Abstract

Regular inspection of the health of railway tracks is crucial to maintaining reliable and safe train operations. Some factors including cracks, rail discontinuity, ballast issues, burn wheels, super-elevation, loose nuts and bolts, and misalignment developed on the railways due to pre-emptive investigations, non-maintenance, and delay in detection pose grave threats and danger to the safe operation of railway transportation. In the past, manual inspection was performed for the rail track by a rail cart which is both prone to error and inefficient due to human biases and error. Several train accidents are reported in Pakistan; it is important to automate these techniques to avoid such train accidents for the safety of countless lives. This study aims to enhance railway track fault detection using an automatic rail track fault detection technique with acoustic analysis. Moreover, the proposed method contributes to making the dataset large by using the CTGAN technique. Results show that acoustic data may help to determine the railway track faults effectively and logistic regression is used to perform the classification for railway track faults with an accuracy of 100%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The railway network is a highly essential transportation conduit in various developing nations, such as Pakistan, and is utilized to satisfy public transit demands. The railway structure is crucial for trade and supply networks1. The railway market has gotten stronger, opening up new opportunities for the country’s public and economy. According to2, the railway industry’s annual report from 2016 to 2018 showed a growth rate ranging from 1.3% to 2.4%. As a result, high-performance railway operations are essential to ensure that the railway runs continuously and that passengers are safe. The railway system is getting more burdened and complex as the number of train passengers grows. According to3, mechanical forces and environmental factors accelerate the deterioration of train rails. The railway tracks are crucial components of the railway network. Rail track inspection helps decrease accidents, injuries, and deaths4. From 2013 to 2020, the registered train accidents were 127 due to rail track faults according to the annual reports in Pakistan4. People including students, tourists, and commuters use trains for traveling in Pakistan. From 2012 to 2017, a total of 757 train accidents have been reported5. Additionally, 22 goods and 16 passenger trains were derailed in 2014, and 37 goods and 37 passenger train accidents were reported in 2015. In 2019, 11434 railway accidents were recorded, causing 937 casualties and 7730 injuries6. However, the train accident ratio is higher in under-developing countries7. The railway network contributes to the Pakistani economy as it has a huge network in the North-South corridor that links the seaport of Karachi with the country’s main production centers and population8. In 2020, 152 train accidents are reported causing 19 deaths9. In 2021, 32 casualties and 64 injuries were recorded in railway accidents9.

Timely detection and proper inspection of faults may protect several human lives and reduce the financial losses for railway systems10. However, the maintenance and inspection of railway tracks is a time-consuming and expensive activity. Several non-destructive evaluation (NDE) methods for railway track inspection have been applied including detection using phased array technology11. Eddy current testing12, guided wave detection13, ultrasonic testing14, and other techniques have been the focus of rail track inspections. However, there has been a recent surge in enthusiasm for employing machine learning models, the Internet of Things (IoT), and deep learning networks in these inspections. These advanced technologies aim to enhance the speed, precision, uniqueness, and overall success of non-destructive evaluation (NDE) approaches. The integration of acoustic transducers15 and high-speed cameras16 with machine learning classifiers is becoming common to modernize traditional inspection methods. In particular, hand-crafted feature engineering (HCFE) has been utilized in audio and image-based machine learning applications. Nevertheless, HCFE demands domain-specific expertise, extensive problem-solving, and system modifications to optimize performance (PS18). Moreover, railway track classification and inspection have three main stages. Firstly, preprocessing of ‘wav’ files is performed to eliminate the undesired sounds. Secondly, feature extraction is performed with spectrograms. Thirdly, the classification method is trained to detect rail track faults.

Maintaining a reliable and safe rail network demands uninterrupted train operations, which entails extensive monitoring of hundreds of thousands of kilometers of track. This endeavor requires substantial investments of time and money. Timely and sufficient maintenance of railway tracks is crucial; any failures can disrupt train services, leading to potential financial and human consequences17. Crack identification is very important to run the system rapidly and efficiently. In Pakistan, track inspection is currently conducted using a railway cart, where human specialists manually assess the track to identify areas requiring repairs. Recognizing the critical importance of track inspection, this study introduces and integrates an intelligent automated system for analyzing the condition of train tracks. In summary, the study offers the following contributions:

-

This study investigates the use of various machine learning and deep learning models for autonomously evaluating railway tracks, focusing on distinguishing between three distinct track conditions: wheel burn, superelevation, and standard track.

-

A significant dataset is also produced for studies with the acoustic signals from an ECM-X7BMP microphone that was collected over one year.

-

The Mel-frequency cepstrum coefficients (MFCC) and Constant-Q transform (CQT) characteristics of audio signals are combined with various classifiers to automatically detect track problems. Conditional GAN (CTGAN) is also used to create an equal amount of samples for each error.

The sections of this paper are grouped as follows: Section 2 provides a summary of several forms of fractures seen in railway tracks, as well as major studies on identifying defects in rail tracks. Section 3 describes data collecting procedures, equipment, and suggested study strategy. Section 4 presents the findings and comments, while Section 5 provides the conclusion.

Related work

Track inspection is an essential task that has been adopted periodically to control the conditions of rail tracks and avoid train accidents. Geometric inspection and structural inspection are two main classes for the inspections of rail tracks18. Structural checks are performed to detect structural faults such as wheel burn, superelevation, or other structural issues. Geometric inspections are used to identify geometric anomalies such as rail misalignment and other comparable degradation. Furthermore, geometric anomalies are caused by structural flaws, which can lead to train accidents. The authors explained various geometric and structural flaws in19.

