Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a leading cause of cancer-related death, with limited treatment options and high recurrence rates. Prognostic biomarkers and predictors of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) response are urgently needed. This study aimed to develop a macrophage-related gene signature to predict patient outcomes and ICI efficacy, with a focus on the functional role of PLAUR. Single-cell RNA sequencing of paired HCC and normal liver tissues was used to identify macrophage subtypes. A prognostic gene signature was constructed based on macrophage-related genes and validated using the TCGA-LIHC cohort. TIDE analysis was performed to assess ICI response prediction. PLAUR-related cell communication was evaluated using CellChat. Functional assays were conducted to assess the effect of PLAUR knockdown on macrophage polarization, tumor cell behavior, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activity. Tissue microarray immunofluorescence validated PLAUR expression in situ. An eight-gene macrophage-related signature showed strong prognostic and predictive value. High-risk patients had poorer survival and reduced ICI responsiveness. PLAUR was overexpressed in tumor-associated macrophages and correlated with enhanced cell communication in tumors. Knockdown of PLAUR inhibited M2 polarization, reduced tumor cell proliferation and migration, and suppressed PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. In vivo, PLAUR silencing significantly reduced tumor growth in a THP-1/SKHep1 co-injection model. We identified a novel macrophage-related gene signature with clinical utility in HCC. PLAUR promotes immunosuppressive polarization and tumor progression via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, representing a potential therapeutic target and biomarker for immunotherapy response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy and constitutes a major global health problem, representing the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1. Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of HCC, the prognosis remains poor, with a high rate of recurrence and limited therapeutic options for advanced-stage disease2,3. The complexity of HCC is further compounded by its etiological diversity, which includes viral hepatitis, alcohol consumption, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and exposure to aflatoxins4,5.

The cellular and molecular heterogeneity of HCC is a significant barrier to effective treatment. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), as a key component of the tumor microenvironment, have been shown to play a substantial role in cancer progression and therapeutic resistance by fostering a pro-tumorigenic environment through their interactions with cancer cells and other stromal cells6,7. TAMs can be re-educated by the tumor microenvironment to adopt an immunosuppressive phenotype, which in turn supports cancer growth, metastasis, and evasion from immune surveillance8,9.

In the era of precision medicine, the utilization of single-cell sequencing has provided unprecedented resolution in deciphering the cellular composition and gene expression profiles within the tumor microenvironment of HCC, offering novel insights into the intercellular crosstalk and potential therapeutic targets10. Such high-resolution profiling of individual cells can lead to the identification of key regulators within complex cellular networks11.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD1/PDL1 have revolutionized the treatment landscape for several malignancies. However, the response rate in HCC remains modest, highlighting the need for predictive biomarkers to identify patients most likely to benefit from ICIs12. Furthermore, the complexity of the tumor-immune interface underscores the necessity of understanding the microenvironmental factors that influence the efficacy of immunotherapy13.

Given the therapeutic significance of macrophages in HCC and the potential for modulating the PD1/PDL1 axis, our study aimed to construct a macrophage-related prognostic signature that could serve as a predictor for both patient outcomes and responses to ICIs. The characterization of cell-to-cell communication networks, especially those involving macrophages, is crucial for understanding their contribution to tumor immunity and designing more effective immunotherapeutic interventions. Additionally, by confirming our findings using tissue microarray immunofluorescence, we seek to bridge the gap between in silico discoveries and their clinical relevance.

Therefore, this study aimed to construct a comprehensive single-cell atlas of hepatocellular carcinoma and adjacent normal liver tissues, identify macrophage-related prognostic genes associated with immunotherapy response, and functionally validate key regulators such as PLAUR. Our goal is to improve patient stratification and provide potential therapeutic targets for immunomodulatory treatment in HCC.

Methods

Single-cell analysis

Single-cell sequencing data of paired hepatocellular carcinoma tissue and normal liver tissue were obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; ID: GSE149614), including data from 10 liver cancer tissues and 10 normal liver tissues14. The retrieved expression matrix was used to create a Seurat object, which was then matched with the acquired metadata. The data uploader has provided complete cell annotation information and has cleaned and filtered the data, so there is no need for cell annotation or further data cleaning and filtering.

The subset function was used to extract a subset Seurat object from the Seurat object. The NormalizeData function was used to normalize the subset Seurat object. The FindVariableFeatures function was used to calculate highly variable genes. The RunUMAP function was applied to perform dimensionality reduction on the subset Seurat object, with a resolution of 0.4. The CellMarker database (http://xteam.xbio.top/CellMarker/ ) was used for manual annotation of cells15. Cells with similar expression patterns were classified into the same subgroup by calculating the average gene expression of each cell and using Spearman’s correlation analysis. The R package ‘Seurat’ was used to perform the above analysis16.

