for tuning PID controllers in micro-robotics systems27.

Recent swarm intelligence algorithms28,29,30,31,32,33 have shown superior performance compared to traditional genetic algorithms34 and particle swarm optimization35. These novel algorithms effectively balance global exploration and local exploitation, featuring fast convergence and high solution accuracy, making them suitable for optimizing PID algorithm parameters driven by neural network models36,37,38,39. While significant advancements have been made in PID variants like the sigmoid-based fractional-order PID16 and multiple-node hormone regulation neuroendocrine-PID (MnHR-NEPID)17, which excel in specific application scenarios, the proposed control algorithm extends these capabilities by providing dynamic, real-time adjustments in complex control systems. This combination of enhanced search strategies and neural network integration allows for superior performance in scenarios that demand rapid responses and robust stability under parameter variations. The enhanced DBO incorporates a novel search state adjustment mechanism oriented towards preferred positions to enhance exploration diversity. It also introduces a sinusoidal learning factor to balance global exploration and local exploitation and adopts a dynamic spiral search method to improve search efficiency. To enhance population diversity and search accuracy, an adaptive \(t\)-distribution disturbance is used for more effective global search capabilities. In comparison to the conventional PI controllers, which often rely on fixed parameter settings and exhibit sensitivity to parameter uncertainties8, the proposed PID control algorithm offers dynamic adjustment capabilities and improved robustness. Through the incorporation of adaptive tuning mechanisms such as the merit-oriented search and sine learning factor, our approach addresses the overshoot, long response times, and tuning difficulties associated with traditional PI control methods. Additionally, the hybrid integration of the enhanced Dung Beetle Optimizer (EDBO) with Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) allows the system to handle nonlinear system dynamics more effectively, achieving faster response and lower steady-state errors in complex control systems such as DC motors.

Innovative contributions

Many controllers have been developed for industrial control processes in the existing literature and this study introduces new aspects that set it apart from the rest of the literature. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

Hybrid optimization algorithm framework. This study proposes a unique combination of the enhanced Dung Beetle Optimizer (EDBO) and Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) to optimize PID control parameters. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both heuristic algorithms and neural networks to enhance the optimization process.

-

Development of an enhanced Dung Beetle Optimizer. This study develops an enhanced DBO with a novel multi-strategy combined location update mechanism that addresses the limitations of traditional Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) by improving global search capability, local exploitation, and search precision.

-

Multistrategy innovations. EDBO incorporates a merit-oriented mechanism, a sine learning factor, a dynamic spiral search strategy, and adaptive \(t\)-distribution disturbance. These improvements ensure that EDBO is efficient and reliable when addressing complex optimization problems.

BPNN PID control algorithm

PID control

As a linear control method, PID control has the advantages of simple structure and easy implementation. The PID control law consists of three links: proportional control, integral control, and differential control, which is expressed as follows:

where \({K_p}\) is the proportional coefficient, \({T_i}\) is the integration time constant, and \({T_d}\) is the differential time constant. \(e(t)\) is the deviation signal of the system. \(u(t)\) is the control quantity of the system.

In actual operation, the control law is usually implemented using the incremental PID control algorithm. The basic structure of the PID control system is shown in Fig. 1.

The incremental PID control algorithm is expressed as follows:

where \(e(k)\) is the deviation value of the control system at the \(k\)-th sampling time. \(e(k - 1)\)is the deviation value of the control system at the \(k - 1\)st sampling time. \({K_p}\) is the proportional coefficient. \({K_i}\) is the integral coefficient, and \({K_d}\) is the differential coefficient. \(\Delta u(k)\) is the difference between the control quantity at the \(k\)-th sampling time and the \(k - 1\)st sampling time. The PID control law’s performance heavily depends on the tuning of its parameters. Traditional tuning methods, while effective, often require trade-offs between stability, responsiveness, and robustness.

According to the basic principles of PID control, proportional control accelerates the system’s response by reflecting the magnitude of the current error, enabling real-time adjustments that bring the system closer to the desired value. Integral control reduces accumulated past errors, thereby eliminating steady-state errors. The derivative term predicts future error trends, accelerating response times and minimizing overshoot. These three control actions combine to form a closed-loop PID control, which stabilizes the system. Accurate tuning of these parameters is key to ensuring controller stability. Therefore, this study focuses on optimizing these parameters to enhance system robustness and stability.

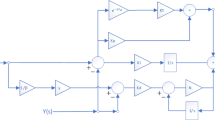

BPNN PID control

Back propagation neural network (BPNN) is one of the most utilized neural network models currently. BPNN deals with the arbitrary nonlinear relation between input and output variables by simulating the human brain’s intelligence. It shows incomparable advantages in complex model fitting and distribution approximation over the traditional statistical methods. The underlying reason may be that BPNN has self-learning and generalization ability, which constitute its high prediction accuracy, simple structure, self-organization, and self-adaptive capabilities. BP neural network can learn the system performance according to the operating status of the controlled system to achieve optimal PID control. The block diagram of the PID control structure based on BPNN is shown in Fig. 2.

The input signal \(r(k)\), deviation signal \(e(k)\), and actual output signal \(y(k)\) of the control system are used as the input of the BPNN. After being trained by the BPNN, the three parameters \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\) and \({K_d}\) are sent to the control system. Then, the \(u(k)\) is sent to the controlled object to realize the real-time online adjustment of three parameters. The BPNN structure is shown in Fig. 3.

