Abstract

Piercing metal tubes is essential for creating openings in multi-port industrial fittings. Conventional piercing techniques often struggle to provide satisfactory edge quality, leading to challenges such as needing pre-drilling, limitations to circular shapes, and edge bulging. While fluid-assisted piercing has been explored, it introduces complexities such as sealing difficulties and expensive tooling. This study examines elastomeric-assisted piercing of aluminum tubes using experimental and numerical methods to address these limitations. Using Abaqus, the process was modeled with the Mooney-Rivlin framework to capture the elastomeric tool’s incompressible behavior, while the Gurson-Tvergaard-Needleman (GTN) model predicted ductile failure. Experiments involved piercing 12 mm diameter holes in seamless 6061 aluminum alloy tubes (thicknesses: 1 mm, 1.4 mm, and 1.8 mm) with polyurethane tools of 50 and 85 Shore A hardness, covering 8 distinct test conditions (with and without a counter punch). Final piercing forces were observed to range between 28.78 kN and 61.93 kN. The Finite Element model, utilizing the GTN damage criterion, predicted these forces with an average error of less than 5.5%. The investigation focused on how tube thickness, tool hardness, and maximum process force influence outcomes. Findings demonstrate that with appropriate selection of process parameters—such as material type, geometry, tube thickness, and tool hardness—elastomeric piercing is feasible and yields high-quality cut surfaces. This approach demonstrates that elastomeric piercing, when tailored to material and geometric parameters, offers a practical solution for achieving high-quality cuts, circumventing the drawbacks of conventional and fluid-based techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, industries such as aerospace and automotive have increasingly prioritized innovative techniques for forming and cutting metal components, seeking to enhance workpiece integrity while optimizing production efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Among these techniques, using elastomeric pads in forming and cutting processes has emerged as a standout method, undergoing substantial refinement due to its unique capabilities. This approach offers exceptional adaptability, high-quality surface finishes, and economical die construction and upkeep, primarily owing to its reliance on a single rigid tool half. Key benefits include the reduced tooling expenses, improved surface quality, suppression of wrinkling, accelerated tool development timelines, and streamlined setup without the need for precise tolerance tuning. Nevertheless, the technique is tempered by challenges such as elevated energy demands, low production speeds, limited suitability for oversized or thick-walled components, finite durability of the elastomeric medium, restrictions on applicable pressure, and incompatibility with elevated temperatures1.

The use of elastomeric tools has gained traction in recent research, broadening their application beyond traditional forming to enhance various metalworking processes2,3,4,5. Early work by Al-Qureshi on tube expansion with elastomeric tools explored how factors like material composition, tube dimensions, and tool configuration influence strain distribution in the finished product6. This foundational study spurred further investigations into elastomeric-assisted tube expansion7,8,9. In the field of sheet piercing, Hertz and Garber pioneered the use of elastomeric pads, revealing that the failure load in such operations hinges on the rubber’s properties, while the failure threshold of the material remains consistent regardless of rubber type or die shape10. Al-Qureshi et al. later performed an experimental elastomeric piercing, identifying ram movement as a function of variables like sheet thickness, rubber stiffness, ram velocity, material hardening traits, and tool design11. A theoretical model by Al-Qureshi to evaluate ram stroke effects in piercing showed strong alignment with experimental data, though it was confined to annealed copper12. Watari et al. advanced this field by empirically testing rubber-assisted sheet piercing, focusing on hardness, thickness, and contact dynamics between metal sheets and polyurethane layers. Their work clarified the piercing mechanism using polyurethane as a punch, establishing the optimal parameters for clean hole formation—specifically, polyurethane with ideal hardness ranging from 80 to 90 Shore A and a thickness of 3 to 5 mm13. Nasajiyan Moghadam et al. assessed rubber hardness (65, 70, and 85 Shore A) and die corner radius in sheet piercing. They found minimal cutting force with 65 Shore A rubber and a 0.05 mm die corner radius, and radius effects diminishing at higher hardness14. Recently, the application of elastomeric punches has been successfully extended to complex processes such as hole-flanging, where using polyurethane with a hemispherical end significantly improved the formability and thickness distribution control of aluminum sheets15. Furthermore, comparative studies on hyperelastic constitutive models in elastomeric-assisted tube bending have confirmed the superior accuracy of the Mooney–Rivlin model in predicting springback behavior compared to other models like Neo-Hookean16.

