Abstract

For many individuals, communication through sign language (SL) is the primary means of interacting with the world, and the potential applications of effective SL Recognition (SLR) systems are vast and far-reaching. SLR is a research area dedicated to the automatic analysis of hand gestures and other visual signs used in communication among individuals with speech or hearing impairments. Despite significant advancements, the automated detection and interpretation of human signs remain a complex and multidisciplinary challenge that is yet to be fully addressed. Recently, various approaches have been explored, including the application of machine learning (ML) models in SLR. With advancements in deep learning (DL), sign recognition systems have become more accurate and adaptable, helping to bridge the communication gap for individuals with hearing impairments. Building upon these developments, the present study introduces a novel approach by integrating an advanced optimization strategy with a representation learning model, aiming to improve the robustness, accuracy, and real-world effectiveness of SLR systems. This paper proposes a Pathfinder Algorithm-based Sign Language Recognition System for Assisting Deaf and Dumb People Using a Feature Extraction Model (PASLR-DDFEM) approach. The aim is to enhance SLR techniques to help individuals with hearing challenges communicate effectively with others. Initially, the image pre-processing phase is performed by using the Gaussian filtering (GF) model to improve image quality by removing the noise. Furthermore, the PASLR-DDPFEM approach utilizes the SE-DenseNet model for feature extraction. Moreover, the Elman neural network (ENN) model is implemented for the SLR classification process. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed by using the Pathfinder Algorithm (PFA) model to enhance the classification performance of the ENN classifier. An extensive set of simulations of the PASLR-DDPFEM method is accomplished under the American SL (ASL) dataset. The comparison study of the PASLR-DDPFEM method revealed a superior accuracy value of 98.80% compared to existing models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), approximately 70 million people worldwide have hearing loss. A high number of people with hearing and speech impairments may struggle to write or read in everyday language1. SL is one of the non-verbal languages used by deaf people for day-to-day communication among themselves. SL primarily relies on gestures more than voice to convey messages, incorporating the use of facial expressions, finger shapes, and hand movements2. The following are the essential defects in this language: a limited vocabulary, difficulties in learning, and frequent hand movements. In addition to this, people who are not deaf and mute are unaware of SL, while disabled people face significant problems in communicating with individuals3. These individuals with disabilities need to utilize a device translator for communicating with able-bodied individuals, which is achieved through the development of glove equipment with electronic circuits and sensors4. Many efforts were made to create an SLR method last year. In SLR, there are two major classifications, namely continuous sign classification and isolated SL. The hidden Markov model (HMM) functions on continuous SLR, which allows the segmentation of an information stream5. The SLR design is characterized into two essential types depending on its input, namely vision-based and data glove-based6. Vision-based SLR methods use cameras to detect hand gestures. Glove-based SLR technique utilizes smart gloves to measure locations, velocity, orientation, and other parameters, which employ sensors and microcontrollers.

Computer vision (CV)-based SLR methods commonly depend on removing characteristics such as gesture detection, edge detection, shape detection, and skin colour segmentation, among others7. In recent years, the use of a vision-based approach has become increasingly common, utilizing input from a camera. Many of the studies in SLR depend on DL methods that were achieved on SLs, unlike any Indian SL8. Currently, these fields are gaining more popularity among scholarly experts. The past reporting work on SLR primarily depends on ML models. These techniques result in lower accuracy because they do not automatically remove characteristics9. Automatic feature engineering is the primary objective of DL methods. The idea behind this is to spontaneously study a group of attributes from raw information used to recognize SL by individuals with hearing loss10. A communication gap exists between hearing-impaired individuals and those who are speech-impaired, as well as the general populace. Conventional tools for bridging this gap, such as sensor-based gloves, can be costly, inconvenient, or limited in scope; hence, it becomes crucial for intelligent, real-time solutions to interpret SL naturally and accurately. DL is considered effective in this area, enabling systems to automatically learn intrinsic patterns in gestures and facial cues without manual feature extraction. Its success in image and sequence recognition makes it ideal for advancing disability detection and improving communication accessibility.

This paper proposes a Pathfinder Algorithm-based Sign Language Recognition System for Assisting Deaf and Dumb People Using a Feature Extraction Model (PASLR-DDFEM) approach. The aim is to enhance SLR techniques to help individuals with hearing challenges communicate effectively with others. Initially, the image pre-processing phase is performed by using the Gaussian filtering (GF) model to improve image quality by removing the noise. Furthermore, the PASLR-DDPFEM approach utilizes the SE-DenseNet model for feature extraction. Moreover, the Elman neural network (ENN) model is implemented for the SLR classification process. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed by using the Pathfinder Algorithm (PFA) model to enhance the classification performance of the ENN classifier. An extensive set of simulations of the PASLR-DDPFEM method is accomplished under the American SL (ASL) dataset. The key contribution of the PASLR-DDPFEM method is listed below.

-

The PASLR-DDPFEM model incorporates GF to enhance image quality and reduce noise in SL input images, thereby ensuring cleaner visual data. This process enhances the visibility of significant features, facilitating more precise feature extraction and ultimately improving the overall performance and reliability of the recognition system.

-

The PASLR-DDPFEM method employs the SE-DenseNet-based DL approach for efficient and discriminative feature extraction, capturing both spatial and channel-wise data. This enhances the model’s ability to focus on the most relevant features, resulting in improved recognition accuracy and robustness across varying SL image conditions.

