Abstract

Neonatal omphalitis is a true medical emergency that can rapidly progress to sepsis and even death if not promptly diagnosed and treated appropriately. Empirical therapy is widely practised in this case, too, in low-income countries like Ethiopia, paving the way for severe drug resistance and posing serious challenges. To determine the magnitude, bacterial profile, antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and associated factors of omphalitis among clinically suspected neonates attending four government health institutions in Arba Minch, southern Ethiopia, during the second half of 2023. A facility-based multi-centred cross-sectional study was conducted among 379 clinically suspected neonates who attended the inpatient/outpatient departments and intensive care units of four government health institutes of Arba Minch from June 1 to December 28, 2023. Study participants were consecutively recruited, and their demographic and clinical data were collected using a pre-tested questionnaire. Samples were aseptically collected and inoculated onto a series of bacterial culture media, namely MacConkey agar, mannitol salt agar, chocolate, and blood agar, and different species were identified by means of several biochemical tests. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed through the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion technique. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression models (SPSS version 25) were utilized to analyze the association between dependent and independent variables; P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The overall number of clinically suspected and culture-confirmed cases of omphalitis, respectively, were 379 and 130 per 1000 live births. Gram-positive (GPB) and Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) were detected in 50.4% (n = 71) and 49.6% (n = 70) of cases, respectively. The often isolated bacteria were S. aureus, 53.5% (n = 38), and E. coli, 47.1% (n = 33); GNB were highly resistant (> 60%) to tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ampicillin. The overall multi-drug resistance was 34.7% (n = 49); methicillin-resistant S. aureus was 34.1% (n = 14). The GNB isolates comprised extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, 15.7% (n = 11), and carbapenemase, 10% (n = 7) producers. The lack of hand washing practices [AOR = 2.08, (95% CI 1.26–3.41), P value = 0.004] and lower gestation period (< 37 weeks) [AOR = 2.3, (95% CI 1.33–3.93), P value = 0.003] were statistically associated. The overall prevalence of omphalitis was higher; WHO-prioritised drug-resistant bacterial pathogens were also detected. This study underscores the importance of factors such as maternal/caregiver hand hygiene and antenatal care. Thus, a more comprehensive approach towards the management of omphalitis employing precise diagnostic tools and an antimicrobial stewardship program is essential in all the four study settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Omphalitis or umbilical cord infection is defined as the presence of any purulent discharge, redness, and swelling around the umbilicus or surrounding tissues occurring primarily during the neonatal period1. Omphalitis in neonates is a true medical emergency, with an estimated mortality rate between 7% and 15%2. It is a pressing problem in developing countries3 where the routine care of umbilical cord stump still involves the application of potentially dangerous substances, contrary to the cord care recommendations issued by WHO4.

Omphalitis is usually caused by exogenous bacteria that enter either during the perinatal or postnatal period. Potential pathogenic bacteria that cause omphalitis include S. aureus, S. epidermis, Streptococcus sp., Enterococci sp., and members of Enterobacteriaceae, viz., E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Citrobacter sp., Enterobacter sp., and P. mirabilis and rarely the anaerobic bacteria B. fragilis and C. perfringens5,6,7. These bacteria can be contracted directly from the mother’s blood, skin, or vaginal tract before or during delivery and/or from the environment during and after delivery8. Untreated omphalitis is an essential vessel for local and systemic infections, and it is a patent way that provides direct transfer of bacteria into the bloodstream, eventually leading to sepsis9. There is also a high mortality rate in developing countries (60–85%) caused by omphalitis due to its rapid progression to necrotising fasciitis7,10. However, it can be prevented through early recognition of the signs and symptoms, followed by prompt and aggressive treatment11.

The common risk factors associated with the development of omphalitis include gestation period, septic delivery, low birth weight, prolonged process of membrane rupture, umbilical catheterisation, premature twin delivery, preterm delivery, intrapartum infections, chorioamnionitis, maternal pyrexia, late initiation of breastfeeding, materials used to cut and clean the cord, type of delivery instruments used to ligate and cut the cord, place of antenatal care and delivery and improper cord care, such as the application of home remedies aiming to speed up the cord separation1,11,12.

In Ethiopia, the neonatal mortality rate corresponds to 37 deaths per 1000 live births in recent years13. In several parts of the country, the majority of deliveries occur at home, often under sub-optimal and unhygienic conditions, accounting for 50% of neonatal deaths13. The availability of the latest data on bacterial pathogens, their profile, and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in a particular area may assist physicians in making informed diagnoses and selecting effective antibiotics. However, on reviewing the open literature, we found that there exists a lack of published works from Ethiopia in this context. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of information on the underlying causes of omphalitis as well as the associated factors. In developing countries, neonatal infections due to MDR bacteria are growing, and this has been attributed to the production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), Amp C β-lactamases, carbapenemase and aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes14. This prompted us to design this research, aiming at the estimation of the magnitude of omphalitis, bacteriological profile, antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and associated factors among neonates at Arba Minch General Hospital (AMGH), Dil Fana Primary Hospital (DFPH), Sacha Health Centre (SHC) and Woza Health Centre (WHC).

