Abstract

In recent years, diabetes patients have been receiving more attention than ever when it comes to accepting their illness and managing it on their own. This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of a family-centered empowerment program (FCEP) on illness acceptance and self-management of patients with type 2 diabetes. We conducted a single-blind randomized controlled clinical trial with pre- and post-measurements on 60 patients with type 2 diabetes. Randomization was performed via block randomization with Sequential Numbered Opaque Sealed Envelopes. Participants were randomized into (1) FCEP (intervention group) or (2) usual care (control group). Data collection was conducted by using a demographic questionnaire, the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ), and the Diabetes Acceptance Scale (DAS). The assessment of outcome measures occurred at baseline and immediately, and six weeks after the intervention. The results showed that at the baseline, there was no significant difference between intervention and control groups in terms of illness acceptance (Intervention (I): 32.17 ± 10.59 vs. Control (C): 34.53 ± 10.6; p = 0.396). However, immediately after the intervention (I: 41.79 ± 8.94 vs. C: 34.86 ± 10.63; P = 0.008) and 6 weeks after the intervention (I: 47.1 ± 5.72 vs. C: 34.66 ± 10.54; P < 0.001), there was a significant difference between intervention and control groups in terms of illness acceptance. In addition, the results showed that, at the baseline, there was no significant difference between intervention and control groups in terms of self-management (I: 21.72 ± 5.36 vs. C: 22.96 ± 3.65; p = 0.305). However, immediately after the intervention (I: 30.93 ± 2.2 vs. C: 23.63 ± 2.95; P < 0.001) and 6 weeks after the intervention (I: 36.37 ± 2.39 vs. C: 23.26 ± 3.11; P < 0.001), there was a significant difference between intervention and control groups in terms of self-management. The findings of this study demonstrated that the FCEP intervention effectively improves illness acceptance and self-management. Healthcare practitioners, particularly nurses, can enhance the acceptance of illness and self-management in patients with type 2 diabetes through the implementation of the FCEP.

Ethical considerations: This study was approved by the Research Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (No: IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1403.002).

Protocol Registration: The study protocol was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (No: IRCT20240624062246N1, 16/07/2024).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Type 2 diabetes is a metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels resulting from insulin resistance and a relative deficiency of insulin1,2. In the past 50 years, there has been a dramatic increase in the incidence of diabetes, elevating it to the fifth leading cause of death globally, the fourth most frequent reason for physician consultations, and one of the largest epidemics of this century3,4,5. The rigorous demands of managing diabetes, coupled with the integration of intricate self-management regimens into daily life, have demonstrably resulted in significantly elevated levels of emotional distress, leaving individuals feeling overwhelmed, frustrated, and discouraged6,7. Consequently, these demands result in a decline in well-being, fostering a climate of anxiety and depressive symptoms8,9. In this context, the support of family members is crucial for diabetic patients to maintain motivation and improve their self-management behaviors10. Family-centered empowerment is a concept focused on strengthening the entire family unit (including the patient and other family members) to improve their overall health and well-being. Through family-centered empowerment, families experience improved quality of life, increased responsibility, better communication with healthcare providers, higher satisfaction with care, improved treatment response, fewer complications, reduced treatment costs, and a more positive approach to managing their disease11,12. The active involvement of the family is an essential component of family-centered empowerment, playing a crucial role in the process of evaluating and pinpointing the specific needs of each patient10. Many issues arise within the home environment due to insufficient awareness among patients and their families regarding proper patient care, stemming from inadequate access to our center or any reliable source capable of addressing their questions and concerns13.

