Abstract

The development of modern particle accelerators such as FCC-ee requires improved energy efficiency. On the SRF cavity side, the intermetallic compound \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) is a promising alternative to niobium: its higher critical temperature (18.3 K) results into a BCS surface resistance at 4.5 K comparable to the one of Nb at 2 K, potentially allowing improved performance and reduced cryogenic costs while maintaining operation at 4.5 K. However, its brittleness makes bulk machining impractical, restricting its application to thin-film coatings. This study presents \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) thin films deposited on copper substrates via DCMS using a single stoichiometric target. The optimization of the deposition parameters via the evaluation of the critical temperature, morphology, elemental composition and crystalline structure of the films is outlined. A niobium buffer layer is implemented to prevent copper-tin interdiffusion, and plays a key role in the film quality. The results demonstrate \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited at \(\le\) \(650~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) on copper substrates pre-coated with a 30 µm niobium buffer layer which exhibit a critical temperature \(\ge\) 17 K. The RF test of a film deposited via the same recipe on a bulk Nb QPR sample yielded an RF surface resistance of 23 n\(\Omega\) at 4.5 K, 20 mT and 400 MHz. These findings open the way to a scalable approach to high-performance \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\)/Cu cavities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cryogenics is one of the major cost factors associated with the superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) systems in modern particle accelerators1. Due to its superconducting (SC) transition temperature (\(T_{\textrm{c}}\) = 18.3 K), twice as high as that of niobium (\(T_{\textrm{c}}\) = 9.2 K), the A15 compound Nb\(_{3}\)Sn has the potential to achieve quality factors \(Q_{0} > 10^{10}\) at the same operation temperature of the established Nb/Cu technology (4.5 K), which is more than twice as high as the one needed for bulk niobium (4.5 K versus 2 K), resulting in the reduction by approximately a factor three of grid power required for cryogenic cooling2. However, the intrinsic brittleness of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) makes its application in bulk form impractical, requiring its employment as a thin film deposited onto a substrate. The state of the art technique for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) cavity production is Vapor Tin Diffusion (VTD), which has demonstrated quality factors of \(10^{10}\) up to 20 MV \(\hbox {m}^{-1}\) at 4.4 K3. However, this technique is limited to bulk niobium cavities, eliminating the advantages of using copper for the main cavity structure. The coating of SRF copper cavities with a thin niobium layer via the physical vapor deposition (PVD) technique direct-current magnetron sputtering (DCMS) is a well-established practice, successfully implemented for LEP-II4 and LHC5. Nb/Cu cavities offer significant cost reduction for large-scale cavity production, due to the lower cost of copper compared to bulk niobium, as well as higher thermal conductivity at the targeted operational temperatures. Also, the copper substrate may open the way to alternative cooling methods beyond liquid helium, such as conduction cooling via cryocoolers, which have recently demonstrated a capacity of up to 9 W at 4.2 K6,7. Finally, \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) on Cu is of high interest for quantum sensing, particularly for dark matter search using haloscopes8,9,10,11,12.

This study presents the application of DCMS to the deposition of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films on copper, toward the optimization of the deposition recipe in terms of morphology, SC properties and radio-frequency (RF) performance. However, achieving the correct A15 phase of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) requires high temperatures (\(>~{930}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\)) to prevent the formation of spurious phases (Nb\(_{6}\)Sn\({}_{5}\), NbSn\({}_{2}\))13. This represents a challenge when using copper as a substrate, as its stress response transitions from the elastic to the plastic regime at about \({400}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\). In a study performed on 6 GHz elliptical copper cavity prototypes, the experimentally determined upper temperature limit before structural changes occur was observed to be approximately \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\)14. Another major challenge is Sn-Cu interdiffusion at the film-interface, which causes an imbalance in the stoichiometry (Nb:Sn ratio) and alters the SC properties of the film. Therefore, optimizing deposition parameters and implementing strategies to mitigate Sn-Cu interdiffusion are crucial aspects for achieving the correct \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) A15 phase on copper substrates.

The long-term objective of this research is to establish a scalable process for coating copper cavities with \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films that meet RF requirements. In the short term, the goal is to obtain films that exhibit:

-

1.

The correct A15 phase and stoichiometry, demonstrated by a \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) near 18.3 K, elemental analysis (EDS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements;

-

2.

A homogeneous, compact, and crack-free surface morphology, as these characteristics are essential for the film performance in RF environment, assessed via scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging of both the surface and the cross section.

According to the research strategy established in this study, these two conditions are baseline requirements for further engineering of the film toward its final application as an SRF cavity coating. In parallel, an additional goal must be pursued:

-

3.

Keeping the process temperature as low as possible, to ensure the process is scalable to large copper structures such as SRF cavities.

The \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) thin-film samples produced for this study were prepared following a standard routine, described later in the text. The films are 1 \({\upmu }\)m thick and deposited in argon atmosphere using a commercial, stoichiometric sputtering target as \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) source material. The employed substrates include sapphire, copper and copper pre-coated with a niobium buffer layer of varying thickness (from now on, these substrates are addressed as ’NbBL’, e.g. NbBL-1, NbBL-10, etc. denote a copper substrate pre-coated with a 1 \(\upmu\)m, 10 \(\upmu\)m, etc., Nb layer, respectively), and bulk niobium. The deposition process was initially followed by a 24 h annealing step. This annealing step was later eliminated, as discussed in the following Sections. After deposition, the samples are characterized by measuring their critical temperature, inspecting their surface and cross-section, analyzing their elemental composition and crystalline properties, and finally, measuring their RF surface resistance. To meet the conditions set by the short-term goals of this study, flat samples were used for deposition parameter optimization. The RF test was also conducted on a flat sample, whose geometry is customized for a quadrupole resonator (QPR) device15.

This work provides a comprehensive description of the R&D process established at INFN-LNL for optimizing the deposition recipe of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films on copper. The most relevant results on film quality and initial RF tests are presented. The effects of deposition temperature, annealing and NbBL thickness on the final properties of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film are discussed, along with the current lower limit found for the process temperature. The manuscript is structured as follows: after this Introduction, the Results Section presents the main achievements of this study. Finally, the Methods Section details the experimental setup employed for deposition, the sample production routine, and all characterization tools.

Results and discussion

Dependency of SC transition temperature and growth rate on the deposition parameters

Sputtering current and deposition pressure

At an early stage, the dependence of the deposition rate and of the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the films on the target current and process gas pressure was studied for samples deposited on sapphire substrate, used as reference for the later stages of the study. The deposition parameters for each run were selected based on their measured \(T_{\textrm{c}}\), and iteratively tuned until sufficient data was gathered to identify trends.

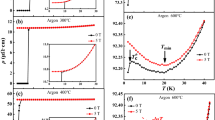

The dependence of the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) on the surface current density applied to the target was checked first, as the sputtering process was carried out in current-driven mode. The result is shown in Fig. 1a. These samples were deposited on sapphire at \({630}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) and annealed for 24 h at the same temperature. Two data sets are presented, corresponding to depositions carried out at two different argon pressures, \(2 \times 10^{-2}\) mbar and \(3 \times 10^{-3}\) mbar. In both cases, the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the samples are observed to degrade as the applied current increases. The set deposited at a higher pressure exhibits a systematically higher \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) compared to the set deposited at lower pressure.

