Abstract

Irrigation with water containing ultrafine bubbles (UFB) promotes crop growth under environmental stress conditions. This study evaluated the changes in soil physical properties when using low-cost UFB for paddy field irrigation. An experimental paddy field was divided into eight sections, with regular agricultural (control) and UFB irrigation, and rice cultivation was conducted over three seasons. The findings indicate that the sand content, linked to the fragmentation of gravel, increased 2.6% due to UFB irrigation over two years. A one-week stirring experiment was conducted in the laboratory to observe the accelerated fragmentation of the soil particles. A UFB containing distilled water significantly decreased the sand content by 3.5–7.1% and increased the clay content by 5.3–5.6% compared to the control distilled water. The thickness of the viscous colloidal layer on the soil surface increased by a maximum of 29 mm, and the penetrometer resistance decreased with UFB irrigation under submerged paddy conditions. These results indicated that continuous irrigation with low-cost UFB water from air and agricultural water promotes soil particle fragmentation and reduces soil penetrometer resistance. This study provides valuable insights into the potential benefits and limitations of UFB irrigation in sustainable agricultural practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultra-small-sized air bubbles, commonly known as ultra-fine bubbles (UFBs), are defined as air bubbles with an average diameter of less than 1 μm (ISO 20480-1: 2017), and possess several unique physical characteristics when formed in water. For instance, the inertial force resulting from Brownian motion exceeds the buoyancy of UFBs, allowing them to remain suspended for extended periods1. They additionally possess a strong bursting force because of their high internal pressure2. UFBs have been recognized for their effectiveness in cleaning various materials3,4,5 and for their sterilization capabilities6 within industrial applications. Some experiments have been conducted to explore the potential applications of UFBs in agricultural crop and livestock production7. Studies conducted under strictly controlled conditions using field crop species have indicated that UFB water alleviates low nutrient stress8 and high osmotic pressure stress9. The concentrations of UFBs that contribute to stress alleviation differ among specific field crop species, such as Gramineae and legumes10. Therefore, fundamental research has demonstrated that UFB water can mitigate environmental stress within a specific UFB concentration range.

Previous studies on the effect of UFB water on crop productivity have utilized UFBs generated with oxygen11 or nitrogen12; however, the preparation of oxygen or nitrogen UFB water is costly and poses practical challenges for widespread implementation. Therefore, investigating crop cultivation with low-cost UFBs derived from ambient air for agricultural irrigation is essential for the practical application of UFB water. Single-year field trials have indicated that the low-cost UFB water derived from ambient air and agricultural water enhanced nutrient and water absorption capacities of paddy fields13 and that UFB water has the potential to clean paddy field water14. According to previous studies, detailed descriptions can be found in terms of the effects of UFB on soil microbial activity11,15 and soil chemical properties16. With microbial activity, it has been reported that the population of methanogenic archaea tends to decrease, while an increase in cations has been noted for chemical properties. On the other hand, there appear to be no published studies that specifically discuss the physical properties of soil in terms of UFB. In the case of upland crops, UFB irrigation is generally applied only for a limited period, and, therefore, its impact on physical properties may be minimal. In case of submerged paddy fields, rice roots and field soils are exposed to the irrigation water for prolonged periods as compared to the upland fields. Furthermore, it may be possible to detect effects on soil physical properties if exposure continues over multiple years rather than just a single year. However, no studies have examined the effects of multi-year UFB irrigation on field soils and rice growth.

