Abstract

Automatic and reliable urine sediment analysis is essential for timely diagnosis and management of renal and urinary disorders. However, manual methods are time-consuming, subjective, and limited by operator abilities. In this study, we propose a novel deep learning method based on a multi-head YOLOv12 architecture combined with self-supervised pretraining and advanced inference through Slicing Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI) to effectively address these challenges. Unlike prior methods that employed a single detection head, our architecture features six specialized and independent detection heads: Cells, Casts, Crystals, Microorganisms/Yeast, Artifact, and Others, enabling simultaneous and fine-grained classification of the full spectrum of urine sediment particles, including all relevant subclasses. To facilitate robust training, we created a large-scale dataset (OpenUrine) encompassing 790 labeled images with over 31,285 bounding boxes across 39 categories, and 5640 unlabeled images for self-supervised learning. Evaluated on this complex 39-class dataset, our model achieved a precision of 76.59% and a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 64.15%, demonstrating competitive performance in detection accuracy, especially of small and low-contrast objects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urine sediment analysis is a cornerstone of clinical diagnostics, essential for the assessment and management of kidney diseases, urinary tract infections, and various systemic disorders1,2. In clinical practice, examining the microscopic components of urine, such as cells, casts, and crystals, provides vital clues about renal function and the presence of pathological abnormalities1. However, despite its clinical significance, manual urine sediment analysis remains a labor-intensive, subjective, and operator-dependent procedure, which leads to variability in results between professionals and laboratories3,4,5. With the rising volume of laboratory requests and limited availability of skilled personnel, there is a pressing need for accurate and efficient automated methods that deliver reliable and standardized results4.

The main problem addressed in our study is the challenge of automating urine sediment analysis using artificial intelligence (AI), especially for detecting and classifying the full spectrum of urinary particles. Many of these particles have highly diverse morphologies, small sizes, and are frequently underrepresented in datasets6,7. Although state-of-the-art AI methods are promising, they often depend on large, labeled datasets and tend to struggle with real-world image diversity and rare category detection5,6,8. This situation highlights the need for novel solutions that can leverage both labeled and unlabeled data within robust architectures.

Deep learning, especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has revolutionized medical image analysis in recent years. It offers automated feature extraction and remarkable performance in tasks such as disease detection, localization, and segmentation across multiple imaging modalities9,10,11,12. However, applying deep learning to urine sediment images presents unique challenges, including the lack of large annotated datasets, high-resolution imaging requirements, and wide variation in image quality. Recent advances demonstrate the value of self-supervised learning13,14, where unlabeled data is used to pretrain models via methods such as image reconstruction. This method can help to overcome data scarcity and improve model generalizability15. In this context, we introduce a large and diverse dataset, OpenUrine, which contains 790 labeled images (with over 31,285 expert-annotated bounding boxes across 39 categories) and an additional 5,640 unlabeled images for self-supervised learning.

A key innovation in our study is the design of a multi-head YOLOv12 architecture. Six parallel detection heads are specifically dedicated to Cells, Casts, Crystals, Microorganisms/Yeast, Artifacts, and Others. These heads operate simultaneously to enable comprehensive and precise detection of all relevant urinary sediment particles and their respective subclasses. Unlike previous single-head models, this architecture allows the model to independently capture the distinct morphological and visual characteristics of diverse particle types. Such a multi-head mechanism is essential for robust identification and discrimination among particle classes that differ widely in size, shape, and appearance, ensuring that both common and rare elements are detected with high accuracy.

The primary goal of this research is to develop and validate an effective and scalable deep learning method based on the multi-head YOLOv12, complemented by self-supervised pretraining and Slicing Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI)-based inference, for comprehensive and automated detection and classification of urinary sediment particles in microscopy images.

Related works

The potential of deep learning to overcome the limitations of traditional urine sediment analysis has spurred significant research efforts in developing deep learning-based AI models for automated analysis6. These models are designed to automatically identify and classify the various microscopic particles found in urine sediment, including red blood cells, white blood cells, epithelial cells, casts, crystals, bacteria, and yeast. Researchers have explored a wide range of deep learning architectures for this purpose, with CNNs being particularly prominent. Models such as AlexNet16, ResNet17, GoogleNet18, DenseNet19, MobileNet20, and YOLO have been adapted and applied to the task of urine particle classification and detection.

Some studies have focused on specific clinical applications of these AI models. For instance, research has explored the use of deep learning to detect bacteria in urine samples directly from microscopic images, eliminating the need for traditional, time-consuming urine culture methods21. Another study has investigated the potential of AI to screen for rare diseases, such as Fabry disease, by identifying unique cellular morphologies in urine sediment images22. To enhance the performance of these models, researchers are continuously exploring various techniques, including novel image amplification methods to augment training datasets, the incorporation of attention mechanisms to focus on relevant image features, and the development of hybrid methods that combine the strengths of CNNs with traditional feature extraction techniques like Local Binary Patterns (LBP)5,6,23,24. The use of pre-trained models and transfer learning is also a common strategy, allowing researchers to leverage knowledge gained from training on large general image datasets to improve the performance of models on the often-smaller urine sediment image datasets8 Furthermore, object detection methods like Faster R-CNN25, SSD26, and YOLO are being applied to simultaneously locate and classify urine particles within microscopic images, providing a more comprehensive analysis than simple image-level classification6.

