Abstract

There’s more to a healthy diet than merely getting the desirable calories. At the present cross-sectional study, dietary consumption was measured using 24-hour dietary recall method. Nutrient density was evaluated using the NRF 9.3 index, which is based on nine recommended nutrients and three nutrients to limit. The link between carbohydrate, protein, fat, fiber and sugar intake at breakfast and the nutrient density in subsequent meals was evaluated using dose-response analysis. A total of 427 adults (199 men and 228 women) were included. The study found an inverse relationship between sugar intake at breakfast and nutrient density at lunch. Specifically, consuming up to 10 g of sugar at breakfast was associated with a reduction in the NRF profile, Additionally, breakfasts containing 12 g of fat were linked to the lowest nutrient density (p non-linearity < 0.001). The dose-response test showed a non-linear relationship (p non-linearity < 0.001); the intake of fiber in breakfast up to 1.5 g was associated with a steep increase in dinner NRF while higher intakes resulted in a more gradual slope of improvement (p non-linearity < 0.001). This study revealed that increment in fat and sugar intake at breakfast is associated with decrease in NRF score at lunch. Moreover, increasing fiber consumption at breakfast is associated with increasing the dinner quality. Consuming a higher quality breakfast is associated with better overall diet quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A healthy diet is about more than just the right number of calories. Foods that contain similar calories are very different in terms of nutrients. Choosing nutrient-dense foods has been a key focus of dietary guidelines for decades, starting with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Consumers were encouraged to seek out nutrient-rich (NRF) foods over arbitrary calories1. This emphasis continues in the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which stress the importance of nutrient-dense foods across all life stages. The current guidelines advocate for ‘making every bite count’ by prioritizing nutrient-rich foods, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean proteins, and low-fat dairy, while limiting added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium. This approach highlights the importance of adopting healthy eating patterns over time to support overall health. According to the FDA, nutrient density is the ratio of the amount of beneficial nutrients compared to the energy content of food per reference amount customarily consumed2. Nutrient-dense foods are those that provide nutrients that are more beneficial to your overall diet than calories. Ready-to-eat meals with high energy are usually cheaper and more chosen3. Research suggests that diets with a high energy density tend to have lower overall quality4.

Breakfast, often addressed as the most important meal of the day, plays a crucial role in providing essential nutrients and energy to kickstart the day’s activities5. In recent years, scientific interest has surged in investigating how the composition of breakfast influences subsequent eating behaviors and overall nutritional status6. Skipping breakfast has been found to be associated with unhealthy habits, and chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease7. According to a cross-sectional study on 7500 adults, individuals with a lower dietary energy density consumed more vitamins A, C, and B6, folate, iron, calcium, and potassium in comparison to those with a higher dietary energy density8. There is a correlation between a lower dietary energy density and higher adherence to dietary requirements for micronutrient intake9. Understanding the nutrient composition of meals and the ways in which different meal patterns affect diet quality may help elucidate important diet-disease relationships10. Hence, the present cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the association between nutrient density of breakfast and nutrient density of subsequent meals among Iranian adults.

Methods

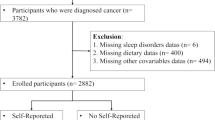

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study recruited eligible individuals from health centers in Tehran, aged 20–59 years, using a convenience sampling technique. Recruitment involved direct invitations extended to individuals visiting the centers, and participants were screened for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria encompassed diagnosed chronic diseases (e.g., kidney, liver, and pulmonary diseases), diabetes, hormonal and cardiovascular diseases, pregnancy, lactation, intake of specific medications or supplements (e.g., slimming drugs, hormones, sedatives, thermogenic supplements like caffeine and green tea, conjugated linoleic acid, etc.), as well as active infectious or inflammatory conditions. All participants provided written informed consent; the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. (Ethic Number: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1401.747(.

Dietary assessment

The dietary intake of the participants was assessed based on three 24-hour dietary. Participants completed the first 24-hour dietary recall and other questionnaires, including IPAQ on the same day they provided written informed consent. The second and third 24-hour dietary recalls were conducted via phone calls without prior notification, on non-consecutive days within two weeks, with one recall conducted on a weekday and the other on a weekend day to capture usual intake pattern.