-

The PASLR-DDPFEM approach utilizes the ENN technique for effective SLR classification, employing its feedback connections to capture temporal patterns. This enables the model to better comprehend sequential dependencies in sign gestures, improving classification accuracy and adaptability to dynamic inputs.

-

The PASLR-DDPFEM methodology utilizes the PFA model to tune ENN parameters, thereby enhancing overall classification accuracy by efficiently exploring the solution space. This optimization improves the convergence speed and stability of the ENN model, producing more reliable and precise SLR results.

-

Thus, a novel hybrid framework is introduced which is required for ASL as it effectively handles image noise, captures discriminative spatial-temporal features, adapts to gesture discrepancies, and optimizes model parameters for accurate and robust recognition. This unique integration leverages the strengths of each component to address threats in SLR. The model enhances accuracy, robustness, and adaptability, and the novelty is in the synergistic use of DL, recurrent networks, and metaheuristic optimization.

Literature of works

Rethick et al.11 presented an innovative model of online hand gesture detection and classification methods. CNN is utilized to present effective and intuitive methods of communication for individuals. The primary goal is to provide deaf individuals with access to real-world gesture recognition technology. This method utilizes a robust CNN framework, specifically designed for precise hand gesture detection, and trained on a meticulously curated dataset. Assiri and Selim12 developed a model by utilizing an Adaptive Bilateral Filtering (ABF) model for noise reduction, the Swin Transformer (ST) technique for effective feature extraction, a hybrid CNN and Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-BiLSTM) model for accurate classification, and the Secretary Bird Optimiser Algorithm (SBOA) for optimal hyperparameter tuning. Kumar, Reddy, and Swetha13 presented a reliable and real-time Hindi SL (HSL) recognition system by utilizing CNNs for spatial feature extraction and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for temporal sequence modelling of hand movements and facial expressions. Harshini et al.14 proposed an accurate SLR system by using ML models. Specifically, the Random Forest Classifier (RFC) is incorporated with a conversational AI (CAI) bot powered by the Google Gemini Model (GGM). Allehaibi15 presented a Robust Gesture SLR Utilizing Chicken Earthworm Optimiser with DL (RSLR-CEWODL) technique. The proposed approach utilizes the ResNet-101 method for feature extraction. For the optimum hyperparameter tuning process, the projected model leverages the CEWO model. Moreover, the presented model employs a whale optimizer algorithm (WOA) with a deep belief network (DBN) for SLR. Kumar et al.16 introduced a new technique for enhancing the detection of Indian SL (ISL) by integrating Deep CNN with physically intended aspects. It employs the capability of DL with CNN to autonomously attain distinctive features from unprocessed data. This model involves a multi-stage process, in which the deep CNN gathers progressive features from unprocessed ISL images. In contrast, the manually intended aspects provide additional data to improve the recognition process. Hariharan et al.17 developed a highly accurate American SL (ASL) recognition system by utilizing advanced image pre-processing techniques, a modified Canny edge detection for segmentation, and a Modified CNN (MCNN) based on the deep Residual Network 101 (ResNet-101) architecture for classification. Almjally and Almukadi18 proposed an advanced SLR system that utilizes bilateral filtering (BF) for noise reduction, ResNet-152 for feature extraction, and a Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) method for sequence modelling. The Harris Hawk Optimisation (HHO) technique is employed to tune the hyperparameters of the Bi-LSTM optimally.

Kaur et al.19 developed a real-time SL to speech conversion system by utilizing a pre-trained InceptionResNetV2 DL technique integrated with hand keypoint extraction techniques. The model is examined by using the ASL dataset. Almjally et al.20 introduced a model utilizing advanced image pre-processing techniques, including Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalisation (CLAHE) and Canny Edge Detection (CED). The model also incorporates multiple feature extractors, including ST, ConvNeXt-Large, and ResNet50, combined with a hybrid CNN and Bi-LSTM with Attention (CNN-BiLSTM-A) for precise classification. Jagdish and Raju21 proposed a technique by utilizing image processing and DL models, specifically CNN. Maashi, Iskandar, and Rizwanullah22 presented a Smart Assistive Communication System for the Hearing-Impaired (SACHI) methodology, utilizing BF for noise reduction, an improved MobileNetV3 for effective feature extraction, and a hybrid CNN with a Bi-directional Gated Recurrent Unit and Attention (CNN-BiGRU-A) method for accurate SLR. The Attraction-Repulsion Optimisation Algorithm (AROA) approach is used to tune the classifier’s hyperparameters optimally. Ilakkia et al.23 proposed a real-time ISL recognition system by utilizing DL techniques, specifically the Residual Network-50 (ResNet-50) architecture. Mosleh et al.24 introduced a bidirectional real-time Arabic SL (ArSL) translation system by utilizing transfer learning (TL) with CNNs and fuzzy string-matching techniques. Thakkar, Kittur, and Munshi25 presented a robust multilingual SL Translation (SLT) system by integrating advanced CV techniques like YOLOv5 for gesture detection, combined with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) models for machine translation across English, Hindi, and French. The model also used RF classifiers with frameworks such as OpenCV and MediaPipe. Dhaarini, Sanjai, and Sandosh26 developed a real-time SL Detection and Assistive System (SLDAS) by utilizing advanced CV techniques and the You Only Look Once version 10 (YOLOv10) object detection model. Choudhari et al.27 developed a platform-independent web application for real-time ISL recognition by utilizing a CNN with Leaky Rectified Linear Unit (Leaky ReLU) activation and Adam optimizer. Table 1 summarises the existing studies on SLR systems for assisting the deaf and dumb.

