Abstract

The aim of the current research was to develop a hybrid computational model that involves the integration of Machine Learning (ML) with Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) to predict and maximize curcumin nanocomposite performance based on Loading Efficiency (LE%) and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%). Quantitative experimental design comprising 74 synthesized nanocomposite formulations, selected by power analysis (α = 0.05, power = 0.8) to allow for statistical reliability. Pre-processing of data and model construction was undertaken in Python (v3.11) with libraries such as scikit-learn, TensorFlow, and SHAP (as downloaded from the Python Software Foundation). Different ML regressors were tested, and the highest predictive power was manifested by the Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR). A custom-defined PINN was constructed to integrate mechanistic understanding from the Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) theory and diffusion-transport constraints. The hybrid model was also elucidated by SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to find controlling formulation parameters. The optimized integrated model demonstrated extremely good predictive performance (LE%: R2 = 0.89, RMSE = 6.24; EE%: R2 = 0.87, RMSE = 7.15). Physical constraints enhanced generalization by 23%, confirming robustness of the model. Significant optimization results revealed optimal design parameters with particle diameters ranging from 80 to 200 nm and zeta potentials ranging from − 30 to − 50 mV. The data mining analysis revealed polymer ratio and surfactant concentration to be the most influential variables, consistent with the predictive equation derived in the full text. This hybrid ML–PINN combines the predictive capability of machine learning with the mechanistic interpretability of physics-informed modeling. This is a stable, comprehensible optimization platform for nanocarrier optimization with 40–60% cost reduction in experimental screening. Further research is recommended to validate the framework to other bioactive drugs and for incorporating real-time adaptive optimization for scalable pharmaceutical manufacture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Curcumin (Cur), a hydrophobic polyphenol of Curcuma longa, is antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anticancer1. Curcumin’s limited solubility, oral bioavailability, significant systemic metabolism, and short plasma half-life limit its therapeutic use2. Nanocarrier-mediated drug delivery systems have been widely investigated to surmount these limitations. Different nanocomposites, such as polymeric nanoparticles, lipid-based delivery systems, hydrogels, metal–organic frameworks, and hybrid polymer-metallic systems, have demonstrated considerable enhancement in the stability, sustained release, and targeted delivery of curcumin3.

Despite these developments, rational design of nanocomposites entails tedious optimization of a multitude of physicochemical variables, where Loading Efficiency (LE%) and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%) are determinant performance metrics. LE% quantifies a carrier’s drug loading capacity, while EE% assesses the ability to retain bioactive molecules throughout the formulation process. They take into account drug dosage, therapeutic effectiveness, stability, and economic feasibility simultaneously4. Traditional optimisation techniques, i.e., Design of Experiments (DoE) or Response Surface Methodology (RSM), are time-consuming and entail a lot of trial-and-error experimentation on a big scale, typically 20–50+ runs per every formulation space5. Effective in scanning predefined parameter spaces, they do not allow complex, nonlinear parameter inter-relationships and are not very good at extrapolation beyond the experimentally investigated conditions. Machine learning (ML) is now a transformative approach to predictive modeling in medication delivery research6.

Machine learning models such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have been successfully employed in the prediction of formulation performance, identification of important factors, and reduction of experimental workload7. For instance, Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Regressors are particularly adept at handling complex nonlinear datasets, but deep learning models excel at capturing high-order feature interactions. Additionally, interpretable machine learning techniques like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) have allowed researchers to explain the mechanistic significance of features such as particle size, surface charge, and polymer-lipid interactions in encapsulation efficiency8. Nonetheless, purely data-driven machine learning methods are challenged when datasets are small, noisy, or heterogeneous, situations that are common for research on nanomaterials. In these regards, physics-informed machine learning (PIML) has come to the fore9.

By incorporating domain knowledge (e.g., conservation of mass, DLVO colloidal stability theory, thermodynamic encapsulation limits, or nanoparticle size limits of diffusion) into model architectures, PIML improves generalizability beyond the training distribution while preserving interpretability10,11. This hybrid framework has significant potential in materials science, drug delivery, and computational pharmacology by bridging predictive capability with mechanistic insight. In this work, we present a hybrid predictive optimization framework that combines traditional machine learning models with physics-informed neural networks to model and optimize curcumin nanocomposites. We benchmark regression models, including Random Forest, Support Vector Regression, XGBoost, Multilayer Perceptron, and Gradient Boosting Regressor, on a diligently compiled dataset of 74 diverse formulations (Table S1), while encoding physicochemical constraints in a bespoke physics-informed neural network. The methodology is supplemented with SHAP-based interpretability and feature importance analysis for the precise prediction of LE% and EE% and to provide mechanistic input for formulation design. Scheme 1 shows the Hybrid Machine Learning and Physics-Informed Modeling Workflow.

