Abstract

This paper proposes a novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm, termed Kangaroo Escape Optimization (KEO) for accurate parameter extraction of photovoltaic (PV) models including the single-diode, double-diode, and triple-diode configurations. The algorithm simulates the survival-driven escape behavior of Kangaroos in uncertain environments, where each Kangaroo represents a candidate solution and its movement embodies the search for a safer zone, i.e., a better objective value. The suggested KEO incorporates a dual-phase exploration mechanism of zigzag motion and long-jump escape to diversify the search, governed by a chaotic logistic energy adaptation strategy. In the exploitation phase, Kangaroos adaptively choose either a random group member or the best among a nearby subset to guide local search, while a decoy drop mechanism refines convergence without premature stagnation. The switching between exploration and exploitation is regulated by a probabilistic model that ensures dynamic adaptability throughout iterations. The proposed KEO is assessed against state-of-the-art optimizers using the CEC 2022 benchmarks suite. Also, the study incorporates a comprehensive Confidence Interval (CI) analysis to assess robustness and conducts a sensitivity study on hyperparameters. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the proposed KEO approach is assessed using real-world current–voltage (I–V) datasets obtained from two benchmark PV modules: RTC France and Photowatt-PWP-201 PV modules. A detailed comparative study reveals that the KEO delivers superior performance relative to several optimization algorithms previously utilized for PV parameter identification. Specifically, KEO exhibits enhanced accuracy, robustness, and convergence efficiency when estimating the electrical parameters of solar cells across different equivalent circuit models. Moreover, the proposed KEO demonstrates significant performance under diverse irradiance and temperature conditions. The findings confirm KEO’s capacity to reliably capture the complex nonlinear dynamics inherent in PV systems, positioning it as a versatile and powerful optimization tool for a broad range of renewable energy modeling tasks. The source code of THRO is publicly available at https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/181949-a-novel-kangaroo-escape-optimizer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing global demand for renewable energy has brought PV technology to the forefront of sustainable power generation. The accurate modeling of PV cells and modules is critical for the design, simulation, and optimization of solar energy systems1. PV devices serve as the foundational technology for converting solar radiation into usable electrical power, with their performance largely governed by the intrinsic properties of the semiconductor materials employed. Among the various materials explored, silicon continues to dominate the PV industry and is typically manufactured in three primary forms: monocrystalline, polycrystalline (multicrystalline), and amorphous silicon, each offering distinct structural and efficiency characteristics2. It is essential for optimizing energy yield, improving system reliability, and facilitating advanced control strategies in real-world solar applications. Central to this modeling process is the precise estimation of the electrical parameters that characterize the PV cell’s equivalent circuit3,4. It involves identifying key electrical characteristics such as diode saturation currents, ideality factors, series and shunt resistances, and photocurrent. These parameters directly influence the accuracy of the I–V and P–V curve simulations and are crucial for tasks such as MPPT, fault diagnosis, and performance prediction5,6.

Literature review

The electrical behavior of PV cells is commonly modeled using equivalent circuit representations, which aim to replicate the nonlinear characteristics observed in real-world PV devices. Among the most widely used models are the one-DM7, two-DM8, three-DM9, and a recently introduced Four-DM10, each offering progressively higher levels of fidelity by incorporating additional diode branches in parallel. These circuit-based models are instrumental in accurately simulating the I–V relationship, which is vital for assessing performance and enabling efficient power conversion. The inclusion of additional diode elements enhances the model’s ability to capture complex physical phenomena such as recombination losses, diffusion currents, and junction leakage effects. However, this increase in modeling detail comes at the cost of significantly elevated computational complexity. This is largely due to the greater number of unknown parameters, intricate interdependence among circuit elements, and the strong nonlinearity introduced by exponential terms in the governing equations. These challenges result in highly implicit and coupled mathematical formulations, making the accurate identification and solution of PV parameters a computationally intensive and numerically unstable problem, particularly in dynamic or real-time energy management environments.

A wide array of techniques has been proposed in the literature for estimating the parameters of PV models, which can generally be classified into three overarching categories: deterministic techniques11,12, non-deterministic methods13, and hybrid methodologies that integrate aspects of both paradigms14,15. Deterministic approaches are characterized by their ability to generate consistent and repeatable outcomes when provided with the same initial conditions. These methods are typically divided into two subcategories: analytical techniques and numerical procedures. A notable example of an analytical method is presented by Jie Xu, who introduced a strategy for extracting optimal parameter values of the one-DM. This approach utilized data obtained from PV manufacturer datasheets and employed a nonlinear least-squares fitting algorithm to fine-tune the model parameters effectively16. The results underscored the method’s precision and reliability in estimating PV characteristics. In contrast, other deterministic strategies rely more heavily on iterative numerical processes. For instance, the study in17 applied the dichotomy method, a root-finding algorithm, to solve the set of nonlinear equations governing PV behavior. Although this technique involves successive iterations, it ultimately converges on approximate parameter values rather than exact solutions, illustrating a trade-off between computational complexity and estimation accuracy.

Among the most prominent and extensively studied metaheuristic optimization techniques is the DE algorithm18,19. Over time, DE has seen numerous improvements aimed at enhancing its effectiveness in determining PV model parameters20. One such advancement is the DPDE algorithm21, which introduces a novel mechanism for global search enhancement by leveraging directional information derived from differential vectors within the population. This strategic use of directional guidance allows DPDE to better navigate the solution space, significantly reducing the likelihood of becoming trapped in local optima and thereby improving the algorithm’s robustness in parameter estimation tasks.

In22,23, Jaya algorithm-based on victory concept to reflect its core philosophy of iteratively refining solutions to achieve optimal outcomes. It has been effectively employed in the extraction of PV model parameters. Building upon the foundational Jaya framework, the DIWJAYA algorithm presents an additional refinement by integrating an individual weighting factor, utilizing the average performance of the current population, and incorporating a Gaussian mutation mechanism24. These enhancements collectively contribute to increased adaptability and computational efficiency, making DIWJAYA a more robust and effective tool for precise PV parameter identification. Another important advancement of this technique is the improved Jaya algorithm25, which introduces specific modifications aimed at enhancing convergence speed and improving estimation accuracy during the optimization process.

As highlighted in26, a wide range of algorithms have adapted and enhanced the PSO framework to improve both the precision and efficiency of PV parameter estimation. One such innovative method is the OLMIP, introduced in27, which is specifically designed to tackle the challenges associated with multimodal optimization and parameter identification in PV models. OLMIP mitigates the risk of premature convergence by initializing four diverse populations. These are later merged into a single elite population, facilitating robust exploration of the search space and reducing the likelihood of being trapped in local optima.

Although an exhaustive review of all metaheuristic techniques used in PV parameter extraction is beyond the scope of a single discussion, several advanced algorithms stand out due to their demonstrated effectiveness. Notable examples include the super-evolutionary mechanism and the Nelder-Mead simplex-enhanced Salp swarm algorithm28, which enhance convergence speed and accuracy. Additionally, the material generation optimizer29, Gazelle–Nelder–Mead optimization algorithm30, and the hybrid Sparrow search–exponential distribution optimization method31 have shown promise in optimizing PV models. Further contributions to the field include the Leader-based artificial Ecosystem approach32, artificial Rabbits algorithm33, and the heat transfer search algorithm34, each offering unique evolutionary strategies. Moreover, deep neural networks35 have been employed for data-driven PV parameter estimation, providing high accuracy under varying conditions. Finally, the Chaos-Inspired Invasive Weed Optimization algorithm36 has demonstrated robust performance by combining stochastic processes with adaptive behavior, making it suitable for complex PV modeling scenarios.

