Abstract

High-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) is a highly aggressive gynecologic malignancy, and chemoresistance remains a major challenge in its treatment. This study identifies ZDHHC8 as a key regulator of chemotherapy sensitivity in HGSOC. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that elevated ZDHHC8 expression correlates with poorer progression-free and overall survival in chemotherapy-treated patients. Immunohistochemical analysis of clinical HGSOC samples further demonstrated that chemoresistant tumors exhibit higher levels of ZDHHC8 than chemotherapy-sensitive ones. In vitro functional assays showed that ZDHHC8 knockdown enhanced chemotherapy sensitivity by decreasing the cisplatin IC50, increasing cisplatin-induced apoptosis, and promoting DNA damage, whereas overexpression experiments reduced cisplatin sensitivity. Mechanistic studies indicated that KLF5, identified as a transcription factor through chromatin immunoprecipitation and luciferase reporter assays, directly binds to the ZDHHC8 promoter and upregulates its expression. Moreover, ZDHHC8 upregulates β-catenin, a key mediator of chemotherapy insensitivity, and its effects are reversed by a β-catenin inhibitor. Animal models further supported the roles of ZDHHC8, KLF5, and β-catenin in regulating chemotherapy sensitivity. Collectively, these results establish the KLF5-ZDHHC8-β-catenin axis as a critical pathway that impairs chemotherapy sensitivity in HGSOC and suggest that targeting ZDHHC8 may improve treatment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal cancer of the female reproductive system and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death among women1,2,3,4. High-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) is the predominant subtype, accounting for 70–80% of ovarian cancer mortality5,6. Despite advancements in surgery and chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rate for HGSOC remains below 30%7. This high mortality rate is largely due to late-stage diagnoses and impaired chemotherapy sensitivity8,9. Although HGSOC is initially responsive to treatment, it frequently relapses with acquired chemotherapy resistance10,11,12. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying reduced chemotherapy sensitivity is critical for improving therapeutic strategies and patient outcomes.

Protein palmitoylation, a reversible post-translational modification, regulates protein stability, trafficking, and cellular signaling13,14. Dysregulated palmitoylation has been implicated in tumorigenesis by affecting cell growth, survival, and response to therapy across various cancers15,16,17,18. This modification is catalyzed by a family of 23 palmitoyltransferases characterized by conserved zinc finger Asp-His-His-Cys (ZDHHC) motifs19. Emerging evidence suggests that the ZDHHC family plays critical roles in tumorigenesis and drug sensitivity20,21,22,23. Specifically, ZDHHC8 has been linked to the progression of glioblastoma and mesothelioma24,25. However, its function in HGSOC, particularly regarding chemotherapy sensitivity, remains unexplored.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is a well-established driver in multiple cancers, including ovarian cancer26. Aberrant activation of β-catenin not only promotes carcinogenesis, metastasis, and recurrence but also reduces chemotherapy efficacy27,28. Emerging evidence indicates that post-translational palmitoylation by DHHC family palmitoyltransferases regulates β-catenin stability and Wnt signaling activity. For instance, palmitoylation of β-catenin enhances its stability and promotes hyperactivation of Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer29while DHHC enzymes have also been reported to modify other key Wnt components such as LRP630. Based on these findings, this study aims to explore whether ZDHHC8 modulates chemotherapy sensitivity in HGSOC via the β-catenin signaling pathway.

In addition, the transcription factor KLF5 has been identified as an upstream regulator of key oncogenic and drug-resistance genes. It promotes CCND1 expression and proliferation in pancreatic and prostate cancers31,32and cooperates with the androgen receptor to activate MYC in prostate cancer32. In lung cancer, KLF5 knockdown increases ABCG2 expression, conferring doxorubicin resistance33. In breast cancer, KLF5 binds a mutant mTOR promoter to repress its expression and modulate paclitaxel sensitivity34. KLF5 has also been shown to drive carcinogenesis through β-catenin signaling in colon and breast cancers35,36,37. In ovarian cancer, KLF5 is associated with tumor progression and resistance to PARP inhibitors38yet its potential role in regulating ZDHHC8 expression has not been examined.

The present study aims to investigate the role of ZDHHC8 in mediating platin-based chemotherapy response in HGSOC and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms. By characterizing the KLF5-ZDHHC8-β-catenin axis, this work provides potential therapeutic targets for improving chemotherapy sensitivity in HGSOC.

Results

Palmitoylation activation in HGSOC and elevated ZDHHC8 predicts poor survival

To investigate the role of palmitoylation in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), we analyzed palmitoylation pathways and related genes using TCGA data. The single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) revealed significant activation of palmitoylation-related pathways in ovarian cancer compared to normal tissues (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Among 23 palmitoyltransferase genes, 20 were differentially expressed, with 10 upregulated and 10 downregulated in cancer tissues (Fig. 1b). Univariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that elevated ZDHHC8 and ZDHHC18 expression correlated with poorer OS (Fig. 1c), suggesting their potential as prognostic factors. This finding was validated using an integrated GEO dataset39 (Fig. 1D). However, only ZDHHC8 maintained a significant association with progression-free survival (PFS) (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Given that chemotherapy is the first-line treatment for HGSOC, we further assessed the prognostic impact of ZDHHC8 and ZDHHC18 in platin-treated patients from the integrated GEO dataset. ZDHHC8 exhibited a stronger correlation with poorer OS (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.53) than ZDHHC18 (HR = 1.22), and only ZDHHC8 was significantly associated with worse PFS (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1c).

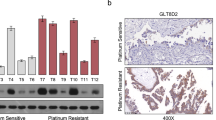

To validate these findings, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed on tumor samples from clinical patients. Consistent with the survival analysis, ZDHHC8 expression was higher in chemotherapy-resistant patients than in chemotherapy-sensitive patients (Fig. 1f). These results highlight ZDHHC8 as a robust prognostic marker in ovarian cancer, particularly in the context of chemotherapy.

