Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains difficult to treat due to systemic toxicity of non-selective therapies. To address this, we hypothesized that targeting the highly active mitochondria of cancer cells, which have considerably increased membrane potential compared with normal cells, could be a promising approach to induce a stronger anticancer effect. Here, we report a curcumin nanocarrier (TDC) synthesized by modifying PAMAM G4 dendrimers with triphenylphosphonium (TPP). This design enables mitochondrial targeting, leveraging the elevated membrane potential of cancer cells to enhance curcumin’s anticancer activity. According to the results, the TDC influences the secreted levels of INF-γ and IL-4 on tumor lysis-stimulated splenocytes. In tumor-positive groups, TDC also increased cell population (sub G1 phase) 3.5 times, which was remarkable compared to healthy groups. Consistent with this, in tumor-positive mice, the amount of ROS and the overall rate of TDC-induced apoptosis were increased by approximately 40–50%. In addition, TDC upregulates pro-apoptotic genes (bax, p53) and downregulates oncogenic genes (bcl2, p21, xiap) in the cancerous liver tissues, reflecting the anti-cancer effect of TDC as a mitochondria-targeted delivery system. Investigations conducted ex vivo on mitochondria isolated from liver and brain tissues revealed elevated levels of ATP, malonaldehyde (MDA), and reactive oxygen species (ROS), along with reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, all of which were linked to the process of apoptosis. Finally, the biodistribution findings indicate that the accumulation of TDC in the tumor and liver was considerably greater than that of free curcumin (FC), likely due to the rapid elimination of FC at the concentration tested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of Liver cancer as a global health challenge is growing worldwide1,2. The most prevalent form of liver cancer is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which includes almost 90% of cases. Unfortunately, the current management of HCC is not adequate. Chemotherapy, surgery, and radiofrequency ablation are usually directed toward shrinking the tumor bulk, while in most cases, the tumor relapses until the completion of the therapy. Available chemotherapy reagents have been demonstrated to show severe toxicity and side effects. These side effects are mostly due to the non-targeting function of the utilized drugs directly against tumor cells.

In this regard, the design and synthesis of targeting drugs employing natural phytocompounds with anti-cancer effects by considering minor physiological differences between cancer and normal cells would be helpful in diminishing the adverse side effects of chemical treatments. Using natural phytocompounds with anti-tumor effects could have more significant clinical benefits as they do not influence the physiology and survival of normal cells3,4. Curcumin comprises 2 to 8% of turmeric composition5 and it is highly noticed as an anti-cancer reagent because of its anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer features6. Curcumin as a flavonoid has minimum side effects compared with other chemotherapeutics. Co-administration of curcumin, besides other drugs, is a good approach improving the anti-cancer treatment responses7,8. The molecular mechanism of curcumin on cancer cells is through interaction with several cellular signaling pathways, which causes apoptosis induction, inhibition of proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis9,10. Therefore, it is worthwhile to design a targeted curcumin-based drug to enhance its efficiency against cancerous cells.

Mitochondria are the cellular powerhouse with the central role in providing energy, processing cell metabolisms, and controlling the redox homeostasis and apoptotic pathways. Therefore, they could be a valuable target in cancer therapy. Tumor cells have an exceptional ability to reprogram their cellular activities to accommodate cellular energy demands owing to the rapid proliferation and migration during cancer progression. Subsequently, mitochondria of cancer cells are more active and they have considerably increased membrane potential compared with mitochondria of normal cells11, so it comes as no surprise that cancer predominantly has been considered a mitochondrial disease by several studies12,13,14. Based on this knowledge, targeting mitochondria and increasing their permeability by a curcumin carrier could be a promising approach to induce a stronger anticancer effect15,16. However, the hydrophobic structure of free curcumin hinders its permeability from the highly negatively charged membrane of mitochondria17,18. We previously synthesized mitochondria-targeted dendrimeric curcumin carrierss (curcumin nano-carrier; TDC) that efficiently conquered limiting factors of free curcumin. Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimer at generation 4 was chemically conjugated on curcumin, then triphenylphosphonium (TPP) was added to the system to formulate a mitochondria-targeted carrier19. PAMAM G4 not only causes more stability and solubility of curcumin but also improves its accumulation in the mitochondria.

The spherical, Nano sized, and well-defined hyperbranched polymer structure of dendrimer gives that fundamental features for physicochemical and biological applications20. The dendritic polymer configuration provides internal empty spaces to proficiently conjugate with the drug. These created cavities are appropriate for maintaining the hydrophobic compounds, which helps increase their stability and solubility. Therefore, dendrimers are an excellent tool for encapsulating hydrophobic drugs and improve their pharmacokinetics21,22.

TPP is expected to have high lipophilicity owing to its stable positive charge and having three phenyl groups, which cause electrostatic affinity to the immensely negatively charged membrane of mitochondria and facilitate its penetration and accumulation in the mitochondrial matrix23,24. In this manner, the conjugated cargo with TPP could be specifically delivered into the mitochondria and accumulate in the matrix.

In the present study, we studied the anti-tumor effect of TDC in Hepatocellular carcinoma-bearing BALB/c mice models (HCC-bearing mice). We observed that TDC is an efficient way of curcumin delivery, affecting mitochondria of liver in tumor-bearing mice rather than healthy ones.

Materials and methods

Materials

Curcumin (purity of 95%), Thiobarbituric acid (TBA), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), carboxybutyl triphenylphosphonium bromide (Carboxy TPP) (purity of 96%), Trichloroacetic acid (TCA), bovine serum albumin (BSA), Ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethyl ether)-N, N,N′, N′-tetra acetic acid (EGTA), Chlorhydric Acid, Sodium phosphate dibasic dehydrate (Na2HPO4·2H2O), Magnesium Chloride, Hexahydrate, Potassium dihydrogen phosphate, Potassium chloride were provided from Merk (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Mannitol, Rhodamine 123, HEPES, EGTA, 2.7-Dichlorodihydrofluoresceindiacetate (H2DCFDA), 5, 5′-Dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), Glutathione, 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate (NPC), Tris-HCl, Coomassie blue G250, Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Blue (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Millipore-Sigma, Germany).

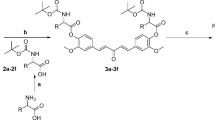

Curcumin nanocarrier synthesis

PAMAM dendrimers up to the fourth generation (PAMAM G4, with a nominal molecular weight of 14,215 Da) were generously provided by Dr. Shokri. Subsequently, TPP was attached to the surface amines of the dendrimer to create a dendrimeric system targeted towards mitochondria. To achieve this, TPP was first activated using DCC and NHS. Specifically, 14 mg of TPP was dissolved in 2 mL of methanol, followed by the addition of a mixture containing 1.3 mg of DCC and 0.7 mg of NHS in 2 mL of methanol to the TPP solution. The resulting mixture was stirred for 3 days at room temperature (RT) in the absence of light and under a nitrogen atmosphere, then dried using a rotary evaporator. Subsequently, the activated TPP was linked to the PAMAM G4 through the dendrimer’s surface amines. Following this, to attach curcumin to the surface of TPP-PAMAM, the hydroxyl group of curcumin was partially activated using NPC. In this synthesis, we have considered the amount of curcumin to dendrimer at 50%. Specifically, curcumin (35 mg, 40 mM, in dichloromethane) was mixed with NPC (15.4 mg, 0.7 M, in dichloromethane) and 30 µL of triethylamine, and stirred for 3 days at RT, in the dark, and under a nitrogen atmosphere. Subsequently, the activated curcumin was linked to TPP-PAMAM by slowly adding 35 mg of the activated curcumin (40 mM in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide) to a solution of 40 mg of TPP-PAMAM (2 mM in 1 mL DMSO). The resulting mixture was stirred for 5 days at RT in the dark. The final product was diluted 10 times with Milli-Q water and dialyzed (MWCO 3 kDa).

Cell culture

Hepa1-6 and mouse fibroblasts was obtained from the Pasture Institute, Iran National cell bank. The media (DMEM, Gibco, Germany) were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Germany). The cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 98% humidified incubator, and were kept sub-confluent by sub-culturing using trypsin.

Isolation of mitochondria

Mitochondria were extracted from hepatocytes following instructions identified by Shaki et al.26. Processes of isolation for mitochondria of hepatocytes are explained in our previous work19. The mice were euthanized under 5% isoflurane inhalation anesthesia (Isoflurin®, VetPharma, Barcelona, Spain) and cervical dislocation. All animals from the same cage were sacrificed on the same day. The brain was removed, and the cortex was isolated and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. The brain and plasma samples were stored at -80 °C for further analysis. For isolation of brain cell’s mitochondria, brains were removed after sacrificing the animals immediately. They were washed in an ice-cold isolation buffer (10 mM HEPES, 68 mM sucrose, 220 mM D-Mannitol, and 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4) and homogenized in a Potter–Elvehjem tissue grinder in an ice-cold buffer (10% v/w). Then, two-step centrifugation was performed to isolate mitochondria from tissue homogenates: at first, centrifugation was conducted at 3000 × g for 10 min. Next, the supernatant of the previous step was centrifuged at 11,500 × g for 15 min. Then, the obtained pellet was dispersed in 2 mL of PBS (pH 7.4). Protein concentrations were calculated by Peterson’s modification of the procedure suggested by Lowry and coworkers27.