Though the existing studies are effectual in the SLR recognition process, several approaches depend on limited or domain-specific datasets, mitigating generalizability across diverse SLs. Various techniques lack robust handling of dynamic sequences and non-manual features such as facial expressions and real-time responsiveness is often compromised due to intrinsic architectures or high computational overhead. Most systems lack end-to-end bidirectional communication capabilities though the integration of DL techniques namely CNN, BiLSTM, and ST has illustrated promising results. A notable research gap exists in forming lightweight, scalable models optimized for edge deployment and cross-lingual adaptability. Furthermore, insufficient multimodal integration and limited interpretability in decision-making highlight further research gap in building inclusive and user-friendly SLR platforms.

Materials and methods

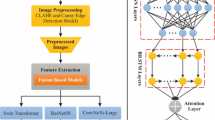

This paper designs and develops a PASLR-DDFEM technique. The primary objective is to enhance SLR techniques to help individuals with hearing challenges communicate effectively with others. To accomplish this, the PASLR-DDPFEM model involves several stages, including image pre-processing, feature extraction, classification, and parameter tuning. Figure 1 depicts the overall working flow of the PASLR-DDPFEM model.

Dataset description

Table 2 consists of 78,000 samples with 26 classes, representing the letters A–Z31. Each image is sized at 200 × 200 pixels, making it appropriate for training DL techniques in gesture recognition. The dataset al.so includes a small test set with real-world examples to promote robust model evaluation.

GF-based image pre-processing

Initially, the image pre-processing phase is performed using the GF model to enhance image quality by removing noise2. This model is chosen for its simplicity, efficiency, and efficiency in mitigating high-frequency noise while preserving crucial edge details in SL images. Unlike more complex filtering methods, the GF model presents a good balance between noise suppression and computational cost, making it appropriate for real-time applications. The technique helps improve the quality of input data without introducing distortions and also smoothens the image uniformly. This ensures that crucial gesture features remain intact for accurate downstream processing. Compared to median or bilateral filters, GF provides faster execution and consistent results. Its integration improves the reliability of feature extraction and overall recognition accuracy.

GF is a vital pre-processing stage in SLR for reducing noise and improving image quality while conserving essential features. It uses a Gaussian function to blur an image, minimizing high-frequency deviations that may occur due to illumination variations or sensor noise. This aids in improving feature extraction and edge detection by decreasing unwanted artefacts. The filter functions by conveying advanced weights to vital pixels and gradually declining weights to surrounding pixels, which ensures a natural smoothing effect. In SLR, GF enhances hand and gesture segmentation, which makes it simpler for ML methods to identify key patterns. Properly adjusting the Gaussian kernel size is crucial to strike a balance between reducing noise and preserving detail.

SE-DenseNet-based feature extraction model

Furthermore, the PASLR-DDPFEM method involves a feature extraction process, which is executed by the SE-DenseNet model28. This supervised DL method is chosen for its superior capability in capturing both spatial and channel-wise feature representations, improving the discriminative power of extracted features. The dense connectivity of the model promotes feature reuse. It reduces vanishing gradient issues, while the SE blocks adaptively recalibrate channel-wise responses, allowing the model to concentrate on the most informative features. Compared to conventional CNNs, SE-DenseNet presents enhanced efficiency and accuracy with fewer parameters. This integration yields richer feature hierarchies and improved generalization. Its integration ensures more robust and precise recognition of complex SL gestures under varying conditions.

DenseNet is an enhanced CNN-based model that calculates dense multiscale attributes from the object classifier’s convolution layer. This dense calculation of characteristics from the entire image may speed up training. This structure utilizes dense links, connecting the output of all layers to the input of all succeeding layers, thus decreasing the parameter counts and computing costs without influencing performance. The densely linked architecture improves the gradients and information flow; alleviating difficulties associated with vanishing gradients. The DenseNet’s basic notion is to achieve powerful feature representation and gradient propagation by minimizing information loss, thereby increasing the system’s performance. Equation (1) is applied to signify the initial layer input of DenseNet.

\(\:{H}_{l}\) denote a non-linear transformation function that consists of ReLU, convolutional, and batch normalization (BN) layers. \(\:[{x}_{0},\:{x}_{1},\:{x}_{2},\dots\:,\:{x}_{l-1}]\) signifies coordinated output from layers \(\:0\) to layer \(l-1\). This structure typically comprises Dense-Block and Transition modules that utilize dense links and smaller parameters to mitigate computational complexity. The transition unit includes Pooling, BN, Convolution, and ReLU layers. This Transition component connects adjacent dense blocks and reduces the feature mapping size over the pooling layer, underscoring the significance of higher-level feature representation in improving compression efficacy. The DenseNet model contains 4 DenseBlock units and 3 Transition components.