The application of deep learning to urine sediment analysis encompasses various methodes tailored to specific analytical needs. Many studies focus on classification tasks, where the goal is to categorize individual urine sediment particles into predefined classes, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, and different types of crystals5,12. These models learn to recognize the distinct visual features of each particle type to perform accurate classification. Another significant method involves object detection tasks, where the AI model aims to not only classify but also to precisely locate multiple urine particles within a single microscopic image7,12. This is particularly valuable in clinical settings as it allows for the quantification of different particle types and the analysis of their spatial relationships within the urine sediment.

Liang et al.27 in their study used a dataset containing 10,752 images with seven classes consisting of urinary particles (erythrocytes, leukocytes, epithelial, low-transitional epithelium, casts, crystal, and squamous epithelial cells). It was stated that after balancing the image categories, the data was used to train a RetinaNet model28. It was stated that an 88.65% accuracy value was obtained with this developed method on a test set, with a processing time of 0.2 s per image. Yildirim et al.5 in their study used a data set containing 8,509 particle images with eight classes obtained from urine sediment. They developed a hybrid model based on textural (LBP) and ResNet50. It was stated that after optimizing and combining features, a high accuracy value of 96.0% was obtained with the proposed model. Liang et al.23 conducted a series of studies aimed at improving urinary sediment analysis through deep learning-based object detection models. In one study, they proposed the Dense Feature Pyramid Network (DPFN) architecture, integrating DenseNet into the standard FPN model and incorporating attention mechanisms into the network head. This method significantly mitigated class confusion in urine sediment images, particularly improving erythrocyte detection accuracy from 65.4% to 93.8%, and achieving a mean average precision (mAP) of 86.9% on the test set. In a complementary study29, they framed urinary particle recognition as an object detection task using CNN-based models such as Faster R-CNN and SSD. Evaluated on a dataset of 5,376 labeled images across seven urinary particle categories, their best-performing model achieved an mAP of 84.1%.

Ji et al.15 proposed a semi-supervised network model (US-RepNet) to classify urine sediment images. They used a data set containing 429,605 urine sediment images with 16 classes. They stated that they obtained a 94% accuracy value with their suggested model. Li et al.30 in their study used a data set containing 2551 urine sediment images with four classes (red blood cells, white blood cells, epithelial cells, and crystals). They developed a modified LeNet-531. They stated that they performed classification with 92% accuracy. Khalid et al.24 compiled a dataset of 820 annotated urine sediment images. This dataset was used to train and evaluate five convolutional neural network models - MobileNet, VGG1632, DenseNet, ResNet50, and InceptionV333 - along with a proposed CNN architecture. MobileNet achieved the highest true positive recall, followed closely by the proposed model. Both models reached a top accuracy of 98.3%, while InceptionV3 and DenseNet demonstrated slightly lower but still comparable accuracy of 96.5

Avci et al.34 developed a model for urinary particle recognition that enhances the resolution of microscopic images using a super-resolution Faster R-CNN method. They utilized pre-trained architectures including AlexNet, VGG16, and VGG19. Among these, the AlexNet-based model delivered the best performance, achieving a recognition accuracy of 98.6%. In another study35, they introduced a combination of Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) and a neural network-based system, the ADWEENN algorithm, for recognizing 10 different categories of urine sediment particles, achieving an accuracy of 97.58%.

In another study, Erten et al. introduced Swin-LBP, a handcrafted feature engineering model for urine sediment classification that combines the Swin transformer architecture with local binary pattern (LBP) techniques. Their six-phase approach—including LBP-based feature extraction, neighborhood component analysis (NCA) for feature selection, and support vector machine (SVM)36 classification achieved an accuracy of 92.60% across 7 classes of urinary sediment elements, outperforming conventional deep learning methods applied on the same dataset37. In a subsequent study, the same group proposed another model integrating cryptographic-inspired image preprocessing techniques, notably the Arnold Cat Map (ACM), with patch-based mixing and transfer learning. Leveraging DenseNet201 for deep feature extraction and NCA for feature selection, this model reached an even higher classification accuracy of 98.52% for seven types of urinary particles8.

A recent study proposed a combined CNN model integrated with an Area Feature Algorithm (AFA), enabling improved recognition of 10 urine sediment categories from a large dataset of 300,000 images, achieving a test accuracy of 97% and significantly enhancing the recognition of visually similar particles such as RBCs and WBCs38. A deep learning model based on VGG-16 was developed to classify 15 types of urinary sediment crystals using 441 images, which were augmented to 60,000 images through targeted data augmentation. Removing the random cropping step in data augmentation significantly improved accuracy, and the model achieved a performance of 91.8%39.

