Abstract

This study employed a trans-ethnic two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis to investigate the causal relationship between membranous nephropathy (MN) and peripheral artery disease (PAD). In European populations, MN exhibited a significant positive causal effect on PAD (discovery: OR = 1.040, P = 0.028; validation: OR = 1.028, P = 0.031), whereas no such association was observed in East Asians (P > 0.05). A two-step mediation analysis identified several proteins influenced by MN, including thrombomodulin (TM) (β = 0.031, P = 0.001), macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (MCSF1) (β = 0.239, P = 0.015), stem cell factor (SCF) (β = 0.028, P = 0.002), and tissue factor (TF) (β = 0.031, P = 0.001), while MN negatively affected interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (β=-0.049, P = 0.015) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (β=-0.027, P = 0.005). Multivariable MR analysis confirmed that only TM had an independent positive causal effect on PAD (β = 0.225, P < 0.001), and mediation analysis further validated TM as a significant mediator in the MN-to-PAD pathway (Z = 2.823, P = 0.048). Sensitivity analyses detected no significant pleiotropy or heterogeneity, supporting the robustness of our findings. This study highlights crucial ethnic differences in MN-associated PAD risk and underscores the importance of population-specific research. TM may serve as a potential therapeutic target for PAD prevention in MN patients, particularly those of European ancestry, providing novel insights into kidney-vascular disease mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid ageing of the global population and increased exposure to risk factors such as smoking and diabetes, peripheral artery disease (PAD) has become a significant public health challenge1, affecting over 230 million people worldwide2. The prevalence of PAD is estimated to be 4.3% in individuals aged ≥ 40 years, rising to 14.5% in those aged ≥ 70 years3. Multi-ethnic studies have revealed a striking disparity in PAD incidence, with Black individuals having a significantly higher prevalence than Whites, whereas Asians exhibit lower rates4. As the third leading cause of cardiovascular morbidity, PAD is driven primarily by atherosclerosis and thrombosis, leading to arterial stiffening, narrowing, and occlusion in the lower limbs1,5. This results in impaired blood flow, elevating the risk of amputation, stroke, myocardial infarction, reduced quality of life, and mortality6. Notably, PAD imposes a comparable or even greater risk of adverse cardiovascular events than coronary heart disease or stroke, underscoring its role as an indicator of systemic atherosclerotic burden7. Reflecting its growing clinical significance, the PAD National Action Plan has established strategic goals to enhance awareness, early detection, and treatment, with PAD designated as a top priority in the 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines of the American College of Cardiology. Consequently, a deeper understanding of PAD pathogenesis is essential for developing novel prevention and treatment strategies.

While PAD is well recognized as a major cardiovascular burden7, its relationship with chronic kidney disease (CKD), particularly membranous nephropathy (MN), warrants further investigation8. MN, a leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults, is a non-inflammatory autoimmune glomerular disease with an estimated global incidence of 8–10 cases per million9,10, though significantly higher rates (23.4%) have been reported in China11. It predominantly affects individuals aged 50–60 years across different ethnicities12. MN is characterized by the deposition of immune complexes, including immunoglobulins and antigens13, along the glomerular basement membrane, leading to progressive kidney damage12,14. The primary clinical hallmarks include proteinuria and edema, which result from glomerular dysfunction and endothelial impairment12,13. As the disease progresses, MN is associated with metabolic disturbances, including dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hypercoagulability, which are key risk factors for vascular diseases such as PAD15,16. Emerging evidence suggests shared pathophysiological mechanisms between MN and PAD, including endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and thrombosis17. However, observational studies attempting to elucidate this relationship have been limited by confounding factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia as well as the potential for reverse causation bias. To address these challenges, Mendelian randomization (MR) offers a powerful approach by leveraging genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) to infer causality between MN and PAD while minimizing confounding and bias18.

Beyond establishing causality, the identification of biomarkers mediating MN-induced PAD risk is of critical importance. Despite its high prevalence and poor prognosis, PAD is often diagnosed at advanced stages, highlighting the urgent need for reliable biomarkers for early risk stratification. Previous studies, including observational and MR analyses, have implicated various circulating proteins in PAD pathogenesis, including cardiovascular proteins19, inflammatory mediators20, and growth factors21 involved in endothelial function, immune response, and vascular repair. However, inconsistent findings across studies necessitate further investigation to determine whether specific circulating proteins mediate the MN-PAD relationship19.

This study aims to elucidate the causal relationship between MN and PAD using MR analysis across European and East Asian populations. Additionally, we seek to explore the potential mediating roles of circulating proteins in this association through a two-step mediation MR framework. By integrating discovery and validation cohorts from European ancestry along with an East Asian cohort, we ensure a comprehensive examination of the genetic predisposition linking MN to PAD. These findings are expected to provide novel insights into the mechanistic pathways underlying MN-associated PAD, facilitating the identification of biomarkers for early detection and therapeutic targets to mitigate cardiovascular risk in MN patients.

