Abstract

China’s national parks are notably complex in global destination image building due to the “ecological protection first” principle, community embeddedness, and multi-stakeholder participation. Using Wuyishan National Park as a case, this study integrates text mining and grounded theory to examine: (1) destination image stakeholders, (2) interest-driven representation mechanisms, (3) systemic perception disparities, and (4) coordinated optimization pathways. The study reveals that tourists have a profound natural landscape experience but superficial cultural perception, and are sensitive to costs and management issues; residents benefit from tourism but are troubled by regional imbalances and lifestyle restrictions; enterprises seek economic benefits yet face policy constraints; the government emphasizes ecological protection and systematic governance; and non-profit organizations focus on ecological and cultural protection but are resource-constrained. This study develops a comprehensive evaluation method that integrates the perspectives of all stakeholders. Theoretically, it enriches the theoretical system of national park destination images and offers new research angles and empirical supplements to the literature. Practically, it provides collaborative image management paths for Wuyishan and experience for global national parks to balance protection and utilization in destination image building and enhancement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National parks serve as critical global platforms for nature conservation and public tourism1. The construction of their destination image reflects both the balance between ecological value and social benefits2 and the complex interplay of multi-stakeholder value participation3. Since the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, over 200 countries and regions have developed national parks, with tourism becoming a management objective for more than 80% of them2. Tourism enhances government revenue, improves park infrastructure, and stimulates local economies4. A well-crafted destination image attracts tourists and fosters tourism growth5. However, strategies for enhancing destination images vary across national parks due to differences in natural, political, and economic contexts6. For instance, Yosemite National Park in the United States reinforces its "symbol of American spirit" image through visual symbolism, cultural experiences, and brand collaborations7. South Africa’s uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Park integrates natural heritage, cultural assets, and community engagement to create a "trinity of ecology, culture, and economy" 8. Turkey’s Küre Mountains National Park strengthens its "Europe’s last primeval forest" identity via ecotourism and community empowerment9. Nevertheless, national park management involves diverse stakeholders3, and conflicting interests among them may lead to fragmented destination images10 and exacerbated conservation-utilization imbalances11. For example, Yellowstone National Park has been criticized as a product of colonial violence due to forced indigenous displacement12. The Lake District National Park in the UK prioritized preserving “cultural landscapes” by maintaining traditional sheep farming, resulting in vegetation degradation, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss13. Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park faces severe coral damage from tourist activities14. These issues not only harm destination images but also reveal the limitations of single-stakeholder dominance in image construction, underscoring the urgency of multi-stakeholder research on national park destination images.

Compared to other countries, China’s national park development commenced relatively late. The nation launched pilot reforms for its national park system in 2015 and officially established five national parks in 2021. While fewer in number, these parks encompass extensive geographical areas15 and contain substantial resident communities within their boundaries16. Tourism development in these parks strictly adheres to the principle of "ecological protection first"17, institutionalizes multi-stakeholder participation through enterprise concession operations and community engagement mechanisms18, and concurrently bears responsibilities for economic development and livelihood improvement19. Consequently, China’s national parks exhibit unique characteristics distinct from those of any other nation. On the one hand, existing destination image enhancement practices from global national parks offer valuable references for China, yet cannot be directly replicated. On the other hand, conflicts arising from divergent stakeholder interests in other countries’ parks demand vigilance as cautionary examples for China’s national park management.

Against this backdrop, this study addresses the following research questions: Who are the core stakeholders involved in constructing China’s national park destination image? How do stakeholder demands influence the representation of destination image? Do systematic differences exist in destination images across multi-stakeholder perspectives? How can interest coordination mechanisms balance diverse demands to enhance China’s national park destination image? Taking Wuyishan National Park as a case study, this research collects and analyzes online tourist reviews and government-published materials to uncover tourists’ and governmental perceptions of the park’s destination image. Concurrently, it decodes cognitive perspectives on the destination image from residents, businesses, and non-profit organizations through interview data. By comparing the cognitive frameworks of these five stakeholder groups toward the national park’s destination image, we identify both shared understandings and divergences, ultimately proposing actionable strategies to optimize Wuyishan National Park’s destination image. Scientific contributions lie in two dimensions: First, by integrating stakeholder theory into national park image research, this study expands the theoretical boundaries of destination image studies. Second, the methodological framework developed for measuring national park destination images offers transferable insights for global counterparts. From a practical value perspective, this study provides collaborative management pathways for China’s national parks, particularly Wuyishan National Park, to harmonize destination image development, while offering global insights into balancing conservation with sustainable utilization in constructing national park destination identities.

Literature review

Image is recognized as "the final outcome of the interplay between people’s beliefs, thoughts, emotions, and impressions about an object"20. Hunt21 pioneered the concept of destination image, which Crompton later defined as "the sum of beliefs, ideas, and impressions an individual holds about a destination."22 Baloglu and McCleary’s conceptual framework of cognitive image (knowledge and beliefs about destination attributes) and affective image (emotional evaluations of a destination’s merits or shortcomings) remains the most widely adopted model in destination image studies23. However, this framework predominantly focuses on tourists, with limited exploration of cognitive-affective images from other stakeholders. To address this gap, Grosspietsch redefined destination images from a stakeholder perspective, distinguishing between perceived image (tourists’ aggregated perceptions, attitudes, and evaluations) and projected image (the image destination managers intend to cultivate)24. This shift expanded research beyond tourist-centric perspectives, prompting investigations into images held by governments25, residents26, businesses27, and other stakeholders. Building on this, emerging studies compare tourist-perceived and government-projected images to optimize destination marketing28.

Stakeholders are defined as "any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of an organization’s objectives"29. As a theoretical framework emphasizing multi-party interest balance, stakeholder theory has been widely applied to national park management studies30,31,32. Key stakeholders in national parks include tourists33, residents34 , businesses35, governments36 , and non-profit organizations37. Tourists, as core stakeholders, drive management decisions through their diverse expectations, prompting authorities to strategically showcase resources, develop tourism activities, and improve facilities38. While tourist expenditures generate revenue for park maintenance, they simultaneously impose ecological pressures39. Residents, another critical stakeholder group, experience dual impacts: tourism boosts local incomes40 but may escalate living costs and disrupt traditional social structures41. Their cultural traditions and participatory governance enhance policy relevance to local realities42. Businesses contribute capital and operational expertise to improve service quality30,43, yet risk ecological harm through overdevelopment44. Governments play a central role by: Establishing policy frameworks for park development and conservation; Allocating funds for infrastructure, ecological restoration, and scientific monitoring45; Enforcing laws against ecological violations46; Facilitating cross-sector collaboration through coordination platforms47. Non-profit organizations uniquely support parks through fundraising, scientific research, and public education48. Divergent stakeholder objectives—tourists seeking experiences, residents prioritizing livelihoods, businesses pursuing profits, governments balancing conservation and development, and non-profits advancing public goods—often lead to image fragmentation49 and resource allocation conflicts50. These challenges highlight the need for multi-stakeholder co-governance, an innovative mechanism emphasizing collaborative participation to enhance governance effectiveness51. By harmonizing diverse demands and leveraging comparative advantages52, this approach improves the scientific rigor, democratic legitimacy, and operational efficacy of national park destination image construction.