Soil particle size distribution is a fundamental physical property of soil that influences several important soil characteristics17. That in agricultural land is affected by factors such as soil erosion, tillage practices, and natural processes. Root penetration is also often associated with soil fragmentation, as it creates zones of mechanical failure, thereby inducing soil loosening and aggregate formation18. Soil erosion frequently occurs in sloped farmlands, and agricultural practices such as no-tillage can reduce soil loss19. The loss of fine particles, particularly clay and silt, is a major cause of soil coarsening and increased heterogeneity in sloped fields20. Continuous tillage practices are known to promote soil fragmentation, and natural processes such as wetting and drying also contribute to this phenomenon. The fragmentation of soil particles may be caused by physical, chemical, or biological processes21. A long-term field experiment22 has suggested that changes in particle size distribution under stable agricultural practices occur only over extended periods. For example, more than 100 years of contrasting fertilization treatments in the Askov long-term experiment revealed no significant changes in particle size distribution among treatments—unfertilized, NPK mineral fertilized, and animal manured22. This implies that soil particle size distribution changes require a considerable amount of time under stable conditions. In contrast, changes in particle size composition can occur over about a few decades in newly developed farmland. Su et al. (2010)23 reported that significant changes in particle size distribution were observed in previously uncultivated desert soils after 14 or 23 years. This may be attributed to increased soil disintegration due to tillage and intensive soil amendment practices.

Clay particles are typically formed by the weathering and erosion of parent rocks over geological timescales24. Considering the diverse real-world applications of UFB in cleaning technologies, it is plausible that UFB may also have the potential to modify the physical properties of agricultural soils. If UFB indeed exerts a significant influence, short-term changes in particle size distribution may be achievable, potentially contributing to soil improvement. In this study, we focused on submerged paddy field environments where both crops and soil are continuously exposed to UFB irrigation over an extended period. In such conditions, crop roots are continuously exposed to UFB-treated water. Previous studies under hydroponic conditions have reported marked promotion of root elongation by UFB8,9,10, suggesting that investigating belowground growth responses under paddy conditions is of considerable value.

Water in field soil shifts toward the soil surface due to evapotranspiration during the day and moves downward (in accordance with gravity) at night. This cycle suggests that water repeatedly travels along the same pathways via capillary connections within the soil. The crystal structure of clay minerals consists of a layered structure comprising a tetrahedral sheet and an octahedral sheet that share some O2- ions25. When water with high concentrations of UFBs passes through the same location daily, the fragile components of the clay mineral crystal structure may be stripped away.

Nowadays, UFB-equipped showerheads and household washing machines have become popular consumer products26. These societal applications of UFBs in the cleaning sector can be related to the effect of stripping away fragile components of the molecular structure of soil particles if UFB is continuously irrigated in a paddy field. Consequently, we hypothesized that the UFB irrigation may accelerate the natural soil weathering process. In this study, we examined the long-term impact of low-cost UFBs derived from agricultural water (hereafter UFB) irrigation on crop yield and soil physical properties in paddy fields, given its physicochemical effects on the soil. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of continuous UFB irrigation over three years on soil physical properties and rice growth in paddy fields.

Methods

Plant material and experimental design (three years field experiment)

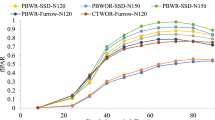

A paddy field (40 m × 20 m) located at the University of Shiga Prefecture (35°15’25” N, 136°21’54” W, Hikone, Shiga, Japan) was divided into eight Sect. (17.8 m × 4.9 m) using corrugated plastic plates (Aze sheet, 0.5 mm thick, 300 mm high). The soil type is classified as Gleyic Stagnosol27, and the soil chemical properties are presented in Table 1. Agricultural water pumped up from Lake Biwa was used for rice irrigation. Control (no-UFB) and UFB plots were prepared using the agricultural water and ambient air through a UFB generator (2 W, Eatech Co., Ltd, Kumamoto, Japan) with four replications (Fig. 1). The control plot was irrigated using a pump equivalent to the UFB generator to equalize the irrigation water volume in both plots14. The UFB particle densities in the irrigation water of the control and UFB plots, measured using a laser-particle density analyzer (NanoSight LM10, Malvern Panalytical, Tokyo, Japan), were 0.117 ± 0.040 × 108 and 5.13 ± 0.446 × 108 ml−1, respectively. The distribution of number density by UFB size is presented in Fig. 2. UFB sizes are continuous and largely dependent on the characteristics of the generation device. The number density of UFBs may be increased by circulating the solution within the generator9. However, in the present study, it was not feasible to circulate agricultural irrigation water through the device. Therefore, UFB treatment was limited to a single pass through the generator.