Lyu et al.7 developed an advanced deep learning model, YUS-Net, based on an improved YOLOX40 architecture for multi-class detection of urinary sediment particles. The model integrates domain-specific data augmentation, attention mechanisms, and Varifocal loss to enhance the detection of challenging particle types, particularly small and densely distributed objects. Evaluated on the USE dataset, YUS-Net achieved impressive performance, with a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 96.07%, 99.35% average precision, and 96.77% average recall, demonstrating its potential for efficient and accurate end-to-end urine sediment analysis.

A critical limitation of existing research is the narrow scope of detection. The vast majority of published object detection studies focus on a small number of classes. For example, the influential work by Liang et al.29 used a dataset of 5,376 labeled images across seven urinary particle categories. The dataset used by Li et al.27 also contained seven classes. The hybrid classification model by Yildirim et al.5 was trained on eight particle types. Even more ambitious studies, such as that by Ji et al.15, which used a large dataset, topped out at 16 categories.

Beyond prior urine microscopy studies, several recent deep learning frameworks across other domains further highlight the rapid evolution of hybrid architectures. In biomedical imaging, models such as DCSSGA-UNet41 and EFFResNet-ViT42 adopt dense connectivity, semantic attention, and CNN–Transformer fusion to enhance segmentation and classification precision. Similarly, deep hybrid and self-supervised architectures from cyber-physical security research43,44,45 demonstrate parallel methodological advances in representation learning and encoder–decoder design. Comparable trends have also appeared in unrelated areas such as sports performance analytics and wearable sensor forecasting46,47, reflecting the general shift toward multi-branch and attention-driven deep models across domains.

This “granularity gap” between existing research and the diverse reality of clinical samples is a major barrier to practical deployment. Our work directly confronts this gap by introducing a model and a public dataset, OpenUrine, designed for the comprehensive detection of 39 distinct categories, representing a significant leap in complexity and clinical relevance.

Dataset

The dataset utilized in this study, named OpenUrine, comprises 6430 images of the urinary sediment. OpenUrine consists of a total of 790 anonymized, expert-labeled microscopic images of urinary sediment, in addition to 5,640 unlabeled images used for self-supervised learning. This is the first publicly available dataset dedicated to urinary particle detection. No patient metadata was collected at any stage; all samples were fully anonymized and are referenced only by randomly assigned identification codes. None of the images carry patient-specific information, ensuring complete privacy and compliance with ethical data standards. Images were collected from multiple laboratories using different microscope models and various smartphone cameras to ensure a broad range of imaging conditions reflective of real-world clinical variability.

An overview of the dataset, including the number of labeled and unlabeled images as well as the total number of bounding box annotations, is presented in Table 1. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of all 39 categories, reporting the number of annotated objects, number of images containing each label, and a brief scientific description for each particle type, facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the dataset’s diversity and clinical relevance.

Data labeling

Each image was assigned a unique identification code upon acquisition. Two experienced clinical biochemistry experts conducted the labeling process independently, ensuring high reliability and consensus in recognizing and delineating all urinary sediment structures present. All detectable objects were marked with bounding boxes and assigned one of the 39 class labels. Figure 1 presents sample annotated microscopic fields from the OpenUrine dataset. Each sub-image shows a real clinical sample with expert-verified bounding box annotations identifying and localizing multiple urinary particles across diverse imaging conditions. Figure 2 displays representative examples of all 39 particle categories present in the dataset. Each image illustrates the unique morphology and appearance of a specific urinary sediment particle, such as various cell types, casts, crystals, microorganisms, and artifacts.

Unlabeled images for self-supervised learning

Beyond the labeled portion, the OpenUrine dataset also includes 5,640 unlabeled images. These images, which share the same acquisition characteristics as the labeled set, were used in the self-supervised stage of the proposed method to further boost model performance and robustness.

Data partitioning

The labeled dataset was divided into training and testing sets in an 80:20 ratio at the patient level, ensuring that all images from a single patient are assigned to either the training or testing set, but not both. This patient-level split prevents data leakage and ensures realistic evaluation of the model’s generalization capability to new patients.

The labeled dataset was divided using 5-fold cross-validation. Each fold was trained independently, and the reported results represent the mean±std (%) across the five folds. This partitioning and validation process ensures fair and objective model assessment.

Method

This section outlines the methodology for fully automated detection and categorization of urinary sediment particles in high-resolution microscopy, leveraging a custom multi-head YOLOv12 architecture designed specifically for the OpenUrine dataset.

Architecture overview

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the proposed method is a multi-head object detection based on YOLOv1248,49, adapted and optimized for challenging urinary sediment images (average size \(1800 \times 1800\) px). A key innovation is the separation of the detection module into six distinct semantic heads, each corresponding to a clinically relevant super-category of urinary sediment objects. This structure enhances discrimination and robustness, particularly for rare or visually subtle subclasses. To further address the challenges of detecting small, densely packed structures in large fields, Slicing Aided Hyper-Inference (SAHI)50 is tightly integrated into the inference pipeline.