Materials and methods

Study area, design, and period

This is a facility-based, multi-centred, cross-sectional study conducted simultaneously in four government health institutes in Arba Minch, Ethiopia, mentioned above, from June 1 to December 28, 2023. Arba Minch is the administrative centre of the Gamo zone15.

Study settings

All the four selected study settings provide health services for the entire residents of the Gamo zone; also, in all these settings, many suspected cases of neonatal omphalitis are identified every month, which are usually managed by empirical therapy. Complications such as sepsis are also associated with omphalitis, and approximately a total of 30 deaths are reported annually. Relevant details of the four study settings are appended in the supplementary file 1.

Source and study population

The source population encompasses all neonates aged ≤ 28 days (hospital and home births) who visited any one of the above-listed four health institutes during the study period. However, the study population comprised only the hospital births, treatment naïve (no antibiotics) neonates (3 to 28 days) who attended the inpatient and outpatient paediatric departments and presented with any signs and symptoms of omphalitis.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

All neonates (irrespective of sex) who attended the paediatric departments, at least with any one of the following signs and symptoms suspected of omphalitis, were examined by the paediatricians; the diagnosis was initially based on clinical criteria. The presence of funisitis/ umbilical discharge, omphalitis with abdominal wall cellulitis, omphalitis with fasciitis as well as omphalitis with systemic sepsis were the clinical diagnostic criteria. These criteria were framed in such a way as to cover all types of omphalitis and were set by paediatricians/general practitioners after referring to the relevant literature11. Those who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care units and paediatric inpatient/outpatient wards after the clinical diagnosis were ultimately included in the study. Neonates whose parents and/or caretakers volunteered to participate in the study were only included. In regard to the sampling technique, participants with clinical evidence of omphalitis were consecutively recruited from the respective outpatient and inpatient departments until the calculated final sample size mentioned below was achieved. The selection of neonates from AMGH, DFPH, SHC, and WHC were done by considering the proportional allocation corresponding to each health institute based on the sample size calculated.

Exclusion criteria

Neonates who were critically ill and unable to give samples and those who were on antibiotic therapy during the time of sample collection were excluded from the study.

Sample size

The Epi-Info version 7.2 software was employed to determine the sample size as per the assumptions of a single population proportion formula, which considered a prevalence of 63%, according to a study conducted in neonates in central Uganda16 and the sample size calculated was 361. Finally, by computing a 5% non-response rate, the sample size became 379. As per the proportional allocation, 252, 46, 43, and 38 neonates were selected from AMGH, DFPH, SHC, and WHC, respectively.

Data collection process

Collection of data

The data collection was performed via face-to-face interviews arranged with the parents/caretakers, and the clinical medical records were reviewed after proper assessments. The participants were included in this study based on volition and after obtaining written consent forms. All of them were meticulously examined by paediatricians and trained physicians. The data collection tool employed in this study was a pre-tested questionnaire, which was formulated after thoroughly reviewing the existing literature1,11,12. The questionnaire was translated into Amharic (the native language) and then back-translated to English (supplementary file 2). The data were collected with the aid of senior nurses, and the principal investigator carefully supervised the procedure to ensure the data quality.

Collection, transportation, and handling of umbilical specimens

Sample collection

One-time samples were taken by trained nurses strictly following the contact precautions from the cord-cutaneous junction and the purulent discharge from the umbilicus. The cord swab tip was rotated over a square centimetre area of the deep part of the septic cord stump for 10 s (Levine method); utmost care was taken to avoid touching the stump edge, and in case of the umbilicus with redness and swelling, aspirate samples were collected using sterile needles. The collected samples were put in Amies transport media and sent to the Medical Microbiology and Parasitology Laboratory, Department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, within an hour.

