Abstract

Limited data from single source pose a significant constraint on the accuracy of risk assessment conducted during the pre-excavation feasibility analysis stage. In order to address this issue, a risk assessment method that integrates cloud model (CM) with Dempster–Shafer (D–S) evidence theory is proposed. This method carefully selects multi-source risk evaluation indicators from project information and three-dimensional finite element numerical results to create project database and numerical database. By leveraging these databases, the CM generates the membership degrees for various evaluation indicators across different risk levels, which are then transformed into basic probability assignments within the D–S evidence theory. This allows for effective fusion of multi-source risk evaluation indicators achieving comprehensive quantitative evaluation of excavation. A narrow and elongated foundation project is assessed with a risk level of IV (safety) by the proposed approach. The outcomes provide a scientific basis for formulating preventive strategies and managerial decisions about foundation excavation during the pre-excavation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Risk assessment is crucial for foundation excavation during the pre-excavation feasibility analysis stage. It aids in early identification of risks, enabling project managers to make timely preventive decisions and thereby reducing the likelihood of accidents. With the rapid advancements in underground engineering, there is a noticeable trend toward larger excavation scales and denser adjacent structures in foundation development1,2. This trend has made foundation engineering fraught with complex constraints, such as intricate geotechnical conditions, limited exploration information, cumbersome construction procedures, etc., which have further increased the difficulty of risk assessment. Especially during the pre-excavation feasibility analysis stage where the project has not yet begun, there are often practical dilemmas such as limited data sources and insufficient data volume3,4. Consequently, this hinders assessors to accurately capture the multi-dimensional characteristics of foundation excavation safety, thereby compromising the precision and effectiveness of the assessment results. To overcome this bottleneck, there is an urgent need to actively explore the fusion of data information from multi-sources to provide more comprehensive and reliable support for risk assessment.

At this stage, since the project has not yet commenced, selecting risk evaluation indicators and collecting data present certain challenges and limitations. It is necessary to fully utilize multi-source data information obtained from preliminary geological surveys, construction plans, designs, and construction drawings. Furthermore, with continuous technological advancements and the accumulation of practical application experience, three-dimensional (3D) finite element (FE) technology is gradually being integrated with various information technologies to maximize its potential benefits5,6. This technology can simulate the excavation process of foundation, considering the surrounding built environment, and output key evaluation indicators such as stress distribution7, deformation characteristics8, and seepage fields9, providing robust data support for risk assessment. In summary, combining geological conditions, construction plans, and results from 3D FE numerical simulations for risk evaluation offers significant advantages. By fusing multi-source evaluation indicator data, potential risks can be more comprehensively identified and analyzed from multiple perspectives and dimensions, thereby enhancing the accuracy and effectiveness of the assessment.

Such assessment assist decision-makers in accurately identifying high-risk sources, facilitating the optimization of structural design schemes, and reducing the potential for catastrophic accidents during excavation. How to effectively fuse multi-source evaluation indicators data for comprehensive assessment, thereby providing a reference for decision support, has increasingly attracted the attention of researchers. In response to practical problems, various methods are adopted based on the differences in data characteristics of information sources, including the weighted average10, feature extraction11, and random class12, etc. However, simple combination or averaging methods are inadequate for handling these complex data types arising from geotechnical engineering13,14. With the development of probability theory and statistics, statistical inference methods based on prior probabilities and extracted features, such as Bayesian estimation15, and Kalman filtering16, have gradually been adopted. Yet, their application in actual foundation projects remains limited because these methods rely on stringent assumptions and involve intensive computational processes17. In contrast, the Dempster–Shafer (D–S) evidence theory method in the random classification method has better flexibility and adaptability than other methods18. It is good at dealing with uncertain multi-source data through the principles of “evidence body” and “fusion”, serving as an effective tool for handling nonlinear multi-source evaluation indicator data generated during the excavation of foundation.

The D–S evidence theory has been widely used in risk assessment research of dams19, mine20, bridge21, tunnel22, and other engineering projects. However, previous studies are mostly based on the integration of qualitative probability data. For multi-source evaluation indicators data generated by foundation excavation, needs to be transformed to improve the accuracy of basic probability assignment (BPA) assessment. The cloud model (CM) has significant advantages in processing multi-source risk evaluation indicators data and can quantitatively transform complex23. These membership degrees can be converted into the basic probability distribution of the D–S evidence theory, thereby fusing, and updating multi-source evidence information. This process provides more accurate and reliable data support for risk assessment. Practice has proved that the reliability of the integration of CM and D–S evidence theory has been verified in many fields, such as the operational performance assessment of green public buildings24, fault diagnosis analysis25, and chemical reaction process risk assessment18. Therefore, using CM to transform multi-source evaluation indicators obtained from database into the basic probability distribution of D–S evidence theory fusion evidence body can provide quantitative data for the final risk rating assessment results, thus providing scientific basis for decision-making.

Considering these insights, this research seeks to propose a risk assessment method that integrates CM with D–S evidence theory to assess the potential severity of accidents. The model is designed to select risk evaluation indicators from project information and 3D FE numerical results, overcoming the constraint of limited data availability prior to excavation, and accordingly establish project and numerical databases. Utilizing the accumulated databases, this study integrates CM with the D–S evidence theory to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the risk status during foundation excavation, thereby enhancing the reliability of the assessment results. The structure of this study is as follows: Section “Methodology” describes the methodology for risk assessment in foundation excavation. Section “Results” examines the application of this method in a narrow-long foundation excavation project. The efficacy of the proposed assessment method is discussed in Section “Discussion”. The research concludes with primary findings and study limitations in Section “Conclusion”.

Methodology

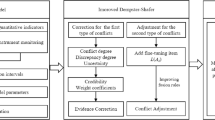

The objective of this study is to develop a precise risk assessment method for foundation excavation by integrating CM and D–S evidence theory. To achieve this goal, this study first carefully selects multi-source risk evaluation indicators from project information and 3D FE numerical results to create project databases and numerical database. Using these databases, the BPA through the CM method was calculated. Subsequently, the effective fusion of multi-source evaluation indicators was achieved based on D–S evidence theory, leading to a comprehensive evaluation of excavation risk levels and an examination of the evolution of risk states. Figure 1 illustrates the detailed process of risk assessment and its application steps in a flowchart format, providing clear guidance for practical operations.

