Abstract

In the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, tanycyte-neuron interactions regulate glucose homeostasis and feeding behavior. Previously, we reported that monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) 1 and 4 are localized in tanycytes, whereas MCT2 is present in arcuate nucleus neurons, including orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons (POMC). MCT1 and MCT4 inhibition impacts feeding behavior, suggesting that monocarboxylate transfer between tanycytes and neurons influences food intake. Electrophysiological studies have shown that POMC neurons respond to lactate through transport and indirect signaling using astrocytic hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1. To investigate the role of MCT2 further, we generated MCT2 knockdown rats and analyzed their feeding behavior. Female Sprague-Dawley rats received bilateral injections in the arcuate nucleus with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying a specific short hairpin RNA to inhibit MCT2 expression, thereby generating neuronal MCT2 knockdown rats. Knockdown efficiency in rat hypothalamic tissue was assessed using real-time PCR, Western Blot, and immunohistochemistry. The acute effect on feeding behavior was evaluated following 24 h of fasting, followed by 24 h of refeeding. In MCT2-knockdown rats, we observed additional inhibition of MCT1, suggesting a potential glial response to increased parenchymal lactate levels. Both macrostructure and microstructure of feeding were evaluated in MCT2-knockdown rats and compared to control AAV-injected rats. MCT2 knockdown led to a significant increase in macrostructural parameters, such as food intake and body weight. These findings underscore the importance of lactate transfer as a mechanism in tanycyte-neuron communication mediated by monocarboxylates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Substantial evidence highlights that lactate transfer from glia to neurons is essential for maintaining neuronal activity. Interestingly, this process can be bidirectional. In the hippocampus, for instance, active glutamatergic neurons do not simply receive lactate passively; rather their activity stimulates astrocytes to increase glucose uptake via the glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1)1. In the arcuate nucleus (ARC), the principal glial cells, tanycytes, have a unique role in glucose sensing and uptake. Tanycytes express not only GLUT1 but also GLUT2 and glucokinase (GK), allowing them to efficiently incorporate high glucose concentrations2. The presence of both GLUT2 and GK enables tanycytes to detect and respond dynamically to glucose levels in their environment3. We and others have shown that tanycytic lactate transfer may not only provide energy to neurons but also relay crucial information about energy status to ARC neurons4,5,6.

The ARC is near and on both sides of the basal third ventricle (3 V); it contains at least two neuronal cell populations that exert opposing actions on energy balance. Neurons in the ventromedial region of the ARC primarily produce the orexigenic neuropeptides neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AGRP) and are GABAergic in nature. Conversely, neurons in the ventrolateral ARC produce the anorexigenic peptides pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART). Some of these neurons also express vesicular glutamate transporter 2, indicating glutamatergic activity7. Additionally, the ARC contains a distinct population of neurons expressing prepronociceptin (PNOC), which provides strong inhibitory input specifically on POMC neurons, thus differing from AgRP and POMC neurons8.

Tanycytes, which line the walls and floor of the 3 V, extend long processes into the ARC and toward nearby blood vessels through specialized end feet. Immunohistochemical studies have shown that MCT2 is broadly expressed in the ARC, including in NPY and POMC neurons, as well as other neuronal types9. Additionally, MCT2 has been detected in hippocampal astrocytes and endothelial cells10. In contrast, MCT1 and MCT4 are primarily found in tanycytes and astrocytes, suggesting a metabolic communication network between these glial cells and neurons in the ARC.

Our study aims to clarify the role of lactate transfer from glia to neurons in the ARC and its impact on feeding behavior. Previous findings indicate that MCT1 inhibition in tanycytes increases food intake and body weight, suggesting a critical role of glial lactate in feeding regulation11. Similar effects were observed in MCT1 and MCT4 knockdown mice, where changes in feeding microstructure indicated reduced satiety and delayed POMC neuron activation following glucose injection into the brain6. Despite these observations, electrophysiological studies reveal that POMC neurons can respond to lactate, both through direct transport and signaling via astrocytic hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1 (HCAR1)12.

In this study, we used an adeno-associated virus (AAV) with a neuronal promoter to selectively knockdown MCT2 in neurons. This approach allowed us to specifically investigate the role of neuronal lactate uptake in acute feeding behavior. Our results demonstrate that MCT2 knockdown effectively reduced MCT2 expression, which is correlated with an increase in food intake and a significant rise in body weight in the knockdown rats. Analysis of sorted POMC and NPY neurons confirmed that both express MCT2, highlighting the importance of lactate transfer in glia-neuron communication. Together, these findings suggest that lactate acts as an intercellular messenger between tanycytes and neurons, playing a vital role in feeding behavior regulation and energy balance.

