Abstract

B-cell type acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) is the most common type of childhood malignancy. Although the survival rate nowadays exceeds 90%, central nervous system (CNS) involvement is associated with a poor outcome. Experimental models are needed to study the interaction between leukemia cells and the brain microenvironment to unravel new targets for drug intervention. We developed a novel three-dimensional (3D) ex vivo model utilizing murine organotypic cortical brain slices microinjected with human B-ALL cells, serving as a platform for investigating the influence of Activin A, a pro-leukemic factor, on leukemia invasion into the CNS. After injection, B-ALL cells exponentially increased in the cortical slices, promoting tissue mortality and an anti-inflammatory microenvironment phenotype, as demonstrated by morphological and gene expression alterations in microglia and astrocytes. Of note, Activin A pretreatment increased leukemia proliferation and exacerbated the effects on the microenvironment. Overall, our model presents an ideal platform for investigating the cross-talk between tumors and the brain microenvironment and the influence of disease-modifying factors. Moreover, it could facilitate drug screening across a spectrum of CNS cancers, meanwhile reducing animal usage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer, with B-cell type ALL (B-ALL) representing about 80% of cases. Even though the overall survival rate exceeds 90%, B-ALL patients refractory to chemotherapy or relapsing after an initial phase of remission have the most severe prognosis and are today the real clinical challenge1. In this context, the central nervous system (CNS) is frequently affected both at disease diagnosis and relapse, representing an adverse prognostic factor2,3. Therefore, CNS prophylaxis is considered an essential component of current B-ALL protocols. It includes intrathecal chemotherapy and high dose systemic chemotherapy with good penetration into the CNS, both associated with neurotoxicity4,5,6,7,8. Despite prophylaxis, the CNS is involved in more than 30% of all relapses, either as an isolated site or in combination with bone marrow involvement9. Indeed, the identification of new highly targeted therapeutic approaches would be crucial to improve CNS disease management and reduce long-term toxicity in the B-ALL pediatric population, whose expectancy of normal life has currently considerably increased5. B-ALL is mainly a meningeal disease, but, upon leukemia progression, leukemic cells can penetrate by different routes into the brain parenchyma5. Similarly, mouse models have recently shown that B-ALL cells can infiltrate the brain subventricular zone and influence the surrounding microenvironment, impairing neurogenesis10. So far, little is known about the interaction between B-ALL blasts and the cerebral microenvironment and the molecular pathways involved in their survival within the CNS niche. Although the animal models are thought to represent the most reliable method to investigate such a complex cross-talk, a simplified preclinical model would help in shedding light on CNS leukemia-driven pathology and answering punctual questions. Nowadays, the organotypic brain slices are an attractive and under-utilized platform for preclinical translational research, representing a 3D cerebral tissue that maintains the intricate interactions between different cell types found in the brain, providing a representative model of the in vivo environment. These features allow for a better representation of physiological responses to stimuli, injury, pathological conditions, experimental manipulations or treatments compared to simplified 2D cultures. They have been used in different context such as Alzheimer’s disease11, proteinopaties12,13 or acute brain injury14,15,16,17. Their use can help to resemble the tumor microenvironment more closely in a controlled setting, allowing to study survival pathways, the cross-talk between tumor cells and cellular components of the brain microenvironment, and to perform functional investigations of drug responses18.

In this study we took advantage of organotypic cortical brain slices to develop a novel in vitro model of CNS leukemia. At this purpose, brain slices were microinjected with the B-ALL cell line NALM6 and longitudinally analyzed to assess malignant cells induced brain microenvironmental changes. As a proof-of-principle, we used this versatile platform to investigate the potential impact of the pro-leukemic cytokine Activin A on the progression of CNS leukemia. Activin A is a TGFβ family member, overexpressed in the bone marrow plasma of B-ALL patients, able to confer migratory and invasive advantage to B-ALL cells19. In a mouse xenograft model of the disease, Activin A pre-treatment of B-ALL cells was demonstrated to increase leukemic engraftment in the bone marrow and in extramedullary organs, such as the meninges and the brain19. In this regard, BMP4, another member of the TGFβ family, was recently identified as a negative prognostic factor in a large cohort of pediatric patients and associated with rapid disease progression and CNS involvement in a Nod Scid Gamma (NSG) mouse xenograft model20.

Overall, we demonstrated that our 3D organotypic brain slice model could represent an ideal tool for studying the interaction of malignant cells with the complex CNS microenvironment. Further studies involving additional tumor cell lines will be required to confirm its broader applicability to other leukemia subtypes and to brain cancers. This platform may ultimately contribute to streamlining the screening of disease-modifying factors and therapeutic agents, while supporting efforts to reduce animal use in preclinical research.

Results

The NALM6 B-ALL cells survive and proliferate in mouse cortical slices, with higher rate after activin A pretreatment

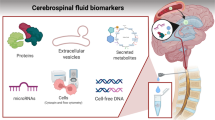

To set up an ex vivo model suitable for studying the interaction between leukemic cells and the complex cerebral microenvironment, the fluorescent (iRFP670 positive) NALM6 B-ALL cell line was microinjected in cortical slices. Leukemic cells were pretreated or not with Activin A to investigate whether this cytokine could affect NALM6 cell survival and invasiveness, as well as their ability to crosstalk with different cell subtypes of the surrounding cerebral niche. The interactions of NALM6 with brain tissue were longitudinally monitored as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Experimental design of the ex vivo model of brain leukemia. NALM6-iRFP670 fluorescent cells, pretreated or not with Activin A, were microinjected in cortical slices after 7d of recovery from cut. NALM6-iRFP670 cells were longitudinally tracked at microscope or by flow cytometry to evaluate cell viability and proliferation. Brain tissue mortality was evaluated by PI incorporation assay. Microglia activation and morphology were evaluated using CX3CR1+/GFP mice.

We firstly assessed NALM6 ability to survive and proliferate in the brain tissue. The quantification of the area occupied by NALM6-iRFP670 cells in the cortical slice, as index of blast invasiveness, showed a gradual increase up to 7 days, with no differences in non-stimulated cells (NALM6 NS) and Activin A-pretreated cells (NALM6 Activin A) (Fig. 2A,B), suggesting that in both conditions, cells are equally able to move from the injection site and invade the brain parenchyma. In addition, we performed an integrated density analysis to evaluate the intensity of the fluorescence signal, which, being proportional to the number of cells, represents an index of cell proliferation. Integrated density signal gradually increased up to 7 days, in both NS and Activin A pretreatment conditions (Fig. 2A,C). Importantly, fluorescence intensity was higher in NALM6 Activin A compared to NALM6 NS at 5 days and 7 days post-injection (Fig. 2A,C). The interaction with the brain parenchyma was necessary to increase the proliferation of Activin A-treated NALM6 cells, since Activin A alone was not able to significantly modify leukemic cell proliferation under standard liquid culture conditions (Figure S1). The invasiveness of NALM6-iRFP670 cells in the cerebral tissue 7 days after microinjection, was confirmed by confocal acquisitions showing the penetrance of injected cells into the brain parenchyma (Fig. 2D, orthogonal view).

