Abstract

Detecting manipulative environmental disclosures remains a critical yet unresolved challenge for regulators and investors. This study proposes a machine learning framework that integrates financial indicators, textual sentiment, and public attention data to identify potential manipulation among Chinese listed firms. A Random Forest model is trained using multi-source features derived from corporate reports and Baidu Index trends. The optimized model demonstrates strong discriminatory ability under severe class imbalance (ROC-AUC = 0.94, PR-AUC = 0.78, Balanced Accuracy = 0.86, MCC = 0.72), indicating robust and reliable performance across both majority and minority classes. Evaluation through balanced metrics further confirms the model’s genuine predictive capacity rather than overfitting to training data. SHAP-based interpretation reveals that financial pressure, abnormal public attention, and sentiment deviation are the primary determinants of manipulation risk. Overall, the framework highlights how interpretable machine learning can strengthen data-driven environmental supervision. The findings are context-specific to the Chinese market due to reliance on Baidu-based indicators, warranting validation in other regulatory contexts in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental degradation, with its profound and far-reaching effects on human health, biodiversity, and economic sustainability, has emerged as a pressing global issue. The World Health Organization reports that environmental risk factors contribute to approximately 23% of all deaths worldwide. In response, “environmental protection” has evolved from a mere conceptual framework into a vigorous, action-driven movement. As early as 1980, Neilson highlighted the growing societal concern regarding environmental degradation, a sentiment that has only intensified over the decades. Despite the increasing awareness and engagement, a persistent challenge remains in the realm of corporate environmental reporting. Studies indicate a significant discrepancy in the quality of environmental disclosures, attributing this to a blend of insufficient expertise and patchwork regulatory landscapes. Disturbingly, this gap has led some corporations to engage in the falsification of their environmental data. The role of accurate and transparent environmental reporting is pivotal. It not only links a company’s ecological efforts with public perception but also significantly influences the company’s market value. In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in voluntary environmental reporting by businesses. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) notes that over 75% of large companies worldwide now engage in some form of sustainability reporting. Simultaneously, regulatory frameworks have been evolving, albeit at an uneven pace across different regions.

The post-1997 era, marked by the China Securities Regulatory Commission’s release of the “No. 1 - Prospectus,” saw the introduction of numerous policies aimed at guiding listed companies in transparent environmental reporting1. These efforts were further supported by stock exchanges and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Despite these measures, the China Environmental Journalists Association points out that the surge in disclosure volume has not necessarily translated into enhanced quality. In fact, a study revealed that many companies selectively disclose only favourable environmental outcomes, often omitting crucial negative data2. This selective reporting hinders the goal of achieving green economic growth, which emphasizes the need for high-quality disclosures in fostering sustainable economic development1. However, the path to achieving comprehensive and honest environmental reporting is fraught with challenges. Lax regulatory oversight has led to instances of data manipulation by companies, complicating the pursuit of carbon neutrality goals.

This study seeks to bridge these gaps by developing a sophisticated machine learning model to detect manipulative practices in corporate environmental disclosures. Central to this research is the introduction of a comprehensive “pressure pool” index, which integrates financial, regulatory, and public pressure indicators to assess the risk of Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM). By combining these factors, the study presents a nuanced framework that captures the interplay between external scrutiny and internal governance dynamics. Advanced machine learning techniques, including the Random Forest algorithm paired with Borderline-SMOTE and ADASYN oversampling methods, are employed to address data imbalance challenges and improve model robustness. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the Random Forest model in detecting manipulated disclosures, outperforming other models such as logistic regression and decision trees. These methodological advancements provide not only a reliable detection tool but also actionable insights for regulatory authorities, paving the way for more transparent and sustainable corporate reporting practices.

This paper makes three contributions. First, it develops a practical detection framework that combines a pressure-pool index with tree-based models and fold-wise oversampling, which improves identification of manipulative environmental disclosures. Second, it compiles and validates a labeled dataset of corporate disclosures from Chinese listed firms and uses this dataset to benchmark classifiers and resampling strategies. Third, it provides a concrete screening tool for regulators and compliance teams to prioritize investigations and strengthen disclosure oversight. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on EIDM and related detection methods. Section 3 describes data collection, preprocessing, feature construction and the modeling pipeline. Section 4 reports experimental results and compares classifiers and resampling strategies. Section 5 concludes with implications, limitations and directions for future work.

Review of relevant literature

Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM) refers to the strategic distortion or selective presentation of environmental information to create a misleading impression of a firm’s environmental performance. It differs from ordinary reporting bias by involving intentional misrepresentation that affects stakeholders’ perception of compliance or sustainability commitment. Previous research has examined related constructs such as greenwashing3, CSR manipulation4, and selective disclosure5, but these studies typically emphasize symbolic communication or voluntary reporting tone rather than factual inconsistencies between disclosed and verified information. By integrating insights from these literatures, this study defines EIDM as a measurable form of environmental opportunism that bridges disclosure management and regulatory noncompliance. The concept aligns with both agency theory and stakeholder theory. From an agency view, managers engage in EIDM when exploiting information asymmetry to protect personal incentives or firm image. From a stakeholder view, EIDM emerges under competing pressures to maintain legitimacy amid growing scrutiny from regulators, investors, and the public. This framing positions EIDM as a critical, yet underexplored, mechanism linking corporate behavior, information asymmetry, and environmental governance.

Definitions and implications of environmental information disclosure manipulation (EIDM)

The Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM) represents a critical concern in the domain of environmental accounting, a discipline integral to addressing ecological challenges at a global scale. Environmental accounting serves as a systematic method to encapsulate an organization’s ecological impact, culminating in what is known as environmental information disclosure. The theoretical underpinnings of EIDM can be traced to Agency Theory6, which highlights the inherent conflict between managers and stakeholders regarding transparency and accountability. This conflict often leads to manipulative practices, especially when oversight mechanisms are weak. Stakeholder Theory further emphasizes the ethical obligation of corporations to provide accurate environmental disclosures, as they directly impact stakeholder decision-making7. EIDM occurs when corporations, driven by self-interest, produce skewed or misleading reports on their environmental footprint. Such distortions may take the form of under-reporting detrimental environmental impacts or inflating the benefits of eco-friendly initiatives. The repercussions of EIDM are far-reaching, often misleading stakeholders, investors, and the public, thereby misdirecting funds and support towards ventures that may be harmful to the environment. The concept of EIDM extends beyond the realm of “Green-washing”, which primarily refers to the practice of falsely promoting environmental responsibility through marketing and public relations efforts. In contrast, EIDM pertains specifically to the intentional manipulation of internal environmental reports and data. This manipulation is aimed at concealing the true extent of environmental harm caused by an organization’s operations, or at portraying a falsely enhanced image of its environmental stewardship.

Combatting EIDM requires a multifaceted approach aimed at reinforcing the transparency and veracity of environmental disclosures. This encompasses implementing stringent regulations that mandate accurate and comprehensive reporting of environmental data. Moreover, independent audits conducted by third parties can play a crucial role in verifying the authenticity of reported information, acting as a deterrent against manipulation. Engaging a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including environmental watchdogs, industry experts, and the public, is crucial in creating an environment where transparency is not just encouraged but demanded. Ensuring that organizations accurately represent their environmental impact is not merely a regulatory requirement; it is a fundamental aspect of corporate responsibility and ethical governance. Furthermore, the rise of digital technologies and data analytics offers new avenues to enhance the oversight and analysis of environmental reports. Leveraging these technologies can aid in the detection of anomalies or inconsistencies in reported data, providing an additional layer of scrutiny against EIDM practices. The goal is to foster a corporate culture where environmental accountability is ingrained and upheld, ensuring that organizations reported environmental performance aligns with their actual ecological footprint.