Laboratory investigations

Bacterial isolation and identification

All cord specimens were aseptically inoculated onto a series of culture media: 5% sheep blood agar, chocolate agar, MacConkey agar, and mannitol salt agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, and Hampshire, UK). Isolates were identified phenotypically by examining the colony characteristics (shape, edge, elevation, consistency, density, and colour), Gram staining (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai, India), motility, and also by means of a series of standard biochemical tests17,18,19. The simultaneous growths of two or more species are reported as a ‘poly-bacterial’ infection.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests

The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion technique was employed to inspect the antibiotic susceptibility profiles based on the criteria provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2022 (CLSI)20 and also as per the recommendations of paediatricians. In the case of Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), the antibiotics selected are amino-penicillin (ampicillin, AMP 10 µg), penicillin plus beta-lactamase inhibitor (amoxicillin- clavulanic acid, AMC 30 µg), the second, third and fourth generation cephalosporins (cefoxitin, CXT 30 µg, ceftriaxone, CTR 30 µg, ceftazidime, CAZ 30 µg, and cefotaxime, CTX 30 µg and cefepime, CFP 30 µg), aminoglycosides (gentamicin, GEN 10 µg and amikacin, AMK 10 µg), tetracycline (tetracycline, TET 30 µg), fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, CIP 5 µg), folate pathway inhibitors (sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, SXT 25 µg), whereas for Gram-positive bacteria (GPB), phenicol (chloramphenicol, CHL 30 µg), erythromycin (erythromycin, ERY 15 µg), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, CIP 5 µg), the second-generation cephalosporin (cefoxitin, CXT, 30 µg), penicillin (penicillin, PEN, 10 µg), amino-penicillin (ampicillin, AMP 10 µg), glycol-peptides (vancomycin, VAN 30 µg), folate pathway inhibitors (sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, SXT 25 µg), lincosomide (clindamycin, CLN 300 µg), and carbapenem (meropenem, MER 500 µg) were used; MDR was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more categories of antimicrobials21.

Determination of MRSA, ESBL producing and carbapenem-producing GNB

A methicillin-resistant S. aureus identification test was done in accordance with the criteria of CLSI 2022 using a cefoxitin disk diffusion assay20. Inducible clindamycin resistance was also checked20. Screening the GNB isolates for ESBL production was done according to the guidelines of CLSI20. Phenotypic confirmation of ESBL strains was also done20. Isolates with reduced susceptibility to meropenem, as shown by the disc diffusion method, were considered carbapenem-resistant strains20. The phenotypic determination of carbapenemase producers was done by means of a modified carbapenem inactivation method20.

Quality control

To maintain the quality, standard operating procedures given in an in-house manual were followed during collection (by aseptic technique), transportation, and processing. Before sample processing, the prepared culture media were checked for sterility by incubating 5% of it overnight and examining the presence of growths, if any. The fitness of the media was checked by inoculating the control strains before performing the culture and susceptibility tests. Control slides were also used to check the quality of Gram staining; corresponding American Type Culture Collection strains, such as S. aureus (ATCC 25923) and E. coli (ATCC 25922), were taken as a reference for the quality control-related culture and susceptibility tests. All the reference strains were procured from the Ethiopian Public Health Institute. A pre-test was conducted on 5% of the study participants at Geresa Primary Hospital child health clinic to ensure the quality, and this process did not contribute to the data that were finally analysed.

Results

This study was conducted over a span of seven months between June 1 to December 28, involving four settings. The number of clinically suspected and culture-confirmed cases of omphalitis, respectively, were 379 and 130 per 1000 live births.

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 379 neonates from all four health institutions put together met the inclusion criteria and hence were included in the study, i.e., 66.5% (n = 252) from AMGH, 12% (n = 46) from DFPH, 11.5% (n = 43) from SHC and 10% (n = 38) from WHC, with a response rate of 100%. The majority of mothers, i.e., 54.3% (n = 206), were in the age group of 26–32; rural dwellers and those who completed secondary school education correspond to 44.6% (n = 169) and 43.3% (n = 164), respectively; detailed socio-demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Obstetrics and gynecological factors

A large number of mothers (n = 368) sought antenatal care (ANC) from some government facility, while a mere 2.9% (n = 11) received their ANC from private institutions. Only 11.3% (n = 43) adhered to three or more ANC visits; 20.6% (n = 78) had pyrexia during pregnancy. Nearly 97.6% (n = 370) delivered at government institutions, and 2.4% (n = 9) had their delivery at private health facilities, while 30.3% (n = 115) had a gestation period fewer than 37 weeks; approximately one-third of the participants (34%, n = 129) experienced a rupture of membrane lasting more than 19 h, while 66.2% (n = 251) underwent spontaneous vaginal delivery; most of the women (93.9%, n = 356) did not use any antibiotics during their pregnancy (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of neonates and caregivers

The majority of neonates (61.7%, n = 234) recruited in the study were aged between 6 and 10 days. Approximately 60% of the neonates were females (n = 226). It was found that 50.9% (n = 193) had body weight ranging between 2.6 and 3 kg, and around 7.6% (n = 29) had lower birthweight (≤ 2.5 kg) than required. Only 21.9% (n = 83) of mothers had the habit of washing their hands before doing cord care. In 79.4% (n = 301) of cases, the clamp itself served as cord-tying material; cord separation time was 1–2 min in the case of 81% (n = 307). Approximately 67.5% (n = 256) of caregivers used various substances for cord care, with vaseline being the most popular choice (38.3%, n = 145) (Table 2).

