Abstract

This study examines the scenarios under which asymmetric estimations can arise from employing artificial intelligence (AI) models to assess housing prices. Advances in the pricing instrument effectively tackle the inherent nonlinearity issue in relevant datasets, and AI technologies have demonstrated superior predictive power compared with traditional approaches. However, AI models may penalize minority groups against the majority in a social manner. We empirically explore the potential negative externalities, specifically the asymmetric estimations that can arise across social groups when using machine learning technology to assess housing prices. Our findings highlight three notable observations. First, education levels are significantly and positively associated with housing prices. Second, AI models can appraise housing prices more precisely compared with conventional hedonic models. Finally, AI models tend to overestimate the housing prices of well-educated groups and underestimate those of less-educated groups. These results indicate that AI models improve the predictive power of price assessments; however, indiscriminate adoption and application of AI-based predictions may aggravate social inequality. Our findings provide insights into ways to alleviate inequality in urban areas; thus, policymakers can refer to our empirical evidence when designing initiatives to enhance social inclusion and coherence, and when considering strategies to realize balanced urban development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology has afforded various gains to academic circles and industries in the asset pricing field. AI algorithms have superior flexibility to capture the nonlinearity inherent in datasets; thus, such algorithms have been widely employed to perform various tasks in the financial domain, e.g., assessing credit risks (Bussmann et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Baur et al., 2023) and forecasting recession and stock market crashes (Malladi, 2024). In addition, using AI algorithms in property price appraisals enables more precise assessment compared to traditional methodologies (Chen et al., 2022; Baur et al., 2023). Despite this promising potential, several negative effects attributed to the flexible inference of AI have been reported (Desiere and Struyven, 2021; Friedler et al., 2021; Fuster et al., 2022). For example, asymmetric estimation is a key concern inherent to AI algorithms because it can penalize social and/or economic minority groups, and these concerns can be applied to housing price appraisals. Disparities between social groups in housing price appraisals can lead to income inequality (Choi and Green, 2022) and social polarization (Bénabou, 1994) due to asymmetric housing affordability, thereby potentially threatening sustainable urban development and societal equity.

Traditionally, housing prices have been appreciated using hedonic price models (HPM), which have a long history of use in investigating the relationship between housing factors and property prices (McMillan et al., 1980; Chau and Chin, 2003; Hong et al., 2020; An et al., 2023). Despite their simple implementation and understandability, criticisms have contended that HPMs are limited in terms of their ability to capture the complexity in datasets accurately (Chau and Chin, 2003; Hong et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). As an alternative, AI algorithms have recently been applied to the housing price appraisal task because they can seize the nonlinearity and dynamic patterns of housing prices effectively (Kang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Tchuente and Nyawa, 2022) due to their flexibility.

However, previous studies have acknowledged the adversarial effects of AI-based assessments, which may increase the disparities between social groups. For example, Friedler et al. (2021) found that machine learning (ML)-based decision-making systems can potentially discriminate according to demographic, social, and/or economic groups. For instance, the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions, a case management and decision support tool used by United States (US) courts to assess potential recidivism, indicates that black defendants are twice as likely to be misclassified as recidivists compared to white defendants (Angwin et al., 2022). In addition, Desiere and Struyven (2021) demonstrated that AI-based profiling is 2.6 times more likely to misclassify foreign jobseekers as high-risk holders than native jobseekers. Similarly, ML technology has been shown to favor white non-Hispanic borrowers with lower average default propensities than black and Hispanic borrowers. Here, minority borrowers with largely dispersed default probabilities are penalized when estimating their risks, which has been attributed to the greater flexibility of ML algorithms (Fuster et al., 2022) compared with traditional statistical models. To the best of our knowledge, although potential inequality across economic and/or racial groups derived from ML-based assessment systems is evident, the discrimination effects between less-educated and well-educated groups in housing price appraisals have yet to be explored thoroughly.

Educational services and the local education level are closely linked to property prices; thus, the relationship between these factors has been investigated (Wen et al., 2017). Most relevant studies have found that education quality has a positive association with housing prices (Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger, 2011; Wen et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2018). Highly educated residents tend to have higher incomes than the less-educated; thus, they have greater purchasing power in the housing market, resulting in increased housing prices in well-educated cities (Guo and Qian, 2021). For less-educated individuals, the housing cost barrier frequently keeps them from living in a well-educated city (Berry and Glaeser, 2005; Choi and Green, 2022) because residents prefer housings nearby high-quality educational facilities, thereby leading to an increase in housing prices (Wang and Li, 2022). In this sense, the inequality between neighborhoods in terms of education can be presumed and empirically proven. In addition, if AI algorithms exaggerate the gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged groups, the unequal effects of housing price appraisals using AI algorithms according to education quality and achievement in urban cities are worthy of extensive examination.

Previous studies have demonstrated the unequal effects of AI algorithms, which tend to favor major social groups’ values over those of minor social groups (Desiere and Struyven, 2021; Friedler et al., 2021; Angwin et al., 2022; Fuster et al., 2022). We recognize that the characteristics of social groups can be the primary driver of the unequal effects caused by AI algorithms and note that such AI-induced inequalities may manifest in housing price appraisals based on educational levels in Korean neighborhoods. In that context, this study also explores the potential for AI-based property valuations to exacerbate inequalities where educational levels are unevenly distributed across neighborhoods.

Thereby, this study examines how AI models may produce unequal price appraisals and how these asymmetric price appraisals are exacerbated across heterogeneous neighborhoods in educational contexts. To elucidate this, we focus on the differences in the results between the AI and traditional HPMs, i.e., the comparative analysis between the nonlinear and linear valuation models (Fuster et al., 2022). In this procedure, we primarily control the education variables concerning the housing price appraisal. The comparative analysis between AI algorithms and traditional HPMs reveals that neighborhoods with lower education levels are penalized by AI models, whereas well-educated neighborhoods are favored. In addition, discrepancies in housing price assessments are exacerbated in accordance with local higher education levels. This indicates the tradeoffs associated with introducing AI algorithms into housing price appraisal, i.e., while taking advantage of flexibility, fairness in housing price assessments is reduced.

The findings of this study contribute to real estate and property valuation studies dedicated to developing impartial and transparent valuation models by identifying implications regarding the negative externalities of AI algorithms. The results also provide insights for decision makers seeking to advance sustainable urban societies and balanced city development. Policymakers can contemplate which social groups are potentially exposed to these unequal effects and which factors may drive inequalities in housing price appraisals.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. “Literature review” reviews previous literature. “Study contexts” provides background information on the study sites and South Korea in general. “Data and methodology” explains the data and methodological framework used in the study, including the experimental design. “Results and discussion” details the results regarding the unequal effects of AI algorithms in housing price appraisals and discusses the findings. Finally, the paper is concluded in “Conclusion”.

