Abstract

This study presents a multi-temporal geospatial modeling approach to identify and map land degradation and desertification hotspots in the aeolian-dominated semi-arid regions of Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal Mandals of Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Landsat 4–5 TM (1990), Landsat 7 ETM+ (2000, 2010), and Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS (2020) datasets were processed through a standardized workflow comprising radiometric calibration, atmospheric correction, LST retrieval, and spectral index computation. Three diagnostic indices: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Topsoil Grain Size Index (TGSI), and Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI), were integrated with Land Surface Temperature (LST) to quantify vegetation stress, soil texture variability, and salinity conditions. Correlation and regression analyses were employed to evaluate the relationships between LST and index-derived DN values, after which stratified sample extraction and buffer-based zonal statistics were used to delineate surface degradation intensity. A composite hotspot map was generated using mask extraction and cell statistics to merge the most degraded pixel clusters, identifying approximately 192 km2 as severe degradation zones. Model performance was validated using ROC-AUC analysis, yielding an accuracy of 0.851. The study demonstrates a reproducible GIS workflow for semi-arid degradation assessment and provides a robust spatial framework for targeted land restoration, sustainable resource planning, and long-term environmental management in vulnerable dryland ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Land degradation is a major global environmental concern that threatens ecosystem stability, agricultural productivity, and human well-being, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), nearly 25% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface is degraded, impacting the livelihoods of more than 1.5 billion people worldwide1,2,3,4. This degradation manifests through processes such as soil erosion, desertification, deforestation, salinization, and unsustainable land-use practices, necessitating urgent and science-based mitigation measures5,6.

In India, land degradation poses a critical challenge to sustainable development. Approximately 29% of the country’s geographical area is affected by varying degrees of degradation, largely driven by soil erosion, nutrient depletion, salinization, waterlogging, and anthropogenic pressures. These processes not only reduce agricultural productivity but also contribute to biodiversity loss, groundwater depletion, and long-term ecosystem instability7,8,9,10. Therefore, identifying and quantifying degraded areas is essential for implementing effective land management and restoration strategies at both regional and national scales11,12.

The state of Andhra Pradesh, situated in the semi-arid zone of southern India, is particularly vulnerable to land degradation due to erratic rainfall, sparse vegetation cover, and intensive agricultural practices13,14. The Anantapur District, one of the driest regions in the state, experiences severe degradation processes such as aeolian sand migration, topsoil erosion, salinization, and moisture stress15,16,17. Natural factors like wind erosion and climatic variability, combined with anthropogenic influences such as overgrazing, deforestation, and unsustainable cultivation, have accelerated the spread of desert-like conditions in several mandals, notably Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal. Understanding the spatial extent and intensity of these processes is crucial for developing localized and effective land conservation strategies.

This research leverages advanced geospatial techniques combined with four widely recognized spectral indices—the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Topsoil Grain Size Index (TGSI), Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI), and Land Surface Temperature (LST) to identify and characterize land degradation hotspots within the semi-arid landscapes of Andhra Pradesh. NDVI, derived from satellite imagery, reflects vegetation health and density by measuring differences in red and near-infrared reflectance; declining NDVI values indicate vegetation stress and degradation. TGSI quantifies variations in soil texture, which influence soil fertility, moisture retention, and nutrient dynamics, with higher values indicating finer sand dominance or reduced clay content18,19. NDSI detects soil salinity levels using spectral contrasts between visible and shortwave infrared bands, a key indicator of soil degradation in arid zones20,21,22,23. LST, derived from thermal infrared data, represents surface temperature variations that correlate with vegetation cover and land condition. Elevated LST values typically signify vegetation loss and ongoing degradation24,25,26,27. By integrating these four indices across multiple temporal intervals (1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020), this study presents a comprehensive geospatial framework for assessing and mapping land degradation dynamics. The combined use of NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST allows for a multidimensional understanding of vegetation stress, soil texture variability, salinity, and surface temperature key drivers of land degradation in semi-arid regions. This integrated approach facilitates precise delineation of degradation hotspots and provides critical data for formulating sustainable land management policies.

Despite several studies on dryland degradation, limited research has integrated multi-decadal vegetation, soil texture, salinity, and thermal indicators to diagnose aeolian-driven desertification in the semi-arid rain-shadow regions of southern India. This study addresses this gap by employing a unified, multi-index remote sensing framework that combines NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and emissivity-corrected LST with a standardized multi-temporal composite approach and a buffer-based hotspot extraction method. This integrative methodology enables more precise detection of persistent degradation patterns than conventional single-parameter assessments. By applying this framework to the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals, the research provides novel, spatially explicit evidence of long-term land degradation dynamics, offering a much-needed scientific basis for targeted land management, ecosystem restoration, and policy interventions in semi-arid environments.

Study area

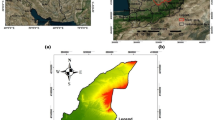

The study focuses on parts of Anantapur District, located in the semi-arid zone of Andhra Pradesh, India. This region is characterized by harsh climatic conditions, including limited and erratic rainfall, high evaporation rates, and poor water availability. Positioned within the rain-shadow region of the Indian Peninsula, Anantapur experiences recurrent droughts, with an average annual rainfall of approximately 550 mm28,29,30. The investigated area, encompassing about 1,050.95 km2, is particularly affected by severe land degradation and desertification processes. The area is dominated by undulating terrain interspersed with extensive fallow lands and ephemeral river systems that remain dry for most of the year31,32. These hydrological and climatic limitations have led to the progressive degradation of soil and vegetation cover. Natural factors such as aridity, sparse vegetation, and wind erosion interact with anthropogenic pressures, including deforestation, overgrazing, and unsustainable agricultural practices to intensify degradation and desertification. Agriculture forms the backbone of the local economy; however, the combination of low rainfall, declining soil fertility, and limited irrigation facilities has led to reduced crop yields and increased vulnerability to drought. The resulting economic instability and resource depletion threaten local livelihoods and exacerbate food insecurity in the region33,34. Addressing these challenges is essential for improving agricultural resilience and ensuring sustainable land and water management. The location map of the study area has been shown in the Fig. 1a.

(a) Location map of the study area with elevation. The map was generated in ArcGIS 10.8 (Esri, USA; https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) using SRTM DEM dataset downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). Elevation values (in meters) were derived from the DEM and visualized through a colour-coded elevation gradient. Administrative boundary shapefiles were obtained from the Survey of India (https://onlinemaps.surveyofindia.gov.in/Digital_Product_Show.aspx). All spatial datasets were processed and cartographically refined within the ArcGIS environment. (b) Impact of southwest monsoon—driven aeolian sand migration resulting in vegetation loss and land degradation in the study area. (c) Encroachment of aeolian sands onto agricultural fallow lands, contributing to land degradation and desertification in the study area. (d) Aeolian sand migration occurring in the rain shadow regions of the study area, illustrating ongoing land degradation. (e) Desertification induced by aeolian sand migration in the study area. (f) Cross-sectional view of sand dunes showing stratified sedimentary layers in the study area. (g) Sand dunes in the study region and their migration toward agricultural fields (Field photographs taken by the authors during ground surveys across the study area).

Aeolian sand migration and desertification in the study area

Aeolian sand migration is a major driver of land degradation and emerging desertification in the semi-arid Anantapur District of Andhra Pradesh, particularly across the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals. The Hagari (Vedavathi) River is the primary source of these aeolian sediments. Historical accounts recorded in the District Gazetteers of Bellary and Anantapur describe an extreme flash flood on 5 May 1851, which deposited extensive riverine sands along the right bank of the Hagari River, forming wide sheets of loose, unconsolidated sediments across the floodplain35,36,37,38,39. These flood-derived deposits represent the earliest documented source of the sand bodies currently reworked by aeolian processes in the region.