Building upon the multi-stakeholder co-governance framework, destination image construction necessitates systematic measurement of images held by diverse stakeholders. Destination image measurement methodologies are broadly categorized into structured measurement (quantitative tools) and unstructured measurement (qualitative approaches), with increasing adoption of hybrid methods5. Structured measurement employs predefined quantitative instruments such as Semantic Differential Scales and Likert scales to quantify stakeholder perceptions across predetermined dimensions. Unstructured measurement encompasses text analysis (e.g., social media comment mining), visual content analysis (e.g., photograph theme identification), and open-ended interviews to capture spontaneous perceptual expressions. Current practices predominantly analyze stakeholder-held destination images through the cognitive-affective image framework: Cognitive image is measured via web text analysis53, visual data analytics54, and grounded theory coding55. Affective image is assessed using affective scales56 or emotional metaphor identification in interview transcripts57. Technological advancements have introduced novel computational approaches: lexicon-based methods58, deep learning models59, and multimodal analysis60 now enable large-scale affective image measurement.

While existing studies provide valuable foundations, three critical limitations persist: (1) Research related to the destination image of national parks is very limited. A globally recognized conceptualization of national park destination images remains absent. Current research predominantly applies generic tourism destination image frameworks to national parks, focusing on economic optimization to increase tourist numbers61. This approach overlooks the fundamental distinction between national parks and conventional tourism destinations—the non-negotiable mandate of "ecological protection first" that rigidly constrains image construction. (2) Overreliance on single-stakeholder perspectives. Studies disproportionately concentrate on tourist perceptions, with limited investigations into other stakeholders: residents62, businesses/employees63, and governments64. Crucially, non-profit organizations’ perspectives on national park images remain virtually unexplored. (3) Lack of integrative evaluation methodologies. Despite stakeholders’ divergent interests and cognitive lenses shaping distinct image perceptions, no comprehensive methodology currently exists to systematically integrate multi-stakeholder perspectives in national park image evaluation. This gap hinders inclusive consideration of diverse viewpoints during image construction and enhancement processes.

Study area

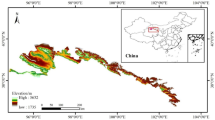

Wuyishan National Park is situated along the Fujian-Jiangxi border, spanning geographical coordinates 117° 24′ 15′′–117° 59′ 33′′ E and 27° 31′ 21′′–28° 02′ 53″ N, with a total area of 1,279.82 km2. Administratively, it encompasses 9 towns across four Fujian counties/cities (Wuyishan City, Jianyang District, Guangze County, and Shaowu City in Nanping Prefecture) and 3 towns in Jiangxi’s Yanshan County (Fig. 1). The park contains 29 natural villages with 341 registered households and a population of 3,414, predominantly Han Chinese, alongside the She ethnic minority.

Ecologically, Wuyishan National Park lies within the central subtropical monsoon climate zone, serving as the headwater for the Min River and Xinjiang River Basin of Poyang Lake. Its Danxia landform-dominated terrain boasts 94.5% forest coverage, safeguarding the world’s largest and most intact mid-subtropical forest ecosystem at this latitude. The natural landscape encompasses four hierarchical levels: 4 major categories (geography, hydrology, biology, meteorology), 15 subcategories, and 32 basic types. The humanistic landscape features cultural heritage elements including Minyue culture (an ancient Baiyue subgroup), Zhuzi culture (Neo-Confucian philosophy), tea traditions, religious practices, and folk customs. This integrated configuration qualifies it as a UNESCO(United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage Site possessing exceptional tourism perceptual qualities. Management-wise, Wuyishan National Park implements zonal governance: Core conservation zones prioritize ecological protection. General control zones permit scientific education and tourism activities. Eight major tourist areas operate within Wuyishan National Park: the Main Scenic Area, Da’anyuan, Wuyiyuan, Yulong Valley, Qinglong Waterfall, Grand Canyon Ecological Park, Shibazhai, and Longchuan, employing over 1,600 staff. During October 1–7, 2024, the park recorded 264,600 visits (daily average: 37,800), demonstrating robust tourism growth compared to other Chinese national parks.

Under China’s Master Plan for Establishing the National Park System and institutional reform policies, the National Park Administration oversees unified management and top-level design at the central government level. At the local level, the Wuyishan National Park Administration Bureau manages ecological conservation and resource protection, while the Wuyishan Municipal Bureau of Culture, Sports, and Tourism governs tourism operations. Economic activities in and around Wuyishan National Park primarily derive from tea production, moso bamboo cultivation, migrant labor, and ancillary industries. The park implements concession operations for commercial projects involving resource management, including Jiuqu Stream Bamboo raft tours, electric sightseeing vehicles, and rafting activities. The Wuyishan National Park Administration Bureau enforces regulatory oversight of concession operators while actively encouraging qualified local residents to participate. Over 1,200 villagers are directly employed in park operations as tour guides, bamboo raft operators, sanitation staff, and green space maintenance personnel.

Wuyishan National Park was selected as the study case due to its multidimensional exemplary value and research suitability. Firstly, as China’s sole UNESCO World Heritage Site (Mixed Cultural and Natural) preserving an intact mid-subtropical forest ecosystem, it offers irreplaceable scientific value at its latitude, serving as an ideal prototype for studying ecological conservation-tourism synergies. Secondly, its distinctive Danxia landform landscapes, Zhuxi Culture heritage, and tea-tourism integrated industries have forged a recognizable cultural tourism brand, attracting substantial domestic and international tourist flows that provide a rich data pool for destination image analysis. Crucially, Wuyishan National Park has pioneered systematic innovations in multi-stakeholder co-governance models, making it a critical site for investigating interest conflicts. This positions it as a paradigmatic case for decoding China’s national park image construction through stakeholder lenses, yielding nationally representative and globally referential insights.

Methodology

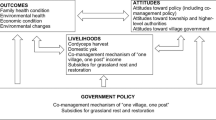

The construction of China’s national park destination image should aim to maximize the goals of all stakeholders. However, numerous conflicts arise in practice. Under the principles of ecological protection and livelihood improvement, balancing stakeholder objectives becomes a critical means to advance the construction and dynamic development of national park destination images. This study established a methodological framework for analyzing China’s national park destination images, using Wuyishan National Park as a case study. The key steps were as follows (Fig. 2): ① Based on the "perception-projection" image theory, stakeholder theory, and "cognitive-affective" model, we constructed a three-dimensional analytical framework for Wuyishan National Park’s destination image from a multi-stakeholder perspective. ② We collected data on stakeholders’ perceptions of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image through online reviews and semi-structured interviews. ③ Data preprocessing was conducted using text analysis techniques to: extract high-frequency keywords, establish attribute categories, generate semantic network diagrams, and quantify textual sentiment. Simultaneously, grounded theory analysis was employed to: perform three-level coding (open/axial/selective), develop attribute categories, analyze textual sentiment. This process yielded Wuyishan National Park’s destination image from each stakeholder perspective, comprising cognitive image (knowledge structure) and affective image (emotional evaluations). ④ Guided by stakeholder theory and the cognitive-affective image framework, we conducted comparative analyses between perceived images (held by tourists/residents/businesses/non-profits) and projected images (held by governments) through three dimensions: cognitive image (focused on destination attractions and key concerns), affective image (centered on stakeholder attitudes), interest demands. Under the multi-party co-governance model, we balanced stakeholder objectives, concretized key factors influencing destination image, and proposed optimization strategies for Wuyishan National Park.

