Abstract

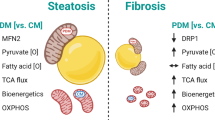

Mitochondrial function is crucial for hepatic lipid metabolism. Current research identifies two types of mitochondria based on their contact with lipid droplets: peridroplet mitochondria (PDM) and cytoplasmic mitochondria (CM). This work aimed to investigate the alterations of CM and PDM in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) induced by spontaneous type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in db/db mice. It was found that insulin resistance increased both the number and size of lipid droplets in the liver by enhancing the accumulation of free fatty acids, which is accompanied by an increase in contacts with mitochondria. We described the different patterns of tight contacts between small lipid droplets and mitochondria in purified CM and PDM by examining their oxidation states and morphological characteristics. In CM, enhanced fatty acid oxidation resulted in elongated mitochondria that surrounded single small lipid droplets and were responsible for lipid droplet consumption, while in PDM, increased substrates for lipid synthesis promoted lipid droplet expansion with the assistance of the endoplasmic reticulum. These data show the different ways in which mitochondrial contact with lipid droplets could provide new insights for future research on liver lipid metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The liver is the front line and core site of energy metabolism in the body, wherein nutrients such as sugars, fats, proteins, and their derivatives converge and are transformed1; 2. Both clinical and basic research show that fatty acid metabolic disorders are closely related to the occurrence of liver diseases3. This is exemplified by type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), in which increased insulin resistance leads to increased blood glucose and fatty acid levels4. Furthermore, dysregulation of insulin signaling in hepatocytes results in increased production of acetyl coenzyme A and hepatic proteins associated with fatty acid synthesis via heightened glycolytic activity, leading to de novo fatty acid synthesis and subsequent fatty acid overload5; 6. In response, hepatocytes accelerate lipid synthesis to store the excess fatty acid, alleviating the resultant aggregation and toxicity7. This may be an important mechanism by which T2DM causes lipid deposition and eventually leads to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). However, the mechanism of lipid droplet formation and growth during T2DM-induced hepatic lipid deposition needs further investigation.

In cells, lipid metabolism, which is mediated by the interaction of organelles involved in lipid droplet formation, regulates the regeneration, growth, fusion, and degradation of lipid droplets. For example, mitochondria may facilitate lipid synthesis or oxidation8. Recent research has demonstrated that there is physical contact between mitochondria and lipid droplets in many different kinds of cells9,10,11, triggering more focused research into the mechanisms behind this physical connection. Mitochondria are thought to be “energy processors” in cells that use fatty acids as substrates to produce ATP, while lipid droplets are known as “warehouses” that store fatty acids12. The physical combination of these two organelles might improve the efficiency of fatty acid energy supply13. In mitochondria, abundant acetyl coenzyme A and ATP can synthesize malonyl-CoA via the enzymatic action of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, resulting in the subsequent synthesis of triglycerides (TG) in lipid droplets14. As a result, contact with mitochondria may promote the expansion of lipid droplets9. Moreover, these two distinct mitochondrial lipid metabolism mechanisms could take place simultaneously in the liver. Physical contact between mitochondria and lipid droplets was observed in both energy-consuming organs fueled by fatty acids, such as the hearts and muscles15, and energy-storage organs that could store fatty acids, such as adipose16. Whether or not the mechanisms behind this connection can switch from lipid synthesis under energy surplus to lipid oxidation under energy deficiency requires further investigation.

Previous studies have separated peridroplet mitochondria (PDM) from cytoplasmic mitochondria (CM) in hepatic tissue through differential centrifugation17. Analysis of their morphology and function have shown that CM are mainly used in ATP synthesis and maintenance of normal cellular energy metabolism while PDM play a small role in fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and may function in lipid droplet amplification18. Furthermore, lipid droplet and mitochondria (LD-Mito) contacts were enhanced in the high-fat diet-induced MASLD model, and inhibition of the carnitine palmitoyl transferase system decreased FAO capacity in PDM, suggesting an enhancement in lipid synthesis19. However, much about the morphology of LD-Mito contacts in the liver has yet to be described, such as the characteristics of lipid droplets and mitochondria, the method of binding, and the degree of closeness17. These morphological differences in LD-Mito contacts may imply functional differences. Moreover, the oxidative state of CM and PDM in T2DM-induced MASLD has not been studied. In this work, we aimed to investigate whether LD-Mito contacts increased during T2DM-induced lipid deposition in the liver and focused on the morphological details of the LD-Mito contacts as a means of exploring the underlying mechanisms.

Results

Insulin resistance induced hepatic lipid deposition in db/db mice

To establish hepatic lipid deposition, we used the db/db mice model, which harbors a mutation in the diabetes (db) gene encoding the leptin receptor (ObR) and exhibites impaired leptin signaling closely related to liver lipid metabolism20. After eight weeks of ad libitum feeding with a standard diet, the db/db mice exhibited a significant increase in body weight (Fig. S1a) and blood glucose (Fig. S1b), alongside a marked decrease in insulin sensitivity (Fig. S1c, d). This indicated that the db/db mice had a serious disturbance in glucose and lipid metabolism, which led to an abnormal increase in blood lipid levels. Studies showed that after binding insulin in the liver, the insulin receptor autophosphorylated and went on to phosphorylate several insulin receptor substrates, thereby activating classical IRS signaling pathways, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-phosphatidylinositol-dependent kinase (PDK)-protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway21. However, we found that protein levels of p-PI3K/PI3K and p-AKT/AKT were significantly lower in the livers of diabetic mice than in the livers of db/m mice, as detected by western blotting (Fig. 1a–h). This resistance led to decreased glucose utilization, increased fatty acid uptake, and more severe hepatic lipid deposition.

