Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) poses a significant global health burden with limited therapeutic efficacy. Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) offer multi-target potential, yet their systematic screening and mechanistic elucidation remain challenging. We established a high-throughput multi-omics platform integrating transcriptomics, proteomics, and deep learning (autoencoder and multiple kernel learning) to screen 187 medicinal plants. Five CHMs candidates were identified and shown to modulate hub genes (e.g., AKR1B10, HMGCR, THBS1) and key pathways (TNF/IL-17/MAPK, apoptosis, ferroptosis). Proteomic validation and functional assays confirmed their roles in suppressing proliferation, migration, and inducing apoptosis in HCC cells. This study provides a robust, data-driven pipeline for natural anti-HCC drug discovery, linking specific hub genes to CHM efficacy and offering novel insights into precision ethnopharmacology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer persists as a major cause of global mortality, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) posing a significant public health burden. In 2022, HCC was responsible for approximately 866,136 new cases and ranked as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, exhibiting a disproportionately high incidence in Asia, particularly in China1. Current standard treatments—including surgical resection, transplantation, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and immunotherapy—are often compromised by drug resistance, systemic toxicity, and metastatic recurrence2. These challenges highlight the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies that offer improved efficacy and reduced side effects.

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) has gained increasing attention as a complementary modality due to its multi-component, multi-target nature, which may synergize with conventional therapies to alleviate toxicity and enhance clinical outcomes3,4. Numerous medicinal plants, such as Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim., Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge., Panax ginseng., Euphorbia pekinensis Rupr., Forsythia suspensa., Aristolochia debilis Siebold. & Zucc, Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge. among others, have shown anticancer potential. Bioactive constituents including terpenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, and quinones exert antitumor effects through the modulation of apoptosis, cytokine signaling, and metabolic pathways5,6. However, the systematic identification of active compounds and their mechanisms of action remains challenging, necessitating advanced and efficient screening platforms.

High-throughput transcriptomic and proteomic technologies have revolutionized natural product research by enabling comprehensive profiling of gene expression and protein interactions, thus accelerating the elucidation of phytochemical mechanisms7,8. The integration of machine learning further augments the predictive power of omics data, as evidenced by recent studies applying single-cell RNA sequencing and xenograft models to evaluate drug responses,9,10,11 In particular, deep learning (DL) approaches such as autoencoders (AE) and multiple kernel learning (MKL) have emerged as powerful tools for extracting meaningful biological patterns from complex datasets, facilitating drug repositioning and mechanistic clustering12,13. For example, a dual-omics screening platform applied to breast cancer revealed herbal extracts that modulate apoptosis and NF-κB/MAPK signaling, enabling prioritization of promising candidates10. Similarly, integrated machine learning identified neuroactive drugs targeting a Ca2⁺-dependent AP-1/BTG pathway in glioblastoma, illustrating the potential of computational approaches in uncovering novel therapeutic vulnerabilities11.

In this study, we employed an integrated DL-enhanced omics framework to screen 187 medicinal plant extracts for anti-HCC activity. By combining high-throughput transcriptomics and proteomics with AE and MKL modeling, we identified conserved regulatory modules and hub genes associated with metastasis and inflammation. Proteomic validation and functional assays further confirmed the therapeutic potential of selected candidates. Our work establishes a robust, data-driven pipeline for natural anticancer drug discovery and provides new insights into the mechanistic basis of CHM in liver cancer treatment.

Material and methods

Preparation and selection of medicinal plant extracts

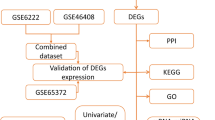

In this study, the initial selection of medicinal plants was based on literature reports retrieved from databases such as PubMed and CNKI. Plants with preliminary documented anti-inflammatory or antitumor activities, or those known to be rich in bioactive constituents such as alkaloids, terpenoids, and flavonoids, were included (Supplementary Table 1). The selected medicinal plants were procured and processed into fine powder by the Guangxi Key Laboratory of Medicinal Resources Protection and Genetic Improvement. Each sample was assigned a unique identifier according to the extraction method: sample “W” was prepared by hot water immersion followed by freeze-drying; sample “GX” was obtained through ethanol extraction, purification via resin column chromatography, and vacuum concentration; and sample “S” was produced by supercritical CO₂ extraction followed by sequential solvent extraction and vacuum drying. Detailed extraction procedures are provided in Supplementary Fig. 6, 7, 8. Ten commercial anticancer drugs were used as positive controls (Table 1). All samples and controls were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for bioactivity assays evaluating anticancer efficacy. Based on their pharmacological profiles, the medicinal plants were categorized into 20 groups, with group details available in Supplementary (Table 1). The overall workflow for screening and validation of medicinal plants in this study is summarized in (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Cell culture and drug preparation

The HepG2 cell line was provided by the Key Laboratory of Phytochemistry and Natural Medicines, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37 °C containing 5% CO₂. Subculturing was performed when the cells reached 80–90% confluency, using 0.25% trypsin for detachment. Cell viability was assessed 24 h post-treatment using a standard viability assay (Supplemental Fig. 1). Initial screening of the 187 medicinal plant extracts was performed at a concentration of 100 mg/mL, with subsequent concentration adjustments based on viability thresholds. Screening concentrations for transcriptome sequencing were determined based on cell viability approaching 80%. In this study, the anticancer drug was used as the positive control group, the medicinal plant was the experimental group, and the negative control was treated with 0.1% DMSO.

Difference analysis, functional analysis and heatmap of key gene expression. (A) the variance analysis volcano map, and the Y axis is the average log2FC. a measure that indicates whether the statistical test is statistically significant; the abscissa is indicated for each fraction-treated group and the positive drug group, and the identified genes are the core genes screened in each treatment group. The orange dots in the figure are the up-regulated genes for which p < 0.05 and |log2fc|≥ 1, the blue dots in the figure are the down-regulated genes for which p < 0.05 and |log2fc|≥ -1, and the other genes that do not meet the up-regulation and down-regulation thresholds are the gray dots in the figure. (B) the GO enrichment of differential genes, the outermost circle is GO term, and the size of the middle point is the gene count value. (C) the changes in gene expression in the core pathway after different fraction treatments. The line chart on the left is a clustering of all core genes, and 8 clusters are determined according to the inflection point. Gene expression and function classification diagram of the pathways associated with the fraction experimental group, blank control group and positive control group, and the violin diagram on the left represents the proportion of gene expression of each component in the cluster. The intermediate heatmap shows the change in gene expression of each component; on the right is a comment on the cluster function. (D) Deep learning and positive control comparison to screen medicinal plants, the relationship between three sets of conditions, one of which represents a set, and the number represents the number of intersecting elements in each region.

Cellular MTT assay

HepG2 cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates, incubated for 24 h, and treated with anti-cancer drugs (5 μg/mL) as positive control,while, gradient concentrations of medicinal plants as experimental group. After 24 h, cell viability was assessed using MTT assay14, with absorbance measured at 490 nm. Apoptosis was evaluated using Annexin V-FITC/PI staining followed by flow cytometry analysis15. (Supplemental Fig. 3E).

Wound healing assay

HepG2 cells were cultured in 6-well plates. When the cells reached almost 90% confluence, they were scratched directly. The cells were then treated with different concentrations of stigmas for 24 h16. Cell migration activity was photographed at 0 and 24 h, and the quantified values were compared via ImageJ (version 2.0.0) (Supplemental Fig. 3D).