Overview of the proposed two-stage deep learning method. (A) The encoder–decoder network is pretrained via self-supervised reconstruction on unlabeled urine sediment images to learn rich feature representations. (B) The pretrained encoder (backbone) is fine-tuned for object detection using six parallel heads, enabling precise multi-class identification of urinary particles.

Backbone network

Each input image X is processed by a YOLO backbone, which extracts multiscale, high-level feature maps:

These feature maps provide rich spatial and morphological representations crucial for accurate detection across a wide range of object scales.

Multi-head detection module

The detection module utilizes six parallel output heads, each specializing in one clinically important super-category of urinary sediment particles: Cells, Casts, Crystals, Microorganisms/Yeast, Artifact, and Others. This categorization directly follows established clinical taxonomy and precisely matches the semantic groupings defined in Table 2. Each head is responsible for detecting all subcategories corresponding to its group.

For each group i, the shared feature map F is passed to the corresponding detection head:

where \(Y_i\) encodes the bounding boxes, objectness scores, and class probabilities for all subclasses assigned to that head.

Loss function

In our architecture, the detection loss follows the YOLOv12 formulation48, but is applied independently to each of the six output heads. This design allows every head, specialized for its own clinical super-category, to optimize its parameters without interference from unrelated particle types, while still contributing to the overall network performance.

The total loss is the weighted sum of the head-specific losses, as shown in Equation 1.

where \(\lambda _i\) controls the relative weight of head i based on its clinical importance and representation in the dataset. The values are tuned as shown in Table 3.

Each head-specific loss \(L_i\) is defined in Eq. 2.

where \(\textrm{gain}_{\textrm{box}}\), \(\textrm{gain}_{\textrm{cls}}\), and \(\textrm{gain}_{\textrm{obj}}\) correspond to box loss gain, classification loss gain, and objectness scaling hyperparameters defined in Table 3.

Bounding box regression in YOLOv12 combines IoU-based loss51 with the Distribution Focal Loss (DFL)52 to enhance localization precision. The bounding box regression loss for head i is expressed in Eq. (3).

Here, \(L_{\textrm{CIoU}}\) accounts for overlap, center distance, and aspect ratio, while \(L_{\textrm{DFL}}\) refines predicted box coordinates at sub-pixel resolution. The complete IoU loss term is defined in Eq. (4).

where \(\rho\) is the center-point distance, c is the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing box, and v is the aspect ratio term with balance factor \(\alpha\). The distribution focal loss is expressed in Eq. (5).

where \(p_j\) is the predicted probability for the discretized bin of a coordinate value and \(q_j\) is the corresponding soft target.

Objectness loss53 measures how well the model distinguishes objects from background. The objectness loss for head i is formulated in Eq. (6).

where \(o_j\) is the predicted objectness score for anchor j, and \(o_j^{GT}\in \{0,1\}\).

Classification loss53 ensures correct subclass identification within each head. The classification loss for head i is defined in Eq. (7).

where \(p_{j,k}\) is the predicted probability for subclass k in sample j, and \(C_i\) is the number of subclasses in head i.

Unlike a unified detector that learns all categories together, here each head focuses only on the visual patterns of its assigned group, using Eqs. 3 through 7 independently. This separation avoids competition between unrelated classes, reduces the impact of severe class imbalance, and allows adjusting \(\lambda _i\) in Eq. 1 to boost underrepresented yet clinically significant categories. As our ablation studies show, removing this head-level independence leads to the sharpest drop in mean Average Precision (mAP) and recall.

Training procedure

A two-stage training strategy, optimized to leverage both labeled and unlabeled data, is applied.

(1) Self-supervised pretraining: during the self-supervised pretraining stage, all 5640 unlabeled images were utilized in an image reconstruction autoencoder architecture (as illustrated in Fig. 3). The network follows an encoder-decoder structure: the encoder mirrors the YOLOv12 backbone to extract latent morphological representations, and the decoder reconstructs the input image using these features. The model was optimized with a combined L1 + SSIM reconstruction loss, enforcing both pixel-level accuracy and structural consistency between input and reconstructed outputs. This pretext task effectively encourages the backbone to capture intrinsic microscopic texture and morphology priors even without labels. The pretrained encoder weights were subsequently transferred to initialize the YOLOv12 backbone during the supervised fine-tuning stage.

(2) Supervised fine-tuning: the backbone’s pretrained weights initialize the detection model, which is then fine-tuned using the 790 image-level-labeled samples and bounding box annotations. Each particle is routed to its corresponding semantic head, and the total loss is jointly optimized. Diverse data augmentation (e.g., Mosaic, Sacle) and a SGD with Momentum are employed.

Inference with SAHI

For inference, we employed SAHI to enhance detection performance on high-resolution microscopic images. SAHI systematically divides each input image into overlapping tiles of 640\(\times\)640 pixels with an overlap ratio of 0.25 (25%) in both horizontal and vertical directions. This slicing strategy enables the model to process smaller image regions with higher effective resolution, significantly improving detection sensitivity for small and densely packed urinary particles that might be missed in full-resolution inference.

