Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), particularly its N-terminally truncated isoform (NTT-MMP-2), plays a pivotal role in cardiac ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury. NTT-MMP-2 is induced by oxidative stress and activates both pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic pathways as well as an innate immune response within the cell. This study investigated the involvement of NTT-MMP-2 in oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiomyocyte injury, focusing on its mitochondrial activity. Using an ex vivo Langendorff-perfused rat heart model, we demonstrated that I/R significantly increased mitochondrial NTT-MMP-2 activity, total ROS/RNS production, and markers of cardiac injury, including lactate dehydrogenase activity (LDH), and reduced cardiac mechanical function. NTT-MMP-2 activity and cytochrome c positively correlated with nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) expression and LDH activity, while negatively correlating with heart rate and rate pressure product (cytochrome c), suggesting NTT-MMP-2 involvement in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic signaling. Partial inhibition of MMP-2 with siRNA reduced NTT-MMP-2 activity, preserved cardiac function, and decreased cytochrome c and NF-κB levels, although it paradoxically increased NFATc1 and IL-6 expression. These findings indicate that while NTT-MMP-2 contributes to oxidative and inflammatory damage during IRI, it may not be the sole regulator of innate immune activation. Moreover, IL-6 upregulation following MMP-2 silencing may reflect a compensatory cardioprotective response. This study identifies NTT-MMP-2 as a potential therapeutic target in ischemic heart disease, with siRNA-based strategies offering partial protection against I/R injury through modulation of mitochondrial stress and apoptosis pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a group of zinc-dependent proteolytic enzymes involved in many physiological and pathological processes1,2. Deregulation of MMP activity leads to the progression of various pathologies, including tissue destruction, fibrosis, and matrix weakening3,4,5,6. MMP-2 was initially believed to directly cause the development and progression of atherosclerosis7 and heart failure by remodeling extracellular matrix proteins1,8. Shortly afterward, its intracellular functions were also confirmed9. Activation of the intracellular form of MMP-2 plays an important role in the pathophysiology of oxidative stress-induced cardiac damage, as it is capable of proteolyzing specific sarcomeric proteins such as titin, myosin light chains 1 (MLC1), troponin I (TnI), and α-actinin10,11,12,13. Moreover, it has also been identified in the nuclear fraction, where it plays a role in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase degradation and DNA repair14. These processes lead to a significant deterioration of myocardial contractility during ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI)10.

Currently, several isoforms of MMP-2 have been reported. The full-length MMP-2 (FL-MMP-2, 72/68 kDa) is located in the sarcomeres of cardiomyocytes15 and may be activated by post-translational proteolytic removal of the propeptide domain, S-glutathiolation, S-nitrosylation, or phosphorylation16. The second form is N-terminally truncated MMP-2 (NTT-MMP-2, 65 kDa), which is produced under oxidative stress and results from transcription from an alternative promoter in the first intron of the mmp-2 gene17. It has also been found that FL-MMP-2 can be inefficiently directed to the secretory pathway, which subsequently induces the production of NTT-MMP-2 from the FL-MMP-2 form. NTT-MMP-2 then remains inside the cell and is not secreted17. It is considered that NTT-MMP-2 transcription is induced only under conditions of tissue damage, both in vivo and in vitro, and does not occur in cells under physiological conditions18. However, NTT-MMP-2 is a proteolytically active form despite lacking a signal sequence and an inhibitory propeptide domain18. It is located mainly in or near mitochondria, in the subsarcolemmal space of cardiomyocytes, where these organelles are abundant; however, it has also been detected in the cytoplasm17,18,19. Despite lacking an N-terminal targeting sequence, NTT-MMP-2 is able to penetrate mitochondria with the assistance of chaperone proteins such as heat shock protein 9020,21,22.

Since NTT-MMP-2 triggers mitochondrial-nuclear stress signaling via nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)17,18,19,23, it is suggested to activate pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic responses, as well as the innate immune response within the cell11,17,18,19,20. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of partial inhibition of NTT-MMP-2 by siRNA on the regulation of the immune response and the apoptotic cell death pathway under conditions of impaired redox balance.

Materials and methods

Ex vivo I/R model of heart perfusion

Male Wistar rats (10–11 weeks old, weighing 300–350 g) were used in the following experiments24. Rats were treated with an analgesic and anesthetic: buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, i.p.) and sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, i.p.). Hearts were quickly excised and immersed in ice-cold Krebs–Henseleit buffer (118 mmol/L NaCl; 4.7 mmol/L KCl; 1.2 mmol/L KH2PO4; 1.2 mmol/L MgSO4; 3.0 mmol/L CaCl2; 25 mmol/L NaHCO3; 11 mmol/L glucose; and 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.4). Immediately thereafter, spontaneously beating hearts were suspended onto a blunt-ended needle of the Langendorff system (EMKA Technologies, Paris, France) via the aorta and maintained at 37 °C. Hearts were perfused at a constant pressure (60 mm Hg) with Krebs–Henseleit buffer (pH 7.4, at 37 °C), continuously gassed (95% O2 and 5% CO2). Hemodynamic parameters, including heart rate (HR), coronary flow (CF), and left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP), were monitored using an EMKA recording system with IOX2 software (EMKA Technologies, Paris, France)25. After removal of the left atrium, a latex balloon filled with water and connected to a pressure transducer was inserted through the mitral valve into the left ventricle to measure HR and LVDP. The balloon volume was adjusted at the beginning of perfusion to achieve an end-diastolic pressure of 8–10 mm Hg. LVDP was estimated as the difference between peak systolic and diastolic pressure. Recovery of rate pressure product (RPP), representing the recovery of cardiac mechanical function, was calculated as the product of HR and LVDP (systolic minus diastolic ventricular pressure) – RPP at 77 min of perfusion (end of perfusion) relative to 25 min of perfusion.

Hearts were subjected to 25 min of aerobic stabilization, followed by 22 min of global no-flow ischemia and 30 min of aerobic reperfusion at 37 °C26. A schematic representation of the experimental protocol is shown in Fig. 1. In the study group – I/R + siRNA and in I/R + scrRNA group, after 15 min of aerobic stabilization, a mixture of MMP-2 siRNA (330 pmol) or scrambled RNA and siPORT Amine agent in Krebs–Henseleit buffer was administered for 10 min prior to ischemia and again during the first 10 min of reperfusion. Coronary effluents for biochemical analysis were collected at 47 min of perfusion (the onset of reperfusion) in a constant volume of 15 mL. After completion of the perfusion protocol (77 min from the start of perfusion, corresponding to the end of reperfusion), hearts were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C until further analysis.