Earlier studies examined the effects of family-centered empowerment programs (FCEP) on the self-management skills of patients suffering from various chronic diseases14,15. Given that the management of diabetes is largely carried out by patients and their families, self-management has emerged as the fundamental approach to diabetes care. Self-management is a process that involves actively participating in self-care activities, all with the goal of improving one’s behaviors and overall sense of well-being, leading to a healthier and happier life16. There is now substantial evidence of health benefits following self-management interventions in long-term conditions such as diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease17. Effective self-management of diabetes involves comprehensive planning for meals and physical activity, consistent blood glucose monitoring, adhering to prescribed diabetes medications, and proactively managing both hypo- and hyperglycemic episodes and any resulting illnesses18. The development of self-management treatment plans is a collaborative process, involving individualized consultations with a variety of healthcare professionals such as doctors, nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists to ensure a comprehensive and tailored approach to patient care19. It is widely acknowledged that effective self-management techniques can be highly relevant and beneficial for individuals diagnosed with diabetes, and accumulating evidence suggests a positive correlation between such techniques and a reduced risk of long-term complications associated with the disease20.

The acceptance of illness, which involves adapting to and coexisting with a chronic condition, is critically important for making successful lifestyle changes and enhancing overall well-being21. Individuals who acknowledge and accept their illness demonstrate a greater propensity to embrace and sustain beneficial health practices, resulting in a significant improvement in their overall well-being22.

The acceptance of illness allows patients to navigate the risks, restrictions, and difficulties of compromised health and continue living their lives with a sense of normalcy, adapting to their conditions as needed while maintaining a fulfilling lifestyle. Patients’ knowledge of their condition’s origins, effects, and potential complications fosters self-control and allows them to make informed decisions regarding health-promoting behaviors, ultimately improving both their lifespan and overall quality of life23. Many factors influence the acceptance of treatment, but one of the most significant is the patient’s commitment to regular healthy lifestyle choices that demonstrably improve treatment outcomes and the overall disease progression24.

Given the family’s foundational role in the societal structure, it is incumbent upon them to provide comprehensive and proper healthcare to the patient, as well as their surrounding community. Since home-based care constitutes the primary mode of treatment for diabetes, the significance of familial support in enabling patients to effectively manage the considerable psychological and physical stressors associated with the condition is paramount and cannot be overstated25. Providing care for patients with type 2 diabetes places a significant time commitment on caregivers, often leading to feelings of fatigue and the substantial burden of caregiving responsibilities26. The evidence shows that families of diabetic patients are keen to participate in healthcare activities, but may not understand how to do so effectively, leading to significant challenges27,28. Therefore, it may be useful to adopt methods that improve caregivers’ participation in caring for these patients by improving their knowledge and skills.

Aims of the study

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of FCEP on illness acceptance and self-management of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Hypothesis 1: FCEP leads to improvement in the illness acceptance of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Hypothesis 2: FCEP leads to improvement in self-management of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Study design

The current study involved a randomized clinical trial, utilizing both pre- and post-test assessments, which was carried out over a period of time, from February to October of 2024. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association29, the study protocol underwent a thorough review process, and subsequently, it received the necessary approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Also, to maintain adherence to the recommended standards, this study was performed, and the results were subsequently documented in accordance with the guidelines specified in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement30. Figure 1 illustrates the CONSORT flow diagram of the participants.

Participants and setting

The study’s participants were patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus who had been referred for treatment to the diabetes clinics located within four hospitals (Shohadaye Tajrish, Ayatollah Taleghani, Loghman-e Hakim, and Imam Hossein), all of which are affiliated with the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. The inclusion criteria were: (1) adults aged 15–60 years, (2) having a confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, (3) having a smartphone, and (4) having the ability to read and write. The exclusion criteria were: (1) participation in another educational program during the study, (2) deterioration of the patient’s physical and mental condition during the study, and (3) failure to attend two (or more) of the total number of follow-up sessions.

Sample size

Using the Pocak formula, and in accordance with Torki-Harchegani’s study31, a sample size calculation was performed, which incorporated a significance level of α = 0.05, a power of 90%, and a 10% attrition rate, yielding a final sample size of 60 participants (30 individuals in each group):

Randomization

Utilizing a convenience sampling method, participants were first recruited and subsequently divided into intervention groups and control groups via a randomized allocation process. The process of random assignment was carried out using a method involving sequentially numbered, sealed, and opaque envelopes; the preparation of these envelopes was facilitated by the use of the R statistical software. The preparation of the envelopes was carried out by a research assistant who remained completely uninvolved in all aspects of participant recruitment, thereby ensuring the integrity of the study. The intervention group, comprised of thirty participants, received training based on the FCEP in addition to standard care, while a control group, matched in size (thirty participants), received only the standard hospital training program. A research assistant, blinded to group assignment, administered a follow-up questionnaire to every participant six weeks after the initial study.

