Abstract

This article introduces a novel hybrid optimization method, the Young’s Double-Slit Experiment-Differential Evolution (YDSE-DE) technique, which is based on the integration of the YDSE approach with the robust capabilities of Differential Evolution algorithms. This integration enables the precise estimation of parameters in photovoltaic (PV) models, enhancing the modeling and simulation of solar energy systems. Employing a comparative assessment strategy, the authors demonstrate that the proposed YDSE-DE algorithm outperforms existing methods such as Ant Lion Optimizer (ALO) and Sooty Tern Optimization Algorithm (STOA) in terms of accuracy and computational efficiency. The effectiveness of this method is confirmed through rigorous testing, which shows improvements in the root mean square error (RMSE) metrics by significant margins across single-diode, double-diode, and three-diode PV models. RMSE values obtained using the YDSE-DE algorithm for the single-diode, double-diode, and three-diode models are documented as 0.0059117, 0.0015218, and 0.0018409, respectively. The present study underscores the considerable potential of the YDSE-DE algorithm in augmenting the precision and effectiveness of photovoltaic system simulation and design. The results develop and enhance the existing methodologies for PV parameter estimation and can be applied to optimize other complex systems requiring reliable and precise simulation. The novelty and scientific contribution of this work lie in the methodical synthesis of physical principles from optics with evolutionary computation, presenting a significant advancement in the field of renewable energy technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clean energy is essential worldwide to develop renewable and sustainable energy sources. This statement denotes the seventh objective within the wider framework of goals about renewable energy. Its principal emphasis is on the reduction of environmental harm and the promotion of a more sustainable future. Clean energy comprises an extensive range of sources, including but not limited to solar, wind, hydropower, and geothermal energy. Each of these forms of energy is crucial in the fight against climate change and in diminishing our dependence on limited fossil fuel reserves.

The attainment of renewable energy is of great importance, not only for developed countries but particularly for developing nations. Transitioning to pure energy sources can mitigate the environmental impact associated with conventional energy production methods, which frequently contribute to air and water pollution, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions in the context of global energy demands. Adopting renewable energy technologies offers developing nations a distinct opportunity to bypass the environmentally detrimental phases associated with industrialization, thereby promoting sustainable development. Furthermore, implementing renewable energy initiatives has the potential to bolster energy security by diversifying the energy portfolio and mitigating reliance on unpredictable fossil fuel markets. Consequently, this fosters economic resilience and stability in nations that may encounter difficulties from volatile oil prices. Beyond the ecological and financial advantages, the advancement of renewable energy is consistent with international initiatives aimed at attaining the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established by the United Nations. Ensuring affordable and environmentally friendly energy is crucial for addressing poverty, advancing health, and fostering education in developing countries. Investing in clean energy infrastructure can yield several benefits for nations: job creation, economic development stimulation, and providing dependable and sustainable energy sources for their citizens.

To summarise, the endeavor to secure sustainable energy represents an environmental objective and an all-encompassing strategy that has profound ramifications for worldwide progress. This signifies a dedication to fostering a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable future, specifically focusing on developing countries’ socio-economic advancement. As the global community collaborates to pursue these goals, renewable energy’s profound and far-reaching consequences become progressively apparent internationally. Socioeconomic development and human welfare on a global scale are presently energy-dependent. Fossil fuels comprise the most significant proportion of total generation. Nevertheless, depletion and carbon emissions are concerns linked to the utilization of fossil fuels. Global energy demand is experiencing a persistent upward trend. Extensive use of fossil fuels to meet this escalating demand will result in the emission of substantial quantities of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. In contrast, renewable energy sources are abundant in the natural environment and produce negligible greenhouse gas emissions. Hence, it is imperative in the contemporary era to prioritize using renewable energy sources in electricity production. Solar energy has traditionally occupied a central position among renewable energy sources due to its direct availability from the sun, in contrast to wind, wave, and hydro, which are derived indirectly. Solar energy is abundant and non-depletable; however, advancements in the technology required to harness this energy are ongoing. Solar photovoltaic technology converts solar radiation directly into electrical energy. The increasing adoption of photovoltaic (PV) technology as a power source at the consumer level is attributed to its straightforward installation and minimal upkeep requirements in comparison to alternative energy conversion methods1. With a global mean of 170 W/m2, PV technology has the maximum power density of all renewable energy sources2. Before their installation, dependable and precise model designs of PV systems are required to forecast their performance. Photovoltaic (PV) panels are solid and absorb an estimated 85% of incident light, of which 15% is converted into electrical energy. 70% of the power will be converted to heat3. Numerous investigations into PV systems have gained popularity in recent years due to their importance. In addition, a well-designed system is necessary to enhance overall efficiency4,5. Numerous models have been proposed to analyze the study above; the most widely used are the single-diode and double-diode models6. The latter model is more favorable in these contexts due to the close similarity between its physical module and I-V characteristics despite requiring a greater variety of computations7. The authors in8 extensively examine research and advancements in power system stability development employing FACTS controllers.

Extracting parameters for solar cell models is a non-linear, multi-variable, and multimodal problem with many local optima. Soft computing algorithms are appealing because of their global search capability. Furthermore, to tackle the growing problem of solution robustness caused by increasing model complexity, an improved RIME algorithm is developed in9 for better exploration and exploitation capabilities. This allows us to identify parameters in different PV models with more reliability and accuracy. For instance, evolutionary algorithms are an obvious choice for parameter extraction problems since they can function instead of the conventional test condition. In parameter extraction, evolution algorithm methods are favored irrespective of gradient information or knowledge of initial conditions10. In parameter extraction for solar cells, numerous evolutionary algorithms have been incorporated, including particle swarm optimization (PSO)11, genetic algorithm (GA)12,13, and simulated annealing (SA)13. From the optimum power point, the electrical properties of solar cells and parameter extraction using GA are calculated14. The PSO method is employed to derive many parameters from the PV module15,16. The breakdown and slow pace are limitations of GA17. Significant issues such as the trade-off between temperature and chilling schedule and inconsistencies render SA unsuitable for parameter extraction problems18. To enhance the reliability of the estimation, PSO is implemented alongside cluster analysis; in addition to estimating parameters, the PSO and cluster analysis filter out impracticable solutions19,20. This improves consistency and dependability despite requiring the storage of all preceding points. As a consequence of the augmented computational load, the pace of the simulation will be significantly diminished. Expanding the searching space for the parameters while extracting procedures to adhere to distinct boundary conditions is advisable to mitigate convergence issues.21 researched a two-diode model for photovoltaic modules that is precise and quick. Furthermore, A PSO and chaos theory are hybridized to generate a chaotic PSO (CPSO), which may be utilized to optimize the simultaneous coordinated design of a multi-machine power system stabilizer (PSS) and static VAR compensator (SVC) damping controller in22. The authors in23 proposed a hybrid evolutionary algorithm designed for precise and effective parameter estimation from experimental data of various PV models. In contrast, in24, a hybrid seagull optimization algorithm is designed to determine the unknown parameters of photovoltaic models.

This study makes several significant contributions to the field of photovoltaic system optimization and renewable energy research:

-

Building a Novel Hybrid Algorithm Development: We introduce the YDSE-DE algorithm, a novel hybrid optimization method that integrates the conceptual framework of the Young’s Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE) with the robust optimization capabilities of Differential Evolution (DE). This approach innovatively applies quantum mechanics principles to computational optimization in photovoltaic systems.

-

The proposed YDSE-DE algorithm significantly improves the accuracy of parameter estimation for PV models. By optimizing both the single-diode, double-diode, and three-diode models, the method achieves lower RMSE values compared to traditional and contemporary optimization algorithms.

-

Through extensive simulations and comparative assessments, the effectiveness of the YDSE-DE algorithm is demonstrated against several established optimizers such as the Ant Lion Optimizer (ALO) and Sooty Tern Optimization Algorithm (STOA). Our results validate the superiority of YDSE-DE in terms of convergence speed and accuracy.