Over subsequent decades, these exposed sandy deposits were progressively reworked and redistributed by wind action. The semi-arid climatic setting characterized by sparse vegetation, high evaporation rates, and the district’s positioning in the rain shadow of the Western Ghats further accelerates desiccation and leaves these sediments vulnerable to deflation. During the south-west monsoon, strong seasonal winds mobilize these unconsolidated sands, promoting aeolian transport, dune formation, and lateral sand encroachment onto surrounding agricultural lands and degraded soils40. This continued reactivation of the 1851 flood deposits has significantly contributed to localized desertification, reduced soil fertility, and declining land productivity within the affected mandals41.

Field observations and photographic evidence (Fig. 1b–g) confirm widespread sand accumulation burying croplands, vegetation, and rural infrastructure. Such aeolian sand encroachment alters soil texture, disrupts infiltration and moisture retention, and suppresses vegetation cover key indicators of advancing land degradation. Human pressures, including sand mining, deforestation, overgrazing, and infrastructure expansion, further intensify these processes by destabilizing surface soils and removing natural protective barriers against wind erosion.

The combined effects of historical flood deposition, persistent aeolian reworking, and anthropogenic drivers have produced distinct desertified zones, which have been clearly documented in the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals using both field surveys and previous remote sensing studies42. These studies highlight progressive dune migration and expansion of sandy wastelands over the past three decades.

Materials and methodology

Data sources and acquisition

To identify and map land degradation and desertification hotspots in the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal Mandals of Anantapur District, multi-temporal remote sensing datasets spanning three decades (1990 to 2020) were utilized. All satellite imagery was acquired from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Earth Explorer portal (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). The dataset included Landsat 4–5 Thematic Mapper (TM) imagery for 1990, Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) imagery for 2000 and 2010, and Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager/Thermal Infrared Sensor (OLI/TIRS) imagery for 2020. These multi-temporal datasets provided consistent spectral and thermal information necessary for extracting LST, NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI indicators and for evaluating long-term changes in land degradation patterns across the semi-arid landscape. All images were selected from the dry season (January–March) to minimize the influence of vegetation phenology and cloud cover. The datasets were resampled to a uniform spatial resolution of 30 m and projected to the WGS 84/UTM Zone 43N coordinate system for spatial consistency.

Preprocessing and radiometric corrections

Radiometric calibration and atmospheric correction were performed to ensure spectral comparability among different sensors. Top-of-Atmosphere (TOA) reflectance, spectral radiance, and brightness temperature were calculated using the calibration constants provided in the Landsat metadata (Table 1). The following corrections were applied sequentially:

-

Conversion of Digital Number (DN) to TOA Radiance using rescaling factors;

-

Derivation of TOA Reflectance adjusted for solar angle;

-

Estimation of Brightness Temperature (BT) from the thermal band;

-

Conversion of BT to Celsius and computation of Land Surface Emissivity (ε) based on NDVI-derived vegetation proportions; and

-

Land Surface Temperature (LST) estimation by integrating BT and ε.

These steps were executed using ArcGIS 10.8 and ENVI 5.6 software packages.

Explanation of equations and processing steps

All Landsat datasets underwent a uniform preprocessing workflow consisting of atmospheric correction, radiometric calibration, and thermal parameter derivation based on the equations provided in Table 1. Digital Number (DN) values were converted to Top-of-Atmosphere (TOA) radiance (Eq. 1) and reflectance (Eq. 2), followed by solar-angle correction (Eq. 3) to ensure inter-scene comparability.

Thermal infrared (TIR) data were processed to obtain Brightness Temperature (BT) using sensor-specific calibration constants K1 and K2 (Eq. 4). Land Surface Emissivity (ε) was estimated from NDVI-derived fractional vegetation cover (Eq. 5). These parameters were integrated using the emissivity-corrected Planck function to retrieve Land Surface Temperature (LST) (Eq. 6). To minimize seasonal and inter-annual variability, standardized LST values from 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 were averaged to generate the resultant long-term LST layer (Eq. 7).

This workflow ensures radiometric consistency, accurate surface temperature retrieval, and quantitative comparability across multi-decadal imagery.

Derivation of spectral indices

Four key spectral indices: NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST were selected to characterize the major biophysical processes associated with land degradation: vegetation condition, soil texture, salinity, and surface heating.

NDVI (Eq. 8) was computed to represent vegetation vigor and biomass distribution. Fractional vegetation cover (Pv) was derived from NDVI extrema (Eq. 9) to support emissivity estimation for LST retrieval. TGSI (Eq. 10) measured soil coarseness, capturing aeolian sand mobility and surface texture changes. NDSI (Eq. 11) quantified soil salinity, reflecting the extent of salt-affected and vegetation-stressed surfaces. LST was retrieved using radiometric and emissivity-corrected thermal calculations (Eqs. 4–6), representing the thermal anomaly component of degradation.

For multi-temporal synthesis, each index was standardized using z-score normalization, and resultant composite layers were generated by averaging values across the four decades (Eqs. 12–14). These composites provided long-term, stable representations of vegetation decline, soil coarsening, salinity variation, and surface heating. The integrated multi-index framework forms a robust geospatial model capable of diagnosing aeolian-driven desertification and anthropogenic land degradation processes with enhanced clarity and reduced redundancy.

Classification and hotspot delineation

All raster index layers (NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST) were reclassified into five degradation intensity classes: very low, low, moderate, high, and very high using the raster reclassification tool in ArcGIS. The classification thresholds were based on statistical parameters (minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation) derived from the pixel distribution of each index. To enhance spatial precision, fifteen buffer zones were generated from the Digital Number (DN) values of each index. These zones represented the gradient of degradation intensity and were used to extract hotspot regions through mask extraction and equal interval classification. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationships among NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST, revealing the interdependence between vegetation decline, surface temperature rise, salinity increase, and soil textural changes.

Validation and accuracy assessment

Field validation was performed through extensive ground surveys using GPS-based sampling at representative degraded and non-degraded sites. Observations were correlated with satellite-derived indices to verify their spatial accuracy. Statistical validation was conducted using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, where the Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.851 indicated high model performance and reliability in hotspot detection.

Methodological novelty and framework

The methodological novelty of this study lies in the development of an integrated multi-index geospatial framework that simultaneously employs NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST to capture both biophysical and thermal dimensions of land degradation over multiple decades. Unlike conventional single-index approaches, this composite methodology enables a multifactorial, spatially comprehensive, and temporally consistent assessment of desertification driven by aeolian sand migration and anthropogenic pressures. The incorporation of multi-decadal Landsat datasets, systematic buffer-zone modeling, and AUC-based accuracy evaluation strengthens the robustness, reproducibility, and scalability of the framework for semi-arid environments. A schematic representation of the workflow including data acquisition, preprocessing, index derivation, classification, and hotspot delineation is provided in Fig. 2.

Results and discussions

NDVI analysis and reclassification (1990 to 2020)

NDVI is a key indicator of vegetation vigor and is directly linked to surface thermal behavior, as healthy vegetation reduces LST through evapotranspiration and canopy shading54,55. Its temporal variability therefore provides an effective measure for understanding land degradation dynamics in semi-arid environments.

