Abstract

Internet of Things (IoT) is one of the most important emerging technologies that supports Metaverse integrating process, by enabling smooth data transfer among physical and virtual domains. Integrating sensor devices, wearables, and smart gadgets into Metaverse environment enables IoT to deepen interactions and enhance immersion, both crucial for a completely integrated, data-driven Metaverse. Nevertheless, because IoT devices are often built with minimal hardware and are connected to the Internet, they are highly susceptible to different types of cyberattacks, presenting a significant security problem for maintaining a secure infrastructure. Conventional security techniques have difficulty countering these evolving threats, highlighting the need for adaptive solutions powered by artificial intelligence (AI). This work seeks to improve trust and security in IoT edge devices integrated in to the Metaverse. This study revolves around hybrid framework that combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) and machine learning (ML) classifying models, like categorical boosting (CatBoost) and light gradient-boosting machine (LightGBM), further optimized through metaheuristics optimizers for leveraged performance. A two-leveled architecture was designed to manage intricate data, enabling the detection and classification of attacks within IoT networks. A thorough analysis utilizing a real-world IoT network attacks dataset validates the proposed architecture’s efficacy in identification of the specific variants of malevolent assaults, that is a classic multi-class classification challenge. Three experiments were executed utilizing data open to public, where the top models attained a supreme accuracy of 99.83% for multi-class classification. Additionally, explainable AI methods offered valuable supplementary insights into the model’s decision-making process, supporting future data collection efforts and enhancing security of these systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) integrates together physical objects into the digital world, transforming how the users engage with both realities within the emerging and evolving landscape of the Metaverse1. IoT networks drive the development of novel virtual ecosystems across sectors like smart cities, healthcare and entertainment. Thanks to IoT, data is autonomously collected, processed, and shared without interruption2. The Metaverse enhances this connection by supporting immersive experiences, personalized interactions, and real-time decision-making3. Being a crucial part of the Metaverse, IoT leverages traditional networks into highly interconnected environments, promoting innovation and redefining user experiences by blending together real-world interactions with virtual opportunities. Thus, one of the requirements is to provide reliable operation of these networks, along with high level of availability4.

Personal IoT networks, consisting of wearables, smart home systems, and AR/VR gadgets, provide users with unprecedented levels of convenience and control over their Metaverse experiences. These devices allow establishment of a tangible connection between an individual’s virtual environment or avatar and their physical surroundings, supporting more inherent and advanced management of virtual spaces. The swift expansion of IoT is propelling the evolution of the Metaverse, breaking the limits of connectivity and merging the physical and digital worlds into a smooth and immersive experience5,6.

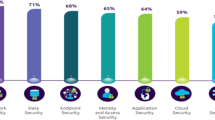

However, this rapid expansion of IoT within the Metaverse faces significant challenges including protecting interconnected devices that handle sensitive user data, and mitigating real-time cyber threats that could disrupt immersive experiences7. Primarily, IoT devices in general are highly vulnerable to cyberattacks because of their limited processing capabilities and reliance on basic systems8,9. This vulnerability is even more critical within the Metaverse, where essential virtual and physical infrastructures are managed by interconnected systems. Potential malicious users may exploit these weaknesses and disrupt online healthcare services, cause financial losses in Metaverse commerce, or gain unauthorized access to personal data streams, smudging the thin line between virtual and real-world consequences. Therefore, innovative security frameworks are essential for ensuring a secure and immersive Metaverse experience for all users. These solutions must hit the balance between the lightweight architecture of IoT gadgets and robust security measures, like advanced encryption methods and real-time updates10,11,12.

The principal constraints of traditional security solutions may be summed up as the difficulty to keep up to date with dynamic and swiftly changing Metaverse environment. They are not adaptable enough to cancel out novel emerging threats like botnets attacks13, attempting to exploit the vulnerabilities of the complex correlations among the real and digital worlds within the Metaverse, as they are mostly designed to be reactive. On the other hand, cybersecurity solutions combined with artificial intelligence (AI) provide considerably more adaptable and data-driven defensive options14,15. AI-fueled solutions are capable of analyzing immense datasets in real-time, allowing identification of trends and drifts in risk to prevent damage before it happens. This is vital for maintaining the robustness of the expanding Metaverse, providing users safe and continuous experience while they are exploring and producing new virtual contents.

Despite numerous advantages, AI faces some weaknesses as well. Primarily, inadequate quality of data, ill-judged algorithms and incompetently chosen hyperparameter configurations. Consequently, models trained by inadequate quality datasets may result in unreliable outcomes, highlighting the necessity of high quality data for proper training. Alternatively, selection of the appropriate machine learning (ML) models is crucial, as various methods have tendency to perform unalike regarding of the challenge being solved and utilized dataset. Hyperparameters’ configuration, like number of layers, learning rate or dropout can additionally heavily impact the model’s performance, and must be carefully optimized to achieve optimal outcomes. Wolpert’s no free lunch (NFL) assumption16 discloses non-existance of all-round solution that works well for all classification challenges. As a result, models have to be selected and adapted to each specific task. Nevertheless, optimizing hyperparameters is broadly recognized as an NP-hard optimization challenge due to its inherent complexity. A key challenge for AI scientists is determining the appropriate hyperparameter configuration in such situations, as it is computationally infeasible. Conventional optimization algorithms regularly fall short in these scenarios, as they struggle to deliver the desired outcomes within a tolerable time frame. One potential answer is to utilize metaheuristics algorithms, capable to scan immense solution spaces to deliver approximate solutions. These methods are well-suited for addressing complex real-world challenges where finding exact answers is impractical.

This paper proposes a framework consisting of two levels, galvanized by the architecture explored in the previous research17. Convolutional neural network (CNN) is utilized in the primary layer of the architecture, and assigned the role to extract the features. As outlined by other relevant previous publications18,19,20, significant improvements in the performance of CNN can be introduced with replacement of the ultimate dense CNN’s layer by other classifiers like AdaBoost or XGBoost. Consequently, this study takes similar approach, by feeding the intercepted output of the final CNN’s data processing layer to the inputs of the second level of framework, where CatBoost and LightGBM classifiers are used for further improvement of the classification capability of the architecture, especially for high volume massive streams of data generated by Metaverse IoT networks, necessitating real time processing. Moreover, configuration of both levels of framework is optimized by metaheuristics algorithms, assigned to tune the hyperparameters of regarded models. This approach ensures achieving the finest possible outcomes of the proposed combined framework. Generally speaking, the proposed methodology maximizes the benefits provided by both deep learning and ensemble approaches, where metaheuristics algorithms warrant the proper configuration of models’ hyperparameters for achieving superior performance.

An altered version of chimp optimization algorithm (ChOA)21 was used in this research to tune the hyperparameters of both layers of the framework to ensure good performance. ChOA metaheuristics was selected after careful experimentation with different optimizers, since NFL16 elaborates that a ubiquitous optimizer that could deliver the best performance for all optimization problems does not exist. Despite the existence of other powerful optimizers like crayfish optimization algorithm (COA)22, red fox optimizer (RFO)23 and reptile search algorithm (RSA)24, elementary version of ChOA rallied astounding results over the smaller scale simulations, and it was consequently selected for auxiliary modifications that would allow reaching even more desirable outcomes for intrusion classification problem.