Construction of the three-dimensional analytical framework for national park destination image

We established a three-dimensional analytical framework for national park destination image (Fig. 3) through three integrated perspectives: perceived vs. projected image comparative analysis, stakeholder theory, and cognitive-affective model. This framework identified optimization pathways to maximize destination image value. Specifically: stakeholder theory provided multi-agent perspectives for analyzing image construction; cognitive-affective model refined understanding of destination images held by individual stakeholders; perception-projection framework revealed discrepancies between stakeholder-held images, thereby exposing conflicts and synergies. Wuyishan National Park’s destination image construction was intrinsically linked to stakeholder objectives, which were categorized into three macro-groups: government actors, market actors (businesses); societal actors (residents, non-profits, tourists). Guided by the perception-projection theory, we analyzed: perceived images (tourist-dominated demand-side perspectives); projected images (supply-side perspectives from other stakeholders). Through tripartite comparison of cognitive image, affective image, and interest demands, we diagnosed "alignment-misalignment" patterns, identified root causes of discrepancies, and proposed multi-stakeholder co-governance strategies to harmonize objectives and enhance destination image.

Data sources

To systematically evaluate the current state of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image, this study collected multi-stakeholder perspectives on the park’s image. Leveraging the rapid development of digital media, online reviews serve as a primary data source for tourists’ perceived image, reflecting tourists’ beliefs and perceptions. Online reviews offer advantages in sample size, coverage breadth, and accessibility65. Government perspectives can be derived from official documents and promotional materials, which are also accessible through media data. However, media data do not comprehensively cover all stakeholder perspectives. Beyond tourists and governments, views from other stakeholders (e.g., residents, businesses, non-profits) are unavailable through public channels and require direct engagement. While questionnaires risk researcher bias and overlook critical information due to predetermined structures66, this study employed semi-structured interviews to holistically capture these stakeholders’ perspectives on Wuyishan’s destination image.

Online review data were collected from major Chinese travel platforms. Market share analysis reveals Ctrip dominated with an average 35.04% share over the past three years, followed by Meituan (14.3%), Qunar (15.9%), and Tongcheng Travel (11%). In terms of monthly active users (MAU), Ctrip ranked first in 2021 with 71.7 million MAU, followed by 12306 Railway, Tongcheng Travel, Meituan, and Qunar. Based on platform content comparability, data accessibility, and review volume, we selected Ctrip, Qunar, and Meituan as representative platforms. Using the web scraping tool Octoparse, we extracted tourist reviews from Wuyishan National Park’s comment pages dated September 24, 2022, to September 24, 2023. Data were filtered through three criteria: ①Content validity: Reviews exceeding 20 Chinese characters. ②Uniqueness: Removal of duplicate or invalid entries with extensively copied content. ③Relevance: Exclusion of advertisements and general introductions to minimize bias. After processing, 2,188 valid entries were retained, comprising 659 from Ctrip, 767 from Qunar, and 762 from Meituan, totaling over 400,000 Chinese characters.

Government data were sourced from Chinese policy documents including the Master Plan for Establishing the National Park System and Wuyishan National Park Master Plan (2023–2030), as well as 571 articles (totaling over 1.3 million Chinese characters) published between September 24, 2022, and September 24, 2023, through official channels such as the website of China’s National Forestry and Grassland Administration and WeChat official accounts ("Wuyishan National Park", “Wuyishan Tourism”, and “China Wuyishan”).

Semi-structured interview data were collected from 100 stakeholders, including 50 community residents (comprising both residents living within the tourism zones of Wuyishan National Park and those in surrounding areas influenced by park activities), 5 local government officials (from the Wuyishan National Park Administration Bureau and the Wuyishan Municipal Bureau of Culture, Sports, and Tourism), 40 tourism-related businesses (such as tourism development companies, shops in the park’s sole commercial street, hotels, restaurants, tea enterprises, and small businesses in peripheral areas), and 5 non-profit organization representatives (from the Wuyishan Municipal Museum and local subdistrict offices). The interviews, conducted from December 20 to 31, 2023, focused on two components: (1) respondents’ basic demographic information (gender, age, education level, and occupation) and (2) their perceptions of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image. Specifically, the interviews aimed to explore: the respondents’ relationship with the park, their cognitive understanding of its destination image, and their projected expectations for the park as a tourism destination. Guided by Creswell and Poth’s principles67, participants were encouraged to freely express their views within the research framework. Each interview lasted 30–60 min, with all sessions audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim to ensure data accuracy, resulting in over 450,000 Chinese characters of textual data for analysis.

Data processing and image construction

Text analysis refers to the extraction of semantic meaning from textual data through machine learning and natural language processing algorithms, encompassing operations such as word frequency statistics, sentiment analysis, association mining, and complex frequency extraction. The ROST CM6 text analysis tool, initially introduced by Xiao and Zhao for destination image measurement68 and later validated by Wang et al. for its applicability in semantic network construction and sentiment analysis within destination image research69, was selected for this study to analyze the collected textual data. Prior to analysis, the data underwent preprocessing, including the correction of typographical errors and the standardization of synonymous proper nouns. To align with Wuyishan National Park’s contextual specificities, custom dictionaries were developed by incorporating the park’s major attractions, while stop-word lists were curated to filter out non-specific particles such as “了” (le) and “的” (de), thereby enabling precise feature selection through string matching and enhancing the recognition of destination-specific terminology. Finally, the TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) method was applied to vectorize textual data and extract destination image keywords, among which:

where \({TF}_{ij}=\frac{{n}_{ij}}{\sum_{k}{n}_{kj}}, {IDF}_{ij}={\mathit{log}}_{10}\frac{\left|D\right|}{1+\left|{D}_{ti}\right|}, {n}_{ij}\) represents the number of occurrences of the feature word \({ T}_{i}\) in the training text \({D}_{j}\), \(\sum_{k}{n}_{kj}\) indicates the number of all feature words in the text \({D}_{j}\), the parameter \(\left|D\right|\) represents the total number of texts in the corpus, and \(\left|{D}_{t}\right|\) refers to the number of feature words \({ T}_{j}\) contained in the text.

Building on this foundation, keywords from tourist reviews and government promotional texts were classified into four categories—destination attractions, destination environment, destination management/services, and destination experiences/evaluations—based on their semantic relevance to Beerli and Martin’s framework of destination image perception70. Subsequently, probabilistic topic models were employed to extract latent themes by analyzing word co-occurrence patterns at the document level71, generating semantic network diagrams that visually map lexical relationships. Core nodes and their interconnectivity within these networks were analyzed to identify dominant themes in both tourist and governmental discourses. Sentiment analysis was conducted through lexicon-based string matching integrated with weighting mechanisms72, which quantified sentiment polarity (positive/negative) by assigning weighted scores to emotional lexicons. This enabled systematic identification of strengths and weaknesses in Wuyishan National Park’s destination image.