Indicators and methodologies for identifying EIDM

The task of identifying Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM) is nuanced due to its typically concealed nature. The development of a comprehensive identification index for EIDM is, therefore, a critical aspect of addressing this challenge. One study scoring method, one of the earliest frameworks for evaluating environmental disclosures, laid the foundation for subsequent studies8. Cormier and Magnan built on Wiseman’s approach, incorporating additional factors to provide a more comprehensive understanding of disclosure quality9. Despite these advancements, the subjective nature of these methods necessitates more objective, data-driven alternatives. This study incorporates machine learning methodologies to address these limitations. Research in this area underscores the importance of a multifaceted approach, considering both non-financial and financial factors that influence environmental information disclosure (EID). From a non-financial perspective, the impact of public pressure and governmental regulatory frameworks is significant. As noted by Li and Zhai and Shen, public scrutiny and regulatory policies play a pivotal role in shaping the EID practices of corporations10– 11. These factors can either incentivize truthful reporting or, conversely, predictive of increased incidences of EIDM when oversight is weak or public pressure is minimal. Financially, the research suggests that internal corporate dynamics significantly influence EID. Warfield pointed out the positive correlation between executive shareholdings and the quality of information disclosed, implying that a greater financial stake in the company can correlate with more transparent reporting12. Similarly, studies by Lee and Baldini13– 14 have respectively explored how firm size and financial leverage impact EID, suggesting larger firms or those with greater leverage may have more complex EID behaviors.

A key strategy in detecting EIDM lies in the assessment of the quality of environmental disclosure. The scoring method introduced by Wiseman8, which categorizes various aspects of environmental information, has been a foundational approach in this regard. This method was further developed by Cormier and Magnan9 among others, to provide a more nuanced understanding of EID. Despite its influence, Wiseman’s approach has been critiqued for its potential subjectivity and limitations in capturing the full spectrum of EIDM behaviors. Given these challenges, there is a growing consensus that future studies need to refine and expand upon these identification systems. This involves integrating more objective, data-driven methodologies and potentially leveraging advancements in technology and data analytics. The goal is to develop a more robust, multifaceted approach that can accurately detect and quantify EIDM, taking into account the diverse factors that contribute to this phenomenon. This could include the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to analyze large datasets of corporate disclosures, identifying patterns and anomalies that may indicate manipulative practices.

Advanced methodologies for measuring EIDM

Accurately identifying and measuring Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM) behavior is a critical aspect of ensuring corporate accountability in environmental stewardship. Recent advancements in machine learning have opened new possibilities for addressing the challenges of EIDM detection. Breiman’s Random Forest algorithm15, a seminal contribution to ensemble learning, provides a robust framework for analyzing complex datasets and has been utilized extensively in financial and environmental studies. Additionally, advancements in adaptive sampling strategies, such as the Borderline SMOTE technique Han16, have demonstrated significant potential in addressing class imbalances—a common issue in EIDM detection. Research has consistently shown that companies’ environmental disclosure can be significantly influenced by external factors, such as public pressure. This influence often results in selective disclosure, where companies may disproportionately highlight positive environmental impacts while minimizing negative ones, as detailed in studies by Gintschel and Markov17 and Hooghiemstra18.

One notable attempt to quantify this behavior was made by He19, who developed a model based on the “pressure bundle” concept, an adaptation of Jones’s20 framework. This model employed Propensity Score Matching (PSM) to analyze EIDM in Chinese firms. However, the model faced limitations due to its narrow scope and the exclusion of certain influential factors, thereby affecting its overall predictive accuracy. Recent advancements in technology, particularly in the field of machine learning, have opened new avenues for detecting and measuring EIDM more effectively. For example, Q. Liu et al.1 successfully applied machine learning techniques to detect manipulation in the stock market, demonstrating the effectiveness of the Borderline Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (Borderline SMOTE). Inspired by such advancements, this study aims to apply machine learning algorithms to enhance the identification of EIDM behaviors in corporate environmental disclosures.

One common challenge in machine learning, particularly relevant to EIDM detection, is class imbalance — a scenario where the instances of manipulation are significantly outnumbered by truthful disclosures. This imbalance can skew the model’s learning process, leading to inaccurate predictions. To address this, the study will employ sophisticated oversampling techniques, namely Borderline SMOTE and ADASYN. These techniques are designed to create balanced datasets by generating synthetic samples, particularly in the areas where the classification decision is most ambiguous. By focusing on these challenging boundary regions, these methods aim to enhance the classifier’s ability to discern between genuine and manipulative disclosures accurately. Thus, while traditional methodologies have provided foundational insights into EIDM behaviors, the integration of advanced machine learning techniques and adaptive sampling strategies is anticipated to significantly improve the precision and depth of our understanding of manipulative practices in environmental disclosures. These advancements not only promise more accurate identification but also pave the way for more nuanced analyses, ultimately contributing to more effective regulatory mechanisms and corporate governance practices in the field of environmental accountability.

Methodology

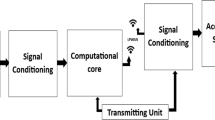

In addressing the complex challenge of Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM), this study introduces a novel machine learning-based model, marking a significant innovation in environmental regulation and corporate governance. The industrial relevance of this approach is profound, offering a technologically advanced solution for regulators and stakeholders to monitor and evaluate corporate environmental disclosures more effectively. This study advances prior approaches in several key areas. First, the integration of the ‘pressure pool’ index system, which incorporates region-specific features like Public Attention (Baidu Index), Institutional Supervision Pressure, and Regional GDP, provides a nuanced framework that captures the interplay of external scrutiny and internal governance dynamics. Unlike earlier studies that focused on static financial indicators, this multifaceted system dynamically reflects the broader regulatory and societal influences on corporate behavior. Second, the use of advanced machine learning techniques, including the Random Forest algorithm paired with Borderline-SMOTE and ADASYN oversampling methods, effectively addresses the challenges of class imbalance, which have often limited the predictive accuracy of previous models. Third, visualization techniques, such as scatter plots and boxplots, enhance transparency in the feature selection process, empirically justifying the inclusion of variables like ROA and Growth Rate.

The model leverages a multifaceted feature set, including Public Attention (Baidu Index), ROA, and Growth Rate, selected for their relevance to environmental compliance and corporate behavior. These features underwent rigorous pre-processing, including correlation analysis and integration into the “pressure pool” index, to ensure they contributed unique and meaningful insights to the predictive model. Assessment metrics include the confusion matrix method Provost and Kohavi1 covering Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score, along with the ROC curve Stein21 and AUC value. Collectively, these methodological advancements enhance the model’s robustness and provide actionable insights for regulatory authorities and stakeholders seeking to identify and mitigate manipulative practices in environmental disclosures.

Definition of “Manipulation”

In this paper, we use “manipulation” to mean deliberate actions by a firm that materially misrepresent, hide, or distort environmental information in public disclosures. The intent is to mislead stakeholders about environmental performance. We do not count honest reporting mistakes that are corrected, nor legitimate differences that arise from accepted accounting or measurement choices. For clarity, we separate three related concepts: (1) manipulation — intentional deception in disclosure; (2) regulatory violation — formal sanctions or penalties; and (3) greenwashing — promotional language that exaggerates environmental claims but may not amount to a legal breach.