Transcriptomic sequencing analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the FastPure Mini Kit, with RNA integrity confirmed by NanoDrop 2000 and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (RIN > 8, OD260/280: 1.8–2.0). cDNA libraries were prepared using the MGIEasy kit and sequenced on the BGISEQ-2000 with 150 bp paired-end reads. Sequencing data underwent quality control using FastQC and Trimmomatic17,18, and detailed quality metrics were provided in (Supplemental Table 2). After quality control and adapter trimming, cleaned data were deposited in the NCBI, the data has not been released. (Accession number: PRJNA1115821)19. Positive controls included conventional cancer drugs, while DMSO treated samples served as negative controls.

RNA-seq data were analyzed using the “New Tuxedo” pipeline HISAT20 for alignment, String Tie21 for transcript assembly/quantification, and DESeq2 for differential expression analysis, with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) defined as p ≤ 0.05 and |log2FC|≥ 122. A comparative analysis was conducted involving 187 medicinal plant groups alongside positive and negative controls to identify genes associated with antitumor activity. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) and DEGs was performed using the GOseq R package, based on the Wallenius noncentral hypergeometric distribution (http://geneontology.org/)23. Pathway analysis of DEPs and DEGs was conducted using the KEGG database (http://www.kegg.jp/)24, with statistical enrichment of DEGs in KEGG pathways assessed via KOBAS software25. Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analyses (cluster Profiler) highlighted inflammation and metastasis pathways, with expression visualized via TBtools heatmaps.

Machine learning-based screening of medicinal plants

This study utilized 178 transcriptomic profiles derived from differential gene expression analysis—each containing gene-level statistics such as logFC, P-value, and adj.P. Val—along with a consolidated gene expression matrix as input. An Autoencoder (AE) model was trained to comprehensively evaluate the mechanistic similarity between each medicinal plant extract and sorafenib12. The autoencoder was constructed with a symmetrical encoder–decoder architecture. The encoder network nonlinearly transformed high-dimensional input logFC feature vectors into a low-dimensional latent space representation. The decoder network then attempted to reconstruct the original input from this latent representation. The model was trained by minimizing the mean squared error between the input and reconstructed output.

Subsequently, multiple kernel learning (MKL) was applied to integrate a linear kernel based on the original features and a radial basis function (RBF) kernel derived from the latent features, thereby identifying an optimal linear combination13. The similarity between each plant extract and sorafenib was quantified as the corresponding element in the fused kernel matrix. Results from both analytical approaches are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

The WGCNA package in R was used to construct a weighted co-expression network, identifying 18 modules with a soft threshold of b = 11 (scale-free R2 = 0.8) and merging similar modules at MEDiss Thres = 0.25. Functional enrichment analysis of these modules revealed key cancer-associated pathways, with hub genes visualized in Cytoscape (v3.8.1)26,27 using weight thresholds of > 0.035 (Orange module) and > 0.24 (blue module). These hub genes may represent potential therapeutic targets for cancer. Supplemental Table 3 lists analysis steps, software and main scripts in our pipeline.

Proteomic analysis

Proteomic analysis was conducted on fractions treated with 2% sodium deoxycholate (SDC) and 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.5), followed by sonication and centrifugation at 12,000 × _g for 5 min. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Subsequently, proteins were reduced with tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) and alkylated with chloroacetamide (CAA) at 37 °C for 1 h. After dilution to < 0.5% SDC, proteins were digested with trypsin at a 1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio at 37_°C overnight.

Peptide samples were analyzed using an Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer coupled with a Vanquish NEO LC–MS system. Separation was performed on a C18 analytical column (150 μm × 150 mm) with a 14-min gradient of mobile phases A (0.1% formic acid) and B (0.1% formic acid, 80% acetonitrile) at 1.8 μL/min. Data were acquired in data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode.

Mass spectrometry data were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer software with UniProt’s Human Proteome Reference Database. Key parameters included variable modifications (methionine oxidation, N-terminal acetylation), fixed modification (cysteine carbamidomethylating), and trypsin/P digestion. Proteins with |log2FC|≥ 1.5 and p ≤ 0.05 were identified as significantly differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7, with three technical replicates per sample. Mean comparisons were made using least significant differences (LSDs), with statistical significance thresholds set at **** p < 0.0001, *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, and * p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Transcriptomics combined with deep learning to screen potential anti-cancer CHMs

In this study, we sequenced 606 cDNA libraries, resulting in approximately 9.69 Tb of raw data, which included 6,456,873,861 reads with an average read length of 100 bp (Supplemental Table 2). The total sequencing reads (9.69 Tb and 64,568,738,618 reads) have been submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive. The fraction with the largest number of DEGs was Pinus massoniana Lamb., which comprised 1,379 DEGs, of which 696 were upregulated and 683 were downregulated (Supplemental Fig. 2A). The highest agreement between the number of DEGs and positive controls was Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton , which comprised 336 upregulated DEGs and 5 downregulated DEGs. (Supplemental Table 4). The top 20 CHMs screened by the two methods were obtained according to the deep learning AE and MKL (Supplemental Fig. 5).The results from above conditions, along with the MTT results, were utilized to comprehensively screen five candidate CHMs (Fig. 1A,D). Detailed information of the five CHMs are provided in (Table 2). All these species contain anti-inflammatory compounds that have demonstrated anticancer effects in previous studies.

GO & KEGG pathway analysis implicated DEGs for tumor progression and metastasis

Throughout the course of its development, the recruitment of resident or circulating immune cells primarily controls the tumor microenvironment, which is crucial to its process28,29. We separated the gene sets in the positive control alignment analysis results into up-regulated and down-regulated gene sets for KEGG analysis to determine the biological pathways, networks, and functional categories of the DEGs. In each treatment group, the genes whose expression was markedly upregulated were primarily involved in proinflammatory pathways, carcinogenic transformation, tumor necrosis, and apoptosis. Previous research has demonstrated the importance of biological processes with proinflammatory effects in the development of tumors and cancer30,31,32; one such biological process in cancer metastasis is transcriptional regulation.33. Additionally, key pathways, such as the TNF signaling pathway, the IL-17 signaling pathway, cytokine-receptor interactions, the transcriptional signaling pathway, dysregulation in cancer, and the MAPK signaling pathway, have been identified as being involved in proinflammatory and metastatic processes (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, they are somewhat related. TNF-α has been shown to trigger apoptosis in specific pathological circumstances, and the exochemical function of major TNFs is accomplished by activating MAPK prosurvival kinase activity and NF-kappa B34,35. The expression of TNFα, IL-6, and other inflammatory cytokine genes can be increased by activating NF-kappa B.36. In addition to the activation signal of the innate IL-17 family of proinflammatory factor NF-kappa B, the NF-kappa B and MAPK pathways are the primary activators of the IL-17 signaling pathway. Many studies have demonstrated that IL-17A can activate a range of MAPKs and that the MAPK pathway is crucial for controlling mR and the stability of NA transcripts, which in turn regulates the expression of IL-17A-induced genes37. Similarly, transcriptional dysregulation also works with other pathways, and the immune response transcription regulator NF-kappa B is dysregulated with respect to genes and transcription factors that are chronically active in the inflammatory process of cancer38.

