Abstract

This research presents an Enhanced Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) deep learning model for robust noise reduction in automotive wheel speed sensors. While wheel speed sensors are pivotal to vehicle stability, high-intensity or non-stationary noise often degrades their performance. Traditional filtering methods, including adaptive approaches and basic digital signal processing, frequently underperform under complex conditions. The proposed model addresses these limitations by incorporating an attention mechanism that selectively emphasizes transient high-noise frames, preserving essential rotational information. Comprehensive experiments, supported by Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT), demonstrate that the Enhanced LSTM surpasses conventional techniques and baseline LSTM architectures in suppressing interference. T results yield significantly improved metrics across varying noise intensities, confirming both efficacy and stability. Although factors such as computational cost and the need for extensive labeled data remain, the Enhanced LSTM shows strong potential for real-time applications in wheel speed sensing. This work offers valuable insights into advanced noise mitigation and serves as a foundation for future deep learning research in complex automotive signal processing tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wheel speed sensors provide critical data for automotive safety systems such as ABS, TCS, and ESP. However, mechanical vibrations and electromagnetic disturbances can significantly degrade these signals, potentially compromising vehicle control. While earlier efforts employed adaptive filtering and basic digital signal processing, such methods often falter under the complex, non-stationary noise typical of real-world conditions. Recent developments in deep learning present more robust solutions. In particular, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks excel at capturing temporal dependencies in sequential data, a crucial property for isolating genuine signals from transient interference. Yet standard LSTM architectures may uniformly weight all time steps, missing high-amplitude noise bursts. To address this, the present study proposes an Enhanced LSTM model with an attention mechanism that focuses on noisy segments without losing essential rotational information. By more effectively filtering interference, the approach aims to reinforce wheel speed sensor accuracy, thereby contributing to safer, more reliable vehicle operation.

Noise reduction for wheel speed sensors has long been critical for vehicle safety. Early non-linear filtering methods were introduced by Schreiber and Grassberger1,2, followed by online learning approaches from Schwarz et al.3 and additional estimation techniques by Magnusson and Trobro4. Hernandez et al.5,6,7,8 employed adaptive filtering in frequency-domain and RLS-lattice configurations, significantly enhancing sensor clarity. Bentler and Chiou9 reviewed digital noise reduction for various sensor systems, whereas Li et al.10 improved tire-road friction monitoring with slip-based methods. Vaseghi11 presented a broader digital signal processing framework for noise reduction, and Yoshizawa et al.12 applied high-resolution frequency analysis to periodic signals. Ramli et al.13 reviewed adaptive line enhancers, while Dadashnialehi et al.14 developed a sensorless ABS system with adaptive control. Liqiang et al.15 adopted FFT-based noise filtering, and Tuma16 focused on noise reduction in gearboxes. Waugh et al.17 proposed cluster-analysis-based filtering, while Kim et al.18 introduced a hardware approach via injection molding for sensor improvement. Kang et al.19 shifted to software-based noise reduction for drones, marking continued progress in adaptive, domain-specific strategies for sensor accuracy.

Recent advances have increasingly combined multi-sensor fusion and machine learning for noise suppression. Ding et al.20 introduced a vehicle speed estimation approach using fusion techniques, while Fariña et al.21 leveraged Doppler-based sensor covariance for enhanced robot localization. Kelemenová et al.22 explored noise reduction and filtering methods, and Wang et al.23 emphasized the role of machine learning and compressed sensing in signal reconstruction. Zhang et al.24 applied local mean decomposition to LiDAR signals, and Prajapati and Darji25 developed FPGA-based adaptive filtering for impulsive noise. Ormiston et al.26 employed deep learning to mitigate gravitational-wave interference, while Ga and Kang27 refined tire dynamic rolling radius in i-TPMS. Zhan et al.28 focused on speed sensor fusion for urban rail transit, and Lin and Wu29 improved 3D LiDAR signals via Kalman filtering. Abdulkareem et al.30 proposed a robust fault detection method for ABS speed sensors, Park et al.31 introduced sensor set expansion for active road noise control, and Spinosa and Iafrati32 adopted ensemble empirical mode decomposition for force measurements. Brandt33 covered noise and vibration analysis in sensor applications, Khan and Burdzik34 reviewed measurement techniques for transport noise, and Cha et al.35 demonstrated a deep learning feedback noise control system. Additionally, recent studies have explored partial domain adaptation for life prediction by Li et al.36, neuromorphic computing for fault diagnosis by Chen et al.37, and Swin Transformer architectures for battery state estimation in electric aircraft by Zhang et al.38.

Peng et al.39 addressed impulsive noise in planetary gearbox speed estimation. Jin et al.40 proposed a robust approach for indirect tire pressure monitoring based on tire torsional resonance frequency analysis, and Zhang et al.41 introduced cross-correlation algorithms with MEMS wireless sensors for vehicle speed estimation. Nagaraju et al.42 developed an optical sensor rig for real-time speed measurement, whereas La and Kwon43 applied spectral subtraction to suppress ambient sensor noise in wind tunnel tests. Pandharipande et al.44 reviewed sensing and machine learning methods in automotive perception, and Jaros et al.45 investigated advanced signal processing for condition monitoring. Zhao et al.46 adopted an adaptive multi-feature fusion method to recognize vehicle micro-motor noise, while Cha et al.47 presented a deep learning-based structural health monitoring system. Ding et al.48 employed deep time–frequency learning to enhance weak signals in rotating machinery, and Hassani49 integrated AAE-VMD fusion with optimized machine learning for meta-model structural monitoring. Finally, Zhang et al.50 implemented narrowband line spectrum noise control via a nearest neighbor filter and BP neural network feedback mechanism.

Yu et al.51 and Sherstinsky52 surveyed recurrent neural network architectures, underscoring the strengths and limitations of LSTM cells in capturing long-term dependencies. The seminal work by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber53 introduced LSTM to address vanishing gradients in standard RNNs, later refined by Graves54, who applied LSTM to sequence generation tasks. As neural machine translation advanced, Bahdanau et al.55 proposed an additive attention mechanism that selectively focuses on salient input segments, followed by Luong et al.56, who introduced effective attention-based translation approaches. Subsequent reviews, such as Niu et al.57, expanded on the broad applicability of attention in deep learning, while Ranjbarzadeh et al.58 and UrRehman et al.59 illustrated attention’s impact in medical image segmentation and detection tasks. Further surveys by de Santana Correia and Colombini60 offered a systematic overview of neural attention models, and Wu et al.61 demonstrated multi-modal graph-transformer architectures enriched by attention for drug-target affinity. Xu et al.62 adopted an attention-based deep learning strategy for heat load prediction in industrial manufacturing, emphasizing the mechanism’s adaptability. Finally, Islam et al.63 presented a comprehensive analysis of Transformers, highlighting the expanding role of attention in state-of-the-art deep learning applications.