Multi-source evaluation indicators database creation

Project database creation

The construction of the project database relies on the collection and integration of key information such as geological conditions, construction plans, design and construction drawings26,27,28. Through detailed analysis of this key information, representative evaluation indicators reflecting the level of foundation risk are extracted.

Geological conditions are one of the crucial factors determining the risk of the foundation. By thoroughly analyzing geological survey reports, precise geotechnical parameters such as soil type, friction angle, and cohesion can be accurately extracted. These parameters not only reveal the impact of geological conditions on the design and construction of underground space projects but also serve as an important basis for assessing the risk level of the engineering project. In this process, the size of the data volume needs to be determined according to the scale of the project, the complexity of the geology, and the requirements of analysis accuracy, to ensure that the key areas can be comprehensively covered without reducing the efficiency of the analysis due to excessive data volume, to more intuitively analyze the impact of geological conditions on the stability of the foundation.

Construction plan is crucial for ensuring the safe construction of the foundation. A reasonable and comprehensive construction program provides a strong guarantee for efficient and safe construction practices and effectively reduces the risks that may be encountered during the implementation of the project. The construction program records in detail every step of the construction process, including the excavation method, the selection and implementation of support structures, and drainage measures. This study analyzes these elements one by one, especially the parts that are directly related to pit safety, such as the reasonableness of the excavation sequence and the stability assessment of the support structure. In the process of data extraction, this study not only pays attention to the textual description of the program but also pays attention to the feedback of the on-site implementation, by comparing the actual construction data with the program expectations. In addition, this study pays special attention to the change records of the construction program to ensure that the information in the database can truly reflect the status of the project.

Design and construction drawings are important documents that reflect the status of foundation risk. These drawings depict the spatial layout, dimensions, material properties, and other key information of the underground structure, which not only provide intuitive and accurate guidance for the construction personnel’s on-site operation but also provide an important basis for the engineers in the process of quality control and construction supervision. In the process of analyzing, this study focuses on the details, such as the geometric dimensions of structural components, reinforcement information, material types and specifications, and so on. At the same time, the study also pays attention to the special requirements, safety precautions, and construction guidelines in the design instructions to ensure that these data can provide intuitive and accurate guidance for the construction personnel in the field operations and provide strong support for the engineers to carry out quality control and supervision.

Numerical database creation

To obtain more accurate stress and deformation data during the foundation excavation, a 3D FE numerical simulation was developed. Data extraction points were designated in each foundation section before initiating the 3D FE numerical simulation to create a database. Based on the numerical database, the deformation evolution between the foundation and adjacent structures determine potential hazardous zones during excavation. This simulation process can be divided into four primary components: definition of basic assumptions, selection of geomaterial parameters and structures, decisions regarding scheme and grid partitioning, and the design of the construction stage.

Step 1: Definition of basic assumptions.

In creating 3D models using advanced approaches certain conditions should be presupposed within the confines of the simulation29,30. Firstly, it was assumed that the initial stress field was influenced solely by its weight. Simultaneously, the soil layer displayed a horizontally stratified and homogeneous distribution. Any changes in the elastic modulus parameters of soil due to excavation were disregarded. The stress and strain attributes of the soil were assumed to remain constant over time. To represent the influence of adjacent structures, an equivalent load was applied.

Step 2: Selection of geomaterial parameters and structures.

Parameters regarding the soil were acquired via a rigorous statistical analysis, which incorporated data from laboratory tests and on-site assessment. Standard parameters were chosen as foundational metrics, especially when considering less favorable combinations7,26.

The 3D FE numerical simulation denotes that constructing interlocking piles is inherently complex. For this research, the interlocking pile was modified in alignment with the equivalent moment of inertia. The spatial arrangement of the interlocking piles can be observed in Fig. 2. Considering the sensitivity of fine grianed soils and then employing Eq. (1)31,32,33, one can determine the equivalent thickness of the diaphragm wall.

where D is the diameter of the interlocking pile, d is the pile spacing; and h is the equivalent thickness.

Step 3: Decisions regarding scheme and grid partitioning.

Based on the Saint–Venant principle34, the total height of the 3D FE numerical simulation was set at approximately three times the excavation depth. The length and width of the numerical simulation were assumed to be five times the excavation depth. Risks to adjacent structures within the influence area of the excavation were considered, with loads of these structures being simulated by an equivalent load, in line with established codes and relevant literature35. Each building layer produces a load ranging from approximately 18–25 kN/m236. The bridge and culvert loads consist of the primary dead load and the primary live load37. The uniform live load of the light rail traffic bridge stands at 28 kN/m, while the dead load of the bridge pier is 160 kN38. In architectural designs, the standard values for bus parking live load and fire truck parking live load are 4.0 kN/m2 and 20.0 kN/m2, respectively33.

Step 4: Design of the construction stage.

The guide wall and sleeve occluding pile were constructed before the excavation of the foundation commenced. Crown beams and temporary columns were installed once the occluding pile was completed. The water was then dewatered, ensuring the water level remained 0.5 m below the excavation face. Upon completing these preliminary tasks, the foundation was ready for excavation. The excavation approach involved slope excavation, progressing to the first support, breaking the pile head to pour the crown beam, and retaining wall, and backfilling the slope section of the retaining wall after excavation. This was followed by using the bottom mold to pour the first concrete support. As the foundation excavation continued, excavating the foundation and erecting columns were performed alternately. The soil was excavated layer by layer, placing the column 0.5 m below the new level after each excavation. Over-excavation was strictly prohibited.

Multi-source evaluation indicators data fusion

BPA construction of multi-source evaluation indicators based on CM

Step 1: Cloud-based evaluation indicators.

The core of D–S evidence theory is to construct BPA. The CM is mainly used to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the transformation between quantitative and qualitative indicators, providing strong support for the comprehensive assessment of multi-source evaluation indicators. By transforming the actual input values into the BPA required for D–S evidence theory fusion, the CM effectively solves the compatibility problem of traditional methods in dealing with multi-source evaluation indicators.