Scheme of the experimental protocol. Hearts underwent 25 min of aerobic stabilization (Aero 25’), 22 min of global no-flow ischemia (Ischemia 22’), and 30 min of reperfusion at 37 °C (Reperfusion 30’). In the I/R + siRNA group, and Aero siRNA groups, MMP-2 siRNA mixed with siPORT Amine in Krebs–Henseleit buffer and in group I/R + scrRNA scrambled RNA with siPORT in K-H buffer was infused for 10 min before ischemia and again during the first 10 min of reperfusion. Coronary effluents were collected at 47 min (onset of reperfusion). Aero group was permanently perfused aerobically during the whole experiment. Figure created with BioRender.com.

siRNA/siPORT mixture preparation

A pool of three target-specific 19–25 nucleotide small interfering RNAs (MMP-2 siRNAs), designed to inhibit rat MMP-2 gene expression (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA, cat. no. sc-108049), was diluted in siRNA Dilution Buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA) to a final concentration of 10 µM in a buffer containing 10 µM Tris–HCl, 20 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). The mixture was aliquoted and stored at –20 °C. The siPORT Amine Polyamine-Based Transfection Agent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) was used to transfect siRNAs into cardiomyocytes. siPORT Amine Agent was diluted in Krebs–Henseleit buffer at a 1:9 ratio. Thereafter, siRNA (330 pmol) was mixed with siPORT Agent in equal volumes and administered to the hearts in Krebs–Henseleit buffer (250 mL, at 37 °C). SiPORT with Krebs–Henseleit buffer served as vehicle control and scrambled siRNA (Sanda Scruz, cat. No. SC-37007. Scrambled RNA consisting of scrambled sequence that will not lead to the specific degradation of any cellular message, was prepared and treated the same as MMP-2 siRNA. Preliminary results showed that siPORT did not affect MMP-2 as well as mechanical function of the heart (data not shown).

Isolation of mitochondrial, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions from cardiomyocytes

Minute™ Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Muscle Tissues/Cultured Muscle Cells (Invent Biotechnologies, Inc., Plymouth, USA) was used to isolate mitochondrial fractions from heart tissue. The isolation procedure was based on a series of centrifugation steps of powdered heart tissue (30–40 mg) using specialized filter cartridges, tissue dissociation beads, buffers (proprietary composition; supplemented with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail [Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA] at a ratio of 1:100) and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions were collected, frozen, and stored at –80 °C until further analysis.

Heart tissue and mitochondrial homogenates preparation

First, frozen hearts were pulverised in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. Next, heart powder and mitochondrial fraction pellets were suspended in cold homogenization buffer (50 mmol/L Tris–HCl (pH 7.4); 3.1 mmol/L sucrose; 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol; 10 mg/mL leupeptin; 10 mg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor; 2 mg/mL aprotinin; and 0.1% Triton X-100) and subjected to three cycles of freezing (in liquid nitrogen) and thawing (at 37 °C). The homogenates were then centrifuged (10 000 × g, at 4 °C, for 15 min) and supernatants were collected and stored at –80 °C until further analysis.

Protein content analysis

Total protein concentrations in heart and mitochondrial homogenates, as well as in the cytoplasmic fraction, were determined using the Bradford method. Bovine serum albumin (BSA, heat shock fraction, ≥ 98%; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) was used as the protein standard. Protein concentration was measured with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) using a Spark multimode microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Männedorf, Switzerland).

mRNA expression measurement

Total RNA was isolated from heart tissue using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. 2 µg of purified RNA were reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). The expression of the following genes: B-cell lymphoma protein 2–associated X (BAX), B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (BCL2), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, housekeeping gene) was analyzed by relative quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using a CFX96 Touch system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). The 5’–3’ sequences of forward and reverse primers are listed in Table 1. The qRT-PCR reaction mixture consisted of iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA), forward and reverse primers at a final concentration of 0.1 µM, UltraPure DEPC-Treated water (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and 100 ng of cDNA in a final volume of 30 µL per well. Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated using the 2–ΔCt method, normalized to GAPDH.

MMP-2 protein concentration analysis

MMP-2 protein concentrations in mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions was quantitatively measured using the Quantikine ELISA Assay for Total MMP-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The total MMP-2 Quantikine ELISA Assay detects recombinant MMP-2, as well as native human, mouse, rat, porcine, and canine active, pro-, and TIMP-complexed forms of MMP-2. The minimum detectable dose of the assay is 0.033 ng/mL. Protein concentration was expressed as ng of MMP-2 per µg of total protein.

Assessment of NTT-MMP-2 protein activity

NTT-MMP-2 activity in mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions was measured using a gelatin zymography protocol developed by Heussen and Dowdle and modified in our laboratory27,28. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions (30 µL) were mixed with 4 × Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) at a ratio of 4:1. Samples were then loaded onto an 8% polyacrylamide gel copolymerized with gelatin (2 mg/mL) and SDS (0.1%) under denaturing, non-reducing conditions, followed by electrophoresis. Subsequently, gels were rinsed in 2.5% Triton X-100 to remove SDS and incubated in an incubation buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5; 5 mM CaCl2; 200 mM NaCl; and 0.05% NaN3) at 37 °C for 18 h. After gelatin digestion by metalloproteinases, gels were stained with 0.5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in 30% methanol and 10% acetic acid for 2 h, and subsequently destained in 30% methanol and 10% acetic acid until clear bands were visible. NTT-MMP-2 activity was visualized as dark bands on a bright background. RPP and HT10-80 cell lines were used as positive controls. Zymograms were scanned using a GS-800 Calibrated Densitometer (model PowerLook 2100 XL-USB). Quantity One version 4.6.9 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) was used to analyze the results. The relative activity of NTT-MMP-2 was quantified and expressed in arbitrary units (AU) as enzyme activity per µg of total protein. The 65 kDa gelatinolytic band detected in our mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions was referred to as NTT-MMP-2 based on its apparent molecular weight and previous literature.

LDH activity measurement

The Lactate Dehydrogenase Activity Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) was used to assess LDH activity in coronary effluents, following the manufacturer’s instructions. LDH, a stable cytoplasmic enzyme, serves as a marker of cell injury, as it is released from the cytosol during membrane permeability/damage or cell lysis. LDH level in coronary effluents was normalized to CF [mL/min], as CF varied during ischemia and reperfusion.

Oxidative status in rat hearts

The OxiSelect™ In Vitro ROS/RNS Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, California, USA) was used to assess total ROS/RNS levels in heart homogenates. The assay is designed to measure total ROS and RNS, including hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide, peroxyl radicals, and peroxynitrite anion. The test is based on the action of dichlorodihydrofluorescin DiOxyQ (DCFH-DiOxyQ), a proprietary fluorogenic probe that is primed with a dequenching reagent to the highly reactive DCFH form. DCFH is rapidly oxidized to the highly fluorescent DCF in the presence of ROS and RNS29.

