Abstract

Metabolic reprogramming plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM). This study aims to construct a prognostic model based on metabolic-related genes (MRGs) to forecast patient outcomes and their response to immunotherapy. 10 machine learning algorithms within a cross-validation framework were utilized to compute prognostic risk scores based on MRGs, dividing SKCM patients into high- and low-risk groups. Further exploration included immune-related scores, immune infiltration levels, and oncological phenotype between these groups. The expression levels of six essential MRGs were assessed, and the effect of GALNT2 on proliferation and migration in SKCM cell lines was confirmed. This study has developed a new MRGs prognostic risk model that effectively predicts the survival of melanoma patients. The low-risk group exhibits higher immune scores and immune cell infiltration, which are beneficial for immunotherapy. In contrast, the high-risk group is positively correlated with the malignant phenotype of tumors, with increased MRG expression promoting tumor development. The study also identified six key genes, among which both the silencing and overexpression of GALNT2 significantly affect the proliferation and migration of melanoma cells. This study highlights the significance of MRGs in predicting patient survival and immunotherapy outcomes, providing insights for potential future targeted therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), one of the deadliest forms of skin cancer, is classified among the most frequently occurring cancer types1. The incidence of melanoma has risen significantly over the past decades, especially in the Caucasian population2,3. In 2020, approximately 325,000 melanoma cases were reported worldwide4. Melanoma has multiple causatibe factors and results from the combination of genetic predisposition and environmental exposure5,6,7. Tsao et al.8 demonstrated that melanoma has a clear autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, and mutations in the CDKN2A and P16 genes are the most common genetic abnormalities. Volko et al.9 examined the hypothesis that exposure to environmental factors, including sunscreens, photosensitizing drugs, and exogenous hormones, may increase the risk of melanoma development. Multiple risk factors associated with SKCM, such as age, gender and skin type10, have been identified. However, these elements are not accurate predictors of the prognosis and survival in patients with SKCM. Therefore, identifying new biomarkers associated with prognosis is extremely important.

Specific metabolic environments are considered to be key factors that directly promote tumor growth11,12. Metabolic reprogramming is recognized as a crucial characteristic of cancer and a necessary step during tumorigenesis13,14,15. Heiden et al.16 described the changes in glucose metabolism in the tumor cells (the Warburg effect). Mutations in oncogenes induce metabolic reprogramming to varying degrees by activating the proliferation-related signaling pathways17. Jiang et al.18 observed that exposure to TGFβ1 alters fatty acid synthesis in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. This modification leads to enhanced oxidative phosphorylation, which in turn promotes ATP production and cell migration. In addition, abnormalities in this metabolic pattern may play a role in the tumor immune microenvironment (TME) and the infiltration of immune cells within the tumor19. Therefore, metabolic reprogramming is crucial in tumor development. However, the role of metabolic genes in cutaneous melanoma prognosis remains to be elucidated.

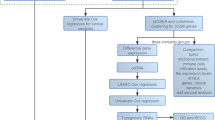

In this study, we aimed to reveal the potential roles of MRGs (Metabolic-Related Genes) in cutaneous melanoma progression and provide a basis for the development of novel therapeutic strategies. The expression pattern, correlation with disease prognosis, and biological function of MRGs in SKCM were evaluated. Patients were categorized into three different clustering groups based on MRG expression data. We applied 101 machine learning algorithms to construct a prognostic model from the selected MRGs. This model demonstrated efficacy in forecasting the outcomes in patients with SKCM and analyzing the TME. The findings demonstrated the high precision and dependability of the model, and it was further validated using independent datasets from several public databases and performing cell-based experiments. Our prognostic model will significantly aid in evaluating the risk and prognosis of patients with SKCM in clinical settings.

Materials and methods

Transcriptome and clinical data download and organization

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA-SKCM), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession numbers: GSE3189, GSE46517, GSE114445, GSE54467, and GSE65904), the iMeng210 database (http://research-pub.gen.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies), and Tumor Immune Single-cell Hub 2 (TISCH2; http://tisch.comp-genomics.org/, containing datasets GSE115978, GSE120575, GSE134388, GSE159251, GSE123139, GSE139249, GSE148190, and GSE72056). Among these, three datasets (TCGA-SKCM, GSE54467, and GSE65904) contained complete follow-up information and were used for constructing machine learning models and calculating the concordance index (C-index) to evaluate associations between clinical characteristics, tumor microenvironment (TME), and metabolism-related genes (MRGs). TCGA-SKCM raw data were normalized to transcripts per million (TPM) values using R (v4.3.0). Batch effect correction was performed by merging two GEO datasets into a GEO-Meta cohort, followed by empirical Bayes-based batch adjustment using the ComBat algorithm, and a Log2 transformation using the sva R package to improve data distribution. Quality control was applied by retaining only cases with complete clinical information and definitive survival outcomes for subsequent analyses.