Further insight in this regard was obtained by looking at the deposition rate as a function of the target surface current density, as shown by the data in Fig. 1b. Both the shown data sets are from samples deposited under the same conditions as the data presented in Fig. 1a. The linear fit of the low current data, indicated by the full line, is constrained to cross the axes origin. The dashed line extends from the fit line to visually highlight the separation of the higher current data from the low-current linear behavior. The data was line-fitted up to a current density value of 1.3 \(\hbox {mA cm}^{-2}\) (corresponding to a power density of 0.4 \(\hbox {W cm}^{-2}\)). This does not represent a hard current limit, but was taken as a conservative upper limit based on the available data.

Assuming that sputtering remains the only target material extraction mechanism during the deposition process (e.g. no thermal evaporation occurs), the deposition rate is generally expected to increase linearly with the current density16. However, tin is a low-melting-point material, likely to introduce a thermal evaporation component to the process. For low currents, thermal evaporation of tin, if present, contributes negligibly, so that the dependence of the deposition rate on the target current stays linear. At higher current densities (hence higher target temperatures), tin evaporation is no longer negligible, as suggested by the deposition rate data departing from the low-current linear trend. \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) is a first indicator of the long range crystalline order of a conventional superconductor such as \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\), with off-stoichiometry Nb-Sn composition being a major factor contributing to its degradation. The information, obtained from the deposition rate and supported by the data on the Sn average atomic content, that target surface current densities higher than 1.3 \(\hbox {mA cm}^{-2}\) may be causing tin partial evaporation from the target, combined with the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) reaching higher values for decreasing current density and higher argon pressure, supports the choice of \(2 \times 10^{-2}\) mbar and maximum 1.3 \(\hbox {mA cm}^{-2}\) as process gas pressure and applied target current, respectively.

Deposition temperature and annealing

At the beginning of the study, standard deposition runs included a 24 h annealing step, implemented at the end of each deposition with the aim to assist the formation of the A15 phase. However, it is also known that prolonged exposure to high temperatures can promote tin diffusion and tin evaporation, with the latter mostly affecting the samples on sapphire substrate, while diffusion likely being the dominant effect for the films on the other substrates. Therefore, keeping the deposition temperature as low as possible and shortening (if not removing) the annealing step, may be beneficial toward preserving the film stoichiometry for samples deposited on copper and NbBL. Hence, the effect of both the deposition temperature and the presence/duration of the annealing step on the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the films was also investigated.

In Fig. 2a, the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the samples deposited on sapphire is plotted as a function of the deposition temperature. Results for different annealing times are shown. In each case the annealing temperature equaled the deposition temperature. These samples, as discussed in the previous section, were deposited at a pressure of \(2 \times 10^{-2}\) mbar and at an applied target surface current density < 1 \(\hbox {mA cm}^{-2}\). The samples annealed for 24 h are shown by the full triangles, the samples which were not annealed by the empty triangles. Two individual data points are also shown, corresponding to samples for which an annealing step of intermediate duration (5 h and 2 h as indicated in the graph) was performed. With increasing deposition temperature, the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the samples increases toward a \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of 18.3 K for both sets of samples (24 h and no annealing) in a comparable fashion. However, the samples which were not annealed exhibit a higher \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) than the ones annealed for 24 h at lower deposition temperatures. The samples to which a short annealing was applied do not differ significantly from the non-annealed ones. This suggested that the annealing of the films post-deposition, if not detrimental for the achievement of the correct A15 phase, was neither necessary nor beneficial. The Sn average atomic content for the samples shown in Fig. 2a is provided as Supplementary Table S1 online. Based on these results, the annealing step was removed for the following deposition runs.

Substrate type

Once satisfying values for the target current and the argon pressure were found, and the annealing step removed, thanks to the results obtained with the samples deposited on sapphire, the focus of the study moved to the effect of the NbBL thickness on film properties. At first, in addition to sapphire, the film samples were deposited also on copper and NbBL-1 substrates. 1 \(\upmu\)m was the chosen starting thickness for the buffer layer, based on previous DCMS studies which implemented a 1 \(\upmu\)m-thick layer of tantalum as buffer layer17. The \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of these samples, deposited under the same conditions as the samples on sapphire shown in Fig. 1a, was also measured as a function of the target surface current density (not shown here). The results showed a \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) which remained constant between 12 K and 14 K up to a threshold surface current density of about 3 \(\hbox {mA cm}^{-2}\), beyond which superconductivity was not observed, regardless of argon pressure, for the samples deposited on both copper and NbBL-1. However, films on NbBL-1 consistently exhibited higher \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) (by 500 mK) than those on copper, suggesting that the NbBL partially mitigates tin diffusion into copper and helps preserve stoichiometry. Following this result, the thickness of the NbBL was gradually increased, and the results discussed in the following.

In Fig. 2b, the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of films deposited on copper and NbBL of thickness ranging from 1 μm to 40 \(\upmu\)m are shown as a function of the deposition temperature (following the development of the deposition recipe, these films were not annealed, and were deposited under the same conditions as the samples in Fig. 2a). It can be seen that the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the sample deposited on NbBL-1 has slightly increased with respect to the samples on copper, likely due to the presence of the NbBL, as just discussed. Increasing the deposition temperature does not seem to have an effect on the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\), a further suggestion that 1 \(\upmu\)m thickness of the buffer layer is not enough to totally prevent Sn migration. On the contrary, for the samples on NbBL-10, NbBL-30, and NbBL-40 \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) increases with both increasing NbBL thickness and increasing deposition temperature. The samples deposited on NbBL-30 and NbBL-40 reach \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) \(\gtrapprox\) 17 K at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) and maintain \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) > 17 K at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\), suggesting that a NbBL thickness of 30 \(\upmu\)m is sufficient to achieve optimal superconducting properties. Furthermore, copper surface inclusions were observed on the samples deposited on NbBL-1 at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) and \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\). Supplementary Fig. S2 online provides a SEM micrograph of the surface of a \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film deposited on a 1 \(\upmu\)m thick NbBL at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\). The EDS map analysis of these features confirmed their copper composition, suggesting diffusion through the NbBL and \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film. However, copper inclusions were never observed on samples deposited on thicker NbBLs. The Sn average atomic content for the samples shown in Fig. 2b is provided as Supplementary Table S3 online.

Structural and morphological properties of the Nb\(_{3}\)Sn films

Film morphology via SEM and chemical composition via EDS

The surface morphology of the NbBL and bulk Nb substrates, and of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films, was examined by SEM, as shown in Fig. 3 (“SEM micrographs”, top section). The first row displays, left to right, NbBLs of various thickness (NbBL-1, NbBL-10, NbBL-30) and the bulk Nb substrate. The second and third rows display \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited on these substrates at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) and \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) respectively.

The NbBL and bulk Nb substrates exhibit a homogeneous, crack-free surface. NbBL-1 presents a fine grain structure, while the surface of the NbBL-10+ and bulk substrates show well formed, larger grains, so that increasing the thickness of the buffer layer correlates with Nb grain growth. The surface of the bulk Nb substrate exhibits larger grains. The \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films show a distinct surface morphology depending on the NbBL thickness and deposition temperature. At \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\), the film on NbBL-1 exhibits a regular, homogeneous grain pattern. On the films deposited on NbBL-10+ and bulk Nb, isolated structures of marked geometrical shape, addressed in this context as islands, are observed. At \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\), the films deposited on all NbBLs show a regular, homogeneous grain structure, with larger grains compared to those deposited at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\). The grain size and appearance evolve with the thickness of the NbBL. The amount of Sn-rich islands increases with increasing buffer layer thickness (highest for Nb bulk, absent in Cu) and decreases with increasing substrate temperature (at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\), the presence of islands on NbBL-30 is almost suppressed, and significantly reduced on Nb bulk).