Despite the substantial progress detailed in prior literature, advantages and disadvantages persist across different approaches to noise reduction for wheel speed sensing. Traditional non-linear filters1,2 and adaptive techniques10 effectively handle moderate or stationary noise, yet often struggle with dynamic or impulsive interference. More recent machine learning solutions23,54 better manage complex noise patterns but require extensive parameter tuning and large labeled datasets. While LSTM-based methods capture long-term dependencies more robustly, their uniform treatment of time steps can overlook transient high-amplitude interference. Integrating an attention mechanism55,57,62 selectively focuses on salient frames, partially alleviating these shortcomings, though issues such as increased computational cost and optimal training strategies remain. These observations highlight the need for a model that balances robust noise suppression against practical constraints—a gap this enhanced LSTM framework aims to fill.

The approach involves training a multi-layer Enhanced LSTM on large labeled datasets, ensuring generalization through cross-validation. The model’s efficacy is further verified via Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD)64,65 and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT)66,67, which reveal robust noise suppression with minimal loss of essential rotational information. Nevertheless, considerations such as computational overhead, model interpretability, and data availability remain. Overall, this work illustrates both the promise of attention-driven deep learning for wheel speed sensor noise elimination and the necessity of addressing practical constraints in high-noise automotive environments.

Research methodology

The enhanced LSTM deep learning model with attention mechanism

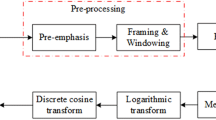

This study introduces an Enhanced Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Model integrating an attention mechanism to improve noise elimination in automotive wheel speed sensors. While classical LSTM architectures51,52,53,54,55 capture long-term dependencies in sequential data and effectively handle nonlinear relationships, they often assign equal importance to each time step, potentially overlooking transient bursts of interference. To address this limitation and enhance methodological innovation, we incorporate an attention module that adaptively emphasizes high-impact frames where noise is most detrimental, thereby preserving subtle rotational signals essential to wheel speed measurements. The model begins with a sequence input layer, where each time step contains a single sensor reading, ensuring short-term fluctuations and longer rotational trends are captured. Data then pass into an LSTM Layer of 64 hidden units, governed by input, forget, and output gates as follows:

where \(x_{t}\) is the input at time \(t\), \(h_{t - 1}\) is the previous output, and \(C_{t}\) is the cell state. By retaining relevant historical context and discarding irrelevant noise, the LSTM effectively addresses the high-frequency interference prevalent in wheel speed signals. After the LSTM, an attention mechanism adaptively reweighs each hidden state according to its estimated contribution to signal clarity, following the additive attention framework originally described in56,57,58,59. This attention-based approach refines the extracted features before they enter fully connected and ReLU layers, culminating in an output layer that estimates a noise-reduced wheel speed. A regression layer then quantifies the residual error relative to the target signal, enabling iterative error minimization for both LSTM parameters and attention weights.

To further refine the focus on transient noise components, we introduce an additive attention mechanism immediately following the LSTM layer. For a sequence of LSTM hidden states \(\{ h_{1} , h_{2} , \ldots ,h_{T} \}\), the model first computes a score \(e_{t}\)ete_tet for each time step \(t\):

followed by a softmax normalization to derive the attention weight αt:

and then obtains a context vector ccc by weighting all hidden states:

This attention-based context vector highlights high-impact segments—such as abrupt speed changes or short bursts of interference—allowing the network to better isolate and remove random noise.

After extracting attention scores and possibly retaining the original hidden states, a context merging operation integrates these signals. A minimal example sums two inputs \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) as

In a complete attention pipeline, one might compute \(Z = \mathop \sum \limits_{t} \alpha_{t} h_{t}\). Regardless of the specific merge strategy, combining attention-derived representations and raw LSTM features preserves both global context and crucial local variations.

The resulting representation passes through fully connected layers with ReLU activations:

followed by an output layer producing a denoised wheel speed prediction \(\hat{y}\):

A Regression layer then compares \(\hat{y}\) to the ground truth \(y\), minimizing the residual error and updating parameters for both the LSTM and the attention mechanism. The Fig. 1 illustrates the conceptual setup for monitoring wheel speed, consisting of a toothed wheel, a wheel speed sensor enclosed in protective casing, and the enhanced LSTM module, which processes the sensor signals to generate control signals for the vehicle’s controller.

While attention-driven LSTM focuses on the time domain, we employ Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) to confirm that noise elimination also preserves essential frequency components. VMD separates the noisy sensor signal into multiple intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), illustrating how higher-frequency interference is suppressed while critical lower-frequency rotation patterns are retained. Subsequently, HHT projects each IMF into a Hilbert spectrum, showing how noise energy and wheel rotation frequencies evolve across time steps.

By adaptively weighting significant time frames, this Enhanced LSTM with an Attention Mechanism surpasses conventional LSTM-based noise filtering. The method addresses high levels of interference by directing greater model capacity toward brief but impactful fluctuations—an approach particularly relevant for automotive wheel speed sensing. The integration of VMD–HHT analyses further ensures that fundamental rotational frequencies remain intact even under severe noise. Although designed for wheel speed sensor data, the proposed framework can be readily extended to other sequential tasks requiring robust denoising in dynamically changing conditions.

Variational mode decomposition (VMD)

The objective of VMD is to decompose a complex signal into a number of band-limited Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs)64,65. VMD achieves signal decomposition by solving the following optimization problem, where \(y_{pred}\) is decomposed into a series of IMFs, denoted as \(u_{k} \left( t \right)\), with each \(k\) corresponding to a mode.

subject to

Here, \(u_{k} \left( t \right)\) represents the kth IMF, and \(\omega_{k}\) is the corresponding central frequency, \(\delta \left( t \right)\) is the Dirac function, ∗ indicates convolution, and \(K\) is the preset number of modes.

Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT)

HHT is a method for analyzing nonlinear and non-stationary signals, comprising two steps: initially, the signal is decomposed into a series of IMFs using methods like Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) or Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) ; subsequently, Hilbert Transform (HT)66,67 is applied to each IMF to obtain a representation of the instantaneous frequency over time.

where \(H\left( {u_{k} \left( t \right)} \right)\) is the Hilbert Transform of IMF \(u_{k} \left( t \right)\), and P.V. denotes the Cauchy principal value integral.

The process of time–frequency analysis combining VMD and HHT

-

1.

Signal decomposition using VMD: Initially, the original signal \(y_{pred}\) is decomposed into several IMFs through VMD.

-

2.

Generation and plotting of IMFs: Subsequently, three-dimensional charts are utilized to display the variation in modal number and modal amplitude of each IMF over time.

-

3.

Applying HHT analysis to IMFs: Finally, HHT analysis is applied to each IMF obtained from VMD to generate time–frequency plots.

This combined analysis method of VMD and HHT enables the study to present the noise elimination effects of automotive wheel speed sensors more specifically. It not only validates the effectiveness of noise elimination in the time domain but also provides detailed information on signal components in the frequency domain, enriching and crediting the research results.Time–frequency validation via Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) confirms that the attention mechanism preserves low-frequency rotational information and effectively suppresses erratic noise components. The integrated approach demonstrates notable improvements over pure LSTM-based filtering, thereby offering a robust and innovative solution to the noise elimination challenges faced by modern automotive wheel speed sensors.