Cells and mitochondrial viability assay

The effect of the prepared dendrimeric constructs on the viability of rat hepatocytes and isolated mitochondria was evaluated using the MTT assay (30). In our experiments, we utilized the MTT assay to assess both cell and mitochondrial viability. To conduct the cell viability assay, various cell types including Hepa1-6 and mouse fibroblasts were seeded on a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well, one day prior to each experiment. These cells were then treated with different concentrations of free curcumin (FC) (dissolved in 20% methanol), free dendrimer (FD), DC, and TDC (all dissolved in Milli-Q water). Subsequently, the MTT assay was performed on isolated mitochondria from hepatocytes and brain cells. For each sample in the study groups, 500 µg/mL of mitochondria (determined using the Bradford assay) were incubated with 100 µl MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL, 40 min, 20–30 °C). Following this, 100 µl DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals, and the mixture was further incubated for 15 min. The absorbance of each well was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm using a microplate photometer.

In vivo study groups and experimental overview

The BALB/c mouse model is used to evaluate the anti-cancer effect of mitochondria-targeted curcumin on hepatocellular carcinoma in this study. For this, we had two main study groups categorized into healthy and Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) BALB/c mice models, in which HCC mice models were created by subcutaneous injection of Hepa1-6 cells. Each main group (healthy and tumorized) was divided into four subgroups for treatments with free curcumin (FC), non-targeted dendrimeric curcumin (DC), mitochondria-targeted dendrimer without curcumin (TD), mitochondria-targeted dendrimer with curcumin (TDC), and PBS as the control group. Then, five animals per subgroup were allocated for immunological assays, and five other mice were used for toxicity tests. For immunological assays, secretion of IL-4 and INF-γ were investigated from isolated splenocytes in response to tumor antigens. For toxicity evaluations, MTT, Glutathione, ROS, MDA, ATP, and MMP assays were performed on extracted mitochondria from hepatocytes and brain cells. In addition, cell cycle, apoptosis, and ROS assays were conducted on hepatocytes using flow cytometry (Fig. 1).

Tumor models

Female inbred BALB/c mice (4–5 weeks old) were purchased from the Pasteur Institute of Iran and kept in an air-conditioned room with free access to food and water. The room had a controlled temperature of 25 ± 2 °C with a light-dark cycle condition. All animal experiments adhered to the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, and associated guidelines, as well as the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments. Procedures were approved by Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Committee of Ethics in Research (code: 1243302). Every effort was made to minimize animal suffering and to use the minimum number of animals necessary to obtain reliable results. The work was performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. All efforts were put into minimizing the number of used animals and their suffering. 5 × 106 Hepa1-6 cells were suspended in 100 µL of D-PBS, then mixed with 100 µL of matrigel, and subcutaneously injected into the flank of the mice to prepare the flank xenograft tumors in BALB/c mice. Once tumor mass became established, mice were randomly allocated into four groups (n = 10 animals per group). In each group, five mice were assigned to the immunological studies, five mice were allotted to the toxicity tests. The tumor sizes were monitored by caliper for three consecutive weeks. When the tumor size extended over 100 mm, treatments were conducted by diluting 0.5 mg of each drug in 500 µl PBS. Group 1 to group 4 were all tumor models, who respectively receiving TDC, DC, FC, TD, and only PBS as a control group. The same treatments in four groups were executed for healthy BALB/c mice. Injections were performed once a day for the first week, and then similar doses were injected every other day for the next eight days. All injections were performed intraperitoneally.

Preparation of tumor antigens

Tumor tissue was taken out via surgery and, after removing excess parts, smashed completely by a homogenizer, then crossed through a mesh and centrifuged (4500 g, 5 min, and 4 °C). The precipitate was resolved in an appropriate amount of PBS, and 10 µl PMSF (1mM) to inactivate serine proteases. Then, the obtained solutions were freeze-thawed using liquid nitrogen and a 37 °C water bath, for five times repeatedly and followed by sonication (30 s, 4-watt power, with 20-second intervals for five repetitions). The cell lysis was centrifuged (1000 g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant was harvested and dialyzed for 24 h. After dialysis, the collected tumor antigens were sterilized by a 0.22 μm syringe filter and stored at – 70 °C immediately. Bradford method was utilized to determine the protein concentration.

Cytokine measurements in the splenocytes

Spleens were removed aseptically and homogenized via a tissue grinder in an isotonic environment. Erythrocytes were lysed with lysing buffer (NH4Cl, KHCO3, Na2EDTA). Splenocytes were washed and suspended in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% L-glutamine 2, 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). 106 number of cells suspended in 1 ml DMEM and seeded per each well of the four well plates, and 20 µl tumor antigen (1 mg/mL) was added as a stimulator in each well. Two wells without tumor antigen and one well treated with phytohemaglutinin, (PHA) were considered negative and positive controls, respectively. After 72 h of incubation at standard cell culture conditions, the cell culture supernatants were collected for cytokine examinations. Concentrations of IL-4 and INF-γ were obtained utilizing a Cytokine assay kit (PeproTech, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Light absorptions were recorded in 450 nm wavelength by ELISA Microplate Readers.

Cell cycle, apoptosis and ROS assays of hepatocytes

Hepatocytes of BALB/c mice were isolated according to the method of Charni-Natan et al. [25] and were detailed in our previous study19. Then, the cell cycle and apoptosis were examined on mice hepatocytes, followed by curcumin treatments. For this purpose, hepatocytes were treated with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V/FLOUS-PI buffer to study cell cycle and apoptosis, respectively. These experiments were conducted immediately after the isolation of hepatocytes and just before performing the flow cytometry. All tests were performed in triplicates. The ROS content of isolated hepatocytes was also measured. In this regard, isolated hepatocytes of the healthy and tumor model mice were treated with 500 µl of 10 mM of H2DCFDA for 45 min at 37 °C. Then, the ROS content was determined using flow cytometry (FACS Calibur, Germany) device at excitation/emission of 495/520 nm. The H2O2-treated sample (250 µM) was used as the positive control. The treatments were performed in triplicates and reported as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Mitochondrial ROS assay

ROS analysis was performed on the isolated mitochondria from the liver and brain tissues of the treated study mice groups. For this purpose, 500 µg of mitochondria from each sample was suspended in 1 mL Tris buffer and mixed with 1 mL of 2′, 7′-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (0.16 μm) and maintained for 20 min at 37 °C. Finally, the absorbance of the produced ROS was determined by spectrofluorimetry at the excitation of 490 and emission wavelengths of 520 nm. H2O2-treated samples (250 µM) were considered positive controls. The experiments were executed in triplicates and presented as the means ± SEM.

Glutathione assay of mitochondria

Ellman’s reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used for measuring the mitochondrial Glutathione on the liver and brain of two groups of normal and tumorized mice. The experiment process is available with details in our previously published paper19.

Mitochondrial lipid peroxidation (MDA) evaluation

500 µg of isolated mitochondria were suspended in 1 mL Tris buffer. Then, 250 µL TCA (20%) was added to each sample and followed by centrifugation at 3000 g, 4 °C, for 15 min. 200 µL of the supernatant was mixed with 1 mL TBA (3%) and incubated in a boiling water bath for 30 min. Then, the resulting MDA-thiobarbiturate was measured by the absorbance intensity at 540 nm using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer, which compared to the standard curve prepared by tetramethoxypropane.

Assay of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

Mitochondrial membrane potential is another parameter associated with apoptosis, which collapses during apoptosis. The influence of the curcumin carriers on the MMP status of each sample was investigated using Rhodamine123 fluorescent dye. In this prospect, an equal 500 µg of the mitochondria samples in 1 ml suspension was mixed with 100 µL of Rhodamine123 solution (10 µM) and kept for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, the mitochondrial membrane potential of each sample was quantified at the excitation/emission wavelengths of 490 nm/522 nm utilizing a Tecan ELISA reader.

Evaluation of mitochondrial ATP content

The mitochondria ATP content is a valuable parameter for indicating the induced cell death pathway (apoptosis or necrosis) as a consequence of any treatment28. Suspension of 500 µg mitochondria was centrifuged at 155 g for 5 min. Then the pellets were lysed by a lysis buffer. Next, ATP amounts were measured by the luciferase assay in a luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, GmbH). The data were obtained from three independent experiments and calculated as mean ± SEM.