NALM6 cell invasion and proliferation after microinjection into cortical brain slices by fluorescence microscopy analysis. (A) Representative fluorescence images of cortical brain slices to longitudinally monitor NALM6-iRFP670 cells pretreated with Activin A (NALM6 Activin A) or not (NALM6 NS) up to 7 days post microinjection. Scale bar = 1 mm (B) Quantification of the area occupied by NALM6-iRFP670 up to 7 days after microinjection, as an index of brain invasiveness. (C) Quantification of NALM6-iRFP670 integrated density fluorescence signal up to 7 days after microinjection as an index of blast proliferation. Data are expressed as median + interquartile range (box) with whiskers showing min and max values. N ≥ 4 slices/group. Data are the results of 3 independent experiments. Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA for repeated measurements, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Dotted line represents the baseline values obtained immediately after injection. (D) Overview image displaying NALM6-iRFP670 cell distribution in the cortical slice (dotted white line) 7 days after microinjection. The insert shows a representative 40 X magnification image with orthogonal projections showing NALM6-iRFP670 cells across the thickness of brain slice. Scale bar = 50 μm.

To further investigate the survival and proliferation rate of NALM6-iRFP670 cells in the cerebral tissue and the effect of Activin A pre-treatment, we performed flow cytometry analysis at 0, 1, 3 and 7 days after microinjection (Fig. 3). LIVE/DEAD assay showed a high viability (> 76%) of NALM-6 cells at all time points analyzed (Fig. 3B) in both NS and Activin A pretreatment conditions. In line with imaging data (Fig. 2C), the flow cytometric quantification of leukemic cells after brain tissue microinjection indicated an exponential increase overtime and a tendency towards higher numbers of NALM6 Activin A cells at day 3 and 7 compared to NALM6 NS (Fig. 3C).

NALM6 cell viability and proliferation after microinjection into cortical brain slices by flow cytometry analysis. (A) Flow cytometry plots showing Live/Dead cell staining in control (CTRL) slices, slices injected with NALM6-iRFP670 cells not stimulated (NALM6 NS) or pretreated with Activin A (NALM6 Activin A) at time 0, 24 h (h), 72 h and 7 days (d). Each plot was obtained from two pooled slices. (B) Percentage of viable NALM6-iRFP670 cells at time 0, 24 h, 72 h and 7 d after microinjection. (C) Graph showing the fold-change of NALM6-iRFP670 cells pretreated or not with Activin A at 0, 24 h, 72 h and 7 d after microinjection. The fold-change was calculated as number of total iRFP670-positive cells at the selected time-point/number of total iRFP670-positive cells at day 0. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 2 replicate (each composed of 2 different slices).

Overall, our data demonstrate that human leukemic cells survive and proliferate in the murine brain tissue and suggest that Activin A could promote leukemia proliferation, upon infiltration in the brain parenchyma.

Activin A-pretreated NALM6 cells induce brain cell death

We next tested the effects of NALM6 cell presence in the brain tissue, by analyzing cell death in cortical slices. Since the brain parenchyma, which is more fragile than NALM6 cells, can be compromised during the tissue processing required for flow cytometry evaluation, cell death in cortical slices was assessed by propidium iodide (PI) staining before cell microinjection (T0), 24 h, 72 h and 7 d after microinjection (Fig. 4A,B). Injection of NALM6 NS cells did not induce higher mortality rate than CTRL slices overtime. However, cortical slices microinjected with NALM6 Activin A showed a greater cell death compared to CTRL and NALM6 NS slices at both 72 h and 7 d post injection (Fig. 4A,B). Of note, the high viability of NALM6 cells assessed by flow cytometry 24 h after injection (> 92% as for Fig. 3B), suggests that the PI signal could be entirely ascribed to the brain tissue. Overall, these data indicate that Activin A pretreatment induces higher proliferative rate and higher malignancy to leukemic cells with a consequent increased mortality of brain tissue. To assess which cerebral populations were mostly affected by leukemic cells, we performed gene expression analysis on cortical slice tissue, 3 days after injection. No significant differences in the expression of the neuronal marker Map2 across groups was observed (Fig. 4C). However, compared to CTRL group, a significant downregulation of the astrocytic marker Gfap together with an upregulation of the microglial marker Cd11b in NALM6 Activin A group were observed (Fig. 4C).

Activin A pretreatment of NALM6 cells induces higher cell death of brain tissue. (A) Representative images displaying propidium iodide (PI) signal in control slices (CTRL), and slices microinjected with NALM6 cells not stimulated (NALM6 NS) or pretreated with Activin A (NALM6 Activin A) at baseline (0, before injection), 24 h (h), 72 h and 7 days (d). Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Fold-change representation of PI fluorescence signal at 24 h, 72 h and 7 d after leukemic cell microinjection over baseline (dotted line). Data are expressed as median + interquartile range (box) with whiskers showing min and max values. Data are obtained from 6 independent experiments (n > 20 slices/group). Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

NALM6 cells induce microglial activation in cortical slices, especially following activin A pretreatment

After analyzing the invasive and proliferative ability of NALM6 cells in the cortical slices, we next investigated how leukemic cells can modify the surrounding brain microenvironment and the potential impact of Activin A in this crosstalk. Indeed, we firstly focused on microglial cells, which exert a key role in homeostasis, and innate immunity in the CNS, given the observed upregulation of Cd11b expression. This cell subset proved to be highly plastic in response to external stimuli17 and to influence tumoral progression in the context of brain cancers21,22. We thus investigated the microglia response and interaction with leukemic cells, by exploiting transgenic CX3CR1+/GFP mice, which express GFP in microglial cells. We longitudinally monitored the fluorescent signal, as index of microglia activation23 (Fig. 5A). We observed that cortical slices microinjected with both NALM6 NS and NALM6 Activin A cells showed significantly higher GFP fluorescent signal compared to CTRL at 72 h (p = 0.0036 and p = 0.0022, Fig. 5B). Interestingly, this effect was statistically significant also at days 5 and 7 only in NALM6 Activin A slices (p = 0.0045 and p = 0.0352, Fig. 5B).