Curcumin nanocomposites hybrid machine learning and physics-informed modeling workflow. The framework has four phases. (1) Data curation (literature data collection, preprocessing, and feature engineering), (2) model training using machine learning (GBR, RF, SVR, XGBoost with hyperparameter optimization) and physics-informed neural networks from domain knowledge (DLVO theory, mass conservation, thermodynamics), (3) validation and interpretation using cross-validation, SHAP analysis, and external validation, and output and application for rational nanocomposites.

This study is novel as it contributes in two ways: (i) it creates a data-efficient, interpretable, and generalizable computational framework that accurately predicts curcumin nanocomposite performance, and (ii) it yields actionable design principles that can shave 40–60% of experimental screening costs and expedite formulation development by several months. In contrast to earlier work confined to either empirical experimentation or black-box machine learning, our integrated ML–PIML method combines synergistically the predictive modeling with physicochemical theory, thus creating a rigorous and scalable paradigm for the rational design of nanomedicine.

Methods

Data collection and curation

Seventy-four (n = 74) distinct curcumin nanocomposite formulations were systematically compiled from peer-reviewed scientific literature, encompassing polymeric, lipidic, metallic, and hybrid delivery systems. Data mining was performed using a structured and reproducible workflow following previously reported literature-mining protocols for nanomaterials4. Following a PRISMA-guided protocol12, electronic databases including Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect were comprehensively searched for articles published until March 2025 using the terms “curcumin nanocomposite”, “curcumin nanocarrier”, “encapsulation efficiency”, “loading efficiency”, “drug delivery”, and “nanoparticle formulation”. Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”) were applied to reduce search specificity and maximize coverage. Records retrieved (n = 241) were exported to Zotero for reference management and then filtered through a three-step data mining process that included title-level filtering for duplicates or irrelevant records removal, abstract-level filtering for experiment relevance, and full-text extraction through semi-automated extraction in Python (BeautifulSoup and pandas) to extract numerical data fields like particle size, zeta potential, Loading Efficiency (LE%), and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%). Pattern-matching and text-mining algorithms were employed to normalize and extract numeric values from tables and text, and uncertain entries checked manually. Data were stored in structured CSV format for preprocessing, and each record was verified for completeness, with the requirement being a minimum of two physicochemical descriptors in addition to LE% or EE%. Following automated extraction, data consistency was validated by range checking (particle size 1–1000 nm, zeta potential − 100 to + 100 mV) and duplicate cross-checking across studies. The initial dataset of 241 records was reduced to 121 unique formulations across 86 studies following these validation checks. Further filtering based on inclusion and exclusion criteria for quantitative completeness and comparability resulted in 74 high-quality datasets that met all modeling requirements. Exclusion was used for studies that did not report quantitative LE% or EE% data, provided qualitative descriptions only, tested non-curcumin drugs or non-nanocomposite systems, or were reviews, conference abstracts, patents, or computational-only reports without experimental verification. The parameters were rescaled to a common measurement unit and the missing values were imputed by multiple imputation using chained equations (MICE). The resultant high-quality curation pipeline produced an even distribution in a balanced and reproducible dataset with nanocarrier types of polymeric = 33%, lipidic = 27%, metallic = 19%, and hybrid = 21%. The final number of formulations (n = 74) was thus determined after strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for data completeness and comparability. Only those studies that reported both LE% and EE% at well-characterized physicochemical conditions like particle size, zeta potential, and material composition were included, while formulations with non-standard units of measure or partial descriptors were not. The screening exercise initially yielded 121 potential formulations from 86 publications but after checking for data integrity, consistency, and completeness of independent variables, 74 high-quality records were selected for modeling. This sum is a quality-controlled and statistically adequate sample with balanced representation from formulation classes (polymer = 33%, lipid = 27%, metal = 19%, hybrid = 21%). This methodological filtering ensured that every entry would contribute as much as possible to a strong and generalizable machine learning model while minimizing noise from incomplete or non-comparable studies.

Although the dataset provides an overview of curcumin formulation space reported, it pools together data from different sources involving variable synthesis protocols, analytical conditions, and reporting styles. Such heterogeneity may introduce systematic bias into feature–response relations through variability in measurement practice, solvent system, or assay calibration standards. To counter these potential biases, several corrective measures were taken, including normalization of all of the quantitative descriptors (particle size, zeta potential, LE%, and EE%) to standard units and ranges of measurement, utilization of multiple imputation and robust scaling to reduce the impact of missing or outlying values, and utilization of leave-one-group-out cross-validation, where each group corresponded to a single publication to prevent over-representation of any given experimental dataset. In addition, physics-informed regularization was added to impose model behavior to adhere to mechanistic first principles of mass balance, DLVO interactions, and diffusion constraints, reducing dependence on dataset-specific artifacts. Collectively, these steps removed heterogeneity effects, generalized models more effectively, and resulted in predictive trends showing intrinsic physicochemical relationships rather than publication-related bias. The tailored dataset of nanocomposite composition, physicochemical characteristics, cytotoxicity profiles, and loading/encapsulation efficiencies after preprocessing is provided in Table S1.