While fluid-based methods dominate existing studies on tube piercing, using elastomeric tools for this purpose remains uncharted. This research introduces a novel application of polyurethane elastomeric tools to pierce metal tubes, employing Abaqus simulations with the Mooney-Rivlin framework to capture the elastomeric tool’s incompressible behavior, while the Gurson-Tvergaard-Needleman (GTN) model predicted ductile failure. The GTN model is widely regarded as a robust framework for simulating ductile failure, having been successfully applied to analyze damage control parameters in functionally graded materials (FGMs) used in notched plates17. Its reliability has been further demonstrated in studies that determined the elastoplastic and damage parameters for heat-resistant alloys via inverse finite element analysis of small punch tests18. Moreover, the GTN model is a valuable tool for crack resistance curve analysis, aiding in the assessment of operational safety for structures like oil and gas storage units19, and has been effectively used in the numerical simulation of void elimination during industrial processes such as hot shape rolling20. This research, for the first time, investigates the feasibility of the elastomeric-assisted tube piercing method. Aiming at process optimization, we conducted a parametric analysis regarding the influence of tool properties (hardness) and part geometry (tube thickness) on the maximum process force and final cut quality. Our results demonstrate that, with the appropriate selection of parameters, this method is not only feasible but also produces high-quality cut surfaces. Furthermore, the correlation between experimental results and numerical predictions validates the proposed finite element model’s ability to describe the complex behavior of this process. This exploration into elastomeric-assisted tube piercing represents a significant step forward in expanding the scope of flexible tooling applications.

Materials and methods

Experimental procedure

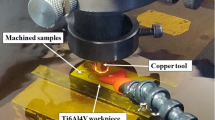

In this study, seamless 6061 aluminum alloy tubes with an outer diameter of 35 mm and an initial wall thickness of 2 mm were selected as the base material. Test specimens with thicknesses of 1 mm, 1.4 mm, and 1.8 mm were prepared to investigate the effect of tube wall thickness on the elastomeric-assisted piercing process. These samples were obtained by machining the inner surface of the tubes using a lathe. The elastomeric tools, made of polyurethane, were fabricated in cylindrical shapes with hardness levels of 50 and 85 Shore A and diameters of 33 mm, 32.2 mm, and 31.4 mm. To characterize the mechanical properties of the aluminum tubes, three identical specimens were prepared according to the ASTM A370 standard, and tensile tests were conducted (see Fig. 1). These tensile tests were performed using an Instron 8802 machine at a strain rate of \(\:\dot{\epsilon\:}=0.0005\:{s}^{-1}\). The resulting stress-strain curve derived from these tests is presented in Fig. 1. For the polyurethane elastomeric tool, the Mooney-Rivlin constitutive model was employed to define its mechanical behavior. The model coefficients were determined through uniaxial compression tests conducted according to the ASTM D575-91 standard (refer to Table 1). The compression tests on the elastomeric tool were carried out at a constant strain rate of \(\:\dot{\epsilon\:}=0.0005\:{s}^{-1}\) using the Instron 8802 machine.

(a) Prepared tubes after internal machining, (b) Dimensions of the tensile test specimen based on ASTM A370 standard (dimensions in mm), along with the sampling position relative to the tube cross-section and the tensile test specimen, (c) True stress-strain curve of 6061 aluminum alloy tube, accompanied by its mechanical properties.

A dedicated die was engineered using SolidWorks software to accommodate the polyurethane tool’s functionality and perform the experimental piercing tests. The die components were crafted from VCN150 steel through CNC milling, followed by a hardening treatment to bolster their strength. Precision grinding was applied to key surfaces to maintain flatness and alignment. To ensure accurate assembly, the design incorporates two alignment pins to facilitate the seamless joining of the die halves. The fixed mandrel, located at one end of the die, is sized to correspond with the inner diameter of the tube, thereby ensuring stable support throughout the process. The movable mandrel features a stepped end to engage the polyurethane tool effectively, with its geometry meticulously adjusted to prevent contact with the tube walls during peak compression. The piercing operation initiates with the placement of the polyurethane tool inside the tube, followed by the positioning of the tube within the die cavity. The alignment of the die halves is accomplished through the use of pins and six bolts that are firmly secured via a reinforced backing plate. This backing plate is specifically designed to evenly distribute loads across the die during operational activities. The movable mandrel is subsequently positioned atop the polyurethane tool, with the entire assembly placed on the press table. As the press ram applies force, the mandrel compresses the elastomeric tool, thereby generating the radial pressure necessary to pierce the tube at the specified die cavity, in which resistance is intentionally minimized. A significant aspect of this die design is the precision-engineered sharpness of the cutting edges encircling the piercing zone, which is essential for achieving a clean cut. The cutting edge of the die was precision-ground to maintain a highly sharp radius of \(\:r\le\:0.05\) mm to maximize shear quality. Figure 2a and b provide an illustration of the conceptual layout and the constructed components of the piercing die employed in this study, respectively.