Identification and transcriptome analysis of MRGs in SKCM

MRGs (n = 2752), derived from previously published data20,21. The transcriptome data were merged and normalized using the “limma” and “sva” R packages to construct the prognostic model. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between nevus and melanoma samples were analyzed to select relevant genes from the set of 2752 MRGs and assess the association of these DEGs with overall survival, using selection criteria of P < 0.05 and |log2(Fold Change)| > 1. Statistically significant DEGs with prognostic relevance were then selected, resulting in the identification of 39 key MRGs (Supplementary Table S1). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)22,23,24 analyses were performed, focusing on the biological functions and metabolic pathways associated with the identified MRGs (Supplementary Table S2). Somatic mutation traits of these genes were visualized using the “maftools” package in R to create waterfall plots. Additionally, transcriptome and mutation data for these MRGs were retrieved from the TCGA database, and their copy number variation (CNV) frequencies and genomic distributions were examined. Differential expression analysis of MRGs in normal and melanoma tissues was conducted using the “limma” software package, with statistical significance confirmed by the Wilcoxon test. The relationship between MRGs and patient survival was analyzed using the log-rank test, and the interactions among MRGs were investigated through correlation studies.

Molecular subtype classification through clustering analysis of MRGs

Patients with SKCM were categorized into three distinct molecular subtypes based on the expression of 39 MRGs. The K-means clustering algorithm was applied to determine the optimal number of subtypes. Principal component analysis (PCA) was then performed in the R environment using the “limma” and “ggplot2” packages to distinguish the three MRG molecular subtypes and examine the variance in expression patterns across these subtypes.

Evaluation of clinical and biological characteristics in three MRG molecular clusters

Survival analyses were conducted using the R software packages “survival” and “survminer” to determine the prognostic outcome across three groups, which were based on different molecular subtypes of MRGs. The survival time disparities among these subtypes were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier (KM) curve analysis. The standard multiplicity shift was greater than 1.5 with a p-value of less than 0.05. In addition, the variability of immune checkpoint expression and TME in three different clusters was analyzed. The immune-related pathways among the unused clusters were explored using single-sample genome enrichment analysis.

Integration of machine learning algorithms for prognostic modeling and analysis

Three SKCM datasets were used for comparative analysis of machine learning models. A variety of machine learning methods were used to compute the combined scores, including Random Survival Forest (RSF), CoxBoost, StepCox, Least Absolute Selection and Shrinkage Operator (Lasso), elastic network (Enet), Ridge, partial least squares regression for Cox (plsRcox), supervised principal components (SuperPC), generalized boosted regression modeling (GBM) and Support Vector Machine (SVM). By calculating the consistency index (C-index) in each dataset, the predictive performance of each model was evaluated, and the models were ranked based on the average C-index across the three datasets. The model with the highest C-index was considered the best model25. Patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score of the model, and survival differences between these groups were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis and log-rank tests. Additionally, the model’s performance in feature prediction was assessed using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. A meta-analysis was performed on the three datasets, and the Hazard Ratio (HR) and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) for each study were calculated and reported.

Risk score for clinical application

Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportions of different clinicopathological features between high and low-risk groups, as depicted in pie charts. Additionally, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze the differences between different stages of the disease. Furthermore, to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the model at different time points, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used. the clinical information of patients in the TCGA-SKCM dataset was used to screen prognostic features by univariate and multivariate cox regression analysis, a nomogram model were constructed based on these prognostic features, and calibration graphs were used to evaluate the prediction efficiency.

Immune cell infiltration analysis in groups with high and low risk

The CIBERSORT algorithm was employed to quantify immune cell infiltration in SKCM tissue samples accurately, and a comprehensive Spearman rank correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationship between the relative abundance of immune cells and patient risk scores. Additionally, Variances in various immune-related scores, including stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores, were evaluated, and comparisons were made between these scores in high- and low-risk patient groups. And Pathology images from the TCGA database were analyzed to highlight differences in immune cell infiltration between low- and high-risk patient groups.

Z- score score analysis of biological processes in prognostic related genes

The expression levels of prognosis-related genes were analyzed to assess the levels of specific biological pathways using the z-score algorithm of the Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) software package in R. The analysis specifically focused on several key biological processes, including angiogenesis, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), and the cell cycle26. The levels of each pathway were quantified using the corresponding z-score values.

Prognostic genes were analyzed by online database

Database (http://TISCH.comp-genomics.org/) was used to examine the expression of protein-coding genes in various cell clusters. This analysis involved multiple single-cell melanoma datasets, Namely, GSE115978, GSE120575, GSE134388, GSE159251, GSE123139, GSE139249, GSE148190, and GSE72056. To understand how different cell clusters in the TISCH database influence the expression of protein-coding genes. The DepMap database (https://depmap.org/portal/) was used to analyze the expression levels of the GALNT2 gene across 39 melanoma cell lines. In addition, the differences in the GALNT2 gene expression in both healthy skin and tumor tissues were analyzed using the TCGA and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases.

Protein network construction and functional annotation analysis

GO and KEGG analyses were conducted to reveal the molecular features and biological processes potentially involving the GALNT2 gene (Supplymentary Table S6). The GeneMANIA database, which integrates extensive genomic and proteomic data, was used to explore the genes functionally similar to GALNT2. A network of functionally similar genes was predicted, and potential roles of GALNT2 in various biological contexts were identified.

Cell culture

MeThe cell lines used in this study were kindly provided by the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Metabolic Disease Research Center, School of Basic Medicine, Anhui Medical University. The experiment utilized the following three cell lines: Normal human melanocyte cell line (PIG1),Human melanoma cell lines (A2058 and A375).