Survival analysis

We conducted an analysis using the LIHC data from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ ). After data cleaning and filtering, we obtained an expression matrix composed of 355 liver cancer patients and their corresponding clinical data. Patients were divided into groups with high and low expression based on the median value of gene expression. The R package ‘survival’ was used to perform the survival analysis17. The Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis was utilized to determine survival differences, and a P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Construction of a prognosis-related signature

We used macrophage-related genes screened by single-cell sequencing to construct a prognosis-related signature. The LIHC expression matrix was used to explore the correlation between macrophage-related genes and PDCD1 as well as CD274. An absolute value of the correlation coefficient greater than 0.3 was considered to indicate a correlation between two genes. PDCD1 and CD274 are the gene names for PD1 and PDL1, respectively. Therefore, the final selection of genes used to construct the prognosis-related signature was associated with macrophages and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). The R package ‘survival’ was utilized for univariate Cox analysis and multivariate Cox analysis. KM analysis was employed to determine survival differences, with a P-value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. After univariate and multivariate Cox analyses, the selected genes comprised the prognosis-related signature. The following formula was used to calculate the risk score:

The expression level of each RNA was denoted as exp (RNAi), and the multivariate Cox regression coefficient for each RNA was denoted as coef (RNAi). The R package ‘survivalROC’ was used to assess the accuracy of prognosis -related signature18. The R package ‘ggplot2’ was used for data visualization.

ICI efficacy assessment

The Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/login/ ) was used to evaluate the therapeutic effect of ICIs19. All patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median of their risk scores. Subsequently, the expression matrix was uploaded to the TIDE database to obtain respond data for ICI treatments. Patients with a higher TIDE value were less likely to respond to ICI therapy. The R package ggplot2 was used for data visualization.

Cell communication analysis

Based on the expression level of PLAUR, we classified all macrophages into PLAUR-positive macrophages and PLAUR-negative macrophages. A Seurat object was used to construct a CellChat object. After loading the human receptor-ligand pair database into the CellChat object, an intercellular interaction network was established based on the existing receptor-ligand pair information. The R package CellChat was used to carry out cell communication analysis, and the analysis was carried out according to the standard protocol document20.

Immunohistochemical staining of tissue

Tissue samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned consecutively at a thickness of 4 μm. The sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series to distilled water. Antigen retrieval was performed in sodium citrate buffer. To block endogenous peroxidase activity, sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide, followed by blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) to reduce nonspecific antibody binding. The sections were then incubated overnight at 4℃ with specific primary antibodies, including anti-PLAUR (Abcam, Cat# ab221680) and anti-CD163 (Abcam, Cat# ab156769). On the following day, the sections were sequentially incubated with secondary antibodies and an avidin–biotin complex (ABC). Immunoreactivity was visualized using a diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate, and nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. After dehydration and clearing, the sections were mounted and evaluated under a microscope. Two experienced pathologists independently reviewed and scored the slides in a blinded manner. The tissue microarray (TMA) used in this study was purchased from Superchip Biotech Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China) and consisted of 40 pairs of tumor tissues and matched adjacent non-tumorous control samples.

Tissue microarray Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on tissue microarrays according to the standardized protocol provided by the manufacturer. Tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies, followed by secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Abcam, ab150113) and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (Abcam, ab150080). After secondary antibody incubation, cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The stained tissue microarrays were subsequently imaged using a confocal laser scanning microscope (ZEISS LSM 980).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from tissue samples using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-PLAUR (Abcam, ab221680), anti-β-Actin (Proteintech, 20536-1-AP), anti-PI3K (Proteintech, 20584-1-AP), anti-AKT (Proteintech, 10176-2-AP), anti-Phospho-AKT (Ser473) (Proteintech, 66444-1-Ig), and anti-mTOR (Proteintech, 66888-1-Ig). The following day, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (Proteintech, SA00001-2) and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (Proteintech, SA00001-1). Signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and visualized with a gel imaging system. Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ software to assess protein expression levels.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extraction involved phase separation with chloroform, precipitation with isopropanol, and washing with 75% ethanol. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from the extracted RNA using a reverse transcription kit (Servicebio, China). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a SYBR Green qPCR kit (Servicebio, China) on a real-time PCR system with gene-specific primers. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method, normalized to the internal control gene ACTB. All reactions were conducted in triplicate. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and differences between groups were analyzed using a two-tailed t-test. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The primer sequences used were as Supplementary Table 1.