An overview of the cultivation process is presented in Table 2. The rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. Nipponbare) was mechanically transplanted at a density of 30 cm (furrow) × 21 cm (row), averaging three plants per hill. A slow-release chemical fertilizer (N: P2O5:K2O = 20:7:10 in 2021 and 20:12:14 in 2022 and 2023) was simultaneously applied side-rowed at 400 kg ha⁻¹ each year in line with conventional practices. Mid-season drying and intermittent irrigation during the rice growth period were not conducted in the present study. In both treatments, standing water was maintained between 5 and 10 cm in depth via repeated pump irrigation (Fig. 3). Disease, pest, and weed control practices were carried out according to conventional cultivation methods.

Soil particle size distribution

Sampling was conducted after the completion of two cropping seasons to avoid progressive disturbance and degradation of the limited experimental plots caused by frequent soil sampling. Top soil (0–10 cm) was sampled on April 23, 2023, immediately prior to the start of water irrigation for the third crop season. The surface soil was collected from the center and intermediate points extending from the center to the four corners of each plot. The soil samples were air-dried and subsequently analyzed for particle size distribution28 to determine the proportions of sand, silt, and clay. The compositional classification and soil properties were assessed according to the International Soil Science Society29. In addition, approximately 50 g of air-dried soil, free from gravel, was placed in 200 mL of either control or UFB prepared from deionized water. The soils were then shaken and mixed at 1.7 Hz for one week using a soil shaker (DIK-2102, Daiki Rika Kogyo Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan). The soils were oven-dried at 110 °C for 24 h, after which the particle size distributions were measured. Soil particle density was also measured using the pycnometer method.

Soil penetration resistance

During the 2023 cropping season, six measuring points were established in a row at 2.5 m intervals in the center of each plot after completing two-year rice cultivation using UFB irrigation. In total, penetration resistance values were obtained at 200 points, with eight experimental plots, five measurement points per plot, and five measurement dates. As most of the measurements were conducted under flooded conditions during rice cultivation, we intentionally did not perform continuous soil core sampling from the topsoil to the subsoil. This decision was made in consideration of the constraints of the cultivation experiment. The soil mechanical impedance was measured at six different timings using a penetrometer (DIK-5532, Daiki Rika Kogyo Co., Ltd., Saitama, Japan) under varying soil conditions—dry soil conditions before flooding (April 20), before puddling (May 1), one month after transplanting (June 8), at the maximum tillering stage (July 18), at the heading stage (August 23), and immediately before harvesting two weeks after drainage (September 29). On April 20 and September 29, the fields were dry, whereas the soil remained submerged on May 1, June 8, and August 23. The surface soil was intermittently exposed to air on July 18 (maximum tillering stage) due to the absence of rainfall (Fig. 3).

Rice growth and yield evaluation

The plant height and stem number of representative plants were measured during the growth period. Root sampling was conducted from September 13 to 15 in 2021, and from September 7 to 9 in 2022. In 2021, the profile wall method was employed to determine the depth of the deepest roots. A soil profile 40 cm perpendicular to the paddy rice rows and 40 cm directly below the plants was excavated. The cross-section was washed with tap water, the soil adhering to the roots was carefully removed with tweezers, and the position of the deepest root was measured. A 100 ml soil sampling cylinder was inserted perpendicularly into the cross-section to collect the soil. Soil samples were collected from two locations: near the base of the plant and directly beneath the inter-row space, at a depth of 7–12 cm to measure root biomass. In 2022, a soil sample cylinder (300 mm in height and 50 mm in diameter; HS-30 S, Fujiwara Scientific Co. Ltd.) was used to collect soil samples (30 cm depth) from four locations within each plot— directly beneath the plant, between plants, between rows, and at the center of the diagonal lines. After sampling, the soil was divided into two layers—an upper layer extending from the surface to 10 cm depth and a lower layer extending from 11 cm to 20 cm depth. The soil samples were washed through a mesh to eliminate debris, and root dry weight was measured. A total of 50 plants per plot were harvested on October 1, 2021, and October 5, 2023 to measure seed yield and its components. Similarly, 60 plants were harvested per plot on October 3, 2022.