Cytochrome c concentration analysis

Cytochrome c content was measured in mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions using a Rat Cyt-C ELISA Kit (FineTest, Wuhan, Hubei, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The minimum detectable concentration was 0.391 ng/mL. Protein concentration was expressed as ng per µg of total protein.

Nuclear Factor – κB concentration measurement

NF-κB concentration in cytoplasmic fractions was measured using the Rat Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) ELISA Kit (Cusabio, Houston, Texas, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The minimum detectable concentration was 1.56 pg/mL. Protein concentration was expressed as pg per µg of total protein.

Assessment of nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1) concentration

The Rat NFATc1 ELISA Kit (Biomatik, Wilmington, Delaware, USA) was used to measure NFATc1 content in the cytoplasmic fraction of hearts. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The minimum detectable concentration was 31.25 pg/mL. Protein concentration was expressed as pg per µg of total protein.

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) content analysis

The Rat Interleukin 6 ELISA Kit (Cusabio, Houston, Texas, USA) was used to assess IL-6 concentration in cytoplasmic fractions, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The minimum detectable contcentration was 0.312 pg/mL. IL-6 concentration was expressed as pg per µg of total protein.

Statistical analysis of the results

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Normality of variance was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For comparisons between multiple groups, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test or the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Dunn’s post-hoc test was used, as appropriate. Correlations were assessed using Pearson’s or Spearman’s test, depending on data distribution. Results are presented as mean ± SEM and were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. A near-significant trend was noted for p values between 0.05 and 0.07. The sample size (N) was 6–9 per group.

Results

An effect of siRNA on recovery, injury and MMP-2 synthesis in heart tissue

To explore changes in heart mechanical function recovery, tissue injury and MMPs protein synthesis under the influence of MMP-2 siRNA, we measured RPP recovery, LDH activity in extracellular space and MMP-2 protein level. Recovery of heart mechanical function was significantly decreased in I/R hearts compared to aerobically perfused organs, both with and without MMP-2 siRNA (p = 0.001 and p = 0.006) (Fig. 2). To check if MMP-2 siRNA did not induce tissue injury itself, we perfused hearts in aerobic conditions with the administration of MMP-2 siRNA—the hemodynamic parameters were not significantly different from the aerobic control, confirming no harmful effects. Perfusion of hearts subjected to I/R with MMP-2 siRNA resulted in increased recovery of the heart mechanical function (p = 0.003), and administration of scrambled RNA did not affect I/R recovery.

MMP-2 and MMP-9 synthesis were significantly increased in rat hearts subjected to I/R (without and with scrRNA (p = 0.008 and p = 0.001, p = 0.0001), confirming that oxidative stress induces matrix metalloproteinase synthesis. An infusion of siRNA significantly reduced MMP-2 and MMP-9 tissue content (p = 0.002 and p = 0.021).

NTT-MMP-2 and MMP-2 synthesis and activity during I/R

I/R induced an increase in total MMP-2 concentration in the cytoplasmic fraction of I/R hearts compared to the Aero group (p = 0.03) (Fig. 3E). Data also showed increased activity of NTT-MMP-2, but no elevation in the activity of pro-MMP-2 or total MMP-2 in mitochondrial fractions (p < 0.0001, p = 0.78, and p = 0.86 respectively; Fig. 3B–D). Treatment with MMP-2 siRNA decreased MMP-2 synthesis (p = 0.06) (Fig. 3A) and NTT-MMP-2 activity (p = 0.005) (Fig. 3B) in the mitochondrial fraction. In cytoplasmic fraction, NTT-MMP-2 activity was highest in the I/R + siRNA group (Fig. 3F), whereas MMP-2 and pro-MMP-2 activities did not differ significantly between groups (Fig. 3G–H). Representative zymogram of MMPs activities in heart homogenates is shown in Fig. 3I.

MMP-2 concentration in mitochondrial (A) and cytoplasmic (E) fractions. Activity of NTT-MMP-2 (B,F), total MMP-2 (C,G) and pro-MMP-2 (D,H) in mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions. Representative zymogram of MMPs activities in heart homogenates (I). HT10-80 was used as standard for pro-/active MMP-2 and MMP-9.

Heart injury and mechanical function during I/R

Parameters reflecting cardiac mechanical function were substantially decreased after I/R (Table 2, Fig. 4A–C). Recovery of RPP was reduced by approximately 35% in the I/R group compared with aerobically perfused hearts (Fig. 4C). Mechanical function in hearts subjected to I/R and perfused with siRNA was significantly improved compared to the I/R group, with measured parameters approaching values observed in the aerobic control (Table 2, Fig. 4A–C).

Changes of heart rate (A) and RPP (calculated as the product of the heart rate and left ventricular developed pressure (heart rate x left ventricular developed pressure/1000)) (B) during the experiment. Recovery of heart mechanical function (difference between RPP at 25th and 77th min of perfusion expressed as a percentage of RPP recovery) (C). LDH activity in coronary effluents (D). Correlation between NTT-MMP-2 activity in mitochondrial fraction and LDH activity (E), and HR (F).*p < 0.05 Aero vs I/R, # p < 0.05 I/R vs I/R + siRNA.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, a marker of cell damage, was significantly increased in coronary effluents from the I/R group (p < 0.001), confirming cellular injury. Following siRNA administration, LDH activity decreased (p = 0.01; Fig. 4D). NTT-MMP-2 activity in the mitochondrial fraction positively correlated with LDH activity (p = 0.02, r = 0.46), indicating an association between heart injury and NTT-MMP-2 activity (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, NTT-MMP-2 activity in the mitochondrial fraction negatively correlated with HR (p = 0.02, r = –0.45), suggesting a detrimental effect of this protein on cardiac function (Fig. 4F).

Oxidative status in cardiomyocytes

ROS/RNS levels in heart homogenates were significantly increased after I/R (p = 0.04) and normalized in the I/R + siRNA group (p = 0.01) (Fig. 5A). ROS/RNS level positively correlated with NTT-MMP-2 activity (p = 0.02, r = 0.69) and LDH activity in coronary effluents (p = 0.02, r = 0.56), and negatively correlated with HR (p < 0.01, r = –0.68) and recovery of RPP (p = 0.02, r = –0.64), indicating an association between oxidative stress and cardiac injury (Fig. 5B–E).