Daily food intake was converted into grams per day using household measurements and Nutritionist IV software for Iranian foods11.

Diet quality

Mediterranean diet score (MDS) was calculated as a measure of diet quality. The MDS represents a Mediterranean diet and was calculated based on the consumption of nine different components (vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, grains, fish, ratio of PUFAs to SFAs, meat and dairy products). For each component, subjects with intakes above or equal to the median were given a score of 1 (those with intakes below this value were scored 0), except for meat and dairy products, for which the score was reversed. The scores of all nine components were summed and divided into an overall range of 0 to 9, where a higher score indicated better adherence to the Mediterranean diet. The validity of the MDS has been demonstrated in various studies and this index has been used in numerous studies across different geographic regions, including Iran12. Frequent epidemiological studies and preventive trials have shown that the Mediterranean diet protects against cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and other chronic conditions13,14.

Nutrient density

Fulgoni and colleagues (2010) developed and validated a nutrient-rich food index (NRF), called NRF9.3, using algorithms that have the best predictive relationship with diet quality15. The NRF9.3 index is based on nine positive or recommended nutrients (protein, fiber, vitamins A, C, and D, calcium, iron, potassium, and magnesium) and three negative or adverse nutrients (saturated fat, added sugars or total sugars, and sodium). The total percentage of daily values for the nine positive nutrients minus the total percentage of maximum recommended values for the three adverse nutrients, all calculated per 100 kilocalories or a reference amount typically consumed and capped at 100%, were considered. In the mentioned study, the NRF index was analyzed using NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data, and an association was found between the intake of nutrient-dense foods, lower energy intake, overall higher dietary quality, and improved health outcomes. In this study, we utilized the NRF index to examine the nutrient density.

Covariates

The covariates we included in the analysis were demographic characteristics such as age, sex, education, smoking, occupation and marital status. Participants also filed out the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) to measure the physical activity level, which has been validated in the Iranian population16.

Statistical analysis

General characteristics of study participants according to sex were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables, and Chi-squared (χ2) for categorical variables. The dietary intakes of participants were calculated separately for the entire day as well as for the three meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner), categorized by sex, using ANCOVA analysis, with adjustment for age, sex, physical activity, education, smoking, marriage and occupation status, body mass index and energy intake. Moreover, logistic regression was used for assessing the odds of diet quality in categories of breakfast quality, using PSS software (SPSS Inc., version 27), and p < 0.05 was defined as significant. Dose-response figures were created to examine the relationship between nutrient intake at breakfast (grams of protein, fat, carbohydrate, fiber, and sugar) and nutrient density scores at lunch and dinner (NRF) as well as the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS). The mean difference reflects the average change in nutrient density scores based on varying levels of breakfast nutrient intake. The STATA Statistical Software (StataMP 17. Stata Corp., College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) was used to perform dose-response analysis. The instances of underreporting and overreporting were identified as energy intakes below 500 or above 3500 kcal for women, and below 800 or above 4200 kcal for men17.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent; the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. (IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1401.747)

Results

The general characteristics of the study participants (n = 427) are presented in Table 1. The study included 433 participants, with 427 analyzed after 6 cases were removed due to over and under reporting, with 199 men and 228 women. The average age of the participants was 38.40 ± 9.51 years, with a mean BMI of 27.79 ± 13.03 (kg/m²). Women in the low physical activity group were significantly more numerous than men, while the number of men in the moderate and high physical activity groups was greater than that of women (P = 0.03). Dietary intake of participants at breakfast, lunch and dinner is depicted in Tables 2, 3 and 4. The energy intake at breakfast was significantly higher in men (467.53 ± 230.58) (kcal) compared to women (339.01 ± 162.62) (kcal) (P < 0.001). Regarding the distribution of macronutrients, no significant difference was observed between the two sexes. The energy intake at lunch was significantly higher in men (684.02 ± 235.99) (kcal) compared to women (532.38 ± 251.67) (kcal) (P < 0.001). In regards to the distribution of macronutrients, carbohydrate intake at lunch was significantly higher in men with a mean and standard deviation of 84.94 ± 36.13 g than in women with a mean and standard deviation of 61.27 ± 29.69 g, P = 0.037). The energy intake at dinner was significantly higher in men (671.74 ± 271.08) (kcal) compared to women (494.01 ± 224.60) (kcal) (P < 0.001). Regarding the distribution of macronutrients, no significant difference was observed between the two sexes (Table 5).