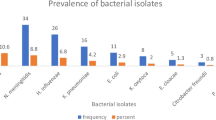

Culture-confirmed cases of bacterial omphalitis

We found that 130 cases were culture-confirmed (out of 379 samples) for bacterial omphalitis, corresponding to 34.3% (95% CI: 29.5–39.3); out of these 130 cases, their observed clinical manifestations like funisitis (56.9%, n = 74), cellulitis (25.4%, n = 33), fasciitis (1.5%, n = 2), and sepsis (16%, n = 21) (Fig. 1).

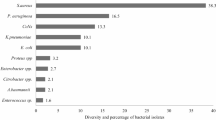

Spectra of omphalitis bacteria

From the 130 culture-confirmed cases of omphalitis, 141 distinct bacterial isolates were obtained. By analyzing the colony morphology, performing Gram staining, and biochemical tests, a total of seven bacterial genera were identified distinctly; four of these genera were classified as GNB, while the remaining were GPB. It is noteworthy that the percentage isolation of GPB and GNB were more or less equal, that is, 50.4% (n = 71) and 49.6% (n = 70), respectively.

Among the GNB (n = 70), E. coli was the predominant one, which corresponds to 47.1% (n = 33), and it is often associated with funisitis (75.7%, n = 25). The second most dominant bacteria were the species of Proteus and Klebsiella (each n = 10); isolates of P. mirabilis and P. vulgaris accounted for 10% (n = 7) and 4.3% (n = 3), respectively. In the case of Klebsiella, 8.6% (n = 6) correspond to K. pneumoniae, and 5.7% (n = 4) were K. oxytoca; isolates of E. aerogenes constituted 8.6% (n = 6).

In the case of GPB (n = 71), S. aureus was the most predominant one (53.5%, n = 38). The isolates of S. pyogenes and E. faecalis accounted for only 9.8% each (n = 7). Bi-bacterial infections were observed only in 11 cases (n = 22) (Table 3).

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of GNB

The susceptibility profiles of GNB (n = 70) against eleven antibiotics are presented in Table 4. In the present study, isolates of GNB showed a distinct but wider range of variations in terms of their susceptibility (41.4–92.8%) as well as resistance (7.2–58.6%). They showed resistance to tetracycline (58.6% n = 41), ceftriaxone (51.4%, n = 36), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (47.1%, n = 33), amoxicillin-clavulanate (44.3%, n = 31), cefotaxime (40%, n = 28), amikacin (37.2% n = 26) and gentamicin (35.7% n = 25). (Table 4).

The predominant species of GNB, E. coli, showed resistance, viz., 59% (n = 23) to tetracycline, 56.4% (n = 22) to ceftriaxone, 46.2% (n = 18) to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim and 41% each (n = 16) to amoxicillin-clavulanate and cefotaxime. The isolates of P. mirabilis demonstrated moderately higher resistance against tetracycline (66.7%, n = 6), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (55.6%, n = 5), and a reduced resistance to ceftriaxone and chloramphenicol each (44.4%, n = 4). The isolates of E. aerogenes in this study were resistant to penicillin, ampicillin (each 71.4% n = 5), and cloxacillin (57.1%, n = 4) (Table 4).

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of GPB

The susceptibility profiles of GPB (n = 71) against twelve antibiotics are presented in Table 5. A wide range of variations with respect to resistance (12.3 to 71.4%) and susceptibility (22.5 to 87.7%) were observed in this case too. They were resistant to penicillin (70.4%, n = 50), ampicillin (71.4%, n = 10), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (64.9%, n = 37), tetracycline (63.2%, n = 36) and cloxacillin (54.9%, n = 39). Analysis of species-specific resistance profiles indicated that most of the isolates of S. aureus were resistant to penicillin (85.4%, n = 35), tetracycline (68.3%, n = 28), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (65.9%, n = 27), and cloxacillin (53.7%, n = 22). Among the isolates of S. aureus, 34.1% (n = 14) were methicillin-resistant and an inducible clindamycin-resistant phenotype was observed in the case of 7.3% (n = 3) of erythromycin-resistant MRSA.