ZDHHC8 impairs cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer

To evaluate the role of ZDHHC8 in platinum-based therapy response in HGSOC, we conducted a series of in vitro experiments using HGSOC cell lines. Quantification of ZDHHC8 expression revealed significantly higher levels in cancer cell lines compared to normal ovarian epithelial cells, consistent with TCGA data. Among the cancer cell lines, SKOV3 and CAOV3 (high ZDHHC8 level) were selected for knockdown experiments, while OVCAR3 cell (moderate ZDHHC8 expression) was used for overexpression studies (Supplementary Fig. 2a-b).

To investigate the impact of ZDHHC8 on cisplatin sensitivity, shRNA-mediated ZDHHC8 knockdown (shZDHHC8) was performed in SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells, with silencing efficiency confirmed via qPCR and WB (Fig. 2a). Cells were treated with a cisplatin gradient (0–100 µM), and IC50 values were determined using the CCK-8 assay. The dose-response curves showed that ZDHHC8 knockdown significantly reduced IC50 values compared to control cells (shRNA negative control, shNC), indicating enhanced sensitivity to cisplatin (Fig. 2b). Using a second shRNA (shZDHHC8-2) yielded the same reduction in IC50, confirming phenotype consistency (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Conversely, overexpression of ZDHHC8 (oeZDHHC8) in OVCAR3 cells increased IC50 values, reflecting compromised cisplatin sensitivity (Fig. 2c-d). These results suggest that ZDHHC8 plays a key role in reducing cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer cells.

ZDHHC8 attenuates cisplatin-induced apoptosis and DNA damage

To further elucidate the role of ZDHHC8 in cisplatin-treated cells, we assessed apoptosis and DNA damage following ZDHHC8 knockdown or overexpression. Flow cytometry analysis revealed a significant increase in apoptosis in both shZDHHC8 cells and cisplatin (CDDP)-treated cells (P < 0.001). Notably, apoptosis was further amplified in shZDHHC8 cells combined with CDDP treatment (Fig. 2e). Consistently, γ-H2AX staining showed enhanced DNA damage in shZDHHC8 SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells, further supporting the observed additive effect (Fig. 2f). The same phenotype was observed using a second shRNA (shZDHHC8-2) (Supplementary Fig. 3b-c). In contrast, ZDHHC8 overexpression attenuated the pro-apoptotic effects of cisplatin. While CDDP treatment increased apoptosis to ~ 26% in wild-type (wt) cells, it reduced to ~ 17% in oeZDHHC8 cells (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2g). Similarly, γ-H2AX staining confirmed that ZDHHC8 overexpression suppressed cisplatin-induced DNA damage (Fig. 2h).

Together with the IC50 results, these findings demonstrate that ZDHHC8 reduces cisplatin sensitivity as assessed by apoptosis and DNA damage in ovarian cancer cells.

ZDHHC8 reduces cisplatin sensitivity in vivo

Building on our in vitro findings, we investigated whether the effect of ZDHHC8 on cisplatin resistance could be translated to in vivo models. Xenograft mouse models were established using shZDHHC8-CAOV3 and oeZDHHC8-OVCAR3 cells. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with vehicle or CDDP, and tumor growth was monitored.

Cisplatin treatment significantly suppressed tumor growth compared to vehicle control, with the greatest tumor suppression observed in the CDDP-treated shZDHHC8 group (P < 0.001), indicating an additive effect of ZDHHC8 knockdown and cisplatin (Fig. 3a-c). Histological analysis revealed extensive necrosis and increased apoptosis in the CDDP-treated shZDHHC8 group, as confirmed by TUNEL staining, demonstrating that ZDHHC8 knockdown enhances CDDP-induced tumor suppression (Fig. 3d). Conversely, ZDHHC8 overexpression attenuated the tumor-suppressive effects of cisplatin. Mice in the CDDP-treated oeZDHHC8 group exhibited larger (P = 0.007) and heavier (P = 0.003) tumors compared to the CDDP-treated wild-type group (Fig. 3e-g). Histological analysis showed reduced necrosis and fewer apoptotic cells in tumors from the oeZDHHC8 group, further confirming the attenuating effect of ZDHHC8 overexpression on cisplatin-induced tumor suppression (Fig. 3h).

These results establish that ZDHHC8 impairs cisplatin-induced tumor suppression in vivo, reinforcing its role in diminishing chemotherapy sensitivity in ovarian cancer.

KLF5 upregulates ZDHHC8 expression to reduce cisplatin sensitivity

To identify upstream regulators of ZDHHC8, we utilized the JASPAR database (https://jaspar.elixir.no/) to predict potential transcription factors and binding sites within its promoter region. KLF5 emerged as a candidate, and its consensus binding sequence (GCCCCGCCCC) was found in the promoter of ZDHHC8 (Fig. 4a). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays confirmed significant enrichment of KLF5 at the ZDHHC8 promoter (P < 0.001), demonstrating direct binding (Fig. 4b). A luciferase reporter assay further showed that KLF5 overexpression enhanced ZDHHC8 promoter activity in wild-type constructs but not in mutants (non-binding sequence: TGGAGTGGAG) lacking the KLF5 binding site (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4c). Moreover, analysis of TCGA RNAseq data revealed that KLF5 is significantly upregulated in HGSOC tumors compared with normal controls (P < 0.0001) and positively correlates with ZDHHC8 expression (R = 0.37, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 4a-b).

To validate the clinical relevance of this finding, we conducted IHC analysis of HGSOC tumor samples. KLF5 expression was significantly higher in chemotherapy-resistant tumors compared to chemotherapy-sensitive patients (Fig. 4d). This clinical observation underscores the role of KLF5 in modulating cisplatin sensitivity.

Consistent with these findings, KLF5 knockdown (shKLF5) significantly reduced ZDHHC8 expression (P < 0.001), whereas KLF5 overexpression (oeKLF5) markedly increased it (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4e). Functionally, KLF5 knockdown enhanced CDDP-induced apoptosis and DNA damage in CAOV3 and SKOV3 cells (Fig. 4f-g), supporting its role in reducing chemo-sensitivity.

