Abstract

National image building, a crucial element of Chinese soft power, has attracted growing scholarly attention. This study explores the discursive construction of one aspect of China’s national image—that of its military—and compares China’s self-projected images with those perceived by the United States. By employing a triangulated approach that integrates critical discourse analysis (CDA), a discourse-historical approach (DHA), three-dimensional typology, and corpus linguistics (CL), this paper examines the self-presentation and othering strategies employed by China and contrasts them with those used by the U.S. The findings highlight several key points: (1) While China presents a positive self-image, it often does so in a subtle and implicit manner; (2) Although negative depictions of other are commonly employed to construct a favourable self, China also elevates others as a superior group to be referenced, in an effort to legitimise its military actions; and (3) many military images promoted by China are countered by the U.S. The analysis identifies ideological systems, communicative purposes, and social psychology as key factors influencing the adoption of these discursive strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National image has long been a critical component of international relations and a key mechanism through which states shape global perceptions, assert ideological values, and cultivate soft power. For China, this endeavour has gained particular significance under President Xi Jinping’s leadership, as he has emphasised the importance of “telling China’s stories well” to present a credible, appealing, and respectable image to the world. Culturally, the Confucian doctrine of “face value” highlights the importance of projecting a favourable identity, making China’s discursive practices in national image-building a subject worthy of closer scrutiny.

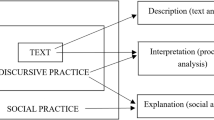

The construction of a nation’s image is inherently discursive and shaped by language, ideology, and historical narratives. Drawing on critical discourse analysis (CDA) (van Dijk, 1998), the discourse-historical approach (DHA) (Wodak, 2001), a three-dimensional typology (Pan et al. 2020), and corpus linguistics (CL), this study explores how China projects its military image through self-presentation in official documents, particularly the China’s Military Defence white paper (CMD). It also examines how this image contrasts with perceptions articulated by the United States in its China Military Power Report (CMPR), highlighting the strategic use of othering to position China as a competitor and potential threat.

Previous studies have extensively analysed the construction of national images in the context of conflicts (e.g., Bhatia, 2006; Chan, 2012; Lams, 2017; Li and Zhu, 2019; Tang, 2023), focusing on how domestic and international audiences actively interpret, justify, and negotiate national images and identities. These studies have highlighted the complex, often contested nature of national image-building, emphasising how various actors strategically shape perceptions to align with political, ideological, or diplomatic objectives. However, research on a nation’s military image as a distinct discursive construct remains limited. While previous studies have examined how nations project their images (e.g., Kinsey and Chung, 2013; Rusciano, 2003), less attention has been given to the interplay between self-projection and external perception, especially in the context of Sino-U.S. relations, which are characterised by strategic competition and ideological divergence.

This study addresses these gaps by comparing the discursive strategies employed in the CMD and the CMPR utilising an interdisciplinary approach that integrates CDA, DHA, the three-dimensional typology, and CL. Specifically, it seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

1.

How does China construct its military image through self-presentation and othering in the CMD?

-

2.

What discursive strategies does the U.S. employ in the CMPR to frame China’s military image?

-

3.

How do these strategies reflect broader ideological, political, and strategic objectives within the context of Sino-U.S. relations?

The military relationship between China and the U.S

The military relationship between China and the U.S. has a complex and multifaceted dynamic that is characterised by a mixture of cooperation, competition, and contention. Historically, this relationship has fluctuated due to the two countries’ divergent political, cultural, and ideological systems. For example, during the Cold War, the two nations were adversaries, with the U.S. supporting Western allies in opposition to the spread of communism. Media coverage in the U.S. during this period was predominantly “anticommunist”, often depicting China as a deceptive nation intent on establishing a communist world order (Herman and Chomsky, 2002; Wang and Ge, 2020). In the post-Cold War era, Sino-U.S. relations shifted largely from conflict to cooperation; however, significant underlying tensions still persisted, particularly in areas such as strategic competition in the South China Sea, U.S. support for Taiwan’s independence, and cybersecurity concerns.

In recent years, China’s rapid military modernisation—marked by advancements in missile technology, naval capabilities, and space assets—has intensified U.S. concerns regarding both regional and global power dynamics. In response to China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific, the U.S. has strengthened its allies and partnerships with regional actors such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia. In summary, the Sino-U.S. relationship has been shaped by a range of factors, including geopolitical shifts, evolving regional security dynamics, and technological advancements.

Literature review

The concept of national image, which was initially introduced by Kenneth E. Boulding (1959) in National Images and International Systems, has undergone significant evolution in recent decades and has become a critical focus in the fields of international relations and communication. Boulding emphasised the psychological and philosophical dimensions of how nations perceive one another, providing a foundational framework for subsequent research on the sociopolitical implications of national image construction. Kunczik (1997, p. 47) further defined national image as the cognitive representation of a nation, shaped by the beliefs and judgements of individuals or groups. This concept encompasses shared emotional responses, behavioural tendencies, and linguistic practices, all of which contribute to a collective sense of identity and belonging.

Wodak et al. (2009) conceptualised national identity as a “discursive product” that reflects shared values, collective memory, and sociopolitical realities (p. 28). The discourse surrounding national identity frequently relies on strategies of inclusion and exclusion, wherein certain groups are created as the ingroup (“we”), whereas others are positioned as outgroups (“others”). These strategies serve to reinforce internal solidarity within the nation by highlighting common values and shared experiences while simultaneously delineating the nation’s distinct cultural, political, and ideological values from those of the outgroups.

Globalisation has increased interest in the ways in which nations construct and project their images on the international stage. Scholars such as Nye (2011, pp. 20–21) have linked national image to the concept of soft power, emphasising its role in shaping global perceptions through persuasion and attraction rather than coercion. As such, national image building is not simply a reflection of national identity but rather a strategic endeavour, often aligned with a nation’s geopolitical objectives and diplomatic priorities.

China’s efforts to construct its national image have evolved over time, mirroring shifts in domestic priorities and international aspirations (Kurlantzick, 2007; Lams, 2018; Li and Li, 2015; Meng, 2020; Wang, 2003). Scholars have observed both continuity and discontinuity in China’s image-building efforts. Wang (2003) and Lams (2018) highlighted the persistence of certain themes, such as portraying China as a peace-loving nation and a victim of foreign aggression. At the same time, presenting China as a rising global power and a significant contributor to world governance has become a growing focus, reflecting its evolving role on the world stage.

Scholars have also increasingly focused on the international community’s responses to China’s self-projected images, specifically examining how China is perceived globally and whether its self-constructed image is accepted and recognised favourably by international audiences. Research on this topic generally falls into two main areas. The first concerns the acceptance of China’s self-projected image in various countries or regions, including the U.S. (Wang, 2003), Eurasia (Rolland, 2007), and Middle Asia (She et al., 2020). Geopolitical and diplomatic policies are factors influencing other nations’ perceptions of China. For example, while China presents itself as a peace-loving nation, an international collaborator, and an autonomous actor, some Americans continue to view it as a militant and obstructive force (Wang, 2003). In contrast, neighbouring countries such as Kazakhstan generally perceive China as “a rapid rising power” (She et al., 2020), presenting a relatively positive political, cultural, and economic image, despite some negative reports concerning China’s military and social issues being occasionally noted.