Insulin resistance and lipid deposition were observed in the liver of db/db mice. (a) Representative western blot maps of IR protein and original blots are presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 1. (b) Protein level of IRβ. (c) Protein level of PI3K. (d) Protein level of P-PI3K. (e) Expression level of p-PI3K/PI3K. (f) Protein level of AKT. (g) Protein level of p-AKT. (h) Expression level of p-AKT/AKT. (i) Representative images of liver tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Oil Red O (scale bars = 50 μm) are shown. (j) Fat drop area (%). (k) FFA content in the liver. (l) Hepatic levels of TGs. (m) Liver index. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 (2 images analyzed per sample for Oil Red O-stained images). n = 8 per group (western blotting, liver FFA, TG, and liver index analyses). Student’s t-test was performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Hepatic free fatty acids (FFA), TG, and liver indices of the db/db mice were significantly increased compared with the db/m group (Fig. 1k–m). The livers of db/m mice were bright red with sharp edges. By contrast, the livers of db/db mice had increased volume, a greasy texture, a lighter color, and blunted edges. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that db/m mice had normally structured hepatic tissue with well-arranged cells, uniformed cytoplasm, and central nuclear position, whereas db/db mice had hepatic tissue with a disordered structure, with ballooned hepatocytes, numerous vacuoles, and extruded nuclei. Oil Red O staining revealed that the numerous big vacuoles in db/db mice hepatic tissue nearly filled up the entire cytoplasm (Fig. 1i, j) and were probably red-stained lipid droplets. Similarly, we found that in the db/db mice, the levels of serum cholesterol (CHOL), TG, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and FFA were significantly increased (P < 0.05) compared to those in the db/m group (Table 1). These findings further supported the presence of increased lipid accumulation in the liver of the db/db mice compared to the wild-type group. In summary, our observations demonstrated that the liver of db/db mice exhibited significant insulin resistance, enhanced lipid deposition, and a substantial increase in the size and number of lipid droplets.

Increased LD-Mito contacts in isolated primary hepatocytes and fat layer in db/db mice liver

In previous studies, researchers had used LipidTOX or BODIPY and Mito-tracker as fluorescent dyes for staining lipid droplets and mitochondria to demonstrate their interaction in primary adipose cells18. These interactions have been demonstrated in fat layers (FL) from rat livers, but not yet in hepatocytes. We isolated primary hepatocytes by collagenase perfusion on livers22, and used BODIPY and Mito Tracker to stain lipid droplets and mitochondria and looked for contact between them. In normal hepatocytes, the rod-shaped mitochondria were distributed uniformly throughout the cytoplasm, among which a few small lipid droplets were submerged, with no obvious contact between the lipid droplets and mitochondria. By contrast, in db/db mice hepatocytes, some of the large lipid droplets competed with mitochondria for space within the cytoplasm, with some of these droplets being surrounded by rod-shaped mitochondria (Fig. 2a, b). This phenomenon was also evident in the 3D images obtained from confocal microscopy (Fig. S2). TEM results that showed that in normal mice livers, lipid droplets were relatively few and were scattered in the cytoplasm with few mitochondrial contacts. In contrast, the livers of db/db mice contained numerous large lipid droplets, accompanied by a significant increase in mitochondrial contacts. TEM also revealed that the length and curvature of mitochondria bound to lipid droplets had increased (Fig. 2c-f).

Increased LD-Mito contacts in isolated primary hepatocytes and hepatic tissue in db/db mice livers. (a) Representative images of mitochondria and LDs in primary hepatocytes are shown (scale bars = 20 μm). LDs were marked by the neutral BODIPY 493/503 fluorescent dye (BODIPY) and mitochondria by MitoTracker deep red dye (MitoTracker). (b) Percentage area of lipid droplets in primary hepatocytes. (c) TEM images of lipid droplets and mitochondria in the liver. Red, mitochondria; green, LDs. (d) Percentage of total mitochondria in contact with lipid droplets. (e) The ratio of the length of LD-Mito contacts to the perimeter of LD. (f) The ratio of the length of LD-Mito contact to the perimeter of mitochondria. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 (2–3 images analyzed per sample for fluorescent images and micrographs). Student’s t-test was performed. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To characterize the features of LD-Mito contacts in livers in both db/m and db/db mice, hepatic tissues were milled and centrifuged at 900 xg to separate the lipid layer (FL) according to Ngo’s work (Fig. 3a)23. Western blotting was employed to validate the purity of the extracted lipid droplets (Fig. 3b). Subsequently, fluorescence staining was performed on the FL extracted from both db/m and db/db mice (Fig. 3c), revealing larger and more numerous lipid droplets in the livers of db/db mice. Further WB analysis of the lipid droplet internal marker protein Plin2 indicated an increased quantity of lipid droplets in the lipid layer isolated from the livers of db/db mice (Fig. 3d). The fluorescence in the lipid droplets and mitochondria of the lipid layer demonstrated that, in normal mice livers, the lipid droplets were of relatively uniform size, and many of them were attached to mitochondria. In db/db mice livers, lipid droplets were of varying sizes, with many giant lipid droplets among them. Furthermore, the number of LD-Mito contacts was significantly higher in the livers of db/db mice than in the livers of db/m mice (Fig. 3c, e).

Considering that the elongated deformation of mitochondria is often accompanied by fusion and division, we tested the roles of key proteins Mfn2 and Drp1 in these processes. Mfn2, an integral component of the outer mitochondrial membrane, is instrumental in facilitating mitochondrial fusion24. Drp1 forms a ring-like structure when recruited to the outer mitochondrial membrane25, that constricts and eventually split the mitochondria in the extracted fat layer and CM. The expression of Drp1 in CM of db/db mice decreased but the expression of Mfn2 in FL increased, indicating that mitochondrial fusion played an important role in LD-Mito contact (Fig. 3e–h).

Increased LD-Mito contacts in isolated fat layer in db/db mice livers. (a) Schematic representation of the method to isolate FL, PDM, and CM from mice liver, the BioRender license is presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 6. (b) Representative western blot images for Plin2, CoxIV, and GAPDH, along with corresponding results from the Ponceau S staining, are shown. Original blots can be found in Supplementary File 2, Fig. 3. (c) Representative images of mitochondria and LDs in FL are shown (scale bars = 20 μm). LDs were marked by the neutral BODIPY 493/503 fluorescent dye (BODIPY) and mitochondria by MitoTracker deep red dye (MitoTracker). (d) Representative western blot images and levels of Plin2 in FL, original blot is presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 2a. (e) Percentage of lipid droplets in contact with mitochondria relative to the total number of lipid droplets. (f) Representative western blot maps of mitochondria protein, original blots are presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 4 (g) Protein level of Mfn2. (h) Protein level of Drp1. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 (2–3 images analyzed per sample for fluorescent images). n = 6–8 per group (western blotting). Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Morphological characteristics and status of isolated CM in normal and db/db mice livers

CM were extracted at a high centrifuge speed and stained with BODIPY and Mito-tracker. To our surprise, we found sporadic small lipid droplets in CM. We hypothesized that there might be lipid droplets in CM tightly bound to mitochondria that are so small that the fluorescence was easily quenched and difficult to observe (Fig. 4a, b). We therefore used Oil Red O and Janus Green B staining to reveal small LD-Mito contacts under bright field microscopy. As expected, a small amount of lipid droplets were drowned out in green mitochondrial signal in CM extracted from normal mice livers, while large amounts of green mitochondria were dotted with many small red lipid droplets in CM extracted from db/db mice livers (Fig. 4c, d). Under both conditions, no big lipid droplets were observed.