Grounded theory, as a pivotal qualitative research method, employs a bottom-up inductive approach to collect data without pre-existing hypotheses, systematically identifying core concepts through the interplay of induction, deduction, and qualitative-quantitative integration73. Following this methodology, we conducted a three-stage coding process on interview transcripts after defining thematic foci and completing fieldwork: ①Open Coding involved extracting significant statements about Wuyishan National Park’s destination image from raw interview data. Concepts such as “natural landscapes,” “environmental quality,” “land resources,” “cultural performances,” “historical-cultural resources” and “local characteristics” were identified and grouped into broader categories (e.g., “natural resources” and “cultural resources”) based on empirical patterns and research objectives. Tables 1, 2, and 3 present the open coding results for resident, business, and non-profit organization interviews, respectively. ②Axial Coding refined these categories by establishing interrelationships among concepts. For residents, 14 initial categories (e.g., natural resources, cultural resources, economic development, environmental awareness) were consolidated into five principal categories: destination resources, economic income, lifestyle, living environment, and community relations. Business interviews revealed three core dimensions: destination resources, economic benefits, and external regulation. Non-profit perspectives coalesced into four key themes: destination resources, ecological conservation, cultural heritage protection, and tourist needs. ③Selective coding involved identifying the core category of "Wuyishan National Park Destination Image" and systematically linking it to subsidiary categories while refining conceptual relationships and supplementing underdeveloped dimensions through iterative data screening. Residents’ perceptions of tourist activities in the park coalesced around 14 focal domains: natural resources, cultural resources, economic development, personal growth, environmental awareness, livelihood management, leisure satisfaction, community participation, residential environments, transportation infrastructure, public facilities, service quality, living costs, and community development. Businesses prioritized six key areas: natural resources, cultural resources, profitability, land-use restrictions, operational constraints, and conflict resolution mechanisms. Non-profit organizations emphasized eight dimensions: natural resources, cultural resources, ecological conservation efficacy, protection measures, cultural preservation status, heritage revitalization progress, and tourist demand alignment. These stakeholder-specific insights culminated in three distinct destination image models: a resident-centric model integrating five dimensions (destination resources, economic income, lifestyle, living environment, and community relations); a business-oriented model comprising three aspects (destination resources, economic benefits, and external regulation); and a non-profit-focused model structured around four pillars (destination resources, ecological conservation, cultural heritage protection, and tourist needs).

Analysis and findings

Destination images held by stakeholders

Tourist-perceived image

Tourists’ cognitive understanding of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image primarily centers on four dimensions: destination attractions (58.66%), management/services (19.8%), experiential evaluations (14.11%), and environmental attributes (6.4%) (Table 6, see Appendix). Destination attractions, the dominant factor influencing visitation, are overwhelmingly shaped by natural landscapes, with Tianyou Peak, Jiuqu Stream, and Da Hong Pao Tea Gardens emerging as focal points (Fig. 4). Quantitative analysis reveals that 50.66% of tourist perceptions relate to natural resources, starkly overshadowing cultural resources (8.06%). While tourists widely acknowledge the uniqueness of Danxia landforms and aquatic landscapes, their engagement with cultural assets—such as Zhuxi Culture and tea traditions—remains superficial, reflecting the current dominance of sightseeing-oriented products over deeper cultural-tourism integration.

Management and services constitute another critical concern, particularly regarding tourism activities, facilities, and costs, which directly correlate with satisfaction levels. Notably, the recurrent mention of “protection” in tourist narratives signals an emerging awareness of ecological conservation, distinguishing national park tourism from conventional destinations. Experiential evaluations are predominantly positive, with commendatory terms such as "worthwhile," "convenient," "enjoyable," "beautiful," and “scenic” primarily concentrated in tourism resources, cost considerations, and facility attributes. Environmental perceptions, however, reveal a subtle discrepancy: while the park’s “Dual Heritage of Nature and Culture” branding resonates strongly in promotional materials, tourist perceptions remain skewed toward natural landscapes, underscoring a misalignment between projected and perceived cultural narratives.

In terms of affective image (Table 7, see Appendix), tourists predominantly expressed positive sentiments (77.64%), largely driven by admiration for the park’s pristine natural landscapes. Negative sentiments (21.15%) primarily centered on cost-related grievances—such as perceived ticket overpricing and unregulated rafting fees—and criticisms of park management and services, including inconsistent service standards and subpar service attitudes. Neutral sentiments (1.21%) were occasionally observed in discussions about itinerary planning, reflecting pragmatic rather than emotionally charged evaluations.

Resident-projected image

Residents’ perceptions of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image are structured around five dimensions: destination resources (40%), economic income (32%), lifestyle (13%), living environment (12%), and community relations (3%) (Table 8, see Appendix). Regarding destination resources, 95% of residents endorsed the symbolic representation of “One Mountain, One Water, One Impression”—referring to Tianyou Peak (“One Mountain”), Jiuqu Stream Bamboo Rafting (“One Water”), and the cultural performance Impression Da Hong Pao (“One Impression”). Additional sites such as Yanzike Ecological Tea Plantation (recommended by 40% of residents), Dawang Peak (25%), Yunü Peak (25%), and Longchuan Grand Canyon (10%) also garnered significant attention. The high endorsement of Yanzike reflects residents’ livelihood reliance on tea cultivation and cultural affinity, while Longchuan’s prominence as a local leisure destination contrasts with its lower visibility among tourists. Natural resources dominated recommendations (83%), overshadowing cultural assets (17%), indicating underdeveloped heritage promotion. Tourism development has broadly enhanced employment opportunities and household incomes. Concurrently, economic gains have incentivized governmental investments in environmental upgrades, improving residential infrastructure and public services. However, the park’s ecological protection mandate has introduced lifestyle constraints, including road access restrictions and managed entry/exit protocols for residents. Community relations have emerged as a critical concern. Asynchronous tourism development across neighborhoods—exemplified by nighttime lighting disparities between Xingcun Town and Sangu Village—has exacerbated regional development imbalances. Differential access to tourism benefits has further fueled perceptions of inequity among residents, with some households capitalizing on entrepreneurial opportunities while others face marginalization.

Affective Image Analysis (Table 9, see Appendix) reveals residents’ predominantly positive sentiments (81%), rooted in perceived improvements in economic income, employment opportunities, infrastructure development, and recreational access, alongside strengthened cultural identity. However, negative sentiments (19%) stem from grievances over living inconveniences, rising costs, and frustrations with regional and individual development disparities, compounded by safety concerns regarding steep terrain hazards within the park.

Business-projected image

Enterprises’ perceptions of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image concentrate on three dimensions: destination resources (38%), economic benefits (54%), and external regulation (8%) (Table 10, see Appendix). Within destination resources, tea culture is unanimously recognized as a distinctive feature beyond the branding of "One Mountain, One Water, One Impression" and the distinctive natural environment. Enterprises emphasize the coordinated value between tea culture and natural landscapes, aligning with both commercial priorities and the region’s tea-centered pillar industry. Notably, 43% of surveyed enterprises report insufficient representation of non-tea cultural elements in tourism activities. Driven by profit-seeking motives and the tourism multiplier effect, enterprises broadly acknowledge current or anticipated economic gains from tourism. Simultaneously, operations face external regulation—including strict prohibitions on illegal tea plantation expansion for environmental protection. Key regulatory concerns encompass power supply restrictions in scenic areas and dispute resolution mechanisms tilted toward tourists.

Affective Image Analysis (Table 11, see Appendix) indicates that 68% of businesses expressed positive sentiments, primarily as beneficiaries of economic gains from tourism development. Neutral sentiments (18%) were observed among enterprises yet to realize direct financial benefits but maintaining optimism about future prospects. Negative sentiments (14%) stemmed from regulatory constraints, such as prohibitions on unauthorized tea plantation expansion within the park that limited profit opportunities for small-scale tea enterprises, alongside perceptions of dispute resolution mechanisms disproportionately favoring tourist interests at the expense of business autonomy.