Measures

A multi-section questionnaire served as the data collection tool, and it encompassed the following sections:

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire included information about age, gender, educational level, marital status, occupation, Body Mass Index (BMI), Duration of disease, the last HbA1c, and family relationship with the caregiver.

Diabetes Self-Management questionnaire (DSMQ)

The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ), developed by Schmitt et al.32, is a 16-item scale instrument; seven of these items are formulated positively, and nine were inversely formulated with regard to what is considered effective self-care. The questionnaire allows the summation of the scores of four subscales including glucose management (GM; five items), dietary control (DC; four items), physical activity (PA; three items), health care use (HU; three items); finally, one item16 requests an overall rating of self-care, which is included in the sum scale. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which each statement applies to personal self-management with regard to previous 8 weeks in a 4-point Likert scale, with responses as ‘‘applies to me very much’’ (3 points), ‘‘applies to me to a considerable degree’’ (2 points), ‘‘applies to me to some degree’’ (1 point), and ‘‘does not apply to me’’ (0 point). Negatively worded items are reversed so that higher values are indicative of more effective self-care. The scores of the subscales were added as the sum score and then transformed to a scale ranging from 0 to 10. A transformed scale of 10 thus represented the highest self-rating of the assessed behavior. This instrument was translated into the Persian language. A panel of experts evaluated the validity of the instrument and clarity of translation. Reliability analysis revealed a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.846 for the sum scale. Cronbach α coefficients for subscales of DSMQ including GM, DC, PA, and HU were 0.59, 0.76, 0.77, and 0.63, respectively; this is comparable with the English version of DSMQ original scale, which revealed a Cronbach α coefficient of 0.84 for the sum scale, 0.77 for GM, 0.77 for DC, 0.76 for PA, and 0.6 for HU33. The current research validated the overall reliability of the questionnaire through the computation of its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, resulting in a value of 0.89.

Diabetes acceptance scale (DAS)

The Diabetes Acceptance Scale (DAS) was developed by Schmitt et al.34 and consists of twenty items, ten positive items (acceptance, integration, and identification, numbered 1 through 10) and ten negative items (non-acceptance, avoidance, and neglect, numbered 11 through 20). A four-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 0 (“never true for me”) to 3 (“always true for me”), is utilized in the questionnaire. The instrument’s total scale ranges from 0 to 60, with higher scores reflecting greater acceptance of diabetes, and scores of 30 or higher signifying high acceptance of the disease. Najafi Ghezeljeh et al.35 conducted an examination of the psychometric properties to determine the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the scale. To ensure its validity and reliability, the questionnaire underwent a series of rigorous testing and validation processes, which encompassed the establishment of face and content validity and the implementation of both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire, assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, demonstrated high reliability with scores of 0.96, 0.94, and 0.93 obtained for the Rational Dealing, Resentment, and Avoidance factors. The present study confirmed the reliability of the questionnaire by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which resulted in a value of 0.94.

Study procedure

After the caregivers provided informed written consent in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Human Research, they completed a pretest. Subsequently, after random allocation of samples to the intervention and control groups, the intervention group was invited to participate in an FCEP. The control group received only the usual care, which consisted of routine hospital education provided by nurses. The intervention program was underpinned by the four steps of the FCEP of Hsiu-Ying Yeh et al.‘s study36 that included: increased perceived threats, promotion of self-efficacy, promotion of self-belief, and evaluation. The FCEP consisted of eight sessions over a four-week period which each session lasting 40–60 min, and was presented by a research team (endocrinologist, psychiatric nurse, diabetes nurse specialist) during educational and support sessions through lectures, group discussions, and a question-and-answer period. The implementation of the model included four steps: The first step, perceived threat: In this step, through empowerment sessions, the patient’s perceived severity and sensitivity regarding the disease, its complications, and ways to control it increased. The goal of implementing this stage was to improve the level of knowledge and awareness of patients about the nature of the disease, the treatment process, and the importance of treatment follow-up. In this regard, patients became aware of their disease and its complications, which could help them with anxiety control and lead to an increase the attention to their disease status and the importance of treatment follow-up.