Results

High efficiency of MCT2 inhibition in ARC neurons of rats transduced with AAVshMCT2

Prior to inhibiting MCT2, we evaluated its expression in NPY and POMC neurons isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from POMC-GFP (Fig. 1) and NPY-GFP (Fig. 2) mouse models. Our results confirm MCT2 presence in both neuronal types, which have opposing roles in energy balance. Hierarchical sorting profiles are presented in Figs. 1A and 2A, with inner plots displaying the fluorescence intensity of sorted events, indicating a high enrichment of GFP-positive neurons. Notably, GFP-positive cells form a morphologically homogenous population in terms of size and complexity. We successfully isolated GFP-positive neurons from four POMC-EGFP and two NPY-EGFP transgenic mice. To assess the enrichment of POMC and NPY neurons in sorted cells, we compared mRNA levels of Pomc and Npy from hypothalamic tissue with those from FACS-isolated GFP-positive cells. mRNA samples from both the hypothalamus and sorted neurons underwent qRT-PCR analysis for Pomc and Npy, normalized to cyclophilin RNA and hypothalamic controls (Figs. 1 and 2). POMC-Sorted Cells: Pomc mRNA levels in POMC-sorted cells were 380-fold higher than in hypothalamic samples (Fig. 1B), while Npy mRNA was absent in POMC-sorted cells (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, Mct2 expression in POMC-sorted cells was 400-fold higher than in hypothalamic tissue (Fig. 1D). NPY-Sorted Cells: The expression of Npy mRNA in NPY-sorted cells was 90-fold higher than in whole hypothalamic samples (Fig. 2B), while Pomc mRNA levels were only slightly elevated compared to hypothalamic controls in these cells (Fig. 2C). Mct2 expression in NPY-sorted cells was similar to basal hypothalamic levels (Fig. 2D). These findings confirm the effective isolation of POMC and NPY neurons, and the observed expression patterns of Mct2 in both cell types support its potential role in regulating feeding behavior through distinct neuronal populations.

MCT2 expression in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and its association with POMC neurons. (A) Flow cytometry (FACS) plots showing forward scatter (FSC-A) versus side scatter (SSC-A) to illustrate the sorting of POMC-GFP neurons from transgenic and wild-type (WT) mice. Insets display the distribution of FITC intensity for gated events, confirming the enrichment of GFP-positive POMC neurons. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of gene expression for POMC, (C) NPY, and (D) MCT2 in whole hypothalamic tissue and FACS-purified POMC neurons. Data indicate higher expression of POMC and MCT2 in sorted POMC neurons compared to whole hypothalamic samples, while NPY expression remains negligible in POMC-purified cells.

Expression of MCT2 in NPY neurons of the arcuate nucleus (ARC). (A) Flow cytometry (FACS) plots showing forward scatter (FSC-A) versus side scatter (SSC-A) to illustrate the sorting of NPY-GFP neurons from transgenic and wild-type (WT) mice. Insets display the distribution of FITC intensity for gated events, confirming the enrichment of GFP-positive NPY neurons. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showing the expression levels of NPY, (C) POMC, and (D) MCT2 in whole hypothalamic tissue and FACS-purified NPY neurons. Results indicate a significant enrichment of NPY and MCT2 expression in sorted NPY neurons compared to hypothalamic samples, while POMC expression is minimal in NPY-purified cells.

To generate MCT2 knockdown rats in the ARC without impacting cell viability, we used a high-titer AAV and a control AAV with similar properties. These AAVs were injected bilaterally, and knockdown efficiency was evaluated by real-time PCR and Western blotting 15 days post-transduction (Fig. 3A). Rats transduced with AAV2-H1-sh(MCT2)-Syn-tdTOMATO (AAVshMCT2) showed over 60% reduction in MCT2 mRNA compared to those transduced with AAV2-H1-Syn-tdTOMATO (AAVcontrol).

Robust inhibition of MCT2 expression in female rats transduced with AAVshMCT2 compared to control AAV. (A) Schematic of the experimental protocol showing the AAV constructs used: AAV-SYN-TdTOMATO as the control and AAV-shMCT2-SYN-TdTOMATO for MCT2 knockdown. Injection coordinates were as follows: anterior-posterior (AP): −3.14 mm, dorsal-ventral (DV): −9.8 mm, and left-right (LR): ± 0.30 mm. (B-E) Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of MCT2, MCT1, MCT4, and HCAR1 mRNA levels in the hypothalami of rats transduced with control AAV (open bars) or AAVshMCT2 (closed bars) 2 weeks post-injection. Each experimental group processed in a different experiment was assigned a unique color, and three experiments were performed. (F) Western blot analysis showing MCT2 protein levels with actin as the loading control. (G) Semi-quantitative densitometric analysis of MCT2 protein levels normalized to actin, using three animals per condition. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test).