PV parameter estimation versus MPPT

Solar PV parameter estimation relies on accurately identifying intrinsic electrical parameters from experimental I-V data, using equivalent circuits to simulate and predict cell/module behavior under standard conditions, without emphasizing real-time tracking or control dynamics. In contrast, the MPPT problem in PV systems involves optimizing algorithms and control strategies to dynamically maximize energy extraction from solar panels37 under varying environmental conditions, such as changes in solar irradiance, temperature, and PSCs. While MPPT relies on these models for operational guidance, parameter estimation is crucial for system design and performance prediction, often employing optimization methods like least squares or metaheuristics but not for instantaneous power maximization. Nowadays, several metaheuristic optimization algorithms have been developed to locate the GMPP under PSC. PSO has been utilized in38 to optimize duty cycles in DC-DC converters. It presented an adaptive PSO to improve battery charging efficiency by adjusting inertia weights and reinitialization, despite the potential trapping of standard PSO in local optima. Therefore, the PSO has been hybridized with SSA that modeled salp chain foraging for optimization to enhance MPPT for optimal PV systems under uniform and PSC39. Hybrid SSA-PSO with direct sliding-mode control extracts GMPP while regulating DC-bus voltage40. Also, GWO has been upgraded and applied for GMPP tracking41. In this upgraded variant, an adaptive prey-movement has been incorporated for balanced exploration-exploitation, achieving great efficiency under standard conditions and PSC incorporating battery storage systems. Added to that, Modified multi-stepped constant current GWO variants have been investigated to further reduce oscillations42. Moreover, AO, emulating the eagle hunting strategies, has been performed for fast GMPP tracking under PSC43 and implemented via real-time Raspberry Pi framework. These hybrids help in mitigating slow convergence in standard optimization methods and local trapping to improve efficiency under dynamic conditions.

Motivation of the study

Suggesting new optimization algorithms is crucial in advancing engineering and computational fields, as they address increasingly complex real-world challenges that traditional methods often fail to handle efficiently, such as constrained problems, large-scale scenarios, and adaptive systems. Several metaheuristic approaches were efficiently applied to optimize PID control in high-speed rail platform door systems44, handle electric vehicle stations allocation in electrical feeders45, tackle large-scale traveling salesman problems46, communication systems with intelligent reflecting surface placements47,48, and provide a framework for constrained engineering optimization49. Otherwise, recent advancements in metaheuristic algorithms, particularly APSOLF, SAPSO, IGTA, MGBO, and SPAPSOLF, have shown promising results in enhancing power system performance. In50,51, APSOLF has been presented integrating random walk patterns via Lévy flight with adaptive PSO. In50, it was designed to optimize the parameters of a SSSC to minimize real and reactive power losses. In51, it was further applied to optimize SSSC parameters, MPPT, and firing angle in a PV-interfaced SSSC system. Also, SAPSO was introduced in52 to enhance the traditional PSO by incorporating self-adaptive mechanisms to dynamically adjust inertia weight and acceleration coefficients. In this work, SAPSO was employed to optimize the operation of a PV-interfaced inverter. Additionally, IGTA was suggested for allocation of the TCSCs in power grids53, enhancing grid stability and power transfer capability. In this IGTA, the standard gorilla troops algorithm has been enhanced by adding fitness-based crossover and tangent flight strategies. To further refine TCSC allocation, an MGBO has been performed54. In this variant, crossover operator was incorporated into the standard gradient-based optimizer to facilitate the exchange of TCSC configurations between solutions, contributing to solution diversity. Moreover, SPAPSOLF was proposed in55 combining the SAPSO features with Lévy flight’s random jumps and performed to optimize SSSC in power systems, focusing on enhancing system loadability.

These innovations not only boost accuracy and speed but also inspire interdisciplinary applications, driving progress in sustainable and intelligent systems. This study introduces a novel bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm called the KEO, developed by mimicking the real-life escape behaviors of Kangaroos in natural environments. The algorithm features adaptive decision-making mechanisms based on energy-driven movement, chaotic dynamics, and switching strategies between long jumps and zigzag patterns, combined with selective local search through safer area exploration and decoy drop behaviors. KEO is applied to solve the parameter estimation problem in PV models, which is characterized by strong nonlinearity, multiple local optima, and complex interdependencies among unknown parameters. Specifically, the algorithm is employed to extract the electrical parameters of single-diode, double-diode, and triple-diode equivalent circuit models using real experimental I–V data from benchmark PV modules. The objective is to minimize the error between simulated and measured curves, thereby improving the accuracy of PV modeling for diagnostics, control, and energy forecasting purposes.

Paper contributions

The key contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

-

Proposal of the KEO: A novel metaheuristic is developed to simulate Kangaroo survival behavior through dynamic switching between explorative and exploitative movements, guided by an adaptive chaotic energy model.

-

Integration of decoy drop and safer area selection: The introduction of biologically inspired control mechanisms is being implemented to improve local search precision and prevent premature convergence.

-

Comparative performance analysis: Benchmarking against state-of-the-art optimization algorithms, with results confirming that KEO outperforms existing methods in terms of accuracy, stability, and convergence speed.

-

Application to PV parameter extraction: The deployment of KEO is being implemented for precise parameter identification in single, double, and triple diode models under realistic operational conditions.

-

Validation on real-world data: Evaluation using experimental datasets from RTC France and Photowatt-PWP-201 PV modules, demonstrating the algorithm’s capability to model nonlinear PV behavior.

Parameters extraction of PV systems: problem formulation

This section presents the mathematical representation of solar PV cells and outlines an optimization framework for identifying unknown model parameters. While the Shockley diode-based equivalent circuit is commonly used to model solar cells, real-world deviations from ideal conditions can impact the accuracy of this representation. To achieve precise modeling, it is essential to account for non-ideal characteristics considering the effects of series (Rs) and shunt (Rsh) resistances along with complex conduction mechanisms.

One-DM

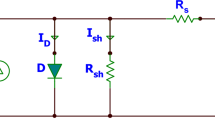

A solar cell exposed to sunlight can be modeled using an equivalent circuit comprising one diode, a photocurrent source, and two resistances. The photocurrent (Ip), generated by solar irradiance and temperature, serves as the main current source. The diode (D1) in the model is characterized by an ideality factor (α1), which adjusts for deviations from ideal diode behavior due to complex conduction mechanisms.

The equivalent circuit of the one-DM is shown in Fig. 1. According to Kirchhoff’s Current Law Concept (KCLC), the output current of the solar cell can be expressed as a function of output voltage (Vo), and the reverse saturation current (IR₁) as described in Eq. (1)56. Additionally, the thermal voltage (Thv) of the cell is derived using cell temperature (T) and Boltzmann’s constant (k = 1.3806503 × 10⁻²³ J/K). The Shockley diode equation incorporates the elementary charge (q = 1.60217646 × 10⁻¹⁹ C) to quantify electron charge.

In solar PV cells, five unknown parameters (X= [Ip, Rs, α1, IR1, Rsh]) in Eq. (1) need to be accurately identified depending on the measured I-V characteristics. The correct estimation of these parameters plays a crucial role in determining the overall performance of the solar cell. For example, when these parameters are precisely chosen, the one-DM can effectively predict the cell’s maximum power conversion efficiency.

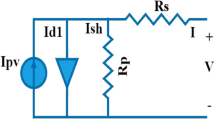

Two-DM

The equivalent circuit of the two-DM is illustrated in Fig. 2. In this configuration, diode D1 represents the diffusion of minority charge carriers, while diode D2 accounts for carrier recombination within the space-charge region of the p-n junction. The corresponding diffusion and recombination currents are denoted by IR1 and IR2, respectively. By applying KCLC to this model, the parameters α2 and IR2 represent the ideality factor and reverse saturation current associated with diode D2.

In this model, seven unknown parameters (X= [Ip, Rs, α1, IR1, α2, IR2, Rsh]) in Eq. (3) need to be accurately identified depending on the measured I-V characteristics.

Three-DM

The three-DM’s equivalent circuit design is displayed in Fig. 3 where a third. diode (D3) is added in parallel to previous two diodes. Applying KCLC to this model allows the derivation of it’s I-V characteristics and yields to Eq. (4). In this context, the parameters α3 and IR3 represent the ideality factor and reverse saturation current associated with diode D3.

In this model, nine unknown parameters (X= [Ip, Rs, α1, IR1, α2, IR2, α3, IR3, Rsh]) in Eq. (4) need to be accurately identified.

PV modules handling

The mathematical formulations for the one, two and three-DMs are presented based on a PV module configuration comprising Ns series-connected cells and Np.a. parallel-connected cells. These equations have been refined and adapted to yield the final expressions shown in Eqs. (5)–(7).

The proposed KEO optimization technique is employed to estimate variables that are not considered in the PV cell or module for one, two, and three-DMs.

Objective model

In this study, the statistical evaluation centers on the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), which is calculated using the equation provided in57:

In this context, MP denotes the total number of measured points, while the measured current and voltage are represented accordingly by\(I_{{\exp n}}^{L}\) and \(V_{{\exp n}}^{L}\) characterize. The variable x refers to a candidate solution within the search space, encompassing the estimated PV model parameters.