The digital properties of the CM are represented by three exponents: expected value Ex, entropy En, and hyper-entropy He. These three exponents can be used to describe the shape and distribution characteristics of the foundation risk CM. Ex represents the centroid of cloud droplets, which can represent typical foundation risk sampling points in the number domain space. En represents the range of the raindrop distribution, which reflects the uncertainty of the foundation risk measurement. He, as an indicator of the condensation state of cloud droplets, reflects the cohesion of the uncertainty. The range of each evaluation indicator for the foundation is [Cmin, Cmax], and the numerical characteristic values of each sub-interval are C (Exm, Enm, Hem), m = 1, 2,…,4, which can be calculated by Eq. (2)39.

where k is a constant representing the standard value of super-entropy, and this study assumes k = 0.05.

Step 2: Calculation of evaluation indicators eigenvalue membership degree.

Calculate the membership values of different levels (Exm, Enm, Hem) of CM using equations. These membership values are the BPA for providing a reliable basis for multi-source evaluation indicators data fusion. Calculate the membership μ(xij) of the ith indicator feature value xi with the jth level of the foundation excavation safety risk assessment, as shown below23.

Step 3: Determination of the BPA.

In the process of assessing excavation risk for foundation based on the fusion of multi-source information, including preliminary geological surveys, construction plans, designs, working drawings, and numerical simulations, uncertainty mainly arises from two aspects: the diversity and variability of data sources, and the complexity involved in data fusion. This encompasses the handling of inconsistencies in data formats, units, and precision, as well as considerations of correlation, redundancy, and conflict among different data sources. These challenges may be amplified or propagated during the data fusion process, thereby further exacerbating the uncertainty in risk assessment outcomes.

Given the significant impact of this uncertainty on foundation excavation risk assessment results, there is an urgent need for an effective measurement method to quantify this uncertainty, ensuring that evaluation indicator Ci accurately reflects risk level Tj and conforms to the definition of BPA25.

where θi represents the degree to which the eigenvalue of the ith evaluation indicator is uncertain of belonging to the jth level; mi(Θ) represents the uncertainty of the entire set; and mi (Tj) represents the BPA of the ith evaluation indicator in the jth risk state.

Multi-source evaluation indicators data fusion based on D–S evidence theory

D–S evidence theory is a powerful method of uncertainty reasoning that obtains the confidence distribution of propositions through combinatorial reasoning of evidence, effectively handling uncertain knowledge and having excellent decision-making capabilities.

Step 1: Detection and fusion of normal evidence.

The risk assessment of foundation is based on multi-source evaluation indicators, which constitute a set of mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive propositions. When the information of each evidence body is known and integrated into the assessment process, the probability sum of the complete evidence set equals 1. In this study, the BPAs of various indicators previously obtained are fused to derive the final risk level of foundation deformation. The definition of the identification framework is: \(\Theta = \left\{ {\left\{ {\theta_{1} ,\theta_{2} ,\theta_{3} ,...,} \right.\theta_{n} } \right\}\). The set \(\Theta\) of all possible propositions in is \(2^{\Theta }\) (\(2^{\Theta }\) is the power set of \(\Theta\)). The BPA function m: \(2^{\Theta } \to [0,1][0,1]\) is defined as satisfying the condition21:

where m(A) represents the BPA to proposition A, where the BPA to the recognition framework is denoted as \(m(\Theta )\), and the \(\emptyset\) is symbolized as null.

To effectively fuse the multi-source risk evaluation indicators of foundation excavation and accurately assess the risk probability, it is necessary to adopt the D–S evidence theory to construct a set of quality functions and use the D–S fusion rule to deeply integrate the multi-source risk evaluation indicators, as shown below10.

where B is proposition in the set 2Θ, An is proposition in the discriminating frame Θ, the BPA of assigning the evidence pn to proposition An, and the final result is the combined probability mass of the proposition B obtained by integrating n pieces of evidence.

Step 2: Detection and fusion of conflicting evidence.

In the process of data fusion, this study places particular emphasis on the constraint of data consistency. This constraint emphasizes that information between different data sources or data tables must remain consistent to avoid data conflicts and contradictions, thereby ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the assessment. If K = 1, it indicates that the two evidence are in conflict and cannot be directly fused. Evidence substitution is required before fusion. First, the weight of the evidence should be determined, and then the weighted average of the evidence should be used as the new evidence to replace the conflicting evidence.

First, based on the properties of BPA and its related focus elements in multi-source evaluation indicators evidence, the Euclidean distance can be used to compute the distance dij between two conflicting pieces of evidence40.

The similarity measure between conflicting evidence can be expressed as Sim (mi, mj):

The degree of support for the evidence is defined as Sup(mi), which is equal to:

The normalized value of the support degree of the evidence body mi is taken as the weight of the evidence body mi, that is18:

Next, the conflicting evidence was replaced with the average weighted evidence based on the weighted calculation of the evidence.

The conflict test is repeated until the two evidence do not conflict, and then fusion is performed according to Eq. (8).

Results

Description of the case

The dimensions of the deep foundation excavation for the metro station are approximately 219.5 m in length, 23.3 m in width, and 24.75 m in depth. The support system of the foundation incorporates an interlocking pile and an internal support mechanism. The dimensions of the interlocking pile are Φ1200@900, with the first and second sequence piles arranged in a staggered and interlocked fashion, having an interlocking thickness of 300 mm. The first sequence pile consists of ultra-retardant C20 concrete, whereas the second is a reinforced concrete pile with embedded circular steel cages. The materials employed are C35 and Q235. The standard section of the foundation employs four internal supports, with occasional support replacement. The initial support is made of reinforced concrete, while the second through fourth supports are steel supports with a diameter of 609 mm and a wall thickness of 16 mm. Figure 3 depicts the structural section of the foundation.

Over-excavation is strictly prohibited. Five supports are sequentially established in the simulation. The key construction steps consist of eleven construction phases, with specific stages and excavation depths detailed in Table 1.

The engineering geology and hydrogeology details are as follows: The standard cross-sectional foundation depth of the station is set at 25.1 m. The soil stratigraphy comprises 6.0 m of plain fill, followed by 15.0 m of completely weathered slate, and underneath, 15.0 m of moderately weathered slate, with localized intrusions of diabase within the 1–5 axial range. The station’s surface is primarily located on the layer of moderately weathered slate. Groundwater exploration reveals that the burial depth ranges from 1.6 to 2.3 m, while the water level elevation falls between 1.4 and 3.1 m. The geological conditions at this engineering site are quite complex. In its natural state, the soil exhibits adequate physical and mechanical properties, yet its engineering performance is suboptimal, making it susceptible to deformation and collapse under disturbance. Specific soil parameters are detailed in Table 2. During the soil parameter configuration phase of numerical simulation, this study set various soil parameters based on the investigation report, industry standards, and historical data. Specifically, for plain fill soil, considering its loose structure and high compressibility, this study set the dilation angle to 0° to ensure that the model accurately reflects its deformation behavior. Meanwhile, for completely weathered slate, strongly weathered slate, and medium weathered slate, due to their common occurrence in enclosed geological formations with limited drainage conditions, the drainage type was uniformly set to undrained. Additionally, for the sake of simulation accuracy, the dilation angles of these rocks were also set to 0°.