-

The study elucidates the practical applicability of the YDSE-DE algorithm, showing its potential to enhance the design and efficiency of real-world solar energy systems, thereby contributing to the advancement of renewable energy technologies.

-

The research contributes to theoretical advancements by blending physical phenomena with algorithmic development, offering a new perspective on solving complex optimization problems. Methodologically, it sets a precedent for future research in applying principles of physics to enhance computational techniques.

These contributions not only pave the way for more precise and efficient photovoltaic systems but also open up new avenues for applying hybrid optimization strategies to other complex engineering challenges.

The subsequent sections are structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses the modeling of PV models. Section 3 explains the problem formulation. Section 4 analyses the Youngs double-slit experiment optimizer (YDSE) algorithm . In Section 5, the simulation and results are discussed. The conclusions of this paper are presented in Section 6.

Definition of PV models

This section details the mathematical formulation for the three PV models (TPVM). The TPVM consists of one diode model (SDM), two diode models (DDM), and three diode models (TDM).

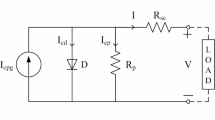

Single diode model

Figure 1 illustrates the SDM equivalent circuit. For the current output of this model, the subsequent formulation is utilized:

The SDM produces a current denoted as I, where \({{I}_{pv}}\) represents the generated light current, \({{I}_{sh}}\) signifies the leakage current, and \({{I}_{D1}}\) stands for the dark saturation current. \({{R}_{p}}\) and \({{R}_{s}}\) represent the shunt and series resistances, respectively. Additionally, \({{n}_{1}}\) is the diode ideality factor, K is Boltzmann’s constant, q is the charge of an electron, and \({{T}_{c}}\) represents the cell temperature. According to the provided mathematical formula, the parameters to be estimated in SDM include (\({{I}_{pv}}\), \(~{{I}_{o1}}\), \({{n}_{1}}\), \({{R}_{s}}\) and \({{R}_{p}}\).

Double diode model

Figure 2 depicts the electrical diagram for the DDM. To enhance the output quality, this model necessitates the incorporation of two diodes. The current output is computed using the following equations:

where ID2 represents the second diode dark saturation current, and n2 is the ideality factor of the second diode. This model encompasses seven estimated parameters: Ipv, Io1, n1, Rs, Rp, Io2, and n2.

Triple diode model

The alternative design for PV modules is exemplified by the three-diode model (TDM) depicted in Fig. 3, which incorporates three diodes. The current output in this model is computed using Eq.5.

where ID3 represents the dark saturation current of the third diode, and n3 signifies the ideality factor of the third diode. The TDM involves the estimation of nine parameters: Ipv, Io1, n1, Rs, Rp, Io2, n2, Io3, and n3.

Problem formulation

The performance of TPVM performed according objective functions the root mean square error (RMSE) objective functions between the current computed by using the estimated parameters and the current from the data set. The Eq. 7 and Eq. 8 define the RMSE.

Where \({{I}_{exp}}\), is the experimental current, N is the reading data number and X is the set of decision variables.

The vector of decision variable for SDM is \(X=\left\{ \left( {{I}_{pv}},~{{I}_{o1}},~{{n}_{1}},~{{R}_{s}}~and~{{R}_{p}}~ \right) \right\}\).

The vector of decision variable for DDM is \(~X=\left\{ \left( {{I}_{pv}},~{{I}_{o1}},~{n}_{1},~{{R}_{s}},~{{R}_{p}},~{{I}_{o2}}~and~{{n}_{2}}~ \right) \right\}\).

The vector of decision variable for TDM is \(X=\left\{ \left( {{I}_{pv}},~{{I}_{o1}},~{{n}_{1}},~{{R}_{s}},~{{R}_{p}},~{{I}_{o2}},~{{n}_{2}},~{{I}_{o3}}~and~{{n}_{3}} \right) \right\}\).

The parameters for the TPVM could be estimated by using optimization algorithms. In this paper, the information used for the PVM is taken from the R.T.C France solar cell. In addition here is proposed the use of the Young’s double-slit experiment (YDSE) algorithm that was recently published. The Results of the m_YDSE are compared with the Ant Lion Optimizer (ALO), Sooty Tern Optimization Algorithm (STOA), Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SOA), Rat Swarm Optimizer (RSO), (YSDE) compared with other algorithms such as modified particle swarm optimization (MPSO) algorithm. The bounds of the search space for the parameter estimation problem using the for R.T.C France solar cell are listed in Table 125.

The proposed methodology

In the quest to refine the accuracy and efficiency of parameter estimation for photovoltaic (PV) models, this paper introduces a novel optimization framework that integrates the principles of the Young’s Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE) with the robustness of Differential Evolution (DE). This section delineates the proposed methodology, which leverages the unique interference pattern analysis inherent to YDSE and the adaptive potential of DE to form the YDSE-DE hybrid algorithm. Our approach aims to harness the strengths of both algorithms, optimizing the exploration and exploitation phases within the parameter estimation process. The integration is designed to address the complexities of accurately modeling PV systems while ensuring computational efficiency and reliability in the obtained results. The following subsections will detail each component of the methodology, providing a comprehensive blueprint of the algorithmic processes involved.

Youngs double-slit experiment optimizer (YDSE) algorithm

The Young’s double-slit experiment optimizer (YDSE) is a novel metaheuristic optimization algorithm inspired by the famous Young’s double-slit experiment in physics26. This experiment demonstrates the wave nature of light by showing how light can interfere with itself, creating alternating bright and dark bands on a screen. The YDSE algorithm mimics this wave behavior to find optimal solutions to complex optimization problems. The basic mathematical steps behind the YDSE algorithm are illustrated below:

Initial population

The initial step in the YDSE process involves projecting a source of monochromatic light waves (S) into a barrier that consists of two slits that are closely spaced apart. Thus, the initial monochromatic light source S is constructed from NP waves with D dimension for each according to Equation 9:

where \(S_{i,j}\) represents the \(j^{th}\) variable of the \(i^{th}\) monochromatic wave (i.e., \(i=1,...,NP\) and \(j=1,...,D\)). \(Lb_j\) and \(Ub_j\) represent the lower and upper bounds of the jth variable, respectively, while rand generates a random number \(\in (0,1)\).

Huygens principle

According to Huygens’ principle, monochromatic waves propagate in all directions from each slit, with each wavefront point functioning as both a source and a center of the wavefront. Considering the number of points on the wavefront, equal to the size of waves NP, each having one beam, can be calculated using the following equations ( Eq. 10 ,Eq. 11 , and Eq. 12 .):

where \(FS_i\) and \(SS_i\) are the ith point emanating from the wavefront outgoing from the first (FS) and second (SS) slit, respectively. \(S_i\) represents the ith monochromatic wave to be released through slits. L determines how far away the light source is from the barrier. \(S_{\text {best }}\) and \(S_{\text {mean }}\) are the best and the mean individual of the current population S, respectively. Both rand1 and rand2 are random numbers assigned a uniform distribution within the range (-1,1) that simulate light ray dispersal in various directions.

Traveling waves and path difference update

Since waves emitted by the two slits (FS and SS) may travel various distances to reach the screen locations, the spots on these wavefronts determine the interference patterns according to Equations 10 and 11. In YDSE, the projection screen displays light fringes at constructive interference (CI) sites and dark fringes at destructive interference (DI) points. Starting with the central fringe, which has an order number of zero, the bright and dark fringes are arranged in a certain way. The dark fringe requires an odd number, whereas the bright fringe requires an even number. The position update technique can simulate the two interfering waves (CI and DI), and their respective paths to the screen are represented mathematically according to Equation 13.

Where \(\Delta L\) defines the path difference between \(FS_i\) and \(SS_i\), based on the order number of the fringes formed upon reaching the screen, as illustrated in the following formula (Eq. 14):

Where m represents the order number (i.e., \(m=i-1\)).