Among the set of down-regulated genes, CHM were identified to be involved primarily in the cAMP signaling pathway, steroid biosynthesis, the TGF-β signaling pathway, the p53 signaling pathway, and the cGMP-PKG signaling pathway (Fig. 1C). Notably, the cAMP signaling pathway serves as a pleiotropic second messenger within the tumor microenvironment (TME). Downstream effectors of cAMP include cAMP-dependent protein kinases (PKAs), exchange proteins activated by cAMP (EPACs), and various ion channels. While cAMP can activate PKA or EPAC to promote cancer cell growth, it may also inhibit cell proliferation and survival, depending on the specific environment and cancer type. Tumor-associated stromal cells, such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and immune cells, can release cytokines and growth factors that modulate cAMP production within the TME. Recent studies indicate that targeting cAMP signaling within the TME represents a promising avenue for cancer therapy39. Small molecule drugs that inhibit adenylyl cyclase and PKA have been demonstrated to suppress tumor growth. The role of steroid biosynthesis in liver cancer involves the metabolism of cholesterol and bile acids, which significantly influence cell proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, and the immune response. Cholesterol is recognized as a key lipotoxic molecule in the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) to liver cancer, as it facilitates the proliferation of liver cancer cells via the mTOR signaling pathway. The TGF-β signaling pathway plays a complex role in liver cancer development, functioning both as a tumor suppressor and as a promoter of tumor metastasis and invasion40. In HCC, the TGF-β signaling pathway may promote HCC progression by influencing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, the p53 signaling pathway is crucial for regulating the cell cycle, promoting apoptosis, and maintaining genomic stability41. In the context of liver cancer, activation of the p53 signaling pathway can induce apoptosis in cancer cells and inhibit their proliferation.

The five CHMs were enriched primarily in the extracellular space and extracellular region in the cellular component category, and they were strongly correlated with the extracellular vesicle and extracellular exosome categories according to the GO enrichment analysis (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Fig. 2B). The activity of signaling receptor regulators is strongly correlated with functional processes. Among these biological processes, Kaempferia galanga Linn. is also linked to cell migration. The biological process pathway is associated primarily with the regulation of apoptosis, programmed cell death, and small molecule metabolism. The strong correlations between the regulation of angiogenesis, epithelial development, and cell motility imply that Kaempferia galanga Linn. may be crucial in regulating the process by which cancer cells spread.

Gene expression and regulation of enrichment in five medicinal plants

Among the core pathways of the five CHMs, IL6, LIF, ATF4, JAG1, JUN, and CXCL2/3 were significantly upregulated in the three-candidate CHMs associated with the TNF signaling pathway. In the IL-17 signaling pathways, IL6, FOSL1, LCN2, and JUN were commonly significantly upregulated across the four CHMs candidates. Among the five CHM candidates involved in the apoptosis signaling pathway, ATF4, GADD45A, DDIT3, and BBC3 were upregulated. Additionally, ERN1 was significantly upregulated in Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton., Pinus massoniana Lamb., and Commelina communis Linn., whereas the TNFRSF10B gene was upregulated exclusively in Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton. The genes encoding IL32, CXCL2/3, LIF, GDF15, NHBE, and BMP6 were upregulated in pathways related to cytokine and receptor interactions. Notably, the IL15RA gene was uniquely upregulated among the top 10 contributors. Furthermore, RELB, FGF21, GADD45A/B, AREG, and DUSP4/5 were upregulated across the five CHMs. (Supplemental Fig. 2C) summarizes the key genes associated with the five candidate CHMs and their linkages to core pathways, while (Supplemental Fig. 9) illustrates the expression of key genes in the different treatment groups. The expression trends of most genes in the fraction treatment group were consistent with those in the positive control group, suggesting that the distillation group and anticancer drugs share common targets. Notably, some common genes have been implicated in the inflammatory processes or metastasis of cancer, particularly in liver cancer development. All the common genes analyzed exhibited differential expression across various CHMs treatments, with IL6, LIF, ROSL1, and DUSP4/5 showing significant upregulation (Supplemental Fig. 9). The enrichment analysis of the down-regulated genes revealed that the genes downregulated by traditional Chinese medicine, and the positive control drug were associated with several pathways, including the aldosterone-regulating sodium reabsorption pathway, cAMP signaling pathway, TGF-β signaling pathway, and folic acid biosynthesis pathway. Notably, genes such as AKR1B1042 have been shown to inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of HCC by modulating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Additionally, the RDH10 gene is considered a potential target for glioma treatment; its downregulation can impede tumor development by influencing various signaling pathways and cellular processes, such as inhibiting cell proliferation, regulating apoptosis, and affecting cell migration and invasion43. The HMGCR gene44, a key rate-limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, is closely associated with tumor occurrence and progression, with studies indicating that HMGCR knockdown inhibits the growth, migration, and clonal formation of ESCC cells. Furthermore, downregulation of ATP1B1 has been shown to inhibit the proliferation, migration, invasion, and adhesion of DLBCL cells45. The downregulation of the MVK gene may influence cancer progression through multiple mechanisms, including reducing tumor risk, affecting cyclin expression, regulating cholesterol metabolism pathways, and modifying the tumor microenvironment46. The significant downregulation of these genes suggests that the Chinese herbal fraction can inhibit tumor cell proliferation and migration by regulating gene expression across various signaling pathways, thus providing a new foundation for future research on the identification and isolation of effective compounds.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis identifies key modules associated with traditional Chinese medicine efficacy

To investigate the relationship between the efficacy of Chinese medicine ingredients and module characteristic genes (MEs), a weighted co-expression network was constructed, and co-expression modules were identified via the “WGCNA” package in R. The sample dendrogram and feature heatmap are presented in (Supplemental Fig. 3C). In this study, a power of b = 8 was selected to achieve high scale independence and low average connectivity (Supplemental Fig. 3A). The dissimilarity threshold between modules was set at 0.2, resulting in the generation of 23 distinct modules (Fig. 2A). The module relationship diagram revealed that Pinus., Commelina., Kaempferia. and Amomum. were strongly correlated with the blue module and that Mahonia. was significantly correlated with the orange module (Supplemental Fig. 3B). These findings suggest that these modules are effective for identifying hub genes related to cancer staging. Furthermore, the independence of each module indicates both high scale independence and differential gene expression among the modules.

KEGG Analysis of Key Modules and Cytological validation. (A) showed the relationship between each module and the processing group; the leftmost color block represents the module, and the rightmost color bar represents the correlation range. In the middle part of the heatmap, the darker the color is, the greater the correlation. The numbers in each cell indicate relevance and significance. (B) the KEGG bubble diagram of the key genes in the blue module, and e shows the KEGG bubble diagram of the key genes in the orange module, where the abscissa is the Rich factor, the ordinate is the enrichment pathway, the darker the red, the more significant, and the bubble size is the number of genes in the pathway. (C–D) the network diagram of the core genes in the key module, where the dots represent the genes in the module (degree ≥ 20, weight ≥ 0.1), where the circles are the core genes (red is upregulated, and green is downregulated), and the pink square nodes are the pathways to which the core genes converge. (E) the trend of cell viability under the gradient concentration of each experimental group(D345-B: Pinus massoniana Lamb., D550-A: Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde, GX0899-C: Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton. GX1084-C: Kaempferia galanga Linn., D303-A: Commelina communis Linn.). F-G: Bar graph of cell apoptosis at different concentrations, with the horizontal axis representing each treatment group and the vertical axis representing the apoptosis rate. H: the experimental diagram of cell migration after 24 h of drug treatment, where the abscissa of the histogram represents each treatment group and the ordinate denotes the migration distance (μm).