The second branch of research focuses on China’s dissemination of key terms that carry distinct political or ideological significance. Several studies have examined Western responses to terms such as “中国特色社会主义” (socialism with Chinese characteristics, Hu and Han, 2020); “改革开放” (reform and opening-up, Wang and Hu, 2023); “小康社会” (a moderately prosperous society, Wang and Hu, 2024); and “中国梦” (Chinese dream, Wang, 2016). These studies have suggested that mainstream media in Western countries generally adopt a neutral or positive stance towards these terms, although they occasionally misinterpret the underlying concepts. On the one hand, this can be attributed to the recognition of China’s economic achievements and development model; on the other hand, it reflects the significant differences in social systems, ideologies, and political stances between China and Western countries.

In addition to scholarly attention to the construction of self-image and the reception of terms with Chinese characteristics, another significant focus is on the discursive strategies used to address social-political and ideological discrepancies that arise in the context of international issues, conflicts, or incidents. These include cases such as the China–U.S. trade wars/disputes (e.g., Pan et al., 2020; Tang, 2023), the East China Sea trawler collision incident (e.g., Bhatia, 2006; Chan, 2012; Wang and Ge, 2020), and broader efforts to present a positive national self-image (e.g., Klimeš and Marinelli, 2018; Lams, 2018; Li and Zhu, 2019). In these contexts, national images are deliberately projected to serve the diplomatic objectives of the respective governments. Discursive strategies—such as categorising or recategorising inter- or intragroup relations, positive self-presentation, and negative othering—play a crucial role in advancing China’s soft-power efforts.

These studies have treated media as “a type of soft power resource and a conduit through which soft power resources are amplified and transmitted” (Pan et al., 2020, p. 55), highlighting its critical role in meaning-making through discourse. With access to a range of communication channels, Western countries such as the U.S. and the UK have long maintained global communication superiority (Snow and Cull, 2020; van Dijk, 1996). However, disparities in information and communication within the global media landscape are gradually narrowing, creating more opportunities for non-Western perspectives. In response, the Hu Jintao administration initiated an international media campaign to counter unfavourable portrayals of China in U.S.-dominated global media, a campaign that has intensified and expanded under Xi Jinping’s leadership (Hartig, 2020; Lams, 2018; Tang, 2023). In light of this trend and the effects of globalisation, China’s media outlets are rapidly expanding in an effort to project a more positive image to a global audience.

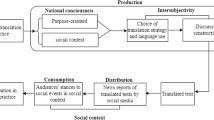

In this context, the translation of “China’s voice” has become crucial in conveying Chinese messages, serving as “part of the discursive endeavour to construct positive Chinese representations abroad” (Li and Li, 2015, p. 424). Many researchers in translation studies have focused on the national images communicated through translated texts and the enabling and constraining roles played by translators and interpreters in mediating these images. For example, Gu (2018, 2019), Gu and Tipton (2020), Gao (2021), and Gao and Wang (2021) explored how interpreters align with and reshape China’s political discourse in translated English. Their research revealed interpreters’ significant roles in constructing a cohesive and authoritative image of China for international audiences through discursive strategies such as self-referential language (e.g., we, China, government), emphasising solidarity and institutional legitimacy.

Furthermore, Hu and Meng (2018) reported that while interpreters may share the same objective of conforming to their governments’ ideological positions, gender differences can influence the discursive strategies they adopt in conference settings. Pan (2015) showed that translators resorted to evaluative resources to facilitate ideologically divergent positions when presenting foreign news articles on China’s human rights issues in Reference News. Gao (2021) explored the nationalism of interpreters at the Davos Forum, showing that Chinese interpreters employed specific discursive strategies (e.g., self-censorship, neutralising self-negativity, and aggrandising self-positivity) on key issues of national interest, such as sovereignty, territorial integrity, and diplomatic relations.

In response to national calls to “accelerate the development of China’s discourse and narrative systems” (Xi Jinping, Report to the 20th National Congress), some Chinese scholars have focused on constructing a specific image of China within various industries, including the ecological (He and Cheng, 2023), traditional Chinese medicine (Pan and Zhu, 2024), Wushu (martial arts) (Li et al., 2024), and military (Gong, 2022) industries.

Given the growing awareness of presenting China on the international stage, some studies have shown that China’s ability to project its image has significantly increased, with its image partially improved and more favourably perceived, especially in some developing and neighbouring countries (Bailard, 2016; Kurlantzick, 2007; She et al., 2020). However, other studies have noted limitations in the effectiveness of China’s image (re)construction, highlighting that certain Western nations and foreign audiences remain influenced by negative perceptions (e.g., the “China threat”) and continue to be sceptical of Chinese political policies and ideologies (Pan, 2004; Rawnsley, 2020; Wang, 2003, 2016). As such, China still faces considerable challenges in framing a universally positive image across various dimensions and perspectives.

While significant progress has been made in understanding China’s image construction, limited attention has been given to the construction of China’s military image as (re)produced both by China and other nations. Among the few studies on this topic, Gong (2022) demonstrated that self-construction and other constructions of national military image are not static but rather dynamic processes. By examining the interactive speeches delivered by spokespeople from China and the U.S. at the Shangri-La Dialogue between 2014 and 2019, Gong reported that the principles of relationality and intersubjectivity play a vital role in shaping a nation’s military image.

With the rapid development of China’s economy and technology, the nation is increasingly recognised as a “rising military power” (Lanteigne, 2020, p. 7), although it still lags behind the West in many key areas. In the broader context of effectively communicating China’s military image, constructing a positive international military image is essential. This objective aligns with the goals of “advancing the cause of building a strong and modernised military and achieving the goal of establishing a word-class armed force; adhering to the military’s policy of openness; fostering international military partnerships in the new era; and enhancing China’s global influence while bolstering the military’s soft power” (Wu, 2018; author’s translation). Furthermore, it is equally important to consider how other military powers perceive this constructed image, as their interpretations can help China anticipate the broader geopolitical and security implications of its military posturing.

Theoretical framework and analytical approach

This study adopts a triangulated methodological framework that integrates CDA, DHA, Pan et al.’s framework (2020), and CL. According to Wodak et al. (2009, p. 9), triangulation entails examining discursive phenomena through a combination of various theoretical and methodological perspectives, drawing on insights from multiple academic disciplines. This approach is further described as a “methodological win‒win approach” (Gu, 2024, p. 533), offering a comprehensive and multifaceted exploration of national image (re)construction. By integrating sociopolitical and linguistic perspectives, this study provides a more nuanced and reliable understanding of the dynamic relationship between discourse and ideology.

CDA, as articulated by van Dijk (1998, 2011), provides a social‒cognitive framework for examining how language reproduces ideologies and power relations. This theory is particularly suitable for national identity studies because it provides a “problem-oriented and interdisciplinary approach to studying the social and political aspects of language use that are closely related to ideology and power” (Gu, 2024, p. 531). Scholars such as Fairclough (1995) and van Dijk (1998, 2011, 2016) emphasise the role of discourse in legitimising ideologies and power structures while marginalising opposing viewpoints. In van Dijk’s CDA framework (1995, p. 248), ideology is defined as “basic frameworks of social cognition, shared by members of social groups, constituted by relevant selections of sociocultural values, and organised by an ideological schema that represent the self-definition of a group”. The conception implies that ideologies are not merely individual beliefs but also collectively shared beliefs of social groups.

CDA views language as a social practice, uncovering hidden ideologies and opaque power structures that are reproduced, legitimised, and consolidated in discourse (Gu, 2024). A key model for analysing how ideology is reproduced through discourse at the macro level is the “ideological square”, which involves the “rhetorical contamination of hyperbolic emphasis and mitigation of good or bad things of ingroups and outgroups” (van Dijk, 2016, pp. 73–74). As part of a broader strategy for ideological communication, the ideological square consists of the following moves (van Dijk, 1998, p. 267):

-

1.

Express/emphasise information that is positive about Us

-

2.

Express/emphasise information that is negative about Them

-

3.