Regulation of NF-κB/cytochrome c axis

Induction of NTT-MMP-2 during oxidative stress was accompanied by an increased concentration of NF-κB in the cytoplasm (p = 0.03; Fig. 6B). Both NTT-MMP-2 (p = 0.03, r = 0.67) and cytochrome c (p = 0.059, r = 0.40) positively correlated with NF-κB levels (Fig. 6A,E). As a likely consequence, increased levels of cytochrome c were observed in both mitochondrial (p = 0.02) and cytoplasmic (p < 0.01) fractions (Fig. 6C–D). The concentration of cytochrome c in the cytoplasmic fraction of the I/R group was 34.7% higher than in the Aero group (991.4 ± 68.5 vs 735.8 ± 44.1 ng/μg) and 1042% higher in the cytoplasmic fraction compared to the mitochondrial fraction (991.4 ± 68.5 vs 86.7 ± 5.2 ng/μg). The increased release of cytochrome c positively correlated with increased cellular injury (p = 0.05 r = 0.50) and negatively correlated with HR (p = 0.01, r = –0.61) and RPP (p < 0.01, r = –0.63) (Fig. 6F–H). Administration of MMP-2 siRNA led to decreased NF-κB level in the cytoplasmic fraction (p = 0.02) and cytochrome c level in the mitochondrial fraction (p = 0.05) (Fig. 6B–C).

Correlation of mitochondrial NTT-MMP-2 and NF-κB concentration in cytoplasm (A); Cytoplasmic concentration of NF-κB (B); Cytochrome c level in mitochondrial (C) and cytoplasmic (D) fractions. Correlation of cytochorme c in mitochondrial fraction and NF-κB (E), LDH as a marker of injury (F), HR (G) and RPP (H).

The expression of pro- and antiapoptotic genes under IRI

The expression of BAX and BCL2 genes in hearts subjected to I/R did not differ significantly between study groups (Fig. 7A,C). Furthermore, cytoplasmic NF-κB content did not correlate with the expression of either BAX and BCL2 genes (p > 0.05) (Fig. 7B,D).

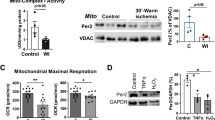

Immune response: NFATc1 activation and IL-6 production

NFATc1 concentration in the cytoplasmic fraction was increased after I/R (with and without siRNA treatment) compared to the aerobic control (p < 0.05; Fig. 8A). The cytoplasmic IL-6 level did not change significantly after I/R alone; however, a significant increase was observed following siRNA administration (p = 0.02). Moreover, IL-6 concentration strongly correlated with NFATc1 concentration (r = 0.79, p = 0.003) (Fig. 8B–C).

Discussion

Previously published studies have shown that different MMP-2 isoforms exert heterogeneous effects on heart muscle. Full-length MMP-2 can degrade ECM compotents as well as structural proteins within sarcomeres, particularly troponin I8,19. Hypoxia and oxidative stress conditions can activate an alternative promoter in the MMP-2 gene, leading to the expression of a shortened 65 kDa isoform of MMP-2. One hypothesis explaining this mechanism suggests the involvement of DNA methylation17. Moreover, genomic databases provide no evidence for alternative splicing of MMP-2 transcript as a mechanism for generating the 65 kDa isoform18, making promoter activation the most plausible explanation so far. NTT-MMP-2 differs functionally and structurally from FL-MMP-2 and may contribute to cardiac hypertrophy and failure17,18. In preliminary studies using NTT-MMP-2 transgenic mice, more severe cardiac damage was observed following I/R, and this isoform contributed to the progression of inflammation, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and contractile dysfunction. Importantly, the observed impairment in cardiac function was associated with disrupted calcium ion flux, rather than reduced myofilament strength as seen with FL-MMP-2. These findings highlight distinct pathomechanisms of the two MMP-2 isoforms, each influencing different intracellular pathways8. Overexpression of NTT-MMP-2 has also been linked to oxidation disorders, including those resulting from hyperglycemia9. In diabetic cardiomyopathy, NTT-MMP-2 expression was observed outside mitochondria, within the Z line and cell nuclei, indicating its involvement in the pathogenesis of primary functional and structural cardiac alterations induced by chronic hyperglycemia9. Additionally, NTT-MMP-2 has been shown to induce renal tubular necrosis during I/R via inflammation and fibrosis of renal tissue30. It is well documented that oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and aging significantly influence NTT-MMP-2 activity. Studies in mice have shown that NTT-MMP-2 activity increases with age31. Increased expression of this isoform has been associated with systolic failure due to necrosis and inflammation of cardiomyocytes occurring in atherosclerosis and accompanying MI. The proteolytic activity of NTT-MMP-2 correlates with the extent of mitochondrial damage. This is related to the localization of the enzyme inside the organelles in the heart, especially in the subsarcolemmal space18.

The present study focuses on the role of NTT-MMP-2 under oxidative stress conditions induced by ischemia–reperfusion in cardiac muscle, and its association with mitochondrial–nuclear signaling, as well as the activation of inflammatory and cardiomyocyte death pathways. Additionally, we propose a pharmacological approach to mitigate its effects, aiming to achieve cardioprotection.

The study demonstrated that oxidative stress, manifested by increased ROS/RNS production during ischemia–reperfusion, was associated with increased NTT-MMP-2 (65 kDa) activity in the mitochondrial fraction of cardiac cells, corresponding to enhanced cardiac injury. It is necessary to mention, that 65 kDa gelatinolytic band detected in our mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions was referred to as NTT-MMP-2 based on its apparent molecular weight and previous literature. Since gelatin zymography does not allow definitive distinction between MMP-2 isoforms, therefore, the 65 kDa band observed in our mitochondrial preparations was interpreted as the N-terminal truncated MMP-2 (NTT-MMP-2) based on its molecular weight, mitochondrial localization, induction by ischemia/reperfusion, and correlation with NF-κB and NFAT signaling pathways. However, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that this band represents a proteolytic fragment or an alternatively processed form of full-length MMP-2. Future studies using isoform-specific antibodies or transcript-level analysis would be required for unequivocal identification”. The group led by R. Schulz confirmed the localization of MMP-2 in the mitochondria-associated membrane of the heart. They also showed that hypoxia–reoxygenation and I/R injury involve increased peroxynitrite biosynthesis, which can activate MMPs localized in or near mitochondria, thereby contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction32. Results indicate a complex interplay between ROS and NTT-MMP-2. Inhibition of NTT-MMP-2 led to a reduction in ROS production, suggesting that NTT-MMP-2 activity contributes to ROS generation. Conversely, previous studies and our mechanistic considerations indicate that elevated ROS can activate NTT-MMP-2 through redox-sensitive signaling pathways33,34. Together, these observations support the existence of a positive feedback loop, in which ROS promotes NTT-MMP-2 activation, which in turn further amplifies ROS production, contributing to oxidative stress during I/R injury. Activation of mitochondrial MMP-2 has been shown to accelerate apoptosis of retinal capillary cells in diabetes by damaging mitochondria through modulation of HSP60 and connexin 43, facilitating cytochrome c release and activation of the apoptotic cascade35. The specific mitochondrial induction of NTT-MMP-2 observed in this study is likely a consequence of transient oxidative stress, which inhibits mitochondrial respiration and induces NTT-MMP-2 formation2,19,31,36. Previous studies have also demonstrated that MMP-2 NTT50 is upregulated in response to oxidative stress, enhancing the degradation of intracellular MMP-2 substrates37. In another study, MMP-2 NTT76 was expressed in cardiomyocytes under oxidative stress and induced a primary innate immune response, cardiac hypertrophy, and inflammation19. However, the precise mechanism underlying the localization of MMP-2 and its NTT forms to mitochondria and the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) remains unclear. Our results demonstrate that MMP-2 siRNA may exert compartment-specific effects on NTT-MMP-2 activity. While mitochondrial NTT-MMP-2 activity was reduced, cytoplasmic NTT-MMP-2 activity increased following siRNA treatment. This suggests that the cardioprotective effects of MMP-2 silencing cannot be attributed solely to inhibition of NTT-MMP-2, but rather result from a combination of isoform- and compartment-specific modulation of MMP-2 activity and downstream signaling pathways. These findings highlight the complexity of MMP-2 regulation during I/R injury and underscore the importance of considering subcellular localization when interpreting functional outcomes.