Across the four decadal Landsat datasets, NDVI values exhibit a clear declining trend, reflecting progressive vegetation stress and landscape degradation. In 1990 (Landsat 4–5 TM, 13 March), NDVI ranged from − 0.68 to 0.56, capturing moderate vegetation pockets within the predominantly semi-arid terrain (Fig. 3a). By 2000 (Landsat 7 ETM+ , 16 March), NDVI values decreased to − 0.50 to 0.42, indicating emerging stress associated with expanding fallow fields and increasing aridity (Fig. 3b). In 2010 (Landsat 7 ETM+ , 19 March), NDVI values further declined to − 0.68 to 0.29, signifying widespread vegetation degradation and reduced plant vigor (Fig. 3c). By 2020 (Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS, 27 April), NDVI values ranged from − 0.15 to 0.46, showing localized recovery in irrigated and managed agricultural zones, while large tracts continued to exhibit sparse or stressed vegetation (Fig. 3d).

(a) NDVI Values in 1990; (b) NDVI Values in 2000; (c) NDVI Values in 2010; (d) NDVI Values in 2020; (e) Reclassified NDVI in 1990; (f) Reclassified NDVI in 2000; (g) Reclassified NDVI in 2010; (h) Reclassified NDVI in 2020 (All maps were generated from multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) to derive NDVI and its reclassified classes).

To ensure temporal consistency and improve interpretability, NDVI datasets from all four years were normalized and reclassified into five vegetation density classes using equal-interval classification in ArcGIS. This standardized reclassification facilitated spatial comparisons and enhanced the detection of long-term vegetation transitions relevant to land degradation hotspot identification.

The reclassified NDVI distributions demonstrate notable shifts across the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals (Table 2; Fig. 3e–h). In 1990, NDVI categories spanned − 0.6800 to 0.5556 with a standard deviation of 0.3163 (Fig. 3e). In 2000, values ranged from − 0.5000 to 0.4815 with a standard deviation of 0.2717 (Fig. 3f). The 2010 reclassification showed values between − 0.6768 and 0.2857 and a standard deviation of 0.2377 (Fig. 3g). By 2020, NDVI values improved marginally to − 0.1453 to 0.4643, with a reduced standard deviation of 0.1657 (Fig. 3h).

These results illustrate pronounced spatial and temporal fluctuations in vegetation cover, driven primarily by aeolian sand migration, recurrent droughts, groundwater depletion, and intensified human pressure. Although widespread degradation is evident, certain irrigated and conservation-supported zones display minor recovery, reflecting localized improvements in vegetation stability.

LST analysis and reclassification (1990 to 2020)

LST was retrieved using the USGS single-channel LST model, applying the thermal infrared Band 6 for Landsat 4–5 TM and Landsat 7 ETM+ , and Band 10 for Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS56. The LST maps for 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 (Fig. 4a–d) reveal a clear and continuous warming trend across the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals.

(a) Land Surface Temperature in 1990; (b) Land Surface Temperature in 2000; (c) Land Surface Temperature in 2010; (d) Land Surface Temperature in 2020; (e) Reclassified LST in 1990; (f) Reclassified LST in 2000; (g) Reclassified LST in 2010; (h) Reclassified LST in 2020 (All maps were generated from multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) to derive LST and its reclassified classes).

In 1990, LST ranged between 21.815 °C and 36.312 °C (Fig. 4a). By 2000, temperatures increased to 24.841 °C and 39.792 °C (Fig. 4b). In 2010, LST rose further to 24.619 °C and 42.831 °C (Fig. 4c), and by 2020 reached its highest values, 25.725 °C and 47.717 °C (Fig. 4d). Over the 30-year period, maximum LST increased by ~ 11.4 °C, accompanied by a noticeable rise in minimum LST values, indicating sustained intensification of surface heating.

All LST datasets were reclassified into five thermal classes using equal-interval classification to standardize the temperature ranges and enable consistent temporal comparison. The reclassified maps (Fig. 4e–h) show systematic thermal intensification, with progressive expansion of high-temperature zones and contraction of cooler zones (Table 3).

In 1990 (Fig. 4e), reclassified LST zones ranged from 21.815 °C to 23.864 °C (lowest class) to 32.795 °C to 36.312 °C (highest), with a standard deviation of 4.684 °C. By 2000 (Fig. 4f), the lowest LST class increased to 27.265 °C to 30.457 °C, while the highest reached 36.882 °C to 39.792 °C, with a standard deviation of 4.922 °C. In 2010 (Fig. 4g), thermal zones spanned 24.619 °C to 28.214 °C (lowest) to 42.625 °C to 42.831 °C (highest), and the standard deviation rose to 5.529 °C. In 2020 (Fig. 4h), temperature classes expanded further, from 25.725 °C to 29.370 °C to 42.625 °C to 47.717 °C, with the highest variability (6.986 °C) recorded in the dataset.

The gradual increase in both temperature range and variability reflects progressive surface heating and spatial heterogeneity in thermal behavior, consistent with intensifying land degradation, reduced vegetation cover, and increasing soil exposure over time.

TGSI analysis and reclassification (1990 to 2020)

The TGSI is a key spectral indicator for assessing surface texture, topsoil roughness, and grain-size variability factors closely linked to erosion susceptibility and aeolian activity in semi-arid regions57. TGSI maps for 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 were generated using multispectral reflectance data (Fig. 5a–d). To ensure comparability across decades, all TGSI layers were reclassified into five equal-interval classes in ArcGIS, representing progressive shifts from fine to coarse surface materials. In 1990 (Fig. 5e), TGSI values ranged from − 0.306 to 0.411, with a standard deviation of 0.185 (Table 4), indicating high spatial variability in surface texture. By 2000 (Fig. 5f), the TGSI range narrowed to − 0.225 to 0.241 (SD: 0.130). A further reduction was evident in 2010 (− 0.209 to 0.209; SD: 0.113; Fig. 5g). In 2020 (Fig. 5h), TGSI values ranged from − 0.136 to 0.202, with the lowest standard deviation (0.092), reflecting more homogeneous surface conditions.

(a)TGSI of the Study Area in 1990; (b) TGSI of the Study Area in 2000; (c) TGSI of the Study Area in 2010; (d) TGSI of the Study Area in 2020; (e) Reclassified TGSI in 1990; (f) Reclassified TGSI in 2000; (g) Reclassified TGSI in 2010; (h) Reclassified TGSI in 2020 (All maps were generated from multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) to derive TGSI and its reclassified classes).

The progressive narrowing of TGSI ranges and declining standard deviation values from 1990 to 2020 indicate decreasing spatial heterogeneity in surface texture across Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals. High TGSI zones consistently align with coarser, erosion-prone surfaces, whereas lower values correspond to finer, relatively stable soils. The four decadal reclassified TGSI maps thus provide a coherent representation of shifting surface texture dynamics relevant to land degradation assessment.

NDSI analysis and reclassification (1990 to 2020)

The NDSI provides an effective measure of surface soil salinity, which influences soil productivity, vegetation health, and long-term land degradation trajectories58. NDSI maps were generated for 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020 using multispectral Landsat datasets (Fig. 6a–d). To enable consistent temporal comparison, all NDSI layers were reclassified into five equal-interval salinity classes, accounting for variations in soil moisture, salt crust formation, and mineralogical composition.

(a) NDSI of the Study Area in 1990; (b) NDSI of the Study Area in 2000; (c) NDSI of the Study Area in 2010; (d) NDSI of the Study Area in 2020; (e) Reclassified NDSI in 1990; (f) Reclassified NDSI in 2000; (g) Reclassified NDSI in 2010; (h) Reclassified NDSI in 2020 (All maps were generated from multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) to derive NDSI and its reclassified classes).