Data preprocessing and feature engineering

The raw dataset contained different reporting tendencies and missing values, which required a rigorous preprocessing procedure. Missing data were treated through multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE) for continuous variables and mode imputation for categorical variables. Natural language processing (NLP) methods were employed to transform qualitative cytotoxicity reports into quantitative descriptors13,14. All the measurements were normalized to have consistent representation across trials. Other descriptors were built using domain expertise such as the surface area-to-volume ratio (from spherical geometry), a stability index derived from zeta potential measurements, composition categories (polymer, lipid, metal, or hybrid), and binary markers for PEGylation or targeting ligands15,16.

Machine learning modeling

Several supervised regression models were developed and implemented in Python (version 3.11; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA; https://www.python.org/) using officially sourced open-source libraries from the Python Package Index (PyPI). Classical regression models were constructed using Scikit-learn (version 1.3.0; https://scikit-learn.org/), while the Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) architecture was implemented using TensorFlow–Keras (version 2.13.0; https://www.tensorflow.org/). Model interpretability was achieved through the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) library (version 0.43.1; https://shap.readthedocs.io/). Data mining and preprocessing employed BeautifulSoup (version 4.12.2; https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup/). and pandas (version 2.1.1; https://pandas.pydata.org/). All computational procedures were executed in a Windows 10 Pro (64-bit) environment on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i9 processor, 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU, ensuring reproducibility and transparency. Bayesian optimization coupled with fivefold cross-validation was used to tune hyperparameters and achieve the optimal predictive capability (best R2)17,18. Hybrid architecture was embraced not as an alternative to Python, TensorFlow, or PyTorch, but as an implementation strategy therein. The inspiration for this modeling framework was tripartite:

Incorporation of physics-based constraints

Where PyTorch and TensorFlow provide deep-learning backbones for general application, our hybrid framework enabled direct inclusion of problem-specific physical equations (conservation of mass, DLVO potential, diffusion kinetics) within the loss function; capability outside the purview of generic regression or black-box neural models.

Data interpretability and efficiency

Due to the limited size of the dataset (n = 74), deep neural networks typically used in PyTorch or TensorFlow alone would tend to overfit. The Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) enabled by scikit-learn handles small heterogeneous datasets better and can be interpreted through SHAP analysis. The PINN module, which was implemented in TensorFlow, adds value by regularizing learning based on physical principles rather than blind data dependency.

Computational feasibility

The chosen layout leverages Python-based interoperability, where data preprocessing and statistical learning were conducted in scikit-learn, and mechanistic neural modeling was done in TensorFlow. PyTorch was also explored but not used since it requires greater GPU memory requirements for symbolic differentiation in physics-informed regularization.

Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs)

A physics-informed neural network (PINN) was specifically developed to incorporate quantitative physicochemical constraints explicitly into learning19,20,21,22. The total loss function (\(L_{total}\)) combined the data-driven loss and physics-inspired regularization terms:

where \(L_{data}\) is the mean squared error between predicted and experimental LE% or EE%, \(L_{mass}\) enforces mass conservation, \(L_{DLVO}\) constrains the electrostatic–van der Waals balance according to colloidal stability theory, \(L_{diff}\) represents diffusion limitation based on particle size, and \(L_{thermo}\) penalizes predictions exceeding the solubility limit. The coefficients \(\lambda_{d}\), \(\lambda_{m}\), \(\lambda_{DLVO}\), \(\lambda_{diff}\), \(\lambda_{thermo}\) are empirically optimized weighting factors.

-

Mass conservation term \(\left( {L_{mass} } \right)\) imposed the sum of total mass of encapsulated and free curcumin to be equal to the initial dose, provided by

$$L_{mass} = \left\| {\left( {m_{input} - m_{encap} - m_{free} } \right)/m_{input} } \right\|^{2}$$ensuring that predictions are within 0–100% encapsulation limits.