Results and discussion

Experimental design and analysis for noise elimination in automotive wheel speed sensors

In this study, experiments were conducted on the noise elimination of simulated signals from automotive wheel speed sensors, comparing the performance of traditional Least Squares Method (LSM), Kalman Filter, Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM), and an enhanced LSTM model. Figure 2 displays the simulated signal of the automotive wheel speed sensor, where parameter settings play a crucial role in the experimental design. Here is a description of the main parameters used in the experiments:

-

1.

Sampling rate (Fs): Set at 1000 Hz, indicating the signal is sampled 1000 times per second. A high sampling rate captures rapid changes in the signal accurately, crucial for simulating high-frequency signals.

-

2.

Time axis (t): Generated by starting from 0, with steps of 1/Fs, until one second minus one sampling period, to create a vector representing time. This vector provides a temporal foundation for the entire simulated signal, ensuring accurate simulation throughout the second.

-

3.

Square wave frequency (f): Set at 50 Hz, meaning the simulated square wave signal oscillates through 50 cycles per second. This frequency choice reflects the typical signal frequency that wheel speed sensors might need to simulate, mimicking the rotation of wheels at a certain speed.

-

4.

Square wave signal (x): Generated using the square function and the parameters above, creating a 50 Hz square wave signal. By multiplying 2πf with the time vector t, a periodic square wave is created, alternating between + 1 and -1, simulating the ideal output signal of wheel speed sensors.

These parameter settings provide a foundational framework for simulating signals from automotive wheel speed sensors, allowing researchers to evaluate the effects of different noise elimination technologies in a controlled environment. To further simulate the challenges faced by real-world automotive wheel speed sensors under various road conditions, white Gaussian noise was added to the simulated square wave signal to mimic environmental interference. Below is a detailed explanation of this process:

-

1.

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR): Set at 10 dB, SNR is a measure of signal strength relative to background noise strength. Here, a 10 dB SNR means the signal’s power is ten times that of the noise power, a ratio relatively common in practical applications to simulate a certain level of noise environment.

-

2.

Generating white Gaussian noise: White Gaussian noise of the same size as the square wave signal is generated using the randn function. White Gaussian noise, with zero mean and unit variance normal distribution, represents random noise without specific frequency components, a common type of simulated noise.

-

3.

Adjusting noise mean: The mean of the noise is subtracted to ensure the generated white Gaussian noise has a zero mean. This step simulates real scenarios where noise usually does not cause a systematic offset to the signal.

-

4.

Setting SNR: The noise variance is adjusted to meet the set SNR condition by calculating the ratio between the signal variance and the desired SNR, then adjusting the noise variance accordingly.

-

5.

Adding noise to signal: The white Gaussian noise—adjusted according to the target SNR—is added to the original 50 Hz square wave, resulting in the disturbed signal y. An example of the 30 dB SNR condition is depicted in Fig. 3, while a 10 dB SNR variant is shown in Fig. 4.

Simulated automotive wheel speed sensor subject to environmental interference in a realistic environment (50 Hz, 1000 Hz Sampling, 10 dB SNR). A 1-s time series generated by adding white Gaussian noise (10 dB SNR) to a 50 Hz square wave, illustrating typical amplitude fluctuations under automotive road conditions.

Figure 4 presents the VMD and HHT analysis of the wheel speed sensor signal at 30 dB noise. Through these steps, the study successfully introduced white Gaussian noise into the simulated signal, creating a test environment closer to real application conditions. This allowed researchers to test and evaluate the effectiveness of different noise elimination technologies within a specific noise level environment, providing a crucial foundation for developing more robust signal processing algorithms for wheel speed sensors.

By applying Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) to the signals post noise elimination, this study was able to obtain time–frequency representations of the noise elimination effects, thus enabling a more in-depth analysis and verification of the noise elimination performance.

-

VMD analysis: VMD decomposes the signal into a series of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) with clear physical significance, facilitating the analysis of different frequency components within the signal. By comparing the IMFs before and after noise elimination, this study visually observes the process of effective noise component removal.

-

HHT analysis: In this study, we combine Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) to perform time–frequency analysis on wheel speed sensor data exposed to different noise conditions. This approach enables observation of each mode’s instantaneous frequency distribution before and after noise suppression. Figure 5 first presents results for a noise-free, simulated signal undergoing VMD and HHT analysis, while Figs. 6 and 7 respectively illustrate the model’s performance and residual noise retention across multiple noise levels (including purely environmental noise). These results verify the proposed method’s versatility and reliability under a range of interference scenarios.

Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) Analysis of the Noise-Free Automotive Wheel Speed Sensor Signal. Illustrates how, in the absence of external interference, VMD and HHT decompose the sensor reading into distinct frequency components, confirming stable rotational features and validating the baseline waveform.

VMD amd HHT analysis of the automotive wheel speed sensor signal with 30 dB noise. Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) reveal the time–frequency structure of the disturbed 50 Hz signal (0–1 s), highlighting both the fundamental wheel speed component and residual noise-driven modes.

Results of the variational mode decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) Analysis on Environmental Interference Noise. Shows the pure white Gaussian noise (10 dB SNR, 1-s interval, 1000 Hz sampling), illustrating broadband fluctuations and frequency content without the underlying 50 Hz square wave.

Integrating VMD and HHT analysis, this study not only evaluates the effects of noise elimination from a time-domain perspective but also delves into the frequency domain, meticulously analyzing the changes in signals post noise elimination. This multidimensional analysis approach provides a more comprehensive and in-depth perspective for evaluating and comparing different noise elimination technologies. This study demonstrates the application potential of deep learning methods, particularly the enhanced LSTM, in the domain of noise elimination for automotive wheel speed sensors. By combining time–frequency analysis through VMD and HHT, the study achieves a more comprehensive understanding and evaluation of the performance of noise elimination technologies, offering valuable references for future research and applications. Future studies could further explore how to integrate these analysis methods to optimize noise elimination techniques for more complex real-world applications.

Least mean squares (LMS) algorithm

In this study, the Least Mean Squares (LMS) algorithm was employed for noise elimination in simulated signals from automotive wheel speed sensors. The LMS algorithm is an adaptive filter that iteratively updates the filter’s coefficients to minimize the mean square error between the output signal and the desired signal. Here is a description of the results from utilizing the LMS algorithm for noise elimination, with an explanation of the relevant experimental parameter settings:

-

Learning rate: Set at 0.01, controlling the step size of the filter coefficient updates. A smaller learning rate helps stabilize the filter’s convergence process but may result in a slower convergence rate.

-

Filter order (M): Selected to be of the 32nd order, indicating that the filter considers the current sample and its previous 31 samples for noise elimination. A higher filter order can capture the signal’s characteristics better but also increases computational complexity.

-

Signal length (N): Equal to the length of the signal affected by noise, ensuring the entire signal sequence is processed.

During the iterative process of the LMS algorithm, the filter coefficients are continuously updated based on the calculated error, progressively reducing the noise components of the signal.

-

Filtered signal: The LMS algorithm successfully reduced the noise level in the signal, making the filtered signal closer to the original square wave shape. Although slight delays and shape distortions are present, mainly influenced by the filter design and the choice of learning rate, overall, the LMS algorithm effectively recovered the main characteristics of the signal, as shown in Fig. 8.

