Abstract

COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) has emerged as a concerning complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, we explored the potential of phytochemicals and flavonoids identified through High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis of Thymus vulgaris plant extract against key proteins of CAM, namely heat shock protein A5 (GPR78) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). HPLC analysis revealed the presence of bioactive compounds, including chlorogenic acid, cinamic acid, quercetin, coumaric acid, gallic acid, and syringic acid. To assess their efficacy against CAM, computational analyses were performed, including molecular docking analysis, pharmacophore characterization, ADME and molecular dynamics simulations. The results demonstrated that chlorogenic acid exhibited strong binding affinity against EGFR with a docking score of -7.6 kcal/mol, while quercetin showed favorable binding affinity against HSP A5 (GPR78) with a docking score of -10.1 kcal/mol. Both chlorogenic acid and quercetin displayed promising ADME properties, indicating their potential as drug candidates. Nevertheless, it was observed that chlorogenic acid did not adhere to Lipinski’s rule, and its gastrointestinal (GI) absorption was relatively low when compared to quercetin. Unlike chlorogenic acid, quercetin does conform to Lipinski’s rule and showed high GI absorption. Moreover, pharmacophore characterization of both drug candidates revealed a substantial number of binding sites, suggesting the likelihood of stable bond formation. Normal mode analysis revealed higher eigenvalues for the quercetin–HSPA5 complex compared to the chlorogenic acid–EGFR complex, indicating greater structural rigidity and stability. Overall, our findings highlight the potential of chlorogenic acid and quercetin as promising drug candidates against CAM. Furthermore, in-vitro and in-vivo studies are needed to validate their efficacy and safety for clinical use in treating mucormycosis associated with COVID-19. These findings may offer valuable insights into the development of novel therapeutic options to combat this challenging co-infectious disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has had a significant impact on public health worldwide. Usually, COVID-19 infections are severe and affect the respiratory tract1. In addition to the main respiratory symptoms, there has been a concerning rise in secondary infection complications among individuals suffering from COVID-19. COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) is a serious and rare disease caused by fungi from the Mucorales family2. There is an increasing focus on mucormycosis due to its aggressive nature and high mortality rate. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and immunosuppressive therapy have been associated with an increased incidence of mucormycosis. CAM results when immunosuppression and COVID-19 are combined3. In COVID-19 patients, WHO emphasized the importance of infection prevention and control measures, antifungal medication use, and early detection and treatment of fungal infections4. In the past, patients with pre-existing conditions including diabetes, malignancies, and organ transplants were more likely to contract “Mucormycosis”. In the case of COVID-19, endothelial dysfunction, hyperglycemia, and immune dysfunction are all caused by viral infection5. A crucial role in “Mucormycosis” or “CAM” pathogenesis is played by the interactions between Mucorales spores and epithelial cells. COVID-19 infection of endothelial cells could potentially lead to a predisposition to CAM (Cell Adhesion Molecule) development, as it may result in endothelial damage and an elevated expression of endothelial receptors6. The application of corticosteroids may contribute to CAM development when COVID-19 causes direct damage to beta cells in the pancreas. For mucorales, iron acquisition from the host is an extremely important virulence characteristic. This is especially true in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or when receiving deferoxamine therapy7. Mucorales can also grow and invade due to the hyper-ferritinemia associated with COVID-19. It has been shown that corticosteroids suppress phagocytic cell immune function, contributes to the pathogenesis of CAM8.

Recent epidemiological studies highlight that COVID‑19–associated mucormycosis remains a significant global health concern. A systematic review and meta‑analysis of 958 CAM cases reported between January 2020 and December 2022 found that mucormycosis occurred on average 22 days after COVID‑19 diagnosis, with an overall mortality rate of 38.9%; 88.1% of cases were from low‑ or middle‑income countries, notably India, where at least 14 872 cases were documented by May 2021 and prevalence doubled in late 2020 compared to the previous year9. Although traditionally rare in Europe, a case series from Romania reported four CAM cases between 2021 and 2023 matching the seven pre‑pandemic cases in that region underscoring a worrying rise even in low‑incidence areas10. Moreover, emerging evidence of multiple fungal co‑infections—such as the first documented case of concurrent Rhizopus oryzae and Lomentospora prolificans infectionemphasizes the complexity of fungal pathogenesis in COVID‑19 patients and the need for heightened clinical vigilance11.

The glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), also known as heat shock protein A5 (HSP15) and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are crucial to both COVID-19 and mucormycosis infections12. In mucormycosis, EGFR mediates fungal invasion through its interaction with GRP78, which facilitates virus internalization. By reducing the expression of the ACE2 receptor, inhibiting GRP78 restricted SARS-CoV-2 internalization and virus binding in COVID-19. The use of drugs such as cetuximab or gefitinib which inhibit EGFR signaling may also improve survival in patients with pulmonary mucormycosis13. Notably, EGFR activation is essential to the pathogenesis of both diseases. This suggests that the activated EGFR induced by COVID-19 may exacerbate the binding of Mucorales spores, leading to the development of COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM)14. Among the medications used to treat mucormycosis are amphotericin B and posaconazole, both of which work against the fungal infection15. In addition to providing natural sources of antifungal compounds, plant metabolites obtained through HPLC analysis may be useful in the treatment of mucormycosis16. The efficacy of these plant metabolites in inhibiting the growth and virulence of Mucorales fungi can be explored, thus providing alternative therapeutic options for this challenging fungal infection. Studies have shown that several plant metabolites have antifungal properties, and are able to inhibit the growth of mucorales fungi17. Additionally, they can be used in combination with existing therapies to improve the efficacy of treatment and reduce the risk of drug resistance18.