Each slice is independently processed by our proposed method, generating separate predictions for particles within that region. The tiled outputs are subsequently merged through non-maximum suppression (NMS) to eliminate duplicate detections and produce consolidated, non-redundant bounding boxes.

Results

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed object detection method, we conducted a series of experiments on the OpenUrine dataset. These experiments were specifically designed to demonstrate the superiority of our method compared to prior object detection methods under identical conditions.

Performance evaluation metrics

Model performance was assessed using several established object detection metrics. Precision quantifies the proportion of correctly identified positive detections among all predicted positives, as defined in Eq. (8):

where \(TP\) and \(FP\) denote the numbers of true positive and false positive predictions, respectively. Recall measures the proportion of actual positives that are correctly detected by the model, as shown in Eq. (9):

where \(FN\) is the number of false negatives. The overall detection capability is further summarized by the mean Average Precision (mAP), which is the unweighted mean of the Average Precision (AP) across all object classes, as presented in Eq. (10):

where \(N\) is the total number of classes under consideration. Additionally, the evaluation follows the COCO protocol54 by reporting mAP@50-95, which represents the mean AP computed over multiple intersection-over-union (IoU) thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 (in increments of 0.05), thereby providing a stricter and more comprehensive measure of detection performance.

Implementation details

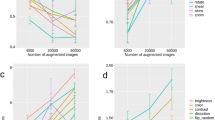

A comprehensive hyperparameter optimization protocol was carried out as part of our experimental design (see Fig. 4). For this purpose, we performed 300 independent training runs, each for 100 epochs, gradually searching the space of learning rate, momentum, weight decay, and various augmentation factors as listed in Table 3. Each configuration was evaluated on the validation split after every epoch, allowing us to systematically identify optimal values. All experiments, including baseline comparisons, were performed on the OpenUrine dataset for scientific consistency.

The scatter plots in Fig. 4 visualize the relationship between key hyperparameters and resulting detection metrics (such as mAP, mAP@50-95, Precision, and Recall); final selected values are denoted by a cross marker.

For the final training of our best-performing model, we utilized the optimal parameters over 300 epochs with a batch size of 16 and an input image size of \(960 \times 960\) pixels, ensuring maximal capacity to learn robust object representations.

Comparative evaluation

Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of automated urine sediment analysis models is crucial for establishing their accuracy, robustness, and clinical viability. In this section, we present a comprehensive comparative analysis of our proposed method,and state-of-the-art methods, followed by investigations into how input image size and particle class influence model performance. The reliability and interpretability of the deep network are further validated through visual explanation techniques such as Grad-CAM.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

Table 4 provides a comprehensive comparison between our method, ans state-of-the-art methods. Our proposed method achieves the highest performance on all core metrics (precision, recall, mAP\(_{50}\), mAP\(_{50-95}\)), outperforming both the latest YOLO models and prior state-of-the-art methods. While absolute values such as 76.59% precision may appear modest compared to simpler tasks, it is important to note that the OpenUrine dataset includes 39 diverse classes, making it a far more complex challenge than datasets used in previous studies. The ablation results reveal that both the multi-head detection strategy and self-supervised pretraining contribute substantially to the observed gains. In particular, removing the multi-head scheme leads to the largest drop in precision, recall, and mean average precision, highlighting the value of specialized detection branches for different particle types. Our method, even without some of these advanced modules, remains competitive with or superior to prior works. YOLO-based baselines and state-of-the art methods, while strong, are outperformed by our method, especially on the challenging OpenUrine dataset. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our architectural innovations for improving the automated analysis of urine sediment images.

Impact of input size

As shown in Table 6, an input resolution of \(960\times 960\) pixels yielded the highest overall mAP while maintaining stable convergence and feasible GPU memory usage (24 GB). Hence, this resolution was adopted for all subsequent experiments. The model achieves optimal results at \(960 \times 960\) pixels, outperforming both smaller and even larger input sizes on almost all metrics. While a further increase to \(1280 \times 1280\) yields competitive results, there is no consistent improvement and some metrics are slightly reduced, likely due to increased computational noise, overfitting, or diminished returns with upscaling. Notably, reducing the input size below 960 sharply degrades performance, especially for mAP50 and recall. This is particularly important because many urinary particles (such as bacteria and crystals) are small and easily lost at lower resolutions. At the lowest tested sizes (80 and 40 pixels), model recall especially collapses, confirming that sufficient image resolution is critical for the reliable detection of fine and small-scale particles. These findings underscore the need to optimize input size for automatic urine sediment analysis, balancing computational efficiency with the necessity to preserve particle detail.

Impact of heads

The influence of each detection head was evaluated through a head-wise ablation test, as summarized in Table 5. When any single head was removed, its corresponding samples were not excluded from training; instead, all annotations were reassigned to the Others head to preserve the dataset composition and training balance. The results show that disabling any individual head consistently reduced detection accuracy, indicating that each contributes unique and complementary information. The most pronounced performance drop occurred when the Microorganisms head was removed, reflecting their critical role in discriminating morphologically complex or clinically significant particle groups.