The second step, self-efficacy: In this step, skill acquisition and self-efficacy were achieved through group problem-solving. The purpose of choosing this method was to increase skill acquisition and self-efficacy, self-esteem, and self-control in patients. For this purpose, problem-solving sessions were held in 6–8-person groups for patients. The process of the sessions was based on the four stages of self-efficacy theory, including determining tasks, dividing complex behaviors into smaller and more understandable tasks in order for patients to be able to perform them, repeating the behavior with skill, and encouraging task performance for the patients. One of the important goals of this step was to increase the level of skills of the patients, so that during the sessions, topics such as methods of increasing skills in relation to their treatment needs, including methods of selecting and preparing appropriate nutrition, the need to comply with the drug regimen, how to comply with physical activity programs, and the importance of paraclinical monitoring were discussed. Also, in this stage, patients practically faced their problems and the problem-solving process, and under the indirect supervision of the researcher, they discussed and gave concrete examples of their own situation and what they would do to improve similar problems with others, thus participating in choosing solutions.

The third step, self-belief: This step included self-belief through educational participation. The goal of this step was for the patient to achieve self-efficacy in group sessions under the indirect guidance and supervision of the researcher and teach the topics discussed in that session to his active family member after completing each empowerment session. In addition to consolidating the patient’s knowledge by maintaining the patient’s dynamic role, this provided the necessary basis for self-belief and improved the patient’s skills. Concurrently, at these sessions, the researcher examined the patient’s learning and the feedback and learning rate of the patient’s active family member, and in cases such as the patient’s forgetfulness or the transmission of incorrect information, the information was immediately corrected by the researcher.

The fourth step, evaluation: This step included process evaluation and final evaluation. Process evaluation was conducted in such a way that at least two questions were asked about the previous sessions at the beginning of each session, and an evaluation was made based on the patients’ responses and the practical actions taken. The final evaluation was conducted six weeks after the intervention (Table 1). During the period until the final completion of the questionnaires, in order to maintain the relationship between the patient and the active family member with the researcher and to examine the process of empowerment quality, a 5–10-minute phone call was made every week, and while answering the patients’ questions, the process of changes was evaluated. Patients in the control group did not receive the FCEP; they received routine ward and clinic training, but in order to observe the ethical considerations of the research, after completing the intervention in the intervention group, all empowerment booklets, pamphlets, and training sheets for empowerment group classes were provided to them.

Statistical analysis

Following a pre-established analysis plan, all data analyses were performed utilizing SPSS statistical software version 16 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was utilized as the statistical method for the initial evaluation and measurement of the normality of the scores. The chi-square test was utilized for the comparison of the proportions. To compare two groups with respect to age, duration of disease, most recent HbA1c levels, and BMI, an Independent Samples T-test was employed as the statistical method. The effects of the intervention on the outcome variables were assessed using both Independent Samples T-tests and Repeated Measures ANOVAs, allowing for a detailed analysis of the differences between groups and within subjects over time. A significance level of 0.05 was established in this study.

Ethical considerations

The research ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences reviewed and approved the study protocol (No: IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1403.002). The Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials has officially registered this trial, assigning it the unique identifier IRCT20240624062246N1. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their involvement, and all data collected are maintained with strict confidentiality and anonymity to protect their privacy.

Results

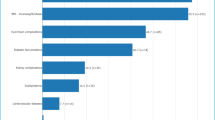

Based on the results of comparing demographic, patient, and family information, there was no significant difference in the two groups before the intervention. In total, 59 diabetic patients participated in our study, 29 in the intervention group (51.7% female) and 30 in the control group (63.3% female). The mean age of participants was 43.10 ± 11.44 years in the intervention group and 43.66 ± 11.21 years in the control group (Table 2). Also, 59 caregivers participated in our study, 29 in the intervention group (75.9% female) and 30 in the control group (73.3% female). The mean age of caregivers was 36.72 ± 11.41 years in the intervention group and 40.30 ± 10.08 years in the control group. Most of the caregivers in the intervention and control groups were female (75.9 vs. 73.3), married (75.9 vs. 83.4), and with a high school educational level (Table 3).