The mean and standard deviation of nutrition composition and density of meals are shown in The mean and standard deviation of energy percentage from carbohydrates in breakfast, lunch and dinner were 59.88 ± 14.98%, 47.89 ± 12.82% and 50.06 ± 13.20% respectively. The mean and standard deviation of the percentage of energy from protein in breakfast, lunch and dinner were 12.25 ± 4.30%, 18.07 ± 7.80% and 17.22 ± 6.70%, respectively. The mean value and standard deviation of energy percentage from fat in breakfast, lunch and dinner were 27.88 ± 13.28%, 34.04 ± 12.54% and 32.72 ± 14.27%, respectively. The average intake of fiber per 1000 kcal in three meals of breakfast, lunch and dinner was 4.54 ± 4.47 g/1000 kcal, 5.88 ± 4.82 g/1000 kcal and 7.15 ± 4.97 g/1000 kcal, respectively. The mean and standard deviation of NRF index in three meals of breakfast, lunch and dinner were calculated as 49.04 ± 53.12, 133.33 ± 82.53 and 160.16 ± 149.53, respectively.

The participants in both groups of low and high breakfast quality did not have a significant difference in the amount of energy intake in the lunch meal (595.20 ± 253.93 kcal vs. 611.16 ± 257.71 kcal and P = 0.115). Nevertheless, the lunch quality score was higher in the higher quality breakfast class (126.15 ± 80.00) than the participants in the lower quality breakfast class (90.140 ± 84.44), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.221). (Table 6)

The energy intake at dinner in the group of participants who consumed a higher-quality breakfast (559.73 ± 280.44 kcal) compared to those who consumed a lower-quality breakfast (594.17 ± 243.01 kcal) had no statistically significant difference (P = 0.340). However, the dinner quality score in the first group was significantly higher than the second group (139.56 ± 119.46 vs. 180.14 ± 172.40 and P = 0.014) (Table 6).

The odds ratios and 95% CI of diet quality score across tertiles breakfast quality are presented in Table 7. The nutrient density and quality of breakfast increased from the first tertile to the third tertile. The better the quality of breakfast, the higher the odds of having a higher quality diet (OR = 7.55, 95%CI: 4.21–13.53, and P = 0.001).

The dose-response relationship between the nutrition composition of breakfast and nutrient density of lunch is drawn in Fig. 1. This study failed to observe any significant dose-response association between carbohydrate, protein and fiber intake at breakfast and nutrient density of lunch (respectively p non−linearity = 0.071, p non−linearity = 0.0341 and p non−linearity = 0.886). indicates an open U-shaped dose-response association between fat intake at breakfast and nutrient density at lunch. In fact, the lowest nutrient density at lunch was seen in the dose of 12 g of fat intake at breakfast (p non−linearity < 0.001). We observed an inverse non-linear relationship (p non−linearity < 0.001) between sugar intake at breakfast and NRF at lunch; so that the intake of sugar up to 10 g in breakfast was significantly associated with a decrease in the NRF profile at lunch (Fig. 1).

The dose-response relationship between the nutrition composition in breakfast and the nutrient density of dinner is shown in Fig. 2. Our study failed to detect any significant non-linear relationship between carbohydrate, protein, fat and sugar intake at breakfast and dinner NRF (respectively p non−linearity = 0.883, p non−linearity = 0.108, p non−linearity = 0.689 and p non−linearity = 0.640). In regards to fiber, the dose-response test showed a non-linear relationship (p non−linearity < 0.001); the intake of fiber in breakfast up to 1.5 g was associated with a steeper positive trend in the NRF of dinner, while higher intakes were associated with a more gradual increase (Fig. 2).