Given the interlocking pile’s diameter of 1200 mm and a spacing of 900 mm, an equivalent thickness of 930 mm was derived. Material parameters pertinent to the supporting structure, sourced from the project data, can be accessed in Table 3.

Risks posed by structures near the foundation are outlined. The architectural designs of the structures surrounding the foundation are intricate. To the west of the foundation, there are three structures with shallow foundations, introducing potential risks for uneven foundation settlement and subsequent wall cracking. In contrast, the eastern side borders a rail bridge pier, introducing a unique risk of excessive pile settlement and structural cracking. Figure 4 visually presents the foundation and nearby structures, including Hotel A, Hotel B, Hotel C, the railroad station, the bridge pier, and the parking lot.

Hotels A, B, and C are seven-story buildings made of brick and concrete, founded on shallow bases. Their respective proximities to the main structure are 4.6, 16.2, and 20.1 m. The Railroad Station is a two-story frame structure with a pile foundation located 20.1 m from the primary structure. The dimensions of the bridge pier are 1.8 m by 3.0 m with a base elevation of − 17.4 m and a proximity of 3.9 m to the main structure. The parking lot is a three-story frame building with a bidirectional floor slab and a pile foundation, positioned 25.7 m from the main structure.

Results of multi-source evaluation indicators database creation

Results of project database

After deep learning and analysis of geological survey data and construction plans for the foundation project, this study has selected friction angle and soil weight as key evaluation indicators. A project database has been established to quantify geotechnical construction works’ grading during different stages. The engineering properties of soil play a decisive role in the stability of earthworks, the selection of construction methods, and the assessment of work volumes. They are also closely related to the planning of engineering design, construction techniques, and construction organization.

The stratum of the foundation engineering project involved in this study encompasses plain fill, moderately weathered slate, strongly weathered slate, and completely weathered slate. Among them, plain fill exhibits a loose to slightly dense state and engineering geological characteristics, typically utilizing mechanical excavation methods. The completely weathered slate appears as soil-like material with extremely developed weathering joints and fissures, belonging to the category of hard soil in geotechnical engineering, and is also excavated mechanically. Strongly weathered slate exhibits characteristics of fissure development and crushed rock structure, classified as soft rock in geotechnical engineering, with excavation methods combining mechanical and partial blasting. Medium weathered slate, with its relatively hard-to-tough rock characteristics, developed fissures, and sub-hard-to-hard rock geotechnical construction engineering classification, typically employs blasting for excavation.

The frictional resistance between soil particles encompasses friction and bite force. These forces can be quantified uniformly through the internal friction angle. A larger internal friction angle indicates increased frictional resistance, resulting in greater difficulty in soil excavation.

The weight of soil per unit volume in its natural state, known as soil bulk density, has a direct impact on the ease of construction. Higher bulk density corresponds to increased excavation difficulty. Detailed information values for the two evaluation indices of cohesion and soil weight during foundation excavation at different construction stages are presented in Table 4 and Fig. 5 of this study.

Results of numerical database

The 3D FE numerical simulation has dimensions of approximately 415 m in length, 230 m in width, and 65 m in depth. After numerous attempts, the best grid quality was achieved when the mesh was classified as ‘hexahedral’ and the mesh density was set to ‘medium’. This simulation comprises 318,553 soil units and 475,658 nodes. The surface of the simulation remains unconstrained, with the normal and tangential directions at the base being constrained. The surrounding normal directions of the simulation are constrained, but the tangential directions are not. Impermeable boundaries surround the bottom of this numerical simulation41. In this study, the equivalent load arrangements for structures adjacent to the foundation are as follows: a load of 200 kN/m2 represents buildings ranging from seven to ten stories; 80 kN/m2 represents each adjacent railway bridge pier; 100 kN/m2 stands for the adjacent parking lot, and another 100 kN/m2 represents the railroad station. The 3D FE numerical simulation is depicted in Fig. 6.

Given the intricate relationship among surface settlement, horizontal displacement of the retaining pile, and the degree of bottom uplift deformation, this study selected these three evaluation indicators to assess the risk of the foundation excavation.

(1) Results analysis of surface settlement

The deformation grid and surface settlement cloud of the foundation after the excavation is depicted in Fig. 7. In addition, the foundation excavation induces deformation in neighboring structures. When structures exhibit similar designs, their proximity to the foundation directly correlates with the impact magnitude. The stability of the foundation excavation is further influenced by its intricate environmental context. The excavation of the foundation created a free face, releasing the vertical load and thus disrupting the equilibrium of the stress state. This disruption leads to an increase in the bottom uplift of the foundation. Table 5 illustrates the peak surface settlement across various construction phases.

The soil deformation region presents a distinct circular slip surface, while the outer soil deformation zone showcases an elliptical parabolic distribution. Excavation affects the surrounding area, roughly equating to two to three times the depth of the foundation. This is due to the sidewall of the foundation bearing, the influence of water and soil pressure, the thrust from the height differential of excavation, and the additional load from soil sliding on the circular surface. These combined effects induce a plastic region in the soil, resulting in external soil movement toward the foundation.

The 3D FE numerical simulation results provide insights into surface settlements at diverse distances from the foundation across varied construction stages. This surface settlement deformation is presented in Fig. 8.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, as excavation depth augments, there is a corresponding expansion in surface settlement. Moreover, surface settlement fluctuations exhibit a flute-like pattern with varying distances from the foundation. That is, in the immediate vicinity of the foundation edge, the settlement is relatively small; as the distance between the measurement point and the foundation edge gradually increases, the settlement also increases accordingly. When the distance between the measurement point and the foundation edge reaches approximately 15 m, the settlement reaches its maximum value. Subsequently, as the distance further increases, the trend of settlement increase gradually slows down. To put more clearly, the settlement peaks upon the completion of the foundation excavation, registering at − 12.18 mm and located 15 m from the foundation. This pattern aligns with the Xm = (0.5–0.7) × h0 deformation law outlined in the Foundation Engineering Manual42.