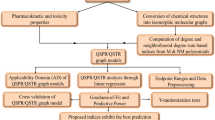

The major role of this research is to study the role of ligands retrieved from the HPLC of “Thymus Vulgaris” for the treatment of CAM. The validity of this study is confirmed through the identification of specific proteins, namely heat shock protein A5 (HSPA5) also known as GPR78 protein, and epidermal growth factor receptor protein (EGFR), both of which are linked to mucormycosis. To understand their characteristics, both proteins are then analyzed for their physiochemical properties. A potential ligand interaction site is predicted for both proteins, based on their binding sites. Based on the HPLC data, metabolites (ligands) with known bioactive properties are extracted from the plant. The binding affinity of these ligands is assessed by docking them with the targeted proteins. Furthermore, ADME analyses are performed on the selected ligands to determine their absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. Normal Mode Analysis (Molecular dynamics simulations) of ligand-protein complexes are conducted to study protein ligand dynamics behavior.

Material and methodology

Extraction method

The Thymus vulgaris leaf samples were dried at room temperature and 100 g of the leaves were grounded into a fine powder (100 g). The 50 g of dried powder samples of Thymus vulgaris were extracted with ethanol (300 ml) for seven days and by using a Soxhlet extractor, it was converted into semi-solid extract.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Phenolic compounds and flavonoids in a plant extract were quantitatively analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The analysis employed a CLC ODS C-18 column with dimensions of 2.5 cm in length and 4.6 mm in diameter, containing 5 μm diameter particles. The ethanol plant extract was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. A 20 µl volume of extract was mixed with a mobile phase consisting of two components: mobile phase A, composed of water and acetoacetate in a 94:6 ratio with a pH of 2.27, and mobile phase B, consisting of 100% acetonitrile. The HPLC conditions involved a gradient elution process. The elution started with 15% mobile phase B at 0 min, followed by a linear increase to 45% B from 15 to 30 min, and a final step to 100% B from 35 to 40 min. The flow rate was maintained at 1 ml/min, and UV-visible detector spectra were recorded at 280 nm for all samples19.

Retrieval of primary structure of proteins

The targeted protein of the CAM is the heat shock protein A5 (HSPA5) and epidermal growth factor response (EGFR) which was retrieved from UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/). The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) is a large database of protein sequences and functional information, including many entries coming from genome sequencing initiatives20. It offers a wealth of information drawn from scientific literature regarding the biological function of proteins.

Prediction of (3D) tertiary structure

The primary structure of the protein was modeled into the tertiary structure by the utilization of the SWISS-MODEL (http://swissmodel.expasy.org). The SWISS-MODEL Repository’s specific goal is to give users access to a current collection of high-quality, annotated 3D protein models, experimental structural data, and other sequences for relevant model organism proteomes21. Homology modeling of 3D protein structures, which is often utilized in several real-world applications, is currently the most precise technique for creating trustworthy three-dimensional protein structure models. The tertiary structure of the selected protein was visualized by the Discovery Studio Visualizer.

Expasy Protparam

For the calculation of the physiochemical properties of the selected protein, ExPASy-Protpram tool was utilized by ExPASy Bioinformatics Resource Portal (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) It is considered one of the best tools for the analysis of physical and chemical properties of proteins22,23. ProtParam computes the physicochemical characteristics of a protein sequence, such as amino acid composition, pl, atomic composition, extinction coefficient, instability and aliphatic index.

3D structure validation

PROCHECK is an online tool used for the validation of protein structures. The ProCheck tool (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/) was used to develop the Ramachandran plot which has favored and unfavored regions24. The stereochemical quality of the created model is defined by the software PROCHEK using Ramachandran plot analysis, and it was also approved by the ERRAT25.

Prediction of binding sites

Protein Plus Sever’s Dog site scorer tool (https://proteins.plus) was used to score the protein structure. A variety of algorithms are used by this tool to find possible binding pockets. These algorithms include geometrical characteristics, solvent accessibility, and residue conservation. The local physicochemical characteristics of the protein surface prevent these algorithms from detecting each residue’s chance of binding ligands. A molecular visualization tool was used to inspect the predicted binding pockets after the Dog site scorer analysis. As a result, it is possible to examine in depth the geometry of the probable binding sites and their proximity to recognized functional areas. Additional analysis, such as clustering predicted pockets or comparing with experimental data, can validate the predicted binding sites and rank them for later experimental validation or virtual ligand screening26.

Retrieval of ligands

After the HPLC analysis of plant phytochemicals; the identified phytochemicals 3D structures were retrieved. Seven phytochemicals and 2 Standard antiviral COVID-19 drugs (Favipiravir and Remdesivir) 3D structures were downloaded from PubChem in SDF format (Structure-data files) and SMILES files (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System)27. Computational tools and software were used for further analysis and processing of retrieved ligands, such as docking, virtual screening, ADME and pharmacophore characterization.