Literature review

Asymmetric estimations of the artificial intelligence models

Existing studies have applied AI models to establish a credit scoring model (Gunnarsson et al., 2021), property valuation frameworks (Baur et al., 2023), and mortgage default prediction systems (Fitzpatrick and Mues, 2016). This procedure highlights the comparative analysis between linear and nonlinear models; the former can provide basic trend information and a formidable starting point for unseen samples, particularly against nonlinear models such as AI algorithms (Schulz et al., 2020). However, previous studies have primarily focused on enhancing the predictive power of nonlinear models by comparing them with those of linear models.

A growing body of literature has indicated that sophisticated models (whose accuracies are validated against linear models) can produce asymmetric estimations that overestimate major social groups’ values while underestimating those of minor social groups (Desiere and Struyven, 2021; Friedler et al., 2021; Angwin et al., 2022; Fuster et al., 2022). This situation calls for more empirical evidence and time to ensure the trained AI models’ capability in real-world settings, aside from the given test datasets (Yang et al., 2022). In other words, the deployed models require continuous monitoring and updates to be balanced in real-world settings, even after finalizing them during the testing phase (Gama et al., 2014; Paleyes et al., 2022).

If an AI-based property valuation model tends to favor specific social groups compared to linear models that provide a benchmark point (Schulz et al., 2020), it may have long-term implications for housing price appraisals. Housing price valuation systems are rarely updated due to illiquid property transactions (Deppner et al., 2023); therefore, a significant dependency on AI systems, merely validated during testing, can potentially threaten social sustainability and exacerbate societal inequalities over time. Hence, we must determine the possible episodes where asymmetric estimations of AI models can occur for housing price appraisals. Such investigations require focusing on the model validation procedure regarding fairness and balanced estimation for social groups.

Relationship between education variables and housing prices

Various aspects determine housing prices, including housing attributes, neighborhood characteristics, financial circumstances, and education—a key variable concerning housing prices (Wen et al., 2017; Wen et al., 2018). Previous studies have documented that educational resources are vital social assets in urban development (Berry and Glaeser, 2005; Guo and Qian, 2021; Choi and Green, 2022) and significantly influence housing prices and homebuyers’ decisions to purchase dwellings (Guo and Qian, 2021; Wang and Li, 2022). Furthermore, differences in neighborhood education levels could lead to regional disparities and societal inequality (Berry and Glaeser, 2005; Choi and Green, 2022). This implies that heightened property values due to educational privileges could exacerbate existing inequalities and be a significant barrier to social integration; however, existing literature has primarily highlighted the significance of local education levels on housing prices, overlooking how these disparities can arise in housing price appraisals and become aggravated following different educational contexts.

Urban educational resources—including educational facilities and school quality—are key determinants for property valuations and exhibit a nonuniform relationship with housing prices (Bayer et al., 2007; Wen et al., 2018). Thus, education variables can provide critical information for precisely appraising housing prices, particularly for the tail groups characterized by heterogeneous educational environment levels, offering significant implications for AI-based valuation models. HPMs primarily capture trends and linear patterns in housing prices. In contrast, AI models generate flexible and nonlinear price appraisals (Hong et al., 2020; Schulz et al., 2020), making AI-based estimates more susceptible to distortion at the tails of social groups (Fuster et al., 2022).

In this sense, the absence of education variables from a housing variable set can induce asymmetric estimations, causing AI algorithms to systematically over- or under-estimate property values at the tails of educated groups. Moreover, the interrelationship between social variables and asymmetric estimations produced by AI models (Desiere and Struyven, 2021; Friedler et al., 2021; Angwin et al., 2022; Fuster et al., 2022) highlights the need to examine how the absence of education variables can exacerbate unequal effects in housing price appraisals, particularly for marginal educated groups.

Accordingly, the novelty and contributions of this study are threefold. First, we deliver insights into the conditions under which AI-based property valuation models generate asymmetric price estimations, producing unequal effects. Second, this study identifies how these unequal effects can be exacerbated by the heterogeneous educational contexts of different neighborhoods. Finally, this study explores potential pathways through which housing inequality may be intensified via disparities in housing price appraisals.

Study contexts

Education is significantly associated with housing prices and has been considered a primary resource for economic development in South Korea for a long time. In the early 1950s, after the Korean War left the country in ruins, South Korea overcame despair and developed its economy rapidly (Oh, 2007; Ministry of Education, 2015). “Education fever”Footnote 1, which has been prevalent in Korea for several hundred years, has increased the quality of human resources and enabled rapid economic development (Jones, 2013; Dittrich and Neuhaus, 2023). Since the new millennium, the demand for excellent creative human resources has increased, underscoring knowledge-intensive cutting-edge technology industries and changes in the global economy. Thus, South Korea has focused on developing human resources to establish a strong knowledge-based society, thereby fueling the need for education to cultivate highly educated workers and professional industrial human resources (Ministry of Education, 2015). In this context, homebuyers in South Korea tend to prefer neighborhoods with high-quality education services because parents want their children to enjoy an environment that is conducive to quality education.

In addition, education is an effective path to success and has been considered the fairest way of climbing the economic ladder. This actively leads to well-educated parents having higher willingness and ability to pay for education costs than less-educated parents. However, criticisms have been mounting. For example, the intensive education fever in South Korea has exacerbated the polarization of society because it forces parents to invest excessively in private tutoring for their children (Ministry of Education, 2015).Footnote 2 Thus, increased education costs are imputed to housing costs, thereby creating obstacles for lower-income families seeking to reside in well-educated neighborhoods. This corroborates the existing literature documenting that housing cost barriers are related to education (Berry and Glaeser, 2005; Choi and Green, 2022) because better education services and institutions increase neighborhood housing prices (Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger, 2011; Wen et al., 2017). Therefore, we can infer that South Korea has a nonuniform distribution of housing prices depending on heterogeneous local educational levels. As such, South Korea has an appropriate background to investigate whether the unequal effects of AI-based housing price appraisals can be exacerbated according to local educational levels.

Four metropolitan cities in South Korea, i.e., Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, and Gwangju, were selected as the survey areas in this study. Note that Greater Seoul has been investigated extensively and consistently explored, providing substantial empirical evidence that educational services and facilities have positive associations with housing prices (Jang and Kang, 2015; Sung and Ki, 2023). In contrast to Greater Seoul, financial premiums of local educational levels to housing prices have not been explored extensively in the target areas. In addition, these four cities have unique patterns of education environments compared with Greater Seoul due to the educational administration system in South Korea.Footnote 3 Figure 1 illustrates the locations of the study areas.