Identification of hub genes in selected modules

Typically, genes included in co-expression modules and exhibiting high connectivity are selected as hub genes. In this study, we identified 48 central genes (blue module: 16, orange module: 20), as shown in (Fig. 2C–D) and (Supplemental Table 5). These genes were screened from the blue module under the conditions of degree ≥ 20 and weight ≥ 0.1. After the data were imported into Cytoscape (v3.8.1), a total of 72 nodes were identified. Among these nodes, two upregulated genes are indicated by red triangles, whereas 14 downregulated genes are marked by green circles in (Fig. 2C). The analysis focused primarily on the AMPK pathway and the amino acid synthesis pathway. The orange module identified 81 nodes (Fig. 2D), of which three core genes were significantly upregulated and 17 genes were downregulated, with primary enrichment in the RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, the PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathways in cancer, and the chemokine signaling pathway.

KEGG enrichment of modules

The genes in the two core modules were screened based on the criterion of module membership (MM) > 0.8 to obtain the core gene set (Supplemental Fig. 3B). The genes within each module were extracted, and a KEGG pathway was constructed. As illustrated in (Fig. 2C–D), the genes in the blue module were enriched predominantly in pathways such as the TNF signaling pathway, necroptosis pathway, p53 signaling pathway, apoptosis pathway, and ferroptosis pathway, all of which play significant roles in cancer development. Notably, p53 is a tumor suppressor that is crucial for inducing ferroptosis and influencing the onset and progression of liver cancer. P53 enhances the sensitivity of liver cancer cells to ferroptosis inducers by transcriptionally inhibiting the expression of the ferroptosis-related protein SLC7A1147 (Fig. 2B). The genes in the orange module are involved primarily in the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, the RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, necroptosis, and the TNF signaling pathway, all of which are vital for cancer development (Fig. 2B).

MTT, apoptosis, and migration verification

To further verify the stability of the inhibitory effect of Chinese herbal fractions on the growth of cancer cells, we conducted an MTT gradient experiment. The results demonstrated that the inhibitory effect of the distillation mixture on liver cancer cells progressively increased with increasing dose, with Pinus massoniana Lamb. and Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton. exhibit the m ost pronounced effects (Fig. 2E). Additionally, apoptosis assays confirmed the apoptotic effects of the CHMs fractions on cancer cells. (Fig. 2F–G) show the rates of apoptosis in each treatment group at the transcriptome concentration (Survival ≥ 80%) and IC50concentration. The fraction treatment groups exhibited varying degrees of apoptosis promotion, with trends consistent with those observed in the positive control group treated with sorafenib. Notably, the low-concentration groups of Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton. and Kaempferia galanga Linn. demonstrated the greatest promotion of apoptosis, with an apoptosis rate of 46% (Fig. 2F; Supplemental Fig. 3D). The apoptosis rates of Pinus massoniana Lamb., Commelina communis Linn., and Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde., Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton. exceeded 50%, whereas the percentage of Commelina communis Linn. apoptotic cells reached 62.33%. The cell migration results are presented in (Fig. 2H; Supplemental Fig. 3E), which shows the state of cell migration from 0 to 24 h. Each fraction treatment clearly significantly inhibited cell migration, as indicated by the scratch width at 24 h being greater than or equal to that at 0 h. The histogram further corroborates that the trends in the fraction treatment groups align with those of the positive control group, with Commelina communis Linn., Pinus massoniana Lamb., and Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) demonstrating superior inhibition of cell migration compared with the positive control. These cell experiments confirmed that the five distillation groups strongly promoted apoptosis and significantly inhibited cell migration in hepatoma cells.

Proteomics statistical analysis

Peptide Length Distribution: The mass spectrometry (MS1) scanning range typically spans 350–1500 m/z. Upon ionization, most peptides exhibit charge states of + 2, with some displaying + 3, + 4, and so forth, decreasing in sequence. The average molecular weight of amino acid residues in proteins is approximately 110 Da, which results in most detected peptides falling within the range of 7–27 amino acids (Supplemental Fig. 4A). Peptide number distribution: The relative abundance of a protein is typically greater in large-scale proteomic data with more protein data, and there is some positive correlation between the two. The reliability of the proteomics results at the protein level increases with the percentage of protein in the polypeptide. (Supplemental Fig. 4B). Distribution of Missed Cleavage Sites: To perform protein sample mass spectrometry before detection, trypsin is used to hydrolyze the protein enzymatically. For mass spectrometry, trypsin breaks down intact proteolysis into peptides of varying lengths by specifically hydrolyzing the arginine and lysine C-telopeptide bonds in proteins. A tiny percentage of peptides have one or two missed sites, whereas many detected peptides typically have no missed sites. (Supplemental Fig. 4C). In this investigation, (Supplemental Fig. 4D) displays the quantity of proteins and peptides in each sample. To assess the quantitative repeatability between replicate samples and the quantitative correlation between various sample groups, the Pearson correlation coefficient (R) between samples can be computed based on the quantitative data of each protein. In this project, (Supplemental Fig. 4, E) displays the quantitative correlation coefficient between pairs of all samples. Principal component analysis (PCA) is one of the most popular techniques for dimensionality reduction analysis. Proteins’ quantitative information is utilized as a variable for orthogonal transformation, and the quantitative information of many proteins is transformed into group variables to create PCA principal component analysis diagrams. These diagrams intuitively illustrate how the spatial distribution of data varies between samples. Various samples in the same group were clustered within a relatively concentrated range in this study (Fig. 3B), making them distinct from other data cluster groups.

Proteomic validation and KEGG bubble chart of quadrants 3 (a) and 7 (b). A: a statistical table of differentially expressed genes and proteins in each treatment group, with the horizontal axis representing each treatment group and the vertical axis representing the number of differentially expressed genes and proteins. Red represents upregulated proteins, and blue represents downregulated proteins. (B) three-dimensional PCA principal component analysis diagram between samples: the differences between different samples can be intuitively displayed through the differences in data spatial distribution. The smaller the spatial distribution difference, the closer the data. Each point in the PCA distribution diagram represents an experimental sample, and different groups are distinguished by different colors. (C) volcano plot of the differential protein distribution in each treatment group, with the horizontal axis representing each treatment group and the vertical axis representing the A-weighted log2FC value. Dark orange represents upregulated proteins, and blue represents downregulated proteins. The marked proteins correspond to the key genes. (D) KEGG bubble plot of the differentially expressed proteins. The abscissa represents the treatment group, the ordinate represents the enriched pathway, the darker the bubble color is, the greater the significance, and the bubble size represents the number of proteins enriched in the pathway. (E–F) KEGG enrichment analysis of the two quadrants of each treatment group that were significantly associated in the transcriptome‒proteome association analysis. The horizontal axis represents the treatment group, and the vertical axis represents the enriched pathway. The darker the bubble color is, the greater the significance. The greater the number of genes and proteins in the pathway.