-

Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT): Furthermore, this study employed two advanced signal processing techniques, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT), for visual analysis of the noise elimination effects. Figure 9 displays the noise elimination result using the combined VMD and HHT analysis methods.

The LMS algorithm, as a classical adaptive filtering technique, demonstrated good performance in the application of noise elimination for automotive wheel speed sensors. With appropriate selection of the learning rate and filter order, the LMS algorithm can effectively recover useful information from noisy signals without prior knowledge. However, the performance of the algorithm is also limited by the choice of learning rate and filter design, which may require experimental optimization to achieve the best noise elimination effects. Future research could explore combining the LMS algorithm with other signal processing technologies, such as LSTM or enhanced LSTM, to further improve the accuracy and robustness of noise elimination.

Recursive least squares (RLS) algorithm

In this study, the Recursive Least Squares (RLS) algorithm was employed for noise elimination in simulated signals from automotive wheel speed sensors. The RLS algorithm is an adaptive filtering method that minimizes the least squares of the error between the desired signal and the output signal. The key advantage of the RLS algorithm over LMS is its faster convergence rate, making it more efficient in highly dynamic environments. Here is a description of the results from utilizing the RLS algorithm for noise elimination, with an explanation of the relevant experimental parameter settings:

-

Forgetting factor (λ): Set at 0.98, this parameter controls how much past data is “forgotten” as the filter adapts to new input data. A value close to 1 causes the filter to consider older data more, making the filter more stable but slower to adapt to changes. A smaller value would prioritize more recent data, enabling faster adaptation.

-

Filter order (M): Chosen to be the 32nd order, the filter considers the current sample and the previous 31 samples for noise elimination. A higher filter order allows the filter to better model the signal but also increases the computational complexity.

-

Signal length (N): Equal to the length of the signal affected by noise, ensuring that the entire signal sequence is processed by the filter.

During the iterative process of the RLS algorithm, the filter coefficients are updated at each step based on the current error, progressively reducing the noise components of the signal. This algorithm uses a recursive approach to compute the filter gain vector and update the inverse correlation matrix efficiently.

-

Filtered signal: The RLS algorithm demonstrated excellent noise elimination, reducing the noise level in the signal. Compared to LMS, the RLS algorithm achieved faster convergence to the true signal, with minimal distortion and delay, as shown in Fig. 10. The filtered signal was much closer to the original square wave shape with very low residual noise.

-

Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT): As with the LMS approach, this study employed Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) for advanced signal analysis. Figure 11 shows the result of noise elimination using the combined VMD and HHT analysis methods, further illustrating the effectiveness of the RLS algorithm in denoising.

The RLS algorithm, as an advanced adaptive filtering technique, performed remarkably well in the context of noise elimination for automotive wheel speed sensors. Its rapid convergence and ability to handle dynamic signals made it a more effective solution than LMS in this application. However, the computational complexity of the RLS algorithm is significantly higher than LMS, which could limit its real-time applications in systems with limited processing power. Future research could focus on optimizing the computational efficiency of the RLS algorithm, possibly integrating it with machine learning models such as LSTM to further enhance noise elimination accuracy and robustness.

Kalman filter

In this study, the Kalman filter was employed for noise elimination in simulated signals from automotive wheel speed sensors. Through carefully designed parameter initialization and algorithm implementation, the Kalman filter demonstrated its strong capability in handling noisy signals.

Kalman filter parameter settings

-

Process noise covariance (Q): Set to 0.1, a smaller value reflects high confidence in the model’s predictions, indicating lower uncertainty in the model forecasts.

-

Measurement noise covariance (R): Set at half the original noise variance, suggesting the study assumes the estimated measurement noise is slightly lower than the actual noise level, increasing the model’s trust in the observations.

-

Estimation error covariance (P): The initial value is set to 1, representing the uncertainty of the initial estimate.

Noise elimination results: The Kalman filter performed excellently in noise elimination. By dynamically updating the filter coefficients, it effectively estimated the original square wave signal, significantly reducing the noise components in the signal disturbed by white Gaussian noise.

-

Filtered signal: Results in Fig. 12 show that the filtered signal closely resembles the original signal, with noise effectively eliminated. The Kalman filter successfully recovered the main characteristics of the square wave, although there might be slight smoothing effects at the edges of the signal.

-

HHT: The study also incorporated two advanced signal processing techniques, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT), for an in-depth analysis and visualization of the noise elimination effects. Figure 13 displays the noise elimination results of the Kalman filter using the combined VMD and HHT analysis methods.

The Kalman filter has proven its effectiveness as a powerful noise elimination tool in this study, especially when the parameters are set appropriately. Its strength lies in the dynamic estimation of signals and noise, making it particularly suited for handling dynamically changing signals like those from automotive wheel speed sensors. However, the performance of the Kalman filter highly depends on the accurate estimation of process noise and measurement noise covariances. In practical applications, this requires a deep understanding of the system and noise characteristics to correctly set these parameters. Future work could explore methods for automatically adjusting these covariance parameters to further enhance the adaptability and robustness of the Kalman filter under various conditions.

Traditional long short-term memory networks

In this study, traditional Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM) were employed for noise elimination in simulated signals from automotive wheel speed sensors, complemented by in-depth signal analysis through Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) to demonstrate the effects of noise elimination.

Training options configuration for the LSTM model

-

Optimizer (adam): Adam was chosen as the optimization algorithm, a gradient descent method based on adaptive estimation, widely used in deep learning training. The Adam optimizer combines the advantages of momentum and RMSprop, automatically adjusting the learning rate under various conditions for faster and more stable convergence.

-

Maximum training epochs (MaxEpochs): Set to 50 epochs. In each epoch, the entire training set is traversed once. More training epochs help the model to better learn data features but may also increase the risk of overfitting.

-

Mini-batch size (MiniBatchSize): Set to 32, meaning 32 samples are randomly selected for training in each iteration. Mini-batch training improves memory utilization, speeds up training, and helps model convergence.

-

Initial learning rate (InitialLearnRate): Set to 0.001. The learning rate determines the step size for weight updates, where an appropriate learning rate can make model training more efficient while avoiding instability due to overly large updates.

-

Data shuffling (Shuffle): Set to every-epoch, indicating training data is randomly shuffled at the beginning of each training cycle. This helps reduce bias in model training and improves model generalization.

-

Verbose output (Verbose): Set to false, meaning detailed training progress information will not be displayed in the command window during training, streamlining the training process.

-

Training progress plots (Plots): Set to none, indicating training progress charts are not automatically drawn. This setting makes the training process more lightweight, especially when running in automated scripts or resource-constrained environments.

With these carefully chosen parameter settings, the LSTM model was effectively trained, achieving efficient elimination of noise signals. Adjusting these parameters can further optimize model performance to meet different noise processing requirements.

LSTM noise elimination results: A LSTM network model was successfully trained, processing a square wave signal with white Gaussian noise as shown in Fig. 14. The LSTM model utilized its memory cells to capture the temporal characteristics of the signal, effectively recovering the original signal from the noise. After model training, the predicted signal exhibited a shape highly similar to the original square wave signal, with significant noise reduction.

Application of VMD and HHT analysis: To further validate the effectiveness of LSTM noise elimination and to understand the characteristic changes of the signal, the study conducted VMD and HHT analysis on the predicted signal.