A novel KEO: concept, algorithmic steps, and mathematical formulation

This study presents a novel KEO, as a bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm that simulates the intelligent evasion strategies of Kangaroos in the wild. Inspired by their sudden decoy tactics, zig-zag escape routes, group dynamics, and chaotic behavioral elements, KEO aims to solve global optimization problems with improved convergence and robustness. The proposed KEO algorithm derives different features mimicking the Kangaroos’ real-world survival tactics. These include:

-

Sudden zigzagging maneuvers when pursued by predators,

-

Long-distance leaps to escape immediate danger,

-

Tendency to seek out safer areas (e.g., higher ground or denser vegetation),

-

Use of decoy behaviors (e.g., diverting movement to distract threats),

-

Energy-based decision-making, where exhausted Kangaroos switch from escape to safe exploration.

Each of these behaviors maps directly to a mathematical operator in the algorithm.

Step 1: initialization

At the beginning, a group of Kangaroos is randomly scattered across a landscape, representing an initial sampling of potential survival positions. Each Kangaroo position (Xi) is a vector in a D-dimensional decision space. The initial population of N Kangaroos is randomly generated as follows:

where, Low and Up represent the considered bounds of the D-dimensional decision variables. Then, the fitness value f(Xi) is computed for each one, simulating how suitable each position is in terms of food availability and predator avoidance.

Step 2: energy adaptation using chaotic logistic map

A Kangaroo’s behavior depends on its energy, which is not constant, and it’s influenced by internal biological rhythms and external pressure due to repeated attacks. The proposed KEO models this using a chaotic logistic map, mirroring the unpredictability in natural energy variation. In this regard, a chaotic sequence λ(t) is generated and updated in each iteration (t) using the Logistic Map as follows:

Therefore, at iteration t, the energy level of each Kangaroo Energyi(t) is determined by:

where r1 is a random scaling factor, tmax is the maximum number of iterations.

Based on this model, high energy is assigned at early iterations where Kangaroo is energetic and more likely to perform rapid escape maneuvers. On the other hand, low energy is assigned at later iterations where Kangaroo behaves more cautiously and focuses on finding stable safe zones.

Kangaroos must choose between fleeing from threats or carefully scouting better positions when energy is limited. Within the framework of the algorithm, this behavior is modeled by assigning a 50% probability to the action of escape—representing exploration of the wider environment in search of better opportunities. Conversely, it exploits the known landscape by searching for safer areas.

Step 3A: escape phase—zigzag and long jump strategies

Zigzag escape

When chased, Kangaroos do not move linearly; they zigzag to confuse predators. This unpredictable change in direction increases their survival chances. In this model, a rotated vector Vrot is defined by applying a random angular transformation:

where θ is a small random angle generated by:

where θmax is the maximum permissible movement angle (θmax is 30o) and r2 is random number. Also, U is an orthogonal unit vector, and Vi is the direction vector to the global best (XBest) which can be defined as:

Therefore, the new position of the Kangaroo can be updated as follows:

where, β indicates the zigzag step scale (β = 50%); \({\mathbb{N}}\left( {1,D} \right)\) refers to a D-dimensional random vector following Gaussian distribution; ∘ denotes element-wise multiplication.

Long jump escape

A powerful leap allows Kangaroos to escape large distances from threats or environmental hazards. Therefore, in this model, the update is non-directional and based on a scaled Gaussian noise as follows:

where, LJEi simulates the long jump escape component of each Kangaroo (i) which is modeled as follows:

where, Decoydrop indicates the decoy drop movement of the Kangaroo. This jump enables searching vastly different parts of the space to escape poor-quality areas (local optima).

Energy-based strategy switch

Each kangaroo within the algorithm is designed to make adaptive decisions regarding its movement strategy, selecting between two distinct behavioral patterns. These patterns are the zigzag escape approach described in Eq. (15), and the long jump maneuver detailed in Eq. (16). The designed strategic selection is not static; rather, it is governed by the Kangaroo’s current energy level, denoted as (Energyi(t)), which evolves throughout the optimization process. The proposed KEO introduces a probabilistic threshold mechanism whereby the Kangaroo assesses its energy in relation to a predefined benchmark threshold, referred to as (Energythreshold), which is set at 50%.

When the energy level of Kangaroo (i) falls below this threshold, typically observed in the early stages of iteration, it prefers the zigzag escape tactic. Conversely, when the energy level surpasses this threshold which is commonly occurring during the middle phases of the optimization, the Kangaroo is more likely to engage in long jump behavior, which represents more aggressive, wide-ranging exploration movements aimed at discovering promising distant regions in the solution space. This adaptive transition mechanism allows the algorithm to balance exploration and exploitation effectively by dynamically modifying its movement strategy according to the individual agent’s energy profile over time.

Step 3B: searching for safer areas with decoy drop

When not under immediate threat, Kangaroos search for safer places with cover or resources. They may also drop decoys via fake movement patterns to mislead threats and protect others. In the designed KEO, each Kangaroo decides how to identify a better area. The first decision is implemented via explorative mode where a random Kangaroo’s position is chosen as safer place (XSafe). The second is implemented via exploitative mode where a group of Kangaroos is formed and the one with the best fitness is chosen as the safest area (XSafe). The third one is implemented via deep exploitative mode where the one with the overall best fitness is chosen as the safest area (XSafe). This updating mechanism is implemented to update the new position of the Kangaroo as follows:

This ensures partial updates, resembling how Kangaroos subtly adjust their path while staying under cover. The decoy mechanism introduces diversity and helps avoid premature convergence. This strategy in the KEO is inspired by the biological defense behavior of Kangaroos as this mechanism reflects how Kangaroos drop decoys via misleading tracks, diversionary movements, or kicking sand when threatened by predators, allowing them to escape toward a safer or better area. In this strategy, the decoy drop is mathematically modeled as follows:

As shown in this equation, decoy drop controls the information flow, limiting or enabling update in different dimensions. It acts like a binary gate. Table 1 displays the three possible ways created by the decoy drop. As shown, the Kangaroo may make a full redirection or a complete misleading action, such as bounding away in an entirely different direction. In the second case, the Kangaroo may throw off tracks or twist part of its motion, misleading partially. Finally, a minimal but effective decoy, resembling a feint or a quick foot shift may do to confuse the predator.

The decoy drop mechanism (Table 1) introduces a binary gate that probabilistically masks certain dimensions of the Kangaroo’s position vector during updates (Eq. 19). The binary gate selectively deactivates dimensions by assigning zero-weight updates, while others remain active. This selective masking has two main effects. First, it maintains diversity where the KEO prevents all agents from moving simultaneously in the same search direction by randomly freezing some dimensions. This reduces the chance of the entire population collapsing prematurely around a local optimum. Second, it supports controlled exploration–exploitation balance as the binary gate acts as a dimension-wise exploration filter. Early iterations update more dimensions, promoting exploration, while later stages use sparse masking to fine-tune exploitation around promising solutions.

Step 5: boundary control and memory update

Kangaroos naturally do not leave their habitat bounds. They remain within a feasible territory that offers survival opportunities. Therefore, the new position of Kangaroos is checked as follows:

Therefore, the new fitness value f(Xnewi) is computed for each one. Only successful behaviors are retained over time. Kangaroos learn from their best experiences and discard worse decisions as follows:

Also, the global best is updated in each iteration. The process (Steps 2–5) is repeated until a maximum number of iterations is reached. These steps can be summarized and graphically illustrated in the flowchart in Fig. 4.

Simulation results

This section is organized into two main parts. The first part focuses on benchmarking the performance of the proposed KEO against several recent metaheuristic algorithms, as well as the well-established DE and PSO algorithms. The assessment is performed on a varied array of test functions, encompassing unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions, to thoroughly evaluate KEO’s resilience and flexibility across multiple optimisation environments. The second part provides an in-depth assessment of KEO for PV parameter estimation, using experimental data from two well-known benchmark modules: the R.T.C. France cell and the Photowatt-PWP-201 module. To further demonstrate the practical applicability of KEO, its performance is further tested on the Kyocera KC200GT PV module under different temperatures and irradiance levels utilizing the three-DM.