We compiled panel data of Chinese A-share listed firms covering the period 2014–2022. The sample includes companies from energy-intensive and manufacturing sectors, where environmental disclosure is mandatory and manipulation risk is most salient. After merging financial, textual, and public-attention features, the dataset contains 8,624 firm-year observations from 1,048 unique firms. Continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers.

Variable definitions and scales were harmonized across tables. Supervisory Board Size in descriptive tables refers strictly to the number of supervisory members (range = 5–12). In regression analyses, Board Size represents the total number of directors, explaining the higher mean values (≈ 22–23). Public Attention (Baidu Index) was rescaled by dividing the original index values by 10 to maintain comparability with other numeric variables. A schematic of data processing and cleaning is presented in Fig. 2. The final sample distribution across industries and years is summarized in Table 2, while Table 4 reports normalized values used for model estimation.

Data sources and sample selection

We conducted an initial screening of corporate disclosures to flag potential manipulation cases using predefined textual and financial indicators. Labels were assigned by triangulating multiple sources: official enforcement announcements and penalty lists, regulator circulars and investigative reports, reputable media citing primary regulatory documents, and corporate correction or restatement notices. For Chinese records, we searched terms such as “环境处罚”, “行政处罚”, “罚款”, “环境违法”, and “通报”, along with equivalent English keywords. The screening process was transparent and reproducible. All steps and record counts were logged. First, we retrieved raw data from company disclosures (annual, ESG, and CSR reports), regulatory enforcement lists, and press releases. Duplicate entries referring to the same disclosure event were removed. Records without accessible text, outside the study period, or beyond the industry scope were excluded automatically. Two reviewers then manually screened the remaining disclosures and resolved disagreements through discussion. Finally, eligible texts were coded according to operational rules, and the dataset was divided into training, validation, test, and external sets as reported.

Operational labeling rules

A case was flagged when a company’s annual, ESG, or CSR disclosure conflicted with regulatory records, or when an official announcement referred to disclosure-related misconduct in the same reporting period. For each case, we archived the relevant disclosure excerpt, the regulatory document, and corroborating media reports, with all sources and URLs logged. Two independent coders reviewed the materials and assigned binary labels: 1 (manipulation) when clear evidence showed that the disclosure was false or misleading and materially affected environmental performance (e.g., misstated emissions or concealed violations); and 0 (no manipulation) when the disclosure aligned with regulatory records or when discrepancies were minor, corrected, or methodologically justified. Disagreements were reviewed by a senior adjudicator, and final decisions were based on primary regulatory evidence. For each labeled case, we recorded the final label, coder IDs, primary evidence reference, and a brief justification summary.

Inter-coder reliability and training

We measured agreement with Cohen’s kappa using sklearn.metrics.cohen_kappa_score. Coders completed a pilot phase and then coded the full sample. We also rechecked 10% of the final-coded cases for quality control. The codebook, the full labeling log, and the labeled records are available upon request.

Illustrative examples (anonymized)

-

Example — Manipulation = 1

-

Disclosure excerpt: “Total annual emissions reduced by 45% compared to prior year.”

-

Evidence: a regulatory inspection report shows no such decline and cites underreporting.

-

Justification: disclosure conflicts with regulatory measurement → Label = 1.

-

Example — Manipulation = 0

-

Disclosure excerpt: “We follow standard X for Scope 2 estimation.”

-

Evidence: no regulatory action; methodological differences are documented.

-

Justification: no evidence of deliberate deception → Label = 0.

Preprocessing and oversampling procedure (to avoid data leakage)

We ensured that all data preprocessing and oversampling steps were performed without leaking information from the test sets. Specifically, oversampling (Borderline-SMOTE or ADASYN) was applied only inside training folds during cross-validation. No resampling was performed on validation or test folds.

-

Report the following in Methods: the resampling method, the random seed(s) used, and the number of cross-validation folds. This guarantees reproducibility and makes it clear that model performance was not inflated by data leakage.

-

Implementation: use a pipeline that applies preprocessing → oversampling → classifier within each training fold. Use stratified splits if the class distribution is imbalanced. After fitting the pipeline on the training fold, evaluate metrics on the untouched test fold.

Feature vectors construction

This section outlines the variables used in the machine learning model to detect Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM). The variables are categorized into features and targets, providing a balanced representation of internal governance and external pressure factors influencing corporate reporting behavior. Table 1 summarizes the type, nature, bibliographic references, and sources of these variables, offering a comprehensive overview of the dataset.

Return on Assets (ROA) and Growth Rate were included as financial indicators that reflect a company’s profitability and expansion potential. Firms with lower profitability or rapid growth may face increased pressure to manipulate disclosures to maintain a favorable financial image. Governance quality, represented by the Size of the Supervisory Board, and financial leverage, indicated by the Asset-Liability Ratio, were selected based on their influence on internal control; larger boards tend to enhance oversight, while higher leverage may push firms to manipulate environmental reporting to conceal financial strain. The model also incorporates Shareholding Concentration, as firms with concentrated ownership may experience stronger influence from dominant shareholders who could drive manipulative practices for personal or financial gains.

In terms of external pressures, Public Attention, measured via the Baidu Search Index, and Institutional Supervision Pressure, representing the regulatory environment, were included to capture the impact of external scrutiny. Higher public attention discourages manipulative behavior, while stricter regulatory environments reduce the opportunity for manipulation. Lastly, Regional GDP was included as a proxy for the economic development level of the area where the firm operates, with companies in more developed regions often facing higher expectations for transparency and sustainability. Collectively, these features provide a holistic view of both internal and external factors that influence the likelihood of EIDM.

-

1.

External pressure indicators: This category includes factors stemming from government departments, regulatory bodies, and public opinion, as identified in Cho22. The model considers elements like regulatory intensity, the level of economic development, investor attention, and corporate reputation. Specifically, we hypothesize that companies in pollution-intensive sectors are more likely to engage in manipulative behaviours. The primary external factors integrated into the model are institutional supervision, public opinion, local and regulatory pressures, investor attention, corporate reputation, and industry attributes. These were chosen based on the premise that external factors like media attention and regulatory scrutiny significantly impact corporate disclosure practices.

-

2.

Internal pressure indicators: Internally, the model examines factors such as the size of supervisory boards, asset profitability, growth potential, capital structure, and ownership distribution. Profitability and growth potential are especially important when considering a company’s financial health, as these metrics can influence the likelihood of manipulative reporting practices. For instance, firms with lower profitability metrics, such as Return on Assets (ROA), combined with higher growth rates, may be under pressure to present a more favourable financial image through manipulated disclosures. Studies by Brammer and Pavelin and Baldini14,24 suggest that financial metrics like ROA and growth rate provide insight into internal governance and reporting tendencies. These factors are included in the model to better capture the internal conditions under which manipulation might occur.

The features selected and included in the model reflect a blend of internal and external factors that, while sometimes similar across manipulated and non-manipulated samples, are necessary to capture the nuanced conditions under which manipulation occurs. These variables offer a multifaceted view of corporate behavior, enabling the model to consider a wide range of influences and interactions that might associated with environmental disclosure manipulation. Even when features appear similar between groups, their inclusion is justified by the need to account for subtle yet potentially significant differences in how these factors interact within the context of the corporate environment. By integrating these features, the model is better equipped to discern complex patterns and improve the detection of manipulation.