Since mRNA quantification was performed on hypothalamic tissue dissected from the ARC, where glial cells also express other lactate transporters (MCT1 and MCT4)13and the lactate receptor HCAR112, we investigated whether MCT2 knockdown affected the expression of these related transporters. As shown in Fig. 3C-D, MCT1 expression, but not MCT4, was reduced despite the short hairpin RNA being specific to MCT2. This finding suggests that elevated parenchymal lactate levels may directly or indirectly downregulate the high-affinity transporter MCT1 without impacting the low-affinity transporter MCT4 (Fig. 3E). We observed two groups of animals after MCT2 inhibition: more inhibited (blue) and less inhibited (green). A similar trend was seen in HCAR1, though without significant differences (Fig. 3B-E; Supplementary Table 2). This variability may stem from differences in injection site accuracy or the estrous cycle of the unsynchronized female rats. Protein analysis by Western blot of samples from the ARC revealed that the two bands obtained from AAVshMCT2-transduced animals were of lower intensity than those from the control AAV (Fig. 3F). The 53 kDa bands were normalized to β-actin and quantified, showing significant differences (Fig. 3G). The specificity of the antibody MCT2 was validated using testis as control tissue (Supplementary Fig. 2)14.

We performed a localization analysis of the tdTOMATO reporter carried by AAVshMCT2 to confirm the accuracy of the AAV injection site. As shown in Fig. 4A, the injection precisely targeted the base of the ARC near the 3 V (Fig. 4B1-B2). This region is closely associated with vimentin-positive tanycyte processes (Fig. 4D1-D2). Under these conditions, MCT2 expression appeared low (Fig. 4C1-E2). In Fig. 4B2-C2, arrowheads indicate neurons transduced with tdTOMATO that lack MCT2 immunoreactivity, while arrows indicate neurons transduced with tdTOMATO that exhibit MCT2 immunoreactivity. In Fig. 4C2 and D2, yellow arrowheads point to possible endothelial cells that are also vimentin-positive, and the orange arrow highlights a possible astrocyte that is vimentin-negative but MCT2-positive, as previously reported10. Other brain areas located in similar bregma levels, such as the lateral hypothalamic area, the hippocampus, or the amygdala, were not transduced (data not shown).

AAVshMCT2 effectively targets the ARC and reduces MCT2 expression. (A-B2) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the localization of the tdTOMATO reporter (red) to confirm transduction of cells in the ARC. (C1-C2) Immunolocalization of MCT2 (green) to assess expression levels. (D1-D2) Immunolocalization of vimentin (white) to visualize tanycyte processes. (E1) Merged images illustrating the spatial relationship between tdTOMATO-expressing cells, MCT2, and tanycyte processes. (E2) High-magnification view of E1 highlighting the close association between tanycyte processes and MCT2-expressing neurons. White arrowheads indicate neurons transduced with tdTOMATO that lack MCT2 immunoreactivity. White arrows indicate neurons transduced with tdTOMATO that exhibit MCT2 immunoreactivity. Yellow arrowheads point to possible endothelial cells that are also vimentin-positive. The orange arrow indicates an astrocyte-like cell that is vimentin-negative but MCT2-positive. ME: median eminence; 3 V: third ventricle.

To verify that this reduced immunoreactivity was due to decreased MCT2 expression, we performed a unilateral injection. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the side injected with AAVshMCT2 exhibited significantly lower MCT2 levels (Fig. 5A-B and D-E), with decreased general localization of MCT2, both in the membrane of somas and neuronal processes, which becomes more evident when looking at the 3D images (Fig. 5C and F).

AAVshMCT2 reduces MCT2 immunoreactivity in the ARC. Immunohistochemistry analysis of MCT2 (green) with DAPI (blue) as a nuclear marker in rats transduced with (A-C) control AAV and (D-F) AAVshMCT2. (C and F) 3-D views reconstructed from 15 confocal z-planes spanning a total of 10 μm, demonstrating the reduction of MCT2 signal in AAVshMCT2-injected rats compared to control. The 3D projection was generated using Zen Software Version 8.0, which includes image acquisition, processing, and a module for 3D visualization and analysis. The images were obtained using a ZEISS LSM780 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Germany). More information about the software can be found at: https://www.micro-shop.zeiss.com/es/uy/softwarefinder/software-categories/zenblack/.

MCT2 inhibition in ARC neurons affects acute feeding behavior

We further evaluated the impact of MCT2 inhibition in the ARC on glucose homeostasis, food intake, and body weight, following the protocol outlined in Fig. 6A. Blood glucose concentration was measured to confirm that any observed changes in food intake were not due to systemic glycemic alterations. As shown in Fig. 6B (red bar), no significant variations in blood glucose concentration were detected during fasting and refeeding, with average values within the ranges for hypoglycemia and normoglycemia.