Simulation results for benchmarks

Performance comparison of KEO with benchmark algorithms

In order to validate the proposed KEO against other algorithms, a further test is conducted on several unimodal, multi-modal, Hybrid Function, and Composition Function benchmarks. In this regard, the CEC 2022 functions are handled which have 12 benchmarks described in detail in Table 2. The performance of the proposed KEO is evaluated and compared with 5 recent optimization algorithms CFO (2025)58, MShOA (2025)59, WUTPO (2025)60, RIME algorithm (2023)61,62. WOA (2023)63, besides the well-known DE64 and PSO65 algorithms. Also, in order to clarify whether the chaotic logistic map introduces significant computational overhead, another version of energy decay is assessed via the following model:

Therefore, the test includes two versions of energy variation. The first one (KEO_Chaotic) indicates that energy level is varied through Chaotic logistic map defined in Eq. (11), while the second one (KEO_Energy_Decay) indicates that energy level is varied through linear decay defined in Eq. (22). A complete parameter setting of the compared algorithms are described in detail in Table 3. The nine compared algorithms are run 50 disparate runs and each run is started with similar initial population to ensure same statring points. Figure 5 (a-l) displays the boxplots for all twelve CEC 2022 benchmark while Table 4 (a-l) illustrates the regarding CI boundaries (CI_Lower and CI_Upper). Also, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test is implemented, and the individual and average rankings are tabulated in Table 5.

The comparative analysis using the CEC 2022 benchmark functions (Fn1–Fn12) highlights the strong adaptability of the KEO. Both KEO variants, KEO_Chaotic and KEO_Energy_Decay, consistently rank among the top performers across unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions. From Table 4, it is evident that the chaotic version frequently achieves very close-to-optimal mean values with tight confidence intervals, particularly in functions such as Fn1, Fn2, Fn3, Fn6, and Fn9. This suggests that the chaotic energy regulation mechanism enhances KEO’s exploration capacity, helping it escape local optima while maintaining convergence stability. The linear energy decay version also performs competitively, but in several cases (e.g., Fn6, Fn10, Fn11) the chaotic variant shows a significant edge, demonstrating the benefit of incorporating chaotic perturbation in dynamic search balance.

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test outcomes (Table 5) further reinforce these findings. KEO_Chaotic achieves the best overall ranking (AvgRank = 3.08, Rank 1), followed closely by KEO_Energy_Decay (AvgRank = 3.33, Rank 2). Traditional algorithms like DE and RIME show competitive behavior (Ranks 3 and 4), but swarm-based methods such as PSO, WOA, and MShOA generally lag behind, especially in high-dimensional or composite functions. CFO demonstrates strong performance in some cases (e.g., Fn1, Fn2) but lacks consistency across all benchmarks. However, the proposed KEO, particularly in its chaotic energy adaptation form, outperforms state-of-the-art metaheuristics in robustness, accuracy, and stability across various optimization landscapes.

Moreover, Table 6 records the computational time (s) of the KEO variants against other metaheuristics when solving the CEC 2022 benchmark functions (Fn1–Fn12). Both KEO with chaotic mapping and KEO with energy decay exhibit moderate runtimes across all functions. Their execution times fall between the fastest methods such as PSO and DE (e.g., Fn5: DE = 0.0209 s, PSO = 0.0389 s) and the slower ones such as MShOA (e.g., Fn1: 0.1847 s, Fn6: 0.1532 s). This shows that while KEO is not the fastest algorithm, its computational burden remains competitive and well within practical limits.

Sensitivity analysis of KEO hyperparameters on optimization performance

In order to explore the impact of KEO’s hyperparameters (energy threshold, zigzag scale factor β) on performance. A sensitivity analysis is implemented to assess their impact on mean objectives considering Fn3. The sensitivity analysis is presented in Fig. 6(a) and (b) by analyzing the variations of the energy threshold and the zigzag scale factor (β). Figure 6(a) indicates that the energy threshold has a noticeable but relatively small effect on the mean objective score. As the threshold increases from 0.15 to 1.0, the performance fluctuates slightly, with the lowest mean objective score obtained at threshold = 0.5 (600.4). In Fig. 6(b), the impact of the zigzag scale factor is examined under a fixed energy threshold (0.5). The performance shows greater variability, with the best mean objective score observed at β = 0.5 (600.39). Extremely small (0.15) or large (1.0) β values lead to degraded performance. Therefore, the results demonstrate that while both hyperparameters influence KEO’s efficiency, β plays a more decisive role in controlling convergence quality, with moderate values (EnergyThreshold = 0.5, β = 0.5) yielding the most effective outcomes.

Simulation results for PV cell/modules

This section presents a detailed evaluation of the proposed KEO applied to two benchmark PV cell/module: the R.T.C. France and the Photowatt-PWP-201. The first case focuses on the R.T.C. France cell, a commercial-grade silicon-based PV cell tested under standard irradiance conditions of 1000 W/m² and an operating temperature of 33 °C. Key electrical characteristics include an open-circuit voltage of 0.5727 V, a short-circuit current of 0.7605 A, and a maximum power point defined by a voltage of 0.4590 V and a current of 0.6755 A. The second case study investigates the Photowatt-PWP-201 module, which consists of 36 polycrystalline silicon cells connected in series66. The evaluation is conducted at an ambient temperature of 45 °C and under the same irradiance level of 1000 W/m², aligning with standard test benchmarks used in solar cell modeling studies. The upper and lower bounds for the electrical parameters to be optimized across the three DMs are summarized in Table 7, alongside the corresponding technical specifications for both PV modules. These bounds define the feasible search space for the parameter extraction process and ensure that the optimization remains physically meaningful and consistent with manufacturer data.

Applications of RTC France PV

For the RTC France PV cell, the proposed KEO is used to extract the five, seven, and nine unknown parameters regarding the three designed models. Table 8 presents the estimated parameter values for the One-DM, Two-DM, and Three-DM. For each model, KEO is employed to identify the unknown parameters that characterize the cell’s electrical behavior by minimizing the RMSE between the simulated and experimental I–V data. The photocurrent (Ip) values across the three models are remarkably stable, all converging near 0.76078 A. Similarly, the series resistance (Rs) values remain within a narrow band, indicating the optimizer’s robustness in determining ohmic losses. A modest increase is observed in the shunt resistance (Rsh) from One-DM to Two-DM, which slightly stabilizes in Three-DM, reflecting the improved modeling of leakage pathways as more diodes are added to the equivalent circuit. With regard to the reverse saturation currents (IR₁, IR₂, and IR₃) and ideality factors (α₁, α₂, and α₃), the KEO algorithm effectively adapts these parameters in accordance with each model’s physical structure. The estimated ideality factors lie within realistic physical limits and differ across models, affirming that KEO flexibly adjusts the diode characteristics based on the model’s internal architecture and the non-ideal conduction behavior being represented. The RMSE values demonstrate a progressive reduction from One-DM to Three-DM, with values of 9.8602E − 4, 9.8250E − 4, and 9.8249E − 4, respectively. Although the improvement from Two-DM to Three-DM is marginal, the trend confirms that incorporating additional diodes enhances the model’s capability to replicate real I–V behavior. However, this also implies diminishing returns in accuracy gains relative to increased computational complexity.

Also, Fig. 7 provided displays of the RMSE convergences obtained over 50 independent runs of the proposed KEO when applied to parameter estimation for three PV models. This performance evaluation reveals several insights regarding the algorithm’s accuracy, stability, and convergence consistency across model complexities. For the one-DM, the RMSE remains constant at approximately 0.000986022 across all 50 runs. This perfect repeatability indicates that the one-DM problem presents a relatively low-dimensional and less multimodal search space, which the KEO consistently solves with high precision. The fixed convergence value suggests that the global optimum in this case is easily reachable and that the search dynamics of the KEO are both stable and deterministic for this model configuration.

In contrast, the two-DM and three-DM introduce more complexity due to the additional nonlinear parameters. For the two-DM, the RMSE starts from 0.0009825 and gradually increases across runs, reaching a maximum of 0.000999922. A similar trend is observed for the three-DM, where the RMSE values range from 0.000982499 up to 0.000991502. Despite this slight variability, the proposed KEO algorithm still converges within a narrow performance band, demonstrating strong robustness even in higher-dimensional, more multimodal spaces. The lower-bound RMSE values in two-DM and three-DM are slightly lower than in one-DM, confirming that increasing model complexity enhances the ability to fit the I–V characteristics more accurately. However, this comes with a marginal cost in convergence variability due to the added search space dimensionality and parameter interdependencies.

These results confirm that the proposed KEO not only achieves accurate parameter estimation but also maintains stability and convergence efficiency across different PV model structures. The findings validate the suitability of KEO for practical solar energy applications that require high-fidelity modeling, such as performance prediction, system optimization, and real-time control.