Suppress/deemphasise information that is positive about Them

-

4.

Suppress/deemphasise information that is negative about Us

These four moves are integral to the broader strategy of positive self-presentation and face-keeping, as well as negative other-presentation. It is considered revealing and prominent in revealing ideologies hidden in political discourse (Reisigl and Wodak, 2016; Wodak, 2015).

As a microlevel extension of CDA, the DHA incorporates both historical continuity and change, focusing on how discursive representations of social realities evolve within shifting political and historical contexts (Wodak, 2001, p. 65). The DHA particularly emphasises the discursive constructions of “us” and “them”, making it especially suitable for examining how national identities adapt to global pressures, such as conflicts or economic transformations. This approach can uncover how countries may adjust their self-presentation in the international sphere to project a more favourable image, particularly when aiming to improve diplomatic relations, attract foreign investment, or bolster their soft power (Wodak et al., 2009).

The DHA orients to five types of discursive strategies: nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivisation and intensification (Reisigl and Wodak, 2016, pp. 32–33). In conducting analyses via these strategies, researchers frequently orient themselves to five questions, as outlined in Table 1 below:

While nomination and predication are relatively straightforward to comprehend and code, argumentation requires more detailed elucidation owing to the complexity of its topoi (topics and arguments, singular topos). In the context of the DHA, topoi refers to the conclusion rules that link the arguments to conclusions. As such, they justify the transition from premises to the final claim (Reisigl and Wodak, 2001, p. 74). The topoi can be paraphrased using either conditional (if x, then y) or causal (y, because x) structures. A list of the typical content-related argument schemes, though “incomplete and not always disjunctive” (Wodak, 2001), is given in the Appendix.

To supplement the DHA, this study employs a three-dimensional typology (Pan et al., 2020) of discursive strategies used by actors to construct their strategic narratives: charm offensive, othering offensive, and defensive denial. The charm offensive “describes the sum of public diplomacy aimed at promoting positive self-images and winning hearts and minds” (Pan et al., 2020, p. 58). The othering offensive “refers to the construction of a negative and repulsive Other as a foil for indirectly fashioning a positive and attractive self-identity” (Pan et al., 2020). These two strategies correspond to “positive self-presentation” and “negative other-presentation” in the ideological square. The third strategy, defensive denial, involves “a largely reactive strategy of resisting or denying negative discourses about the Self, often as a response to an Othering offensive by other actors” (Pan et al., 2020).

To complement the qualitative methods of CDA, the DHA, and the typology of discursive strategies, CL is incorporated into the methodology for its objectivity, rigour, and systematicity. The quantitative method helps “avoid personal bias in discourse analysis” (Li and Zhu, 2019, p. 5) and facilitates the examination of widely shared ideologies and stereotypes in discourse communities (Stubbs, 2001), thus enabling the study to uncover meaningful insights into the discourse.

Data collection

The analysis focuses on two types of military discourses issued by China and the U.S. The first are CMDs (China’s Military Defence white papers), which are revised by the Ministry of National Defence of the People’s Republic of China and published by the State Council Information Office. The second are CMPRs, officially titled Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, which are presented annually to the U.S. Congress by the Department of Defence (DoD).

As a subgenre of Chinese white papers, CMDs are periodically published in multiple languages to provide comprehensive insights into China’s military development while addressing international concerns. In contrast, CMPRs assess China’s military capabilities, strategic objectives, and security developments, providing the U.S. Congress with a framework to anticipate China’s potential challenges and refine its defence strategies.

The corpus for this study consists of English versions of CMDs collected from the State Council Information Office website (http://www.scio.gov.cn/zfbps/) for the period 1998–2020. This collection includes 12 texts totalling 187,778 tokens. Similarly, CMPRs were sourced from the official U.S. DoD website (www.defence.gov) for the same period, yielding 232,230 tokens. The texts were downloaded, preprocessed, and cleaned for analysis. The details of the self-built corpus are outlined in Table 2 below:

The software package AntConc 3.5.9 was used to retrieve and analyse the corpus data. Two key features of the software—the wordlist and the key word in context (KWIC) sort functions—were particularly instrumental. The wordlist function identifies high-frequency words within the corpus, revealing recurring themes, terminologies, and lexical patterns. The KWIC sort function organises concordance lines around specific nodes, enabling a contextual examination. For example, sorting the lexical item China by its immediate right-hand collocates reveals how the nation is portrayed in military discourse, such as through modifiers such as peaceful or descriptors such as threat.

Data analysis

The data analysis comprised three stages. In the first stage, a corpus approach was employed to identify recurring lexical patterns within the texts. Using the wordlist function of AntConc 3.5.9, self-referential and other-referential items in the CMD corpus were identified. The self-group included terms such as China, China’s, Chinese, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), our, we, and the Communist Party of China (CPC). The other-group comprised lexical items referring to other countries or regions (e.g., Japan, Russia, the U.S., the United States, Pakistan, and countries) and non-China-affiliated organisations (e.g., the UN and ASEAN countries). Concordance lines containing these nodes were manually reviewed and analysed.

In a limited number of cases, collocates cooccurring after Chinese were characteristics, features or ways. Together with Chinese, these word combinations in turn formed a postmodification to the proceeding clause, which does not directly depict the nature or behaviour of China, the Chinese military or the Chinese government. These instances were rearranged via the KWIC sort function (one word to the right of the node) and were excluded from the analysis. After batch searches, 4087 concordance lines from the self-group and 1098 from the other-group were retrieved from the CMD corpus.

In the second stage, a qualitative analysis was performed through close reading of the sampled datasets. The concordance lines were exported into MS Excel spreadsheets, and 500 instances from each group (self and other) were randomly selected using the Excel’s randomisation function. Drawing on the framework of van Dijk’s sociocognitive approach CDA (1998), Wodak’s DHA (2016), and Pan et al.’s typology (2020), this study analysed the discursive strategies used in CMD texts to construct China’s military image. Frequencies, ratios, and proportions of strategies were computed for statistical analysis.

The third stage focused on foreign othering strategies employed in the CMPR corpus, analysing how the U.S. depicts China’s military image. The word list function identified lexical items related to China, including China, China’s, Chinese, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Concordance lines containing these nodes were extracted and sampled for detailed analysis.

The self-presentation of China’s military image

This section examines the self-presenting and othering discursive strategies employed by the CMD to construct China’s international military image. Table 3 presents the respective frequencies of lexical items constituting the self-group and the other-group. As the table indicates, self-group lexical items occur nearly four times more frequently than those in the other-group do (217.7 vs. 77.4 per 10,000 running words). This finding indicates that the CMD prioritises self-presentation strategies over othering strategies in shaping China’s military image.

The top three self-referential items were China (56%), the PLA (18.3%) and China’s (13.1%), collectively highlighting China’s strategic emphasis on evaluating itself directly in a more positive manner.

The salient other-group items included neighbouring countries and organisations, such as Japan, Russia, and India, accounting for 808 instances (44.9%). The prevalence highlights China’s geopolitical context and its emphasis on multilateral diplomacy and fostering friendly relations with neighbouring countries (睦邻友好). Additionally, the UN, the world’s most inclusive intergovernmental organisation, frequently appears in the other-group, accounting for 16.1% of the instances. This reflects China’s firm advocacy for multilateralism, using the UN as a platform to counterbalance the unilateral actions of major powers and to promote a multipolar world order. Chinese leaders often stress the importance of the “democratisation of international relations” (国际关系民主化) and uphold the UN’s principles of state sovereignty and noninterference. As a result, the UN is presented not as a negative foil but as a neutral or even positive entity within the other-group.