To further characterize the relationship between CM and lipid droplets, western blot was performed to quantify the lipid droplet marker protein Plin 2 in CM (Fig. 4e). These results confirmed that lipid droplets did exist in extracted CM and were richer in db/db mice liver. Subsequently, we assessed mitochondrial respiratory control ratio (RCR) and FAO levels in CM. We found that, compared to CM from db/m mice, CM from db/db mice, which contained a greater number of lipid droplets, exhibited not only elevated respiration levels but also enhanced FAO capacity (Fig. 4f, g). We then examined the differences in mitochondrial status and LD-Mito contact in the CM of both groups using the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit with JC-1 and reactive oxygen species (ROS) tests. Our analysis revealed significant alterations in mitochondrial function, which were associated with changes in hepatic lipid metabolism in db/db mice. These metabolic changes were characterized by an increase in the size and quantity of lipid droplets, indicating a disruption in lipid homeostasis(Fig. 4h, j). Intriguingly, these lipid droplets were loosely connected and smaller droplets tightly enveloped. Furthermore, the CM in lipid-accumulated livers demonstrated decreased activity and increased production of ROS compared to those in normal mice(Fig. 4i, k). These observations suggested a potential link between lipid accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress, potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of conditions such as MASLD. Further investigations were warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and their implications for liver disease progression and treatment strategies.

Morphological characteristics and status of isolated CM in normal liver and MASLD. (a) Representative images of mitochondria and LDs in isolated CM in db/m and db/db mice livers (scale bars = 20 μm) are shown. (b) Number of lipid droplets in CM isolated in fluorescent pictures. (c) Representative images of mitochondria and LDs in isolated CM in db/m and db/db mice livers are shown (scale bars = 20 μm). (d) Number of lipid droplets in CM isolated in the optical microscope. (e) Representative western blot images and levels of Plin2 in CM, original blot is presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 2b. (f) Signal curve of succinate-driven respiration from CM of db/m and db/db mice, measured in the presence (State 3) and absence (State 2) of ADP. RCR levels in the CM of db/m and db/db mice. (g) Signal curve of oxygen consumption from CM of db/m and db/db mice, driven by CoA/carnitine/malate in the presence of ADP. FAO levels in the CM of db/m and db/db mice. (h) Mitochondrial membrane potential is represented by the ratio of JC-1 aggregates to monomer. (j) ROS levels in CM. (i) LD-Mito contacts normalized to the total number of LDs in correlation between LD-Mito contacts and mitochondrial membrane potential and (k) ROS levels. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 (2–3 images analyzed per sample for fluorescent and bright-field images). n = 4 per group (mitochondrial RCR, FAO, membrane potential, and ROS analyses). n = 8 per group (western blotting). Student’s t-test and Pearson’s correlation coefficient were performed.* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Characteristics of two different LD-Mito contacts in isolated fat layers and CM in db/db mice livers

LD-Mito contacts existed in both fat layers and CM, which were dominated by large lipid droplets and very small droplets, respectively. Consequently, there might have been two different models of LD-Mito contacts depending on the size of lipid droplets. Fat layers and CM from db/db mice livers were subjected to fluorescence staining to study the characteristics of these two possible types of LD-Mito contacts, as LD-Mito contacts were inadequate for study in normal mice livers. In the fat layer, the average area of lipid droplets in contact with mitochondria was 15 μm2 and the average diameter was 3.5 μm, with a large range in diameters (0.3–19.7 μm). In the CM, the average area of lipid droplets in contact with mitochondria was 0.3 μm2 and the average diameter was 0.14 μm. These small lipid droplets were uniform in size, with the largest being no more than 2 μm in diameter (Fig. 5b-e). Altogether, more than 65% of the lipid droplets in the fat layer were larger than 2 μm in diameter, whereas the lipid droplets in the CM were smaller than 2 μm in diameter.

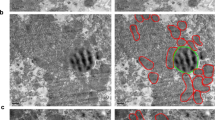

According to Talari’s work, the extracted fat layer was centrifuged at 10,400 xg to separate out the mitochondria, called PDM, and identify LD-Mito contacts19. We also extracted PDM and stained lipid droplets and mitochondria with BODIPY and Mito-tracker (Fig. 5a, b). To our surprise, we still found trace small lipid droplets in purified PDM. In contrast to the lipid droplets in CM that were surrounded by CM alone, the small lipid droplets in PDM stuck together with mitochondria and formed clumpy complexes resembling large lipid droplets surrounded by mitochondria at a density that floated in the fat layer under low centrifugation speeds (Fig. 5a, b). These small lipid droplets bound mitochondria so tightly in PDM that not even high-speed centrifugation could separate them. Interestingly, although these clumpy complexes filled with small lipid droplets and mitochondria were rare in PDM, TG analysis revealed that the total lipid droplet content was even higher in PDM than in CM (Fig. 5f). Subsequently, we assessed the respiratory function and FAO levels, Our findings indicated that, although FAO levels remained unchanged, the respiratory capacity of PDM was significantly reduced (Fig. 5g, h). We detected the key genes of fatty acid oxidation and synthesis, specifically ACC2, pACC, and CPT1A, in CM and PDM. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 (ACC2) is a key enzyme in fatty acid synthesis, catalyzing the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which provides two-carbon units for fatty acid synthesis26. Inhibition of phosphorylated ACC reduces malonyl-CoA levels, enhancing fatty acid oxidation in mitochondria and increasing cellular energy27. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 A (CPT1A) converts long-chain acyl-CoA into acylcarnitines for transport into mitochondria, a crucial step for β-oxidation28. Our results showed that CPT1A and pACC/ACC were significantly elevated in the CM, while total ACC expression was higher in PDM (Fig. 5i-m). To further investigate the oxidative status of these two types of mitochondria, we employed JC-1 and ROS assays. The results revealed that mitochondrial membrane potential levels were significantly higher in PDM compared to CM, while ROS levels were decreased in PDM (Fig. 5n, o). Therefore, we used TEM to observe the morphology of CM and PDM and found that the small lipid droplets were tightly wrapped by elongated mitochondria in CM, whereas the small lipid droplets in PDM were wrapped by multiple mitochondria surrounding by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Fig. 5p, q).