Materials and methods

Study design

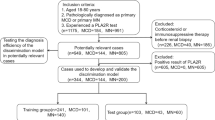

Study overview. A, The phenotypes included in the overall MR analysis. B, The causal effects of MN on PAD in European and East Asian ancestries were analyzed using UVMR. When the results were significant, reverse MR was performed to identify the causal association of PAD on MN. C, Two-step MR was conducted to screen 10 potential mediators involved in the MN-PAD axis. The mediation effects and proportions for validated mediators were quantified. MN, Membranous nephropathy; PAD, Peripheral artery disease; MR, Mendelian randomization; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization; MVMR, multivariable Mendelian randomization; MMP12, Matrix metalloproteinase-12; TM, Thrombomodulin; TF, Tissue factor; MCSF1, Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; CRP, C-reactive protein; CD4, T-cell surface glycoprotein CD4; BNGF, Beta-nerve growth factor; HGF, Hepatocyte growth factor; SCF, Stem cell factor. (Figure was partly created with Figdraw).

The phenotypes of exposure, outcome, and mediator included in the overall MR analysis are illustrated in Fig. 1A, while the workflow is depicted in Fig. 1B and C. Initially, two-sample univariable MR (UVMR) was used to assess forward causal relationship between MN and PAD in both discovery and validation cohort across European and East Asian populations. Upon obtaining significant results (yielding the total effect β), reverse MR was subsequently performed to determine the causal relationship of PAD on MN.

To further explore whether MN exert its effect on PAD through circulating proteins—such as cardiovascular proteins, inflammatory factors, and growth factors— two-sample UVMR was conducted to evaluate the indirect effect β1 of MN on each candidate protein. Concurrently, multivariable MR (MVMR) was employed to assess the indirect effect β2 of candidate proteins on PAD while adjusting for MN. The mediation effect and mediation proportion of identified mediators were calculated using the product of coefficients method and the delta method22,23, ensuring a causal estimation of mediation processes within the MN-PAD axis. The present research was conducted following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology using Mendelian Randomization (STROBE-MR) guidelines24 and the checklist was provided in Table S1.

Data sources

To minimize bias from sample overlap, we obtained exposure, outcome, and mediator datasets from distinct genome-wide association studies (GWAS). The details of data sources, including population ancestry, sample sizes, and associated references, are presented in Table 1. For MN exposure data, we selected summary GWAS datasets from both European (GWAS ID: ebi-a-GCST010005; sample size = 7,979) and East Asian (GWAS ID: ebi-a-GCST010004; sample size = 4,841) populations25, PAD outcome data were obtained from two European population-based datasets, one from the FinnGen database26 as the discovery cohort (GWAS ID: finn-b-I9_PAD; sample size = 7098) and another from UK Biobank (UKB)27 as the validation cohort (GWAS ID: ebi-a-GCST90018890; sample size = 483,078). For East Asian populations, PAD data (GWAS ID: bbj-a-144; sample size = 212,453) were sourced from Biobank Japan (BBJ)28. To identify potential mediators, we based our selection on observational studies and relevant literature reviews. We included ten circulating proteins that are likely involved in the MN-PAD disease axis. These candidate mediators primarily consist of proteins with cardiovascular (MMP12, TM, TF), inflammatory (CD4, CRP, MCSF1, IL-1β), and growth factor (BDNF, HGF, SCF) functions. The GWAS dataset features related to these phenotypes are provided in Table 1. We have also summarized the functional evidence for these phenotypes in Table S2.

We screened for mediators of the causal associations between MN and PAD according to the following criteria: [1]MN should be causally associated with the mediator; [2] the mediator should have a direct causal effect on PAD independently of MN; and [3] the total effect of MN on PAD and the mediating effect of the mediator should be in the same direction. To ensure consistency across findings, we replicated the mediation analyses for the associations of MN with PAD validation cohort for Europeans.

Instrumental variables (IVs) selection

In UVMR analyses, IVs related to MN were selected at the genome-wide significant level (P < 5 × 10–8), with linkage disequilibrium (LD) clumping (r2 < 0.001 within a 10,000 kb window) using the 1000 Genomes reference panel in order to satisfy the assumptions required for MR29,30. IVs selection adheres to the three core assumptions of MR analysis31: the relevance assumption (IVs are significantly associated with the exposure variable), the independence assumption (IVs are not related to confounding factors), and the exclusion restriction assumption (IVs affect the outcome variable only through the exposure variable). We also calculated the F-statistics using the formula \(\:F=\frac{N-K-1}{K}\times\:\frac{{R}^{2}}{1-{R}^{2}}\), where N represents the sample size, K is the number of IVs included, and R2 indicates the exposure variance explained by the chosen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)32. An F-statistic greater than 10 indicates substantial efficacy of the instrumental variables in mitigating potential biases33,34. In MVMR analyses, we maintained the same IV selection criteria previously established in our UVMR analysis.