The lowermost row in Fig. 3 displays into more detail some morphological film features. An SEM micrograph of the ion-milled cross section of a \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) sample, deposited at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) on NbBL-30, is shown in Fig. 3a. The grain structure appears dense, void-free and homogeneous. A magnification of the islands of a film deposited on bulk Nb at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) is given in Fig. 3b, where the structure difference between the islands and the base film is visible. Finally, Fig. 3c shows the in-depth wedge-like structure of the islands. It can be observed that islands start nucleating at around 500 nm thickness, then rise parallel to the columnar growth of the film and protrude at the surface. For this image, a film on sapphire (also presenting island structures) was chosen as this substrate can be cracked, allowing to break the film in a way that the three-dimensional features of the islands can be visually enhanced. It is appropriate to specify that, although not shown here, all \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) samples deposited on sapphire exhibit the largest number of islands compared to the several substrates tested in this study.

Further insight is given by the Nb and Sn atomic content percentage measured via EDS at several point locations on the films deposited at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) on NbBL-10+ and bulk substrates is shown in Fig. 4a for the film base surface and in Fig. 4b for the islands. The SEM measurement settings are given in Methods - Characterization Tools. The average composition of the base film, on one hand, stays constant, with small variations, for all the considered substrates, with a ratio Nb/Sn close to 3, expected for the correct A15 stoichiometry. On the other hand, the composition of the islands reveals a significant deviation from this ratio, showing a systematic excess of tin, with corresponding Nb depletion, with respect to the underlying film. Despite the larger fluctuations of the composition measurements on the islands with respect to the ones on the base film, on average the island composition stays also constant for all the substrates.

DCMS from single stoichiometric target has the intrinsic advantage of not producing sub-stoichiometric phases. However, the nucleation of Sn-rich islands observed here appears similar to that already reported in literature for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) via VTD18 and in other works on \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) grown via PVD19. The data from this study allow for a qualitative interpretation of the effect of the substrate on the different number density of islands observed in Fig. 3. The incoming Sn adatoms follow two competitive paths: surface diffusion with nucleation in islands or diffusion into the substrate, with grain boundaries representing preferential paths. The second mechanism is favored in substrates with small grains (e.g. thin Nb buffer layers), where, for a given buffer layer substrate volume, the relative presence of grain boundaries is higher with respect to substrate with larger grains. In bulk Nb, sapphire, and thick Nb buffer layers, the diffusion of Sn through the substrate is therefore less favorable, resulting in the nucleation of a larger number of islands.

Structural properties via XRD

The crystallographic properties of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited on different substrates were investigated via XRD spectroscopy. Selected diffractograms for samples deposited on bulk Nb, NbBL-30, and NbBL-1 at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) are shown in Fig. 5a. The measured data is presented over the \(2\theta\) range covering the three most intense peaks of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) pattern, corresponding to the (002), (012) and (112) crystallographic planes, as indicated by the gray labels in bold placed next to the respective peak. The peak positions for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\)20, Nb21 and Cu22 sourced from the XRD reference data, are indicated by the vertical lines. The XRD data extracted for the samples shown in Fig. 5a and for samples deposited on more substrates are provided in Table 1. The patterns in Fig. 5a confirm the presence of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) phase across all samples, with slight variations in peak intensity and width depending on the substrate. All three \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) peaks are shifted to lower angles relative to the reference positions for samples deposited on NbBL-1 and NbBL-30, though the effect is less pronounced for NbBL-30. In contrast, for samples deposited on bulk Nb, the (002) peak is shifted to lower angles, while the (012) and (112) peaks shift to higher angles. The peak shifts observed for the sample on bulk Nb are the smallest among the three. Shifts of this kind, according to a preliminary analysis, are an indication of a strain condition of the film. The shift toward lower \(2\theta\) values in the samples on NbBL-1 and NbBL-30 indicates macrostrain, likely due to growth conditions and thermal expansion mismatch with the substrate. The latter is mitigated by the increased thickness of the NbBL, and the corresponding shift is consequently smaller. However, the shifts observed for the sample on bulk Nb, with its first main peak shifted to lower angles, while the other two shifted to higher angles, suggest a more complex, anisotropic stress state with an overall lower strain with respect to the other two samples.

A broadening of the most intense peak for the samples deposited on NbBL and copper with respect to the one deposited on sapphire is also observed, with the sample on sapphire exhibiting the narrowest peak and the one on copper the broadest peak, as confirmed by the FWHM data in Table 1. Peak broadening can suggest the presence of local variations in lattice spacing, due to defects such as dislocations, grain boundaries, vacancies, etc. A smaller broadening may be associated to a lower defect density and improved microstructural quality, as in the case of the NbBL-40 sample listed in Table 1. Peak broadening requires a dedicated analysis to separate the crystallite size effects, and no clear interpretation can be given to this data at this stage of the analysis. However, thicker NbBLs appear to mitigate macroscopic film stress and may be having a positive effect on reducing the defect density, potentially influencing reaction process of Sn with Nb to form the A15 phase and, therefore, the final film composition.

The (011) peak of niobium is visible in samples deposited on NbBL, appearing as a distinct peak for NbBL-30 but not fully resolved from the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) (012) peak in the NbBL-1 sample. Given the X-ray beam penetration depth of about 750 nm at \(3^\circ\) incidence angle, and the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film thickness of 1 \(\upmu\)m, these likely originated from the underlying NbBL substrate. This Nb peak was also present for the film deposited on bulk Nb, but it is not as evident in the pattern shown in Fig. 5 as the main orientation of the bulk substrate (hence, the most intense Nb peak) corresponded to the (022) plane, placed at a \(2\theta\) value out of the range displayed in the given graph. The (111) peak of copper is also observed in the NbBL-1 sample, likely coming from the substrate or from the washer print present on the sample, as visible in Fig. 10 in Methods - Sample Production.

Effect of the NbBL thickness on the SC transition temperature, composition and lattice parameter of the Nb\( _{3}\)Sn films

The evolution of the lattice parameters of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) (\(a_{\textrm{Nb}_{3}\textrm{Sn}}\)) and NbBL (\(a_{\textrm{NbBL}}\)), along with the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) as a function of NbBL thickness, is shown in Fig. 5b. The lattice parameter for the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films was calculated as the average of the lattice parameter values extracted from the respective three most intense XRD peaks, as the one shown in Fig. 5a (namely the ones corresponding to the (002), (012), and (112) planes). The same method has been used to calculated the lattice parameters for the NbBLs, whose XRD patterns were acquired separately and before the deposition of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film. It can be seen that, as the thickness of the NbBL increases, \(a_{\textrm{NbBL}}\) approaches the reference bulk value of 3.300 Å21,24, likely due to reduced residual stress. A similar trend is observed for \(a_{\textrm{Nb}_{3}\textrm{Sn}}\), which tends to the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) A15 phase value of reference 5.29 Å20,23 as the thickness of NbBL increases. In particular, for a NbBL thickness \(\ge\) 30 \(\upmu\)m, the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) lattice parameter stabilizes around 5.29 Å, indicating a well-formed A15 crystalline structure. For thinner NbBLs the lattice parameter deviates significantly, a possible indication of lattice distortions, in agreement with what discussed in the previous Sections.