Longitudinal quantification of microglial cell activation in CX3CR1+/GFP cortical slices microinjected with NALM6 cells. (A) Representative fluorescence images of cortical slices obtained from CX3CR1+/GFP mice and microinjected with vehicle (CTRL), NALM6 cells not stimulated (NALM6 NS) or pretreated with Activin A (NALM6 Activin A). Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Quantification of Integrated Density (IntDen) GFP signal at 24 h (h), 48 h, 72 h, 5 days (d) and 7 d after leukemic cell microinjection and fold change representation compared to baseline (dotted line). Data are expressed as median + interquartile range (box) with whiskers showing min and max values. Data are obtained from 2 independent experiments (n ≥ 5 slices/group). Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

To further investigate the effects of leukemia-microglial cell crosstalk within the cortical slices, we analyzed the morphological changes after NALM6 microinjection, employing an in-depth shape descriptor analysis of single CX3CR1+/GFP microglial cells at 3 and 7 days (Fig. 6A). At 3 days, no significant morphological differences were observed in slices injected with NALM6 NS cells compared to CTRL, except for a slight and transient increase of circularity, indicative of a round-shaped microglia morphology, detected in NALM6 Activin A injected slices compared to both CTRL and NALM6 NS groups (Fig. 6B). On the contrary, at day 7 we observed major microglia morphological modifications induced by NALM6 cells with greater effects obtained with Activin A pretreated cells. In detail, compared to CTRL, NALM6 NS cells induced an increase of microglial perimeter and Feret’s diameter and a reduction of circularity. These effects were even more pronounced in NALM6 Activin A microinjected slices, that showed also a significant increase of cell area, a decrease of cell solidity and an increase of aspect ratio (Fig. 6B). Overall, all these parameters indicate a modulation by NALM6 cells, especially after Activin A pre-treatment, of microglial morphology from amoeboid, typical of an activated and phagocytic phenotype, toward a more ramified one, less reactive toward leukemic cells24. Figure 6C shows a cluster of NALM6 cells preactivated with Activin A (and labelled with Hoechst before infusion), in contact with ramified microglia cells.

Microglia morphological changes after leukemic cells microinjection. (A) Representative confocal images of control (CTRL) CX3CR1+/GFP cortical slices or microinjected with NALM6 not stimulated (NALM6 NS) or pretreated with Activin A (NALM6 Activin A), at 7 days. The panel shows representative overviews (scale bar = 1 mm) and higher magnification images (scale bar = 100 μm). Inserts show representative microglial cell morphology. (B) Graphs show the quantification of microglia morphometric cell parameters at day 3 and 7: cell area, perimeter, circularity, Feret’s diameter, solidity and aspect ratio. The drawings beside the y-axis indicate expected values for each parameter depending on cell shape or cell symmetry. N = 3 cortical slices/group, each slice is the results of 6 ROIs, data are expressed as floating bars (median + min to max). Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. (C) Representative image of microglial cells (Cx3Cr1+ cells, green) and NALM6 pretreated with Activin A (blue). Bar = 50 μm

We next investigated at the molecular level the expression of mouse genes crucial for microglial activation and functions and their possible modifications upon NALM6 NS or Activin A microinjection. We already showed an upregulation of microglia pan marker Cd11b, in Activin A pre-treated NALM6 (Fig. 4C). This activation was coupled with an increased expression of Ccl2, a chemokine involved in myeloid cell recruitment and activation (Fig. 7A). No significant differences across groups were observed for Cd68 (a marker associated with phagocytic activity, Fig. 7B) nor Cd86 (associated with antigen presentation, Fig. 7C). However, when analyzing pro-inflammatory microglial genes, such as Nos2 and Pai1, we observed a general downregulation induced by NALM6 cells (Fig. 7D-E), with the most relevant effect observed for Pai1 expression in NALM6 Activin A slices (Fig. 7E). Alongside, NALM6 cells promoted the increase of the anti-inflammatory gene Arginase 1, which reached statistical significance in the NALM6 Activin A group (Fig. 7F). On the overall, these data suggest that leukemic cells can shape microglial-related neuro-inflammatory milieu and Activin A can amplify these effects.

Modulation of microglial gene expression after NALM6 cell microinjection. Gene expression of murine Cd11b (A), Nos2 (B), Pai1 (C) and Arginase 1 (D) at 72 h in control (CTRL) slices or slices microinjected with NALM6 not stimulated (NALM6 NS) or pretreated with Activin A (NALM6 Activin A). Data are expressed as median + interquartile range (box) with whiskers showing min and max values. n = 7 slices for each group. Data are analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

NALM6 cells induce morphological changes in cortical slice astrocytes

We next focused our attention on how the astrocyte population could be shaped by the interaction with leukemic cells. With this aim, CTRL, NALM6 NS and NALM6 Activin A slices were stained after 72 h with an anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody to visualize astrocyte morphology (fibrous vs. protoplasmic shape) in relation to their proximity to tumor area (Fig. 8A,B). While the percentage of GFAP+ area and cell integrated density were comparable among groups (Fig. 8C,D), significant morphological changes were instead observed in leukemia-exposed astrocytes, compared to CTRL. In detail, within the injection zone, astrocytes showed a fibrous morphology in CTRL slices, while they showed a protoplasmic structure in both NALM6 NS and NALM6 Activin A slices (p = 0.0165 and p = 0.0307, Fig. 8B). A similar leukemia-driven effect was observed also in the peritumoral zone and in the periphery, especially in the Activin A pretreated group (Fig. 8E). Figure 8F shows a cluster of NALM6 cells preactivated with Activin A (and labelled with Hoechst before infusion), in contact with protoplasmic astrocytes.

Morphological analysis of astrocytes in different areas of cortical slices after NALM6 cell microinjection. (A) Representative bright-field image and corresponding NALM6-iRFP670 cell fluorescent signal (72 h) for ROI delimitation: injection site (yellow), peritumoral zone (green) and periphery (blue). (B) Representative images of astrocyte morphology in different cortical slice areas (scale bar = 50 μm). (C) Quantification of GFAP% stained area. (D) Quantification of GFAP integrated density. (E) Quantification of morphological score (0 = fibrous shape; 1 = protoplasmic shape). (F) Representative image showing GFAP+ cells (green) and NALM6 pretreated with Activin A (blue). Bar = 50 μm. Data are expressed as median + interquartile range (box) with whiskers showing min and max values. Data are analyzed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Overall, these data suggest changes in the microenvironment that favor the activation of protoplasmic astrocytes, indicative of an astrocyte activation in response to tumor.

