Abstract

Guben Xiezhuo decoction (GBXZD), a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), shows promise in treating chronic kidney disease (CKD) by reducing renal fibrosis (RF). This study seeks to uncover the exact mechanism behind GBXZD’s therapeutic effects. This study identified 14 active components and 18 specific metabolites in the serum of GBXZD-treated rats via mass spectrometry. Potential target proteins were predicted using PubChem, TCMSP, and SwissTargetPrediction databases and refined through OMIM and Genecards databases. A total of 276 proteins were filtered from these potential target proteins to develop a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network to explore the interactions between GBXZD and RF target proteins, revealing significant correlations for proteins such as SRC, EGFR, and MAPK3. Subsequently, the active components and specific metabolites were employed for molecule docking simulation to assess their interactions with EGFR protein. The effects and mechanisms of GBXZD on RF were validated in a unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) rat model by assessing changes in RF-related protein expressions identified from the PPI network. GBXZD showed a reduction in the phosphorylation expression of SRC, EGFR, ERK1, JNK, and STAT3. In vitro, LPS stimulated HK 2 cells treated with the identified GBXZD bioactive components trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid and Cuminaldehyde exhibited significantly enhanced viability and reduced fibrotic marker expression and p-EGFR levels. KEGG pathway analysis suggested that GBXZD’s anti-fibrotic effects might be mediated by inhibiting the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and MAPK signaling pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) ranks among the top ten non-communicable diseases causing long-term illness and disability globally, with an incidence rate of approximately 9.1%1, which is rising annually, placing significant economic pressure on society and healthcare systems2. A common pathological feature of advanced CKD is renal fibrosis (RF), which significantly correlates with end-stage renal disease and increased mortality3. Thus, delaying the progression of RF is critical for effective CKD management. Current conventional medical treatments for RF in CKD patients mainly involve non-specific drugs such as hormones and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonists, which often have significant side effects and limited long-term efficacy4,5. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has unique advantages in treating CKD6, demonstrating efficacy in protecting against RF through various pathways, including anti-inflammatory actions7, reduction of oxidative stress8, and decreased extracellular matrix accumulation9.

TCM physician Zhai Weikai (Jiangsu Province, China) derived GBXZD, a traditional Chinese herbal formula, by modifying the traditional prescription “BuZhongYiQi decoction”. GBXZD is composed of 6 traditional Chinese herbs, including Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge (HuangQi), Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. (Dangshen), Centella asiatica (L.) Urb. (Jixuecao), Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen), Cuscuta chinensis Lam. (Tusizi) and Rheum palmatum L. (Dahuang), which were proven to have significant protective effects on renal disease10,11,12,13,14,15. GBXZD has been clinically used for many years and small-scale clinical trials have confirmed that it can markedly improve glomerular filtration rate, increase patients’ appetite, and reduce symptoms of nausea and vomiting16. Our previous research that GBXZD can inhibit macrophage M1 polarization, reduce inflammatory cytokines secretion, and inhibit the renal interstitial fibrosis progression17. However, as a TCM compound, GBXZD has a complex composition and multiple targets of action. Currently, the key active compounds of GBXZD have not been identified, and the elucidated pathways are limited, indicating that the existing literature is not comprehensive. Therefore, further research is required to elucidate how GBXZD alleviates renal inflammation and fibrosis.

Network pharmacology, based on the theory of systems biology, constructs complex interaction networks of biological functions, target molecules, and bioactive compounds18. This study employed network analysis to comprehensively elucidate the interactions and effects of GBXZD’s components on diverse intracellular pathways associated with renal inflammation and fibrosis, thereby systematically clarifying the intervention mechanisms of TCM19. Furthermore, serum mass spectrometry analysis was also carried out to identify core molecules of GBXZD. Moreover, the potential target genes and GBXZD’s signaling pathways in RF were also assessed via network pharmacology. In addition, the significant role of GBXZD in mitigating RF in rats was confirmed via in vivo analyses.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhangjiagang Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital (Ethics Permit Number: AEWC-20220216-1). All procedures conformed to the ARRIVE guidelines and relevant national regulations.

Guben Xiezhuo decoction preparation

The 6 herbs used in Guben Xiezhuo Decoction were acquired from the TCM dispensary of Zhangjiagang Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital. These herbs included Cuscuta chinensis Lam., Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge., Centella asiatica (L.) Urb., Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bunge, and Rheum palmatum L. For decoction preparation, the herbs were ground into a powder and sieved through a 200-mesh sieve, weighed, and then mixed in a ratio of 10:5:3:4:10:2. The herbal mixture was then soaked for 30 min in distilled water (1000 mL), and boiled for over 1 h to yield approximately 500 mL of liquid medicine.

Preparation of medicated serum containing GBXZD

For serum metabolite mass spectrometry analysis, the drug-containing serum was prepared. Briefly, untreated Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to adaptive feeding for 1 week prior to GBXZD (2.125 g/mL, 1 mL/100 g) or distilled water (1 mL/100 g) administration by gavage, twice daily for 1 week. Blood was collected through the tail vein, and then these rats were euthanized by vertebral detachment. The blank serum was acquired from the untreated rats. The GBXZD-containing serum and the control serum were obtained 2 h after the final administration. The blood samples were placed in non-heparinized tubes at 4 °C for 2 h and then centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C and 3500 rpm to separate the serum.

HPLC-MS

Serum samples from the GBXZD and blank groups, as well as the GBXZD’s components, were subjected to mass spectrometry analysis. Briefly, serum samples (50 µL) were treated with methanol (200 µL), vortexed for 10 min, and centrifuged for 12 min (4 °C, 12,000 rpm) to harvest the supernatant, which was filtered through a microporous membrane for subsequent assessments. Furthermore, the herbal decoction (200 µL) was processed by mixing with 80% methanol (1000 µL), vortexing for 10 min, and centrifuging for 12 min (4 °C, 12,000 rpm) to harvest the supernatant, which was filtered and analyzed. An Ultimate 3000 RS chromatograph and a Q Exactive high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) were used for data collection. Moreover, the chromatography column AQ-C18 (Welch, Shanghai, China) with 35 °C temperature was employed for both negative and positive ionization in the MS analysis. To compare the high-resolution mass and liquid data, the CD software was used by Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA, Version: 3.3, https://www.thermofisher.com) before the mzCloud database was searched for data acquisition and comparison.