THP-1 macrophage differentiation and polarization

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was purchased from Servicebio (Wuhan, China) and maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. To induce macrophage differentiation, THP-1 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL and treated with 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were washed with PBS and cultured in PMA-free complete medium for an additional 24 h to allow for full differentiation into resting macrophages. Polarization was achieved by stimulating differentiated macrophages with 20 ng/mL interleukin-4 (IL-4) and 20 ng/mL interleukin-13 (IL-13) for M2 polarization. Flow cytometry was used to assess the proportion of M1 and M2 polarized cells. Cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-MHC Class II antibody (Abcam, ab25430) for M1 markers, and FITC-conjugated anti-Mannose Receptor antibody (Abcam, ab270647) for M2 markers, following the manufacturer’s protocols. Data were acquired using a flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to evaluate the expression levels of polarization-related genes, including CD163, IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-12.

In vivo xenograft model with THP-1/SKHep1 co-injection

To investigate the effects of macrophage–tumor cell interactions on tumor growth in vivo, a subcutaneous xenograft model was established using a co-injection of human hepatocellular carcinoma SKHep1 cells and differentiated THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were pretreated with 100 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 h to induce macrophage-like differentiation, followed by a 24-hour rest period in PMA-free medium prior to collection. SKHep1 and differentiated THP-1 cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio (5 × 10⁶ cells each) in 100 µL of serum-free RPMI-1640 medium and injected subcutaneously into the right flank of 4–6-week-old male BALB/c nude mice (Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). At the end of the 4th week, mice were euthanized, and tumors were excised, weighed, and subjected to subsequent histological and molecular analyses. All animal procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuyang People’s Hospital and were conducted in accordance with institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Results

Hepatocellular carcinoma single-cell atlas

A total of 49,558 cells were categorized into 6 different cell types, namely T or NK cells, myeloid cells, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, and B cells (Fig. 1A). After UMAP dimensionality reduction, it can be observed that the distribution of hepatocytes was rather scattered. This may be due to significant biological differences between tumor-derived hepatocytes, that is, liver cancer cells, and normal hepatocytes. All cells were derived from either tumor tissues or normal liver tissues (Fig. 1B). Cells originating from tumor tissues and those from normal tissues exhibited considerable heterogeneity, and the distribution of cells did not converge together. Tumor and normal liver tissues from 10 liver cancer patients were used for single-cell sequencing (Fig. 1C and D). The individual differences amongst humans may also contribute to the observed heterogeneity. Representative marker genes of each cell type were displayed in Fig. 1E.

Single-cell panorama of hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) the distribution of all cells, with points of different colors representing different cell types. (B) the distribution of all cells, with points of different colors representing different tissue origins. (C) the distribution of all cells, with points of different colors representing different sample origins. (D) the distribution of all cells, with points of different colors representing different sample and tissue origins. (E) the expression of marker genes for different cell types, where blue points indicate low expression levels, red points indicate high expression levels, and the size of the point represents the percentage of cells expressing the gene out of all cells.

Single-cell panorama of macrophages

A total of 9,528 myeloid cells were divided into 10 subclusters (Fig. 2A). Leukocytes derived from bone marrow can generally be categorized at the single-cell level into macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, and mast cells. Based on the marker genes of the 10 subclusters, the myeloid cells were annotated as three main cell types, namely, macrophages, DCs, and monocytes (Fig. 2B). The marker genes for macrophages, DCs, and monocytes were shown in Fig. 2C. Due to the limitations of single-cell sequencing technology, it’s challenging to completely differentiate myeloid cells. Therefore, the distinctiveness of the marker genes for these three types of cells was not very high. Myeloid cells from tumor tissues exhibit considerable heterogeneity compared to those from normal tissues (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the impact of the tumor microenvironment on immune cells may be a critical factor affecting tumor therapy efficacy. A total of 2,128 macrophages were divided into five subclusters (Fig. 2E). Almost all macrophages originated from tumor tissue (Fig. 2F). Based on the similarity of expressed genes, all macrophages could be divided into three subtypes with different expression patterns (Fig. 2G and H). These three subtypes of macrophages, with different expression patterns, have distinct marker genes that were specific to macrophages and were closely related to the function of macrophages. The MAC1 subtype of macrophages has a total of 316 marker genes, the MAC2 subtype of macrophages has 268 marker genes, and the MAC3 subtype has 286 marker genes. In total, 870 macrophage-related genes were obtained for subsequent analysis.