Protein difference analysis and KEGG enrichment analysis

By conducting a database search on the raw mass spectrometry data, the detection signal intensity for each peptide can be obtained, allowing for the calculation of quantitative information corresponding to each protein. Following normalization of the results, quantitative comparisons of the same protein across different samples can be performed. Based on sample grouping, effective data screening and the filling of missing data enable the calculation of the protein quantitative ratio distribution within the samples of each comparison group. The statistics of the differential proteins in each fraction group are presented in (Fig. 3A). A comparative analysis between the fraction group and the blank control revealed a total of 8095 differentially expressed proteins, comprising 4264 upregulated proteins and 3,831 downregulated proteins. (Fig. 3C) displays the total differential proteins as well as the associated core differential proteins between each experimental group and the positive control group. KEGG analysis of these differentially expressed proteins revealed numerous pathways associated with cancer development, including necroptosis, the IL-17 signaling pathway, the TNF signaling pathway, the MAPK signaling pathway, and the p53 signaling pathway, among others. (Fig. 3D) indicates that the pathways most significantly enriched in the experimental group are the MAPK signaling pathway, the TNF signaling pathway, and apoptosis; the pathways significantly enriched among the top ten contributors include the p53 signaling pathway and the cell cycle.

Joint transcriptome‒proteome analysis

To further validate the screening of fractions, we present a comprehensive overview that spans from genes to proteins, integrating various data sources to increase the reliability and interpretability of our results. A nine-quadrant joint analysis of the transcriptome and proteome was conducted for each treatment group (Supplemental Fig. 4F). The differential gene and protein expression patterns observed in quadrants 1 and 9 are inconsistent, suggesting the potential for deeper exploration at the posttranscriptional or translational level. Quadrants 2 and 8 illustrate the differential expression of genes without corresponding changes in proteins, indicating the possibility of posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms. In contrast, quadrants 4 and 6 show differential expression of proteins without changes in the corresponding genes, warranting consideration of translation-level regulation or protein accumulation. All genes and proteins in the remaining five quadrants were not differentially expressed. Quadrants 3 and 7 revealed consistent trends in the changes in both genes and their corresponding proteins, indicating synchronous alterations at the transcriptional and translational levels. This aspect is a significant focus of our study.

Further KEGG analysis was performed on the genes and corresponding proteins in quadrants 3 and 7. In particular, the genes and corresponding proteins in these quadrants were all upregulated, with the main enriched pathways closely linked to cancer progression, including the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, cellular senescence, insulin resistance, the TNF signaling pathway, the IL-17 signaling pathway, necroptosis, and the VEGF signaling pathway (Fig. 3E). The ten genes and proteins upregulated by Commelina communis Linn. significantly converge in the ferroptosis pathway, leading to increased cell death, which in turn inhibits tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. For example, they regulate GPX4 through Krüppel-like factor 2 to prevent cancer cell migration and invasion48. KEGG analysis (Fig. 3F) of the significantly downregulated genes and corresponding proteins across the seven quadrants revealed substantial enrichment in pathways such as retinol metabolism, the cell cycle, AMPK signaling, metabolic pathways, and Rap1 signaling. Notably, Kaempferia galanga Linn. and Commelina communis Linn. significantly enriched in the focal adhesion pathway, which may inhibit the proliferation, migration, and invasion of tumor cells, thereby slowing tumor growth and metastasis49. Additionally, downregulation of the cGMP‒PKG signaling pathway in Commelina communis Linn. promoted cell apoptosis and inhibited cell growth. Furthermore, the downregulation of metabolic pathways, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, and the AMPK signaling pathway may hinder the metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells, consequently slowing tumor growth and progression. This may also involve the inhibition of tumor cell growth through the disruption of metabolites and signaling pathways, thereby retarding tumor progression and metastasis50,51. These pathways are also significantly enriched in Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton., Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde, and Pinus massoniana Lamb.

Discussion

CHM has a long history in treating and preventing malignant tumors, not only by directly inhibiting tumor growth but also by reducing the toxic side effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, improving patients’ quality of life, and enhancing survival rates52. With its unique dialectical and holistic approach, CHM offers a distinct perspective on disease management compared to Western medicine. However, the complexity and diversity of CHM formulations make determining their chemical composition highly challenging. Chemical composition analysis of medicinal plants is essential for elucidating the pharmacological effects and therapeutic mechanisms of CHM, providing a scientific basis for its clinical application. Key chemical constituents include Volatile oils, Alkaloids, Flavonoids, Polysaccharides, Tannins, and Saponins53,54,55, which exhibit diverse biological activities such as antibacterial, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects. For instance, Flavonoids have been shown to induce apoptosis and inhibit tumor cell proliferation56, while certain alkaloids disrupt tumor cell signaling pathways, suppressing tumor growth and metastasis57. Despite these advances, the chemical characterization of CHM remains a complex and time-intensive process, requiring the integration of multiple analytical techniques to identify active components and their mechanisms of action.

Chinese herbal medicines screened

Pinus massoniana Lamb. needles are rich in bioactive compounds such as Volatile oils, Flavonoids, Polysaccharides, and Lignans, which exhibit significant anticancer potential. Lignans demonstrate antitumor, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, while also enhancing cardiovascular health58,59. Extracts obtained using petroleum ether and ethyl acetate show the most potent antitumor activity. Shikimic acid, another key compound, exhibits diverse pharmacological effects, including antitumor, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties60. Proanthocyanidins, the primary active component in pine bark extract (PMBE), inhibit cancer cell growth in vitro by upregulating p53 and p21 to arrest the cell cycle and downregulating Bcl2 to induce apoptosis61. Additionally, Masson pine bark extract induces apoptosis and inhibits cancer cell migration, demonstrating antitumor activity against HepG2, HeLa, and S180 cells60,62,63.

Kaempferia galanga Linn. gained attention for their anticancer mechanisms, attributed to their rich chemical composition. Kaempferol, a flavonoid in Kaempferia galanga, inhibits the progression of liver, colon, lung, and ovarian cancers by inducing apoptosis, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), and disrupting cell cycle and autophagy pathways. It targets key signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt, EGFR, MAPK, and Wnt, with PI3K/Akt regulation being particularly significant64,65,66. Similarly, gingerol, an active component of ginger, exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-regulatory properties, while inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis67,68. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of natural compounds in cancer treatment.

Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton. is rich in Volatile oils, which exhibit anticancer properties by inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis, potentially through cell cycle modulation69. Dry extracts of Amomum subulate seeds have been shown to target TP53, demonstrating strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities in cancer cells70. Beyond volatile oils, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and ethyl EMC are key anticancer constituents in cardamom plants. Flavonoids may suppress tumor invasion and metastasis by modulating growth factor signaling pathways, proteases, and E-cadherin, while phenolic acids influence oxidative stress and NF-κB signaling pathway71,72.

Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde., a major bioactive compound from Berberidaceae. plants, exhibits potent antitumor effects through mechanisms including cell proliferation inhibition, apoptosis induction, cell cycle disruption, and autophagy activation73. It also possesses anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties, mediated by regulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, and MAPK/ERK pathways64,74,75. Additionally, benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) such as spattering and aquathlons, isolated from Mahonia species, show lipoxygenase inhibition and potential anticancer activity76,77.The genus Commelina communis Linn. (Commelinaceae), comprising over 200 species, has been traditionally used to treat various diseases. Despite limited research, these species contain diverse bioactive phytochemicals, including Alkaloids, Phenols, Flavonoids, and Tannins, which are believed to contribute to their pharmacological activities78,79. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of plant-derived compounds in cancer treatment.