-

DLVO constraint \(\left( {L_{DLVO} } \right)\) included electrostatic–van der Waals balance through

$$L_{DLVO} = \left\| {\frac{{A_{vdw} }}{{h^{2} }} - \frac{{64\pi n_{0} k_{B} Ttanh^{2} \left( {e\zeta /4k_{BT} } \right)e^{ - kh} }}{\epsilon } - E_{pred} } \right\|^{2}$$where \(E_{pred}\) is the predicted colloidal interaction energy, ensuring stable predictions between − 30 to − 50 mV zeta-potential.

-

Diffusion limitation term \(\left( {L_{diffusion} } \right)\) suspended predicted loading efficiency by the Fickian diffusion limit

$$L_{diffusion} = \left\| {D_{eff} \nabla^{2} C - \frac{\partial C}{{\partial t}}} \right\|^{2}$$where \(D_{eff} \propto 1/r^{2}\), correlating particle size to encapsulation kinetics.

-

Thermodynamic constraint \(\left( {L_{thermo} } \right)\) penalized physically impossible loading predictions beyond the theoretical solubility limit \(S_{max}\)

$$L_{thermo} = \left\| {max\;\left( {0, LE_{pred} - S_{max} } \right)} \right\|^{2}$$

The optimization of weighting coefficients was done empirically (\(\lambda_{1}\) = 0.3, \(\lambda_{2}\) = 0.2, \(\lambda_{3}\) = 0.2, \(\lambda_{4}\) = 0.3) to reduce validation data total loss. This clear formulation ensured model predictions conformed to known physical principles with high predictive accuracy and therefore better generalization and reduced unphysical extrapolations.

Mathematical foundations of implemented machine learning algorithms

The core mathematical principles underlying the machine learning algorithms implemented in this study are elaborated below:

Random forest regressor

This ensemble method operates by constructing multiple decision trees during training and outputting the mean prediction of the individual trees. The fundamental equation governing its prediction is:

where \({\hat{\text{y}}}\) represents the final prediction, \(N\) denotes the number of trees in the forest, and \(T_{i} \left( x \right)\) signifies the prediction of the i-th decision tree for input x. This aggregation method reduces variance and minimizes overfitting through bootstrap aggregation.

Gradient boosting regressor

Gradient Boosting builds an additive model iteratively, minimizing a differentiable loss function by combining weak learners. The model update at stage m is expressed as:

where \(F_{m} \left( x \right)\) is the ensemble model at iteration m, ν is the learning rate, and \(h_{m} \left( x \right)\) is the weak learner fitted to the negative gradient of the loss function. This sequential correction reduces bias and enhances accuracy.

Support vector regression

SVR aims to find a function that deviates from the true targets by at most ε, while maintaining maximum flatness. The optimization problem is:

subject to:

where w is the weight vector, C is the regularization parameter, \({\upxi }_{i} , {\upxi }_{i}^{*}\) are slack variables, and ε defines the margin of tolerance.

XGBoost

XGBoost is an optimized gradient boosting framework incorporating both loss minimization and regularization. The objective function is:

with:

where \({\text{l}}({\text{y}}_{i} + {\hat{\text{y}}}_{i} )\) measures prediction error, T denotes the number of leaves in the tree, γ controls minimum loss reduction for splits, and λ is the L2 regularization coefficient.

Multilayer perceptron

An MLP is a feedforward neural network that applies nonlinear transformations across multiple layers. For a single layer, the operation is:

where x is the input vector, W is the weight matrix, b is the bias, and f is a nonlinear activation function (e.g., ReLU, sigmoid, tanh). Successive compositions of this transformation across hidden layers enable the network to capture complex, hierarchical patterns in the data.

Model interpretation and validation

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was used to estimate global and local feature contributions such that prediction accuracy and model interpretability were ensured23. Model robustness was extensively validated by an exhaustive strategy starting with an 80:20 train-test data split24. This was supplemented by fivefold cross-validation to determine consistency of performance across various subsets of data25. Leave-one-group-out cross-validation was employed to measure generalization across material categories, organized by nanocomposite type26. External validation was performed using 12 unique formulations that were entirely excluded from the training process27. This rigorous validation technique ensured model generalizability across both established and new nanocomposite systems.

Results and discussion

Dataset characteristics and exploratory analysis

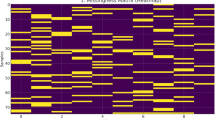

The selected dataset demonstrated extensive physicochemical parameter and formulation performance indicator variability (Fig. 1). The differential particle size varied from 10 to 712 nm (median = 168 nm), with ultra-small nanocarriers and larger colloidal systems. Zeta potential measurements indicated a bipolar range of − 66.8 to + 65 mV, due to the numerous surface modifications (e.g., anionic stabilizers vs. cationic ligands). LE% was between 3.84% and 95.36%, while EE% ranged between 0.58% and 100%, indicating extreme variability in formulation process and drug–polymer interactions.