Knockdown of MCT2 increases food intake and body weight in female rats. (A) Experimental protocol depicting bilateral AAV injections (control or AAVshMCT2) into the ARC of adult female rats. After 12 days, rats underwent 24 h of fasting followed by 24 h of refeeding. Glycemia, food intake, and body weight were measured after fasting and at the end of the refeeding period. (B) Glycemia measured in rats transduced with AAV control (open bars) or AAVshMCT2 (closed bars) after fasting and refeeding. (C) Food intake over 24 h post-refeeding, expressed as g/200 g body weight. (D) Percentage change in body weight 24 h post-refeeding. (E) Cumulative meal frequency during the 24-h refeeding period. (F) Meal frequency assessed every 3 h during the refeeding period. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test).

Next, we assessed food intake using cages equipped to record feeding events and duration. The total food consumed over a 24-hour refeeding period following a 24-hour fast was measured and normalized per 200 g of body weight, accounting for slight initial weight differences among animals. As shown in Fig. 6C, MCT2 inhibition led to a significant increase in cumulative food intake, with knockdown animals (red bar) consuming, on average, 3.4 g more than controls (white bar) during the refeeding period. Body weight also increased significantly in knockdown animals by 2.8% compared to controls (Fig. 6D, red vs. white bars). To further analyze feeding patterns, we examined the occurrence and frequency of feeding events during both the dark and light phases. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in the total number of feeding events over 24 h (Fig. 6E). When feeding events were plotted every 3 h, knockdown animals exhibited a less pronounced decline in feeding frequency than controls, though differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 6F).

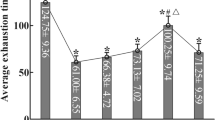

MCT2 knockdown rats did not show significant differences in first meal duration or latency compared to controls, although they displayed a slight anticipation to eat, suggesting that MCT2 inhibition might influence responses post-fasting (Fig. 7A-B). No significant differences were observed in mean meal duration (Fig. 7C) or inter-meal interval (Fig. 7D), which was associated with decreased satiety behavior. Notably, MCT2 knockdown rats showed increases in specific feeding behaviors, such as feeding rate and meal size (Fig. 7E-F), which correlated with the observed significant increase in overall food intake.

Microstructure of ingestion in female rats with MCT2 knockdown. Quantification of the following feeding microstructure parameters: (A) first meal duration (min), (B) latency to first meal (min), (C) average meal duration (min), (D) average interval duration between meals (min), (E) meal size (g), and (F) feeding rate (mg/min). Analysis of the feeding rate, calculated as the total food consumed divided by the total meal duration, indicated that female rats with MCT2 knockdown exhibited an increased eating rate, correlating with a significant increase in overall food intake.

These findings suggest that MCT2 inhibition in the ARC not only influences cumulative food intake and body weight but also alters specific aspects of feeding behavior, hinting at a potential role for MCT2 in modulating satiation signals and post-fasting responses. Together, these results provide a foundation for exploring the broader implications of MCT2-mediated lactate signaling in energy homeostasis.

Discussion

Understanding the regulation of food intake is inherently complex, as it is influenced by both homeostatic and hedonic control mechanisms. Many of these regulatory pathways are redundant due to their critical role in survival, which complicates both their study and the interpretation of findings. In this study, we inhibited MCT2, a monocarboxylate transporter widely expressed in diverse neuronal populations of the ARC and observed significant changes in feeding behavior. The marked increase in food intake and consequent weight gain observed in MCT2 knockdown rats likely results from disrupted signaling in ARC neurons projecting to other key hypothalamic centers, such as the paraventricular, dorsomedial, ventromedial, and lateral hypothalamic nuclei15. These nuclei project to additional hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic regions, which amplify the response and impact both energy intake and expenditure16,17,18. Our results are consistent with previous findings that MCT1 and MCT4 inhibition in hypothalamic glia also alters feeding behavior in rats and mice11,13,19. Collectively, these findings highlight the importance of glial-to-neuron lactate transfer in the regulation of feeding, suggesting that disruption of this metabolic coupling leads to altered food intake.

Although MCT1 is broadly expressed across various cell types throughout the nervous system, MCT2 is predominantly localized in neurons. The coordinated kinetics between neuronal MCT2 and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1, along with astrocytic MCT1/4 and LDH5, support a model of glial lactate production and neuronal consumption20,21,22,23. Immunohistochemical analysis of MCT2 in the ARC revealed its presence in approximately 90% of orexigenic neurons and 60% of anorexigenic neurons, as well as other neuronal populations within the ARC9. In our study, we inhibited MCT2 across this diverse neuronal spectrum using an AAV vector with a widely expressed neuronal promoter. While the ARC contains both orexigenic and anorexigenic neurons, its complete ablation induces hyperphagia, underscoring its role as a satiety center, particularly in conjunction with the ventromedial nucleus. Consequently, it is not surprising that MCT2 inhibition could lead to increased food intake, supporting the hypothesis that lactate released by neighboring glial cells during feeding is detected by neurons as a satiety signal—a process that may be disrupted in MCT2 knockdown rats.