Cancer-related genes expression analysis

Expression changes of multiple cancer-related genes, including bcl2, bax, xiap, p53, p21, and rb1, were examined by qPCR on the liver tissues. Briefly, the total cellular RNA was obtained from each sample by TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen). Then, the equivalent cDNAs were synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Next, qPCR was implemented using an equivalent amount of each sample’s cDNA as the specific scheduled program for primer pair apiece. The utilized primers and the size of their PCR products are listed in Table S1.

Biodistribution analysis

To evaluate the in vivo biodistribution pattern of free curcumin (FC) compared with the TDC nanocarrier, drug solutions were intravenously administered to tumor-bearing mice and images were captured 2.5 h after injection with a natural fluorescence excitation/emission at 405/420 nm. For the biodistribution study, three animals (n = 5) were used per group.

Statistical analysis

We performed Student’s t-test in GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 to compare two means and determine the statistically significant differences between the two groups. The P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Curcumin nano carrier synthesis and characterization

In this study, a curcumin nanocarrier was synthesized using G4 of PAMAM dendrimer. Briefly, TPP a mitochondria-targeting moiety, and curcumin were bound to the surface of synthesized dendrimer G4 to produce TDC carrier for targeted curcumin delivery to the mitochondria. The comparison between the non-targeted curcumin carrier without TPP (DC: dendrimer + curcumin) and the targeted carrier without curcumin (TD: TPP + dendrimer) was conducted by synthesizing both types of carriers. The size, charge, and shape of the curcumin constructs were then evaluated using Nanosizer, AFM, and TEM methods (Table S2 and Fig. 2A-C). The TEM and AFM images provided visual evidence of nanosized particles with a spherical morphology, which was further confirmed by DLS analysis. The average hydrodynamic sizes of DC (PDI = 0.3) and TDC (PDI = 0.25) were measured to be 113.5 ± 5.5 and 61.2 ± 7.2 nm, respectively, showing moderately polydisperse nanoparticles (Fig. 2.). Additionally, since TPP carries a positive charge, we observed a significant shift in the zeta potential of the nanocarrier from 2.9 (unmodified, DC) to positive (TPP-conjugated, TDC), further supporting surface modification, and the successful binding of TPP on the surface of the dendrimer (Table S2, Fig S1). This enhanced charge of TDC can be attributed to the conjugation of TPP ligands on the surface of the dendrimer. In this regard, the successful conjugation of TPP to the nanocarrier surface was also verified using 1 H NMR spectroscopy. The TPP-PAMAM spectrum revealed new aromatic proton signals (7–8 ppm), confirming TPP linkage to the dendrimer (Fig S2).

H & E staining and tumor size measurement

For, in vivo and ex vivo assays and biodistribution analysis tumor-bearing mice were treated with all kinds of nano carriers DC, TD, TDC to understand better our drug delivery system behavior and efficacy in an animal model. In order to achieve this objective, tumors were established locally by injecting Hepa1-6 cells into BALB/c mice subcutaneously. Drug injections were administered once subcutaneous tumors exceeded 100 mm³. The results depicted in Fig. 3. demonstrate that the administration of curcumin injections led to a more noticeable reduction in the size of hepatocellular model mice tumors with TDC, DC, and FC (Fig. 3, Fig S3). Furthermore, apart from the development of subcutaneous tumors, metastasis to the liver, brain, and lung was observed (Fig. 4A-J). The confirmation of metastasis in these organs was accomplished by examining tissue samples using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, which revealed the presence of cancer cells in these tissues, as illustrated in Fig. 4A-J. Additionally, Fig. 4k, provides evidence of tumors in the liver. To further investigate the anticancer effects of curcumin carriers, the mitochondria of liver and brain tissues from both hepatocellular carcinoma and healthy BALB/c models were studied, as shown in Fig. 1.

In vivo study of the nanocarriers in tumor-bearing mice. Dosing days (A). The formation of subcutaneous tumors after injection of Hepa1-6 cells in BALB/c mice (B). Tumor size variation in response to different treatments (C). Con = control, TD = targeted dendrimer without curcumin, FC = free curcumin, DC = non-targeted dendrimeric curcumin, TDC = mitochondria-targeted dendrimeric curcumin.

Representative images of different virtually H & E stained tissue types. Primary tumor (A) and cancerous cells formation after injection of Hepa 1–6 cell line to BALB/c mice. H & E staining indicated the distant metastasis of cancer cells to the liver (C, D), cancer cells to the Lung(F, G) and brain (I, J). Targeted delivery of curcumin via TDC to liver (D) and brain (J). Metastatic tumors in liver, red dashed circles indicate tumors position (K).

Effect of the curcumin nano carrier on the viability of the cells and the isolated mitochondria

The impact of the prepared delivery system on cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay on various normal and cancerous cell lines mouse origins. The toxicity results of the evaluated constructs are summarized in Fig. 5. The findings revealed that the FD and TPP-conjugated dendrimer exhibited minimal toxicity towards both cancerous and normal cell lines at the concentrations tested. However, FC, DC, and TDC displayed a selective toxic effect on cancer cells Hepa1-6 and normal cells mouse fibroblasts. Notably, TDC demonstrated significantly higher toxicity in cancer cells, particularly at concentrations exceeding 25 µM of curcumin, unlike FC and the untargeted construct (DC). Furthermore, the impact of TDC and DC on the viability of isolated mitochondria from rat hepatocytes is depicted in Fig. 5. The data indicated that concentrations above 35 µM of curcumin significantly affected the viability of isolated mitochondria. In this respect, the selectivity index (SI), calculated as the ratio of IC50 for normal cells to that of cancer cells, demonstrated that TDC possesses the highest selectivity for cancer cells. At a concentration of 35 µM, the SI for TDC was approximately 2.1, while for DC and FC, the values were 1.5 and 1.2, respectively. This demonstrates the superior selective toxicity of the TDC nanocarrier. The time-dependent nature of the cytotoxicity was also evident, with all formulations showing increased effects at 48 h compared to 24 h. Notably, TDC demonstrated the most signifi-cant increase in toxicity over this period, highlighting its sustained and potent effect. The enhanced impact of dendrimeric-curcumin constructs on isolated mitochondria suggests a potential improvement in mitochondrial uptake and overall drug efficacy.

Cell viability assay. The mitochondria-TDC and untargeted-DC were evaluated on cancer cells Hepa1-6 and normal cells mouse fibroblasts at different curcumin concentrations from 5 to 45 µM. The cells viabilities were measured by the MTT assay. The rate of increased MTT assay by TDC is higher than other treatments, especially in the HCC tumorized mice (P value < 0.0001). The results are presented as the means ± standard deviations of at least three independent repeats.

Cytokine assays in spleen cell culture

IFN-γ, a key cytokine in the T-helper 1 (Th1) immune response, is known for its role in anti-tumor immunity by activating cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. Conversely, IL-4 promotes a T-helper 2 (Th2) response, which can often be associated with tumor progression and immune evasion. In this regards, IFN-γ and IL-4, as key cytokines in regulating immune responses, were measured in splenocytes to examine the immune responses influenced by drug treatments in tumorized mice. Isolated splenocytes were cultured and stimulated with tumor antigens for 72 h in a standard cell culture environment. Then, the amounts of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the supernatants of the spleen cell culture were measured using a sandwich ELISA method. The results indicated the elevated secretion of IFN-γ in tumorized mice treated with TDC, DC, and FC compared to the untreated tumorized group in a clear upward trend (TDC > DC > FC). The elevation of IFN-γ was significantly higher in the TDC -treated group. Otherwise, IL-4 had lower levels in TDC < DC < FC treated mice, respectively. IL-4 was secreted distinctly lower in TDC treated group related to the control. The variation in secreted levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ followed the same pattern in the opposite direction among TDC, DC, and FC-treated groups. As expected, the TDC is the most effective curcumin carrier, influencing the INF-γ and IL-4 secretion (Fig. 6).

Cytokine assays in spleen cell culture.IFN-γ (A) and IL-4 (B) production by splenocytes of treated hepatocellular cancer model BALB/c mice. There are significant elevated IFN-γ and reduced IL-4 secretion by curcumin treatments, TDC had the most significant (P value < 0.0001) effect compared with FC and DC. The graphs are presented as Mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice per group. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments.