With respect to all presented facts, primary contributions of this research may be delineated along the following lines:

-

A proposition of the novel two-level AI framework for enhancing Metaverse IoT network security.

-

Framework comprised of combination of CNN and boosting ensemble classifiers to perform threat classification in IoT networks.

-

A proposition of a modified optimization metaheuristics tailored for the problem in hand, building upon the baseline ChOA, that was employed to tune the framework’s models.

-

The top-performance models were subjected to Explainable AI to establish the relative importance of the features and their effect on forecasts made by the system.

This study is arranged in the following units. Section "Related works" puts forth the related works on this matter along with the utilized techniques’ foundations. Next section "Methods" delineates the baseline ChOA metaheuristics, and showcases the altered version of algorithm that was later employed in the experiments. The settings of the experimental environment required for reproducibility of the simulations are set forth in Section "Experimental setup", while simulation outcomes of all simulations that were carried out are delineated and discussed in Section "Results". Ultimately, Section "Conclusion and future work" delivers the concluding remarks and suggests possible ways forward in the future research.

Related works

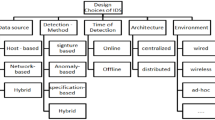

Conventional systems used for network protection, that revolve around firewall and blacklist solutions, have very constrained capabilities. They are not flexible enough, depending of the collection of rules and human interventions to adjust to the novel attacks. Moreover, they can only be upgraded with novel attacking patterns after the system was already breached. In other words, they are capable of responding to the events that have already happened in the past. This drawback makes conventional systems ineffective when encountering zero-day attack and emerging menaces, leaving the networks vulnerable and open to sophisticated cyber-threats. Many approaches were used from early 2000s25, typically divided into intrusion detection systems (IDS) and intrusion prevention systems (IPS). Nowadays, a wide spectrum of tools is openly available for security of the systems, including firewall and antivirus applications, however, their restricted functionality leaves them open to novel types of threats.

One way to handle these novel types of threats that emerge each day revolves around integration of AI and IoT security applications. Generally speaking, AI couples seamlessly with IoT networks for different purposes as evidenced by numerous practical implementations26,27. The role of AI in this scenario is to enhance the security of IoT networks through identification of anomalous behavior in real time, where ML models are utilized to detect and classify possible threats from normal traffic. Hybrid ML solutions tailored specifically for IoT security challenge have been introduced by papers such as28, highlighting their superiority in threat detection across various IoT devices and architectures. More focused research, such as29, explored intrusion detection specifically within healthcare-related IoT networks, employing ML classifiers adjusted by hybrid metaheuristics techniques. While these studies showcased the significant potential of ML models, they also emphasized the challenges associated with selecting the appropriate hyperparameters, which is crucial to achieve optimal performance.

Optimizing the hyperparameters of ML models is essential for achieving optimal results and maximizing effectiveness, not only within cybersecurity but across various other fields. Poor tuning often leads to model failure and underperformance. A significant portion of recent research focuses on hyperparameters tuning for various ML structures utilizing metaheuristics algorithms30,31. This applies to the IoT intrusion detection problems as well, where hybrid approaches where ML models were tuned by metaheuristics delivered promising outcomes32,33.

Despite recent progress in this field, a significant research gap remains. While metaheuristics-tuned ML models have been explored to some extent for IoT networks and intrusion detection, the focus has primarily been on models like XGBoost and AdaBoost, with limited investigation into LightGBM tuning. Additionally, the two-level framework suggested within this research, which combines a CNN with CatBoost and LightGBM classifiers and uses metaheuristics techniques to tune both levels, has not been previously studied for the observed challenge. Furthermore, the dataset34 employed within the experiments, published in 2023, has yet to be thoroughly explored.

The remainder of this section yields brief background of the techniques utilized in this research, by providing basics of CNNs, CatBoost and LightGBM classifying models, followed by a short overview of metaheuristics approaches along with their prosperous applications.

Convolutional neural networks

Convolutional neural networks35 are famous of their image classification and object detection capabilities, but they also excel in other tasks. Inspirited by the mammal visual cortex structure, they follow similar layered architecture. Input data passes through all layers in a particular order, making use of transfer activation functions like ReLu, tanh and sigmoid for mapping of the non-linear output.

To construct a deep CNN, it is essential to include a convolutional layer along with nonlinear, pooling, and fully connected layers36. For the provided input data, multiple filters skid over the convolutional layer, producing an output as the sum of element-wise multiplication of each filter and the receptive field of the input data. This weighted sum is then placed as an element in the subsequent layer. Nonlinear layers primarily function to alter or constrain the output which is produced. Various nonlinear functions are available for use in CNNs, but ReLU remains one of the most widely employed options37. The pooling layer effectively shrinks the dimensionality of the input data. The most commonly used method, max pooling, selects the highest value within each pooling filter. Max pooling is highly regarded in the relevant literature for its efficacy, as it downsamples the input by approximately 75%, delivering significant outcomes. Fully connected layers execute the classification task.

Convolution operation, expressed by Eq. (1), manages processing of the inputs:

here, \(z^{[l]}_{i, j, k}\) corresponds to the output feature outcomes produced by k-th feature map on position i, j within l-th layer. The input located on i, j is marked as x, w denotes the filter set, while b describes the bias scores.

Following the convolution operation, activation is executed according to the Eq. (2):

here, \(g(\cdot )\) describes non-linear operation administered to the outputs.

The outputs resolution is reduced by the pooling layers, that apply either average or max pooling in the majority of the practical applications. This procedure is expressed by Eq. (3).

here, y represents the pooling layer’s result.

Ultimately, dense layers perform the classifying task. For multi-labeled data, softmax layer executes classifying task, while for binary classification problems, the logistic (sigmoidal) layer is employed. As the epochs pass by, the network updates the weights and bias scores reducing the cross-entropy loss function in a gradient-descent manner38. This is mathematically expressed by Eq. (4).

where p and q each denote distribution defined over discrete parameter x.

Optimizing CNN’s hyperparameters is essential, as they greatly influence the network’s accuracy. Key hyperparameters encompass the count and size of kernels within every convolutional layer, learning rate, batch size, the count of convolutional and fully connected (dense) coats, weight regularization within dense coat, activation functions, dropout rate, and others. Since there is no universal solution for hyperparameter tuning procedure, a “trial and error” approach is often necessary.

CNNs are widely adopted in computer vision35, with recent advancements across areas such as facial recognition39, document analysis40, medical images classifying task and diagnostic support in general41. Additionally, CNNs also play an essential role in climate change analysis and extreme weather prediction42, among numerous other applications43,44.

CatBoost classification model

Handling categorical datasets poses a considerable challenge within machine learning. Often, substantial preprocessing or conversion is required prior to effectively use data in models. Categorical features are characterized by a set of distinct values known as categories that cannot be compared. One common approach for working with categorical features in boosted tree models is one-hot encoding45, where each category is represented by a novel binary feature. However, for features with large cardinality, this approach can synthesize an impractically large count of new features. A solution to this issue is to group categories into a limited count of clusters prior to applying one-hot encoding. One popular method for this is employing target statistics (TS)45, where each category is represented by its projected target value. Yandex scientists devised the CatBoost algorithm46 specifically to enhance the handling of categorical data compared to traditional approaches.