Researchers worked on the detection of geometric defects with an SVM model in20. The RAS problem-solving competition 2015 dataset was used for experimentation. The study considered some severe geometric defects which may increase the geometric defects. To detect structural defects, a structural inspection is performed using shallow machine learning methods in this study. SVM was used in this study which also worked on a novel parameter called positive and un-labeled learning performance (PULP). Moreover, PULP was applied to check the performance of models on different datasets comprising faulty results. In21, experimentation was performed to detect faults on railway tracks. Both Support SVM and CNN were utilized in this study for analyzing an image-based dataset. Rail fasteners are classified as missing, good, or broken. This technique showed improved accuracy in detecting defects in rail fasteners and ties.

The study22 investigated fault detection using traditional acoustic-based systems, enhancing performance and reducing train accidents through deep learning methodologies. Additionally, the research concentrated on LSTM, 2D convolutional, and 1D convolutional approaches. Various types of faults, such as wheel burn, superelevation, and normal tracks, were identified in this study. Experimental analysis was conducted on a real acoustic dataset to detect rail track faults.LSTM model shows improved results with 99.7% accuracy. In the study23, local binary pattern (LLBP) was employed on railway images to classify track fasteners. Gabor filters24, SVM25, and edge detection26 methods were utilized to identify fasteners in railway images. Faster Region-based CNN was utilized for detecting rail track faults in27. CNN and ResNet-50 were applied in study28 to detect structural defects and damages, particularly related to broken rail fasteners. The study utilized Haar-like feature sets, including geometric features for fasteners, achieving a 94% accuracy with CNN and 94.4% accuracy with ResNet-50. Additionally, various classification methods, including SVM, GNB, KNN, RF, Adaboost, and Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT), were tested and evaluated to detect and analyze missing clamps in the fastening structure in29.

The categorization of railway cracks with acoustic-emission waves based on a multi-branch CNN is discussed in30. The railway fastener defects are identified from images using CNN31, residual network32, GAN, faster region-CNN33, and point cloud deep learning (PCDL)34. Dynamic stiffness for rail pads was anticipated with machine learning techniques including KNN, multi-linear regression, regression tree, gradient boosting, RF, SVM, and MLP35. Feature extraction approaches have also been investigated for rail track fault detection.

The study36 introduced tree-based classification approaches such as RF and DT which performed a comparison of deep learning techniques for rail track inspections. The authors proposed a new RF-based approach that is used to combine LMD, TFD, and TD feature extraction for the detection of track slab deformation. In37, an automated inspection technique based on IoT is presented for rail track fault detection. Acoustic data is used to rail track fault classification including wheel burn, crash sleeper, loose nuts, and bolts, low joint, creep, and point and crossing. The experimental results showed that acoustic data may successfully support selective track defects and localized these defects in real time. This method achieved a 98.4% accuracy with MLP.

Materials and methods

This section discusses dataset collection and strategy, feature extraction techniques, machine learning methods for classification, and the recommended approach.

Dataset collection

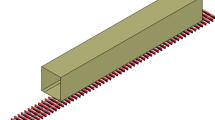

The dataset holds crucial importance in the automated identification of faulty railroad tracks. Illustrated in Figure 1, the mechanical cart provided by officials at the Rahim Yar Khan station of Pakistan Railways Khanpur district was utilized for collecting this dataset. A setup was arranged on-site at Khanpur’s train station to gather the necessary data. Positioned at a safe maximum distance of 1.75 inches from the point of contact between the wheel and the track, two microphones were installed. These microphones were affixed to the right and left sides of the cart for data collection purposes. The propulsion of the mechanical cart was facilitated by a generator, which operated at an average speed of 35 km/h to drive the cart’s engine.

The audio data collection did not specify the geographic location. Two ECM-X7BMP Unidirectional electric condenser microphones, equipped with 3-pole locking small plugs, were mounted on the left and right wheels of the railway cart. These microphones possess an output impedance of 1.2 k and a sensitivity of 44.0 3 dB. Additional specifications of the microphones are detailed in Table 1.

Both microphones, positioned in separate locations, serve the purpose of recording. A single trigger button activates both microphones simultaneously to initiate data recording. The recorded data is stored as 16-bit audio files with the ”.wav” extension. The Sony ECM-X7BMP microphone is employed for this data collection process. As depicted in Figure 1, a metal strip is fashioned with one end serving as a secure mount for the microphone, while the other end is firmly screwed onto the cart. Foam or fur material is utilized to protect the microphone diaphragm from air currents. Without a windshield, wind or breathing can cause loud pops in the audio transmission.

Foam windshields are employed to mitigate cart vibrations, preventing their transmission to the microphone. Typically serving as the primary defense against wind noise, these windshields comprise open-cell foam covers surrounding the microphone. This design disperses and diminishes the acoustical energy of wind striking the microphone capsule, reducing low-end vibration. Streamlining these windshields is essential to ensure that wind flows around them rather than directly into them. Although some vibration remains uniformly present in the entire audio signal, it does not significantly impact the detection of faulty signals, as it is also present in normal track sounds. The windshields intercept air gusts before they can interact with the microphone diaphragm, effectively minimizing their impact. Using this setup, 720 audio recordings, totaling 17 seconds in duration, were captured during data collection at a sampling frequency of 22,050 Hz. Subsequently, the recordings were manually tagged to organize the dataset. They were then segmented into 758 frames using a window length of 1024 and 512 hops, based on the collected recordings.

Figure 2 presents the waveform and spectrogram of three different sample audio recordings: ‘wheel burn’, ‘superelevation’, and ‘standard’ track conditions. The waveform illustrates the amplitude variations over time, while the spectrogram provides a time-frequency representation, highlighting the intensity of different frequencies. The visual differences between these three track conditions are evident in both representations. The Mel spectrogram provides insights into the distribution of sound intensity across various frequency ranges. For instance, in the 64–256 Hz frequency range, the normal track sound exhibits an intensity level between approximately −30 dB and −60 dB. In contrast, the superelevation track demonstrates a higher intensity, ranging from −2 dB to −20 dB. Meanwhile, the track with wheel burn shows a broader variation in noise intensity, spanning from −20 dB to −72 dB within the same frequency range. These distinctions highlight the unique spectral characteristics associated with each track condition.