Anticancer pathways of Chinese herbal medicines

CHMs play a pivotal role in anticancer therapy by modulating cancer cell behavior and altering key signaling pathways. They offer significant advantages in mitigating the adverse effects of conventional cancer treatments while enhancing therapeutic efficacy. Compared to traditional chemotherapy, CHMs are characterized by high efficiency, low cost, and minimal side effects, making them a vital component of cancer treatment strategies. Research has identified multiple anticancer active ingredients in CHMs, including terpenoids, flavonoids, and alkaloids, which interact with critical signaling pathways in liver cancer, such as epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT), TGF-β, IL-7, NF-κB, MAPK, p53, and TNF pathways. These pathways are instrumental in regulating the initiation and progression of liver cancer. In addition to their direct anticancer effects, CHMs exhibit immune-modulatory, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and blood circulation-promoting properties, which help alleviate the adverse reactions associated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, ultimately improving patients’ quality of life. Despite these benefits, the active components and molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects of CHMs remain poorly understood. Further research is needed to elucidate their efficacy and identify their active ingredients. High-throughput in vitro gene expression profiling screening of CHMs can provide insights into their effects on cancer cells and associated signaling pathway alterations, advancing our understanding of their anticancer mechanisms. In summary, CHMs exert significant anticancer effects by modulating multiple signaling pathways and exhibiting diverse pharmacological activities. Continued investigation into their active components and molecular mechanisms is essential for the development of novel anticancer drugs and innovative therapeutic strategies for liver cancer.

Identification of core hub genes and proteins from integrated omics analysis

In this study, we employed transcriptomic and proteomic analyses to identify specific hub genes regulated by five CHM candidates in liver cancer, revealing novel targets beyond broadly established pathways. These candidates significantly modulated genes involved in key pathways, including AMPK, ErbB, TNF, apoptosis, p53, cGMP-PKG, and cytokine‒cytokine receptor interactions. Key genes affected included CTH, AKR1B10, AOX1, AREG, ATP1B1, CA9, FOSL1, GDF15, HMGCR, JUN, LCN2, MVK, RDH10, and THBS1. Among these, AKR1B10, AOX1, ATP1B1, CA9, HMGCR, MVK, RDH10, and THBS1 were downregulated, while the remaining six genes were upregulated.

Our analysis identified AKR1B10 as a key hub gene downregulated by Pinus massoniana Lamb. and Commelina communis Linn. This gene, encoding an aldehyde-ketone reductase, is uniquely regulated in our study and plays a critical role in detoxification and carcinogenesis. Specifically, it modulates the retinoic acid signaling pathway by converting retinal to retinol, and its downregulation may disrupt retinoic acid availability, thereby influencing liver cancer cell behavior5,80. Proteomic validation confirmed the consistent downregulation of the corresponding protein O60218, underscoring its potential as a novel therapeutic target.

HMGCR emerged as another hub gene, downregulated by Kaempferia galanga Linn. While HMGCR is known for its role in the mevalonate pathway, our findings highlight its specific regulation in liver cancer by CHMs. The downregulation of HMGCR may suppress cancer progression by inhibiting cholesterol and isoprenoid synthesis, essential for malignant cells32,81. Importantly, we link this to AMPK-mediated effects, but our data suggest a unique regulatory mechanism involving the HMGCR-p38 MAPK-GSK3B axis, which enhances antitumor immunity82. The proteomic data for protein P04035 corroborate this regulation.

THBS1 was identified as a central hub gene downregulated by Kaempferia galanga Linn. and Commelina communis Linn. Beyond its known role in p53 signaling, our analysis reveals its unique involvement in TGF-β interactions in the context of CHM treatment. Silencing THBS1 inhibits liver cancer cell proliferation and invasion83,84. and our data suggest that its downregulation by CHMs may mitigate liver fibrosis and cancer progression by specifically blocking TGF-β signaling84. The corresponding protein P07996 shows consistent downregulation, validating THBS1 as a novel target. These findings underscore the ability of CHMs to target specific hub genes such as AKR1B10, HMGCR, and THBS1, which are critically involved in liver cancer progression. By focusing on these novel targets, our study provides original insights into the mechanistic actions of CHMs beyond conventional pathways.

Our integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analysis identified five traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs)—Amomum compactum Solander ex Maton., Pinus massoniana Lamb., Commelina communis Linn., Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde, and Kaempferia galanga Linn. —with potential anti-hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) activity. Moving beyond generalized pathway descriptions, we focused on specific hub genes validated by this multi-omics approach. Potential medicinal plants were screened using deep learning and positive drug comparisons, while functional analysis and weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) pinpointed 40 core genes for further validation. Critically, proteomic data confirmed consistent expression trends for 14 corresponding gene-protein pairs. Notably, the significant downregulation of key hub genes, including AKR1B10, HMGCR, and THBS1, was strongly associated with the suppression of HCC cell proliferation and the induction of apoptosis. Thus, our study leverages a robust data-driven framework to directly link the cooperative regulation of these specific hub genes to the anti-HCC effects of the identified TCMs, providing novel, mechanistic insights into their mode of action.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed an integrated drug discovery platform synergizing big data-driven computational modeling with high-throughput functional genomics to systematically identify anti-cancer CHMs and delineate their molecular targets. By leveraging machine learning algorithms trained on multi-omics datasets and coupling them with high-content screening, this framework accelerates the discovery of novel therapeutic candidates. Crucially, our work bridges the gap between CHM’s empirical knowledge and modern precision medicine by enabling data-driven rationalization of herbal medicine’s pharmacological potential, thereby transforming traditional resources into digitized, analyzable assets. The identified CHMs and their associated targets offer mechanistic insights into CHM’s anti-tumor activity while providing a blueprint for repurposing natural products in oncology. This paradigm exemplifies how interdisciplinary approaches can unlock the untapped value of traditional medicine in the era of artificial intelligence and systems biology, ultimately advancing both cancer research and global drug discovery pipelines.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations in this study are provided in Table 3.

Data availability

Transcriptomic data has been uploaded to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive team for facilitating the deposition of transcriptomic data (Accession number: PRJNA1115821). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the iProX partner repository (https://www.iprox.cn/page/SSV024.html;url=1749719046099GmMC,password: cxyp)

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Hecht, J. R. et al. Phase Ib study of talimogene laherparepvec in combination with atezolizumab in patients with triple negative breast cancer and colorectal cancer with liver metastases. ESMO Open 8, 100884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100884 (2023).

Wolf, C. P. J. G. et al. Interactions in cancer treatment considering cancer therapy, concomitant medications, food, herbal medicine and other supplements. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 148, 461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03625-3 (2021).

Sflakidou, E., Leonidis, G., Foroglou, E., Siokatas, C. & Sarli, V. Recent advances in natural product-based hybrids as anti-cancer agents. Molecules 27, 6632. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27196632 (2022).

Ma, L.-N. et al. AKR1B10 expression characteristics in hepatocellular carcinoma and its correlation with clinicopathological features and immune microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 14, 12149. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62323-5 (2024).

Bakshi, H. A. et al. Crocin inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis in colon cancer via TNF-α/NF-kB/VEGF pathways. Cells 11, 1502. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11091502 (2022).

Singh, D., Mittal, N., Verma, S., Singh, A. & Siddiqui, M. H. Applications of some advanced sequencing, analytical, and computational approaches in medicinal plant research: A review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 51, 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-09057-1 (2023).

Tyagi, P., Singh, D., Mathur, S., Singh, A. & Ranjan, R. Upcoming progress of transcriptomics studies on plants: An overview. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1030890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1030890 (2022).

Gutiérrez-González, A., Del Hierro, I. & Cariaga-Martínez, A. E. Advancements in multiple myeloma research: High-throughput sequencing technologies omics, and the role of artificial intelligence. Biology 13, 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13110923 (2024).