Single-cell panoramic view of macrophages. (A) Dots of different colors represent cell clusters. (B) Dots of different colors represent different cell types. (C) Expression levels of the cell’s marker genes, with red indicating high expression and grey indicating low expression. (D) Dots of different colors represent different tissue origins. (E) Dots of different colors indicate clusters of macrophages. (F) Dots of different colors represent different tissue origins. (G) Heat map showing the correlation among different clusters of macrophages, with red indicating a high correlation coefficient and blue indicating a low correlation coefficient. (H) Dots of different colors represent subtypes of macrophages.

Constructing a prognostic signature related to macrophages and ICIs

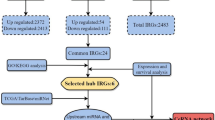

Figure 3A showed the strategy for screening the signature. A total of 870 macrophage-related genes were used for correlation analysis with PDCD1 and CD274, from which 160 ICI-related genes were screened. Univariate Cox analysis and multivariate Cox analysis were used to test the prognostic value of the 160 genes. Eventually, 8 genes with prognostic value related to macrophages and ICI were selected as the signature. ATP1B3, CAPZB, CTSC, DNAJB4, PHLDA2, PLAUR, PPT1, and TUBA1C all have good prognostic values (Fig. 3B–I).

Survival analysis. (A) The process of filtering for macrophage and ICI-related prognostic signatures. (B) Survival curve for ATP1B3. (C) Survival curve for CAPZB. (D) Survival curve for CTSC. (E) Survival curve for DNAJB4. (F) Survival curve for PHLDA2. (G) Survival curve for PLAUR. (H) Survival curve for PPT1. (I) Survival curve for TUBA1C.

Effect assessment of the prognostic signature

Patients in the high-risk group had a higher expression of prognosis-related genes compared to those in the low-risk group (Fig. 4A). This indicated that prognosis-related genes played a key role in the progression of the tumor. Furthermore, with an increase in the risk score, the mortality rate of patients also increased (Fig. 4B and C), suggesting that the prognostic signature had good predictive performance. The survival rate of patients in the high-risk group was significantly lower than that of the patients in the low-risk group (Fig. 4D), which further demonstrates the good predictive effect of the prognostic signature. Compared to other clinical evaluation indicators, the prognostic signature has a higher AUC (Fig. 4E). The univariate Cox analysis showed that clinical staging, TNM, and the prognostic signature were independent risk factors (Fig. 4F). However, the multivariate Cox analysis indicated that only the prognostic signature was an independent risk factor (Fig. 4G). In summary, the prognostic signature had a great ability to predict the prognosis of patients. In addition, we employed the liver cancer dataset GSE14520 from the GEO database, which comprises 242 hepatocellular carcinoma patients in an external validation cohort. The risk model maintained strong prognostic performance upon external validation, underscoring its potential clinical applicability(Fig. 5A–D).

Assessment of the predictive effect of the prognostic signature. (A) Heatmap shows the expression differences of eight prognosis-related genes between patients in the high-risk group and those in the low-risk group. Red indicates high expression levels, and green indicates low expression levels. (B) Scatter plot shows that the mortality rate of patients increases with higher risk. (C) Risk curve displays the distribution characteristics of the risk scores. (D) Survival curve for the risk scores calculated by the prognostic signature. (E) The ROC curve of the risk score and clinical relevant features. (F) Forest plot shows the results of the univariate Cox analysis. (G) forest plot shows the results of the multivariate Cox analysis.

Assessment of the ICI treatment effect based on the prognostic signature. (A) scatter plot shows that the mortality rate of patients increases with higher risk in GSE14520. (B) risk curve displays the distribution characteristics of the risk scores in GSE14520. (C) survival curve for the risk scores calculated by the prognostic signature in GSE14520. (D) The ROC curve of the risk score and clinical relevant features in GSE14520. (E) Distribution of TIDE scores, with each vertical bar representing a patient; red indicates patients who responded to ICI treatment, while blue indicates patients who did not respond to ICI treatment. (F) Violin plot of the TIDE scores. (G) Violin plot for exclusion. (H) Violin plot for MSI. **** means P < 0.0001.