Proposed methodology for track fault detection

The proposed methodology for fault detection has been utilized in three scenarios. The architecture diagram of the proposed methodology is presented in Figure 3. In the first stage, features from the audio signal are extracted. In this study, we extract two types of features: one is MFCC while the other is CQT features. These feature sets are then divided into train and test parts.

The model is trained using a training dataset while evaluation is carried out using a testing dataset using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. The acoustic features are then used to train machine learning and deep learning classifiers. The data size for each sample is 720 per class and 40 MFCC features are extracted from each sample. Along with MFCC features, another feature extraction technique i.e. CQT is also applied for models’ training.

The architecture diagram for scenario 2 is shown in Figure 4. In order to enhance track fault detection accuracy, a feature fusion technique is applied where the features are combined. For that purpose, the best features are selected for model training. As a result, accuracy is improved for rail track fault detection.

The data size is small to train machine learning algorithms, so, data are re-sampled by using CTGAN, and 400 samples are created for each class. These Samples are then split into train and tests with ratios of 0.8 to 0.2. The sample data distribution before and after the training and testing split is presented in Table 2. Machine learning and deep learning models are then trained by these training samples and then test samples are applied for prediction. The Architecture diagram for Scenario 3 has been explained in Figure 5.

Obtaining implementation code

For reproducibility of the proposed approach, the implementation code has been made public on the GitHub, and can directly be accessed using the link https://github.com/Arehmans/railways.

Experiment details

Railway track inspection professionals from Pakistan Railways discovered and validated the damaged tracks. The cart was driven over the damaged rails, and the following tracks’ audio signals were recorded:

-

Normal track (Unfaulty sound)

-

Superelevation

-

Wheel burn

The data is categorized as follows with respect to labels:

-

Normal track - labeled as 0,

-

Superelevation - labeled as 1,

-

Wheel burn - labeled as 2

Wheel burns38 occur when the driving wheels of locomotives skid along the rail surface, typically in areas with steep grades or after rainfall, due to insufficient hauling power to bear the train load, resulting in the rail surface melting. Superelevation39 refers to the gradual elevation change between the rails of a railway track, creating banked turns that allow vehicles to navigate curves at higher speeds compared to level tracks, especially crucial on curved sections.

Both wheel burns and superelevation are recognized as critical factors contributing to railway derailments40,41. Railways face various track issues such as cracked or broken rails, faulty welds, broad gauges, missing nuts and bolts, and disjointed tracks. However, this study concentrates specifically on wheel burns and superelevation, deferring other concerns for future research. The selection of the experimental route was deliberate; it was a heavily trafficked mainline, and during the study period, it was only affected by these two issues.

Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients(MFCC)

MFCC features are discussed primarily for the detection of monosyllabic words within continuous speech rather than for speaker identification. The approach outlined in the paper aims to mimic the human ear’s functioning, leveraging the assumption that the human ear is a reliable recognizer of speakers. To capture the phonetically significant aspects of speech, frequency filters are organized linearly at lower frequencies and logarithmically at higher frequencies, forming the foundation of MFCC features.

Speech signals contain tones with varying frequencies, and the Mel scale is used to perceive pitch. Under the Mel scale, each tone corresponds to an actual frequency denoted as f (in Hz). Below 1000 Hz, the Mel frequency scale demonstrates linear frequency spacing, while beyond 1000 Hz, it adopts logarithmic frequency spacing. A reference point is set by a 1 kHz tone registering 40 dB above the perceptual hearing threshold, equivalent to 1000 Mel. In equation form, it can be written as

where mel(f) is the frequency in mels and f is the frequency in Hz. The final feature vector space F of size 40 is obtained as follows

where i is the \(i^{th}\) frame and N is the total number of frames i.e., 758.

Constant-Q-transform

Constant Q transformation is a technique to convert sound or signal data into frequency-domain data42. CQT mainly shows good performance for both perceptual and music processing. It is the same as Fourier transform (FT) whereas it has additional advantages. Firstly, it applies a logarithmic scale to ensure wide and narrow bandwidths in high-frequency and low-frequency regions. CQT is more useful than FT and reports low resolution in regions of low frequency. Additionally, the bandwidth is proportionally divided by the central frequency, making it simple to discriminate even if the frequency spans many octaves. Figure 6 provides a logarithmically spaced frequency resolution, offering a detailed representation of spectral content over time. The intensity variations indicate distinct spectral characteristics across different track conditions, with clear differences in frequency distribution and energy concentration. In the Wheel Burn case, higher intensity levels (−5 dB to 0 dB) appear as localized bright spots, indicating sudden energy spikes caused by irregular vibrations and impacts from wheel defects. This suggests a non-uniform frequency distribution, revealing abnormal disturbances in the track. In contrast, the Superelevation case exhibits moderate intensity (−10 dB to −20 dB) with a more evenly spread pattern, reflecting systematic frequency shifts due to track banking. This results in a smoother transition of forces acting on the track rather than abrupt variations. Lastly, the Normal Track serves as a baseline, showing lower intensity levels (−30 dB to −50 dB) with minimal bright spots, indicating uniform frequency distribution and the absence of major external disturbances. By analyzing these intensity variations, we can effectively diagnose track conditions, distinguishing between defects, structural features, and normal behavior.

Constant Q transformation is used to analyze the frequency domain and can be estimated using the following equation43.

where w is used for the sequence number of the spectral line and q is for the quality factor and its value is equivalent to the result for center frequency to the bandwidth. The center frequency is an exponential distribution. The window function n can be calculated as

where gs is used for sampling frequency, g is used for the low frequency of the musical signal, gw is the frequency value with spectral line and C is used for a number of spectral lines in an octave.