Multiple ligands docking

Docking of multiple ligands was performed using PyRx 0.8 version equipped with Autodock vina28. The proteins 3D structures were converted into PDBQT formats. After this ligand energies were minimized and all were converted into PDBQT format. With specific parameters set, PyRx’s docking workspace was imported with the protein structure and its ligands. Multiple conformations were generated for each ligand within the target protein’s binding site, ranked based on predicted binding affinity. Based on visual inspection and scoring functions, high-affinity ligand-receptor complexes were selected by analyzing the results. Docking with PyRx enabled efficient and accurate identification of potential lead compounds and provided insights into ligand binding modes.

Prediction of protein-ligand interaction

LIGPLOT + was used for the prediction of the protein-ligand interactions. It uses standard Protein Data Bank file input to produce schematic 2-D representations of protein-ligand complexes. For better visualization of molecular interaction analysis Biovia Discovery studio was utilized to check the hydrophobic regions in three dimensional scale and 2D molecular interactions29.

Pharmacophore characterization

Pharmacophore characterization of the lead ligand was performed by the Pharmit server (https://pharmit.csb.pitt.edu/search.html). The bonds between the ligand and its ability to accept and donate hydrogen were checked30.

ADME analysis

The SwissADME tool (http://www.swissadme.ch/) was used for the pre-clinical testing of a drug candidate quercetin and chlorogenic acid. This computational tool predicted pharmacokinetic properties. The medicinal properties and drug nature properties of drug candidates was also measured31.

Protein dynamics (molecular dynamic simulations)

Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) is a computational technique used to study the collective vibrations and flexibility of proteins and nucleic acids, providing insights into their structural dynamics. In this study, NMA was performed using the iMODs tool (https://imods.iqfr.csic.es/), which is designed for the analysis of large macromolecular structures based on internal coordinates32.

iMODs operates by analyzing the molecular structure of protein-ligand complexes to explore the low-frequency normal modes, which correspond to the most significant movements or deformations in the system. These modes are important as they represent biologically relevant motions that often correlate with functional flexibility in proteins.

Results

HPLC analysis

The quantitative analysis of the ethanol plant extracts is presented in Table 1. A representative chromatogram is shown in Fig. 1. The phytochemicals and flavonoids were identified in the extracted sample such as gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, coumaric acid, cinamic acid and quercetin.

Prediction of primary structure of proteins

The Uniprot (Universal Protein Portal) provided the primary structures of both proteins. The Heat shock protein A5 (HSPA5) was retrieved with the accession no P11021, comprised 654 amino acids. And the other protein epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15 (EGFR) comprised of 1048 amino acids along with the accession ID: S2JQ00.

Exasy Protparam

The physicochemical properties of both the selected proteins EGFR and HSPA5 were predicted by ExPASy-ProtParam. The prediction of the molecular weight of the specific drug construct was found to be 112488.29Da, 7332.96Da. The Theoretical Isoelectric Point Values (PI) are 4.66, 5.07. The instability index (II) for the protein was predicted as 60.60 of the EGFR and 32.10 of the HSPA5. The estimation of the aliphatic index was about 63.18 and 85.70, confirming its thermostability. The prediction of the Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY) is to be about − 0.586 and − 0.487, respectively (Table 2).

Prediction of (3D) tertiary structure

The tertiary structure of the selected target proteins EGFR and HSPA5 was analyzed by the Swiss Model. For both proteins Model 1 was selected to download in PDB format having good quarry and identity score along with GMQE (Global Model Quality Estimate) of about 0.57, and the other one is 0.72. Figure 2 depicts the protein’s projected tertiary structures.

3D structure validation

The 3D structure validation of the targeted proteins was predicted through PROCHECK. The ERRAT quality factor of EGFR is 78.5714, and for the HSPA5 is 93.1373 (Fig. 3). Ramachandran Plot validates the residues on the base of favoured region or non-favoured region. For the EGFR protein statistics showed that 76.4% of residues are in the most favored region, 17.8% residues in the additional allowed region, 3.2% residues in generously allowed regions, and 2.6% residues in disallowed regions. HSPA5 Ramachandran plot statistics showed that 93.4% of residues are in the most favoured region, 5.9% residues in the additional allowed region,0.5% residues in generously allowed regions, and 0.2% residues in disallowed regions. So, the HSPA5 protein shows above 90% protein validation score so which means this protein is perfect and can be used for further analysis instead of EGFR as shown in Fig. 4.

Prediction of the binding sites

Portein Plus predicted 25 binding pockets for “HSPA5”. The active site selection was based on the pocket with the highest volume and surface area, which was 3003.98 nm3 and 3399.07 A2, respectively shown in Fig. 5 (A). The selected Active site was comprised of 654 residues. While, PROTEIN PLUS also predicted 25 binding pockets for protein “EGFR” with 2226.98 nm3 volume and 3296.94 A2 surface area. This aactive consists of 70 residues shown in Fig. 5 (B).

Retrival of ligands

All of the compounds identififed through HPLC analysis of the Thymus vulgaris ethanoli extract were selected as a ligand such as Chlorogenic acid, Cinamic acid, Coumaric acid, Ferulic acid, Gallic acid, Quercitin and Syringic acid and retreived through PubChen having Compound CID 1794427, 5372020, 9840292, 445858, 370, 5280343 and 10742 were succesfeuly downloaded as a SDF and converted into PDB format for further analysis.