Our results align with prior studies6 demonstrating that selective MCT2 inhibition in POMC neurons increases food intake without significantly affecting body weight. This suggests that the broader MCT2 inhibition achieved here may also impact MCT2-expressing orexigenic neurons. It is plausible that lactate, acting via MCT2, normally exerts an inhibitory effect on orexigenic neurons, and that MCT2 inhibition relieves this suppression, resulting in increased food intake, as illustrated in Fig. 8. However, further studies are needed to explore the potential inhibitory effects of lactate on NPY/AgRP or PNOC neurons, which are abundant in the ARC. Substantial evidence supports the role of lactate transfer from glial cells to neurons in regulating food intake, including studies demonstrating that MCT1 knockdown in tanycytes of male rats leads to increased food intake and body weight11. While our findings in female rats are consistent with these results, there were some differences in feeding microstructure. For instance, MCT1 knockdown rats exhibited increased intermeal intervals, an indicator of satiety, whereas we did not observe this effect in MCT2 knockdown rats. Instead, MCT2 knockdown rats showed increased meal size and feeding rate, suggesting a potential disruption in satiation rather than satiety.

Schematic representation summarizing the results of this manuscript. Our results suggest that the potential exchange of lactate between tanycytes and neurons in the arcuate nucleus may serve as a source of metabolic energy as well as a signaling mechanism. A reduction in MCT2 expression correlates with increased food intake and significant weight gain in rats. Impaired lactate uptake in POMC and NPY neurons could affect POMC activation and reduce NPY inhibition, suggesting that lactate plays a role in regulating feeding behavior and energy balance, with potential implications for the treatment of metabolic disorders.

Our real-time PCR data further showed that MCT2 knockdown in female rats significantly reduced MCT1 mRNA expression. This reduction is unlikely to result from nonspecific shRNA binding, as the shRNA sequence does not target MCT1, and MCT1 is not neuronally expressed9,24. Interestingly, MCT4 expression, which mediates lactate efflux, was unaffected, suggesting a selective downregulation of MCT1 to possibly retain pyruvate within cells, critical for maintaining glycolytic flux and NAD + regeneration24. The specific mechanisms by which MCT2 inhibition or increased parenchymal lactate downregulates glial MCT1 expression remain to be investigated.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that MCT2 inhibition in ARC neurons significantly impacts feeding behavior in rats, with knockdown animals exhibiting increased food intake and body weight. This supports the role of monocarboxylate-mediated tanycyte-neuron metabolic coupling in the regulation of feeding behavior. These results align with recent long-term studies showing that specific MCT2 inhibition in POMC neurons also increases food intake and suggests that MCT2 activity might influence both orexigenic and anorexigenic pathways within the ARC6. Furthermore, emerging studies on tanycyte activation via optogenetics in rodents have shown that tanycytes can modulate ARC neuronal activity and alter feeding behavior4. This function may involve tanycyte access to circulating hormones and nutrients, enabling them to influence energy balance and neuronal signaling within the ARC5,11,25. Tanycytes are also known to produce 2-arachidonoylglycerol, which modulates ARC neuronal activity26. These findings suggest that lactate release by tanycytes may be one of several metabolic signals modulating ARC neurons.

Future studies should investigate the precise mechanisms underlying MCT2-mediated lactate signaling and its role in orexigenic and anorexigenic pathways. Understanding how MCT2 and other monocarboxylate transporters integrate with tanycyte function may reveal new insights into the cellular processes that regulate feeding behavior and energy homeostasis. Our study provides novel evidence that tanycyte-neuron lactate transfer plays a significant role in these processes, opening new avenues for therapeutic targets aimed at modulating feeding behavior and metabolic balance.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animal experiments were performed in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). All experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research of Chile (CONICYT; protocol code 1221508, approved on 03/01/2022). Additionally, it was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Biological Sciences and the Committee on Ethics, Care, and Use of Animals at the University of Concepción, Chile, (permit number 2010101 A, in April 2024). Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (120–280 g), housed on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, had ad libitum access to a standard rodent diet (Lab Diet, 5P00 Prolab RMH 3000, Purina Mills, St. Louis, MO, USA) and tap water, except during periods of induced fasting. We used a total of 40 female rats, with the numbers shown in each graph.

AAV vectors

Viral vectors were obtained from SignaGen Laboratories (Rockville, MD, USA). To inhibit MCT2 expression in vivo, AAV2-H1-sh(MCT2)-Syn-tdTOMATO (1 × 1013 GC/mL, Cat #SL100874, SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, MD 20850, USA) expressing the shRNA for MCT2 under the synapsin promoter, which restricts transgene expression to neurons only, and the tdTomato reporter gene was used. The AAV2-H1-Syn-tdTOMATO (1 × 1013 GC/mL, Cat #SL100896, SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, MD 20850, USA) was used as a control.