Attention mechanism (AM) is a data processing model in ML, which is extensively utilized in different areas of DL recently. AMs are separated into mixed-domain, spatial, and channel attentions. During this work of channel attention, a novel framework was developed, concentrating on channel relations in CNNs and presented a novel structural component named “Squeeze and Excitation” (SE) blocks, which dynamically adjusts the feature remarks about channels by mimicking their interdependence. They considered the nondimensionality-decreasing local cross-channel interaction tactic and an adaptive model to select the dimensions of 1D convolutional kernels, thereby achieving performance growth. This study utilizes SENet for learning global feature information and remarkably improves the main characteristics. Initially, input \(\:X\) is converted into feature \(\:U\) using the transformation \(\:{function\:F}_{tr}\), where \(\:X\in\:{R}^{h\times\:w\times\:{c}_{1}}\) and \(\:U\in\:{R}^{h\times\:w\times\:{c}_{2}}.\).

Then, the squeezing module \(\:{F}_{sq}\) utilizes the global average pooling to condense the feature \(\:U\) into \(\:{R}^{1\times\:1\times\:{c}_{2}}\), demonstrating the global supply of replies on the feature networks. Formerly, \(\:{F}_{ex}(\bullet\:,w)\) creates weights for every feature channel utilizing parameter \(\:w\). By re-weighting, the excitation output weight was determined as the significance of all feature channels. At last, the weights are utilized for the preceding feature channels to recalibrate the new features.

This study proposes an original network method, named SE-DenseNet for SLR, which primarily consists of four DenseBlocks, three Transitions, and three SENets. The input model is \(\:H\in\:{R}^{T\times\:E\times\:C}.\) To speed up convergence and prevent gradient vanishing issues, this work carried out either the activation function BN or the process after every 2D convolution. The component in the DenseNet model presents a hyperparameter named growth rate, which is assigned a value of 12. This parameter controls the channel counts added in all convolutional layers, allowing the system to get the balance between model performance and complexity. All DenseBlocks are made from numerous Bottleneck layers. Every Bottleneck is created from a ReLU, a 1 × 1convolutional layer, a BN layer, a \(\:3\)x\(\:3\) convolutional layer, a ReLU, and\(\:\:a\:BN\) layer sequentially. The DenseNet network, containing 4 DenseBlock units and 3 Transition modules, is rejected by seven successive processes: ReLU, BN layer, BN layer, ReLU,\(\:\:1\)x\(\:1\) convolutional layer, Dropout layer, and \(\:3\text{x}3\) convolutional layer. The Dropout layer aims to prevent overfitting. Inserting SENet among Transition and DenseBlock for learning the significance of every channel and improving valuable performance.

ENN-based classification model

Moreover, the ENN model is employed for the SLR classification process29. This model is chosen for its dynamic memory capability, which effectively captures temporal dependencies in sequential data, such as SL gestures. This technique comprises context units that retain data from prior time steps, making it appropriate for recognizing patterns over time, unlike feedforward networks. This is specifically beneficial in SLR, where gestures follow a temporal sequence. Compared to conventional classifiers such as SVM or basic CNNs, ENN presents an enhanced performance on time-series data without requiring intrinsic architectures. Its ability to model contextual information results in more accurate and consistent classification results. Figure 2 portrays the structure of the ENN technique.

ENNs are an ML approach that is designed for processing time-independent data. Unlike conventional feedforward NNs, ENNs have relations that make managed cycles, permitting them to maintain a model of sequential data efficiently.

The advanced ENN consists of four layers: the input layer, denoted as \(\:i\), \(\:j\), representing the hidden layer (HL), the context layer, specified as \(\:c\), and the output layer, embodied as \(\:0\). Every layer is linked utilizing weight. The \(\:ith\) layer is provided with the hydrologic inputs. The \(\:ith\) layer includes ten hidden neurons. The advanced ENN method contains \(\:a\:c\) layer that is otherwise recognized as a layer of feedback. The objective of the \(\:c\) layer is to maintain the data from the previous stage, which assists in examining the patterns from the preceding data. The training and functional procedure are provided as shown.

The node in this layer and the input layer are specified as:

Whereas \(\:{x}_{i}^{\left(1\right)}\left(n\right)\) denotes the output data of \(\:the\:ith\) layer. The node in the \(\:ith\) layer is provided as:

The function of the sigmoid, \(\:S\left(x\right)=1/1+e-x\), was utilized in NNs for mapping input values to the range between \((0\),1) that might characterize possibilities. It was distinguishable and had a basic derivative,

The \(\:ith\) layer is linked utilizing the neuron with weightings \(\:{w}_{l\mathfrak{j}}\), and \(\:{w}_{k\mathfrak{j}}\) represents neuron weights. The nodes in these contextual layers are provided as:

From Eq. (6), \(\:\alpha\:\) refers to the gain of feedback that is located between\(\:\:0\le\:\alpha\:\le\:1.\) The node in the output layer was signified as:

\(\:{\gamma\:}_{l}^{\left(4\right)}\left(n\right)\) Provides the forecast output of the presented method. The weighting update of the advanced ENN-based forecasting method occurs layer‐to-layer; the weighted upgrade of linking neuron weight \(\:{w}_{\mathfrak{j}l}\) is provided as:

In a weighted update, \(\:{\xi\:}_{1}\) characterizes the rate of training of the zero layer. The novel weight of \(\:{w}_{k\mathfrak{j}}\) is provided as:

In the weight update, \(\:{\xi\:}_{2}\) embodies the rate of training of the \(\:ith\) layer. The novel weight of \(\:{w}_{ij}\) is specified as:

In the weight update, \(\:{\xi\:}_{3}\) refers to the rate of training of an input layer. The advanced ENN method was trained utilizing the backpropagation (BP) model, an expansion of the normal BP model applied in feedforward NNs. The BP methods consider the temporal dependences by describing the network over time and fine-tuning weights as a result.