CatBoost adopts a more advantageous outlook inspirited by online learning frameworks, which process training samples sequentially over time, relying on a concept of ordering. In this method, TS for each instance are computed based solely on prior observations. To adapt this concept for traditional offline environments, CatBoost introduces a pseudo-time by creating a random permutation of the training samples. This allows the TS for each instance to be calculated with respect to all available historical data up to that point. Additionally, CatBoost employs a technique called ordered boosting, which prevents prediction shift, further leveraging the model’s reliability46. Catboost produces \(s + 1\) discrete random permutations of the training dataset at the beginning. Here, \(\sigma _0\) is utilized to select the leaf scores \(b_j\) of the generated trees \(h(x) = \sum _{j=1}^{J}b_j\mathbb {I}_{\{x\in R_j\}}\), and the permutations \(\sigma _1,...,\sigma _s\) are used to establish tree structure (like internal nodes). Let the model training is performed employing I trees. There have to exist \(F^{I-1}\) of them exercised without the sample \(x_k\) if there exist unshifted residual \(r^{I-1}(x_k,y_k)\). Instances cannot be used in training \(F^{I-1}\) since unbiased residuals are necessary for all training samples. Nevertheless, it is possible to maintain a set of models that differ with respect to the samples included in their training process. To compute the residual for a particular example, a model trained without that example is utilized. This set of models can be constructed through application of the same ordering principle utilized for TS. The algorithm for this approach is showcased as follows:

Within CatBoost, base estimators behave like oblivious decision trees, meaning that the same splitting criteria are applied across all tree levels. This structure considerably enhances execution speed for testing, creates balanced trees, reduces susceptibility to overfitting issue, and enables significant performance acceleration. The scores within the leaves in the ultimate model are established through the standard gradient boosting procedure, applied consistently across both modes, incorporating all constructed trees. Each training sample is mapped to specific leaves, such as \(leaf_0(i)\), with the permutation \(\sigma _0\) utilized to calculate TS within this context. In testing phase, when the final model is applied to a novel example, TS values are calculated utilizing the entire training dataset.

As the count of categorical features within a dataset grows, the possible combinations increase exponentially, making it impractical to process them all. To address this, CatBoost uses a greedy approach to produce feature combinations. For each split in a tree, CatBoost combines all categorical features and their combinations previously employed in earlier splits of the current tree with all categorical features in the dataset.

LightGBM classification model

LightGBM (light gradient boosting machine)47 was introduced by Microsoft and made open-source. It is a gradient boosting framework designated for high performance and efficiency when dealing with immense datasets. It manages to achieve excellent performance thanks to a novel method labeled gradient-based one-side sampling (GOSS), that decreases the count of data samples while keeping the accuracy. Moreover, LightGBM also employs exclusive feature bundling (EFB) for combining the mutually exclusive attributes, effectively decreasing the data dimensionality and leveraging the computing efficacy. This pair of innovative procedures helps LightGBM to perform training faster in comparison to conventional boosting models, and efficiently handle immense datasets comprising of thousands and millions of samples and features.

LightGBM exhibited excellent performance in classification, regression and ranking challenges, and consequently has become popular choice for various ML-based applications that span from medicine48 and climate factors49, all the way to civil engineering50 and fault detection51. Moreover, innovative design provides support for parallel and distributed processing, allowing it to be scaled with great efficiency over several computing machines. The most commonly optimized LightGBM hyperparameters encompass the count of leaves in a tree (principal parameter to control the tree complexity), maximum depth and learning rate, among others. The model’s level of performance is significantly affected by proper choice of these values.

Stochastic optimizers

Metaheuristics optimization encompasses a set of algorithms aimed at discovering approximate resolutions for complex optimization challenges (NP-hard), which are impractical to solve exactly with administration of deterministic conventional mechanisms. Many of these methods take inspiration from natural events, such as evolution or collective behavioral patterns52. These are especially valuable to resolve large-scale, nonlinear, or unstructured problems where deterministic techniques fall short because of excessive resource requirements and/or infeasible time-frames53. Metaheuristics provide versatility and scale well, allowing them to explore a wide search domain while keeping the risk of becoming trapped in local optima at minimum. Despite they are not able to guarantee the establishment of the global optimal solution, they can discover near-optimal results in acceptable time. Swarm intelligence algorithms represent a subset of these optimization techniques, drawing inspiration from nature, where plain individuals can express complex and smart collective behavior. Due to their distributed nature, algorithms belonging to this group are particularly effective for tackling large, high-dimensional optimization problems54,55.

Notable exemplars of metaheuristics approaches encompass conventional and broadly-respected algorithms such as particle swarm optimization (PSO)56, genetic algorithm (GA)57, variable neighborhood search (VNS)58, artificial bee colony (ABC)59, firefly algorithm (FA)60 and bat algorithm (BA)61. A considerable portion of more recent techniques were introduced in the last few years, such as COLSHADE62, crayfish optimization algorithm (COA)22, reptile search algorithm (RSA)24, red fox optimizer (RFO)23 and recently developed sinh cosh optimizer (SCHO)63. Methods belonging to this particular family of algorithms are well known as powerful optimizers, and as such were applied in practice in a broad range of application domains, like time series forecasting64, software development17,65, healthcare31, cloud and edge computing systems66,67 and power grids tuning68. Moreover, the application of metaheuristics algorithms in the domain of AI models hyperparameters optimization can remarkably enhance their performance69, as evidenced by numerous preceding studies70,71,72. IoT networks were also leveraged with the application of metaheuristics optimization algorithms73, addressing challenges like data aggregation74, blockchain performance optimization75 and security76,77.

Methods

This unit commences by briefly introducing the concepts of the baseline chimp optimization algorithm, followed by its known constraints. After the limitations are discussed, this chapter offers a modified variant of the algorithm that improves the performance of the elementary version.

Baseline Chimp optimization algorithm

The chimp optimization algorithm (ChOA) belongs to the group of swarm intelligence metaheuristics techniques, and it was developed to emulate the hunt technique and collective behavioral patterns of a troop of chimpanzees21. In this approach, chimpanzees are divided into four key subgroups: attackers, chasers, holders, and callers, each contributing uniquely to enhance the optimization procedure. This collaborative approach aids the algorithm to maintain a balance betwixt exploration (search for novel areas) and exploitation (improving existing solutions).

In the baseline ChOA, the attacking group moves in line with their position update pattern, governed by Eq. (5):

here, \(X_{\text {best}}\) denotes the top-performing chimp location, while A and C correspond to the coefficient vectors dynamically adjusted within each round, empowering the exploration procedure.

Individuals belonging to the chasing pack \(X_{\text {chase}}\) update their positions as governed by Eq. (6):

where B and D serve as control variables for maintaining the balance among exploration and exploitation phases.

The individuals belonging to the holder troop \(X_{\text {hold}}\) refresh their positions in line with Eq. (7):

here, E and F serve as supplementary parameters that govern this update.

Finally, the individuals from caller troop \(X_{\text {call}}\) preform position update according to the Eq. (8):

here G and H have similar roles to A and C, ajdusted to the callers’ function of the optimization process.