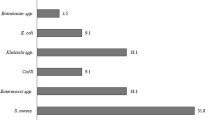

Multi-drug resistance profile

Among the total 141 bacterial isolates, 34.7% (n = 49) were MDR, and it comprised 28.1% (n = 20) of total GPB and 41.2% (n = 29) of GNB. Among the GPB, 18.3% (n = 13) of S. aureus and 4.2% (n = 3) of E. faecalis were found to be MDR. In the case of GNB, MDR was shown by E. coli (29%, n = 20), K. pneumoniae (5.8%, n = 4), E. aerogenes (2.9%, n = 2), P. mirabilis (2.9%, n = 2) and P. vulgaris (1.5%, n = 1) (Table 6).

ESBL and Carbapenemase-producing GNB

All isolates exhibiting resistance to cephalosporins (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone and cefepime) were suspected ESBL producers, whereas meropenem-resistant isolates were carbapenemase producers. We found that 27.1% (n = 19) and 18.6% (n = 13) isolates were suspected ESBL and carbapenemase producers, respectively. Out of these suspected cases of ESBL (n = 19) and carbapenemase (n = 13) producers, 15.7% (n = 11) and 10% (n = 7) respectively were phenotypically confirmed. The most common ESBL producer was E. coli (10%, n = 7), followed by K. pneumoniae (2.9%, n = 2). Isolates of E. coli (7.1%, n = 5) were the predominant carbapenemase producers (Table 6).

Factors associated with bacterial omphalitis

In bivariable analysis, about 24 variables were assessed, out of which 13 having P values ≤ 0.25 were subjected to further multivariable logistic regression analysis. Among these, only two variables that showed statistically significant association with omphalitis were enrolled into multivariable logistic regression analysis which were neonates borne with lower gestational age (≤ 37 weeks) [AOR = 2.1; CI= (1.26–3.41) P value = 0.004] and lack of hand washing habits of mothers/caretakers [AOR = 2.3, CI (1.33–3.93) P value = 0.003]; both were found to have significant statistical association (Table 7).

Discussion

Neonatal omphalitis is one of the major causes of referrals in all the four selected study settings, and its management still relies heavily on clinical judgment. The number of clinically suspected and culture-confirmed cases of omphalitis were 379 and 130 per 1000 live births, respectively, which indicates that it is a cause of concern among the study population. This specifies the importance of addressing the issue in healthcare delivery services. Also, the higher rate of culture-positive cases observed could be due to poor socio-economic status and unhygienic practices prevailing in the study area during the time of deliveries22.

We found that the isolation rates of GPB (50.4%, n = 71) and GNB (49.6%, n = 70) are, by and large, the same, and only a slight predominance is attributed to the former. This observation stands in contrast to some of the previous studies done in Uganda16, Madagascar23, and India24 that reported a preponderance of infection by GNB. However, an increasing trend in the dominance of GPB has been observed in some studies from China and Uganda22,25. The reasons for these variations in the spectra of bacteria associated with omphalitis are unclear; nevertheless, our results can be used as a reference/benchmark in fixing the regimen and bringing in changes in empirical antimicrobial therapy, if needed. We further observed that the pair, E. coli / S. aureus, was the most common combination causing poly-bacterial infections. The reasons for this pattern of infection are yet to be studied in detail to have a meaningful correlation between pathogenicity and the co-existence of different bacterial types. The culture negativity observed in our study can be a reflection of various factors, including the presence of anaerobic or fastidious bacteria, as well as the existence of viable but non-culturable bacteria.

The bacterial isolates detected in this study have already been identified as potential pathogens causing neonatal omphalitis5,11. The most common pathogens detected are S. aureus and E. coli, accounting for over 41% of the infection, and this is by and large in tandem with the results of a series of studies done in central Uganda16, China25, Tanzania26 Oman11 and Pakistan27. The predominance of S. aureus and E. coli proposes a probable inclusion of broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens for the management of omphalitis. In neonates, S. aureus is frequently associated with late-onset infection and can be considered as a hospital-acquired infection from a common source2. However, E. coli and K. pneumoniae were the dominant pathogens reported in a study done in central Uganda16, whereas Klebsiella spp. and S. aureus were the prominent isolates reported from Iraq28. Other pathogens, such as K. pneumoniae, P. mirabilis, and E. faecalis, were also isolated in lower proportions (< 8%). These pathogens are natural inhabitants of soil and water and can also be found in hospital environments.

The observed predominance of S. aureus and E. coli further substantiate the hypothesis that the source of infections may be exogenous, i.e., contamination originating vertically from the skin/mucosal flora (i.e., vaginal flora) of mother or horizontally from caregivers/ health care workers due to poor hand hygiene (hospital flora which is transmitted during delivery by the lack of hygiene) or cross-transmission among neonates or can be even from the hospital fomites. The higher isolation rates of the above pathogens observed in this study indicate the inadequacy in hospital infection prevention and control measures. It can also be considered of endogenous origin since the organisms that colonise the umbilicus or the surrounding skin can also produce omphalitis8.