The results showed that at the baseline, there was no significant difference between the mean score of illness acceptance of patients in the intervention and control groups (P = 0.396). However, there was a significant difference between the mean score of illness acceptance between the two groups immediately (P = 0.008) and six weeks after the intervention (P < 0.001). Also, the results of the within-group comparison by the Friedman test showed that in the intervention group, the mean score of illness acceptance increased significantly from baseline to six weeks after the intervention (P < 0.001). However, in the control group, no significant difference was observed in the mean score of illness acceptance between these stages (P = 0.131) (Table 4).

The results of the Wilcoxon test for pairwise comparison between the different stages of the study showed that in the intervention group, there was a significant difference between the mean score of illness acceptance at the immediately after the intervention compare to the baseline (P < 0.001) and at six weeks after the intervention compare to the baseline (P < 0.001). Also, in the intervention group, a significant difference was observed between the mean score of illness acceptance at six weeks after the intervention compared to the immediately after the intervention (P < 0.001). However, in the control group, no significant difference was observed in the mean score of illness acceptance between the different stages of the study (P > 0.05) (Table 5). Figure 2 presents the variations in the mean score of illness acceptance between the different stages of the study.

The results showed that at the baseline, there was no significant difference between the mean score of self-management of patients in the intervention and control groups (P = 0.305). However, immediately and six weeks after the intervention, there was a significant difference between the mean score of self-management between the two groups (P < 0.001). Also, the results of the within-group comparison by the repeated measures ANOVA showed that in the intervention group the mean score of self-management increased significantly from the baseline to six weeks after the intervention (P < 0.001), while in the control group, no significant difference was observed in the mean score of self-management between these stages (P = 0.363) (Table 6). Figure 3 illustrates the variation in the mean score of self-management between different stages of the study.

According to the paired-sample t-tests, in the intervention group, there was a significant difference in the mean score of self-management between immediately after the intervention compare to the baseline (P < 0.001) and six weeks after the intervention compare to the baseline (P < 0.001), as well as between immediately and six weeks after the intervention (P < 0.001). However, in the control group, no significant difference was observed in the mean score of self-management between the different stages of the study (P > 0.05) (Table 7).

Discussion

The results of this research supported the initial hypothesis and indicated that at the baseline, there was no significant difference in the mean score of illness acceptance of patients in the intervention and the control groups. However, immediately and six weeks after the intervention, there was a significant difference in the mean score of illness acceptance of patients in the intervention and the control groups (between-group comparison). Moreover, in the intervention group, the mean score of illness acceptance increased significantly immediately and six weeks after the intervention compared to the baseline. However, in the control group, there was no significant difference in the mean score of illness acceptance of patients between the different stages of the study (within-group comparison). These findings were consistent with the results of other studies. For example, Cortez and collaborators in their study indicated the efficacy of an empowerment-based educational program on the ability to accept illness and self-care in diabetic patients37. Moazeni et al. also revealed that the FCEP can improve disease understanding, perceived stress, and self-care behaviors in husbands of diabetic patients38. Also, the study conducted by Rahimi Kordshooli showed that the FCEP was effective in illness perception in heart failure patients39. Another study found that a web-based empowerment program significantly improved acceptance of illness in adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus40. Rasheed Khazew et al. also in their study pointed out the significant effect of addressing the educational needs of diabetes patients on their illness acceptance level22. The findings of these studies were relevant to the current investigation and showed that the FCEP was effective in improving the illness acceptance of diabetic patients.