MR analyses

In UVMR analysis, the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method serves as the primary analysis tool35,36. This method combines the Wald ratio estimates from each individual SNP within the set of IVs using random-effects meta-analysis to derive a unified causal estimate37. Additionally, we employed MR-Egger regression and weighted median methods as complementary analytical approaches to enhance the robustness of our findings38. The causal estimates were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binary outcomes (e.g., PAD) and as β coefficients with 95% CIs for continuous outcomes (e.g., candidate circulating proteins). The UVMR analytical framework encompassed several distinct processes: (1) assessment of the total causal effect (β) with MN as the exposure and PAD as the outcome; (2) first-stage mediation analysis examining the causal effect (β1) of MN (exposure) on candidate mediators (intermediate outcomes); and (3) reverse MR analysis to evaluate potential bidirectional relationships. It is worth noting that in the second-stage analysis (evaluating the causal effect of mediators on PAD, β2), we fully considered the potential co-existence and interactions among peripheral circulating proteins. To reduce potential bias from these interactions, we employed multivariable MR (MVMR) analysis methods and only included mediators that showed significant causal relationships with MN in the first-stage analysis as intermediate exposure variables39,40. This strategy not only improved the accuracy of causal inference but also enabled us to more precisely identify the biomarkers that truly mediate the relationship between MN and PAD.

Sensitivity analysis

To ensure robust and reliable results in the UVMR analysis, sensitivity analyses were performed. Heterogeneity among IVs was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic with both MR-Egger and IVW methods. Potential pleiotropy of the selected SNPs was evaluated through MR-Egger intercept tests and MR-PRESSO (Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier) analysis. Statistical significance was determined based on the P-values calculated from each method, with P > 0.05 indicating absence of significant heterogeneity or pleiotropy. These methodological approaches provided thorough evaluation of the causal relationships, ensuring that conclusions were based on reliable and unbiased estimates derived from MR principles.

Mediation analyses

As previously described, we employed a two-step MR analysis approach to evaluate mediation effects. In the first step, we conducted UVMR analysis to obtain the first-stage effect estimate (β₁); in the second step, we applied multivariable MR analysis to derive the second-stage effect estimate (β₂). The calculation of mediation effects was based on the product method, multiplying the first-stage causal effect (β₁, MN on mediator) by the second-stage causal effect (β₂, mediator on PAD). This product (β₁×β₂) represents the magnitude of the indirect effect through a specific mediator. To assess the significance of the mediation effects, we employed bootstrap methods for inference, generating confidence intervals for the mediation effect estimates. Additionally, we calculated the proportion mediated, defined as the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect ([β₁×β₂]/β), to quantify the proportion of the causal association between MN and PAD explained by specific mediators. This mediation effect analysis approach not only helped us identify important mediating proteins but also enabled us to quantify their relative contributions to disease progression, thereby providing empirical support for potential therapeutic targets.

All statistical tests conducted between two samples utilized the “TwoSampleMR” (version 0.5.11) and “MR-PRESSO” package in the R software (version 4.3.2). The MVMR analysis was performed using the “MVMR” package (version 0.4). To address multiple comparisons across the candidate mediators, we corrected the P-values derived from the IVW approach using the Benjamini-Hochberg method, also known as the false discovery rate (FDR) method. IVW estimates with P < 0.05, FDR-adjusted P-values < 0.05, and supported by at least one sensitivity analysis, were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Bidirectional causal relationships between MN and PAD in different ethnic ancestry

In the forward UVMR analysis of the PAD discovery cohort in Europeans, 4 SNPs (rs1634791, rs6759924, rs7246292, rs9271541) were identified as significant instrumental variables (IVs) related to MN. Different analysis directions yielded different numbers of IVs. Out of these, 3 IVs (rs6759924, rs7246292, rs9271541) were selected to proxy MN with a mean F statistic of 244. Genetically determined MN was causally associated with an increased risk of PAD (IVW OR: 1.040; 95%CI: 1.00–1.077, IVW P = 0.028), supported by the results from weighted median method (Fig. 2). Result was replicated using 4 IVs related to MN ((rs1634791, rs6759924, rs7246292, rs9271541; Table S3) from validation cohort (IVW OR: 1.028, 95%CI: 1.003–1.081, IVW P = 0.031) (Fig. 2). However, when we used 7 IVs (rs230540, rs28383314, rs6707458, rs7746807, rs9265201, rs9267898, rs9405192; Table S3) related to MN from the East Asian population and assessed the relationship between MN and PAD, the result showed no significant causal effect (Fig. 2, IVW P > 0.05).

For the reverse UVMR analysis, which was conducted using PAD as the exposure and MN as the outcome. Three IVs related to PAD were found in both the discovery set and validation set (Table S3). We found no statistically significant causal effect of PAD on MN in either the discovery cohort (IVW P = 0.085) or the validation cohort (IVW P = 0.340) (Table S4).