Discussion

In the present work we developed an ex vivo 3D model of brain leukemia, based on organotypic cortical brain slices subjected to the microinjection of a B-ALL cell line, namely NALM6 cells. Most studies of in vitro CNS involvement in the context of ALL, exploit simplified two-dimensional methods such as: (i) the in vitro co-culture system, to investigate the factors that facilitate leukemia cell survival into the CNS25,26,27 and (ii) Boyden chamber/transwell assays, to study migration of tumor cells across brain barriers28,29. However, these cell culture models, lacking a complex 3D architecture, cellular diversity, extracellular matrix and spatial distribution, as well as all the microenvironmental influences30, show limits to accurately predict the effect of small molecules and drugs on tumor cell invasion and behavior in vivo. In this study, we generated and optimized an ex vivo system to mimic the complexity of the brain microenvironment, bridging the gap between 2D cell culture models and the more complex in vivo orthotopic transplantations. The use of organotypic brain slices can be an ideal platform to investigate the changes induced by infiltrating solid and hematological tumor cells and to identify key pathways in the cancer cell/ brain microenvironment crosstalk. Our model relies on viable cortical postnatal brain slices, that can be microinjected, in a spatially restricted manner, with cancer cells and kept in culture for subsequent cellular and molecular assays. Each mouse pup can provide up to eight to ten cortical slices, opening up to the possibility to use this model for investigating the ability of specific molecules to modulate cancer cell infiltration/proliferation into the CNS niche or for translational studies, including drug testing. As a proof of principle, we microinjected cortical slices with the B-ALL cell line NALM6, that is endowed with a prominent CNS tropism, as demonstrated in immunodeficient xenograft mouse models10,19. In these mouse models, NALM6 cells were shown to reach the leptomeninges, similarly to the human pathology, and to infiltrate neurogenic niches, such as the subventricular and submarginal zones10. Thanks to our microinjection system we were able to investigate the persistence of NALM6 cells in the brain organotypic slices and the changes induced in key cell subsets of the CNS microenvironment. Furthermore, the creation of a genetically modified cell line, stably expressing the iRFP670 fluorescent protein, gave us the possibility to monitor NALM6 cell persistence, proliferation and invasiveness directly into the organotypic slice, by fluorescent imaging. Of note, this tracking methodology could be applied to every cancer cell expressing a fluorescent reporter, rendering the organotypic brain slice a platform easily translatable to several cancer pathologies with CNS involvement.

We further used the organotypic brain slice model to investigate the leukemia-promoting role of Activin A in the CNS niche. Despite its prominent role in the progression of solid cancers31, the involvement of Activin A, a member of the TGF-β family, in the pathogenesis of hematological malignancies, including B-ALL, has been explored only in recent studies19,32. We demonstrated that Activin A promotes leukemia progression and provides a migratory advantage to B-ALL cells over healthy hematopoietic cells, thus suggesting this molecule as a possible pharmacological target. Of note, Activin A-pretreated NALM6 cells showed an increased ability to engraft in vivo in the BM, meninges and brain of NSG mice19. Starting from these observations and in accordance with recent works describing Activin A as key factor increasing invasive properties of solid tumors33,34,35,36, we aimed at evaluating how pre-stimulation of NALM6 cells could affect their interaction with brain tissue, to test the sensitivity of our model to detect possible disease modifying factors.

In our CNS leukemia model, we showed that NALM6 cells were able, upon injection, to survive, proliferate and invade the cortical brain slices. Indeed, we showed an exponential increase of the area occupied by NALM6-iRFP670 cells up to 7 days after microinjection and, by means of flow cytometry, a high viability of leukemic cells at all the timepoints analyzed. Furthermore, by confocal microscopy, we demonstrated that, resembling the in vivo setting, leukemic cells were able to proliferate and move from the initial injection site, invading cortical slice tissue. This finding is in accordance to what has been observed in late-stage B-ALL CNS disease, where leukemic cells, after invading leptomeninges, can eventually break CNS barriers and disseminate into the CNS parenchyma37. Cortical slices microinjected with Activin A-pretreated NALM6-iRFP670 cells showed, over time, an equally spread fluorescent signal compared to control cells, suggesting a comparable ability to invade the brain parenchyma. Interestingly, integrated fluorescence signal significantly increased at 5 and 7 days in case of Activin A-pretreatment, suggesting that this molecule could enhance the proliferation of leukemic cells in the cerebral tissue. Alongside, Activin A-pretreated NALM6 cells induced mortality in the surrounding cerebral tissue, likely as a consequence of their high rate of growth.

As previously mentioned, we utilized our 3D CNS leukemia model, which retains the native architecture of cortical tissue, to study brain-leukemia interactions. In this physiological environment, closely mimicking the in vivo setting, we demonstrated that B-ALL cells can induce microenvironmental changes prone to their permanence in the cerebral tissue. Indeed, solid and hematological cancer cells can actively crosstalk with the surrounding microenvironment, creating tumor-promoting niches able to nurture and shelter them from therapy. The brain represents an immune-privileged site, composed by several cell subsets highly reactive to external stimuli, including microglial cells, astrocytes and others. In this context, it has been shown that microglial cells possess different functional phenotypes, depending on environmental stimuli38. It has been demonstrated that glioblastoma cells can hijack gene expression profiles in the neuroimmune system to promote suppression of the immune response, enhancing tumor propagation21. Indeed, we used our model to investigate whether leukemic cells can modify the brain microenvironment inducing function-related morphological changes in microglial and astrocytic cells and the potential impact of Activin A in shaping the cerebral niche. We observed a marked activation of microglia after leukemic cells microinjection, as demonstrated by the increase of fluorescent signal in CX3CR1+/GFP slices and by the up-regulation of Cd11b gene expression, a pan-marker of microglia activation39. Interestingly, a clear-cut promoting effect on microglial activation was observed in case of Activin A pre-stimulation of leukemic cells. Microglial activation was associated with a reduction of pro-inflammatory mediators (such as PAI1 and Nos2 genes) and an induction of anti-inflammatory genes (upregulation of Arginase 1), more pronounced following the microinjection of NALM6 Activin A. The modulation of inflammation-related genes was accompanied by microglia morphological changes which, once more, were amplified by Activin A pre-treatment of microinjected leukemic cells. In detail, we observed an increased microglia cell area, perimeter and Feret’s diameter, indicative of a more ramified morphology, confirmed by the reduction of solidity and circularity parameters, that are indicative of an ameboid shape. Globally, these data suggest that NALM6 cells are able to exploit the surrounding microenvironment, promoting a leukemia-supportive milieu, by inducing microglial cells towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype, characterized by a less reactive/phagocytic activity and that Activin A can crucially contribute to CNS microenvironment reshaping. Besides microglia, several studies have shown that astrocytes may also play an important function in the context of brain tumors40,41, by secreting growth factors promoting their proliferation42,43,44. We observed a clear downregulation of Gfap mRNA expression at 3 days post-injection, that however was not accompanied by a corresponding decrease in GFAP-immunoreactive area at the histological level. This discrepancy may reflect a temporal lag between transcriptional downregulation and subsequent protein turnover. Nevertheless, we observed a clear morphological shift of the astrocyte shape from a fibrous toward a protoplasmic one, following leukemia cell microinjection. The shapeshifting of reactive astrocytes depends on the nature and severity of the CNS insult: in the early stage of malignancies, reactive astrocytes express GFAP and Nestin and present a round-shaped body, while in more advanced tumor progression phases, astrocytes show a larger cell size with longer and thicker processes45. Subsequently, tumor cells can “transform” astrocytes, enabling them to provide drug resistance and favor growth and invasiveness41,46,47,48,49. Further analyses will investigate whether the leukemia-promoted changes in astrocyte morphology, observed in our model, could be associated to a specific “astrocyte signature”, possibly favoring tumor-growth and proliferation and they will elucidate the role of Activin A in this crosstalk. Since NALM6 cells were the sole exposed to Activin A stimulation we can exclude a direct effect of the cytokine on the cerebral microenvironment. We can otherwise hypothesize that the modifications observed in the cortical slice microenvironment could be the result of the crosstalk of Activin A-stimulated leukemic cells with the surrounding cell subsets. This interaction could be achieved both by direct cell-to-cell contact, but also through the release of soluble factors. In this regard, we recently published a study demonstrating that Activin A can enhance the release of extracellular vesicles from B-ALL cell lines, while also modifying their miRNA cargo50. This alteration proved to strengthen the crosstalk between leukemic cells and potentially with cells of the microenvironment.