Multiple ligand Docking

In order to derive the lead compound based upon binding affinity, 7 selected compounds and 2 standardard antiviral drugs (Favipiravir and Remdesivir) were docked with Protein HSPA5 and EGFR. On the basis of binding affinities of both proteins with ligands, docked complex will be slected for further analysis. Energy levels variate from − 5.1 to 10.1 kcal/mol. The compound Quercitin and chlorogenic acid had been chosen as the best candidate with the lowest binding affinity of -10.1 and − 9.8 kcal/mol respectively with toxin protein “HSPA5” while the standard antiviral drugs (Favipiravir and Remdesivir) showed the binding affinity of -6.6 and − 7.2 kcal/mol. the EGFR sowed best binding affinity with same compounds Quercetin and Chlorogenic acid having − 6.9 and − 7.6 kcal/mol and with standard antiviral drugs (Favipiravir and Remdesivir) a binding affinity of -5.5 and − 6.9 kcal/mol respectivley. The list of binding affinities of docked complexes are shown in Table 3.

Prediction of protein-ligand interaction

To analyze the molecular interactions of the best-docked complex of chlorogenic acid with EGFR and quercetin with HSPA5 protein, LIGPLOT + was utilized. The quercetin docked complex show hydrogen bonding with Lys96, Asp34, Asp391, Thr37, Gly227, Ser365 residues and hydrophobic interactions with Thr299, Gly227, Val394, Gly36, Glu201, Gly226, Gly363, Gly364, Arg297. The hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions of chlorogenic acid docked complex with EGFR is shown in Table 4. The Fig. 6 depicts the protein-ligand interaction and residues that are not directly involved in the interaction due to the greater bond angle. These depicted red interactions are hydrophobic in nature while blue bonds are hydrogen bonds. The more detailed 2D and 3D molecular interactions of the docked complexes is shown in Fig. 7.

Docked complex with high binding affinities (A) showing the 3D structure of interaction between quercetin with HSPA5 while (B) shows the 2D diagram of the docked complex. (C) Showing the 3D structure of interaction between chlorogenic acid with EGFR while (D) shows the 2D diagram of the docked complex.

Pharmacophore characterization

The pharmacophore characterization of the ligand can be seen in the Fig. 7. The chlorogenic acid contains 7 hydrogen acceptors, 1 aromatic, 1 negative ion and 1 hydrophobic bond forming sites. Whereas, quercetin contain 6 hydrogen bond acceptor and 3 aromatic bonds forming sites. Both the ligand was rich in pharmacophore sites and had good potential to bond with the receptor, forming a good number of interactions as shown in Fig. 8.

Pharmacophore characterization of chlorogenic acid and quercetin compound. (A) Chlorogenic acid (B) Quercetin. The sites that can form bonds are seen in circles. These atoms (sites) form bonds with the targeted compound. The green circles are the sites that represent the hydrophobic interactions, the yellow circles are the sites that represent the hydrogen acceptor, the red circle is the site that represents the negative ion force and the purple circle is the site that represents the aromatic force.

ADME analysis

The SWISS-ADME analysis revealed that quercetin follows Lipinski’s rule of five and has a lipophilicity of 1.63. It contains 7 number of hydrogen bond acceptor and 5 number of hydrogen bond donor. In contrast, chlorogenic acid does not follow Lipinski’s rule as it contains number of hydrogen bond acceptor and donor greater than 10 and have good lipophilicity value 0.87. Quercetin consists of high GI absorption whereas chlorogenic acid has low GI-absorption as shown in Table 5. Radar plot, which indicates that all the compounds were within the ranges of the physicochemical properties and that these compounds are suitable for oral administration. The results of these calculations largely correspond to their observed lipophilicity and water-solubility (Fig. 9). The boiled egg model showed blood brain barrier and gastrointestinal absorption, which was extremely helpful for creating and administering drugs. As shown in Fig. 10.

BOILED-Egg image of chlorogenic acid. The yellow region shows a high probability of blood brain barrier penetration, the white region shows high permeability of passive absorption by the gastrointestinal tract and the red dot shows the molecule is P-gp – means it’s not the substrate of P-gp. As shown in (A), the molecule is in the white region shows that gastrointestinal (GI) absorption and (B) shows that it cannot cross the GI track.

Protein dynamics (molecular dynamic simulations)

The docked conformation of quercetin within the HSPA5 binding pocket. The deformability profile shows uniformly low peaks across all residue indices, indicating minimal local flexibility and a highly stable complex. Consistent with this, the B‑factor plot reveals limited atomic fluctuations when comparing the NMA‑derived mobility (red) to the crystallographic B‑factors (gray). The eigenvalue distribution yields a first-mode eigenvalue of 1.935 × 10⁻⁶, reflecting the energy barrier to the initial deformation of the complex, and suggesting that greater energy is required to induce structural changes in HSPA5 compared to EGFR. variance plot demonstrates that the lowest‐frequency modes capture the bulk of the collective motions, while higher modes contribute progressively smaller fractions of the total variance. The covariance matrix highlights regions of correlated (red) and anti‑correlated (blue) residue motions, suggesting concerted domain movements upon ligand binding. Finally, the elastic network model maps inter‑atomic “springs,” with dot intensity proportional to interaction stiffness, underscoring a robust network of contacts that likely underpins the complex’s structural rigidity. The elastic network model defined the pairs of atoms connected by springs, where dots are colored according to the degree of stiffness. These all results can be seen in Fig. 11.