Network pharmacology analysis of GBXZD

Screening of GBXZD bioactive components and targets

The bioactive components and potential targets were identified in several steps: (1) Differential Metabolites Identification: the determination of differential metabolites in the serum of GBXZD-treated and control groups by HPLC-MS. (2) Matching Metabolites: the differential serum metabolites were matched with the components of the GBXZD decoction. Metabolites found in both the serum and decoction were considered bioactive components of GBXZD, while those that did not match were considered GBXZD-related metabolites. (3) Protein Targets Prediction: The differential serum metabolites were used to predict protein targets through the following databases: Swiss Target Prediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/)20, TCMSP database (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php)21, and PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)22. With the help of these databases, the bioactive components of GBXZD were mapped to their potential protein targets to better understand how GBXZD alleviates RF.

Screening targets related to RF

Information on various genes associated with RF was procured from the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (https://www.omim.org) and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org) databases23,24, which is a source of comprehensive data on human genes and genetic disorders. The search strategy included keywords such as: “glomerulosclerosis,” “renal fibrosis,” and “renal failure.” The acquired data were exported online for further assessment.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction and key targets screening

To elucidate the interactions of GBXZD-related targets with RF targets, a gene overlap analysis was conducted between the two concerned targets. For the construction of the PPI network, the STRING database (https://string-db.org/)25 was employed. The PPI network was imported into Cytoscape software (Version: 3.7.2, https://cytoscape.org) using CytoNCA to assess the topological structure of the cross-network. For the PPI analysis model, the parameters were “multiple proteins,” and “Homo sapiens” species. Key targets were filtered based on a threshold of more than twice the median degree value. The objective of this analysis was to identify the key targets that are crucially associated with the interaction network between GBXZD-related targets and RF targets, providing potential mechanisms underlying GBXZD’s therapeutic effects on RF.

Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses

To assess the target genes linked with pathway enrichment and functional annotation, KEGG analysis and GO annotation were carried out using the Metascape database (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html)26,27. GO annotation provides insights into the cellular components (CC), biological processes (BP), and molecular functions (MF) linked with the target genes. Furthermore, it elucidates the various biological functions of the target genes. KEGG analysis identifies the pathways in which the target genes are significantly enriched and provides data on the involved signaling pathways and molecular processes in the BP under investigation. Following the KEGG analysis, a network model called “GBXZD Bioactive Components - Targets - KEGG Pathways” was constructed In this model, nodes represent serum metabolites, targets, and KEGG pathways, while edges represent the relationships between these nodes, illustrating their functional interactions.

Molecular docking simulation

Active components and specific metabolites were used for molecule docking simulation to assess their interactions with EGFR protein. The 3D structure of EGFR protein was downloaded from Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (https://www.rcsb.org/)28, while the 2D chemical structures was acquired from PubChem database. The molecular docking simulation was carried out by AutoDockTools software (Version: 1.5.7, http://autodock.scripps.edu/). The binding energy threshold of the simulation results were filtered to be ≤ -5.0 (kcal/mol), which were then visualized by PyMOl software(Version: 3.0.0, https://pymol.org).

Unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) animal model and treatment

Male SD rats (n = 25) were acquired from Soochow University Zhaoyan New Drug Research Centre Co., Ltd that met specific pathogen-free (SPF) criteria and weighed between 250 and 300 g. The rats were housed in a 12-h dark/light rhythm, 20–22 °C temperature, and 40–70% humidity. After 1 week of acclimatization, the animals were randomly categorized into 4 groups (UUO + GBXZD-L, sham-operated, UUO + GBXZD-H, and UUO). The method of Chevalier et al. was followed to establish the UUO model29. Briefly, 2% sodium pentobarbital (0.2 mL/100 g body weight) was administered intraperitoneally in rats for anesthetized. The rats were then placed in a supine orientation, the skin was disinfected, a longitudinal incision was made in proximity to the left kidney, and the left ureter was dissected bluntly. In the sham-operated control group, the ureter was similarly dissected bluntly, followed by layer-by-layer suturing of the muscle and skin. Furthermore, the upper and lower third of the ureter was ligated with 3.0 sutures, and the middle part was incised in the experimental group. The wounds were closed with layered sutures, followed by penicillin sodium administration in the muscles to prevent infection. From the 2nd day after the operation, gastric gavage was initiated and continued for 14 days. All rats were administered 1 mL/100 g body weight medication via gastric gavage, with the model and control groups receiving physiological saline. The final high- and low-dose concentrations of GBXZD were 2.1 and 1.1 g/mL, respectively. Following two weeks of gastric gavage, the rats were weighed, anesthetized with 2% sodium pentobarbital based on their body weight, and subsequent laparotomy. Moreover, the left kidneys were dissected and weighed, one of which was washed gently with PBS and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, while the other was stored in liquid nitrogen. The blood samples were sampled from the rat’s abdominal aorta before sodium pentobarbital (120 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection, 1 ml/100 g of body weight) was administered for euthanasia.

Measurement of renal morphology and function

After 14 days of gastric gavage, the left kidneys of the rats were harvested to assess their size and morphology within each experimental group. Furthermore, whole blood was sampled from the abdominal aorta, allowed to stand for 2 h at ambient temperature, and then centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C and 3000 rpm. The supernatant’s serum creatinine (Scr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were assessed via an automatic biochemical analyzer (Chemray 240, Shenzhen Leadman Biochemistry).

Renal tissue pathology evaluation

The kidney tissues were sectioned horizontally, half of which was fixed for 48 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated via an automated dehydration system, and then submerged in paraffin. Masson’s trichrome and Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining were performed to evaluate tissue’s renal injury and fibrin deposition.

Cell culture

HK-2 cells (human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells) were obtained from Procell Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) and cultured in Procell’s proprietary HK-2 medium (CM-0109, Procell Biotechnology, Wuhan, China) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Culture medium was refreshed every 48 h, and cells were routinely passaged twice per week; experiments were conducted using cells between passages 5 and 10. To establish an in vitro fibrosis model, HK-2 cells were seeded into multiwell plates and permitted to adhere overnight, after which they were exposed to 1 µg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS; L4391, SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 h. Following this induction period, treatment cohorts received 11Ketodihydrotestosterone (HY-135794, MedChemExpress, USA), Cuminaldehyde (HYY0790, MedChemExpress, USA), or trans-3Indoleacrylic acid (HYW015273A, MedChemExpress, USA) at specified concentrations for an additional 24 h in the continued presence of LPS. A sham control group was maintained under identical culture conditions without LPS or compound treatment.