Effect of TDC on the hepatocytes cell cycle and apoptosis

The cell cycle status was studied using propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry (Fig S4). All the curcumin carriers induced increased rates of cell population in the sub G1 phase (P-value < 0.0001) compared with untreated groups either in positive or negative tumor mice. However, as data are shown in Fig. 7a, these rates of elevation in the tumor-positive groups are remarkably higher than in the healthy groups. The most important finding of this experiment is the remarkably higher induction of the sub-G1 population by TDC treatment compared with DC and FC (TDC > DC > FC). TDC, as mitochondria-targeted curcumin carrier, acted more efficiently than DC and FC to increase tumor cell population in sub-G1 and probably induce cancerous cells death in a targeted manner, which is desirable for an anti-cancer drug. In addition, the incidence of apoptosis was investigated by AnnexinV-PI staining and flow cytometry (Fig S5). Obtained data indicated that all curcumin carriers induced apoptosis in all healthy and cancerous mice but remarkably higher in tumorous samples (P-value < 0.0001). As we expected, TDC caused more incidence of apoptosis compared with free curcumin or DC. The overall rate of apoptosis induced by curcumin carriers in tumor-positive mice was approximately 30–50%, while this rate for tumor-negative samples was 14–27% (Fig. 7b). To further quantify the selectivity, we calculated the ratio of control-corrected apoptosis rates in tumor-positive mice to that in healthy mice. The ratio for the TDC group was approximately 3.1, while for FC and DC, the ratios were 2.4 and 2.6, respectively. This comparative analysis demonstrates the superior in vivo selectivity of TDC for tumor cells, a highly desirable characteristic for an anti-cancer drug. These results imply that all applied curcumin carriers can cause a considerable rate of apoptosis in the tumor cells, which is more than in normal. However, the effect of TDC is significantly higher on the tumor tissues.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle and Apoptosis assay. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle. In the HCC samples, all curcumin treatments induced remarkably elevated cells population in the sub-G1 phase (P-value < 0.0001), meanwhile TDC had the most impact on the increased cells population in the sub-G1. N = 3 mice per group. (B) Apoptosis assay. Induction of apoptosis by all curcumin carriers were significantly higher compared with their untreated controls. The rate of increased apoptosis by TDC is higher than other treatments, especially in the HCC tumorized mice (P value < 0.0001), graphs are shown as Mean ± SEM (C). N = 3 mice per group. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments.

ROS flow cytometry analysis in the isolated hepatocytes

We evaluated the alteration of ROS in the isolated hepatocytes. The increased amount of ROS followed by an anti-cancer drug treatment designates the better efficiency of the drug since it can induce apoptosis and lead to the eradication of the cancer cells. Our observations from this assay revealed that the elevation of ROS by all curcumin treatments in tumorized samples was higher than in healthy groups. The rate of ROS elevation in both tumorized and healthy groups had an upward trend. The most elevated rates of ROS belonged to the TDC and then DC and FC, respectively. In positive tumors, all curcumin carriers significantly (P-value < 0.0001) raised ROS amounts in hepatocytes compared with the untreated tumorized mice. Also, in the healthy groups, all curcumin-induced ROS elevation. The rates of significance obtained from t-test analysis for TDC, DC, and FC treated groups compared with untreated healthy controls were P-value < 0.0001, P-value < 0.001, P-value < 0.01, respectively (Fig. 8).

ROS flow cytometry analysis. ROS levels in the isolated hepatocytes from the treated healthy (A) and HCC model BALB/c mice (B) were examined by H2DCFDA in a flow cytometry instrument. Obtained data from the flow cytometry were analyzed by Flowing software (Version 2.4.1). H2O2 were applied as a positive control. Graphs are presented as Mean ± SEM (C) separately for healthy (negative tumor) and HCC model BALB/c mice (positive tumor). In the healthy study group TDC, DC, and FC treated samples were significantly (P value < 0.0001, < 0.001, 0.01, respectively) elevated. The increased rate of ROS influenced by curcumin treatments is higher in HCC models compared with the healthy samples. Hepatocytes of all treated HCC mice compared with its untreated control had significantly (P value < 0.0001) raised amount of ROS, which TDC among others had the most significant effect. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments.

Viability assay of the mitochondria following curcumin treatments

MTT assay was performed to evaluate the alteration of viability by treatments on the isolated mitochondria from the liver and brain cells of normal and tumorized mice. Results indicated that viability was more affected in tumor positives than in healthy mice. We observed that viability declined nearly 50% in the examined mitochondria from liver tissues of tumorized mice in all treated groups. Viability in healthy samples by FC reached 90% and decreased to 72% by TDC treatment. So, TDC showed the most potent toxicity. However, as we expected, healthy samples were less affected than tumor model mice. As graphs are shown in Fig. 9a, curcumin carriers had no significant effect on viability in brain tissues. Although, the same slightly downward trend of susceptibility was observed by FC, DC, and TDC, respectively. The observed minimal effect on brain tissue viability in healthy mice, despite the presence of the TPP targeting moiety, can be attributed to the intact blood-brain barrier (BBB), which effectively restricts the passage of these nanocarriers. Conversely, the BBB in the tumorized mice is likely compromised due to the presence of metastatic cells, enabling TDC to cross this barrier and exert its therapeutic effect, as confirmed by our biodistribution and ex vivo assays. This explains the more pronounced effect of TDC on brain tissues in tumor-positive mice.

Mitochondrial MTT, ROS and GSH analyses. (A) MTT assay. Ex vivo examination of curcumin carriers treatments on cell viability using extracted mitochondria from liver and brain tissues of healthy and tumorized BALB/c mice. All curcumins induced significant declined cell viability in both examined tissues, however, this reduced cell viability is evidently higher in positive tumors rather than tumor negatives. (B) ROS analysis. The effect of the curcumin treatments on the ROS levels of extracted mitochondria from liver and brain tissues in positive tumor BALB/c mice and healthy BALB/c mice. TDC compared with untreated control and FC treated groups significantly (P value < 0.0001) increased the ROS amount in both examined tissues. The amount of ROS was quantified based on the produced DCF fluorescence intensity, utilizing fluorometric analysis. (C) GSH analysis The Glutathione levels of isolated mitochondria from examined tissues in positive tumor and negative tumor samples treated with curcumin carriers. The GSH level only was significantly reduced in mitochondria of liver tissue grafted from TDC treated tumorized mice (P value < 0.001). All graphs are indicate as Mean ± SEM, N = 3 mice per group. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments.

Effect of TDC on the mitochondrial ROS

We conducted a ROS assay on the isolated mitochondria from the liver and brain tissues of treated healthy and tumorized mice to understand more about the molecular effect of prepared TDC. Produced levels of ROS in tumor tissues in response to a drug treatment indicate the efficiency of the treatment since it can trigger programmed cell death and consequently eliminate the cancer cells28. We observed that TDC and DC-treated tumorized mice had remarkably increased amounts of ROS in both the liver and brain tissues compared with untreated tumorous mouse models (P-value < 0.0001). The efficiency of TDC and DC for inducing ROS production is evident from the graphs shown in Fig. 9b. TDC effect in elevating ROS production was higher than DC in all study groups. Also, this effect by curcumin carriers was distinctive in mitochondria of liver and brain tissues of tumorous mice rather than healthies.

Reduction of mitochondrial glutathione (GSH) by TDC

The oxidative stress induction with curcumin treatments was examined by measuring the mitochondrial glutathione content. The decline of mitochondrial glutathione of tumor cells is a desirable event followed by anti-cancer reagent treatments. Our data showed that DC and TDC significantly (P-value < 0.05, P-value < 0.001, respectively) reduced the glutathione content of liver and brain tissues in tumorized mice. Notably, this rate of glutathione depletion was more efficient in the TDC treated samples compared with DC, which again indicates the effectiveness of TDC as a mitochondria-targeted curcumin drug. As plots are shown in Fig. 9c, we did not have significantly reduced GSH amount in healthy BALB/c mice by TDC. However, we observed elevated rates of GSH by FC and DC in these samples, which could be due to the well-known protective effect of curcumin in normal cells.

Elevation of the mitochondrial lipid peroxidation (MDA) by TDC

ROS induction leads to lipid peroxidation in cancer cells. Stimulation of excessive stress oxidative in tumor cells and consequently increasing the rate of ROS and MDA by anti-cancer reagents are appropriate approaches to eradicate tumor cells selectively. Therefore, we evaluated the MDA rates in the mitochondria of brain and liver tissues of treated healthy and tumorized mice. Our obtained results indicated that the TDC was able to significantly raise the MDA in all study groups (P-value < 0.0001). However, by comparing graphs between tumor positive and tumor negative groups, we can propose that efficacy of TDC in the induction of MDA in tumor positives, especially in the brain, is higher (> 50%) than the brain (14%) or liver (> 30%) tissues of tumor negatives. Probably, the nature of the brain tissue could influence the observed rate of MDA induction in this tissue. Elevated rates of mitochondrial MDA cause further disruption in the electron transfer chain and subsequently leads to the more release of cytochrome c, which mechanistically can be in favor of apoptosis incidence (Fig. 10a).