PFA-based parameter tuning model

Ultimately, the parameter tuning process is conducted using the PFA model to enhance the classification performance of the ENN classifier30. This model is chosen for its robust global search capability, fast convergence, and ability to avoid local optima during optimization. This technique is inspired by the collective movement of agents in a search space. Additionally, it demonstrates efficiency in balancing exploration and exploitation, making it ideal for fine-tuning intrinsic models, such as ENN. Compared to conventional methods such as grid search or other metaheuristics, namely PSO or GA, PFA illustrates better stability and solution quality in high-dimensional spaces. Its adaptability and computational efficiency improve the overall performance of the classification model. This results in a more accurate and reliable SLR.

PFA simulates the random behaviour and drive of the animal, which emulates its head to a neighbouring site in search of sustenance or prey. Modifications in a leader are probable while the goal of searching is not accomplished. The head of a group and its competitors collaborate to determine the most effective path to the destination. Depending on the direction and force in the multidimensional region, the path’s direction is improved. At some point, the contestant in the optimum position is considered the swarm’s head. This candidate is specified as the Pathfinder. During these existing iterations, Pathfinder and its location are viewed as the finest solution, and another competitor acquires it. A vector representing the movement position of competitors in multiple sizes is employed to manage the recommended solutions. To control how the rival performs in the exploration phase, four parameters are adjusted. Every cycle concurrently creates the vibration of competitor \(\:\nu\:\) and oscillating frequency \(\:\tau\:\). The attraction factor \(\:\alpha\:\) fine-tunes the random area of separation, and the communication factor \(\:\sigma\:\) upholds the movement regarding the neighbouring competitor.

The term \(\:C\) indicates the vector for a position, \(\:d\) signifies the identity vector, \(\:{K}_{J}\) specifies the force that is reliant on the position of the Pathfinder, \(\:i\) specifies the period, and \(\:{E}_{f}\) is the communication that arises between dual rivals \(\:{C}_{k}\) and \(\:{c}_{f}\).

The term \({\Delta}c\) represents the value assessed by deliberating the region among the dual diverse locations of the Pathfinder, and \(\:{C}_{J}\) is the vector position of the Pathfinder.

The terms \(\:{\overrightarrow{Q}}_{1}\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{{Q}_{2}}\) are dual vectors of the trajectory in arbitrary coordinates. The value of \(\:{\overrightarrow{Q}}_{1}=\alpha\:\cdot\:{q}_{1}\) and \(\:{\overrightarrow{Q}}_{2}=\sigma\:\cdot\:{q}_{2}\), where\(\:{\:q}_{1}\) and \(\:{q}_{2}\) indicate the arbitrary movement created homogeneously. The values of \(\:{q}_{1}\) and \(\:{q}_{2}\) range from (− 1, 1). The term \(\:\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:f\end{array}\) and \(\:\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:k\end{array}\) the vector position of dual rival \(\:f\) and \(\:k\) at the existing iteration \(\:0\). The value of \(\:\nu\:\) is described.

The term \(\:O\) is the suggested maximum number of iterations, \(\:0\) specifies the existing iteration, and \(\:{N}_{os}\) is the separation distance between the dual rivals. The factor of attraction \(\:\alpha\:\) and the factor of communication \(\:\sigma\:\) values are altered. Every rival moves randomly and independently within the region, whereas \(\:\sigma\:\) and \(\:\alpha\:\) equal \(\:0\). Every rival stop moving and loses the path of the swarm’s head while \(\:\sigma\:\) and \(\:\alpha\:\) are equal to \(\:\infty\:\). If \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\sigma\:\) are both lower than 1 and higher than 2, then an affiliate rival cannot generate an optimum solution. Thus, it is significant that the value of \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\sigma\:\) must be (1, 2).

The term \(\:{q}_{3}\) represents an arbitrary vector of rivals. Whether the terms \(\:{\overrightarrow{Q}}_{1}*\left(\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:k\end{array}-\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:f\end{array}\right)\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{{Q}_{2}}*\left(\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:j\end{array}-\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:f\end{array}\right)\) in Eq. (11) or the term \(\:2{q}_{3}\cdot\:\left(\begin{array}{c}\to\:o\\\:C\\\:j\end{array}-\begin{array}{c}\to\:o-1\\\:C\\\:j\end{array}\right)\) become zero, subsequently \(\:\tau\:\) and \(\:\nu\:\) can randomly move each rival with proper values through various paths. The oscillating frequency \(\:\tau\:\) is calculated.

The term \(\:{p}_{2}\) signifies an arbitrary value within \(\:(-1,\:1)\). The convergence and divergence of PFA are derived from the values \(\:\tau\:\) and \(\:\nu\:\). It can accelerate or slow down the technique. To accomplish this without diverging among them in every iteration, values \(\:\nu\:\) and \(\:\tau\:\) must be (1, 2). The contestant can quickly leave their locations without discovering a solution if either \(\:{p}_{1}\) or \(\:{p}_{2}\) is beyond the range [− 1, 1].

The PFA model generates a fitness function (FF) for achieving improved classification performance. It describes a positive number to describe the better efficiency of the candidate solution. Here, the classification rate of error reduction is designated as FF, as defined in Eq. (16).