Kui, L. et al. High-throughput in vitro gene expression profile to screen of natural herbals for breast cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 11, 684351. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.684351 (2021).

Lee, S., Weiss T., Bühler M., Mena J., Lottenbach Z., Wegmann R., Sun M., Bihl M., Augustynek B., Baumann ,S.P., Goetze S., van Drogen A., Pedrioli P.G.A., Penton D., Festl Y., Buck A., Kirschenbaum D., Zeitlberger A.M., Neidert M.C., Vasella F., Rushing E.J., Wollscheid B., Hediger M.A., Weller M., Snijder B., High-throughput identification of repurposable neuroactive drugs with potent anti-glioblastoma activity, Nat. Med. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03224-y (2024).

Dong, K. & Zhang, S. Deciphering spatial domains from spatially resolved transcriptomics with an adaptive graph attention auto-encoder. Nat. Commun. 13, 1739. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29439-6 (2022).

Rahimi, A. & Gönen, M. Discriminating early- and late-stage cancers using multiple kernel learning on gene sets. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 34, i412–i421. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty239 (2018).

Grela, E., Kozłowska, J. & Grabowiecka, A. Current methodology of MTT assay in bacteria—A review. Acta Histochem. 120, 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acthis.2018.03.007 (2018).

Vermes, I., Haanen, C., Steffens-Nakken, H. & Reutelingsperger, C. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods 184, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(95)00072-i (1995).

Martinotti, S. & Ranzato, E. Scratch wound healing assay. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2109, 225–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/7651_2019_259 (2020).

Polito, L., Bortolotti, M., Battelli, M. G., Calafato, G. & Bolognesi, A. Ricin: An ancient story for a timeless plant toxin. Toxins 11, 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11060324 (2019).

Poluri, R. T. K., Beauparlant, C. J., Droit, A. & Audet-Walsh, É. RNA sequencing data of human prostate cancer cells treated with androgens. Data Brief 25, 104372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.104372 (2019).

Wingett, S. W. & Andrews, S. FastQ Screen: A tool for multi-genome mapping and quality control. F1000Research 7, 1338. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.15931.2 (2018).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

McDermaid, A., Monier, B., Zhao, J., Liu, B. & Ma, Q. Interpretation of differential gene expression results of RNA-seq data: review and integration. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 2044. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bby067 (2018).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 (2010).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr988 (2011).

Mao, X., Cai, T., Olyarchuk, J. G. & Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21, 3787–3793. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430 (2005).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Su, G., Morris, J. H., Demchak, B. & Bader, G. D. Biological network exploration with cytoscape 3. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma Ed. Board Andreas Baxevanis Al 47, 8131. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0813s47 (2014).

Lai, H. et al. Targeting cancer-related inflammation with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Perspectives in pharmacogenomics. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1078766. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1078766 (2022).

Song, X., Wei, C. & Li, X. The potential role and status of IL-17 family cytokines in breast cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 95, 107544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107544 (2021).

Meng, Y. et al. A TNFR2–hnRNPK axis promotes primary liver cancer development via activation of YAP Signaling in Hepatic progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 81, 3036–3050. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3175 (2021).

Shuai, C., Yang, X., Pan, H. & Han, W. Estrogen receptor downregulates expression of PD-1/PD-L1 and infiltration of CD8+ T cells by inhibiting IL-17 Signaling transduction in breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 582863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.582863 (2020).

Wang, N. et al. AMPK–a key factor in crosstalk between tumor cell energy metabolism and immune microenvironment. Cell Death Discov. 10, 237. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-02011-5 (2024).

Dong, J. et al. Transcriptional super-enhancers control cancer stemness and metastasis genes in squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 12, 3974. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24137-1 (2021).

Cruceriu, D., Baldasici, O., Balacescu, O. & Berindan-Neagoe, I. The dual role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in breast cancer: molecular insights and therapeutic approaches. Cell. Oncol. 43, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13402-019-00489-1 (2020).

Varfolomeev, E. & Vucic, D. Intracellular regulation of TNF activity in health and disease. Cytokine 101, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.035 (2018).

Rosenberg, N. et al. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma derives from liver progenitor cells and depends on senescence and IL-6 trans-signaling. J. Hepatol. 77, 1631–1641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.029 (2022).

Amatya, N., Garg, A. V. & Gaffen, S. L. IL-17 Signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends Immunol. 38, 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2017.01.006 (2017).

Casamassimi, A., Ciccodicola, A. & Rienzo, M. Transcriptional regulation and its Misregulation in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24108640 (2023).

Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 (2013).

Liu, K. et al. Stabilization of TGF-β Receptor 1 by a receptor-associated adaptor dictates feedback activation of the TGF-β Signaling pathway to maintain liver cancer stemness and drug resistance. Adv. Sci. 11, 2402327. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202402327 (2024).

Chen, J., Gingold, J. A. & Su, X. Immunomodulatory TGF-β Signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Trends Mol. Med. 25, 1010–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2019.06.007 (2019).

Tian, K., Deng, Y., Li, Z., Zhou, H. & Yao, H. AKR1B10 inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Oncol. Lett. 27, 18. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2023.14151 (2023).

Guan, F. et al. Retinol dehydrogenase 10 promotes metastasis of glioma cells via the transforming growth factor-β/SMAD signaling pathway. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 132, 2430–2437. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000478 (2019).

Marks, M. P. et al. Role of hydroxymethylglutharyl-coenzyme A reductase in the induction of stem-like states in breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 150, 106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-024-05607-7 (2024).

Zhang, S., Wang, H. & Liu, A. Identification of ATP1B1, a key copy number driver gene in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and potential target for drugs. Ann. Transl. Med. 10, 1136. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-22-4709 (2022).

Qiu, X. et al. Mendelian randomization reveals potential causal relationships between cellular senescence-related genes and multiple cancer risks. Commun. Biol. 7, 1069. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06755-9 (2024).

Su, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, L. & Gu, W. Regulation of SLC7A11 as an unconventional checkpoint in tumorigenesis through ferroptosis. Genes Dis. 12, 101254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2024.101254 (2024).

Zhou, Q. et al. Ferroptosis in cancer: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01769-5 (2024).

Gnani, D. et al. Focal adhesion kinase depletion reduces human hepatocellular carcinoma growth by repressing enhancer of zeste homolog 2. Cell Death Differ. 24, 889–902. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2017.34 (2017).

Hsu, C.-C., Peng, D., Cai, Z. & Lin, H.-K. AMPK signaling and its targeting in cancer progression and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 85, 52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.04.006 (2021).

Khan, F., Pandey, P., Verma, M. & Upadhyay, T. K. Terpenoid-mediated targeting of STAT3 Signaling in cancer: An overview of preclinical studies. Biomolecules 14, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14020200 (2024).

Zhao, Q. et al. An optimized herbal combination for the treatment of liver fibrosis: Hub genes, bioactive ingredients, and molecular mechanisms. J. Ethnopharmacol. 297, 115567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2022.115567 (2022).

Liu, X., Cui, S., Li, W., Xie, H. & Shi, L. Elucidation of the anti-colon cancer mechanism of Phellinus baumii polyphenol by an integrative approach of network pharmacology and experimental verification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 127429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127429 (2023).