Morphological characteristics of small lipid droplets and mitochondria contacts among isolated from CM and PDM in MASLD-model mice. (a) Schematic representation of FL, PDM, and CM isolated from db/db mice livers. (b) Representative images of mitochondria and lipid droplets in FL, PDM, and CM isolated from db/db mice liver are shown (scale bars = 20 μm). (c) Size of lipid droplets in fluorescent pictures. (d) Graph showing lipid droplet diameter in FL, PDM, and CM. (e) Number of lipid droplets in fluorescent pictures. (f) TG content in CM and PDM of db/db mice. (g) Signal curve of succinate-driven respiration from CM and PDM of db/db mice, measured in the presence (State 3) and absence (State 2) of ADP. RCR levels in the CM and PDM of db/db mice. (h) Signal curve of oxygen consumption from CM and PDM of db/db mice, driven by CoA/carnitine/malate in the presence of ADP. FAO levels in the CM and PDM of db/db mice. (i) Representative western blot maps of mitochondrial protein, original blots are presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 5. (j) Protein level of ACC. (k) Protein level of pACC. (l) Expression level of pACC/ACC. (m) Protein level of CPT1A. (n) Mitochondrial membrane potential in the CM and PDM of db/db mice. (o) ROS levels in the CM and PDM of db/db mice. (p) Ultrastructure and schematic of single LD interaction with mitochondria and ER in the mode of CM. (q) Ultrastructure and schematic of multiple lipid droplets interacting with mitochondria and ER in the mode of PDM. The BioRender license is presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 7. Data are mean ± SEM. n = 3 (2–3 images analyzed per sample for fluorescent images). n = 4 per group (mitochondrial RCR, TG content, FAO, membrane potential, and ROS analyses). n = 8 per group (western blotting). Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Discussion

MASLD is characterized by lipid accumulation in the liver and a high number of significantly large lipid droplets in hepatocytes29. In the present study, we found that 18-week-old db/db mice developed severe T2DM and a pronounced manifestation of MASLD characterized by significant accumulation of big lipid droplets. Furthermore, insulin resistance induced by db/db mice worsened lipid accumulation in the liver. Impairment of insulin signaling in hepatocytes30 contributes to heightened glycolytic activity and fosters an increase in the production of acetyl coenzyme A and the upregulation of hepatic proteins associated with fatty acid synthesis (e.g., acetyl CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase)31. Although hepatic insulin signaling pathways exert an inhibitory effect on fat synthesis, cytoplasmic FFA plays a pivotal role in promoting TG synthesis, accounting for approximately 26% of the overall process32. It was observed in db/db mice that the downstream insulin pathway PI3K/Akt was inhibited, leading to gluconeogenesis and glycolysis accompanied by excessive FFA in hepatocytes. Additionally, as insulin resistance progresses throughout the body, peripheral tissues exhibit diminishing utilization of fatty acids, such as reduced TG production in adipocytes and decreased FFA energy supply in the myocardium and skeletal muscle, leading to an increase in the accumulation of FFA and LDL in the plasma of db/db mice33.

Altogether, these conditions result in a scenario where the fatty acids synthesized by the liver are less available to peripheral tissues, further exacerbating their accumulation in the liver and promoting ongoing lipid synthesis34. As predicted, we found that the lipid droplets in the hepatocytes of db/db mice were larger and more numerous, and the liver showed severe lipid deposition. A new type of mitochondria that has contact with lipid droplets has been identified in the liver, revealing a novel pattern of lipid droplet metabolism that may play an important role in lipid droplet enlargement and consumption35. Therefore, in this study, we focused on the interaction between lipid droplets and mitochondria in MASLD.

Lipid droplets store neutral lipids within cells, and their initiation, growth, and fusion processes are regulated by different organelles36. Benador et al. isolated mitochondria that adhere to lipid droplets in brown adipose tissue through differential centrifugation and categorized mitochondria into two groups: PDM, which contact lipid droplets, and CM, which do not36. In rat liver studies, fluorescence staining techniques were also utilized to visualize the interactions between lipid droplets and mitochondria, revealing that these interactions were significantly enhanced in rats subjected to a high-fat diet. Our data show an increase in lipid droplet numbers and volume in db/db mice hepatocytes. Moreover, we demonstrate that there was not only an increase in the number of LD-Mito contacts, but also that these contacts were not limited to single lipid droplets and mitochondria, instead forming multi-contact complexes.

We found that mitochondria in purified lipid droplets from the livers of db/db mice had increased levels of fusion proteins (e.g., Mfn2) and decreased levels of fission proteins (e.g., Drp1) compared with db/m mice. Talari et al. reported high expression of MFN2 in PDM compared with CM from the liver of three-month-old male Wistar rats19. Furthermore, Hu et al. demonstrated that knocking down Mfn2 levels in cardiomyocytes via adenoviral transfection led to decreased LD-mito contact levels, while overexpression of MFN2 resulted in increased LD-mito contact levels37. This may indicate that mitochondrial fusion plays an important role in LD-Mito contacts. Although there was no change in mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn2 levels in CM of db/db mice livers, this may be the reason why LD-Mito contacts are not as easily detected in CM as in PDM. However, the fission protein Drp1 was significantly decreased in CM of db/db mice. According to Benador’s research, the inhibition of fission proteins like Drp1 is a typical phenotype of LD-Mito contacts, which play a regulatory role in mitochondrial elongation18. In this work, small lipid droplets were observed in CM with diameters less than 2 μm and formed complexes with single mitochondria. We traced these small lipid droplets using electron microscopy and found that they generally share a long border with mitochondria and have high electron densities, suggesting a strong affinity between these small lipid droplets and mitochondria. These data explain why the lipid droplets and mitochondria in extracted CM were unable to be separated even by high-speed centrifugation. In high-fat diet-induced MASLD, CM demonstrated vigorous respiration and FAO due to the high levels of FFA in hepatocytes, which led to the upregulation of ROS in CM38. Respiratory chain complexes I and III in mitochondria may leak and generate superoxide ions during FAO, which in turn are converted into ROS39. In our study, we also observed these phenomena in db/db mice, where respiration, FAO, and ROS levels in CM were significantly elevated and the membrane potential was significantly decreased. Moreover, the more LD-Mito contacts in CM, the higher ROS levels and lower mitochondrial membrane potential, indicating that the CM population possesses LD-Mito contacts responsible for consuming lipid droplets by enhancing FAO.