Two waves, one emitting from each slit, travel different paths to the screen, as can be shown in Equations 13 and 14, and fringes are the patterns of light that appear as they reach the screen. According to the YDSE method, the middle fringe, where \(\Delta L\) is zero, is a near-optimal solution. The larger the \(\Delta L\) amount, the further the fringe is from the center fringe.

Light patterns generation

Fringes, which are patterns of light that emerge on the projection screen after CI and DI, are the source of the population X created in Eq.13. Since the fringe locations are constant, the interference between any two wavelengths is also constant in the YDSE algorithm. The best solution in the search space, \(X_m=0\), represents the central fringe. In contrast, \(X_{m_{odd}}\) and \(X_{m_{even}}\), respectively, are representations of the dark and bright fringes that have undergone iterative optimization.

Wave amplitude update process

The phenomenon known as CI occurs when two waves merge into one with a stronger amplitude than the original waves, according to Equation 15.

where \(A_{\text {bright }}^{t+1}\) reflects the mean wave amplitude at the bright fringe at iteration (\(t + 1\)), and \(\beta\) is the function that mimics the growing amplitude of the resulting wave at the bright fringe over time (i.e., \(\beta =\frac{t}{T} \cosh (\pi / t)\)).

Conversely, DI happens when two waves mix and cancel each other out, resulting in a smaller amplitude, according to Equation 16.

where \(\delta\) is a constant with a value of 0.38. This equation represents the wave’s amplitude at the black fringe, which decreases with each iteration.

YDSE optimizer

The search space is divided into three regions: dark, bright, and central. The YDSE optimizer divides an order number by particles to determine fringe locations. The order number is related to the position of the fringe/particle in the search space. Agents are guided towards the ideal global solution and away from local solutions via procedures for the exploration and exploitation stages, which update locations in the three areas.

Exploration phase (destructive interference)

In this phase, the solution is guided across search space according to its order number while it undergoes optimization. It traverses the dark areas towards the central light region, which is believed to have the optimum solution if its number is odd. Therefore, the proposed position update strategy in Equation 17 aims to enhance the YDSE optimizer’s ability to avoid local optima by exploring promising positions in dark regions.

Where \(X_{m_{\text {odd }}}^{t}\) and \(X_{m_{\text {odd }}}^{t+1}\) are the current and the updated \(m_{\text {odd }}^{t h}\) dark fringe. \(r_1\in (0,1)\) and \(A_{\text {dark }}^{t+1}\) defined before according to Equation 16. \(In t_{m_{\text {odd }}}^{t+1}\) represents the \(m_{\text {odd }}^{t h}\) dark fringe’s light intensity and computed based on Equation 19

\(y_{dark}^{t+1}\) finds out how far the center fringe is from the \(m_{\text {odd }}^{t h}\) dark fringe (i.e., \(y_{\text {dark }}=\frac{\lambda L}{d}\left( m+\frac{1}{2}\right)\)) while z is a trial vector of dimension D which is computed according to Equation 20, and \(X_{\text {best }}^t\) is the best solution at the current iteration.

A random vector H is defined in the range [-1, 1], and the random number \(r_3\) is defined in the range [0, 1].

Exploitation phase (constructive interference)

The YDSE algorithm utilizes the promising regions inside the bright fringe zones, which are believed to have the optimal solution, and these regions are updated according to Equation 21.

where \(X_{m_{\text {even }}}^{t}\) and \(X_{m_{\text {even }}}^{t+1}\) are the current and updated \(m_{\text {even }}^{t h}\) bright fringe, respectively. g is a random number generated within the range of -1 to 1. \(A_{\text {bright }}^{t+1}\) computed before according to Equation 15. Y represents the disparity between two randomly chosen fringes, possibly light, dark, or a combination. \(In t_{m_{\text {even }}}^{t+1}\) represents the \(m_{\text {even }}^{t h}\) light fringe’s light intensity and computed based on Equation 24

\(I n t_{m_{\text {even }}}^{t+1}\) finds out how far the center fringe is from the \(m_{\text {even }}^{t h}\) bright fringe. \(I n t_{\text {max }}^{t+1}\) shows the highest intensity observed in the center area. Therefore, the updated strategy in the central region can be computed according to Equation 25

where \(X_{m_{\text {zero }}}^t\) and \(X_{m_{\text {zero }}}^{t+1}\) determine the current and new central regions, with an order number of zero. \(r_3\) is a randomly generated number between 0 and 1. C is a constant value equal to \(10^{-20}\) at the end of iterations. At the same time, q is an increasing parameter during iterations from 0 to 1. \(X_{r_b}^t\) stands for a bright fringe picked at random from the set of integers belonging to the even order, where rb is an even integer.

Finally, the overall process of updating procedure can be done according to Equation 28 and Fig. 4 shows the basic steps of the YSDE algorithm.

Differential Evolution Strategy

Differential Evolution (DE) is an effective algorithm developed by Storn and Price for addressing complex, non-linear problems through a population-based search mechanism. Initially, the algorithm generates a population of N candidate solutions, each represented by a vector \(\textbf{X}_i = (X_{i1}, X_{i2}, \dots , X_{in})\), where i ranges from 1 to N and n denotes the number of dimensions in the problem.

Mutation

The mutation step involves creating a mutant vector \(\textbf{V}_i = (v_{i1}, v_{i2}, \dots , v_{in})\) for each candidate \(\textbf{X}_i\) by employing a mutation operator. A frequently used mutation strategy is the ’DE/best/1’ strategy, expressed as Eq. 29:

In this formula, t indicates the current iteration, \(\textbf{X}^*(t)\) is the current best individual vector in the population, \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are distinct random indices within the set [1, N] excluding i, and F is a scaling factor between 0 and 1 that influences the degree of the mutation.

Crossover

Following mutation, the crossover operation combines the mutant vector \(\textbf{V}_i\) with the original vector \(\textbf{X}_i\) to form a trial vector \(\textbf{U}_i = (u_{i1}, u_{i2}, \dots , u_{in})\). One common approach is the binomial crossover, defined as Eq.30 :

Here, \(j_{\text {rand}}\) is a randomly chosen index from [1, n], ensuring at least one dimension from \(\textbf{V}_i(t)\) is incorporated in \(\textbf{U}_i\). CR is the crossover rate ranging from 0 to 1, and \(r_j\) is a uniformly distributed random number between 0 and 1.

Selection

In the selection phase, the fitness of each trial vector \(\textbf{U}_i(t)\) is compared to its corresponding target vector \(\textbf{X}_i(t)\). The vector with superior fitness is retained for the next generation (Eq. 31:

This procedure repeats until the stopping criteria are met, which may be a maximum number of generations or a convergence threshold.

This methodology underscores the innovative integration of PDO and DE to form a robust tool for tackling optimization challenges in engineering and other complex fields.

Proposed YDSE-DE Algorithm

This section introduces the YDSE-DE algorithm, a novel hybrid approach that combines the strengths of the Young’s Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE) optimizer with the robust optimization capabilities of the Differential Evolution (DE) strategy. The integration aims to harness the explorative power of YDSE and the exploitation efficiency of DE to address complex optimization challenges more effectively.The complete YDSE-DE approach is summarized in the following pseudocode:

Initialization

The YDSE-DE algorithm begins with the generation of an initial population of solutions, where each individual solution vector is initialized using the YDSE’s method of simulating light waves passing through slits to create interference patterns. Each pattern corresponds to a potential solution in the search space.

Hybrid Optimization Process

The hybrid algorithm proceeds through a series of iterative steps that alternate between the YDSE and DE processes:

-

1.

Interference Calculation (YDSE): Each solution is evaluated based on the interference pattern it produces, analogous to evaluating the fitness of each solution in traditional optimization terms.

-

2.