Tian, W. et al. Harnessing natural product polysaccharides against lung cancer and revisit its novel mechanism. Pharmacol. Res. 199, 107034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2023.107034 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Advances in antitumor activity and mechanism of natural steroidal saponins: A review of advances, challenges, and future prospects. Phytomedicine 128, 155432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155432 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Discovery of vitexin as a novel VDR agonist that mitigates the transition from chronic intestinal inflammation to colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 23, 196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-02108-6 (2024).

Guo, W. et al. Aloperine suppresses cancer progression by interacting with VPS4A to inhibit Autophagosome-lysosome fusion in NSCLC. Adv. Sci. 11, 2308307. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202308307 (2024).

Nisca, A. et al. Comparative study regarding the chemical composition and biological activity of pine (Pinus nigra and P. sylvestris) Bark Extracts. Antioxidants 10, 327. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10020327 (2021).

Zulfqar, F. et al. Chemical characterization, antioxidant evaluation, and antidiabetic potential of Pinus gerardiana (Pine nuts) extracts. J. Food Biochem. 44, e13199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13199 (2020).

Ferguson, J. J. A., Oldmeadow, C., Bentley, D. & Garg, M. L. Antioxidant effects of a polyphenol-rich dietary supplement incorporating Pinus massoniana bark extract in healthy older adults: A two-arm parallel group, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Antioxidants 11, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081560 (2022).

Yi, J. et al. Optimization of purification, identification and evaluation of the in vitro antitumor activity of polyphenols from Pinus Koraiensis pinecones. Molecules 20, 10450–10467. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200610450 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Anti-Tumor effect of Pinus massoniana bark Proanthocyanidins on ovarian cancer through induction of cell apoptosis and inhibition of cell migration. PLoS ONE 10, e0142157. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142157 (2015).

Mao, P. et al. Pinus massoniana bark extract inhibits migration of the lung cancer A549 cell line. Oncol. Lett. 13, 1019–1023. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2016.5509 (2017).

Gao, X. et al. Berberine and Cisplatin exhibit synergistic anticancer effects on osteosarcoma MG-63 cells by inhibiting the MAPK pathway. Molecules 26, 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26061666 (2021).

Sengupta, B. et al. Anticancer properties of Kaempferol on cellular Signaling pathways. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 22, 2474–2482. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568026622666220907112822 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Kaempferol promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell autophagy via restricting Met pathway. Phytomedicine 121, 155090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155090 (2023).

Kang, D. Y. et al. Anticancer effects of 6-Gingerol through downregulating iron transport and PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cells 12, 2628. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12222628 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. 6-Gingerol protects intestinal barrier from ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage via inhibition of p38 MAPK to NF-κB signalling. Pharmacol. Res. 119, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2017.01.026 (2017).

Cai, R. et al. Chemistry and bioactivity of plants from the genus Amomum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 281, 114563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2021.114563 (2021).

Ali, S. et al. Amomum subulatum: A treasure trove of anti-cancer compounds targeting TP53 protein using in vitro and in silico techniques. Front. Chem. 11, 1174363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2023.1174363 (2023).

Bonta, R. K. Dietary phenolic acids and flavonoids as potential anti-cancer agents: Current state of the art and future perspectives. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 20, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871520619666191019112712 (2020).

Sudarsanan, D., Suresh Sulekha, D. & Chandrasekharan, G. Amomum subulatum induces apoptosis in Tumor cells and reduces Tumor Burden in experimental animals via modulating pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cancer Invest. 39, 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/07357907.2021.1878529 (2021).

Wong, B.-S. et al. The in vitro and in vivo apoptotic effects of Mahonia oiwakensis on human lung cancer cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 180, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2009.02.011 (2009).

Almatroodi, S. A., Alsahli, M. A. & Rahmani, A. H. Berberine: An important emphasis on its anticancer effects through modulation of various cell Signaling pathways. Molecules 27, 5889. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27185889 (2022).

Och, A., Podgórski, R. & Nowak, R. Biological activity of Berberine—A summary update. Toxins 12, 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12110713 (2020).

Chan, E. W. C., Wong, S. K. & Chan, H. T. An overview on the chemistry, pharmacology and anticancer properties of tetrandrine and fangchinoline (alkaloids) from Stephania tetrandra roots. J. Integr. Med. 19, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2021.01.001 (2021).

Petruczynik, A. et al. Determination of Selected Isoquinoline Alkaloids from Mahonia aquifolia; Meconopsis cambrica; Corydalis lutea; Dicentra spectabilis; Fumaria officinalis Macleaya cordata extracts by HPLC-DAD and comparison of their cytotoxic activity. Toxins 11, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11100575 (2019).

Dagne, A., Yihunie, W., Nibret, G. & Tegegne, B. A. The genus Commelina: Focus on distribution, morphology, traditional medicinal uses, phytochemistry, and Ethno-pharmacological activities: An updated literature review. Heliyon 10, e30945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30945 (2024).

Kudumela, R. G. & Masoko, P. In vitro assessment of selected medicinal plants used by the Bapedi community in South Africa for treatment of bacterial infections. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 23, 2515690X18762736. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690X18762736 (2018).

Büküm, N. et al. Inhibition of AKR1B10-mediated metabolism of daunorubicin as a novel off-target effect for the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib. Biochem. Pharmacol. 192, 114710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114710 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Endogenous sterol intermediates of the mevalonate pathway regulate HMGCR degradation and SREBP-2 processing. J. Lipid Res. 60, 1765–1775. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.RA119000201 (2019).

Pokhrel, R. H. et al. AMPK promotes antitumor immunity by downregulating PD-1 in regulatory T cells via the HMGCR/p38 signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer 20, 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01420-9 (2021).

Daubon, T. et al. Deciphering the complex role of thrombospondin-1 in glioblastoma development. Nat. Commun. 10, 1146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08480-y (2019).

Khoshdel, F. et al. CTGF, FN1, IL-6, THBS1, and WISP1 genes and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway as prognostic and therapeutic targets in gastric cancer identified by gene network modeling. Discov. Oncol. 15, 344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-024-01225-4 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Guangxi Botanical Garden for providing authenticated medicinal plant materials and technical support in sample preparation. We thank the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Sequence Read Archive team for facilitating the deposition of transcriptomic data (Bioproject number: PRJNA1115821). This work was supported by 1. Guangxi Natural Science Foundation Program (2023GXNSFBA026354)2. Guangxi Scientific research and technology development program project (Guikezhong1598005-14)3. Guangxi Key Laboratory of Medicinal Resources Protection and Genetic Improvement (KL2022ZZ01).

Funding

Xiaonan Yang, 2023GXNSFBA026354, Xianghua Xia, Guikezhong1598005-14, Xianghua Xia, KL2022ZZ01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tingting Hao:Methodology, Supervision, Writing-original draft and visualization. Xiaonan Yang: Data curation, Resources and Funding acquisition. Weibin Wang: Software,validation,Data curation and Writing-review & editing. YanqiLiu, Die Jiang, Li Hongmei, Ru Zhang: Formal analysis, Investigation. Zhu Qiao: Data curation and Methodogoly; Xing Jiang: Investigation; Xiaolei Zhou: Resources; Dandan Mo: Resources; Wenqing Su: Investigation; Wendong He: Investigation; Xianghua Xia: Resources and Funding acquisition. Qiang-qiang Zhu, Qinghua Kong: Resources. Yang Dong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, T., Yang, X., Wang, W. et al. Systems pharmacology approaches decipher the anti-cancer efficacy of ethnopharmacological agents in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 43996 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27744-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27744-w