In conclusion, we established an innovative and reliable ex vivo model to study the interaction between leukemia cell and brain tissue, both at cellular and molecular levels. In addition, the identification of Activin A as a pivotal molecule influencing leukemia survival and aggressiveness in brain tissue provides compelling evidence of our model’s sensitivity in detecting disease-modifying factors. This work opens new perspectives for the identification of molecules responsible for brain microenvironment changes and tumor progression and for the design of therapeutic approaches for B-ALL CNS treatment, targeting the interplay between leukemic cells and the brain microenvironment. Importantly, our platform has the versatility to be potentially applied across different types of cerebral tumors for screening novel drugs, targeting both cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment.

Methods

Culture of the NALM6 B-ALL cell line

The B-ALL cell line NALM6 (DSMZ number: ACC128; DSMZ, Germany) was maintained in Advanced RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, GE Healthcare), penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 µg/mL) and L-glutamine (2 mM) (Euroclone, Milan, Italy). NALM6 cells were cultured under standard humidified conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Cell identity was confirmed by FISH assay using XL 5q32 PDGFRB BA Probes (MetaSystems, GmbH), acquisition and analysis by Neon 1.2.9 software (MetaSystems, GmbH).

The Activin A (R&D Systems, USA) pretreatment was achieved culturing NALM6 cells with Activin A (50 ng/mL) for 24 h.

Generation of iRFP670 Nalm6 cells

NALM6 cells were genetically modified to express the iRFP670 protein as a reporter gene, to allow longitudinal cell tracking. IRFP670 insert was cloned into the Sleeping Beauty transposon DNA plasmid pT-MNDU3 (pTMNDU3-IRFP670). 1 × 106 NALM6 cells were then nucleofected with 5 µg of pTMNDU3-IRFP670 and 2 µg of pCMV-SB11 plasmid, encoding for the SB11 transposase, in the appropriate SF Cell Line Nucleofector Solution and transferred into Amaxa certified cuvette (LONZA, Basilea, Switzerland). NALM6 nucleofection was performed using protocol CV-104 on the AMAXA Nucleofector 4D-X Unit platform (LONZA, Basilea, Switzerland). The cells where then moved into culture plates filled with pre-warmed medium and placed in humified 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator. IRF670-positive cells were then sorted twice (MoFlo Astrios Cell Sorter- Beckman Coulter, Brae, CA) to obtain a population of cells expressing the reporter gene > 90%, as described in Supplementary Fig. 1A-C. After double sorting NALM6-iRFP670 cells were then expanded until day + 36 from the first sorting and the stability of the iRFP670 signal was verified by flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II, Supplementary Fig. 2D-E). FCSExpress 7 research edition was used to analyze FCS files and create Figure S2. cells were then expanded and used to perform different experiments.

Animals

C57BL/6-Cx3cr1em1Mbur/J51 mice (CX3CR1+/GFP, Harlan, Italy, Strain#:037016, RRID: IMSR_JAX:037016) and C57BL/6J (Charles River, Italy) mice were bred (one male and two females per cage) in a specific pathogen free vivarium at a constant temperature (21 ± 1 °C) and relative humidity (60 ± 5%) with a 12 h light/dark cycle and free access to pellet food and water. Male and female P1-P3 pups were used in this study. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. The authors complied with ARRIVE guidelines.

Organotypic cortical brain slice culture

Organotypic cortical brain slices (referred to as “cortical slices” from now on) were obtained from the prefrontal cortex of C57BL/6 or CX3CR1+/GFP mouse pups (P1-P3) as previously described16,17 and as illustrated in Figure S3. A sterile working condition was set up for the collection of sections to avoid any contamination. Mouse pups were euthanized through decapitation, brains were harvested from the skull and rapidly immersed in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solution (NaCl = 87 mM, NaHCO3 = 25 mM, NaH2 PO4 = 1.25 mM, MgCl2 = 7 mM, CaCl2 = 0.5 mM, KCl = 2.5 mM, D-glucose = 25 mM, sucrose = 75 mM, Penicillin = 50 U/ml, Streptomicin = 50 µg/ml) prior saturated with carboxigen (95% O2 and 5% CO2) and placed under ice-cold conditions. Brains were then transferred into a 35-mm2 dish with a pre-warmed 3% agar (low melting point) solution. After cooling on ice, the tissue block was cut and glued to specimen discs of a vibratome (Leica, VT 1000 S). The sectioning chamber was filled with ice-cold ACSF. Prefrontal cortex coronal sections of 200 μm thickness were cut with vibrating frequency set at 100 Hz and speed at 4 mm/s. The sections were collected into a petri dish filled with cold ACSF. Cortical slices were placed on the membrane of tissue culture inserts (Millicell Culture insert, 0.4 μm pore size, Merk-Millipore) with two slices per insert which was moved in a six-well plate filled with 1mL of culture medium (MEM-Glutamax 25%, basal medium eagle 25% (Invitrogen), horse serum 25% (Euroclone), glucose 0.6%, Penicillin 100 U/ml, Streptomicin 100 µg/mL; pH = 7.2) and cultured in the incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2). After 2 days the incubation medium was changed with Neurobasal/B27 (Neurobasal A, B27 1:50, L-glutamine 1:100, penicillin 100 U/mL, streptomycin 100 µg/mL) and then replaced after every 2 days. After 7 days of recovery from the cut, the cortical slices were microinjected with leukemia cells. Depending on the analysis to be performed at selected time points, cortical slices were detached from membrane and stored at -80 °C for subsequent gene RNA extraction or fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and then maintained in 0.3% sodium azide (NaN3) for immunofluorescence analysis.

NALM6 cell microinjection in cortical slices

NALM6 or NALM6-iRFP670 were pretreated or not with Activin A 24 h before the injection into cortical slices (Fig. 1). In a set of experiment NALM6 cells were labeled with 5 µg/mL Hoechst-33,258 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h (h) at 37 °C before microinjection. On day 0, NALM6 cells (pretreated or not with Activin A) were centrifuged and resuspended in NB/B27 at concentration 105 cells/1µl.The cells were then loaded into a Hamilton syringe (10 µl capacity). A total of ≃ 10,000 cells loaded in 0.1 µl of NB/B27 were microinjected in the center of the cortical slice at 100 μm depth by using an infusion pump at speed 0.5 µl min− 1. Control (CTRL) cortical slices were microinjected with an equal amount of NB/B27. Immediately after microinjection, pictures of fluorescent signal were acquired using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope (Cell F software, version 2.6) to verify the accuracy of the microinjection and to get the baseline iRFP670 signal for every single cortical slice. NALM6-iRFP670 cells were monitored overtime until the end of experimental procedure.