The confirmation of the second hypothesis was also achieved through the current study’s results, which demonstrated that at the baseline, there was no significant difference in the mean score of self-management of patients in the intervention and the control groups. However, immediately and six weeks after the intervention, there was a significant difference in the mean score of self-management of patients in the intervention and the control groups (between-group comparison). Moreover, in the intervention group, the mean score of self-management increased significantly immediately and six weeks after the intervention compared to the baseline. However, in the control group, there was no significant difference in the mean score of self-management of patients between the different stages of the study (within-group comparison). These findings were consistent with the results of other studies. For example, Mokhtari et al. in their study found that a family-centered intervention improved management and control of diabetes key indicators41. Another study conducted by Cheraghi et al. also demonstrated that family-centered care can improve the management behaviors of diabetic patients and their caregivers in the realms of “blood glucose testing”, “insulin therapy”, “meal plan”, and “physical activity”42. Teli et al. also argued that a family empowerment model had a positive impact in improving the family’s diet management ability, motivating the patient to do regular exercise, and use the health care facilities43. In this regard, another study reported the efficacy of a family empowerment therapy regarding self-care and management of glycosylated hemoglobin in diabetes patients44. Overall, the results of the present study were in line with previous studies and showed that a FCEP can improve illness acceptance and self-management in patients with type 2 diabetes. In light of the findings of this investigation, healthcare practitioners, including nurses, can effectively elevate the illness acceptance and self-management of patients with type 2 diabetes by employing the FCEP. However, further studies are needed in this area to compare the results across different demographic data and strengthen the generalizability of the study findings.

Study limitations

This study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of FCEP in improving illness acceptance and self-management in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, it is essential to acknowledge and address the study’s limitations. A particularly significant limitation lies in the study’s restricted sampling methodology, which substantially constrains its generalizability to a broader population. Future investigations would benefit considerably from implementing more comprehensive sampling approaches and larger sample sizes at the national level. The use of a convenience sampling method in this study was also a major limitation because it is associated with a significant risk of selection bias. It is recommended that future studies include other sampling methods. In addition, the follow-up period was relatively short, which limits the understanding of the long-term impact of FCEP on illness acceptance and self-management. Long-term follow-up studies are needed to evaluate the sustained effect of FCEP on illness acceptance and self-management. Future research should aim to address these limitations to further our understanding of the effects of FCEP on illness acceptance and self-management of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Conclusion

The findings from the present study indicated that the FCEP demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing both the acceptance of the illness and the self-management skills of diabetic patients. The findings of this study can be valuable for nurses working in hospitals and home care environments, as they can utilize FCEP as a straightforward intervention to enhance treatment outcomes and mitigate disease complications in diabetic patients.

Data availability

If requested, the corresponding authors will make the datasets used and analyzed in the current study available for access.

References

Abolfathi, M. et al. Evaluation of quality of life in diabetic pregnant women. Prim. Care Diabetes. 16 (1), 84–88 (2022).

Jiao, F. et al. Effectiveness of the multidisciplinary risk assessment and management program for patients with diabetes mellitus (RAMP-DM) for diabetic microvascular complications: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Metab. 42 (6), 424–432 (2016).

Esteghamati, A. et al. Diabetes in iran: prospective analysis from first nationwide diabetes report of National program for prevention and control of diabetes (NPPCD-2016). Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 13461 (2017).

Forouzanfar, M. H. et al. Global, regional, and National comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 386 (10010), 2287–2323 (2015).

Zokaei, A. et al. Investigating high blood pressure, type-2 diabetes, dislipidemia, and body mass index to determine the health status of people over 30 years. J. Educ. Health Promotion. 9 (1), 333 (2020).

Karlsen, B., Oftedal, B. & Bru, E. The relationship between clinical indicators, coping styles, perceived support and diabetes-related distress among adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Adv. Nurs. 68 (2), 391–401 (2012).

Polonsky, W. H. et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 28 (3), 626–631 (2005).

Fisher, L., Glasgow, R. E. & Strycker, L. A. The relationship between diabetes distress and clinical depression with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 33 (5), 1034–1036 (2010).

Papelbaum, M. et al. The association between quality of life, depressive symptoms and glycemic control in a group of type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 89 (3), 227–230 (2010).

Kıtış, Y. & Emıroğlu, O. N. The effects of home monitoring by public health nurse on individuals’ diabetes control. Appl. Nurs. Res. 19 (3), 134–143 (2006).