The predicted binding pose of chlorogenic acid in the EGFR active site. The deformability curve again exhibits low amplitude across all residues, signifying constrained flexibility throughout the protein. The NMA‑derived B‑factor profile (red) aligns closely with the experimental B‑factors (gray), indicating that most regions maintain moderate stability with only a few loop segments showing enhanced mobility. The eigenvalue plot reports a first-mode eigenvalue of 3.287 × 10⁻⁷, which is lower than that of the quercetin–HSPA5 complex. This suggests that the EGFR complex requires less energy to deform, making it comparatively more pliable. The variance analysis confirms that the initial normal modes dominate the dynamic behavior, capturing the majority of the motion, with subsequent modes contributing smaller increments. Covariance heatmap reveals distinct clusters of correlated motions, while the elastic network representation a dense array of springs, with color gradations denoting variations in stiffness together portraying the intricate mechanical coupling within the complex. These all results can be seen in Fig. 12.

NMA of the quercetin docked with HSPA5 (A) shows the docked compound (B) shows the deformability, which indicates a low level of deformation at all the residues (C) shows the B-factor, (D) Eigen values are shown, and (E) indicates the variance explained in both red and green (F) and (G) show the covariance and elastic network of the complex.

NMA of the chlorogenic acid docked with EGFR (A) shows the docked compound (B) shows the deformability, which indicates a low level of deformation at all the residues (C) shows the B-factor, (D) Eigen values are shown, and (E) indicates the variance explained in both red and green (F) and (G) show the covariance and elastic network of the complex.

Discussion

The mortality and risk associated with SARS-CoV-2 have been found to be much higher than initially estimated. This virus has demonstrated evolutionary adaptability, suggesting its potential to persist in its current form or evolve into new variants over several years33. As long as SARS-CoV-2 continues to circulate, the risk of mucormycosis infections remains a significant concern34. This paper explores the potential of phytochemicals as a possible approach to combat mucormycosis. The unique properties of these compounds may hold promise in addressing the challenges posed by mucormycosis infections and could offer a new avenue for therapeutic intervention.

The emergence of mucormycosis as a secondary infection in COVID-19 patients has raised serious concerns, necessitating the search for novel therapeutic options4. Thymus vulgaris (thyme) is known for its rich bioactive content and potential medicinal properties35. In this study, we employed High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to identify bioactive compounds present in the ethanolic extract of Thymus vulgaris that could potentially target two key proteins associated with mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients heat shock protein A5 (HSPA5) and epidermal growth factor response (EGFR). The response of patients with COVID-19-associated mucormycosis to various antifungal agents is influenced by both the specific sites of infection and the characteristics of the host. This response can vary depending on these factors. In the pandemic, it is major concern as many patients have multiple morbidities such as immunocompromised, diabetes and hematological malignancies36. Henceforth, drug treatment with host dependent should be considered for the management of the mucormycosis.

Medicinal plants play a significant pharmacological role in combating fungal diseases, including anti-fungal infections. This is due to their rich reservoir of bioactive compounds, which possess properties that can effectively inhibit the growth and activity of fungal pathogens. These bioactive compounds, such as alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and essential oils, exhibit various mechanisms of action against fungi37. Thymus vulgaris contain bioactive compound such as phenolics, terpenoids, terpenins and flavonoids which contain number of pharmacological activities such as anti-cancerous, anti-hemolytic, anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory38. A study conducted by Saleem et al., (2022) has reported the biological activities of the Thymus vulgaris plant extract and result shows that the bioactive compounds of Thymus vulgaris exhibit great potential as a anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-thrombolytic and anti-hemolytic activity under the safe range that is less than 10 mg/ml19.

The Glucose Regulated Protein 78 (GRP78) also known as heat shock protein A5 (HSPA5) acts as the co-receptor for the spike protein of the SARS-CoV239. It increases the invasion of the virus and has a metabolic role in regulating the protein stability, unfolded the protein response, autophagy and calcium homeostasis40. It also acts as the receptor for the CotH protein which is mainly expressed by the group of fungi of mucoralse, the cusative agent of mucromycosis41. Coth3 protein then interacts with the integrin β1 receptor, thus causing the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor which mediates the invasion of the fungi into the host cells42. Moreover, in the case of pulmonary mucromycosis and COVID-19 infection, EGFR activation is important for the pathogenesis of the infection. The experimental evidences suggest that the inhibition of the GPR78 and EGFR may inhibit the fibrotic response to coronavirus lead to the reduced viral load and severity of infection43. Hence, targeting GPR78 (HSPA5) and EGFR may offer a new active antifungal approach to treat CAM.

The docking results revealed the binding affinities and interaction patterns of each identified compound with the target proteins. Compounds that exhibited strong binding affinities and formed crucial hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and other key interactions with the active sites of the proteins were considered potential candidates for further investigation44. Molecular docking analysis showed that chlorogenic acid and quercetin exhibited strong binding affinities against HSPA5 and EGFR ranges from − 7.6 to -10.1 kcal/mol. Chlorogenic acid shows − 7.6 kcal/mol energy against EGFR and molecular interaction shows that it forms strong covalent bond, hydrogen bond, hydrophobic bond at the binding site of the targeted protein. On the other hand, quercetin shows high binding affinity with HSPA5 (GPR78) protein with docking score of -10.1 and make strong covalent as well as pi-alkyl bond with the amino acid residues of the protein at the binding site. Moreover, the pharmacophore characterization shows that chlorogenic acid and quercetin consist of high number of binding sites to form stable complex with the targeted proteins. A study was conducted the examine the potential of garlic phytoconstituents against 1,3-beta-glucan synthase fungal protein and result shows that Z-ajoene showed the highest binding energy of -5.0 kcal/mol45.