Sensitivity analysis for the MR analysis between MN and PAD

For the forward MR analysis, there was no significant heterogeneity (discovery set: Q = 0.088, P = 0.956; validation set: Q = 2.304, P = 0.512) or pleiotropy (discovery set: MR-Egger Intercept=−0.007, P = 0.839; validation set: MR-Egger Intercept = 0.007, P = 0.785) in either the discovery set or validation set (Table S5). However, in the reverse analysis, significant heterogeneity (discovery set: Q = 111.997, P < 0.001; validation set: Q = 167.833, P < 0.001) was found in both the discovery set and validation set, but no pleiotropy (discovery set: MR-Egger Intercept=−0.597, P = 0.894; validation set: MR-Egger Intercept = 0.079, P = 0.939) was observed (Table S5). In the analysis of MN to PAD in East Asian populations, we did not find any significant heterogeneity (Q = 8.717, P = 0.19) or pleiotropy (MR-Egger Intercept = 0.037, P = 0.241) (Table S5). The single SNP effect estimates, leave-one-out analysis, funnel plot, and scatter plot did not show any significant abnormal SNPs both in discovery set (Fig. S1) and validation set (Fig. S2).

Forest plot of univariable MR causal associations of MN on 10 candidate mediators. Different methods were used to obtain beta values and 95% confidence intervals. MMP12, Matrix metalloproteinase-12; TM, Thrombomodulin; TF, Tissue factor; MCSF1, Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; CRP, C-reactive protein; CD4, T-cell surface glycoprotein CD4; BNGF, Beta-nerve growth factor; HGF, Hepatocyte growth factor; SCF, Stem cell factor; β effect size for the effect allele; FDR-P P value of False Discovery Rate.

Causal relationship of MN on candidate mediators

For the two step MR conducted to screen valid mediators, the first step involved UVMR analyses of MN (IVs related to MN are provided in Table S3) on each of the 10 candidate proteins, genetically determined MN was causally associated with higher levels of thrombomodulin (TM), tissue factor (TF), macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (MCSF1), and stem cell factor (SCF), as well as lower levels of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), after FDR adjustment for multiple comparisons (Fig. 3). Detailed result was provided in Table S6 in Supplementary Materials. In this step, Matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP12), C-reactive protein (CRP), T-cell surface glycoprotein CD4 (CD4), and Beta-nerve growth factor (BNGF) were excluded due to no significant causal relationship with MN (Fig. 3). For the sensitivity analyses conducted in directions showing significant causal effects (detailed in Table S7), we found no significant pleiotropy (Q test P > 0.05) or heterogeneity (MR-Egger Intercept P > 0.05) except in the analysis examining the effect of MN on MMP12.

Causal relationship of mediators on PAD

In the second step, we included the 6 mediators with significant causal effects from the first step analysis, including TM, TF, MCSF1,SCF, IL1β, and HGF. With adjustment for MN, MVMR-IVW results (Table 2) showed that TM exhibited an independent positive causal effect on PAD in both the discovery (β = 0.225, P < 0.001) and validation sets (β = 0.365, P < 0.001). Furthermore, MCSF1, IL-1β, and HGF also showed relatively independent causal effects on PAD, with MCSF1 (β=−0.047, P = 0.033) demonstrating a positive causal effect, while IL-1β (β = 0.166, P < 0.001) and HGF (β = 0.22, P = 0.02) showed negative causal effects (Table 2).

Selection process for significant mediators in the causal relationship of MN with PAD. MN, Membranous nephropathy; PAD, Peripheral artery diseaseMMP12, Matrix metalloproteinase-12; TM, Thrombomodulin; TF, Tissue factor; MCSF1, Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; CRP, C-reactive protein; CD4, T-cell surface glycoprotein CD4; BNGF, Beta-nerve growth factor; HGF, Hepatocyte growth factor; SCF, Stem cell factor. The full MR estimates are shown in Table S6 and Table 2.

Mediating effects of circulating proteins on the MN-PAD disease axis

Three criteria were applied to screen for mediators in the causal associations of MN with PAD: [1] MN is causally associated with the mediator; [2] the mediator has a direct causal effect on PAD independently of MN; and [3] the total effect of MN on PAD and the mediating effect are in the same direction. Only one mediator (TM) qualified by meeting all criteria (Fig. 4) and was included in the mediation analyses to quantify its effect and proportion in the causal disease axis from MN to PAD. The product of coefficients method was employed, multiplying indirect effect β1 (from UVMR: MN to candidate protein) by indirect effect β2 (from MVMR: candidate protein to PAD adjusted for MN). TM was confirmed as the sole qualified mediator with a mediation proportion of 17.79% (95% CI: 17.32%, 18.25%) in the discovery cohort, and 40.32% (95% CI: 39.53%, 41.11%) in the PAD validation cohort (Table 3).

