Abstract

A series of amide-based mono and dimeric pyridinium bromides were synthesized using conventional and microwave-assisted solvent-free methods. The quaternization reactions of m-xylene dibromide and 4-nitrobenzylbromide with amide-based substituted pyridine proceeded efficiently, whereas 1,6-dibromohexane required reflux conditions. A comparative analysis of the solvent-free microwave-assisted reactions revealed a significant reduction in reaction time (up to 20-fold) and increased yields, accompanied by simplified work-up procedures. Notably, these reactions exhibited 100% atom economy and generated no environmental waste. The cytotoxic effects of the synthesized compounds were assessed using the MTT assay, nuclear staining, and Real Time-Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) on the lung cancer cell line (A-549).Molecular docking studies were performed to investigate the interaction and binding of B-Raf kinase inhibitors with the amide-based mono and dimeric pyridinium bromides. Furthermore, the toxicity of the drug molecules was assessed using the BOILED-Egg plot at the central nervous system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

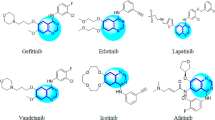

Cancer is one of the deadliest diseases that affects people of all ages, genders, and socioeconomic backgrounds. It poses a significant threat to human life and is the second leading cause of death worldwide. This deadly disease is characterized by uncontrolled growth and multiplication of cancer cells, which can affect almost any organ in the human body. Biocompatible ionic liquids, comprising alkyl/aryl-substituted amino acids as anions and choline as a cation, have been investigated for cytotoxic and antitumor studies against HeLa cells. Researchers have also found that these ionic liquids exhibit lower hypersensitivity reactions in vitro on THP-1 cells compared to Taxol1. Furthermore, imidazolium chlorides with longer, flexible alkyl chains have been screened for cytotoxicity against 60 human cancer cell lines, revealing lower toxicity and apoptosis induction in A431 cancer cells2. Organic anions derived from betulinic acid, paired with alkyl-chain-linked phosphonium salts, have demonstrated higher selectivity against lung, breast, and liver cancer cell lines3. Hydrazone-linked dimeric pyridinium cations with various inorganic anions have been synthesized and evaluated for cytotoxic properties against colon and breast cancer cell lines using the MTT assay. The IC50 values of these hydrazone-linked salts ranged from 59 to 64 μM in the tested cell lines4. Ammonium/imidazolium cations with different counter anions have shown low toxicity in HEK cell lines while exhibiting higher cytotoxic responses against T98G brain cancer cell lines5. Simple and higher alkyl-substituted imidazolium / tetraethyl ammonium cations, as well as different alkyl-connected phosphonium cations paired with ampicillin anions, have been investigated for cytotoxic responses in colon, breast, liver, and osteosarcoma cell lines. The IC50 values in these tested cancer cell lines ranged from 1.240 to 0.146 μM6. Hitesh et al. studied the cytotoxic responses of synthesized substituted benzodioxole its derivatives and benzodioxole against HeLa cancer cell lines, finding that substituted benzodioxolium cations with acetate/triflate counter anions exhibited appreciable cytotoxic responses7. Similarly, Alkyl-substituted and phenyl acetamide-linked pyridinium cations with BF4−/PF6−/CF3COO−counter anions have shown only 50% cytotoxic responses against A549 and H1229 lung cancer cell lines8. Our recent reports have described the preparation and cytotoxic properties of simple and substituted imidazolium and pyridinium salts9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Amino-substituted 3-pyrimidinyl azaindole derivatives have demonstrated potent in vivo responses in a mouse mammary triple-negative breast cancer model16. 3-Pyrimidinyl azaindole derivatives have significantly inhibited tumor growth in two mice xenograft cancer models17. Pyridopyrimidine urea derivatives have acted as effective drug molecules, reducing proliferation in MCE-7 and MDA-MB-468 cell lines18. Chiral cyclic peptides have shown potential anticancer responses against breast MDA-MB 231 tumor cells, outperforming linear chiral peptides19. 3(Phenylethynyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-amine derivatives have exhibited excellent anticancer responses in triple-negative breast cancer models, both in vitro and in vivo, although these drug molecules have considerable toxicity20. Tamoxifen and substituted tamoxifen derivatives have demonstrated higher potency in antiproliferative assays against MCF-7 human breast cancer cell lines, with lower cytotoxicity responses21. Based on the available literature, we aim to prepare amide-based mono and dimeric pyridinium bromides using conventional and solvent-free greener methods. We intend to examine the atom economy, environmental factors, molecular docking simulations, and cytotoxicity properties of our amide-based mono and dimeric pyridinium bromides.

Results and discussion

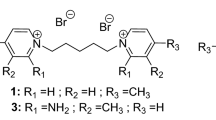

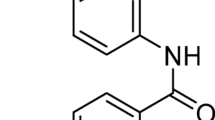

Novel substituted amides and amide-based mono- and dimeric pyridinium bromides were synthesized using conventional and solvent-free silica-supported approaches. To prepare 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1,3-amino pyridineand p-tolylchloride were stirred together in the presence of anhydrous K2CO3 in CH3CN at ice-cold conditions for 5 min. with an encouraging yield of 80% after purification (Scheme 1).

To prepare 1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide) 2, 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 was reacted with 1,6-dibromohexane at room temperature for 2 h. However, no significant progress was observed. Therefore, we attempted refluxing for 15 min., which yielded 86% of the desired product after purification (Scheme 2).