Data and methodology

Data

We obtained transaction records, including residential housing prices, from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT). Although there are various housing types, in this study, we targeted apartments because they include full address information, which enabled us to discern neighborhoods and aggregate amenity variables. In addition, apartments are the predominant residential type of housing in South Korea (Ahn et al., 2020). Thus, apartment datasets can properly represent the spatial dynamics of housing prices in the four metropolitan cities.

The datasets used in this study include various control variables regarding residential housing characteristics, e.g., unit areas, seasonal transaction periods, proximities to the local environmental amenities, and populations. These variables were retrieved from public databases (Statistics Korea, Statistical Geographic Information Service, the Korea Transport Database, and MLIT) and private real estate companies (Kookmin Bank real estate, Naver real estate, and Daum real estate). Data from the years 2018 and 2019 were aggregated, yielding 53,458, 56,606, 24,350, and 44,305 observations for Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, and Gwangju, respectively.Footnote 4

The aggregated datasets were categorized into four groups, i.e., housing characteristics, local amenities, local demographics, and seasonal dummies, as summarized in Table 1. Prior to fitting the datasets to our models, we cleaned the datasets, and the multicollinearity issue was assessed considering the variance inflation factor (VIF). In this process, some variables were dropped in the modeling procedure. In addition, four variables, i.e., transacted prices and three proximity variables, were transformed to logarithmic scale because these variables significantly depart from a normal distribution (Ahn et al., 2020). The descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study are given in Appendix A in the Supplementary Information.

A total of 17 variables were confirmed as hedonic variables, including two education variables, to appraise housing prices. The details of the variables are shown in Table 2, where the first column indicates the appellation of a variable denoted in our results. The second column describes the variable’s characteristics. Generally, the constructed variable set aligns with the existing literature on the assessment of housing prices (Ahn et al., 2020; An et al., 2023; Dai et al., 2023).Footnote 5

As proxies for education levels in neighborhoods, two education variables, i.e., Univ. grad. and Top school, were considered in this study.Footnote 6 The Univ. grad. variable reflects the ratio of university graduates among adults residing in a neighborhood, which has conventionally been utilized as a proxy for neighborhood education levels in relation to housing prices (Ahn et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2022; An et al., 2023). A higher level of education has served as a requisite credential for quality job opportunities in South Korea,Footnote 7 as discussed in “Study contexts”. As such, it is commonly believed that people with a higher level of education can afford greater housing costs based on their higher wages. Lin et al. (2022) found that university graduates are more likely to settle for higher housing costs to reside in urban cities with better public services and urban infrastructures. Accordingly, the Univ. grad. variable can capture the degree of educational levels in a neighborhood in relation to housing prices.

The Top school variable represents how many students are admitted to the nation’s most prestigious university, i.e., Seoul National University. Hundreds of universities and community colleges exist in South Korea; however, entrance to Seoul National University is highly competitive because admission has a higher potential for high social standing than admission to lower-ranked universities.Footnote 8 This implies that the number of entrants to Seoul National University can reflect the education fever and/or the quality of educational services in a given neighborhood. In this context, Chung (2015) used this variable, i.e., the admittance rate to Seoul National University, as a proxy for school quality in neighborhoods. Thus, our education variable, Top school, can represent the extent of education fever and/or the quality of educational services in a neighborhood.

We conduct a descriptive statistical analysis, using the key variables (Univ. grad. and Top school), to gain preliminary insights for the comparative analysis. We begin by examining the skewness and excess kurtosis of both education variables within each city. Furthermore, we test whether the two statistics conform to those expected under a normal distribution. Table 3 represents each education variable’s skewness, excess kurtosis, and corresponding test results in each city. Table 3 shows that all surveyed areas exhibit asymmetric distributions for both education variables. Educational contexts in neighborhoods are key determinants concerning property prices and housing purchases (Guo and Qian, 2021; Wang and Li, 2022). In this sense, the test results indicate that estimation disparities between HPMs and ML models can arise from asymmetric education levels within a city, as HPMs primarily capture linear trends (Schulz et al., 2020) against the nonlinearity of ML models (Fuster et al., 2022).

Next, we employ the \(t\)-test to compare mean values and the \(F\)-test to compare variances of the two education variables in order to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between cities (Yao et al., 2022). Table 4 summarizes the pairwise test statistics for each city, highlighting the heterogeneous characteristics of the education variables across all surveyed areas. Based on these preliminary insights, we treat each city as an individual experimental group (Rainio et al., 2024).

Hedonic price models

HPMs have served as the conventional approach to estimate residential housing prices (Chau and Chin, 2003; An et al., 2023). Most studies have utilized this linear method to identify hedonic variables’ marginal effects on housing prices (Hong et al., 2020; Ahn et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2023) due to its simple implementation and intuitive interpretability. The ordinary least squares (OLS)-based regression form is the representative model for HPMs. This study assessed housing prices based on HPMs and identified the financial premiums of hedonic variables in relation to housing prices. The mathematical formula of the OLS-based HPM in the log-linear formFootnote 9 (Gibbons et al., 2014; An et al., 2024) is expressed as follows:

where \({p}_{i}\) denotes the transacted price of an apartment unit \(i\) per square meter, \(c\) is the constant, and \(H\) is the number of hedonic variables, including housing characteristics, local amenities, and local demographics (\({x}_{{ih}}\)). In addition, \({d}_{{is}}\) denotes the seasonal dummy variables (spring, fall, and winter), and \({\beta }_{h}\) and \({\gamma }_{s}\) denote regression coefficients corresponding to hedonic variables (\({x}_{{ih}}\)) and seasonal dummies (\({d}_{{is}}\)), respectively, which are estimated using the OLS method. The residual term is denoted \({e}_{i}\).

Note that the housing unit prices potentially affect the prices of nearby housing units (Qiu et al., 2023); thus, housing prices are spatially correlated (Huang et al., 2017). To alleviate this spatial dependency issue (Ahn et al., 2020) and ensure the robustness of our results, we introduced the spatial lag regression (SLR) model in the assessment of housing prices. Here, a spatial lag term (\({Wy}\)) is input to the hedonic model. The model specification of the SLR is expressed as follows (Anselin, 2013):

where \(y\) represents the \(N\times 1\) vector of the log-transformed housing prices, \(\rho\) denotes the spatial lag parameter, which is estimated by minimizing the root mean squared error (RMSE) in the range between \(-1\) and \(1\), \(X\) represents the \(N\times \left(H+4\right)\) matrix of hedonic variables including three seasonal dummies, and \(\beta\) represents the \(\left(H+4\right)\times 1\) vector of regression coefficients. Finally, \(\varepsilon\) denotes the \(N\times 1\) vector of residuals, which is assumed to be homoscedastic, independent across observations, and distributed normally.