Discussion

Using the two-sample UVMR method within our MR framework, genetically predisposed causal relationships between MN and PAD risk were identified in both discovery and validation cohorts of European ancestry. However, this association was not observed in the East Asian ancestry cohort. Reverse MR analysis from PAD to MN in Europeans revealed no significant causal association. Importantly, two-step mediation analysis of the 10 candidate proteins elucidated that circulating thrombomodulin levels partly mediate the progression from MN to PAD. The causal relationship between MN and PAD risk demonstrates ethnic specificity, being present in European populations but absent in East Asian cohorts. This ethnic heterogeneity suggests potential genetic or environmental modifiers that warrant further investigation. The unidirectional nature of the relationship, confirmed by the lack of reverse causality from PAD to MN, strengthens the evidence for MN as a potential upstream risk factor for PAD development. The identification of thrombomodulin as a mediator provides valuable insight into the biological mechanisms connecting MN to PAD. This mediating role accounts for 17.79% of the effect in the discovery cohort and 40.32% in the validation cohort, highlighting thrombomodulin as a potential therapeutic target to mitigate PAD risk in patients with MN. These findings contribute to understanding the pathophysiological connections between kidney dysfunction and peripheral vascular disease.

In previous clinical observational studies, there is strong evidence that CKD increases the risk of various CVD outcomes16,41,42,43. However, these studies focus primarily on coronary heart disease and heart failure and are subject to many confounding factors. For most CKD patients who develop CVDs, their CKD indicates end-stage kidney disease (ESKD, CKD stage 5)41,43, which typically occurs several years. In contrast, cardiovascular complications in patients with primary MN may arise much earlier, often within the first 6 months following diagnosis11,44. Hence, it is essential to clarify the isolated impact of primary MN on PAD. The impact of MN on cardiovascular disease is mainly focused on thromboembolic events, including both venous thromboembolic events (VTEs)45 and arterial thromboembolic events (ATEs)46. In recent large retrospective cohort studies including Danish, Chinese and American MN patients with newly diagnosed nephrotic syndrome, the 0.5- to 2-year incidence of arterial thromboembolism was 4.2–6.3%. Over a period of 5 to 10 years, the risk of arterial thromboembolism increased to 8.0–14.0%47. However, ATEs in the above retrospective studies were predominantly coronary ischemic infarction and thrombotic ischemic stroke, as PAD remains under-recognized and under-diagnosed to date. Clinical prospective randomized controlled trials exploring the link between MN and PAD is even more limited due to the high costs and confounding biases. To overcome these obstacles, we employed an MR study to establish a causal relationship between the two complicated entities, thus providing robust evidence.

The pathological mechanism by which MN leads to PAD has not yet been universally established. PAD is a chronic inflammatory disease involving various immune cells48, and there is growing evidence that membranous nephropathy is also characterized by immune dysregulation and inflammatory reactions49,50. This suggests potential intersections between the two conditions, including endothelial dysfunction, systemic inflammation, and prothrombotic states. Our study focuses on cardiovascular proteins (MMP12, TM, TF), inflammatory factors (MCSF1, IL-1β, CRP, CD4), and growth factors (BNGF, HGF, SCF), which may mediate the relationship between MN and PAD, and finally identified that TM plays a mediating role in the process of MN causing PAD. Thrombomodulin is a single-chain transmembrane glycoprotein, encoded by the gene THBD on the chromosome 20p12, with a molecular weight of 75 kDa and containing five molecular structural domains, which is mainly expressed in the vascular endothelium to exert anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory effects by trapping thrombin and activating the protein C system. When the endothelium is damaged in an inflammatory or immune environment, its transmembrane components are released into the circulation and lose their physiological functions51. Therefore, circulating soluble thrombomodulin levels can be used as one of the biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction52. Endothelial dysfunction, in turn, may contribute to the initiation of coagulation and atherosclerosis. Moreover, sTM is metabolized by the kidneys and may be elevated in the presence of renal impairment53.

A 1990 observational study discovered that patients with early diabetic nephropathy had elevated levels of TM in comparison to healthy subjects54. Subsequent basic and clinical studies have also found that circulating TM levels are increased in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, lupus nephropathy, and acute/chronic kidney disease53,55. An MR study suggested a positive causality between MN and TM56. Furthermore, atherosclerosis is linked to elevated soluble TM levels, with patients suffering from PAD or multi-vascular disease (Concurrent carotid and iliac or femoral arteries disease) showing even higher levels than patients with limited atherosclerotic disease57. Several scholars further explored the mechanism and found that elevated levels of TM bind to soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2 (TNFR2. TNFR2 activation induced by TNF-α plays a central role in the initiation of the coagulation pathway, leading to thrombosis of small arteries58,59. Additionally, TM mRNA expression in monocytes has been positively correlated with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, which are known to play a key role in the development of atherosclerosis60. Therefore, these findings indicate that TM may act as a mediating factor through which MN leads to PAD. Numerous studies have highlighted the potential of TM levels as a circulating biomarker of endothelial damage and disease progression in atherosclerosis and thrombotic disorders, for monitoring disease and evaluating therapeutic efficacy53.