The corresponding \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) values of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) samples, provided as labels next to the data points in Fig. 5b, are found to increase with NbBL thickness. The same trends were observed for samples deposited at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\), though they are not shown in this report. The EDS measurements indicate that the composition of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films at different probe points over the sample area is stable, with a Nb/Sn ratio close to the stoichiometric value of 3:1, independently of the thickness of the NbBL, as discussed in the previous Section (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the composition of the islands also appears to be independent of the thickness of NbBL (Fig. 4b). Therefore, the relation between the NbBL thickness and the increase in \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) may be mainly due to the relaxation of the crystal lattice, which for NbB-30+ grows with a lattice parameter which saturates at values close to those of the ideal A15 structure. The NbBL thickness also appears to suppress the thermal stress caused by the different thermal expansion of the two materials, which has been indicated by a recent study as the possible cause for the low \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited directly on copper via High Power Impulse Magnetron Sputtering (HiPIMS)25.

These trends are compared with data from literature13 in Fig. 6. This data (star markers) was obtained from bulk samples produced via levitation melting with controlled stoichiometry variation23, with Sn content varying from 18 At% to 25 At%. Therefore, while a direct quantitative comparison with the samples produced via DCMS in this study is not possible, a qualitative comparison of material properties can be made. The resulting dependence of the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) and lattice parameter of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) data from literature is an increase of both these quantities with increasing Sn content. For the samples in this study, on the other hand, what was varied in a controlled way is the thickness of the NbBL. The Sn content was measured by EDS in an area of size \(400\times {270}~{\upmu }\textrm{m}^2\). Hence, the obtained value takes into account the contribution of grains, islands, and grain boundaries, which were not considered in the analysis shown in Fig. 4, as those values were extracted by probing the surface over point-sized areas (\(<~0.2~{\upmu }\textrm{m}^2\)). For these films, the average Sn content measured via EDS ranges from 22% for the sample on NbBL-1 to 25% for the sample on bulk Nb, which is within the uncertainty bars given in Fig. 4a. Unlike in the bulk case, the films exhibit increasing \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) with decreasing lattice parameter. As a result, the two data sets show a converging trend in \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) toward the literature A15 phase values, corresponding to opposite variation in the lattice parameter.

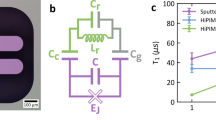

RF properties of the Nb\( _{3}\)Sn film with the quadrupole resonator (QPR)

The ultimate test to assess the suitability of the produced \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films for SRF applications is a cryogenic performance measurement under realistic field and RF conditions. The RF properties of the optimized coating procedure, especially its surface resistance \(R_\text {S}\), were studied using the QPR at Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB). The experimental setup is described in detail later in Methods - Characterization Tools.

To estimate the contribution to the residual resistance of the sample’s sensitivity to cooldown conditions, following the initial cooldown, thermal cycles at different cooldown rates were performed, with each of the presented data sets corresponding to a different thermal cycle. By design, QPR cooldown dynamics are different from the ones of standard vertical cavity tests, due to the limited conduction cooling of the RF-exposed sample top surface. In fact, conduction occurs via the sample sidewall, with the sample base being the only thermal contact with the cooled cavity, as shown in Fig. 11 (right). This way, the SC transition phase front moves radially from the outside to the center of the flat sample top. As explained in further detail in Methods - Characterization Tools, under these conditions, a slow cooldown (or low cooldown rate) corresponds to a larger spatial temperature gradient and, vice-versa, a fast cooldown (or high cooldown rate) corresponds to a smaller spatial temperature gradient. This is not to be compared to the case of vertical cavity tests for which, due to the different system configuration and cooldown dynamics, larger gradients correspond to fast cooldown and smaller gradients correspond to slow cooldown. However, for both the QPR and vertical cavity tests, the effect of temperature gradients is to induce thermoelectric currents and, therefore, trapped magnetic flux, which results in an increased \(R_{\textrm{res}}\). In Figs. 7a and b, the measured \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) is plotted against the RF peak field at the sample surface (at 4 K and 417 MHz) and against the sample temperature (at 30 mT and 417 MHz), respectively. Depending on the cooldown dynamics, different values are obtained. The obtained \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) showed the known behavior of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) being sensitive to trapped magnetic flux, especially driven by thermoelectric currents during the superconducting transition. This is visible as a constant offset in \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) between different cooldowns, hence only affecting the residual resistance \(R_{\textrm{res}}\). As generally expected for cavity measurements, in the QPR case a cooldown with minimum temperature gradient also leads to the lowest \(R_{\textrm{res}}\). In this case, this was achieved by performing a full thermal cycle of the QPR cavity inside its cryostat and yielded an \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) of about 25 n\(\Omega\) at \(B_{\textrm{RF}}\) = 20mT, as can be seen from Fig. 7a. The data in Fig. 7b shows that the initial cooldown yields a minimum \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) of 51 n\(\Omega\) at 30 mT. A slow cooldown (-0.1 \(\hbox {K min}^{-1}\)), with active heating of the sample, leads to an increased \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) of \(\sim\) 60 n\(\Omega\) at 2.5 K. A fast cooldown (-18.5 \(\hbox {K min}^{-1}\)) yields a reduced \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) of \(\sim\) 35 n\(\Omega\), also at 2.5 K. A full thermal cycle of the entire resonator, which resulted in a uniform cooldown at a rate of -6 \(\hbox {K min}^{-1}\), led to lowest \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) values of \(\sim\) 25 n\(\Omega\). Notably, a repeated fast cycle increased this value back to \(\sim\) 35 n\(\Omega\). The exact experimental procedure to perform each type of cooldown is also reported in Methods - Characterization Tools. The fact that \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) data for both fast cooldowns agree perfectly, and remain unaffected by the previous cooldowns, underscores that this is due to trapped magnetic flux generated by induced thermoelectric currents, and not to trapped environmental magnetic flux as, in the latter case, the total flux amount (or at least the geometrical distribution) would have changed during the full thermal cycle of the resonator.

For comparison, QPR data for a sample prepared by vapor tin diffusion (’VTD sample’) on a bulk niobium substrate, and at temperatures up to \({1100}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\)26,27, is added to Figs. 7a and b. The original data can be found in Ref. 26. However, due to instrumentational issues at the time of the measurement, only data for the initial cooldown are reported. Before plotting, the data measured on the sample produced by VTD was reduced by 12 n\(\Omega\) to compensate for parasitic losses from the normal conducting adapter flange which was used at that time28. This correction leads to similar values as the ones obtained in this study at low RF field. However, the observed increase of \(R_\text {S}\) with increasing RF field was stronger in the present case.

The RF penetration depth (\(\lambda _{\textrm{RF}}\)) of the sample was also extracted from the measured frequency shift as a function of sample temperature, shown in Fig. 8a. A non-linear fitting of the data yields \(T_\textrm{c} = {17.60}(3)~\textrm{K}\) and \(\lambda _0 = {315(24)}~\textrm{nm}\). The result for \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) is in good agreement with the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) data presented in this work. Also, the result obtained for \(\lambda _0\) is in good agreement with the London penetration depth \(\lambda _{\textrm{L}}\) measured, in a separated study, via the microwave characterization of coplanar-waveguide-resonators (CPWRs) patterned on \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) thin films produced according to the optimized deposition recipe presented in this work, which lead to a value of 310 nm11.