Cell viability tests

HK-2 cells were seeded into 96well plates at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well in 200 µL Procell HK-2 medium and allowed to adhere for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Thereafter, cells were treated with graded concentrations of 11Ketodihydrotestosterone (0, 1, 10, 100 nM, 1 µM), Cuminaldehyde (0, 1.28, 12.8, 128, 1280 µM), or trans-3Indoleacrylic acid (0, 5, 50, 500 µM) for 24 h. At the conclusion of the treatment period, 20 µL of CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h under identical conditions. Absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a BioTek Cytation 5 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability was calculated as the percentage of absorbance relative to vehicletreated controls.

To assess the protective effects of these compounds in an LPSinduced fibrosis model, HK-2 cells were again seeded at 1 × 103 cells per well in the presence of 1 µg/mL LPS and incubated for 24 h. Following, cells were treated with graded concentrations of 11Ketodihydrotestosterone, Cuminaldehyde, or trans-3Indoleacrylic acid for 24 h. CCK-8 assays were then performed as described above, and viability was expressed as a percentage relative to LPSonly controls, thereby quantifying each compound’s ability to ameliorate LPSinduced cytotoxicity.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, renal tissue sections were deparaffinized, and their antigens were retrieved. To inhibit the activity of endogenous peroxidase, the samples were reacted with a 3% solution of hydrogen peroxide at ambient temperature for 25 min, followed by PBS washing, blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at ambient temperature for 30 min, and overnight treatment with the primary antibodies at 4 °C. The sections were rinsed again with PBS thrice for five min each time before 50 min of secondary antibody incubation. The employed antibodies were all from Servicebio and included TNF-α (GB11188, 1:500), IL-1β (GB11113, 1:500), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (GB111364, 1:2000), IL-6 (GB11117, 1:500), collagen 1 (COL 1) (GB11022, 1:1000), fibronectin (FN) (GB13091, 1:200), and secondary antibody (GB23204, 1:500). The sections were then stained with hematoxylin and diaminobenzidine, dehydrated, and coverslipped for visualization under a microscope.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Based on the PPI network, the top 8 core genes ranked by degree were selected as potential target genes for validation and qRT-PCR screening. For primers designing online Primer-BLAST software from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was employed (Table 1). Shanghai Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. synthesized the primers. Whole RNA was isolated from the rat’s kidney tissue via the silica column purification method. For cDNA preparation, a reverse transcription kit was employed. SYBR Premix Ex Taq II fluorescence quantitative PCR kit utilized for cDNA amplification. Each sample was assessed thrice. The 2−ΔΔCT method was employed for quantitative analysis, with β-actin as the endogenous reference gene.

Western blot analysis

Protein lysates from both HK-2 cells and rat kidney tissues were prepared in parallel. Cells were washed twice with icecold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (P0013C, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail (P1045, Beyotime). Kidney tissues were homogenized in the same buffer. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and protein concentrations determined using the Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Subsequently, on the precast gel (P0508M, Beyotime), protein samples (20 µg) and 5 µL of marker (RM19001, ABclonal, Wuhan, China; 26619, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were loaded for electrophoresis separation, then transferred onto PVDF membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), occluded with blocking buffer (P0252, Beyotime) and then treated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The antibodies employed included β-actin (cat # 4970), Src (2109), Phospho-Src Family (Tyr416) Antibody (2101), EGF Receptor (4267), Phospho-EGF Receptor (Tyr845) (2231), ERK1/2 (9102), Phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (4370), SAPK/JNK (9252), Phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (4668), Stat3 (30835), Phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) (19145). All the antibodies were diluted at 1:1000 and were from CST. CWBiotech’s BP-G0004 Tween-20 with Tris-buffered saline was then used to wash the membranes and incubate them for 1 h at ambient temperature with HRP-linked secondary antibodies (1:1000, #7074, CST). The protein bands were visualized via a chemiluminescent HRP substrate (WBKLS0500, Millipore, Massachusetts, USA) and their signal intensities were quantified via ImageJ software (Version: 1.53a, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Statistical measurements

GraphPad Prism (Version: 8.0, https://www.graphpad.com) was employed for statistical measurements. For comparing more than three groups, the one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests was carried out.

Results

Identification of bioactive components in GBXZD by HPLC-MS

GBXZD and blank serum samples as well as the components of herbal decoction were analyzed with HPLC-MS in both negative and positive ion modes (Fig. 1a, b, c). For identification, standard materials, and chemical information were compared in the mzCloud spectral library, using a > 60 mzCloud best match score as the threshold. The identified compounds were further validated by cross-referencing the PubChem and TCMSP datasets. By comparing differences in mass spectrometry results among samples, the differential metabolites were determined. The analysis revealed 14 main bioactive components of GBXZD (Fig. 1d), including trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid, Salicylic acid, L-Phenylalanine, DL-Homoserine, DL-Glutamine, D-(+)-Pyroglutamic Acid, D-(+)-Pipecolinic acid, Cytosine, Betaine, Pentalenic acid, 6-Methylindole, 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde, (±)12(13)-DiHOME, and Hexadecanedioic acid (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, 40 specific metabolites were identified (Fig. 1d), including 18 from the PubChem database, such as Linoleic acid, L-(+)-Citrulline, Cuminaldehyde, 8Z,11Z,14Z-Eicosatrienoic acid, and 11(Z),14(Z)-Eicosadienoic acid. (Supplementary Table S2). (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 1 Mass spectrometry results data.xlsx)

HPLC-MS was used to determine the serum samples of the GBXZD and blank groups, as well as GBXZD decoction in positive and negative ion modes. (a) HPLC-MS results of GBXZ-medicated serum, (b) Blank serum, and (c) GBXZ decoction. (d) Venn diagram of components in GBXZ medicated serum, Blank serum, and GBXZD decoction. The orange circle represents the bioactive components of GBXZD, while the purple circle represents the metabolites of GBXZD.