Due to environmental concerns, we sought to avoid volatile organic solvents. Instead, we employed a silica-supported, solvent-free approach using microwave irradiation to synthesize 1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide) 2. A mixture of 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 and 1,6-dibromohexane was combined with 5 g of 100–120 mesh silica gel and uniformly mixed by manual grinding using a mortar and pestle. Five portions of the grinded reaction mixture were taken for optimization. We observed that the solvent-free, silica-supported microwave reaction was completed within 7 min., yielding 96% of the desired product after purification (Scheme 2). We also synthesized 1,1′-(1,3-phenylenebis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 3 by reacting 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 with m-xylene dibromide in CH3CN at room temperature for 60 min., affording 88% yield. The same target molecule was obtained within 4 min. under refluxing conditions in CH3CN, yielding 90% (Scheme 3).

1,1′-(1,3-phenylenebis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 3 was synthesized using a silica-supported, solvent-free approach under microwave irradiation. A mixture of 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 and m-xylene dibromide was combined with 5 g of 100–120 mesh silica gel and uniformly mixed by manual grinding using a mortar and pestle. The solvent-free, silica-supported microwave reaction was completed within 2 min., yielding 95% of the desired product after purification (Scheme 3). 1,1′-((2,4,6-Trimethyl-1,3-phenylene)bis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4 was prepared by reacting 2,4-bis(chloromethyl)-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 at room temperature for 120 min., affording 87% yield. The same target molecule was obtained under refluxing conditions within 12 min., yielding 92% (Scheme 4).

1,1′-((2,4,6-Trimethyl-1,3-phenylene)bis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4 was also synthesized using a solvent-free, silica-supported microwave reaction, which was completed within 8 min. and yielded 95% of the desired product after purification (Scheme 4). 3-(4-Methylbenzamido)-1-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 5 was prepared by reacting 4-nitrobenzyl bromide with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 at room temperature for 60 min., affording 85% yield. The same target molecule was obtained under refluxing conditions within 8 min., yielding 90% (Scheme 5).

3-(4-Methylbenzamido)-1-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 5 was synthesized using a solvent-free, silica-supported microwave reaction, which was completed within 4 min. and yielded 92% of the desired product after purification (Scheme 5). Similarly, 3-(4-ethylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6 was prepared by reacting 2-bromoacetophenone with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 at room temperature for 30 min., affording 86% yield. The same target molecule was obtained under refluxing conditions within 5 min., yielding 88% (Scheme 6). Alternatively, 3-(4-ethylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6 was synthesized using a solvent-free, silica-supported microwave reaction, which was completed within 3 min. and yielded 90% of the desired product after purification (Scheme 6).

Atom economy (AE)

Atom economy is a measure of the efficiency of a chemical reaction, defined as the percentage of atoms from the reactants that are incorporated into the product (Scheme 7). The atom economy of a reaction can be calculated using the following formula:

Environmental factor

The environmental factor, also known as the E-factor, is a measure of the environmental impact of a chemical reaction. It is defined as the ratio of the mass of waste or side products to the mass of the desired product (Scheme 8).

Here the mass of waste is calculated as follow:

Product mass intensity (PMI)

The Product Mass Intensity (PMI) is a metric that quantifies the efficiency of a chemical reaction. It is defined as the ratio of the total mass of materials used in the reaction (including reactants, solvents, and other additives) to the mass of the desired product (Scheme 9).

Product mass intensity solvent free (PMISF)

The Product Mass Intensity Solvent-Free (PMISF) is a metric that quantifies the efficiency of a solvent-free chemical reaction. It is defined as the ratio of the total mass of reactants and other materials used in the reaction to the mass of the desired product (Scheme 10).

We successfully synthesized novel amide-based mono- and dimeric pyridinium salts using conventional and solvent-free microwave methods. Notably, these quaternization reactions exhibited 100% atom economy, as no side products were formed (Scheme 7; Table 1). In line with the growing emphasis on environmental sustainability in organic chemistry, we evaluated the environmental factor for these reactions and found that no waste was generated, resulting in an environmental polluting factor of zero (Scheme 8; Table 1). Furthermore, we calculated the product mass intensity (PMI) for reactions conducted in the presence of acetonitrile, yielding a PMI value of 1 for all reactions (Scheme 9; Table 1). Similarly, the product mass intensity solvent-free (PMISF) values were found to be zero for all solvent-free reactions (Scheme 10; Table 1). Future studies will focus on investigating the docking scores, hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, bioavailability, and drug-like properties of these novel compounds using molecular modeling calculations. Additionally, we plan to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of these synthesized molecules on cancer cell lines using MTT assays and detect apoptotic cells using EtBr staining.

Protein preparation and molecular docking simulation of B-Rafkinase

In the molecular docking studies, the maestro builder panel was used to create the 3D structures of the synthesized substances. After adding hydrogen atoms, the ligand preparation wizard managed the ring conformations, geometry, and rational bond angles, the three-dimensional X-ray structure of B-Raf Kinase (V600E-BRAF) connected with vemurafenib (PDB-ID: 3OG7)22,23,24 was downloaded from protein data bank (http://www.pdb.org) and amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 were sketched by CHEMSKETCH and converted into PDB format from mol format by OPENBABEL. All bound waters are eliminated from the protein and the polar hydrogen was added to the proteins. Molecular docking studies have been done using the Auto Dock Tools (ADT) version 1.5.6. The energy calculations were made using genetic algorithms. The outputs were exported to PyMol for visual inspection of the binding modes and for possible polar and hydrophobic exchanges of the compounds with VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor. Optimizing the hydrogen molecules, and removing the bound ligand (vemurafenib) from the target prior to the docking procedure.