Mutation (DE): For each individual in the population, a mutant vector is generated using the DE formula by Eq. 32:

$$\begin{aligned} \textbf{V}_i = \textbf{X}_{\text {best}} + F \cdot (\textbf{X}_r1 - \textbf{X}_r2) \end{aligned}$$(32)where \(\textbf{X}_{\text {best}}\) is the best solution found so far, \(\textbf{X}_r1\) and \(\textbf{X}_r2\) are solution vectors selected at random, and F is the differential weight.

-

3.

Wave Superposition (YDSE): The mutant vectors are then subjected to a wave superposition step where YDSE’s principles determine the constructive and destructive interference outcomes, influencing the next generation of solutions.

-

4.

Crossover and Selection (DE): Crossover is applied between the mutant vectors and the current population, followed by a selection process where the better of the original or the mutant vector is chosen for the next generation, based on their fitness values.

Adaptation and Termination

The YDSE-DE algorithm adapts through generations, continuously refining the solutions by balancing the global search capabilities of YDSE and the local exploitation strength of DE. The process repeats until a stopping criterion is met, such as reaching a maximum number of iterations or achieving a satisfactory convergence level.

This methodology leverages the complementary strengths of YDSE and DE to create a powerful tool for solving a broad spectrum of optimization problems, enhancing the diversity and convergence rate of the search process.

Complexity Analysis

This section provides a detailed analysis of the computational complexity of the hybrid Young’s Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE) and Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm (YDSE-DE), applied to optimization problems in photovoltaic systems.Incorporating the principles of both YDSE and DE, the YDSE-DE algorithm aims to leverage the global search capabilities of YDSE with the efficient local search and robustness of DE. Understanding the computational complexity of this hybrid approach is crucial for evaluating its practicality for large-scale optimization problems.

The YDSE-DE algorithm integrates operations from both YDSE and DE, each contributing to the overall computational load. Below, we detail the complexity contributions from various components of the algorithm.

Algorithm Components

-

Population Initialization: Initializing a population of size N with a problem dimensionality of D. The complexity of this step is \(O(N \times D)\).

-

Fitness Evaluation: Each solution’s fitness is evaluated once per generation, with complexity \(O(f)\) for each evaluation, resulting in \(O(N \times f)\) per generation.

-

Mutation and Crossover (DE): Both mutation and crossover operate on each individual in the population, contributing a complexity of \(O(N \times D)\) for each operation.

-

Selection: The selection process involves comparing fitness values, with a complexity of \(O(N)\).

-

YDSE Adjustments: Additional computations based on YDSE principles, estimated at \(O(N \times f)\) for interference pattern calculations and adjustments.

Total Complexity Per Generation

Combining the complexities from all components, the total computational complexity per generation can be estimated as:

where 2f accounts for fitness evaluations in DE and adjustments by YDSE, 2D for the DE operations, and 1 for selection.

Overall Complexity

Considering the algorithm runs for T generations, the overall complexity is:

This estimate highlights the influence of both the problem size and algorithmic parameters on the computational demands of the YDSE-DE algorithm.

While the hybrid approach integrates the strengths of Young’s Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE) and Differential Evolution (DE) to enhance parameter estimation accuracy, it introduces a higher computational burden per generation compared to traditional optimization methods. The increased complexity may pose challenges in terms of processing time, memory usage, and hardware requirements, especially when applied to high-dimensional optimization problems. However, despite its computational demands, YDSE-DE demonstrates faster convergence rates and robust solution exploration, making it a viable choice for scenarios where precision is critical. To address potential scalability issues, the adoption of parallel computing, cloud-based simulations, and adaptive algorithm tuning is recommended to enhance computational efficiency without compromising accuracy.

Results and Simulation

This section presents comprehensive experiments that state the effectiveness of a Enhanced Young’s double-slit experiment (YDSE) based on Differential Evolution (DE) algothim (m_YDSE) for the parameter identification of the three PV models. The improved proposed method is applied to identify the parameters of three PV models across various solar cells. These include the RTC France cell, Photowatt-PWP201 cell, Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W cell, Ultra 85-P cell, and STM6-40/36 module cell. Experiments were conducted for each cell on the three PV models: the Single-Diode Model (SDM), Double-Diode Model (DDM), and Triple-Diode Model (TDM). The proposed approach is utilized for the accurate estimation of photovoltaic parameters and to assess its effectiveness across various configurations of PV models.

Testing accuracy of the suggested m_YDSE estimates the unknown parameters for those three distinct PV models. This section proposes comparative experiments and justifies our recommendation of the proposed optimization algorithm. Results of the m_YDSE are compared with Ant Lion Optimizer (ALO)27, Sooty Tern Optimization Algorithm (STOA)28, Seagull Optimization Algorithm (SOA)29, Rat Swarm Optimizer (RSO)30, YDSE.The m_YDSE method and the competing algorithms have been tested using the Ultra dataset in 31 different runs with 500 iterations in each run to provide a fair benchmarking comparison. We conduct experiments on a machine with the following specifications: 64-bit Windows 10 Professional, 2.40GHz Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4700MQ processor, and 16GB of RAM. MATLAB R2019a is used for the implementation of each algorithm.

The m_YDSE achieved the best performance in terms of Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for SDM (0.0059117), DDM (0.0015218), and TDM (0.0018409).

The parameter settings for each algorithm can be found in Table 2. In our study, the choice of algorithmic parameters such as population size, mutation factor, crossover rate, and the number of iterations was informed by a combination of existing literature on evolutionary algorithms and preliminary tuning experiments conducted prior to the main benchmarking. For instance, a population size of 30 and a maximum of 500 iterations were selected as these values offered a balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and solution accuracy across various photovoltaic models. The mutation and crossover factors were set within commonly used ranges to maintain exploration and exploitation balance.

Regarding the experimental datasets, we selected the RTC France solar cell alongside several commercial photovoltaic modules (Photowatt-PWP201, Kyocera KC200GT, Ultra 85-P, and STM6-40/36) to encompass a diverse range of cell technologies and characteristics, ensuring broad applicability of our findings. We acknowledge that while the chosen parameters and datasets provide a robust evaluation framework, adapting the algorithm’s parameters might be necessary when applied to other solar cell configurations or emerging PV technologies, which may exhibit distinct electrical behaviors or environmental sensitivities. This consideration is important for readers intending to extend or customize the YDSE-DE algorithm in different contexts.

The experiments are presented in a structured manner as follows:

-

Table 3 presents the experiments conducted on the RTC France cell with the SDM approach.

-

Table 4 presents the experiments conducted on the RTC France cell with the DDM approach.

-

Table 5 presents the experiments conducted on the RTC France cell with the TDM approach.

-

Table 6 presents the experiments conducted on the Photowatt-PWP201 cell with the SDM approach.

-

Table 7 presents the experiments conducted on the Photowatt-PWP201 cell with the DDM approach.

-

Table 8 presents the experiments conducted on the Photowatt-PWP201 cell with the TDM approach.

-

Table 9 presents the experiments conducted on the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W cell with the SDM approach.

-

Table 10 presents the experiments conducted on the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W cell with the DDM approach.

-

Table 11 presents the experiments conducted on the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W cell with the TDM approach.

-

Table 12 presents the experiments conducted on the Ultra 85-P cell with the SDM approach.

-

Table 13 presents the experiments conducted on the Ultra 85-P cell with the DDM approach.

-

Table 14 presents the experiments conducted on the Ultra 85-P cell with the TDM approach.

-

Table 15 presents the experiments conducted on the STM6-40/36 module cell with the SDM approach.

-

Table 16 presents the experiments conducted on the STM6-40/36 module cell with the DDM approach.

-

Table 17 presents the experiments conducted on the STM6-40/36 module cell with the TDM approach.

The accuracy of P-V and I-V estimations, and their similarity to actual measurements, are recorded to demonstrate the efficiency of the estimation. The RMSE over 30 trials is measured and compared to state-of-the-art algorithms. Additionally, the time complexity to reach saturation and minimal RMSE is discussed in the following subsections.