Proposed methodology

The performance evaluation of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique is examined under the ASL dataset31. The method runs on Python 3.6.5 with an Intel Core i5-8600 K CPU, 4GB GPU, 16GB RAM, 250GB SSD, and 1 TB HDD, using a 0.01 learning rate, ReLU activation, 50 epochs, 0.5 dropout, and a batch size of 5. The chosen dataset includes signs performed under varied conditions such as diverse hand positions, lighting, and backgrounds, assisting the dataset capture some real‑world variation in gesture appearance for robust model training and evaluation.

In Table 3; Fig. 3, a brief overview of the overall SLR outcome for the PASLR-DDPFEM approach is presented, covering 70% of the training phase (TRAPA) and 30% of the testing phase (TESPA). The tabulated values indicate that the PASLR-DDPFEM methodology accurately identifies the 26 samples. The results suggest that the PASLR-DDPFEM approach can effectively recognize the samples. For under 70% of TRAPA, the PASLR-DDPFEM method obtains an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:sen{s}_{y}\), \(\:spe{c}_{y}\), \(\:{F1}_{score}\), and Kappa of 98.80%, 84.44%, 84.42%, 99.38%, 84.42%, and 84.48%, respectively. Likewise, under 30% of TESPA, the PASLR-DDPFEM method obtains an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:sen{s}_{y}\), \(\:spe{c}_{y}\), \(\:{F1}_{score}\), and Kappa of 98.79%, 84.29%, 84.27%, 99.37%, 84.26%, and 84.33%, respectively.

In Fig. 4, the TRA \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) (TRAAY) and validation \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) (VLAAY) analysis of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique is illustrated. The figure highlights that the TRAAY and VLAAY values exhibit a rising trend, indicating the model’s ability to achieve higher performance over various iterations. Additionally, the TRAAY and VLAAY remain closer throughout an epoch, which results in minimal overfitting and optimal performance of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique.

In Fig. 5, the TRA loss (TRALO) and VLA loss (VLALO) curve of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach is displayed. The TRALO and VLALO analyses exemplify a decreasing trend, indicating the capacity of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach in balancing trade-offs. The constant decrease also guarantees the enhanced performance of the PASLR-DDPFEM model.

In Fig. 6, the PR graph analysis of the PASLR-DDPFEM methodology provides clarification into its results by plotting Precision beside Recall for every class label. The steady rise in PR values across all class labels depicts the efficacy of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach in the classification process.

In Fig. 7, the ROC analysis of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach is examined. The results suggest that the PASLR-DDPFEM technique achieves optimal ROC results across all classes, effectively representing the vital capacity to distinguish between class labels. This dependable tendency of better values of ROC across several class labels signifies the proficient efficiency of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique on predicting class labels, highlighting the classification procedure.

To demonstrate the proficiency of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique, a comprehensive comparison study is presented in Table 432,33.

In Fig. 8, a comparative \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), and \(\:F{1}_{score}\) results of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique are provided. The results indicate that the SignLan-Net, EfficientNet V2, and MobileNetV2 methodologies have shown worse values of \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), and \(\:F{1}_{score}\). At the same time, the VGG16 and Inception V3 methods have achieved slightly maximal \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), and \(\:F{1}_{score}\). Meanwhile, the Faster R-CNN and CNN methodologies have established closer values of \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), and \(\:F{1}_{score}\). However, the PASLR-DDPFEM approach results in optimal performance with \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), and \(\:F{1}_{score}\) of 98.80%, 84.44%, and 84.42%, respectively.

In Fig. 9, a comparative \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) and \(\:spe{c}_{y}\) results of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach are provided. The results indicate that the CNN, Faster R-CNN, and VGG16 techniques have shown lower values of \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) and \(\:spe{c}_{y}\). At the same time, the EfficientNet V2 and SignLan-Net approaches have achieved slightly maximum \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) and \(\:spe{c}_{y}\). Meanwhile, the Inception V3 and MobileNetV2 techniques have established closer values of \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) and \(\:spe{c}_{y}\). On the other hand, the PASLR-DDPFEM model results in superior performance, with \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) and \(\:spe{c}_{y}\) of 84.42% and 99.38%, respectively.

Table 5; Fig. 10 present the computational time (CT) analysis of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach compared to existing methods. The CT clearly demonstrates the efficiency of the PASLR-DDPFEM approach, which records the lowest CT of 6.34 s among all evaluated models. In contrast, conventional models like the CNN and VGG16 require 22.35 and 21.78 s, respectively, reflecting significantly higher CTs. EfficientNet V2 and Faster R-CNN exhibit enhanced performance with CT values of 11.19 and 12.62 s, while MobileNetV2 and Inception V3 require 20.81 and 19.78 s. SignLan-Net performs well with 9.95 s, yet the PASLR-DDPFEM method outperforms all others, presenting a reduction of over 70% in CT compared to the highest value, making it highly appropriate for real-time applications.