The binding cavity of V600E-BRAF receptor was predicted using MVD. A cavity which has a volume of 151.04 3 Å3 and a surface area of 462.08 2 Å2 was predicted. The binding site was set inside a restriction sphere of 28 Å radius with the center X: 1.59, Y: − 1.28, Z: − 6.21. Grid resolution used for the MolDock grid score was 0.30 Å. All of the produced compounds (ligands), including the reference inhibitor vemurafenib, were then imported into Molegro Virtual Docker 1.5.6. for molecular docking. The side chains of the amino acid were also positioned inside the Alimited sphere, and their bond flexibility was set accordingly. A tolerance of 1.10 Å and a strength of 0.90 were chosen for the flexibility. The RMSD threshold was set as 2.00 Å for the multiple clusters poses with 100.00 energy penalty values. The docking algorithm was set for a maximum of 1500 iteration with a simplex evolution size of 50. The process begins in the Ligand docking tab, where the user selects the receptor grid file that was generated during the protein preparation phase. This is followed by the selection of the ligand intended for docking. The scaling of the van der Waals radii is then adjusted to a scaling factor of 0.80, along with a partial charge cutoff set at 0.15 Å. After these adjustments, the program is executed, and the resulting output is presented in the workspace.

Validation on the active sites of B-Rafkinase: validation on the active sites of B-Rafkinase

To screen the molecular docking studies of synthesized compounds 1–6 with high energy of B-Raf kinase inhibitor have been employed to investigate the interaction and precise binding sites. The 3D depiction of the interactions between the receptor and molecules is given in Figs. 1 and 2. Compound 2, 3&6 showed one hydrogen bond interaction. Compound 4&5 showed the two hydrogen bonding interactions. The compounds 1–6 have docking scores − 3.789, − 4.582, − 5.387, − 4.205, − 3.652 & − 3.499 kcal/mol respectively (Table 2). The docking score result revealed that all compounds well located in hydrophobic site and strongly interact with B-Raf Kinase inhibitor via π–π stacking, hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions25,26. Based on the docking result the compound with higher negative docking score is considered as more potent. In the present study, compound 3 has higher docking score which influenced one hydrogen bond with residue GLY 534 and number of hydrophobic contacts like ILE 463, VAL 471, LEU 514, ALA 481, PHE 583, ILE 527, TRP 531, CYS 532. By the above facts, the compound 3 substantial binding affinity and regulate the B-Raf kinase activity in therapeutic strategies and cancer prevention.

All the synthesized compounds satisfied four criteria of Lipinski’s “rule of five” (Table 3). As the observed hydrogen bond acceptor values were in the range for all the compounds, and hydrogen bond donor values were predicted 1–2, which predict the safe administration of the drug orally. The LogP values for the compounds 1–6 are observed in the range 0.93–2.16 which is less than 5 that predicts the higher tendency of compounds to penetrate through the biological membrane.

The utilization of the topological polar surface area (TPSA) values less than or equal to 140 Å2 parameter aids in comprehending the passive molecular transportation of drug molecules27. It is evident from the Table 4 that the entire set of the compounds was found to be polar with TPSA values ranging between 41.99 and 78.8 Å2.

The pharmacokinetic properties of amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 are shown in Table 4. Distribution of drugs into the central nervous system (CNS) plays an important role in drug discovery as CNS lies behind the blood brain barrier (BBB). Drugs need to pass over the blood brain barrier (BBB) to reach their target. The BOILED-Egg model, which stands for the Brain Or Intestinal Estimated permeation method, is an intuitive graphical approach designed to precisely forecast passive human gastrointestinal absorption (HIA) and brain permeability (BBB).

The white portion of the egg has a high likelihood of passive absorption by the gastrointestinal tract, while the yellow region (yolk) exhibits a high probability of molecules penetrating the brain. The outer grey region represents compounds with properties indicating predicted low absorption and limited penetration into the brain28.

From the BOILED-Egg plot (Fig. 3).it is observed that all the compounds possess no blood–brain barrier permeant which predict the absence of toxicity at CNS level except compound 1. The LogP values were found to be optimal (less than 5) of synthesized compounds predicted the higher penetration tendency through the biological membranes, indicating the drug-likeness of the complexes. The predicted lipophilicity values of the synthesized DHPMs were in the range − 11.17 to − 3.76 LogPo/w. Among the synthesized compounds 1–6; 1,1′-((2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3-Phenylene)bis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4 showed the lowest lipophilicity value. All the synthesized compounds have high GI absorption; the compounds with high GI absorption could permeate quite easily across the intestinal lining of the cell membrane. P-Glycoprotein (P- gp) plays a key role in keeping non-essential molecules out of the brain and thus has partial permeability29. Table 4 shows that all the compounds are substrates of P-gp indicated by blue dots (Fig. 3) except 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1.The bioavailability radar plot provides a visual representation that aids in evaluating drug-likeness by utilizing the bioavailability index (Fig. 4). Within this plot, the pink region signifies the optimal physiochemical range for oral bioavailability. To be classified as drug-like, the molecule’s radar plot must entirely fall within this pink zone30.

Drug likeness qualitatively evaluates the chance for a molecule to become an oral drug with respect to bioavailability. According to Veber’s rule, the compounds having less than or equal to 10 rotatable bonds show oral bioavailability31. The synthesized compounds have zero violation to Egan and 1 violation to Veber. The bioactive score of the compounds ranges between 0.17 and 0.55, and greater than zero bioactivity score of the compounds suggests that the compounds are biologically active. The predicted ADME properties of complexes evidenced the drug-likeness of the compounds.

The BOILED-Egg model, which stands for the Brain Or Intestinal EstimateD permeation method, is an intuitive graphical approach designed to precisely forecast passive human gastrointestinal absorption (HIA) and brain permeability (BBB).

Monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts inhibits cell proliferation and induces cytotoxicity in lung cancer cells

The MTT assay was employed to determine the anti-proliferative effects of monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 on the A-549 cells after different dosages of these nano particles were administered for 24 h. to test for the inhibition of the growth of human lung cancer cells.We selected the A-549 lung cancer cell line for this investigation as it is one of the most widely utilized in vitro models for lung cancer research. Their robust growth properties, ease of maintenance, and well-documented genetic and molecular profiles make them an excellent choice for studying drug-induced cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and other mechanisms of action in lung cancer. Furthermore, A-549 cells are extensively used in preclinical studies to evaluate the efficacy of potential anticancer compounds, ensuring comparability and relevance with existing literature. The treatment of monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 (10–140 μg/ml) caused a notable decrease in cell proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner as depicted in Fig. 5A,B. At first, the lung cancer cell line A-549 was treated with compound 1–6 at different concentrations (10–140 μg/ml) for 24 h to assess the inhibition of amide-based mono, dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 on growth of the lung cancer cells and the cytotoxic effects were evaluated using MTT assay. After being treated with monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 (p < 0.05) significantly fewer cell proliferation were observed in a concentration dependent manner. Compound 1 and 6 treatment showing significant (p < 0.05) cytotoxic effect on cancer cells compare to control and other groups (Fig. 5A).Subsequently, normal fibroblast cells were treated with the same pyridinium salts 1–6 to analyze their cytotoxic effects. The results indicated that neither the monomeric nor the dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts showed cytotoxic effects on normal fibroblast cells (Fig. 5B). From those different concentrations the IC50 value for 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (87.24 µg/ml),1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 2 (117.41 µg/ml),1,1′-(1,3-phenylenebis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 3 (130.02 µg/ml),1,1′-((2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3-phenylene)bis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4 (37.17 µg/ml),3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 5 (112.29 µg/ml),3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6 (19.08 µg/ml) was used to assess the inhibitory impact and in addition, the morphology was also studied using phase contrast microscope to verify its cytotoxic potential.

(A) The cytotoxic effects of amide-based pyridinium bromides 1–6 on lung cancer cells (A-549) analyzed by MTT assay.Cells were treated with (10–140 µg/ml) for 24 h, and cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). *Compared with the control blank group, p < 0.05. (B) The cytotoxic effects of amide-based pyridinium bromides 1–6 on mouse fibroblast cell line (3T3-L1) were analyzed by MTT assay. Cells were treated with (10–140 µg/ml) for 24 h, and cell viability was evaluated by MTT assay. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). *Compared with the control blank group, p < 0.05.

Based on MTT assay we selected the optimal doses (IC50: 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (87.24 µg/ml),1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 2 (117.41 µg/ml),1,1′-(1,3-phenylenebis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 3 (130.02 µg/ml),1,1′-((2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3-phenylene)bis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4 (37.17 µg/ml),3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 5 (112.29 µg/ml),3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6 (19.08 µg/ml) for further studies. Analysis of cell morphology changes by a phase contrast microscope (Fig. 6). 2 × 105 cells were seeded in 6 well plates and treated with monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 for 24 h. At the end of the incubation period, the medium was removed and cells were washed once with a phosphate buffer saline (PBS pH 7.4). The plates were observed under a phase contrast microscope (Fig. 6A,B).

(A) Effect of amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 on cell morphology of lung cancer cells (A-549). (B) Effect of amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 on cell morphology of mouse fibroblast cell line (3T3-L1). Cells were treated with amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 of IC50 concentrations for 24 h. Along with the control group. Images were obtained using an inverted phase contrast microscope.

In comparison to the control cells, the treated cells exhibited pronounced morphological changes indicative of apoptosis. These changes included cell shrinkage, reduced cell density, and the loss of cell-to-cell contact. Treated cells also displayed additional apoptotic features such as rounding up, detachment from neighboring cells, and in some cases, complete detachment from the plate surface (Fig. 6A). These observations highlight the cytotoxic impact of the compounds on cancer cells, disrupting their structural integrity and viability. Among the tested compounds, compound 3 and 6 demonstrated higher cytotoxic effects in inducing morphological alterations associated with apoptosis. These compounds caused a higher proportion of cells to shrink and led to a more significant reduction in cell density compared to other compounds, underscoring their potential as potent anticancer agents. This enhanced activity could be attributed to the specific molecular mechanisms triggered by compound 3 and 6, which require further investigation to elucidate their mode of action. To assess the cancer cell-specific cytotoxicity of the compounds, normal gingival fibroblast cells were treated with compounds 1–6. Interestingly, the results revealed no observable toxic effects on normal fibroblast cells (Fig. 6B). The morphology of these cells remained unchanged, with normal shape and density preserved throughout the treatment period. This suggests that the compounds selectively target cancer cells without affecting normal cells, a critical feature for potential therapeutic applications.

Monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells

We evaluated the apoptosis induction in A-549 cell line on treatment amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 for 24 h along with control group to analysed their nuclear morphological changes which were observed under florescence microscope after stained with Ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining (Fig. 7). EtBr staining was used to distinguish the live and dead cells. EtBr is a fluorescent dye that can only penetrate cells with compromised membranes, a characteristic of dead or dying cells (late-stage apoptosis or necrosis). Healthy, viable cells exclude EtBr, making EtBr -positive staining a reliable indicator of cell death (Fig. 7). If the EtBr staining shows a high percentage of EtBr -positive cells in the treated groups, this would indicate a significant increase in cell death, consistent with the reduced cell population observed (Fig. 7). A-549 cells treated with amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 showed increased number of dead cells compare to control groups.

Detection of apoptotic cells in amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 treated lung cancer cells by EtBr staining. Human Lung cancer cells were treated with amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 for 24 h. along with the control group. After treatment, the cells underwent EtBr staining incubation. An inverted fluorescence microscope was utilized for capturing pictures.

The amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides 1–6 were designed with functional groups that enhance their interaction with cancer targets through π-π stacking, hydrophobic contacts, and hydrogen bonding. Docking studies revealed strong binding affinities, particularly for compounds 3 and 6, with negative docking scores of − 5.387 and − 3.789 kcal/mol, respectively, indicating robust interactions with key residues in the hydrophobic site of the V600E-BRAF kinase, such as ILE 463, LEU 514, and PHE 583. These interactions align with their observed in vitro anticancer activity. Further, the impact of amide-based pyridinium bromides 1–6 on the expression of key MAPK signaling pathway genes—B-RAF, ERK, and Cyclin D1—was evaluated in A-549 lung cancer cells. Gene expression levels were assessed relative to untreated control cells, with normalization to GAPDH as the internal reference gene. Results are presented as fold changes and expressed as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (Fig. 8). The treated groups showed a statistically significant downregulation of B-RAF, ERK, and Cyclin D1 expression levels compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Among the tested compounds, compound 3 demonstrated the most pronounced effect, exhibiting the highest reduction in the expression of all three target genes. This finding is consistent with the docking studies, which identified compound 3 as having the strongest binding affinity to the B-RAF kinase target. The down regulation of B-RAF by compound 3 correlated with a significant decrease in down stream signaling molecules ERK and Cyclin D1, indicating effective disruption of the MAPK signaling pathway. Compounds 2 and 6 also showed significant but comparatively moderate reductions in gene expression levels, while the effects of compounds 1, 4, and 5 were less pronounced. These results suggest that the anticancer effects of the tested compounds, particularly compound 3, are mediated through the inhibition of MAPK pathway signaling, contributing to their ability to suppress cell proliferation in A-549 cells. These findings emphasize the compounds’ structural features and mechanisms contributing to their anticancer efficacy.

The lung cancer cell line A-549 was used to examine the effects of amide based pyridinium bromides 1–6 treated on the expression of MAPK signaling molecules genes (B-RAF, ERK and Cyclin D1). The results were displayed as fold changes in comparison to the control, with the expression levels of target genes normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. The graph displays the mean ± SEM for each of the three separate experiments. A statistically significant difference between the drug-treated and control groups is indicated by the symbol "*" at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Conclusion

This study successfully synthesized amide-based monomeric and dimeric pyridinium bromides using room temperature stirring, refluxing, and solvent-free domestic microwave-assisted reactions. The microwave-assisted reactions proved to be efficient, with shorter reaction times, higher yields, and easier workup procedures, resulting in spectroscopically pure products. Molecular docking simulations revealed that m-xylene-linked amide-substituted dimeric pyridinium bromide 3 exhibited the highest docking score among the target molecules, indicating strong π–π stacking, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bonding interactions with B-Raf kinase. Cytotoxicity studies against the lung cancer cell line A-549 using the MTT assay showed that 3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6 exhibited potent cytotoxic activity, while displaying no toxicity to normal fibroblast cells. Compounds 3 and 6 demonstrated selective and potent anticancer effects, highlighting their potential as therapeutic agents in cancer treatment.

Experimental section

General procedure

All the required chemicals were purchased from Merck Chemicals and Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals and used directly without further purification.The melting points of all the compounds were determined using a Buchi instrument with model M-560 and were uncorrected. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker 400 MHZ and Bruker 100 MHZ spectrometer respectively; using CDCl3, and DMSO-d₆ as a solvents.The following abbreviations were used to describe multiplicities: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), and m (multiplet). Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) and referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS). Coupling constants are reported in Hertz (Hz). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) for all compounds was performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) (SHIMADZU, Advanced Q-TOF).

Synthesis of 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1

To a solution of 3-aminopyridine in dry CH3CN, anhyd. K2CO3 was added. The mixture was cooled to ice-cold conditions, and p-tolyl chloride was slowly added over 5 min. The resulting colorless crude product was filtered, washed with CH3CN, and dried. The crude product was then purified by column chromatography.Yield 7.5 g, (80%); mp.: 140–142 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.58 (s, 1H), 8.22–8.23 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H), 8.16–8.19 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 7.70–7.72 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.17–7.19 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.14–7.16 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 2.32 (s, 3H);13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.5, 145.0, 142.8, 141.5, 135.2, 131.3, 129.4, 127.9, 127.3, 123.7, 21.5; HRMS m/z 213.10; Anal. Calcd..for: C13H12N2O: C:73.58: H:5.66: N:13.20; Found C:73.53; H:5.61; N:12.98 (Supplementary figures S1-S3).

Synthesis of 1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 2

1,6-Dibromohexane (4.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was reacted with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide (1) (8.0 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) in CH3CN under refluxing conditions for 15 min., yielding a colorless precipitate. The crude product was washed with CH3CN. Yield 1.61 g, (86%); mp.: 242–245 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.70 (s, 2H), 8.12–8.14 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.02–8.05 (d, J = 12 Hz, 4H), 7.83–7.85 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.37–7.40 (d, J = 12 Hz, 4H), 7.17–7.19 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 4.65–4.67 (t, J = 8 Hz, 4H), 3.38 (s, 6H), 1.96 (q, 4H), 1.37 (q, 4H);13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.6, 143.5, 140,0, 139.6, 136.3, 135.6, 130.4, 129.6, 128.6, 128.4, 61.5, 30.8, 25.1, 21.5; HRMS m/z 254.14; Anal. Calcd. for: C32H36Br2N4O2: C: 57.48; H: 5.38; N: 8.38; Found C: 57.45; H: 5.35; N: 8.34 (Supplementary figures S4-S6).