In the figure, \(j\) represents the input layer, \(i\) represents the hidden layer, and \(l\) represents the output layer. The input layer neurons are \(r(k)\), \(e(k)\), and \(y(k)\). The output layer neurons are the three parameters of PID control \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\) and \({K_d}\). The output of each neuron in the input layer of the neural network \(O_{j}^{{(1)}}(k)\) is expressed as follows:

The input \(net_{i}^{{(2)}}(k)\) and output \(O_{i}^{{(2)}}(k)\) of each neuron in the hidden layer are represented as follows:

where \({w_{ij}}^{{(2)}}\) is the weight connecting the input layer neurons and the hidden layer neurons. \(f(x)\) is the activation function in the hidden layer, which is expressed as follows:

The input \(net_{l}^{{(3)}}(k)\) and output \(O_{l}^{{(3)}}(k)\) of each neuron in the output layer are represented as follows:

where \(w_{{li}}^{{(3)}}\) is the weight connecting the hidden layer neurons and the output layer neurons. \(g(x)\) is the activation function in the output layer.

The three output nodes of the output layer respectively correspond to \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\) and \({K_d}\). The activation function \(g(x)\) is expressed as follows:

The performance index function of the control system is defined as follows:

The weights of the neural network are adjusted using the gradient descent method, which iteratively updates the weights to minimize the error between the predicted and actual outputs.

Additionally, an inertia term is included in the weight adjustment process to accelerate convergence. The weight adjustment from the hidden layer to the output layer can be expressed as follows:

where \(\eta\) is the learning rate and \(\alpha\) is the inertia coefficient. According to the chain rule of derivatives, the gradient descent can be expressed as follows:

Finally, the learning algorithm for the weights of the output layer and hidden layer is obtained as follows:

where \(g^{\prime}(x)=g(x)(1 - g(x))\), \(f^{\prime}(x)=(1 - {f^2}(x))/2\), \(\eta\) is the learning rate of neural network and \(\alpha\) is the inertia coefficient of neural network.

Dung beetle optimizer

Basic dung beetle optimizer

The dung beetle optimizer (DBO) is a novel population based technique. It is inspired by the ball-rolling, dancing, foraging, stealing, and reproduction behaviors of dung beetles. The DBO algorithm considers both global exploration and local exploitation, thereby having the characteristics of a fast convergence rate and satisfactory solution accuracy in complex optimization problems across various research domains.

(1) Rolling behavior.

During the rolling process, the position of the ball-rolling dung beetle is updated and can be expressed as follows:

where \(t\) represents the current iteration number, \({x_i}(t)\) denotes the position information of the \(i\)th dung beetle at the \(t\)th iteration, \(k \in (0,0.2]\) denotes a constant value which indicates the deflection coefficient, \(b\)indicates a constant value belonging to (0, 1), \(\alpha\) is a natural coefficient which is assigned − 1 or 1, \({X^w}\) indicates the global worst position, \(\Delta x\) is used to simulate changes of light intensity. A conceptual model of a dung beetle’s rolling behavior is shown in Fig. 4.

(2) Dancing behavior.

To mimic the dance behavior, the tangent function is used to get the new rolling direction. The position of the ball-rolling dung beetle is updated and defined as follows:

where \(\theta\) is the deflection angle belonging to \([0,\pi ]\). Conceptual model of the tangent function and the dance behavior of a dung beetle is shown in Fig. 5. Once the dung beetle has successfully determined a new orientation, it should continue to roll the ball backward.

(3) Reproduction behavior.

A boundary selection strategy is proposed to simulate the areas where female dung beetles lay their eggs, which is defined by:

where \({X^ * }\) denotes the current local best position, \(L{b^ * }\)and \(U{b^ * }\) mean the lower and upper bounds of the spawning area respectively, \(R=1 - t/{T_{\hbox{max} }}\) and \({T_{\hbox{max} }}\) indicate the maximum iteration number, \(Lb\) and \(Ub\) represent the lower and upper bounds of the optimization problem, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6, the current local best position \({X^*}\) is indicated by using a large circle, while the small circles around \({X^*}\) indicate the brood balls. In addition, the small red circles represent the upper and lower bounds of the boundary.

The position of the brood ball is also dynamic in the iteration process, which is defined by:

where \({B_i}(t)\) is the position information of the \(i\)th brood ball at the \(t\)th iteration, \({b_1}\) and\({b_2}\)represent two independent random vectors by size \(1 \times D\), \(D\) indicates the dimension of the optimization problem.

(4) Foraging behavior.

The boundary of the optimal foraging area is defined as follows:

The position of the brood ball is also dynamic in the iteration process, which is defined by:

where \({X^b}\) denotes the global best position, \(L{b^b}\) and \(U{b^b}\) mean the lower and upper bounds of the optimal foraging area respectively. Therefore, the position of the small dung beetle is updated as follows:

where \({x_i}(t)\) indicates the position information of the \(i\)th small dung beetle at the \(t\)th iteration, \({C_1}\) represents a random number that follows normally distributed, and \({C_2}\) denotes a random vector belonging to (0, 1).