Assessment of ICI treatment efficacy based on prognostic signature

Patients who responded to ICI treatment were primarily comprised of those with a low risk, while the non-responders chiefly consisted of high-risk individuals (Fig. 5E). This indicated that high-risk patients had a harder time benefiting from ICI therapy, whereas it was easier for low-risk patients to derive benefit. High-risk patients had significantly higher TIDE scores than those in the low-risk group (Fig. 5F), suggesting that high-risk patients were less likely to generate an effective response to ICI drugs. The exclusion scores of high-risk patients were notably higher than those of low-risk patients (Fig. 5G), implying that immune escape of tumor cells was more likely to occur in the high-risk group. Patients in the high-risk group also had substantially higher microsatellite instability scores (MSI) compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 5H), indicating that high-risk patients had a heavier mutation burden. Therefore, identifying high-risk patients through the prognostic signature and developing relevant targeted drugs to decrease the risk for these patients and enhancing the efficacy of ICI treatment were key to improving the cure rate of liver cancer.

Expression pattern of prognostic signature

Macrophages derived from tumor tissue are known as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). CAPZB, PHLDA2, PLAUR, and TUBA1C all showed increased expression levels in TAMs, while the other four genes were upregulated in macrophages derived from normal tissue (Fig. 6A). However, PLAUR and PPT1 were mainly overexpressed in myeloid cells (Fig. 6B–D). This suggests that PLAUR and PPT1 may played a key role in the function of myeloid cells. At the holistic level, ATP1B3, PHLDA2, and TUBA1C showed increased expression in tumor tissues (Fig. 6E–G), with no significant statistical differences in the expression of the other five genes(Fig. 6H–L). This indicates that these three genes may play an important role in the progression of cancer.

Expression pattern of the prognostic signature. (A) Expression distribution of the prognostic signature in normal tissue macrophages and TAMs, where blue dots represent high expression levels, and gray dots represent low expression levels. (B) Expression distribution of PLAUR across all cells. (C) Expression distribution of the prognostic signature across all cells, with red dots indicating high expression levels, and blue dots indicating low expression levels. (D) Expression distribution of PPT1 across all cells. (E) Box plot for ATP1B3. (F) Box plot for CAPZB. (G) Box plot for CTSC. (H) Box plot for DNAJB4. (I) Box plot for PHLDA2. (J) Box plot for PLAUR. (K) Box plot for PPT1. (L) Box plot for TUBA1C. * means P < 0.05.

Cell communication analysis and clinical sample validation

PLAUR and PPT1 were both expressed in myeloid cells, but PLAUR was mainly overexpressed in TAMs. Therefore, PLAUR may played a more important role. All macrophages were classified based on the expression level of PLAUR into PLAUR-positive macrophages and PLAUR-negative macrophages, and their communication strength with other cells was calculated. Cells originating from tumor tissue exhibited a stronger communication strength than those from normal tissue (Fig. 7A). This suggests that the microenvironmental activity in the tumor-derived tissues was more dynamic. The communication strength between PLAUR-positive macrophages in tumor tissue and other cells was stronger than that between PLAUR-positive macrophages in normal tissue and other cells (Fig. 7B). Similarly, PLAUR-positive macrophages in tumor tissue have more communication pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1A). This implies that PLAUR can increase the frequency of cell interactions in macrophages. PLAUR-positive macrophages can secrete ligands such as TNF and MDK that act on tumor cells, thereby enhancing the proliferation and migration capabilities of the tumor cells21,22. They can also secrete MIF that acts on T cells or NK cells, modulating the tumor immune microenvironment (Supplementary Fig. 1B)23,24,25. This demonstrated the significant role of PLAUR in macrophages. Immunohistochemical staining using microarray chips confirmed the high expression of PLUAR in HCC tumor tissues (Fig. 7C and D). Finally, we used immunofluorescence to confirm the expression levels of PLAUR, finding that PLAUR was overexpressed in the macrophages of tumor tissues (Fig. 7E).

Analysis of cell communication and immunohistochemistry validation. (A) The intensity of cell communication in tumor tissue is higher than that in normal tissue. (B) The intensity of communication between cells in tumor tissue and in normal tissue. (C) Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of PLAUR expression in a tissue microarray containing normal (N) and tumor (T) samples from HCC patients. (D) H-Score quantification of PLUAR expression demonstrates significant upregulation in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues. (E) representative immunofluorescence images of PLAUR expression in macrophages in tumor and normal tissues.