All cell lines were cryopreserved in the laboratory liquid nitrogen tank. For routine culture, cells were maintained in DMEM complete medium (C0223; Beyotime, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-gentamicin antibiotic solution, and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was separated from the cells using TRIzol reagent (SparkZol Reagent, #AC0101-A, Shandong, China). RNA was converted into cDNA using the ToloScript RT EasyMix kit for reverse transcription. (TOLOBIO, #22106, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, qRT-PCR was conducted on a Bio-Rad CFX96 system using SYBR Green PCR master mix (TOLOBIO, #22204, China) to determine the target gene expression. The primer sequences used are listed in Supplementary Table S3.

Western blot assay

PIG1, A375, and A2058 cells were cultured in a suitable medium. Cells were allowed to grow at 90% confluence and washed twice with precooled PBS. Subsequently, cells were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. The extracted proteins were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and lysed for 15 min at 4 °C. Protein levels were measured using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime). Subsequently, equal amounts of proteins were separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a 0.45-µm pore size PVDF membrane (Millipore, MO, USA). After blocking the membranes with 5% skim milk solution for one hour, they were washed and incubated overnight with primary antibodies, including anti-GALNT2 (1:1000, Abcam(ab140637), Massachusetts, USA) and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 1:1000, Santa(sc-47724), Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) at 4 °C. The membranes were then washed and incubated with mouse/rabbit IgG coupled with horseradish peroxidase. Chemiluminescence was used to detect protein bands, and blots were imaged using the AlphaView analysis system (ProteinSimple Inc., MN, USA).

Cell transfection

The cells were seeded in 6-well plates (Corning, USA), and when the cell confluence reached 60%, overexpression plasmids and knockdown siRNAs (siRNA target sequences as follows: GALNT2 siRNA-1: 5′-GAGAGUGAUAAGCUUCGAA-3′, GALNT2 siRNA-2: 5′-GACAGUCACUGCGAGUGUA-3′) were synthesized by Qingke Biotechnology and Heyuan Bio, and transfection was carried out according to the instructions of Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies, CA, USA).After 48 h of transfection, the cells were harvested for subsequent experiments.Total protein was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, China), and Western blotting was used to detect GALNT2 protein expression levels (primary antibody dilution 1:1000, incubated overnight at 4 °C; HRP-conjugated secondary antibody 1:5000, incubated for 1 h at room temperature).

Edu assay

A375 and A2058 cells from various treatment groups were seeded into twelve-well plates and allowed to grow until 70% confluence. The cells were then cultured in 1× EdU solution for 2 h. Subsequently, cells were immobilized with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min and rinsed thrice in a BSA rinse solution. EdU Cell Proliferation Image Kit and 1× Hoechst 33,342 (Abbkine, #KTA2030, Wuhan, China) were used to perform staining. Finally, fluorescence microscopy was used to observe and document proliferating cells.

Colony formation assay

The cells from various groups were inoculated into six-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 to determine the effect of GALNT2 on melanoma cell colony formation. After 10 days of incubation, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Finally, the fixed cells were immersed in 1% crystal violet for approximately 20 min. Photographs were taken and statistical comparisons were performed using imagej.

Wound healing assay

Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and cultured in complete medium with 10% FBS. When the cell confluence reached 80%-90%, a scratch was made using a 200 µl pipette tip. After PBS washing, the medium was replaced with 1% FBS low-serum medium.The scratch area was captured at 0 h and 24 h, and the cell migration rate was calculated using ImageJ software (migration rate = (0 h scratch area − 24 h scratch area) /0 h scratch area×100%).The experiment was performed with three biological replicates, and the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Transwell assay

Cell migration assays were performed using Transwell chambers (Corning Incorporated, New York, USA). Pre-transfected A375 and A2058 cells were resuspended in serum-free medium at a density of 5 × 10⁴ cells/mL, and 200 µL of the cell suspension was seeded into the upper chamber of the Transwell system. The lower chamber was filled with medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) as a chemoattractant. After incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 48 h, the chambers were carefully removed. Non-migrated cells on the upper side of the membrane were gently wiped away with a cotton swab. The migrated cells on the lower side of the membrane were fixed with 4% polyformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Multiple random fields were photographed under a microscope for subsequent quantitative analysis.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment in this study was independently repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD) to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results.Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 10 software.The differences between the two groups were analyzed using an independent t-test.The significance level for statistical analysis was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Genetic and transcriptional alterations of MRGs in SKCM

We examined the clinical information of patients (Supplementary Table S4) and analyzed somatic mutation rates of MRGs in these patients (Fig. 1A). We then investigated the roles of MRGs in biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF) using GO and KEGG analyses (Fig. 1B). MRGs were significantly enriched in biological processes, such as alcohol metabolism, amino acid transmembrane transport, and neutral amino acid transport. In cellular components, MRGs were mainly found in the basal cell area and basolateral plasma membrane. Functionally, these genes were associated with active transmembrane transporter activity and transmembrane transport of organic acids and carboxylic acids. KEGG analysis highlighted the enrichment of MRGs in pyrimidine metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, and mineral adsorption (Fig. 1B), underscoring their involvement in metabolic processes and cell membrane structure. In addition, we analyzed the CNVs of MRGs in SKCM (Fig. 1C). TK1, ABCA5, CH13L1, NME1, ABCC3, ATP1B1, and GALNT2 showed an increase in CNVs, whereas SLC27A2, QPRT, G6PC3, and SLC7A5 showed a decrease in CNVs. Figure 1D presents the distribution of these CNVs on human chromosomes. Additionally, we compared the expression levels of MRGs between normal and tumor tissues using the TCGA database (Fig. 1E) and constructed a network to illustrate their’ interactions and prognostic significance (Fig. 1F).