Mitochondrial MDA, MMP and ATP analyses (A) Mitochondrial MDA assay. MDA assay was performed by MDA-thiobarbiturate (MDA %) on extracted mitochondria from hepatocellular cancer model BALB/c mice (positive tumor) and healthy BALB/c mice (negative tumor) treated with various curcumin carriers. TDC was able to significantly raise MDA in both examined tissues either in positive and negative tumor samples (P value < 0.0001). The elevation of MDA in the brain of tumorized mice is even higher. (B) MMP assay. The effect of the curcumin carriers on the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was analyzed by Rhodamine 123 assay on isolated mitochondria from hepatocellular cancer BALB/c mice and normal BALB/c mice. All in liver brain positive P value < 0.0001. MMP was elevated significantly (P value < 0.0001) almost by all curcumin treatments in all study groups compared with their untreated controls. MMP in mitochondria of brain tissues grafted from tumorized mice were most elevated by curcumin treatments, especially with TDC. (C) ATP assay. The luciferase assay was used to quantify the mitochondrial ATP levels in the tumorized and healthy BALB/c mice treated with various curcumin carriers. The ATP level was immensely increased in the mitochondria of liver and brain tissues of the TDC treated HCC mice compared with untreated HCC mice (P value < 0.0001) and TDC treated healthy mice. Graphs are presented as Mean ± SEM, N = 3 mice per group. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments.

Elevation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

The efficacy of the prepared curcumin carriers on the targeting of mitochondria also was examined by MMP (Mitochondrial membrane potential) assay, a precious method to measure the mitochondrial health by monitoring changes in the mitochondrial membranes. We used Rhodamin 123 as a cationic fluorescent dye for measuring the potential variation of mitochondrial inner membrane. Rhodamin123 seeps through and remains inside the healthy mitochondrial membranes, whereas in the damaged mitochondria, it is the contrary. Disruption of MMP due to the MDA elevation influenced by curcumin treatments has been established previously. We also observed the same effect of curcumin in the liver and brain tissues, either in HCC or healthy mice. All treated samples showed higher disrupted MMP than their control group (P-value < 0.0001). However, this experiment either confirmed the most efficiency of TDC compared with DC and FC, which caused more disturbance in the inner membrane of mitochondria (TDC > DC > FC). As data are shown in Fig. 10b, we can conclude that TDC is the most efficient curcumin drug to damage mitochondria. TDC probably affects the mitochondrial capacity to retain Rhodamin123 by changing the charges of the mitochondrial internal membrane. This effect of the TDC could be explained by its highly positive charge, which causes its better accumulation inside the inner membrane of mitochondria, then disrupts the membrane integrity and potential. In our opinion, TDC uses the benefit of positively charged TPP in its structure to cause the better accumulation of curcumin in the mitochondria. Probably, this feature is responsible for the most significant effect of TDC compared with DC and FC.

Elevation of the mitochondrial ATP by TDC

One of the primary functions of mitochondria is the production of ATP through the respiratory transport chain system. Evaluating of ATP content of mitochondria gives us a clue to find out the mechanism of cell death followed by drug treatment. Apoptosis is a highly regulated procedure that is ATP-dependent29, and necrosis is independent of energy. Depletion of cellular ATP causes necrosis30. In this study, in all treated groups, we observed a significantly increased amount of ATP content in extracted mitochondria from liver and brain tissues of hepatocellular model and healthy mice (P value < 0.0001). However, according to the graphs in Fig. 10c, the TDC effect on the elevation of ATP content in both examined tissues is remarkably higher than DC and FC, which is remarkably higher in tumor-positive samples. We observed 120% ATP content for liver tissues of TDC treated tumor negatives. In comparison, this rate for TDC -treated tumor positives was 220%.

Expression changes of cancer-related genes by curcumin treatments

An optimized qPCR method was conducted for quantifying bcl2, bax, xiap, p53, p21, and rb1 genes, due to their critical roles in cancer occurrence and progression. The obtained data revealed that treatment with curcumin carriers leads to the elevated expression of bax, p53, two well-known pro-apoptotic genes, and decreased expression of bcl2, p21, and xiap with anti-apoptotic roles in tumor tissues. TDC had the most significant impact on the expression of these cancer-associated genes compared with FC and DC. Like the other tests, another prominent finding of this experiment is the higher efficiency of curcumin treatments, especially TDC, on the liver of tumor positives rather than healthy tissues for all studied genes. Overall, increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes (bax, p53) and reduction of oncogenic genes (bcl2, p21, xiap) influenced by curcumin treatments perfectly reflects the anti-cancer effect of curcumin carriers, especially TDC as a mitochondria-targeted carrier. The rb1 expression was affected with an unusual pattern. It was reduced in both tumor positive and tumor negative samples by DC and TDC treatments but increased in FC treated tumor positive samples (Fig. 11). Therefore, we could not find a correlation between rb1 expression and curcumin treatment in hepatocellular cancer model mice. Prior studies claimed that rb1 role in apoptosis is controversial, which may play as an inhibitor or inducer of apoptosis depending on the kind of cell and the treated reagents31,32.

Real time PCR analysis. RNA expression changes of bax, bcl2, p21, p53, xiaop, rb1 in the liver tissues of normal BALB/c mice (A) and curcumin treated HCC model (B). TDC led to the dramatically increased expression of p53, especially in positive tumor samples (P value < 0.0001). The bcl2, xiaop, rb1, and p21 were respectively the most declined genes (P value < 0.0001) by TDC in HCC positives versus healthy samples. The bax was significantly (P value < 0.001) increased by TDC in both cancerous and healthy samples. Data are indicated as Mean ± SEM, N = 3 mice per group. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between treatments.

Biodistribution analysis& safety assessment of TDC

With a natural fluorescence excitation/emission at 405/420 nm, curcumin can be tracked by confocal microscopy. The results, depicted in Fig. 12 and Fig. S8, revealed that the accumulation of TDC in the tumor site and liver was significantly higher compared to FC and TD (Fig. S8). Additionally, fluorescent signals were observed in the kidney and lung following TDC treatment. Conversely, FC exhibited limited distribution (with low fluorescent intensity) in the liver, spleen, lung, and tumor, when compared to TDC. A significant fluorescence signal was also detected in the bladder and stomach for FC and TDC (Fig. 12. & Fig. S8). Furthermore, we monitored potential systemic toxicity by tracking body weight changes in BALB/c mice throughout the experiment. No significant weight loss or overt toxicity was observed in the TDC-treated group, indicating good tolerability. A transient, minor weight loss (~ 3.5%) was noted in the untargeted DC group on day 20, which later resolved. This effect could be attributed to slight aggregation-induced transient inflammation, though no such issue occurred with TDC (Fig. S6). Additionally, survival data further support TDC’s safety and efficacy, as TDC significantly extended median survival to 40 days vs. 27 days (FC) and 35.5 days (DC) (*p = 0.024*, log-rank test), and No mortality or adverse clinical signs (e.g., lethargy, reduced activity) were linked to TDC administration (Fig. S7). Thus, while our study did not include comprehensive long-term effects and immunogenicity analyses (which will be addressed in future work) the absence of weight loss, coupled with enhanced survival, suggests favorable in vivo safety of TDC (Fig. S6, Fig S7).

Discussion

The anti-cancer effect of curcumin is well-known in liver cancer due to its anti-proliferative, apoptotic, and anti-angiogenic features. These promising features of curcumin, besides its safety and protective effect on healthy cells, make it an attentive adjuvant remedy for cancer treatment4, but a hurdle to conquer for the pharmaceutical application of curcumin is its insolubility in the physiological environment33. To achieve the most desirable treatment effects, we need to enhance the solubility of curcumin and its targeted delivery system. For this purpose, we synthesized a TPP-dendrimeric carrier as a mitochondria-targeted delivery system. Recent researches suggest that cancer is basically a mitochondrial metabolic disease12,13,36, which could be a vulnerable target for cancer therapy. Mitochondrial metabolism is essential rapid proliferation, metastasis, and survival of tumor cells14. The highly charged mitochondrial membrane is a barrier against mitochondria-targeted drugs, which thwarts the crossing and accumulation of hydrophobic or anionic combinations. To conquer this hurdle, utilizing PAMAM G4 is a desirable strategy to improve the mitochondrial accumulation of curcumin. PAMAM at generation 4 is less toxic than its higher generation (> G4), and contrasting its lower generations (i.e., G0-G3), provides a three-dimensional conformation with large internal cavities to entrap the guest molecules in it. These features render increased solubility of hydrophobic molecules in an aquatic environment [34–37]. Furthermore, PAMAM G4 contains 64 accessible reactive groups like primary amines on its surface, which leads to efficient conjugation with drug molecules38. Another advantage of PAMAM G4 beyond its higher generations is its appealing molecular weight (14 kDa), which is lower than the threshold of elimination through the kidneys (40 kDa), causing less body accumulation and toxicity. These reasons motivated us to employ PAMAM G4 for the curcumin delivery. For active mitochondria targeting, we conjugated (Triphenylphosphonium) TPP on its surface. TPP is the most desirable molecule for mitochondria targeting [39, 40]. TPP has an enormous ionic radius owing to resonance-mediated diffusion of positive charge through three phenyl circles, which causes the unusual lipophilicity of TPP and transcendence from the membrane without a transporter40. Then, TPP massively accumulates inside the inner membrane of mitochondria by changing the potential of the inner membrane41.