Furthermore, Fig. 8 provided the histogram illustrates the distribution of RMSE values over 50 independent runs of the proposed KEO applied to three photovoltaic models. The horizontal axis represents the RMSE values, while the vertical axis indicates the number of occurrences of each RMSE range across the 50 trials. For the one-DM Model (Purple Bars), 100% of the RMSE values are concentrated around 9.86 × 10⁻⁴, as shown by the single tall bar reaching 50 occurrences. This perfect uniformity implies that KEO converges reliably and deterministically to the same solution for the One-DM across all runs. For the two-DM Model (Cyan Bars), a majority of the RMSE values (around 44%) lie close to 9.86 × 10⁻⁴, similar to One-DM. However, the remaining 56% are distributed across slightly higher RMSE bins, extending up to 9.99 × 10⁻⁴. For the three-DM Model (Yellow Bars), about 42% of the RMSE results fall in the 9.86 × 10⁻⁴ bin, while 58% are distributed across higher error ranges. The spread is similar to that of the two-DM Model, though slightly more dispersed, reflecting the higher dimensionality (9 parameters) and greater multimodality of the three-DM Model optimization landscape. Despite this, the RMSE values remain within a narrow band, indicating that KEO maintains a strong level of robustness and convergence accuracy, even in complex scenarios. Both Two-DM and Three-DM exhibit high accuracy with minor stochastic variation, reflecting KEO’s adaptability in solving more challenging problems. Across all models, RMSE values remain below 1.0 × 10⁻³, confirming the high fidelity of the parameter estimation process.

To shade the light on the performance effectiveness of the proposed KEO using the one-DM, Table 9 presents a detailed comparison of the proposed KEO against a wide range of existing optimization algorithms in terms of RMSE accuracy for parameter estimation of the RTC France cell. The included benchmark algorithms span various recent and classical techniques, such as the PGJAYA67, RIME68, CPMPSO69, EO70, EMPA70, GO71, MPA70, HEAP method70, BMA72, LAPO73, PSOGWO74, NLBMA75, MVO76, EHHO77, ALO78, JFS algorithm70, FPSO79, and HFPS80. The tabulated results highlight the effectiveness of KEO, which achieves an RMSE of 9.8602E − 4, outperforming most of the listed methods—some of which show errors an order of magnitude larger.

For performance comparison using the two-DM, the study further evaluates the performance of the proposed KEO. Table 10 compares the results obtained by KEO with those achieved by other advanced bio-inspired algorithms, including the DMO, MDMO, RIME, and its enhanced variant, MRIME. The table summarizes critical statistical indicators such as minimum, median, average, and worst RMSE values, as well as the standard deviation across 50 independent runs. Among all algorithms, KEO yields the lowest minimum RMSE of 9.8249E − 4, indicating its ability to consistently locate highly accurate parameter solutions. Moreover, KEO maintains the lowest standard deviation (2.17E − 6), reflecting excellent stability and minimal variance across repeated trials. Compared to MRIME and MDMO, KEO not only demonstrates slightly better minimum RMSE but also outperforms them in terms of consistency and convergence reliability.

Visual validation is provided in Fig. 9 (a) and (b), which show the close match between simulated and measured I–V and P–V characteristics for the three-DM. The high degree of overlap confirms that the parameters estimated by KEO yield realistic and physically consistent model behavior. Additionally, Fig. 10 displays the absolute errors in current and power predictions, which remain extremely low, ranging from 7.581E − 9 to 6.295E − 6 A for current and 2.011E − 6 to 1.432E − 3 W for power, demonstrating the method’s high fidelity in both energy and electrical current prediction. These findings emphasize that KEO is well-suited for solving complex optimization problems in PV modeling, maintaining both accuracy and computational reliability.

Applications for photo Watt-PWP 201 PV module

The results shown in Table 11 present the extracted electrical parameters for the Photo Watt-PWP 201 PV module using the proposed KEO across three modeling configurations: the one-DM, two-DM, and three-DM. Each configuration involves an increasing number of parameters, enabling more detailed modeling of the PV cell’s nonlinear characteristics.

Despite this growing complexity, the optimizer consistently returns highly similar parameter values across all three models, as well as an identical RMSE value of 2.425075E − 03. The photocurrent remains practically unchanged across all models, with a value around 1.03051 A. Also, the shunt and series resistances are also nearly identical across all configurations, indicating that the optimizer effectively converges to consistent and physically realistic estimates for resistive losses regardless of model complexity. Regarding the diode-related parameters, IR1 and α1 also exhibit high consistency across the three models. As more diodes are introduced in the two-DM and three-DM configurations, additional reverse saturation currents (IR2, IR3) and ideality factors (α2, α3) are estimated. These values fall within expected physical ranges: IR2decreases from 1.1E − 08 A in two-DM to 2.5E − 09 A in three-DM, while the corresponding ideality factors adjust slightly. In three-DM, IR3 is exceedingly small (1.27E − 13 A), suggesting that its contribution to the I–V characteristics may be minimal.

The RMSE values across all three models are identical (2.425075E − 03), indicating that increasing model complexity does not lead to any observable improvement in curve fitting accuracy for this particular PV module. This suggests that, for the Photo Watt-PWP 201 module, the one-DM may already be sufficient to capture the device’s electrical behavior, and that additional diodes only add redundant parameters without offering practical modeling benefits.

The marginal reduction in RMSE observed when transitioning from the two-diode to the three-diode model (Tables 8 and 11) indicates diminishing returns in terms of modeling accuracy. While the three-DM provides a slightly closer fit to the experimental I–V data, the improvement over the two-DM is minimal. However, this added accuracy comes at the expense of increased computational cost, as the three-DM involves two additional nonlinear parameters and a more complex optimization landscape. Therefore, the two-DM balances accuracy with computational efficiency, while the three-DM is more relevant for research or detailed diagnostics, balancing physical fidelity with efficiency.

The proposed KEO algorithm’s stability and convergence consistency were evaluated over 50 independent runs for parameter estimation in three PV models as shown in Fig. 11. The one-DM problem showed constant RMSE convergence, indicating high precision and a stable, deterministic search dynamics for the global optimum. The two-DM and three-DM models results in slightly higher RMSE values. Despite this, the proposed KEO algorithm converges within a narrow performance band, demonstrating robustness in high-dimensional, multimodal spaces. However, this increases convergence variability due to search space dimensionality and parameter interdependencies.

Furthermore, the histogram shows the distribution of RMSE values of over 50 independent runs of the proposed KEO applied to three photovoltaic models is displayed in Fig. 12. For the one-DM Model, 100% of RMSE values are concentrated around 2.425 × 10–3, indicating KEO converges reliably and deterministically. For the two-DM Model, 72% of RMSE values lie close to 2.425 × 10⁻3, while 28% are distributed across slightly higher bins. For the three-DM Model, 38% of RMSE results fall in the 2.5 × 10⁻3 bin, indicating KEO’s strong robustness and convergence accuracy.

Table 12 presents a comparative performance evaluation of the designed KEO against several recently reported optimization algorithms in extracting the electrical parameters for the one-DM of the Photo Watt-PWP 201 PV module. The competing methods include RAO optimizer82, PSO83, HFPS80, and FBIT84, with performance measured using minimum, average, and worst RMSE values over multiple trials. The proposed KEO demonstrates superior performance across all statistical indicators, achieving a minimum RMSE of 2.42507E − 3, which slightly outperforms even the best-performing competitor, FBIT. While other algorithms such as RAO and SMA85 approach comparable minimum RMSE levels, their average and worst RMSE values are significantly higher, suggesting that they lack consistency and robustness. For instance, RAO’s worst RMSE reaches 0.42554, while SMA’s extends to 1.0799E − 02, compared to KEO’s consistently low value of 2.42507E − 03 across all trials. This consistency reinforces KEO’s convergence reliability, making it a stable and accurate option for real-world PV parameter estimation using the One-DM framework.

Table 13 extends the comparative evaluation to the two-DM of the same PV module. The proposed KEO achieves the lowest minimum RMSE (2.42507E − 03), similar to FBIT but outperforming PSO and LAPO73. Its average RMSE is slightly higher than FBIT’s but within a narrow margin. KEO’s lower worst-case RMSE (2.56361E − 03) is more robust and stable than other algorithms, proving its reliability for modeling complex PV behavior in the two-Diode configuration.