The item U.S. appeared prominently at the top of the other-group list, which suggests that the CMD frequently engages in othering of the U.S. This form of othering is distinct from that of neighbouring countries, as it reflects China’s military policy and the intricate military relations between the two nations. Thus, the specific discursive strategies employed by the CMD, including both self-presentation and othering strategies, need to be analysed to gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of how China shapes and projects its military image on the international stage.

Strategies for presenting a positive self

The strategies were examined through a close reading of sample datasets derived from concordance lines containing lexical items categorised within the self-group. In cases where the concordance lines alone did not provide sufficient context, a broader textual context was consulted. The frequencies of each discursive strategy–nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivisation, intensification, and denial defensive–were then calculated and are presented in Fig. 1.

Notably, the concordance lines may feature multiple strategies simultaneously. For example, the combination of predication and intensification is illustrated in Examples 1 and 2, and the concurrent use of denial defence and intensification is demonstrated in Example 3. Each of these strategies was individually counted and computed in the analysis.

-

1.

China actively participates in international space cooperation, develops relevant technologies and capabilities, advances holistic management of space-based information resources, strengthens space situation awareness, safeguards space assets, and enhances the capacity to safely enter, exit and openly use outer space.

-

2.

China is constantly reforming its management system of defence-related science, technology and industry.

-

3.

China firmly opposes the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and their means of delivery and actively takes part in international nonproliferation efforts.

The employment of a predication strategy

As shown in Fig. 1, the CMD relies heavily on a predication strategy in its self-presenting process, accounting for approximately 81.6% of the sampled texts and representing approximately 3335 instances identified in the corpus. In contrast, the CMD shows a noticeable avoidance of the nomination strategy. Table 4 summarises the salient predications among the positive portrayals the CMD sought to project to international audiences.

The analysis of these predications revealed that the strategy was employed both implicitly and explicitly, with distinct linguistic realisations. The implicit predications were predominantly realised through two linguistic patterns: the first, “self-referential items (in the self-group) + present perfect (continuous)”, which accounted for 13.8% of the 408 instances of predication. The second pattern, “self-referential items + will”, represented 5.4% of the instances.

The former pattern was categorised as an implicit self-presentation strategy by referring to Quirk et al.’s comprehensive research on English grammar (1985). They noted that the present perfect tense primarily connects past actions or states to the present, highlighting either completion or continuity (1985, pp. 191–192). Quirk et al. further noted that the choice of the present perfect implies an “implicit time zone” (Quirk et al., 1985), suggesting that the action or state is ongoing. Similarly, the present continuous tense “draws attention to the duration of an action that began in the past and has been ongoing up to the present” (Quirk et al. 1985, p. 197), highlighting its temporal extent over its results. As Gu (2018, p. 4) observed, “discursively and rhetorically, the employment of the present perfect (continuous) structures can be viewed as an emphatic and ideologically salient way of presenting a particular social actor’s past actions and achievements”. By frequently employing this linguistic strategy, China discursively constructs an image of a practical, diligent government that is conscientious and proactive in addressing military issues.

The latter pattern was informed by the concept of mode and modality as defined in systemic functional linguistics (SFL). In SFL, modality reflects a speaker’s or writer’s attitude, certainty, belief, or engagement with the proposition, functioning as a means of interaction between the speaker and the listener (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004, p. 615). Moreover, Fairclough (1989, p. 29) described modality as the “producer’s categorical commitment to the truth of the proposition”. A key variable in modality is orientation, which can be subjective or objective and may be expressed either explicitly or implicitly (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004, p. 615).

As a “median inclination modal verb” (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004, p. 624), will conveys both obligation and intention to international audiences while simultaneously limiting alternative possibilities. Xu (2015, p. 119) reported that will exhibits semantic ambiguity, as it can express either volition or intention (volitional modality), high probability in the future (epistemic modality), or both. When used with a personal subject, will typically expresses volition or intention, whereas when used with an impersonal subject, it leans towards the epistemic modality. Consider the following examples:

-

4.

In the years to come, China will continue to participate in UN peace-keeping operations in a positive and downwards manner.

-

5.

However, the Chinese government will not forswear the use of force.

In these instances, where the impersonal subjects of China and the Chinese government preceded will, the modal verb functions as epistemic modality, indicating probability and possibility (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004) and reflecting the speaker’s evaluation of the status and validity of a proposition (Halliday, 1970). This usage, which is exemplified in Example 4, reveals China’s intention to engage in international peacekeeping efforts, thereby subtly constructing a conscientious and peace-loving image. Example 5 demonstrates how will implicitly signals the Chinese government’s resolute political stance on the Taiwan question, expressing an unwavering intention to pursue reunification with Taiwan at any cost. While China seeks to project a peace-oriented image globally, this statement also reinforces its firm position on Taiwan, framing China as steadfast in its commitment to territorial integrity and national unity, a stance underscored by significant “ideological investment” (Lams, 2017, p. 7).

Beyond the implicit strategies for self-presentation, the predications also reveal a more direct approach, prominently featuring the pattern “self-referential items + is”, which accounts for approximately 9.6% (39 mentions) of the predications in the sampled data. According to Quirk et al. (1985, pp. 1771–1773), the verb be in the structure “subject + be” serves to “complete the meaning of the subject by identifying or describing it” (p. 1771) and typically “describe[s] a state or quality attributed to the subject”. This pattern thus facilitates both the attribution and identification of the subject, thereby broadening its meaningful connections to the predicate. In the corpus under examination in the present study, the CMD employs this structure to predicate subject identification, either through ingroup and outgroup categorisation (as shown in Example 6) or by highlighting subject characteristics (as demonstrated in Example 7).

-

6.

China, too, is a victim of terrorism. The “East Turkistan” terrorist forces are a serious threat to the security of the lives and property of the people of all China’s ethnic groups, as well as to the country’s social stability. On September 11, 2002, the UN Security Council, in response to a common demand from China, the United States, Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan, formally included the “East Turkistan Islamic Movement” on its list of terrorist organisations.

-

7.

The PLA is a people’s army created and led by the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the principal body of China’s armed forces.

In Example 6, China predefines itself as a victim of terrorism, specifically threatened by “East Turkistan” terrorists, thereby projecting an image of vulnerability. This prescriptive statement generates ideological, yet subtle, “implicatures” (Grice, 1975) regarding the perceived necessity of combating terrorism to safeguard national security. A broad “victimhood” identity is thus constructed, emphasising commonalities between China and other international entities (e.g., the UN Security Council) or nations (e.g., the U.S.). By using this framing, China discursively aligns itself with these organisations and nations in the global fight against terrorism, transforming the cognitive representation from a dichotomy of “us” vs. “them” to a unified “we”, seeking to “reduce intergroup bias and promote more harmonious attitudes and interactions” (Chan, 2012, p. 373).

Example 7 illustrates the typical application of this structure to depict the characteristics or functions of the subject. By linking the subject directly to its complements, the relationship between the PLA and the CPC is clarified, explicitly constructing the image of a “people’s army”.

The employment of the argumentation strategy

Unlike the news genre, which often exhibits more dialectical quality, the CMD, as official propaganda disseminated through the Chinese government’s website, demonstrates a notable lack of overt argumentative features. Nonetheless, certain argumentation strategies have been classified and annotated, typically embedded within predication strategies. As Tang (2023, p. 5) notes, these two strategies “cannot be separated neatly from each other”. Of the 15 topoi proposed by Reisigl and Wodak (2001, pp. 74–80), two topoi, namely, the topos of numbers and the topos of law and right–were observed in the CMD.