In summary of the evidence above, TM as a key mediator in MN-induced PAD operates through three main mechanisms: First, renal function impairment caused by MN affects TM metabolic clearance, elevating its levels in circulation; second, MN-associated immune dysregulation and inflammatory responses directly damage vascular endothelium, prompting endothelial cells to release TM into the bloodstream; finally, elevated circulating TM promotes coagulation pathway activation and atherosclerosis development through binding to TNFR2 and influencing LDL metabolism in monocytes, ultimately leading to PAD. This mechanistic chain suggests that plasma TM level testing could become an important clinical marker for assessing thrombotic risk in MN patients. Given our research confirming that TM mediates 17.79–40.32% of disease progression from MN to PAD, monitoring TM levels may not only help identify high-risk patients early but could also be used to evaluate the efficacy of anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory therapies. This provides new insights for individualized thrombosis prevention strategies and clinical decision-making in MN patients, with significant translational clinical value.

Benefiting from ethnicity-stratified summary-level data for MN and PAD, we conducted an ancestry-specific two-sample UVMR analysis. Unfortunately, the causal relationship between MN and PAD was not revealed among East Asian ancestry. Potential causes may be as follows: First, there are significant differences in the genetic backgrounds between different populations61. The frequency of genetic variants may vary markedly between European and East Asian populations, potentially influencing the association between MN and PAD. Second, environmental factors such as diet, smoking, and pollution may have different impacts on different populations62. These factors might modulate the relationship between MN and PAD. For example, the East Asian cohort of PAD primarily includes individuals from Japan, where the diet is predominantly whole-food-based, rich in fish, seafood, and plant-based foods, with very limited intake of animal protein, added sugars, and fats. This dietary pattern significantly reduces the incidence of cardiovascular diseases, including PAD63.

Our study demonstrates several strengths. Firstly, employing bidirectional MR, we investigated the causal association between MN and PAD in European populations, confirming these findings in a separate validation cohort from a large-scale GWAS study. This approach mitigated biases from confounding factors and reverse causality, thereby establishing credible causal inferences. Secondly, the outcomes were supported by a comprehensive set of sensitivity analyses, ensuring their robustness. Thirdly, our efforts assessed the causal effects of MN on PAD risk across different ancestries. Finally, we delved into potential causal pathways involving common circulating proteins from MN to PAD through MVMR and mediation analyses. These insights offer valuable guidance for developing targeted interventions and preventive strategies.

Nevertheless, this study also has its limitations. First, genetic variation among different races may lead to heterogeneity in causal estimates. Although PAD prevalence is higher among Black individuals4 and in low- and middle-income countries7,64, our study primarily involves participants of European and Asian descent, limiting the generalizability to other populations. Second, despite strict selection criteria for genetic IVs and assessments of heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy that confirmed the absence of horizontal pleiotropy in the instrumental variables included in the analysis, we still cannot rule out that potential pleiotropy may introduce bias to our MR analysis results. In some analysis directions, horizontal pleiotropy was present, and although our overall MR analysis results did not change significantly after adjusting for certain specific instrumental variables, persistent heterogeneity suggests the complexity of current instrumental variables. Therefore, even though many circulating proteins of interest have not yet been found to have a mediating effect, further research in this area remains necessary. Furthermore, the mediation analysis focused on a selected number of candidate proteins, and there might be other mediators involved that were not considered in this study. Finally, due to GWAS data limitations, we could not stratify MN and PAD by stages, gender, or age, nor explore trend relationships between MN and PAD risk and prognosis. Future studies with more comprehensive MN and PAD data and in-depth analyses are warranted to gain further insights into their complex associations.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates a causal relationship between membranous nephropathy and peripheral artery disease in European populations, with thrombomodulin identified as a key mediator accounting for 17.79–40.32% of this effect. This relationship was not observed in East Asian populations, highlighting the importance of genetic and environmental factors. Monitoring thrombomodulin levels may serve as a valuable biomarker for identifying MN patients at high risk of PAD. These findings provide potential targets for intervention strategies and suggest that thrombomodulin assessment could improve risk stratification and guide personalized preventive measures in clinical practice.

Data availability

All the GWAS data used in this study are publicly available. We accessed GWAS statistics for the traits from the IEU Open GWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). The data generated in this study is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- MN:

-

Membranous nephropathy

- PAD:

-

Peripheral artery disease

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- IVW:

-

Inverse variance weighted

- IVs:

-

Instrumental variables

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- MR:

-

Mendelian: randomization

- MVMR:

-

Multivariable MR

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- MMP12:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase-12

- TM:

-

Thrombomodulin

- TF:

-

Tissue factor

- MCSF1:

-

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1

- IL-1β:

-

Interleukin-1beta

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CD4:

-

T-cell surface glycoprotein CD4

- BNGF:

-

Beta-nerve growth factor

- HGF:

-

Hepatocyte growth factor

- SCF:

-

Stem cell factor

References

Golledge, J. Update on the pathophysiology and medical treatment of peripheral artery disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 456–474. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00663-9 (2022).

Criqui, M. H. et al. Lower extremity peripheral artery disease: contemporary epidemiology, management gaps, and future directions: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 144, e171–e191. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001005 (2021).