PLAUR regulates macrophage polarization and promotes tumor progression through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

To investigate the role of PLAUR in macrophage function and tumor progression, we first constructed PLAUR-knockdown THP-1 cells via lentiviral transduction. RT-qPCR and Western blot confirmed effective downregulation of PLAUR at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 8A–B). Following macrophage differentiation, flow cytometry analysis showed that PLAUR silencing resulted in a decrease in M2-type macrophages (CD206⁺) and an increase in M1-type macrophages (MHC class II⁺) (Fig. 8C). After co-culturing macrophages with SKHep1 cells, CCK-8 assay revealed that PLAUR knockdown significantly inhibited the proliferative capacity of SKHep1 cells (Fig. 8D). This was further validated at the molecular level: RT-qPCR analysis showed downregulation of M2 markers (IL-10, Arg1) and upregulation of M1 markers (TNF-α, IL-12) in the PLAUR-knockdown group (Fig. 8E).

Functional analysis of PLAUR knockdown in THP-1 cells and its impact on tumor progression. (A) PLAUR mRNA expression in THP-1 cells after lentiviral knockdown, detected by qRT-PCR. (B) PLAUR protein expression detected by Western blot. (C) Proportions of M1 and M2 macrophages detected by flow cytometry following polarization. (D) SKHep1 cells proliferation curve after co-culture with PLAUR-knockdown macrophages.THP-1 cell proliferation curve after PLAUR knockdown. (E) Expression of macrophage polarization markers (TNF-α, IL-12, IL-10, CD163) detected by qRT-PCR. (F) Migration ability of SKHep1 cells co-cultured with polarized THP-1 cells. (G) Expression of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway proteins in THP-1 cells. (H) Representative images of subcutaneous tumors formed by co-injection of THP-1 and SKHep1 cells in nude mice. (I) Tumor volume growth curves over 4 weeks. (J) Final tumor weights of xenografts at endpoint.

To assess the impact of macrophage PLAUR expression on tumor cell behavior, we conducted a co-culture experiment in which polarized THP-1 macrophages were cultured with SKHep1 cells. Notably, SKHep1 cells co-cultured with PLAUR-knockdown THP-1 cells exhibited significantly reduced migratory ability compared with the control group (Fig. 8F). Mechanistically, Western blot analysis revealed that PLAUR knockdown suppressed the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, as indicated by decreased expression levels of PI3K, phospho-AKT, and mTOR (Fig. 8G), suggesting that PLAUR may exert its function via this axis. To further validate the in vivo relevance of PLAUR, a subcutaneous xenograft model was established by co-injecting SKHep1 cells with THP-1 macrophages. Mice injected with PLAUR-knockdown THP-1 cells developed significantly smaller tumors compared to the control group (Fig. 8H). Tumor growth curves and final tumor weights further confirmed the inhibitory effect of PLAUR silencing on tumor progression (Fig. 8I, K). Collectively, these findings indicate that PLAUR promotes M2 polarization of macrophages, enhances tumor cell migration, and facilitates tumor growth through activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

Discussion

The comprehensive analysis presented in the results section offers novel insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying HCC, and the constructed prognosis-related signature provides a valuable tool for predicting patient outcomes and guiding treatment strategies, particularly for ICI therapies. Here, we discuss the potential implications of our findings within the broader context of HCC research and treatment.

The Single-cell Analysis of HCC tissues revealed distinct cellular landscapes between tumor-derived and normal hepatocytes, highlighting the significant heterogeneity inherent to HCC. This observation is aligned with current understandings of tumor biology, where intratumoral heterogeneity poses a major challenge for effective cancer treatment due to its role in therapeutic resistance and cancer progression26,27. Interestingly, our study uncovered subtypes of macrophages with different expression profiles within the HCC microenvironment, which could be indicative of the diverse functions and polarization states of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). The existence of these subtypes reinforces the concept that the tumor microenvironment influences immune cell phenotype and function, a consideration that is critical when evaluating immunotherapeutic approaches28,29.

The prognostic signature, derived from macrophage-related genes and their relationship with ICIs such as PDCD1 and CD274, holds significant promise for the stratification of patients into risk categories and improving the selection of candidates for ICI therapy. In clinical practice, predicting which patients are likely to benefit from ICIs remains a challenge, and our signature potentially addresses this gap30. It is interesting to note that the identified macrophage-related genes showed prognostic value, suggesting that TAMs play a crucial role in HCC progression and patient outcomes, corroborating with other studies associating TAMs with poor prognosis in various cancers31,32.

However, our study also indicated that patients classified as high-risk according to our signature exhibited reduced responsiveness to ICIs, as reflected by higher TIDE scores. This could point to an increased likelihood of immune evasion in these patients, which is an ongoing challenge in immuno-oncology. The correlations between the risk score, MSI levels, and exclusion scores suggest that a high-risk status is associated with a higher mutation burden and potential immune escape mechanisms33.