Curcumin exhibits appealing pharmacological activities that benefit cancer treatment by preventing proliferation, growth, apoptosis, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis of cancer cells through various molecular pathways. Several studies have reported that curcumin inhibits cancer progression through its anti-inflammatory feature41,42,43,44,45,46. We observed that TDC affects cell cycle and cellular viability probably by elevating ROS and MDA rates and reducing GSH, which finally leads to the incidence of apoptosis. Our ex vivo investigations on extracted mitochondria indicated the elevated rates of MDA, ROS, and reduction in GSH amount (Figs. 9 and 10.), which are representative of induced oxidative stress after curcumin treatments. MDA elevation causes an interruption in the mitochondrial electron transfer chain, which facilitates the release of cytochrome c and finally renders apoptosis in tumor cells. Disruption of MMP was another outcome of MDA elevation that occurred by curcumin (Fig. 10.), especially by TDC. Elevation of MMP and occurrence of apoptosis associated with mitochondrial membrane potential consequence of curcumin treatment has been reported in various cell lines such as HepG248, MCF7 BCSCs (breast cancer stem-like cells)49, and A549 cells50. We observed this phenomenon with the most efficiency by TDC.

An excessive amount of ROS in cancer cells, besides a reduction in glutathione amount, leads to more oxidative stress conditions and damage to the cell membrane and macromolecules. Glutathione has a dual role in the progression of cancer. GSH, as an anti-oxidant, is critical to removing and detoxifying carcinogens, thereby impacting cell survival profoundly. However, it is reported that increased levels of GSH in some cancers protect tumor cells against chemotherapy and promote cancer progression. Also, in some cases, the elevated amount of glutathione is related to an increased metastasis rate [51]. The intracellular glutathione elevation is correlated with apoptosis resistance52, and its depletion induces apoptosis53. According to our observations in HCC tumor models, curcumin causes apoptosis in cancerous cells by affecting mitochondria (Fig. 7B.) Producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequently releasing cytochrome c from mitochondria by curcumin is a proven process15,16. It has been demonstrated that curcumin targets multiple enzymes in ROS metabolic pathway by interacting with them54. Elevation of ROS by TDC treatment was more significant in tumorized mice than in healthy samples in either liver or brain tissues. However, free curcumin at the same concentration did not affect ROS levels in tumor positives (Fig. 8.). Also, glutathione as a protective shield against oxidative reagents was declined most significantly by TDC in the liver of tumorized mice but not in the healthy groups. These observations indicate the selectively tumor-targeted effect of TDC (Fig. 9C.).

Data obtained from MTT and apoptosis assay proved the incidence of cell death by TDC. Elevated cell population in sub-G1 is another proof that indicates curcumin and strongly TDC force tumor cells to undergo apoptosis (Fig. 7A.). Compelling scientific studies proved the apoptosis-inducing activity of curcumin on several cancer types through various signaling pathways, including P53, AKT, NF-κB, Wnt/β-catenin, etc. [55]. So, exertion of the inhibitory effect by curcumin on cancer progression is not far from the mind. However, the prominent feature of the therapeutic function of curcumin is its selectivity, which preferentially induces anti-proliferative and apoptosis on tumor cells with a less significant effect on normal cells55,56,57,58,59. This phenomenon is particularly dose and time-dependent, which has been demonstrated by other studies [15, 58]. It is obvious that dose and exposure time vary depending on cell kind. In contrast, human and mouse healthy cell lines didn’t show toxicity of more than 40%, even up to 50 µM concentration of TDC19. The selectivity nature of curcumin for cancer cells versus normal cells is not completely clear to us. One reason could be the lower glutathione content in cancer cells, which causes more vulnerability of them to encountering the raised induced amount of ROS by curcumin [58]. Also, some studies claimed that curcumin accumulates preferentially in cancer cells rather than in normal cells61. Probably the higher number of mitochondria in cancer cells made them a better place to maintain curcumin and consequently influenced by that. Based on this knowledge, utilizing a mitochondria-targeted curcumin drug as TDC helps achieve better advantages of curcumin. Our findings indicated a significant increase in cell population in the sub-G1 phase by curcumin and dendrimeric curcumins, particularly in TDC-treated samples, which once again could confirm the apoptotic effect of the curcumin carriers, especially with TDC (Fig. 7.). Anti-cancer drugs often affect the cell cycle in variable ways. In several cases, they cause the cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase to prevent tumor growth. It has been shown that curcumin, as an anti-inflammatory drug, also has a similar effect on the cell cycle; however, different studies reported the cell cycle arrest at various phases by curcumin. For instance, it has been reported that treating U87MG cells (a glioma cancer cell line) with curcumin could influence the cell cycle at the sub-G1 phase. Other studies reported the arrest at the G2/M60,62,63. It is now approved that curcumin induces apoptosis through the activation of procaspase and releasing of cytochrome c into the cytosol. Further investigations in several cancer types, such as gastric64 and colorectal cancers65, demonstrated that curcumin has specific effects on cancer cellular processes, including the cell cycle.

Analysis of ATP showed elevated amount of ATP in hepatocellular mitochondria, which is indicative of observed cell death after drug treatments (Fig. 10C.). Elevation of cellular ATP during apoptosis even after DNA fragmentation has been reported previously. However, some other studies claim that mitochondrial ATP should be decreased during the early stages of apoptosis due to the disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential and halting of ATP production66. Although, some reports indicate that the production of ATP continues, and membrane potential remains intact even after cytochrome c is released66,67,68.

We monitored expression changes of some critical cancer-associated genes in the liver tissues of treated healthy and tumorized mice models. The altering expression of these genes is one of the mechanisms applied by curcumin to play as an anti-cancer reagent70,71. In this concept, TDC compared with DC and FC was the most effective curcumin carrier for all examined genes with more affectivity in tumor-positive samples (Fig. 11.).The P53 is a transcription factor with tumor suppressor activity regulating numerous prominent genes, including bax, bcl2, and p21 prompt apoptosis [72, 73]. The over-expression of bax accelerates apoptosis, while the bcl2 inhibits apoptosis74,75. The P21 protein suppresses some pro-apoptotic proteins, such as procaspase 3, caspase 8, and 10, which finally leads to the inhibition of apoptosis in a normal condition [76]. xiap (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis) is an essential member of the IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis protein) gene family, which suppresses apoptosis via inhibition of caspase-3 and − 7, and 977,78. Overexpression of xiap in multiple cancer cell lines has been reported79. A correlation between apoptosis inhibitory action of xiap and p53 genes status has been suggested in a study conducted on gastric cancer cell lines77. In the present study, the alterations of all these genes after curcumin treatment are benefit the occurrence of apoptosis and elimination of tumor cells, which indicates the favorable anti-cancer effect of this compound. Expression of bax (a pro-apoptotic gene) was increased, and p21, xiap, and bcl2 (anti-apoptotic genes) notably were decreased. The p53 expression was dramatically elevated by TDC treatment. The elevation of p53 probably affects the expression of other critical genes and finally leads to apoptosis. This could explained the observed more significant anti-cancerous effect of TDC in tumorized mice by considering the importance of p53 regulatory function. The effect of curcumin on the elevation of p53 expression has been proved by several studies62,80,81, and our results illustrated a similar function. Induction of p53 – associated apoptosis by curcumin has been revealed previously in MCF7 cells75 and basal cell carcinoma82. Therefore, it is predictable that p53 could be a key factor influenced by curcumin, which causes apoptosis of hepatocellular cancer cells. Interestingly, the effect of TDC on the elevation of p53 expression was in a superior trend compared with free curcumin and even DC.