-

VMD analysis: Decomposing the signal processed by LSTM into several Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) through VMD, the study observed changes in various frequency components of the signal. VMD analysis revealed how LSTM effectively eliminated noise frequency components while preserving the signal’s main characteristics.

-

HHT analysis: After obtaining IMFs, applying HHT analysis provided time–frequency plots of the signal, showing changes in instantaneous frequency and amplitude over time. Figure 15 shows the HHT time–frequency plots, indicating the maintenance of the signal’s main frequency components and the reduction of noise frequency components during noise elimination, further confirming the effectiveness of LSTM in noise removal.

By integrating the traditional LSTM model with advanced signal analysis methods like VMD and HHT, this study comprehensively showcased the capabilities of LSTM in noise elimination. The LSTM model not only effectively eliminated noise but also preserved the main characteristics of the signal, while VMD and HHT analysis offered powerful tools for analyzing and validating the effects of noise elimination, providing valuable references for the development of future noise processing technologies. This comprehensive analysis approach aids in a more holistic understanding and evaluation of noise elimination technology performance, especially in complex signal processing scenarios.

Enhanced long short-term memory network with attention

In this study, an enhanced Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model was employed to eliminate noise from simulated automotive wheel speed sensor signals, with additional Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) analyses to illustrate the denoising impact in the time–frequency domain. To ensure a fair comparison, the baseline LSTM configurations (hidden units, data format) were retained. However, a specialized attention mechanism was incorporated to adaptively focus on transient interference segments, thus improving noise suppression without discarding critical rotational information.

The enhanced architecture consists of two LSTM layers with 5 and 10 hidden units respectively, each followed by a low-dropout rate (0.01) to prevent overfitting while preserving delicate waveform features. A Bahdanau-style attention module was then introduced. Specifically, each LSTM hidden state \(h_{t}\) is assigned a preliminary score according to Eq. (7), which is then normalized via a softmax to produce the attention weights \(\alpha_{t}\). The final context vector merges these weighted states, highlighting frames prone to noise spikes or abrupt rotational changes. This design ensures that the enhanced LSTM pays greater attention to high-impact regions, further refining the signal reconstruction. Following the attention block, two fully connected layers (64 units, then 1 unit) and ReLU activation produce the final noise-reduced output. A regression layer measures the prediction error relative to ground truth. As shown in Fig. 16, the enhanced LSTM with attention effectively recovers a clear square-wave form from the 50 Hz noisy signal. Compared to a conventional LSTM, the attention-based model exhibits sharper transition regions and fewer residual artifacts. This improvement indicates that dynamically reweighting hidden states better isolates noise-dominated segments, thereby improving the overall waveform fidelity.

-

VMD analysis: Once the network has generated its denoised output, VMD is applied to decompose the signal into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). These IMFs reveal distinct frequency bands within the reconstructed waveform. By comparing each IMF to those obtained from the raw noisy signal, we observe that the high-frequency noise components are substantially attenuated, whereas the fundamental rotational frequencies remain intact. This outcome underscores the synergy of the attention mechanism and LSTM in retaining core features while discarding transient interference.

-

HHT analysis: Subsequently, HHT is performed on the IMFs to produce time–frequency plots, as illustrated in Fig. 17. These plots confirm a notable reduction in broadband noise while showcasing the preserved 50 Hz base frequency, crucial for wheel speed measurements. The attenuation of random, high-amplitude fluctuations indicates that the attention-based approach successfully focuses on segments of interest, mitigating erratic bursts without distorting the principal rotational pattern.

By integrating a Bahdanau-style attention layer with a low-dropout, two-layer LSTM architecture, this enhanced model achieves robust noise elimination. The parameter settings—particularly the reduced dropout rate and adaptive attention weighting—collectively boost the network’s ability to target high-noise frames while upholding the core signal. VMD and HHT analyses provide an in-depth view of how noise-dominated modes are suppressed across the time–frequency domain, reinforcing the model’s efficacy. This research offers novel insights and methodological tools for deep learning in complex signal processing contexts, where precision is paramount for real-time applications. Future work may involve evaluating the enhanced LSTM on diverse signal types or exploring additional attention variants to further augment noise elimination and computational efficiency.

Error results of noise elimination using five different algorithms

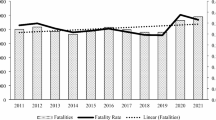

Figure 18 presents the error results of five different algorithms in noise elimination, including (A) Least Mean Squares (LMS), (B) Recursive Least Squares (RLS) (C) Kalman Filter, (D) Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM), and (E) Enhanced LSTM. The following is an organization and analysis of the error results for each algorithm:

Least mean squares (LMS): The error signal analysis of the LMS algorithm shows that the error gradually decreases with an increase in iterations, with a larger error in the initial phase stabilizing at a lower level thereafter. This indicates that the LMS filter can progressively adapt to the characteristics of the signal and gradually converge during the iteration process.

Kalman filter: The error signal analysis of the Kalman filter reveals that the difference between the original and estimated signals gradually diminishes as the filter adapts. After reaching a steady state, the error remains at a lower level, demonstrating the Kalman filter’s effective estimation and recovery capability for the signal.

Long short-term memory network (LSTM): The error signal graph of the LSTM model displays the difference between the original signal and the LSTM predicted signal, clearly proving the LSTM model’s efficiency in reducing noise and recovering the signal. LSTM effectively reduces the error by learning the long-term dependencies of the signal.

Enhanced LSTM: The enhanced LSTM exhibited the smallest error and superior performance among all algorithms. This indicates that the enhanced LSTM model, through optimization and adjustments, can more accurately capture the characteristics of the signal and more effectively eliminate noise, recovering a form close to the original signal.

Comprehensive analysis: Comparing the error results of the five algorithms clearly shows the significant advantage of the enhanced LSTM in noise elimination, offering more accurate signal recovery. Although the LMS and Kalman filter can also gradually reduce error, their performance is not as strong as that of the LSTM and enhanced LSTM. These results highlight the potential and superiority of deep learning models, especially the enhanced LSTM, in complex signal processing tasks.

Performance comparison of noise elimination using five different algorithms

Table 1 presents the evaluation outcomes for Least Mean Squares (LMS), Recursive Least Squares (RLS), Kalman Filter, Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM), and Enhanced LSTM. Each method is assessed via Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), and the Correlation Coefficient (R). These metrics collectively illustrate the effectiveness of each algorithm in mitigating noise and preserving the fundamental characteristics of the wheel speed signal.