Genetic and transcriptional alterations and functional analysis of MRGs in SKCM. (A) Analysis of somatic mutation rates across 39 melanoma-related genes (MRGs) in patients with SKCM, highlighting the genetic variability within this cohort. (B) Functional enrichment analysis of MRGs using GO and KEGG pathways. (C) Frequency of CNV gain and loss in MRGs. (D) Orientation of CNV changes in MRGs across 23 chromosomes. (E) Comparative expression profiles of MRGs between normal skin and SKCM samples. (F) Network diagram depicting interactions among MRGs in SKCM. Lines between genes represent their interrelations; pink indicates positive correlations, whereas blue indicates negative correlations. (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001).

Identification and transcriptome analysis of MRGs in SKCM

Patients with SKCM were grouped into three clusters based on the expression patterns of MRGs using a consensus clustering method (Fig. 2A). PCA was used to determine the distinction between these MRG clusters (Cluster A, B, and C; Fig. 2B). KM curves showed that patients in MRG cluster C had a better prognosis (Fig. 2C). The heatmap revealed the gene expression patterns of different MRG clustering groups and their associated clinical features (Fig. 2D). Upon conducting a comprehensive analysis of TME scores, immune checkpoint expression, and immune cell infiltration levels across three MRG clusters, Cluster C exhibited higher scores (Fig. 2E). In addition, we further explored the relevant enrichment pathways among different MRG clusters using the GSVA method (Fig. 2F-H).

Clustering and clinical characterization of MRGs and the immune microenvironment in SKCM samples. (A) Three clusters of MRGs were analyzed using consistent clustering. (B) Differences between the three clusters were analyzed using PCA. (C) KM survival curves indicated significant differences among the three clusters (P < 0.001). (D) Heatmap of MRG clusters correlated with clinical features and gene expression in patientspatients with SKCM. (E) Differences among the three clusters between immune checkpoints and immune cell infiltration in SKCM tumor samples. (F–H) GSVA results indicating pathway enrichment between two distinct clusters.

Construction and validation of prognostic models related to MRGs

We incorporated 39 MRGs into 10 machine learning algorithm within the framework of Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV). The C-index of the program was calculated for the model in the data to test the prediction efficiency. The best model portfolio consisting of RSF and step-wise Cox regression methods achieved the maximum mean C-index of 0.629 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, we constructed a model comprising six key genes (MRGs) (Supplementary Table S5). The univariate Cox regression analysis with HRs revealed that SLC27A2 and HSD11B1 are potentially protective (HR < 1), whereas QPRT, NME1, MCAL2, and GALNT2 may negatively influence prognosis in SKM (HR > 1) (Fig. 3B). We then calculated a risk score from the expression levels and coefficients of these six genes: Risk Score = [Expression of SLC27A2 × (-0.32901)] + [Expression of HSD11B1 × (-0.07997)] + [Expression of QPRT × (0.07336)] + [Expression of NME1 × (0.16097)] + [Expression of MCAL2 × (0.12810)] + [Expression of GALNT2 × (0.16827)]. Patients were separated into high and low risk categories according to the median risk score, with higher scores being associated with greater mortality rates (Fig. 3C). The analysis of KM curves revealed a significantly worse prognosis for patients in the high-risk group compared to those in the low-risk group within the validation set (Figs. 3D-F). Further, the Area Under Curve (AUC) values for MRGs across 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival duration validated the reliability and accuracy of MEGs in prognosis, showing their high specificity and sensitivity (Figs. 3G-I). A meta-analysis of the three datasets yielded a combined HR of 3.06 with 95% CI, indicating a three-fold increase in risk associated with the study parameters and low heterogeneity among datasets, suggesting high consistency (Fig. 3J).

Construction and validation of MRG-based prognostic models derived after integrated machine learning algorithms. (A) 101 predictive models were developed using LOOCV, and their C-indexes were calculated in the validation dataset. (B) Independent prognostic relationships of modeled genes were analyzed using univariate COX. (C) Risk levels and survival outcomes for each instance. (D–F) KM survival curves in each dataset. (G–I) and 1-, 3- and 5-year ROC scores. (J) Forest plot demonstrating meta-analysis of the three datasets.

MRGs for clinical applying

Pie charts revealed a higher tendency of advanced pathological stages and increased mortality risks in the high-risk group (Fig. 4A). The risk score positively correlates with disease progression (Fig. 4B-C). 1-, 3-, and 5-year ROC curves over various time points were utilized to compare clinical information and staging of patients, with the AUC values being calculated (Fig. 4D-F). The variables with a P-value below 0.05 (Fig. 4G) in the initial univariate analysis were considered for the subsequent multivariate analysis (Fig. 4H). Several factors remained statistically significant: tumor size (T) with P < 0.001, HR of 1.4901, and 95% CI of 1.265–1.755; lymph node status (N) with P < 0.001, HR of 1.733, and 95% CI of 1.369–2.196; and risk score with P < 0.001, HR of 2.279, and 95% CI of 1.490–3.487. These three parameters were subsequently incorporated into the final nomogram model (Fig. 4I). And the alignment plot illustrated a strong correspondence between the projected survival percentages and the real survival percentages (Fig. 4J).