(5) Stealing behavior.

During the iteration process, the position information of the thief is updated and can be described as follows:

where \({x_i}(t)\) denotes the position information of the \(i\)th thief at the \(i\)th iteration, \(g\) is a random vector by size \(1 \times D\) that follows normally distributed, and \(S\) indicates a constant value.

Enhanced dung beetle optimizer

While the Basic Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) provides a foundation for global exploration and local exploitation, certain limitations such as susceptibility to local optima require enhancement for complex optimization tasks. To address these limitations, the Enhanced Dung Beetle Optimizer (EDBO) introduces advanced strategies that significantly improve performance and reliability.

The rolling behavior plays an important role in the DBO algorithm, but the dung beetle cannot communicate with other dung beetles when rolling the ball, which makes it easy to fall into a local optimal situation. Based on the original rolling ball behavior, a merit-oriented mechanism is introduced. When the dung beetle rolls the ball, it will select a nearby excellent position based on the current position as a guide for the rolling ball path. The new position of the ball-rolling dung beetle is defined as:

where \(h\) is a uniformly distributed random number with \(h \in (0,1)\). \({x_i}^{s}\) denotes the excellent position information of the \(i\)th dung beetle at the \(t\)th iteration, and \(i\) is a random number in the set \(\left\{ {1,2} \right\}\). The conceptual model of merit-oriented mechanism is shown in Fig. 7. The blue arrow indicates the final rolling direction.

Dancing behavior is an important exploration mechanism. To balance the ability of global exploration and local development, a sine learning factor \(r\) is introduced in the position update of dancing behavior. In the early iteration, the sine factor \(r\) can promote global exploration, whereas in the later iteration, it helps to refine local development and optimize search behavior at different stages. The sine learning factor and the new position equation for the dancing behavior are defined as:

where \({r_{\hbox{max} }}\) is the maximum value. \({r_{\hbox{min} }}\) is the minimum value. \(t\) represents the current iteration number, and \({T_{\hbox{max} }}\) represents the maximum iteration number.

To ensure the convergence speed of the algorithm and increase the diversity of individuals in the population, a dynamic spiral search method is proposed to improve the original breeding behavior. As the iteration proceeds, the shape of the spiral changes dynamically from large to small, and the dynamic nonlinear search mode helps to improve the population diversity and search accuracy of the entire search process. The proposed dynamic spiral search method is defined as follows:

where \(q\) is the spiral factor used to adjust the intensity of spiral search, \(l\) is a uniformly distributed random number with \(l \in ( - 1,1)\). The conceptual model of the dynamic spiral search method is shown in Fig. 8. The curves of the sine learning factor \(r\) and the spiral factor \(q\) are shown in Fig. 9.

In order to adapt to complex search spaces or multimodal problems, adaptive \(t\)-distribution disturbances with heavier tails than normal distributions are introduced. It is a probability distribution that achieves a smooth transition from Gaussian distribution to Cauchy distribution by adjusting its degree of freedom parameters. This adaptive approach enables the algorithm to dynamically adjust its search behavior, providing a more effective exploration of the solution space. The foraging behavior based on adaptive \(t\)-distributed disturbance is defined as follows:

where \(trnd\) is \(t\)-distribution function, the degrees of freedom in the distribution function represent disturbance probability, which changes dynamically with the number of iterations.

As the iteration proceeds, the concentration of the probability density reduces the variability of the perturbation values, and the perturbations are mainly generated around the current best solution. The probability density distribution heatmap and corresponding distribution function images of adaptive \(t\)-distribution disturbance at different iterations are shown in Fig. 10.

EDBO-BP hybrid optimization

Building upon the improvements introduced by the enhanced dung beetle optimizer, the integration with a BPNN further refines the optimization process. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both the EDBO and BP to deliver superior adaptability and precision in PID control systems.

To balance the speed and stability of the BPNN learning process, this paper employs the EDBO to globally optimize the learning rate and inertia coefficient. Hybrid optimization combining EDBO and BPNN is designed based on the BPNN PID control. The PID control structure optimized by the hybrid algorithm is shown in Fig. 11.

Application of EDBO-BP to tune the PID controller

BP neural networks (BPNN) have certain advantages in tuning PID controllers. Through the forward propagation of its input, hidden, and output layers, the values of \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\), and \({K_d}\) can be obtained. After applying the gradient descent algorithm, the weight coefficients of the neurons in each layer are adjusted through backpropagation, and then forward propagation is used again to obtain a new set of values. However, setting the learning rate and inertia coefficient is challenging, as these parameters significantly affect optimization results. In simulation experiments, it was found that these two parameters had a considerable impact on the results, which is why the Enhanced Dung Beetle Optimizer (EDBO) was introduced to adjust these two parameters of the BP neural network, forming the EDBO-BP-PID method. This method allows the algorithm to quickly find an optimal set of \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\), and \({K_d}\), which are then fed into the simulation model for ITAE (Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error) analysis. Based on changes in the fitness value, the superiority of the algorithm can be demonstrated.