Table 14 presents the performance results for the three-DM, which introduces the highest level of complexity among the tested configurations. KEO once again secures the lowest minimum RMSE (2.42508E − 3), outperforming advanced optimizers such as AEO86 (2.4800E − 3), FBIT (2.426E − 3), and SNS (2.5090E − 3). The average RMSE obtained by KEO is 2.51791E − 3, which is competitively lower than SNS (3.1910E − 3), and its worst RMSE is also significantly better at 2.66964E − 3, compared to 5.5110E − 3 for SNS. Other algorithms, such as BHCS87 and SSA, demonstrate substantially higher RMSE values, reinforcing that they are less effective under the high-dimensional and nonlinear optimization landscape posed by the Three-DM.

These results highlight KEO’s scalability and adaptability, maintaining high accuracy and convergence stability even as the number of unknown parameters increases. Such performance confirms KEO’s suitability for tackling complex PV modeling tasks that demand both precision and robustness.

Figure 13 (a) and (b) provide visual validation, demonstrating a close match between simulated and measured I–V and P–V characteristics for the three-DM, confirming that the parameters estimated by KEO yield realistic and physically consistent model behavior.

As shown in Fig. 14, the study reveals that KEO is highly accurate in predicting energy and electrical current, with absolute errors in current and power predictions being extremely low. This highlights its suitability for complex optimization problems in PV modeling, ensuring both accuracy and computational reliability.

CI assessment of KEO across different PV models

In this part, the CI of the proposed KEO at 95% probability for the R.T.C. France cell, and the PWP 201 polycrystalline PV moule. Figure 15 displays the boxplots with 95% CI while Table 15 illustrates the related CI boundaries (CI_Lower and CI_Upper) for the R.T.C. France cell, and the PWP 201 polycrystalline PV moule, respectively. For the One-DM, the mean (0.00098602) is fixed with zero CI width, again indicating no variability but limited flexibility. The Two-DM produces a slightly higher mean (0.00098691) with a modest CI ([0.00098474, 0.00098808]), showing stable performance with small variance. Also, the three-DM achieves a mean (0.00098585) that is very close to One-DM but with a slightly narrower CI ([0.0009852, 0.00098651]). The results for the PWP 201 polycrystalline module demonstrate that the KEO effectively adapts to increasing model complexity. The One-DM model shows a single fixed value (0.0024251) for the mean, CI_Lower and CI_Upper, indicating no variation. This reflects a very rigid fit that does not capture uncertainties. The Two-DM model yields a slightly higher mean performance (0.0024524) with a narrow confidence interval (CI = [0.0024408, 0.002464]). The Three-DM model achieves the highest mean (0.0025155) but with a wider CI ([0.002498, 0.002533]) and more spread in the boxplot.

Performance under irradiance and temperature variations using the three-DM

In this section, the KEO is applied to parameter extraction of the Kyocera KC200GT PV module, which consists of silicon solar cells with a diameter of 57 mm. The algorithm is tested against experimental data under varying irradiance and temperature conditions, enabling a detailed comparison between simulated and measured characteristics. The analysis focuses on the module’s electrical behavior when modeled using the three-DM. The experimental and simulated outcomes are presented in terms of the I–V and P–V curves. The proposed KEO is employed to reproduce 15 characteristic operating points covering a range of current and voltage values.

Figures 16 and 17 illustrate the I–V and P–V curves, respectively, obtained for an irradiance level of 1000 W/m² under three distinct operating temperatures (25 °C, 50 °C, and 75 °C). The plots reveal a clear reduction in both output voltage and power as the operating temperature increases, which aligns with the well-established negative temperature coefficient of PV modules. Figures 18 and 19 depict the I–V and P–V responses for a fixed temperature of 25 °C under five different irradiance levels (200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 W/m²). The results highlight the strong dependence of the output current and power on irradiance intensity. With rising irradiance, both current and power increase significantly, while voltage remains relatively stable, demonstrating the proportional relationship between irradiance and generated current. These findings demenstartes that the proposed KEO provides a reliable and accurate representation of the KC200GT module’s electrical characteristics across different environmental conditions.

Conclusions

This study introduced a novel metaheuristic algorithm, the KEO, inspired by the real-world escape mechanisms of Kangaroos, and applied it to the complex problem of parameter estimation in PV models. The algorithm integrates biologically motivated strategies—such as chaotic energy adaptation, zigzag and long-jump movements, decoy drop behavior, and selective safer-area exploration—to balance global exploration and local exploitation. This biologically grounded design equips KEO with strong adaptability in navigating high-dimensional and nonlinear search landscapes, such as those encountered in modeling the current–voltage characteristics of PV systems. To validate the efficacy of the proposed approach, benchmarking with the CEC 2022 test suite highlighted the competitive superiority of KEO against state-of-the-art algorithms across diverse optimization landscapes. Also, sensitivity analysis of its hyperparameters confirmed stable performance and provided practical guidelines for parameter tuning. Moreover, KEO was tested on two well-known commercial PV modules: RTC France and Photowatt-PWP 201, across three modeling frameworks, the one-DM, two-DM, and three-DM. Beyond the PV module case studies, the robustness of the proposed method was reinforced through 95% confidence interval assessments, ensuring statistical reliability of the obtained results. Its applicability under varying irradiance and temperature conditions further demonstrated resilience in real-world scenarios.

Benchmarking with the CEC 2022 test suite further highlighted KEO’s competitive edge, as the chaotic variant achieved the best overall ranking (AvgRank = 3.08) in the Wilcoxon signed-rank test across 12 functions, outperforming DE, PSO, and several recent metaheuristics. Additionally, computational time analysis showed that KEO maintained moderate runtimes (e.g., 0.061 s for Fn1 and 0.042 s for Fn5), ensuring practical applicability without excessive computational burden.

In terms of numerical outcomes for PV applications, the proposed KEO achieved remarkable accuracy across all tested models. For the R.T.C. France cell, the one-DM produced an RMSE as low as 9.86 × 10⁻⁴, while the two- and three-DMs yielded slightly improved values of 9.8250 × 10⁻⁴ and 9.8249 × 10⁻⁴, respectively, confirming the stability of KEO in handling increasing model complexity. For the Photowatt-PWP-201 module, the one-, two- and three-DM achieved similar RMSE of 2.425 × 10⁻³, indicating higher accuracy. Comprehensive comparisons against a diverse array of state-of-the-art and classical optimization techniques, such as PSO, RIME, SMA, LAPO, EMPA, HFPS, and others, revealed that KEO outperforms or matches the best-known methods in terms of minimum, average, and worst-case RMSE across all modeling scenarios. The proposed KEO exhibits superior accuracy and consistency in parameter estimation for both simple and complex PV models. Under varying irradiance and temperature conditions for the Kyocera KC200GT module, KEO accurately reproduced I–V and P–V characteristics across 15 operating points, demonstrating strong environmental robustness.

Future research may consider extending the KEO framework to address dynamic PV modeling under varying environmental conditions (e.g., partial shading, temperature fluctuations), integration with MPPT control schemes, or hybridizing it with surrogate modeling and deep learning for accelerated real-time applications. Additionally, implementation of the KEO against noisy or incomplete I-V data to assess its resilience to measurement uncertainties.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

Code availability

The code for all analyses reported in the manuscript is available on request.

Abbreviations

- ALO:

-

Ant lion optimization

- AO:

-

Aquila optimizer

- APSOLF:

-

Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization with Lévy Flight

- BHCS:

-

Biogeography-based heterogeneous cuckoo search

- BMA:

-

Barnacles mate optimization

- CFO:

-

Caterpillar fungus optimizer

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPMPSO:

-

Classified perturbation mutation PSO

- DE:

-

Differential evolution

- DIWJAYA:

-

JAYA driven by individual weights

- DM:

-

Diode model

- DMO:

-

Dwarf Mongoose Optimizer

- DPDE:

-

Directional Permutation Differential Evolution

- EHHO:

-

Enriched Harris Hawks Optimizer

- EMPA:

-

Enhanced Marine Predator Algorithm

- EO:

-

Equilibrium Optimization

- FBIT:

-

Forensic-based Investigate Technique

- FPSO:

-

Flexible Particle Swarm Optimization

- GMPP:

-

Global maximum power point

- GO:

-

Growth Optimization

- GWO:

-

Grey Wolf Optimization

- HFPS:

-

Hybrid Firefly and Pattern Search

- IGTA:

-

Improved Gorilla Troops Algorithm

- JFS:

-

Jellyfish Searching

- KEO:

-

Kangaroo Escape Optimization

- LAPO:

-

Lightning Attachment Procedure Optimizer

- MDMO:

-

Modified DMO

- MGBO:

-

Modified Gradient-Based Optimization

- MPA:

-

Marine Predator Algorithm

- MPPT:

-

Maximum power point tracking

- MRIME:

-

Modified RIME ()

- MShOA:

-

Mantis Shrimp Optimization Algorithm

- MVO:

-

Multi-verse Optimization

- NLBMA:

-

Neighborhood Laplace Barnacles Mate Optimization

- OLMIP:

-

Optimizer Leveraging Multiple Initial Populations

- PGJAYA:

-

Performance-Guide Jaya

- PSCs:

-

Partial shading conditions

- PSO:

-

Particle Swarm Optimization

- PSOGWO:

-

Hybridized PSO–GWO

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- SAPSO:

-

Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization

- SPAPSOLF:

-

Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization with Lévy Flight

- SSA:

-

Salp Swarm Algorithm

- SSSC:

-

Static Synchronous Series Compensator

- TCSC:

-

Thyristor-Controlled Series Capacitors

- WOA:

-

Walrus Optimization Algorithm

- WUTPO:

-

Water Uptake and Transport in Plants Optimizer

- I–V:

-

Current–voltage

- Rs and Rsh :

-

Series and shunt resistances

- Ip :

-

Photocurrent

- α 1, α 2 and α 3 :

-

Ideality factors of the three diodes, respectively

- V o :

-

Output voltage

- I R1, I R2 and I R3 :

-

Reverse saturation currents of the three diodes, respectively

- Th v :

-

Thermal voltage

- T :

-

Temperature

- k :

-

Boltzmann’s constant

- q :

-

Electron charge

- N s :

-

Series-connected cells

- N pa :

-

Parallel-connected cells

- MP :

-

Total number of measured points

- \({I}_{\mathit{exp}n}^{L}\) and \({V}_{\mathit{exp}n}^{L}\) :

-

Measured current and voltage

- X i :

-

EACH kangaroo position

- D :

-

Dimension of the problem

- N :

-

Population of kangaroos

- Low and Up :

-

Considered bounds of the D-dimensional decision variables

- f(X i):

-

Fitness value for each kangaroo position

- λ(t):

-

Chaotic sequence in each iteration (t)

- Energy i(t):

-

ENERGY level of each kangaroo at iteration t

- r 1, r 2 and r 3 :

-

Random scaling factors

- t max :

-

Maximum number of iterations

- θ :

-

A small random angle

- θ max :

-

Maximum permissible movement angle

- U :

-

Orthogonal unit vector

- V i :

-

Direction vector to the global best (XBest)

- Xnew i :

-

New position of each kangaroo (i)

- β :

-

Zigzag step scale

- \({\mathbb{N}}\left( {1,D} \right)\) :

-

D-dimensional random vector following Gaussian distribution

- ∘:

-

Element-wise multiplication

- LJE i :

-

Long jump escape component of each kangaroo (i)

- Decoy drop :

-

Decoy drop movement of the kangaroo

- Energy threshold :

-

Maximum permissible Energy

- X Safe :

-

Safer place

- f(Xnew i):

-

New fitness value

- CI_Lower:

-

Lower value of confidence interval

- CI_Upper:

-

Upper value of confidence interval

References

Li, S., Gong, W. & Gu, Q. A comprehensive survey on meta-heuristic algorithms for parameter extraction of photovoltaic models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 141 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.110828 (2021).

Tyagi, V. V., Rahim, N. A. A., Rahim, N. A. & Selvaraj, J. A. L. Progress in solar PV technology: research and achievement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 20 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.09.028 (2013).

Khalifa, H. et al. Parameter extraction of PV models under varying meteorological conditions using a modified electric eel foraging optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 15, 19316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98270-y (2025).

Murugaiyan, N. K., Chandrasekaran, K., Manoharan, P. & Derebew, B. Leveraging opposition-based learning for solar photovoltaic model parameter Estimation with exponential distribution optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14, 528. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50890-y (2024).

Moustafa, G., Alnami, H., Ginidi, A. R. & Shaheen, A. M. An improved Kepler optimization algorithm for module parameter identification supporting PV power Estimation. Heliyon 10 (21), e39902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39902 (2024).

Qian, J., Zhang, H. & Wang, S. Parameter identification of the PV systems based on an adapted version of human evolutionary optimizer. Sci. Rep. 15, 7375. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90802-w (2025).

Ismail, H. A. & Diab, A. A. Z. An efficient, fast, and robust algorithm for single diode model parameters Estimation of photovoltaic solar cells. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18 (5). https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.12958 (2024).

El-Sehiemy, R., Shaheen, A., El-Fergany, A. & Ginidi, A. Electrical parameters extraction of PV modules using artificial hummingbird optimizer. Sci. Rep. 13 (9240). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36284-0 (2023).

Elshahed, M. et al. An Innovative Hunter-Prey-Based Optimization for Electrically Based Single-, Double-, and Triple-Diode Models of Solar Photovoltaic Systems, Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 23, p. 4625, Dec. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/math10234625

Saripalli, B. P. et al. Advanced parameter extraction optimization technique for the four-diode model approach. e-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy. 10, 100861. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PRIME.2024.100861 (Dec. 2024).

Saadaoui, D. et al. Parameters extraction of single diode and double diode models using analytical and numerical approach: A comparative study. Int. J. Model. Simul. https://doi.org/10.1080/02286203.2023.2226285 (2023).

Choulli, I. et al. A novel hybrid analytical/iterative method to extract the single-diode model’s parameters using lambert’s W-function. Energy Convers. Manag X. 18 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecmx.2023.100362 (2023).

Ben hmamou, D. et al. Experimental characterization of photovoltaic systems using sensors based on microlab card: design, implementation, and modeling. Renew. Energy. 223 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.120049 (2024).

Chaib, L., Tadj, M., Choucha, A., El-Rifaie, A. M. & Shaheen, A. M. Hybrid Brown-Bear and hippopotamus algorithms with fractional order chaos maps for precise solar PV model parameter Estimation. Processes 12 (12), 2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12122718 (Dec. 2024).

Lu, Y., Liang, S., Ouyang, H., Li, S. & Wang, G. Hybrid multi-group stochastic cooperative particle swarm optimization algorithm and its application to the photovoltaic parameter identification problem, Energy Reports, vol. 9, pp. 4654–4681, Dec. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EGYR.2023.03.105

Xu, J. Separable nonlinear least squares search of parameter values in photovoltaic models. IEEE J. Photovoltaics. 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1109/JPHOTOV.2021.3126105 (2022).

Elhammoudy, A. et al. A novel numerical method for Estimation the photovoltaic cells/modules parameters based on dichotomy method. Results Opt. 12 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rio.2023.100445 (2023).

Mallipeddi, R., Suganthan, P. N., Pan, Q. K. & Tasgetiren, M. F. Differential evolution algorithm with ensemble of parameters and mutation strategies. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2010.04.024 (2011).

Li, S., Gu, Q., Gong, W. & Ning, B. An enhanced adaptive differential evolution algorithm for parameter extraction of photovoltaic models, Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 205, no. July p. 112443, 2020, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112443

Abd El-Mageed, A. A., Abohany, A. A., Saad, H. M. H. & Sallam, K. M. Parameter extraction of solar photovoltaic models using queuing search optimization and differential evolution[Formula presented]. Appl. Soft Comput. 134 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2023.110032 (2023).

Gao, S. et al. A state-of-the-art differential evolution algorithm for parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic models, Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 230, no. December p. 113784, 2021, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113784

Premkumar, M., Jangir, P., Sowmya, R., Elavarasan, R. M. & Kumar, B. S. Enhanced chaotic JAYA algorithm for parameter estimation of photovoltaic cell/modules, ISA Trans., vol. 116, pp. 139–166, Oct. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ISATRA.2021.01.045

Saadaoui, D., Elyaqouti, M., Assalaou, K., Hmamou, D. B. & Lidaighbi, S. Multiple learning JAYA algorithm for parameters identifying of photovoltaic models, in Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 52, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.106

Choulli, I. et al. DIWJAYA: JAYA driven by individual weights for enhanced photovoltaic model parameter Estimation. Energy Convers. Manag. 305 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118258 (2024).

Yu, K., Liang, J. J., Qu, B. Y., Chen, X. & Wang, H. Parameters identification of photovoltaic models using an improved JAYA optimization algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 150, 742–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.08.063 (2017).

Khenar, M., Taheri, S., Cretu, A. M., Hosseini, S. & Pouresmaeil, E. PSO-based modeling and analysis of electrical characteristics of photovoltaic module under nonuniform snow patterns. IEEE Access. 8 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3034748 (2020).