By iteratively refining positions, ChOA leverages the collective intelligence of the different chimpanzee roles to solve complex optimization tasks, proving to be an efficient method for addressing high-dimensional search domains within a broad spectrum of real-world applications.

Altered ChOA

Notwithstanding excellent optimization characteristics of the relatively novel ChOA algorithm, thorough experiments on the CEC benchmark function collection78 exposed some areas of the algorithm that may be targeted for enhancements. These empirical experiments have showcased that the baseline ChOA could profit from the early bolster of the population diversity. Moreover, baseline algorithm’s converging speed and balance betwixt diversification and intensification stages could also be leveraged. With these opportunities for improvements in mind, several alterations are proposed in this study.

First added alteration targets boosting of the population diversity over the initialization stage, by incorporating the quasi-adaptive learning (QRL)79 procedure to the elementary ChOA. In the modified initialization stage, only a half of the solutions are synthesized by applying the conventional ChOA initialization process. Other half of solutions are synthesized with QRL mechanism to boost diversification in the early phase of the algorithm’s run. Novel solutions are synthesized as quasi-reflexive opposite individuals with respect to the Eq. 9.

here, \(\frac{lb_j + ub_j}{2}\) is the arithmetic mean for each parameter’s search limits, while rnd() represents an arbitrary selection procedure within the given boundaries.

Another modification that was implemented into the ChOA algorithm is the soft rollback mechanism, introduced by this study. If the algorithm stagnates in T/3 iterations (empirically established), where T is the maximum number of iterations, rollback of the entire population to the previous state is performed. Two novel control parameters were introduced to support this alteration, stagnation counter sc and stagnation threshold st. The initial values of these parameters are \(sc=0\) and \(st=\frac{T}{3}\). If there is no improvement in the current iteration, sc is incremented. If the value of sc reaches st, soft rollback is performed. Ultimately, elitism is also applied in the following way. When the rollback is performed, the best individual (having the best fitness value) is kept in the population, while the rest are produced by applying the proposed initialization described above.

Considering all included modifications, the novel algorithm was named iteration stagnation aware ChOA (ISA-ChOA), with the pseudo code given in Algorithm 2. It is also necessary to note that the ISA-ChOA utilizes identical control parameters’ values and their update procedures as suggested by the authors of the baseline algorithm21. Regarding the complexity of the introduced algorithm, it is common to express it in terms of fitness function evaluations (FFEs), since it is the most expensive calculation during the metaheuristics algorithm’s execution. Since soft rollback is executed after every three iterations (if the stagnation is confirmed), the complexity of ISA-ChOA algorithm is in the worst case scenario \(O(n) = N + N \times T + (N-1) \times T / 3\), where N is the count of solutions, while T is the count of iterations. However, in practice, soft rollback is on average triggered only once per run, which is significantly less than the worst case scenario.

Experimental setup

The experiments in this study were conducted with a recent CICIoT2023 intrusion detection dataset34, publicly accessible at https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/iotdataset-2023.html. This dataset was developed to evaluate security analytics programs for practical IoT environments and includes 33 distinct attack variants executed across an IoT topology of 105 devices. These attacks are categorized into seven types: DDoS, DoS, Recon, Web-based, Brute Force, Spoofing, and Mirai. This allows for both binary classification (attack versus benign traffic) and multiclass classification with either 8 classes (normal and each attack type) or 34 classes (normal and each of the 33 individual attacks). Class dispersal of both binary and multiclass problems is showcased within Fig. 1. This research addressed 8-class multiclass prediction task. The original dataset contains 1048575 samples. Due to the immense size of the dataset and overwhelming computing requirements, it has been reduced to 20% of the initial size, by performing stratifying of the target 8 classes to keep the imbalance among classes identical to the original dataset. The resulting dataset contains 209715 samples, and is subsequently separated into 70% training and 30% testing data. Models were validated by applying conventional ML metrics: accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and F1-score.

Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC)80 was opted as the objective function that requires maximization. MCC represents an important indicator particularly when facing imbalanced datasets like CICIoT2023. The imbalance of the utilized dataset is indeed a challenge, however, it reflects a real-world situation, since most of the real-life network traffic is not balanced. Thus, it is crucial that the proposed model should work properly with highly imbalanced data. MCC value is established by utilizing the Equation (10). Moreover, the classification error (which is defined by \(1-accuracy\)) was monitored across all simulations and acted as the indicator function.

here, TP corresponds to the true positive forecasts, TN represents the count of true negative predictions, FP is the amount of false positive predictions, and finally, FN denotes the count of false negative classifications.

CNN set of hyperparameters was tuned within the premier tier of the introduced ML framework. The collection of opted hyperparameters, along with search region limits for each parameter is presented in Table 1. Batch size of 512 was used, with early stopping enabled.

CNN’s intermediate outputs were wired to the framework’s second tier. This collection of outputs were stored within CNN’s classifying activity for every sample in the dataset, and subsequently separated into another 70% training and 30% testing split, which was fed to CatBoost and LightGBM structures throughout their respective tuning processes. The hyperparameters’ collection of CatBoost opted for optimization procedure in this study is showcased in Table 2. Likewise, LightGBM hyperparameters that were tuned are presented in Table 3. These opted parameters are known to have the most influence on the model’s behavior.

The suggested ISA-ChOA metaheuristics was utilized for optimization, and comparative analysis with multiple cutting-edge optimizers was performed. The set of contending algorithms comprised of elementary ChOA21, VNS58, PSO56, BA61, ABC59, WOA81 and RSA24. The contending metaheuristics were separately implemented for the sake of this research, with default configurations of control parameters that were recommended by their respective creators. In case of CNN simulations, every metaheuristics used 8 individuals in the populace, with 5 iterations in each run and 5 separate executions, to account the randomness linked to the stochastic algorithms. Similarly, for CatBoost and LightGBM tuning, metaheuristics used 10 individuals per populace, 10 iterations per run and a total of 30 independent executions. For CNN tuning process the authors opted for smaller population size and number of rounds, since CNN optimization requires considerably more computing resources. A simulation framework flowchart is provided in Fig. 2

Results

This unit showcases the experimental findings from the conducted simulations. In multiclass simulations, the superior outcomes for each category for all tables showing the simulation findings are emphasized in bold font.

Layer 1 CNN multiclass experiments

The simulation findings of the premier tier of the framework, where CNN was optimized with respect to the fitness function (MCC) for multiclass classifying venture, are delivered within Table 4. The proposed ISA-ChOA algorithm dispatched highest ranking results, by attaining the MCC of 0.691852 for the best run and 0.639513 in the worst execution, with mean and median scores of 0.639513 and 0.671254, respectively. On the opposite, the superior stability indicated by the lowest deviation and variance scores was attained by WOA metaheuristics. Despite respectful stability, however, WOA was considerably behind more advanced algorithms regarding other metrics.

Indicator function (set as classification error outlay) results are outlined within Table 5. Once more, the supremacy of the introduced ISA-ChOA metaheuristics may be observed, reflected in the best outcome of 0.137344. ISA-ChOA also outclassed other contending algorithms for the worst, mean and median scores, while again the superior stability of the outcomes was exhibited by WOA metaheuristics.