Statistical analysis

Welch’s t-test was used to compare the mean values of the control and UFB plots. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effects of the year and water and their interaction effects on the yield and its components.

Results

Soil particle size distribution

Table 3 presents the particle size distributions of paddy soils irrigated with UFB over two years. The soil texture classification remained consistent for both plots. When considering the soil particle distribution inclusive of gravel, the UFB presented a 2.8% decrease in gravel content relative to the control (p < 0.1), while the UFB exhibited a significantly higher sand content in the case without gravel (p < 0.05). These results suggested that the soil particles were more fragmented. To further investigate this, paddy soils devoid of gravel were continuously shaken for one week to accelerate soil particle fragmentation artificially (Table 4). Both the control and UFB plot soil samples exhibited a downward trend in soil particle size due to continuous shaking; however, the particle size distribution differed significantly depending on the solvent (control or UFB). Shaking in UFB resulted in a significant decrease in sand content and a significant increase in clay content compared with shaking in deionized water. The control soil sample exhibited a 7.8% significant decrease in sand content and a 5.3% increase in clay content. In the UFB plot soil sample, the sand content decreased by 3.5% while the clay content increased by 5.1%. The reduction in sand content was smaller in the UFB plot than in the control plot.

Soil penetration resistance

Figure 4 illustrates the vertical distribution of soil penetration resistance measured six times during the cultivation period. Throughout the continuous soil flooding period from puddling to three weeks before rice harvest (April 21 to September 14, 116 days; Table 2), the UFB plot showed lower soil penetration resistance than the control plot. In contrast, no differences were observed between the treatments on July 18 (Fig. 4d). Two weeks after drainage, the penetration resistance near the soil surface was approximately 300 kPa (Fig. 4f) on September 29, indicating that the soil had begun to harden due to surface drying. No distinct different phenomena were observed between control and UFB plots under drier conditions, either before flooding or two weeks after drainage. In paddy soils, continuous flooding creates a fine and viscous muddy soil layer (colloidal layer) at the soil surface30. The depth at which penetration resistance was nearly zero (0–0.75 kPa) corresponded to that of the colloidal layer during the flooding period (Table 5). The thickness of the colloidal layer gradually decreased after puddling, although no quantitative difference was observed up to one month before heading (July 18). Conversely, the colloidal layer in the UFB plot was significantly thicker by 2.9 cm during the heading period (August 23). The application of UFB appeared to increase colloidal materials in the soil, resulting in a tendency for the soil to become softer when moist and to harden more firmly during drying prior to puddling (Fig. 4).

Rice growth

Regarding plant height and stem number, the UFB plot temporarily exceeded those of the control plot at the early vegetative growth stage up to one month before heading in 2021; however, no significant growth promotion was noted in both 2022 and 2023 (Fig. 5). The final plant height and stem number remained consistent across all three years. In 2021, the UFB plot had a significantly greater root depth than the control plot. Nevertheless, root biomass did not show any significant differences across all years (Table 6). Regarding the yield components, the number of spikelets per panicle was significantly lower in the UFB plot, whereas no significant differences were observed in the other yield components (Table 7). The final seed yield did not differ significantly between the control and UFB treatments.