For 1990, reclassified NDSI values ranged from − 0.793 to 0.592 (Fig. 6e), with the lowest class spanning − 0.793 to − 0.429 and the highest from 0.157 to 0.592. The standard deviation for this year was 0.385 (Table 5). In 2000, values varied between − 0.769 and 0.239 (Fig. 6f), with reclassified limits from − 0.769 to − 0.500 (lowest) and − 0.049 to 0.239 (highest), and a standard deviation of 0.284. For 2010, NDSI values ranged from − 0.724 to 0.345 (Fig. 6g), with the lowest class (− 0.724 to − 0.401) and highest (− 0.007 to 0.345); the standard deviation was 0.286. In 2020, reclassified values extended from − 0.700 to 0.227 (Fig. 6h), with the lowest class (− 0.700 to − 0.445) and highest (− 0.060 to 0.227), and a standard deviation of 0.255.

The NDSI results show a progressive reduction in highly saline surfaces from 1990 to 2020, particularly across the northern and northeastern sectors. However, persistent moderate-to-high salinity zones remain in the central and southern regions, associated with arid soil conditions, inadequate drainage, and intensive agricultural activity. The decreasing standard deviation from 0.385 (1990) to 0.255 (2020) indicates reduced spatial variability in surface salinity, reflecting shifts in land-use practices, groundwater extraction patterns, and regional climatic variability.

Statistical reclassification for degradation assessment

A quantitative evaluation of land degradation was performed using a composite statistical framework that integrates four key biophysical indicators: NDVI, LST, TGSI, and NDSI, each representing a specific dimension of degradation: vegetation loss, surface heating, soil coarsening, and salinization. All index layers were standardized to a common scale to ensure comparability, and mean composite maps were generated for the period 1990–2020.

These composite layers were reclassified into fifteen statistical classes (Class 1–15) using the equal-interval method in ArcGIS. The classification reflects the full spectrum of degradation intensity as follows: Classes 1–3: Very low degradation; Classes 4–6: Low degradation; Classes 7–9: Moderate degradation; Classes 10–12: High degradation; Classes 13–15: Very high degradation.

Reclassification was executed using Raster Calculator and Spatial Analyst tools, based on pixel-wise statistical distribution. Each successive class captures an incremental increase in degradation intensity across all indices. The areal extent (km2) of each class was calculated to quantify spatial patterns of degradation severity.

This multi-index, statistically driven approach enables the identification of integrated degradation hotspots influenced by both natural drivers, such as aeolian sand transport and semi-arid climate and anthropogenic pressures, including over-cultivation and groundwater depletion. The resulting composite degradation maps serve as a robust spatial framework for monitoring ecosystem stress, guiding land management interventions, and supporting long-term desertification mitigation strategies in semi-arid environments.

Mean NDVI image of the study area and reclassification

Multi-temporal NDVI imagery (1990–2020) was processed using the Raster Math Calculator in ArcGIS to compute the pixel-wise mean NDVI (Eq. 12). This composite reflects long-term vegetation dynamics and cumulative ecological response across the study area. The resulting mean NDVI map (Fig. 7a) shows values ranging from − 0.08 to 0.2383, indicating heterogeneous vegetation density and varying degrees of degradation.

(a)Mean NDVI of the study area; (b) Reclasses of NDVI image of the study area; (c) Mean TGSI of the study area; (d) Reclasses of TGSI image of the study area (All maps were generated from multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) to derive NDVI, TGSI and its reclassified classes). (e) Mean NDSI of the study area; (f) Reclasses of NDSI image of the study area; (g) Mean LST of the study area; (h) Reclasses of LST image of the study area (All maps were generated from multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) to derive NDSI, LST and its reclassified classes).

For enhanced interpretation, the mean NDVI layer was reclassified into fifteen statistical classes using natural break intervals in ArcGIS. These classes represent a continuous gradient of vegetation conditions from very low (Class 1) to very high (Class 15) (Fig. 7b). The class-wise areal extents were computed using pixel statistics (Table 6 and also integrated in Fig. 8a).

The area distribution for the fifteen classes is as follows: Class 1—2.90 km2; Class 2—7.84 km2; Class 3—18.74 km2; Class 4—54.57 km2; Class 5—146.68 km2; Class 6—190.56 km2; Class 7—210.66 km2; Class 8—166.78 km2; Class 9—134.01 km2; Class 10—57.18 km2; Class 11—22.70 km2; Class 12—14.49 km2; Class 13—12.07 km2; Class 14—5.93 km2; Class 15—2.28 km2. The dominance of mid-range NDVI classes (6–9) reflects the prevailing semi-arid vegetation conditions and prolonged ecological stress associated with aeolian activity, variable rainfall, and land-use pressures in the Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals.

Mean TGSI image of the study area and reclassification

Mean TGSI values for 1990–2020 were computed using the Raster Math Calculator in ArcGIS (Eq. 13) to represent long-term surface textural variability and sediment characteristics. The resulting mean TGSI image (Fig. 7c) shows values ranging from − 0.022 to 0.0323, reflecting spatial variations in soil roughness and grain-size distribution associated with aeolian processes and surface exposure.

To support degradation evaluation, the mean TGSI layer was reclassified into fifteen statistical classes using the Reclassify tool in ArcGIS, where Class 1 denotes very low TGSI values and Class 15 denotes the highest values. The corresponding areal extents are: Class 1—7.23 sq. km; Class 2—9.23 sq. km; Class 3—9.11 sq. km; Class 4—37.93 sq. km; Class 5—65.17 sq. km; Class 6—99.59 sq. km; Class 7—123.26 sq. km; Class 8—144.59 sq. km; Class 9—126.55 sq. km; Class 10—96.42 sq. km; Class 11—73.03 sq. km; Class 12—66.06 sq. km; Class 13—73.36 sq. km; Class 14—67.26 sq. km; and Class 15—49.42 sq. km.

The spatial distribution of these reclassified classes is illustrated in Fig. 7d, with the areal statistics summarized in Table 6 (also integrated in Fig. 8b). The dominance of Classes 7–10 across the region indicates moderate to high TGSI values, suggesting widespread surface coarsening and active aeolian reworking. These patterns align with observed degradation in Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals, where sparse vegetation and wind-driven erosion promote sediment mobilization.

Mean NDSI image of the study area and reclassification

Mean value–based NDSI images for the period 1990–2020 were generated using the Raster Math Calculator in ArcGIS. The mean NDSI for each pixel was computed using Eq. (14), representing the long-term spectral response of surface soils and providing an integrated measure of soil exposure and degradation intensity across the study area.

Figure 7e shows the resultant mean NDSI image, where values range from − 0.6427 to 0.3491, indicating substantial spatial variability in soil brightness, moisture conditions, and mineralogical characteristics. To support degradation assessment, the mean NDSI layer was reclassified into fifteen statistical classes using the Equal Interval method in ArcGIS. Each class corresponds to a specific NDSI range, increasing from Class 1 (very low soil exposure) to Class 15 (very high soil exposure). The reclassified map is presented in Fig. 7f.

The areal extents of the fifteen NDSI classes were calculated using pixel-based spatial statistics. The area distribution is as follows: Class 1—6.28 sq. km; Class 2—7.04 sq. km; Class 3—8.39 sq. km; Class 4—16.97 sq. km; Class 5—30.82 sq. km; Class 6—49.91 sq. km; Class 7—80.67 sq. km; Class 8—103.51 sq. km; Class 9—104.69 sq. km; Class 10—154.66 sq. km; Class 11—254.28 sq. km; Class 12—175.27 sq. km; Class 13—51.92 sq. km; Class 14—2.55 sq. km; and Class 15—1.26 sq. km. A spatial representation of these classes is shown in Fig. 8c, and the statistical summary is provided in Table 6.