The proposed algorithm formulates a mathematical model for the PID control system and defines its optimization objective. The optimization problem is centered around enhancing the PID control algorithm through the integration of EDBO and BPNN. The topology of the BPNN is determined. The EDBO algorithm initializes the network parameters. Then, parameter combinations are iteratively optimized. The EDBO algorithm adapts to real-time network performance. Finally, the BPNN and EDBO algorithms are applied alternately to globally optimize the PID parameter set. This hybrid optimization combines model-based optimization and data-driven learning. After defining the structure and optimization process of the BPNN, the fitness function of the EDBO is linked to the ITAE (Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error) as the objective function of the algorithm. During the optimization process, the position of the dung beetle corresponds to the PID parameters and network parameters to be optimized. The flowchart of the PID control algorithm with EDBO-BP is shown in Fig. 12.

In order to obtain satisfactory dynamic characteristics of the transition process, the system performance evaluation index ITAE is introduced as the objective function of the algorithm. ITAE is a widely accepted performance index for control systems. The discrete equation of the ITAE is expressed as follows:

where \(T\) is the sampling period and \(K\) is the sampling time.

Experiments and result analysis

EDBO performance test

Comparison of convergence curves

To show the convergence effect of each algorithm in test functions, the corresponding algorithm convergence curves were drawn according to the generated data. Figure 13 shows the fitness curves of EDBO and other algorithms in the optimization process of the partial benchmark functions. The comparison algorithm includes dung beetle optimizer (DBO), dwarf mongoose optimization algorithm (DMOA), marine predator algorithm (MPA), gazelle optimization algorithm (GOA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO). It can be seen that the EDBO was superior to other algorithms in terms of optimization speed and convergence accuracy.

Wilcoxon sign rank test

To further compare the differences between the EDBO and other optimization algorithms, a statistical test called the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted. The significance of the statistical results was determined by calculating the \(p\)-value. If the \(p\)-value was < 0.05, it was concluded that there was a significant difference between the two algorithms. The results of the calculation are shown in Table 1. Table 1 presents the performance differences between EDBO and other optimization algorithms, including dung beetle optimizer (DBO), dwarf mongoose optimization algorithm (DMOA), marine predator algorithm (MPA), gazelle optimization algorithm (GOA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO), across 23 benchmark functions. DBO, DMOA, MPA, and GOA are optimization algorithms recently proposed for addressing optimization problems, while PSO is a widely used classic optimization algorithm.

The results indicate that the proposed EDBO algorithm has a lower similarity in search outcomes compared to its competitors. Therefore, the optimization performance of the proposed EDBO across the 23 benchmark functions shows significant differences from other metaheuristic algorithms.

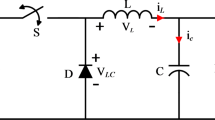

DC motor control system

The motor control system represents a quintessential and widely adopted paradigm within the realm of industrial control systems. To rigorously discuss and validate the efficacy of the control algorithm proposed in this paper, a DC motor control system has been selected as the controlled object for the simulation experiment. This choice is predicated on the DC motor’s prevalent application in various industrial scenarios due to its simplicity and robustness. The simplified DC motor model utilized is shown in Fig. 14.

The DC motor transfer function with armature voltage as input and speed as output can be expressed as:

The specific parameters of the DC motor mathematical model are shown in Table 2. Finally, the DC motor transfer function can be calculated as:

Results and analysis

The BP neural network takes \(r(k)\), \(e(k)\), and \(y(k)\) as inputs and predicts successive values of PID parameters. In the training process of the BPNN, data collection is first performed, including \(r(k)\), \(e(k)\), and \(y(k)\), and the optimal \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\), and \({K_d}\) values under various conditions. Then the BPNN is initialized with random weights, followed by backpropagation to compute the output of the network for each training sample. After that, error computation is carried out to measure the errors between the predicted and the actual optimal parameters of the PID parameters. Finally, the weights are adjusted using the gradient descent method to minimize the error. In the EDBO optimization process, a random location representing the candidate solution is initialized. The optimization is performed by multiple search strategies. BPNN and EDBO are used alternately to iteratively find the optimal PID parameters under different conditions.

The simulation scheme consists of implementing the BPNN and EDBO algorithms to optimize the PID parameters of the DC motor control system and simulating and testing the performance under various conditions including disturbances, step changes, and noise variations. The PID control system is modeled by Simulink. The BPNN structure for predicting the PID parameters is defined through .m files and the EDBO algorithm is implemented through .m files to optimize the BPNN. These codes work together to iteratively improve the PID parameters and the performance of the control system.

For the control group, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) and dung beetle optimizer (DBO) were selected as comparison targets. PSO is easy to implement and performs well in the optimal design of neural networks and PID control. Additionally, DBO serves as the foundation for the EDBO proposed in this paper. By comparing the performance of the control system optimized by the traditional DBO, the superiority of the proposed method can be verified.

Particle optimization trajectories for DBO and EDBO

This section aims to illustrate the improvements made by the EDBO in tuning PID parameters by comparing the optimization trajectories. By plotting the three-dimensional optimization trajectories of particles for the PID controller parameters \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\), and \({K_d}\), it visually explains why the original DBO tends to get trapped in local optima and how EDBO addresses this limitation. Representative runs of both the DBO and EDBO optimization algorithms were selected, each running for 100 iterations, with particle trajectories recorded in the \({K_p}\), \({K_i}\), and \({K_d}\) parameter space during each iteration. Three-dimensional scatter plots were then generated to showcase the differences in exploration and exploitation behaviors between the two algorithms.