Synthesis of 1,1′-(1,3-phenylenebis(methylene))bis3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 3

m-Xylenedibromide (3.8 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (7.6 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were dissolved in dry CH3CN and stirred at room temperature for 1 h, yielding a colorless precipitate. The precipitate was washed with CH3CN to remove unreacted reactants, and no further purification was required. Yield: 2.15 g, (88%); mp.: 235–237 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.25 (s, 2H), 9.72 (s, 1H), 9.02–9.04 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.79–8.81 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.17–8.22 (dd, J = 12 Hz, 12 Hz, 2H), 7.94–7.96 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), 7.59–7.63 (m, 3H), 7.36–7.38 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), 5.98 (s, 4H), 2.40 (s, 6H);13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.5, 143.6, 140.1, 140.0, 136.0, 135.6, 130.6, 130.3, 130.2, 129.6, 128.8, 128.5, 63.7, 21.5; HRMS m/z 264.12; Anal. Calcd.for: C34H32Br2N4O2: C: 59.30; H: 4.65: N: 8.13; Found C: 59.27; H: 4.61; N: 8.08 (Supplementary figures S7-S9).

Synthesis of 1,1′-((2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3-phenylene)bis(methylene))bis3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4

2,4-Bis(chloromethyl)-1,3,5-trimethylbenzene (4.6 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was reacted with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (9.2 mmol, 2.01 equiv.) in dry CH3CN at room temperature for 2 h., yielding the desired product. The crude product was washed with CH3CN to remove impurities, resulting in a higher percentage yield.Yield: 1.29 g, (87%); mp 240–242 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.70 (s, 2H), 9.45 (s, 1H), 9.05–9.08 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 8.86–8.88 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.11–8.15 (dd, J = 8 Hz, 8 Hz, 2H), 8.00–8.03 (d, J = 12 Hz, 4H), 7.27–7.29 (d, J = 8 Hz, 4H), 6.07 (s, 4H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 2.37 (s, 6H), 2.33 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.6, 143.4, 142.0, 141.6, 140.5, 139.2, 135.5, 134.7, 132.2, 130.3, 129.5, 128.8, 128.5, 128.3, 59.1, 21.5, 20.2, 16.7; HRMS m/z 285.15; Anal. Calcd.for: C37H38Cl2N4O2: C: 69.26; H: 5.92: N: 8.73; Found C: 69.22; H: 5.87: N: 8.68 (Supplementary figures S10-S12).

Synthesis of 3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 5

4-Nitrobenzyl bromide (4.6 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was reacted with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (5.0 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) in dry CH3CN at room temperature for 1 h., yielding a colorless precipitate. The crude product was washed with CH3CN to remove unreacted starting materials. Yield 1.68 g, (85%); mp.; 220–223 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.22 (s, 1H), 9.74 (s, 1H), 9.04–9.06 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.78–8.81 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 8.31–8.34 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 8.20–8.25 (dd, J = 12 Hz, 12 Hz, 1H), 7.81–7.83 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.42 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 6.13 (s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.5, 148.4, 143.6, 141.6, 140.4, 140.2, 136.26, 136.20, 130.3, 129.7, 129.0, 128.5, 124.6, 63.0, 21.5; HRMS m/z 348.13; Anal. Calcd.for: C20H18BrN3O3: C: 56.07; H: 4.20: N: 9.81; Found C: 56.02; H: 4.17: N: 9.77 (Supplementary figures S13-S15).

Synthesis of 3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6

2-Bromoacetophenone (5.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) was reacted with 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (5.5 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) in dry CH3CN at room temperature for 30 min., yielding a colorless precipitate. The crude product was washed with CH3CN to remove unreacted starting materials. yield 1.64 g, (86%); mp.; 225–227 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 11.26 (s, 1H), 9.72 (s, 1H), 8.79–8.81 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 8.27–8.30 (t, J = 12 Hz, 1H), 8.07–8.10 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 8.03–8.05 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.97–8.00 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 7.78–7.80 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.65–7.68 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 7.40–7.43 (d, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 6.61 (s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 3H);13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 191.2, 166.5, 143.6, 141.5, 139.7, 137.7, 136.3, 135.1, 134.1, 130.4, 129.7, 129.5, 128.7, 128.6, 128.2, 67.4, 21.5; HRMS m/z 331.14; Anal. Calcd.for: C21H19BrN2O2: C: 61.31; H: 4.62: N: 6.81; Found C: 61.27; H: 4.59: N: 6.57 (Supplementary figures S16-S18).

General procedure for solid-supported solvent-free microwave reactions

A mixture of 1,6-dibromohexane (4.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl) benzamide 1 (8.02 mmol, 2.01 equiv) was combined with 5 g of silica gel (80–120 mesh) and then gently grinding with a mortar and pestle to ensure uniform mixing. The reaction mixture was then divided into five portions for optimization of the reaction conditions. The reactions were monitored at 1-min intervals for each portion. After the disappearance of 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl) benzamide, the mixture was washed with hexane to remove unreacted 1,6-dibromohexane, followed by extraction with ethanol to obtain 1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis3-(4-methyl benzamido) pyridin-1-ium bromide. Similarly, other similar reactions were carried out based on our available reports32.

In vitro—cytotoxic studies

Cell line maintenance

The cell lines for lung cancer (A-549) and mouse fibroblast (3T3-L1) were procured from the National Center for Cell Science (NCCS) in Pune. The cells were grown in a T25 culture flask with 1% antibiotics, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) from Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. In a CO2 incubator, the cells were kept humid with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Trypsinization and the subsequent passage were performed on cells that had reached 80% confluence.