Discussion

Soil particle fragmentation

The results of this study provide the first empirical evidence indicating that continuous flooding with UFB may induce the fragmentation of soil particles in paddy fields. Ultra-small nanoscale UFBs can penetrate the cracks of large particles, such as gravel, potentially facilitating their detachment and increasing sand particles (Table 3). Theoretically, UFB should uniformly affect soil particles of all size fractions, suggesting an increase in finer soil particles. However, in the present study, silt and clay presented a decreasing trend, with the reason for this remaining unclear. Considering the ambiguous behavior of soil particles in the field soil, accelerated soil fragmentation was attempted by shaking the samples for one week in the laboratory. Shaking with UFB significantly reduced the sand content by 3.5–7.1% and increased the clay content by 5.3–5.6% compared to shaking with deionized water (Table 4). This suggested that the fragmentation of soil particles with UFB irrigation was further enhanced by shaking in the laboratory.

Clay particles are formed by the weathering and erosion of soil-containing rocks over extended periods24. Based on the results of UFB water infiltration into soil, it may be inferred that UFB promotes soil particle refinement (finer particle formation). Therefore, it is suggested that a significant increase in clay particles in paddy soil can occur after several years of UFB irrigation. When UFB irrigated soil samples were shaken with UFB, the sand content demonstrated a decreasing trend compared to the control soil samples (Table 4). This implies that sand grains partially became more fragile after two years of UFB irrigation, similar to the collapse of gravel. Consequently, sand particles were more easily disintegrated by shaking with control distilled water, suggesting a potential reduction in sand particle size due to UFB.

Soil physics and crop growth

The cohesive and adhesive forces between soil particles tend to decrease in flooding paddy soils. The colloidal layer described in Table 5 corresponds to the surface zone in Fig. 4b–e where the penetration resistance approaches zero. This indicates extremely low soil bulk density, which results in near-zero resistance in the uppermost layer. However, below the colloidal layer, soil density gradually increases; thus, even under submerged conditions, penetration resistance also increases. Previous studies on the hardness of paddy soil32,33 have shown that penetration resistance varies depending on age hardening and the degree of soil disturbance, such as puddling intensity. In relation to the phenomenon of soil fragmentation due to UFB irrigation, we measured soil penetrometer resistance, which can influence rice root growth. The fragmentation of soil particles can partially expand the capillary pores, facilitating the penetration of rice roots and resulting in a deeper maximum root penetration depth (Table 6). The root elongation rate is inversely proportional to the mechanical resistance of the soil34. The reduction in penetrometer resistance explains deeper root penetration. Furthermore, UFB promotes root elongation8,9,10 under various environmental stress conditions. In the present study, no significant difference was observed in root biomass itself. However, a significant difference observed in root penetration depth suggests that root elongation itself was promoted. Nevertheless, this did not result in a quantitative increase in biomass through the development of higher-order lateral root branching34. The present paddy field experiment suggests that root elongation may be enhanced by temporal and/or minor environmental stresses, such as high temperatures in the root zone during summer or temporal nutrient deficiency in the rooting zone. Root elongation may also correlate with increase in plant height in case of the 2021 experiment (Fig. 5). During the soil flooding period, no difference in penetrometer resistance was observed between treatments on July 18, (Fig. 4). This period corresponds to the maximum tillering stage and the highest temperature of the year, occurring one month before heading. At this time, rice absorbs the largest amount of soil water during its lifetime36. Moreover, no rainfall was observed around July 18 (Fig. 3). Because of the higher water absorption rate and large amount of evapotranspiration during mid-summer, parts of the soil surface became visible just before irrigation. In other words, the soil temporarily resembled dryland soil, potentially elucidating the lack of differences in penetrometer resistance between the treatments.

In paddy fields, a suspended colloidal layer is formed on the soil surface during continuous flooding30. The depth of this colloidal layer was significantly increased by 2.9 cm in the UFB plot during the heading stage (August 23) (Fig. 4). Rice superficial roots, which extended into the colloidal layer, were observed around the heading stage, and the superficial roots were related to the yield potential37. However, UFB irrigation did not significantly affect yield and yield components, except for the number of spikelets per panicle (Table 7). The number of spikelets per panicle was determined between the panicle initiation stage (one month before heading) and the heading stage37. During this period, the plant height, stem number, and root penetration depth in the UFB plot were greater than those in the control plot (Fig. 4; Table 6). These results suggest that the growth of vegetative parts, both above- and below-ground, was promoted, which may have led to a reduction in the reproductive parts and the number of spikelets. However, at the end of vegetative organ growth, the final plant height, stem number, and root dry mass remained unaffected by UFB irrigation. These findings indicate that three years of UFB irrigation in the paddy field did not affect rice growth and yield, whereas soil particle fragmentation gradually increased.