With progressive foundation excavation, the settlement demonstrates an upward trend between 0 and 15 m, with an accelerated rate of increase. Between 15 and 60 m, the settlement and its rate of change diminish. For areas spanning 0–15 m, heightened vigilance regarding surface safety is paramount, necessitating enhanced preventive and control measures.

(2) Results analysis of retaining pile horizontal displacement

The design rationale behind the retaining structure was assessed through the horizontal displacement of the retaining pile. Simultaneously, the safety and stability of the primary foundation structure were determined by analyzing whether the horizontal displacement of the retaining structure attained warning or control values. Figure 9 illustrates the horizontal displacement distribution of the retaining pile.

In the preliminary phase of foundation excavation, horizontal displacement of the retaining pile emerged at the apex of the pile. Upon the erection of support, the support and the retaining pile collaboratively countered the soil force, resulting in irregular displacement. The displacement at the corner of the retaining pile was minimal, whereas the displacement of the retaining pile aligned with the building and bridge piles, both centrally and peripherally, was more conspicuous. As excavation proceeded, the horizontal displacement of the retaining pile progressively intensified, broadening its influence. Table 6 presents the maximum horizontal displacement of the retaining pile.

Thus, monitoring the initial displacement rate of the foundation excavation is essential to preclude excessively rapid deformation that can become unmanageable, potentially leading to foundation mishaps. Horizontal displacement simulation values for the retaining structure, spanning from the corner to the center of the foundation, were recorded, extracting one value every 10 m. The Fig. 10a, b, c, d, e depict the horizontal displacement curves for different excavation stages. Using section B of the retaining pile as a representative, the horizontal displacements at various foundation excavation depths during different construction phases were juxtaposed, as shown in Fig. 10f.

In general, it was observed, upon comprehensively analyzing the displacement of the retaining pile at each construction stage, that the displacement of the retaining pile near the internal support is minimal. The internal support effectively mitigated the horizontal displacement induced by the foundation excavation. As the excavation construction progressed, the maximum horizontal displacement gradually migrated to the lower retaining pile part. Besides, the maximum value was located in the interval between the second and third steel supports, at a depth of approximately 10 m, representing about two-fifths of the foundation depth.

When the excavation reached the second soil layer, the horizontal displacement rate of the retaining pile decelerated. However, from the second to the fourth soil excavation layer, the horizontal displacement rate of the retaining pile accelerated significantly. This can be attributed to the extended interval between the erection of the two supports, prolonged exposure of the foundation, and the increased horizontal displacement rate of the retaining pile. Consequently, it is important to consider the space–time effect of foundation excavation and augment the number of internal supports to curtail the interval time of each excavation and their depth in each layer. These methods can effectively control the foundation deformation. In the early foundation excavation stage, when the internal support had not yet been erected, the excavated soil of the foundation was unloaded, leading to horizontal displacement in the foundation of the retaining pile, with the maximum displacement generated at the top of the retaining pile.

The horizontal displacement of the retaining pile underwent significant changes during the third construction stage due to the foundation excavation, which involved changing the soil layer and modulus at the interface. The horizontal displacement of the retaining pile diminished with the increase in the excavation depth and the internal support erection. The location of the support of the retaining pile exhibited a convergence trend, indicating that the support erection is pivotal in limiting the horizontal displacement of the retaining pile. Therefore, with the excavation of the foundation, the retaining pile remained stable.

(3) Results analysis of bottom uplift

Indeed, bottom uplift is a significant characteristic of excavation deformation, primarily induced by the unloading of soil on the excavation surface of a foundation. This uplift acts as a primary catalyst for the movement of the surrounding strata caused by foundation excavation. Figure 11 shows the cloud distribution of bottom uplift during foundation excavation.

In the initial foundation excavation stages, soil deformation within the foundation was effectively minimized, a phenomenon attributed to the increased rigidity resulting from the combined effect of the retaining pile and internal support. However, as excavation depth increased, the lateral earth pressure on the retaining structure also underwent a corresponding increase. Simultaneously, the presence of bottom uplift became more apparent. Alongside these changes, a significant plastic region developed near the foundation, leading to surface settlement deformation. The peak bottom uplift for each construction phase is detailed in Table 7. Figure 12 graphically presents the evolution of maximum bottom uplift in relation to foundation excavation.

As the foundation’s excavation depth grew, the difference in soil surface height inside and outside the foundation also increased. Figure 12 demonstrates that the rate of change peaks when the fourth soil layer is excavated. Upon the excavation completion, the rate of change in soil elevation began to stabilize.

Risk classification of multi-source evaluation indicators

To understand the combined effects of multi-source evaluation indicators and to quantitatively assess the risk early warning classification of foundation excavation, an analysis of the risk early warning threshold was undertaken. The risk early warning and control values for five evaluation indicators were derived from metro design specifications and pertinent literature and then adjusted based on the specific context of subway station engineering4,43, as depicted in Table 8.

Based on the specific requirements of engineering practice and the surrounding environment, this study thoroughly consulted authoritative literature on subway design specifications and related fields, and closely integrated the actual conditions of subway station projects (including but not limited to geological conditions, construction environments, and protection requirements for existing buildings). Through this comprehensive approach, reasonable ranges for early-warning values and control values were clearly defined for key safety control parameters. To further enhance the scientific nature of risk assessment and management, this study adopted Heinrich’s accident classification principle, subdividing the risk levels within the monitoring indicator thresholds into four categories: severe warning, moderate warning, mild warning, and normal state. Table 9 illustrates the threshold classification for each evaluation indicator.

Results of multi-source evaluation indicators data fusion

Results of BPA of multi-source evaluation indicators

To comprehensively assess the overall risk status of the foundation, three multi-source evaluation indicators related to the risk of the foundation excavation are selected, and the CM in the D–S evidence theory is used to fuse these indicators. Based on the project database and numerical database, a risk assessment CM is constructed as shown in Table 10. The cloud diagram of the assessment degree of the foundation excavation risk indicators is shown in Fig. 13.