Government-projected image

Governmental perceptions of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image are structured across four dimensions: destination attractions (41.38%), environmental attributes (25.83%), management/services (23.34%), and experiential evaluations (9.45%) (Table 12, see Appendix). Destination attractions dominate governmental promotional narratives, with natural resources referenced at a frequency 5.3 times higher than cultural resources. Distinct from other stakeholders’ site-specific focus (e.g., Tianyou Peak), the government emphasizes the park’s holistic ecosystem—integrating landscape features, flora, and fauna—as the core attraction. Environmental priorities extend beyond ecological metrics to encompass socio-cultural transformation, including tourism-driven economic growth, cultural revitalization, and societal value shifts. In destination management and services, terms such as "protection," "development," "construction," "innovation," "establishment," "high-quality," "collaboration," "participation," and “science popularization” indicate a governmental tendency toward high-quality service delivery. This approach relies on multi-stakeholder collaboration under ecological protection principles. Regarding experiential evaluations, high-frequency terms—including "civilization," "distinctive features," "safety," "tourists," "experience," "value," "public," and “beauty”—demonstrate an official aim for all individuals (both visitors and residents) to perceive scenic beauty, ensured safety, and civilized service standards. Social semantic network analysis (Fig. 5) reveals a concentric conceptual framework: ① core layer: natural ecology preservation and social benefit enhancement. ② secondary layer: cultural-historical conservation and economic development. ③ peripheral layer: destination attraction branding and cultural distinctiveness. This hierarchical model reflects the government’s strategic progression from ecological-social foundations to tourism identity construction.

Affective Image Analysis (Table 13, see Appendix) demonstrates that governmental discourse exhibits 41.71% positive sentiments, predominantly expressed through descriptors like "picturesque," "tranquil," "well-developed," "convenient," "welcoming," and “aesthetic” to portray destination attractions and management/services. Negative sentiments (8.86%) paradoxically emerge in poetic citations of scenic beauty, potentially reflecting rhetorical over-idealization. Neutral sentiments dominate at 49.43%, characterized by strategic verbs such as "centering on," "demonstrating," "implementing," "collaborating," and “constructing” that align with policy-driven narratives of destination planning and activity orchestration.

Non-profit-projected image

Non-profit organizations’ perceptions of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image concentrate on four dimensions: destination resources (20%), ecological conservation (35%), cultural heritage protection (30%), and tourist demand (15%) (Table 14, see Appendix).Within destination resources, beyond the "One Mountain, One Water, One Impression" branding, cultural assets comprise 47% of recommendations versus 53% for natural resources. This cultural emphasis is significantly higher than endorsement levels among other stakeholders, aligning with non-profits’ institutional attributes. Regarding ecological conservation linked to tourism, volunteer activities are organized to regulate tourist misconduct and promote environmental awareness. These efforts demonstrate documented effectiveness through synergy with stringent governmental controls. For cultural heritage protection, initiatives—including festivals, exhibitions, and lectures—highlight local cultural distinctiveness. Nevertheless, constraints in funding, talent, and resources hinder optimal conservation outcomes. Consequently, cultural resource revitalization remains challenging. To address tourist demand, community-led advisory services enhance visitor experiences while strengthening local cultural identity. This dual approach fosters unique community atmospheres that elevate the destination image.

Affective Image Analysis (Table 15, see Appendix) reveals that non-profits expressed 62% positive sentiments, primarily driven by endorsement of current ecological conservation measures and their tangible outcomes in Wuyishan National Park. Neutral sentiments (23%) centered on anticipatory confidence that cultural experience programs would expand as tourism development deepened. Negative sentiments (15%) stemmed from critiques of insufficient cultural activity integration, with non-profits contending that existing tourism practices underutilize the park’s potential for cultural dissemination and intercultural exchange, thereby limiting its role as a platform for heritage valorization.

Alignment-misalignment comparative analysis

Wuyishan National Park’s destination image exhibits both shared and divergent perceptions across stakeholders. Shared perceptions manifest in three key aspects: First, the symbolic representation of “One Mountain, One Water, One Impression” (Tianyou Peak, Jiuqu Stream, and Impression Da Hong Pao) dominates destination attraction narratives, rooted in the region’s unique resource endowments and tourism development strategies. Second, while abundant cultural resources exist, their utilization remains disproportionately low, with overdependence on natural landscapes’ visual appeal and insufficient investment in cultural narrative construction. Third, ecological protection consciousness permeates all stakeholders, attributable to the regulatory dynamics between governments (as supervisors) and other actors (as the regulated). Stringent governmental policies—such as activity restrictions and ecological redlines—have effectively institutionalized conservation awareness. Divergent perceptions, however, emerge in stakeholders’ prioritization of resource values, conflict resolution expectations, and benefit distribution frameworks, which will be analyzed in subsequent sections.

Divergent destination images arise from stakeholders’ distinct roles and interest demands in image construction, manifesting in cognitive and affective disparities (Table 4): Tourists, as end consumers of tourism products, prioritize cost-performance ratios shaped by experiential satisfaction versus expenditure. This ratio hinges on attractions, facilities, and service quality, making these their primary focus. While their positive sentiments dominate (77.64%) due to scenic enjoyment, high price sensitivity toward costs and management critiques sustain negative perceptions (21.15%). Residents, as critical participants through service provision, emphasize livelihood linkages—economic gains, living costs, cultural identity, and regional belonging. Yet, their ambivalence stems from constrained development rights under conservation mandates, with positive sentiments (81%) tempered by frustrations over restricted autonomy and inequitable benefit distribution. Businesses, as commercial providers, pursue profit maximization while navigating compliance costs from ecological regulations. Their positive sentiments (68%) reflect tourism-driven revenues, yet negative perceptions (14%) expose tensions between short-term profit motives and long-term conservation rigidities. Governments, as systemic regulators, prioritize holistic governance balancing ecological integrity, economic growth, and cultural revitalization. Their discourse emphasizes phased, conflict-minimizing strategies, reflected in neutral sentiments (49.43%) tied to policy implementation over emotive narratives. Non-profits, as heritage stewards, advocate cultural-ecological synergies through community engagement and educational programs. Despite 62% positive sentiments toward conservation outcomes, their marginalization due to funding constraints and limited market-driven sustainability mechanisms hinders cultural resource activation, sustaining critiques of underdeveloped heritage narratives. This multi-stakeholder tension matrix reveals Wuyishan’s destination image as a contested terrain where ecological imperatives, economic pragmatism, and cultural aspirations intersect yet frequently collide.

Divergent priorities among stakeholders in constructing Wuyishan National Park’s destination image engender latent conflicts in practice (Table 5). Government-business/resident tensions manifest as clashes between ecological conservation and economic interests, exemplified by strict governmental bans on unauthorized tea plantation expansions, which constrain business viability and resident livelihoods. Inter-community disparities arise from uneven tourism development timelines, creating core-periphery divides where prioritized zones (e.g., Xingcun Town) advance rapidly while marginalized areas (e.g., Sangu Village) lag. Government-tourist/resident policy rigidities emerge during peak seasons, as inflexible access regulations exacerbate tourist congestion and resident mobility restrictions, degrading travel experiences and daily convenience. Business-nonprofit/government sustainability conflicts reflect opposing temporal orientations: businesses prioritize short-term commercialization, often neglecting ecological-cultural safeguards, whereas nonprofits and governments advocate long-term preservation, resulting in underutilized cultural resources and diminished heritage valorization in tourism.