Limitations of the present study

The advancement of this technology may lead to cost-effective soil improvement. Moreover, the study underscores the need for further long-term and multiyear research to fully understand the cumulative effects of UFB irrigation on soil properties and crop productivity. Soil saturated hydraulic conductivity, soil organic matter content, sand fraction, and plant roots are known to promote the formation and development of preferential flow39. Therefore, continued irrigation with UFB may lead to changes in preferential flow over time. Chemical fertilizers were applied sufficiently in this experiment, providing nutrient-rich conditions throughout the study. Under such favorable conditions, it can be reasonably concluded that there were no significant differences in yield. However, rice plants are subjected to various environmental stresses, such as temperature fluctuations and nutrient limitations in actual paddy fields. For instance, plant growth has been reported to improve when UFB is applied under nutrient-deficient conditions8. The observed trend of increased yield in the first year of this study may also be attributed to the lower solar radiation observed that year, which could have imposed light stress. Considering previous fundamental research findings8,9,10, it is plausible that UFB irrigation may enhance yields in nutrient-poor paddy fields without chemical fertilizer input. Rice farmers who prefer organic farming do not necessarily use chemical fertilizers. Therefore, the potential effectiveness of UFB irrigation in such fields remains uncertain, warranting future studies under fertilizer-free conditions. Increased root-soil contact is expected as soil fragmentation progresses, which could enhance nutrient accumulation and retention, ultimately improving nutrient uptake efficiency. Such changes may also influence evapotranspiration at the canopy level40,41, potentially leading to improved water use efficiency in rice cultivation. Further, investigating the impact of UFB on soil chemical and microbial communities under diverse filed conditions can provide a more comprehensive understanding of UFB irrigation benefits.

Conclusion

Applying UFB-containing agricultural water generated with ambient air to irrigate paddy fields resulted in promoted root elongation. In addition, three years of UFB irrigation decreased the number of grains per panicle. Moreover, two years of UFB irrigation promoted the fragmentation of gravel, thereby increasing the sand content. Furthermore, when laboratory stirring was conducted to promote this process, irrigation with UFB decreased the sand content and increased the clay content. UFB irrigation softened the soil, and increased the thickness of the surface colloidal layer at the soil surface, causing soil swelling. These results suggest that irrigation with UFB promotes soil fragmentation and swelling, potentially improving soil structure.

Compliance with international, national, and/or institutional guidelines

Experimental studies were carried out in accordance with relevant institutional, national, or international guidelines or regulations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Miyamoto, S. et al. Physical properties of ultrafine bubbles generated using a generator system. Vivo 37, 2555–2563 (2023).

Ma, F., Zhang, P. & Tao, D. Surface nanobubble characterization and its enhancement mechanisms for fine-particle flotation: A review. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mater. 29, 727–738 (2022).

Zhu, T., Zhou, L., Wang, W., Zong, Y. & Zhang, L. Cleaning with bulk nanobubbles. Langmuir 32, 11203–11211 (2016).

Sueishi, N. et al. Plaque-removal effect of ultrafine bubble water: oral application in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Dent. Mater. J. 40, 272–278 (2021).

Taguchi, N., Onishi, I., Iyori, K. & Hsiao, Y. H. Preliminary evaluation of a commercial shampoo and fine bubble bathing in the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: A single-blinded, randomized, controlled study. Vet. Dermatol. 35, 400–407 (2024).