Efficiency of using risk score assessments to predict patient prognosis and construct nomogram models. (A) Pie chart demonstrating the Chi-square test for clinicopathological features across high- and low-risk patient groups. Relationship of clinical staging (B) and T-staging (C) to risk scores. 1-, 3-, and 5-year ROC curves of the risk score and other clinicopathologic features (D–F). Forest plots displaying (G) univariate and (H) multivariate Cox regression analyses in patients with SKCM. (I) Development of nomogram models incorporating risk scores and key clinical parameters. (J) Calibration plots evaluating the discrepancy between forecasted and observed survival outcomes.

Immune response and risk score correlation in tumor therapy

Scores for risk groups and correlation scores for the infiltration of 10 distinct immune cells were analyzed, revealing a significant correlation (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). Additionally, a relationship was observed between six genes linked to prognosis and the risk scores (Fig. 5B). The analysis was extended to stromal, immune, and ESTIMATE scores across groups with varying risk levels (Fig. 5C). The groups at low-risk consistently outperformed their high-risk counterparts in all three scoring categories (P < 0.01). Further, analysis of TCGA pathology sections showed that the level of immune cell infiltration was higher in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group (Fig. 5D). In addition, the immune predictive scores (IPS) were compared across both patient groups. It was observed that the IPS was notably higher in low-risk patients undergoing various forms of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy (P < 0.01; Supplementary Figure S1). This suggests that patients categorized as low risk may have an enhanced reaction to immune checkpoint inhibition therapy.

Comparative analysis of the tumor immune microenvironment in high- versus low-risk groups. (A) Exploring of the association between risk scores and various immune cell types. (B) Analysis of the link between immune cell prevalence and six genes within the prognostic model. (C) Examination of the relationship between risk score and immune-related score. (D) TCGA pathology sections showing higher tumor immune cell infiltrations in low-risk patients compared with those in high-risk patients (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001).

MRG signature and the malignant characteristics of the tumor

The hallmark features, such as rapid cell proliferation, marked EMT, and increased angiogenesis, play a significant role in defining the aggressive behavior of the cancer during the transition from normal cells to malignant tumors. Furthermore, alterations in metabolic genes are linked to an increased likelihood of melanoma onset. We used a z-score algorithm to quantify tumor activity in MRG promotion, angiogenesis, EMT, and cell cycle to clarify the relationship between MRGs and malignant tumors. We analyzed the comprehensive cancer cohort of TCGA (Figs. 6A) and published studies across most tumor types (Figs. 6B-C) and found a strong positive correlation between MRG z-scores and both angiogenesis (R = 0.67; P < 0.0001) and EMT (R = 0.51; P < 0.0001) z-scores. However, a negative correlation was observed with cell cycle z-scores (R = -0.24; P < 0.0001). In the context of SKCM, MRGs were positively correlated with angiogenesis (R = 0.67; P < 0.0001) and EMT (R = 0.42; P < 0.0001). Overall, MRGs were associated with increased angiogenesis and an aggressive cellular environment in SKCM tumor.

Experimental validation of MRGs identified in Multi-Dataset transcriptomic analysis

We analyzed prognosis-related MRGs using the TISH database, with careful consideration of cell-type specificity. Gene expression patterns were evaluated across immune cell types in multiple datasets, including GSE115978, GSE120575, GSE134388, GSE159251, GSE123139, GSE139249, GSE148190, and GSE72056. Prognosis-associated genes showed consistent distribution profiles across these independent cohorts (Fig. 7A-I). To experimentally validate key genes from the prognostic model, we performed qRT-PCR in melanocyte PIG1 and melanoma cell lines A375 and A2058. Results confirmed that expression of GALNT2 and HSD11B1 was significantly upregulated in melanoma cells compared with normal melanocytes (Supplementary Figure S2).

Functional enrichment analysis of GALNT2 and its effect on malignant phenotype in melanoma cells

GALNT2 expression levels were positively correlated with poor prognosis in tumor patients. We used GeneMANIA to analyze the molecular interactions of GALNT2 and the potential roles of GALNT2. The network (Fig. 8A) highlighted the primary functions of the gene in protein O-linked glycosylation and interactions with C1GALT1 and MUC family members (such as MUC4, MUC7, MUC16, and MUC17). DepMap analysis indicated that GALNT2 gene expression was generally increased in 39 melanoma cell lines (Fig. 8B). Concurrently, GO (Fig. 8C) and KEGG (Fig. 8D) enrichment analyses were used to investigate the potential biological functions of GALNT2 (Supplementary Table S6). GO functional enrichment analysis indicated that BPs were predominantly involved in small GTPase-mediated signal transduction, proteasome-mediated ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic processes, and cellular component disassembly. CC were primarily enriched in cell–substrate junctions, focal adhesions, and the mitochondrial matrix. MF were significantly enriched in protein serine/threonine kinase activity, DNA-binding transcription factor binding, and GTPase regulator activity. KEGG analysis predominantly linked these functions to the cell cycle, apoptosis, MAPK signaling, and sphingolipid signaling pathways. Furthermore, we further explored the role of GALNT2 in the development of cutaneous melanoma. Immunohistochemical data was downloaded from the HPA database to preliminarily assess the differences in GALNT2 expression in normal skin tissue and melanoma tissue samples. The results showed that GALNT2 expression was higher in melanoma tissue samples compared with that in normal skin tissue (Fig. 8E). We then explored the difference in GALNT2 expression in normal melanocytes (PIG1) and melanoma cell lines (A375 and A2058) using western blotting. The results showed a significant increase in the expression of GALNT2 in PIG1 compared with that in A375 and A2058 (Fig. 8F). In addition, further analysis of the GTEx and TCGA datasets comprising 233 normal skin samples and 237 melanoma tissue samples showed that the GALNT2 gene expression was significantly higher in melanoma than in the normal tissues (Fig. 8G).