Mean Squared Error (MSE) measures the average squared difference between predicted and actual values. As listed in Table 1, LMS achieves 1.938626, and RLS attains 1.930258, indicating limited noise reduction capacity. The Kalman Filter improves upon these baselines with 0.087108, demonstrating more advanced filtering capabilities. LSTM further refines performance to 0.039759, showcasing the benefit of deep sequential modeling. The Enhanced LSTM advances this result substantially, producing 0.000662, which highlights its remarkable precision in suppressing noise while retaining the core signal.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), the square root of MSE, retains the same units as the original signal. Table 1 shows LMS at 1.392345 and RLS at 1.389337, suggesting similar denoising effectiveness. The Kalman Filter brings this down to 0.295141, marking a notable leap. LSTM records 0.140902, affirming stronger noise suppression. Meanwhile, the Enhanced LSTM yields 0.010640, underscoring exceptional alignment with the reference waveform and highlighting its fine-grained noise elimination capability.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), reported in decibels, indicates how strongly the meaningful signal stands out from the background noise. Table 1 shows that LMS provides 12.166664 dB and RLS gives 11.865727 dB, reflecting basic noise mitigation. The Kalman Filter records 10.602338 dB, which is somewhat lower than the linear methods in this dataset, perhaps due to parameter-tuning limitations. LSTM raises the SNR to 14.008629 dB, confirming deeper architectures can enhance signal clarity. Most notably, the Enhanced LSTM achieves 31.797619 dB, revealing a dramatic improvement in isolating the underlying wheel speed signal from interference.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) captures the average magnitude of the deviations between predictions and actual readings. LMS yields 1.051012, while RLS slightly trails at 1.056992, indicating marginal performance differences. The Kalman Filter cuts the error to 0.226804, highlighting better noise handling. LSTM registers 0.140902, lowering the residuals even further. The Enhanced LSTM reduces MAE to 0.010640, exemplifying precise reconstruction of the target signal across each time step, an attribute crucial for real-time automotive control.

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), also in decibels, relates the maximum signal amplitude to the noise level. As indicated in Table 1, LMS posts − 2.874940 dB, with RLS close by at − 2.856153 dB, suggesting insufficient restoration of the original peak values. The Kalman Filter yields 10.599401 dB, a substantial boost. LSTM pushes PSNR to 21.546593 dB, underscoring a more reliable signal. Enhanced LSTM vastly surpasses the others, reaching 46.325974 dB, thereby maintaining near-ideal peak integrity and demonstrating superior recovery from distortion.

The correlation coefficient R estimates how closely the predicted signal matches the actual data, with values near 1 reflecting strong alignment. Table 1 shows LMS at 0.969277 and RLS at 0.966902, illustrating moderate success. The Kalman Filter logs 0.955583, performing comparably on some metrics but achieving a slightly lower correlation here. LSTM climbs to 0.980656, reinforcing the advantage of deep learning in capturing intricate temporal dependencies. Enhanced LSTM approaches near-perfect fidelity at 0.999507, signifying minimal deviation and a highly reliable reconstruction of the wheel speed signal.

Overall, the Enhanced LSTM distinguishes itself by outperforming all other algorithms across every metric. Its substantial gains in accuracy and signal quality—evident in the drastic reductions in error metrics and the surge in SNR, PSNR, and R—demonstrate its efficacy for complex noise elimination tasks in automotive wheel speed sensing. Although each of the competing methods (LMS, RLS, Kalman Filter, and LSTM) contributes incremental improvements, only Enhanced LSTM achieves consistently high performance across all indicators, making it the most promising solution for robust and precise noise reduction.

Results and discussion of the ablation study

Table 2 shows how varying hyperparameters affects the Enhanced LSTM Model’s MSE and SNR. The choice of optimizer strongly influences both MSE and SNR. Using Adam, the Enhanced LSTM achieves MSE 0.000662 and SNR 31.797619 dB, demonstrating superior noise suppression and signal clarity. Substituting SGD elevates the MSE to 0.001500 and reduces the SNR to 30.219953 dB, indicating less stable convergence. RMSprop improves upon SGD, yielding MSE 0.000902 and SNR 31.042187 dB, but still falls short of Adam. These findings highlight Adam’s capability to converge on robust parameter configurations, a benefit particularly pronounced when the attention mechanism helps isolate high-noise frames.

Varying training duration significantly alters outcomes. At 50 epochs, the baseline produces MSE 0.000662 and SNR 31.797619 dB, marking the best setting. Reducing epochs to 30 degrades performance to MSE 0.000785 and SNR 31.248965 dB, indicating insufficient training for capturing subtle noise patterns. Extending to 100 epochs yields MSE 0.000711 and SNR 31.509342 dB, which surpasses 30 epochs but does not exceed the baseline. These results suggest that fully leveraging the attention mechanism depends on balanced training time—excessive epochs may lead to diminishing returns without further hyperparameter tuning.

Adjusting the mini-batch size also affects the denoising quality. A batch size of 32 obtains MSE 0.000662 and SNR 31.797619 dB, delivering the most accurate outcomes. Reducing to 16 raises MSE to 0.000900 and lowers SNR to 31.003421 dB, whereas increasing to 64 registers MSE 0.000785 and SNR 31.389022 dB. Both alternatives prove suboptimal relative to the baseline. These variations echo the fact that the attention-based Enhanced LSTM needs a mini-batch size adequate to capture the episodic noise spikes in each pass, ensuring that high-noise windows are consistently identified.

Modifying the initial learning rate has a pronounced effect on model performance. At 0.001, the baseline produces MSE 0.000662 and SNR 31.797619 dB. Lowering the rate to 0.0005 leads to MSE 0.000935 and SNR 30.765432 dB, potentially reflecting underfitting. Raising it to 0.01 increases MSE to 0.001110 and decreases SNR to 29.847531 dB, highlighting instability from excessive step sizes. In all cases, the presence of the attention mechanism can only be fully harnessed when gradient updates remain balanced—overshooting or undershooting the minima diminishes the benefits of selective focus on noisy frames.

Finally, shuffling data every epoch is key to robust training under noisy conditions. Without shuffling, the MSE rises to 0.000780 and the SNR declines to 31.217954 dB. Restoring the baseline of per-epoch shuffling yields MSE 0.000662 and SNR 31.797619 dB, reinforcing that randomized data order fosters better exploitation of attention, as it consistently encounters diverse noise events in various orders.

Across all parameter variations, the attention mechanism remains integral to the Enhanced LSTM’s ability to pinpoint and suppress transient interference. By assigning weights to noisy frames and maintaining low-noise sections, the network adapts more effectively to fluctuating signal conditions than standard LSTM approaches. Although each parameter—such as optimizer choice or learning rate—plays a distinct role in shaping final performance, the unified effect of attention-driven hidden state weighting is most evident when the network is properly tuned (e.g., Adam optimizer, 50 epochs, mini-batch size 32, learning rate 0.001). This synergy confirms that selectively focusing on high-noise segments is a critical component of robust noise reduction.

Overall, the ablation study validates that Adam with 50 training epochs, a mini-batch size of 32, an initial learning rate of 0.001, and data shuffling each epoch yield optimal results for the Enhanced LSTM. Moreover, the integration of an attention mechanism significantly amplifies these gains by emphasizing critical time frames carrying excessive noise. Such an approach enables the model to outperform simpler LSTM variants and underscores the importance of carefully balancing training strategies, hyperparameters, and attention-based selective focus for complex signal processing tasks.

Conclusion

This study comparatively evaluated five algorithms—Least Mean Squares (LMS), Recursive Least Squares (RLS), Kalman Filter, a baseline Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and an Enhanced LSTM incorporating an attention mechanism—on the task of noise elimination for simulated automotive wheel speed sensor signals. The results confirm several key points:

-

1.