To assess whether the pro-apoptotic effects of KLF5 knockdown are specifically mediated through ZDHHC8, we performed individual and combined knockdown experiments targeting KLF5 and ZDHHC8 in CAOV3 cells treated with cisplatin (Fig. 5a-b). Silencing either KLF5 or ZDHHC8 significantly increased cell apoptosis, while their combined knockdown had no additive effect, suggesting that they function within the same axis. Notably, overexpression of ZDHHC8 in KLF5-knockdown cells markedly rescued the apoptotic phenotype (Fig. 5c-d), indicating that ZDHHC8 acts downstream of KLF5 in modulating chemo-sensitivity (Fig. 5c-d).

In conclusion, these findings confirm that KLF5 directly binds to the ZDHHC8 promoter, enhancing its expression and reducing chemotherapy sensitivity.

KLF5 knockdown enhances cisplatin sensitivity in vivo

To validate the role of KLF5 in vivo, xenograft models were established using KLF5 knockdown CAOV3 cells (shKLF5) and control CAOV3 cells (shNC). Tumor-bearing mice were treated with either vehicle or CDDP. KLF5 knockdown modestly reduced tumor growth compared to the control (vehicle-treated shNC group, P < 0.001). CDDP treatment significantly suppressed tumor growth in both shNC and shKLF5 models, with the greatest tumor suppression observed in the CDDP-treated shKLF5 group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5a-c). The histological analysis further confirmed enhanced cisplatin sensitivity in the shKLF5 group. Tumors from the CDDP-treated shKLF5 group exhibited extensive necrosis and elevated TUNEL-positive apoptosis compared to other groups (Fig. 5d).

These results demonstrate that KLF5 knockdown enhances cisplatin sensitivity in vivo and highlight its pivotal role as a transcription factor that regulates ZDHHC8 expression to modulate chemotherapy responsiveness.

β-catenin acts as a downstream effector of ZDHHC8

As a key mediator of the Wnt signaling pathway, β-catenin has been demonstrated to promote chemoresistance in ovarian cancer40. Upon activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm, translocates to the nucleus, and interacts with transcription factors TCF/LEF to activate downstream effectors, which contributes to apoptosis evasion and chemoresistance. In our analysis, ssGSEA revealed a positive correlation between ZDHHC8 expression and WNT/β-catenin pathway activity in HGSOC samples (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, RNAseq data showed that β-catenin expression is downregulated in HGSOC tumors compared to normal tissues, and correlates positively with ZDHHC8 levels in HGSOC tumors (R = 0.59, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 4c-d). Although both β-catenin and ZDHHC8 are downregulated in tumors, their relative expression levels within tumors retain prognostic value. Using the CSS-Palm tool (http://csspalm.biocuckoo.org/)41, we identified a high-confidence palmitoylation site at cysteine 300 of β-catenin. These findings, combined with prior evidence linking palmitoylation to protein stabilization, suggest that ZDHHC8 may enhance β-catenin stability, thereby reducing chemotherapy sensitivity.

To validate the role of β-catenin in ZDHHC8-mediated cisplatin resistance, we examined its expression in ovarian cancer cells following ZDHHC8 knockdown or overexpression. ZDHHC8 knockdown significantly reduced β-catenin protein levels, with an additive effect observed in combination with cisplatin. Conversely, ZDHHC8 overexpression markedly increased β-catenin protein levels (Fig. 6b). Notably, β-catenin RNA levels remained unchanged, consistent with ZDHHC8’s role as a post-translational modification enzyme. Since KLF5 is a transcription factor known to regulate ZDHHC8 expression, we further investigated its impact on β-catenin levels. In cell lines with KLF5 knockdown, β-catenin protein levels were significantly decreased, and this reduction was further enhanced when combined with CDDP treatment (Fig. 6c).

To further confirm the involvement of β-catenin in ZDHHC8-driven cisplatin insensitivity, oeZDHHC8 OVCAR3 cells were treated with the β-catenin inhibitor XAV939 in combination with CDDP, and the inhibition efficiency of XAV939 was confirmed via WB analysis (Fig. 6d). Consistent with previous results, ZDHHC8 overexpression reduced cisplatin sensitivity, as reflected by a higher IC50 value (18.03 µM in oeZDHHC8 cells vs. 11.19 µM in controls). However, XAV939 treatment effectively reversed this effect, reducing the IC50 to 9.12 µM (Fig. 6e). Additionally, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that XAV939 significantly promoted apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells, effectively counteracting the anti-apoptotic effect induced by ZDHHC8 overexpression (Fig. 6f). Consistently, γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showed increased cellular DNA damage upon XAV939 treatment, further highlighting the essential role of β-catenin in regulating chemo-sensitivity (Fig. 6g).

Together, these findings identify β-catenin as a critical downstream effector of ZDHHC8 in reducing cisplatin sensitivity and underscore the role of the KLF5-ZDHHC8-β-catenin axis in regulating chemotherapy sensitivity.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that palmitoylation-related pathways are significantly upregulated in HGSOC, with ZDHHC8 emerging as a key factor. Specifically, elevated ZDHHC8 expression correlates significantly with poorer OS and PFS, especially among patients receiving chemotherapy. Our functional analyses provide strong evidence that ZDHHC8 overexpression diminishes cisplatin-induced apoptosis and reduces DNA damage, while silencing ZDHHC8 notably enhances cisplatin sensitivity both in vitro and in vivo. These observations underscore ZDHHC8 as a potential predictive marker for chemotherapy responsiveness and a promising therapeutic target in HGSOC management.

Mechanistically, our study makes a novel contribution by identifying KLF5 as a direct transcriptional regulator of ZDHHC8. We demonstrate that KLF5 directly binds to the promoter region of ZDHHC8, upregulating its expression and thereby reducing chemotherapy sensitivity. Furthermore, our findings reveal that ZDHHC8 promotes β-catenin level, positioning β-catenin as a critical downstream mediator through which ZDHHC8 exerts its pro-survival effects. Importantly, this effect can be reversed by β-catenin inhibition, supporting the therapeutic potential of targeting the KLF5-ZDHHC8-β-catenin axis in clinical interventions.