Violin and swarm plots of the fitness function (MCC) for the multiclass classifying problem are presented within Fig. 3. ISA-ChOA was not able to establish the highest stability of the results, nevertheless, other contenders which obtained better stability of MCC across independent runs did not match the overall superior performance of ISA-ChOA. This is also visible from the swarm plot graph, showing the diversity of the population within the final round of the best execution. Supplementary visualizations of the outcomes are outlined within Fig. 4 through box and swarm plots of the indicator function.

Converging diagrams of both MCC and error rate, for every considered algorithm are outlined within Fig. 5, where it is clear that the proposed ISA-ChOA demonstrated superior convergence, and outclassed all contenders by establishing the best outcome of the fitness function. The same applies for the converging of the error rate (indicator), although it was not specified as the goal for tuning.

Table 6 sets forth a comprehensive evaluation of the top-performing CNN architectures for multiclass classifying challenge, tuned with all optimizers encompassed in comparative evaluation. Even optimized CNNs are frequently struggling to properly detect mirai and recon attacking patterns, which is evident from the provided results. Additionally, PSO-based CNN fails entirely to converge, with abysmal final accuracy. A couple of measurements should be considered for determining the optimal method, including precision, recall and f1-score per each class. Nevertheless, the greatest accuracy among all observed methods was achieved by the suggested ISA-ChOA CNN model, that outclassed other approaches with the final overall accuracy of 0.862656.

The best sets of CNN’s hyperparameter values determined with each regarded optimizer are put forth within Table 7, to provide support for subsequent replication studies. These values may help other scientists that seek to recreate the experimental aftermaths on their own, as these CNN architectures achieved the outcomes shown and discussed within Table 6. Ultimately, additional visualizations in shape of PR curves and confusion matrix for the most suitable model (CNN-ISA-ChOA in this scenario) are outlined within Fig. 6.

The best performing CNN model architectures, and the “tapped” intermediate version are provided visually in Fig. 7, where it can be noted that 32 features were extracted by the CNN.

Layer 2 CatBoost multiclass experiments

The findings of the conducted simulations of the framework’s second tier, in terms of CatBoost tuning process with the MCC set as the fitness function for multiclass classifying venture, are showcased within Table 8. The suggested ISA-ChOA algorithm dispatched highest ranking results, by attaining the best MCC of 0.806747 for the best run with mean score of 0.805208. Moreover, ISA-ChOA shared the best results of worst and median metrics with a couple of other oprimizers. On the opposite, the superior stability indicated by the lowest deviation and variance scores was attained by BA and RSA metaheuristics. Despite respectful stability, however, these algorithms were behind other optimizers regarding the remaining metrics.

Indicator function (set as classification error outlay) findings are outlined within Table 9. Once more, the supremacy of the introduced ISA-ChOA metaheuristics may be observed, reflected in the best outcome for classification error of 0.082222. ISA-ChOA also outclassed other contending algorithms for the mean score, and shared the best outcomes of worst and median metrics with several other optimizers, while the supreme stability of the outcomes was exhibited by baseline ChOA, BA and RSA metaheuristics.

Violin and swarm plots of the fitness function (MCC) for the multiclass classifying problem are presented within Fig. 8. ISA-ChOA was not able to establish the highest stability of the results, nevertheless, other contenders which obtained better stability of MCC across independent runs did not match the overall superior performance of ISA-ChOA. This is also visible from the swarm plot graph, showing the diversity of the population within the final round of the best execution. Supplementary visualizations of the outcomes are outlined within Fig. 9 through box and swarm plots of the classification error rate.

Converging diagrams of both MCC and error rate, for every considered algorithm are outlined within Figs. 10 and 11, where it is clear that the proposed ISA-ChOA demonstrated superior convergence, and outclassed all contenders by establishing the best outcome of the fitness function. The same applies for the converging of the error rate (indicator), although it was not targeted as the goal for tuning.

Table 10 sets forth a comprehensive analysis of the top-performing CatBoost architectures for multiclass classifying challenge, tuned with all optimizers encompassed in comparative evaluation. Even optimized CatBoost models are frequently struggling to properly detect mirai and recon attacking patterns, which is evident from the provided results. A couple of measurements should be considered for determining the optimal method, including precision, recall and f1-score per each class. Nevertheless, the greatest accuracy among all observed methods was achieved by the suggested ISA-ChOA CatBoost model, that outclassed other approaches with the final overall accuracy of 0.917778.

The best sets of CatBoost’s hyperparameter values determined with each regarded optimizer are put forth within Table 11, to provide support for possible subsequent replication experiments. These values may help other scientists that seek to recreate the experimental aftermaths on their own, as these CatBoost architectures achieved the outcomes shown and discussed within Table 10. Ultimately, additional visualization in shape of confusion matrix for the most suitable model (CNN-CB-ISA-ChOA in this scenario) is outlined within Fig. 12.

Layer 2 LightGBM multiclass experiments

The findings of the conducted simulations of the framework’s second tier, in terms of LightGBM tuning process with the MCC set as the fitness function for multiclass classifying venture, are showcased within Table 12. The suggested ISA-ChOA algorithm dispatched supreme level of outcomes for all observed metrics, by attaining the best MCC of 0.996207 for the best run, 0.985756 for the worst execution, with mean and median outcomes of 0.991700 and 0.993378. Moreover, in this experiment, ISA-ChOA obtained the superior stability as well, indicated by the lowest deviation and variance scores of 0.003788 and 0.000014, respectively.

Indicator function (set as classification error outlay) findings are outlined within Table 13. Once again, the supremacy of the proposed ISA-ChOA metaheuristics may be noted, reflected in the best outcome for classification error of 0.001653. ISA-ChOA also outclassed other contending algorithms for the worst, mean and median metrics. The supreme stability of the outcomes was exhibited by ISA-ChOA metaheuristics as well.

Violin and swarm plots of the fitness function (MCC) for the multiclass classifying problem are presented within Fig. 13. ISA-ChOA was able to establish the highest stability of the results, while other contenders which obtained good stability of MCC across independent runs did not match the overall superior performance of ISA-ChOA. This is also visible from the swarm plot graph, showing the diversity of the population within the final round of the best execution. Supplementary visualizations of the outcomes are outlined within Fig. 14 through box and swarm plots of the classification error rate.

Converging diagrams of both MCC and error rate, for every considered algorithm are outlined within Figs. 15 and 16, where it is clear that the proposed ISA-ChOA demonstrated superior convergence, and outclassed all contenders by establishing the best outcome of the fitness function. The same applies for the converging of the error rate (indicator), although it was not targeted as the goal for tuning.

Table 14 sets forth a comprehensive analysis of the top-performing CatBoost architectures for multiclass classifying challenge, tuned with all optimizers encompassed in comparative evaluation. Even optimized CatBoost models are frequently struggling to properly detect mirai and recon attacking patterns, which is evident from the provided results. A couple of measurements should be considered for determining the optimal method, including precision, recall and f1-score per each class. Nevertheless, the greatest accuracy among all observed methods was achieved by the suggested ISA-ChOA LightGBM model, that outclassed other approaches with the final overall accuracy of 0.998346.