Figure 8b shows the RF quench field of the sample measured at the first two quadrupole modes, 417 MHz and 851 MHz. The plot only includes data points with \(B_\text {RF}<{50}~\textrm{mT}\) (\(T>{10}~\textrm{K}\)), conditions for which RF heating is negligible. A quadratic fit of the RF quench field data was performed, according to \(B_{\textrm{q}}(T) = B_0(1-(T/T_{\textrm{c}})^2)\), where “q” stands for “quench”. This leads to \(T_\textrm{c} = {17.65}(7)~\textrm{K}\), which is again in good agreement with the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) data presented here, and a low-temperature extrapolated quench limit of \(B_0 = {77.5}(5)~\textrm{mT}\). Again, QPR data for a sample prepared by VTD is added to Fig. 8b for comparison. The original data can be found in Refs. 26 and 27. The RF quench field is independent of frequency which excludes significant RF heating as systematic error source. The extrapolated quench limit for \(B_0\) indicates non-ideal performance, lower than that reported for single-cell cavities produced via VTD18. Also, it can be seen that the VTD sample showed higher values for \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) and RF quench field, indicating room for RF performance improvement for the DCMS coating procedure. Nevertheless, the quench field value obtained for the DCMS sample corresponds to a maximum accelerating gradient of \(E_\text {acc}={18.2}~\textrm{MV/m}\) in a TESLA-shaped cavity29, which is overall a satisfying result.

With the QPR, quench field and frequency shift measurements allow independent access to \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) that can lead to different results. This is due to the fact that, for quench field data, the possible effects due to the presence of point-like defects may be dominant, while frequency shift data always depicts a volumetric average over the RF-illuminated area and the penetration depth. For the sample presented here, both values showed good agreement, indicating a quench behavior that was magnetically dominated by regions of average \(T_{\textrm{c}}\), compatible with a rather homogeneous \(T_{\textrm{c}}\)-distribution and, therefore, a homogeneous \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) coating.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the successful development of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films on copper via single-target DCMS, thanks to an optimized set of deposition parameters resulting in high \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) (17 K) and good film morphology. The presence of a Nb buffer layer (NbBL) of thickness \(\ge\) 30 \(\upmu\)m is crucial to stabilize film stoichiometry via residual stress reduction and enhanced crystallinity. To this point, the optimal base recipe in terms of \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the films can be summarized as the following:

-

1 \(\hbox {mA cm}^{-2}\) maximum target surface current density;

-

\(2 \times 10^{-2}\) mbar argon pressure;

-

\(\le\) \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) maximum substrate temperature;

-

no annealing;

-

\(\ge\) 30 \(\upmu\)m minimum NbBL thickness.

Unlike VTD, which is prone to the formation of sub-stoichiometric phases, DCMS proves to be a promising technique to avoid the latter, as demonstrated by the absence of spurious peaks in the XRD diffractograms. The SEM analysis highlights the role of the NbBL in mitigating Sn-rich island formation, while XRD also confirms improved structural properties with increased NbBL thickness. RF measurements using the QPR indicate promising \(R_\text {S}\) values (23 n\(\Omega\) at 4.5 K, 20 mT and 400 MHz), with quench fields (77 mT). At low RF fields up to 20 mT, the \(R_\text {S}\) values are comparable or better than those of the QPR sample VTD, while the quench value is lower, although still sufficient for many applications. The quench field, as well as the sharp decrease in Q, can be attributed to specific stoichiometric imbalances introduced by the Sn-rich islands, which this study has shown to be particularly favored in PVD films grown on bulk Nb substrates, while NbBL on Cu has the ability to mitigate them. The limitation on the deposition temperature, imposed by the use of a copper substrate, currently prevents DCMS coatings from reaching \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of 18.3 K, expected for stoichiometric \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\). Nevertheless, RF testing via QPR shows that \(R_\text {S}\) values comparable to the state of the art can be achieved already at \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) \(\sim\) 17 K, provided that the coating exhibits good compositional uniformity and relaxation of lattice stress. Overall, these findings provide a first, promising step towards the scalability of the DCMS recipe for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films to high-performance \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\)/Cu SRF cavities, supporting the development of future particle accelerators like the FCC-ee.

Methods

Experimental setup

The \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films which are object of this study were produced via the PVD technique DCMS, using a 4” (10.16 cm) diameter commercial \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) stoichiometric planar target (75% Nb, 25% Sn, 99.99% purity) as source material. The experimental setup is schematically represented in Fig. 9. The top frame shows a technical drawing of the stainless steel (SS) ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber inside which the deposition processes were carried out. The sample holder consists of a 10 cm diameter SS plate onto which the substrates to be coated were mounted, as shown by inset on the top-left of Fig. 9. The magnetron with the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) target, and the sample holder plate are mounted at two opposite sides of the chamber, in front of each other, coaxially, and separated by a 90 mm distance. The magnetron field is provided by two current-supplied electromagnets. The gas employed for the sputtering process was 6N purity (99.9999%) argon. The substrate temperature was regulated via a set of three infrared (IR) lamps (500 W) placed behind the sample holder. The power provided to the IR lamps was regulated via a PID feedback loop which takes as input the temperature measured by a thermocouple fixed onto the sample plate itself, next to the substrates. The base pressure achievable in the UHV chamber is about \(5 \times 10^{-10}\) mbar. The complete piping and instrumentation diagram of the sputtering system is given in the bottom frame of the figure.

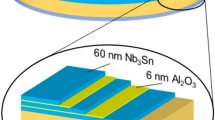

Sample production

The production of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film samples was carried out according to a standard procedure. Each deposition process was performed on four different substrates: sapphire (Al\({}_{2}\)O\({}_{3}\)), oxygen-free high thermal conductivity (OFHC) copper, OFHC copper pre-coated with a NbBL and bulk Nb (\(\textrm{RRR} = 300\)). As sapphire is known not to affect the film properties, the deposition of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films on sapphire substrate was chosen, especially in the initial phase of the study, to serve as a reference standard for comparison with what obtained on copper substrate. A schematic drawing of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited on different substrates is given in Fig. 10. Starting from the left, the image depicts the film on sapphire, copper, NbBL-1, NbBL-10+, and bulk Nb. Sapphire, copper and niobium substrates have a standard size of \(10\times 10\times {1}~\textrm{mm}^{3}\), \(10\times 25\times {0.5}~\textrm{mm}^{3}\) and \(10\times 25\times {2.8}~\textrm{mm}^3\) respectively (the relative thickness for the different layers of each sample drawing is not to scale).

Before deposition, sapphire substrates were cleaned with ethanol in an ultrasound bath, while copper substrates were cleaned in a detergent solution (GP 17.40 SUP NGL) in an ultrasound bath, then treated with SUBU30 solution for 2 – 3 minutes. Bulk Nb substrates were treated with a Buffer Chemical Polishing (BCP) solution, consisting of a mixture of three acids: \(\mathrm {H_3PO_4}\) (85%), \(\mathrm {HNO_3}\) (65%), and \(\textrm{HF}\) (40%) in a volume ratio of 2:1:1, at room temperature31.

NbBLs were deposited via DCMS on the prepared copper substrate. The final NbBL thickness ranged from a minimum of 1 \(\upmu\)m to a maximum of 50 \(\upmu\)m. The deposition was performed according to a sequential technique that allows for the production of thick films while minimizing residual stress32. The NbBLs were stored in rough vacuum until the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) coating process took place, to minimize chances of contamination. In preparation to the coating, the substrates were fixed on the sample holder plate, which was then mounted inside the UHV chamber. The experimental setup and the coating system are described in more detail in Methods - Experimental Setup.