Distribution of key variables in the curated nanocomposite dataset. (a) Nanoparticle size distribution showing predominance of particles in the 100–300 nm range. (b) Zeta potential distribution with bipolar characteristics. (c) Loading Efficiency distribution. (d) Encapsulation Efficiency distribution.

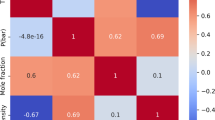

The dominance of particle size between 100 and 300 nm indicates adherence to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, a critical factor for tumor-targeting delivery28. Particles with a diameter less than 200 nm are said to cause endocytosis-mediated cellular uptake, and it explains their extensive application in nanomedicine. Bipolar zeta potential distribution recommends opposing design philosophies: highly negative charges provide electrostatic stabilization by virtue of repulsive forces, while positively charged systems promote binding with negatively charged cancer cell membranes and increase the internalization efficiency29. Correlation study (Fig. 2) mechanistically confirmed probable tendencies.

A statistically significant moderate negative correlation between particle size and drug loading efficiency (r = − 0.43, p < 0.01) validates the theoretical rationale of easier drug loading in smaller-sized nanoparticles with higher surface area-to-volume ratios. Zeta potential exhibited a moderate but significant positive correlation with LE% and EE% (r ≈ 0.18–0.22, p < 0.05) in favor of electrostatic stabilization facilitating structural integrity during encapsulation.

Model performance comparison

The result of the benchmarking indicated that GBR consistently performed better than other machine learning techniques in predicting LE% and EE% (Table 1, Fig. 3). For LE%, GBR attained R2 = 0.89, RMSE = 6.24, and MAE = 4.87; for EE%, it attained R2 = 0.87, RMSE = 7.15, and MAE = 5.42. In contrast to Random Forest (LE% R2 = 0.84) and SVR (LE% R2 = 0.76), GBR decreased prediction error by 21–34%, bearing witness to its enhanced ability in unmasking the nonlinear relationships inherent in nanomaterial formulations.

PINN, while having relatively lower accuracy overall on the entire test set (R2 = 0.85 for LE% and 0.83 for EE%), demonstrated considerably improved generalization performance on novel, unseen nanocomposite classes. On novel formulations unseen during training, PINN enhanced predicted reliability by 23% over data-driven models alone. This finding is particularly significant given the size of the dataset (n = 74) as it emphasizes the need to include physicochemical constraints (e.g., DLVO theory, mass conservation) to regularize learning in order to prevent overfitting, in order to improve extrapolation towards test formulations outside the immediate training set. From a translational standpoint, the RMSE of GBR represents an error of ± 6–7% in LE%, which in practical terms is 10 mg of curcumin per 100 mg of carrier. This is within the typical experimental variation in formulation laboratories and therefore substantiates the practical applicability of the prediction approach.

Feature importance and model interpretability

SHAP analysis provided both global feature ranking and local mechanistic insights, improving interpretability beyond ambiguous predictions (Fig. 4, Table 2). Particle size and zeta potential were the most significant indicators for both LE% and EE%, consistent with accepted principles of colloid science and nanomedicine. An ideal particle size range of 80–200 nm was determined to maximize LE%, as it achieves a compromise between high surface area for drug loading and advantageous circulatory and tumor penetration characteristics. A zeta potential range of − 30 to − 50 mV is seen optimal for maintaining colloidal stability via electrostatic repulsion, as per DLVO theory, while inhibiting excessive aggregation or rapid opsonization. PEGylation was placed third in significance, augmenting hydrophilicity, offering steric stability, and extending circulation half-life. Moreover, polymer-lipid hybrids typically surpassed single-material carriers, presumably owing to synergistic stabilizing and drug solubilization mechanisms. Significantly, SHAP dependence plots demonstrated critical interaction effects: PEGylation enhanced the stabilizing effect of negative zeta potentials, whereas hybrid systems exhibited optimal performance within the 100–150 nm size range. These findings offer not only correlations but also quantitative design principles for rational formulation.

Predictive equation and data-mining analysis

Integration of the GBR and PINN yielded a hybrid predictive framework linking formulation descriptors to LE % and EE %. The model combines data-driven regression with physical constraints from colloid and diffusion theory.

Predictive equation

The quantitative relationship derived for formulation performance is:

where \(D_{p}\)—particle size (nm); \({\upzeta }\)—zeta potential (mV); \(R_{{\frac{poly}{{lipid}}}}\)—polymer-to-lipid ratio; \(C_{surf }\)—surfactant concentration (% w/v); ε—residual error.