Stereotaxic surgery

Stereotaxic surgery was performed to administer AAV-shMCT2-SYN-Tdtomato (inhibitory) and AAV-SYN-Tdtomato (control) (SignaGen Laboratories; 20850) into the rat hypothalamus. Six-week-old rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (1 mg/mL) delivered by a veterinary vaporizer (EasyFill Model R540IE, RWD Life Science Co., Sugar Land, TX, USA) and fixed on a stereotaxic apparatus (Model 68528 RWD Life Science Co.) with auditory bars that preserve the tympanic membrane27. After exposing the skull, two small holes were drilled for injection according to the coordinates of bregma: anterior-posterior: −3.14 mm, dorsal-ventral: −9.8 mm, left-right: ± 0.30 mm. Rats were injected as described in Fig. 1A using a Hamilton 7000 Neuros syringe (Model 7001 KH, Volume: 1uL, 65458-01, Hamilton Company, Bellefonte, PA, USA) to infuse 250 nL per ARC of the AAV control or inhibitory at a rate of 50 nL/min. For postoperative care, rats were injected intraperitoneally with 100 µL of tramadol (5 mg/kg).

FACS-based isolation of hypothalamic POMC-EGFP and NPY-EGFP neurons

Mice, both control and transgenic, that were fed ad libitum were euthanized, and the medial basal hypothalamus was micro-dissected on a cold surface with the tissue being maintained in cold HBSS. The dissected tissue was then enzymatically digested using a papain/trypsin enzyme mix (50 U/ml / 0.12%, Sigma, USA) for 10 min at 37ºC. Mechanical dissociation followed, initially using a p1000 plastic tip. The resulting cell suspension was incubated for 5 min at 37 °C and further mechanically disaggregated with a p200 plastic tip. The suspension was passed through a 70 μm cell strainer and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended in DPBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA to proceed with FACS analysis. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) was carried out using an Influx cell sorter (FACS Aria-III, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), where GFP fluorescence was detected using the FITC channel. Cells were gated based on forward scatter (FSC) vs. side scatter (SSC) to assess size and granularity, followed by the exclusion of doublets. GFP-positive cells were defined by FITC intensity values greater than 103 (relative to wild-type controls). Sorting was executed in purity mode into Eppendorf tubes containing lysis buffer from the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For conventional PCR, total RNA was extracted, and cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScriptTM cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Control reactions without reverse transcriptase were included to monitor DNA contamination. Amplification was conducted using 12.5 µL of the cDNA mixture, consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 1.6 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM dNTPs, 0.04 U Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and 0.4 µM primers. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 4 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 5 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were resolved by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide staining.

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Two weeks after AAV injection, total RNA was obtained from the basal hypothalamus, homogenizing the samples in 500 µL Trizol® for 10 min and incubating them for 5 min at room temperature. Then, the samples were treated with 200 µL chloroform, shaken for 15 s, and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C to recover the aqueous phase, which was incubated in 300 µL isopropanol for 10 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 ×g for 15 min each time. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 20 µL RNase-free water and quantified by measuring its absorbance at 260 nm and purity according to the 260/280 ratio. The samples were treated with DNase I (Thermo Scientific, V. A. Graiciuno 8, Vilnius, LT-02241 Lithuania), and cDNA synthesis was performed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit following the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems™, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 2 µg of the total RNA. Controls for the presence of genomic DNA were treated using the same protocol but without adding reverse transcriptase enzyme to the mixture.

Real-time PCR

Amplification of cDNA was performed using the SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR®Green Supermix kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, California, USA) in a final volume of 10 µL, containing 1 µL of cDNA, 5 µL of master mix, and 500 nM of the respective primers (Supplementary Table 1). Samples were initially denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and then 38 cycles of 95 °C for 38 s, 55 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min were performed using an Mx3000P thermal cycler (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). Quantification was performed by comparing the number of cycles required to amplify each gene over the threshold cycle (Ct), relative to the housekeeping control gene, β-actin, using the ΔΔCt method. Primers were previously validated and used accordingly11,13. Table 1 with primers is included in the supplementary material.

Immunofluorescence

Two weeks after AAV injection, the brains were collected and fixed in 4% PFA by immersion for 48 h. After fixation, the PFA was removed, and the brains were cut into 50 μm coronal sections with a vibratome (Campden Instruments, 5100mz; Loughborough, Leics, England) and processed by free-floating. Tissues were washed in Tris phosphate buffer (84 mM Na2HPO4, 35 mM KH2PO4, 120 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.8) three times 10 min each and blocked with an ammonium chloride (50 mM) solution for 30 min. Tissues were then incubated overnight at room temperature with the following primary antibodies dissolved in Tris phosphate with 1% bovine serum albumin (Gibco, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and 0.2% Triton X-100: rabbit anti-MCT2 (1:200, Alomone Labs, JBP, Jerusalem, Israel, Cat# AMT-012) and chicken anti-vimentin (1:5000, Abcam, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab24525), as previously described in9,28. The slices were washed five times with the Tris phosphate buffer and incubated for 2 h with the following secondary antibodies: Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-rabbit and Alexa-Fluor 647 anti-chicken (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA, Cat# 111545003 and Cat# 703605155 respectively) and DAPI nuclear staining (1:800, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-3598). Finally, the slices were mounted with Dako Fluorescent Mounting Medium (Dako Cytomation, Campintene, CA, USA). The samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy (Confocal Spectral, model LSM780 NLO Zeiss, Centro de Microscopía Avanzada, CMA-Bio Bio).