The process started by baking the system for 24 – 48 h. The baking temperature was always set approximately \({\sim 50}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) higher than the deposition temperature. After the baking, the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) coating took place in an argon atmosphere. The process parameters such as gas pressure, current applied to the sputtering target, and substrate temperature were custom set for each coating run and are object of this study. Generally, the sputtering phase duration ranged between 6 h and 10 h for films 1 \(\upmu\)m thick, depending on the deposition rate, which, in turn, depends on the applied current and on the target consumption. When the deposition was over, the samples were annealed by keeping them at the same temperature at which the coating was performed, for a duration of 24 h, though shorter annealing times have also been investigated. As a result, the annealing step was considered obsolete and removed, as previously discussed in Results and Discussion.

Once the deposition process was over, the samples underwent the following characterization procedures:

-

Measurement of the critical temperature;

-

Check of the surface morphology;

-

Measurement of the Nb-Sn composition;

-

Assessment of the crystalline structure.

For a sub-selection of samples, a deeper analysis was made, including the imaging of the film cross-section exposed by ion milling, and a punctual EDS analysis of the composition of specific sample areas which exhibited peculiar morphological features. For the RF validation of the deposition recipe, a QPR bulk Nb sample was also prepared and measured at different RF frequencies, temperatures, and thermal cycle conditions. Prior to film deposition, this bulk Nb sample was also pre-treated via BCP as described earlier. The instrumentation employed for each characterization procedure is described in the next Section.

Characterization tools

Induction coil

The SC transition of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film samples was measured inductively using a custom-made, contactless induction coil system at INFN-LNL. The working principle is well described in Ref. 33. The critical temperature \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) was extracted from the SC transition curve via the 90% - 10% method, which provides more conservative values compared to the commonly adopted onset value in magnetometry measurements. This method also allows for an estimate of the transition curve spread, which serves as an indicator of the quality of the superconducting phase of the material. The spread of the SC curve is used as a conservative uncertainty on the extracted \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) value. Each sample was cooled in zero field, and the measurement was performed by warming the sample from 7 K to 20 K with a temperature ramp of approximately 100 \(\hbox {mK min}^{-1}\). The \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) value and transition curve width were then extracted using a custom analysis software based on MATLAB.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)/energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)

The sample surface micrographs and composition analyses used in this study were acquired using two different SEM devices: a CX-200 plus by COXEM, equipped with a modular QUANTAX Compact EDS system by Bruker (based at INFN-LNL), and a Zeiss Ultra 55 equipped with a Thermo Scientific EDS detector (based at the University of Siegen). For the analysis performed with the CX-200, a standard procedure was followed in which images were acquired at 500x and 5000x magnification from five different sample areas. A working distance of \(\sim 14\) mm was set to achieve an optimal EDS angle for elemental analysis (for each area, the EDS spectrum is acquired at 20 kV). Additionally, an EDS analysis of an extra sample area was performed at voltages ranging from 10 kV to 25 kV , in 5 kV steps, to obtain a semi-quantitative in-depth composition profile. From these analysis areas, of size \(400\times 270\) \(\upmu \hbox {m}^2\), were extracted the surface-averaged values of Sn At% indicated in Figs. 1b and 6. The standard deviations calculated for the averaged values were below 0.1 At%. For the analysis performed with the Ultra 55, the micrographs were collected with the In-Lens detector at a magnification of 15kx and a voltage of 10 kV, with a working distance of 3 mm to 4 mm. The Nb At% and Sn At% measurements presented in Fig. 4 were performed with this instrument under the point-like analysis setting, with each probe point covering an area of size < 0.2 \(\upmu \hbox {m}^2\).

X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRD)

The crystallographic analysis of the films was performed at INFN-LNL using an X’Pert\({}^{3}\) MRD X-ray diffractometer by Philips/Panalytical, equipped with a horizontal goniometer with a 320 mm radius. Sample analysis was done on a flat stage in grazing incidence angle geometry (\(2\theta\) scan axis). The incident beam was set at \(3^\circ\), and the measurement spanned a 30\(^\circ\) to 90\(^\circ\) range in continuous mode, with step size of 0.025\(^\circ\) and step time 2s. Data such as peak position, peak shift and FWHM were extracted from the diffractogram using the HighScorePlus software. The analysis involved background removal followed by peak fitting using a default pseudo-Voigt function.

Quadrupole resonator (QPR)

SRF characterization of films was performed using a QPR15,28 at Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB). The QPR is a dedicated sample test cavity designed primarily to measure the RF surface resistance \(R_\text {S}\). A cross section of the device is shown in Fig. 11. The resonator consists of a cylindrical cavity made from high-RRR niobium (depicted in green), with two pole-shoe-shaped niobium pipes (shown in orange) attached such that their flattened and bent center sections are positioned less than 1 mm from the surface of an interchangeable sample (shown in red). This consisted of a dedicated cylindrical substrate of 75 mm diameter and 99 mm height, prepared from RRR = 300 niobium for the specific case presented in this work. The face and lateral surface of the substrate were coated via DCMS at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) according to the coating routine implemented in this study. The entire cavity is immersed in superfluid liquid helium, which also cools the pole shoes from the inside. RF power is coupled into the resonator via an inductive coupler (not shown), while the resonant field is measured using a second, weakly coupled antenna. The resonator can excite quadrupole-like modes at 417 MHz, 850 MHz, and 1300 MHz, which are concentrated in the gap between the pole shoes and the sample surface. These modes induce RF currents in the sample. For the present study, the \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) data were collected only at the 417 MHz mode, while the quench field data were collected at 417 MHz and 850 MHz modes. Most of the \(R_{\textrm{S}}\) data was collected in continuous wave (CW) mode, with some data collected in pulsed mode at duty factors of 30% and 40%, to overcome sample heating and extend the measurement range. All quench field data was collected in pulsed mode. The sample is thermally decoupled from the resonator via a coaxial line, allowing direct measurements of RF dissipation (and hence \(R_\text {S}\)) using a calorimetric RF-DC compensation technique with a heater and a temperature sensor positioned at the bottom of the sample. Surface resistance measurements can be conducted at high RF fields up to 120 mT and arbitrary sample temperatures above the minimum liquid helium bath temperature of 1.5 K. Additionally, the QPR enables measurements of other relevant parameters, including the superconducting transition temperature, the RF quench field and the London penetration depth. For a detailed description of the measurement techniques the reader is referred to15.

Thermal cycling of the sample was conducted using the sample heater, which was also employed for the calorimetric measurements, to briefly heat the sample into the normal conducting state and back. This also allowed a certain control of the transition into the superconducting state during cooldown. For the “slow” cooldown the heater was active and its power was PID-controlled, allowing for a minimum possible cooldown speed of -0.1 \(\hbox {K min}^{-1}\). For a fast cooldown, the heater was switched off after heating the sample to 20 K. The following natural cooling yielded the maximum dT/dt of -18.5 \(\hbox {K min}^{-1}\). Besides operating the sample heater, the sample can be cycled by evaporating the surrounding helium bath. During these so-called “full cycles” the entire resonator, including the pole shoes, was brought to the normal conducting state. During helium refill, the sample heater remained off, resulting in a cooldown rate of -6 \(\hbox {K min}^{-1}\). By design, the QPR sample is conduction cooled via its cylindrical sidewall. On the sample surface this leads to the situation in which the superconducting phase front always moves radially from the outside to the center of the sample. By powering the sample heater, the cooldown rate can be reduced but at the cost of an increased radial temperature gradient. However, temperature gradients during the superconducting transition are the driving force for thermoelectric currents that, in turn, generate trapped magnetic flux leading to increased residual resistance. Opposed to other vertical cavity tests, a homogeneous cooldown of the sample cannot be achieved by a slow cooldown with active heating. The full cycle of the QPR during helium refill depicts an optimum case where the cooling power is sufficiently low, yielding a cooldown that is simultaneously moderate in temperature rate and good in homogeneity.