The spatial weight matrix \(W\) takes the \(N\times N\) matrix in the following row-standardized form:

where \(\tau\) and \(v\) denote two housing units’ locations, which can be specified by their longitudes and latitudes; thus, \({D}_{\tau v}\) is the distance between two housing units located in \(\tau\) and \(v\). In addition, \({D}_{{band}}\) is the distance band set by unity. However, the potential bias resulting from simultaneity issue must be addressed because the target variable \(y\) in Eq. (2) can be jointly estimated (Brueckner, 1998). Therefore, we implement SLR depending on the following mathematical formula, which can be obtained from Eq. (2), to remedy biased estimation (Brueckner, 1998; Ahn et al., 2020):

Machine learning algorithms

Regarding our core research questions, we employ the random forest (RF) and extreme gradient boost (XGBoost) models to assess housing prices. These models serve as appropriate alternatives to handle the nonlinearity inherent in our datasets based on their flexibility, which has been challenged to linear models (Dou et al., 2023; Swietek and Zumwald, 2023).

The RF model is an ensemble of decision trees that utilizes a number of predictors, i.e., trees, which can be described as a set of \({h}_{t}\left({X}^{d}\right)\), where \({h}_{t}\) represents a tree predictor corresponding to a tree \(t\), and \({X}^{d}\) is the matrix of the hedonic variables (including seasonal dummies). Here, each tree predictor estimates the log-transformed housing prices in this study. The RF model adopts the bootstrap methodFootnote 10 and out-of-bag estimationFootnote 11 in the training process, thereby providing robustness against outliers and unbiased estimations (Breiman, 2001). The final output of the RF model can be obtained by aggregating each estimated value of the tree predictors, i.e., \({h}_{t}\left({X}^{d}\right)\), as follows:

where \(T\) denotes the number of tree predictors, and \({X}^{d}\) is the \(N\times \left(H+3\right)\) matrix of the hedonic variables used to appraise housing prices.

The XGBoost model employs a growing tree in accordance with feature splits and additive tree structures. The addition of a single tree in each iteration supplements the previous predictor’s estimation error. Following the iterations correcting residuals, the XGBoost model can enhance the predictive power incrementally (Chen and Guestrin, 2016). Based on decision rules, the XGBoost model utilizes tree structures \(f\), which map a score considering the variables’ characteristics to each leaf within each tree structure \({f}_{t}\). Given \(T\) trees, the XGBoost model obtains the estimated value \(\hat{y}\) by summing all scores assigned to the leaves in each tree. The XGBoost model attempts to minimize the following objective function, consisting of the loss function and regularization term as follows (Dou et al., 2023):

where \(\phi\) is a set of parameters, and \(l\) is the loss function that calculates the estimation errors. In addition, \(N\) is the number of observations, and \({\hat{y}}_{i}\) and \({y}_{i}\) are the estimated and real target values for single observation \(i\), respectively. \({\rm{\Omega }}\) is the regularization term that controls the complexity of the regression predictors (Chen and Guestrin, 2016), which improves generalization, and each \({f}_{t}\) corresponds to the structure of each tree.

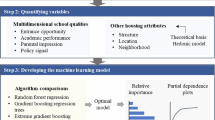

Experimental design

Two scenarios were considered in this study: (1) the emergence of unequal effects of the AI-based valuation and (2) its aggravation in housing price appraisals. The unequal effect of the AI-based valuation model can be confirmed when the positive difference between the housing prices assessed by the AI model and the HPM is in the well-educated housing group, whereas the negative difference is in the less-educated housing group. In addition, the unequal effect is exacerbated if it satisfies the following scenario: the difference between values estimated by the AI model and HPM is statistically greater for well-educated housing groups compared to less-educated housing groups.

Before identifying the two scenarios, we first analyze whether local education levels are significantly associated with housing prices across all surveyed areas. This procedure incorporates two education variables in the HPM specifications, and we investigate their regression coefficients. In addition, the valuation models’ predictive power was checked in the assessment of housing prices. Here, we divided the entire dataset into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%) in each of the four cities. To discern the unequal effects of flexible models according to educational levels, we considered three cases: (1) training the model and assessing housing prices by controlling Univ. grad., (2) training the model and assessing housing prices by controlling Top school, and (3) training the model and assessing housing prices by dropping two education variables. After applying these cases to the four models, i.e., a series of HPMs and two ML models, we calculated the difference between the values estimated by the AI model and the HPM, i.e., \({\hat{y}}_{{AI}}-{\hat{y}}_{{HPM}}\).

Then, we sorted the differences in ascending order based on the level of education variable and aggregated lower and upper groups into 5, 10, and 20 percentiles, considering observations. Finally, we conducted \(t\)-tests for within each group and for between lower and upper groups. The \(t\)-test within each group validates the homogeneity between housing prices estimated by AI models and HPMs, and we employed the \(t\)-test between lower and upper groups to validate whether the differences in the housing prices estimated by the AI models and HPMs exhibit different patterns of percentile groups, i.e., education levels. The latter test was conducted to discriminate whether the discrepancy derived from the AI-based valuation model was exacerbated on average according to the neighborhood’s education level.

Results and discussion

Effects of local education levels on housing prices

Using a series of HPMs, we identified the effects of the hedonic variables on housing prices, focusing on two education variables, Univ. grad. and Top school. As shown in Table 5, the \(F\)-statistics appear significant, and the HPMs explain the variance in housing prices fairly well based on the adjusted R2 for all cases. Our key variables, i.e., Univ. grad. and Top school, are positively and significantly associated with housing prices in the four metropolitan cities when each variable is solely incorporated in HPMs. These results imply that the neighborhood’s education level and the quality of educational services have positive financial premiums relative to housing prices. These findings align with the results of previous studies, which found that education levels are positively linked to residential property prices (Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger, 2011; Wen et al., 2017; Ahn et al., 2020; An et al., 2023).

In addition, when both education variables were incorporated in a series of HPMs, they still exhibited significant relationships with housing prices. In other words, aside from the conventional education variable, i.e., Univ. grad., the additional Top school variable has significance in terms of explaining housing prices. Accordingly, we confirmed that higher quality educational services contribute to an increase in housing prices (Nguyen-Hoang and Yinger, 2011; Wen et al., 2017), which further indicates that the two educational variables can jointly explain housing prices.

Assessment of housing prices

Figure 2 illustrates the predictive power of the models for the housing price appraisal task. In this procedure, we estimated the housing prices of the four cities for comparison. Each circle consecutively represents the RMSE value for the following four cases: (1) full variables, (2) omitting Univ. grad. from the full variables, (3) omitting Top school from the full variables, and (4) omitting both Univ. grad. and Top school from the full variables. The gray bar denotes the average RMSE value of the results derived from each model.