Superior performance of enhanced LSTM: The Enhanced LSTM consistently outperformed all alternative methods across six major metrics (MSE, RMSE, SNR, MAE, PSNR, and RRR). Its pronounced advantage stems from the integrated attention mechanism and carefully optimized training parameters, enabling the network to robustly isolate transient noise while preserving crucial low-frequency rotational characteristics. These findings highlight the high efficacy of advanced deep learning solutions for complex signal recovery under substantial interference.

-

2.

Efficacy of deep learning models: Even the baseline LSTM, absent specialized attention layers, surpassed LMS, RLS, and Kalman Filter in most metrics, reinforcing the value of deep learning for processing sequential data. This advantage can be attributed to the LSTM’s capability to learn long-term dependencies and adapt to diverse noise profiles. However, the enhanced variant with attention showed that targeted focus on high-noise segments further improves accuracy and reliability, underscoring the potential for task-specific architectural refinements.

-

3.

Limitations of traditional algorithms: Although LMS and RLS offered moderate noise reduction, and Kalman Filter attained reasonable performance in some metrics, none matched the capabilities of the deep learning approaches. Traditional algorithms may require extensive parameter tuning or additional external knowledge for comparable results in high-noise contexts. This result suggests both opportunities for hybrid strategies and a need for continued research to refine classical methods for modern, complex signals.

-

4.

Role of signal analysis via VMD and HHT: Detailed time–frequency examination of the denoised outputs using Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) proved essential for evaluating residual noise distribution and assessing how effectively each algorithm retained the fundamental wheel speed frequency. Such analyses not only verified the Enhanced LSTM’s superiority but also provided insights into how transient noise components evolve over time and frequency, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of signal processing mechanisms.

-

5.

Ablation study insights: Further investigation of hyperparameters—such as the choice of optimizer, number of training epochs, mini-batch size, initial learning rate, and data shuffling—revealed the importance of meticulous tuning in fully realizing the benefits of the attention-based architecture. The best overall results arose from Adam optimization, 50 training epochs, a batch size of 32, an initial learning rate of 0.001, and consistent data shuffling each epoch.

These findings underscore the potential of attention-augmented LSTM models for precision noise elimination in automotive wheel speed sensing and related domains. Future work could explore diverse network architectures, advanced attention mechanisms (e.g., self-attention or hierarchical attention), and alternative signal analysis methods (such as wavelet transforms or adaptive decomposition) to further enhance denoising capabilities. Studies addressing real-world datasets with non-stationary noise, sensor drift, or variable operating conditions will validate the framework’s robustness and broaden its applicability. Additionally, combining deep learning solutions with conventional algorithms may yield hybrid approaches that capitalize on the strengths of both paradigms, potentially offering even more reliable solutions for complex signal processing tasks.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript files. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Changhua University of Education, Graduate Institute of Vehicle Engineering, Electric Vehicle and Autonomous Driving Laboratory, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. However, the data can be obtained from Shih-Lin Lin upon reasonable request and with the permission of the National Changhua University of Education, Graduate Institute of Vehicle Engineering, Electric Vehicle and Autonomous Driving Laboratory.

References

Schreiber, T. & Grassberger, P. A simple noise-reduction method for real data. Phys. Lett. A 160(5), 411–418 (1991).

Schreiber, T. Extremely simple nonlinear noise-reduction method. Phys. Rev. E 47(4), 2401 (1993).

Schwarz, R., Nelles, O., Scheerer, P. & Isermann, R. Increasing signal accuracy of automotive wheel-speed sensors by online learning. In Proceedings of the 1997 American Control Conference (Cat. No. 97CH36041) Vol. 2, 1131–1135 (IEEE, 1997).

Magnusson, M. & Trobro, C. Improving wheel speed sensing and estimation. MSc Thesis (2003).

Hernández, W. Improving the response of a wheel speed sensor using an adaptive line enhancer. Measurement 33(3), 229–240 (2003).

Hernandez, W. Improving the response of a wheel speed sensor by using frequency-domain adaptive filtering. IEEE Sens. J. 3(4), 404–413 (2003).

Hernandez, W. Improving the response of a wheel speed sensor by using a RLS lattice algorithm. Sensors 6(2), 64–79 (2006).

Hernandez, W. Improving the response of a load cell by using optimal filtering. Sensors 6(7), 697–711 (2006).

Bentler, R. & Chiou, L. K. Digital noise reduction: An overview. Trends Amplif. 10(2), 67–82 (2006).

Li, K., Misener, J. A. & Hedrick, K. On-board road condition monitoring system using slip-based tyre-road friction estimation and wheel speed signal analysis. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi Body Dyn. 221(1), 129–146 (2007).

Vaseghi, S. V. Advanced Digital Signal Processing and Noise Reduction (John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

Yoshizawa, T., Hirobayashi, S. & Misawa, T. Noise reduction for periodic signals using high-resolution frequency analysis. EURASIP J. Audio Speech Music Process. 2011, 1–19 (2011).

Ramli, R. M., Noor, A. O. A. & Samad, S. A. A review of adaptive line enhancers for noise cancellation. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 6(6), 337–352 (2012).

Dadashnialehi, A., Bab-Hadiashar, A., Cao, Z. & Kapoor, A. Intelligent sensorless ABS for in-wheel electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 61(4), 1957–1969 (2013).

Liqiang, W., Hui, M. & Zongqi, H. Fast Fourier transformation processing method for wheel speed signal. Am. J. Eng. Res. 3, 35–42 (2014).

Tuma, J. Vehicle Gearbox Noise and Vibration: Measurement, Signal Analysis, Signal Processing and Noise Reduction Measures (John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

Waugh, W., Allen, J., Wightman, J., Sims, A. J. & Beale, T. A. Novel signal noise reduction method through cluster analysis, applied to photoplethysmography. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2018, 6812404 (2018).

Kim, H. S., Cho, J. R. & Han, S. R. Development of automobile wheel speed sensor using the injection molding by lifting the insert parts. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 41, 1–14 (2019).

Kang, B., Ahn, H. & Choo, H. A software platform for noise reduction in sound sensor equipped drones. IEEE Sens. J. 19(21), 10121–10130 (2019).

Ding, X., Wang, Z., Zhang, L. & Wang, C. Longitudinal vehicle speed estimation for four-wheel-independently-actuated electric vehicles based on multi-sensor fusion. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 69(11), 12797–12806 (2020).

Fariña, B., Toledo, J., Estevez, J. I. & Acosta, L. Improving robot localization using doppler-based variable sensor covariance calculation. Sensors 20(8), 2287 (2020).

Kelemenová, T., Benedik, O. & Koláriková, I. Signal noise reduction and filtering. Acta Mechatron. 5, 29–34 (2020).

Wang, X. L. et al. Time-domain signal reconstruction of vehicle interior noise based on deep learning and compressed sensing techniques. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 139, 106635 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Noise reduction of LiDAR signal via local mean decomposition combined with improved thresholding method. IEEE Access 8, 113943–113952 (2020).

Prajapati, P. H. & Darji, A. D. FPGA implementation of MRMN with step-size scaler adaptive filter for impulsive noise reduction. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 39, 3682–3710 (2020).