The rules for identifying the topos of numbers are subsumed under the conclusion rule: “if the numbers prove a specific topos, a specific action should be performed or not be carried out” (Reisigl and Wodak, 2001, p. 76). Example 8 showcases a typical application of the topos of numbers, arguing that while China allocates a portion of its budget to the military, the expenditure fluctuates within an acceptable range. Compared with other major powers, China’s military expenditure is significantly lower. Through this argument, China effectively undermined negative interpretations, such as the “China’s threat” narrative.

-

8.

In the past two years, the percentages of China’s annual defence expenditure to its GDP and to the state’s financial expenditure in the same period have remained basically stable. In 2003, China’s defence expenditure amounted to only 5.69% of that of the United States, 56.78% of that of Japan, 37.07% of that of the United Kingdom, and 75.94% of that of France.

According to Reisigl and Wodak (2001), the topos of law and right can be condensed in the conditional as follows: “if a law or an otherwise codified norm prescribes or forbids a specific politico-administrative action, the action has to be performed or omitted”. This strategy is used to portray China as a defender and promoter of world peace, emphasising that all of its military actions, whether domestic or international, are legitimised and rationalised by relevant regulations and laws. van Dijk noted that a central function of ideologies is legitimation, noting that “[p]ragmatically, legitimation is related to the speech act of defending oneself, in that one of its appropriateness conditions is often that the speaker is providing good reasons, grounds or acceptable motivations for past or present actions that has been or could be criticised by others” (1998, p. 255). Through this strategy, unfavourable labels such as the “revisionist state” (Allison, 2017) are countered by emphasising that China’s military power neither seeks to alter the current international order for its own interests nor destabilise global order. Rather, it is lawfully regulated to uphold the world order and foster peaceful cooperation, as illustrated in Example 9:

-

9.

The Chinese government places high importance on combating transnational crimes and is committed to fully and earnestly implementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime (UNTOC).

The employment of an intensification strategy

The intensification strategy primarily serves to amplify or mitigate the illocutionary force of statements (Reisigl and Wodak, 2001, p. 33). It is often employed in conjunction with other strategies, such as predication and defensive denial, as previously illustrated in Examples 1 and 3.

In this study, the intensification strategy is predominantly realised (68 out of 72 mentions) through “hyping words”, defined as “subjective language used to glamorise, promote or even embellish content” (Millar et al., 2020, p. 54). An interesting finding is that quotations, though infrequent (accounting for only five instances in the dataset), also function as a form of intensification. Consider Example 10:

-

10.

“We will not attack unless we are attacked; but we will surely counterattack if attacked”. Following this principle, China will resolutely take all necessary measures to safeguard its national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

All five quotations are identical: “We will not attack unless we are attacked; but we will surely counterattack if attacked” (人不犯我, 我不犯人;人若犯我, 我必犯人). Echoing Chairman Mao, this principle is frequently reiterated to emphasise that China’s military strategy is based on a policy of active defence. This phrase recurs in various forms within China’s political discourse, reinforcing the nation’s stance on self-defence in matters such as the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and border tensions. By employing this strategy, China has strengthened its military posture and constructed an image as a staunch defender of sovereignty.

The discursive strategies of China’s othering

At the macro level, othering strategies are typically associated with the “negative presentation” of a social group’s image (van Dijk, 1998, 2006). Othering offensive strategies, as defined by Pan et al. (2020, p. 58), involve asserting a national positive self through negative portrayals in media narratives. This strategy plays a crucial role in China’s ongoing efforts to increase its soft power (Pan et al., 2020, p. 64). Building on the work of Pan et al. (2020), Tang (2023) demonstrated how Chinese Ambassador Liu Xiaoming used strategies such as nomination, predication, and argumentation to construct the U.S. as a negative other, thereby delegitimising its trade policies and actions while simultaneously fostering a positive image of China.

In addition to serving as a foil for a positive self/us, othering also addresses ontological anxiety and security concerns (Browning and Joenniemi, 2017) and can be used to justify dominance and the application of hard power (Pan, 2004). The offensive and negative functions of othering empower the self and complement its “implicitly self-referential” nature (Hayden, 2012; Pan et al., 2020).

To investigate how othering in the CMD contributes to China’s military image, concordance lines containing lexical times from the other-group were extracted, with 500 instances randomly selected for detailed manual annotation. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the four DHA strategies employed by the CMD in its portrayal of others. Among these strategies, predication was the most frequently used strategy in the CMD’s othering process, accounting for 88.3% of the sampled texts. The intensification and argumentation strategies were the second and third most prevalent strategies, respectively. The CMD appeared to avoid overtly deprecatory labels when referring to others.

The employment of predication

Table 5 summarises the salient predications associated with the most frequently identified features of the other group.

Unlike the more overt othering strategies typically seen in news media, which primarily construct a negative other as a foil for a positive self/us, the CMD adopts a more nuanced approach. It attributes both negative and positive characteristics to others while simultaneously projecting a positive self. Notably, positive predications are significantly more common than negative predications, with a ratio of 5:1. By aligning China with the positive other, the CMD strengthens its own favourable self-image, as demonstrated in the following examples:

-

11.

The Chinese people, like the people of all other countries, do not want to see any new war, hot or cold, or turbulence in any region of the world but yearn for lasting peace, stability and tranquillity, as well as common development and universal prosperity worldwide.

-

12.

As a founding member of the UN and a responsible member of the international community, China honours its obligations, firmly supports the UN’s authority and stature, and actively participates in the UNPKOs. China is a permanent member of the UN Security Council; thus, as a major country, China needs to play an active part in the UNPKOs.

-

13.

China and the ASEAN are committed to extending practical maritime security cooperation, developing regional security mechanisms and building the South China Sea into a sea of peace, friendship and cooperation.

The recategorisation in Example 11 offers valuable insights into how China constructs a positive self by transitioning its image from a singular national identity to a membership within the broader “we-group” of countries united against the threat of new wars. This shift emphasises shared values and objectives, potentially mitigating intergroup bias or conflicts and “redirect towards establishing more harmonious intergroup relations” (Gaertner et al., 1993, p. 1). Through this discursive construction of a broad ingroup, the CMD reinforces common goals of peace and stability while firmly rejecting war in any form. In this sense, the othering of other nations actually serves to facilitate, rather than undermine, China’s positive self-presentation. Unlike the news genre, which often accentuates distinctions between “home” nations and “other” nations to promote ethnocentrism, the CMD employs othering to blur boundaries between the self and outgroup members, thus establishing favourable intergroup relationships.

In addition to predicating other countries as a positive ingroup, the CMD also portrays international organisations, such as the UN, as elite entities that legitimise China’s military actions, as illustrated in Example 12. By reinforcing its status as a founding member of the UN and a permanent member of the UN Security Council, China seeks to assert its authoritativeness and counter accusations, particularly those from the U.S., which characterise China’s dispatching peacekeepers as an attempt to “give the PLA opportunities to acquire operational and mobilisation proficiency in addition to strengthening civil‒military relations” (CMPR, 2014, p. 35). This portrayal stands in stark contrast to China’s self-representation as a peace-loving nation.

While leveraging the UN as an elite organisation to foster positive perceptions within the international community, China also uses the ASEAN to enhance intragroup relations within the “we-group”. Neighbouring countries and organisations are positively predicated on their shared commitment to establishing and maintaining homogeneous relationships. This discursive practice highlights common responsibilities and frames China’s diplomatic stance towards the ASEAN, as illustrated in Example 13.