As shown in Fig. 2, the AI-based valuation models outperformed the HPMs in terms of the RMSE value. By comparing each model’s predictive power, we found that the RF and XGBoost models obtained lower RMSE values than those of the HPMs when assessing housing prices (regardless of the cases and the cities). These findings corroborate previous studies demonstrating that AI algorithms are more accurate than statistical models due to their flexibility in appraising housing prices (Chen et al., 2022; Lorenz et al., 2023).Footnote 12

We also examined how the housing prices estimated by the ML algorithms differ according to education levels using a partial dependency plot, which visualizes the marginal effects of variables on the estimated results (Lenaers and De Moor, 2023; Lorenz et al., 2023). Here, each education variable was divided into five groups with the same size, i.e., 20 percentile groups; thus, a total of 25 groups were created using the Univ. grad. and Top school education variables. Figure 3 shows the modalities of the flexible models when the education levels were controlled in the assessment of housing prices. We visualize the Daegu case when the RF model was used to assess housing prices, and the other cities exhibited a similar pattern.

First, the rightward circles tend to be saturated as the level of Univ. grad. increases, which implies that the ML model tends to estimate higher prices as the number of university graduates increases. Second, the upward circles also tend to be saturated as the degree of Top school increases, which indicates that housings in a neighborhood with higher education fever are estimated to be more expensive by the ML algorithm than neighborhoods with a lower education fever. Third, the right upper circle reveals that well-educated people are likely to reside in neighborhoods that have better educational services with high housing prices. In this context, we posit that the local education level is appreciated by housing prices even when using AI algorithms to assess housing prices.

Disparities in housing price appraisals

Following our experimental design, we explore the two scenarios regarding the unequal effects of AI-based housing price appraisals without controlling one or both education variables. Subsequently, this study conducts \(t\)-tests for the within-group and between lower and upper groups.Footnote 13 The results are summarized in Tables 6–9. In these tables, Panel A aggregates lower and upper groups based on the Univ. grad. variable according to 5th, 10th, and 20th percentiles when Univ. grad. and both Univ. grad. and Top school were omitted in the assessment of housing prices. Panel B aggregates lower and upper groups based on the Top school variable according to 5, 10, and 20 percentiles in the identical manner as Panel A. Each reported value indicates the average difference in each marginal group between the housing prices estimated by the AI algorithm and the HPM, and the \(t\)-test result is reported for within each group. We denote the \(t\)-test results between lower and upper groups along with their test statistics and significance. For example, Panel A.1 shows the difference between the assessed housing prices obtained by two models and the \(t\)-test results for within each group and for lower and upper groups with their test statistics, aggregated by the Univ. grad. variable when the housing prices were appraised without Univ. grad.

The \(t\)-test results for within each group exhibit different estimation patterns between the AI models and HPMs, as evidenced by their significance for the target cities. Overall, less-educated groups have significant negative difference values, whereas well-educated groups have significant positive difference values. These findings imply that the AI algorithm tends to estimate higher housing prices in well-educated neighborhoods than the HPMs. Conversely, housing prices in less-educated neighborhoods are depreciated considerably by AI algorithms compared with the prices appraised by the HPMs.Footnote 14 The \(t\)-test results for between lower and upper groups show that the average difference between housing prices, estimated by the AI algorithms and HPMs, is heterogeneous between lower and upper groups. In other words, these findings indicate that the unequal effects of the AI appraisal model are exacerbated in the assessment of housing prices in metropolitan cities.

The findings reveal that the ML model is asymmetric in favor of well-educated neighborhoods when appraising housing prices. The ML-based valuation model tends to highly appreciate housing properties in better educated and educating areas, thereby incurring the unequal effects across neighborhoods. Conversely, less-educated groups are penalized by ML algorithms in terms of the appraised housing prices. This result can be attributed to the flexibility of the ML algorithm because it better fits the transacted housing prices, which results in dispersed assessments (Fuster et al., 2022).

AI techniques provide cost benefits, managerial efficiency, and differentiated enterprise strategies to financial technology (FinTech) agents; thus, AI-based valuation systems have been actively adopted to improve business quality (Zhang et al., 2021; Poirier, 2024) and pricing precision (Cao et al., 2021). However, AI models can incur dispersed housing price assessments, which generate asymmetric estimations. In this context, when AI-based valuation systems become the dominant instrument against conventional econometrics in housing markets, the unequal effect derived from ML algorithms may present an obstacle to individuals seeking to move into well-educated neighborhoods with greater cost barriers, thereby aggravating housing costs.

Prospects regarding the increase in housing prices may encourage banks to increase loan activities (Li and Tahsin, 2021), although the opposite may also hold true. Thus, the unequal effects of AI algorithms can potentially penalize households in areas with lower education levels (Madrigano et al., 2015) by undervaluing their properties, resulting in reduced loan limits and hindering home ownership opportunities. Residents and prospective homebuyers in such areas are likely to have lower educational attainments and/or place less value on educational environments, possibly due to limited financial resources (Davidoff and Leigh, 2008; Rajapaksa et al., 2020). Therefore, disadvantaged people with limited housing options would face greater challenges in securing loan approval compared with their economically advantaged counterparts (Munnell et al., 1996; Ross and Tootell, 2004), ultimately decreasing the home ownership rate (Gabriel and Rosenthal, 2005; Larsen and Sommervoll, 2004). In addition, home ownership serves as a significant means of wealth transfer between generations, which can also function as a source of social inequality (Galster and Wessel, 2019). In this sense, using only ML algorithms to assess housing prices must be considered carefully because this can exacerbate wealth disparity between classes.Footnote 15

Discussion

Although established models and systems demonstrated their superiority in the given test cases, whether AI models can generate balanced and symmetric estimations in future real-world cases remains unclear (Makridakis et al., 2018). Previous studies have demonstrated that AI models produce asymmetric estimations across heterogeneous social groups (Desiere and Struyven, 2021; Friedler et al., 2021; Angwin et al., 2022; Fuster et al., 2022). Hence, this study identified the conditions under which AI-based property valuation models generate asymmetric price estimations in the context of housing price appraisals.

Compared to benchmarks, our scenarios revealed that a relatively precise model could generate unequal estimations with an appreciation for socially advantaged groups (well-educated neighborhoods) and a depreciation for socially disadvantaged groups (less-educated neighborhoods). This highlights the need for continuous validation and imbalance correction following the deployment of the model (Myllyaho et al., 2021) using traditional benchmarks (Ye et al., 2025).

Fuster et al. (2022) demonstrated the unequal effects of ML models in social groups’ default risk evaluations (derived from race and ethnic characteristics) by comparing ML and linear models; in such a case, some groups may be penalized or rewarded by sophisticated models, including ML algorithms. This outcome can be attributed to the flexibility mechanism of sophisticated models, which can indirectly capture the effect of unobserved and restricted variables (e.g., race) on the outcome (Fuster et al., 2022). When infrequent model updates compound such unequal estimations, an overreliance on seemingly precise models in decision-making processes can lead to an “uneven playing field” as the embedded asymmetric effects accumulate over time.