The results indicate that Classes 10 to 12 occupy the largest spatial extent, reflecting widespread high soil exposure and reduced vegetation density. These conditions are predominantly concentrated in Kalyandurg, Settur, and Gummagatta mandals, where intensive agriculture, overgrazing, and vegetation clearance have contributed to increased soil reflectivity and surface instability.

Mean LST image of the study area and reclassification

Mean LST images for 1990–2020 were generated using the Raster Math Calculator in ArcGIS, with pixel-wise mean temperature computed using Eq. (7). This multi-temporal averaging provides a long-term thermal profile useful for identifying persistent heat anomalies associated with land degradation.

The resultant mean LST map (Fig. 7g) shows temperatures ranging from 24.058 to 40.192 °C, reflecting considerable spatial variability linked to differences in vegetation, soil moisture, and surface materials. The mean LST raster was reclassified into 15 equal-interval temperature classes (Fig. 7h) to standardize spatial variation and quantify thermal intensity.

The area distribution of the temperature classes is: Class 1—3.27 sq km; Class 2—7.52 sq km; Class 3—7.59 sq km; Class 4—8.00 sq km; Class 5—13.24 sq km; Class 6—21.86 sq km; Class 7—36.50 sq km; Class 8—57.34 sq km; Class 9—82.33 sq km; Class 10—93.88 sq km; Class 11—116.56 sq km; Class 12—144.58 sq km; Class 13—162.22 sq km; Class 14—184.26 sq km; Class 15—109.05 sq km. The class distribution and corresponding areas are presented in Fig. 8d and Table 6. Higher temperature classes (12–14) occupy most of the central and western parts of the study area, while lower temperature classes are concentrated in the northern zones.

Correlation and regression analysis

LST values derived from 1990 to 2020 were statistically correlated with NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI to assess their interrelationship. DN values for all indices and LST were extracted using 30 stratified random points for each layer through the Extract Multi Values to Points tool in ArcGIS. The spatial patterns show that negative NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI values are concentrated in the central and southern parts of the study area, particularly along the Hagari River basin, where aeolian sand migration causes to land degradation and desertification conditions. These zones correspond to surfaces dominated by exposed soil and aeolian sands. Regression results indicate that these negative index values consistently align with higher LST ranges, confirming a strong inverse association between vegetation/soil index responses and surface temperature across all periods.

LST correlation with NDVI

High NDVI values occurred mainly in the northeastern region, indicating dense vegetation cover and active agricultural areas. Low or negative NDVI values dominated the central region, characterized by aeolian sand migration and exposed bare soils. Regression analysis revealed a strong positive relationship between NDVI and LST (R2 = 0.9482), indicating that higher NDVI corresponds to higher surface temperatures in the study area. The scatterplot illustrating this relationship is shown in Fig. 9a.

LST Correlation with TGSI

Higher TGSI values in the eastern part of the study area suggested moderately coarse soils with partial vegetation cover, whereas negative TGSI values in the dune-dominated central sector indicated fine, mobile sands with minimal vegetation. These areas corresponded to the highest LST values, highlighting the thermal sensitivity of exposed sandy surfaces. The correlation between LST and TGSI revealed a positive linear relationship (R2 = 0.8589), demonstrating that soil texture and surface roughness substantially influence surface thermal behaviour. The corresponding scatterplot is presented in Fig. 9b.

LST Correlation with NDSI

Higher NDSI values were observed in the eastern and southwestern regions, corresponding to moist or vegetated surfaces, while lower NDSI values dominated the central and western degraded zones prone to salinity and dryness. These low-NDSI areas coincided with elevated LST, indicating faster heating of dry, saline, or exposed soils. Regression analysis revealed a strong positive relationship (R2 = 0.9219) between NDSI and LST, underscoring the thermal sensitivity of moisture-deficient and saline surfaces. The corresponding scatterplot is presented in Fig. 9c.

All three indices NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI showed strong and consistent correlations with LST, reflecting the integrated influence of vegetation density, soil texture, and surface salinity on surface thermal response. These extracted DN reflectance values were subsequently used to generate buffer zones, which served as the basis for delineating land degradation and desertification hotspots across the study area.

Land degradation hotspots identification

Land degradation hotspots were delineated through buffer zone analysis using the extracted DN reflectance values of NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST. This multi-index approach allowed precise detection of areas exhibiting pronounced vegetation loss, soil instability, salinization, and elevated surface temperatures. A total of fifteen representative points were extracted for each index, spatially aligned with the LST raster to ensure consistency in detecting degradation intensity. These index-specific buffer zones formed the basis for identifying hotspot clusters where adverse spectral responses were consistently observed, revealing zones undergoing accelerated land degradation and desertification across the study area.

Buffer zone creation

To identify and spatially refine land degradation hotspots, buffer zones were generated using the DN-derived reflectance values from NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI following atmospheric and radiometric correction. DN (or scaled reflectance) values were retained at this stage because they preserve the original spectral variability needed to distinguish subtle differences in surface conditions particularly essential for semi-arid landscapes where vegetation cover is sparse and soil exposure is high. This approach follows established practices where DN-based gradients are used for pattern recognition and local anomaly detection59.

Fifteen representative buffer points were selected for each index to adequately capture the full spectrum of spectral responses associated with vegetation stress, topsoil coarseness, and salinity. The number fifteen was chosen to ensure statistical robustness while preventing over-fragmentation of the landscape; similar multi-point sampling approaches are commonly adopted in hotspot-based environmental mapping in semi-arid terrains. A 300-m buffer radius was applied around each point to represent the spatial influence zone of similar spectral behavior (Fig. 10). This radius is consistent with: (i) the average pixel block size required to suppress noise in Landsat-based surface indices, (ii) the characteristic scale at which aeolian sand deposition and soil degradation patterns manifest in the study area, and (iii) buffer radii used in previous land degradation and desertification assessments in dryland environments60,61,62.

Field survey based mean NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST buffer points of the study area. The buffer points were selected based on DN reflectance similarity ranges for each index and validated through field observations. The spatial point data were extracted and processed in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) using multi-temporal Landsat datasets downloaded from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/).

The DN reflectance values within each buffer were extracted using the Mask Extraction Tool in ArcGIS to isolate homogeneous spectral clusters. These clusters served as proxies for field-verifiable degradation classes. Subsequent field surveys were conducted to validate the spectral interpretations, confirm hotspot locations, and record visual indicators such as sand accumulation, exposed soil crusts, reduced vegetation, and human-induced disturbances. Through the integration of multi-temporal indices, buffer-based spatial sampling, and ground truthing, a high-confidence land degradation and desertification hotspot map was generated. This map delineates areas where aeolian sand migration, low vegetation density, salinization, and anthropogenic pressures collectively contribute to ongoing land degradation across Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal mandals.

Land degradation hotspots

Land degradation and desertification hotspots were delineated by integrating the lower DN reflectance values of NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI with the higher thermal intensities derived from LST. Pixels exhibiting similar DN ranges across all indices were spatially aligned using the mask extraction technique in ArcGIS and merged into a composite layer to identify consistently degraded zones. Multi-temporal Landsat datasets: Landsat 4–5 TM (13 March 1990), Landsat 7 ETM+ (16 March 2000; 19 March 2010), and Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS (27 April 2020) were used to evaluate degradation patterns over three decades. After performing radiometric and atmospheric corrections, LST, NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI were generated using standard retrieval algorithms.

Although the intermediate index layers were statistically reclassified into major and sub-class categories to support trend analysis, the final hotspot output was derived directly from the continuous composite intensity surface. Retaining the native 30 m resolution of the Landsat imagery preserves pixel-level variability and avoids artificial discretization of hotspot severity. This approach provides a more realistic depiction of spatial heterogeneity and ensures that the final hotspot surface reflects the true continuity of degradation processes rather than forced categorical breaks.