Severe infections usually correspond to bi-bacterial isolates, whereas milder infections are generally mono-bacterial in nature. In the present study, an overall predominance of mono-bacterial omphalitis, with a strikingly higher isolation rate of 84.4% (n = 119), was recorded and is comparable to the results of a study reported from Pakistan27. The poly-bacterial nature of omphalitis is an essential finding of this study, and the frequency of isolation of bi-bacterial pathogens was only 15.6% (n = 22). It is noted that the skin and enteric bacteria belonging to both GPB and GNB can colonise the necrotic tissues of the cord simultaneously, eventually causing infections. The co-existence of both categories substantiates the general concept of difficulty involved in treating such diseases and the requirement of broad-spectrum antibiotics to deal with them.

The data on antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of bacteria over a stipulated period can be used to create a local antibiogram. Gentamicin is the first-line drug chosen for omphalitis caused by GNB in our study settings as per the WHO recommendation. Only 35.7% (n = 25) of GNB isolates exhibited resistance, substantiating, to a certain extent, the existing treatment options available for omphalitis in the study area. A combination of ceftriaxone/ cefotaxime/ and ceftazidime served as a second-line regimen. It was found that 51.4% (n = 36) of the isolated GNB showed resistance to ceftriaxone. It appears that meropenem/ cefepime /clindamycin or vancomycin can be recommended as the third-line drugs in our study settings for the effective management of severe cases of omphalitis. It is interesting to note that cefepime and meropenem were the most effective antibiotics (susceptibility > 80%) and, therefore, must be used meticulously. However, a slightly higher resistance was shown against meropenem compared to cefepime. The indiscriminate usage of these two drugs in neonates and other patients in the currently studied hospital settings would have culminated in this situation. This is a matter of grave concern if they remain to be the widely chosen mainstay drugs.

The predominant GNB, E. coli, exhibited higher resistance to ceftriaxone (56.4%, n = 22), somewhat similar to that reported from western Uganda (66.7%)22; however, the same bacterial isolates from central Uganda (16.6%)16 and Pakistan (11%)27 showed only much lower resistance. These observed variations might be due to the fluctuations in the frequency of antibiotic exposure, differences in the methods of susceptibility tests employed, sample size taken, and the clinical nature of the disease.

In all the four study settings, cloxacillin/ampicillin are recommended as the first-line drugs to treat neonatal omphalitis caused by GPB, and it is worrisome that most of the isolates of GPB showed resistance against penicillin, ampicillin (each > 70%), tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (each > 60%) and cloxacillin (> 50), restricting their empirical usage; WHO recommended a threshold of 5% resistance to change the empirical therapy in neonatal sepsis29. However, no such threshold has been suggested in the case of neonatal bacterial omphalitis. The major GPB, S. aureus, is often found to be resistant (53.7 to 85.4%) to penicillin, tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and cloxacillin. However, only 34.4% of S. aureus showed resistance, as per a previous study16. The inducible clindamycin resistance observed in our study was remarkably lower (7.3%) than that reported earlier from India (31.5%)30. These observed variations can stem from disparities prevailing in antibiotic prescription practices and the distribution of resistant bacteria in the study area.

Multi-drug resistance (MDR) can often worsen in various settings as a consequence of incomplete or wrong regimens and even due to the excessive consumption of multiple antibiotics for a prolonged period. In the present study, MDR was observed in the case of 34.7% of isolates, and this fact should be treated with considerable caution. The isolates of E. coli possess stronger multi-drug resistance (29%) than other Gram-negatives and also S. aureus (18.3%). The presence of omphalitis with MDR bacteria was also reported in China25,31. A significant outcome of our investigation is the detection of WHO-prioritised drug-resistant bacteria, including MRSA, ESBL, and CRE isolates, which present a challenge to pediatric practitioners. This emphasises the role of healthcare providers and policymakers in actively supporting the prudent use of antibiotics within the study settings. To mention a few, 34.1% of S. aureus were identified as MRSA, which by and large resembles the outcomes of several studies done earlier, for instance, in China25,31, India30, Pakistan3, Croatia32, and central Uganda16. We have observed that 27.1% (n = 19) of isolated GNBs were suspected ESBL producers, whereas 15.7% (n = 11) were actual producers; ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae were detected in a couple of studies done in China25,31 and Croatia32. Also, we found that 18.6% (n = 13) of isolates were suspected of carbapenemase production, out of which 10% (n = 7) were confirmed cases. A previous study conducted at AMGH reported the faecal colonisation of ESBL and CRE among neonates, indicating the circulation of drug-resistant bacteria in neonates of Arba Minch33.