In this sense, indiscriminately employing AI models can threaten balanced housing price appraisal since housing price valuation systems are rarely updated due to illiquid property transactions (Gallin et al., 2021; Deppner et al., 2023). If unequal estimations are used in future housing appraisals without regular adjustments, property values in well-educated neighborhoods will be consistently over-appreciated, while those in less-educated areas will continuously experience under-appreciation, widening the price gap between educational groups (Choi and Green, 2022).

Relievable unequal effect

This study suggests an alternative approach to alleviate inequality in the assessment of housing prices. As demonstrated by our findings, the unequal effect regarding housing price appraisals is incurred when education variables are omitted; thus, we investigated whether the unequal effect can be mitigated if two education variables are controlled in the explanatory variable set. Here, we consider the case of Daegu using the RF model to appraise housing prices as the representative case because it obtained the highest accuracy in our comparisons.

Figure 4 shows the differences between the housing prices estimated by the AI algorithm and the HPM by aggregated groups. Here, the yellow line indicates the difference between the estimated housing prices omitting two education variables, i.e., Univ. grad. and Top school, in appraising housing prices, and the black line represents the discrepancy between the estimated housing prices with the full variables (including the two education variables). In addition, each circle represents the case of aggregating each group based on the Univ. grad. variable, and the diamonds represent each group aggregated by the Top school variable.

If a group is susceptible to the flexibility of the ML algorithm, then the discrepancy of the estimated housing prices moves away from zero, as indicated by the red line. As shown in Fig. 4, both tail groups are more affected by the flexible estimation when the housing prices are appraised without the education variables (yellow lines). In other words, the unequal effects are exacerbated in both marginal sides, i.e., less-educated and well-educated neighborhoods. However, when the education variables are incorporated in the housing price assessment, the black lines are much closer to the red line in all groups compared to the yellow lines. Given education variables, the inequality stabilizes because both models leverage the information regarding the effects of education levels on housing prices; thus, the inequality can be partly relieved, as shown in Fig. 4.

Conclusion

This study investigated the unequal effects of introducing AI algorithms to the housing price appraisal task, with a specific focus on four metropolitan cities in South Korea. The findings of our comparative analysis demonstrate that housing prices in less-educated neighborhoods are depreciated considerably by AI algorithms compared to HPMs. Conversely, the housing prices in well-educated neighborhoods are appreciated by the AI algorithms with favored valuations. In addition, the discrepancy between lower and upper groups is exacerbated according to the local educational levels, which is caused by the flexibility of ML algorithms.

The findings of this study have important implications for decision makers. First, when the valuation models are constructed using AI algorithms, to maintain fairness in the assessment of housing prices, agents must consider variables that potentially induce inequality in their modeling procedure. Second, minute and targeted regulatory policies are required to manage the negative externalities derived from utilizing AI models in the assessment of housing prices. Specifically, FinTech agents must validate whether their AI-based valuation systems have asymmetry that results in asymmetric housing price appraisal.

In this study, we primarily focused on apartment buildings due to their dominance in the target study areas. Nonetheless, our research framework, which scrutinizes the unequal effects of AI models, can be extended to other types of housing or other regions. In addition to the education variables considered in this study, other factors that may potentially contribute to residential segregation or social exclusion warrant further investigation. Environmental amenities, such as air quality and urban greenery, can play a significant role; therefore, future research should expand the current research scope to address environmental inequalities across cities. Furthermore, future studies can extend the current research framework by tracking individuals’ educational levels to explore the micro relationship between educational achievements and housing affordability. Concurrently, future studies can consider effective training and modeling strategies to alleviate the tradeoffs between increasing precision and unbalanced pricing when using AI models for the housing price appraisal task.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Korean society has traditionally respected the need and desire for learning, and this tradition is considered the driving force in making Korean society an education stronghold (Ministry of Education, 2015).

According to Statista (2024), households in South Korea with a monthly income of eight million Korean won (5848.80 US dollar) or more spent an average of 671,000 Korean won (490.57 US dollar) per month on their child’s private education, whereas those with a monthly income of two million Korean won (1462.20 US dollar) or less spent an average of 136,000 Korean won (99.43 US dollar) per month for private education services. The average monthly expenditure for private education per student was approximately 431,000 Korean won (315.10 US dollar) (Statista, 2024).

For example, the high school entrance mechanism relies on the residential location; thus, the residence site is a key consideration for admission to the preferred school (Chung, 2015). This can contribute to forming different local educational environments and increased housing prices, along with a higher demand for quality school districts (Wen et al., 2017).

We selected these metropolitan cities as the survey areas, excluding Seoul, as previous studies have already explored the relationship between educational factors and housing prices in Seoul (Chung, 2015; Yi et al., 2017; Park and Lee, 2021). Furthermore, housing transactions occur less frequently in these cities due to their market sizes compared to Seoul, resulting in information disparities in housing markets (Pu et al., 2022). These conditions are suited for identifying disparities in housing price appraisals through comparative analysis across cities.

Although our aggregated datasets include the number of high schools, this variable was dropped in the final models considering the model fitness and VIFs.

The enrollment rate at universities was 52.5% in 2000 and has constantly increased to 76.2% in 2023 (Statista, 2023).

Graduates from higher-ranked universities also tend to have higher housing affordability in the long run (Li et al., 2017).

Given the training dataset \(S\), the RF model forms a series of bootstrapped training sets \(\{{S}_{1},\ldots ,{S}_{t},\ldots ,{S}_{T}\}\) by allowing replacement. In addition, a subset of the explanatory variables is selected randomly to train the tree predictor \({h}_{t}({X}^{d})\).

After bootstrapping, \({h}_{t}({X}^{d})\) estimates the target values using the other bootstrapped training set, which has yet to be used for training (out-of-bag).

We investigated the predictive power of the deep neural network (DNN) models as summarized in Appendix B in the Supplementary Information. The two tree-based ML models still overwhelm the other models across all the cases (Borisov et al., 2023; Shwartz-Ziv and Armon, 2022; Jafary et al., 2024; Yoshida et al., 2024); therefore, our main discussion focuses on ML models instead of DNN models.

We sorted the differences according to the education level variable in ascending order and aggregated each group based on the percentile over the total observations. Thus, a lower percentile group indicates a less-educated group, and the higher percentile group indicates a higher education level.

Univ. grad. has weak evidence for Busan in terms of unequal effects on housing prices; however, the unequal effects and aggravation of those effects clearly appear in the case of Top school.