The dose-response relationship between the nutrition composition in breakfast and the Mediterranean diet score is shown in Fig. 3. The present study revealed a U-shaped, non-linear dose-response association between the intake of carbohydrates in breakfast and the overall quality of the diet (p non−linearity = 0.039). In regards to protein intake, intake of more than 10 g in breakfast showed an upward dose-response curve and higher diet quality (p non−linearity < 0.001). In relation to the dose-response diagram of fat and diet quality, an inverted U-shape correlation was observed (p non−linearity < 0.001). We also found a non-linear relationship (p non−linearity = 0.004) between fiber intake at breakfast and the Mediterranean diet score. We observed a non-linear relationship between sugar intake in breakfast and the Mediterranean diet score (p non−linearity < 0.001) (Fig. 3). In fact, sugar intakes at breakfast of up to 10 g were associated with a decline in the Mediterranean Diet Score, whereas intakes exceeding 10 g were associated with an upward trend in the score.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, the dose-response analysis showed a positive non-linear relationship between fiber intake at breakfast and nutrient density of dinner and an inverse non-linear one between fat and sugar intake at breakfast and nutrient density of lunch. In addition, in this study, it was seen that individuals who consume a higher quality breakfast did not have a significant difference in terms of energy intake at subsequent meals compared to the individuals in the opposite group, but those in the first group, consumed the subsequent meals with better quality. Finally, the present study has concluded that consuming a higher quality breakfast is associated with better overall diet quality.

While previous studies have investigated the association between breakfast consumption and diet quality18,19, no study has assessed the link between breakfast composition and nutrient density of subsequent meals. A cross-sectional study of 902 Egyptian adults found that regularly consuming a breakfast consisting of moderately energy-dense, high-nutrient foods may be a simple daily habit associated with better vascular health19. Another cross-sectional study in Spain found that eating breakfast was generally associated with healthier food choices or eating habits20. In one of his articles, Drewnowski stated that breakfast consumption is associated with higher NRF9.3 scores21.

Nutrient profiling is a technique used to rank or classify foods based on their nutritional value. Nutrient profiling can also help identify nutrient-dense, affordable, and sustainable foods. Originally, this method was used to examine foods individually, but according to Drewnowski, this contradicts the long-standing nutritional principle that there are no “good” or “bad” foods—only “good” and “bad” diets. Nutrient profiling models are intended to capture nutrient density of foods22. According to available studies, the standard NRF9.3 nutrient density scores are generally distributed along a continuum that stretches from sugar to spinach22.

In general, it has been suggested that consuming breakfast -in comparison to skipping breakfast- is associated with healthy food intake throughout the day23,24,25. The population in our study were breakfast consumer -rather than breakfast skippers-, and the NRF index exhibited an increasing trend from breakfast to dinner. The finding that higher fat and sugar intake at breakfast is associated with lower nutrient density at lunch might be explained by various factors. One possibility is that individuals who consume high-fat and high-sugar breakfasts may be inclined to choose less nutritious options for subsequent meal26. It’s also plausible that certain breakfast foods high in fat and sugar content might be lower in other essential nutrients, contributing to a lower overall nutrient density in subsequent meals27.

In our study, it was revealed that increasing fiber intake at breakfast is associated with better dinner quality. This finding is in line with previous works. While no study has investigated the relationship between nutrition composition in breakfast and the nutrient density of subsequent meals before, an umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis of observational studies concluded that higher fiber intake is associated with healthier diet28. Another study recently has stated that the lower ratios of carbohydrates-to-fiber is associated with better diet quality29. Such results have been supported in a cross-sectional observational trial of 358 healthy United States adults30. This finding has been found in children as well31,32. A review of available studies suggests that eating breakfast is associated with higher quality diets33. Similarly, the results of a study on 19,913 Canadian adults showed that breakfast with higher micronutrient content was associated with better diet quality34.

The results of this study underscore the importance of a nutrient-dense breakfast in influencing the overall dietary quality. As shown in Table 7, participants in the highest tertile of breakfast quality were over seven times more likely to achieve a higher overall diet quality compared to those in the lowest tertile. This finding reinforces the critical role of breakfast composition in setting the dietary tone for the rest of the day.