In the experimental tests conducted, polyurethane tools with hardness levels of 50 and 85 Shore A were used for samples with a thickness of 1 mm, while only the polyurethane tool with a hardness of 85 Shore A was employed for samples with thicknesses of 1.4 mm and 1.8 mm. The conditions of the experimental tests performed in this study are detailed in Table 2.

Numerical modeling

To explore the behavior of the piercing process, numerical simulations were conducted using Abaqus software, chosen for its advanced capabilities in handling complex material failure analyses and its robust solver for dynamic problems. This study leverages the Gurson-Tvergaard-Needleman (GTN) failure criterion, a micromechanical model embedded within Abaqus, to predict ductile fracture in the aluminum tube. This work emphasizes a streamlined simulation setup tailored to elastomeric-assisted tube piercing, solved via an explicit dynamic method over a single step with a duration of one second.

The GTN model relies on nine critical parameters— \(\:{q}_{1}\), \(\:{q}_{2}\), \(\:{q}_{3}\), \(\:{f}_{0}\), \(\:{f}_{c}\), \(\:{f}_{F}\), \(\:{f}_{N}\), \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{N}\), and \(\:{S}_{N}\)—which must be carefully established to ensure accurate predictions. Drawing from Tvergaard and Needleman’s recommendations21 and other researchers, the yield surface modification parameters were assigned as \(\:{q}_{1}=1.5\), \(\:{q}_{2}=1\), and \(\:{q}_{3}=2.25\) (where \(\:{q}_{3}\) is the square of \(\:{q}_{1}\)). Consistent with literature insights22,23,24,25, the standard deviation of the nucleation strain (\(\:{S}_{N}\)) was set to 0.1, and the mean nucleation strain (\(\:{\epsilon\:}_{N}\)) was fixed at 0.3, applicable across material types. The initial void volume fraction (\(\:{f}_{0}\)) was established at 0.000125 based on established references26. Determining these values is often complex due to the lack of a universal methodology, necessitating tailored approaches. The remaining parameters—critical void volume fraction (\(\:{f}_{c}\)), failure void volume fraction (\(\:{f}_{F}\)), and nucleated void volume fraction (\(\:{f}_{N}\))—were derived through an inverse calibration technique. This involved simulating a standard tensile test repeatedly, adjusting these three parameters until the simulated force-displacement curve aligned closely with experimental data. Multiple simulation iterations were performed, comparing the resulting force-displacement profiles to refine the GTN parameters for 6061 aluminum. The final calibrated values, which yielded the closest match to the experimental tensile behavior, are summarized in Table 3.

In the 3D simulation of the piercing operation, the die, fixed mandrel, and movable mandrel were represented as rigid discrete shells, whereas the tube and polyurethane tool were modeled as deformable entities. In select simulations, a counter punch—also configured as a rigid discrete shell—was introduced within the die to manage the flow of both the material and the polyurethane tool at the point of shearing. Each rigid component was assigned a reference point to define its boundary and loading conditions. The aluminum tube was specified with an outer diameter of 35 mm, a length of 60 mm, and wall thicknesses of 1 mm, 1.4 mm, and 1.8 mm. Due to symmetry, only one-quarter of the model was simulated. The tube was treated as an elastic-plastic material, with its mechanical properties outlined in Fig. 1. The polyurethane tool’s nearly incompressible behavior was captured using a first-order Mooney-Rivlin hyperelastic model, with coefficients determined from compression tests and listed in Table 1.