ICell–cell communication analysis further highlighted the role of PLAUR-positive macrophages in facilitating intercellular signaling within the tumor microenvironment, potentially promoting tumor progression by enhancing tumor cell proliferation and migration. The overexpression of PLAUR in TAMs was validated through immunofluorescence staining on tissue microarrays, supporting its relevance as both a biomarker and a functional contributor to HCC pathology34,35,36.

In addition to the regulatory role of PLAUR in macrophage polarization, our functional experiments demonstrated that PLAUR knockdown significantly inhibited the proliferation and migration of SKHep1 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. This suggests that PLAUR may not only modulate the immune microenvironment via macrophage polarization but also directly contribute to tumor progression by enhancing tumor cell aggressiveness. Mechanistically, Western blot analysis revealed that silencing PLAUR led to the suppression of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. This pathway is a central regulator of cell growth, survival, metabolism, and immune function and is frequently dysregulated in various cancers, including HCC. Its activation has been associated with increased tumor cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and immune evasion. In macrophages, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling also promotes M2 polarization and immunosuppressive activity, further contributing to tumor-supportive functions37,38. Therefore, PLAUR may exert its pro-tumorigenic effects, at least in part, through the activation of this pathway. Targeting PLAUR or downstream effectors in this signaling cascade could provide a dual therapeutic advantage by simultaneously impairing tumor cell viability and reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages toward an anti-tumor phenotype.

From a clinical perspective, the signature holds practical value for risk stratification and treatment decision-making in HCC. High-risk patients may benefit from combination or alternative therapies, while low-risk individuals could be prioritized for ICI-based regimens. As the included genes are detectable via qRT-PCR or targeted sequencing, the signature is technically feasible for routine use. Further validation and standardization may enable its integration into clinical workflows for personalized HCC management.

Compared with existing prognostic models for HCC—which are often based on clinical staging systems or bulk transcriptomic profiles—our model incorporates immune context through single-cell transcriptomic data and focuses specifically on macrophage-related gene expression39,40. This approach captures intratumoral immune heterogeneity and provides insights into the tumor–immune interface. While some gene-based models offer prognostic value, few have demonstrated predictive capacity for immunotherapy response41. By integrating ICI-related gene markers and validating response predictions through TIDE analysis, our model bridges this gap, offering both prognostic and therapeutic guidance. These advantages position our signature as a promising tool for precision oncology in HCC.

Despite these promising results, several limitations should be noted. The prognostic signature requires validation in larger, independent cohorts. The functional roles of other identified genes also warrant further mechanistic exploration. Additionally, while our communication analysis suggests key roles for PLAUR-positive TAMs, in vivo evidence is needed to fully confirm these interactions and their downstream effects. Nevertheless, our study provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the HCC immune microenvironment and presents a clinically actionable macrophage-related signature with translational potential.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: GSE149614 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE149614) and GSE14520 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi).

References

Ju Dong, Y. et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 589–604 (2019).

Josep, M. L. et al. Immunotherapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 151–172 (2021).

Bruno, S. et al. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 525–543 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20, 203–222 (2022).

Shuyan, L. et al. Genetic variants of m(6)A modification genes are associated with survival of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28, e18517 (2024).

Ilio, V. et al. Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Cell. Metab. 30, 36–50 (2019).

Benjamin, R. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages trigger MAIT cell dysfunction at the HCC invasive margin. Cell 186, 3686–3705 (2023).

Anthos, C. et al. The complex role of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 23, 1148–1156 (2022).

Luca, C. et al. A timeline of tumour-associated macrophage biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 23, 238–257 (2023).

De-Zhen, G. et al. Single-cell tumor heterogeneity landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma: unraveling the pro-metastatic subtype and its interaction loop with fibroblasts. Mol. Cancer. 23, 157 (2024).

Qiyi, Y. et al. Identification and analysis of significant genes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-hepatocellular carcinoma transformation: bioinformatics analysis and machine learning approach. Mol. Immunol. 174, 18–31 (2024).

Yonglin, H. et al. Pretreatment CT-based machine learning radiomics model predicts response in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib plus PD-1 inhibitors and interventional therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 12, e008953 (2024).

Shuming, Z. et al. Integration of clinical trial spatial multiomics analysis and virtual clinical trials enables immunotherapy response prediction and biomarker discovery. Cancer Res. 84, 2734–2748 (2024).