The m_YDSE method, along with competing algorithms, has been tested on different datasets in 30 separate experiments, each with 500 iterations, to ensure a fair comparison. All experiments were conducted on a system with the following specifications: 64-bit Windows 10 Professional, Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4700MQ processor at 2.40GHz, and 16GB of RAM. MATLAB R2019a was used for the implementation of each algorithm.

RTC france

Experiments on Single-Diode mode based RTC France Cell

Table 3 contains the corresponding Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values for the parameter values that exhibit the highest level of accuracy. The table details the experimental outcomes after each optimizer was executed thirty times on the SDM-based RTC France. The outcomes indicate that m_YDSE algorithm is the most effective algorithm. Its Best RMSE performance is comparable to or surpasses other algorithms in all performance metrics. As determined by the worst RMSE outcomes, m_YDSE, in contrast, demonstrates parity with fifty percent of the algorithms. The standard deviation is also documented as a supplementary metric for evaluating performance. m_YDSE consistently maintains parity or delivers superior performance compared to alternative algorithms, never exhibiting substandard results. Discrepancies between the outcomes produced by m_YDSE and those produced by alternative algorithms become more apparent upon inspection of the fill factor and Iphoto parameters.

It is important to note that while the proposed YDSE-DE algorithm consistently achieves lower RMSE values across different photovoltaic models, the fill factor (FF) exhibits some variability when compared to other algorithms such as YDSE. The fill factor is a sensitive parameter influenced by multiple estimated variables, and its behavior can fluctuate due to the complex interactions among these parameters. Additionally, as metaheuristic algorithms inherently involve stochastic processes, slight variations in convergence paths can lead to differences in FF values across runs. Therefore, improvements in RMSE do not always directly translate to proportional enhancements in the fill factor. This observation underscores the trade-offs present in parameter optimization for photovoltaic models, and highlights the need for a balanced consideration of multiple performance metrics when evaluating optimization algorithms.

The FF value represents the efficiency of the solar cell in converting sunlight to electrical energy. Here, the FF fluctuates slightly across the different algorithms, but it is notable that YDSE-DE provides a fill factor of 0.70039, which is relatively high compared to the YDSE algorithm (FF = 0.66406). The YDSE-DE algorithm consistently exhibits stable and competitive FF values, which indicate that while the optimization algorithm may experience some variations in the optimization path, it still provides a reliable model with optimal performance.

While the fill factor (FF) is an important indicator of solar cell efficiency, its slight fluctuations in the results of different algorithms are a known characteristic of optimization algorithms. In this paper, the YDSE-DE algorithm shows a general trend of higher fill factor values across multiple trials, suggesting that it is more stable and efficient compared to the other algorithms. It is important to recognize that while RMSE values are typically the primary focus for evaluating the accuracy of parameter estimation, the fill factor offers insights into the efficiency of the photovoltaic model. A low RMSE combined with a reasonable FF demonstrates that the YDSE-DE algorithm balances both optimization accuracy and system efficiency effectively. The YDSE-DE algorithm consistently outperforms other algorithms in terms of RMSE and fill factor stability, showing its capability to produce reliable and precise estimates across a range of different solar cell models and optimization conditions.

While the Iphoto values show small variations among algorithms, these values do not directly correlate with the fill factor as they are related to the light-generated current. The I-V characteristics and P-V characteristics curves generated by YDSE-DE match closely with experimental data, demonstrating the algorithm’s ability to model the electrical behavior of solar cells accurately.

The results from Fig. 5 show that the m_YDSE algorithm outperforms other optimization techniques, such as ALO, SOA, STOA, and RSO, when applied to the RTC France solar cell using the Single Diode Model (SDM). While the m_YDSE does not converge as quickly as some alternatives, it achieves the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), making it the most accurate algorithm for parameter estimation. The convergence curve indicates that m_YDSE stabilizes around 120 iterations, balancing computational time and accuracy. The close alignment of the P-V and I-V characteristics produced by m_YDSE with the experimental data further demonstrates its precision in modeling the electrical behavior of solar cells.

In comparison to other algorithms, m_YDSE consistently delivers lower standard deviation values, indicating that its results are not only accurate but also stable across multiple trials. This makes it an ideal choice for photovoltaic (PV) modeling where reliable performance is critical. Despite the slower convergence rate, the trade-off in accuracy is worthwhile, particularly in applications where precise parameter estimation is paramount. Overall, the m_YDSE algorithm’s superior RMSE and consistent performance highlight its potential for enhancing PV system simulations and optimizations, especially for SDM-based models like the RTC France solar cell.

Figure 5a demonstrates the convergence behavior of different algorithms in minimizing the RMSE for the RTC France solar cell using the Single Diode Model (SDM). The m_YDSE algorithm shows a slower convergence compared to some algorithms, such as STOA, but it eventually reaches a lower RMSE value after approximately 120 iterations. This indicates that while m_YDSE takes more time to stabilize, it achieves better accuracy in the end. The curve highlights the algorithm’s balance between exploration and exploitation, enabling it to find a more precise solution despite the slower convergence.

Figure 5b shows P-V Characteristics , the power-voltage (P-V) characteristics generated by the m_YDSE algorithm are compared against experimental data. The curve shows a high degree of alignment between the predicted and actual power output of the RTC France solar cell. This suggests that the m_YDSE algorithm effectively captures the nonlinear behavior of the photovoltaic system, resulting in a precise estimation of parameters that closely mimic real-world performance. The accuracy of the P-V curve reinforces the suitability of m_YDSE for practical photovoltaic applications.

Figure 5c illustrates the minimum fitness values (RMSE) achieved by the different algorithms across multiple trials. The m_YDSE algorithm consistently delivers lower minimum fitness values, indicating that it produces more accurate results across different runs compared to the other algorithms. The lower fitness value emphasizes the reliability and robustness of the m_YDSE algorithm in producing optimal parameter estimations with minimal error, further supporting its effectiveness in photovoltaic modeling.

Figure 5d shows I-V Characteristics. The current-voltage (I-V) characteristics in this subfigure show how well the m_YDSE algorithm’s predicted results match the experimental data for the RTC France solar cell. Like the P-V characteristics, the I-V curve demonstrates a close correlation between the algorithm’s output and the measured data, validating the algorithm’s accuracy in estimating photovoltaic parameters. The precise match of the I-V characteristics highlights the algorithm’s capability to model the electrical performance of solar cells accurately, making it a strong candidate for improving photovoltaic system simulations.

Experiments on Double-Diode mode based RTC France Cell

THE RSME values for the best and worst outcomes are recalculated and presented in Table 4 after thirty iterations of algorithm execution on the DDM-based RTC France. The table’s findings suggest that, compared to the other algorithms assessed, m_YDSE algorithm attains the most significant root mean square error (RMSE). m_YDSE significantly surpasses 90% of the alternative algorithms, as evidenced by the most flagrant root mean square error (RMSE) value documented in Table 4. Illustrated in Fig. 6-a is the convergence curve of the DDM-based algorithms that were implemented. By achieving the minimal Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), m_YDSE surpasses the performance of the alternative algorithms. While not designed for speed, the m_YDSE algorithm achieves saturation after approximately 130 iterations, which is considered an acceptable convergence rate. Its consistent ability to achieve the minimum RMSE values significantly compensates for this convergence behavior.

The fill factor in this case shows some variation across different algorithms, ranging from 0.69385 for STOA to 0.7606635854 for m_YDSE. The YDSE-DE algorithm achieves the highest FF, suggesting that it optimizes the system more efficiently, ensuring better electrical output from the photovoltaic model. Although the FF is not always the highest for every individual trial, it shows a general improvement in stability and performance compared to other methods.

The analysis of Fig. 6 highlights a comparison between different algorithms based on the Double Diode Model (DDM) for the RTC France solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm shows superior performance in minimizing Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), achieving lower error values compared to other algorithms like ALO, SOA, and STOA. The convergence curve (Fig. 6-a) indicates that while m_YDSE does not converge as quickly as some of its counterparts, it ultimately reaches a more accurate solution after approximately 130 iterations. This balance between convergence speed and accuracy makes m_YDSE particularly effective for DDM-based parameter estimation tasks.