Considering the substantial deformation of the tube during piercing and the complex contact interactions, an explicit dynamic solver was utilized, with a simulation step time set to one second. Surface interactions were modeled using a general contact framework, with mechanical contact conditions incorporating tangential behavior via a penalty friction model. The friction coefficient was set to 0.1 for interactions with rigid components and 0.2 between the tube and the elastomeric tool27,28,29. Boundary conditions were grouped into three types: symmetry constraints applied in the X and Z directions to the polyurethane tool and in the Z direction to the tube; fixed constraints assigned to the reference nodes of the die, fixed mandrel, and counter punch to prevent movement; and a displacement condition imposed on the movable mandrel’s reference node to generate the piercing force. These conditions are depicted in Fig. 3-b. Meshing of the die, fixed mandrel, movable mandrel, and counter punch utilized R3D4 elements—four-node, 3D rigid elements—while the tube and polyurethane tool were discretized with C3D8R elements—eight-node, 3D continuum elements with reduced integration. We used a fine mesh in the critical shear zone around the rigid die edge, which is the region of highest strain gradient and fracture initiation. The local element size was set to 0.1 mm in the shear zone, 0.2 mm in the die hole region, and 0.5 mm in the rest of the tube. The optimal number of elements along the tube thickness was found to be 5 elements. The most sensitive part of our model is the prediction of fracture initiation and evolution, which is controlled by the parameters of the GTN damage model. These parameters are inherently mesh size dependent and require accurate calibration. We performed a specialized mesh convergence study on the tensile test simulation, which was used to calibrate the GTN parameters. The mesh convergence curve for the GTN calibration phase is shown in Fig. 3-a and supports the reliability of the element size. Figure 3-c provides a 3D visualization of the meshed die components alongside the tube mesh for the elastomeric-assisted piercing process.

The simulation of eight experimental piercing tests using the polyurethane tool was conducted in Abaqus, aligning with the experimental conditions of the process (variations in tube thickness, the effect of elastomeric tool hardness, and the presence or absence of a counter punch), as outlined in Table 4.

Results and discussion

In cutting and piercing processes, one of the critical parameters is the piercing force and press capacity. Therefore, this section evaluates the influence of elastomeric tool hardness, tube wall thickness, and the presence of a counter punch on the force-displacement curves, assessed through both experimental and numerical analyses. The results are subsequently compared and validated. For each parameter’s evaluation, only the parameter under investigation is varied, while the others remain constant across the tests.

Effect of elastomeric tool hardness

To investigate the effect of polyurethane tool hardness, experimental tests T01 and T03 were selected and compared. These tests involved piercing a 1 mm thick tube using polyurethane tools with hardness levels of 85 Shore A and 50 Shore A, respectively, both conducted without a counter punch. The influence of tool hardness on the experimental force-displacement curve in the absence of a counter punch is depicted in Fig. 4-a. Analysis of these curves reveals that in tests T01 and T03, employing a polyurethane tool with lower hardness (50 Shore A) results in a reduced final failure force. The force-displacement curves exhibit two distinct drops: the first corresponds to the onset of shear failure, followed by tensile deformation in the burr region until the second drop, which marks the completion of the cut. To assess the effect of tool hardness with a counter punch, experimental tests T02 and T04 were compared. Figure 4-b illustrates the impact of polyurethane tool hardness on the force-displacement curves in this configuration. Comparison of these curves indicates that a lower-hardness tool (50 Shore A) again yields a lower failure force. It can be concluded that using a polyurethane tool with low hardness consistently decreases the failure force, irrespective of the counter punch’s presence.

This phenomenon is mechanically attributed to the difference in the hyperelastic properties of the two polyurethanes. Due to the significantly lower Mooney–Rivlin coefficients (C10 and C01) of the 50 Shore A tool (Table 1), it exhibits lower stiffness and stores less elastic strain energy for a given axial displacement. Crucially, this results in less radial pressure being generated on the tube wall. Since the required critical radial pressure dictates the piercing force, the softer tool requires a lower maximum axial force to reach the necessary critical shear stress and complete the fracture. This observation is also supported by our experimental data (Table 5), which confirms that the lower maximum force is achieved at less displacement compared to the 85 Shore A tests. This effect highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate tool hardness.

In addition to the mechanical interpretation, fracture surface analysis provides further insight into the influence of tool hardness. SEM micrographs of samples T04 and T02, pierced using polyurethane tools with hardness levels of 50 Shore A and 85 Shore A respectively, reveal distinct differences in fracture morphology. Sample T04 (Fig. 5-a) exhibits a smoother and more uniform fracture surface, with a clearly visible rounded radius at the upper cutting edge, highlighted by a red circle. This curvature indicates localized plastic deformation and early material flow into the die orifice, promoting shear-dominated fracture at lower force levels. In contrast, sample T02 (Fig. 5-b) shows a rougher, more fibrous fracture surface with less curvature, suggesting a more abrupt failure mechanism. Additional SEM images (Figs. 5-c and 5-d) further support these observations. Sample T04 displays a compact and cohesive fracture texture, while sample T02 reveals layered and porous features indicative of ductile tearing. These results confirm that lower rubber hardness not only reduces the required piercing force but also improves surface quality and burr control.