This mechanism has not been reported in the liver, but has been reported in other kinds of cells, such as skeletal muscle and myocardium40. In these cells, lipid droplets are the main energy supply under aerobic respiration37, and share the same characteristics as those in CM of hepatocytes that combine with multiple mitochondria. LD-Mito contacts increased because of long-term stimulation of energy crisis in skeletal muscle and myocardium41. While we found that the liver promotes the formation of LD-Mito contacts in the CM population due to increased lipid accumulation, resulting in a change in function of mitochondrial FAO. However, due to the fact that the LD-Mito contacts of small lipid droplets share the same density as that of mitochondria, it is difficult to purify this type of LD-Mito contact in CM using existing methods. Therefore, further study is needed to support the hypotheses generated by the results of this study.

Notably, nearly 35% of small lipid droplets with a diameter of less than 2 μm in complex with mitochondria were also present in purified FL and settled along with the mitochondria under high-speed centrifugation during PDM extraction. The density of these complexes made them float together with FL under low-speed centrifugation and settle down with PDM under high-speed centrifugation. In contrast to the small lipid droplets in CM. Small lipid droplets in PDM were surrounded by a large amount of ER and mitochondria. Considering the ER initiates the synthesis of lipid droplets, it is possible that the ER subsequently recruited mitochondria as ATP- and substrate-donors for lipid droplet expansion. This speculation was recently verified by Najt., whose research was the first to show that the ER concatenates lipid droplets and mitochondria together, making them more conducive to the recruitment and utilization of ATP and substrates in the early stage of lipid droplet production and amplification35. Additionally, compared with CM, PDM demonstrated a higher mitochondrial membrane potential, lower respiration and ROS levels, indicating that PDM demonstrated reluctance in ATP production. Moreover, the results of lipid synthesis proteins in PDM made them more likely to promote the expansion of lipid droplets. With the amplification of lipid droplets, we observed that the ER vanished around the big lipid droplet and mitochondrial complexes, indicating that oversized lipid droplets may threaten the normal ER structure, and LD-Mito contacts play a more important role in the maintenance of lipid droplets’ further expansion.

Conclusion

The db/db mice suffered severe T2DM, leading to pronounced MASLD. Insulin resistance spontaneously aggravated the accumulation of FFA in hepatocytes, resulting in an increase in and enlargement of lipid droplets and promoting LD-Mito contacts. Not all types of LD-Mito contacts were able to be fully separated by differential centrifugation. We discovered that LD-Mito contacts between small lipid droplets and mitochondria in both purified CM and PDM exhibit different characteristics. In CM, elongated mitochondria contact single small lipid droplets, which may facilitate FAO, while in PDM, multiple mitochondria contact a couple lipid droplets, which may facilitate the expansion and maturity of lipid droplets with the help of the ER (Fig. 6).

Two different destinations of small lipid droplets and mitochondria contacts in CM and PDM of MASLD. IR insulin resistance, FFAs free fatty acids, TG triglyceride, LDs lipid droplets, PDM perdroplet mitochondria, CM cytoplasmic mitochondria, TEM transmission electron microscope, FM fluorescence microscopy, FL fat layer, RCR respiratory control ratio, FAO fatty acid oxidation, ROS reactive oxygen species, JC-1 Mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit with JC-1. Black arrows: Increase effect, vs. db/m mice; Red hollow arrows: Increase effect, vs. CM in db/m mice; Red solid arrows: Increase effect, vs. CM in db/db mice; Blue hollow arrows: Decrease effect, vs. CM in db/m mice; Blue solid arrows: Decrease effect, vs. CM in db/db mice. The BioRender license is presented in Supplementary File 2 Fig. 8.

Materials and methods

Animals

Eight-week-old db/m mice were utilized as the control group (db/m, n = 22), while BKS-db/db mice were employed as the diabetic group (db/db, n = 22) to establish a hepatic lipid deposition model. These mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility at Nanjing Sport Institute for an additional eight weeks, subjected to a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and provided ad libitum access to standard chow and water. After fasting for eight hours, all mice were anesthetized with 10% pentobarbital sodium (Sigma, USA) at a dose of 0.1 mL/10 g. Blood samples were collected by excising the ocular vessels. One part of the mice underwent immediate cardiac perfusion fixation for morphological analysis; livers from another part of the mice were harvested for Western blot analysis, biochemical assays, and the isolation of FL, CM, and PDM; the rest were perfused with Collagenase IV via the portal vein to isolate primary hepatocytes. Ultimately, all mice were sacrificed by cardiac excision. All the methods in this experiment were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Nanjing Sport Institute, and all experiments were performed in accordance with the Animal Ethics and Welfare Committee of Nanjing Sport Institute (Approval No. 2019–010). In addition, all experiments in our study were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Serum biochemical tests

Blood samples were centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 3500 × g, then the supernatant was collected. All serum biochemical tests were conducted using an automated biochemical analyzer (F-7100, Hitachi), with specific methods employed for each lipid measurement. Total cholesterol (TC) was assessed utilizing the CHOP-PAP method, while triglycerides (TG) were measured using the GPO-PAP method. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were determined through the surfactant clearance method. Furthermore, FFA was detected using the ACS-ACOD method. Following blood collection, the liver was excised, rinsed with cold saline, and stored at -80 °C for experimental analysis.