Further comparison of the I-V and P-V characteristics (Fig. 6b,d) reveals that m_YDSE generates results closely aligned with the experimental data, validating its precision in predicting the behavior of the solar cell. Additionally, the statistical performance metrics such as standard deviation and fill factor show that m_YDSE consistently outperforms other algorithms in stability and robustness across multiple trials. This makes m_YDSE a strong candidate for applications requiring reliable and accurate modeling of photovoltaic systems using the Double Diode Model.

Experiments on Triple-Diode model-based RTC France Cell

Table 5 employing the m_YDSE algorithm on RTC France data, this segment ascertains the most influential parameters for the Three Diode Model (TDM), thus facilitating a comprehensive evaluation of its performance. Various algorithms generate the outcomes within the specified context. The superiority of the m_YDSE algorithm over the alternatives and its superior effectiveness are indisputable. Additionally, the root mean square error (RMSE) values are displayed in the table, allowing for a comparison of m_YDSE’s performance with that of its competitors. This distinguishes m_YDSE considerably from all other algorithms that were evaluated .

The fill factor for the TDM also shows competitive results, with YDSE-DE reaching 0.7605609 compared to 0.7599 for ALO and 0.7606 for SOA. The slight variability in the FF is attributed to the inherent stochastic nature of the optimization algorithms, but it still represents a reliable efficiency level for photovoltaic systems.

The results from Fig. 7 compare different algorithms for parameter estimation based on the Triple Diode Model (TDM) for the RTC France solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm demonstrates its superiority by consistently achieving the lowest RMSE values, indicating its ability to precisely estimate parameters in TDM-based systems. Despite a slower convergence compared to some competing algorithms, such as STOA or ALO, m_YDSE reaches a more accurate solution after approximately 130 iterations. The close alignment between the I-V and P-V characteristics generated by m_YDSE and the experimental data validates its reliability in accurately modeling the performance of the RTC France solar cell under TDM.

Moreover, m_YDSE consistently exhibits lower standard deviation values across multiple trials, highlighting its stability and robustness in producing optimal parameter estimations. Its strong performance in both I-V and P-V curves further emphasizes its effectiveness in predicting the electrical characteristics of the solar cell. Overall, the m_YDSE algorithm proves to be highly reliable for TDM-based modeling, outperforming other algorithms in terms of both accuracy and consistency.

Figure 8 provides a comparison of the runtime between different algorithms used for the RTC France cell. The m_YDSE algorithm, while highly accurate in parameter estimation, has a relatively higher runtime compared to simpler algorithms like ALO and RSO. This increased computational time can be attributed to the algorithm’s more thorough search and optimization process. However, it balances this by providing more precise parameter estimations, which can justify the longer runtime in applications where accuracy is critical.

In contrast, algorithms like STOA and RSO demonstrate faster runtimes but tend to compromise on the precision of their results, as indicated in previous figures. The trade-off between runtime and accuracy is evident, with faster algorithms potentially being more suitable for real-time applications or cases where rough estimations are sufficient. However, m_YDSE’s combination of moderate runtime and superior accuracy makes it a strong candidate for scenarios requiring detailed and precise parameter estimation despite the additional computational effort.

Photowatt-PWP201

Experiments on Single-Diode model (SDM)-based Photowatt-PWP201

Table 6 presents a comparison of various algorithms applied to the Photowatt-PWP201 solar cell using the Single Diode Model (SDM). The table evaluates parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation current (\(I_0\)), non-ideality factor (A), and other performance metrics like the root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)). The best performance is observed with the VYSE algorithm, which achieved the lowest RMSE value of 0.000844. In contrast, the ALO algorithm produced the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.008591. The table provides an analysis of these algorithms under various conditions, highlighting their accuracy and effectiveness in modeling solar cell characteristics.

The FF for the YDSE-DE algorithm is 0.66746, which is competitive but slightly lower than other algorithms like ALO (0.66137). However, the FF value still indicates good efficiency, and the high RMSE performance suggests that the slight decrease in FF does not impact the overall quality of the PV model.

Figure 9 presents a comparison between various algorithms based on the Single-Diode Model (SDM) applied to the Photowatt-PWP201 solar cell. The results show that the m_YDSE algorithm achieves superior accuracy, reflected in its lower RMSE values, compared to other algorithms such as ALO, SOA, and STOA. The m_YDSE algorithm closely matches the experimental P-V and I-V curves, demonstrating its high precision in estimating parameters. The convergence curve further highlights the algorithm’s efficiency, as it reaches optimal performance after fewer iterations than some competitors. This indicates that while m_YDSE may take slightly longer to converge, it delivers more accurate parameter estimations.

Additionally, the m_YDSE algorithm consistently outperforms others in terms of stability, showing lower standard deviations across multiple trials. This reliability in producing consistent results makes it an ideal choice for photovoltaic modeling applications. The comparison also shows that algorithms like ALO and STOA, though faster in some cases, sacrifice accuracy for speed, making them less suitable for tasks that require high precision, such as modeling the behavior of the Photowatt-PWP201 cell. Overall, the m_YDSE algorithm’s performance highlights its suitability for accurate and stable SDM-based parameter estimation in photovoltaic systems

Experiments on Double-Diode model (DDM)-based Photowatt-PWP201

Table 7 presents a comparison of various algorithms applied to the Photowatt-PWP201 solar cell using the Double Diode Model (DDM). The table evaluates parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation currents (\(I_{01}\) and \(I_{02}\)), and non-ideality factors (A1 and A2). Additional performance metrics such as the root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are also included. The best performance is observed with the VYSE algorithm, which achieved the lowest RMSE value of 0.000867, while the worst performance is seen with the ALO algorithm, which had an RMSE value of 0.013020. This table highlights the effectiveness of each algorithm in modeling the solar cell characteristics under different conditions.

The fill factor for the YDSE-DE algorithm is 0.66848, which is slightly higher than other algorithms. This improvement further supports the YDSE-DE algorithm’s effectiveness in enhancing the efficiency of photovoltaic models.

Figure 10 demonstrate the performance of various algorithms based on the Double Diode Model (DDM) for the Photowatt-PWP201 solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm achieves lower RMSE values compared to other algorithms, showcasing its effectiveness in minimizing error and enhancing the accuracy of parameter estimation. While some algorithms, such as STOA and SOA, perform well in terms of convergence speed, the m_YDSE algorithm strikes a better balance between precision and stability, outperforming others across multiple trials. This highlights its suitability for scenarios requiring high accuracy in photovoltaic modeling.

The P-V and I-V characteristics generated by m_YDSE closely match the experimental data, validating its reliability in accurately modeling the performance of the solar cell. The lower standard deviation observed with m_YDSE further underscores its robustness, providing consistent results over multiple iterations. While faster algorithms may be preferred for time-sensitive applications, the superior accuracy of m_YDSE makes it ideal for detailed modeling tasks where precision is paramount.

Experiments on Triple-Diode model (TDM)-based Photowatt-PWP201

Table 8 provides a comparative analysis of algorithms using the Photowatt-PWP201 solar cell with the Three Diode Model (TDM). This table includes parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), and additional parameters unique to the three diode setup, including multiple diode saturation currents (\(I_{01}\), \(I_{02}\), \(I_{03}\)) and non-ideality factors (A1, A2, A3). Performance metrics like RMSE, fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are used to assess the algorithms. The VYSE algorithm achieved the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.000978, while the ALO algorithm had the worst performance, with an RMSE value of 0.012883. The table provides a comprehensive evaluation of each algorithm’s capability to accurately model solar cell behavior across various scenarios. Regarding FF ; In this comparison, the YDSE-DE algorithm achieves a high fill factor value, which is an indication of the algorithm’s ability to optimize the solar cell’s performance efficiently.