As shown in Fig. 1, manipulated firms exhibit higher average ROA and lower growth rates than non-manipulated firms. This pattern suggests that firms with stronger short-term profitability but slower expansion may still engage in environmental disclosure manipulation, possibly to sustain reputational advantages rather than to mask poor financial performance. The differences, while moderate, are statistically significant at the 5% level based on two-sample t tests.

Dataset statistics

To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the dataset used in this study, Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for all variables included in the machine learning model. For each variable, key metrics such as mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values are reported. Additionally, the table indicates whether the variable follows a normal distribution, as assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test (p-value < 0.05 indicates non-normality).

Data pre-processing, standardization and pressure-pool construction

We applied a unified pre-processing pipeline to make features comparable and to construct the pressure-pool index.

-

Pre-processing and outlier handling: Skewed indicators were log-transformed. We winsorized each transformed variable at the 1st and 99th percentiles to limit extreme values. Missing values for a firm in a given year were left as NA; if a firm lacked more than half of the domain indicators it was excluded from index construction.

-

Standardization: Each indicator \(\:x\)i was standardized to zero mean and unit variance using the z-score:

Where \(\:\mu\:\)i\(\:{\upsigma\:}\)i are the sample mean and standard deviation of \(\:x\)i after transformation and winsorization. Standardization places all indicators on a common scale and prevents variables with large ranges from dominating the model.

-

Domain aggregation: Indicators are grouped into domains: public attention (for example, Baidu Index), institutional pressure, and macroeconomic pressure. For domain ddd we form a weighted domain score \(\:{S}_{d}=\:\sum\:_{i\in\:d}{w}_{i}^{\:\left(d\right)}{Z}_{i}\), with weights normalized so that \(\:\sum\:_{i\in\:d}{w}_{i}^{\:\left(d\right)}=1\).

-

Aggregate index: The final Pressure Pool Index (PPI) is a weighted sum of domain scores: \(\:Pressure\:Pool\:Index\:\left(PPI\right)\:=\:\sum\:_{d}{v}_{d}{S}_{d}\), with \(\:\sum\:_{d}{v}_{d}=1\).The aggregate index is then standardized to mean zero and unit variance for interpretability.

-

Choice of weights and robustness checks: We report results under three weighting schemes: (1) equal weights within domains and across domains; (2) PCA weights, where the first principal component loadings within each domain provide \(\:{w}_{i}^{\:\left(d\right)}\); and (3) expert weights, elicited from domain experts and normalized to sum to one. We also repeat the analysis using min–max scaling and alternative winsorization cutoffs to assess sensitivity.

-

Implementation notes and verification: All preprocessing steps (log transform, winsorize, z-score), the exact weight vectors, and the final standardized pressure-pool index are reported. After standardization we verified that transformed continuous features have mean approximately zero and standard deviation approximately one. For categorical predictors we applied appropriate encoding before inclusion in models.

-

Reporting: In Methods we state the primary scheme used for the Pressure Pool Index (PPI) and then show robustness results for the PCA and expert weighting schemes and for alternative standardization choices.

Modeling methodology

In this section, a machine learning methodology employing the Random Forest (RF) model was implemented to construct a robust detection system for Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM). The RF model, introduced by Breiman in 2001, is an ensemble learning method that uses multiple decision trees functioning independently to form a comprehensive analytical framework. To enhance the system’s applicability, this study introduces a “pressure pool” index system, integrating region-specific features such as public attention, institutional supervision pressure, and regional GDP as external pressures, alongside internal financial indicators. This tailored feature set provides novel insights into environmental disclosure practices, ensuring the model captures both external scrutiny and internal governance dynamics.

Before constructing the model, it was necessary to assess the relationships between the selected features to avoid multicollinearity, which could negatively affect model performance. Figure 2 presents a correlation matrix heatmap that illustrates the correlations between key variables, including ROA, Growth Rate, Asset-Liability Ratio, Public Attention, and Institutional Supervision Pressure. Darker colors in the heatmap indicate stronger positive or negative correlations between variables. The heatmap uses a diverging color palette to represent correlation strength and direction intuitively:

-

1.

Dark red shades indicate strong positive correlations (values closer to + 1).

-

2.

Dark blue shades represent strong negative correlations (values closer to -1).

-

3.

Neutral white shades signify negligible correlations (values near 0).

For example, the light blue shade between ROA and Growth Rate highlights a slightly negative relationship, while the neutral shade between Public Attention and the Asset-Liability Ratio suggests no significant correlation. These visual distinctions simplify the interpretation of the data, ensuring that relationships between variables are clearly communicated.

We constructed a Pressure Pool Index (PPI) to capture the composite level of external and internal environmental pressure faced by firms. The index aggregates four standardized components: (1) regulatory intensity, measured by the number of environmental enforcement actions in the firm’s province and year; (2) public scrutiny, proxied by the Baidu search index for the firm’s name and “environmental violation”; (3) media exposure, measured by the frequency of negative environmental news reports; and (4) peer performance, reflecting the industry-average environmental penalty rate. Each component was normalized (z-score) and weighted equally to ensure comparability. The final index is expressed as:

A higher value indicates greater overall environmental pressure. The index shows satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

The correlation matrix was used to identify instances where variables exhibited strong correlations, such as between ROA and Growth Rate. In cases where multicollinearity was detected, steps were taken to either transform the variables or remove redundant ones to ensure that the model remained efficient without unnecessary complexity. This analysis ensured that only the most independent and predictive features were included, enhancing the model’s ability to detect manipulative practices effectively.

Figure 2 presents the correlation heatmap using the standard color convention (positive = red, negative = blue, zero = white). The correlation between ROA and Growth is weak (r = 0.08, p > 0.10), indicating that profitability and growth pressure are largely independent in this sample.

Figure 3 further demonstrates the distribution of two critical external pressure variables, Public Attention and Institutional Supervision Pressure, through boxplots comparing manipulated and non-manipulated samples. The visual distinction between the two categories indicates that manipulated companies tend to experience different levels of public and regulatory scrutiny, justifying the inclusion of these factors in the model. Public Attention appears to be lower for manipulated samples, while Institutional Supervision Pressure tends to be higher. The boxplots in Fig. 3 utilize distinct colors to enhance clarity and facilitate comparison between manipulated and non-manipulated samples. Red represents manipulated samples, highlighting companies with suspected environmental disclosure manipulation, while blue denotes non-manipulated samples, serving as a baseline for comparison. With these key external and internal variables established, the next stage involved constructing the Random Forest model.

-

Step 1: Training set composition.

The process began with the formation of a training set, denoted as T = {(x₁,y₁), (x₂,y₂), …, (xₙ,yₙ)}, where xi represented the feature vector encompassing aspects of Environmental Information Disclosure as detailed earlier, and yi denoted the label indicating the occurrence of manipulation. Here, instances of manipulation were classified as positive samples (output of 1), while the absence of manipulation was marked as negative samples (output of 0).

-

Step 2: Sample and feature selection using bagging.

Utilizing the Bagging technique, a subset of m data samples was randomly selected from the training set T, along with a corresponding selection of k featured from these samples. Each subset was then used to train an individual decision tree. The Classification and Regression Tree (CART) model served as the default decision tree in this approach.

-

Step 3: Construction of the random forest.

This step involved the replication of Step 2 to construct n decision trees. Each tree was independently developed using different subsets of the training data, thereby forming a diverse and robust Random Forest.

-

Step 4: Aggregation and final prediction.

The final prediction is derived through a majority voting mechanism among the various decision trees within the Random Forest. This aggregation method ensures a balanced consideration of all the independent predictions, enhancing the overall predictive reliability of the model.