Table 6; Fig. 11 present the error analysis of the PASLR-DDPFEM methodology in comparison to existing models. The evaluation results indicate that the PASLR-DDPFEM methodology, with an \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 1.20%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 15.56%, \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) of 15.58%, \(\:spe{c}_{y}\) of 0.62%, and \(\:F{1}_{score}\) of 15.58%, illustrates relatively lower performance compared to other approaches. For instance, SignLan-Net demonstrates the highest \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 15.28% and a robust \(\:F{1}_{score}\) of 24.14%, while EfficientNet V2 achieves an \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 13.08% and a \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 24.72%. Although the PASLR-DDPFEM model maintains a consistent balance between \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) and \(\:sen{s}_{y}\), its overall \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) and \(\:spe{c}_{y}\) remain limited. This suggests that the model may struggle to distinguish between certain sign classes effectively, and further optimization may be necessary. The error analysis highlights the importance of deeper feature learning and better class representation to improve recognition results.

Table 7 depicts the ablation study of the PASLR-DDPFEM technique. Without PFA tuning, the ENN with GF preprocessing and SE-DenseNet feature extraction attained an \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.18%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 83.79%, \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) of 83.65%, \(\:spe{c}_{y}\) of 98.77%, and \(\:F{1}_{score}\) of 83.71%. By combining the PFA tuning resulted with an \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.80%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 84.44%, \(\:sen{s}_{y}\) of 84.42%, \(\:spe{c}_{y}\) of 99.38%, and \(\:F{1}_{score}\) of 84.42%, highlighting the efficiency of the tuning process in improving the overall performance.

Table 8 illustrates the computational efficiency of diverse object detection models34. The PASLR-DDPFEM methodology exhibits the lowest Floating-Point Operations (FLOPs) at 4.09 G, minimal Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) memory usage of 589 MB, and the fastest inference time of 1.07 s, significantly outperforming YOLOv3-tiny-T, ShuffleNetv2-YOLOv3, YOLOv5I, and YOLOv7 in terms of both speed and resource efficiency.

Conclusion

This paper designs and develops a PASLR-DDFEM model. The aim is to enhance SLR techniques to help individuals with hearing challenges communicate with others. Initially, the image pre-processing phase is performed using the GF model to improve image quality by removing noise. Furthermore, the PASLR-DDPFEM method is employed by the SE-DenseNet model for the feature extraction process. Moreover, the ENN method is used for the SLR classification process. Finally, the parameter tuning process is performed through PFA to improve the classification performance of the ENN classifier. An extensive set of simulations of the PASLR-DDPFEM method is accomplished under the American SL (ASL) dataset. The comparison study of the PASLR-DDPFEM method revealed a superior accuracy value of 98.80% compared to existing models. This method can be deployed in real-time applications due to optimized feature extraction and tuning, enabling fast and accurate gesture recognition suitable for mobile and embedded devices. The limitations of the PASLR-DDPFEM method comprise the dependence on a single dataset, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings across diverse SL discrepancies and real-world conditions. Furthermore, the model’s performance could be affected by varying lighting conditions and complex backgrounds that were not extensively addressed. The existing approach also fails to integrate multimodal inputs, such as depth or motion data, which could enhance recognition accuracy. Computational needs, although optimized, may still pose threats for deployment on low-resource devices. Furthermore, user-specific adaptability and personalized learning were not explored. Addressing these limitations could open new avenues to improve robustness, inclusivity, and practical applicability in future research. Also, integrating multimodal cues such as facial expressions and lip movements could additionally improve the accuracy of recognition by providing further contextual data to discrimintate similar gestures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/grassknoted/asl-alphabet](https:/www.kaggle.com/datasets/grassknoted/asl-alphabett), reference number [32].

References

Wadhawan, A. & Kumar, P. Deep learning-based sign Language recognition system for static signs. Neural Comput. Appl. 32 (12), 7957–7968 (2020).

Cheok, M. J., Omar, Z. & Jaward, M. H. A review of hand gesture and sign Language recognition techniques. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet. 10, 131–153 (2019).

Adaloglou, N. et al. A comprehensive study on deep learning-based methods for sign Language recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimedia. 24, 1750–1762 (2021).

Rastgoo, R., Kiani, K. & Escalera, S. Hand sign language recognition using multi-view hand skeleton. Expert Systems with Applications, 150, p.113336. (2020).

Katoch, S., Singh, V. & Tiwary, U. S. Indian Sign Language recognition system using SURF with SVM and CNN. Array, 14p.100141. (2022).

Lee, C. K. et al. American Sign Language recognition and training method with recurrent neural network. Expert Systems with Applications, 167 p.114403. (2021).

Sharma, S. & Singh, S. Vision-based hand gesture recognition using deep learning for the interpretation of sign language. Expert Systems with Applications, 182p.115657. (2021).

Al-Hammadi, M. et al. Deep learning-based approach for sign language gesture recognition with efficient hand gesture representation. Ieee Access, 8, pp.192527–192542. (2020).

Camgoz, N. C., Koller, O., Hadfield, S. & Bowden, R. Sign language transformers: Joint end-to-end sign language recognition and translation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 10023–10033). (2020).

Abdel-Jaber, H., Devassy, D., Al Salam, A., Hidaytallah, L. & El-Amir, M. A review of deep learning algorithms and their applications in healthcare. Algorithms, 15(2), p.71. (2022).

Rethick, R. S. et al. February. Deep learning-driven recognition and categorization of hand gestures for individuals with hearing and speech disabilities. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 3204, No. 1). AIP Publishing. (2025).

Assiri, M. S. & Selim, M. M. A swin transformer-driven framework for gesture recognition to assist hearing impaired people by integrating deep learning with secretary bird optimization algorithm. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 16(6), p.103383. (2025).