Result of multi-source evaluation indicators data fusion

Based on the numerical evidence database after excavation of the foundation, the evaluation indicators of surface settlement, horizontal displacement of the retaining pile, and the bottom uplift are used as the multi-source evaluation indicators of risks in the foundation. According to the distribution of risks in the foundation and the surrounding environment, eight risk sections are selected to extract the selected evaluation indicators data as evidence bodies, as shown in Fig. 14. Take indicator E3 as an example of information fusion. The level cloud assessment set corresponding to the indicators has been determined by the CM, and the BPA for each evaluation indicator has been calculated to establish an initial reliability allocation, as shown in Table 11.

The BPA for evaluation indicator E3 is used to perform conflict detection and then to fuse the body of evidence according to the fusion rule. Similarly, the fusion results for other evaluation indicators can be obtained, as shown in Table 12.

To construct a BPA distribution of the risk status at each stage of foundation excavation, using various indicators as evidence, and then fusing the evidence theory to obtain the risk status at each stage of foundation excavation. The calculation results are shown in Table 13.

The risk status of each stage of foundation excavation can be obtained from the fusion results of the five sets of evidence bodies in Table 13. For example, the risk level membership vector at the completion of foundation excavation is (0.176, 0.000, 0.234, 0.428) with an uncertainty of 0.162, indicating that the fusion decision-making process has a high degree of certainty. The overall risk level membership vector T (0.016, 0.103, 0.167, 0.644) of the foundation, m(IV)-m(Θ) = 0.624 > 0.5, meets the requirements of the decision-making criteria, and the overall risk level of the assessed road section can be determined as Level IV, “Normal”.

Discussion

Enhancing the quality of multi-source databases and the effectiveness of fusion evaluation can improve the accuracy and reliability of risk assessment through mining. On the one hand, this study places significant emphasis on the reliability of the input data for the model, with the accuracy of numerical simulations being a pivotal factor influencing data reliability. To this end, the study conducts a detailed comparison between the simulation outputs from numerical simulations and actual measurements, assessing the precision of the numerical simulations by quantifying the differences between the two. On the other hand, this study also focuses on the effectiveness of data fusion. The accuracy of evaluation results directly influences the application value of the model, and the effectiveness of methods for fusing multi-source data is a core factor affecting the reliability of evaluation results44,45. To validate this, the study compares the proposed method for fusing multi-source evidence bodies with other commonly used methods. Therefore, this study primarily revolves around these two points: the efficacy of 3D FE numerical simulation was confirmed in Section “Performance verification of multi-source data acquisition based on 3D FE”, and the effectiveness of CM and D–S evidence theory multi-source evaluation indicators fusion was substantiated in Section “Performance verification of multi-source information fusion based on CM and D–S evidence theory”.

Performance verification of multi-source data acquisition based on 3D FE

During the process of model development and optimization, this study conducted a sensitivity analysis, relying on indicators such as mesh quality and model output results, to investigate the degree of influence that various input parameters have on model output. Based on these findings, adjustments were made to the parameter settings, ultimately leading to the derivation of the optimal model results. To thoroughly verify the accuracy and practical application value of the numerical simulation results, this study further conducted a comparative analysis between the 3D FE numerical simulation results and the measured data obtained during the construction process, thereby effectively validating the reliability and practicality of the numerical simulation.

Verification by surface settlement

The standard section of the station foundation was selected for simulation, and the midpoint on the longer side of the foundation was isolated. Besides, the surface settlements of statistical points within a 0–60 m range from the edge of the foundation, spaced every 10 m, were analyzed at different excavation depths. This assessment considered the surface settlements at distances of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 m from the excavation boundary and compared them to real-world monitoring points. The resulting data was then visualized in Fig. 15.

The trends observed in the numerical simulation results closely aligned with the measured outcomes. Nevertheless, the simulated values were typically smaller than their measured counterparts. As the excavation depth of the foundation deepened, both the simulated and measured values adhered to a parabolic concave variation. Specifically, the settlement value first increased with the increase in distance from the foundation and later decreased as this distance extended. The maximum surface settlement, observed in both the simulation and measured outcomes, was determined as 15–20 m from the foundation. The simulated maximum settlement was − 22.3 mm, while the measured counterpart was − 19.6 mm. These observations suggest that the foundation remained relatively stable during excavation and stayed within the control of theoretical predictions. Differences between the 3D FE numerical simulations and the actual measurements might stem from the oversimplified nature. Factors like the idealization of the formation level, the assumption of a constant soil stress field, and the intricate nature of the real-world project could have influenced the results.

Verification by retaining pile horizontal displacement

Taking point E as an example, the horizontal displacement of both the simulated and measured retaining pile at varying depths across each construction phase is depicted in Fig. 16.

The patterns in horizontal displacement between the simulated and measured retaining piles were similar, with the most significant displacement occurring between depths of 10 and 12 m. Within each phase, the displacement showcased an inflection point at the location of internal support, signifying its role in efficiently managing foundation deformation. Moreover, the simulated values never surpassed the set warning thresholds and followed a similar deformation progression. This consistency underscores the viability and dependability of the 3D FE numerical simulations for comprehensive stability analysis during foundation excavation. Discrepancies between the simulation and measurements can be attributed to multifaceted factors inherent in the actual construction process. Externalities such as vehicular and pedestrian traffic, temporary loads, weather conditions, and more impact the deformation state of the retaining structure. These factors, however, were not entirely integrated into the 3D FE simulation but were idealized.

Verification by bottom uplift

The simulated values of the bottom uplift at each construction stage were extracted and compared with the measured values. The simulated and measured bottom uplift results at each construction stage were compared and analyzed, as shown in Fig. 17.

The simulated and measured bottom uplift development laws were similar. With the foundation excavation, the fluctuation in the bottom uplift increased. When the construction was approaching completion, the bottom uplift was gradually stabilized. While the simulated and measured results were largely similar, multiple deviations occurred. The simulated uplift was marginally larger than the measured data when factoring in construction conditions. The underlying reasons for discrepancies between the 3D FE numerical simulation and measurements encompass variability in on-site support parameters, effects of fatigue, and the influence of construction machinery and materials on foundational loads.