Cell viability (MTT) assay

The cell viability of monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 treated lung cancer and normal fibroblast cell line was assessed by MTT assay. The assay is based on the reduction of soluble yellow tetrazolium salt to insoluble purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. Lung cancer and normal fibroblast cell line was plated in 96 well plates at a concentration of 5 × 103 cells/well 24 h.after plating, cells were washed twice with 100 μl of serum-free medium and starved by incubating the cells in serum-free medium for 3 h. at 37 °C. After starvation, cells were treated with different concentrations of monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 (10–140 μg/ml) for 24 h. At the end of treatment, the medium from control and monomeric, dimeric amide-based pyridinium salts 1–6 treated cells were discarded and 100 μl of MTT containing DMEM (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well. The cells were then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in the CO2 incubator. The MTT containing medium was then discarded and the cells were washed with 1 × PBS. Then the formazan crystals formed were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μl) and incubated in dark for an hour. Then the intensity of the color developed was assayed using a Micro ELISA plate reader at 570 nm. The number of viable cells was expressed as percentage of control cells cultured in serum-free medium (Fig. 1). Cell viability in control medium without any treatment was represented as 100%.

The cell viability is calculated using the formula:

Cell morphological analysis

The optimal doses (IC50) for 4-methyl-N-(pyridin-3-yl)benzamide 1 (87.24 µg/ml),1,1′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 2 (117.41 µg/ml),1,1′-(1,3-phenylenebis(methylene))bis3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium bromide 3 (130.02 µg/ml),1,1′-((2,4,6-trimethyl-1,3-phenylene)bis(methylene))bis(3-(4-methylbenzamido)pyridin-1-ium chloride 4 (37.17 µg/ml),3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(4-nitrobenzyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 5 (112.29 µg/ml),3-(4-methylbenzamido)-1-(2-oxo-2-phenylethyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide 6 (19.08 µg/ml) were selected based on MTT assay for the lung cell line and these concentrations used for further studies. In 6 well plates, 2 × 105 cells were seeded and treated with compounds for 24 h. The morphology of the both lung cancer and fibroblast cells is examined after the treatment with a phase contrast microscope. The cells were removed from the media after incubation period and given one wash in phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4). The plates were examined using a phase contrast microscope.

Determination of nuclear morphological changes of cells (EtBr staining)

For the nuclear morphological analysis, 2 × 105 cells were seeded in 6 well plates and allowed to proliferate for 24 h, the resulting monolayer of cells was washed with PBS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and incubated with 0.5 µg/ml of EtBrstainfor 5 min. The apoptotic nuclei (intensely stained, fragmented nuclei, and condensed chromatin) were viewed under a fluorescent microscope.

Real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RT-PCR was used to study the MAPK gene expression and chemokine signaling molecules. A Trizol reagent (Sigma) is used to extract the RNA using standard protocols. The PrimeScript 1st strand cDNA synthesis kit (TakaRa, Japan) was used to synthesize cDNA from 2 μg of RNA. Target genes were amplified with specific primers, whose sequences are listed below BRAF- Forward: “AGAAAGCACTGATGATGAGAG” Reverse: “GGAAATATCAGTGTCCCAACA”; Erk- Forward: “CAGGCTGTTCCCAAATGCT”, Reverse: “CGAACTTGAATGGTGCTTCG”; Cyclin D1- Forward: “GCGGAGGAGAACAAACAGAT”, Reverse: “TGAACTTCACATCTGTGGCA”; GAPDH- Forward: “ CGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA”, Reverse: “ TGAACTTCACATCTGTGGCA”. The PCR reactions were carried out with GoTaqqPCR Master Mix (Promega), which includes SYBR Green I dye and all other PCR components. Real-time PCR was performed with the Bio-Rad CFX96 PCR system. The cycle threshold (CT) values were evaluated using the comparative CT method, and the relative fold change in expression was calculated using the 2^(-ΔΔCT) method.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test SPSS, were used to evaluate the obtained data. The statistical analysis on all experimental data, with P < 0.05 being deemed statistically significant.

Data availability

The data supporting this article has been included within this manuscript and its ESI.

References

Chowdhury, M. R. et al. Ionic-liquid-based paclitaxel preparation: a new potential formulation for cancer treatment. Mol. Pharm. 15(6), 2484–2488 (2018).

Malhotra, S. V., Kumar, V., Velez, C. & Zayas, B. Imidazolium-derived ionic salts induce inhibition of cancerous cell growth through apoptosis. Med. Chem. Comm. 5(9), 1404–1409 (2014).

Silva, A. T. et al. Antiproliferative organic salts derived from betulinic acid: Disclosure of an ionic liquid selective against lung and liver cancer cells. ACS Omega 4(3), 5682–5689 (2019).

Rezki, N. et al. Design, synthesis, in-silico and in-vitro evaluation of di-cationic pyridiniumionic liquids as potential anticancer scaffolds. J. Mol. Liq. 265, 428–441 (2018).

Kaushik, N. K., Attri, P., Kaushik, N. & Choi, E. H. Synthesis and antiproliferativeactivity of ammonium and imidazoliumionicliquids against T98G brain cancer cells. Molecules 17, 13727–13739 (2012).

Ferraz, R. et al. Antitumoractivity of ionic liquids based on Ampicillin. Chem. Med. Chem. 10, 1480–1483 (2015).

Sehrawat, H. et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel 1,3—benzodioxole tagged noscapine based ionic liquids with in silico and in vitro cytotoxicity analysis on HeLacells. J. Mol. Liq. 302, 112525–112535 (2020).

Aljuhani, A. et al. Novelpyridinium based ionic liquids with amide tethers: Microwave assisted synthesis, molecular docking and anticancer studies. J. Mol. Liq. 285, 790–802 (2019).