Class-wise analysis

The results in Table 7 demonstrate that our method substantially improves detection accuracy across most urinary sediment particle classes compared to previous baselines. The model achieves high precision and recall on classes with distinctive morphological features, such as Calcium Oxalate, Bilirubin, and Calcium Carbonate, showing the benefit of leveraging their unique visual patterns. However, certain classes remain challenging: for example, Bacteria achieve high precision but low recall, likely due to their small size and tendency to be overlooked in crowded backgrounds. Morphologically similar cells, notably RBC and WBC, are sometimes confused due to their overlapping appearance, limiting further accuracy improvements in these categories. Additionally, rare or subtle classes such as Fat Droplets and Renal Epithelial Cells still suffer from lower detection rates.

Typical failure cases include missed detections in densely clustered regions, merged bounding boxes where adjacent particles overlap, and occasional confusion between morphologically similar RBC and WBC, especially when illumination or focus artifacts blur their boundaries. Quantitative analysis indicates that approximately 38% of the undetected WBC instances were misclassified as RBC, while 43% of the missed RBC instances were incorrectly detected as WBC. This bidirectional confusion highlights their strong morphological resemblance under bright-field microscopy. In crowded microscopic fields, small Bacteria are sometimes undetected or merged with noise, while low-contrast Renal Epithelial Cells may be mistaken for background structures. These qualitative observations (illustrated in Fig.5) reveal the key limitations of the current model and inform future improvements such as boundary-aware loss design and targeted synthetic data augmentation for rare or visually ambiguous categories.

Overall, while our model demonstrates meaningful advances in most categories, the reliable detection of small, ambiguous, or visually similar particles remains a significant challenge for automated urine sediment analysis.

Grad-CAM visualization of model attention across representative classes. Top row: detection and attention patterns for Amorphous particles, showing that the model accurately localizes dense crystalline regions and focuses its activations (red/yellow) on texture-rich clusters relevant to this class. Bottom row: predictions for Epithelial Cells where the model highlights cell nuclei and boundary contours while de-emphasizing background noise and staining artifacts. In each pair, the left image displays predicted bounding boxes and class labels, while the right image presents the corresponding Grad-CAM heatmap. Warmer colors (red/yellow) indicate regions contributing most to the network’s decision, confirming that it primarily attends to morphologically informative structures such as epithelial cells and amorphous deposits rather than irrelevant background patterns.

Clinical validation

Urine microscopy results from 84 patients, previously analyzed and verified by experienced laboratory technologists, were employed for clinical validation of the proposed model. For each sample, three to five representative microscopic fields were processed by the model, and the predictions were averaged at the patient level before comparison with the laboratory-reported results. The predicted outputs were mapped to the standard five-level microscopic quantitation scale (none, rare, few, moderate, many) used in routine clinical reporting. A prediction was considered correct when the model’s categorical output matched the laboratory category for the same urinary component.

All major urinary sediment components, including RBCs, WBCs, epithelial cells, calcium oxalate crystals, bacteria, and mucus, were evaluated accordingly. Table 8 presents the clinical accuracy of the proposed model relative to technologist reports. Discrepant samples were further reviewed by an independent clinical biochemist to confirm the final reference label.

Interpretability via visual explanation

In Fig. 5, a comparison is presented between the model’s bounding box predictions (left) and Grad-CAM visualizations (right) for selected test images. The detection results illustrate the network’s ability to localize and classify different urine sediment constituents, such as amorphous particles and epithelial cells. Notably, the Grad-CAM activation maps reveal that the highlighted regions (red areas) are primarily concentrated over clear and well-defined particles within the microscopic fields, confirming that the model bases its predictions on relevant visual cues rather than background artifacts. This qualitative interpretability analysis demonstrates the reliability and transparency of the network’s decision-making process in real-world clinical samples.

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced a novel deep learning method tailored for automated urine sediment analysis, integrating a multi-head YOLOv12 architecture, self-supervised pretraining, and SAHI-based inference. Our method effectively addresses critical challenges such as small-object detection, class imbalance, and data scarcity, leading to a competitive precision of 76.59% on a large, diverse dataset. The deployment of six specialized detection heads allows for detailed and simultaneous classification across all relevant urinary particles and artifacts, supporting detailed clinical interpretation. Furthermore, the establishment and public release of the OpenUrine dataset fill a crucial gap, providing a valuable resource for further research in this domain.

Future work will focus on refining the model’s performance, especially for rare or visually ambiguous particle types, by exploring adaptive focal loss weighting, targeted synthetic data augmentation, and self-supervised consistency regularization to mitigate class imbalance. We also intend to integrate physical and chemical urinalysis test data to further enhance diagnostic precision and generalizability.