NALM6-iRFP670 cell tracking in cortical slices

iRFP670 fluorescence signal was longitudinally acquired in order to quantify NALM6 cell proliferation and their invasion capacity in cortical slices. Fluorescence images of NALM6-iRFP670 cells were acquired at time 0 (immediately after microinjection), 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 5 days (d) and 7 d after microinjection. Invasion and proliferation of NALM6-iRFP670 cells were quantified as the area of iRFP670 fluorescence signal and Integrated Density (IntDens) using Fiji (Fiji is Just ImageJ, https://imagej.net/software/fiji/downloads)52. The area occupied by NALM6–iRFP670 cells and respective integrated density of fluorescence signal at each time points were measured and normalized as fold change over time 0. Confocal images were acquired by a Nikon A1 confocal microscope to detect the capacity of NALM6–iRFP670 cells to invade cortical slices. Whole brain slices were imaged at laser excitation of 640 nm with a sequential scanning mode to avoid bleed-through effects. Z-stacks of 15 μm were acquired with a 40 × 0.75 NA objective. Each image was 1024 × 1024, having a pixel size of 0.31 μm and a step size of 1 μm. Images were processed with Fiji software.

Growth curve of NALM6-iRFP670 cells stimulated or not with activin A

NALM6-iRFP670 cells were seeded in 96-well plates coated with a 0.01% poly-L-ornithine solution (Merck, Germany) in Advanced RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and L-glutamine, as previously described. Cells were plated at two different densities (10,000 and 20,000 cells per well) in triplicate for each condition. Activin A or its vehicle was added on day 0. Cell growth was monitored for 7 days using the Incucyte SX5 live-cell analysis system (Sartorius, Germany), measuring the number of Near-Infrared (NIR) + objects per well and confluence based on phase contrast images. Four images were acquired per well every 6 h.

Cell dissociation and viability analysis of slice-microinjected NALM6 cells

After NALM6-iRFP670 cell microinjection, cortical slices were dissociated at time 0 (immediately after injection), 24 h, 72 h and 7 d, and viability assay performed. Pooled cortical slices (2 cortical slices for each experimental group per time point, n = 2 replicates) were mechanically dissociated on a cell strainer (Greiner EASY strainer, 70 μm pore size) using the plunger of a 5 mL syringe. The filter membrane was washed with 2 mL of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) + 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and the obtained suspension was kept on ice, centrifuged (1500 rpm for 7 min at + 4 °C) and then stained with a LIVE/DEAD™ dye (Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milan, Italy, using 405 nm excitation and ~ 525 nm emission). After 20 min, fresh stained cell suspension was analyzed by a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX LX, Beckman Coulter). The number of NALM6–iRFP670 cells pretreated or not with Activin A at all time points was normalized as fold change over the number of cells microinjected at time 0. Slices microinjected with NB/B27 represent the control group (CTRL). The offline analysis was performed using Kaluza software version 1.2 (Beckman Coulter, Brae, CA).

Assessment of cell death in cortical slices

Cell death was measured on cortical slices by propidium iodide (PI) incorporation assay (Sigma Aldrich) as previously described17. This quantification was performed longitudinally before NALM6 microinjection (basal) and at 24 h, 72 h and 7 d after NALM6–iRFP670 cell microinjection. The tissue culture inserts were moved to a new plate with fresh NB/B27 containing 2 µM PI. After 30 min of incubation, the cortical slices were washed once with PBS and a complete medium change was performed thereafter. Images were captured at 4 X magnification using an Olympus IX71 microscope. Fluorescence intensity per slice was measured using Fiji’s Integrated Density function and the value was normalized over the slice area. PI increment was calculated over basal integrated density.

Real time RT-PCR

Seventy-two hours after microinjection of NALM6 cells pretreated or not with Activin A, cortical slices were collected and stored at -80 °C until analysis. Total RNA was extracted using GeneAllRibospin II kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was then quantified using Nanodrop and reverse-transcribed with High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription (RT) kit (Applied Biosystem). Real time RT-PCR was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression of the following murine genes was evaluated: Map2, Gfap, Cd11b, Ccl2, Cd68, Cd86, Nos2, Pai1 and Arg1. Ribosomal protein L27 (RpL27) was used as a reference gene and relative gene expression levels were calculated according to the manufacturer’s ΔΔCt method (Applied Biosystem). Primers were designed to selectively match mouse but not human sequences using Primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0). Primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Microglial cell fluorescence acquisition and quantification

In selected experiments, in order to assess microglia activation after NALM6 microinjection, cortical slices obtained from CX3CR1+/GFP mice, expressing GFP protein in microglial cells51 were used. GFP signal was longitudinally detected using fluorescence Olympus IX71 microscope. Images were captured at time 0, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 5 d and 7 d after microinjection at 4 X magnification. Fluorescence intensity per slice was measured using Fiji’s Integrated Density function and the value was normalized over the slice area. Integrated density at all time points analysed was expressed as fold change over the basal.

Morphological analysis of microglial cells

Seventy-two hours and 7 d after NALM6 cell microinjection, CX3CR1+/GFP cortical slices were fixed with 4% PFA and mounted on a slide with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermofisher). Confocal images were acquired by a Nikon A1 confocal microscope at laser excitation of 450–490 nm with a sequential scanning mode to avoid bleed-through effects. Overview sections were acquired at 20 X and a concentric grid centered in the site of injection and distanced 500 μm was used to define concentric areas. A total of 6 images per slice were acquired. For microglial morphological analyses, Z-stacks of 15 μm were acquired with a 40 × 0.75 NA objective. Each image was 1024 × 1024, having a pixel size of 0.31 μm and a step size of 1 μm. Images were processed and analyzed using Fiji software. For each single Region of Interest (ROI), Z-Projections were merged to obtain an image with maximum fluorescent intensity. Microglia morphology was analyzed, as previously described23,53. The following shape descriptors were used to analyze microglial cell morphology: perimeter, area, Feret’s diameter (caliper), aspect ratio, circularity and solidity. Mean values for each parameter were used for statistical analysis. Three different cortical slices per experimental group were acquired and analyzed.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF assays were performed in free-floating. PFA-fixed cortical slices were detached from the porous membrane of cell culture insert with the aid of a spatula and a stereo microscope and placed in a 96-well plate with 0.01 M PBS. After 3 washes in 0.01 M PBS, a blocking-permeabilizing solution consisting of 0.01 M PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 10% normal goat serum was added. Cortical slices were blocked for 30 min at RT on orbital shaker, using low speed. Cortical slices were incubated overnight at + 4 °C with primary antibody mouse anti GFAP (MERCK, AB5804, 1:2000) in 0.01 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 2% normal goat serum. After 3 washes in 0.01 M PBS, cortical slices were incubated with anti-mouse 488-Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies in a solution consisting of 0.01 M PBS with 1% normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. After the final washes in 0.01 M PBS cortical slices were carefully mounted on a slide, making sure there are no wrinkles or folds and mounted with FluorSaveReagent™ (Merk-Millipore) mounting medium and with a glass coverslip.