Data published by de Oliveira Cruz et al. demonstrated that NTT-MMP-2 transcripts and the 65 kDa isoform are induced by redox stress through activation of a latent promoter located within the first intron of the MMP-2 gene17,18. This highlights a fundamental difference between the activation mechanisms of FL-MMP-2 and NTT-MMP-2. FL-MMP-2 is directly activated by oxidative stress, whereas NTT-MMP-2 undergoes transcriptional activation and expression in response to redox stimuli17. In our study small amounts of the NTT-MMP-2 isoform were detected in both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions under physiological (aerobic) conditions, confirming its low-level constitutive production. However, the causal relationship between NTT-MMP-2 and oxidative stress remains controversial. For instance, Cerol et al. reported that NTT-MMP-2 expression in tubular epithelial cells induced mitochondrial ROS production, as NTT-MMP-2-mediated loss of mitochondrial membrane permeability disrupted oxidative phosphorylation, enhancing mitochondrial ROS generation31. Similarly, Bassiouni et al. showed that MMP-2 activity is upregulated during myocardial I/R injury with induction of NTT-MMP-2 expression as a part of the inflammasome response, leading to impaired mitochondrial respiratory chain function and contractile dysfunction. They also identified mitofusin-2 as a proteolytic target of MMP-236. The NTT-MMP-2 isoform is enzymatically active but remains localized intracellularly, within or near mitochondria, due to the absence of the secretory (signal) sequence18. A signal sequence typically directs proteins to the secretory pathway, leading to extracellular secretion. Here, the lack of signal sequence retains NTT-MMP-2 within mitochondria, contributing to intracellular proteolytic activity. In our study, increased activity of 65 kDa MMP-2 in the mitochondrial fraction correlated with elevated cellular injury, as indicated by increased LDH activity in extracellular space. Furthermore, increased NTT-MMP-2 activity during cardiac IRI was associated with functional impairments, including reduced HR, LVDP, CF, and RPP, confirming cardiac dysfunction. The negative correlation between HR and NTT-MPP-2 activity suggests that reduced cardiac contractility is associated with increased intracellular NTT-MMP-2 activity. Similar findings were reported by Lee et al., where NTT-MMP-2 expression positively correlated with mitochondrial damage and reduced LV systolic function9. Collectively, these observations reinforce the established concept that excessive ROS/RNS production causes a redox imbalance that plays an important role in cell damage and necrosis38,39,40. Given that ROS are naturally generated during oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria as byproducts of oxygen metabolism41,42, our results support the view that cardiac damage and dysfunction during I/R result from excessive ROS/RNS production, coupled with the proteolytic activity of mitochondrial NTT-MMP-2.

As the next step, we aimed to attenuate the above-described detrimental process through targeted pharmacotherapy. Lin et al. demonstrated that MMP-2 siRNA transfection preserved cardiomyocyte contractility during I/R injury, with the protective effect associated with increased levels of MLC1 and MLC243. Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of MMP-2 activity has been shown to reduced left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction44,45. In the present study, MMP-2 siRNA treatment decreased both MMP-2 synthesis and NTT-MMP-2 activity in the mitochondrial fraction, exerting a protective effect on cardiac mechanical function. Since neither pro-MMP-2 nor MMP-2 activity in cytoplasmic or mitochondrial fractions changed significantly during I/R in this model, siRNA had no measurable impact on these forms. We also demonstrated that total MMP-2 concentration in the cytoplasmic fraction was significantly higher in the I/R group compared to the aerobic control; however, these findings did not parallel activity results. It is important to note that the metalloproteinase activity does not necessarily correspond to protein concentration. MMPs are present in both proenzyme and active forms, which can be distinguished by gelatin zymography based on molecular weight. Due to the specificity of this technique – where SDS induces partial activation without cleaving the prodomain – both pro-MMP and active forms display gelatinolytic activity. Therefore, concentration measurements reflect all molecules sharing a given antigenic determinant, including enzymatically inactive species46.

Previous studies on the clinical significance of NTT-MMP have highlighted its multifunctional role. Cardiac-specific NTT-MMP-2 transgenic mice developed progressive cardiomyocyte and ventricular hypertrophy, inflammation, systolic dysfunction, and increased susceptibility to IRI, ultimately leading to systolic heart failure17,19. In the kidneys of transgenic mice, I/R injury triggered enhanced expression of innate immunity genes and the release of damage-associated molecular patterns, resulting in tubular epithelial necrosis, mitochondrial permeability transition, mitophagy, fibrosis, inflammation, and impaired renal function17,31,47. NTT-MMP-2 was also shown to induce a sustained systemic inflammatory response following I/R injury. Specifically, the kidneys of NTT-MMP- 2 transgenic mice exhibited elevated expression of OAS-1 (2′-5′-oligoadenylate synthetase), IRF-7 (interferon regulatory factor 7), and CXCL-10 (C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10), contributing to the systemic inflammatory response31. Furthermore, Bassioumi et al. demonstrated that MMP-2 proteolyzes Mfn-2 during myocardial I/R injury, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and amplifying the inflammasome response36.