Arvidsson, S. B. et al. A nurse-led rheumatology clinic’s impact on empowering patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Nurs. Health Sci. 8 (3), 133–139 (2006).

Shiu, A. T. Y., Wong, R. Y. M. & Thompson, D. R. Development of a reliable and valid Chinese version of the diabetes empowerment scale. Diabetes Care. 26 (10), 2817–2821 (2003).

Osborn, C. Y. & Fisher, J. D. Diabetes education: integrating theory, cultural considerations, and individually tailored content. Clin. Diabetes. 26 (4), 148–151 (2008).

Borimnejad, L., Parvizy, S., Haghaani, H. & Sheibani, B. The effect of family-centered empowerment program on self-efficacy of adolescents with thalassemia major: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery. 6 (1), 29 (2018).

Mohammad Mousaei, F., Zendehtalb, H. R., Zare, M. & Behnam Vashani, H. R. Effect of family-centered empowerment model on self-care behaviors of patients with multiple sclerosis. Evid. Based Care. 11 (3), 35–43 (2021).

Barlow, J. How to use education as an intervention in osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 15 (4), 545–558 (2001).

Taylor, S. J. C. et al. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions (PRISMS practical systematic review of Self-Management support for long-term conditions). Health Social Care Delivery Res. 2 (53), 1–580 (2014).

American Diabetes, A. Joint statement outlines guidance on diabetes self-management education, Support. (2015).

Maina, P. M., Pienaar, M. & Reid, M. Self-management practices for preventing complications of type II diabetes mellitus in low and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 5, 100136 (2023).

Al Hayek, A. A. et al. Impact of an education program on patient anxiety, depression, glycemic control, and adherence to self-care and medication in type 2 diabetes. J. Family Community Med. 20 (2), 77–82 (2013).

Kim, E. H., Cui, L. N. & Nho, C. R. A longitudinal study on the stability and causal relationships between disability acceptance, self-efficacy, and interpersonal ability among Koreans with disability. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 16 (3), 290–305 (2022).

Khazew, H. R. & Faraj, R. K. Illness acceptance and its relationship to health-behaviors among patients with type 2 diabetes: a mediating role of self-hardiness. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. :102606. (2024).

Jankowiak, B., Kowalewska, B., Krajewska-Kułak, E., Milewski, R. & Turosz, M. A. Illness acceptance as the measure of the quality of life in moderate psoriasis. Clin. Cosmet. Invest. Dermatology :1139–1147. (2021).

Saeed, S. M. & Al-Jubouri, M. B. Perceptions of nursing students’ regarding coronavirus vaccination acceptance: A mixed methods study. Res. Militaris. 12 (2), 6570–6579 (2022).

Bamari, F., Madarshahian, F. & Barzgar, B. Reviews burden of caring caregivers of patients with type II diabetes referred to diabetes clinic in the City of Zabol. J. Diabetes Nurs. 4 (2), 59–67 (2016).

Vega-Silva, E. L., Barrón-Ortiz, J., Aguilar-Mercado, V. V., Salas-Partida, R. E. & Moreno-Tamayo, K. Quality of life and caregiver burden in caregivers with patients with complications from type 2 diabetes mellitus. Revista Med. Del. Instituto Mexicano Del. Seguro Social. 61 (4), 440–448 (2023).

Alanazi, M., Bajmal, E., Aseeri, A. & Alsulami, G. Empowering adult patients with diabetes for health educators’ role within their family members: A cross-sectional study. Plos One. 19 (4), e0299790 (2024).

de Lima Santos, A. & Silva Marcon, S. How people with diabetes evaluate participation of their family in their health care. Investigación Y Educación En Enfermería. 32 (2), 260–269 (2014).

World Medical, A. World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 310 (20), 2191–2194 (2013).

Jayaraman, J. Guidelines for reporting randomized controlled trials in paediatric dentistry based on the CONSORT statement. Int. J. Pediatr. Dent. 31, 38–55 (2020).

Torki-Harchegani, F., Shirazi, M., Keshvari, M. & Abazari, P. The effect of home visit program on self-management behaviors and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin. J. Isfahan Med. School. 38 (575), 310–316 (2020).