Discussion and conclusions

Discussion

Divergent destination images held by stakeholders in Wuyishan National Park fundamentally stem from their role positioning, interest demands, and cognitive frameworks—a finding consistent with stakeholder theory29 and destination image scholarship5, yet bearing unique implications in the national park context. Tourists, as experience consumers, exhibit strong natural landscape perceptions but minimal cultural engagement, mirroring Grosspietsch’s perception-projection disalignment24 and exposing the park’s superficial cultural-tourism integration, where the government-projected “Dual Heritage” narrative fails to translate into deep tourist experiences. Residents, as local participants, prioritize livelihood improvements and community equity, aligning with Allendorf et al.’s findings on “conservation-induced community marginalization.”34 In Wuyishan, residents’ eco-livelihood interdependencies—evidenced by a 40% endorsement rate for Yanzike tea attractions—intensify their sensitivity to policy rigidities (e.g., negative sentiments toward tea plantation bans). Businesses, driven by capital logic, face conflicts between short-term profit motives and conservation mandates, echoing Madhusudan and Mishra’s “enterprise-conservation goal misalignment.”74 The park’s underdeveloped cultural value realization exacerbates reliance on natural resources, perpetuating a low-value-added development cycle. Governments, as systemic regulators, reflect Lockwood et al.’s policy implementation gradient theory through neutral46, process-oriented discourse. However, their overwhelming emphasis on “ecological protection first” (35.28% natural resource mentions versus 6.1% cultural references) risks cultural marginalization. Non-profits, constrained by idealistic-resource paradoxes, validate Hasenfeld and Garrow’s nonprofit marginalization thesis75. While community empowerment initiatives (e.g., volunteer programs) attempt to circumvent resource limitations, absent market-driven sustainability mechanisms hinder cultural heritage activation.

This study systematically advances national park destination image research by adopting a multi-stakeholder analytical framework, contrasting with prior singular-focus approaches predominantly centered on tourists49. By integrating perspectives from residents, businesses, governments, and non-profits, it enriches theoretical paradigms and expands methodological boundaries, offering three key innovations: First, it empirically validates how role-based positioning and interest heterogeneity shape divergent cognitive-affective images among stakeholders, deepening stakeholder theory’s applicability in protected area governance. Second, it reconceptualizes projected image beyond governmental discourse to encompass supply-side projections from residents, businesses, and non-profits, thereby broadening the theory’s epistemological scope. Third, it proposes collaborative image management pathways for Wuyishan National Park while contributing globally transferable insights into balancing conservation-utilization tensions.

While this study provides valuable insights, its limitations stem primarily from China’s nascent national park system and associated data constraints. The relatively short operational history of these parks restricts access to longitudinal tourism data, precluding analysis of long-term stakeholder image evolution. Future research could employ dynamic analytical frameworks to examine how multi-stakeholder interactions co-shape destination images across different developmental phases of national parks. In addition, the selected data from online comments and interviews may be affected by sample bias, which may be solved by technological advancement in the future.

Conclusions

Wuyishan National Park’s destination image exhibits multidimensional characteristics, marked by both shared foundations and stakeholder-specific divergences in cognitive and affective perceptions. Natural resources dominate as the universal cognitive anchor across tourists, residents, businesses, governments, and non-profits, while cultural resource utilization remains underdeveloped, reflecting superficial cultural-tourism integration. Tourists demonstrate profound engagement with natural landscapes like the Danxia landform and Jiuqu Stream, yet their cultural perceptions remain shallow, coupled with heightened sensitivity to costs (e.g., rafting fees) and management irregularities, resulting in co-existing positive (77.64%) and negative (21.15%) sentiments. Residents benefit economically from tourism but harbor frustrations over regional development imbalances (e.g., nighttime infrastructure disparities) and livelihood constraints (e.g., restricted land use). Businesses, prioritizing profit maximization, face tensions between short-term gains and policy rigidities (e.g., compliance costs). Governments, adhering to the "ecological protection first" mandate, emphasize systemic governance and holistic benefits, with neutral sentiments (49.43%) reflecting incremental policy implementation. Non-profits, despite advocating ecological-cultural synergies, struggle with resource limitations that hinder heritage revitalization. Key conflicts manifest as: ①Ecological-economic trade-offs (e.g., tea plantation restrictions vs. livelihood needs). ②Policy rigidity-flexibility tensions (e.g., peak-season congestion vs. resident mobility). ③Short-term profit versus long-term sustainability dilemmas (e.g., rapid commercialization vs. cultural preservation). To reconcile these tensions, multi-stakeholder co-governance mechanisms76 should be institutionalized, fostering ecological prioritization alongside synergistic natural-cultural valorization. This approach would enable dynamic stakeholder equilibrium, positioning Wuyishan National Park to reach the goal of synergistic value-added of natural and cultural resources and a dynamic balance of interests of all parties.

This study transcends the traditional tourist-centric paradigm of destination image research by integrating Grosspietsch’s perception-projection framework into a unified analytical model23,24. For the first time, it systematically incorporates tourists’ perceived images with projected images from residents (place-based participants), businesses (commercial operators), governments (policy architects), and non-profits (public-good advocates), revealing how China’s “ecological protection first” mandate imposes institutionalized behavioral constraints across stakeholders. Empirical findings demonstrate that governmental conservation policies—such as tea plantation bans and mobility restrictions—permeate business operations and resident livelihoods while indirectly shaping tourists’ ecological consciousness (e.g., “protection” emerged as a high-frequency term in tourist discourse). This mechanistic analysis provides theoretical grounding for understanding the uniqueness of China’s national park image construction. Methodologically, the study establishes a holistic evaluation framework that integrates multi-stakeholder perspectives, ensuring inclusive consideration of diverse interests in destination image enhancement. Through a mixed-methods design combining text mining (government documents/tourist reviews) and grounded theory analysis (resident/business/non-profit interviews), it achieves triangulated validation of Wuyishan National Park’s destination image representations, significantly enhancing research rigor. This approach not only captures the multidimensionality of destination images but also bridges the epistemic gap between supply-side projections and demand-side perceptions—a critical advancement for protected area governance studies.

To elevate Wuyishan National Park’s destination image and ensure sustainable governance, we propose four evidence-based strategies informed by multi-stakeholder synergies: First, diversify destination offerings through balanced natural-cultural resource utilization. Develop immersive cultural products such as Zhuxi Neo-Confucianism study tours77 and tea ceremony experiences, while pioneering protective commercialization pathways 78 for intangible cultural heritage IP derivatives. This “ecology-as-foundation, nature-as-body, culture-as-soul” branding framework would recalibrate the park’s image beyond scenic dependency. Second, enhance tourism infrastructure via smart governance systems. Implement AI-driven ecological monitoring and tourist management tools through global national park data networks. Adopt dynamic pricing and crowd control alerts informed by real-time sentiment analytics79 to balance experiential quality with conservation imperatives. Third, deploy data-driven precision marketing. Utilize AI algorithms for personalized itinerary recommendations—prioritizing hiking routes for nature enthusiasts and intangible cultural heritage workshops for cultural travelers80. Amplify reach through cross-sector brand collaborations and social media virality campaigns. Fourth, institutionalize multi-stakeholder co-governance mechanisms: ①establish blockchain-tracked tourism revenue-sharing funds81, allocating income based on community contributions. ②launch time-phased tourist-resident access systems to mitigate congestion conflicts. ③create ecological compensation funds82 for tea enterprises and residents impacted by conservation policies. ④foster community-driven initiatives like artisan markets and skill-certified homestays to ensure equitable benefit distribution. ⑤invest in capacity-building programs to strengthen collaborative governance literacy.