Data availability

The OpenUrine dataset is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Interested researchers are invited to submit an application through the designated request form available at www.github.com/alikarimi120/OpenUrine. It should be noted that this dataset is provided solely for academic and non-commercial research purposes. Prior to access, requestors are required to agree to the terms and conditions specified in the request form, ensuring the data will be used in accordance with ethical standards and regulations.

Code availability

Sample codes, experiments results, and models are hosted on the following GitHub repository: www.github.com/alikarimi120/OpenUrine.

References

Simerville, J. A., Maxted, W. C. & Pahira, J. J. Urinalysis: A comprehensive review. Am. Fam. Phys. 71, 1153–1162 (2005).

Cavanaugh, C. & Perazella, M. A. Urine sediment examination in the diagnosis and management of kidney disease: Core curriculum 2019. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 73, 258–272 (2019).

Kouri, T. et al. European urinalysis guidelines. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 60, 1–96 (2000).

Winkel, P., Statland, B. & Joergensen, K. Urine microscopy, an iii-defined method, examined by a multifactorial technique. Clin. Chem. 20, 436–439 (1974).

Yildirim, M., Bingol, H., Cengil, E., Aslan, S. & Baykara, M. Automatic classification of particles in the urine sediment test with the developed artificial intelligence-based hybrid model. Diagnostics 13, 1299 (2023).

Xu, X.-T., Zhang, J., Chen, P., Wang, B. & Xia, Y. Urine sediment detection based on deep learning. In Intelligent Computing Theories and Application: 15th International Conference, ICIC 2019, Nanchang, China, August 3–6, 2019, Proceedings, Part I 15. 543–552 (Springer, 2019).

Lyu, H. et al. Automated detection of multi-class urinary sediment particles: An accurate deep learning approach. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 43, 672–683 (2023).

Erten, M. et al. Automated urine cell image classification model using chaotic mixer deep feature extraction. J. Digit. Imaging 36, 1675–1686 (2023).

Shen, D., Wu, G. & Suk, H.-I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 19, 221–248 (2017).

Li, M., Jiang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Zhu, H. Medical image analysis using deep learning algorithms. Front. Public Health 11, 1273253 (2023).

Ker, J., Wang, L., Rao, J. & Lim, T. Deep learning applications in medical image analysis. IEEE Access 6, 9375–9389 (2017).

Cai, L., Gao, J. & Zhao, D. A review of the application of deep learning in medical image classification and segmentation. Ann. Transl. Med. 8, 713 (2020).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International Conference on Machine Learning. 1597–1607 (PmLR, 2020).

Huang, S.-C. et al. Self-supervised learning for medical image classification: a systematic review and implementation guidelines. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 74 (2023).

Ji, Q., Jiang, Y., Wu, Z., Liu, Q. & Qu, L. An image recognition method for urine sediment based on semi-supervised learning. IRBM 44, 100739 (2023).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 25 (2012).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 770–778 (2016).

Szegedy, C. et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1–9 (2015).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4700–4708 (2017).

Howard, A. G. et al. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861 (2017).

Iriya, R. et al. Deep learning-based culture-free bacteria detection in urine using large-volume microscopy. Biosensors 14, 89 (2024).

Uryu, H. et al. Automated urinary sediment detection for Fabry disease using deep-learning algorithms. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 33, 100921 (2022).

Liang, Y., Tang, Z., Yan, M. & Liu, J. Object detection based on deep learning for urine sediment examination. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 38, 661–670 (2018).

Khalid, Z. M., Hawezi, R. S. & Amin, S. R. M. Urine sediment analysis by using convolution neural network. In 2022 8th International Engineering Conference on Sustainable Technology and Development (IEC). 173–178 (IEEE, 2022).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 580–587 (2014).

Liu, W. et al. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In European Conference on Computer Vision. 21–37 (Springer, 2016).

Li, Q. et al. Inspection of visible components in urine based on deep learning. Med. Phys. 47, 2937–2949 (2020).

Lin, T.-Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. 2980–2988 (2017).

Liang, Y., Kang, R., Lian, C. & Mao, Y. An end-to-end system for automatic urinary particle recognition with convolutional neural network. J. Med. Syst. 42, 1–14 (2018).

Li, T. et al. The image-based analysis and classification of urine sediments using a LENET-5 neural network. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imaging Vis. 8, 109–114 (2020).

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 86, 2278–2324 (2002).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2818–2826 (2016).

Avci, D. et al. A new super resolution faster r-cnn model based detection and classification of urine sediments. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 43, 58–68 (2023).

Avci, D., Leblebicioglu, M. K., Poyraz, M. & Dogantekin, E. A new method based on adaptive discrete wavelet entropy energy and neural network classifier (adweenn) for recognition of urine cells from microscopic images independent of rotation and scaling. J. Med. Syst. 38, 1–9 (2014).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Erten, M. et al. Swin-lbp: A competitive feature engineering model for urine sediment classification. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 21621–21632 (2023).

Ji, Q., Li, X., Qu, Z. & Dai, C. Research on urine sediment images recognition based on deep learning. IEEE Access 7, 166711–166720 (2019).