Figure 11 compares the performance of various algorithms using the Triple Diode Model (TDM) for the Photowatt-PWP201 solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm exhibits strong performance, achieving lower RMSE values than competing algorithms such as ALO, STOA, and SOA. Despite a slightly slower convergence compared to some alternatives, m_YDSE reaches a more accurate solution, reflected in its close alignment with experimental P-V and I-V characteristics. This demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to accurately model the behavior of the solar cell under TDM-based conditions.

Moreover, the statistical analysis across multiple trials reveals that m_YDSE consistently produces stable and reliable results, with lower standard deviations compared to other algorithms. This consistency underscores its robustness in achieving optimal parameter estimation. In scenarios where precision is critical, such as detailed solar cell modeling, the superior accuracy of m_YDSE makes it a preferred choice over faster but less accurate algorithms.

Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W

Experiments on Single-Diode model (SDM)-based Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W

Table 9 presents a comparative analysis of various algorithms applied to the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell using the Single Diode Model (SDM). The table evaluates parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation current (\(I_0\)), and non-ideality factor (A). Performance metrics like root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are also included. The m_YSDE algorithm demonstrated the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.001947, while the ALO algorithm showed the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.010509. The table provides insights into the effectiveness of each algorithm in accurately modeling the characteristics of the Kyocera KC200GT solar cell under different conditions. The fill factor for YDSE-DE is 0.76342, which is higher than the values for other algorithms. This indicates the efficiency of the YDSE-DE algorithm in optimizing the solar cell’s performance.

In Fig. 12, a comparison between algorithms based on the Single Diode Model (SDM) for the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell reveals that the m_YDSE algorithm consistently delivers superior performance in terms of accuracy. The m_YDSE algorithm achieves the lowest RMSE values compared to others like ALO and STOA, indicating higher precision in parameter estimation. The convergence curve (Fig. 12-a) illustrates that while some algorithms, such as STOA and SOA, converge slightly faster, m_YDSE ultimately outperforms them in accuracy after reaching a stable solution.

The P-V and I-V characteristics (Fig. 12b,d) further demonstrate the close alignment between the experimental data and the values predicted by m_YDSE, solidifying its reliability in modeling the electrical behavior of the solar cell. The algorithm’s lower standard deviation across multiple trials emphasizes its consistency, making it the preferred choice for applications that prioritize accuracy and stable performance over mere convergence speed. In summary, the m_YDSE algorithm offers a robust balance of precision and reliability, outperforming other algorithms in this particular case.

Figure 12c presents the minimum fitness values (root mean square error, RMSE) achieved by different algorithms applied to the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell using the Single Diode Model (SDM). The results highlight the m_YDSE algorithm’s exceptional performance, consistently yielding the lowest RMSE across multiple trials, thereby indicating its superior accuracy in parameter estimation.

The results affirm that the m_YDSE algorithm not only outperforms its competitors in terms of accuracy but also provides a stable and reliable framework for the estimation of solar cell parameters. This makes it an ideal choice for future applications in photovoltaic system simulations and optimizations

Experiments on Double-Diode model (DDM)-based Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W

Table 10 presents a comparison of various algorithms applied to the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell using the Double Diode Model (DDM). The table evaluates key parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation currents (\(I_{01}\) and \(I_{02}\)), and non-ideality factors (A1 and A2). Additional performance metrics like root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are also included. The best performance is achieved by the VYSE algorithm with the lowest RMSE value of 0.000717, while the worst performance is noted for the ALO algorithm with an RMSE value of 0.018795. This table provides a detailed analysis of the algorithms’ effectiveness in modeling the solar cell characteristics under various conditions. The fill factor for YDSE-DE is 0.76342, which is the highest among the algorithms tested, confirming that it optimizes both the accuracy and efficiency of the solar cell.

Figure 13 compares various algorithms for parameter estimation using the Double Diode Model (DDM) for the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm consistently demonstrates superior performance, achieving lower RMSE values than other algorithms like ALO, SOA, and STOA. The convergence curve shows that while some algorithms may converge more quickly, m_YDSE ultimately reaches a more accurate solution after several iterations. This trade-off between convergence speed and accuracy highlights m_YDSE’s effectiveness in precise parameter estimation.

Moreover, the P-V and I-V characteristics generated by m_YDSE show close alignment with experimental data, reinforcing the algorithm’s reliability in accurately modeling the behavior of the Kyocera KC200GT solar cell under the DDM. The lower standard deviation in the results indicates the stability of m_YDSE across multiple trials, making it an ideal choice for applications where accuracy and consistency are crucial. The algorithm outperforms others in terms of both precision and robustness, proving to be a highly reliable tool for DDM-based solar cell modeling .

Experiments on Triple-Diode model (TDM)-based Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W

Table 11 provides a comparative evaluation of algorithms using the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell with the Three Diode Model (TDM). This table includes parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), and additional parameters unique to the three diode setup, including multiple diode saturation currents (\(I_{01}\), \(I_{02}\), \(I_{03}\)) and non-ideality factors (A1, A2, A3). Performance metrics like RMSE, fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are used to assess the algorithms. The VYSE algorithm demonstrated the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.000806, while the ALO algorithm had the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.014392. The table provides insights into each algorithm’s capability to accurately model the solar cell behavior across different scenarios. The YDSE-DE algorithm achieves a competitive fill factor value, which is higher compared to other algorithms tested in this table.

In Fig. 14, the comparison between algorithms based on the Triple Diode Model (TDM) for the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell demonstrates that the m_YDSE algorithm provides the lowest RMSE values, showcasing superior performance in parameter estimation compared to other algorithms like ALO, SOA, and STOA. Although the m_YDSE algorithm requires more iterations to converge compared to some faster alternatives, its final accuracy is significantly better, particularly in matching the experimental P-V and I-V characteristics, highlighting its precision in modeling solar cell behavior.

Additionally, the m_YDSE algorithm’s lower standard deviation values across trials further emphasize its consistency and robustness in generating stable results. Other algorithms, such as ALO and SOA, are shown to be quicker but less accurate, making them less suitable for applications requiring high precision. The m_YDSE algorithm’s balance of accuracy and reliability makes it the optimal choice for Triple Diode Model-based photovoltaic modeling of the Kyocera KC200GT solar cell.

Figure 15 presents a comparison of the runtime for different algorithms applied to the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm, while generally achieving the highest accuracy in previous comparisons, exhibits a slightly longer runtime compared to faster algorithms such as ALO, STOA, and RSO. This increased computational time is expected due to the more thorough and comprehensive search mechanism employed by m_YDSE, which prioritizes accuracy and precision in parameter estimation over speed.

However, it is important to note that while faster algorithms like STOA and RSO offer quicker runtimes, they tend to compromise on the precision of the results, as seen in their performance in previous figures. The trade-off between runtime and accuracy is evident here, where m_YDSE’s slower runtime is compensated by its superior performance in delivering precise solar cell parameter estimations. Therefore, while not the fastest, m_YDSE remains the preferred algorithm for applications where accuracy is paramount .

Ultra 85-P cell

Experiments on Single-Diode model (SDM)-based Ultra 85-P Cell

Table 12 provides a comparative analysis of several algorithms applied to the Kyocera KC200GT - 204.6 W solar cell using the Single Diode Model (SDM). The table evaluates key parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation current (\(I_0\)), and the non-ideality factor (A). Additionally, performance metrics like root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are considered. The m_YSDE algorithm achieved the best results, with the lowest RMSE value of 0.0034427, while the RSO algorithm exhibited the worst performance with an RMSE of 0.18333. The table highlights the effectiveness of each algorithm in accurately modeling the characteristics of the Ultra 85-P solar cell under varying conditions. The fill factor for YDSE-DE is 0.76406, higher than that of other algorithms. This shows the optimization algorithm’s ability to balance both accuracy and efficiency.