Morphological analysis of astrocyte cells

GFAP stained cortical slices were acquired at Nikon A1 confocal microscope. Overview sections were acquired at 20 X. ROI related to injection site was drawn based on NALM6–iRFP670 signal. Two additional circle grids spaced 500 μm were imposed to define peritumoral zone and periphery. In each ROIs, 4 representative images were acquired at 40 X. Z-stack pictures were taken at 40 X over a 15 μm z-axis with a 1 μm step size. Images were processed and analyzed using Fiji software. For each single ROI, Z-Projections were merged to obtain an image with maximum fluorescent intensity. For the morphological analysis of astrocytes, images were scored by two independent investigators blinded to the experimental group. A score of 0 was assigned to images with astrocytes with fibrous morphology and 1 for protoplasmic morphology40,54. The scores of each single ROI belonging to the same representative area of cortical slice were averaged and statistically analyzed.

Randomization and blinding

For each experiment, slices were randomly allocated to the experimental group, using a randomization list produced with https://www.random.org/lists/. All evaluations were done blinded to the experimental group allocation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a standard software package (GraphPad Prism Inc., San Diego, CA, USA, version 8.0). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. For leukemia cells proliferation and microglia activation, experimental groups were compared using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measurements followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. For cell death assay, gene expression analysis, microglia shape descriptors, and astrocytes morphology score, experimental groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Probability values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The dataset presented in this study can be found at: https://zenodo.org/records/11198159. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in supplementary information files.

References

Pui, C. H. Precision medicine in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Med. 14, 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-020-0759-8 (2020).

Xu, L. H. et al. Prognostic significance of CNSL at diagnosis of childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the South China children’s leukemia group. Front. Oncol. 12, 943761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.943761 (2022).

Tang, J. et al. Prognostic factors for CNS control in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated without cranial irradiation. Blood 138, 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020010438 (2021).

Thastrup, M., Duguid, A., Mirian, C., Schmiegelow, K. & Halsey, C. Central nervous system involvement in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: challenges and solutions. Leukemia 36, 2751–2768. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01714-x (2022).

Frishman-Levy, L. & Izraeli, S. Advances in Understanding the pathogenesis of CNS acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and potential for therapy. Br. J. Haematol. 176, 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14411 (2017).

Vagace, J. M., de la Maya, M. D., Caceres-Marzal, C., Gonzalez de Murillo, S. & Gervasini, G. Central nervous system chemotoxicity during treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 84, 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.04.003 (2012).

Genschaft, M. et al. Impact of chemotherapy for childhood leukemia on brain morphology and function. PLoS One. 8, e78599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078599 (2013).

Jacola, L. M. et al. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive outcomes in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on a contemporary chemotherapy protocol. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 1239–1247. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.3205 (2016).

Krishnan, S. et al. Temporal changes in the incidence and pattern of central nervous system relapses in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated on four consecutive medical research Council trials, 1985–2001. Leukemia 24, 450–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2009.264 (2010).

Fernandez-Sevilla, L. M. et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells are able to infiltrate the brain subventricular zone stem cell niche and impair neurogenesis. Haematologica 107, 1004–1007. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2021.279383 (2022).

Humpel, C. Organotypic brain slices of ADULT Transgenic mice: A tool to study Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 16, 172–181. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205016666181212153138 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Brain aging is faithfully modelled in organotypic brain slices and accelerated by prions. Commun. Biol. 5, 557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03496-5 (2022).

Ucar, B., Stefanova, N. & Humpel, C. Spreading of aggregated alpha-Synuclein in sagittal organotypic mouse brain slices. Biomolecules 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12020163 (2022).

Morrison, B. 3, Cater, H. L., Benham, C. D., Sundstrom, L. E. & rd, & An in vitro model of traumatic brain injury utilising two-dimensional stretch of organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods. 150, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.06.014 (2006).

Li, Q., Han, X. & Wang, J. Organotypic hippocampal slices as models for stroke and traumatic brain injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 4226–4237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-015-9362-4 (2016).

Pischiutta, F. et al. Protection of brain injury by amniotic mesenchymal stromal cell-secreted metabolites. Crit. Care Med. 44, e1118–e1131. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001864 (2016).

Pischiutta, F. et al. A novel organotypic cortical slice culture model for traumatic brain injury: molecular changes induced by injury and mesenchymal stromal cell secretome treatment. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 17, 1217987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2023.1217987 (2023).

Minami, N. et al. Organotypic brain explant culture as a drug evaluation system for malignant brain tumors. Cancer Med. 6, 2635–2645. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1174 (2017).

Portale, F. et al. ActivinA: a new leukemia-promoting factor conferring migratory advantage to B-cell precursor-acute lymphoblastic leukemic cells. Haematologica 104, 533–545. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2018.188664 (2019).

Fernandez-Sevilla, L. M. et al. High BMP4 expression in low/intermediate risk BCP-ALL identifies children with poor outcomes. Blood 139, 3303–3313. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021013506 (2022).

Maas, S. L. N. et al. Glioblastoma hijacks microglial gene expression to support tumor growth. J. Neuroinflamm. 17, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01797-2 (2020).

Markovic, D. S., Glass, R., Synowitz, M., Rooijen, N. & Kettenmann, H. Microglia stimulate the invasiveness of glioma cells by increasing the activity of metalloprotease-2. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 64, 754–762. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jnen.0000178445.33972.a9 (2005).

Zanier, E. R., Fumagalli, S., Perego, C., Pischiutta, F. & De Simoni, M. G. Shape descriptors of the never resting microglia in three different acute brain injury models in mice. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 3, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-015-0039-0 (2015).

Vidal-Itriago, A. et al. Microglia morphophysiological diversity and its implications for the CNS. Front. Immunol. 13, 997786. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.997786 (2022).

Krause, S. et al. Mer tyrosine kinase promotes the survival of t(1;19)-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in the central nervous system (CNS). Blood 125, 820–830. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-06-583062 (2015).

Si, M. et al. The role of cytokines and chemokines in the microenvironment of the blood-brain barrier in leukemia central nervous system metastasis. Cancer Manag Res. 10, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S152419 (2018).

Jonart, L. M. et al. Disrupting the leukemia niche in the central nervous system attenuates leukemia chemoresistance. Haematologica 105, 2130–2140. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.230334 (2020).