Schmitt, A. et al. The diabetes Self-Management questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 11, 1–14 (2013).

Nasab, M. N., Ghavam, A., Yazdanpanah, A., Jahangir, F. & Shokrpour, N. Effects of self-management education through telephone follow-up in diabetic patients. Health Care Manag. 36 (3), 273–281 (2017).

Schmitt, A. et al. Measurement of psychological adjustment to diabetes with the diabetes acceptance scale. J. Diabetes Complicat. 32 (4), 384–392 (2018).

Najafi Ghezeljeh, T. et al. Psychometric evaluation of Persian version of diabetes acceptance scale (DAS). BMC Endocr. Disorders. 22 (1), 225 (2022).

Yeh, H-Y., Ma, W-F., Huang, J-L., Hsueh, K-C. & Chiang, L-C. Evaluating the effectiveness of a family empowerment program on family function and pulmonary function of children with asthma: A randomized control trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 60, 133–144 (2016).

Cortez, D. N. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of an empowerment program for self-care in type 2 diabetes: a cluster randomized trial. BMC Public. Health. 17, 1–10 (2017).

Moazeni, M., Aliakbari, F., Kheiri, S. & Tali, S. S. The Effect of Family-Centered Empowerment Program on Husbands’ Understanding of Illness, Perceived Stress and Self-care Behaviors of Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Jundishapur J. Chronic Disease Care 13(4) (2024).

Kordshooli, K. R., Rakhshan, M. & Ghanbari, A. The effect of family-centered empowerment model on the illness perception in heart failure patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Caring Sci. 7 (4), 189 (2018).

Scalzi, L. V., Hollenbeak, C. S., Mascuilli, E. & Olsen, N. Improvement of medication adherence in adolescents and young adults with SLE using web-based education with and without a social media intervention, a pilot study. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 16, 1–10 (2018).

Mokhtari, Z., Mokhtari, S., Afrasiabifar, A. & Hosseini, N. The effect of Family-Centered intervention on key indicators of diabetes management and control in patients with Type-2 diabetes. Int. J. Prev. Med. ;14(1). (2023).

Cheraghi, F., Shamsaei, F., Mortazavi, S. Z. & Moghimbeigi, A. The effect of family-centered care on management of blood glucose levels in adolescents with diabetes. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery. 3 (3), 177 (2015).

Teli, M. Family empowerment model for type 2 DM management: integration of self care model by Orem and family centered nursing by Friedman in Sikumana health Center-Kupang. Jurnal Info Kesehatan. 17 (1), 75–87 (2019).

Rahmani, Mansoobifar, M., Sirifi, M. R., Ashayeri, H. & Bermas, H. Effectiveness of family empowerment therapy based on Self-Compassion on Self-Care and glycosylated hemoglobin in female patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Women’s Health Bull. 7 (2), 33–42 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The content of this article originates from a nursing master’s thesis that received approval from the Research and Ethics Committee at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. We extend our sincere gratitude to the Dean of Nursing School, nursing students, and the Honorable Research Vice President of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their indispensable support in facilitating this study.

Funding

Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences provided financial support for this research, which encompassed all aspects of the study, from the initial design to the analysis, interpretation, and final article preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design of the study: N.A., F.B., N.S.; data collection: N.A.; analysis and interpretation of data: A.A., N.S., A.M.N.; manuscript preparation: N.A., A.M.N., F.B.; manuscript revision: N.A., A.M.N., F.B. The final manuscript underwent a thorough review and confirmation process by each of the authors prior to its submission. The final manuscript has been read and approved by the author(s).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The purpose of the study was explained to the participants, and their privacy and confidentiality were assured. In this study, they have been informed that it is voluntary, and they can withdraw at any time. Before participating in the study, they signed a consent form. In addition, the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences’ Review Board approved the study (No: IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1403.002).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amani, N., Nazari, A.M., Sanaie, N. et al. Effects of family-centered empowerment program on illness acceptance and self-management of patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 21615 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05833-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05833-0