This strong association could be attributed to several factors. First, a nutrient-dense breakfast may promote satiety and regulate appetite35, reducing the consumption of low-quality, energy-dense foods later in the day. Second, individuals who prioritize a high-quality breakfast may exhibit healthier dietary patterns overall, reflecting a broader commitment to maintaining dietary quality throughout the day. Similar studies have demonstrated that a better-quality breakfast is associated with improved overall diet quality and better health outcomes, including reduced risk of chronic diseases36,37.

These findings highlight the importance of promoting nutrient-dense breakfasts, such as those rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins, as part of public health nutrition strategies. Encouraging such dietary habits could lead to significant improvements in overall dietary quality and health outcomes.

Following the dose-response test, we observed a significant non-linear relationship between increased intake of fiber and protein in breakfast and the overall diet quality. Similarly, in the dose-response test, we observed that higher intakes of fat (more than 12 g) in breakfast are associated with a decrease in the Mediterranean diet score and the overall diet quality. No previous study has thoroughly examined the relationship between nutrition composition in breakfast and overall diet quality in dose-response tests. A review of available studies suggests that consuming breakfast is generally associated with higher quality diets33. A recent study on 1,804 participants in Europe found that breakfast consumption was associated with higher scores on the Mediterranean diet score36. Moreover, the results of a study on 19,913 Canadian adults showed that breakfast with higher micronutrient content was associated with better diet quality34.

Fibers, especially soluble fibers such as pectin, increase satiety. Consuming foods that are rich in fiber -which is a part of the Mediterranean diet- may make people feel fuller, which can reduce the consumption of high-calorie, high-fat, and sugary foods38. Foods that are highest in dietary fiber typically have the lowest fat and sugar content, while the Mediterranean diet is not low in fat, its emphasis is on healthy fats combined with fiber-rich, minimally processed foods that are generally lower in added sugars and unhealthy fats39. Fibers increase the volume of materials in the intestine and create a more effective bowel movement. This leads to improved bowel function, better absorption of nutrients, and reduced time spent in the digestive tract40. Dietary fiber intake usually lowers the glycemic level of foods, which could help control blood sugar and possibly improve the Mediterranean diet score39. The intake of fiber per 1000 kcal in breakfast, lunch and dinner was 4.54 ± 4.47, 5.88 ± 4.82 and 7.15 ± 4.97, respectively. Considering that the total energy received from breakfast is almost 20% of this amount for the entire day, the ratio of fiber intake in breakfast to the day can justify this relationship. Based on the existing nutritional knowledge, we assumed that in the review of the Mediterranean diet pattern, among the three macronutrients of carbohydrate, protein and fat, according to these features of the pattern and the items recommended in this diet, the highest correlation between the score of the Mediterranean diet and macronutrients would be with fat. However, due to the fact that different types of fats were not separated in the present study, we could not see the relationship between this macronutrient and the Mediterranean diet score more precisely.

Gender differences in dietary intake patterns

Our findings revealed significant differences in energy intake between men and women across all three main meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner). Men consumed significantly higher energy at breakfast, lunch, and dinner compared to women. These differences are consistent with established evidence that men generally have higher energy requirements than women due to differences in body size, composition, and metabolic rate41.

Interestingly, while energy intake was significantly higher in men, the distribution of macronutrients was generally similar between sexes, with the exception of carbohydrate intake at lunch, which was higher in men. This may suggest that men tend to allocate a greater proportion of their overall energy intake to carbohydrates during lunch compared to women. Such variations could reflect differences in dietary habits, cultural factors, or meal preferences, which have been observed in other studies examining gender-based dietary behaviors42. These findings highlight the importance of considering sex-specific differences when evaluating dietary intake and nutrient distribution across meals. Although our study aimed to examine the relationship between nutrient density at breakfast and subsequent meals, understanding gender-specific patterns provides additional context for interpreting the results and tailoring nutritional recommendations to meet the unique needs of men and women.

The present study has some advantages. It is the first study to investigate the correlation between nutrition composition and nutrient density of subsequent meal and overall diet quality. We utilized the NRF9.3 index to assess the nutrient density of meals. Our study has limitations as well. Since this was a cross-sectional investigation, we could not detect causality. Although we adjusted the analyzes for potential confounders, there is still the possibility of residual confounders.