Yamada, H., Konishi, K., Shimada, K., Mizutani, M. & Kuriyagawa, T. Effect of ultrafine bubbles on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus during sterilization of machining fluid. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 15, 99–108 (2021).

Ebina, K. et al. Oxygen and air nanobubble water solution promote the growth of plants, fishes, and mice. PLoS One. 8, e65339. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065339 (2013).

Iijima, M. et al. Ultrafine bubbles effectively enhance soybean seedling growth under nutrient deficit stress. Plant. Prod. Sci. 23, 366–373 (2020).

Iijima, M. et al. Promotive or suppressive effects of ultrafine bubbles on crop growth depended on bubble concentration and crop species. Plant. Prod. Sci. 25, 78–83 (2022b).

Iijima, M. et al. Ultrafine bubbles alleviated osmotic stress in soybean seedlings. Plant. Prod. Sci. 25, 218–223 (2022a).

Minamikawa, K., Takahashi, M., Makino, T., Tago, K. & Hayatsu, M. Irrigation with oxygen-nanobubble water can reduce methane emission and arsenic dissolution in a flooded rice paddy. Environ. Res. Lett. 10. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/8/084012 (2015).

Ahmed, A. K. A. et al. Influences of air, oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide nanobubbles on seed germination and plant growth. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 5117–5124 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Nanobubbles promote nutrient utilization and plant growth in rice by upregulating nutrient uptake genes and stimulating growth hormone production. Sci. Total Environ. 800, 149627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149627 (2021).

Ueda, Y., Izumi, Y., Hirooka, Y., Watanabe, Y. & Iijima, M. Fine soil particle aggregation in ultra-fine bubble irrigated paddy fields. Water Supply. 22, 7972–7981 (2022).

Minamikawa, K. & Makino, T. Oxidation of flooded paddy soil through irrigation with water containing bulk oxygen nanobubbles. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 136323 (2020).

Wang, A. et al. Effect of bubble surface loading on bubble rise velocity. Miner. Eng. 174, 107252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2021.107252 (2021).

Shangguan, W., Dai, Y., Liu, B., Ye, A. & Yuan, H. A soil particle-size distribution dataset for regional land and climate modelling in China. Geoderma 171, 85–91 (2012).

Angers, D. A. & Caron, J. Plant-induced changes in soil structure: processes and feedbacks. Biogeochemistry 42, 55–72 (1998).

Iijima, M. et al. Erosion control on a steep sloped coffee field in Indonesia with alley cropping, intercropped vegetables, and no-tillage. Plant. Prod. Sci. 6, 224–229 (2003).

Qi, F. et al. Soil particle size distribution characteristics of different land-use types in the Funiu mountainous region. Soil. Till Res. 184, 45–51 (2018).

Willgoose, G. & Soils Physical weathering and soil particle fragmentation. In Principles Soilscape Landscape Evolution, 96–118 (Cambridge University Press,2018).

Munkholm, L. J., Schjønning, P., Debosz, K., Jensen, H. E. & Christensen, B. T. Aggregate strength and mechanical behaviour of a sandy loam soil under long-term fertilization treatments. Europ J. Soil. Sci. 53, 129–137 (2002).

Su, Y. Z., Yang, R., Liu, W. J. & Wang, X. F. Evolution of soil structure and fertility after conversion of native sandy desert soil to irrigated cropland in arid region, China. Soil. Sci. 175, 246–254 (2010).

Kumari, N. & Mohan, C. Basics of clay minerals and their characteristic properties. In Clay and Clay Minerals (ed. InNascimento, G. M. D.) 24 (IntechOpen, 2021). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.97672.

Weil, R. R. & Brady, N. C. Pearson,. Fundamentals of layer silicate cray structure. In The nature and properties of soils, 350–352 (2017).

Susanto, H., Herodian, S., Purwanto, Y. A. & Sugiarto, A. T. Potential utilization of ultrafine bubbles (UFB) technology in the cleaning process as a solution to replace the use of detergents and environmentally friendly: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1386, 012005. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1386/1/012005 (2024).