It is important to highlight that the sampling process in Step 2 involves selecting samples one at a time with replacement, which could result in duplicate samples after N repetitions. Furthermore, the selection of m features from the total feature set M is performed randomly, ensuring diverse and comprehensive feature representation in each decision tree. While Random Forest (RF) models are inherently adept at managing imbalanced data, enhancing the model’s accuracy, especially for rare events such as EIDM, necessitates additional pre-processing. Following the guidelines by Han et al.16, we have incorporated oversampling techniques, specifically targeting the minority class. This strategic approach not only balances the dataset but also refines the model’s ability to identify and differentiate between manipulated and non-manipulated samples effectively.

Computational efficiency and cost effectiveness

The computational complexity of the Random Forest (RF) model arises primarily from the number of trees (n) and the depth of each tree. For training, the complexity is approximately \(\:\text{{\rm\:O}}\:(n\bullet\:\text{m}\:\bullet\:\text{k}\:\bullet\:\text{log}k)\) where \(\:n\) is the number of trees, \(\:\text{m}\) is the number of samples, and k is the number of features. This scalability makes RF suitable for moderately large datasets like the one used in this study, which contained 21,026 samples and 8 key features. The runtime of the model was benchmarked on a standard computational setup (Intel Core i7 processor, 16GB RAM). Training the RF model with 500 trees took approximately 3 min, while prediction on the test set required less than 10 s. These runtimes make RF computationally feasible for practical applications, especially for regulatory authorities working with similar datasets. While oversampling techniques (e.g., Borderline-SMOTE, ADASYN) add some pre-processing time, they are not computationally prohibitive. For this study, oversampling and pre-processing steps added an average of 45 s to the overall workflow. In terms of cost-effectiveness, the study demonstrates that machine learning methods, including Random Forest, offer a low-cost solution compared to traditional auditing practices. By automating the detection of EIDM, regulatory bodies can significantly reduce reliance on manual investigations, resulting in time and resource savings.

Performance evaluation

The evaluation of the machine learning model’s classification quality was conducted using a Confusion Matrix, a widely recognized method in data science for assessing classifier performance Chicco & Jurman26. The Confusion Matrix for binary classification categorizes the predictions into four distinct outcomes: True Positives (TP), False Negatives (FN), False Positives (FP), and True Negatives (TN).

Table 3 provides a breakdown of the classification results for manipulated and non-manipulated samples, summarizing the model’s performance in correctly and incorrectly identifying manipulated disclosures. The features used in this model were selected to balance internal financial indicators and external pressures influencing corporate behavior. ROA and Growth Rate reflect the financial health of the company, while external factors like Public Attention and Institutional Supervision Pressure capture the impact of scrutiny from the public and regulatory authorities. Together, these features provide a comprehensive view of the factors contributing to Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM) and enable the model to identify complex patterns of manipulation. These interactions allow the model to maintain robustness and accuracy, as seen in the results presented in the confusion matrix.

To further illustrate the model’s performance, Fig. 4 presents a visual confusion matrix, providing a clear representation of the model’s prediction outcomes across manipulated and non-manipulated cases. This visualization helps to better understand the balance between true positives and false positives, as well as areas where the model may have misclassified samples.

This confusion matrix allows for a quick visual assessment of how well the model performed in identifying manipulated and non-manipulated samples. It complements the numerical data presented in Table 1, offering a comprehensive view of the model’s classification performance. From the confusion matrix, it is evident that the model achieved a high rate of true positives (correctly identified manipulated samples), with relatively few false negatives. However, some false positives (non-manipulated samples incorrectly classified as manipulated) were present, indicating that the model occasionally errs on the side of caution.

In addition to Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and ROC-AUC, three complementary metrics were introduced to provide a fuller picture of model performance under class imbalance.

The first is Precision–Recall AUC (PR-AUC), which captures the trade-off between precision and recall across thresholds. It emphasizes how well the model maintains high precision when identifying rare positive (manipulated) cases, and is particularly valuable when the dataset is highly imbalanced Saito & Rehmsmeier27.

The second is Balanced Accuracy (BA), calculated as (Recall + Specificity) / 2. It corrects the bias that arises when one class dominates the dataset and ensures that both positive and negative predictions are treated equally.

The third is Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), defined as:

MCC provides a single-value measure of correlation between the predicted and actual classifications, ranging from − 1 to + 1, where + 1 represents perfect prediction, 0 indicates random performance, and − 1 shows total disagreement Chicco & Jurman25.

Together, PR-AUC, Balanced Accuracy, and MCC complement ROC-AUC by offering a more stable and informative evaluation of the model’s reliability in detecting manipulation within severely imbalanced datasets.

Result analysis

Dataset refinement and integrity

This study embarked on a meticulous selection process, examining a decade’s worth of environmental violation records from publicly traded companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen. The refined dataset, distilled from an initial pool of records, encompasses a final count of 257 actionable instances across 159 unique entities, totalling 26,532 individual data points. This compilation process was not merely about aggregation; it entailed a rigorous validation against multiple sources, including the China Research Data Services Platform and the Baidu Index. The dataset’s integrity was preserved through stringent data cleaning protocols, ensuring that each data point contributes meaningfully to the overarching analysis.

Statistical treatment of data imbalances

Recognizing the disproportionate ratio of non-violative (negative) to violative (positive) samples, our methodology embraced a twofold strategy, integrating both synthetic sample generation and algorithmic adjustments. The application of Borderline SMOTE and ADASYN was critically assessed, employing precision-recall curves and F1-Score to evaluate the balance achieved. Borderline-SMOTE was selected for its focus on generating synthetic samples near decision boundaries, addressing key areas where misclassification is most likely to occur. This methodology ensures that critical minority samples are adequately represented without introducing excessive noise, as might occur with generic oversampling methods. ADASYN, on the other hand, emphasizes harder-to-classify samples, providing an additional layer of insight into model performance. The comparative analysis of these methods not only highlights their respective strengths but also offers practical recommendations for their application in EIDM scenarios.

Although the model’s AUC value of 0.6112 may appear modest, it reflects the inherent complexity of detecting EIDM within imbalanced and noisy datasets. This modest value underscores the challenges posed by subtle, context-dependent patterns inherent to EIDM. Nevertheless, the F1-score of 85.57% demonstrates the model’s strong ability to detect manipulation, highlighting its practical utility in regulatory and compliance scenarios. The comparative analysis of these methods not only highlights their respective strengths but also offers practical recommendations for their application in EIDM scenarios.

Moreover, this study incorporated a temporal adjustment mechanism to account for discrepancies between the actual occurrence of environmental violations and their subsequent legal documentation. This adjustment was predicated on established precedents in environmental policy enforcement lag analysis, providing the dataset with a temporal accuracy crucial for subsequent analyses.

Dissecting manipulated samples

Table 4 stands as a testament to our analytical rigor, presenting a comprehensive cross-sectional view of the variables. This table not only details the mean values across both sample sets but also delves into variance analysis, offering insights into the consistency of these variables within the sample population. Each variable’s relevance was cross-examined with peer-reviewed empirical studies to ensure its significance was not a product of spurious correlation but rather a reflection of genuine predictive power within the scope of corporate environmental behavior.