Hematoxylin-eosin and oil red o staining of liver tissue

The mice’s hearts were perfused with saline to flush out the blood. To preserve tissue integrity, a liver lobe was rapidly sectioned into small pieces and immediately submerged in liquid nitrogen-precooled glutaraldehyde for cryopreservation. The remaining liver tissue was continuously perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde to prepare samples for electron microscopy. The frozen liver tissue was sectioned into thin slices for cryosectioning, and 10 μm sections were obtained using a cryostat. For H&E staining, the tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with hematoxylin (BL702A, Biosharp) and eosin, dehydrated using 95% ethanol, anhydrous ethanol, and xylene, and finally sealed with glycerol gelatin. For Oil Red O staining, the tissue was fixed with anhydrous ethanol, stained with hematoxylin, rinsed with 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol, and stained with Oil Red O solution (#SHBL1039, Sigma) for 3 min. Images were captured using a microscope (Zeiss, Axio Imager A2) at a magnification of 200x. For each sample, five visual fields were randomly selected. The Oil Red O-stained area was quantified using ImageJ software. The data is represented by the Oil Red O-stained area as a proportion of the total area.

Electron microscopy

The fixed liver samples were perfused with paraformaldehyde, sectioned into 1 × 1 × 1 mm³ tissue blocks, and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer. Subsequently, they were fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h and processed using standard techniques. Ultrathin Sect. (70 nm) were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, then observed and imaged using a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400, Japan). For each sample, five visual fields were randomly selected. Data acquisition was conducted using ImageJ software. The LD-mitochondria contacts were defined as the physical interaction between the surface edge of the lipid droplet and the outer membrane of the mitochondrion. The number of mitochondria in contact with lipid droplets and the length of LD-mitochondria contacts were quantified using ImageJ software, alongside the total number of mitochondria and the total perimeter of both mitochondria and lipid droplets in each electron micrograph. The characteristics and quantity of LD-mitochondria contacts are presented as the ratio of the number of mitochondria in contact with lipid droplets to the total number of mitochondria, as well as the LD-mitochondria contact length relative to the total perimeter of either the mitochondria or lipid droplets.

Isolation and staining of primary hepatocytes

Primary hepatocytes were isolated by a modified method of Meital et al.22. The liver samples were initially perfused through the portal vein, using 25 mL of pre-perfusion solution (0.5 mM EGTA, 25 mM HEPES, D-HANKS), followed by 25 mL of a digestive solution (Collagenase IV, 3 mM CaCl2, 15 mM HEPES, DMEM). After perfusion, the liver was removed and transferred to a culture dish containing 10 mL of dispersion medium (15 mM HEPES, DMEM). The liver capsule was carefully opened using forceps, and the primary hepatocytes were gently dislodged. For fluorescence microscopy, primary hepatocytes were stained with BODIPY 493/503 (#D3922, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and MitoTracker Red CMXRos (C1035, Beyotime Biotechnology) at a ratio of sample volume: BODIPY 493/503: MitoTracker Red CMXRos = 1:1000:1000 (v/v/v). Observations and images were captured using Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (UltraVIEW VoX, PerkinElmer). For each sample, five primary hepatocytes were randomly selected. The area of the lipid droplets and the area of the primary hepatocytes were quantified using ImageJ software. The data are presented as the ratio of the total lipid droplet area to the overall cellular area.

Isolation and staining of FL, CM, and PDM

All solutions and equipment were pre-chilled. The livers from mice were weighed, chopped, and suspended in Buffer A (250 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, 2% (w/v) BSA). The samples were then homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer and transferred to a 50 mL Falcon tube. The mixture was centrifuged at 900 x g for 10 min. Following centrifugation, the upper white floating layer, designated as the fat layer (FL), was collected. The FL was then centrifuged at 10,400 x g to isolate a precipitate known as peridroplet mitochondria (PDM). Additionally, the middle liquid layer was subjected to centrifugation at the same speed to obtain a precipitate termed cytoplasmic mitochondria (CM), along with the upper liquid layer, which corresponds to the cytosol. FL, CM, and PDM were resuspended in Buffer B (250 mM sucrose, 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA) for staining, analysis of mitochondrial function, and protein expression analysis.

For brightfield microscopy, CM were stained with Janus Green B dye (GMS60007, GENMED) and Oil Red O solution (#SHBL1039, SIGMA) at a ratio of sample volume: Janus Green B: Oil Red O solution = 1:1:1 (v/v/v). For fluorescence microscopy, FL, CM, and PDM were stained with BODIPY 493/503 (#D3922, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and MitoTracker Red CMXRos (C1035, Beyotime Biotechnology) at a ratio of sample volume: BODIPY 493/503: MitoTracker Red CMXRos = 1:2000:2000 (v/v/v). The evaluation of lipid droplets (LDs) in the FL extracted from mouse liver in contact with mitochondria was carried out through a systematic analysis. For each sample, five visual fields were randomly selected. The area and number of lipid droplets with a diameter ≥ 2 μm and the number of lipid droplets with a diameter < 2 μm were quantified using ImageJ software. Then, the LD-mitochondria contact (LD-Mito contact) was calculated as the percentage of lipid droplets surrounded by mitochondria relative to the total number of lipid droplets. This percentage provides a quantitative measure of the interaction between lipid droplets and mitochondria in the liver samples. The size of lipid droplets in the samples is represented by the proportion of the number of lipid droplets with a diameter ≥ 2 μm and the number of lipid droplets with a diameter < 2 μm.

Liver TG and FFA content assay

The liver samples were prepared and ground on ice. The tissue homogenate was treated with a TG Content Assay kit ( Boxbio, AKFA003M ), and the absorbance at 420 nm was measured using an enzyme meter to take readings and finally, the data were analyzed. The liver tissue homogenate was treated with an FFA content detection kit ( solarbio, BC0595 ), and the absorbance at 550 nm was measured using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN, Spark) to take readings finally, the data were analyzed.

Mitochondria TG content assay

The protein content of CM and PDM samples was quantified using the BCA protein assay method. Triglyceride levels in these samples were assessed using the Triglyceride Assay Kit (Ab65336, Abcam) designed for the detection of triglycerides in mitochondria. Initially, 47.6 µL of Triglyceride Assay Buffer was added to the assay wells, followed by the addition of 0.4 µL of Triglyceride Probe and 2 µL of Triglyceride Enzyme Mix. Subsequently, 50 µL of standards, along with CM and PDM samples and a blank control group, were included in the assay. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, readings were taken using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN, Spark) set to excitation/emission wavelengths of 535/587 nm, and the data were analyzed accordingly. Results were expressed as nmol/mg protein.