Target selection and PPI network analysis

Based on the HPLC-MS identification of GBXZD blood components and specific metabolites, a query was conducted in the TCMSP and Swiss Target Prediction databases, which revealed 310 potential targets for GBXZD. Moreover, 7234 potential RF targets were screened from the Genecards and OMIM databases. In addition, 276 intersecting targets were observed between the potential targets of GBXZD and CKD nephrofibrosis (Fig. 2a). A PPI network was established based on these targets (Fig. 2b), which revealed that proteins such as SRC, EGFR, TNF-α, IL6, PTGS2, ESR1, MAPK3, and EP300 had high rankings, suggesting that they may be potential GBXZD targets in treating RF. (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 2 Network pharmacology analysis data.xlsx)

Network pharmacology analysis. (a) Cross target between GBXZD and RF. (b) A PPI network with common targets of GBXZD and RF. (c) According to the GO enrichment analysis of GBXZD RF co-targets, these are the top 10 indicators of cellular components (CC), biological processes (BP), and molecular functions (MF). (d) The KEGG enrichment analysis of common targets in GBXZD RF identified the top 10 signaling pathways associated with RF. (e) GBXZD bioactive components-target-pathway diagram.

GO analysis, KEGG analysis, and the GBXZD bioactive components-target-pathway diagram

To further explore the mechanism of GBXZD systematically, the 276 overlapping targets were uploaded to the Metascape database. The top 10 GO terms (Fig. 2c) primarily associated with BP were enriched in hormone response, cellular response to nitrogen compounds, circulatory system processes, and regulation of inflammatory responses. The top 10 GO terms associated with CC were mainly related to membrane raft, receptor complex, synaptic membrane, etc. Whereas the top 10 GO terms related to MF were primarily associated with oxidoreductase activity, nuclear receptor activity, amide binding, etc. The KEGG enrichment analysis of common targets in GBXZD and RF revealed 208 signaling pathways, including PI3K-Akt, HIF-1, Estrogen, TNF, Ras, Rap1, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance, FoxO, MAPK, ErbB signaling pathways (Fig. 2d), which may be closely related to RF. Specifically, the BestLogPInGroup metric from the KEGG enrichment analysis was applied to rank all 208 pathways by statistical significance. Based on prior research findings and a PubMed search evaluating the correlation between these pathways and renal fibrosis, the top 10 were subsequently selected. The data of KEGG analysis were utilized to construct the ‘GBXZD bioactive components-target-KEGG pathway’ network (Fig. 2e). Network topology analysis revealed that the GBXZD metabolites associated with CKD treatment targets and pathways included (±)12(13)-DiHOME, 11(Z),14(Z)-Eicosadienoic acid, 11-keto Testosterone, 8Z,11Z,14Z-Eicosatrienoic acid, Linoleic acid, Salicylic acid, 5-[(10Z)-14-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl)tetradec-10-en-1-yl]benzene-1,3-diol, etc.

Molecular Docking results of EGFR protein

The serum mass spectrometry results was performed to identify the active components and specific metabolites of GBXZD. EGFR, a cell surface membrane protein capable of directly interacting with serum-derived compounds, emerged as a central node in the PPI network and was recognized as a hub in multiple renal fibrosis-related pathways, and was therefore chosen as a potential docking target. Furthermore, Trans-3 Indomethacrylic acid was identified as the active components, while Cuminaldehyde and 11-keto Testosterone as the specific metabolites with significant binding potential to the EGFR protein (Fig. 3a–b), suggesting EGFR protein as a core target of GBXZD. (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 3 Molecular docking analysis.xlsx)

Improvement of renal morphology and function in UUO rats by GBXZD

The pharmacological effects of GBXZD were confirmed in a UUO rat model to substantiate the findings of network pharmacology. After 14 days of oral administration, sham operation rats had normal size and morphology of the kidneys with a dark red appearance. Whereas, the left kidney of UUO rats indicated significant enlargement with an irregular surface and turbid fluid. The weights of the body and the rat’s left kidney were also assessed during sampling. The ratio of obstructed kidney to body weight was highest in UUO rats, and greater in GBXZD rats than in sham operated rats. However, it was reduced than the UUO group (Fig. 4c). Moreover, the kidney function analyses indicated that Scr and BUN levels were notably enhanced in the UUO rats than in the sham operation rats, whereas they were reduced in the GBXZD rats compared to the UUO rats (Fig. 4d–e). (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 4 GBXZD alleviated renal pathological damage.xlsx)

GBXZD alleviated renal pathological damage in UUO rats. (a) HE staining showed that GBXZD decreased inflammatory cell infiltration and ameliorated tubular injury relative to the UUO model rats. (b) Masson staining showed that GBXZD significantly reduced the deposition of collagen fibrillar protein in the kidneys of UUO rats. (c) GBXZD reduced the ratio of obstructed kidney to body weight in UUO rats. (d–E) GBXZD reduced blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels in UUO rats. (f) Comparison of collagen area ratio based on Masson staining. *p < 0.05 vs. Model group, **p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ***p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ns for p > 0.05 vs. Model group.

Reduction of renal inflammatory injury and fibrosis by GBXZD in UUO rats

The HE pathological examination of the kidneys revealed (Fig. 4a) that the kidney tissue structure of the control rats was unaltered with no discernible abnormalities or renal interstitium infiltration of inflammatory cells. However, the UUO rats indicated fibrosis, increased fibroblast proliferation, lymphocyte infiltration, enhanced irregularly arranged tubular dilation, extensive degeneration of tubular epithelial cells, cell swelling, as well as sparse and pale cytoplasmic staining. Whereas the GBXZD rats had decreased inflammatory cell infiltration and ameliorated tubular injury relative to the model group. Masson staining indicated markedly increased collagen fiber proliferation in the renal interstitium of the UUO group than in the sham operation group. Following treatment with GBXZD, a marked reduction in the collagen protein area was observed in comparison to the UUO group (Fig. 4b). The tubular injury scores and collagen-positive areas proportion analyses revealed statistically significant variances (Fig. 4f).