The numerical analysis of the effect of polyurethane tool hardness on the force-displacement curve was examined using corresponding simulation tests: S01 and S03 (without a counter punch) and S02 and S04 (with a counter punch). Figure 4-c presents the curves for the simulated tests S01 and S03. Examination of these curves shows that the displacement at the start and end of failure is nearly identical in both simulations; however, the use of a 50 Shore A polyurethane tool results in a lower final failure force. Similarly, Fig. 4-d displays the curves for simulated tests S02 and S04, indicating that a lower-hardness tool (50 Shore A) leads to a marginally reduced final failure force. In these simulations, for equivalent displacement at the start and end of failure, the 50 Shore A tool consistently produces a lower piercing force, aligning with the experimental findings.

Effect of tube wall thickness

In this study’s elastomeric-assisted tube piercing process, tubes with wall thicknesses of 1 mm, 1.4 mm, and 1.8 mm were utilized. To evaluate the effect of tube thickness, two primary conditions—without and with a counter punch—were considered, as outlined in Table 2. Tests T01, T05, and T07 were conducted without a counter punch, while tests T02, T06, and T08 included a counter punch. Figure 6-a illustrates the influence of tube thickness on the experimental force-displacement curve using a polyurethane tool with 85 Shore A hardness (without a counter punch). It can be inferred that increasing tube thickness elevates the piercing process force, attributable to the larger cross-sectional area of the fracture zone. However, in tests T05 and T07, despite thickness increases of 40% and 80%, respectively, the process force did not exhibit proportional increases of 40% and 80%. This discrepancy is likely influenced by factors such as clearance and friction between the polyurethane tool and the tube. Figure 6-b depicts the effect of tube thickness on the force-displacement curve under identical conditions but with a counter punch. Consistent with the previous case, comparing these curves reveals that thicker tubes require higher piercing forces, again due to the increased fracture cross-sectional area.

The effect of tube thickness on the force-displacement curves was also assessed through simulations corresponding to experimental tests T01, T05, and T07 (simulations S01, S05, and S07), as shown in Fig. 6-c. These curves indicate that increasing tube thickness results in higher piercing forces, corroborating the experimental outcomes. Similarly, simulations of tests T02, T06, and T08 (simulations S02, S06, and S08) were compared, with results presented in Fig. 6-d. These findings confirm that thicker tubes lead to increased piercing forces in this configuration as well, with the rise in force attributed to the greater cross-sectional area at the fracture site.

Effect of tube thickness on the force-displacement curve, (a) Comparison of experimental tests T01, T05, and T07 (without counter punch), (b) Comparison of experimental tests T02, T06, and T08 (with counter punch), (c) Comparison of simulation tests S01, S05, and S07 (without counter punch), (d) Comparison of simulation tests S02, S06, and S08 (with counter punch).

Effect of counter punch

Based on the conditions outlined in Table 2 (experimental test design), four scenarios arise for evaluating the effect of the counter punch on the force-displacement curve. A comparison of the curves for tests T01 and T02 (using a polyurethane tool with 85 Shore A hardness and a 1 mm thick tube), presented in Fig. 7-a, reveals that the presence of a counter punch initiates piercing with less displacement and completes it with reduced displacement as well. This can be attributed to the burr contacting the counter punch, flattening its surface, and shifting the burr’s deformation mechanism from tensile to shear. Additionally, when the counter punch is used, after the onset of cutting, the burr’s contact with the counter punch confines the polyurethane tool, increasing the forming chamber pressure as the movable mandrel displaces, thereby elevating the process force. Moreover, with the counter punch, the rates of void nucleation, growth, and coalescence accelerate following burr contact, enabling sample failure with less applied force. The counter punch facilitates uniform hydrostatic pressure distribution, enhancing void coalescence and crack propagation in the shear zone, ultimately leading to material fracture.

The influence of the counter punch on the force-displacement curve was also examined through simulations. The curves for simulation tests S01 and S02 are shown in Fig. 7-b. It is observed that, similar to the experimental results, the simulation with a counter punch requires a lower final failure force.

A comparison of the curves for tests T03 and T04 (using a polyurethane tool with 50 Shore A hardness and a 1 mm thick tube), presented in Fig. 8-a, yields a similar conclusion to the previous case: the presence of a counter punch reduces the failure force. Furthermore, these two tests, which utilized a 50 Shore A polyurethane tool, require less failure force compared to the scenario with an 85 Shore A tool (T01 and T02). The curves comparing simulation tests S03 and S04 are shown in Fig. 8-b. It is evident that in the simulation with a counter punch, a lower final failure force is needed.