We examined IL-4 and INF-γ levels in the extracted splenocytes from the treated tumor model and healthy mice to get an overview of our curcumin carrier’s effect on the immune response (Fig. 6.). Curcumin, in a normal condition, acts as an anti-inflammatory reagent and suppresses immune response83. However, some reports indicate the significant correlation between anti-cancerous effects of curcumin and immune response, such as accelerating proliferation of lymphocytes, increased secretion of INF-γ, and alteration of other interleukins levels83,84. Our results revealed elevated levels of INF-γ and declined secretion of IL-4 by the most effective ordinary with TDC, DC, and FC. According to these observations, TDC as a targeted curcumin carrier affects immune response more significantly. Escaping from the Th1 and stimulating the Th2 response is one strategy from numerous tools applied by tumor cells to evade the immune system [85]. According to the obtained results, curcumin carriers activate the Th1 response by elevating INF-γ and suppressing the Th2 response by reducing IL-4, which is a profit for an anti-tumor drug in cancer therapy. The results of biodistribution analysis suggest that there was a significantly higher accumulation of TDC in both the tumor and liver compared to FC. This difference is believed to be attributed to the faster elimination of FC at the specific concentration that was tested. This can be attributed to the highly lipophilic TPP ligand, which possesses three phenyl groups and a positive charge on phosphorous. These structural features enhance its association with cells and facilitate its specific targeting to mitochondria. Cancer cells often exhibit a higher abundance of mitochondria compared to normal cells, a phenomenon known as “mitochondrial hyperplasia.” In the liver, hepatocytes heavily rely on mitochondria as their primary energy source, playing a crucial role in facilitating extensive oxidative metabolism and maintaining normal liver function. Due to their heightened energy demands, these cells possess approximately 1000–2000 mitochondria within each cell. In line with this observation, our findings demonstrate that the utilization of mitochondria-targeted curcumin nanoparticles allows for the efficient delivery of curcumin to both tumors and the liver, resulting in elevated curcumin levels and enhanced permeability. Consequently, this approach prolongs the therapeutic effect of targeted drug delivery systems, enabling them to accumulate more effectively within tumor cells by specifically targeting tumor mitochondria.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully demonstrated that the mitochondria-targeted curcumin nanocarrier (TDC) represents a highly effective therapeutic agent, surpassing other tested formulations. The superior efficacy of TDC, evident in both the liver and brain tissues of our HCC-bearing BALB/c mice models, is primarily attributed to the triphenylphosphonium (TPP) moiety, which facilitates its specific and enhanced targeting of mitochondria. Our findings illustrate that TDC significantly outperforms both free curcumin (FC) and the non-targeted nanocarrier (DC). Mechanistically, TDC promotes apoptosis, upregulates key pro-apoptotic genes like p53 and bax, while simultaneously downregulating oncogenic genes such as bcl2, p21, and xiap. Furthermore, its cytotoxic effect is mediated through the induction of oxidative stress, evidenced by elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the lipid peroxidation biomarker malondialdehyde (MDA), coupled with a notable depletion of glutathione (GSH) in tumor cells. While TDC demonstrated superior efficacy in tumor models, a minor effect on healthy tissues was observed, consistent with the nature of potent therapeutic agents. However, the significantly higher impact on tumor-positive samples compared to healthy controls underscores the selective targeting advantage of TDC, which minimizes collateral damage to healthy cells. However, subsequent research will concentrate on evaluating the long-term effects of TDC administration, conducting comprehensive immunogenicity analyses, and further optimizing the nanocarrier system. These endeavors are essential to enhance its stability and scalability for eventual clinical translation, thereby validating TDC as a selective and potent therapeutic option for hepatocellular carcinoma and other malignancies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. In the “Data Availability” section, please clearly state Shahla Kianamiri should be contacted if someone wants to request the data from this study.

References

Llovet, J. M. & Beaugrand, M. Hepatocellular carcinoma: present status and future prospects. J. Hepatol. 38, 136–149 (2003).

Balogh, J., Victor III, D., Asham, E. H., Burroughs, S. G., Boktour, M., Saharia, A. & Monsour Jr, H. P. Hepatocellular carcinoma: A review. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 41–53 (2016).

Chintana, P. Role of curcumin on tumor angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian Health Sci. Technol. Rep. 16, 239–254 (2008).

Sharma, S., Tanwar, A. & Gupta, D. K. Curcumin: an adjuvant therapeutic remedy for liver cancer. Hepatoma Res. 2, 62–70 (2016).

Chattopadhyay, I., Biswas, K., Bandyopadhyay, U. & Banerjee, R. K. Turmeric and curcumin: Biological actions and medicinal applications. Curr. Sci. 44–53 (2004).

Maheshwari, R. K., Singh, A. K., Gaddipati, J. & Srimal, R. C. Multiple biological activities of curcumin: a short review. Life Sci. 78, 2081–2087 (2006).

Li, H. et al. Curcumin plays a synergistic role in combination with HSV-TK/GCV in inhibiting growth of murine B16 melanoma cells and melanoma xenografts. PeerJ 7, e7760 (2019).

Gao, J. et al. PEGylated lipid bilayer coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles co-delivery of paclitaxel and curcumin leads to increased tumor site drug accumulation and reduced tumor burden. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 140, 105070 (2019).

López-Lázaro, M. Anticancer and carcinogenic properties of curcumin: considerations for its clinical development as a cancer chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agent. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 52, S103–S127 (2008).

Kunnumakkara, A. B., Anand, P. & Aggarwal, B. B. Curcumin inhibits proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis of different cancers through interaction with multiple cell signaling proteins. Cancer Lett. 269, 199–225 (2008).

Gazzano, E. et al. Mitochondrial delivery of phenol substructure triggers mitochondrial depolarization and apoptosis of cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 580 (2018).

Martinez-Outschoorn, U. E., Peiris-Pagés, M., Pestell, R. G., Sotgia, F. & Lisanti, M. P. Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 11–31 (2017).

Giampazolias, E. & Tait, S. W. Mitochondria and the hallmarks of cancer. FEBS J. 283, 803–814 (2016).

Ghosh, P. et al. Mitochondria targeting as an effective strategy for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093363 (2020).

Duvoix, A. et al. Induction of apoptosis by curcumin: mediation by glutathione S-transferase P1–1 inhibition. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1475–1483 (2003).

Thangapazham, R. L., Sharma, A. & Maheshwari, R. K. Multiple molecular targets in cancer chemoprevention by curcumin. AAPS J. 8, 52 (2006).

Bonifácio, B. V., da Silva, P. B., Ramos, M. A. D. S., Negri, K. M. S., Bauab, T. M. & Chorilli, M. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems and herbal medicines: A review. Int. J. Nanomed. 1–15 (2014).

Thilakarathna, S. H. & Rupasinghe, H. V. Flavonoid bioavailability and attempts for bioavailability enhancement. Nutrients 5, 3367–3387 (2013).

Kianamiri, S. et al. Mitochondria-targeted polyamidoamine dendrimer–curcumin construct for hepatocellular cancer treatment. Mol. Pharm. 17, 4483–4498 (2020).

Wu, L. P., Ficker, M., Christensen, J. B., Trohopoulos, P. N. & Moghimi, S. M. Dendrimers in medicine: therapeutic concepts and pharmaceutical challenges. Bioconjug. Chem. 26, 1198–1211 (2015).

Noor, A., Mahmood, W., Afreen, A. & Uzma, S. Dendrimers as novel formulation in nanotechnology based targeted drug delivery. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 4, 1509–1523 (2015).

Tiwari, A. K., Gajbhiye, V., Sharma, R. & Jain, N. K. Carrier mediated protein and peptide stabilization. Drug Deliv. 17, 605–616 (2010).

Biswas, S., Dodwadkar, N. S., Piroyan, A. & Torchilin, V. P. Surface conjugation of triphenylphosphonium to target poly(amidoamine) dendrimers to mitochondria. Biomaterials 33, 4773–4782 (2012).

Zielonka, J. et al. Mitochondria-targeted triphenylphosphonium-based compounds: syntheses, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 10043–10120 (2017).

Charni-Natan, M. & Goldstein, I. Protocol for primary mouse hepatocyte isolation. STAR Protoc. 1, 100086 (2020).

Shaki, F., Hosseini, M. J., Ghazi-Khansari, M. & Pourahmad, J. Toxicity of depleted uranium on isolated rat kidney mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 1940–1950 (2012).

Peterson, G. L. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal. Biochem. 83, 346–356 (1977).

Karlsson, M., Kurz, T., Brunk, U. T., Nilsson, S. E. & Frennesson, C. I. What does the commonly used DCF test for oxidative stress really show?. Biochem. J. 428, 183–190 (2010).

Richter, C., Schweizer, M., Cossarizza, A. & Franceschi, C. Control of apoptosis by the cellular ATP level. FEBS Lett. 378, 107–110 (1996).

Leist, M., Single, B., Castoldi, A. F., Kühnle, S. & Nicotera, P. Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentration: a switch in the decision between apoptosis and necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 185, 1481–1486 (1997).

Ekhteraei-Tousi, S. et al. Inhibitory effect of hsa-miR-590-5p on cardiosphere-derived stem cells differentiation through downregulation of TGFB signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 116, 179–191 (2015).

Indovina, P., Pentimalli, F., Casini, N., Vocca, I. & Giordano, A. RB1 dual role in proliferation and apoptosis: cell fate control and implications for cancer therapy. Oncotarget 6, 17873 (2015).

Anand, P., Kunnumakkara, A. B., Newman, R. A. & Aggarwal, B. B. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 4, 807–818 (2007).

Mukherjee, S. P., Davoren, M. & Byrne, H. J. In vitro mammalian cytotoxicological study of PAMAM dendrimers–towards quantitative structure activity relationships. Toxicol. In Vitro 24, 169–177 (2010).