The discursive construction of a redefined outgroup further reinforces a cognitive representation of a broad “antiterrorist” coalition that includes China and other entities, facilitating intergroup comparison and differentiation. By invoking outgroup elites, such as the UN Security Council, China reclassifies both itself and the outgroup under a higher-order common identity with mutual goals. This strategy, akin to the Chinese idiom “yi3yi2zhi4yi2 (以夷制夷—combat foreigners with foreigners)”, is a recurring feature in Chinese diplomatic discourse (Ng et al., 2011, p. 145).

Although China predominantly predicts others positively on the basis of shared interests and values, it also adopts othering as an offensive strategy to assert its military stance. Example 14 demonstrates how China categorises India and Pakistan as outgroup members on the basis of their nuclear tests, which are perceived as violations of China’s military guidelines. This positioning reinforces the contrast between China’s commitment to military discipline and the perceived irresponsibility of these nations.

-

14.

The nuclear tests successively conducted by India and Pakistan have seriously impeded international nuclear weapon nonproliferation efforts and produced grave consequences.

Another negative portrayal of others arises from the depiction of unstable territorial situations in other regions, as shown in Example 15. These presentations serve as a negative foil to China’s image of solidarity, reinforcing its military identity as the “people’s defender”.

-

15.

The uncertain factors affecting security on the Korean Peninsula continue to exist, and the situation in South Asia remains unstable.

Additionally, Example 16 illustrates an instance where blame is attributed to the U.S. for actions perceived as provoking or destabilising regional or global peace. By countering and rejecting U.S. military principles, the CMD strengthens China’s military image as a “sovereignty defender” and reaffirms its resolute stance on nonnegotiable policies, especially regarding Taiwan.

-

16.

China resolutely opposes the wrong practices and provocative activities of the U.S. regarding arms sales to Taiwan, sanctions on the CMC Equipment Development Department and its leadership, illegal entry into China’s territorial waters and maritime and air spaces near relevant islands and reefs, and wide-range and frequent close-in reconnaissance.

The employment of intensification

The sample data revealed 33 instances of the intensification strategy. In addition to employing hyping words to emphasise partnerships between China and other countries (as demonstrated in Example 17, which combines intensification with predication), the deontic modal verb should is adopted to emphasise China’s commitment to the elimination of nuclear weapons (see Example 18).

-

17.

The strategic and cooperative partnership between Russia and China continues to be comprehensively and vigorously reinforced.

-

18.

All countries should further drastically reduce their nuclear arsenals in a verifiable, irreversible and legally binding manner to create the necessary conditions for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons.

In political discourse, the deontic modality reflects “the positioning of the speaker with respect to the necessity/rightness (values) concerning the realisation of events” (Xu, 2015, p. 248), thus encoding a value-based stance grounded in the speaker’s moral values (Chilton, 2004). Although this use of the deontic modality was observed only four times within the sample data’s categorisation of intensification, it nonetheless highlights the CMD’s discursive strategy of constructing a positive self through emphatic moral positioning.

The employment of argumentation

Two content-related topoi were identified in the data: the topos of numbers (nine out of 14) and the topos of justice (five out of 14). Example 19 illustrates the use of the topos of numbers in CMD’s othering strategy. China mitigates perceptions of its military threat by emphasising its comparatively lower defence expenditures. By highlighting that other nations allocate more to national defence, China implies that its modest investment should not be construed as a threat to the international order.

-

19.

China’s per capita defence expenditure in 2017 was RMB 750–5% of that of the U.S., 25% of that of Russia, 231% of that of India, 13% of that of the UK, 16% of that of France, 29% of that of Japan, and 20% of that of Germany.

The second topos identified was justice, which posits that “ [i]f a law or an otherwise codified norm prescribes or forbids a specific politico-administrative action, the action has to be performed or omitted” (Reisigl and Wodak, 2001, p. 75). In the cases examined, the “codified norm” validating China’s military actions is grounded in regulations and laws established by the UN. By consistently positioning the UN as the ultimate arbiter of justice for world peace, China legitimises its actions, such as dispatching military observers, liaison officers, or advisers to peacekeeping operations. This discourse reinforces China’s image as a nonthreatening, peace-loving nation.

-

20.

According to the UN Charter, the UN Security Council is conferred primary responsibility for the maintenance of world peace and security.

The U.S. othering offensive

As noted by Pan et al. (2020, p. 59), an “othering offensive involves framing a significant other or ‘telling foreign stories’ in a negative way”. In the context of the CMPR, China is prominently constructed as the primary “other” through the strategy of othering. Lexical items categorised within the self-group during the analysis of the CMD corpus were treated as nodes indicative of the othering strategy in the CMPR corpus. Lemmas related to China (e.g., China, China’s, and Chinese), as well as other frequently occurring lexical items referencing China, such as the CPC and PLA, were considered.

The search yielded 8680 instances, with China being the most frequently mentioned term (5657 occurrences). As in the previous analysis, a random sample of 500 instances was subjected to detailed annotation. The analysis of CMPR’s discursive strategies reveals that China was predominantly constructed as a negative other in relation to its military image. The CMPR primarily employed the predication strategy to depict China’s military actions as a means of asserting ambitions and expanding international influence. Argumentation and intensification strategies were the next most frequently used approaches. Unlike the CMD, which rarely employs the nomination strategy for othering, the CMPR occasionally adopts this method. Figure 3 outlines the distributions of these strategies.

The use of prediction

Three negative portrayals of China in the CMPR were particularly salient, as summarised in Table 6:

While China has sought to project an image of a peace-loving nation dedicated to multilateral cooperation, the U.S. has countered this narrative, claiming that China’s advocacy for international cooperation serves primarily as a façade to conceal its military ambitions. According to the U.S., China uses this guise to mitigate territorial disputes and further its strategic interests, as exemplified in Example 21:

-

21.

In 2017, China extended economic cooperation to the Philippines in exchange for taking steps to shelve territorial and maritime disputes.

This image is further reinforced by portraying China as an ambitious nation through the use of “material clauses”, which signify processes of doing-and-happening (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004, pp. 179–180). A material clause typically involves one participant (the actor) initiating an action, resulting in an outcome that may either remain confined to the actor or extend to a goal. In the present corpus, such clauses predominantly fall into the latter category, employing verbs that denote China’s ambitious endeavours, as illustrated in the following example:

-

22.

China continues to execute “Made in China 2025,” an ambitious industrial policy centred on “smart manufacturing,” which seeks to create a vanguard of corporations in the PRC that are global leaders in ten strategic industries.

Here, the verbs continue and seeks indicate the ongoing nature of China’s actions. According to the SFL, the phrase continues to, while not directly expressing modality, convey the speaker’s certainty about the action or state (Halliday, 1970, p. 335). The CMPR employs such verbs to construct China as an ambitious nation pursuing hegemony or posing a threat to global peace, thereby reinforcing negative framings, such as the “China’s rise” or the “China threat” narratives.

The CMD repeatedly emphasises that China’s military spending is relatively low compared with that of other major military powers (e.g., the U.S., the UK, France) in an effort to counter unfavourable narratives. In contrast, the CMPR focuses on the steady growth of China’s military budget over the past decades, providing a theoretical justification for the country’s expanding military influence.

-

23.

China’s official military budget grew at an annual average of 8 percent in inflation-adjusted terms over that period. China is likely able to support continued defence spending growth for the foreseeable future.

In China’s construction of the other, the UN is portrayed as an authoritative institution committed to maintaining world peace. As an active member supporting UN military regulations, China frames its military actions as just and legitimate, thereby cultivating an image of using its military power to preserve peace. In contrast, the U.S. portrays China as a nation that violates UN protocols, emphasising the “illegitimacy” of China’s military actions and constructing a negative military image, as illustrated in the following example:

-

24.