Despite these advances, several limitations warrant further investigation. Although β-catenin has been identified as a downstream effector of ZDHHC8, the precise post-translational mechanisms remain elusive. β-Catenin has been extensively studied for its post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and ubiquitination, which lead to its inactivation or degradation. Notably, our data indicate that ZDHHC8 influences β-catenin protein stability without affecting its mRNA levels, suggesting a role in modulating post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Future studies should focus on elucidating whether ZDHHC8-mediated palmitoylation prevents β-catenin degradation by interfering with these modifications.

Although the dependency between KLF5 and ZDHHC8 has been interrogated through double knockdown and rescue experiments, triple knockdown or inhibition assays involving KLF5, ZDHHC8, and β-catenin have not yet been performed. Consequently, indirect effects cannot be fully excluded, representing a limitation of the present study. Future work will include such comprehensive combinatorial perturbations to fully establish pathway order and dependency.

Additionally, while the KLF5-ZDHHC8-β-catenin axis appears to be a critical determinant of cisplatin sensitivity, its comprehensive impact on chemotherapy responsiveness remains to be fully defined. β-catenin activation is known to drive epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cell-like traits, which are intimately linked to chemoresistance40. Although migration and invasion assays are key to assessing these phenotypes, we have not yet performed such experiments. This study based on apoptosis and DNA damage endpoints, and assessment of ZDHHC8’s effects on migration, invasion, and EMT marker expression will be considered in future studies. Beyond EMT, factors such as increased drug efflux, impaired apoptosis, enhanced DNA repair capacity, and dysregulated signaling pathways (e.g., EGFR, PI3K/AKT, PTEN, and mTOR) may also contribute42,43. Advanced techniques such as proteomics, and ChIP-seq assays could further uncover additional molecular targets of ZDHHC8 within its regulatory network.

Finally, although this study primarily addresses cisplatin sensitivity, the potential role of ZDHHC8 in mediating responses to other chemotherapeutic agents, particularly paclitaxel, warrants further investigation. Given that combination regimens such as cisplatin/paclitaxel or carboplatin/paclitaxel are standard therapies in ovarian cancer, it is important to determine whether ZDHHC8 functions as a general regulator of chemosensitivity or displays agent-specific effects. Moreover, our IHC analysis was performed on a modest cohort (10 resistant and 14 sensitive cases). Expanding the sample size and incorporating β-catenin immunostaining will be important to validate the clinical significance of our findings and enhance translational applicability.

In summary, our study demonstrates that ZDHHC8 plays a pivotal role in regulating chemotherapy sensitivity in HGSOC by modulating the KLF5–ZDHHC8–β-catenin axis. These findings not only elucidate novel molecular mechanisms underlying chemoresistance but also suggest that targeting this axis may enhance chemotherapy efficacy and improve patient outcomes. Further mechanistic and translational investigations are crucial to fully unlocking its clinical potential.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

HGSOC tissues were collected from 24 patients treated at Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China) between 2019 and 2022. All patients were histopathologically diagnosed with HGSOC and underwent optimal cytoreductive surgery (R0 resection) followed by standard chemotherapy. Among them, 10 patients were classified as chemotherapy-resistant, defined as relapses within 6 months after treatment, and 14 as chemotherapy-sensitive, with relapses occurring at 6 months or later44,45,46. Ethical approval was obtained from the Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Cell culture procedures

HGSOC cell lines (SK-OV-3 [RRID: CVCL_0532], Caov-3 [RRID: CVCL_0201], A2780 [RRID: CVCL_0134], and OVCAR-3 [RRID: CVCL_0465]) and the normal human ovary epithelial cell line IOSE-29 [RRID: CVCL_5535] were obtained from the Public Cell Bank of the Yilaibo Bio Inc. (Shanghai, China), and their authenticity was verified by STR profiling. SKOV3 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5 A medium, CAOV3 in DMEM, and A2780, OVCAR3, and IOSE29 in RPMI-1640, all supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, at 37 °C with 5% CO₂. Cells were subcultured at approximately 80% confluence using a 0.25% trypsin solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

Bioinformatics analysis

Palmitoylation-related genesets were retrieved from the Molecular Signatures Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb)47 using the keywords “palmitoy”, “palmitoyltransferase”, and “palmitoylation”. MSigDB (v2024.1.Hs) is a comprehensive resource that integrates gene sets and pathway information from multiple sources such as Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG. Five palmitoylation-relevant gene sets, all derived from GO terms, were identified and downloaded. Wnt/β-catenin pathway genesets were obtained from the KEGG pathway and curated from the “Pathways on cancer” (KEGG ID: hsa05200)48,49,50. The specific gene members for each set are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Sample level enrichment scores were calculated using the single sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) method implemented in the R package “GSVA” (v2.0.2) (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GSVA.html)51. This method ranks all genes in each sample by their expression levels. It then calculates an enrichment score by comparing the distribution of set members to that of all other genes. The resulting ssGSEA score reflects the activity of each pathway in each sample. Palmitoylation enrichment scores were computed for all tumor and normal samples. Differences in enrichment between cancer and normal tissues were assessed by independent Student’s t tests with P < 0.05 considered significant.

A normalized gene expression dataset (dataset ID: TcgaTargetGtex_rsem_gene_tpm, version: 2016-09-03) was obtained from the UCSC Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/)52. This dataset integrates RSEM-normalized TPM values from TCGA, GTEx, and TARGET project, with expression levels reported as log2(TPM + 0.001). Due to the absence of normal ovarian tissue samples in TCGA and the fallopian tube origin of ovarian cancer, GTEx fallopian tube samples were used as normal controls alongside 427 HGSOC tumor samples from TCGA. Of these tumor samples, 373 had survival information and were included in prognostic analyses. Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression were performed on differentially expressed ZDHHC family genes using the R package “survival” (v3.4) (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html), specifying R codes as “coxph(Surv(OS_time, OS_event) ~ gene_expression, data = …)”. Results were visualized with the forestplot package (v3.1.3) (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/forestplot/index.html). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated with “survfit” and plotted using R package “survminer” (v0.4.9) (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survminer/index.html), and statistical significance between high‐ and low‐expression groups was assessed by log‐rank test.