For spatial refinement, representative buffer points were generated for each index at 300 m intervals to capture similar DN reflectance zones, and zonal statistics were applied to determine the dominant conditions within each buffer. Severely affected pixel clusters were then extracted using cell statistics, resulting in the identification of approximately 192 sq. km of persistent land degradation and desertification hotspots. These hotspots are primarily concentrated along the central and southwestern regions of the study area, especially near the Hagari River belt, where aeolian sand migration, sparse vegetation, and sustained anthropogenic pressure have intensified degradation. The resultant Land Degradation and Desertification Hotspot Map (Fig. 11) illustrate this continuous intensity gradient and serves as a robust geospatial tool for environmental monitoring and sustainable land management planning.

Land degradation and desertification hotspots map of the study area. The map was generated in ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview) using Landsat datasets from the USGS Earth Explorer (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/).

Validation

To assess the reliability and predictive accuracy of the land degradation and desertification hotspot map, a ROC curve and AUC analysis were employed. Ground-truth data collected through extensive field surveys were used as the validation dataset, while predictive maps were generated using remote sensing-derived indices NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST. The model classified the study region into varying levels of land degradation risk, and the predicted hotspots were systematically compared with the observed ground-truth data to evaluate model performance. The ROC curve was constructed by plotting the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) at different threshold levels. The AUC value, representing the overall discriminative power of the model, was found to be 0.851 (Fig. 12), signifying a high level of classification accuracy. This AUC value indicates the model’s strong capability to differentiate between degraded and non-degraded areas, confirming the robustness of the integrated geospatial approach. The use of multi-temporal NDVI, TGSI, NDSI, and LST indices effectively captured the spatial heterogeneity of land degradation processes across the study area. The high AUC score validates the efficacy of spectral and thermal parameters in identifying degradation-prone zones and confirms the reliability of the developed hotspot mapping framework. Consequently, these findings provide a strong scientific basis for targeted land restoration, sustainable management, and mitigation strategies in semi-arid regions experiencing aeolian sand migration and anthropogenic stress.

Validation of hotspots map using the AUC curve (This was performed using Microsoft Excel based on spatial statistics extracted from ArcGIS 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview)).

Discussion

The integrated multi-temporal analysis of LST, NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI provides a coherent understanding of the degradation dynamics in the semi-arid environment of the study area. The results collectively indicate a progressive intensification of thermal stress, vegetation loss, soil texture deterioration, and surface salinity over the last three decades. These trends are consistent with regional desertification pathways commonly observed in dryland systems subjected to prolonged anthropogenic pressure and climatic variability.

The strong inverse relationship between NDVI and LST demonstrates the pivotal role of vegetation cover in moderating surface temperatures by reducing soil exposure and enhancing evapotranspiration. Similar inverse correlations have been widely reported in arid and semi-arid landscapes, where vegetation scarcity amplifies thermal gradients and accelerates land degradation63,64. In the present study, the central and southern zones characterized by sparse vegetation corresponded to regions of distinctly elevated LST, indicating intensified heat storage by exposed sandy and degraded soils.

The positive correlations of LST with TGSI and NDSI highlight the combined influence of soil texture and salinity on thermal behavior. Fine-grained sandy surfaces and saline crusts exhibited higher daytime temperatures due to low moisture retention and high emissivity. These observations align with earlier findings that emphasize the sensitivity of LST to variations in soil roughness, particle size, and moisture content47,65. The strong correlation strengths (R2 = 0.8589 to 0.9219) confirm the reliability of Landsat-derived indices in capturing degradation-induced surface alterations.

The delineation of hotspots using composite pixel alignment further underscores how multi-index integration can effectively represent the cumulative impact of vegetation decline, soil destabilization, and salinity expansion. The persistent clustering of hotspots along the central and southwestern Hagari River belt reflects active aeolian processes, intensified sand migration, and long-term anthropogenic disturbances such as overgrazing and land misuse. Similar hotspot concentration patterns have been documented in other semi-arid riverine drylands, where hydrological intermittency and loose sediment regimes accelerate surface instability66,67.

The identification of 192 sq. km as degradation hotspots has important implications for land management. These zones represent critical areas where thermal anomalies, textural degradation, and vegetation loss intersect, indicating heightened vulnerability to future desertification. Integrating the hotspot outputs with thematic geological, geomorphological, and soil layers reveals that regions underlain by fluvial sand deposits and pediplain surfaces are more susceptible to degradation due to their inherent low structural cohesion and high erodibility. Furthermore, the long-term mean LST profile provides clear evidence of sustained thermal buildup, linking directly with the progressive reduction of NDVI and dominance of medium- to high-intensity TGSI and NDSI classes. This multi-decadal pattern likely reflects both climatic warming and local-scale anthropogenic stressors, consistent with broader warming trends observed across peninsular India’s semi-arid tracts.

The multi-index and multi-temporal framework adopted in this study demonstrates the significant advantage of remote sensing–GIS integration for assessing land degradation severity in data-scarce drylands. By combining spectral indices with pixel-level statistical modeling, the approach strengthens hotspot delineation and enhances the capacity to detect subtle degradation signatures that may not be evident through single-index or single-period analyses. The findings establish a consistent, scalable framework that can support environmental monitoring, targeted conservation, and policy interventions aimed at mitigating land degradation and desertification risks in vulnerable semi-arid ecosystems.

Limitations

This study provides a comprehensive multi-temporal assessment of land degradation; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is constrained by the spatial and temporal resolution of the Landsat datasets, which may not fully capture fine-scale degradation features or rapid seasonal changes. Second, the spectral indices (NDVI, TGSI, NDSI) and LST were derived under clear-sky conditions, and residual atmospheric effects or sensor noise may introduce uncertainties in index retrieval. Third, field validation was limited to selected locations, and the absence of long-term ground-based measurements restricts the assessment of temporal accuracy. In addition, the equal-interval reclassification and buffer-based zonation methods may generalize heterogeneous surface conditions, potentially smoothing local-scale variations. The anthropogenic drivers such as land-use practices and groundwater extraction were not quantitatively integrated into the model, which may influence the interpretation of degradation intensity in certain zones.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of multi-temporal remote sensing and GIS-based analysis for assessing land degradation and desertification in the semi-arid mandals of Bommanahal, Beluguppa, and Kanekal in Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh. The multi-decadal Landsat datasets (1990–2020) revealed a steady increase in land surface temperature accompanied by declining NDVI, TGSI, and NDSI values, indicating progressive vegetation stress, surface soil instability, and intensifying aeolian sand activity. Strong positive correlations between LST and the spectral indices highlight the sensitivity of vegetation condition, soil texture, and salinity to thermal stress across these semi-arid landscapes. Through multi-index reclassification, buffer analysis, and zonal statistics, approximately 192 sq. km were identified as persistent land degradation and desertification hotspots, primarily concentrated along the Hagari River. The AUC—ROC value of 0.851 validates the robustness and predictive reliability of the hotspot extraction model.

While the study provides a comprehensive long-term assessment, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The reliance on medium-resolution (30 m) Landsat imagery restricts the detection of fine-scale degradation features, and the use of four temporal snapshots may not fully capture short-term or seasonal variations in vegetation and soil conditions. Although field validation was conducted, broader in-situ measurements of soil properties, moisture, and salinity would help enhance the interpretation of index-derived patterns. Despite these constraints, the integrated geospatial framework offers valuable insights into the evolving degradation processes and supports evidence-based land management. The findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions such as afforestation, soil conservation, regulation of sand extraction, and sustainable agricultural practices to halt further degradation and improve ecosystem resilience in the vulnerable semi-arid regions of Anantapur.