IUSS Working Group WRB. Glayic properties. In World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps. 4th edition, 75–76 (International Union of Soil Sciences, 2022).

Gee, G. W. & Bauder, J. W. Particle-size analysis. In Method of soil analysis, Part 1 Physical and Mineralogical Methods (ed. Klute, A.) 383–411 (Soil Science Society of America, 1986).

Murano, H., Takata, Y. & Isoi, T. Origin of the soil texture classification system used in Japan. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 61, 688–697 (2014).

Yoshida, O., Yoshida, K., Nakatani, N. & Ushiyama, K. Greenhouse gases from early flooded and organic paddy rice field around the lake Miyajimanuma. Wetland Res. 5, 25–33 (2014). In Japanese.

Iijima, M., Tatsumi, J. & Kono, Y. Development of a device for estimatingpenetration resistance of the soil in the root box. Environ. Control Biol. 28, 41–51 (1991).

Rezaei, M., Tab atabaekoloor, R. & Seyedi, M. Aghili Nategh, N. Effects of puddling intensity on the in-situ engineering properties of paddy field soil. Australian J. Agric. Engin. 3, 22–26 (2012).

Iijima, M., Griffiths, B. & Bengough, A. G. Sloughing of cap cells and carbon exudation from maize seedling roots in compacted sand. New. Phytol. 145, 477–482 (2000).

Iijima, M., Kono, Y., Yamauchi, A. & Pardales, J. R. Jr Effects of soil compaction on the development of rice and maize root systems. Environ. Exp. Bot. 31, 333–342 (1991).

Sugimoto, K. Studies on transpiration and water requirement of indica and Japonica rice plants. I. Relationship of transpiration to leaf area and to meteorological factors. J. Trop. Agric. 16, 260–264 (1972).

Kawata, S. I., Soejima, M. & Yamazaki, K. The superficial root formation and yield of hulled rice. Japanese J. Crop Sci. 47, 617–628 (1978). In Japanese.

Matsushima, S. & Wada, G. Analysis of developmental factors determining yield and its application to yield prediction and culture improvement of low land rice. XLVIII. Studies on the mechanism of ripening (9). Relation of the percentage of ripened grains and the yield of grains to the amount of carbohydrates stored by the time of heading, and that of carbohydrates accumulated after heading and the nitrogen content at heading time. Japanese J. Crop Sci. 27, 201–203 (1959). In Japanese with English summary.

Li, Y. et al. Determining the influencing factors of Preferential flow in ground fissures for coal mine dump eco-engineering. PeerJ 9, e10547. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10547 (2021).

Hirooka, Y., Motomura, M. & Iijima, M. Ultra-fine bubble irrigation promotes coffee (Coffea arabica) seedling growth under repeated drought stresses. Plant. Prod. Sci. 27, 47–55 (2024).

Hiyama, T. et al. Evaluation of surface water dynamics for water-food security in seasonal wetlands, north-central Namibia. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 364, 380–385 (2014).

Kotani, A. et al. Impact of rice cultivation on evapotranspiration in small seasonal wetlands of north-central Namibia. Hydrol. Res. Let. 12, 134–140 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Yoshikatsu Ueda (Kyoto University), Mr. Kadono Hisaaki, Mr. Hoshino Ikuo, Mr. Hattori Masataka, Ms. Sano Ayaka, Mr. Kasai Takazumi, Mr. Ryugo Tsuda (the University of Shiga Prefecture), and the members of the crop science laboratory, Faculty of Agriculture, Kindai University for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [23K26891].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. I.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Y. H.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Y. I.: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. K. S.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Y. T.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing Y.W.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. M. I.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwama, K., Hirooka, Y., Izumi, Y. et al. Ultrafine bubble water irrigation promotes soil particle fragmentation and reduces soil hardness in paddy fields. Sci Rep 15, 39626 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23375-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23375-3