The immunohistochemical findings revealed a significant upregulation of IL-6, α-SMA, COL1, IL-1β, FN, and TNF-α expression in the kidneys of the UUO group compared to the sham operation group (Fig. 5a–f). This was evidenced by larger and darker brown positive areas, suggestive of inflammatory factors aggregation and extracellular matrix accumulation. The GBXZD-L and GBXZD-H treatments decreased the release of inflammatory factors and extracellular matrix deposition compared to the UUO group, as supported by semi-quantitative analysis demonstrating statistically significant differences. (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 5 Immunohistochemical analysis.xlsx)

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that GBXZD attenuated the expression of inflammatory factors and extracellular matrix components in UUO rats renal tissues. (a–c) Immunohistochemical results of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in rat kidneys. (g–i) Semi-quantitative analysis of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. (d–f) Immunohistochemical results of COL-1, FN, and α-SMA in rat kidneys. (j–l) Semi-quantitative analysis of COL-1, FN, and α-SMA. *p < 0.05 vs. Model group, **p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ***p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ns for p > 0.05 vs. Model group.

GBXZD may exert anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects via the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and MAPK signaling pathways

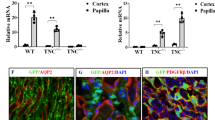

To validate the potential hub genes in GBXZD predicted by network pharmacology, RT-qPCR was carried out to analyze the transcriptional alterations of the top 8 potential PPI network hub genes including SRC, EGFR, TNF-α, IL6, PTGS2, ESR1, MAPK3, and EP300 (Fig. 6a–h). Statistical analysis showed that in comparison to the sham operation rats, the transcriptional expression of SRC, EGFR, TNF-α, IL6, PTGS2, MAPK3, and EP300 was upregulated in the UUO rats, whereas after the GBXZD treatment, the transcriptional expression of SRC, EGFR, TNF-α, IL6, and MAPK3 was significantly reduced. (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 6 qRT-PCR.xlsx)

qRT PCR results of the top 8 potential hub targets in the PPI network ranking. (a) qRT PCR results of EGFR, (b) SRC, (c) MAPK3, (d) TNF-α, (e) IL-6, (f) PTGS2, (g) EP300, and (h) ESR1 genes expression. *p < 0.05 vs. Model group, **p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ***p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ns for p > 0.05 vs. Model group.

Based on previous research and qRT-PCR results, EGFR, SRC, MAPK family members MAPK3 (ERK1) and MAPK8 (JNK), as well as their downstream target STAT3 were selected for Western blotting validation. A significant increase was observed in the expression of phosphorylated EGFR, SRC, ERK1, JNK, and STAT3 in UUO rats’ kidneys compared to the Sham rats, which reduced markedly after GBXZD treatment (Fig. 7a–o). Combined with KEGG analysis results, it was suggested that the signaling pathways of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and MAPK might be associated with GBXZD-induced inhibition of renal inflammation and fibrosis. (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 7 WB.xlsx; WB Supplement Table.pdf)

Western blotting analysis elucidated the mechanism of GBXZD in combating RF. (a–c) The analysis of EGFR and p-EGFR (Tyr845) expression in rat kidney tissue indicated that p-EGFR expression was significantly reduced after GBXZD intervention. (d–f) The analysis of SRC and p-SRC (Tyr416) expression in rat kidney tissue. The p-SRC expression significantly decreased after GBXZD intervention. (g–i) The analysis of ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) expression in rat kidney tissue. The expression of p-ERK was significantly reduced after GBXZD intervention. (j–l) The analysis of SAPK/JNK and p-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) expression in rat kidney tissue. The expression of p-SAPK/JNK was significantly reduced after high-concentration GBXZD intervention. (m–o) The analysis of Stat3 and p-Stat3 (Tyr705) expression in rat kidney tissue. The expression of p-Stat3 was significantly reduced after GBXZD intervention. These samples derive from the same experiment and these blots were processed in parallel. *p < 0.05 vs. Model group, **p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ***p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ns for p > 0.05 vs. Model group

HK-2 cells were treated with graded concentrations of 11-Ketodihydrotestosterone, Cuminaldehyde, or trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid, and viability was assessed by CCK-8. Panels (a–c) show cytotoxicity in unchallenged cells: (a) trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid (0–500 µM) was non-toxic, with 500 µM significantly enhancing viability; (b) Cuminaldehyde (0–1280 µM) exhibited no toxicity; (c) 11-Ketodihydrotestosterone (0–1000 nM) exhibited no toxicity. Panels (d–f) show protective effects in LPS-stimulated cells: (d) 500 µM trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid enhanced viability; (e) Cuminaldehyde at 128 µM and 1280 µM enhanced viability; (f) 11-Ketodihydrotestosterone showed no significant protective effect across 0–1000 nM. *p < 0.05 vs. Model group, **p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ****p < 0.001 vs. Model group, ns for p > 0.05 vs. Model group.

Bioactive components and metabolites of GBXZD protect HK 2 cells from LPS induced cytotoxicity and EGFR mediated fibrotic signaling

Network pharmacology and molecular docking analyses indicated that 11-Ketodihydrotestosterone, Cuminaldehyde, and trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid—identified as potential bioactive components and metabolites of GBXZD—may exert significant pharmacological activity against renal fibrosis; in vitro experiments further validated this hypothesis. In the initial cytotoxicity assessment, HK-2 cells exposed for 24 h to graded concentrations of these three compounds exhibited no appreciable loss of viability across most treatment groups. Notably, treatment with 500 µM trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid induced a modest but statistically significant increase in cell viability compared to untreated controls, suggesting a potential pro-survival effect at this concentration without evidence of overt cytotoxicity (Fig. 8a–c). In the subsequent LPS-induced fibrosis model, treatment with 500 µM trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid or Cuminaldehyde at 128 µM and 1280 µM conferred significant protection against LPS-mediated cytotoxicity, as evidenced by increased cell viability relative to LPS-only controls (Fig. 8d–f). (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 8 CCK8 tests.xlsx)

Based on these results, the most efficacious concentrations (500 µM trans-3Indoleacrylic acid and 1280 µM Cuminaldehyde) were selected for mechanistic interrogation via Western blot analysis. In LPSstimulated HK-2 cells treated with these concentrations, expression of the αSMA was markedly attenuated compared to the model group, while total EGFR protein levels remained unchanged. Importantly, levels of pEGFR were significantly reduced under both treatment conditions, implicating inhibition of EGFR activation as a potential mechanism by which these compounds mitigate LPSinduced fibrogenic responses (Fig. 9a–d). (More details were provided in supplementary material: Fig. 9 HK2 WB.xlsx; HK2 WB Supplement Table.pdf)