Conclusion

Based on this cross-sectional study, a non-linear link between fat and sugar intake at breakfast and also between fiber intake at breakfast and nutrient density of lunch has been found among Iranian adult population. Consuming a higher quality breakfast is associated with better overall diet quality. This finding could be interpreted as individuals who intake more amounts of fat and sugar at breakfast are more likely to have “unhealthy” choices at the subsequent meal and in addition, choosing breakfasts with higher amounts of fiber is associated with “healthier” choices throughout the day, which contributes to higher diet quality overall. Nevertheless, more studies with prospective and interventional designs are needed to confirm this finding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

US Department. of Health and Human Services (2005) The Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005.

US Food and Drug Administration. Calories count. Report of theWorking Group on Obesity. 2004. Internet: (2005). www.cfsan.fda.gov/dms/nutrcal.html(accessed 5 June.

Darmon, N. & Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: A systematic review and analysis. Nutr. Rev. 73 (10), 643–660 (2015).

O’Connor, L., Walton, J. & Flynn, A. Dietary energy density and its association with the nutritional quality of the diet of children and teenagers. J. Nutr. Sci. 2, e10 (2013).

Nicklas, T. A. et al. Impact of Breakfast Consumption on Nutritional Adequacy of the diets of young adults in Bogalusa, Louisiana: Ethnic and gender contrasts. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 98 (12), 1432–1438 (1998).

Emilien, C. H., West, R. & Hollis, J. H. The effect of the macronutrient composition of breakfast on satiety and cognitive function in undergraduate students. Eur. J. Nutr. 56 (6), 2139–2150 (2017).

Rong, S. et al. Association of skipping Breakfast with Cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73 (16), 2025–2032 (2019).

Ledikwe, J. H. et al. Low-energy-density diets are associated with high diet quality in adults in the United States. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 106 (8), 1172–1180 (2006).

Schröder, H. et al. Diet quality and lifestyle associated with free selected low-energy density diets in a representative Spanish population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 62 (10), 1194–1200 (2008).

Austin, G. L., Ogden, L. G. & Hill, J. O. Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 (4), 836–843 (2011).

Ghafarpour, M., Houshiar-Rad, A. & Kianfar, H. Te manual for household measures, cooking yields factors and edible portion of foods. Tehran 7, 213 (1999). (1999).

Sadeghi, O. et al. A case-control study on the association between adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet and breast cancer. Front. Nutr. 10, 1140014 (2023).

Widmer, R. J. et al. The Mediterranean diet, its components, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Med. 128 (3), 229–238 (2015).

Trichopoulou, A. et al. Definitions and potential health benefits of the Mediterranean diet: views from experts around the world. BMC Med. 12 (1), 112 (2014).

Fulgoni, V. L. 3rd, Keast, D. R. & Drewnowski, A. Development and validation of the nutrient-rich foods index: A tool to measure nutritional quality of foods. J. Nutr. 139 (8), 1549–1554 (2009).

Moghaddam, M. B. et al. The Iranian version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in Iran: content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl. Sci. J. 18 (8), 1073–1080 (2012).

Mendez, M. A. et al. Alternative methods of accounting for underreporting and overreporting when measuring dietary intake-obesity relations. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173 (4), 448–458 (2011).

Rampersaud, G. C. et al. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc., 105(5): (2005). 743 – 60.

Basdeki, E. D. et al. Systematic breakfast consumption of medium-quantity and high-quality food choices is Associated with Better Vascular Health in individuals with Cardiovascular Disease Risk factors. Nutrients, 15(4). (2023).

Ruiz, E. et al. Breakfast consumption in Spain: Patterns, nutrient intake and quality. Findings from the ANIBES Study, a study from the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients, 10(9). (2018).

Drewnowski, A., Rehm, C. D. & Vieux, F. Breakfast in the United States: food and nutrient intakes in relation to Diet Quality in National Health and Examination Survey 2011⁻2014. A study from the International Breakfast Research Initiative. Nutrients, 10(9). (2018).

Drewnowski, A. & Fulgoni, V. L. 3 Nutrient density: Principles and evaluation tools. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99 (5 Suppl), 1223s–8s (2014).

Medin, A. C. et al. Diet quality on days without breakfast or lunch - identifying targets to improve adolescents’ diet. Appetite 135, 123–130 (2019).