Performance verification of multi-source information fusion based on CM and D–S evidence theory

Weighted evidence fusion and D–S evidence fusion are two of the most commonly used and widely applicable methods for evidence fusion. The weighted evidence fusion method achieves effective integration of evidence by assigning weights to different evidence sources. These weights are typically allocated based on factors such as the reliability, accuracy, or information content of the evidence sources, allowing the method to demonstrate flexibility when dealing with evidence sources that exhibit significant variations. However, compared to weighted evidence fusion, D–S evidence fusion exhibits unique advantages in handling complex and uncertain problems. The D–S evidence theory provides a solid mathematical framework for incomplete information and conflicting evidence by defining belief and plausibility functions. Its unique combination rule allows for the fusion of evidence from different and potentially conflicting sources, generating a comprehensive belief distribution that supports more comprehensive decision-making. To validate the effectiveness and advantages of D–S evidence fusion in the context of this research topic, a comparison was further conducted between the proposed method and a weighted evidence theory based on consistency CM. Due to the identical evaluation indicator characteristic parameters, this comparison ensured consistency in experimental conditions, making the results more comparable. Taking the excavation completion stage of the foundation as an example, the results are shown in Table 14. The risk assessment results of each stage of excavation of the foundation and the whole foundation are shown in Table 15.

The results of Tables 14 and 15 show that the method proposed in this study is superior to the linear weighted method in the fusion process, and the weighted evidence method has certain conflicts in data fusion. For example, once the excavation of the foundation is completed, the fusion result obtained from this study is 0.162, whereas the fusion result derived from the weighted evidence method is 0.302. In comparison, the method proposed in this study exhibits less conflict and uncertainty, and is capable of achieving more favorable and ideal risk assessment results. This validates the feasibility of our method to a certain extent.

Conclusion

This study proposes a risk assessment method for the excavation of a foundation that combines the Complementary Method CM and D–S evidence theory and tests it through a case study of a narrow and elongated foundation project. Firstly, data is extracted from geological survey documents, construction drawings, design schemes, and other project information, as well as from 3D FE numerical results, to establish project and numerical databases. Subsequently, based on these databases, CM and D–S evidence theories are utilized to fuse multi-source evaluation indicators, identify potential risks in the foundation, and comprehensively assess the potential risks and severity of accidents. The results indicate that throughout the excavation process, the comprehensive risk level for foundation pit excavation is Grade IV (normal), suggesting that the structural design of the foundation is reasonable and the construction scheme is feasible. In the process of fusing multi-source risk information for foundation excavation, as uncertain data is continuously incorporated, the randomness and error of the evaluation results gradually decrease. Furthermore, verification of numerical simulation results demonstrates that the deformation evolution simulated by 3D FE aligns with actual engineering conditions, further validating the reliability and accuracy of the numerical database. Compared with the weighted evidence theory based on consistent CM, the multi-source data fusion method integrating CM and D–S evidence theory exhibits higher feasibility and effectiveness. Therefore, the proposed method is capable of providing a more accurate assessment of the feasibility and design rationality of foundation excavation projects at the pre-excavation stage.

While the quantitative method demonstrates notable precision in classifying foundation excavation risks, several limitations require further attention in the future. First, constrained by the limited data availability during the pre-excavation phase, the characteristics of the obtained multi-source data, particularly their uncertainty, remain to be further explored. Second, to achieve real-time online risk early warning and assessment for foundation excavation, considering the time-dependency of excavation parameters, it is necessary to integrate this model with the Internet of Things (IoT) technology, a process that could be labor-intensive.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yi, F. et al. Overturning progressive collapse mechanism and control methods of excavations retained by cantilever piles. Eng. Fail. Anal. 140, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106591 (2022).

Zhang, J., Xie, R. & Zhang, H. Mechanical response analysis of the buried pipeline due to adjacent foundation pit excavation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 78, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.04.026 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Rapid safety monitoring and analysis of foundation pit construction using unmanned aerial vehicle images. Autom. Constr. 128, 103706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103706 (2021).

Ye, S., Zhao, Z. & Wang, D. Deformation analysis and safety assessment of existing metro tunnels affected by excavation of a foundation pit. Undergr. Space 6, 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2020.06.002 (2021).

Ye, Z., Hsu, S. C. & Wei, H. H. Real-time prediction of structural fire responses: A finite element-based machine-learning approach. Autom. Constr. 136, 104165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104165 (2022).

Ursini, A., Grazzini, A., Matrone, F. & Zerbinatti, M. From scan-to-BIM to a structural finite elements model of built heritage for dynamic simulation. Autom. Constr. 142, 104518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104518 (2022).

Okasha, N. M., Frangopol, D. M. & Orcesi, A. D. Automated finite element updating using strain data for the lifetime reliability assessment of bridges. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 99, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2011.11.007 (2012).

Fang, X. et al. A combined finite element and deep learning network for structural dynamic response estimation on concrete gravity dam subjected to blast loads. Def. Technol. 24, 298–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2022.04.012 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Su, W., Ding, L., Luo, H. & Love, P. E. D. Predicting safety risks in deep foundation pits in subway infrastructure projects: Support vector machine approach. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 31, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)cp.1943-5487.0000700 (2017).

Zhou, H. et al. Weighted average selective ensemble strategy of deep convolutional models based on grey wolf optimizer and its application in rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Expert. Syst. Appl. 234, 121076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121076 (2023).

Peng, Z., Wang, Z., Yin, H., Bai, Y. & Dong, K. A new Bayesian finite element model updating method based on information fusion of multi-source Markov chains. J. Sound. Vib. 526, 116811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2022.116811 (2022).

Tian, Q., Shen, W., Wang, Y. & Liu, L. Mechanism and evolution trend of digital green fusion in China’s regional advanced manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 427, 116811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2022.116811 (2023).

Fu, X. & Zhang, L. Spatio-temporal feature fusion for real-time prediction of TBM operating parameters: A deep learning approach. Autom. Constr. 132, 103937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103937 (2021).

Guo, K. & Zhang, L. Multi-source information fusion for safety risk assessment in underground tunnels. Knowl. Based. Syst. 227, 107210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107210 (2021).

Zhou, Z., Liu, S. & Qi, H. Mitigating subway construction collapse risk using Bayesian network modeling. Autom. Constr. 143, 104541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104541 (2022).

Ali, R., Chuah, J. H., Talip, M. S. A., Mokhtar, N. & Shoaib, M. A. Structural crack detection using deep convolutional neural networks. Autom. Constr. 133, 103989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103989 (2022).