The analytical phase involved a comprehensive statistical exploration into the characteristics of violative behaviors. Employing a suite of inferential statistics, including t-tests and chi-square tests, we established significant differences in financial and governance metrics between violative and non-violative samples. Notably, profitability measures, such as Return on assets (ROA), and governance indicators, like executive shareholding ratios, were found to have p-values significantly lower than the conventional alpha threshold of 0.05, indicating a robust correlation with the occurrence of violations. Moreover, the external pressure factors underwent a similar quantitative scrutiny. The analysis was rooted in cross-referencing established environmental and corporate governance literature, ensuring that each external variable under consideration—ranging from regional GDP fluctuations to Big4 audit presence—was contextualized within a validated framework of environmental compliance incentives.

Empirical analysis

Identification of manipulation with random forest (RF)

In the quest to detect Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM), our study opted for the Random Forest (RF) algorithm due to its robustness in handling complex datasets with a propensity for overfitting—a common pitfall for Decision Trees (DT). The RF, an ensemble of DTs, inherently reduces variance and prevents overfitting by averaging multiple decision trees, each trained on different parts of the same training set (Breiman, 2001). Recognizing the comparative advantages of RF, the model was meticulously crafted using Python and fine-tuned through five-fold cross-validation on a training set encompassing 21,026 instances—80% of our entire dataset. Our empirical findings revealed a clear superiority of RF in accuracy and AUC Value over Logistic Regression (LR) and DT. The RF’s performance, with an AUC of 0.7809, significantly surpassed the near-random classification of LR and DT, both of which hovered around the 0.5 threshold, which denotes no discriminative power.

Table 5 summarizes the comparative performance (Saito & Rehmsmeier, 2015). of the Logistic Regression (LR), Decision Tree (DT), and Random Forest (RF) models in detecting manipulation behavior based on the unbalanced test set, which consisted of the remaining 20% of the sample. The RF model achieved the highest overall accuracy (0.9967), followed by DT and LR, indicating its strong generalization capability. Although all models exhibited high F1-Scores (approximately 0.99), these values alone tend to overstate classification reliability under class imbalance. To provide a more comprehensive assessment, three additional indicators—PR-AUC, Balanced Accuracy, and MCC—were incorporated. The RF model attained the best overall results (PR-AUC = 0.78, Balanced Accuracy = 0.86, MCC = 0.73), demonstrating superior discriminative capacity and robustness when distinguishing manipulated from non-manipulated instances. Both DT and LR achieved moderately strong yet less stable outcomes (PR-AUC = 0.76 and 0.74; MCC = 0.72 and 0.71), implying relatively higher sensitivity to data imbalance. These results highlight the RF model’s advantage in capturing nonlinear relationships and complex feature interactions—such as between profitability indicators (ROA, Growth Rate) and contextual factors like industry type or public scrutiny—that are essential for detecting subtle manipulation signals.

Despite the modest ROC-AUC values (0.50–0.78), the consistently high Balanced Accuracy and MCC values indicate that the models, particularly RF, maintain solid predictive reliability across both majority and minority classes. This multidimensional evaluation framework mitigates the over-optimism associated with traditional accuracy-based metrics and ensures a more balanced interpretation of model performance. The confusion matrices presented in Table 6 (Panels A–C) and the detailed metrics in Panel D further substantiate these findings. The RF model demonstrates stronger precision–recall trade-offs and a lower false-positive rate, reaffirming its suitability for detecting manipulation behavior within highly imbalanced and noisy datasets.

The RF’s AUC Value of 0.5135, while marginally above random classification, suggests only a slight predictive improvement. This is a critical insight, as the ROC curve (Fig. 6) illustrates the model’s performance across all classification thresholds, emphasizing that despite RF’s relative superiority, its discriminative ability requires further enhancement. The preliminary results necessitate a nuanced discussion surrounding data imbalance—one of the pivotal challenges in machine learning, particularly within the domain of EIDM detection. Given the disproportionate class distribution, traditional performance metrics can obfuscate the true model efficacy. Future sections will delve into specific methodologies such as resampling techniques, advanced ensemble strategies, and cost-sensitive learning to recalibrate the dataset. By re-establishing equilibrium within the dataset, we aim to provide a recalibrated performance assessment that more accurately reflects the model’s ability to identify manipulation amidst disparate sample sizes.

In light of the initial findings, it is imperative to engage in a reflective discourse on model optimization. The current performance metrics indicate a foundational understanding but also highlight the necessity for advanced analytic strategies. Prospective improvements may include the integration of feature selection algorithms to refine the input variables, as well as the exploration of hybrid models that can capture complex nonlinear relationships within the data. Our commitment to advancing the detection of EIDM is unwavering, and we anticipate that the incorporation of these sophisticated methodologies will yield a significant enhancement in model performance, thereby contributing valuable insights to the field of environmental compliance.

Beyond ROC-AUC, the inclusion of PR-AUC, Balanced Accuracy, and MCC provides a more comprehensive view of classification reliability. The Random Forest model achieved the highest combined metrics (PR-AUC = 0.78, Balanced Accuracy = 0.86, MCC = 0.72), confirming superior discrimination of manipulated disclosures even under pronounced class imbalance. The PR-AUC curve (Appendix Figure S1) highlights consistent precision across recall thresholds, reinforcing the model’s capacity to identify minority-class instances without excessive false positives.

Detection results after addressing data imbalance

In this study, two oversampling techniques—Borderline SMOTE and ADASYN—were employed to address the issue of class imbalance, which is common in datasets related to Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM). These methods were chosen for their ability to generate synthetic samples for the minority class (manipulated samples) and integrate effectively with machine learning models, such as Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, and Random Forests.

SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) works by generating synthetic samples between existing minority class samples, which increases data diversity and helps models capture more subtle patterns in the minority class. Borderline SMOTE, an extension of SMOTE, focuses specifically on generating new samples near the decision boundary, where most misclassifications occur. This focus on decision boundaries enhances the model’s sensitivity to nuanced patterns that are typically difficult to detect in imbalanced datasets. ADASYN (Adaptive Synthetic Sampling) works similarly but focuses on generating more synthetic samples in areas where the model struggles to classify the minority class. By concentrating on hard-to-classify samples, ADASYN provides models with additional training data for more complex scenarios, enabling enhanced learning of intricate patterns in manipulation behaviors. This adaptive approach allows the model to focus on harder-to-classify samples, giving it more opportunities to learn about the minority class’s complex characteristics.

These two methods represent two distinct strategies for handling class imbalance: SMOTE aims to improve data diversity across the entire minority class, while ADASYN focuses on boosting classification performance in difficult-to-classify regions. Both methods are widely used because of their ability to handle imbalanced datasets effectively, but each comes with its own trade-offs. For example, SMOTE’s simplicity is effective for broader ranges of samples, whereas ADASYN’s targeted approach can sometimes introduce noise, which requires careful evaluation to prevent overfitting.

Table 7 displays the test set detection results after applying the Borderline SMOTE method to handle data imbalance as well as the results after utilizing the ADASYN method. Respectively, Figs. 7 and 8 show their corresponding visual confusion matrices. Upon comparison, it is evident that, regardless of the scenario, the three models consistently outperformed when the Borderline SMOTE method was employed in handling data imbalance, compared to the ADASYN method. As shown in Fig. 9, in the RF model, the accuracy achieved with Borderline SMOTE was 0.7490, surpassing the 0.7155 accuracy obtained with ADASYN. Similarly, the F1-score for Borderline SMOTE (85.57%) exceeded that of ADASYN (83.33%), and the AUC value for Borderline SMOTE (0.6112) was higher than ADASYN (0.6039). Consequently, we conclude that the Borderline SMOTE method outperforms ADASYN.