Kumar, M. M., Reddy, P. D. K. & Swetha, P. National sign Language real-time recognition to speech and text for deaf and dumb patient interaction. In Recent Trends in Healthcare Innovation (292–300). CRC. (2025).

Harshini, P. J., Rahman, M. A., Raj, J. A. & Durgadevi, P. May. Sign Language Recognition System for Seamless Human-AI Interaction. In International Research Conference on Computing Technologies for Sustainable Development (pp. 124–144). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. (2024).

Allehaibi, K. H. Artificial intelligence based automated sign gesture recognition solutions for visually challenged people. Journal Intell. Syst. & Internet Things, 14(2). (2025).

Kumar, K. D., Ragul, K., Kumar, G. P. P. & Kumar, G. K. April. Enhancing Sign Language Recognition through Deep CNN and Handcrafted Features. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Networking and Communications (ICNWC) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024).

Hariharan, U. et al. Recognition of American sign Language using modified deep residual CNN with modified canny edge segmentation. Multimedia Tools Applications, pp.1–28. (2025).

Almjally, A. & Almukadi, W. S. Deep computer vision with artificial intelligence based sign language recognition to assist hearing and speech-impaired individuals. Scientific Reports, 15(1), p.32268. (2025).

Kaur, B., Chaudhary, A., Bano, S., Yashmita, Reddy, S. R. N. & Anand, R. Fostering inclusivity through effective communication: Real-time sign Language to speech conversion system for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83 (15), 45859–45880 (2024).

Almjally, A., Algamdi, S. A., Aljohani, N. & Nour, M. K. Harnessing attention-driven hybrid deep learning with combined feature representation for precise sign language recognition to aid deaf and speech-impaired people. Scientific Reports, 15(1), p.32255. (2025).

Jagdish, M. & Raju, V. Multimodal Sign Language Recognition System: Integrating Image Processing and Deep Learning for Enhanced Communication Accessibility. International Journal of Performability Engineering,20 (5), p.271. (2024).

Maashi, M., Iskandar, H. G. & Rizwanullah, M. IoT-driven smart assistive communication system for the hearing impaired with hybrid deep learning models for sign language recognition. Scientific Reports, 15(1), p.6192. (2025).

Ilakkia, A., Kanchanadevi, P., Abirami, A., Rajan, R. & Muthukumaran, K. December. Sign Comm: A Real-Time Indian Sign Language Recognition System Using Deep Learning for inclusive communication. In 2024 International Conference on Emerging Research in Computational Science (ICERCS) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. (2024).

Mosleh, M. A., Mohammed, A. A., Esmail, E. E., Mohammed, R. A. & Almuhaya, B. Hybrid Deep Learning and Fuzzy Matching for Real-Time Bidirectional Arabic Sign Language Translation: Toward Inclusive Communication Technologies. IEEE Access. (2025).

Thakkar, R., Kittur, P. & Munshi, A. June. Deep Learning Based Sign Language Gesture Recognition with Multilingual Translation. In 2024 International Conference on Computer, Electronics, Electrical Engineering & their Applications (IC2E3) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024).

Dhaarini, G., Sanjai, R. & Sandosh, S. May. Real-Time Sign Language Detection and Assistive System Using YOLOv10 for Enhanced Communication and Learning. In 2025 7th International Conference on Energy, Power and Environment (ICEPE) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2025).

Choudhari, J., Bhagwat, S., Kundale, J. & Raorane, A. December. Real-Time Sign Language Recognition and Communication: Leveraging CNN for Deaf and Mute Communities. In 2024 International Conference on Innovation and Novelty in Engineering and Technology (INNOVA) (Vol. 1, pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024).

Xiang, Y., Zheng, W., Tang, J., Dong, Y. & Pang, Y. Gesture recognition from surface electromyography signals based on the SE-DenseNet network. Biomedical Engineering/Biomedizinische Technik, (0). (2025).

Wang, L. & Wang, L. Analysis and prediction of landslide deformation in water environment based on machine algorithm. Hydrology Research, p.nh2025098. (2025).

Sundaramoorthy, R. A. et al. Implementing heuristic-based multiscale depth-wise separable adaptive temporal convolutional network for ambient air quality prediction using real time data. Scientific Reports.14 (1), p.18437. (2024).

Kothadiya, D. R., Bhatt, C. M., Rehman, A., Alamri, F. S. & Saba, T. SignExplainer: an explainable AI-enabled framework for sign Language recognition with ensemble learning. IEEE Access. 11, 47410–47419 (2023).

Nareshkumar, M. D. & Jaison, B. A Light-Weight deep Learning-Based architecture for sign Language classification. Intelligent Autom. & Soft Computing, 35(3). (2023).

Chen, R. & Tian, X. Gesture detection and recognition based on object detection in complex background. Applied Sciences. 13 (7), p.4480. (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman center For Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024- 438.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Centre for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no. KSRG-2024- 438.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nadhem NEMRI: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, Mohammed Yahya Alzahrani: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editingWided Bouchelligua: methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparationAmani A Alneil: software, visualization, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nemri, N., Alzahrani, M.Y., Bouchelligua, W. et al. Improving sign Language recognition system for assisting deaf and dumb people using pathfinder algorithm with representation learning model. Sci Rep 16, 4182 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34283-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34283-x