Phoon, K. K. et al. Geotechnical uncertainty, modeling, and decision making. Soils Found. 62, 101189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2022.101189 (2022).

Jing, Y., Pan, Y., Yang, F., Wei, D. & Wang, W. Comprehensive risk assessment for the esterification processes based on Dempster–Shafer evidence theory and cloud model. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 87, 105213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2023.105213 (2024).

Chen, A., Tang, X., Cheng, B. C. & He, J. P. Multi-source monitoring information fusion method for dam health diagnosis based on Wasserstein distance. Inf. Sci. 632, 378–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2023.03.053 (2023).

Li, B. et al. Optimize the early warning time of coal and gas outburst by multi-source information fusion method during the tunneling process. Process Saf. Environl. 149, 839–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2021.03.029 (2021).

Zhang, Q., Babanajad, S., Ho Ro, S., Braley, J. & Alavi, A. H. Multi-resource fusion of nondestructive evaluation data for bridge deck assessment using discrete wavelet transform and Dempster–Shafer theory. Measurement 220, 113303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113303 (2023).

Guo, K. & Zhang, L. Multi-source information fusion for safety risk assessment in underground tunnels. Knowl. Based Syst. 227, 107210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2021.107210 (2021).

Wen, X., Nie, Y., Du, Z. & Huang, L. Operational safety assessment of straddle-type monorail vehicle system based on cloud model and improved CRITIC method. Eng. Fail. Anal. 139, 106463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106463 (2022).

Wang, H. L. et al. Evaluation of toppling rock slopes using a composite cloud model with DEMATEL–CRITIC method. Water Sci. Eng. 16, 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wse.2023.04.002 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. A cloud model-based interval-valued evidence fusion method and its application in fault diagnosis. Inf. Sci. 658, 119995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2023.119995 (2024).

Feng, D. C., Wu, G. & Lu, Y. Finite element modelling approach for precast reinforced concrete beam-to-column connections under cyclic loading. Eng. Struct. 174, 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.07.055 (2018).

Ding, Z., Feng, D. C., Ren, X. & Wang, J. Physically based constitutive modeling of concrete fatigue and practical numerical method for cyclic loading simulation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 101, 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2019.03.020 (2019).

Feng, D. C., Shi, H. R., Parisi, F., Brunesi, E. & Wang, C. L. Efficient numerical model for progressive collapse analysis of prestressed concrete frame structures. Eng. Fail. Anal. 129, 105683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105683 (2021).

Wang, X., Wang, S., Peng, X., Ma, T. & Chen, B. Equivalent numerical simulation method and application in karst-induced collapse of overlying sandy stratum. Eng. Fail. Anal. 137, 106280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106280 (2022).

Ghaderi, A., Abbaszadeh Shahri, A. & Larsson, S. An artificial neural network based model to predict spatial soil type distribution using piezocone penetration test data (CPTu). Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 4579–4588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-018-1400-9 (2019).

Ghaderi, A., Abbaszadeh Shahri, A. & Larsson, S. A visualized hybrid intelligent model to delineate Swedish fine-grained soil layers using clay sensitivity. Catena 214, 106289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2022.106289 (2022).

Saltelli, A. et al. Why so many published sensitivity analyses are false: A systematic review of sensitivity analysis practices. Environ. Model. Softw. 114, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2019.01.012 (2019).

Yang, T. et al. Numerical analysis of the influence of deep foundation pit construction on adjacent subway stations in soft soil areas. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 6071868. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6071868 (2022).

Feng, J. C., Huang, H. A., Yin, Y. & Zhang, K. Comprehensive security risk factor identification for small reservoirs with heterogeneous data based on grey relational analysis model. Water. Sci. Eng. 12, 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wse.2019.12.009 (2019).

Skeji, A. & Bali, A. Case history on excessively large displacements and remediation of pile-supported excavation in a sloping ground. Eng. Fail. Anal. 143, 106856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106856 (2022).

Li, M. G., Xiao, X., Wang, J. H. & Chen, J. J. Numerical study on responses of an existing metro line to staged deep excavations. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 85, 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.12.005 (2019).

Hsiung, B. C. B., Yang, K. H., Aila, W. & Hung, C. Three-dimensional effects of a deep excavation on wall deflections in loose to medium dense sands. Comput. Geotech. 80, 138–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2016.07.001 (2016).

Zhao, J. et al. Deformation responses of the foundation pit construction of the urban metro station: A case study in Xiamen. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 128, 104662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104662 (2022).

Wang, X., Fang, H. & Fang, S. An integrated approach for exploitation block selection of shale gas—based on cloud model and grey relational analysis. Resour. Policy 68, 101797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101797 (2020).

Pan, L., Gao, X. & Deng, Y. A distance of quantum mass function and its application in multi-source information fusion method based on discount coefficient. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 116, 105407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105407 (2022).

Zeng, C. F., Xue, X. L. & Li, M. K. Use of cross wall to restrict enclosure movement during dewatering inside a metro pit before soil excavation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 112, 103909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.103909 (2021).

Feng, T., Wang, C., Zhang, J., Zhou, K. & Qiao, G. Prediction of stratum deformation during the excavation of a foundation pit in composite formation based on the artificial bee colony–back-propagation model. Eng. Optim. 54, 1217–1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305215X.2021.1919100 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Response analysis of deep foundation excavation and dewatering on surface settlements. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 8855839. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8855839 (2020).

Wu, B. et al. A multi-source information fusion approach in tunnel collapse risk analysis based on improved Dempster–Shafer evidence theory. Sci. Rep. 12, 3626. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07171-x (2022).

Wu, B. et al. A collapse risk assessment method for subway foundation pit based on cloud model and improved Dempster–Shafer evidence theory. Sci. Rep. 14, 2653. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52643-x (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yue An: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-original Draft. Liuyang Li: Data curation, Supervision, Writing-review & editing. Haoyuan Gao: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing-review & editing. Zhihao Luo: Software, Writing-review & editing. Yuefang He: Validation, Writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, Y., Li, L., Gao, H. et al. Fusing multiple source data for foundation excavation risk assessment based on cloud model and Dempster Shafer evidence theory. Sci Rep 15, 9894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94628-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94628-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhancing urban quality of life evaluation using spatial multi criteria analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)