Figure 9 presents the force-displacement curves for tests T05 and T06 (using a polyurethane tool with 85 Shore A hardness and a 1.4 mm thick tube). The curves in Fig. 9 indicate that the use of a counter punch in these tests reduces the failure force. A comparison of simulation tests S05 and S06 is shown in Fig. 9-b. It is observed that, in these simulations, the presence of a counter punch has minimal impact on the force-displacement curve.

By comparing the curves in Fig. 10 (tests T07 and T08—using an elastomeric tool with 85 Shore A hardness and a 1.8 mm thick tube), it can be observed that the use of a counter punch, similar to Fig. 9, reduces the force required for failure. In this case, the counter punch also decreases the displacement at the failure point. A comparison of simulation tests S07 and S08 is presented in Fig. 10-b. The curves from these tests confirm that, as in the previous case (Fig. 9-b), the presence of a counter punch has little effect on the force-displacement curve.

Validation of numerical results

A comparison between the results of experimental tests and simulations was conducted, with the force-displacement curves obtained from both experimental and simulated tests—considering the effects of various parameters—presented in Fig. 11. Additionally, Table 5 provides the conditions of the experimental and simulation tests along with the results extracted from the force-displacement curves at the point of final failure.

Force-displacement curves of simulation tests and their experimental counterparts (hollow circles represent tests without a counter punch, filled circles represent tests with a counter punch, and dashed lines represent simulations): (a) S01 and T01, (b) S02 and T02, (c) S03 and T03, (d) S04 and T04, (e) S05 and T05, (f) S06 and T06, (g) S07 and T07, (h) S08 and T08.

The error analysis presented in Table 5 highlights two primary conditions where the discrepancy is more pronounced. Firstly, the slightly larger error observed in the 1.0 mm tube pierced with the 50 Shore A tool is primarily attributed to the increased compliance and higher sensitivity of the softer polyurethane to the friction conditions and complex deformation experienced by the thin tube. Secondly, the most significant increase in error occurs in the thickest tube (1.8 mm), reaching 4.33% in the 85 Shore A case. As discussed in detail below, this increase is linked to the limitation of the GTN model in capturing the shear-dominated fracture mechanism induced by the change in thickness. The analysis of the curves in Fig. 10 reveals that at lower tube thicknesses, employing a polyurethane tool with reduced hardness decreases the process force. Additionally, using thinner tubes in the piercing operation, regardless of tool hardness, results in samples with superior fracture surface quality. This observation is clearly supported by the SEM micrographs presented in Fig. 11 (sample with thinner tube, Fig. 12-a, and sample with thicker tube, Fig. 12-b). Under identical processing conditions, the thinner tube exhibits a smoother and more uniform fracture surface, with reduced fibrous deformation and fewer irregular features. In contrast, the thicker tube shows a rougher and more uneven fracture morphology, characterized by elongated ridges and ductile tearing.

The results indicate that for higher tube thicknesses, the counter punch has negligible influence on the force-displacement curve. Utilizing a lower-hardness polyurethane tool is a suitable option when press capacity is limited or production volume is low. However, a drawback observed in experimental tests with lower-hardness tools was their limited usability, as they could only withstand a small number of cycles before experiencing rupture and degradation during testing.

A key finding from the curve analysis is that the initial failure of samples occurs shortly after the process begins, both temporally and spatially. This is due to the force applied through the movable mandrel to the polyurethane tool, which, given the material’s near-incompressibility, gradually increases pressure. At the outer tube wall, where the die hole is located, the tube’s resistance diminishes, initiating the cutting operation. As displacement increases, the process force rises, triggering void nucleation and growth, leading to the initial failure in the tube at the die hole region. With further force application, the rate of void nucleation, growth, and coalescence accelerates, resulting in a secondary failure that completes the cutting process. Closer inspection of these curves also suggests that when a counter punch is used, the final failure occurs more rapidly due to the increased rate of void nucleation, growth, and coalescence. These observations are validated by comparing the curves in Fig. 11 from both experimental and simulation tests.