As an octave is separated by 12 semi-tones using an average temperament of 12, C mostly inputs a value for 12 or twelve multiple. However, CQT spectrum-frequency and scale-frequency have similar exponential distribution formula43, CQT is used to analyze and process the musical signals. Therefore, the main issue of constant Q transformation is that the computation speed is very slow.

Composite travel generative adversarial network

Composite travel generative adversarial network is a GAN-based technique that is used for tabular data and sample rows from the distribution44. The CTGAN approach is made up of 2 GAN networks including the sequence model and the tabular model. The main use for the tabular components is learning the joint distribution for elementary socio-demographic attributes. On the other hand, the sequential component is used to learn the distribution of trips that are selected by an individual per day. The properties include correlated features, different mixed data types like continuous or discrete features, problems in learning from higher sparse vectors, and potential mode failure due to the highest class imbalance. To solve these types of problems, we select composite travel generative adversarial network as the essential generative technique. CTGAN has many additional hyperparameters that are used to control its learning behavior and may impact the classifier performance for the computational time and quality of the generated data. CTGAN system considers that every component is employed as an independent network that is trained with its parameters based on data distribution. The presented method adopts just tabular components for the CTGAN approach and also trains the parameters. Conditional sampling only allows sampling using a conditional distribution with the CTGAN method, which means we may generate just values to satisfy the definite conditions. To overcome the multimodal and non-Gaussian distribution, the proposed method invents the mode-specific normalization in CTGAN.

Supervised machine learning models

The proposed approach uses several machine learning models to detect rail track defects. SVM, RF, RNN, DT, LR, NB, voting classifier, KNN, CNN, GRU, and LSTM are used in this study. These models are fine-tuned to optimize their performance.

Decision tree

The Decision Tree (DT) method, as discussed in45, is a supervised classification technique characterized by its non-linear structure resembling a tree. In the context of evaluating faults and defects in transformers, the DT algorithm proves useful. In DT, connection points between branches represent conditions for differentiation, while the leaf nodes signify classifications. The classification process involves determining whether data meets the conditions outlined at each node, selecting appropriate branches to proceed, and repeating these steps until a leaf node is reached. In our study, DT is utilized with 2 hyperparameters. We specifically employ the ”max_depth” hyperparameter, set to 250, which restricts the decision tree’s growth to a maximum depth of 250 levels to prevent overfitting and manage complexity.

Support vector machine

SVM is a versatile linear model widely adopted for regression, classification, and various other tasks across numerous research articles46,47. It operates by dividing sample data into distinct classes using a set of hyperplanes or a single hyperplane in a g-dimensional space, where g represents the number of features. SVM’s primary function is classification, aiming to identify the ”best fit” hyperplane that effectively separates different classes. In this study, we employ a ’linear’ kernel for the SVM classifier, which is commonly utilized when dealing with datasets featuring a high number of features. The SVM classifier offers two key advantages: high speed and enhanced performance even with a limited number of samples. For our current investigation, two hyperparameters are employed: a regularization parameter (C) set to 1.0 and the use of a ’linear’ kernel for experimentation purposes.

Random forest

RF is a classifier based on decision trees known for its ability to make accurate predictions by combining multiple weak learners, as described in48. It employs the bagging method, where various types of decision trees are utilized during training, employing numerous bootstrap samples, as outlined in49. These bootstrap samples are generated by randomly selecting subsets from the training dataset with replacement, maintaining a similar sample size as the original dataset. Ensemble classification is achieved by training multiple models and aggregating their results through a voting process. Several contributors have introduced ensemble learning methods, including boosting and bagging, which are widely utilized, as discussed in50,51,52. Bagging, specifically, focuses on reducing variance in classification by training models on bootstrap samples. The definition of RF is as follows:

where \(dt_1, dt_2, dt_3,...,dt_n\) are the predictions by decision trees and \(rf_p\) is prediction by RF using majority voting. We employed RF with three hyperparameters, as outlined in Table 3. The parameter n_estimators was set to 200, indicating that RF generated 200 decision trees for the prediction process. Additionally, max_depth was set to 50, limiting the depth of the decision trees to a maximum of 50 levels to prevent complexity and over-fitting.

Logistic regression

LR as referenced in53, is a statistical classifier employed to address classification problems. When dealing with classification tasks where target variables are well-defined, logistic regression emerges as the primary choice. LR analyzes the association between one or more independent variables and categorical dependent variables by estimating probabilities using a logistic function. The logistic function, typically represented by a sigmoid curve, is defined as follows:

where E is the classification53, Euler number u0 is used for the value of the sigmoid mid-point, h is the maximum value of the curve, and n is used for the steepness of the curve. LR performs better on binary classification and demonstrates improved performance for the text.

Naive Bayes

NB classifier is a supervised learning technique that is based on the Bayes formula and used to solve classification issues54. NB is essentially applied to detect faults in the rail track. NB is one of the easiest and most effective classifiers that helps to build machine learning-based methods that can predict quickly. NB is a probabilistic model which means it performs prediction based on probability for an object. Suppose a set of d vectors \(E = {e1,e2,...,ed}\) and performs classification along a set F of p classes \(F = {f1,f2,...,fp}\), Bayesian models estimate the probabilities for every category Fi given an Ej is described in the below equation54

where \(P(e_i)\) is the probability and picked randomly has vector \(e_i\) as its demonstration that belongs to \(f_k\). To estimate the \(P(f_k|e_i)\), NB considers that the probability for a given value is independent. NB shows improved results than other classifiers. Additionally, only values are used as the predictors, the simplification of naive allows computing the model for data that is associated with this technique. It is possible to define \(P(f_k|e_i)\) as the product for the probabilities of every term that appears using this simplification. However, \(P(f_k|e_i)\) is estimated using equation54.