Govindaraj, S. et al. Synthesis of potent MDA-MB 231 breast cancer drug molecules from single step. Sci. Rep. 25, 18241–18253 (2023).

Ganapathi, P. & Ganesan, K. Anti-bacterial, catalytic and docking behaviours of novel di/trimericimidazolium salts. J. Mol. Liq. 233, 452–464 (2017).

Ganapathi, P. & Ganesan, K. Synthesis and characterization of antibacterial ionic liquids moieties under multiple routes and their catalytic responses. J. Drug Res. Dev. 4, 1–13 (2017).

Govindaraj, S. et al. Discovery of novel dimericpyridinium bromide analogs: Inhibits cancer cell growth by activating caspasesanddownregulating Bcl-2 protein. ACS Omega 8, 13243–13251 (2023).

Ganapathi, P., Ganesan, K., Vijaykanth, N. & Arunagirinathan, N. Anti-bacterial screening of water-soluble carbonyl diimidazolium salts and its derivatives. J. Mol. Liq. 219, 180–185 (2016).

Ganapathi, P., Ganesan, K., Dharmasivam, M., Alam, M. M. & Mohammed, A. Efficient antibacterial dimeric nitro imidazolium type of ionic liquids from simple synthetic approach. ACS Omega 6, 44458–44469 (2022).

Tamilarasan, R. et al. Synthesis, characterization, pharmacogenomics and molecular simulation of pyridinium type of ionic liquids under multiple approach and its applications. ACS Omega 16, 4144–4155 (2023).

Singh, U. et al. Design of novel 3-pyrimidinylazaindole CDK2/9 inhibitors with potent in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy in a triple-negative breast cancer model. J. Med. Chem. 60, 9470–9489 (2017).

Ali, S. et al. The development of a selective cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that shows antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 67, 8325–8334 (2007).

Soudy, R., Etayash, H., Bahadorani, K., Lavasanifar, A. & Kaur, K. Breast cancer targeting peptide binds keratin 1: A new molecular marker for targeted drug delivery to breast cancer. J. Med. Chem. 60, 4893–4903 (2017).

Jagabandhu, D. et al. 2-Aminothiazole as a novel kinase inhibitor template. Structure−activity relationship studies toward the discovery of N-(2-Chloro-6-methylphenyl)-2-[[6-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1- piperazinyl)]-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinyl]amino)]-1,3-thiazole-5-carboxamide (Dasatinib, BMS-354825) as a potent pan-Src kinase inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 59, 9788–9805 (2016).

Da Re, P., Verlicchi, L. & Setnikar, I. β-Phenoxyethylamines with local anesthetic and antispasmodic activity. J. Med. Chem. 44, 1072–1084 (2001).

Köhler, S. C. & Wiese, M. HM30181 derivatives as novel potent and selective inhibitors of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2). J. Med. Chem. 58, 3910–3921 (2015).

Brose, M. S. et al. BRAF and RAS mutations in human lung cancer and melanoma. Cancer Res. 1, 6997–7000 (2002).

Gideon, B. et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature 30, 596–599 (2010).

Choi, W. K., El-Gamal, M. I., Choi, H. S., Baek, D. & Oh, C. H. New diarylureas and diarylamides containing 1, 3, 4-triarylpyrazole scaffold: Synthesis, antiproliferative evaluation against melanoma cell lines, ERK kinase inhibition, and molecular docking studies. E. J. Med. Chem. 46, 3714–3720 (2011).

Adedirin, O., Uzairu, A., Shallangwa, G. A. & Abechi, S. E. Optimization of the anticonvulsant activity of 2-acetamido-N-benzyl-2-(5-methylfuran-2-yl) acetamide using QSAR modeling and molecular docking techniques. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 7, 430–440 (2018).

Umar, B. A., Uzairu, A., Shallangwa, G. A. & Uba, S. Rational drug design of potent V600E-BRAF kinase inhibitors through molecular docking simulation. J. Eng. Exact Sci. 5, 0469–0481 (2019).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. Swiss ADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 3, 42717–42729 (2017).

Liu, X., Testa, B. & Fahr, A. Lipophilicity and its relationship with passive drug permeation. Pharm. Res. 28, 962–977 (2011).

Krämer, S. D. & Wunderli-Allenspach, H. Physicochemical properties in pharmacokinetic lead optimization. Farmaco 56, 145–148 (2001).

Ritchie, T. J., Ertl, P. & Lewis, R. The graphical representation of ADME-related molecule properties for medicinal chemists. Drug Discov. Today 16, 65–72 (2011).

Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 6, 2615–2623 (2002).

Govindaraj, S. et al. 2-Chloro-3-cyano-4-nitrobenzyl pyridinium bromide as a potent anti-lung cancer molecule prepared using a single-step solvent-free method. RSC Adv. 14, 24898–24909 (2024).

Acknowledgements

M.S. thanks to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R1005), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

M.S is thankful to King Saud University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for the financial support granted under the Researchers Supporting Project (RSPD2025R1005), which made this work possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sadaiyan Govindaraj: synthesis and characterization Kilivelu Ganesan: analysis, Drafting, editing, Perumal Elumalai: Anticancer activity screening Rajanathadurai Jeevitha: Anticancer activity screening Jospin Sindya: Anticancer activity screening Subramani Annadurai: Docking analysis Shiek SSJ Ahmed: Computational support Mudassar Shahid: Funding support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Govindaraj, S., Ganesan, K., Elumalai, P. et al. Solid-phase synthesis and cytotoxic evaluation of novel pyridinium bromides. Sci Rep 15, 10151 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92672-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92672-8