Previous studies have found that (large) discrepancies in housing prices across generations over time can be the source of housing inequality between classes (Larsen and Sommervoll, 2004). In addition, the unequal effects, e.g., income inequality, are fueled by high housing prices and the social group’s low housing affordability (Zhang et al., 2016).

References

Ahn K, Jang H, Song Y (2020) Economic impacts of being close to subway networks: a case study of Korean metropolitan areas. Res Transp Econ 83:100900

An S, Ahn K, Bae J, Song Y (2024) Economic impacts of a subway system: exploring local contexts in a metropolitan area. Res Transp Bus Manag 56:101188

An S, Jang H, Kim H, Song Y, Ahn K (2023) Assessment of street-level greenness and its association with housing prices in a metropolitan area. Sci Rep 13(1):22577

Angwin J, Larson J, Mattu S, Kirchner L (2022) Machine bias. In Ethics of data and analytics. Auerbach Publications, 254–264

Anselin L (2013) Spatial econometrics: methods and models (Vol. 4). Springer Science & Business Media

Baur K, Rosenfelder M, Lutz B (2023) Automated real estate valuation with machine learning models using property descriptions. Expert Syst Appl 213:119147

Bayer P, Ferreira F, McMillan R (2007) A unified framework for measuring preferences for schools and neighborhoods. J Polit Econ 115(4):588–638

Bénabou R (1994) Human capital, inequality, and growth: a local perspective. Eur Econ Rev 38(3–4):817–826

Berry CR, Glaeser EL (2005) The divergence of human capital levels across cities. Pap Reg Sci 84(3):407–444

Borisov V, Broelemann K, Kasneci E, Kasneci G (2023) DeepTLF: Robust deep neural networks for heterogeneous tabular data. Int J Data Sci Anal 16(1):85–100

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45(1):5–32

Brueckner JK (1998) Testing for strategic interaction among local governments: the case of growth controls. J Urban Econ 44(3):438–467

Bussmann N, Giudici P, Marinelli D, Papenbrock J (2021) Explainable machine learning in credit risk management. Comput Econ 57(1):203–216

Cao L, Yang Q, Yu PS (2021) Data science and AI in FinTech: an overview. Int J Data Sci Anal 12(2):81–99

Chang YC, Mastrangelo C (2011) Addressing multicollinearity in semiconductor manufacturing. Qual Reliab Eng Int 27(6):843–854

Chau KW, Chin TL (2003) A critical review of literature on the hedonic price model. Int J Hous Sci Appl 27(2):145–165

Chen M, Liu Y, Arribas-Bel D, Singleton A (2022) Assessing the value of user-generated images of urban surroundings for house price estimation. Landsc Urban Plan 226:104486

Chen T, Guestrin C (2016) Xgboost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. Association for Computing Machinery, 785–794

Choi JH, Green RK (2022) The heterogeneous effects of interactions between parent’s education and MSA level college share on children’s school enrollment. J Hous Econ 57:101843

Chung IH (2015) School choice, housing prices, and residential sorting: empirical evidence from inter-and intra-district choice. Reg Sci Urban Econ 52:39–49

Dai X, Felsenstein D, Grinberger AY (2023) Viewshed effects and house prices: identifying the visibility value of the natural landscape. Landsc Urban Plan 238:104818

Davidoff I, Leigh A (2008) How much do public schools really cost? Estimating the relationship between house prices and school quality. Econ Rec 84(265):193–206

Deppner J, von Ahlefeldt-Dehn B, Beracha E, Schaefers W (2023) Boosting the accuracy of commercial real estate appraisals: an interpretable machine learning approach. J Real Estate Financ Econ 71:1–38

Desiere S, Struyven L (2021) Using artificial intelligence to classify jobseekers: the accuracy-equity trade-off. J Soc Policy 50(2):367–385

Dittrich K, Neuhaus DA (2023) Korea’s ‘education fever’ from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first century. Hist Educ 52(4):539–552

Dou M, Gu Y, Fan H (2023) Incorporating neighborhoods with explainable artificial intelligence for modeling fine-scale housing prices. Appl Geogr 158:103032

Fitzpatrick T, Mues C (2016) An empirical comparison of classification algorithms for mortgage default prediction: evidence from a distressed mortgage market. Eur J Oper Res 249(2):427–439

Friedler SA, Scheidegger C, Venkatasubramanian S (2021) The (im)possibility of fairness: different value systems require different mechanisms for fair decision making. Commun ACM 64(4):136–143

Fuster A, Goldsmith‐Pinkham P, Ramadorai T, Walther A (2022) Predictably unequal? The effects of machine learning on credit markets. J Financ 77(1):5–47

Gabriel SA, Rosenthal SS (2005) Homeownership in the 1980s and 1990s: aggregate trends and racial gaps. J Urban Econ 57(1):101–127

Gallin J, Molloy R, Nielsen E, Smith P, Sommer K (2021) Measuring aggregate housing wealth: new insights from machine learning. J Hous Econ 51:101734

Galster G, Wessel T (2019) Reproduction of social inequality through housing: a three-generational study from Norway. Soc Sci Res 78:119–136

Gama J, Žliobaitė I, Bifet A, Pechenizkiy M, Bouchachia A (2014) A survey on concept drift adaptation. ACM Comput Surv 46(4):1–37

Gibbons S, Mourato S, Resende GM (2014) The amenity value of English nature: a hedonic price approach. Environ Resour Econ 57:175–196

Gunnarsson BR, Vanden Broucke S, Baesens B, Óskarsdóttir M, Lemahieu W (2021) Deep learning for credit scoring: Do or don’t? Eur J Oper Res 295(1):292–305

Guo Q, Qian H (2021) Negative human capital externalities in well-being: evidence from Chinese cities. Reg Stud 55(6):1046–1058

Hong J, Choi H, Kim WS (2020) A house price valuation based on the random forest approach: the mass appraisal of residential property in South Korea. Int J Strateg Prop Manag 24(3):140–152

Huang Z, Chen R, Xu D, Zhou W (2017) Spatial and hedonic analysis of housing prices in Shanghai. Habitat Int 67:69–78

Jafary P, Shojaei D, Rajabifard A, Ngo T (2024) Automated land valuation models: a comparative study of four machine learning and deep learning methods based on a comprehensive range of influential factors. Cities 151:105115

Jang M, Kang CD (2015) Retail accessibility and proximity effects on housing prices in Seoul, Korea: a retail type and housing submarket approach. Habitat Int 49:516–528

Jones R (2013) Education Reform in Korea. OECD: Economics Department Working Papers Report No. 1067

Kang Y, Zhang F, Peng W, Gao S, Rao J, Duarte F, Ratti C (2021) Understanding house price appreciation using multi-source big geo-data and machine learning. Land Use Pol 111:104919