The integrated GEO dataset used for validation comprises transcriptome-level gene expression and clinical follow‐up data from 1,657 ovarian cancer patients, as collected and normalized by Carsten Denkert et al.53. All samples were processed using a uniform normalization pipeline and deposited into the online KMplot database (Release 2024.02.20) (http://kmplot.com/analysis/)54. For survival analyses, the “Auto select best cutoff” option was applied to split patients by gene expression, and all other settings were retained as defaults. Overall survival (OS) data were available for 655 patients, and progression-free survival (PFS) data for 614 patients. Subgroup analyses were conducted on platin-treated cohorts by selecting “Chemotherapy-contains platin” under the treatment-restriction parameter, yielding 478 patients for OS and 502 for PFS. Hazard ratios and log-rank p-values were then calculated and reported for each gene of interest.

Potential transcription factors of ZDHHC8 were predicted using the JASPAR database (v2024) (https://jaspar.elixir.no/)55, a curated collection of transcription factor binding profiles derived from experimental data. The ZDHHC8 promoter sequence (-2000 to + 200 bp relative to the transcription start site) was scanned on the JASPAR web server with a threshold score ≥ 0.8 to ensure prediction accuracy.

The protein palmitoylation site was predicted by the CSS-Palm tool (v4.0) (http://csspalm.biocuckoo.org/)51, which employs an algorithm trained on experimentally validated palmitoylation data. The β-catenin amino acid sequence was submitted in FASTA format to the CSS-Palm online interface, and sites classified as “high confidence” were considered as potential modification sites.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue Sect. (4 μm thick) were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in a citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95 °C for 20 min. The sections were cooled to room temperature and rinsed with PBS. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides with 3% H2O2 for 10 min.

The sections were then incubated with a blocking solution (5% bovine serum albumin, BSA) for 20 min at room temperature to prevent nonspecific binding. Primary antibodies specific to ZDHHC8 (1:100, Bioss Antibodies, China, Cat# bs-18486R) and KLF5 (1:3000, Thermo Fisher, USA, Cat# PA5-27876) were applied and incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber. After washing with PBS, the slides were incubated with a secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature.

Immunoreactivity was visualized using DAB as the chromogen, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin. The slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted with coverslips. Images were captured using a light microscope, and staining intensity was evaluated semi-quantitatively by pathologists blinded to sample information.

Stable cell line construction

For knockdown experiments, shRNA sequences targeting ZDHHC8 and KLF5 were cloned into the pLKO.1-puro vector, with shNC serving as the negative control. The specific sequences are listed in Table 1. Lentiviral particles were generated in HEK293T cells and used to infect SKOV3 and CAOV3 cells. Infected cells were selected with puromycin (2 µg/mL) for 7–10 days. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) and Western blot (WB).

For overexpression experiments, ZDHHC8 and KLF5 coding sequences were retrieved from NCBI and synthesized by GeneralBiol Inc (Anhui, China). The genes were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector, and OVCAR3 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher, USA, Cat# 11668030). Stable cell lines were selected with 600 µg/mL G418 for 10–14 days. Overexpression was validated by qRT-PCR and WB.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues and cell lines using TRIzol reagent (Solarbio, Beijing, China, Cat# 15596026). RNA concentration and quality were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, USA), ensuring an A260/A280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 before further processing. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher, USA, Cat# 4309155) on a real-time PCR detection system (HongshiTech, Shanghai, China). Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2 − ΔΔCt method, with the target gene expression normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin, which served as an internal control. The primers used are listed in Table 2.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from cells or tissues using RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher, USA, Cat# 89900). Equal amounts of protein (10 µg per sample) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 12% gel and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Germany). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBST (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat# P0231) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies against ZDHHC8 (1:1000, Cat# 27179-1-AP), KLF5 (1:1000, Cat# 21017-1-AP), β-catenin (1:5000, Cat# 51067-2-AP), β-actin (1:5000, Cat# 81115-1-RR), and H3 (1:2000, Cat# 17168-1-AP) (Proteintech, USA). After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000, ZSGB-Bio, Beijing, China, Cat# ZB-2301) for 2 h at room temperature. Protein bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence and quantified with ImageJ software (v1.53t, https://imagej.net/ij/download.html)56. Protein expression was normalized to β-actin for cytoplasmic proteins and H3 for nuclear proteins.

CCK-8 assay

To evaluate cisplatin sensitivity, cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 10³ cells per well in 100 µL of complete medium. After overnight adherence, cells were treated with a gradient of cisplatin (CDDP, MCE, China, Cat# HY-17394) concentrations (0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µM), or with a co-treatment with β-catenin inhibitor XAV939 (MCE, Shanghai, China, Cat# HY-15147). After 48 h of incubation, 10 µL of the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) reagent (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat# C0039) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (PERLONG, Beijing, China). Dose-response curves were generated for each cell line using GraphPad Prism 9, and IC50 values were calculated via nonlinear regression analysis. Paired t-tests were performed to compare IC50 values between knockdown or overexpression with control groups.

Flow cytometry

Apoptosis was evaluated using the Annexin V-PE Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat# C1062). Cell lines were treated with 10 µM CDDP, 10 µM XAV939, or vehicle control for 48 h. After treatment, both adherent and floating cells were harvested, washed twice with cold PBS, and resuspended in 1× binding buffer at a concentration of 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL. A 100 µL cell suspension was transferred into flow cytometry tubes, and reagents from the apoptosis detection kit were added. The samples were gently mixed, incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 min, and then diluted with 400 µL of 1× binding buffer. Apoptosis was analyzed immediately using a CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman, USA), collecting at least 10,000 events per sample. Data were processed using FlowJo software (v10.6.2, https://www.flowjo.com/flowjo10/download).

γ-H2AX immunofluorescence

To detect DNA damage, cells were seeded on sterile glass coverslips in 24-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) and allowed to adhere overnight. After treatment with 10 µM CDDP, 10 µM XAV939, or vehicle for 48 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. The DNA Damage Assay Kit by γ-H2AX Immunofluorescence (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat# C2035S) was used for staining. Blocking was performed for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with the primary γ-H2AX antibody at 4°C overnight. The next day, a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody was applied for 1 h in the dark, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI for 5 min. Fluorescence images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan) using DAPI (blue) and FITC (green) filters. γ-H2AX foci (green) were quantified using ImageJ (v1.53t, https://imagej.net/ij/download.html) and normalized to DAPI-stained nuclei count (blue).