In its protest to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, China included its ambiguous “nine-dash line” map, while stating in a note verbale that it has “indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof. ”

The Taiwan issue remains a central topic of contention in U.S.–China relations. China regards Taiwan as an inseparable part of its territory and emphasises its commitment to reclaiming it as a crucial step in upholding national sovereignty, including the potential use of military forces. The CMPR, however, employs predication strategies to frame China’s actions towards Taiwan as acts of “invasion”, often in combination with nomination strategies. This framing shifts China’s image from being a defender of sovereignty to being an aggressor, as demonstrated in Example 25.

-

25.

As the number of these new systems grows in the PLA, the ability of an amphibious invasion force to defend cross-strait amphibious lodgements successfully against counterattacks by both legacy and advanced weaponry will inevitably increase.

The employment of argumentation

Four topoi were identified in the 65 instances where the argumentation strategy was employed: the topos of danger or threat (37 instances), the topos of numbers (five instances), the topos of justice (four instances), and the topos of law and right (19 instances).

The topos of danger or threat is defined as “[i]f a political action or decision hears specific dangerous, threatening consequences, one should do something against them”. This topos is central to the CMPR’s argumentation strategy. Example 26 illustrates the combination of an argumentation strategy (the topos of danger or threat) with a predication strategy.

-

26.

China has expanded and modernised its nuclear forces.

The verb expand is utilised here to predicate China’s ambitions to increase its military influence. The object of nuclear forces implies a potential threat posed by China to world peace, especially given the international community’s strong opposition to nuclear proliferation. Another instance demonstrates how the topos of justice is reflected:

-

27.

China is expanding the PLA’s capacity to contest U.S. military superiority in the event of a regional conflict.

The U.S. has positioned itself as a global power with a self-appointed responsibility to uphold justice on the international stage, often projecting a sense of superiority. As such, any actions or nations that challenge its perceived authority are framed as threats to the justice it claims to protect. Example 27 illustrates how China is negatively portrayed for its efforts to develop and enhance its military capacity, actions deemed potentially disrupting to the justice upheld by the U.S.

The employment of intensification

In the sample data, only 11 instances of intensification were identified. Notably, eight of these employed quotation marks to emphasise and reinforce the conveyed messages, as demonstrated in the example below:

-

28.

China’s move into unmanned systems is “alarming” and combines unlimited resources with technological awareness that might allow China to match or even outpace U.S. spending on unmanned systems in the future.

China’s development and spending on military technologies are significant concerns for proponents of the U.S. “China threat” narrative. These proponents draw on historical precedents, asserting that “states which rise towards great power status are often war prone, as they seek a louder voice in international affairs and focus on protecting assets outside their immediate territory, which may result in push back from other great powers” (Lanteigne, 2020, p. 143). The CMPR’s use of quotation marks draws attention to specific terms or phrases, enhancing their rhetorical weight and subtly directing readers to focus on China’s competitive and potentially confrontational role.

The employment of nominations

The use of nominating, or naming, reflects an author’s ideological stance and understanding of the sociopolitical context, historical significance, and power dynamics associated with specific terms. As Simpson (1993, p. 141) noted, “a choice of one type of name over another can encode important information about the writer’s attitude to the individual referred to in a text”. This strategy is a key component of the CMPR’s othering offensive.

In the sample, 18 out of 19 instances involved referring to the CPC (or the Communist Party of China) as the CCP (or the Chinese Communist Party). In the full CMPR corpus, the ratio of CPC to CCP mentions is approximately 0.067 (17 vs.252). The distinction between these terms has significant implications for framing, perception, and narrative control in political discourse.

Historically, the term Chinese Communist Party was used between 1921 and 1943, when the Party was affiliated with the Comintern (Communist International). During this period, the name highlighted the Party’s establishment in China by Chinese members, distinguishing it from communist parties in other countries. Following the Comintern’s dissolution in 1943, the term Communist Party of China was adopted to emphasise the Party’s independence and its national focus. Linguistically, the genitive construction (Quirk et al., 1985, p. 703) “of China” suggests a possessive relationship, framing the Party as belonging to China rather than being a subordinate branch of an external organisation.

The use of CCP, in contrast, shifts the focus to the Party’s role as a governing entity, potentially framing it as a specific, and possibly illegitimate, ruling body rather than as a representative of the nation. The U.S. preference for this terminology highlights the ideological divide between the two countries, highlighting opposition to the Communist Party itself. This framing likely resonates with audiences holding negative perceptions of communism, thereby reinforcing U.S. narratives within the context of geopolitical competition.

Discussion

This study systematically examines the discursive strategies adopted by China to present its military image and how this image is framed discursively by the U.S. in their respective narratives. As shown in Table 3, the CMD relies predominantly on positive self-representation strategies to project a favourable military image to the global audience. Among the five discursive strategies analysed, predication emerges as the most salient. Through this strategy, the CMD emphasises positive attributes, such as being a peace-loving nation, a promoter of international cooperation, and a nonthreatening power. These depictions contrast sharply with the CMPR, which frequently employs negative predications to underscore China’s military expansion.

Occasionally, intensification, which is realised primarily through hyping words, is combined with predication in the CMD to reinforce China’s stances and actions, thereby enhancing its persuasive impact. The analysis suggests that a concealed purpose of fostering ingroup identity is evident in the CMD’s predications, shifting representations of membership from “us” and “them” to a more inclusive “we”. This recategorisation of distinct groups into a unified entity, emphasising shared experiences (e.g., victimhood) and collective goals (e.g., international peace), fosters positive attitudes towards former outgroup members. This approach aligns with China’s broader diplomatic emphasis on multilateralism and inclusivity.

In addition to overt self-representation, the CMD employs more implicit strategies to project a favourable image. One such strategy involves the use of the modal verb will, which, according to Bhatia (2006, p. 173), “can also be useful indicators of ideological differences and expectations, when hidden in manipulated utterances…”. This strategy, which is discreetly applied, helps portray a consistent and positive stance.

The CMD also employs argumentation strategies to counter critiques of China’s growing military expenditures and its perceived threat to others. The topos of numbers emphasises that China’s military spending remains significantly lower than that of other military powers, despite a moderate increase in recent years. Additionally, the CMD argues that China dispatches peacekeepers out of a commitment to uphold UN laws, framing such actions as adhering to global norms. These arguments counter ideological narratives surrounding “China’s rise” and “China threat” while simultaneously portraying China favourably.

Another notable approach involves denial as a defensive strategy, often deployed in response to the CMPR’s othering offensive. Negative portrayals of others are viewed as exercises of influence and power, as articulated by van Dijk (1993, pp. 249–250). The adoption of this strategy has been noted in several studies of soft power (Nye, 2011; Pan et al., 2020; Tang, 2023; Wang, 2016). The CMD primarily uses a denial defensive to rebut depictions of China as a hegemonic nation, especially in the CMPR’s framing of China’s sovereignty claims over Taiwan as acts of “invasion”. As Gries (2004) and Ho (2015) suggest, the collective memory of suffering and vulnerability has cultivated a strong desire to preserve national dignity and assert sovereignty—values that are central to China’s discourse on military power. The denial defensive strategies employed by China serve not only to protect its image but also to reaffirm its stance against external forces that challenge its territorial integrity and political system.

Interestingly, the CMD does not consistently amplify negative portrayals of others, as prescribed by the ideological square. Rather, it often positions others as superordinate authorities to legitimise their actions or recategorise nations with shared interests as part of an ingroup to strengthen relationships. Positive outcomes and behaviours are attributed to the stable internal characteristics of this recategorised ingroup, thereby fostering solidarity. For example, when China and its allies are portrayed as sharing common identities, such as opposing nuclear proliferation or supporting the “One China” policy, Manichean dichotomies are subtly invoked. This reflects a “moderate tendency towards a ‘Self versus Others’ mentality” (Li and Zhu, 2019, p. 13) and aligns with a Chinese political philosophy that “encourages a more dynamic relation between Self and Other in order to serve its interests” (Li and Zhu, 2019, pp. 13–14).