From the three-dimensional trajectory plot of DBO, it is clear that the optimization particles quickly converge around \({K_i}=4\), indicating that DBO tends to get trapped in local optima. This premature convergence reduces the search range and limits the algorithm’s ability to find better solutions in the global search space. This behavior demonstrates the imbalance between the exploration and exploitation phases in the original DBO. In contrast, the optimization trajectory of EDBO shows a much broader search range, covering more areas in the parameter space. The particles do not converge prematurely at local optima, and the global exploration capability is significantly enhanced. The wider search range indicates that EDBO can overcome the local optima problem and significantly improve global optimization performance. The particle optimization trajectory of DBO is shown in Fig. 15, while that of EDBO is shown in Fig. 16.

Fitness convergence results

The ITAE fitness curve represents the cumulative weighted value of the error between the system output and the expected reference signal over time. By calculating the integral of the error and weighting it according to time, the overall performance of the control system can be comprehensively evaluated. The fitness value convergence curves are shown in Fig. 17.

DBO has the fastest initial convergence speed and quickly achieves a decrease in the value of the fitness function in the first five rounds of the search. In addition, as the number of iterations increases, EDBO can continue to identify new solutions that are better than the previous stage solution, which is manifested in the fitness value convergence curve sloping toward the lower right corner. The statistical results of the optimal, worst, mean, and standard deviation values of the fitness for each algorithm are given in Table 3.

EDBO achieved the smallest fitness value of 0.00028, followed by DBO with an optimal fitness of 0.00424. PSO obtained the highest fitness value. In terms of the worst fitness value, the worst fitness of the EDBO is 0.000776, which is significantly smaller than DBO and PSO. The above results show that the EDBO can achieve better control performance and stability than DBO and PSO in terms of global optimal solution identification ability, convergence speed, and performance robustness.

Parameter optimization results

Table 4 presents the tuning results of the three output layer parameters and the hyperparameters across 20 rounds of repeated experiments. By examining the best, worst, mean, and standard deviation values, the differences and performances of different algorithms in parameter optimization are highlighted.

Under the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm, the standard deviation of each parameter is relatively smaller, indicating that this algorithm can achieve more precise parameter tuning during the optimization process. In contrast, the DBO-BP-PID and PSO-BP-PID algorithms exhibit larger standard deviations, suggesting greater variability in their optimization processes. The reduced standard deviation in EDBO-BP-PID demonstrates its capability to consistently find parameter combinations close to the global optimum across multiple experiments, further proving its superior tuning performance.

Figures 18 and 19 respectively illustrate the tuning processes of PID parameters and neural network parameters over 100 iterations for the three algorithms. As shown in the figures, the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm quickly converges and maintains stability in the early stages of iteration. In contrast, while the DBO-BP-PID and PSO-BP-PID algorithms also converge rapidly initially, they exhibit significant fluctuations in parameter adjustments as iterations increase, making further optimization difficult.

In real industrial production processes, the stability, accuracy, and responsiveness of control systems are crucial. Due to its precise parameter adjustments during tuning, the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm better adapts to the demands of actual working environments and enhances the overall performance of the system. Specifically, by optimizing the hyperparameters of the neural network, the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm not only ensures control accuracy but also improves the system’s response speed and robustness, maintaining high control performance even in the face of disturbances and parameter variations.

EDBO-BP-PID algorithm achieves optimal tuning of the control system by seeking a balance among multiple performance indices. The principles of the ESO method are reflected in the EDBO-BP-PID’s optimization strategy, where a systematic adjustment mechanism ensures that the control system consistently delivers superior performance in complex and variable industrial environments.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is the study of uncertainty in the output of a mathematical model and how it is divided and assigned to different sources of uncertainty in the input. During the simulation experiment data is recorded and sensitivity analysis is performed, after traversing the two parameters such as learning rate \(\eta\) and inertia coefficient \(\alpha\) in the BP neural network, both of which are taken from 0 to 0.2, the relationship between the two parameters and the adaptation value is obtained and the sensitivity analysis graph of the parameters is shown in Fig. 20.

Therefore, the two parameters have a greater influence on the whole control system, and if they are set to a fixed value, it reduces the algorithm’s optimization-seeking effect, so we chose to adjust the parameters of the BP neural network with EDBO.

Control system performance results

In order to more fully verify the performance of the control algorithm in this paper, a series of performance evaluation experiments are further set up. Under the settings of the nondisturbance experiment, disturbance experiment, step change experiment, and noise variation experiment, the performance of the control algorithm such as step response state and error distribution are observed.

1) In this experiment, the control system is only affected by the predetermined set value, excluding all external disturbances, to observe the performance of the control strategy under ideal conditions. The step output response curve of the control system under the nondisturbance experimental setting is shown in Fig. 21. The error curve of the control system is shown in Fig. 22.

Table 5 shows the performance metrics of various control algorithms applied to the control system. These performance indicators are typical indicators used to evaluate the effectiveness of control systems.