Western blot analysis of EGFR activation and fibrotic marker expression in LPS-challenged HK-2 cells treated with 500 µM trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid or 1280 µM Cuminaldehyde. (a) Representative Western blot images showing p-EGFR (Tyr845), EGFR, α-SMA and β-actin expression in HK-2 cells across Sham, LPS, LPS + trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid, and LPS + Cuminaldehyde groups. (b) The analysis of p-EGFR (Tyr845) expression indicated that LPS markedly increased EGFR phosphorylation, whereas treatment with trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid or Cuminaldehyde significantly reduced p-EGFR levels. (d) EGFR expression remained unchanged across all groups. (d) The analysis of α-SMA expression revealed that LPS induced a pronounced upregulation of this fibrotic marker, which was significantly attenuated by both trans-3-Indoleacrylic acid and Cuminaldehyde interventions. *p < 0.05 vs. Model group, ns for p > 0.05 vs. Model group.

Discussion

RF is a predominant pathological characteristic of CKD and a common final pathway in the majority of chronic progressive kidney disorders30. The renal function deterioration resulting from RF ultimately culminates in end-stage renal disease, which necessitates renal replacement therapy, imposing a substantial economic burden and survival challenges on CKD patients31. Therefore, treating RF is crucial for inhibiting CKD progression. RF has a complex etiology involving multiple signaling pathways such as Ras, MAPK, and TNF9,32,33. Despite the research on the development of therapeutic interventions targeting these pathways, efficacious treatment modalities for the clinical management of RF are limited34.

It has been observed that in some regions of Jiangsu Province, clinicians choose GBXZD as a treatment for CKD. Previous research on GBXZD has confirmed its therapeutic effect on RF17; however, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Therefore, this research employed network pharmacology as a bioinformatics tool, as well as mass spectrometry identification and in vivo analyses in rats, to identify drug molecules, targets, and pathways associated with GBXZD’s therapeutic effect on RF.

Here, serum and drug spectral results were compared, which revealed 14 drug components and 18 specific metabolites, including L-Phenylalanine, 5-[(10Z)-14-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl)tetradec-10-en-1-yl]benzene-1,3-diol, 8Z,11Z,14Z-Eicosatrienoic acid, 11-keto Testosterone (CRM), 11(Z),14(Z)-Eicosadienoic acid, among others (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the TCMSP, PubChem, and Swiss Target Prediction databases were utilized for target prediction based on the screened drug components and specific metabolites. Then, the predicted targets were filtered through the Genecard database to obtain 276 potential target genes for GBXZD associated with RF treatment (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, the metabolic and PPI networks were constructed for GBXZD-RF using Cytoscape. Based on degree ranking, potential hub genes were identified for RF, such as IL-6, EGFR, SRC, TNF-α, and MAPK3 (Fig. 2b). In addition, the Metascape database was accessed for GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the relevant target genes, revealing several GO terms of BP were associated with kidney diseases, including hormone responses, regulation of inflammatory responses, regulation of hormone levels, inflammatory responses, and regulation of MAPK cascades (Fig. 2c). These processes may be linked to GBXZD’s ability to inhibit kidney inflammation and fibrosis. The KEGG pathway analysis revealed 208 pathways differentially modulated by GBXZD treatment, including the PI3K-Akt, HIF-1, Estrogen, TNF, Ras, Rap1, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance, FoxO, MAPK, and ErbB signaling pathways (Fig. 2d), all implicated in kidney inflammation and fibrosis development. The results of the molecular docking simulation also indicated potential binding interactions between the EGFR protein and Trans-3 Indomethacrylic acid, Cuminaldehyde, and 11-keto Testosterone from GBXZD (Fig. 3). Overall these data indicated that GBXZD could potentially ameliorate kidney inflammation and hinder fibrosis by modulating the above signaling pathways; however, more studies are needed to validate these findings.

This study utilized the rat UUO model and the pharmacological model of GBXZD. The model group indicated elevated Scr and BUN concentrations compared to the sham-operated group, which was markedly reduced in the GBXZD-treated group (Fig. 4d–e). The HE and Masson staining indicated that the normal group’s kidney tissue structure was preserved without notable abnormalities or inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal interstitium. Whereas, the UUO rats had substantial fibroblast proliferation, renal interstitial fibrosis, irregular tubule arrangement, lymphocyte infiltration, severe tubular dilation, extensive degeneration of tubular epithelial cells, cell swelling, cytoplasmic rarefaction, and shallow staining. The interstitial region of the kidneys demonstrated significant collagen fiber proliferation. Compared to the control rats, GBXZD-treated rats indicated decreased infiltration of inflammatory cells, mitigation of tubular damage, and a notable reduction in collagen protein area (Figs. 4 and 5). Altogether, the data indicated that GBXZD can partially ameliorate the effect on UUO-induced kidney inflammation and interstitial fibrosis.