Data availability

The raw data is obtained from NRSC Bhuvan and USGS website (https://bhuvan.nrsc.gov.in/ and https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) which is available free of cost and the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Mburu, B. K., Kung’u, J. B. & Muriuki, J. N. Climate change adaptation strategies by small-scale farmers in Yatta district, Kenya. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 9(9), 712–722 (2015).

Olagunju, T. E. Drought, desertification and the Nigerian environment: A review. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ. 7(7), 196–209 (2015).

Kar, A. Desertification: causes and effects. In Exploring Natural Hazards 159–206 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018).

Gabriele, M., Brumana, R., Previtali, M. & Cazzani, A. A combined GIS and remote sensing approach for monitoring climate change-related land degradation to support landscape preservation and planning tools: The Basilicata case study. Appl. Geomat. 1–36 (2022).

Eswaran, H., Lal, R. & Reich, P. F. Land degradation: An overview. Response to Land Degrad. 20–35 (2019)

Radda, I. A., Kumar, B. M. & Pathak, P. Land degradation in Bihar, India: an assessment using rain-use efficiency and residual trend analysis. Agric. Res. 10(3), 434–447 (2021).

Wani, S. P., Chander, G. & Sahrawat, K. L. Reversing land degradation through participatory watershed management: A case study from India. Land Degrad. Dev. 26(2), 147–162 (2015).

Srivastava, P. & Han, Z. Soil nutrient depletion and management in India. Geoderma 305, 368–376 (2017).

Periasamy, S. & Shanmugam, R. S. Agricultural Land Degradation in India. In Impact of Agriculture on Soil Degradation I: Perspectives from Africa, Asia, America and Oceania 219–257 (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022).

ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation). Land Degradation and Desertification Atlas of India. Retrieved from https://vedas.sac.gov.in/content/vcms/atlas/dsm/LDVA_Atlas_SAC-ISRO_2024.pdf (2024)

Mandal, C., Bhattacharyya, T., Jaiswal, M. K. & Ray, S. K. Quantifying the effects of soil texture on soil functions: A review. Geoderma 265, 110–120 (2016).

Singh, R. S., Meena, B. P. & Singh, R. P. Land degradation assessment using remote sensing and GIS techniques in selected districts of Punjab, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 78(1), 31 (2019).

Alexakis, D. D., Tapoglou, E., Vozinaki, A. E. K. & Tsanis, I. K. Integrated use of satellite remote sensing, artificial neural networks, field spectroscopy, and GIS in estimating crucial soil parameters in terms of soil erosion. Remote Sens. 11(9), 1106 (2019).

Badapalli, P. K. et al. Advanced geospatial modeling and assessment of land degradation severity zones in India’s semi-arid regions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 197(4), 453 (2025).

Jain, S. & Parihar, J. S. Monitoring vegetation health using multi-temporal NDVI analysis in arid ecosystems of western Rajasthan, India. J. Arid Land 8(6), 929–940 (2016).

Mishra, A. R. & Mishra, S. K. Evaluation of vegetation cover using NDVI in different land use/cover types in parts of Kumaun Lesser Himalaya, India. Geocarto Int. 32(7), 715–732 (2017).

Yengoh, G. T., Dent, D., Olsson, L., Tengberg, A. E. & Tucker III, C. J. Applications of NDVI for land degradation assessment. In Use of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to Assess Land Degradation at Multiple Scales: Current Status, Future Trends, and Practical Considerations 17-25. (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015).

Xiao, J., Shen, Y., Tateishi, R. & Bayaer, W. Development of topsoil grain size index for monitoring desertification in arid land using remote sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 27(12), 2411–2422 (2006).

Jaiswal, M. K., Bhattacharyya, T. & Mandal, C. Topsoil grain size index for soil texture characterization and its relationship with soil properties. Geoderma 239–240, 68–75 (2015).

Sahbeni, G., Ngabire, M., Musyimi, P. K. & Székely, B. Challenges and opportunities in remote sensing for soil salinization mapping and monitoring: A review. Remote Sens. 15(10), 2540 (2023).

Wu, J., Vincent, B., Yang, J., Bouarfa, S. & Vidal, A. Remote sensing monitoring of changes in soil salinity: A case study in inner Mongolia. China. Sens. 8(11), 7035–7049 (2008).

Seifi, M., Ahmadi, A., Neyshabouri, M. R., Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R. & Bahrami, H. A. Remote and Vis-NIR spectra sensing potential for soil salinization estimation in the eastern coast of Urmia hyper saline lake, Iran. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 20, 100398 (2020).

Huan, W. A. N. G., Ruiping, L. I., Yin, Z. H. A. N. G., Zhengzhong, L. I. & Meiling, W. E. I. Using multi-source and multi-index method to assess soil salinity in Hetao irrigation district in inner Mongolia. J. Irrig. Drain. 42(10) (2023)

Mumtaz, F. et al. Modeling spatio-temporal land transformation and its associated impacts on land surface temperature (LST). Remote Sens. 12(18), 2987 (2020).

Zhou, X. & Wang, Y. C. Dynamics of land surface temperature in response to land-use/cover change. Geogr. Res. 49(1), 23–36 (2011).

Kumar, B. P., Anusha, B. N., Babu, K. R. & Sree, P. P. Identification of climate change impact and thermal comfort zones in semi-arid regions of AP, India using LST and NDBI techniques. J. Clean. Prod. 407, 137175 (2023).

Pablos, M. et al. Multi-temporal evaluation of soil moisture and land surface temperature dynamics using in situ and satellite observations. Remote Sens. 8(7), 587 (2016).

Kumar, B. P., Babu, K. R., Anusha, B. N. & Rajasekhar, M. Geo-environmental monitoring and assessment of land degradation and desertification in the semi-arid regions using Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS, LST, and NDVI approach. Environ. Chall. 8, 100578 (2022).

Anusha, B. N., Babu, K. R., Kumar, B. P., Kumar, P. R. & Rajasekhar, M. Geospatial approaches for monitoring and mapping of water resources in semi-arid regions of southern India. Environ. Chall. 8, 100569 (2022).

Anusha, B. N. et al. Integrated studies for land suitability analysis towards sustainable agricultural development in semi-arid regions of AP, India. Geosyst. Geoenviron. 2(2), 100131 (2023).

Badapalli, P. K. Integrating Multi-Temporal Remote Sensing and Advanced Drought Modeling to Assess Desertification Dynamics in Semi-Arid Andhra Pradesh, India: A Framework for Sustainable Land Management 101654 (Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment, 2025).

Badapalli, P. K., Nakkala, A. B., Kottala, R. B. & Gugulothu, S. Geo environmental green growth towards sustainable development in semi-arid regions using physicochemical and geospatial approaches. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–18 (2022).

Tang, Z. et al. Effect of desertification on productivity in a desert steppe. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 27839 (2016).

Bhavani, P., Chakravarthi, V., Roy, P. S., Joshi, P. K. & Chandrasekar, K. Long-term agricultural performance and climate variability for drought assessment: A regional study from Telangana and Andhra Pradesh states, India. Geomat. Nat. Haz. Risk 8(2), 822–840 (2017).

Sivasankaranarayana, B. H. Anantapur (Director of Print. and Stationery at the Government Secretariat Press, 1970).

Kale, V. S., Narayana, A. C. & Jaiswal, M. K. Wind-blown, flash flood-deposited sands of Hagari River, Anantapur district, Andhra Pradesh. India. Curr. Sci. 119(3), 556–558 (2020).