Mitochondria respiratory function and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) assay

Mitochondrial respiration was determined using the MitoXpress Xtra Oxygen Consumption Assay (MX-200-4, Agilent). The protein content of the CM and PDM fractions was measured using BCA reagent, and 3.125 µg of protein was added to each well in a 384-well plate. Each well was also supplied with 37.5µL of the appropriate mitochondrial assay buffer, containing 250 mM sucrose, 15 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, and 30 mM K2HPO4, at pH 7.4. State II respiration was tested by supplying substrates such as 12.5 mM glutamate/malate and 25 mM succinate. State III respiration was tested by supplying 1.65 mM ADP to the isolated mitochondria in the presence of substrates. The fluorescence was measured at oxygen absorption spectra. The level of RCR was expressed as the ratio of the rate of change in fluorescence intensity per unit time between State III and State II, represented as StateIII/StateII. FAO capabilities were tested by supplying substrates such as 0.4 mM palmitoyl-CoA, 20 mM carnitine, 50 mM malate, and 3.64 mM ADP. The fluorescence was again measured at oxygen absorption spectra. The level of FAO was expressed as the rate of change in fluorescence intensity per unit time.

Mitochondria membrane potential and ROS assay

CM and PDM samples were normalized and diluted to a concentration of 1.25 µg/µl protein using the BCA protein quantification method. The mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated using the Enhanced Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit with JC-1 (C2003S, Beyotime Biotechnology). Mitochondrial samples were stained with 2 µM JC-1 at 37 °C in the dark for 20 min. At high mitochondrial membrane potential, the JC-1 dye aggregates in the mitochondrial matrix, forming J-aggregates that emit red fluorescence. Measurements were taken using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN, Spark) set to excitation/emission wavelengths of 585/590 nm. Conversely, at low mitochondrial membrane potential, JC-1 remains in its monomeric form, producing green fluorescence, with readings taken at excitation/emission wavelengths of 514/529 nm. Data are expressed as the ratio of JC-1 aggregates to monomers. For the detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in CM and PDM samples, the Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, S0033S) was utilized. Mitochondrial samples were stained with 10 µM DCFH-DA at 37 °C in the dark for 20 min. DCFH-DA is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to produce DCFH, which can be oxidized by intracellular ROS to generate the fluorescent compound DCF. Readings were obtained at excitation/emission wavelengths of 488/525 nm using a Spark multimode microplate reader (TECAN, Spark), and the data were subsequently analyzed.

Immunoblotting

Total protein was extracted from liver tissue samples, and the concentration of total protein, as well as extracted FL, CM, cytosol, and PDM proteins in liver tissue, was determined using the BCA method and adjusted to the same concentration. The samples were separated using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (ISEQ00010, MERCK). Following the transfer, the membrane was stained with Ponceau S (P0022, Biotechnology), photographed, and subsequently washed with distilled water. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h, and primary antibodies diluted in 5% milk were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was then washed three times with TBST and incubated with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Details of primary and secondary antibodies used in this study are as follows: Insulin Receptor β (4B8) Rabbit mAb(1:1000, 3025 S, Cell Signaling); PI3 Kinase p85 Alpha Monoclonal antibody(1:20000, 60225-1-Ig, Proteintech); Phospho-PI3K p85 alpha (Tyr607) Antibody(1:1000, #AF3241, Affinity); Akt (pan) (11E7) Rabbit mAb (1:1000, 4685 S, Cell Signaling); Phospho-Akt (Ser473) (D9E) XP® Rabbit mAb (1:1000, 4060 S, Cell Signaling); GAPDH Polyclonal antibody(1:20000, 10494-1-AP, Proteintech); VDAC1/2 Polyclonal antibody(1:2000, 10866-1-AP, Proteintech); ATGL Antibody(1:2000, 2138 S, Cell Signaling); ADRP/Perilipin-2 Polyclonal antibody(1:10000, 15294-1-AP, Proteintech); Anti-Mitofusin 2 antibody [NIAR164] (1:5000, ab124773, Abcam); DRP1 Antibody (C-5) (1:1000, sc-271583, SANTA); COX4I1 Monoclonal Antibody(1:2000, E-AB-22002, Cell Signaling); CPT1A Polyclonal antibody(1:1000, 15184-1-AP, Proteintech); Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (C83B10) Rabbit mAb(1:1000, 3676 S, Cell Signaling); Phospho-Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (Ser79) (D7D11) Rabbit mAb(1:1000, 11818 S, Cell Signaling); Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody(1:2000, 7076P2, Cell Signaling); Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked Antibody(1:2000, 7074P2, Cell Signaling). Protein bands were visualized using an ECL system and an automatic chemiluminescence image analysis system system (5200Multi, Tanon). The resulting images were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Statistical analyses

ImageJ was utilized for image analysis, and GraphPad Prism 8 software was employed for data analysis. Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance ( ANOVA ) were used for comparison between groups, and then Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to test the correlation coefficient. Results are presented as mean ± standard error, with P < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author J.L. or Y.Z.

References

Badmus, O. O., Hillhouse, S. A., Anderson, C. D., Hinds, T. D. & Stec, D. E. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (mafld): functional analysis of lipid metabolism pathways. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 136, 1347–1366 (2022).

Alves-Bezerra, M. & Cohen, D. E. Triglyceride metabolism in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 8, 1–8 (2017).

Meng, D. et al. Biological role and related natural products of sirt1 in nonalcoholic fatty liver. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 16, 4043–4064 (2023).

Fujii, H., Kawada, N. & Japan, S. G. O. N. The role of insulin resistance and diabetes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, (2020).

Tanase, D. M. et al. The intricate relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2Dm), insulin resistance (Ir), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Nafld). J. Diabetes Res. 1–16 (2020). (2020).

Khan, R. S., Bril, F., Cusi, K. & Newsome, P. N. Modulation of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 70, 711–724 (2019).

Zheng, Y., Wang, S., Wu, J. & Wang, Y. Mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: new insights from pathogenic mechanisms to clinically targeted therapy. J. Transl Med. 21, 510 (2023).

Schrader, M., Godinho, L. F., Costello, J. L. & Islinger, M. The different facets of organelle interplay-an overview of organelle interactions. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 3, 56 (2015).

Benador, I. Y., Veliova, M., Liesa, M. & Shirihai, O. S. Mitochondria bound to lipid droplets: where mitochondrial dynamics regulate lipid storage and utilization. Cell. Metab. 29, 827–835 (2019).

Yu, J. et al. Lipid droplet remodeling and interaction with mitochondria in mouse brown adipose tissue during cold treatment. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (Bba) - Mol. Cell. Res. 1853, 918–928 (2015).