The best sets of LightGBM’s hyperparameter values determined with each regarded optimizer are put forth within Table 15, to provide support for possible subsequent replication experiments. These values may help other scientists that seek to recreate the experimental aftermaths on their own, as these CatBoost architectures achieved the outcomes shown and discussed within Table 14. Ultimately, additional visualization in shape of confusion matrix for the most suitable model (CNN-LGBM-ISA-ChOA in this scenario) is outlined within Fig. 17.

Comparison with state of the art classifcaiton models

To demonstrate the improvements attained by utilizing the introduced optimization framework, a comparative analysis between several baseline classifiers is included. Commonly used as well as relatively recent models have all been evaluated including decision trees82, random forests83, KNN84, XGBoost85, AdaBoost86, baseline CatBoost46 and LGBM models as well as a simple multilayer perception (MLP)87 models. The results of this comparative analysis are provided in detail in Table 16. The introduced hybrid framework shows clear advantages over other contemporary optimizers.

Statistical analysis and the best models interpretation

When conducting comparative simulations between optimizers several angles need to be considered when discerning a conclusion. Comparisons in terms of objective function scores are often insufficient to draw a definitive conclusion. Therefore statistical evaluations are conducted to establish if an attained improvement is significant. Two approaches can be taken when comparing metaheuristics, parametric and non-parametric testing. To ensure parametric tests can be safely applied a set of criteria needs to be fulfilled88. These include the independence of runs, a condition fulfilled by conduction individual optimizations using independent random seeds; Homoscedasticity, that is carrying out the Levene’s test89, and with all conditions for the conducted situations attaining a p-value of 0.62, this condition can be considered fulfilled as well; Normality for the attained scores must also be confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk90 test with p-values presented in Table 17. With p-values not meeting the established criteria, normality cannot be confirmed, as the use of parametric test cannot be considered justified.

With the required normality condition not fulfilled non-parametric testing is applied to establish a further comparison. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test91 is applied, and the ISA-ChOA algorithm is compared with other algorithms included in the comparative simulations and the p-value scores are presented in Table 18. As the significance threshold of \(\alpha = 0.05\) is not exceeded, the outcomes attained in the comparative analysis can be considered statistically significant.

Interpretation of the best performing models

In modern AI research model classifications are without a doubt important. However, the contributing factors that allow a model to determine the class of a certain sample can also provide valuable feedback on a model decisions. Feature importance can help highlight hidden biases in the data as well as help reduce input and collected features for future research. While models are often treated by researchers as a black box, by leveraging advanced model interpretation tools, information on feature importances as well as their impact on classification can be computed.

Explainable AI (XAI) methods aim to make ML models significantly more transparent, interpretable, and trustworthy. XAI techniques help stakeholders comprehend how models determine decisions, increasing trust and aiding in regulatory compliance along with ethical AI considerations, which is vital in security applications92. XAI can help users understand which features are critical for predictions, enabling domain experts to validate the model’s logic and performance. Finally, this process may aid in feature engineering by highlighting useful attributes and de-emphasizing redundant ones.

A notable contribution in terms of feature importance is the development and application of Shapely additive explanations (SHAP)93 techniques. Based on game theory concepts SHAP analysis can help highlight feature importance on the global as well as local level. SHAP interpretations on a global scale are presented in Fig. 18, while per class interpretations are provided in swarm diagrams for each of the 7 glasses in Fig. 19. Additionally, it is important to note that SHAP analysis did not indicate any significant bias toward specific classes associated with certain features.

Conclusion and future work

Integrating the Metaverse with IoT is crucial, since IoT devices deliver real-time data and enable smooth connection betwixt the physical and virtual realms. Nevertheless, since attacks on IoT systems have become increasingly sophisticated, conventional security systems have struggled to keep up. Consequently, adaptive AI-driven methods were investigated to more appropriate tackle the challenges of today’s IoT infrastructure and create safe environment for users. Effective AI models must manage intricate data correlations and remain adaptable to evolving conditions. Achieving optimal results also required careful choice of algorithms and hyperparameter tuning. This study proposed a two-tier hybrid architecture that combines CNN with sophisticated ML classifiers, CatBoost and LightGBM. Metaheuristics techniques were employed to enhance performance, optimize the models, and refine parameter selection. Utilizing a realistic dataset, the framework was evaluated through comparative analysis, targeting multi-class classification to identify various types of attacks against IoT systems. A custom-altered optimizer was developed particularly for this study, resulting in the best-performing models, which attained a supreme accuracy level of 99.83% for multi-class classification. Afterwards, a rigorous statistical analysis outlined significant enhancements in comparison to the baseline metaheuristics and other contenting optimizers. Lastly, explainable AI method SHAP was employed on the best-performing model for understanding the significance of each feature and model’s decision making process.

The methodology introduced in this study yielded a couple of benefits, notably achieving enhanced optimizer’s performance over contemporary algorithms. Framework’s two-tier architecture outperformed baseline CNNs while keeping computational demands within acceptable levels. For practical implementations, the suggested system might be deployed on IoT nodes for traffic management, requests processing, and mitigation of network-wide assaults. In the context of the Metaverse, this approach could improve general device safety, promoting trust and reinforcing the integration of virtual and physical domains. This advanced system could also support real-time attack detection in IoT by processing high-dimensional, streaming data, identifying anomalies, and mitigating threats promptly.

Although showcased study achieved promising results, some limitations still remain. The comparative evaluations included just a small selection of optimizing algorithms, and optimizations were executed with a relatively small population sizes and number of iterations. Thus, future work aims to tackle these constraints if supplementary computing resources become available. Expanding the pool of optimization algorithms and conducting evaluations with larger population sizes and iterations could provide more robust insights and even stronger conclusions. Additionally, the altered metaheuristics described here could be further applied to address other pressing challenges, enhancing performance and equipping scientists with improved tools for hyperparameter optimization of ML models. The application of the developed methods in real-time or streaming environments, where data evolves continuously, represents another promising avenue for development.

Data availibility

The original dataset used in this study is freely available via URL: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/index.html Reduced dataset used in the experiments is available via URL: https://github.com/profzivkovic/CICIoT2023_IoT_Intrusion_reduced

References

Mystakidis, S. Metaverse. Encyclopedia 2, 486–497 (2022).

Veeraiah, V. et al. Enhancement of meta verse capabilities by iot integration. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), 1493–1498 (IEEE, 2022).

Wang, H. et al. A survey on the metaverse: The state-of-the-art, technologies, applications, and challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 14671–14688 (2023).

Heidari, A., Amiri, Z., Jamali, M. A. J. & Jafari, N. Assessment of reliability and availability of wireless sensor networks in industrial applications by considering permanent faults. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 36, e8252 (2024).

Hwang, G.-J. & Chien, S.-Y. Definition, roles, and potential research issues of the metaverse in education: An artificial intelligence perspective. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 3, 100082 (2022).

Li, K. et al. When internet of things meets metaverse: Convergence of physical and cyber worlds. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 4148–4173 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. A survey on metaverse: Fundamentals, security, and privacy. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 25, 319–352 (2022).

Mrabet, H., Belguith, S., Alhomoud, A. & Jemai, A. A survey of iot security based on a layered architecture of sensing and data analysis. Sensors 20, 3625 (2020).