Tumor xenograft model

Six-week-old male BALB/c nude mice (SPF grade) were purchased from Hangzhou Ziyuan Experimental Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (China) and housed under pathogen-free conditions with controlled temperature, humidity, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animal experiments were performed following the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Rat&Mouse Biotech Co.,Ltd. Each mouse was subcutaneously injected with 2.5 × 106 cells in 200 µL serum-free medium into the right flank. Once tumors reached approximately 100 mm3the mice were randomly assigned to groups. Cisplatin (CDDP, 5 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally once a week for three weeks, while vehicle groups received an equal volume of the control solution. Tumor sizes were measured every three days using calipers, and volumes were calculated. At the end of the experiment, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were excised, weighed, and analyzed.

H&E staining

Tumor tissues were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4 μm. For histopathological evaluation, sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and stained with hematoxylin for 5 min, followed by eosin for 2 min. After dehydration, the slides were mounted and examined under a light microscope to evaluate morphological changes in tumor tissue.

TUNEL assay

To detect apoptosis in mouse tumor tissues, samples were processed using the TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat# C1088). Sections were treated with proteinase K, incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture for 1 h at 37 °C, and counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, Cat# C1002) to visualize nuclei. Following this, the slides were mounted and analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan). Apoptotic cells were identified by green fluorescence (TUNEL-positive). Representative images were captured for further analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

The ChIP assay was performed on OVCAR3 cells to assess KLF5 binding to the ZDHHC8 promoter. Cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature and the reaction was stopped with glycine. After cell collection, chromatin was extracted using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, and fragmented to 200–500 bp DNA fragments by sonication. Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-KLF5 antibody (1:50, Abcam, Cat# ab314109), with rabbit IgG (CST, Cat# 2729) serving as a negative control. After washing the immune complexes, crosslinking was reversed, and the DNA was purified. The binding of KLF5 to the ZDHHC8 promoter was assessed by qPCR using the following primers: forward, 5’-ATGGGTCTGGGCTTCAGAAC-3’, reverse, 5’-TCTCCTCCCGCAGGAAATC-3’. The data were normalized to the input control and presented as relative enrichment.

Luciferase reporter assay

The luciferase reporter assays were conducted using OVCAR-3 cells to evaluate the transcriptional regulation of the ZDHHC8 promoter by KLF5. The 2000 bp upstream region of the ZDHHC8, containing the potential binding sites, was identified through the UCSC Genome Browser. The KLF5 binding site within this promoter region was predicted using the JASPAR database (v2024) (https://jaspar.elixir.no/), which identified a consensus sequence (GCCCCGCCCC). This sequence was subsequently mutated to a non-binding sequence (TGGAGTGGAG) to generate a control construct for functional analysis. Both the wild-type and mutant ZDHHC8 promoter constructs were cloned into the pGL3-Basic luciferase vector. OVCAR-3 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and co-transfected with either the wild-type or mutant ZDHHC8 promoter constructs along with a KLF5 overexpression plasmid or control vector. After 48 h of transfection, luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Beijing, China).

Statistical analysis

In addition to the mentioned statistical methods, GraphPad Prism 9 software was utilized for further statistical analysis. For comparisons between two groups, two-sided independent Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon tests were applied depending on data distribution. For multiple-group comparisons, one-way or two-way ANOVA test was used. Quantitative results from both in vitro and in vivo experiments are expressed as means ± SEM. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistical significance, with significance levels denoted as follows: * for P ≤ 0.05, ** for P ≤ 0.01, and *** for P ≤ 0.001.

Palmitoylation is upregulated in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) and elevated ZDHHC8 predicts poor survival. (a) Heatmap of z-score–normalized ssGSEA enrichment scores for five palmitoylation pathways in HGSOC and normal tissues. Samples are hierarchically clustered, Wilcoxon test significance is indicated. (b) Boxplots of log2(TPM + 0.001) expression for 23 ZDHHC family genes in HGSOC tumor (red) versus normal (blue), with boxes showing the median and interquartile range. (c) Forest plot showing univariate Cox proportional analysis for 23 palmitoyltransferase genes. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown, with * indicate statistically significant prognostic factors for overall survival (OS). (d) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for ZDHHC8 expression, showing overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in the TCGA cohort (top panel) and the integrated GEO cohort (bottom panel). (e) Kaplan-Meier analysis of ZDHHC8 in platin-treated HGSOC patients from the GEO dataset. Left panel, OS, right panel, PFS. (f) Representative immunohistochemical (IHC) images (20×, scale bar = 100 μm) of ZDHHC8 expression in chemotherapy-resistant (R) (n = 10) versus -sensitive (S) (n = 14) tumors with optical density quantification. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

ZDHHC8 impairs cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer. (a) Validation of ZDHHC8 knockdown (shZDHHC8) efficiency in SKOV-3 and CAOV-3 cells using qPCR and western blotting (WB). (b) Dose-response curves for shZDHHC8 HGSOC cells treated with cisplatin (CDDP) at concentrations of 0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µM, with calculated IC50 values. (c) Validation of ZDHHC8 overexpression (oeZDHHC8) in OVCAR-3 cells by qPCR and WB. (d) Dose-response curve for oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 cells treated with increasing CDDP concentrations, with determined IC50 values. (e) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in ZDHHC8 knockdown cells after vehicle or 10 µM CDDP treatment. (f) γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showing DNA damage in vehicle- or CDDP-treated ZDHHC8 knockdown cells. (g) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in ZDHHC8 overexpressing cells following vehicle or 10 µM CDDP treatment. (h) γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showing DNA damage in vehicle- or CDDP-treated oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 cells.