Cui, L. & Liu, P. Two types of contact between lipid droplets and mitochondria. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8, 618322 (2020).

Yang, M. et al. Lipid droplet - mitochondria coupling: a novel lipid metabolism regulatory hub in diabetic nephropathy. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1017387 (2022).

Enkler, L. & Spang, A. Functional interplay of lipid droplets and mitochondria. Febs Lett. 598, 1235–1251 (2024).

Annesley, S. J. & Fisher, P. R. Mitochondria in health and disease. Cells 8, (2019).

Varghese, M. et al. Adipocyte lipolysis affects perilipin 5 and cristae organization at the cardiac lipid droplet-mitochondrial interface. Sci. Rep. 9, 4734 (2019).

Brownstein, A. J. et al. Mitochondria isolated from lipid droplets of white adipose tissue reveal functional differences based on lipid droplet size. Life Sci. Alliance 7, (2024).

Bórquez, J. C. et al. Mitofusin-2 induced by exercise modifies lipid droplet-mitochondria communication, promoting fatty acid oxidation in male mice with Nafld. Metabolism 152, 155765 (2024).

Benador, I. Y. et al. Mitochondria bound to lipid droplets have unique bioenergetics, composition, and dynamics that support lipid droplet expansion. Cell. Metab. 27, 869–885 (2018).

Talari, N. K. et al. Lipid-droplet associated mitochondria promote fatty-acid oxidation through a distinct bioenergetic pattern in male wistar rats. Nat. Commun. 14, 766 (2023).

Park, J., Seo, E. & Jun, H. S. Bavachin alleviates diabetic nephropathy in db/db mice by inhibition of oxidative stress and improvement of mitochondria function. Biomed. Pharmacother. 161, 114479 (2023).

Xu, Q., Zhang, X., Li, T. & Shao, S. Exenatide regulates Th17/Treg balance via Pi3K/Akt/Foxo1 pathway in Db/Db mice. Mol. Med. 28, 144 (2022).

Charni-Natan, M. & Goldstein, I. Protocol for primary mouse hepatocyte isolation. Star. Protoc. 1, 100086 (2020).

Ngo, J. et al. Isolation and functional analysis of peridroplet mitochondria from murine brown adipose tissue. Star. Protoc. 2, 100243 (2021).

Hu, L. et al. Targeting mitochondrial dynamics by regulating mfn2 for therapeutic intervention in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Theranostics 9, 3687–3706 (2019).

Ma, X. et al. Loss of hepatic Drp1 exacerbates alcoholic hepatitis by inducing megamitochondria and mitochondrial maladaptation. Hepatology 77, 159–175 (2023).

Cao, H. et al. Malonylation of Acetyl-Coa carboxylase 1 promotes hepatic steatosis and is attenuated by ketogenic diet in Nafld. Cell. Rep. 42, 112319 (2023).

Paul, B., Lewinska, M. & Andersen, J. B. Lipid alterations in chronic liver disease and liver cancer. Jhep Rep. 4, 100479 (2022).

Schlaepfer, I. R. & Joshi, M. Cpt1a-mediated fat oxidation, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Endocrinology 161, (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Updated mechanisms of masld pathogenesis. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 117 (2024).

Kim, D. H. et al. Foxo6 integrates insulin signaling with gluconeogenesis in the liver. Diabetes 60, 2763–2774 (2011).

Linden, M. A. et al. Combining metformin therapy with caloric restriction for the management of type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 40, 1038–1047 (2015).

Softic, S., Cohen, D. E. & Kahn, C. R. Role of dietary fructose and hepatic de novo lipogenesis in fatty liver disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 61, 1282–1293 (2016).

Yazici, D. & Sezer, H. Insulin resistance, obesity and lipotoxicity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 960, 277–304 (2017).

Santoleri, D. & Titchenell, P. M. Resolving the paradox of hepatic insulin resistance. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 447–456 (2019).

Najt, C. P. et al. Organelle interactions compartmentalize hepatic fatty acid trafficking and metabolism. Cell. Rep. 42, 112435 (2023).

Olzmann, J. A. & Carvalho, P. Dynamics and functions of lipid droplets. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 137–155 (2019).

Hu, L. et al. Mfn2/Hsc70 complex mediates the formation of mitochondria-lipid droplets membrane contact and regulates myocardial lipid metabolism. Adv. Sci. 11, e2307749 (2024).

Chen, Z., Tian, R., She, Z., Cai, J. & Li, H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Biol. Med. 152, 116–141 (2020).

Zeng, S. et al. Inhibition of fatty acid translocase (Fat/Cd36) palmitoylation enhances hepatic fatty acid beta-oxidation by increasing its localization to mitochondria and interaction with long-chain acyl-coa synthetase 1. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 36, 1081–1100 (2022).

de Almeida, M. E. et al. Acute exercise increases the contact between lipid droplets and mitochondria independently of obesity and type 2 diabetes. J. Physiol. 601, 1797–1815 (2023).

Ouyang, Q. et al. Rab8a as a mitochondrial receptor for lipid droplets in skeletal muscle. Dev. Cell. 58, 289–305 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities of Jiangsu Province (2020240487), Youth Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (32000839), Graduate Research and Innovation Projects of Jiangsu Province (KYCX23_2363, KYCX23_2380 and KYCX24_2420), Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province of China ([2021]11), and The Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduates of Jiangsu Province of China (202310330009). The authors would like to thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. Figure 3(a), 5(p), 5(q), and 6 were created with BioRender.com. Furthermore, publication licenses for each figure have been obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., Y.Z., and T.Q .conceived and designed this experiment. Y.X., Y.Z., W.S., W.F., H.X., X.Y., M.X., Y.G., J.W., H.Z., and J.L. conducted experiments and data collection. Y.X., Y.Z., W.S., J.W., Q.T., W.F., and J.L. analyzed and interpreted the data. Y.X., Y.Z., and J.L wrote manuscripts. All authors read and have given critical comments and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Zhang, Y., Sun, W. et al. Characteristics of different lipid droplet-mitochondrial contacts patterns during lipid droplet metabolism in T2DM-induced MASLD. Sci Rep 15, 3399 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87871-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87871-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Interactions between lipid droplets and mitochondria in metabolic diseases

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Morphological alterations of peridroplet mitochondria in human liver biopsy

Scientific Reports (2025)