In the EDBO-BP-PID control algorithms, the system can obtain the lowest overshoot value (0.5), the lowest rising time value (0.012), the lowest settling time value (0.02), the lowest peak value (1.005) and the lowest state error value (0.001), and in these five evaluation dimensions, the results of the remaining control groups are significantly different from the optimal results. Its peak time is slightly longer than DBO-BP-PID and PSO-BP-PID, indicating that although it may take longer to reach peak response, it can self-correct faster and have smaller overall errors.

Figures 21 and 22, and Table 5 show that the system under the EDBO-BP-PID control algorithm has better response speed, stability, and accuracy. It can achieve control requirements more effectively and improve control quality.

2) The amplitude of this disturbance is set to 20% of the system’s stable output value to represent a moderately strong external disturbance. The selection of this disturbance is based on some real industrial processes, such as chemical reactors and power systems, where disturbances of similar proportions may be experienced. Figures 23 and 24 show the results of the output response curve and error curve of different control algorithms in the control system when a disturbance is added.

Traditional PID control shows a large deviation. This is because traditional PID control is designed based on the mathematical model of the system. When external disturbances interfere with the system, traditional PID control cannot adjust the control quantity in a timely and accurate manner, causing the system to deviate from the desired trajectory. In contrast, the control algorithm proposed in this paper shows a more stable and accurate control effect.

The EDBO-BP-PID algorithm demonstrates optimal steady-state response and rapid error correction. After the disturbance, the system output shows minimal deviation from the setpoint and quickly returns to the desired output, highlighting its excellent disturbance rejection and system stability. In contrast, traditional PID and BP-PID algorithms exhibit larger overshoot and longer recovery times, with noticeable oscillations, especially in the PID controller, indicating its vulnerability to external disturbances.

While the PSO-BP-PID and DBO-BP-PID algorithms improve stability and recovery speed to some extent, they still fall short of the EDBO-BP-PID’s performance. These algorithms show some fluctuations in output response and less smooth error correction, indicating limited effectiveness in handling external disturbances.

3) In order to further evaluate the tracking ability of the control system to external changes and the robustness of the control algorithm, a step change experiment was set up on the system’s step response. Set the control system to simulate a step change at the 1st and 2nd seconds respectively. The input of the given system is 1. The dynamic behavior of the system output under different PID control algorithms when the system input undergoes a predetermined step change is shown in Fig. 25.

As shown in Fig. 25, there are significant differences in the dynamic behavior of the system output under various PID control algorithms when the system input undergoes step changes. The EDBO-BP-PID algorithm demonstrates the fastest response and the smallest overshoot at each step change point. The system output almost immediately follows the setpoint adjustment and stabilizes within a short time, showcasing its excellent tracking ability and strong robustness in response to external changes.

In contrast, traditional PID and BP-PID algorithms exhibit noticeable overshoots and oscillations when the step changes occur, particularly at the 1-second and 2-second step change points. The output signal shows a significant overshoot and takes longer to return to a stable state, indicating slower response speed and poorer stability when dealing with rapidly changing external inputs. While the PSO-BP-PID and DBO-BP-PID algorithms somewhat improve the overshoot issue, their response speed and final stability still do not match that of the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm.

4) In real industrial environments, control systems often need to operate in changing and unpredictable environments. Therefore, noise variation experiments are crucial to verify the effectiveness and robustness of control strategies. Introduce random noise signals into the control system to simulate the random interference that the control system may encounter in actual working conditions, and further evaluate the performance of the PID controller under nonideal and nondeterministic conditions. The noise signal is set to white noise with known statistical characteristics. The noise amplitude varies within the range of [0.95, 1.05]. The sampling time of the noise fluctuation is 0.001 s, and the simulation time of the entire system is set to 1 s. The system input after adding the external noise signal is shown in Fig. 26.

In Fig. 27, the system output performance under the influence of noise is shown for different PID control algorithms. The EDBO-BP-PID control algorithm demonstrates the smallest disturbance error when dealing with external noise, indicating its significant advantages in control accuracy and stability. Despite the noise interference, the system output quickly approaches the reference input value and maintains high stability. In contrast, other control algorithms, such as PID, BP-PID, PSO-BP-PID, and DBO-BP-PID, exhibit greater fluctuations under noise, with the traditional PID algorithm showing the most noticeable deviation.

Study case of DC motor with parameter uncertainties

Based on the previous model, the transfer function is replaced with a brushless DC motor simulation model. This model is characterized by nonlinearity and a complex control system, which is convenient to test the robustness of the proposed algorithm in this paper. Uncertainties such as changes in the desired speed of the motor and changes in the load of the motor are also introduced in the later experiments to analyze the following of the motor speed in this case. The brushless DC motor in this model is driven by an H-bridge, and four power tubes and an inductor are used to form an inverter circuit, with each phase of the windings being independent of each other, which can flexibly change the current size and direction of the windings.

After building the simulation model of a brushless DC motor, the effects of three algorithms such as BP-PID, DBO-BP-PID, and EDBO-BP-PID are compared. No-load acceleration and deceleration experiments, loaded acceleration and deceleration experiments, and uniform speed loading and unloading experiments of the motor were carried out to compare the motor speed following the three algorithms. The motor speed response curves of the controllers are shown in Figs. 28, 29, 30, 31 and 32. It can be concluded from the simulation experiments of the brushless DC motor that the motor speed response under the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm is faster and the overshoot is minimized, and the robustness is better than the other two algorithms.