Functional analysis of the GALNT2 gene in normal melanocytes and tumor cells. (A) Target protein candidate biomarker prediction for GALNT2 PPI network diagram; different colors represent different functional networks. (B) GALNT2 expression in 39 melanoma cell lines. (C) Functional enrichment analysis of GALNT2 using GO (D) and KEGG (E) pathways. (E) Immunohistochemical staining showing the expression of the GALNT2 protein in normal and melanoma tissues. (F) Western blotting was performed to analyze the expression of the GALNT2 protein in PIG1, A375, and A2058 cells. (G) GALNT2 expression in normal skin tissues and tumor tissues. (*p < 0.05,**p < 0.01,****p < 0.0001).

Knockdown of GALNT2 inhibited cell proliferation and migration capacity

we constructed knockdown GALNT2 siRNAs and transfected them into A375 and A2058 cell lines. The transfected siRNAs were categorized as siRNA-1, siRNA-2, and Ctrl and western blot was used to assess the expression efficiency (Fig. 9A-B).The effect of siGALNT2 on the proliferative capacity of A375 and A2058 cell lines was evaluated using Edu (Fig. 9C-D) and colony formation (Fig. 9E-F) assays. The results revealed a significant reduction in cell proliferation in the siGALNT2 group compared to the Ctrl group. Additionally, wound healing (Fig. 9G-H) and Transwell (Fig. 9I-J) assays were performed to assess the impact of siGALNT2 on cellular migration. The findings demonstrated a notable decrease in the migration abilities of cells treated with siGALNT2.

Knockdown of GALNT2 inhibited cell proliferation and migration capacity. Edu assays. Western blotting was performed to assess the transfection efficiency of GALNT2 in A375 and A2058 cells (A,B). Edu assays (C,D) and colony formation assays (E,F) were performed to assess the effect of siGALNT2 expression on A375 and A2058 proliferation. Wound healing assays (G,H) and Transwell assays (I,J) were performed to assess the effect on A375 and A2058 migration after interfering with GALNT2 expression. (**p < 0.01,***p < 0.001).

Overexpression of GALNT2 promoted cell proliferation and migration capacity

In contrast, to investigate the effect of GALNT2 overexpression, we constructed GALNT2 overexpression plasmids and transfected them into A375 and A2058 cell lines. The transfected plasmids were categorized as oe-GALNT2- and oe-Ctrl, and western blot was used to assess the expression efficiency (Fig. 10A-B). the proliferative capacity of A375 and A2058 cells was assessed following GALNT2 overexpression using Edu (Fig. 10C-D) and colony formation (Fig. 10E-F) assays. The results showed a significant increase in cell proliferation in the oe-GALNT2 group compared to the oe-Ctrl group, indicating that GALNT2 overexpression promotes cell proliferation. Furthermore, to examine the effect of GALNT2 overexpression on cellular migration, we conducted wound healing (Fig. 10G-H) and Transwell (Fig. 10I-J) assays. These results revealed a marked enhancement in the migration abilities of cells subjected to GALNT2 overexpression.

Overexpression of GALNT2 promoted cell proliferation and migration capacity. Edu assays. Western blotting was performed to assess the transfection efficiency of GALNT2 in A375 and A2058 cells (A,B). Edu assays (C,D) and colony formation assays (E,F) were performed to assess the effect of GALNT2 overexpression on A375 and A2058 proliferation. Wound healing (G,H) and Transwell assays (I,J) were performed to assess the effect on A375 and A2058 migration after GALNT2 overexpression.(*p < 0.05,**p < 0.01,***p < 0.001).

Discussion

Metabolic reprogramming is a hallmark of cancer, enabling tumor cells to sustain uncontrolled proliferation and adapt to hostile microenvironments27. In cutaneous melanoma, metabolic alterations have been strongly associated with tumor progression, mutational burden, and patient survival28,29. While considerable attention has been devoted to pathways such as glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, glycosylation-related enzymes—key regulators of protein stability and signaling—remain largely unexplored in melanoma30,31. Given their emerging roles in shaping tumor behavior in other cancers, systematic evaluation of glycosylation enzymes in melanoma may provide new insights into metabolic vulnerabilities and prognostic markers32,33. To address this gap, we established and validated a metabolism-based prognostic model for cutaneous melanoma.

This study comprehensively profiled the transcriptional levels and mutation landscape of 39 MRGs. These three clusters showed different clinical outcomes. The TME deconvolution analysis showed a notably greater infiltration of immune cells in Cluster C compared to that in other subtypes. This encompasses crucial immune cells, such as cytotoxic T cells, helper T cells, B/plasma cells, and macrophages/monocytes34. Notably, these cells play an integral role in the immune defenses against tumors35. CD4 + T cells can either enhance or suppress immune responses against tumors by identifying antigens presented by HLA class II molecules33. In contrast, myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to tumor growth by suppressing the immune response mediated by T and natural killer cells against the tumor34.The RSF + StepCox model yielded the highest mean C-index among the ten machine learning algorithms evaluated for constructing an MRGs-related signature. According to the median value of the risk score, patients were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups. A comparative analysis across three datasets revealed that high-risk MRGs were associated with a poor prognosis. Having established the risk score as a significant prognostic factor in both univariate and multivariate Cox analyses, we integrated it with established clinical staging factors. The resulting model demonstrated high predictive efficiency.