Ormiston, R., Nguyen, T., Coughlin, M., Adhikari, R. X. & Katsavounidis, E. Noise reduction in gravitational-wave data via deep learning. Phys. Rev. Res. 2(3), 033066 (2020).

Ga, H. S. & Kang, J. Y. Tire dynamic rolling radius compensation algorithm based on ax sensor offset estimation for i-TPMS. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 22, 1579–1587 (2021).

Zhan, X., Mu, Z. H., Kumar, R. & Shabaz, M. Research on speed sensor fusion of urban rail transit train speed ranging based on deep learning. Nonlinear Eng. 10(1), 363–373 (2021).

Lin, S. L. & Wu, B. H. Application of Kalman filter to improve 3d lidar signals of autonomous vehicles in adverse weather. Appl. Sci. 11(7), 3018 (2021).

Abdulkareem, A. Q., Humod, A. T. & Ahmed, O. A. Robust pattern recognition based fault detection and isolation method for ABS speed sensor. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 23(6), 1747–1754 (2022).

Park, Y. S., Cho, M. H., Oh, C. S. & Kang, Y. J. Coherence-based sensor set expansion for optimal sensor placement in active road noise control. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 169, 108788 (2022).

Spinosa, E. & Iafrati, A. A noise reduction method for force measurements in water entry experiments based on the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 168, 108659 (2022).

Brandt, A. Noise and Vibration Analysis: Signal Analysis and Experimental Procedures (John Wiley & Sons, 2023).

Khan, D. & Burdzik, R. Measurement and analysis of transport noise and vibration: A review of techniques, case studies, and future directions. Measurement 220, 113354 (2023).

Cha, Y. J., Mostafavi, A. & Benipal, S. S. DNoiseNet: Deep learning-based feedback active noise control in various noisy environments. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 121, 105971 (2023).

Li, X., Zhang, W., Li, X. & Hao, H. Partial domain adaptation in remaining useful life prediction with incomplete target data. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron. 11(3), 1903–1913 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Dynamic vision enabled contactless cross-domain machine fault diagnosis with neuromorphic computing. IEEE CAA J. Autom. Sin. 11(3), 788–790 (2024).

Zhang, W., Hao, H. & Zhang, Y. State of charge prediction of lithium-ion batteries for electric aircraft with swin transformer. IEEE CAA J. Autom. Sin. https://doi.org/10.1109/JAS.2023.124020 (2024).

Peng, D., Smith, W. A., Randall, R. B., Peng, Z. & Mechefske, C. K. Speed estimation in planetary gearboxes: A method for reducing impulsive noise. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 159, 107786 (2021).

Jin, L. et al. Robust algorithm of indirect tyre pressure monitoring system based on tyre torsional resonance frequency analysis. J. Sound Vib. 538, 117198 (2022).

Zhang, C., Shen, S., Huang, H. & Wang, L. Estimation of the vehicle speed using cross-correlation algorithms and MEMS wireless sensors. Sensors 21(5), 1721 (2021).

Nagaraju, D., Sharan, P., Sharma, S. & Chakraborty, S. Real-time implementation of optical sensor on lab rig model for speed estimation. J. Opt. 53(3), 2460–2468 (2024).

La, T. K. & Kwon, S. D. Reducing ambient sensor noise in wind tunnel tests using spectral subtraction method. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 244, 105631 (2024).

Pandharipande, A. et al. Sensing and machine learning for automotive perception: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 23(11), 11097–11115 (2023).

Jaros, R. et al. Advanced signal processing methods for condition monitoring. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30(3), 1553–1577 (2023).

Zhao, T., Ding, W., Huang, H. & Wu, Y. Adaptive multi-feature fusion for vehicle micro-motor noise recognition considering auditory perception. Sound Vib. 57, 133–153 (2023).

Cha, Y. J., Ali, R., Lewis, J. & Büyükӧztürk, O. Deep learning-based structural health monitoring. Autom. Constr. 161, 105328 (2024).

Ding, J., Wang, Y., Qin, Y. & Tang, B. Deep time–frequency learning for interpretable weak signal enhancement of rotating machineries. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 124, 106598 (2023).

Hassani, S. Meta-model structural monitoring with cutting-edge AAE-VMD fusion alongside optimized machine learning methods. Struct. Health Monit. https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217241263954 (2024).

Zhang, S., Liang, X., Shi, L., Yan, L. & Tang, J. Research on narrowband line spectrum noise control method based on nearest neighbor filter and BP neural network feedback mechanism. Sound Vib. 57, 29–44 (2023).

Yu, Y., Si, X., Hu, C. & Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 31(7), 1235–1270 (2019).

Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D 404, 132306 (2020).

Schmidhuber, J. & Hochreiter, S. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9(8), 1735–1780 (1997).

Graves, A. Generating sequences with recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.0850 (2013).

Bahdanau, D. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473 (2014).

Luong, M. T. Effective approaches to attention-based neural machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.04025 (2015).

Niu, Z., Zhong, G. & Yu, H. A review on the attention mechanism of deep learning. Neurocomputing 452, 48–62 (2021).

Ranjbarzadeh, R. et al. Brain tumor segmentation based on deep learning and an attention mechanism using MRI multi-modalities brain images. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–17 (2021).

UrRehman, Z. et al. Effective lung nodule detection using deep CNN with dual attention mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 3934 (2024).

de Santana Correia, A. & Colombini, E. L. Attention, please! A survey of neural attention models in deep learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55(8), 6037–6124 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. AttentionMGT-DTA: A multi-modal drug-target affinity prediction using graph transformer and attention mechanism. Neural Netw. 169, 623–636 (2024).

Xu, H. W., Qin, W., Sun, Y. N., Lv, Y. L. & Zhang, J. Attention mechanism-based deep learning for heat load prediction in blast furnace ironmaking process. J. Intell. Manuf. 35(3), 1207–1220 (2024).

Islam, S. et al. A comprehensive survey on applications of transformers for deep learning tasks. Expert Syst. Appl. 241, 122666 (2024).

Dragomiretskiy, K. & Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 62(3), 531–544 (2013).

ur Rehman, N. & Aftab, H. Multivariate variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 67(23), 6039–6052 (2019).

Huang, N. E. & Wu, Z. A review on Hilbert-Huang transform: Method and its applications to geophysical studies. Rev. Geophys. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007RG000228 (2008).

Huang, N. E. Hilbert-Huang Transform and its Applications Vol. 16 (World Scientific, 2014).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, for financially supporting this research (grant no. NSTC 113-2221-E-018-011) and Ministry of Education’s Teaching Practice Research Program, Taiwan, (PSK1134099).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-L.L.; methodology, S.-L.L.; sofware S.-L.L.; validation, S.-L.L.; resources, S.-L.L.; data curation, S.-L.L.; writing-original draf preparation, S.-L.L.; writing-review and editing, S.-L.L.; visualization, S.-L.L.; supervision, S.-L.L.; project administration, S.-L.L.; funding acquisition, S.-L.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, SL. Advancements in noise reduction for wheel speed sensing using enhanced LSTM models. Sci Rep 15, 21190 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07924-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07924-4