Tawalbeh, L., Muheidat, F., Tawalbeh, M. & Quwaider, M. Iot privacy and security: Challenges and solutions. Appl. Sci. 10, 4102 (2020).

Zhao, R., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Y., Lan, R. & Hua, Z. Metaverse: Security and privacy concerns. J. Metaverse 3, 93–99 (2023).

Cheng, R., Chen, S. & Han, B. Toward zero-trust security for the metaverse. IEEE Commun. Mag. 62, 156–162 (2023).

Huang, Y., Li, Y. J. & Cai, Z. Security and privacy in metaverse: A comprehensive survey. Big Data Min. Anal. 6, 234–247 (2023).

Asadi, M., Jamali, M. A. J., Heidari, A. & Navimipour, N. J. Botnets unveiled: A comprehensive survey on evolving threats and defense strategies. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 35, e5056 (2024).

Al-Garadi, M. A. et al. A survey of machine and deep learning methods for internet of things (iot) security. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 22, 1646–1685 (2020).

Hussain, F., Hussain, R., Hassan, S. A. & Hossain, E. Machine learning in iot security: Current solutions and future challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 22, 1686–1721 (2020).

Wolpert, D. & Macready, W. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1, 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.585893 (1997).

Petrovic, A. et al. Exploring metaheuristic optimized machine learning for software defect detection on natural language and classical datasets. Mathematics 12, 2918 (2024).

Zivkovic, M. et al. Hybrid cnn and xgboost model tuned by modified arithmetic optimization algorithm for covid-19 early diagnostics from x-ray images. Electronics 11, 3798 (2022).

Salb, M. et al. Enhancing internet of things network security using hybrid cnn and xgboost model tuned via modified reptile search algorithm. Appl. Sci. 13, 12687 (2023).

Jovanovic, L. et al. Improving phishing website detection using a hybrid two-level framework for feature selection and xgboost tuning. J. Web Eng. 22, 543–574 (2023).

Khishe, M. & Mosavi, M. Chimp optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 149, 113338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113338 (2020).

Jia, H., Rao, H., Wen, C. & Mirjalili, S. Crayfish optimization algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 1919–1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-023-10567-4 (2023).

Połap, D. & Woźniak, M. Red fox optimization algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 166, 114107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114107 (2021).

Abualigah, L., Elaziz, M. A., Sumari, P., Geem, Z. W. & Gandomi, A. H. Reptile search algorithm (rsa): A nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimizer. Expert Syst. Appl. 191, 116158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.116158 (2022).

Thapa, S. & Mailewa, A. The role of intrusion detection/prevention systems in modern computer networks: A review. In Conference: Midwest Instruction and Computing Symposium (MICS) 53, 1–14 (2020).

Amiri, Z., Heidari, A., Navimipour, N. J., Esmaeilpour, M. & Yazdani, Y. The deep learning applications in iot-based bio-and medical informatics: a systematic literature review. Neural Comput. Appl. 36, 5757–5797 (2024).

Saheed, Y. K., Abdulganiyu, O. H., Majikumna, K. U., Mustapha, M. & Workneh, A. D. Resnet50-1d-cnn: A new lightweight resnet50-one-dimensional convolution neural network transfer learning-based approach for improved intrusion detection in cyber-physical systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 45, 100674 (2024).

Tsai, C.-F., Hsu, Y.-F. & Yen, D. C. Hybrid machine learning model for intrusion detection. Appl. Sci. 10, 6620. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10196620 (2020).

Alamro, H. et al. Modelling of blockchain assisted intrusion detection on iot healthcare system using ant lion optimizer with hybrid deep learning. IEEE Access (2023).

Goran, R. et al. Identifying and understanding student dropouts using metaheuristic optimized classifiers and explainable artificial intelligence techniques. IEEE Access (2024).

Bacanin, N. et al. Improving performance of extreme learning machine for classification challenges by modified firefly algorithm and validation on medical benchmark datasets. Multimedia Tools and Applications 1–41 (2024).

Saheed, Y. K., Abdulganiyu, O. H. & Tchakoucht, T. A. Modified genetic algorithm and fine-tuned long short-term memory network for intrusion detection in the internet of things networks with edge capabilities. Appl. Soft Comput. 155, 111434 (2024).

Saheed, Y. K., Omole, A. I. & Sabit, M. O. Ga-madam-iiot: A new lightweight threats detection in the industrial iot via genetic algorithm with attention mechanism and lstm on multivariate time series sensor data. Sens. Int. 6, 100297 (2025).

Neto, E. C. P. et al. Ciciot 2023: A real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in iot environment. Sensors 23, 5941 (2023).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Albawi, S., Bayat, O., Al-Azawi, S. & Ucan, O. N. Social touch gesture recognition using convolutional neural network. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2018, 6973103 (2018).

Nair, V. & Hinton, G. E. Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines. In Proc. of the 27th international conference on machine learning (ICML-10), 807–814 (2010).

Hinton, G. et al. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: The shared views of four research groups. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 29, 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2012.2205597 (2012).

Ranjan, R., Sankaranarayanan, S., Castillo, C. D. & Chellappa, R. An all-in-one convolutional neural network for face analysis. In 2017 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017), 17–24 (IEEE, 2017).

Lombardi, F. & Marinai, S. Deep learning for historical document analysis and recognition-a survey. J. Imaging 6, 110 (2020).

Cai, L., Gao, J. & Zhao, D. A review of the application of deep learning in medical image classification and segmentation. Ann. Transl. Med.8 (2020).

Chattopadhyay, A., Hassanzadeh, P. & Pasha, S. Predicting clustered weather patterns: A test case for applications of convolutional neural networks to spatio-temporal climate data. Sci. Rep. 10, 1317 (2020).

Bjekic, M. et al. Wall segmentation in 2d images using convolutional neural networks. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9, e1565 (2023).

Bukumira, M. et al. Carrot grading system using computer vision feature parameters and a cascaded graph convolutional neural network. J. Electron. Imaging 31, 061815–061815 (2022).

Micci-Barreca, D. A preprocessing scheme for high-cardinality categorical attributes in classification and prediction problems. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 3, 27–32 (2001).

Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. Catboost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems31 (2018).

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems30 (2017).

Sinha, B. B., Ahsan, M. & Dhanalakshmi, R. Lightgbm empowered by whale optimization for thyroid disease detection. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 15, 2053–2062 (2023).

Guo, X. et al. Critical role of climate factors for groundwater potential mapping in arid regions: Insights from random forest, xgboost, and lightgbm algorithms. J. Hydrol. 621, 129599 (2023).

Li, L. et al. A lightgbm-based strategy to predict tunnel rockmass class from tbm construction data for building control. Adv. Eng. Inform. 58, 102130 (2023).

Lao, Z. et al. Intelligent fault diagnosis for rail transit switch machine based on adaptive feature selection and improved lightgbm. Eng. Fail. Anal. 148, 107219 (2023).

Emambocus, B. A. S., Jasser, M. B. & Amphawan, A. A survey on the optimization of artificial neural networks using swarm intelligence algorithms. IEEE Access 11, 1280–1294 (2023).

Tawhid, M. A. & Ibrahim, A. M. An efficient hybrid swarm intelligence optimization algorithm for solving nonlinear systems and clustering problems. Soft. Comput. 27, 8867–8895 (2023).