Results from inferential statistics revealed that the lack of hand-washing practices and reduced length of gestation period were the most commonly associated factors related to omphalitis in the study settings. The hand-washing habit of mothers/caretakers during cord care was statistically significant [AOR = 2.3, CI (1.33–3.93) P value = 0.003], and the lack of this practice resulted in 2.3-fold enhanced vulnerability towards developing omphalitis. Our findings are similar to the observation from Turkey, where poor hand-washing practices contributed to the onset of omphalitis34. Those neonates with shorter gestational age have a double chance of acquiring infection leading to omphalitis [AOR = 2.1, CI (1.26–3.41) P value = 0.004]. Neonates who had a history of less than 37 weeks of gestation period typically have an immature immune system, leaving them vulnerable to infections in general35. This finding emphasizes the importance of immediate interventions against omphalitis during the antenatal period.

Limitations of the study

The shorter duration of the study period can be considered a limitation, as the study is institution-based and may not reflect an actual epidemiological pattern of omphalitis existing among the common population of neonates. The participants were recruited consecutively, and only aerobic cultures were performed, which may limit the identification of fastidious and anaerobic pathogens, and hence could have slightly misconstrued the results in general and underestimated the prevalence to a certain extent. The speciation and exact pathogenic role of the CoNs group of Gram-positive bacteria were not done. The evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility using minimum inhibitory concentrations and molecular confirmation of resistant phenotypes were also not done.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on neonatal omphalitis in Ethiopia. We found that the overall number of clinically suspected and culture-confirmed cases, respectively, were 379 and 130 per 1000 live births. The isolates of E. coli and S. aureus were found to be the most prevalent causative agents. Results of antimicrobial susceptibility tests revealed that there is a notable increase in the antibiotic resistance to several clinically relevant drugs, including penicillin, ampicillin, cloxacillin, tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ceftriaxone in the study settings. An important finding of our study is that 34.7% of bacteria were MDR, and this could be attributed to the irrational use of antibiotics and the lack of an antimicrobial stewardship program. An increase in the number of WHO-prioritised pathogens developing drug resistance is evident from our recent research. Thus, our results conclude that omphalitis remains an ongoing challenge in the study area. Significant predictors of omphalitis in neonates in the locality are the lack of hand-washing practices and lower gestation period.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Fraser, N., Davies, B. W. & Cusack, J. Neonatal omphalitis: A review of its serious complications. Acta Paediatr. 95 (5), 519–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250600640422 (2006).

Güvenç, H. et al. Omphalitis in term and preterm appropriate for gestational age and small for gestational age infants. J. Trop. Pediatr. 43 (6), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/43.6.368 (1997).

Mir, F. et al. Incidence and etiology of omphalitis in Pakistan: A community-based cohort study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 5 (12), 828–833. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.1229 (2011).

World Health Organization. Care of the Umbilical Cord. Maternal and New Born Health/safe Motherhood (World Health Organization, 1998).

Faridi, M. M., Rattan, A. & Ahmad, S. H. Omphalitis neonatorum. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 91 (11), 283–285 (1993).

Airede, A. I. Pathogens in neonatalomphalitis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 38 (3), 129–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/38.3.129 (1992).

Brook, I. Cutaneous and subcutaneous infections in newborns due to anaerobic bacteria. J. Perinat. Med. 30 (3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2002.028 (2002).

Pan American Health Organization. Prevention of Healthcare-associated Infections in Neonatology (PAHO, 2018).

Attia Hussein Mahmoud, H. et al. Insight into neonatal sepsis: An overview. Cureus 15 (9), e45530. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.45530 (2023).

Kaplan, R. L. et al. Omphalitis and concurrent serious bacterial infection. Pediatrics 149 (5), e2021054189. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-05418 (2022).

Sawardekar, K. P. Changing spectrum of neonatal omphalitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 23 (1), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000105200.18110.1e (2004).

Mullany, L. C. et al. Risk of mortality subsequent to umbilical cord infection among newborns of Southern Nepal: Cord infection and mortality. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28 (1), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e318181fb4c (2009).

Girma, D., Dejene, H. & Adugna, L. Predictors of neonatal mortality in Ethiopia: A comprehensive review of follow-up studies. Int. J. Pediatr. 2022, 1491912. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1491912 (2022).

Huynh, B. T. et al. Burden of bacterial resistance among neonatal infections in low income countries: How convincing is the epidemiological evidence? BMC Infect. Dis. 15, 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0843-x (2015).

Central Statistical Authority (Ethiopia) and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011 (Central Statistical Authority and ICF International, 2012).