K Nearest Neighbors

KNN classifier stands out as the most straightforward and non-parametric supervised machine learning technique, utilized for regression, classification, and addressing missing value imputation problems54. Its approach involves storing all available data and determining the classification of a data point based on similarity. During the training phase, the KNN algorithm solely retains the dataset and assigns the data to a category highly resembling the new data. To precisely define the nearest neighbors, a distance metric such as Manhattan or Euclidean distance is computed54. KNN is alternatively known as a lazy or instance-based learner. However, it’s worth noting that KNN cannot predict values that fall outside the range of the sampled data.

Ensemble classifier

Ensemble voting is a voting classifier that combines several classifiers into a single model which is more robust than individual models55. For the current study, hard voting is used. Every model votes for a category in the hard voting and the category with the maximum votes wins. Every model in soft-voting allocates a probability value to every data point that belongs to a specific target category. In the presented model, we combine LR, GNB, and SVC classifiers into a single method.

Deep learning models

Besides using machine learning models, several deep learning models are used.

Long short-term memory

LSTM as referenced in56, resembles RNN (Recurrent Neural Network) but incorporates efficient memory cells designed to either forget or retain information. It addresses the problem of long-term dependency by employing a chain of RNN modules. The LSTM architecture includes four gates: the update gate, output gate, forget gate, and input gate. The forget gate determines whether the information is discarded from the cell state, while the input gate, consisting of a tanh layer and a sigmoid layer, determines which values will be modified. The update gate refreshes the old cell state with the value derived from the input gate. Finally, the output gate is utilized to determine the value to be outputted from the layer56.

where \(G\_L\) denotes the weight matrix and \(A\_R\) is used for the bias vector. Suppose \(R\_L\) is a number between 0 and 1, then 0 indicates that the value is to forget and 1 indicates to keep the value.

where \(Y\_P\) and \(Y\_w\) are used for weight matrices and \(A\_L\) and \(A\_W\) are used for bias vectors. For output, \(P\_L\) and \(W\_L\) are used.

where \(R\_L\) is used to decide which information is to be forgotten. \(P\_L * W\_L\) chooses the total number of values that are used to modify the cell.

where PE is used to decide which is the output state. The new cell state WL is multiplied by EL. The tanh function is used to achieve HL which is the output of PE. The presented model used LSTM which takes the least time for training. LSTM is the most efficient method than other machine learning techniques.

Convolutional neural network

CNN is mostly used to deal with the variability of 2D shapes57. This architecture is tested for feature extraction of images. CNN contains two layers including the convolution layer and the pooling layer. The convolutional layer is used to perform convolution of the previous layer using the sliding filter to attain the output feature map, where \(F_c^{de}\) denotes the \(p^{thoutput}\) feature map in de layer, \(j_l^{(de-1)}\) is used for \(l^{th}\) input feature map in \((de-1)\) layer. \(\phi\) is used for the sigmoid function that is employed as the network’s activation function. Both \(Y_{pl}^{ae}\) and \(P_p^{ae}\) are used for filters that create the training parameters of convolutional layers as in bellow equation57

To minimize the feature-map resolution and sensitivity for output, the pooling layer is used. The max pooling is commonly used for pooling in CNN. The max pooling is described58 as in the bellow equation.

where \(H_p^{di}\) shows the \(p^{th}\) output feature map of pooling layer.

Recurrent neural network

RNN model59 is used to save the output for specific layers and feedback to the input in sequential form to predict the output. RNN is considered to handle the sequential data.

RNNs memorize the previous inputs due to internal memory. It simulates a discrete-time dynamical system that has xe for the input layer, ye for the hidden layer, and ze for the output layer, and e is used to denote time. The dynamical model is defined as in equation and bellow equation59

where \(G_y\) and \(G_0\) are functions that are used for state transition and output respectively. Each function is parameterized by a set of parameters as \(\theta y\) and \(\theta 0\).

Gated recurrent unit

GRU represents the next evolution of RNNs, utilizing the hidden state for information transmission. Unlike LSTM, GRU incorporates only two gates: an update gate and a reset gate60. The update gate functions similarly to the input and forget gates in LSTM, determining which information to discard and what new information to incorporate. On the other hand, the reset gate is responsible for determining the extent to which information should be forgotten.

Results and discussion

The experiments are conducted using the Google Colab service alongside a Python Jupyter Notebook. Librosa is employed to extract MFCC and CQT features, while machine learning models utilize the sci-kit-learn package and deep learning models utilize the TensorFlow library.

An equal number of data points for each class are used for experiments. The dataset was structured to ensure uniform representation across all categories including normal track (0), superelevation (1), and wheel burn (2), to prevent class imbalance and ensure fair model training and evaluation. Performance evaluation of the classifiers is carried out using standard parameters such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, which are computed using the following equations.

Results of machine learning classifiers using MFCC features

Table 4 depicts the accuracy results of different machine learning models using MFCC features. Several models have been applied for experiments including DT, SVM, KNN, LR, NB, RF, and voting classifiers. Accuracy results for DT, SVM, KNN, LR, and NB are 96%, 99%, 85%, 97%, 78%, and 97%, respectively. Experimental results show that tree-based models like DT and RF perform best with accuracy results of 96% and 99%, respectively. While regression and probabilistic-based models perform poorly like NB and KNN yield 78% and 85%, respectively. The accuracy of the voting classifier with hard and soft voting is 98%.

Results of machine learning classifiers using CQT features

Table 5 shows the performance of different machine learning models using CQT features. Accuracy scores for DT, SVM, KNN, LR, NB, and RF are 96%, 99%, 85%, 97%, 78%, and 97%, respectively. Results demonstrate that tree-based models like DT, RF, and liner based models perform best with accuracy scores of 95%, 97%, and 93% as compared to regression and probabilistic-based models like NB and KNN with 87% and 72% accuracy scores, respectively. The liner-based algorithm also performs well with an accuracy of 93%. Accuracy of the voting classifier with hard and soft voting yield 95% and 94% accuracy, respectively.