ZDHHC8 reduces cisplatin sensitivity in vivo. (a) Images of xenograft tumors generated from CAOV-3 cells with ZDHHC8 knockdown (shZDHHC8) or control (shNC) following treatment with vehicle or CDDP (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally once weekly for three consecutive weeks). (b) Tumor growth curves of shZDHHC8 CAOV-3 xenografts. (c) Tumor weights of CAOV-3 xenografts were measured at the endpoint of the experiment. (d) Histological analysis of CAOV-3 xenograft tissues using H&E and TUNEL staining. (e) Images of xenograft tumors generated from oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 cells. (f) Tumor growth curves of oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 xenografts. (g) Tumor weights of OVCAR-3 xenografts were measured at the endpoint of the experiment. (H) H&E and TUNEL staining of OVCAR-3 xenograft tumor tissues.

KLF5 upregulates ZDHHC8 expression to impair cisplatin sensitivity. (a) Schematic illustrating the predicted KLF5 binding site within the ZDHHC8 promoter, identified using the JASPAR database. (b) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay confirming KLF5 binding to the ZDHHC8 promoter region. (c) Luciferase reporter assay comparing ZDHHC8 promoter activity in wild-type and mutant constructs upon KLF5 overexpression. (d) Representative immunohistochemical images of KLF5 expression in clinical HGSOC samples (20× magnification). (e) QPCR and WB analysis verifying the efficiency of KLF5 knockdown (shKLF5) and overexpression (oeKLF5), and their effects on ZDHHC8 levels in HGSOC cells. (f) Flow cytometry analysis showing apoptosis levels in 10 µM CDDP-treated shKLF5 HGSOC cells. (g) γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showing DNA damage levels in 10 µM CDDP-treated shKLF5 cells.

KLF5 reduces chemosensitivity by acting through ZDHHC8. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of CAOV-3 cells after individual or combined knockdown of KLF5 and ZDHHC8 under 10 µM cisplatin (CDDP) treatment. (b) γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showing DNA damage in 10 µM CDDP-treated CAOV-3 cells with KLF5 and/or ZDHHC8 knockdown. (c) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in 10 µM CDDP-treated KLF5 knockdown cells with or without ZDHHC8 overexpression. (d) γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showing DNA damage in 10 µM CDDP-treated KLF5 knockdown cells with ZDHHC8 overexpression.

KLF5 knockdown increases cisplatin sensitivity in vivo. (a) Images of xenograft tumors derived from CAOV-3 cells with KLF5 knockdown (shKLF5) following treatment with vehicle or CDDP (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneally once weekly for three consecutive weeks). (b) Tumor growth curves of shKLF5 CAOV-3 xenografts. (c) Tumor weights of shKLF5 CAOV-3 xenografts were measured at the endpoint of the experiment. (d) Histological analysis of CAOV-3 xenograft tissues using H&E and TUNEL staining.

β-catenin acts as a downstream effector of ZDHHC8. (a) Correlation between ZDHHC8 expression and WNT/β-catenin pathway activity48,49,50as determined by ssGSEA. (b) Comparative analysis of β-catenin expression at the mRNA level (qPCR) and protein level (WB) in vehicle- and CDDP-treated HGSOC cells with ZDHHC8 knockdown or overexpression. (c) β-catenin expression level in shKLF5 HGSOC cells following CDDP treatment. (d) Validation of XAV939’s inhibitory effect on β-catenin levels in OVCAR-3 cells. (e) Dose-response curves of CDDP in oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 cells, with or without 10 µM XAV939. (f) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis in oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 cells treated with CDDP, with or without 10 µM XAV939. (g) γ-H2AX immunofluorescence staining showing DNA damage in CDDP-treated oeZDHHC8 OVCAR-3 cells, with or without 10 µM XAV939.

Data availability

The integrated dataset of TCGA and GTEx analyzed during the current study are available in the UCSC Xena database, https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/. The integrated GEO dataset used in this study was pre-loaded and pre-processed in the web-based tool KMplot, http://kmplot.com/analysis/. All data generated or analyzed based on the online datasets and other experiments during this study are included in this published article.

References

Orr, B. & Edwards, R. P. Diagnosis and treatment of ovarian Cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North. Am. 32, 943–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2018.07.010 (2018).

Shetty, M. Imaging and differential diagnosis of ovarian Cancer. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 40, 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2019.04.002 (2019).

Torre, L. A. et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 284–296. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21456 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Trends and age-period-cohort effects on mortality of the three major gynecologic cancers in China from 1990 to 2019: cervical, ovarian and uterine cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 163, 358–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.08.029 (2021).

Bowtell, D. D. et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 15, 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc4019 (2015).

Nag, S., Aggarwal, S., Rauthan, A. & Warrier, N. Maintenance therapy for newly diagnosed epithelial ovarian cancer- a review. J. Ovarian Res. 15, 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-022-01020-1 (2022).

Tavares, V. et al. Paradigm shift: A comprehensive review of ovarian Cancer management in an era of advancements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031845 (2024).

Jayson, G. C., Kohn, E. C., Kitchener, H. C. & Ledermann, J. A. Ovarian cancer. Lancet 384, 1376–1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62146-7 (2014).

DiSilvestro, P. & Alvarez Secord, A. Maintenance treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer: is it ready for prime time? Cancer Treat. Rev. 69, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.06.001 (2018).

Kim, S. et al. Tumor evolution and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-018-0063-0 (2018).

Reid, B. M., Permuth, J. B. & Sellers, T. A. Epidemiology of ovarian cancer: a review. Cancer Biol. Med. 14, 9–32. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0084 (2017).

Foley, O. W. & Rauh-Hain, J. A. Del carmen, M. G. Recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: an update on treatment. Oncol. (Williston Park). 27, 288–294 (2013).

Ko, P. J. & Dixon, S. J. Protein palmitoylation and cancer. EMBO Rep. 19 https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201846666 (2018).

Wang, Y., Lu, H., Fang, C. & Xu, J. Palmitoylation as a signal for delivery. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1248, 399–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3266-5_16 (2020).

Yeste-Velasco, M., Linder, M. E. & Lu, Y. J. Protein S-palmitoylation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1856, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.06.004 (2015).

Jin, J., Zhi, X., Wang, X. & Meng, D. Protein palmitoylation and its pathophysiological relevance. J. Cell. Physiol. 236, 3220–3233. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.30122 (2021).