Figure 16 compares the performance of various algorithms using the Single Diode Model (SDM) for the Ultra 85-P solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm demonstrates superior accuracy with lower RMSE values compared to other algorithms like ALO, STOA, and SOA. The convergence curve shows that while m_YDSE may take slightly longer to reach optimal performance, it ultimately delivers the most accurate solution. The P-V and I-V characteristics predicted by m_YDSE closely match the experimental data, confirming its precision in modeling the electrical behavior of the Ultra 85-P cell.

In addition, the lower standard deviation values across multiple trials reinforce the algorithm’s stability and reliability. While some algorithms may offer faster convergence, m_YDSE strikes a balance between speed and precision, making it the most suitable option for accurate photovoltaic modeling. Its robust performance in terms of both accuracy and consistency highlights the advantages of using m_YDSE for SDM-based solar cell parameter estimation .

Experiments on Double-Diode model (DDM)-based Ultra 85-P Cell

Table 13 presents a comparison of various algorithms applied to the Ultra 85-P solar cell using the Double Diode Model (DDM). The table evaluates key parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation currents (\(I_{01}\) and \(I_{02}\)), and non-ideality factors (A1 and A2). Additional performance metrics like the root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are also included. The VYSE algorithm demonstrated the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.000895, while the ALO algorithm had the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.012099. This table provides a detailed analysis of the algorithms’ effectiveness in modeling the solar cell characteristics under different conditions. The fill factor for YDSE-DE is 0.76046, which is the highest among the algorithms tested, showing that YDSE-DE achieves optimal efficiency while minimizing error.

In Fig. 17, which compares algorithms based on the Double Diode Model (DDM) for the Ultra 85-P solar cell, the m_YDSE algorithm consistently outperforms other algorithms in terms of accuracy, as indicated by its lower RMSE values. The convergence curve (Fig. 17a) demonstrates that while some algorithms may converge faster, m_YDSE achieves superior accuracy after stabilizing, making it a highly reliable choice for precise parameter estimation in DDM-based models. Its ability to closely match the experimental data, especially in the P-V and I-V characteristics (Fig. 17b,d), underscores its effectiveness in modeling the electrical behavior of the Ultra 85-P cell.

Furthermore, m_YDSE shows remarkable consistency across multiple trials, as reflected by its lower standard deviation values. This reliability makes it stand out as the best algorithm for applications that prioritize both accuracy and stable performance in photovoltaic modeling. While other algorithms, such as STOA and SOA, may offer faster runtimes, m_YDSE’s precision and consistency make it the preferred choice for DDM-based simulations where accurate performance predictions are crucial

Experiments on Triple-Diode model (TDM)-based Ultra 85-P

Table 14 provides a comparative evaluation of algorithms using the Ultra 85-P solar cell with the Three Diode Model (TDM). The table includes parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), and additional parameters unique to the three diode setup, including multiple diode saturation currents (\(I_{01}\), \(I_{02}\), \(I_{03}\)) and non-ideality factors (A1, A2, A3). Performance metrics like RMSE, fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)) are used to assess the algorithms. The VYSE algorithm demonstrated the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.000947, while the ALO algorithm showed the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.010949. This table provides insights into each algorithm’s capability to accurately model the solar cell behavior under different conditions. The YDSE-DE algorithm demonstrates a competitive fill factor value of 0.76418, which is higher than those achieved by other algorithms.

The fill factor for YDSE-DE indicates a highly efficient solar cell, suggesting that the algorithm optimizes the performance of the Ultra 85-P solar cell effectively. Although minor fluctuations in FF are observed across different algorithms, these variations are inherent in stochastic optimization processes and do not detract from the overall performance of the YDSE-DE algorithm.

In Fig. 18, which compares various algorithms based on the Triple Diode Model (TDM) for the Ultra 85-P solar cell, the m_YDSE algorithm consistently demonstrates superior performance by achieving lower RMSE values compared to other algorithms such as ALO, STOA, and SOA. Although m_YDSE takes slightly longer to converge than some of the faster algorithms, it reaches a more accurate solution after stabilization. This highlights its strength in balancing convergence time and precision, making it a highly effective choice for TDM-based parameter estimation tasks.

The P-V and I-V characteristics generated by m_YDSE show a strong alignment with the experimental data, confirming its reliability in accurately modeling the electrical behavior of the Ultra 85-P cell. Moreover, the m_YDSE algorithm exhibits lower standard deviations across multiple trials, reinforcing its stability and robustness in producing consistent results. While some algorithms may provide faster runtimes, the accuracy and consistency of m_YDSE make it the preferred choice for detailed modeling tasks involving the Triple Diode Model .

Figure 19 presents a comparison of runtime between various algorithms when applied to the Ultra 85-P solar cell. The m_YDSE algorithm, known for its superior accuracy in previous figures, exhibits a longer runtime compared to faster alternatives such as STOA and ALO. This longer runtime is a result of the m_YDSE algorithm’s more thorough search process, which prioritizes accuracy over speed. Despite its slower convergence, the improved precision offered by m_YDSE in estimating the solar cell parameters justifies its additional computational cost, particularly in applications requiring detailed parameter estimations.

In contrast, algorithms like STOA and ALO offer significantly shorter runtimes but sacrifice some degree of accuracy. These faster algorithms might be more suitable for scenarios where speed is essential, but they may not achieve the same level of precision as m_YDSE. The trade-off between runtime and accuracy is evident here, with m_YDSE being the ideal choice for tasks where accuracy outweighs the need for quick convergence .

STP6-120/36 module

Experiments on Single-Diode model (SDM)-based STM6-40/36 module

Table 15 presents a comparison of various algorithms applied to the STP6-120/36 module using the Single Diode Model (SDM). The table evaluates parameters such as the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), diode saturation current (\(I_0\)), non-ideality factor (A), and other performance metrics like the root mean square error (RMSE), fill factor, and maximum power point (\(P_{\text {max}}\)). The VYSE algorithm achieved the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.001239, while the ALO algorithm showed the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.005424. The table provides an analysis of these algorithms under various conditions, highlighting their accuracy and effectiveness in modeling solar cell characteristics. FF In the STP6-120/36 module optimization, the YDSE-DE algorithm achieves a competitive FF value, which is crucial for understanding the energy conversion efficiency of the module.

In Fig. 20, the comparison between various algorithms applied to the STP6-120/36 module using the Single Diode Model (SDM) reveals that the m_YDSE algorithm excels in minimizing RMSE compared to other optimization techniques such as ALO, SOA, and STOA. The m_YDSE algorithm achieves the lowest RMSE value, which is indicative of its superior accuracy in predicting the parameters of the solar cell. The convergence curve demonstrates that m_YDSE, though not the fastest to converge, ultimately reaches the most precise solution after several iterations, emphasizing its robustness in balancing both speed and accuracy.

The P-V and I-V characteristics generated by m_YDSE exhibit a close match with the experimental data, reinforcing the algorithm’s ability to model the electrical behavior of the STP6-120/36 module accurately. In addition to its high accuracy, m_YDSE consistently shows lower standard deviations across trials, highlighting its reliability. While other algorithms may offer quicker results, m_YDSE’s balance of precision and consistency makes it the preferred choice for SDM-based photovoltaic modeling

Experiments on Double-Diode model (DDM)-based USTM6-40/36 Cell

Table 16 compares the performance of different algorithms when applied to the STP6-120/36 module using the Double Diode Model (DDM). The table lists key electrical parameters including the short-circuit current (\(I_{\text {sc}}\)), open-circuit voltage (\(V_{\text {oc}}\)), series resistance (\(R_s\)), and shunt resistance (\(R_{\text {sh}}\)), as well as additional parameters specific to the double diode configuration, such as the second diode saturation current (\(I_{02}\)) and its non-ideality factor (A2). The VYSE algorithm demonstrated the best performance with the lowest RMSE value of 0.001380, while the ALO algorithm showed the worst performance with an RMSE value of 0.007317. This table provides insights into the accuracy and stability of each algorithm in modeling solar cell behavior under various scenarios.