Mukherjee, S. P., Lyng, F. M., Garcia, A., Davoren, M. & Byrne, H. J. Mechanistic studies of in vitro cytotoxicity of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers in mammalian cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 248, 259–268 (2010).

Naha, P. C., Davoren, M., Lyng, F. M. & Byrne, H. J. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced cytokine production and cytotoxicity of PAMAM dendrimers in J774A.1 cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 246, 91–99 (2010).

Albertazzi, L., Gherardini, L., Brondi, M., Sulis Sato, S., Bifone, A., Pizzorusso, T. & Bardi, G. In vivo distribution and toxicity of PAMAM dendrimers in the central nervous system depend on their surface chemistry. Mol. Pharm. 10, 249–260 (2013).

Duncan, R. & Izzo, L. Dendrimer biocompatibility and toxicity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 57, 2215–2237 (2005).

Murphy, M. P. & Smith, R. A. Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 629–656 (2007).

Ross, M. F. et al. Lipophilic triphenylphosphonium cations as tools in mitochondrial bioenergetics and free radical biology. Biochem. Mosc. 70, 222–230 (2005).

Murphy, M. P. Targeting lipophilic cations to mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1028–1031 (2008).

Li, N. et al. Inhibition of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced oral carcinogenesis in hamsters by tea and curcumin. Carcinogenesis 23, 1307–1313 (2002).

Aggarwal, B. B., Kumar, A. & Bharti, A. C. Anticancer potential of curcumin: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 23, 363–398 (2003).

Ravindran, J., Prasad, S. & Aggarwal, B. B. Curcumin and cancer cells: how many ways can curry kill tumor cells selectively?. AAPS J. 11, 495–510 (2009).

Sarkar, H. F., Li, Y., Wang, Z. & Padhye, S. Lesson learned from nature for the development of novel anti-cancer agents: implication of isoflavone, curcumin, and their synthetic analogs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 1801–1812 (2010).

Anand, P., Sundaram, C., Jhurani, S., Kunnumakkara, A. B. & Aggarwal, B. B. Curcumin and cancer: an “old-age” disease with an “age-old” solution. Cancer Lett. 267, 133–164 (2008).

Hatcher, H., Planalp, R., Cho, J., Torti, F. M. & Torti, S. V. Curcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trials. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 1631–1652 (2008).

Wang, M. et al. Curcumin induced HepG2 cell apoptosis-associated mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular free Ca2+ concentration. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 650, 41–47 (2011).

Zhou, Q. M. et al. Curcumin reduces mitomycin C resistance in breast cancer stem cells by regulating Bcl-2 family-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Cell Int. 17, 84 (2017).

Jayakumar, S. et al. Mitochondrial targeted curcumin exhibits anticancer effects through disruption of mitochondrial redox and modulation of TrxR2 activity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 113, 530–538 (2017).

Bansal, A. & Simon, M. C. Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. J. Cell Biol. 217, 2291–2298 (2018).

Cazanave, S. et al. High hepatic glutathione stores alleviate Fas-induced apoptosis in mice. J. Hepatol. 46, 858–868 (2007).

Tormos, C. et al. Role of glutathione in the induction of apoptosis and c-fos and c-jun mRNAs by oxidative stress in tumor cells. Cancer Lett. 208, 103–113 (2004).

Larasati, Y. A. et al. Curcumin targets multiple enzymes involved in the ROS metabolic pathway to suppress tumor cell growth. Sci. Rep. 8, 2039 (2018).

Shehzad, A. & Lee, Y. S. Molecular mechanisms of curcumin action: signal transduction. BioFactors 39, 27–36 (2013).

Ramachandran, C. & You, W. Differential sensitivity of human mammary epithelial and breast carcinoma cell lines to curcumin. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 54, 269–278 (1999).

Jiang, M. C., Yang-Yen, H. F., Yen, J. J. Y. & Lin, J. K. Curcumin induces apoptosis in immortalized NIH 3T3 and malignant cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 102, 45–54 (1996).

Syng-Ai, C., Kumari, A. L. & Khar, A. Effect of curcumin on normal and tumor cells: role of glutathione and bcl-2. Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 1101–1108 (2004).

Everett, P. C., Meyers, J. A., Makkinje, A., Rabbi, M. & Lerner, A. Preclinical assessment of curcumin as a potential therapy for B-CLL. Am. J. Hematol. 82, 23–30 (2007).

Choudhuri, T., Pal, S., Das, T. & Sa, G. Curcumin selectively induces apoptosis in deregulated cyclin D1-expressed cells at G2 phase of cell cycle in a p53-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20059–20068 (2005).

Kunwar, A. et al. Quantitative cellular uptake, localization and cytotoxicity of curcumin in normal and tumor cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 673–679 (2008).

Liu, E. et al. Curcumin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in a p53-dependent manner and upregulates ING4 expression in human glioma. J. Neurooncol. 85, 263–270 (2007).

Erfani-Moghadam, V., Nomani, A., Zamani, M., Yazdani, Y., Najafi, F. & Sadeghizadeh, M. A novel diblock of copolymer of (monomethoxy poly[ethylene glycol]-oleate) with a small hydrophobic fraction to make stable micelles/polymersomes for curcumin delivery to cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 5541–5554 (2014).

Li, S., Zhang, L., Li, S., Zhao, H. & Chen, Y. Curcumin suppresses the progression of gastric cancer by regulating circ_0056618/miR-194-5p axis. Open Life Sci. 16, 937–949 (2021).

Xiang, L. et al. Antitumor effects of curcumin on the proliferation, migration and apoptosis of human colorectal carcinoma HCT 116 cells. Oncol. Rep. 44, 1997–2008 (2020).

Zamzami, N. et al. Reduction in mitochondrial potential constitutes an early irreversible step of programmed lymphocyte death in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 181, 1661–1672 (1995).

Vander Heiden, M. G., Chandel, N. S., Schumacker, P. T. & Thompson, C. B. Bcl-xL prevents cell death following growth factor withdrawal by facilitating mitochondrial ATP/ADP exchange. Mol. Cell 3, 159–167 (1999).

Bossy-Wetzel, E., Newmeyer, D. D. & Green, D. R. Mitochondrial cytochrome c release in apoptosis occurs upstream of DEVD-specific caspase activation and independently of mitochondrial transmembrane depolarization. EMBO J. 17, 37–49 (1998).

Waterhouse, N. J. et al. Cytochrome c maintains mitochondrial transmembrane potential and ATP generation after outer mitochondrial membrane permeabilization during the apoptotic process. J. Cell Biol. 153, 319–328 (2001).

Montazeri, M. et al. Dendrosomal curcumin nanoformulation modulate apoptosis-related genes and protein expression in hepatocarcinoma cell lines. Int. J. Pharm. 509, 244–254 (2016).

Liu, T. Y. et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis in gallbladder carcinoma cell line GBC-SD cells. Cancer Cell Int. 13, 64 (2013).

Sullivan, K. D., Galbraith, M. D., Andrysik, Z. & Espinosa, J. M. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by p53. Cell Death Differ. 25, 133–143 (2018).

Basu, A. & Haldar, S. The relationship between BcI2, Bax and p53: consequences for cell cycle progression and cell death. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 4, 1099–1109 (1998).

Chaudhary, L. R. & Hruska, K. A. Inhibition of cell survival signal protein kinase B/Akt by curcumin in human prostate cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 89, 1–5 (2003).

Choudhuri, T., Pal, S., Agwarwal, M. L., Das, T. & Sa, G. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells through p53-dependent Bax induction. FEBS Lett. 512, 334–340 (2002).

Abbas, T. & Dutta, A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 400–414 (2009).

Tong, Q. S. et al. Downregulation of XIAP expression induces apoptosis and enhances chemotherapeutic sensitivity in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 12, 509–514 (2005).

Gottfried, Y., Rotem, A., Lotan, R., Steller, H. & Larisch, S. The mitochondrial ARTS protein promotes apoptosis through targeting XIAP. EMBO J. 23, 1627–1635 (2004).

Fong, W. G. et al. Expression and genetic analysis of XIAP-associated factor 1 (XAF1) in cancer cell lines. Genomics 70, 113–122 (2000).

Gupta, S., Ghosh, S., Gupta, S. & Sakhuja, P. Effect of curcumin on the expression of p53, transforming growth factor-β, and inducible nitric oxide synthase in oral submucous fibrosis: a pilot study. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 8, e12252 (2017).

Hallman, K., Aleck, K., Dwyer, B., Lloyd, V., Quigley, M., Sitto, N. & Dinda, S. The effects of turmeric (curcumin) on tumor suppressor protein (p53) and estrogen receptor (ERα) in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 153–161 (2017).

Jee, S. H., Shen, S. C., Kuo, M. L., Tseng, C. R. & Chiu, H. C. Curcumin induces a p53-dependent apoptosis in human basal cell carcinoma cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 111, 656–661 (1998).