Figures 13-a and 13-b present the average force curves from experimental tests and simulations for samples of varying thicknesses, with and without a counter punch (using a polyurethane tool with 85 Shore A hardness). These curves indicate that as sample thickness increases, the discrepancy between the average experimental and simulated forces grows in both scenarios—with and without a counter punch. However, this discrepancy is smaller when a counter punch is employed compared to when it is absent. Figs. 13-c and 13-d display the percentage error between experimental and simulated forces as a function of sample thickness. This increased error is primarily attributed to the inherent limitations of the standard GTN model when the tube thickness becomes substantial (1.8 mm). In thinner tubes, the fracture is dominated by void growth under moderate shear. However, with increasing thickness, the failure mechanism in the shear zone transitions to a more complex shear-dominated fracture mode. It is well-documented that the standard GTN model, which relies on void growth under hydrostatic tension, is less accurate in these shear-intensive scenarios. Specifically, the model is known to effectively exclude the possibility of shear fracture, as it predicts no damage change with strain under zero mean stress30. Consequently, the GTN simulation is unable to fully capture the material’s softening and failure under this shifting stress state, leading to a higher discrepancy between the numerical prediction and the experimental result at the maximum thickness.

Based on the curves in Fig. 13, it can be concluded that the optimal condition for elastomeric-assisted tube piercing is achieved when a counter punch is used in conjunction with a polyurethane tool of 85 Shore A hardness.

Process force curves as a function of sample thickness: (a) Without the use of a counter punch, and (b) With the use of a counter punch; Percentage error curves between average experimental and simulated forces as a function of sample thickness: (c) Without the use of a counter punch, and (d) With the use of a counter punch.

In Fig. 14, the geometry of the pierced components for two samples, T01 and T06—representing tests without and with a counter punch, respectively—is displayed alongside their corresponding simulations from experimental tests. A very close agreement between the experimental and simulated results is observed.

Conclusion

This research systematically proved the feasibility of the elastomeric-assisted tube piercing process for the first time and developed a numerical modeling framework for its analysis. The Finite Element model was validated using the Mooney-Rivlin model for the elastomer and the Gurson-Tvergaard-Needleman (GTN) model for predicting ductile failure in the aluminum tube. The key quantitative and qualitative findings of this study can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

The maximum piercing force was observed across 8 distinct test conditions and found to range between 28.78 kN and 61.93 kN. In this investigation, lower-hardness elastomeric tools (50 Shore A) consistently reduced the piercing force and improved the final cut quality compared to the 85 Shore A tool, establishing a clear path for process optimization.

-

2.

The developed Finite Element model demonstrated a strong quantitative correlation with the experimental results. The numerical predictions for the maximum piercing force showed high agreement with the measured data, with an overall average error of less than 5.5%. This validates the high predictive capability of our model.

-

3.

The maximum error observed in the numerical predictions was 4.33%, recorded for the thickest tube (1.8 mm). This increased error is specifically attributed to the limitations of the standard GTN model in capturing the fracture mechanism under high shear stress. As discussed in the Discussion section, the GTN model is known to effectively exclude the possibility of shear fracture, a mechanism that becomes more dominant with increasing tube thickness.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Benisa, M., Babic, B., Grbovic, A. & Stefanovic, Z. Computer-aided modeling of the rubber-pad forming process. Mater. Tehnol. 46, 503–510 (2012).

Ghafourian Nosrati, H. & Gerdooei, M. Fabricating by elastomeric tools: A review of development in Iran. J. Comput. Appl. Res. Mech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.22061/jcarme.2024.10785.2414 (2024).

Abbasi, I., Gerdooei, M. & Nosrati, H. G. Implementation of the extended maximum force criterion (EMFC) for evaluating the pressure-dependent forming limit diagrams (PD-FLD) in the tube bulging process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-024-14883-z (2024).

Najm, A. A., Namer, N. S. M. & Nama, S. A. Influence of rubber pad on springback of titanium sheets by wipe bending process. Int. Conf. Sustain. Eng. Tech. 020031. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0212275 (2024).

Hammod, F. H., Aljarjary, A. I. & Shukur, J. J. Experimental investigation of the rubber pad hardness and height influence on the drawing of low carbon steel cup. in 060017 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0209012

Al-Qureshi, H. A. Factors affecting the strain distributions of thin-walled tubes using polyurethane rod. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 13, 403–413 (1971).

Ghaforian Nosrati, H. & Gerdooei, M. Experimental and numerical study of friction in free bulging 304 stainless steel seamed tube using elastic pad. Modares Mech. Eng. 15, 30–40 (2015).

Ghaforian Nosrati, H., Seyedkashi, S. M. H. & Gerdooei, M. Investigation of effective parameters in free bulging of stainless steel 304 tube using elastomer tool. Modares Mech. Eng. 16, 191–198 (2016).