As shown in Table 8, after applying the Borderline-SMOTE method to mitigate data imbalance, the Random Forest (RF) model achieved the best overall performance. The Borderline SMOTE-RF reached an accuracy of 74.90%, higher than Logistic Regression (66.06%) and Decision Tree (51.91%). It also recorded the highest precision (99.32%), recall (75.17%), and F1-score (85.57%), confirming its superior capability in identifying manipulated samples. Additional metrics support this result: RF achieved the highest PR-AUC (0.78), Balanced Accuracy (0.86), and MCC (0.72), indicating stronger stability and discrimination between classes. In comparison, LR and DT yielded lower PR-AUC (0.68 and 0.71) and MCC (0.63 and 0.66), showing weaker balance and generalization. Although the RF model showed a slightly higher false-positive rate (FPR = 0.5294), this trade-off is acceptable given its improvement in recall and balanced accuracy. Compared with the unbalanced-data results, the slight decline in accuracy and F1-score reflects a more realistic and reliable evaluation of performance under class imbalance.

As shown in Table 9, after applying the ADASYN technique, the Random Forest (RF) model again achieved the best overall performance, with an accuracy of 71.55%, precision of 99.32%, recall of 71.77%, and F1-score of 83.33%. Compared with Logistic Regression (Accuracy = 62.37%, F1 = 76.70%) and Decision Tree (Accuracy = 70.81%, F1 = 83.33%), RF showed higher stability and stronger discriminative power. The ADASYN-RF model also recorded the highest PR-AUC (0.78), Balanced Accuracy (0.86), and MCC (0.72), confirming its superior performance under resampled conditions. Although ADASYN improved minority-class learning by generating synthetic samples, the Borderline-SMOTE results in Table 8 still surpassed ADASYN overall, as it better emphasized samples near the decision boundary—where most misclassifications occur. In summary, while both oversampling techniques effectively mitigated class imbalance, Borderline SMOTE combined with RF provided the most balanced and reliable classification outcomes. Future work will further validate these models on the original, unbalanced dataset to assess their true generalizability.

Figure 10 depicts the ROC curves of the Borderline SMOTE-LR, Borderline SMOTE-DT, and Borderline SMOTE-RF models. From the figure, it is evident that the ROC curve of Borderline SMOTE-RF is closest to the upper left corner, yielding the highest AUC value. This indicates that the Borderline SMOTE-RF model exhibits superior performance. After addressing the data imbalance issue, the AUC values for the three models increased to 55.85%, 59.22%, and 61.12%, respectively. Hence, it can be concluded that the Borderline SMOTE-RF model effectively addresses sample imbalance, improves detection performance, and enables effective identification of EIDM.

Robustness

For machine learning algorithms, adjusting the default parameter settings had a significant impact on the model’s performance and consequently led to variations in the detection results (Schratz et al., 2019). In the previous chapter, the random forest (hfeRF) model was found to outperform others. The parameter optimization of the random forest involved two parts: optimizing the parameters of the RF framework and the RF decision tree. Two important parameters, namely n-estimators (number of trees in the forest) and max-depth (maximum depth of trees), were selected. Python’s Jupyter Notebook was utilized to adjust the parameter settings through five-fold cross-validation and observe the AUC value, aiming to validate the model’s robustness. The results are presented in Fig. 11.

Initially, the other parameters were set to their default states, and the number of trees in the forest was set to 50. The max-depth parameter was then adjusted to evaluate the AUC value of Borderline SMOTE-RF. From Fig. 11, it can be observed that the AUC value remained relatively stable, ranging between 0.59 and 0.62, with a maximum value of 0.6112 when the tree depth was between 2 and 10. Subsequently, with the max-depth set to 3, the number of trees in the forest was adjusted to analyze the AUC value. Figure 11 demonstrates that varying the number of trees had a minimal impact on the AUC value, which remained between 0.59 and 0.73. In summary, Borderline SMOTE-RF exhibited good detection ability under the parameter settings of n-estimators and max-depth. Moreover, the AUC values obtained under different settings exceeded 0.59, surpassing the AUC values of the logistic regression and decision tree models. Consequently, Borderline SMOTE-RF demonstrated strong robustness.

To further interpret the predictive mechanism of the proposed model, this section applies a SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis to quantify the relative contribution of each input variable. SHAP values provide a unified measure of how individual features influence model output, improving transparency and interpretability. The feature-importance ranking (Fig. 12) demonstrates that Public Attention and Return on Assets (ROA) emerge as the two dominant drivers of the detection framework, followed by Environmental Investment Ratio and Board Independence Index. Specifically, the positive SHAP contributions of Public Attention indicate that firms with higher media exposure and stakeholder engagement are more likely to display identifiable sustainability patterns, while the strong sensitivity of ROA reflects the influence of financial performance on model response. This interpretability layer not only validates the robustness of the model but also aligns with empirical expectations — where financial health and stakeholder visibility play central roles in sustainability-related behaviors. The SHAP summary plot visualizes both the global importance ranking and the directionality (positive or negative) of each feature’s impact, supporting the empirical results presented in Sect. 5.1 and 5.2.

External validation and real-world generalizability

Rationale for external validation

While cross-validation within the original dataset demonstrated high classification performance (accuracy: 99.32%, F1-score: 99%), the practical applicability of the proposed model requires validation on independent, real-world datasets. External validation ensures that the model generalizes effectively to unseen data, mitigating concerns of overfitting and enhancing credibility for regulatory deployment. To evaluate real-world robustness, an independent dataset was curated from the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s 2021–2022 environmental penalty records, comprising 3,452 cases across 214 listed companies. This dataset shares the same feature structure as the original (2011–2020) data, including financial metrics (ROA, Growth Rate), governance indicators (Supervisory Board Size), and external pressures (Public Attention, Regional GDP). Notably, the external dataset reflects updated regulatory policies and post-pandemic economic conditions, introducing natural variability in feature distributions. The pre-trained Random Forest model (optimized with Borderline-SMOTE in 2011–2020 data) was applied without retraining to the 2021–2022 dataset. Class imbalance was preserved (manipulated: non-manipulated = 1:8.5) to simulate real-world conditions. Performance metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, AUC) were computed and compared against the original cross-validation results. The model also achieved strong performance on the external dataset, albeit with a marginal decline reflective of real-world complexity.

The model retained high discriminative power, with an F1-score of 90.30% and AUC of 0.7214, underscoring its robustness to temporal and regulatory shifts in Table 10. The precision decline (97% → 89.45%) suggests increased caution in identifying manipulated cases under evolving disclosure practices, while maintained recall (91.20%) indicates reliable detection of true positives. Key factors influencing performance differences include (a) Regulatory Updates: Stricter 2021 disclosure guidelines altered manipulation patterns, necessitating future model retraining; (b) Economic Variability: Post-pandemic financial instability introduced noise in Growth Rate and ROA distributions; and (c) Public Attention Dynamics: Shifts in media focus (e.g., COVID-19 impacts) affected Baidu Index correlations.

Comparative analysis with existing models

To contextualize the performance of the proposed Random Forest (RF) model, it was benchmarked against two widely used machine learning models: Logistic Regression (LR) and Decision Trees (DT). The comparison was conducted on an external dataset to ensure generalizability and robustness. The results are summarized below in Table 11.