Furthermore, the association of our results with standardized antivirals needs to be elucidated. In a detailed study of pearl millet phytochemicals targeting SARS‑CoV‑2 RNA‑dependent RNA polymerase, luteolin, apigenin, and quercetin came as most potent inhibitors having the highest docking scores approximately equal to -5.9 kcal/mol, and ADME plus chemical‑protein network analyses have duly ascertained their oral bioavailability and interactions with CYP1A1/CYP1B1 while the second one unearthed quercetin and epicatechin as an active portion of thirteen orally active leads among finger millet compounds with binding affinities up to − 7.6 kcal/mol and showing favorable pharmacokinetic profiles46,47. The third one was able to virtual screen natural compounds with the Cryo‑EM structure of the SARS‑CoV‑2 Omicron spike protein, and it revealed aloe‑emodin and sinapic acid as the moderate affinities’ binders (–3.6 and − 2.8 kcal/mol) and the theoretical good oral pharmacokinetics48. Explaining further, our virtual screening of the docking of quercetin and chlorogenic acid from Thymus vulgaris to the host receptors HSPA5 and EGFR displayed dramatically much better affinities (–10.1/–9.8 kcal/mol and − 6.9/–7.6 kcal/mol, respectively), so it can be assumed that these phytochemicals lead to more effective regulation of host pathways that are key to COVID‑19‑associated mucormycosis.

The drug likeness analysis for chlorogenic acid shows that it has good ADME properties with lipophilicity less than 5, high water solubility but does not follow Lipinski’s rule of five. Quercetin shows as a more favorable drug candidate than chlorogenic acid due to its excellent ADME properties. Quercetin shows a notable combination of factors, including high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, a lipophilicity index of 1.8, and high-water solubility. Importantly, it adheres to all five of Lipinski’s rules, signifying its compliance with criteria such as having a molecular weight below 500 and hydrogen bond acceptor and donor groups less than 1049. A study conducted to investigate the effects of considering marine-sponge based antifungal compounds inhibiting the CAM by targeting CotH3 and muricin protein. The results show that all group of compound exhibit some sort of toxicity such as naamines exhibit hepatotoxic effect and cause skin sensitization50. Our results show that chlorogenic acid and quercetin does not cause any hepatotoxicity and skin sensitization which makes them the strong drug candidate for the treatment of CAM.

The ADME and network analyses showed that luteolin and quercetin are orally bioavailable drugs by Raushan Kumar Jha et al., while quercetin and related phenolics were safe, orally active leads47. Also, in this case, they adhered to the lipophilic property but were out of the drug-likeness rules. Similarly, our ADME test has confirmed that quercetin is within Lipinski’s rule of five, has good absorption through the intestine, and is lipophilic (log P 1.8). Chlorogenic acid also overreaches a few parameters that Lipinski proposed. Nevertheless, it is highly soluble in water corresponding to the findings, where certain phenolic acids were vigorously binding but displayed little relevancy to drug-likeness47. Comparing with the points just made, it can be said that the mentioned Thymus vulgaris phytochemicals are trustworthy as they are bi-functional in their role, that is, are potent binders not just in viral‑associated but also in fungal‑associated targets and have a part in the drug metabolism and transport system. This versatility makes them promising candidates for drug development.

The molecular dynamics-based Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) provided more profound insights into the stability and flexibility of the docked complexes, strengthening our in-silico findings. For the quercetin–HSPA5 complex, the deformability plot revealed minimal fluctuations across residue indices, indicating strong structural rigidity and minimal local flexibility. This was further supported by the low amplitude B-factor profile, suggesting limited atomic mobility upon ligand binding. The high eigenvalue (1.935 × 10⁻⁶) reflects the substantial energy barrier required to deform the complex, reinforcing its stability. Similarly, the variance and covariance analyses confirmed dominant collective motions and coordinated domain dynamics, respectively, indicating robust interactions and mechanical integrity. On the other hand, the chlorogenic acid–EGFR complex, while stable, exhibited a slightly lower eigenvalue (3.287 × 10⁻⁷), suggesting more excellent conformational pliability. However, the elastic network model still displayed a dense spring distribution, pointing to consistent intramolecular contacts. These MD-derived descriptors play a crucial role in our research as they validate the docking results. They confirm that both lead compounds form energetically favorable and dynamically stable complexes with their respective targets, enhancing the credibility of our findings.

This study shows that quercetin and chlorogenic acid exhibit great potential as a drug candidate against COVID-19 associated mucormycosis. However, in-vitro and in-vivo studies are required to confirm the inhibitory effects of the chlorogenic acid and quercetin against CAM. In conclusion, the HPLC-based analysis of Thymus vulgaris ethanolic extract combined with molecular docking simulations has offered a starting point for the discovery of bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic relevance against COVID-19 associated mucormycosis. Phytochemicals and flavonoids have the potential to act as encouraging primary drug candidates, that could pave the ways for drug development to address this significant secondary infection observed in patients with COVID-19.