Results of classifiers using hybrid features

Feature fusion is a technique that is formulated with multiple features that are extracted from the same dataset. The benefit of feature fusion is the increased versatility in feature sets; different types of features can be extracted and used for model training. In Table 6 accuracy of different machine learning models is reported using a fusion of MFCC and CQT. Classifiers like DT, SVC, KNN, LR, NB, and RF yield accuracy scores of 93%, 95%, 85%, 93%, 47%, and 97%, respectively. Probability-based models yield less accuracy for all scenarios.

Results of machine learning classifiers using MFCC features with CTGAN

Data augmentation methods like GAN create new data samples. GAN creates distinctive samples that imitate the feature distribution of the original dataset using random noise taken from latent space. Table 7 displays the accuracy results of classifiers using MFCC features along with CTGAN. As CTGAN techniques create more sample features with the big size of the dataset models can be better tuned and results are improved substantially. SVC, KNN, LR, NB, RF, and voting classifiers with hard and soft voting yield 100% accuracy after applying CTGAN while the performance of DT is decreased to 94%.

Results of machine learning classifiers using CQT features with CTGAN

In Table 8, the performance of machine learning classifiers with CQT features along with the augmentation technique CTGAN is evaluated. LR, NB, RF, SVC, and voting classifier yield accuracy results of 100% while DT and KNN perform less with 92% and 71% accuracy, respectively. Overall, the performance of probabilistic classifiers is increased.

Results of machine learning classifiers using Hybrid features with CTGAN

We have performed experiments along with a combination of both features MFCC and CQT after data augmentation using CTGAN and results are given in Table 9. Different machine learning classifiers are trained and accuracy results for SVM, KNN, LR, NB, and voting classifiers indicate a 100% accuracy. DT shows poor performance with an 85% accuracy because it is a Singleton algorithm and when data size increases the complexity level is also increased resulting in a decrease in its performance.

Results of deep learning classifiers using MFCC and CQT features

Table 10 depicts the accuracy results of different deep learning models using MFCC and CQT features extracted from the audio signal with an 80 to 20 train test ratio.

Deep learning models have been applied in this experiment including LSTM, CNN, RNN, and GRU. Results show that LSTM, CNN, RNN, and GRU models show the accuracy of 33%, 93%, 72%, and 89%, respectively. While with CQT features deep learning classifiers yield 36%, 89%, 63%, and 88%, respectively. The overall performance of deep learning classifiers is lower as compared to machine learning classifiers because of dataset size. Deep learning models perform best on large datasets.

Results of deep learning classifiers using MFCC and CQT with CTGAN

Table 11 shows the results for deep learning models after data augmentation is performed using CTGAN and MFCC and CQT features are used for model training. For MFCC features with augmentation, LSTM, CNN, RNN, and GRU yield 48%, 100%, 76%, and 100% accuracy, respectively. From the results, it can be observed that the models’ performance is enhanced as the dataset size is increased. Similarly with CQT features with augmentation, accuracy for LSTM, CNN, RNN, and GRU is 40%, 100%, 51%, and 100%, respectively. The accuracy is also improved in this case.

Results of deep learning classifiers using hybrid features and hybrid features with CTGAN

Table 12 shows results for two types of experiments; in the first part, a fusion of both MFCC and CQT is used to train deep learning classifiers while the second part involves experiments with feature fusion from CTGAN-generated data. For the first scenario, the accuracy results for LSTM, CNN, RNN, and GRU are 36%, 89%, 63%, and 88% respectively. Results show a slight improvement as compared to the single-feature extraction technique. On the other hand, results for the second part are much better with 40%, 100%, 78%, and 100% accuracy for LSTM, CNN, RNN, and GRU, respectively. Figure 7 shows the accuracy scores comparison between all approaches.

Comparison of accuracy scores: (a) Results of machine learning classifiers with MFCC, CQT, and hybrid features, (b) Results of deep learning classifiers with MFCC, CQT, and hybrid features, and (c) Results of machine learning classifiers with MFCC, CQT, and hybrid features using GAN data, and (d) Results of deep learning classifiers with MFCC, CQT, and hybrid features using GAN data.

K-fold cross-validation results

We have also performed k-fold cross-validation to check the performance of the model that is outperformed and gives a 1.00 mean accuracy score with +/−0.00 standard deviation using the proposed approach. The results of our approach using 10-fold cross-validation are the same as per the train test split method. The results of K fold cross-validation with and without CTGAN are shown in Tables 13 and 14. After applying CTGEN with feature extraction techniques the machine learning models improve the accuracy which shows that CTGAN helps to generate enough data for the learning models.

Comparison With existing studies

Several studies have worked on the detection of rail faults using machine learning approaches; some of these studies used the same dataset. For the studies which used the same dataset we compared their results while for those which used other datasets, we deployed their approaches on the currently used dataset and performed experiments for a fair comparison. The study61 performed experiments on the same dataset while the study37,51,57 carried out experiments on other datasets for railway track fault detection. So we deploy the proposed approaches in37,51,57 using the currently used dataset and show the comparative performance in Table 15. The results show the significance of the proposed approach indicating the superior performance of the proposed approach. This study focuses on dataset size which is ignored by previous studies which elevated the performance of the machine learning models. In addition, we also deployed hybrid features while most of the existing studies only used MFCC features. The use of hybrid features helps to achieve better results than merely using MFCC features.