The practical experience of Wuyishan National Park holds reference significance for other national parks as well. Research indicates that building a national park destination image requires taking multi-stakeholder collaborative governance as the core, achieving multi-dimensional value balance through differentiated resource transformation pathways and dynamic interest negotiation mechanisms. Specifically, in the process of shaping the destination image, it is essential to adhere to the principle of protection priority, base efforts on inherent resource endowments, dynamically adjust multi-stakeholder demands, revitalize and innovate cultural heritage, design community participation mechanisms, and ultimately realize sustainable development across ecological, economic, and social dimensions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Dudley, N. (Ed.). Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2008.PAPS.2.en (2008).

Eagles, P. F. J., Haynes, C. D. & McCool, S. F. Sustainable tourism in protected areas: Guidelines for planning and management. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN; Cambridge, United Kingdom: UNEP; Madrid, Spain: World Tourism Organization (2002).

Borrini-Feyerabend, G. et al. Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (2013).

Butler, R. & Boyd, S. (eds) Tourism and National Parks: Issues and Implications (Wiley, 2000).

Tasci, A. D. & Gartner, W. C. Destination image and its functional relationships. J. Travel Res. 45(4), 413–425 (2007).

Frost, W. & Hall, C. M. (eds) Tourism and National Parks: International Perspectives on Development, Histories and Change (Routledge, 2009).

Eagles, P. F. & McCool, S. F. Tourism in National Parks and Protected Areas: Planning and Management (CABI Publishing, 2002).

Crowson, J. M. Maloti Drakensberg Transfrontier Park Joint Management: Sehlabathebe National Park (Lesotho) and the uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park World Heritage Site (South Africa). In A. Watson, J. MurrietaSaldivar & B. McBride (Eds.), Science and Stewardship to Protect and Sustain Wilderness Values (pp. 53–56). USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Proceedings. Paper presented at the 9th World Wilderness Congress Symposium - Science and Stewardship to Protect and Sustain Wilderness Values, Merida, MEXICO (2011).

Görmüs, S. Conservation conflicts in nature conservation: The example of Kastamonu-Bartin Kure Mountains National Park. Eco. Mont.-J. Protect. Mount. Areas Res. 8(1), 39–43 (2016).

Pike, S. & Page, S. J. Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tour. Manage. 41, 202–227 (2014).

Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325(5939), 419–422 (2009).

Spence, M. D. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Watson, H. Sheepwrecked or a World Heritage Site? Thoughts on the Lake District. A New Nature Blog. Retrieved from https://anewnatureblog.com/2017/05/22/sheepwrecked-or-a-world-heritage-site-thoughts-on-the-lake-district/ (Accessed 22 May 2017).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543(7645), 373–377 (2017).

Yang, Y. & Zhu, Y. M. China formally established the first batch of national parks. Ecol. Econ. 37(12), 9–12 (2021).

Huang, B. R. et al. Pilot programs for national park system in China: Progress, problems and recommendations. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 33(1), 76–85 (2018).

General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China & General Office of the State Council. Overall plan for the establishment of a national park system (Zhong Ban Fa [2017] No. 55). Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2017-09/26/content_5227717.html (2017, September 26)

National Forestry and Grassland Administration (National Park Administration). Interim measures for the management of national parks (Lin Bao Fa [2022] No. 64). Retrieved from http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/586/20220603/091105144913143.html (2022, June 1).

General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China & General Office of the State Council. Guidelines on establishing a natural protected area system with national parks as the main body. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2019/content_5407657.htm (2019, June 26).

Aaker, D. A. & Myers, J. G. Advertising Management 2nd edn. (Prentice Hall, 1985).

Hunt, J. D. Image: A factor in tourism (Doctoral dissertation, Colorado State University, Colorado) (1971).

Crompton, J. L. An assessment of the image of Mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. J. Travel Res. 17(4), 18–23 (1979).

Baloglu, S. & McCleary, K. W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 26(4), 868–897 (1999).

Grosspietsch, M. Perceived and projected images of Rwanda: Tourist and international tour operator perspectives. Tour. Manage. 27(2), 225–234 (2006).

Ji, S. J. & Wall, G. Understanding supply- and demand-side destination image relationships: The case of Qingdao, China. J. Vacat. Market. 21(2), 205–222 (2015).

Stylidis, D., Shani, A. & Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manage. 58, 184–195 (2017).

Ashton, A. S. Tourist destination brand image development—An analysis based on stakeholders’ perception: A case study from Southland, New Zealand. J. Vacat. Mark. 20(3), 279–292 (2014).

Mak, A. H. N. Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Manage. 60, 280–297 (2017).

Freeman, R. E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Haukeland, J. V. Tourism stakeholders’ perceptions of national park management in Norway. J. Sustain. Tour. 19(2), 133–153 (2011).

Randle, E. J. & Hoye, R. Stakeholder perception of regulating commercial tourism in Victorian National Parks, Australia. Tour. Manag. 54, 138–149 (2016).

Choe, Y. & Schuett, M. A. Stakeholders’ perceptions of social and environmental changes affecting Everglades National Park in South Florida. Environ. Dev. 35, 100524 (2020).

Hausmann, A. et al. Understanding sentiment of national park tourists from social media data. People Nature 2(3), 750–760 (2020).

Allendorf, T. D., Smith, J. L. D. & Anderson, D. H. Residents’ perceptions of Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. Landsc. Urban Plann. 82(1–2), 33–40 (2007).

Yuan, S., Zhu, J., Ma, C. & Xie, Z. The evolutionary game of national park tourism development and governance: public supervision, government regulation and tourism enterprise. In Environment, Development and Sustainability. In press (2024).

Meng, J., Long, Y. & Shi, L. Stakeholders’ evolutionary relationship analysis of China’s national park ecotourism development. J. Environ. Manage. 316, 115188 (2022).

Xie, Z. J. & Onuma, A. A bioeconomic model of non-profit and for-profit national parks integrating locals in biodiversity conservation. Environ. Resource Econ. 86(3), 509–532 (2023).

Obua, J. & Harding, D. M. Tourist characteristics and attitudes towards Kibale National Park, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 17(7), 495–505 (1996).

Monz, C., D’Antonio, A., Lawson, S., Barber, J. & Newman, P. The ecological implications of tourist transportation in parks and protected areas: Examples from research in US National Parks. J. Transp. Geogr. 51, 27–35 (2016).

Reimann, M., Lamp, M.-L. & Palang, H. Tourism impacts and local communities in Estonian national parks. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 11(SI), 87–99 (2011).

Ibrahim, M. S. N. et al. Community well - being dimensions in Gunung Mulu National Park, Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10(1), 226 (2023).