Choulli, I. et al. Mitigating local minima in extracting optimal parameters for photovoltaic models: an optimizer leveraging multiple initial populations (OLMIP). Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 92, 367–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2024.10.297 (Nov. 2024).

Wu, H. et al. Super-evolutionary mechanism and Nelder-Mead simplex enhanced salp swarm algorithm for photovoltaic model parameter Estimation. IET Renew. Power Gener. https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.12973 (2024).

Alsaggaf, W., Gafar, M., Sarhan, S., Shaheen, A. M. & Ginidi, A. R. Chemical-Inspired material generation algorithm (MGA) of Single- and Double-Diode model parameter determination for Multi-Crystalline silicon solar cells. Appl. Sci. 14 (18), 8549. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14188549 (Sep. 2024).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D. & Hussien, A. G. Comparative analysis of the hybrid gazelle-Nelder–Mead algorithm for parameter extraction and optimization of solar photovoltaic systems. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18 (6). https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.12974 (2024).

Abd El-Mageed, A. A., Al-Hamadi, A., Bakheet, S. & Abd El-Rahiem, A. H. Hybrid sparrow Search-Exponential distribution optimization with differential evolution for parameter prediction of solar photovoltaic models. Algorithms 17 (1). https://doi.org/10.3390/a17010026 (2024).

Hassan, M. H., Kamel, S., Ramadan, A. E. H., Domínguez-García, J. L. & Zeinoddini-Meymand, H. Optimizing photovoltaic models: A leader artificial ecosystem approach for accurate parameter Estimation of dynamic and static three diode systems. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 18 (5). https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.13121 (2024).

Smaili, I. H. et al. Enhanced artificial rabbits algorithm integrating equilibrium pool to support PV power Estimation via module parameter identification. Int. J. Energy Res. 8913560. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/8913560 (2024).

Chen, X., Wang, S. & He, K. Parameter Estimation of various PV cells and modules using an improved simultaneous heat transfer search algorithm. J. Comput. Electron. 23 (3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10825-024-02153-w (2024).

Al-Subhi, A., Mosaad, M. I. & Farrag, T. A. PV parameters Estimation using optimized deep neural networks. Sustain. Comput. Inf. Syst. 41 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suscom.2024.100960 (2024).

Chauhan, U. et al. Chaos inspired invasive weed optimization algorithm for parameter Estimation of solar PV models. IFAC J. Syst. Control. 27 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacsc.2023.100239 (2024).

Dagal, I., Akın, B. & Akboy, E. MPPT mechanism based on novel hybrid particle swarm optimization and salp swarm optimization algorithm for battery charging through simulink. Sci. Rep. 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06609-6 (2022).

Ibrahim, A. W., Xu, J., Al-Shamma’a, A. A., Hussein Farh, H. M. & Dagal, I. Intelligent adaptive PSO and linear active disturbance rejection control: A novel reinitialization strategy for partially shaded photovoltaic-powered battery charging. Comput. Electr. Eng. 123, 110037. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPELECENG.2024.110037 (Apr. 2025).

Dagal, I., Akın, B. & Akboy, E. Improved salp swarm algorithm based on particle swarm optimization for maximum power point tracking of optimal photovoltaic systems. Int. J. Energy Res. 46 (7). https://doi.org/10.1002/er.7753 (2022).

I. AL-Wesabi et al., Hybrid SSA-PSO based intelligent direct sliding-mode control for extracting maximum photovoltaic output power and regulating the DC-bus voltage. Int J. Hydrogen Energy, 51, pp. 348–370, Jan. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHYDENE.2023.10.034

Dagal, I., Ibrahim, A. W. & Harrison, A. Leveraging a novel grey Wolf algorithm for optimization of photovoltaic-battery energy storage system under partial shading conditions. Comput. Electr. Eng. 122, 109991. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPELECENG.2024.109991 (Mar. 2025).

Kodeeswaran, S., Julius Fusic, S., Kannabhiran, A., Nandhini Gayathri, M. & Padmanaban, S. Design of dual transmitter and single receiver coil to improve misalignment performance in inductive wireless power transfer system for electric vehicle charging applications. Results Eng. 24, 103602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103602 (2024). November.

Karmouni, H. et al. A Novel MPPT Algorithm based on Aquila Optimizer under PSC and Implementation using Raspberry, in 11th IEEE International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications, ICRERA 2022, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRERA55966.2022.9922834

Zhan, D., Tian, A. Q. & Ni, S. Q. Optimizing PID control for multi-model adaptive high-speed rail platform door systems with an improved metaheuristic approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 169, 110738. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJEPES.2025.110738 (Aug. 2025).

Shaheen, A. M., Ellien, A. R., El-Ela, A. A. & El-Rifaie, A. M. Uncertainty-aware multi-objective growth optimizer of EV charging stations allocation in unbalanced grids. Results Eng. 27, 106402. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2025.106402 (Sep. 2025).

Tian, A. Q., Lv, H. X., Wang, X. Y., Pan, J. S. & Snášel, V. Bioinspired discrete Two-Stage Surrogate-Assisted algorithm for Large-Scale traveling salesman problem. J. Bionic Eng. 22, 1926–1939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42235-025-00724-6 (2025).

Khaled, A., Gafar, M., Sarhan, S., Shaheen, A. M. & Alwakeel, A. S. A lyrebird optimizer with mimicry and territory protection mechanisms for spectrum sharing MIMO system with intelligent reflecting surface. Results Eng. 105519. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RINENG.2025.105519 (Jun. 2025).

Alsaggaf, W., Gafar, M., Sarhan, S., Shaheen, A. M. & Alwakeel, A. S. Multiuser wireless network enhancement via an innovative rime optimization search strategy. PLoS One. 20 (6), e0323138. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0323138 (2025).

Tian, A. Q., Liu, F. F. & Lv, H. X. Snow geese algorithm: A novel migration-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for constrained engineering optimization problems. Appl. Math. Model. 126 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2023.10.045 (2024).

Mukherjee, D., Mallick, S. & Rajan, A. A levy flight motivated meta-heuristic approach for enhancing maximum loadability limit in practical power system. Appl. Soft Comput. 114, 108146. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASOC.2021.108146 (Jan. 2022).

Mukherjee, D. & Mallick, S. Utilization of adaptive swarm intelligent metaheuristic in designing an efficient photovoltaic interfaced static synchronous series compensator. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 123, 106346. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENGAPPAI.2023.106346 (Aug. 2023).

Mukherjee, D. & Mallick, S. Efficient operation of photovoltaic-interfaced reduced switch 11-level inverter using adaptive swarm-based metaheuristic. Electr. Eng. 106 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-023-02001-3 (2024).

Alqahtani, M., Almutairi, S., Aljumah, A., Ginidi, A. & Shaheen, A. and, Enhanced power grid performance through Gorilla Troops Algorithm-guided thyristor controlled series capacitors allocation, Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 24, p. E34326, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34326

Aljumah, A., Alqahtani, M., Shaheen, A. & Elsayed, A. Enhancing power system performance via TCSC technology allocation with enhanced Gradient-Based optimization algorithm. IEEE Access, 12, pp. 97806–97832, 224AD, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3428328

Mukherjee, D. & Mallick, S. A swarm intelligent metaheuristic approach for efficient series compensation resulting in system loadability enhancement. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 50, 5795–5823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09672-5 (2025).

Chin, V. J., Salam, Z. & Ishaque, K. Cell modelling and model parameters Estimation techniques for photovoltaic simulator application: A review. Appl. Energy. 154, 500–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.05.035 (2015).

Chin, V. J. & Salam, Z. Coyote optimization algorithm for the parameter extraction of photovoltaic cells. Sol Energy. 194, 656–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.10.093 (2019).

Yang, B. et al. A novel bio-inspired caterpillar fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) optimizer for SOFC parameter identification via GRNN. Renew. Energy. 256, 123995. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RENENE.2025.123995 (Jan. 2026).

Cortez, J. A. S., Vázquez, H. P. & Delgado, A. F. P. A novel Bio-Inspired optimization algorithm based on mantis shrimp survival tactics. Mathematics 13 (9), 1500. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13091500 (2025).

Braik, M. & Al-Hiary, H. A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm inspired by water uptake and transport in plants. Neural Comput. Appl. 37, 13643–13724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-025-11228-z (2025).

Su, H. et al. RIME: A physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing 532 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.02.010 (2023).