Conclusion

The current study explored the potential of phytochemicals and flavonoids obtained from Thymus vulgaris plant extract against heat shock protein A5 (GPR78) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) protein that cause pathogenesis of the COVID-19 associated mucormycosis (CAM). Among the identified compounds, quercetin and chlorogenic acid exhibited remarkable potential as a drug candidate for CAM treatment as they show high binding affinities against the targeted proteins and favorable ADME analysis shows that these two compounds exhibit the properties of the drug candidate. Furthermore, pharmacophore characterization revealed a high number of binding sites for quercetin and chlorogenic acid, reinforcing their potential to form stable bonds with the target proteins, crucial for effective drug action. Molecular dynamic simulation results further supported the stability of chlorogenic acid and quercetin during the simulation process, providing additional confidence in their potential as lead compounds for CAM treatment. The exploration of these phytochemicals provided the new avenues in the search for effective therapies to combat this severe fungal infection aimed at mitigating the impact of COVID-19 and its associated complications.

Data availability

All the data has been included in the manuscript.

References

Chakraborty, I. & Maity, P. COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 728, 138882 (2020).

Islam, M. R. et al. The impact of mucormycosis (black fungus) on SARS-CoV-2-infected patients: at a glance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(46), 69341–69366 (2022).

Singh, A. K., Singh, R., Joshi, S. R. & Misra, A. Mucormycosis in COVID-19: a systematic review of cases reported worldwide and in India. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome: Clin. Res. Reviews. 15(4), 102146 (2021).

Bhatt, K. et al. High mortality co-infections of COVID-19 patients: mucormycosis and other fungal infections. Discoveries 9(1), e126 (2021).

Malik, J. A. et al. The impact of COVID-19 on comorbidities: a review of recent updates for combating it. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29(5), 3586–3599 (2022).

Prakash, H., Skiada, A., Paul, R. A., Chakrabarti, A. & Rudramurthy, S. M. Connecting the Dots: interplay of pathogenic mechanisms between COVID-19 disease and mucormycosis. J. Fungi. 7(8), 616 (2021).

Jose, A. et al. Current Understanding in the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2-associated rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis: a comprehensive review. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 20(3), 373–380 (2021).

Malhotra, H. S. et al. COVID-19 associated mucormycosis: staging and management recommendations (Report of a multi-disciplinary expert committee). J. Oral Biology Craniofac. Res. 11(4), 569–580 (2021).

Özbek, L. et al. COVID-19–associated mucormycosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 958 cases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 29(6), 722–731 (2023).

Fitero, A., Negrut, N., John, H. T., Ferician, A. & Marian, P. Corona-associated mucormycosis: case series reports and review of the literature. J. Fungi. 10(5), 305 (2024).

Erami, M. et al. Case report: COVID-19-associated mucormycosis co-infection with lomentospora prolificans: the first case and review on multiple fungal co-infections during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Med. 10, 1078970 (2023).

Girona, J. et al. The circulating GRP78/BiP is a marker of metabolic diseases and atherosclerosis: bringing endoplasmic reticulum stress into the clinical scenario. J. Clin. Med. 8(11), 1793 (2019).

Soliman, S. S. et al. Mucoricin is a ricin-like toxin that is critical for the pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Nat. Microbiol. 6(3), 313–326 (2021).

Shin, J., Toyoda, S., Fukuhara, A. & Shimomura, I. GRP78, a novel host factor for SARS-CoV-2: the emerging roles in COVID-19 related to metabolic risk factors. Biomedicines 10(8), 1995 (2022).

Alqarihi, A. et al. GRP78 and integrins play different roles in host cell invasion during mucormycosis. MBio 11, e01087–e01020 (2020).

Barman, S., Ghosh, R. & Sengupta, S. & Mandal, N. C. longterm storage of post-packaged bread by controlling spoilage pathogens using Lactobacillus fermentum C14 isolated from homemade curd. PLoS ONE. 12(8), e0184020 (2017).

Schalchli, H. et al. Antifungal activity of volatile metabolites emitted by mycelial cultures of saprophytic fungi. Ecology 27(6), 503–513 (2011).

Anand, U., Jacobo-Herrera, N., Altemimi, A. & Lakhssassi, N. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites 9(11), 258 (2019).

Saleem, A. et al. HPLC, FTIR and GC-MS analyses of Thymus vulgaris phytochemicals executing in vitro and in vivo biological activities and effects on COX-1, COX-2 and gastric Cancer genes computationally. Molecules 27(23), 8512 (2022).

Pundir, S., Martin, M. J., O’Donovan, C. & U. Consortium. UniProt tools. Curr. Protocols Bioinform. 53(1), 1.29.1–1.29.15. (2016).

Naveed, M. et al. Side chain inset of neurogenerative amino acids to metalloproteins: a therapeutic signature for Huntingtin protein in Huntington’s disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 6831–6842 (2023).

Naveed, M., Tabassum, N., Shabbir, M. A. & Iftikhar, M. J. CRISPR-Cas9 Guided RNA Based Model for the Silencing of Spinal Bulbar Muscular Atrophy: A Functional Genetic Disorder (2023).

Naveed, M. et al. Designing mRNA-and peptide-based vaccine construct against emerging multidrug-resistant Citrobacter freundii: A computational-based subtractive proteomics approach. Medicina 58(10), 1356 (2022).

Waseem, M. et al. Molecular characterization of spa, hld, fmhA, and l ukD genes and computational modeling the multidrug resistance of Staphylococcus species through Callindra harrisii silver nanoparticles. ACS Omega. (2023).