Fulgoni, V. L. 3 rd, et al., Oatmeal-containing breakfast is Associated with Better Diet Quality and Higher Intake of Key Food Groups and nutrients compared to other breakfasts in children. Nutrients, 11(5). (2019).

Peters, B. S. et al. The influence of breakfast and dairy products on dietary calcium and vitamin D intake in postpubertal adolescents and young adults. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 25 (1), 69–74 (2012).

Affinita, A. et al. Breakfast: A multidisciplinary approach. Ital. J. Pediatr. 39, 44 (2013).

Rehm, C. D. & Drewnowski, A. Replacing American Breakfast foods with Ready-To-Eat (RTE) Cereals increases consumption of Key Food groups and nutrients among US children and adults: results of an NHANES modeling study. Nutrients, 9(9). (2017).

Veronese, N. et al. Dietary fiber and health outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 107 (3), 436–444 (2018).

Moris, J. et al. A high carbohydrate-to-fiber Ratio is Associated with a low diet Quality and high fat mass in Young Women30p. 200163 (Human Nutrition & Metabolism, 2022).

Bouzid, Y. Y. et al. Lower Diet Quality Associated with subclinical gastrointestinal inflammation in Healthy United States adults. J. Nutr. 154 (4), 1449–1460 (2024).

Kranz, S., Smiciklas-Wright, H. & Francis, L. A. Diet quality, added sugar, and dietary fiber intakes in American preschoolers. Pediatr. Dent., 28(2): (2006). 164 – 71; discussion 192-8.

Brauchla, M. et al. The effect of high fiber snacks on digestive function and diet quality in a sample of school-age children. Nutr. J. 12 (1), 153 (2013).

Hopkins, L. C. et al. Breakfast consumption frequency and its relationships to overall Diet Quality, using healthy Eating Index 2010, and body Mass Index among adolescents in a low-income urban setting. Ecol. Food Nutr. 56 (4), 297–311 (2017).

Barr, S. I., DiFrancesco, L. & Fulgoni, V. L. 3rd, Consumption of breakfast and the type of breakfast consumed are positively associated with nutrient intakes and adequacy of Canadian adults. J. Nutr., 143(1): 86–92. (2013).

Leidy, H. J. et al. Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese, breakfast-skipping, late-adolescent girls. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97 (4), 677–688 (2013).

Giménez-Legarre, N. et al. Breakfast consumption and its relationship with diet quality and adherence to Mediterranean diet in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 76, 1–7 (2022).

Gwin, J. A. & Leidy, H. J. Breakfast consumption augments appetite, eating Behavior, and exploratory markers of Sleep Quality compared with skipping breakfast in healthy young adults. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2 (11), nzy074 (2018).

Waddell, I. S. & Orfila, C. Dietary fiber in the prevention of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases: from epidemiological evidence to potential molecular mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63 (27), 8752–8767 (2023).

Schwingshackl, L., Morze, J. & Hoffmann, G. Mediterranean diet and health status: Active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 177 (6), 1241–1257 (2020).

Han, X. et al. Regulation of dietary fiber on intestinal microorganisms and its effects on animal health. Anim. Nutr. 14, 356–369 (2023).

Lopez-Minguez, J., Gómez-Abellán, P. & Garaulet, M. Timing of breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Effects on obesity and metabolic risk. Nutrients 11 (11), 2624 (2019).

Bennett, E., Peters, S. A. E. & Woodward, M. Sex differences in macronutrient intake and adherence to dietary recommendations: findings from the UK Biobank. BMJ Open. 8 (4), e020017 (2018).

Funding

This study was funded by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 63422).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS-B conceived and designed the study, RN, SG, BJG, and NB contributed to the data gathering, RN analyzed the data, RN wrote the first draft of the manuscript, SS-B critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. SS-B had primary responsibility for final content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Running title

Nutrient density and diet quality.

Additional information

Declarations.

Conflict of interest.

None.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Norouziasl, R., Ghaemi, S., Ganjeh, B.J. et al. Association between breakfast nutrient density, subsequent meal quality, and overall diet quality in Iranian adults: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 4994 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88710-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88710-0