Different members of the classified other-group serve distinct functions in realising China’s moderate othering strategy. For nations that may not support China’s ideology (e.g., Japan), the CMD stresses shared identities to mitigate bias. For neighbouring countries that are more aligned with China’s ideology, predication strategies are adopted to enhance local relations, particularly military cooperation. These approaches adhere to van Dijk’s (1998, p. 171) assertion that “two groups or organisations may have different ideologies (e.g., Catholic and Muslim), but may well co-operate to realise a common goal, and jointly acquire or defend shared interests” and that “ideological opponents may thus become allies in pursuing the realisation of the same goals”.

In contrast to Sun’s (2012) assertion that othering is merely a tactic or diplomatic trick designed to damage the other’s “exiting reputation image” (p. 151) and “a tool in domestic policy more than in foreign policy (Callahan, 2015, pp. 217, 220), this study argues that othering in the Chinese context enables China to indirectly project itself in a more attractive light. The present study further demonstrates that othering in the Chinese context can function both as a “negative soft power” strategy (Callahan, 2015) and a “positive soft power” strategy, realising a “manipulation effect” (van Dijk, 2016) that recategorises the “them” into the “us” group to promote a more harmonious intergroup relationship. This characteristic distinguishes China’s approach from that of Chinese media narratives, where discourse often presents a “hegemonic character” (Lams, 2017, p. 8) and a “high degree of assertiveness in uttering truth claims and articulating directive speech acts” (Lams, 2017).

The analysis also shows that the U.S. employs robust othering offensive strategies, functioning as “foreign offensive” tactics aligned with van Dijk’s (2016, p. 380) concept of “discursive manipulation”. By constructing China as a “revisionist state” (Allison, 2017) challenging U.S. hegemony, the CMPR reflects U.S. political ideology, portraying China as a rising power threatening a world “antithetical to U.S. values” (Tang, 2023, p. 6). The CMPR frequently highlights China’s military modernisation and space exploration as strategies to assert dominance, thereby reinforcing the “China threat” theory and complicating China’s peace-oriented narratives. Moreover, the CMPR uses the topoi of danger and justice to frame China as a destabilising force that threatens the global order, thus justifying U.S. military policies. Historical tensions, particularly regarding Taiwan, further exacerbate these divergent narratives, with China framing its actions as sovereignty defences and the U.S. portraying them as acts of invasion.

The CMPR’s nomination strategy is particularly noteworthy for its consistent use of CCP over CPC. By foregrounding the “Communist” label, the U.S. taps into Cold War-era narratives that align China’s political system with broader ideological rivalry. This choice reflects a deliberate attempt to distance China from a more neutral, national identity (embodied in the CPC) and instead casts the Party as part of a global ideological context. This rhetorical move is aimed not only at legitimising China’s political structure but also at reinforcing the adversarial relationship between China and the West. The focus on “Communist” emphasises China’s ideological otherness, framing it as a threat to liberal democratic values and contributing to the perpetuation of the “China threat” narrative.

The contrasting strategies of the CMD and CMPR reflect the complexities of geopolitical discourse. China’s efforts to frame itself as a peaceful power committed to multilateralism stand in sharp contrast to the U.S.’s portrayal of China as a global disruptor and challenger to the status quo. These discursive battles are central to shaping perceptions of national identity and legitimacy on the global stage, influencing both public opinions and diplomatic relations.

Conclusion

“[I]mage and reputation are becoming critical elements of national strategies, and globalisation and media revolution have propelled every government to put a premium on its image, reputation and attitudes” (Li and Zhou, 2005, p. 120). Self-image building is viewed as a nation’s projection of favourable norms and systems in its bid for dominance in intentional codes and conduct (Nye, 1990).

This paper contributes to the growing body of research on soft power, particularly from the perspective of image construction. While previous research has focused on the discursive national image projected by the nation itself, this study broadens the focus to include the discursive strategies adopted by others, particularly by nations with complex, sometimes rivalrous, relationships.

Discursive strategies are central to showcasing a nation’s soft power, allowing nations to construct and project their preferred image on the global stage. The contrast between the CMD and the CMPR in the study illustrates how differing discursive approaches reflect broader ideological and strategic objectives, highlighting the power of language in shaping international relations. For China’s policymakers, enhancing transparency and addressing contentious issues through discursive strategies could strengthen its credibility. Analysing the discursive strategies adopted by other nations and understanding the images they construct could help China adjust its narratives and foster diplomatic engagement, reducing the risk of misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

This article compares only military images constructed and perceived through China’s military white paper and the U.S.‒China military report. Further studies should expand to include a broader range of genres and the perceptions held by other countries, both Western and non-Western. Exploring other types of images, such as those related to sports, would also be valuable. Additionally, triangulating analytical approaches would also provide more comprehensive and multifaceted results.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BKZLLY.

References

Allison G (2017) Destined for war: can America and China escape Thucydides’s trap? Houghton Mifflin Harcour, London

Bailard CS (2016) China in Africa: an analysis of the effect of Chinese media expansion on African public opinion. Int J. Press/Politics 21(4):446–471

Bhatia A (2006) Critical discourse analysis of political press conferences. Discourse Soc. 17(2):173–203

Boulding KE (1959) The image: knowledge in life and society. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Browning CS, Joenniemi P (2017) Ontological security, self-articulation and the securitization of identity. Coop. Confl. 52(1):31–47

Callahan WA (2015) Identity and security in China: the negative soft power of the China dream. Politics 35(3-4):216–229

Chan M (2012) The discursive reproduction of ideologies and national identities in the Chinese and Japanese English-language press. Discourse Commun. 6(4):361–378

Chilton PA (2004) Analysing political discourse: theory and practice. Routledge, London

Fairclough N (1989) Language and power. Longman, London

Fairclough N (1995) Critical discourse analysis. Longman, New York

Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF, Anastasio PA, Bachman BA, Rust MC (1993) The common ingroup identity model: recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 4(1):1–26

Gao F (2021) Making sense of nationalism manifested in interpreted texts at ‘Summer Davos’ in China. Crit. Discourse Stud. 18(6):688–704

Gao F, Wang BH (2021) Conference interpreting in diplomatic settings: an analysis integrated corpus and critical discourse analysis. In: Wang CW, Zheng BH (eds) Empirical studies of translation and interpreting. Routledge, New York, p 285

Gong SP (2022) Pragmatic construction of national identity in military diplomatic discourse [Junshi waijiao huayu zhong guojia xingxiang de yuyong jiangou]. Foreign Lang. Res 6:41–47

Grice P (1975) Logic and conversation. In: Cole P, Morgan J (eds) Syntax and semantics: speech acts. Academic Press, New York, pp 41–58

Gries PH (2004) China’s new nationalism: pride, politics, and diplomacy. California Press. University of, Berkeley

Gu C (2018) Forging a glorious past via the ‘ present perfect’: a corpus-based CDA analysis of China’s past accomplishments discourse mediat(is)ed at China’s interpreted political press conferences. Discourse Context Media 24:137–149

Gu C (2019) Interpreters caught up in an ideological tug-of-war? Transl. Interpret Stud. 14(1):1–20

Gu C (2024) Corpora, ideology, and interpreting. In: Li D, Corbett J (eds) The Routledge handbook of corpus translation studies. Routledge, New York, pp 550–564