Based on network pharmacology analysis, the top 8 genes ranked by the degree in the PPI network were selected for qRT-PCR validation. Among the top 8 genes, the SRC, EGFR, TNF-α, IL6, PTGS2, MAPK3, and EP300 expression were greater in the UUO rats than in the sham operation rats, whereas after GBXZD intervention, the expression of TNF-α, SRC, EGFR, IL-6, and MAPK3 reduced significantly (Fig. 6). Based on our previous research finding and qRT-PCR validation that GBXZD can downregulate RAF1/P-ELK1 expression in macrophages, it was inferred that EGFR, SRC, MAPK3, TNF-α, and IL-6 are essentially involved in the signaling pathways through which GBXZD exerts its anti-fibrotic effects on the kidneys. Therefore, western blotting was performed to validate EGFR, SRC, and the MAPK family members MAPK3 (ERK1), MAPK8 (JNK), and the nuclear protein STAT3. The results confirmed that GBXZD substantially downregulated the phosphorylated protein expression of EGFR, SRC, MAPK3, MAPK8, and STAT3 in UUO rats (Fig. 7). In parallel, guided by network pharmacology and molecular docking analyses, we selected putative active components of GBXZD for in vitro validation in an HK-2 cell model. CCK-8 viability assays demonstrated that trans-3Indoleacrylic acid and Cuminaldehyde exhibited no cytotoxicity and significantly enhanced the viability of HK-2 cells stimulated with 1 µg/mL LPS (Fig. 8). Subsequent Western blot analysis of LPSstimulated HK-2 cells treated with these concentrations revealed a marked reduction in p-EGFR and αSMA expression, while total EGFR levels remained unchanged, thereby recapitulating the renoprotective and antifibrotic effects observed in vivo (Fig. 9).Moreover, EGFR, a cell membrane receptor protein, modulates the phosphorylation levels of downstream SRC family proteins35 and downregulates the expression of Raf1 protein by regulating the number of receptors on the cell membrane and its phosphorylation level. This reduces the MAPK family protein’s phosphorylation levels36, thereby affecting the phosphorylation of nuclear proteins including STAT337,38 and ELK139,40, downregulating inflammatory factors including IL-1 β, TNF-α, and IL-641, as well as the expression of fibrillar proteins like α-SMA, COL1, and FN42 (Fig. 10). Based on KEGG analysis, it was hypothesized that GBXZD’s renal protective effects may be attributed to its suppression of the EGFR/SRC/RAF/ERK/ELK and EGFR/SRC/RAF/JNK/ELK signaling pathways within the MAPK pathway, thereby decreasing inflammatory factor release. Moreover, GBXZD may inhibit the EGFR/SRC/STAT3 signaling pathway within the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance pathway, resulting in reduced expression of fibrotic proteins and alleviation of renal interstitial fibrosis.

Overall, GBXZD has the potential to ameliorate UUO-induced RF by inhibiting the MAPK signaling pathway and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance pathway (Fig. 10). This investigation highlighted that GBXZD can suppress inflammatory factors and fibrinogen secretion. However, additional validation through in vivo and in vitro experiments is warranted.

This study has several limitations. First, our network pharmacology and molecular docking approaches are purely predictive, and additional experimental validation across a broader range of GBXZD targets is needed. Second, although we assessed cell viability and selected three compounds for in vitro testing, we lack comprehensive dose–response and toxicity data for individual GBXZD components, as well as detailed pharmacokinetic profiling. Finally, the long term effects of GBXZD on renal cell phenotypes and in vivo functional outcomes remain to be determined.

Conclusion

In summary, the mass spectrometry analysis in this research identified the pharmacological components and the metabolites of GBXZD. Furthermore, the network pharmacology prediction and in vivo assessment validated the mechanism by which GBXZD alleviates RF in CKD. Moreover, it was observed that GBXZD can attenuate renal inflammatory cytokine stimulation and RF progression caused by UUO in rats by inhibiting the EGFR/SRC/RAF/ERK/ELK and EGFR/SRC/RAF/JNK/ELK signaling pathways within the MAPK pathway, as well as the EGFR/SRC/STAT3 signaling pathway within the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance pathway. In parallel, in vitro experiments confirmed that the GBXZD bioactive component and metabolite, trans-3Indoleacrylic acid and Cuminaldehyde, alleviated LPSinduced injury in HK-2 cells while concurrently reducing pEGFR levels and fibrotic marker expression. These findings elucidate GBXZD’s potential mechanism of action. To further comprehensively evaluate its therapeutic value, additional studies—including larger-scale animal experiments, comprehensive toxicity evaluations, and well-designed clinical trials—will be conducted to validate the efficacy and safety of GBXZD. Such efforts will help clarify its clinical application value and further consolidate its role as a candidate for treating renal fibrosis.

Data availability

In this study, the dataset of potential drug targets was derived from the TCMSP (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/index.php) and SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction) databases, using GBXZD serum-specific metabolites (Supplementary Tables S1, S2) filtered through the PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database as keywords. After screening, the targets were standardized using the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org) to obtain their official names. Renal fibrosis-associated genes were predicted through the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (https://www.omim.org) and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org) databases, using the keywords “glomerulosclerosis,” “renal fibrosis,” and “renal failure.” The 3D structure of the EGFR protein used in molecular docking was sourced from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (https://www.rcsb.org/) with the protein ID 1m17. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. Correspondence and requests for data should be addressed to Shutao Chen (chenstdoc@gmail.com) or Minggang Wei (weiminggang@suda.edu.cn).

References

GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and National burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 395, 709–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30045-3 (2020).

Bello, A. K. et al. Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA 317, 1864–1881. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.4046 (2017).

Humphreys, B. D. Mechanisms of renal fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 80, 309–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034227 (2018).

Klinkhammer, B. M., Goldschmeding, R., Floege, J. & Boor, P. Treatment of renal fibrosis-turning challenges into opportunities. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 24, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2016.11.002 (2017).

MacKinnon, M. et al. Combination therapy with an angiotensin receptor blocker and an ACE inhibitor in proteinuric renal disease: A systematic review of the efficacy and safety data. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 48, 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.04.077 (2006).

Xi, Y. et al. Clinical trial for conventional medicine integrated with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of patients with chronic kidney disease. Medicine 99, e20234. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000020234 (2020).

Wang, M., Wang, L., Zhou, L., Xu, Y. & Wang, C. Shen-Shuai-II-Recipe inhibits tubular inflammation by PPARα-mediated fatty acid oxidation to attenuate fibroblast activation in fibrotic kidneys. Phytomedicine 126, 155450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155450 (2024).

Mao, Z. M. et al. Huangkui capsule attenuates renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy rats through regulating oxidative stress and p38MAPK/Akt pathways, compared to α-lipoic acid. J. Ethnopharmacol. 173, 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.036 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Patchouli alcohol against renal fibrosis of spontaneously hypertensive rats via Ras/Raf-1/ERK1/2 signalling pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 75, 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpp/rgad032 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Advances in the Pharmacological study of Chinese herbal medicine to alleviate diabetic nephropathy by improving mitochondrial oxidative stress. Biomed. Pharmacother. 165, 115088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115088 (2023).

Gu, M. et al. Chrysophanol, a main anthraquinone from Rheum palmatum L. (rhubarb), protects against renal fibrosis by suppressing NKD2/NF-κB pathway. Phytomedicine 105, 154381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154381 (2022).