Ghaforian Nosrati, H., Gerdooei, M. & Falahati Naghibi, M. Experimental and numerical study on formability in tube bulging: A comparison between hydroforming and rubber pad forming. Mater. Manuf. Process. 32, 1353–1359 (2017).

Garber, S. & Hertz, P. B. The punching of sheet metal with rubber. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 63-WA-310, 17–22 (1963).

Al-Qureshi, H. A., Garber, S. & Mellor, P. B. Piercing of metal sheet with rubber pads. Int. J. Prod. Res. 6, 207–225 (1967).

Al-Qureshi, H. A. Analytical investigation of Ram movement in piercing operation with rubber pads. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Des. Res. 12, 229–248 (1972).

Watari, H., Ona, H. & Yoshida, Y. Flexible punching method using an elastic tool instead of a metal punch. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 137, 151–155 (2003).

Nasajiyan Moghadam, A. H., Gerdooei, M. & Mamashli, H. Investigation of the rubber hardness and die corner radius on the sheet metal piercing process with rubber tools. In 25th Annu. Conf. Mech. Eng. (2017).

Belhassen, L., Koubaa, S., Wali, M. & Dammak, F. in 262–268 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86446-0_34

Sayar, M. A., Gerdooei, M., Nosrati, H. G. & Eipakchi, H. Comparative study of hyperelastic material constitutive models on tube bending springback: experimental and numerical insights. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40032-025-01295-5 (2025).

Slamene, A. et al. Assessing gradient parameters for damage control in Notched plates: finite element analysis of locally functionally graded materials using the Gurson-Tvergaard-needleman (GTN) model. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 53, 1392–1428 (2025).

Li, Q., Zhao, L., Wang, X., Xu, L. & Han, Y. Determination of the Gurson-Tvergaard-Needleman damage model parameters for simulating small punch tests of heat-resistant alloys. Int. J. Press. Vessel Pip. 212, 105348 (2024).

Gajdoš, Ľ., Šperl, M., Korouš, J. & Kuželka, J. Evaluating the suitability of the Gurson—Tvergaard—Needleman plasticity model for crack resistance curve analysis. Appl. Sci. 14, 5882 (2024).

Zhu, S., Fu, Y., Wu, S. & Guo, S. Numerical simulation of void elimination in the billet during hot shape rolling processes based on the Gurson–Tvergaard–Needleman model. AIP Adv 14, 025029 (2024).

Needleman, A. & Tvergaard, V. An analysis of ductile rupture in Notched bars. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 32, 461–490 (1984).

Springmann, M. & Kuna, M. Identification of material parameters of the Gurson–Tvergaard–Needleman model by combined experimental and numerical techniques. Comput. Mater. Sci. 32, 544–552 (2005).

Oh, C. K., Kim, Y. J., Baek, J. H., Kim, Y. P. & Kim, W. A phenomenological model of ductile fracture for API X65 steel. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 49, 1399–1412 (2007).

Yang, S., Zhou, J., Ling, X. & Yang, Z. Effect of geometric factors and processing parameters on plastic damage of SUS304 stainless steel by small punch test. Mater. Des. 41, 447–452 (2012).

Scheider, I., Nonn, A., Völling, A., Mondry, A. & Kalwa, C. A damage mechanics based evaluation of dynamic fracture resistance in gas pipelines. Procedia Mater. Sci. 3, 1956–1964 (2014).

Yu, H. et al. Tensile fracture of ultrafine grained aluminum 6061 sheets by asymmetric Cryorolling for microforming. Int. J. Damage Mech. 23, 1077–1095 (2014).

Akbarian Kouhkheyli, M. & Gerdooei, M. Optimization of Process Variables in Forming of Tube Fittings by Using Elastomer Tool. (2016).

Dirikolu, M. H. & Akdemir, E. Computer aided modelling of flexible forming process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 148, 376–381 (2004).

Wang, L. L., Li, D. S., Li, X. Q., Wang, L. & Yang, W. J. Coefficient of friction for aluminum alloy sheet in contact with polyurethane rubber. Appl. Mech. Mater. 26–28, 320–325 (2010).

Nahshon, K. & Hutchinson, J. W. Modification of the Gurson model for shear failure. Eur. J. Mech. - A/Solids. 27, 1–17 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hamzeh Mamashli: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation. Mahdi Gerdooei: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Hasan Ghafourian Nosrati: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mamashli, H., Gerdooei, M. & Ghafourian Nosrati, H. Parametric study of piercing force and surface quality in elastomer-assisted tube piercing. Sci Rep 16, 3612 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33673-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33673-5