TME is crucial in cancer progression. Beyond stromal cells, its composition encompasses fibroblasts, endothelial cells, as well as innate and adaptive immune cells36,37. The risk score showed a positive correlation with two specific types and a negative correlation with the other eight types within the diverse range of immune cells. The scores related to immunity significantly influence the outcomes of both immunotherapy and chemotherapy38. The patient group with lower risk exhibited superior scores pertaining to the TME, and showed increased IPS scores associated with immune checkpoint blockade therapy. This implies enhanced immune infiltration in the low-risk group, potentially leading to more effective responses in immunochemotherapy.

Among the six key genes screened based on the C-index, we observed mRNA expression abnormalities in four of them in melanoma cells. We selected GALNT2 as the core subject for subsequent in-depth investigation: Firstly, analysis of TCGA and GTEx data revealed that GALNT2 expression was significantly upregulated in melanoma tissues, and its high expression was closely associated with poor patient prognosis, suggesting important clinical implications. Secondly, single-cell transcriptome analysis high expression of GALNT2 in CD8+ T cell subsets, implying its potential involvement in regulating the tumor immune microenvironment. Additionally, GO/KEGG enrichment analysis demonstrated that GALNT2 was significantly enriched in melanoma-related pathways such as the MAPK signaling pathway and cell cycle regulation, providing direction for its functional mechanisms. Although GALNT2 has been reported to promote malignant progression through pathways such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK in tumors including non-small cell lung cancer, cervical cancer, and gastric cancer39,40,41, and is considered a potential therapeutic target42, its role in melanoma remains unclear. Therefore, we performed functional validation. In vitro experiments showed that knockdown of GALNT2 significantly inhibited the proliferation and migration abilities of melanoma cells, while its overexpression promoted these phenotypes. Consequently, our results suggest that GALNT2 may serve as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for SKCM patients.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis was primarily based on publicly available databases and retrospective sample collection, which may introduce selective bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, although the study provided functional insights into the effects of GALNT2 silencing and overexpression in melanoma cell lines, the lack of clinical tissue samples restricts our ability to validate these findings in a clinical setting. Additionally, the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed effects remain unclear, and further mechanistic studies are required to better understand how GALNT2 regulates melanoma progression. Lastly, in vivo experiments are needed to confirm the findings observed in cell culture models, as they may not fully recapitulate the complex in vivo tumor microenvironment and could provide critical insights into the therapeutic potential of GALNT2 in SKCM. In future research, we plan to address these limitations by incorporating clinical tissue samples and conducting in vivo studies to further explore the role of GALNT2 in melanoma and its potential as a therapeutic target.

Conclusion

We comprehensively analyzed the role of MRGs in SKCM and constructed a prognostic model by multiple machine learning algorithms. This model effectively predicts the clinical survival of SKCM patients, in their immune infiltration and responses to immunotherapy and chemotherapy. These findings may provide valuable insights for enhancing the diagnosis and treatment strategies for SKCM. Furthermore, the results confirmed that the key gene GALNT2 promotes melanoma cell proliferation and migration.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the current study are available in the TCGA(SKCM-TCGA) and GEO(GSE3189, GSE46517, GSE114445, GSE54467, and GSE65904)repositories, (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga), (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Abbreviations

- SKCM:

-

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- MRGs:

-

Metabolism-related genes

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- TCGA:

-

The cancer genome atlas

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- BP:

-

Biological processes

- CC:

-

Cellular components

- MF:

-

Molecular functions

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- CNV:

-

Copy number variation

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- KM:

-

Kaplan–Meier

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EMT:

-

Pithelial to mesenchymal transition

- GSVA:

-

Gene set variation analysis

- IPS:

-

Immune predictive scores

- ssGSEA:

-

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis

- GTEx:

-

Genotype-tissue expression

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- RSF:

-

Random survival forest

- Lasso:

-

Least absolute selection and shrinkage operator

- Enet:

-

Elastic network

- plsRcox:

-

Partial least squares regression for Cox

- SuperPC:

-

Supervised principal components

- GBM:

-

Generalized boosted regression modeling

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

References

Che, G. et al. Trends in incidence and survival in patients with melanoma, 1974–2013. Am. J. Cancer Res. 9, 1396–1414 (2019).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., Jemal, A. & Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 7–33. (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. Spindle cell melanoma: incidence and survival, 1973–2017. Oncol. Lett. 16, 5091–5099 (2018).

Arnold, M. et al. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 158, 495 (2022).

Rastrelli, M., Tropea, S., Rossi, C. R. & Alaibac, M. Melanoma: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. Vivo 28, 1005–1011 (2014).

MacKie, R. M. Incidence, risk factors and prevention of melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 34, 3–6 (1998).

Guo, W., Wang, H. & Li, C. Signal pathways of melanoma and targeted therapy. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 424 (2021).

Tsao, H. & Niendorf, K. Genetic testing in hereditary melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 51, 803–808 (2004).

Volkovova, K., Bilanicova, D., Bartonova, A., Letašiová, S. & Dusinska, M. Associations between environmental factors and incidence of cutaneous melanoma. Rev. Environ. Health. 11, S12 (2012).