Conclusions and future work

The railway network serves as the backbone of today’s transportation system and its regular operations are very important for the transportation of goods and humans. Cracks, ballast issues, burn wheels, superelevation, etc. can disrupt railway tracks and cause financial and human losses. Automatic detection of such faults can avoid laborious and error-prone manual fault detection. Contrary to existing studies that rely on MFCC features, this study proposes the use of hybrid features including MFCC and CQT features with an enlarged audio dataset and shows improved performance with an ensemble model. In addition, using the CTGAN model for generating additional samples yields better performance than existing state-of-the-art approaches for railway track fault detection. An accuracy of 100% can be obtained using CTGAN and hybrid features.

Data availability

”The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.”

Code availability

The implementation code is publicly available at the following link: https://github.com/Arehmans/railways

References

Kolar, P., Schramm, H.-J. & Prockl, G. Digitalization of supply chains: focus on international rail transport in the case of the czech republic (2020).

Apking, A. Worldwide market for railway industries study: Market volumes for oem business and after-sales service as well as prospects for market developments of infrastructure and rolling stock. SCI Verkehr GmbH: Köln, Germany, 7 (2018).

Chenariyan Nakhaee, M., Hiemstra, D., Stoelinga, M. & Noort, M.v. The recent applications of machine learning in rail track maintenance: A survey. In: International Conference on Reliability, Safety, and Security of Railway Systems, pp. 91–105 (2019). Springer.

Imdad, F., Niaz, M.T. & Kim, H.S. Railway track structural health monitoring system. In: 2015 15th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), pp. 769–772 (2015). IEEE.

Wosniacki, G. G. & Zannin, P. H. T. Framework to manage railway noise exposure in brazil based on field measurements and strategic noise mapping at the local level. Science of the Total Environment 757, 143721 (2021).

Asada, T., Roberts, C. & Koseki, T. An algorithm for improved performance of railway condition monitoring equipment: Alternating-current point machine case study. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 30, 81–92 (2013).

Mao, B. & Xu, Q. Railway accidents. In: Routledge Handbook of Transport in Asia, pp. 94–122. Routledge, ??? (2018).

Jahan, N., Khan, M. I. & Naqvi, K. A. Disaggregating the demand elasticities of rail services and its influencing factor in pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Social Research 4(2), 702–716 (2022).

Hashmi, M. S. A. et al. Railway track inspection using deep learning based on audio to spectrogram conversion: an on-the-fly approach. Sensors 22(5), 1983 (2022).

Nelwamondo, F.V. & Marwala, T. Faults detection using gaussian mixture models, mel-frequency cepstral coefficients and kurtosis. In: 2006 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, vol. 1, pp. 290–295 (2006). IEEE.

Jaffery, Z.A., Sharma, D. & Ahmad, N. Detection of missing nuts & bolts on rail fishplate. In: 2017 International Conference on Multimedia, Signal Processing and Communication Technologies (IMPACT), pp. 36–40 (2017). IEEE.

Agrawal, S. et al. An arduino based method for detecting cracks and obstacles in railway tracks. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol 4, 945–951 (2018).

Stamp, T. & Stamp, C. William scoresby junior (1789–1857). Arctic 35(4), 550–551 (1982).

Milne, D. et al. Monitoring and repair of isolated trackbed defects on a ballasted railway. Transportation Geotechnics 17, 61–68 (2018).

Edwards, R. et al. Ultrasonic detection of surface-breaking railhead defects. Insight-Non-Destructive Testing and Condition Monitoring 50(7), 369–373 (2008).

Li, Q. & Ren, S. A real-time visual inspection system for discrete surface defects of rail heads. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 61(8), 2189–2199 (2012).

Sorrell, S. Reducing energy demand: A review of issues, challenges and approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 47, 74–82 (2015).

Sharma, S., Cui, Y., He, Q., Mohammadi, R. & Li, Z. Data-driven optimization of railway maintenance for track geometry. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 90, 34–58 (2018).

Alahakoon, S., Sun, Y.Q., Spiryagin, M. & Cole, C. Rail flaw detection technologies for safer, reliable transportation: a review. Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control 140(2) (2018).

Hu, C. & Liu, X. Modeling track geometry degradation using support vector machine technique. In: ASME/IEEE Joint Rail Conference, vol. 49675, pp. 001–01011 (2016). American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Gibert, X., Patel, V. M. & Chellappa, R. Deep multitask learning for railway track inspection. IEEE transactions on intelligent transportation systems 18(1), 153–164 (2016).

Lee, E., Rustam, F., Aljedaani, W., Ishaq, A., Rupapara, V. & Ashraf, I. Predicting pulsars from imbalanced dataset with hybrid resampling approach. Advances in Astronomy 2021 (2021).

Zhong, H., Liu, L., Wang, J., Fu, Q. & Yi, B. A real-time railway fastener inspection method using the lightweight depth estimation network. Measurement 189, 110613 (2022).

Mandriota, C., Nitti, M., Ancona, N., Stella, E. & Distante, A. Filter-based feature selection for rail defect detection. Machine Vision and Applications 15(4), 179–185 (2004).

Manoharan, P., Walia, R., Iwendi, C., Ahanger, T. A., Suganthi, S., Kamruzzaman, M., Bourouis, S., Alhakami, W. & Hamdi, M. Svm-based generative adverserial networks for federated learning and edge computing attack model and outpoising. Expert Systems, 13072 (2022).

Singh, M., Singh, S., Jaiswal, J. & Hempshall, J. Autonomous rail track inspection using vision based system. In: 2006 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Homeland Security and Personal Safety, pp. 56–59 (2006). IEEE.

Li, D. et al. Automatic defect detection of metro tunnel surfaces using a vision-based inspection system. Advanced Engineering Informatics 47, 101206 (2021).

Chandran, P., Asber, J., Thiery, F., Odelius, J. & Rantatalo, M. An investigation of railway fastener detection using image processing and augmented deep learning. Sustainability 13(21), 12051 (2021).