Nagai, T., Onodera, O. & Okuda, S. Deep learning classification of urinary sediment crystals with optimal parameter tuning. Sci. Rep. 12, 21178 (2022).

Ge, Z., Liu, S., Wang, F., Li, Z. & Sun, J. Yolox: Exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.08430 (2021).

Hussain, T., Shouno, H., Mohammed, M. A., Marhoon, H. A. & Alam, T. DCSSGA-UNET: Biomedical image segmentation with DenseNet channel spatial and semantic guidance attention. Knowl.-Based Syst. 314, 113233 (2025).

Hussain, T. et al. Effresnet-vit: A fusion-based convolutional and vision transformer model for explainable medical image classification. IEEE Access (2025).

Ali, Z. et al. Deep learning-driven cyber attack detection framework in dc shipboard microgrids system for enhancing maritime transportation security. In IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems (2025).

Ali, Z. et al. A novel hybrid signal processing based deep learning method for cyber-physical resilient harbor integrated shipboard microgrids. In IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications (2025).

Ali, Z. et al. A novel intelligent intrusion detection and prevention framework for shore-ship hybrid ac/dc microgrids under power quality disturbances. In 2025 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting (IAS). 1–7 (IEEE, 2025).

Franzò, M., Pica, A., Pascucci, S., Marinozzi, F. & Bini, F. Hybrid system mixed reality and marker-less motion tracking for sports rehabilitation of martial arts athletes. Appl. Sci. 13, 2587 (2023).

Ferraz, A., Duarte-Mendes, P., Sarmento, H., Valente-Dos-Santos, J. & Travassos, B. Tracking devices and physical performance analysis in team sports: a comprehensive framework for research—trends and future directions. Front. Sports Active Living 5, 1284086 (2023).

Tian, Y., Ye, Q. & Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12524 (2025).

Tian, Y., Ye, Q. & Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors (2025).

Akyon, F. C., Altinuc, S. O. & Temizel, A. Slicing aided hyper inference and fine-tuning for small object detection. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). 966–970. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIP46576.2022.9897990 (2022).

Zheng, Z. et al. Distance-IOU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 34, 12993–13000 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Generalized focal loss: Learning qualified and distributed bounding boxes for dense object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 21002–21012 (2020).

Bishop, C. M. & Nasrabadi, N. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Vol. 4 (Springer, 2006).

Lin, T.-Y. et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision. 740–755 (Springer, 2014).

Tan, M., Pang, R. & Le, Q. V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 10781–10790 (2020).

Li, Y., Mao, H., Girshick, R. & He, K. Exploring plain vision transformer backbones for object detection. In European Conference on Computer Vision. 280–296 (Springer, 2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 16965–16974 (2024).

Lv, W. et al. Rt-detrv2: Improved baseline with bag-of-freebies for real-time detection transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.17140 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Dp-yolo: Effective improvement based on yolo detector. Appl. Sci. 13, 11676 (2023).

Komori, T., Nishikawa, H., Taniguchi, I. & Onoye, T. Improvement of yolov7 with attention modules for urinary sediment particle detection. In 2023 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS). 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Suhail, K. & Brindha, D. Microscopic urinary particle detection by different yolov5 models with evolutionary genetic algorithm based hyperparameter optimization. Comput. Biol. Med. 169, 107895 (2024).

Naznine, M., Salam, A., Khan, M. M., Nobi, S. F. & Chowdhury, M. E. An ensemble deep learning approach for accurate urinary sediment detection using yolov9e and kd-yolox-vit. IEEE Access (2025).

Akhtar, S., Hanif, M., Saraoglu, H. M., Lal, S. & Arshad, M. W. Yolov11-samnet: A hybrid detection and segmentation framework for urine sediment analysis. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications. 241–251 (Springer, 2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of artificial intelligence-assisted tools, including ChatGPT (OpenAI) and Grammarly, for improving the clarity, grammar, and overall readability of the manuscript. The authors are solely responsible for the content and interpretation of the findings presented in this paper. A part of the article has been extracted from the thesis written by Mehdi Alizadeh in the School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (registration number: 43011137). The local Committee for Ethics approved the study (reference number: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1403.318).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. collected the data, contributed to unlabeled data annotation, and assisted in manuscript preparation. A.K. performed data preprocessing, wrote the manuscript, designed and conducted the experiments, and developed the proposed method. M.J.B. contributed to the implementation of the proposed method. A.M. and S.A supervised the project. M.S. revised the manuscript and supervised the project. M.A.A. verified the theoretical findings, revised the manuscript, and supervised the project. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

In accordance with ethical guidelines, this study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1403.318). Prior to participation, all individuals provided written informed consent. Additionally, explicit consent for the publication of any images included in this manuscript was obtained from each participant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alizadeh, M., Karimi, A., Barikbin, M.J. et al. A multi-head YOLOv12 with self-supervised pretraining for urinary sediment particle detection. Sci Rep 15, 41347 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25339-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25339-z