Since oxidative stress during I/R induces elevated expression of the truncated 65 kDa isoform of NTT-MMP-2, and given that NTT-MMP-2 can activate stress signaling molecules in the cell nucleus – such as NF-κB and NFAT)12 – which contribute to inflammatory and pro-apoptotic responses, we aimed to investigate this issue in a cardiac I/R injury model. NF-κB, a family of transcription factors, is typically retained in an inactive state in the cytoplasm and translocates to the nucleus upon stimulation. Cellular stimulation leads to rapid phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation of IκB, releasing NF-κB to enter the nucleus and initiate transcriptional activity48. The NF-κB signaling pathway is highly sensitive to redox balance and plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of cardiac I/R injury. It is well documented that NF-κB regulates the expression of genes involved in cardiomyocyte apoptosis, inflammasome activation, and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α36. During myocardial ischemia, it promotes inflammation and exacerbates cardiac damage. Inhibition of NF-κB p65 phosphorylation, achieved by silencing the PCAF (P300/CBP-associated factor) transcription coactivator, confers cardioprotection in a rat model of I/R49. Moreover, the p65 ribozyme can prevent apoptosis in cells exposed to H2O2, associated with an autophagic response that balances apoptosis and may be depend on modulation of the NF-κB pathway50. NF-κB activity during I/R is further modulated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways, which act as upstream and regulatory factors. In response to oxidative stress, JNK expression and NF-κB activation increase, promoting inflammation and cell injury, whereas AMPK inhibits JNK and exerts protective effect during I/R. The interplay between AMPK, JNK, and NF-κB pathways in response to oxidative stress has been observed in rat models of myocardial I/R injury51.

We confirmed that elevated levels of NTT-MMP-2 in mitochondria were accompanied by increased synthesis of NF-κB. We also observed a significantly higher concentration of cytochrome c in both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions during I/R. Notably, increased cytochrome c production in mitochondria was associated with enhanced NF-κB synthesis. Elevated cytochrome c in the cytoplasmic fraction suggests that NTT-MMP-2 promotes mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release – key events in the activation of the apoptotic cascade. Physiologically, cytochrome c acts as an electron carrier between complexes III and IV of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Once released into the cytoplasm, it participates in apoptosome formation and activates caspases, leading to cell apoptosis52. A positive correlation between cytochrome c levels and markers of cell injury, along with a negative correlation with HR and RPP indicates its involvement in cardiac dysfunction during I/R. Direct evidence for this mechanism is provided by the inhibition of mitochondrial NTT-MMP-2 using siRNA, which attenuated mitochondrial damage and heart mechanical dysfunction. It also affected the expression of transcription factor Nf-κB and cytochrome c in mitochondria. However, analysis of pro- and anti-apoptotic factors BAX and BCL2 did not reveal a significant contribution to heart injury or failure in our model. Physiologically, BCL2 is located on the outer membrane of mitochondria and promotes cell survival and preventing apoptosis. Conversely, BAX is a pro-apoptotic protein that promotes permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane, facilitating the release of cytochrome c and ROS. In the presented model of I/R injury, neither BAX nor BCL2 mRNA expression was induced, and no correlation with NF-κB was observed. Consequently, MMP-2 siRNA did not demonstrate any therapeutic effect through this pathway, warranting further investigation.

The NF-κB family of transcription factors is distantly related to NFAT. Within the immune system, members of the NFAT family play a crucial role in antigen-induced gene transcription53. NFAT activation occurs via Ca2+-regulated calcineurin, which promotes nuclear localization of NFAT transcription complexes54. NFAT is essential for the inflammatory response by selectively inducing the transcription of inflammatory mediator genes. Hence, it stimulates the production of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α55,56. Nevertheless, the current study confirmed that oxidative stress during I/R induced the expression of stress-related signaling molecules including NFATc1. Furthermore, increased NFATc1 levels correlated positively with IL-6 production. Interestingly, siRNA treatment further enhanced the production of both NFATc1 and IL-6, suggesting a deepened innate immunity response during IRI. These findings indicate that NTT-MMP-2 in not the sole factor initiating the inflammatory response in cardiac I/R model; other parallel mediators are likely involved. Joshi et al. also showed that during cardiac IRI, NTT-MMP-2 triggers mitochondrial and nuclear stress signaling via transcription factors NF-κB and NFAT, inducing markers of innate immunity57. This confirms our data. However, we showed that partial inhibition of NTT-MMP-2 did not alleviate the inflammatory process. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine with a wide range of effects, from an acute, largely protective response to chronic signaling that can lead to pathogenic inflammation and autoimmunity58,59. It is therefore important to remember that IL-6 is also a prognostic marker associated with left ventricular contractile dysfunction and heart failure60,61. On the other hand, IL-6 activates several signaling pathways that mediate delayed ischemic preconditioning and promote the expression of anti-apoptotic molecules in T cells62,63. Smart et al. revealed that IL-6 induces a PI3-kinase (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) and NO-dependent cardioprotection, which is associated with altered mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, reduced reperfusion-induced mitochondrial depolarization, prevention of swelling and structural damage, and suppression of cytosolic Ca2+ transients64. Acutely, IL-6 family cytokines protect cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress by initiating an anti-apoptotic signaling and reducing infarct sizes in MI58,65. Similarly in our study, further increase in IL-6 after NTT-MMP-2 inhibition was associated with reduced cardiac damage and improved mechanical function. Therefore, IL-6 upregulation following siRNA administration may reflect a compensatory mechanism aimed at cardioprotection. A more significant inducer of NFATc1 in current I/R heart model may be ROS/RNS, as ROS production itself activates NFAT3 in the kidney, and its overexpression affects caspases-dependent cell death pathways66. Additionally, hypoxia increases the NFAT5 concentration and triggers its transcriptional activity. Reduction of its activity in kidneys subjected to 8-h hypoxia resulted in increased caspase-3 expression, apoptosis and necrosis in the tissue, suggesting a protective effect in this organ67. Overall, our study identifies NTT-MMP-2 as a promising therapeutic target in ischemic heart disease, with siRNA treatment partially mitigating I/R injury via effects on mitochondrial stress and apoptosis.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, the relatively small sample size reduces statistical power, which may suggest trends rather than allow for definitive conclusions. Second, the ex vivo Langendorff isolated heart model, while providing a controlled environment, does not fully replicate in vivo physiological or systemic conditions, such as neurohumoral regulation or immune responses. The 65 kDa gelatinolytic band detected in our mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions was referred to as NTT-MMP-2 based on its apparent molecular weight and previous literature. However, we acknowledge that, in the absence of transcript-level analysis or isoform-specific expression data, this band cannot be conclusively identified as the truncated NTT-MMP-2 isoform rather than a proteolytic fragment of full-length MMP-2. Furthermore, although correlations between NTT-MMP-2, cytochrome c, and NF-κB were observed, the direct causative pathways were not fully elucidated. Further studies using genetic knock-out models or specific inhibitors of signaling pathways are planned to further clarify these relationships.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AMPK:

-

AMP-activated protein kinase

- AU:

-

Arbitrary units

- BAX:

-

B-cell lymphoma protein 2–associated X

- BCL2:

-

B-cell lymphoma protein 2

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- CF:

-

Coronary flow

- CXCL-10:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10

- DCFH:

-

Dichlorodihydrofluorescein

- DEPC treated water:

-

Diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water

- ECM:

-

Extracellular matrix

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FL-MMP-2:

-

Full-length matrix metalloproteinase 2

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- HSP:

-

Heat shock protein

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- i.p.:

-

Intraperitoneal

- IRF:

-

Interferon regulatory factor

- IRI:

-

Ischemia–reperfusion injury

- JNK:

-

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MAM:

-

Mitochondrial-associated membrane

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MLC1:

-

Myosin light chain 1

- NFAT:

-

Nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor κB

- LVDP:

-

Left ventricular developed pressure

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NTT:

-

N-terminally truncated

- OAS:

-

2′-5′-Oligoadenylate synthetase

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCAF:

-

P300/CBP-associated factor

- PI 3-kinase:

-

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- RPP:

-

Rate pressure product

- SDS:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TIMP:

-

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

References

Chan, B. Y. H. et al. Doxorubicin induces de novo expression of N-terminal-truncated matrix metalloproteinase-2 in cardiac myocytes. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 96, 1238–1245 (2018).

Laronha, H. & Caldeira, J. Structure and function of human matrix metalloproteinases. Cells 9, 1076 (2020).

Cui, N., Hu, M. & Khalil, R. A. Biochemical and biological attributes of matrix metalloproteinases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 147, 1–73 (2017).

Fischer, T., Senn, N. & Riedl, R. Design and structural evolution of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Chem. A Eur. J. 25, 7960–7980 (2019).

Tallant, C., Marrero, A. & Gomis-Rüth, F. X. Matrix metalloproteinases: Fold and function of their catalytic domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 20–28 (2010).

Mannello, F. & Medda, V. Nuclear localization of matrix metalloproteinases. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 47, 27–58 (2012).

Rangasamy, L. et al. Molecular imaging probes based on matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (MMPIs). Molecules 24, 2982 (2019).

Lovett, D. H. et al. A N-terminal truncated intracellular isoform of matrix metalloproteinase-2 impairs contractility of mouse myocardium. Front. Physiol. 5, 363 (2014).

Lee, H. W. et al. Enhanced cardiac expression of two isoforms of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in experimental diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 14, e0221798 (2019).

Wang, W. et al. Intracellular action of matrix metalloproteinase-2 accounts for acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Circulation 106, 1543–1549 (2002).

Sawicki, G. et al. Degradation of myosin light chain in isolated rat hearts subjected to ischemia-reperfusion injury: A new intracellular target for matrix metalloproteinase-2. Circulation 112, 544–552 (2005).

Ali, M. A. M. et al. Titin is a target of matrix metalloproteinase-2: Implications in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 122, 2039–2047 (2010).

Sung, M. M. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 degrades the cytoskeletal protein α-actinin in peroxynitrite mediated myocardial injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 43, 429–436 (2007).

Kwan, J. A. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) is present in the nucleus of cardiac myocytes and is capable of cleaving poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in vitro. FASEB J. 18, 690–692 (2004).

Viappiani, S. et al. Activation and modulation of 72kDa matrix metalloproteinase-2 by peroxynitrite and glutathione. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77, 826–834 (2009).

Jacob-Ferreira, A. L. & Schulz, R. Activation of intracellular matrix metalloproteinase-2 by reactive oxygen-nitrogen species: Consequences and therapeutic strategies in the heart. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 540, 82–93 (2013).

de Cruz, J. O. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the N-terminal truncated isoform of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (NTT-MMP-2) and its presence in renal and cardiac diseases. Front. Genet. 12, 637148 (2021).

Lovett, D. H. et al. A novel intracellular isoform of matrix metalloproteinase-2 induced by oxidative stress activates innate immunity. PLoS ONE 7, e34177 (2012).

Lovett, D. H. et al. N-terminal truncated intracellular matrix metalloproteinase-2 induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, inflammation and systolic heart failure. PLoS ONE 8, e68154 (2013).

Mitochondrial protein import: from transport pathways to an integrated network | Elsevier Enhanced Reader. https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0968000411001873?token=B50BB258233F691ACA33A771C777E518FB15D99574810BEC0BDE0CC463FFA231602082A6D56726216FA97C179E84017Dhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.004.

Kriechbaumer, V., von Löffelholz, O. & Abell, B. M. Chaperone receptors: Guiding proteins to intracellular compartments. Protoplasma 249, 21–30 (2012).

Stellas, D., El Hamidieh, A. & Patsavoudi, E. Monoclonal antibody 4C5 prevents activation of MMP2 and MMP9 by disrupting their interaction with extracellular HSP90 and inhibits formation of metastatic breast cancer cell deposits. BMC Cell Biol. 11, 51 (2010).

Wanga, S. et al. Two distinct isoforms of matrix metalloproteinase-2 are associated with human delayed kidney graft function. PLoS One 10, e0136276 (2015).

Lindsey, M. L. et al. Guidelines for experimental models of myocardial ischemia and infarction. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 314, H812–H838 (2018).

Bøtker, H. E. et al. Practical guidelines for rigor and reproducibility in preclinical and clinical studies on cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 113, 39 (2018).

Krzywonos-Zawadzka, A. et al. Cardioprotective effect of MMP-2-inhibitor-NO-donor hybrid against ischaemia/reperfusion injury. J. Cell Mol. Med. 23, 2836–2848 (2019).

Heussen, C. & Dowdle, E. B. Electrophoretic analysis of plasminogen activators in polyacrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulfate and copolymerized substrates. Anal. Biochem. 102, 196–202 (1980).

Biały, D. et al. Low frequency electromagnetic field decreases ischemia–reperfusion injury of human cardiomyocytes and supports their metabolic function. Exp. Biol. Med. 243, 809–816 (2018).

Olejnik, A., Krzywonos-Zawadzka, A., Banaszkiewicz, M. & Bil-Lula, I. Ameliorating effect of klotho protein on rat heart during I/R injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 1–11 (2020).

Rhee, H. et al. The expression of two isoforms of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in aged mouse models of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 37, 222–229 (2018).

Ceron, C. S. et al. An intracellular matrix metalloproteinase-2 isoform induces tubular regulated necrosis: Implications for acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 312, F1166–F1183 (2017).

Hughes, B. G., Fan, X., Cho, W. J. & Schulz, R. MMP-2 is localized to the mitochondria-associated membrane of the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 306, H764-770 (2014).