Western blot analysis

Total protein extracts were obtained from the basal hypothalamus. The samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer supplemented with a complete protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany) and sonicated three times on ice at 300 W for 10s (Sonics & Material INC, VCF1, CT, USA). Concentrations of the lysed proteins were measured by the Bradford technique, equaled to 50 µg and incubated for 2 min at 95 °C with a protein loading buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) in the presence of 0.1 M DTT. Proteins were separated with 10% acrylamide denaturing gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with samples seeded next to the pre-stained standard (Precision Plus Protein Standards, Kaleidoscope, Cat# 1610375, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), then separated at 80 V in a solution containing 250 mM glycine, 25 mM Tris, and 0.1% SDS. Then proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (0.45 μm pore, Merck Millipore, Tullagreen, Carrigtwohill, Ireland) in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol) for 2 h at 250 mA using Ponceau red to confirm transfer (P3504-10G, Sigma Aldrich). Membranes were washed with TBS-Tween (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 0.05% Tween20) and blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS-Tween for 1 h. After incubation with the primary antibody, rabbit anti-MCT2 (1:1000, Bioss, Cat# bs-3995R) and peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-β-actin (1:10000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-47778 HRP) dissolved in 5% skim milk TBS-Tween at 4 °C overnight, membranes were incubated with the secondary peroxidase-conjugated antibody anti-rabbit (1:5000, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., PA, USA, Cat# 111035144) at room temperature for 2 h. After secondary antibody incubation, the membranes were washed with TBS-Tween and exposed to the chemiluminescent liquids Western Lightning Plus-ECL (Amersham™, ECL™ Prime Western Blotting Detection Regeants, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) on the luminescent chemo and fluorescence imaging equipment (Clinx Science Instruments Co., Ltd, Model ChemiScope 3300). Densitometric analysis was performed on Quantity One® software using β-actin as loading control.

Food intake monitoring and feeding behavior analysis

At 2 weeks following AAV injection, rats were subject to fasting for 24 h and refeeding for another 24 h (07:00 p.m.–07:00 p.m.) as described in Fig. 4A. All rats were previously habituated to the individual cages for 1 week before the experiments were initiated. Rats’ daily feeding behavior was measured for all refeeding periods using a computerized data acquisition system (VitalView, Respironics, Inc., Murraysville, PA, USA), which registers frequency and time of permanency in the feeder. Body weight was measured at the end of the fasting and refeeding periods. Satiety parameters, including mean meal duration (events/min), mean meal size (g/events), eating rate (g/min), latency of the first meal (min), first meal duration (min), and meal interval duration (min), were calculated as previously described13,15.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0 Software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All analyzed values were calculated as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Significant differences between two groups were determined using the Student’s t-test, and one-way ANOVA was used for more than two group comparisons, as indicated otherwise. Statistical significance was defined when p < 0.05.

Data availability

Data Availability Statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additionally, data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (M.A. Garcia-Robles).

References

Karin Pierre, P. J. M. & Luc Pellerin MCT2 is a Major Neuronal Monocarboxylate Transporter in the Adult Mouse Brain22p. 586–595 (SAGE journals, 2002). 5.

Millan, C. et al. Glial glucokinase expression in adult and post-natal development of the hypothalamic region. ASN Neuro. 2 (3), e00035 (2010).

Joost, H. G. & Thorens, B. The extended GLUT-family of sugar/polyol transport facilitators: nomenclature, sequence characteristics, and potential function of its novel members (review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 18 (4), 247–256 (2001).

Bolborea, M. et al. Hypothalamic tanycytes generate acute hyperphagia through activation of the arcuate neuronal network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117 (25), 14473–14481 (2020).

Garcia-Robles, M. A. et al. Hypothalamic ependymal-glial cells express the glucose transporter GLUT2, a protein involved in glucose sensing. J. Neurochem. 86 (3), 709–724 (2003).

Lhomme, T. et al. Tanycytic networks mediate energy balance by feeding lactate to glucose-insensitive POMC neurons. J. Clin. Investig., 131(18):e140521. (2021).

Qiu, J. et al. Deletion of Stim1 in Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus Kiss1 neurons potentiates Synchronous GCaMP activity and protects against Diet-Induced obesity. J. Neurosci. 41 (47), 9688–9701 (2021).