Dong, Q., Zhang, B., Cai, X., Wang, X. & Morrison, A. M. Does the livelihood capital of rural households in national parks affect intentions to participate in conservation? A model based on an expanded theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 474, 143604 (2024).

Pérez-Calderón, E., Miguel-Barrado, V. & Sánchez-Cubo, F. Tourism business in Spanish national parks: A multidimensional perspective of sustainable tourism. Land 11(2), 190 (2022).

McNicol, B. & Rettie, K. Tourism operators’ perspectives of environmental supply of guided tours in national parks. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. Res. Plann. Manag. 21, 19–29 (2018).

Austin, R., Garrod, G. & Thompson, N. Assessing the performance of the national park authorities: A case study of Northumberland National Park, England. Public Money Manag. 36(5), 325–332 (2016).

Lockwood, M., Worboys, G. & Kothari, A. Managing protected areas: A global guide (1st ed.) London, UK/Sterling, VA, USA: Earthscan (2006).

Reed, M. S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Cons. 141(10), 2417–2431 (2008).

National Park Foundation. 2024 Park Partners Report: Innovating for the Future of Parks. Retrieved from https://www.nationalparks.org/uploads/2024_ParkPartnersReport.pdf (2024).

Stylidis, D., Belhassen, Y. & Shani, A. Three tales of a city: Stakeholders’ images of Eilat as a tourist destination. J. Travel Res. 54(6), 702–716 (2015).

Virgo, B. & de Chernatony, L. Delphic brand visioning to align stakeholder buy-in to the City of Birmingham brand. J. Brand Manag. 13(6), 379–392 (2006).

Chen, Y. On the logic of check and balance in China’s environmental multi-governance. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 30(6), 116–125 (2020).

Yu, J. A., Liu, S. T., Shi, X. R. & Qi, Y. Y. The theoretical logic, business model and experience enlightenment of enterprise participation in desertification control under the multi-governance model. J. Desert Res. 44(4), 244–252 (2024).

Choi, S., Lehto, X. Y. & Morrison, A. M. Destination image representation on the web: Content analysis of Macau travel-related websites. Tour. Manage. 28(1), 118–129 (2007).

Stepchenkova, S. & Zhan, F. Z. Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tour. Manage. 36, 590–601 (2013).

Zhang, H. M., Long, Y. S., Liang, C. Y., Chen, X. & Zhang, C. Study on the influencing factors of brand image of wine tourism destination based on grounded theory: An example of Helan Mountain’s East Foothill. China Soft Sci. 10, 184–192 (2019).

Russell, J. A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39(6), 1161–1178 (1980).

Lakoff, G. Image metaphors. Metaphor Symb. Act. 2(3), 219–222 (1987).

Cao, M. Q. et al. TDlVis: Visual analysis of tourism destination images. Front. Inform. Technol. Electron. Eng. 21(4), 536–557 (2020).

Arefieva, V., Egger, R. & Yu, J. A machine learning approach to cluster destination image on Instagram. Tour. Manage. 85, 104318 (2021).

Marine-Roig, E. Destination image analytics through traveller-generated content. Sustainability 11(12), 212–223 (2019).

Cini, F. & Saayman, M. Understanding tourists’ image of the oldest marine park in Africa. Curr. Issue Tour. 16(7–8), 664–681 (2013).

Bai, L., Shao, W. & Jiang, Y. Perceptions and attitudes of community residents to national park. J. Nanjing For. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 47(2), 205–212 (2023).

Choy, D. L.-Y. A gap analysis of employee satisfaction for the National Park Service: Picturesque Park. University of Southern California (2015).

Bettinger, K. A. Political contestation, resource control and conservation in an era of decentralisation at Indonesia’s Kerinci Seblat National Park. Asia Pac. Viewp. 56(2), 252–266 (2015).

Rodríguez-Rangel, C. & Sánchez-Rivero, M. Qualitative analysis of the online tourist image of Zafra (Spain) through the comments in Tripadvisor. Investig. Turíst. 21, 128–151 (2021).

Choi, B. C. K. & Pak, A. W. P. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2(1), A13 (2004).

Creswell, J. W. & Poth, C. N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches 4th edn. (SAGE Publications, 2017).

Xiao, L. & Zhao, L. M. The Tourism destination image of Taiwan disseminated on internet—Based on a content analysis of travel-related websites across Taiwan Straits. Tourism Tribune 24(3), 75–81 (2009).

Wang, Y. M., Wang, M. X., Li, R. & Wu, D. Y. Destination image perception of Fenghuang Ancient Town based on content analysis of travelers’ web text. Geography Geo-Inform Sci 31(1), 64–67, 79 (2015).

Beerli, A. & Martin, J. D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 31(3), 657–681 (2004).

Han, Y. N., Liu, J. W. & Luo, X. L. A survey on probabilistic topic model. Chin. J. Comput 06, 1095–1139 (2021).

Huang, W. D., Zhu, S. T. & Yao, X. K. Destination image recognition and emotion analysis: Evidence from user-generated content of online travel communities. Comput. J. 64(3), 296–304 (2021).

Dunne, C. The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 14(2), 111–124 (2011).

Madhusudan, M. D. & Mishra, C. Why big, fierce animals are threatened: conserving large mammals in densely populated landscapes. In Battles over Nature: Science and the Politics of Conservation (eds Saberwal, V. K. & Rangarajan, M.) 31–55 (Permanent Black, 2003).

Hasenfeld, Y. & Garrow, E. E. Nonprofit human-service organizations, social rights, and advocacy in a neoliberal welfare state. Soc. Service Rev. 86(2), 295–322 (2012).

Wang, M., Cai, Z. H. & Wang, C. T. Social co-governance: The exploring praxis and institutional innovation of multi-subject governance. Chin. Public Admin. 12, 16–19 (2014).

Li, X. An analysis on new value of the times in Zhu Zi culture. Fujian Tribune 12, 35–41 (2018).

Bortolotto, C. & Skounti, A. (eds) Intangible Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Development: Inside a UNESCO Convention (Routledge, Milton Park, 2024).

Jiang, W. et al. Using geotagged social media data to explore sentiment changes in tourist flow: A spatiotemporal analytical framework. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 10(3), 135 (2021).

Liu, D., Wang, L., Zhong, Y., Dong, Y. & Kong, J. Personalized tour itinerary recommendation algorithm based on tourist comprehensive satisfaction. Appl. Sci. 14(12), 5195 (2024).

Munanura, I. E., Backman, K. F., Hallo, J. C. & Powell, R. B. Perceptions of tourism revenue sharing impacts on Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda: A Sustainable Livelihoods framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 24(12), 1709–1726 (2016).

Qu, Q., Tsai, S., Tang, M., Xu, C. & Dong, W. Marine ecological environment management based on ecological compensation mechanisms. Sustainability 8(12), 1267 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingpei Qiu contributed to the Manuscript by undertaking the Primary writing and data collection efforts. Zixuan Xie participated in the revision of the manuscript. Conglin Zhang offered his expertise in providing guidance throughout the research process, and also contributed to the review of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data for this study were obtained from publicly available data on the internet and from an anonymous survey study, which did not require ethical clearance. However, we ensured that participants’ rights and well-being were always taken care of in accordance with the ethical principles of research with human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jingpei, Q., ZiXuan, X. & Conglin, Z. Destination image of China’s National parks from a stakeholder perspective. Sci Rep 15, 27225 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09920-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09920-0