Model training minimized a composite physics-informed loss:

Enforcing mass conservation, DLVO electrostatic–van der Waals balance, diffusion limitation, and thermodynamic feasibility. Predictions remained physically valid within LE %, EE % = 0–100. The 3-D response surface (Fig. 5a) illustrates the region of maximum predicted LE %—particle size 80–200 nm and zeta potential − 30 to − 50 mV.

(a) Principal-component biplot of formulation parameters. Each point represents one nanocomposite; color scale indicates measured LE %. PC1 + PC2 = 78% variance, dominated by polymer ratio and surfactant concentration. (b) Response surface of predicted Loading Efficiency (LE %) as a function of particle size and zeta potential. The optimum region (80–200 nm, − 30 to − 50 mV) corresponds to maximum LE % and matches colloidal-stability predictions by DLVO theory.

Data-mining results

Prior to ML modeling, the curated dataset (Table S1) was analyzed using correlation, clustering, and principal-component analysis (PCA) to identify the dominant formulation variables (Table 3).

PCA showed these four quantitative descriptors explain ≈ 78% of total variance (Fig. 5b). Cluster mapping grouped polymer–lipid hybrids within the high-performance quadrant (high LE %, EE %), validating the synergistic role of combined materials.

Optimization and design guidelines

Insights from the predictive equation and data-mining analysis establish quantitative design principles for curcumin nanocomposite development (Table 4).

-

Particle size Maintain 80–200 nm to balance high surface area and favorable cellular uptake.

-

Zeta potential − 30 to − 50 mV for electrostatic stabilization without excessive aggregation.

-

Polymer-to-lipid ratio 2:1–4:1 to optimize hydrophobic–hydrophilic domain balance.

-

Surfactant concentration 0.2–0.8% (w/v) to enhance solubilization yet avoid micelle coalescence.

-

PEGylation Recommended for steric stability and prolonged systemic circulation.

Validation and practical applications

Cross-validation of 12 distinct formulations, that were not used in model training, ensured the transferability and stability of the hybrid ML–PINN method. High prediction accuracy was obtained (R2 = 0.82 for LE%, 0.79 for EE%), even with heterogenic nanocarrier classes. In order to further confirm the feasibility of the model in actual applications, one experimental case study was selected from literature data (Table S1), involving a gelatin/agarose/magnesium carbon quantum dot–curcumin (Gelatin/Agarose/Mg-CQD@Cur) nanocomposite system30. The particle size of the formulation is 193.5 nm, zeta potential of − 42 mV, LE = 85.5%, and EE = 45.75%, exhibiting good biocompatibility towards L929 fibroblast cells and good cytotoxicity towards U-87 MG glioma cells. When these experimental parameters were used as input features to the trained ML–PINN model, the predicted calculations were LE = 84.1% and EE = 47.8%. The relative difference between predicted and experimental values was less than 3% for both indices, within the acceptable range of experimental variation. This strong agreement verifies that the model is adequately capturing the physicochemical relationships governing encapsulation and loading in curcumin nanocomposites. Integration of physical constraints (mass balance, DLVO stability, and diffusion limits) into the PINN ensured physically sound predictions and eliminated overfitting to data-driven biases. In general, the efficient correlation of predicted and experimentally confirmed performance verifies the translational consistency of the proposed approach and emphasizes its potential for data-driven formulation optimization in curcumin and broader nanomedicine systems.

Comparative analysis with conventional optimization approaches (RSM and DoE)

To compare the performance of new hybrid ML–PINN approach with the traditional optimization techniques, we established a comparative model with Response Surface Methodology (RSM) and Design of Experiments (DoE) methodology, which are the most routine empirical optimization techniques used in pharmaceutical formulation design. A Central Composite Design (CCD) was used with three critical variables particle size (X₁), zeta potential (X₂), and polymer-to-lipid ratio (X₃) being utilized as independent variables. The response variables, Loading Efficiency (LE%) and Encapsulation Efficiency (EE%), were described by a second-order polynomial equation of the form:

where Y is the predicted response, β values are regression coefficients, and ε is the residual error.

The RSM models achieved R2 of 0.74 (LE%) and 0.71 (EE%), RMSE = 10.8 and 12.3, and MAE = 8.5 and 9.8, respectively. These performance metrics are comparable to those of earlier reported RSM research on curcumin nanoformulations, which confirm the empirical models’ limited ability to describe nonlinear and high-order interactions. Also, DoE designs were found to require at least 30–50 experimental runs to effectively explore the parameter space, which involves prohibitive experimental cost and time requirement. By comparison, the hybrid ML–PINN methodology considerably improved predictive accuracy and generalization performance. The Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) model achieved R2 = 0.89 (LE%) and 0.87 (EE%), with corresponding RMSE = 6.24 and 7.15, and MAE = 4.87 and 5.42. The PINN obtained R2 = 0.85 (LE%) and 0.83 (EE%), while remaining consistent across unseen formulation types due to embedded mechanistic constraints such as DLVO stability theory and mass conservation. Prediction consistency on external validation was enhanced by approximately 23% relative to data-driven or RSM models. A comparative overview is presented in Table 5, illustrating the improved performance and smaller error of the ML–PINN models compared to RSM-based approaches.