(a) Critical temperature \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films as a function of the target surface current density, for samples deposited on sapphire at \({630}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) temperature, and \(2 \times 10^{-2}\) mbar and \(3 \times 10^{-3}\) mbar argon pressure. Error bars on the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) values correspond to the width of the superconducting transition curve extracted via the 10% - 90% method. (b) Deposition rate as a function of the surface current density applied to the sputtering target, for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) samples deposited on sapphire at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) to \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) deposition temperature, and \(2 \times 10^{-2}\) mbar and \(3 \times 10^{-3}\) mbar argon pressure. The linear fit is only applied to the low-current-density data range. The values indicated above the data points indicate the Sn content expressed in At%.

(a) Dependence of \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) on the deposition temperature for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) samples deposited on sapphire. The full markers represent the data taken for samples annealed at the same temperature at which they were deposited and for different time lengths (24 h, 5 h, 2 h). The empty markers represent data taken for samples which were not annealed. (b) Dependence of \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) on the deposition temperature for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) samples deposited on copper and NbBL substrates, with the thickness of the NbBL ranging from 1 \(\upmu\)m to 40 \(\upmu\)m. Connecting lines have been added to guide the reader’s eye. These samples did not undergo the annealing step. Note the difference in temperature range for the abscissas in the two plots. For both figures, the error bars on the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) values correspond to the width of the superconducting transition curve extracted via the 10% - 90% method (for the error bars \(< \pm\)0.5 K) and to the spread of the \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) values when more than one sample was included for the data point (for the error bars > ±0.5 K).

SEM micrographs of the NbBL and the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) samples. Upper table: the first row shows the surface morphology of NbBLs of varying thickness (left to right: 1 \(\upmu\)m, 10 \(\upmu\)m, 30 \(\upmu\)m) and of a bulk Nb substrate; the middle row shows the surface morphology of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film samples deposited on the respective substrate indicated by the corresponding column, at \({600}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) deposition temperature; the samples shown in the third row are deposited at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\). The green and blue dots on the SEM micrograph of the film on bulk Nb substrate in this last row represent, respectively, examples of the “\(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film base surface” and the “island formations” EDS analysis points mentioned in Fig. 4. Lower table: (a) ion-milled cross section of a \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film sample deposited on a NbBL-30; (b) ion-milled cross section of a sample deposited on bulk Nb, whit the inset at the top-left showing a close-up on the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film surface exhibiting island formations; (c) cross section obtained by cracking a sample deposited on sapphire, highlighting (dotted yellow line) the in-depth structure of the island formations. The inset at the top-right shows a close-up of the sample surface. All samples shown in the lower table are deposited at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\).

Niobium and tin atomic content percentage estimated via EDS for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film samples deposited on NbBLs of different thickness (9 \(\upmu\)m, 30 \(\upmu\)m, 40 \(\upmu\)m) and bulk Nb. (a) Punctual measurements on the surface of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) base film. The mean value horizontal lines correspond to 75.9 At% for Nb and 24.1 At% for Sn. (b) Punctual measurements on the island formations. The mean value horizontal lines correspond to 60.6 At% for Nb and 39.4 At% for Sn. The error bars indicate the instrumental uncertainty on the elemental quantification.

(a) XRD spectra of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films deposited on (top to bottom) bulk Nb, NbBL-30 and NbBL-1 at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) deposition temperature. The three characteristic peaks are shown. The nominal lines for \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\), Nb and Cu in the given \(2\theta\) range are also indicated. (b) Average lattice parameter of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films (empty triangles) and of the corresponding NbBL onto which they were deposited (full triangles) as a function of the NbBL thickness. The \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) measured for the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films is indicated by the label at each data point. The samples are deposited at \({650}~^{\circ }\textrm{C}\) deposition temperature.

Comparison of the experimental data collected within this study with what found in literature13. The dependence of \(T_{\textrm{c}}\) from the average lattice parameter of \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) is shown. The Sn composition is indicated in At% under the NbBL labels. The two data sets converge at about 25 At% content of tin.

QPR surface resistance measurement data at 417 MHz for different cooling conditions during the superconducting transition. (a) \(R_\text {S}\) vs. RF field at constant sample temperature of 4 K. (b) \(R_\text {S}\) vs. T for an RF magnetic field of 30 mT. For both plots, ’VTD sample’ denotes the QPR measurement data for a sample prepared by vapor tin diffusion26, corrected by 12 n\(\Omega\) according to28.

(a) Frequency shift measurement. The material’s penetration depth and transition temperature are extracted by non-linear fitting. (b) RF quench field vs. sample temperature measured at two quadrupole modes. The quadratic fits yield again \(T_\text {c}\) and the extrapolated quench limit at 0 K. ’VTD sample’ denotes the QPR measurement data for a sample prepared by vapor tin diffusion26,27.

Top: technical drawing of the stainless steel UHV deposition chamber. The 4” magnetron with the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) sputtering target and the sample plate are mounted coaxially in front of each other at a 90 mm distance. The IR lamps employed to control the substrate temperature are visible below the the sample plate. The top left inlet shows a rotated perspective on the substrates mounted on the sample plate. Bottom: piping and instrumentation diagram of the DCMS system, showing the pumping stages, valves, pressure and temperature sensors, and the process (argon) and venting (nitrogen) gas supplies.

Schematic representation of the different substrate types employed for the deposition of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) films. The size of the substrates is also given. The thicknesses are not to scale. The bright gray layer on top represents the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film. A real-life picture of the \(\textrm{Nb}{}_{3}\textrm{Sn}\) film side of each substrate after the deposition process is shown in the line below, with the NbBL-10+ being in this case a 30 \(\upmu\)m thick NbBL.

Cutaway view of the HZB Quadrupole Resonator (QPR), with real bulk Nb sample shown on the left. The interchangeable sample (shown in red) is inserted into the cavity (depicted in green) from below and positioned less than 1 mm from the pole shoes (shown in orange) which focus the RF magnetic field onto that region. The surface resistance of the sample is measured calorimetrically by employing a heater and temperature sensors attached beneath the sample. The entire cavity is immersed in superfluid liquid helium.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hutton, A. Energy-recovery linacs for energy-efficient particle acceleration. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 708–716. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-023-00644-6 (2023).

Posen, S. & Hall, D. L. Nb3Sn superconducting radiofrequency cavities: Fabrication, results, properties, and prospects. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 30, 033004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/30/3/033004 (2017).

Posen, S. et al. Advances in Nb3Sn superconducting radiofrequency cavities towards first practical accelerator applications. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 34, 025007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/abc7f7 (2021).

Boussard, D. Performance of the LEP2 SRF system. In Proc. of the 17th Particle Accelerator Conference, 2879–83 (1998).

Boussard, D. & Linnecar, T. P. R. The LHC superconducting RF system. In Proc. of the Joint Criogenic Engineering Conference and International Cryogenic Materials Conference (1999).

Hao, X., Zerkle, B., Cosco, J. & Dausman, R. Development of a 5 W/4.2 K two-stage pulse tube cryocooler. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1301, 012140. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1301/1/012140 (2024).

Mitchell, S. SHI Cryogenics Group Releases World’s Highest-Capacity 4K Cryocooler. https://shicryogenics.com/shi-cryogenics-group-releases-worlds-highest-capacity-4k-cryocooler/.