A concise quantitative and qualitative comparative analysis of the experimental results is shown in Table 6. The quantitative analysis of five simulation experiments on DC motors concludes that the EDBO-BP-PID algorithm provides the best optimization of the PID controller parameters, with the lowest overshoot and the shortest response time of the control system.

Conclusions

This paper presents a PID control algorithm based on the hybrid optimization of the EDBO and BPNN. Unlike existing PID control systems, the proposed algorithm uses BPNN to identify parameter combinations without prior information on the PID control parameters. To alleviate overfitting and improve the generalization ability of the optimal parameter combination, EDBO incorporates enhanced strategies into the DBO. This approach optimizes the neural network parameters, enhancing the effectiveness and robustness of the overall optimization mechanism. Simulation experiment results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm offers faster and more accurate adjustment capabilities, improved control robustness, and greater practical usability.

The proposed adaptive PID control algorithm has broad application potential in industrial systems, robotics, and energy management. It can adjust PID parameters in real time to adapt to complex, nonlinear systems. This approach enhances precision in robotic motor control, allows for real-time adjustments in industrial automation, and ensures load frequency control in microgrids, providing robustness and stability under changing conditions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Clarke, D. W. PID algorithms and their computer implementation. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 6, 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/014233128400600605 (1984).

Wang, J. et al. PID control of multi-DOF industrial robot based on neural network. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput. 11, 6249–6260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-020-01693-w (2020).

Aboelhassan, A., Abdelgeliel, M., Zakzouk, E. E. & Galea, M. Design and implementation of model predictive control based PID controller for industrial applications. Energies. 13, 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246594 (2020).

Yang, T., Yi, X., Lu, S., Johansson, K. H. & Chai, T. Intelligent manufacturing for the process industry driven by industrial artificial intelligence. Engineering. 7, 1224–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.04.023 (2021).

Can, E. & Sayan, H. H. PID and fuzzy controlling three phase asynchronous machine by low level DC source three phase inverter. Teh Vjesn. 23, 753–760. https://doi.org/10.17559/TV-20150106105608 (2016).

Somefun, O. A., Akingbade, K. & Dahunsi, F. The dilemma of PID tuning. Annu. Rev. Control. 52, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2021.05.002 (2021).

Ding, X., Li, R., Cheng, Y., Liu, Q. & Liu, J. Design of and research into a multiple-fuzzy PID suspension control system based on road recognition. Processes. 9, 2190. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr9122190 (2021).

Saleem, O. EKF-based self-regulation of an adaptive nonlinear PI speed controller for a DC motor. Turkish J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 25, 4131–4141. https://doi.org/10.3906/elk-1611-311 (2017).

Zhu, F. et al. Research and design of hybrid optimized backpropagation (BP) neural network PID algorithm for integrated water and fertilizer precision fertilization control system for field crops. Agronomy. 13, 1423. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13051423 (2023).

Maraba, V. A. & Kuzucuoglu, A. E. PID neural network based speed control of asynchronous motor using programmable logic controller. Adv. Electr. Comput. Eng. 11, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.4316/aece.2011.04004 (2011).

Cong, S. & Liang, Y. PID-like neural network nonlinear adaptive control for uncertain multivariable motion control systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 56, 3872–3879. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2009.2018433 (2009).

Ambroziak, A. & Chojecki, A. The PID controller optimisation module using fuzzy self-tuning PSO for Air Handling Unit in continuous operation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 117, 105485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105485 (2023).

Aygun, H., Demirel, H. & Cernat, M. Control of the bed temperature of a circulating gluidized bed boiler by using particle swarm optimization. Adv. Electr. Comput. Eng. 12, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.4316/AECE.2012.02005 (2012).

Dahiya, P., Sharma, V. & Naresh, R. Solution approach to automatic generation control problem using hybridized gravitational search algorithm optimized PID and FOPID controllers. Adv. Electr. Comput. Eng. 15, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.4316/AECE.2015.02004 (2015).

Suid, M. H. & Ahmad, M. A. Optimal tuning of sigmoid PID controller using nonlinear sine cosine algorithm for the automatic voltage regulator system. ISA Trans. 128, 265–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.11.037 (2022).

Sahin, A. K., Cavdar, B. & Ayas, M. S. An adaptive fractional controller design for automatic voltage regulator system: sigmoid-based fractional-order PID controller. Neural Comput. Applic. 36, 14409–14431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-024-09816-6 (2024).

Ghazali, M. R., Ahmad, M. A. & Raja Ismail, R. M. T. A multiple-node hormone regulation of neuroendocrine-PID (MnHR-NEPID) control for nonlinear MIMO systems. IETE J. Res. 68, 4476–4491. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2020.1795939 (2020).

Kumar, M. & Hote, Y. V. Maximum sensitivity-constrained coefficient diagram method-based PIDA controller design: application for load frequency control of an isolated microgrid. Electr. Eng. 103, 2415–2429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-021-01226-4 (2021).

Shi, X., Zhao, H. & Fan, Z. Parameter optimization of nonlinear PID controller using RBF neural network for continuous stirred tank reactor. Meas. Control. 56, 1835–1843. https://doi.org/10.1177/00202940231189307 (2023).