Jais, A. et al. PNOC(ARC) neurons promote hyperphagia and obesity upon High-Fat-Diet feeding. Neuron 106 (6), 1009–1025e10 (2020).

Cortes-Campos, C. et al. MCT2 expression and lactate influx in anorexigenic and orexigenic neurons of the arcuate nucleus. PloS One. 8 (4), e62532 (2013).

Pang, R. et al. The distribution and density of monocarboxylate transporter 2 in cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum of wild-type mice. J. Anat. 236 (2), 370–377 (2020).

Elizondo-Vega, R. et al. Inhibition of hypothalamic MCT1 expression increases food intake and alters orexigenic and anorexigenic neuropeptide expression. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 1–13 (2016).

Órdenes, P. et al. Lactate activates hypothalamic POMC neurons by intercellular signaling. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 21644 (2021).

Elizondo-Vega, R. et al. Inhibition of hypothalamic MCT4 and MCT1–MCT4 expressions affects Food Intake and alters Orexigenic and Anorexigenic Neuropeptide expressions. Mol. Neurobiol. 57 (2), 896–909 (2020).

Kishimoto, A. et al. Immunohistochemical localization of GLUT3, MCT1, and MCT2 in the testes of mice and rats: the use of different energy sources in spermatogenesis. Biomed. Res. 36 (4), 225–234 (2015).

Elizondo-Vega, R. et al. The role of tanycytes in hypothalamic glucosensing. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 19 (7), 1471–1482 (2015).

Bouret, S. G. Development of hypothalamic circuits that control food intake and energy balance. In Appetite Food Intake: Central Control; ISBN 978-1-4987-2316-9. pp. 135–154. (2017).

Bouyer, K. & Simerly, R. B. Neonatal leptin exposure specifies innervation of presympathetic hypothalamic neurons and improves the metabolic status of leptin-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 33 (2), 840–851 (2013).

Waterson, M. J. & Horvath, T. L. Neuronal regulation of Energy Homeostasis: beyond the Hypothalamus and Feeding. Cell. Metab. 22 (6), 962–970 (2015).

Prevot, V. Glial control of neuronal function. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 195 (2022).

Laughton, J. et al. Differential messenger RNA distribution of lactate dehydrogenase LDH-1 and LDH-5 isoforms in the rat brain. Neuroscience 96 (3), 619–625 (2000).

Debernardi, R. et al. Cell-specific expression pattern of monocarboxylate transporters in astrocytes and neurons observed in different mouse brain cortical cell cultures. J. Neurosci. Res. 73 (2), 141–155 (2003).

Pellerin, L., Halestrap, A. P. & Pierre, K. Cellular and subcellular distribution of monocarboxylate transporters in cultured brain cells and in the adult brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 79 (1–2), 55–64 (2005).

Mächler, P. et al. In vivo evidence for a lactate gradient from astrocytes to neurons. Cell Metabol. 23 (1), 94–102 (2016).

Cortés-Campos, C. et al. MCT expression and lactate influx/efflux in tanycytes involved in glia-neuron metabolic interaction. PloS One. 6 (1), e16411 (2011).

Guerra, M. et al. Cell organization of the rat pars tuberalis. Evidence for open communication between pars tuberalis cells, cerebrospinal fluid and tanycytes. Cell Tissue Res. 339, 359–381 (2010).

Palma-Chavez, A. et al. Glucose increase DAGLα levels in tanycytes and its inhibition alters orexigenic and anorexigenic neuropeptides expression in response to glucose. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 647 (2019).

Barahona, M. J. et al. Tympanic membrane rupture during stereotaxic surgery disturbs the normal feeding behavior in rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 14, 591204 (2020).

Barahona, M. et al. GLUT2 expression by glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive tanycytes is required for promoting feeding-response to fasting. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17717 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Centro de Estudios para la Vida (CREAV), especially Veterinarian Carolina Benitez and Dr. Market Heitzer, for their helpful discussions and editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT) under grant numbers 1221508 (MA.G-R.), 1211261 (P.V.B.), and 1241214 (R.E.-V.), as well as by the grant ICM-Economía P09-022-F from the Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencias de Valparaíso (MA.G-R.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: The experiments were performed at the Department of Cell Biology at the University of Concepcion MA.G-R, E.T-S and R.E-V conceived the experiments; designed the experiments; A.C, S.L, V.S, D.C, A.V and P.O performed the experiments; A.C, S.L, AV analyzed the data; MA.G-R, PV.B, J.A-I and R.E-V contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; wrote the paper, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coca, A., López, S., Órdenes, P. et al. Knocking down the neuronal lactate transporter MCT2 in the arcuate nucleus of female rats increases food intake and body weight. Sci Rep 15, 7497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90513-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90513-2