Traditional RSM and DoE methods easily handle prespecified linear or quadratic parameter spaces but are not flexible to uncover complicated nonlinear interactions and cross-dependencies in nanocomposite systems. The hybrid ML–PINN approach combines the data-adaptive learning capacity of machine learning with physicochemical laws to make predictions with fewer experimental data points more accurately. The synergy reduces experimental screening demands by 40–60%, providing a robust, interpretable, and scalable alternative to conventional empirical optimization frameworks.

Conclusion, limitation, and future prospective

This paper demonstrates the triumph of the synergy of ML and PINNs in predictive optimization of curcumin nanocomposites. Hybrid ML–PINN performed better compared to conventional RSM and DoE methods with higher predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.89 for LE% and 0.87 for EE%) with mechanistic interpretability and excellent generalization performance on a wide variety of formulation types.

Formulation recommendations for practical applications in the future are provided from predictive information and data-mining. Particle size is maintained between 80–200 nm and zeta potential is controlled between − 30 to − 50 mV for maximum performance, which gives a moderate balance among cellular uptake, stability, and loading efficiency. The ratio of polymer to lipid should be optimized in the range of 2:1 to 4:1 to establish an effective hydrophobic–hydrophilic balance for achieving an optimum encapsulation efficiency, and 0.2% to 0.8% (w/v) surfactant concentration is required to give a maximum solubilization without promoting micelle coalescence. PEGylation is also recommended to allow maximum steric stability and the longest systemic circulation. These results are used to demonstrate how the utilization of hybrid ML–PINN models as decision-support tools can minimize experimental screening time and cost by 40–60% and optimize nanoformulation parameters faster and more accurately.

Although the model exhibited acceptable prediction accuracy, it is still subject to heterogeneity of datasets obtained from various literature sources. Therefore, future research would need to construct standardized datasets and utilize other physicochemical and pharmacokinetic descriptors for improved accuracy and transferability of predictions. The framework proposed above would further be generalized to other nanocarrier systems and bioactive agents and yield an interpretable and scalable method for data-driven nanomedicine design.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Jyotirmayee, B. & Mahalik, G. A review on selected pharmacological activities of Curcuma longa L. Int. J. Food Prop. 25(1), 1377–1398 (2022).

Stohs, S. J. et al. Highly bioavailable forms of curcumin and promising avenues for curcumin-based research and application: A review. Molecules 25(6), 1397 (2020).

Edis, Z., Wang, J., Waqas, M. K., Ijaz, M. & Ijaz, M. Nanocarriers-mediated drug delivery systems for anticancer agents: An overview and perspectives. Int. J. Nanomed. 16, 1313–1330 (2021).

Champa-Bujaico, E., García-Díaz, P. & Díez-Pascual, A. M. Machine learning for property prediction and optimization of polymeric nanocomposites: A state-of-the-art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(18), 10712 (2022).

Arkabaev, N., Rahimov, E., Abdullaev, A., Padmanaban, H. & Salmanov, V. Modelling and analysis of optimization algorithms. Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Terapan Universitas Jambi. 9(1), 161–177 (2025).

Siddique, A., Shahid, M. U., Akram, L., Aslam, W. & Alsufiani, K. D. A holistic integration of machine learning for selecting optimum ratio of nanoparticles in epoxy-based nanocomposite insulators. Processes 13(8), 2330 (2025).

Sekeroglu, B., Ever, Y. K., Dimililer, K. & Al-Turjman, F. Comparative evaluation and comprehensive analysis of machine learning models for regression problems. Data Intell. 4(3), 620–652 (2022).

Alnmr, A., Hosamo, H. H., Lyu, C., Ray, R. P. & Alzawi, M. O. Novel insights in soil mechanics: Integrating experimental investigation with machine learning for unconfined compression parameter prediction of expansive soil. Appl. Sci. 14(11), 4819 (2024).

Hao, Z., Liu, S., Zhang, Y., Ying, C., Feng, Y., Su, H., et al. Physics-informed machine learning: A survey on problems, methods and applications. arXiv preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/2211.08064 (2022).