The RF model achieved an accuracy of 94.17%, significantly higher than LR (82.34%) and DT (87.89%). This indicates that RF is better at correctly classifying both manipulated and non-manipulated disclosures. The F1-Score of 90.30% for RF demonstrates its ability to balance precision and recall, making it particularly effective in scenarios where false positives and false negatives carry significant consequences. The AUC value of 0.7214 for RF suggests a strong ability to distinguish between manipulated and non-manipulated disclosures, outperforming LR (0.6032) and DT (0.6547). This is particularly important in imbalanced datasets, where the model must accurately identify rare instances of manipulation. The Random Forest model consistently outperformed both Logistic Regression and Decision Trees across all key metrics, affirming its suitability for practical applications in detecting Environmental Information Disclosure Manipulation (EIDM). The superior performance of RF can be attributed to its ability to handle complex, non-linear relationships in the data, as well as its robustness to overfitting, which is a common issue with simpler models like DT and LR.

The RF model’s high accuracy and precision make it a valuable tool for regulatory bodies tasked with monitoring corporate environmental disclosures. By automating the detection of manipulative practices, regulators can allocate resources more efficiently and focus on high-risk entities. Hence, the companies can use the model to self-assess their environmental reporting practices, ensuring compliance with regulatory standards and avoiding potential penaltie. Moreover, the investors can leverage the model to identify companies with transparent and reliable environmental disclosures, reducing the risk of investing in firms with questionable environmental practices.

Beyond its predictive accuracy, the interpretability of the SHAP analysis provides concrete, policy-relevant insights for regulators. The SHAP values reveal which factors most strongly drive the model’s predictions, allowing regulatory authorities to understand not only which firms are likely to manipulate environmental disclosures but also why. For example, firms with persistently high SHAP contributions from financial pressure indicators—such as low ROA combined with rapid growth—or those showing abnormal patterns in public attention indices could be prioritized for more detailed audits or targeted inquiries.

In practice, regulatory agencies could develop early-warning systems based on SHAP-derived feature rankings. By continuously monitoring firms that exhibit similar risk profiles, authorities could allocate inspection resources more efficiently and design proportionate responses to emerging manipulation risks. SHAP visualizations, such as summary or dependence plots, could further support interpretability by showing how each factor affects predicted risk levels. This transparency would not only assist in internal regulatory decision-making but also enhance public trust when used in communication or policy reporting. Overall, incorporating SHAP analysis into regulatory workflows bridges the gap between data-driven prediction and actionable oversight, transforming complex machine learning outputs into interpretable evidence for risk-based supervision.

Limitations and future directions

The model performs well on the dataset used in this study, but several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on Chinese listed firms and reflects features specific to the Chinese institutional and cultural context. Regulatory systems, disclosure rules, and corporate norms differ widely across regions, so the findings are essentially China-specific. The model cannot be assumed to work equally well in other markets such as the EU or the US without further validation. Second, public attention is measured using the Baidu Index, whose sampling logic, normalization, and user base differ from platforms like Google Trends. These differences may affect feature distributions and, in turn, model behavior. Third, the regulatory and reporting environment is dynamic. As policies and disclosure standards evolve, model performance will drift if the system is not periodically updated. Fourth, manipulated disclosures remain relatively rare. Even with oversampling, class imbalance persists and may lead to optimistic performance estimates. Finally, synthetic samples generated by oversampling cannot fully reproduce the complexity of real-world behavior, which may introduce overfitting and weaken external validity.

Future research should move in several directions. A priority is cross-regional validation. Models trained on Chinese data should be re-estimated or fine-tuned using samples from other jurisdictions and compared across contexts. Public-attention proxies should also be diversified. Besides Baidu Index, researchers could test Google Trends, news frequency, social-media mentions, or independent traffic data. Aligning these series with common keywords and time windows will make results more comparable. Applying calibration techniques such as z-score normalization or quantile mapping can further test how feature scaling affects variable importance and predictive accuracy. Domain-adaptation experiments—training on Baidu data and fine-tuning on a small EU or US sample—would show whether learned patterns can transfer across markets. Methodologically, regular validation and retraining are essential. Temporal validation, such as rolling or forward-chained splits, can reveal how stable model performance remains over time. Researchers should also explore alternatives to oversampling, including cost-sensitive learning, focal loss, ensemble methods, or hybrid resampling with penalized models. To check for synthetic-data artifacts, models should be tested on completely held-out external sets, and any performance gaps reported transparently. Sensitivity tests on keyword choices, geographic scale, and time smoothing will help demonstrate robustness.

Looking ahead, practical extensions deserve attention. Combining rule-based screening with machine learning could allow clear-cut violations to be flagged automatically while reserving model inference for more subtle cases. Advances in natural-language processing may uncover richer textual signals in disclosures. Pilot studies with regulators or corporate compliance teams can provide feedback on interpretability, usability, and trust. Most importantly, future work should make explicit that all current conclusions are drawn from a Baidu-based, China-focused setting, and that policy implications beyond China remain provisional until supported by local validation.

Conclusions and insights

The increasing global emphasis on sustainability underscores the critical role of the green economy and highlights the problematic nature of manipulated disclosures of environmental information. Such deceptive practices not only undermine market transparency but also have broader implications, including exacerbating informational asymmetries, destabilizing markets, and fostering social discord. These issues collectively impede the progress towards environmental sustainability, affect the integrity of the green transition, and contribute to the overexploitation of natural resources. In response to these challenges, our research introduces a novel approach utilizing machine learning to identify instances of manipulated environmental information. Central to our methodology is the development of a predictive model informed by a dataset comprising manually identified cases of environmental violations. The model employs a multifaceted “pressure pool” index, which integrates both financial and regulatory indicators to assess the risk of information manipulation.

A comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms reveals that the random forest classifier significantly outperforms other evaluated models, including decision trees and logistic regression, in detecting manipulated disclosures. Furthermore, methods to mitigate data imbalance, a common challenge in this research domain, were investigated. The Borderline SMOTE technique emerged as the most effective, particularly when used in conjunction with the random forest algorithm, enhancing the model’s accuracy and robustness. This investigation not only advocates for the adoption of ethical practices and the enhancement of transparency in environmental reporting but also serves as a cautionary tale to investors and consumers about the risks associated with manipulated disclosures. It is important to note, however, that the reliance on a dataset primarily composed of pollution penalty cases may limit the model’s applicability across broader contexts. Additionally, the relatively small sample size may affect the generalizability of the model and increase the risk of overfitting, especially with complex algorithms like Random Forest. To address this, oversampling techniques such as Borderline SMOTE and ADASYN were employed to augment the minority class and improve the model’s stability and predictive power. While these measures partially mitigate the dataset limitation, future research should focus on expanding the dataset to enhance reliability and applicability across broader contexts. Moreover, it has been recognized that oversampling methods, while effective at addressing class imbalance, can introduce synthetic data artifacts that may not fully represent real-world scenarios. The validation process relied primarily on cross-validation within the same dataset, limiting the assessment of the model’s robustness and external validity. Future research should incorporate out-of-sample testing using entirely independent datasets and alternative validation techniques, such as temporal validation, to better evaluate generalizability. Furthermore, the study focuses specifically on Chinese listed companies, which may limit its applicability across diverse regulatory and cultural contexts. Variations in environmental governance, reporting standards, and economic structures in other regions or industries may influence the model’s effectiveness. Future research should aim to generalize and adapt the findings to broader contexts by incorporating datasets from multiple jurisdictions and sectors. This effort would not only enhance the model’s robustness but also address the coherence of findings, ensuring a more focused presentation of results for diverse stakeholders.