Gao, X. et al. Similarities and differences in peripheral artery disease between China and Western countries. J Vasc Surg 74, 1417–1424 e1411 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.03.030

Hackler, E. L. 3, Hamburg, N. M., White Solaru, K. T. & rd, & Racial and ethnic disparities in peripheral artery disease. Circ. Res. 128, 1913–1926. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318243 (2021).

Fowkes, F. G. et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 382, 1329–1340. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0 (2013).

Criqui, M. H. & Aboyans, V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ. Res. 116, 1509–1526. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849 (2015).

Aday, A. W. & Matsushita, K. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease and polyvascular disease. Circ. Res. 128, 1818–1832. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318535 (2021).

Visseren, F. L. J. et al. ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 42, 3227–3337 (2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484

Ronco, P. & Debiec, H. Molecular pathogenesis of membranous nephropathy. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 15, 287–313. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043811 (2020).

Keri, K. C., Blumenthal, S., Kulkarni, V., Beck, L. & Chongkrairatanakul, T. Primary membranous nephropathy: comprehensive review and historical perspective. Postgrad. Med. J. 95, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-135729 (2019).

Wang, M., Yang, J., Fang, X., Lin, W. & Yang, Y. Membranous nephropathy: pathogenesis and treatments. MedComm (2020). 5, e614. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.614 (2024).

Ronco, P. et al. Membranous nephropathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00303-z (2021).

Hoxha, E., Reinhard, L. & Stahl, R. A. K. Membranous nephropathy: new pathogenic mechanisms and their clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 466–478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00564-1 (2022).

Beck, L. H. Jr. & Salant, D. J. Membranous nephropathy: from models to man. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 2307–2314. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI72270 (2014).

Mehta, A. et al. Premature atherosclerotic peripheral artery disease: an underrecognized and undertreated disorder with a rising global prevalence. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 31, 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2020.06.005 (2021).

Matsushita, K. et al. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 696–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00616-6 (2022).

Dusek, K. [Intensive care units in psychiatry (author’s transl)]. Cesk. Psychiatr. 72, 24–27 (1976).

Levin, M. G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization as a tool for cardiovascular research: A review. JAMA Cardiol. 9, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2023.4115 (2024).

Yuan, S. et al. Circulating proteins and peripheral artery disease risk: observational and Mendelian randomization analyses. Eur. Heart J. Open. 3, oead056. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjopen/oead056 (2023).

Shen, J., Zhao, M., Zhang, C. & Sun, X. IL-1beta in atherosclerotic vascular calcification: from bench to bedside. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 17, 4353–4364. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.66537 (2021).

Sharma, K. et al. The emerging role of Pericyte-Derived extracellular vesicles in vascular and neurological health. Cells 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11193108 (2022).

Kong, L. et al. Opposite causal effects of birthweight on myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation and the distinct mediating pathways: a Mendelian randomization study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02062-5 (2023).

Ye, C. J. et al. Mendelian randomization evidence for the causal effects of socio-economic inequality on human longevity among Europeans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1357–1370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01646-1 (2023).

Skrivankova, V. W. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomisation (STROBE-MR): explanation and elaboration. BMJ 375, n2233. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2233 (2021).

Xie, J. et al. The genetic architecture of membranous nephropathy and its potential to improve non-invasive diagnosis. Nat. Commun. 11, 1600. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15383-w (2020).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8 (2023).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z (2018).

Zhou, W. et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 50, 1335–1341. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0184-y (2018).

Hartwig, F. P., Davies, N. M., Hemani, G. & Davey Smith, G. Two-sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1717–1726. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx028 (2016).

Auton, A. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393 (2015).

Glymour, M. M., Tchetgen, T., Robins, J. M. & E. J. & Credible Mendelian randomization studies: approaches for evaluating the instrumental variable assumptions. Am. J. Epidemiol. 175, 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr323 (2012).

Xie, R. et al. Mitochondrial proteins as therapeutic targets in diabetic ketoacidosis: evidence from Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1448505 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Causal relationship between meat intake and biological aging: evidence from Mendelian randomization analysis. Nutrients 16, 2433 (2024).

Pierce, B. L., Ahsan, H. & Vanderweele, T. J. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 740–752. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq151 (2011).

Liu, S. et al. Lipid profiles, telomere length, and the risk of malignant tumors: A Mendelian randomization and mediation analysis. Biomedicines 13, 13 (2025).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 37, 658–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21758 (2013).

Lu, L., Wan, B. & Sun, M. Mendelian randomization identifies age at menarche as an independent causal effect factor for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 25, 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.14869 (2023).

Yan, X. et al. New insights from bidirectional Mendelian randomization: causal relationships between telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number in aging biomarkers. Aging 16, 7387–7404. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.205765 (2024).

Richmond, R. C. et al. Assessing causality in the association between child adiposity and physical activity levels: a Mendelian randomization analysis. PLoS Med. 11, e1001618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001618 (2014).

Larsson, S. C., Butterworth, A. S. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: principles and applications. Eur. Heart J. 44, 4913–4924. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad736 (2023).