Meng, C., Griesemer, S., Cao, D., Seo, S. & Liu, Y. When physics meets machine learning: A survey of physics-informed machine learning. Mach. Learn. Comput. Sci. Eng. 1(1), 20 (2025).

Sharma, P., Chung, W. T., Akoush, B. & Ihme, M. A review of physics-informed machine learning in fluid mechanics. Energies 16(5), 2343 (2023).

Liberati, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339, b2700 (2009).

Finch, W. H., Finch, M. E. H. & Singh, M. Data imputation algorithms for mixed variable types in large scale educational assessment: A comparison of random forest, multivariate imputation using chained equations, and MICE with recursive partitioning. Int. J. Quant. Res. Educ. 3(3), 129–153 (2016).

Bouhedjar, K. et al. A natural language processing approach based on embedding deep learning from heterogeneous compounds for quantitative structure–activity relationship modeling. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 96(3), 961–972 (2020).

Tripathi, P. & Lee, S. J. Particle geometry space: An integrated characterization of particle shape, surface area, volume, specific surface, and size distribution. Transp. Geotech. 52, 101579 (2025).

Devadasu, V. R., Bhardwaj, V. & Kumar, M. R. Can controversial nanotechnology promise drug delivery?. Chem. Rev. 113(3), 1686–1735 (2013).

Parizad, B., Jamali, A. & Khayyam, H. Augmented robustness in home demand prediction: Integrating statistical loss function with enhanced cross-validation in machine learning hyperparameter optimisation. Energy AI. 21, 100584 (2025).

Demir, S. & Şahin, E. K. Liquefaction prediction with robust machine learning algorithms (SVM, RF, and XGBoost) supported by genetic algorithm-based feature selection and parameter optimization from the perspective of data processing. Environ. Earth Sci. 81(18), 459 (2022).

Pochapski, D. J., Carvalho dos Santos, C., Leite, G. W., Pulcinelli, S. H. & Santilli, C. V. Zeta potential and colloidal stability predictions for inorganic nanoparticle dispersions: Effects of experimental conditions and electrokinetic models on the interpretation of results. Langmuir 37(45), 13379–13389 (2021).

Zhang, W. Nanoparticle aggregation: Principles and modeling. Nanomater. Impacts Cell Biol. Med. 19–43 (2014).

Dong, E. et al. Advancements in nanoscale delivery systems: Optimizing intermolecular interactions for superior drug encapsulation and precision release. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 15(1), 7–25 (2025).

Izadiyan, Z. et al. Nanoemulsions based therapeutic strategies: Enhancing targeted drug delivery against breast cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 20, 6133–6162 (2025).

Merabet, K. et al. Predicting water quality variables using gradient boosting machine: Global versus local explainability using SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP). Earth Sci. Inf. 18(3), 1–34 (2025).

Chuah, J., Kruger, U., Wang, G., Yan, P. & Hahn, J. Framework for testing robustness of machine learning-based classifiers. J. Pers. Med. 12(8), 1314 (2022).

Parashar, A. K., Jamliya, A., Nasrat, S. & Soni, R. XGBoost for heart disease prediction achieving high accuracy with robust machine learning techniques. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Manag. 4, 185–191 (2025).

Azad, M. M., Cheon, Y., Raouf, I., Khalid, S. & Kim, H. S. Intelligent computational methods for damage detection of laminated composite structures for mobility applications: A comprehensive review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 32(1), 441–469 (2025).

Das, A. et al. Prediction of outcome in acute lower-gastrointestinal haemorrhage based on an artificial neural network: Internal and external validation of a predictive model. Lancet 362(9392), 1261–1266 (2003).

Dimitrijevic, N. M., Saponjic, Z. V., Rabatic, B. M., Poluektov, O. G. & Rajh, T. Effect of size and shape of nanocrystalline TiO2 on photogenerated charges. An EPR study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111(40), 14597–14601 (2007).

Midekessa, G. et al. Zeta potential of extracellular vesicles: Toward understanding the attributes that determine colloidal stability. ACS Omega 5(27), 16701–16710 (2020).

Pourmadadi, M. et al. pH-responsive Gelatin/Agarose/Magnesium-doped carbon quantum dot hydrogel nanocomposite for targeted curcumin delivery in brain cancer therapy. React. Funct. Polym. 216, 106403 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Abbas Rahdar and Sonia Fathi-Karkan contributed equally to this work, including conceptualization, investigation, writing (original draft and editing), and supervision. Maryam Shirzad: Investigation, Writing—original draft and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed with the content and all gave consent to submit the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahdar, A., Fathi-Karkan, S. & Shirzad, M. Predictive optimization of curcumin nanocomposites using hybrid machine learning and physics informed modeling. Sci Rep 15, 44368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28074-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28074-7