He, J. et al. Kidney targeted delivery of Asiatic acid using a FITC labeled renal tubular-targeting peptide modified PLGA-PEG system. Int. J. Pharm. 584, 119455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119455 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Protective effect of a polysaccharide from stem of Codonopsis pilosula against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Carbohydr. Polym. 90, 1739–1743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.07.062 (2012).

Shabab, S., Gholamnezhad, Z. & Mahmoudabady, M. Protective effects of medicinal plant against diabetes induced cardiac disorder: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 265, 113328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.113328 (2021).

Shen, Z. et al. Astragalus Membranaceus and salvia miltiorrhiza ameliorate diabetic kidney disease via the gut-kidney axis. Phytomedicine 121, 155129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155129 (2023).

Huang, M., Du, Z. & Zhai, W. Influence of Guben Xiezhuo Decoction on TCM syndrome of patients with chronic renal failure. J. Changchun Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 28, 980–981. https://doi.org/10.13463/j.cnki.cczyy.2012.06.054 (2012). (In Chinese).

Liu, Y. et al. Guben Xiezhuo Decoction inhibits M1 polarization through the Raf1/p-Elk1 signaling axis to attenuate renal interstitial fibrosis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 319, 117189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2023.117189 (2024).

Nogales, C. et al. Network pharmacology: Curing causal mechanisms instead of treating symptoms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 43, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2021.11.004 (2022).

Luo, T. T. et al. Network Pharmacology in research of Chinese medicine formula: Methodology, application and prospective. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 26, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11655-019-3064-0 (2020).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W357–W364. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz382 (2019).

Ru, J. et al. A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-6-13 (2014).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1373–D1380. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac956 (2023).

Amberger, J. S. & Hamosh, A. Searching online mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM): A knowledgebase of human genes and genetic phenotypes. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 58, 1.2.1–1.2.12. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.27 (2017).

Stelzer, G. et al. The genecards suite: From gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 54, 1.30.1–1.30.33. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.5 (2016).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2017: Quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D362–D368. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw937 (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Burley, S. K. et al. RCSB protein data bank: Tools for visualizing and understanding biological macromolecules in 3D. Protein Sci. 31, e4482. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.4482 (2022).

Chevalier, R. L., Forbes, M. S. & Thornhill, B. A. Ureteral obstruction as a model of renal interstitial fibrosis and obstructive nephropathy. Kidney Int. 75, 1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.86 (2009).

Romagnani, P. et al. Chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 17088. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.88 (2017).

de Cos, M. et al. Assessing and counteracting fibrosis is a cornerstone of the treatment of CKD secondary to systemic and renal limited autoimmune disorders. Autoimmun. Rev. 21, 103014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2021.103014 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Salidroside ameliorates renal interstitial fibrosis by inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20051103 (2019).

Zhou, J. et al. Bortezomib attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in kidney transplantation via regulating the EMT induced by TNF-α-Smurf1-Akt-mTOR-P70S6K pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23, 5390–5402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.14420 (2019).

Huang, R., Fu, P. & Ma, L. Kidney fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01379-7 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. EGFR family and Src family kinase interactions: Mechanics matters? Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 51, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2017.12.003 (2018).

Ren, Q. et al. Flavonoid Fisetin alleviates kidney inflammation and apoptosis via inhibiting Src-mediated NF-κB p65 and MAPK signaling pathways in septic AKI mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 122, 109772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109772 (2020).

Jiang, J. et al. SHP2 inhibitor PHPS1 ameliorates acute kidney injury by Erk1/2-STAT3 signaling in a combined murine hemorrhage followed by septic challenge model. Mol. Med. 26, 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-020-00210-1 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. NOK associates with c-Src and promotes c-Src-induced STAT3 activation and cell proliferation. Cell. Signal. 75, 109762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109762 (2020).

Livingston, M. J. et al. Autophagy activates EGR1 via MAPK/ERK to induce FGF2 in renal tubular cells for fibroblast activation and fibrosis during maladaptive kidney repair. Autophagy 20, 1032–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2281156 (2024).

Zeke, A., Misheva, M., Reményi, A. & Bogoyevitch, M. A. JNK signaling: regulation and functions based on complex protein-protein partnerships. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 793–835. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00043-14 (2016).

Wang, J. L. et al. ApoA-1 mimetic peptide ELK-2A2K2E decreases inflammatory factor levels through the ABCA1-JAK2-STAT3-TTP axis in THP-1-derived macrophages. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 72, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/fjc.0000000000000594 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. BMAL1 inhibits renal fibrosis and renal interstitial inflammation by targeting the ERK1/2/ELK-1/Egr-1 axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 125, 111140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.111140 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to the department of pharmacy of Zhangjiagang TCM Hospital for assistance with drug preparation and intragastric administration guidance.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82405281), Jiangsu Province Leading. Talents Cultivation Project for Traditional Chinese Medicine (Grant No. SLJ0330), 2024 Suzhou Science and Education Driven Healthcare Enhancement Project (MSXM2024006), Suzhou Science and Technology Development Plan Project (Grant No. SYW2024045), Suzhou Applied Basic Research Technology Innovation Project (Grant No. SYWD2024050), the Clinical Key Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Technology Special Project of Suzhou Municipal Health Commission (Grant No. LCZX202332), the Science and Technology innovation Project of Suzhou Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. SKY2023008), Zhangjiagang Youth Science and Technology Innovation Project (Grant No. ZJGQNKJ202411), and the Science and technology innovation project of Zhangjiagang Municipal Health Commission (Grant No. ZKYL2355).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. and Y.L. contributed equally to the initial manuscript. S.C. was responsible for network pharmacology and molecular experimental validation, while Y.L. handled drug preparation, animal model creation, and pathological analysis. M.W., Z.D., and S.Q. as corresponding authors, provided guidance on experimental design. M.W. supervised the animal experiments and edited the manuscript, while Z.D. and S.Q. provided funding support and revised the manuscript. L.Z. also provided funding support and guided experimental methods. J.W. and Z.X. participated in the experiments. Y.Z. guided the manuscript writing and experimental methods. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Liu, Y., Zhu, L. et al. Network pharmacology and experimental validation to elucidate the pharmacological mechanisms of Guben Xiezhuo decoction against renal fibrosis. Sci Rep 15, 30479 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16012-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16012-6