Colovos, C. & Yeates, T. O. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 2(9), 1511–1519 (1993).

Naveed, M. et al. Halogens engineering-based design of agonists for boosting expression of frataxin protein in Friedreich’s ataxia. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 6972–6984 (2023).

Srivastava, A. In-silico study of some natural compounds used as antifungal agents against Candida albicans. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 10(3), 188–197 (2020).

Naveed, M. et al. Revolutionizing treatment for toxic shock syndrome with engineered super chromones to combat antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27(11) (2023).

Laskowski, R. A. & Swindells, M. B. LigPlot+: Multiple ligand–protein Interaction Diagrams for Drug Discovery (ACS Publications, 2011).

Shiri, F., Pirhadi, S. & Rahmani, A. Identification of new potential HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors by QSAR modeling and structure-based virtual screening. J. Recept. Signal Transduction. 38(1), 37–47 (2018).

Mahanthesh, M. T. et al. Swiss ADME prediction of phytochemicals present in Butea monosperma (Lam.) Taub. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 9(3), 1799–1809 (2020).

López-Blanco, J. R., Aliaga, J. I., Quintana-Ortí, E. S. & Chacón, P. iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(W1), W271–W276 (2014).

Otto, S. P. et al. The origins and potential future of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the evolving COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Biol. 31(14), R918–R929 (2021).

Chandley, P., Subba, P. & Rohatgi, S. COVID-19-associated mucormycosis: a matter of concern amid the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Vaccines 10(8), 1266 (2022).

Assiri, A. M., Elbanna, K., Abulreesh, H. H. & Ramadan, M. F. Bioactive compounds of cold-pressed thyme (Thymus vulgaris) oil with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. J. Oleo Sci. 65(8), 629–640 (2016).

Monika, P. & Chandraprabha, M. N. Risks of mucormycosis in the current Covid-19 pandemic: a clinical challenge in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49(6), 4977–4988 (2022).

Fathima, A. S. et al. Mucormycosis: A triple burden in patients with diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic. Health Sci. Rev. 1, 100005 (2021).

Galovičová, L. et al. Thymus vulgaris essential oil and its biological activity. Plants. 10(9), 1959 (2021).

Carlos, A. J. et al. The chaperone GRP78 is a host auxiliary factor for SARS-CoV-2 and GRP78 depleting antibody blocks viral entry and infection. J. Biol. Chem. 296 (2021).

Klann, K. et al. Growth factor receptor signaling Inhibition prevents SARS-CoV-2 replication. Mol. Cell. 80(1), 164–174 (2020). e4.

Gebremariam, T. et al. CotH3 mediates fungal invasion of host cells during mucormycosis. J. Clin. Investig. 124(1), 237–250 (2014).

Jin, Y. et al. Endothelial activation and dysfunction in COVID-19: from basic mechanisms to potential therapeutic approaches. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 5(1), 293 (2020).

Watkins, T. N. et al. Inhibition of EGFR signaling protects from mucormycosis. MBio 9(4), 01384–01318. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio (2018).

Ramírez, D. & Caballero, J. Is it reliable to use common molecular docking methods for comparing the binding affinities of enantiomer pairs for their protein target? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17(4), 525 (2016).

Sharma, S., Sharma, A. & Gupta, U. Molecular docking studies on the anti-fungal activity of (2021).

Shukla, A. K. & Kumar, A. Virtual screening of orally active lead compounds of Pearl millet and their structural activity against target protein of COVID-19. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 49(Suppl 1), S53–S70 (2023).

Jha, R. K., Shukla, A. K., Kumari, A. & Kumar, A. Virtual screening of potential orally active anti-bacterial compounds of finger millet. Vegetos. 1–12 (2024).

Shukla, A. K. & Kumar, A. Comparative study between antiviral drugs and natural compounds against Cryo-EM structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Spike. Vegetos 37(2), 596–605 (2024).

LipinskiC.A., LombardoF., DominyB.W. & FeeneyP.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 4–17 (2012).

Pokharkar, O., Lakshmanan, H., Zyryanov, G. & Tsurkan, M. In Silico evaluation of antifungal compounds from marine sponges against COVID-19-associated mucormycosis. Mar. Drugs. 20(3), 215 (2022).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R890), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are also thankful to the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Faisal University under project no. [KFU250986].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Muhammad Naveed and Ayesha Saleem; methodology, Nouman Ali; software, Zeerwah Rajpoot; validation, Khloud Ghazi Fakiha; formal analysis, Ayaz Ali Khan.; investigation, Rania Ali El Hadi Mohamed; resources, Tariq Aziz.; data curation, Fahad Al-Asmari.; writing—original draft preparation, Muniba Niaz.; writing—review and editing, Fakhria A. Al-Joufi; visualization, Maher S. Alwethaynani ; supervision, Muhammad Naveed and Tariq Aziz.; project administration, Tariq Aziz.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical Approval for this study was granted by Departmental Ethical Committee Department of Biotechnology University of Central Punjab Lahore Punjab. Collection of plants was made by proper guidelines and proper approval from the concerned authorities. The study complies with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naveed, M., Saleem, A., Aziz, T. et al. Exploring the therapeutic potential of Thymus vulgaris ethanol extract: a computational screening for antimicrobial compounds against COVID-19 induced mucormycosis. Sci Rep 15, 15906 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00937-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00937-z