Sikivie, P. Detection rates for “invisible’’-axion searches. Phys. Rev. D 32, 2988–2991. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.32.2988 (1985).

Sikivie, P. Experimental tests of the “Invisible’’ Axion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 51, 1415–1417. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.51.1415 (1983).

Marconato, G. et al. NbTi Thin Film SRF Cavities for Dark Matter Search. In 21th International Conference on RF Superconductivity (SRF’23), Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 25-30 June 2023, 96–99, https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-SRF2023-MOPMB014 (JACOW Publishing, 2023).

Ghigo, G. et al. Heavy ion irradiation effects on the high-frequency properties of YBCO and Nb3Sn thin films. Superconductivity 13, 100149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supcon.2024.100149 (2025).

Vidal Garcia, P. Microwave Vortex-dynamics Characterization in Nb3Sn under High Magnetic Fields. In 11th International Workshop on Thin Films and New Ideas for Pushing the Limits of RF Superconductivity - TFSRF2024, https://indico.cern.ch/event/1376902/contributions/6111702/ (2024).

Godeke, A. A review of the properties of Nb3Sn and their variation with A15 composition, morphology and strain state. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 19, R68–R80. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/19/8/R02 (2006).

Pira, C. Nb thick films in 6 GHz superconducting resonant cavities. Ph.D. thesis, Università degli studi di Padova (2018).

Keckert, S., Kleindienst, R., Kugeler, O., Tikhonov, D. & Knobloch, J. Characterizing materials for superconducting radiofrequency applications-A comprehensive overview of the quadrupole resonator design and measurement capabilities. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 92, 064710. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0046971 (2021).

Ohring, M. Materials Science of Thin Films (Elsevier, 2002).

Ilyina, E. A. et al. Development of sputtered Nb3Sn films on copper substrates for superconducting radiofrequency applications. Supercond. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/aaf61f (2019).

Willson, S. A. et al. Impact of submicron Nb3Sn stoichiometric surface defects on high-field superconducting radiofrequency cavity performance. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 043133. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.6.043133 (2024).

Sayeed, M. N., Reece, C. E., Eremeev, G. V., Pudasaini, U. & Elsayed-Ali, H. E. Properties of Nb3Sn films fabricated by magnetron sputtering from a single target. Appl. Surf. Sci. 541, 148528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.148528 (2021).

Geller, S., Matthias, B. T. & Goldstein, R. Some new intermetallic compounds with the “\(\beta\)-Wolfram’’ structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 77, 1502–1504. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01611a029 (1955).

Dryś, M., Sosnowski, J. & Folcik, L. Phase equilibria in the niobium-gallium-iron system at 1000 \(^\circ\)C. J. Less Common Metals 68, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(79)90054-7 (1979).

Suh, I.-K., Ohta, H. & Waseda, Y. High-temperature thermal expansion of six metallic elements measured by dilatation method and X-ray diffraction. J. Mater. Sci. 23, 757–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01174717 (1988).

Devantay, H., Jorda, J. L., Decroux, M., Muller, J. & Flükiger, R. The physical and structural properties of superconducting A15-type Nb-Sn alloys. J. Mater. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00542375 (1981).

Straumanis, M. E. & Zyszczynski, S. Lattice parameters, thermal expansion coefficients and densities of Nb, and of solid solutions Nb-O and Nb-N-O and their defect structure. J. Appl. Crystallogr. https://doi.org/10.1107/S002188987000554X (1970).

Rosaz, G. Nb3Sn coatings for RF cavities. In FCC Week 2025, https://indico.cern.ch/event/1408515/contributions/6514112/ (2025).

Keckert, S., Hall, D., Knobloch, J., Kugeler, O. & Liepe, M. Surface resistance characterization of Nb3Sn using the HZB quadrupole resonator. In Proc. of the 18th International Conference on RF Superconductivity, vol. SRF2017, 863–866, https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-SRF2017-THPB053 (JACOW, 2018).

Keckert, S. et al. Critical fields of Nb3Sn prepared for superconducting cavities. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 32, 075004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ab119e (2019).

Keckert, S. et al. Mitigation of parasitic losses in the quadrupole resonator enabling direct measurements of low residual resistances of SRF samples. AIP Adv. 11, 125326. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0076715 (2021).

Aune, B. et al. Superconducting TESLA cavities. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Accel Beams 3, 092001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.3.092001 (2000).

Pira, C. et al. Evaluation of cleaning process. ARIES Deliverable Report D15.1, INFN (2018).

Palmieri, V., Stivanello, F., Stark, S. Y., Roncolato, C. & Valentino, M. Besides the Standard Niobium Bath Chemical Polishing. In Proc. of the 10th Workshop on RF Superconductivity (2001).

Garcia Diaz, V. et al. Thick film morphology and SC characterizations of 6 GHz Nb/Cu cavities. In Proc. of the 20th International Conference on RF Superconductivity, vol. SRF2021, 18–22, https://doi.org/10.18429/JACOW-SRF2021-SUPCAV007 (JACoW Publishing, 2022).

Fonnesu, D. Thin films on copper for superconducting RF cavities within the future circular collider study. Doctoral Thesis, University of Siegen (2023). https://doi.org/10.25819/ubsi/10600.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to their collaborators within the I.FAST programme, C. Antoine, O. Malyshev, A. Medvids, T. Proslier, S. Prucnal, G. Rosaz, E. Seiler, A. M. Valente-Feliciano, R. Valizadeh, W. Venturini-Delsolaro, M. Wenskat for the fruitful scientific exchange. They acknowledge the work and technical support by the INFN-LNL mechanical workshop, in particular by A. Battistello, T. Bortolami, A. Minarello, and F. Pasquato. The authors also wish to thank O. Azzolini, R. Caforio, A. Fetaj, G. Keppel, G. Mastrotto, F. Stivanello from the Superconductivity and Surface Technology Service at INFN-LNL for the advice, support, supply of equipment and facilities and for providing chemical surface treatments. Finally, the authors warmly thank A. Bianchi and R. Vaglio for the scientific insight, and TESCAN (via Assing SpA) for kindly providing the SEM micrographs in Figs. 3a and b.

Funding

This research was partly supported in by the European Union’s Horizon-INFRA-2023-TECH-01 under GA No 101131435 - iSAS, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under GA No 101004730 – I.FAST, the PNRR MUR project number PE0000023-NQSTI, the INFN CSN5 experiment SuperMAD and INFN ESPP project SRF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Fonnesu (corresponding author): design of work, thin-film sample production, Tc, SEM, EDS, XRD data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, all figures elaboration, manuscript writing. D.Ford: design of work, thin-film sample production, Tc, SEM, EDS, XRD data acquisition, technical support, figure 4-9-10 elaboration. E.Chyhyrynets: substrate chemical preparation, technical support. S.Keckert: QPR data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, figure 7-8-11 elaboration. J.Knobloch: scientific advice. O.Kugeler: QPR data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. M.Lazzari: Tc, SEM, EDS, XRD data acquisition. G.Marconato: thin-film sample production, Tc, SEM, EDS, XRD data acquisition. A.Salmaso: thin-film sample production, Tc, SEM, EDS, XRD data acquisition. A.Zubtsovskii: SEM, EDS data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, figure 3-4 elaboration. C.Pira: design of work, Tc, SEM, EDS, XRD data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fonnesu, D., Ford, D., Chyhyrynets, E. et al. Recipe optimization and SRF test of Cu-compatible Nb\({}_{3}\)Sn films by DC magnetron sputtering from a stoichiometric target. Sci Rep 16, 3539 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33547-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33547-w