Hanna, Y. F., Khater, A. A., El-Bardini, M. & El-Nagar, A. M. Real time adaptive PID controller based on quantum neural network for nonlinear systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 126, 106952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106952 (2023).

Zhao, W. & Gu, L. Adaptive PID controller for active suspension using radial basis function neural networks. Actuators. 12, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/act12120437 (2023).

Kebari, M., Wu, A. S. & Mathias, H. D. PID-inspired modifications in response threshold models in swarm intelligent systems. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, 39–46. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1145/3583131.3590442

Gupta, S., Debnath, S. & Biswas, P. K. Control of an active magnetic bearing system using swarm intelligence-based optimization techniques. Electr. Eng. 105, 935–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-022-01707-0 (2023).

Faria, R. M. et al. Particle swarm optimization solution for roll-off control in radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors: optimal search for PID controller tuning. PLOS ONE. 19, e0300445. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300445 (2024).

Nanyan, N. F., Ahmad, M. A. & Hekimoğlu, B. Optimal PID controller for the DC-DC Buck converter using the improved sine cosine algorithm. Results Control Optim. 14, 100352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rico.2023.100352 (2024).

Mourtas, S. D., Kasimis, C. & Katsikis, V. N. Robust PID controllers tuning based on the beetle antennae search algorithm. Memories – Mater. Devices Circuits Syst. 4, 100030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memori.2023.100030 (2023).

Ghith, E. S. & Tolba, F. A. A. tuning PID controllers based on hybrid arithmetic optimization algorithm and artificial gorilla troop optimization for micro-robotics systems. IEEE Access. 11, 27138–27154. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3258187 (2023).

Xue, J. & Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: a new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J. Supercomput. 79, 7305–7336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-022-04959-6 (2023).

Tang, J., Duan, H. & Lao, S. Swarm intelligence algorithms for multiple unmanned aerial vehicles collaboration: a comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 4295–4327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-022-10281-7 (2023).

Xu, M., Cao, L., Lu, D., Hu, Z. & Yue, Y. Application of swarm intelligence optimization algorithms in image processing: a comprehensive review of analysis, synthesis, and optimization. Biomimetics. 8, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8020235 (2023).

Tawhid, M. A. & Ibrahim, A. M. An efficient hybrid swarm intelligence optimization algorithm for solving nonlinear systems and clustering problems. Soft Comput. 27, 8867–8895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-022-07780-8 (2023).

Miao, Y. et al. Research on optimal control of HVAC system using swarm intelligence algorithms. Build. Environ. 241, 110467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110467 (2023).

Atacak, I. & Küçük, B. PSO-based PID controller design for an energy conversion system using compressed air. Teh Vjesn. 24, 671–679. https://doi.org/10.17559/TV-20150310170741 (2017).

Mirjalili, S. Genetic algorithm. In Evolutionary Algorithms and Neural Networks: Theory and Applications (ed Mirjalili, S.) 43–55 (Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93025-1_4. (2019).

Nayak, J., Swapnarekha, H., Naik, B., Dhiman, G. & Vimal, S. 25 years of particle swarm optimization: flourishing voyage of two decades. Arch. Computat Methods Eng. 30, 1663–1725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-022-09849-x (2023).

Chakraborty, A. & Kar, A. K. Swarm intelligence: a review of algorithms. In Nature-Inspired Computing and Optimization: Theory and Applications (eds Patnaik, S., Yang, X. S. & Nakamatsu, K.) 475–494 (Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50920-4_19. (2017).

Zhu, F. et al. Dung beetle optimization algorithm based on quantum computing and multi-strategy fusion for solving engineering problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121219 (2024).

Hasan, M. M., Rana, M. S., Tabassum, F., Pota, H. R. & Roni, M. H. K. optimizing the initial weights of a PID neural network controller for voltage stabilization of microgrids using a PEO-GA algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 147, 110771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110771 (2023).

He, Y., Zhou, Y., Wei, Y., Luo, Q. & Deng, W. Wind driven butterfly optimization algorithm with hybrid mechanism avoiding natural enemies for global optimization and PID controller design. J. Bionic Eng. 20, 2935–2972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42235-023-00416-z (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. SJCX23-1871, and No. KYCX24-XZ054); Yancheng Institute of Technology Teaching Reform Research Project (Grant No. YKT2022A028); The Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (Grant No. 24KJB140020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data collection, analysis, and interpretation, writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; methodology, formal analysis, W.K.; writing—review and editing, X.Y., Z.Y., R.W., W.Y., and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, W., Zhang, H., Yang, X. et al. PID control algorithm based on multistrategy enhanced dung beetle optimizer and back propagation neural network for DC motor control. Sci Rep 14, 28276 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79653-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79653-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Designing a cascaded exponential PID controller via starfish optimizer for DC motor and liquid level systems

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multi-fault diagnosis and damage assessment of rolling bearings based on IDBO-VMD and CNN-BiLSTM

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhanced PID controller tuning for nonlinear continuous stirred-tank heaters using a modified Newton-Raphson optimizer with random opposition and Lévy-flight learning

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Adaptive virtual impedance control strategy based on IWOA-fuzzy PID and its application to reactive power sharing in islanded microgrids

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Optimizing distributed generation allocation to minimize power loss in distribution systems using DBO-APCNN approach

Electrical Engineering (2025)