Prado, A. F., Batista, R. I. M., Tanus-Santos, J. E. & Gerlach, R. F. Matrix metalloproteinases and arterial hypertension: role of oxidative stress and nitric oxide in vascular functional and structural alterations. Biomolecules 11, 585 (2021).

Prado, A. F. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2-induced epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation impairs redox balance in vascular smooth muscle cells and facilitates vascular contraction. Redox Biol. 18, 181–190 (2018).

Mohammad, G. & Kowluru, R. A. Novel role of mitochondrial matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 3832–3841 (2011).

Bassiouni, W., Valencia, R., Mahmud, Z., Seubert, J. M. & Schulz, R. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 proteolyzes mitofusin-2 and impairs mitochondrial function during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 118, 29 (2023).

Ali, M. A. M. et al. Mechanisms of cytosolic targeting of matrix metalloproteinase-2. J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 3397–3404 (2012).

Asimakis, G. K., Lick, S. & Patterson, C. Postischemic recovery of contractile function is impaired in SOD2+/− but not SOD1+/− mouse hearts. Circulation 105, 981–986 (2002).

Yoshida, T., Maulik, N., Engelman, R. M., Ho, Y.-S. & Das, D. K. Targeted disruption of the mouse sod I gene makes the hearts vulnerable to ischemic reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 86, 264–269 (2000).

Giordano, F. J. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 500–508 (2005).

Davies, K. Oxidative stress: The paradox of aerobic life. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 61, 1–31 (1995).

Ide, T. et al. Mitochondrial electron transport complex I is a potential source of oxygen free radicals in the failing myocardium. Circ. Res. 85, 357–363 (1999).

Lin, H.-B. et al. Inhibition of MMP-2 expression with siRNA increases baseline cardiomyocyte contractility and protects against simulated ischemic reperfusion injury. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 810371 (2014).

Peterson, J. T. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition attenuates left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in a rat model of progressive heart failure. Circulation 103, 2303–2309 (2001).

King, M. K. et al. Selective matrix metalloproteinase inhibition with developing heart failure. Circ. Res. 92, 177–185 (2003).

Bais, R. & Panteghini, M. Principles of Clinical Enzymology. In Tietz Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry (Saunders Elsevier, 2008).

Cheng, S., Pollock, A. S., Mahimkar, R., Olson, J. L. & Lovett, D. H. Matrix metalloproteinase 2 and basement membrane integrity: A unifying mechanism for progressive renal injury. FASEB J. 20, 1898–1900 (2006).

Ghosh, S., May, M. J. & Kopp, E. B. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: Evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 225–260 (1998).

Qiu, L. et al. Downregulation of p300/CBP-associated factor inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis via suppression of NF-κB pathway in ischaemia/reperfusion injury rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 10224–10235 (2021).

Han, M. et al. Overexpression of IκBα in cardiomyocytes alleviates hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis and autophagy by inhibiting NF-κB activation. Lipids Health Dis. 19, 150 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. Activation of AMPK inhibits inflammatory response during hypoxia and reoxygenation through modulating JNK-mediated NF-κB pathway. Metabolism 83, 256–270 (2018).

Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria | Cell Death & Differentiation. https://www.nature.com/articles/4401950.

Crabtree, G. R. Generic signals and specific outcomes: Signaling through Ca2+, calcineurin, and NF-AT. Cell 96, 611–614 (1999).

Crataegus laevigata Suppresses LPS-Induced Oxidative Stress during Inflammatory Response in Human Keratinocytes by Regulating the MAPKs/AP-1, NFκB, and NFAT Signaling Pathways - PMC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7914440/.

Mortlock, S.-A., Wei, J. & Williamson, P. T-cell activation and early gene response in dogs. PLoS ONE 10, e0121169 (2015).

Crabtree, G. R. & Olson, E. N. NFAT signaling: Choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell 109, S67–S79 (2002).

Joshi, S. K. et al. Novel intracellular N-terminal truncated matrix metalloproteinase-2 isoform in skeletal muscle ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Orthop. Res. 34, 502–509 (2016).

Fontes, J. A., Rose, N. R. & Čiháková, D. The varying faces of IL-6: From cardiac protection to cardiac failure. Cytokine 74, 62–68 (2015).

Kaplanski, G., Marin, V., Montero-Julian, F., Mantovani, A. & Farnarier, C. IL-6: A regulator of the transition from neutrophil to monocyte recruitment during inflammation. Trends Immunol. 24, 25–29 (2003).

Mooney, L. et al. Adverse outcomes associated with interleukin-6 in patients recently hospitalized for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ. Heart Fai.l 16, e010051 (2023).

Hanna, A. & Frangogiannis, N. G. Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as therapeutic targets in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 34, 849 (2020).

Narimatsu, M. et al. Tissue-specific autoregulation of the stat3 gene and its role in interleukin-6-induced survival signals in T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 6615–6625 (2001).

Teague, T. K. et al. Activation-induced inhibition of interleukin 6-mediated T cell survival and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 signaling. J. Exp. Med. 191, 915–926 (2000).

Smart, N. et al. IL-6 induces PI 3-kinase and nitric oxide-dependent protection and preserves mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 164–177 (2006).

Liu, Y., Zhang, D. & Yin, D. Pathophysiological effects of various interleukins on primary cell types in common heart disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6497 (2023).

Lin, H. et al. Activation of a nuclear factor of activated T-lymphocyte-3 (NFAT3) by oxidative stress in carboplatin-mediated renal apoptosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 161, 1661–1676 (2010).

Hao, S. et al. NFAT5 is protective against ischemic acute kidney injury. Hypertension 63, e46–e52 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Wroclaw Medical University Grant no. SUBZ.D010.25.020.

Funding

This work was supported by Wroclaw Medical University Grant no. SUBZ.D010.25.020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: IBL and MK; methodology: IBL, MK, and AKZ; investigation: ARP, MK, MN, SI, AK, KH, AO, AKZ, GS, GM and IBL; data analysis: MK, IBL; writing – original draft preparation: IBL, MK and ARP; writing—review and editing: ARP, IBL, GS; visualization: IBL and ARP; project administration: IBL; funding acquisition: IBL and GS; supervision: IBL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The investigation was conducted in accordance with the Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals published by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education and was approved by the local Ethics Committee for Experiments on Animals at the Ludwik Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wroclaw, Poland (Resolution 085/2020/P1 of 9th December 2020). The study is reported under the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org/). All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rak-Pasikowska, A., Kamińska, M., Niechciała, M. et al. siRNA-mediated inhibition of NTT-MMP-2 reduces oxidative stress and apoptotic signaling in an ex vivo model of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Sci Rep 16, 2968 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32875-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32875-1