Chandran, P. et al. Supervised machine learning approach for detecting missing clamps in rail fastening system from differential eddy current measurements. Applied Sciences 11(9), 4018 (2021).

Li, D., Wang, Y., Yan, W.-J. & Ren, W.-X. Acoustic emission wave classification for rail crack monitoring based on synchrosqueezed wavelet transform and multi-branch convolutional neural network. Structural Health Monitoring 20(4), 1563–1582 (2021).

Zhan, Y., Dai, X., Yang, E. & Wang, K. C. Convolutional neural network for detecting railway fastener defects using a developed 3d laser system. International Journal of Rail Transportation 9(5), 424–444 (2021).

Yao, D., Sun, Q., Yang, J., Liu, H. & Zhang, J. Railway fastener fault diagnosis based on generative adversarial network and residual network model. Shock and Vibration 2020 (2020).

Wei, X. et al. Railway track fastener defect detection based on image processing and deep learning techniques: A comparative study. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 80, 66–81 (2019).

Cui, H., Li, J., Hu, Q. & Mao, Q. Real-time inspection system for ballast railway fasteners based on point cloud deep learning. IEEE Access 8, 61604–61614 (2019).

Ferreño, D. et al. Prediction of mechanical properties of rail pads under in-service conditions through machine learning algorithms. Advances in Engineering Software 151, 102927 (2021).

Namdeo, R. B. & Janardan, G. V. Thyroid disorder diagnosis by optimal convolutional neuron based cnn architecture. Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 34(5), 871–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/0952813X.2021.1938694 (2022).

Siddiqui, H. U. R. et al. Iot based railway track faults detection and localization using acoustic analysis. IEEE Access 10, 106520–106533 (2022).

Schulte-Werning, B., Thompson, D., Gautier, P.-E., Hanson, C., Hemsworth, B., Nelson, J., Maeda, T. & Vos, P. Noise and vibration mitigation for rail transportation systems. Notes on numerical (2008).

Shabana, A.A. & Ling, H. Characterization and quantification of railroad spiral-joint discontinuities. Mechanics Based Design of Structures and Machines, 1–26 (2020).

Wybo, J.-L. Track circuit reliability assessment for preventing railway accidents. Safety science 110, 268–275 (2018).

Liu, P., Yang, L., Gao, Z., Li, S. & Gao, Y. Fault tree analysis combined with quantitative analysis for high-speed railway accidents. Safety science 79, 344–357 (2015).

Lidy, T. & Schindler, A. Cqt-based convolutional neural networks for audio scene classification. In: DCASE, pp. 60–64 (2016).

Shi, S., Xi, S. & Tsai, S.-B. Research on autoarrangement system of accompaniment chords based on hidden markov model with machine learning. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021 (2021).

Liu, M.-Y. & Tuzel, O. Coupled generative adversarial networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 29 (2016).

Li, M., Chen, W. & Zhang, T. Automatic epileptic eeg detection using dt-cwt-based non-linear features. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 34, 114–125 (2017).

Zainuddin, N. & Selamat, A. Sentiment analysis using support vector machine. In: 2014 International Conference on Computer, Communications, and Control Technology (I4CT), pp. 333–337 (2014). IEEE.

Zheng, W. & Ye, Q. Sentiment classification of chinese traveler reviews by support vector machine algorithm. In: 2009 Third International Symposium on Intelligent Information Technology Application, vol. 3, pp. 335–338 (2009). IEEE.

Svetnik, V. et al. Random forest: a classification and regression tool for compound classification and qsar modeling. Journal of chemical information and computer sciences 43(6), 1947–1958 (2003).

Biau, G. & Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. Test 25(2), 197–227 (2016).

Benediktsson, J. A. & Swain, P. H. Consensus theoretic classification methods. IEEE transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 22(4), 688–704 (1992).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A decision-theoretic generalization of on-line learning and an application to boosting. Journal of computer and system sciences 55(1), 119–139 (1997).

Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Machine learning 24(2), 123–140 (1996).

Guzman, E. & Maalej, W. How do users like this feature? a fine grained sentiment analysis of app reviews. In: 2014 IEEE 22nd International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), pp. 153–162 (2014). Ieee.

Bijalwan, V., Kumar, V., Kumari, P. & Pascual, J. Knn based machine learning approach for text and document mining. International Journal of Database Theory and Application 7(1), 61–70 (2014).

Zhou, Y., Cheng, G., Jiang, S. & Dai, M. Building an efficient intrusion detection system based on feature selection and ensemble classifier. Computer networks 174, 107247 (2020).

Zhou, Y., Cheng, G., Jiang, S. & Dai, M. Building an efficient intrusion detection system based on feature selection and ensemble classifier. Computer networks 174, 107247 (2020).

Shafique, R. et al. A novel approach to railway track faults detection using acoustic analysis. Sensors 21(18), 6221 (2021).

Guo, G., Cui, X. & Du, B. Random-forest machine learning approach for high-speed railway track slab deformation identification using track-side vibration monitoring. Applied Sciences 11(11), 4756 (2021).

Pascanu, R., Gulcehre, C., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. How to construct deep recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6026 (2013).

Hadhood, H. Stock trend prediction using deep learning models lstm and gru with non-linear regression. Master’s thesis, Itä-Suomen yliopisto (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Fault detection and diagnosis of railway point machines by sound analysis. Sensors 16(4), 549 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1A6A1A03039493).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS conceived the idea, performed data curation and wrote the original manuscript. KK performed formal analysis, dealt with software and wrote the original manuscript. VC designed methodology, and performed formal analysis and data curation. GSC performed investigation and visualization, and acquired funding. IA supervised the work, performed validation and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shafique, R., Kanwal, K., Chunduri, V. et al. Improved railway track faults detection using Mel-frequency cepstral coefficient and constant-Q transform features. Sci Rep 15, 30914 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14763-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14763-w