Yiming, L. et al. A single-cell atlas of the multicellular ecosystem of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 4594 (2022).

Xinxin, Z. et al. CellMarker: a manually curated resource of cell markers in human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D721–D728 (2018).

Andrew, B. et al. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 411–420 (2018).

Wentai, S. et al. Conditional survival of trimodal therapy for nonmetastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A SEER database analysis. Cancer Med. 11, 2356–2365 (2022).

Yan, Z. et al. Global characterization of immune infiltration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 14. (2021).

Yan, Q. et al. Cuproptosis correlates with immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment based on pan-cancer multiomics and single-cell sequencing analysis. Mol. Cancer. 22, 59 (2023).

Suoqin, J. et al. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using cellchat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088 (2021).

Masahiro, H. et al. Spatial and single-cell colocalisation analysis reveals MDK-mediated immunosuppressive environment with regulatory T cells in colorectal carcinogenesis. EBioMedicine. 103 (2024).

Yijian, Z. et al. Single-cell RNA-sequencing atlas reveals an MDK-dependent immunosuppressive environment in erbb pathway-mutated gallbladder cancer. J. Hepatol. 75, 1128–1141 (2021).

Insoo, K. et al. The immunobiology of MIF: function, genetics and prospects for precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 15, 427–437 (2019).

Krishnamoorthi, S. et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): A multifaceted cytokine regulated by genetic and physiological strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 233, 108024 (2021).

Marcelo, T. B. et al. The role of MIF on eosinophil biology and eosinophilic inflammation. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 58, 15–24 (2019).

Junmeng, Z. et al. Engineered Lactococcus lactis secreting Flt3L and OX40 ligand for in situ vaccination-based cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 13, 7466 (2022).

Zhixiong, C. et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine prevents postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with vascular invasion. Mol. Cancer. 20, 1–13 (2021).

Shulan, H. et al. d-lactate modulates M2 tumor-associated macrophages and remodels immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg2697 (2023).

Kebria, H. et al. Tryptophan-derived microbial metabolites activate the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor in tumor-associated macrophages to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Immunity 55, 324–340 (2022).

Filippo, G. D. O. et al. Tumour burden and efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 75–90 (2021).

Xian, Z. et al. Control of tumor-associated macrophage responses by nutrient acquisition and metabolism. Immunity 56, 14–31 (2023).

Gowri Rangaswamy, G. et al. M1 macrophage exosomes engineered to foster M1 polarization and target the IL-4 receptor inhibit tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages into M1-like macrophages. Biomaterials 278, 121137 (2021).

Xiaonan, X. et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages to synergize tumor immunotherapy. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 75 (2021).

Tao, Z. et al. TCF7L2 promotes Anoikis resistance and metastasis of gastric cancer by transcriptionally activating PLAUR. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 4560 (2022).

Chao, Z. et al. YY1 regulates the proliferation and invasion of triple-negative breast cancer via activating PLAUR. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 23, 269 (2023).

Zaixiang, F. et al. Identifying PLAUR as a pivotal gene of tumor microenvironment and regulating mesenchymal phenotype of glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 16, 840 (2024).

Xue, Z. et al. Hypoxic glioma-derived exosomal miR-25-3p promotes macrophage M2 polarization by activating the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling pathway. J. Nanobiotechnol. 22 (1), 628 (2024).

Zhang, A. et al. Lactate-induced M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages promotes the invasion of pituitary adenoma by secreting CCL17. Theranostics 11(8), 3839–3852 (2021).

Huang, H. et al. Multi-transcriptomics analysis of microvascular invasion-related malignant cells and development of a machine learning-based prognostic model in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 15, 1436131 (2024).

Zhang, G. X., Ding, X. S. & Wang, Y. L. Prognostic model of hepatocellular carcinoma based on cancer grade. World J. Clin. Cases. 11(27), 6383–6397 (2023).

Chen, H., Li, J., Cao, D. & Tang, H. Construction of a prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma based on macrophage polarization-related genes. J. Hepatocell Carcinoma. 11, 857–878 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. provided the ideas for the article, H.C. prepared all the figures, D.Cand J.Y. wrote the main manuscript text. Y.H. completed the experimental content that needs to be supplemented after repairing and analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Fuyang People’s Hospital of Anhui Medical University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. No human studies are presented in the manuscript. No potentially identifiable images or data are presented in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, S., Chen, H., Han, Y. et al. Construction of a macrophage-related prognostic signature and assessment of immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy of HCC. Sci Rep 15, 25065 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06937-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06937-3