Tang, J., Liu, G. & Pan, Q. A review on representative swarm intelligence algorithms for solving optimization problems: Applications and trends. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 8, 1627–1643 (2021).

Rostami, M., Berahmand, K., Nasiri, E. & Forouzandeh, S. Review of swarm intelligence-based feature selection methods. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 100, 104210 (2021).

Kennedy, J. & Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proc. of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks, vol. 4, 1942–1948. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNN.1995.488968 (1995).

Mirjalili, S. Genetic Algorithm 43–55 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

Mladenović, N. & Hansen, P. Variable neighborhood search. Comput. Oper. Res. 24, 1097–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0548(97)00031-2 (1997).

Karaboga, D. & Basturk, B. A powerful and efficient algorithm for numerical function optimization: artificial bee colony (abc) algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 39, 459–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10898-007-9149-x (2007).

Yang, X.-S. & He, X. Firefly algorithm: recent advances and applications. Int. J. Swarm Intell. 1, 36–50 (2013).

Yang, X.-S. & He, X. Bat algorithm: literature review and applications. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 5, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIC.2013.055093 (2013).

Gurrola-Ramos, J., Hernàndez-Aguirre, A. & Dalmau-Cedeño, O. Colshade for real-world single-objective constrained optimization problems. In 2020 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/CEC48606.2020.9185583 (2020).

Bai, J. et al. A sinh cosh optimizer. Knowl.-Based Syst. 282, 111081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111081 (2023).

Damaševičius, R. et al. Decomposition aided attention-based recurrent neural networks for multistep ahead time-series forecasting of renewable power generation. PeerJ Comput. Sci.10 (2024).

Zivkovic, T., Nikolic, B., Simic, V., Pamucar, D. & Bacanin, N. Software defects prediction by metaheuristics tuned extreme gradient boosting and analysis based on shapley additive explanations. Appl. Soft Comput. 146, 110659 (2023).

Predić, B. et al. Cloud-load forecasting via decomposition-aided attention recurrent neural network tuned by modified particle swarm optimization. Complex Intell. Syst. 10, 2249–2269 (2024).

Vakili, A. et al. A new service composition method in the cloud-based internet of things environment using a grey wolf optimization algorithm and mapreduce framework. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 36, e8091 (2024).

Stoean, C. et al. Metaheuristic-based hyperparameter tuning for recurrent deep learning: application to the prediction of solar energy generation. Axioms 12, 266 (2023).

Velasco, L., Guerrero, H. & Hospitaler, A. A literature review and critical analysis of metaheuristics recently developed. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 31, 125–146 (2024).

Babic, L. et al. Leveraging metaheuristic optimized machine learning classifiers to determine employee satisfaction. In International Conference on Multi-Strategy Learning Environment, 337–352 (Springer, 2024).

Pavlov-Kagadejev, M. et al. Optimizing long-short-term memory models via metaheuristics for decomposition aided wind energy generation forecasting. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 45 (2024).

Dobrojevic, M. et al. Cyberbullying sexism harassment identification by metaheurustics-tuned extreme gradient boosting. Comput. Mater. Contin. 80, 4997–5027 (2024).

Amiri, Z., Heidari, A., Zavvar, M., Navimipour, N. J. & Esmaeilpour, M. The applications of nature-inspired algorithms in internet of things-based healthcare service: A systematic literature review. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 35, e4969 (2024).

Heidari, A., Shishehlou, H., Darbandi, M., Navimipour, N. J. & Yalcin, S. A reliable method for data aggregation on the industrial internet of things using a hybrid optimization algorithm and density correlation degree. Cluster Computing 1–19 (2024).

Zanbouri, K. et al. A gso-based multi-objective technique for performance optimization of blockchain-based industrial internet of things. Int. J. Commun Syst. 37, e5886 (2024).

Savanović, N. et al. Intrusion detection in healthcare 4.0 internet of things systems via metaheuristics optimized machine learning. Sustainability 15, 12563 (2023).

Dakic, P. et al. Intrusion detection using metaheuristic optimization within iot/iiot systems and software of autonomous vehicles. Sci. Rep. 14, 22884 (2024).

Luo, W., Lin, X., Li, C., Yang, S. & Shi, Y. Benchmark functions for cec 2022 competition on seeking multiple optima in dynamic environments (2022).

Rahnamayan, S., Tizhoosh, H. R. & Salama, M. M. Quasi-oppositional differential evolution. In 2007 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, 2229–2236 (IEEE, 2007).

Chicco, D. & Jurman, G. The advantages of the matthews correlation coefficient (mcc) over f1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 21, 1–13 (2020).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008 (2016).

de Ville, B. Decision trees. WIREs Comput. Stat. 5, 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.1278 (2013).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Kramer, O. K-Nearest Neighbors 13–23 (Springer, 2013).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proc. of the 22nd ACM Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794 (2016).

Hastie, T., Rosset, S., Zhu, J. & Zou, H. Multi-class adaboost. Stat. Interface 2, 349–360 (2009).

Zou, J., Han, Y. & So, S.-S. Overview of Artificial Neural Networks 14–22 (Humana Press, 2009).

LaTorre, A. et al. A prescription of methodological guidelines for comparing bio-inspired optimization algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 67, 100973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2021.100973 (2021).

Schultz, B. B. Levene’s test for relative variation. Syst. Biol. 34, 449–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/34.4.449 (1985).

Shapiro, S. S. & Francia, R. S. An approximate analysis of variance test for normality. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 67, 215–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1972.10481232 (1972).

Woolson, R. F. In Encyclopedia of Biostatistics (Wiley, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1002/0470011815.b2a15177.

Saheed, Y. K. & Chukwuere, J. E. Xaiensembletl-iov: A new explainable artificial intelligence ensemble transfer learning for zero-day botnet attack detection in the internet of vehicles. Results Eng. 24, 103171 (2024).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions 1705, 07874 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, grant No. 7373, characterizing crises-caused air pollution alternations using an artificial intelligence-based framework (crAIRsis), and grant No. 7502, Intelligent Multi-Agent Control and Optimization applied to Green Buildings and Environmental Monitoring Drone Swarms (ECOSwarm).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and M.Z. conceived the experiments, L.J. and N.B. conducted the experiments, M.D.J. and B.N. analyzed the results, J.P., M.A.S. and M.M. wrote first draft of the manuscript. All authors were included in writing the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antonijevic, M., Zivkovic, M., Djuric Jovicic, M. et al. Intrusion detection in metaverse environment internet of things systems by metaheuristics tuned two level framework. Sci Rep 15, 3555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88135-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88135-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A novel lightweight deep learning framework using enhanced pelican optimization for efficient cyberattack detection in the Internet of Things environments

Journal of Engineering and Applied Science (2025)

-

CatBoost with physics-based metaheuristics for thyroid cancer recurrence prediction

BioData Mining (2025)

-

An optimized anomaly detection framework in industrial control systems through grey wolf optimizer and autoencoder integration

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A prediction model for microseismic signals based on kernel extreme learning machine optimized by Harris Hawks algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Elite Bernoulli-based mutated dung beetle algorithm for global complex problems and parameter estimation of solar photovoltaic models

Scientific Reports (2025)