Brăniteanu, D. E. et al. Differences and similarities in epidemiology and risk factors for cutaneous and uveal melanoma. Med. (Mex). 59, 943 (2023).

Kumar, K. et al. Integrating Multi-Omics data to construct reliable interconnected models of Signaling, gene Regulatory, and metabolic pathways. Methods Mol. Biol. 2634, 139–151 (2023).

Sompairac, N. et al. Metabolic and signalling network maps integration: application to cross-talk studies and omics data analysis in cancer. BMC Bioinf. 20, 140 (2019).

Peng, X. et al. Molecular characterization and clinical relevance of metabolic expression subtypes in human cancers. Cell. Rep. 23, 255–269e4 (2018).

Martínez-Reyes, I. & Chandel, N. S. Cancer metabolism: looking forward. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 21, 669–680 (2021).

Vander Heiden, M. G. & DeBerardinis, R. J. Understanding the intersections between metabolism and cancer biology. Cell 168, 657–669 (2017).

Vander Heiden, M. G., Cantley, L. C. & Thompson, C. B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324, 1029–1033 (2009).

You, M. et al. Signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 196 (2023).

Jiang, L. et al. Metabolic reprogramming during TGFβ1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 34, 3908–3916 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. Metabolic heterogeneity and immunocompetence of infiltrating immune cells in the breast cancer microenvironment (Review). Oncol. Rep. 45, 846–856 (2021).

Yang, C., Huang, X., Liu, Z., Qin, W. & Wang, C. Metabolism-associated molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 14, 896–913 (2020).

Possemato, R. et al. Functional genomics reveal that the Serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature 476, 346–350 (2011).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D457–D462 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30 (2000).

Liu, Z. et al. Machine learning-based integration develops an immune-derived LncRNA signature for improving outcomes in colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 13, 816 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. A signature for pan-cancer prognosis based on neutrophil extracellular traps. J. ImmunoTher Cancer. 10, e004210 (2022).

Bhalla, S., Kaur, H., Dhall, A. & Raghava, G. P. S. Prediction and analysis of skin cancer progression using genomics profiles of patients. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–16 (2019).

Newcomer, K. et al. Malignant melanoma: evolving practice management in an era of increasingly effective systemic therapies. Curr. Probl. Surg. 59, 101030 (2022).

Tasdogan, A. et al. Metabolic heterogeneity confers differences in melanoma metastatic potential. Nature 577, 115–120 (2020).

Xia, L. et al. The cancer metabolic reprogramming and immune response. Mol. Cancer. 20, 28 (2021).

Munkácsy, G., Santarpia, L. & Győrffy, B. Therapeutic potential of tumor metabolic reprogramming in Triple-Negative breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6945 (2023).

Iglesia, M. D. et al. Genomic analysis of immune cell infiltrates across 11 tumor types. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108, djw144 (2016).

Sallusto, F. & Lanzavecchia, A. Heterogeneity of CD4+ memory T cells: functional modules for tailored immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 2076–2082 (2009).

Ozbay Kurt, F. G., Lasser, S., Arkhypov, I., Utikal, J. & Umansky, V. Enhancing immunotherapy response in melanoma: myeloid-derived suppressor cells as a therapeutic target. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e170762 (2023).

Anderson, N. M. & Simon, M. C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr. Biol. 30 (16), R921–R925 (2020).

Hinshaw, D. C. & Shevde, L. A. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 79, 4557–4566 (2019).

Bruni, D., Angell, H. K. & Galon, J. The immune contexture and immunoscore in cancer prognosis and therapeutic efficacy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 20, 662–680 (2020).

Emens, L. A. & Middleton, G. The interplay of immunotherapy and chemotherapy: Harnessing potential synergies. Cancer Immunol. Res..

Hu, Q. et al. The O-glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 acts as an oncogenic driver in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 27, 71 (2022).

Sun, Z. et al. Mucin O-glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 facilitates the malignant character of glioma by activating the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR axis. Clin. Sci. 133, 1167–1184 (2019).

Hu, W-T., Yeh, C-C., Liu, S-Y., Huang, M-C. & Lai, I-R. The O-glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 suppresses the malignancy of gastric adenocarcinoma by reducing EGFR activities. Am. J. Cancer Res. 8, 1739–1751 (2018).

Yue, J., Huang, R., Lan, Z., Xiao, B. & Luo, Z. Abnormal glycosylation in glioma: related changes in biology, biomarkers and targeted therapy. Biomark. Res. 11, 54 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Bullet Edits Limited for their editorial and proofreading assistance. Our heartfelt thanks also go to TCGA, GEO, GTEx, TISCH, GeneMANIA, and the DepMep Data Platform and their contributors for providing essential data and information that greatly supported our research.

Funding

The research received funding from Key Research and Development Program of Anhui Province, through grant number 2022AH040163, Health Research Program of Anhui Province, through grant number AHWJ2023A20079 and Key Program of Education Department of Anhui Province, through grant number 2022AH052318.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CW and JJC made significant contributions to the manuscript’s drafting and submission process, alongside with performing the experiments.XW, XYL and XD were responsible for data collection and statistical analysis. SLY and YG focused on the visualization of data. The final review of the submission was conducted by CW, while HBZ and SXL provided essential guidance on the design and execution of the experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Chen, J., Ding, X. et al. Establishing and validating a new metabolic marker-driven prognosis signature for cutaneous melanoma. Sci Rep 15, 43045 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26955-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26955-5