Zhou, B., Hao, Q., Liang, Y. & Kong, E. Protein palmitoylation in cancer: molecular functions and therapeutic potential. Mol. Oncol. 17, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.13308 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Emerging roles of protein palmitoylation and its modifying enzymes in cancer cell signal transduction and cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 3447–3457. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.72244 (2022).

Fukata, Y., Bredt, D. S. & Fukata, M. in The Dynamic Synapse: Molecular Methods in Ionotropic Receptor Biology Frontiers in Neuroscience (eds J. T. Kittler & S. J. Moss) (2006).

Young, E. et al. Regulation of Ras localization and cell transformation by evolutionarily conserved palmitoyltransferases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01248-13 (2014).

Smith, B. A. et al. Identification of genes involved in human urothelial cell-matrix interactions: implications for the progression pathways of malignant urothelium. Cancer Res. 61, 1678–1685 (2001).

Yuan, M. et al. ZDHHC12-mediated claudin-3 S-palmitoylation determines ovarian cancer progression. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 10, 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.03.008 (2020).

Pei, X. et al. Palmitoylation of MDH2 by ZDHHC18 activates mitochondrial respiration and accelerates ovarian cancer growth. Sci. China Life Sci. 65, 2017–2030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-021-2048-2 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. AMPKalpha1-mediated ZDHHC8 phosphorylation promotes the palmitoylation of SLC7A11 to facilitate ferroptosis resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Lett. 584, 216619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216619 (2024).

Sudo, H. et al. ZDHHC8 knockdown enhances radiosensitivity and suppresses tumor growth in a mesothelioma mouse model. Cancer Sci. 103, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02126.x (2012).

MacDonald, B. T., Tamai, K. & He, X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell. 17, 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016 (2009).

Arend, R. C., Londono-Joshi, A. I., Straughn, J. M. Jr. & Buchsbaum, D. J. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol. Oncol. 131, 772–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.09.034 (2013).

Nusse, R. & Clevers, H. Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169, 985–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Reprogramming of palmitic acid induced by dephosphorylation of ACOX1 promotes beta-catenin palmitoylation to drive colorectal cancer progression. Cell. Discov. 9, 26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-022-00515-x (2023).

Li, M., Zhang, L. & Chen, C. W. Diverse roles of protein palmitoylation in cancer progression, immunity, stemness, and beyond. Cells 12, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12182209

Li, Y. et al. Overexpression of KLF5 is associated with poor survival and G1/S progression in pancreatic cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 11, 5035–5057. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102096 (2019).

Li, J. et al. KLF5 is crucial for Androgen-AR signaling to transactivate genes and promote cell proliferation in prostate Cancer cells. Cancers (Basel). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030748 (2020).

Meyer, S. E. et al. Kruppel-like factor 5 is not required for K-RasG12D lung tumorigenesis, but represses ABCG2 expression and is associated with better disease-specific survival. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 1503–1513. https://doi.org/10.2353/ajpath.2010.090651 (2010).

Chen, Q. et al. Breast Cancer Risk-Associated SNPs in the mTOR promoter form de Novo KLF5- and ZEB1-Binding sites that influence the cellular response to Paclitaxel. Mol. Cancer Res. 17, 2244–2256. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-1072 (2019).

Nakaya, T. et al. KLF5 regulates the integrity and oncogenicity of intestinal stem cells. Cancer Res. 74, 2882–2891. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2574 (2014).

Tang, J. et al. LncRNA PVT1 regulates triple-negative breast cancer through KLF5/beta-catenin signaling. Oncogene 37, 4723–4734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0310-4 (2018).

Luo, Y. & Chen, C. The roles and regulation of the KLF5 transcription factor in cancers. Cancer Sci. 112, 2097–2117. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.14910 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. KLF5 promotes tumor progression and Parp inhibitor resistance in ovarian Cancer. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 10, e2304638. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202304638 (2023).

Gyorffy, B. Discovery and ranking of the most robust prognostic biomarkers in serous ovarian cancer. Geroscience 45, 1889–1898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-023-00742-4 (2023).

Hu, Y. B. et al. Exosomal Wnt-induced dedifferentiation of colorectal cancer cells contributes to chemotherapy resistance. Oncogene 38, 1951–1965. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0557-9 (2019).

Ren, J. et al. CSS-Palm 2.0: an updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 21, 639–644. https://doi.org/10.1093/protein/gzn039 (2008).

McCubrey, J. A. et al. Roles of signaling pathways in drug resistance, cancer initiating cells and cancer progression and metastasis. Adv. Biol. Regul. 57, 75–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbior.2014.09.016 (2015).

Koti, M. et al. Identification of the IGF1/PI3K/NF κB/ERK gene signalling networks associated with chemotherapy resistance and treatment response in high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 13 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-549 (2013).

Chandra, A. et al. Ovarian cancer: current status and strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med. 8, 7018–7031. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2560 (2019).

Cortez, A. J., Tudrej, P., Kujawa, K. A. & Lisowska, K. M. Advances in ovarian cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 81, 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-017-3501-8 (2018).

Markman, M. et al. Second-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 9, 389–393. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.389 (1991).

(MsigDB), M. S. D. (2023). https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Hanzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-7 (2013).

Xena, U. (2023). https://toil.xenahubs.net

Denkert, C. et al. A prognostic gene expression index in ovarian cancer - validation across different independent data sets. J. Pathol. 218, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.2547 (2009).

Lanczky, A. & Gyorffy, B. Web-Based survival analysis tool tailored for medical research (KMplot): development and implementation. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e27633. https://doi.org/10.2196/27633 (2021).

JASPAR. (2023). https://jaspar.elixir.no/

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 9, 671–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089 (2012).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 82172934).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. X.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Resources, Visualization. X. L.: Writing - Original Draft, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Validation. W. Z.: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. Y. T.: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This research was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethic Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed an informed consent according to institutional guidelines. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Rat&Mouse Biotech Co.,Ltd, and this study is performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, Z., Li, X., Zhou, W. et al. KLF5-regulated ZDHHC8 reduces chemosensitivity in high-grade serous ovarian cancer through β-catenin signaling. Sci Rep 15, 26176 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11845-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11845-7