Jankowski, J., Floege, J., Fliser, D., Bohm, M. & Marx, N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation 143, 1157–1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050686 (2021).

Carney, E. F. The impact of chronic kidney disease on global health. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16, 251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-0268-7 (2020).

Zoccali, C. et al. Cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease: a review from the European renal and cardiovascular medicine working group of the European renal association. Cardiovasc. Res. 119, 2017–2032. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvad083 (2023).

Zou, H., Li, Y. & Xu, G. Management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in patients with primary membranous nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 20, 442. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1637-y (2019).

Barbour, S. J. et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 81, 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.312 (2012).

Lee, T. et al. Patients with primary membranous nephropathy are at high risk of cardiovascular events. Kidney Int. 89, 1111–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2015.12.041 (2016).

Vestergaard, S. V. et al. Risk of Arterial Thromboembolism, Venous Thromboembolism, and Bleeding in Patients with Nephrotic Syndrome: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Med 135, 615–625 e619 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.11.018

Schrottmaier, W. C., Mussbacher, M., Salzmann, M. & Assinger, A. Platelet-leukocyte interplay during vascular disease. Atherosclerosis 307, 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.04.018 (2020).

Cremoni, M. et al. Th17-Immune response in patients with membranous nephropathy is associated with thrombosis and relapses. Front. Immunol. 11, 574997. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.574997 (2020).

Lerner, G. B., Virmani, S., Henderson, J. M., Francis, J. M. & Beck, L. H. Jr. A conceptual framework linking immunology, pathology, and clinical features in primary membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 100, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.03.028 (2021).

Watanabe-Kusunoki, K., Nakazawa, D., Ishizu, A. & Atsumi, T. Thrombomodulin as a physiological modulator of intravascular injury. Front. Immunol. 11, 575890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.575890 (2020).

Sega, V. D. Circulating biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in predicting clinical outcomes in diabetic patients with critical limb ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810641 (2022).

Boron, M., Hauzer-Martin, T., Keil, J. & Sun, X. L. Circulating thrombomodulin: release mechanisms, measurements, and levels in diseases and medical procedures. TH. Open. 6, e194–e212. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1801-2055 (2022).

Iwashima, Y. et al. Elevation of plasma thrombomodulin level in diabetic patients with early diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 39, 983–988. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.39.8.983 (1990).

Ye, Q. et al. A spectrum of novel anti-vascular endothelial cells autoantibodies in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome patients. Clin. Immunol. 249, 109273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2023.109273 (2023).

Ma, Q. & Xu, G. Causal association between cardiovascular proteins and membranous nephropathy: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 56, 2705–2714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-024-04004-w (2024).

Gerdes, V. E. et al. Soluble thrombomodulin in patients with established atherosclerosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2, 200–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.0562f.x (2004).

Yoshii, Y. et al. Expression of thrombomodulin in human aortic smooth muscle cells with special reference to atherosclerotic lesion types and age differences. Med. Electron. Microsc. 36, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00795-003-0212-5 (2003).

Miceli, G., Basso, M. G., Rizzo, G., Pintus, C. & Tuttolomondo, A. The role of the coagulation system in peripheral arterial disease: interactions with the arterial wall and its vascular microenvironment and implications for rational therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314914 (2022).

Oida, K. et al. Effect of oxidized low density lipoprotein on thrombomodulin expression by THP-1 cells. Thromb. Haemost. 78, 1228–1233 (1997).

Chen, M. H. et al. Trans-ethnic and Ancestry-Specific Blood-Cell Genetics in 746,667 Individuals from 5 Global Populations. Cell 182, 1198–1213 e1114 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.045

Munzel, T. et al. Environmental risk factors and cardiovascular diseases: a comprehensive expert review. Cardiovasc. Res. 118, 2880–2902. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvab316 (2022).

Dominguez, L. J. et al. Healthy aging and dietary patterns. Nutrients 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14040889 (2022).

Song, P. et al. Global, regional, and National prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 7, e1020–e1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30255-4 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge the participants and investigators of all the GWAS study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81971624, 82271999) and Cross-Innovation Talent Project of People’s Hospital of Wuhan University (JCRCYR-2022-011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Juhong Pan and Xingyue Huang contributed to the conception, designing of the study and drafting of the manuscript. Yueying Chen, Nan Jiang and Yuxin Guo contributed to statistical analysis. Shiyuan Zhou and Yao Zhang contributed to collecting data from the public database. Bo Hu contributed to revising the manuscript. Qing Deng and Qing Zhou obtained funding and is the guarantor of this work and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.All authors contributed to the acquisition or interpretation of data, proof reading of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent statement and ethics approval statement

The current study utilized published and publicly available summary statistics from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which were obtained from reputable consortia or research projects. Ethical approval and informed consent details are available in the respective GWAS publications referenced in this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, J., Huang, X., Chen, Y. et al. Trans-ethnic Mendelian randomization analysis of membranous nephropathy and peripheral artery disease with mediating effects of thrombomodulin. Sci Rep 15, 17800 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02626-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02626-3