Tumuhamye, J. et al. Umbilical cord stump infections in central Uganda: Incidence, bacteriological profile, and risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (23), 16055. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316055 (2022).

Collee, J. G. et al. McCartney Practical Medical Microbiology: Editors. 14 Th Ed (Elsevier, A division of Reed Elsevier India Private Limited, 2012).

Holt, J. G., Krieg, N. R., Sneath, P. H. A., Stanley, J. T. & William, S. T. 9th ed. Williams and Wilikins; Baltimore: Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 786–788. (1994).

Tille, P. Missouri. Bailey & scott’s diagnostic Microbiology. 14th ed. 987–997 (Mosby, Elsevier; St. Louis, 2017) .

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests, 13th ed. Approved Standard. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2022).

Magiorakos, A. P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18 (3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x (2012).

Turyasiima, M. et al. Bacteriology and antibiotic susceptibility patterns among neonates diagnosed of omphalitis at a tertiary special care baby unit in Western Uganda. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020, 4131098. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4131098 (2020).

Devred, I. et al. Incidence and risk factors of neonatal bacterial infections: A community-based cohort from Madagascar (2018–2021). BMC Infect. Dis. 23, 658. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08642-w (2023).

Faridi, M. M., Rattan, A. & Ahmad, S. H. Omphalitis neonatorum. J. Indian Med. Assoc. 91, 283 (1993).

Shen, A. Y. & Cai-Qi, Q. Zhang Jian-Hua. Study on 92 pathogens and drug-resistance of newborn omphalitis. Shanghai J. Prev. Med. 24 (4), 176–179 (2012).

Mhada, T. V. et al. Neonatal sepsis at muhimbili National hospital, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania; a etiology, antimicrobial sensitivity pattern and clinical outcome. BMC Public. Health. 12, 904. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-904 (2012).

Qamar, F. N., Tikmani, S. S., Mir, F. & Zaidi, A. K. Community-based management and outcome of omphalitis in newborns in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 63 (11), 1364–1369 (2013).

Sa’eed, W. W., Al-Mawla, S. O. & Al-Hiali, S. J. Omphalitis in neonates admitted to Al-Ramadi maternity and children hospital. Al- Anbar Med. J. 7 (Issue 1), 44–52 (2009).

Muller-Pebody, B. et al. Empirical treatment of neonatal sepsis: Are the current guidelines adequate? Archives of disease in childhood. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 96, F4–8 (2011).

Sengupta, M., Banerjee, S., Banerjee, P. & Guchhait, P. Outstanding prevalence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in neonatal omphalitis. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 10 (9), DM01–DM03. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/22799.8590 (2016).

Ying, C. Study on 69 pathogens and drug resistance of neonatal omphalitis. J. Math. Med. 2, 162–164 (2013).

Matijević, J., Golić, E., Čagalj, I. C. & Markić, J. Characteristics of newborns treated for acute omphalitis at the university hospital of split 2015–2019. Central Eur. J. Paediatr. 18 (2), 108–115 https://doi.org/10.5457/p2005-114.323 (2022).

Zakir, A., Regasa Dadi, B., Aklilu, A. & Oumer, Y. Investigation of extended-spectrum β-Lactamase and carbapenemase producing Gram-Negative bacilli in rectal swabs collected from neonates and their associated factors in neonatal intensive care units of Southern Ethiopia. Infect. Drug Resist. 23 (14), 3907–3917. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S333603 (2021).

Celebi Celik, F. et al. Current factors affecting the risk of omphalitis in newborns: A prospective case-control study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75 (5), e14071. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14071 (2021).

Melville, J. M. & Moss, T. J. M. The immune consequences of preterm birth. Front. Neurosci. 7, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00001 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support given by the Department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, in the form of required facilities. Thanks are extended to all the study participants/guardians who were involved in this research. The authors extend their appreciation to the researchers supporting project number (RSP2025 R479) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Thanks are also extended to Prof. Dr. K.R. Sabu for reviewing the manuscript and correcting the English language carefully.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Y., A.M., M.W., A/A.–Conceptualization, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–methodology, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A., A.Z., S.B., B.N., H.A.A., A.I.–software, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–validations, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–formal analysis, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–investigation, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–resources, AM., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–data curation, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A.–writing original draft preparation, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A., A.Z., S.B., B.N., H.A.A., A.I.–writing, review and editing, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A., A.Z., S.B., B.N., H.A.A., A.I.–visualization, A.M., M.W., A.A.–supervision, A.M., D.Y., M.W., A.A., M.S. project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yohannes, D., Manilal, A., Woldemariam, M. et al. Bacterial profile, antibiotic susceptibility patterns and associated factors among neonates suspected of omphalitis in Arba Minch, Southern Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 14404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98350-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98350-z