Wigton, E. J., Thompson, S. B., Long, R. A. & Jacobelli, J. Myosin-IIA regulates leukemia engraftment and brain infiltration in a mouse model of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Leukoc. Biol. 100, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.1A0815-342R (2016).

Akers, S. M. et al. VE-cadherin and PECAM-1 enhance ALL migration across brain microvascular endothelial cell monolayers. Exp. Hematol. 38, 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exphem.2010.05.001 (2010).

Pampaloni, F., Reynaud, E. G. & Stelzer, E. H. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 839–845. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2236 (2007).

Loomans, H. A. & Andl, C. D. Intertwining of activin A and TGFbeta signaling: dual roles in Cancer progression and Cancer cell invasion. Cancers (Basel). 7, 70–91. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers7010070 (2014).

Portale, F. et al. Activin A contributes to the definition of a pro-oncogenic bone marrow microenvironment in t(12;21) preleukemia. Exp. Hematol. 73, 7–12e14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exphem.2019.02.006 (2019)..

Bashir, M., Damineni, S., Mukherjee, G. & Kondaiah, P. Activin-A signaling promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and metastatic growth of breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 1, 15007. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjbcancer.2015.7 (2015).

Bauer, J., Sporn, J. C., Cabral, J., Gomez, J. & Jung, B. Effects of activin and TGFbeta on p21 in colon cancer. PLoS One. 7, e39381. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039381 (2012).

Taylor, C. et al. Activin a signaling regulates cell invasion and proliferation in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 34228–34244. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5349 (2015).

Joshi, N. S. et al. Regulatory T cells in Tumor-Associated tertiary lymphoid structures suppress Anti-tumor T cell responses. Immunity 43, 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.006 (2015).

Lenk, L., Alsadeq, A. & Schewe, D. M. Involvement of the central nervous system in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: opinions on molecular mechanisms and clinical implications based on recent data. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 39, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-020-09848-z (2020).

Morgan, S. C., Taylor, D. L. & Pocock, J. M. Microglia release activators of neuronal proliferation mediated by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt and delta-Notch signalling cascades. J. Neurochem. 90, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02461.x (2004).

David, S. & Kroner, A. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3053 (2011).

Schiweck, J., Eickholt, B. J. & Murk, K. Important shapeshifter: mechanisms allowing astrocytes to respond to the changing nervous system during development, injury and disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 261. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2018.00261 (2018).

Mega, A. et al. Astrocytes enhance glioblastoma growth. Glia 68, 316–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.23718 (2020).

Fitzgerald, D. P. et al. Reactive glia are recruited by highly proliferative brain metastases of breast cancer and promote tumor cell colonization. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 25, 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-008-9193-z (2008).

Pedersen, P. H. et al. Heterogeneous response to the growth factors [EGF, PDGF (bb), TGF-alpha, bFGF, IL-2] on glioma spheroid growth, migration and invasion. Int. J. Cancer. 56, 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910560219 (1994).

Le, D. M. et al. Exploitation of astrocytes by glioma cells to facilitate invasiveness: a mechanism involving matrix metalloproteinase-2 and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator-plasmin cascade. J. Neurosci. 23, 4034–4043. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04034.2003 (2003).

Schiffer, D., Annovazzi, L., Casalone, C., Corona, C. & Mellai, M. Glioblastoma: Microenvironment and niche concept. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11010005 (2018).

Gagliano, N. et al. Glioma-astrocyte interaction modifies the astrocyte phenotype in a co-culture experimental model. Oncol. Rep. 22, 1349–1356. https://doi.org/10.3892/or_00000574 (2009).

Yang, N. et al. A co-culture model with brain tumor-specific bioluminescence demonstrates astrocyte-induced drug resistance in glioblastoma. J. Transl Med. 12, 278. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-014-0278-y (2014).

Hallal, S. et al. Extracellular vesicles released by glioblastoma cells stimulate normal astrocytes to acquire a Tumor-Supportive phenotype via p53 and MYC signaling pathways. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 4566–4581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-018-1385-1 (2019).

Lin, Q., Liu, Z., Ling, F. & Xu, G. Astrocytes protect glioma cells from chemotherapy and upregulate survival genes via gap junctional communication. Mol. Med. Rep. 13, 1329–1335. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2015.4680 (2016).

Licari, E. et al. ActivinA modulates B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cell communication and survival by inducing extracellular vesicles production. Sci. Rep. 14, 16083. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66779-3 (2024).

Fumagalli, S., Perego, C., Ortolano, F. & De Simoni, M. G. CX3CR1 deficiency induces an early protective inflammatory environment in ischemic mice. Glia 61, 827–842. https://doi.org/10.1002/glia.22474 (2013).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019 (2012).

Moro, F. et al. Efficacy of acute administration of inhaled argon on traumatic brain injury in mice. Br. J. Anaesth. 126, 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.027 (2021).

Gottipati, M. K., Zuidema, J. M. & Gilbert, R. J. Biomaterial strategies for creating in vitro astrocyte cultures resembling in vivo astrocyte morphologies and phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 14, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobme.2020.06.004 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Comitato Maria Letizia Verga, Fondazione Matilde Tettamanti and Beat Leukemia association for their continuous support. We also would like to thank Dr. Sarah Tettamanti for her help in the generation of NALM6-iRFP670 cells.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) under IG 2019 - ID. 23354 project – P.I. D’Amico Giovanna; Beat Leukemia association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.D., F.P., N.D., E.R.Z., G.D.; Methodology: E.D., F.P., N.D., R.P., N.P., A.F.; Formal analysis: F.P., N.D., N.P.; Investigation: E.D., F.P., N.D., E.R.Z., G.D.; Data curation: E.D., F.P., N.D.; Writing - original draft: E.D., F.P., N.D.; Writing - review & editing: A.B., E.R.Z., G.D.; Supervision: E.R.Z., G.D.; Project administration: E.R.Z., G.D.; Funding acquisition: E.R. Z., G.D. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All experimental procedures involving animals and their care to obtain organotypic cortical brain slices were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines at the IRFMN - Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri. The IRFMN adheres to the principles set out in the following laws, regulations, and policies governing the care and use of laboratory animals: Italian Governing Law (D.lgs 26/2014; Authorisation n.19/2008-A issued March 6, 2008 by Ministry of Health); Mario Negri Institutional Regulations and Policies providing internal authorization for persons conducting animal experiments (Quality Management System Certificate – UNI EN ISO 9001:2008 – Reg. N° 8576-A); the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011 edition) and EU directives and guidelines (EEC Council Directive 2010/63/UE). They were reviewed and approved by the Mario Negri Institute Animal Care and Use Committee that includes ad hoc members for ethical issues, and by the Italian Ministry of Health (Decreto no. D/07/2013-B).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dander, E., Pischiutta, F., Di Marzo, N. et al. Development of a 3D ex vivo model of brain-leukemia interaction to study the role of activin A in the central nervous system microenvironment. Sci Rep 15, 18915 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03877-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03877-w