Francis, W. Madras District Gazetteers: Bellary (Superintendent, Government Press, 1904).

Francis, W. Anantapur (Addison/Government Press, 1905).

Kumar, B. P., Babu, K. R., Rajasekhar, M. & Ramachandra, M. Assessment of land degradation and desertification due to migration of sand and sand dunes in Beluguppa Mandal of Anantapur district (AP, India), using remote sensing and GIS techniques. J. Ind. Geophys. Union 23(2), 173-180.3 (2019).

Badapalli, P. K., Raghu Babu, K., Rajasekhar, M. & Ramachandra, M. Assessment of aeolian desertification near Vedavathi river channel in central part of Andhra Pradesh: Remote sensing approach. Remote Sens. Land 3(1), 39–49 (2019).

Badapalli, P. K., Kottala, R. B. & Pujari, P. S. Aeolian Desertification: Disaster with Visual Impact in Semi-arid Regions of Andhra Pradesh, South India (Springer Nature, 2023)

Kaliraj, S., Chandrasekar, N., Parmar, M., Rejith, R. G., Dharumarajan, S., Lalitha, M. & Chandramohan, K. Assessment of land degradation vulnerability in the semi-arid region of Southern India using GIS-based MEDALUS approach. In Remote Sensing of Soils 591–608 (Elsevier, 2024).

Chander, G., Markham, B. L. & Helder, D. L. Summary of current radiometric calibration coefficients for Landsat MSS, TM, ETM+, and EO-1 ALI sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 113(5), 893–903 (2009).

Parente, C. TOA reflectance and NDVI calculation for Landsat 7 ETM+ images of Sicily. In Proc. in Electronic International Interdisciplinary Conference-The 2nd Electronic International Interdisciplinary Conference 351–354 (EDIS-Publishing Institution of the University of Zilina, 2013).

Chaves M, E. D., Picoli M, C. A. & Sanches I, D. Recent applications of Landsat 8/OLI and Sentinel-2/MSI for land use and land cover mapping: A systematic review. Remote Sens. 12(18), 3062 (2020).

Markham, B. L. Landsat MSS and TM post-calibration dynamic ranges, exoatmospheric reflectances and at-satellite temperatures. Landsat Tech. Notes 1, 3–8 (1986).

Sobrino, J. A., Jiménez-Muñoz, J. C. & Paolini, L. Land surface temperature retrieval from LANDSAT TM 5. Remote Sens. Environ. 90(4), 434–440 (2004).

Jiménez‐Muñoz, J. C. & Sobrino, J. A. A generalized single‐channel method for retrieving land surface temperature from remote sensing data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108(D22) (2003).

Weng, Q., Lu, D. & Schubring, J. Estimation of land surface temperature–vegetation abundance relationship for urban heat island studies. Remote Sens. Environ. 89(4), 467–483 (2004).

Jw, R. Monitoring vegetation systems in the great plains with ERTS. In Third NASA Earth Resources Technology Satellite Symposium, 1973, Vol. 1, 309–317 (1973)

Sobrino, J. A. & Raissouni, N. Toward remote sensing methods for land cover dynamic monitoring: Application to Morocco. Int. J. Remote Sens. 21(2), 353–366 (2000).

Haq, Y. U., Shahbaz, M., Asif, H. S., Al-Laith, A. & Alsabban, W. H. Spatial mapping of soil salinity using machine learning and remote sensing in Kot Addu, Pakistan. Sustainability 15(17), 12943 (2023).

Lu, D. & Weng, Q. A survey of image classification methods and techniques for improving classification performance. Int. J. Remote Sens. 28(5), 823–870 (2007).

Marzban, F., Sodoudi, S. & Preusker, R. The influence of land-cover type on the relationship between NDVI–LST and LST-T air. Int. J. Remote Sens. 39(5), 1377–1398 (2018).

Kumari, B. et al. Satellite-driven land surface temperature (LST) using Landsat 5, 7 (TM/ETM+ SLC) and Landsat 8 (OLI/TIRS) data and its association with built-up and green cover over urban Delhi, India. Remote Sens. Earth Syst. Sci. 1(3), 63–78 (2018).

Liu, Q., Liu, G. & Huang, C. Monitoring desertification processes in Mongolian Plateau using MODIS tasseled cap transformation and TGSI time series. J. Arid. Land 10(1), 12–26 (2018).

Abuelgasim, A. & Ammad, R. Mapping soil salinity in arid and semi-arid regions using Landsat 8 OLI satellite data. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 13, 415–425 (2019).

Voitik, A., Kravchenko, V., Pushka, O., Kutkovetska, T., Shchur, T. & Kocira, S. Comparison of NDVI, NDRE, MSAVI and NDSI indices for early diagnosis of crop problems. Agric. Eng. 27 (2023).

Chavez, P. S. Image-based atmospheric corrections-revisited and improved. Photogramm. Eng. Remote. Sens. 62(9), 1025–1035 (1996).

Bai, Z. G., Dent, D. L., Olsson, L. & Schaepman, M. E. Global assessment of land degradation and improvement 1. Identification by remote sensing. Report 2008 (2008).

Allbed, A. & Kumar, L. Soil salinity mapping and monitoring in arid and semi-arid regions using remote sensing technology: A review. Adv. Remote Sens. 2(4), 373–385 (2013).

Gojiya, K. M. et al. Remote sensing and GIS applications in soil salinity analysis: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 13(11), 2149–2161 (2023).

Karnieli, A. et al. Use of NDVI and land surface temperature for drought assessment: Merits and limitations. J. Clim. 23(3), 618–633 (2010).

Sun, D. & Kafatos, M. Note on the NDVI‐LST relationship and the use of temperature‐related drought indices over North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34(24) (2007).

Weng, Q. Thermal infrared remote sensing for urban climate and environmental studies: Methods, applications, and trends. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 64(4), 335–344 (2009).

Thomas, C., Ranchin, T., Wald, L. & Chanussot, J. Synthesis of multispectral images to high spatial resolution: A critical review of fusion methods based on remote sensing physics. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 46(5), 1301–1312 (2008).

Jiang, K. et al. Global land degradation hotspots based on multiple methods and indicators. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111462 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Director of the CSIR-National Geophysical Research Institute for providing the necessary facilities to conduct this work and for granting us permission to publish this paper. The first author expresses sincere gratitude to the Science and Engineering Research Board – National Post-Doctoral Fellowship (SERB-NPDF) for their valuable support (Fellowship Ref. No. PDF/2023/000774) during the tenure at CSIR-NGRI, Hyderabad. The authors also thank Editor-in-Chief/Handling Editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and valuable suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of the manuscript. This work is funded by the Main Lab Project MLP-7014 of the CSIR–National Geophysical Research Institute [Grant No. MLP-7014-28 (AKP)]. The CSIR-NGRI Library reference number is NGRI/Lib/2025/Pub-128.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used Chat Gpt to improve the language of the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Pradeep Kumar Badapalli: Manuscript preparation, Methodology creation and Validation. Remote Sensing and GIS mapping work. Mrs. Anusha Boya Nakkala: Manuscript statistics Generation, and correction. Dr. Raghu Babu Kottala: Manuscript corrections, English expert. Dr. Padma Sree Pujari: Manuscript corrections, data collection. Dr. Sakram Gugulothu: Manuscript corrections, corresponding author and validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Badapalli, P.K., Nakkala, A.B., Kottala, R.B. et al. Aeolian sand migration induced land degradation and desertification hotspots identification in the semi-arid rain shadow regions of Anantapur, India. Sci Rep 16, 1875 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31610-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31610-0