Larsen ER, Sommervoll DE (2004) Rising inequality of housing: evidence from segmented house price indices. Hous Theory Soc 21(2):77–88

Lenaers I, De Moor L (2023) Exploring XAI techniques for enhancing model transparency and interpretability in real estate rent prediction: a comparative study. Financ Res Lett 58:104306

Li LH, Wu F, Dai M, Gao Y, Pan J (2017) Housing affordability of university graduates in Guangzhou. Habitat Int 67:137–147

Li S, Jiang Y, Ke S, Nie K, Wu C (2021) Understanding the effects of influential factors on housing prices by combining extreme gradient boosting and a hedonic price model (XGBoost-HPM). Land 10(5):533

Li Y, Tahsin S (2021) Home price appreciation and residential lending standards. J Econ Bus 114:105954

Lin X, Zhong J, Ren T, Zhu G (2022) Spatial-temporal effects of urban housing prices on job location choice of college graduates: evidence from urban China. Cities 126:103690

Lorenz F, Willwersch J, Cajias M, Fuerst F (2023) Interpretable machine learning for real estate market analysis. Real Estate Econ 51(5):1178–1208

Madrigano J, Ito K, Johnson S, Kinney PL, Matte T (2015) A case-only study of vulnerability to heat wave–related mortality in New York City (2000–2011). Environ Health Perspect 123:672–678

Makridakis S, Spiliotis E, Assimakopoulos V (2018) Statistical and Machine Learning forecasting methods: concerns and ways forward. PLoS ONE 13:e0194889

Malladi RK (2024) Application of supervised machine learning techniques to forecast the COVID-19 US recession and stock market crash. Comput Econ 63(3):1021–1045

McMillan ML, Reid BG, Gillen DW (1980) An extension of the hedonic approach for estimating the value of quiet. Land Econ 56(3):315–328

Ministry of Education (2015) Education, the driving force for the development of Korea. https://www.kdevelopedia.org/Resources/view/--05201706180147997.do. Accessed Jun 06 2024

Munnell AH, Tootell GM, Browne LE, McEneaney J (1996) Mortgage lending in Boston: interpreting HMDA data. Am Econ Rev 86(1):25–53

Myllyaho L, Raatikainen M, Männistö T, Mikkonen T, Nurminen JK (2021) Systematic literature review of validation methods for AI systems. J Syst Softw 181:111050

Nguyen-Hoang P, Yinger J (2011) The capitalization of school quality into house values: a review. J Hous Econ 20(1):30–48

O’Brien RM (2007) A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant 41:673–690

Oh SJ (2007) Academic research in Korea. Nat Mater 6(10):707–709

Paleyes A, Urma RG, Lawrence ND (2022) Challenges in deploying machine learning: a survey of case studies. ACM Comput Surv 55(6):1–29

Park J, Lee S (2021) Effects of private education fever on tenure and occupancy choices in Seoul, South Korea. J Hous Built Environ 36(2):433–452

Poirier G (2024) Using AI to help create a fintech game-changer. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2024/01/19/using-ai-to-help-create-a-fintech-game-changer/?sh=5bf3b4da794c. Accessed Jun 06 2024

Pu G, Zhang Y, Chou LC (2022) Estimating financial information asymmetry in real estate transactions in China-an application of two-tier Frontier model. Inf Process Manag 59(2):102860

Qiu W, Li W, Liu X, Zhang Z, Li X, Huang X (2023) Subjective and objective measures of streetscape perceptions: relationships with property value in Shanghai. Cities 132:104037

Rainio O, Teuho J, Klén R (2024) Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning. Sci Rep 14(1):6086

Rajapaksa D, Gono M, Wilson C, Managi S, Lee B, Hoang VN (2020) The demand for education: the impacts of good schools on property values in Brisbane, Australia. Land Use Policy 97:104748

Ross SL, Tootell GM (2004) Redlining, the Community Reinvestment Act, and private mortgage insurance. J Urban Econ 55(2):278–297

Schulz MA, Yeo BT, Vogelstein JT, Mourao-Miranada J, Kather JN, Kording K, Richards B, Bzdok D (2020) Different scaling of linear models and deep learning in UKBiobank brain images versus machine-learning datasets. Nat Commun 11:4238

Shaik M, Gulhane RD (2023) Power of moment‐based normality tests: empirical analysis on Indian stock market index. Int J Financ Econ 28(3):2989–2997

Shi J, Luo D, Wan X, Liu Y, Liu J, Bian Z, Tong T (2023) Detecting the skewness of data from the five-number summary and its application in meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res 32(7):1338–1360

Shwartz-Ziv R, Armon A (2022) Tabular data: deep learning is not all you need. Inf Fusion 81:84–90

Statista (2023). Enrollment rate at universities in South Korea from 1980 to 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/629032/south-korea-university-enrollment-rate/. Accessed Jun 06 2024

Statista (2024). Average monthly expenditure on private education per student in South Korea in 2023, by household income (in 1,000 South Korean won). https://www.statista.com/statistics/642524/south-korea-spending-for-private-education-by-household-income/. Accessed Jun 06 2024

Sung M, Ki J (2023) Influence of educational and cultural facilities on apartment prices by size in Seoul: Do residents’ preferred facilities influence the housing market? Hous Stud 38(5):814–840

Swietek AR, Zumwald M (2023) Visual Capital: evaluating building-level visual landscape quality at scale. Landsc Urban Plan 240:104880

Tang LR, Kim J, Wang X (2019) Estimating spatial effects on peer-to-peer accommodation prices: towards an innovative hedonic model approach. Int J Hosp Manag 81:43–53

Tchuente D, Nyawa S (2022) Real estate price estimation in French cities using geocoding and machine learning. Ann Oper Res 308(1–2):571–608

Wang J, Li G (2022) Pursuing educational equality and divergence in the housing market: How do educational equality policies affect housing prices in Shanghai? Cities 131:104001

Wen H, Xiao Y, Hui EC, Zhang L (2018) Education quality, accessibility, and housing price: does spatial heterogeneity exist in education capitalization? Habitat Int 78:68–82

Wen H, Xiao Y, Zhang L (2017) School district, education quality, and housing price: evidence from a natural experiment in Hangzhou, China. Cities 66:72–80

Wooldridge JM (2015) Control function methods in applied econometrics. J Hum Resour 50(2):420–445

Yang J, Soltan AA, Clifton DA (2022) Machine learning generalizability across healthcare settings: insights from multi-site COVID-19 screening. NPJ Digit Med 5(1):69

Yao Q, Li R, Song L (2022) Carbon neutrality vs. neutralité carbone: a comparative study on French and English users’ perceptions and social capital on Twitter. Front Environ Sci 10:969039

Ye Y, Pandey A, Bawden C, Sumsuzzman DM, Rajput R, Shoukat A, Singer BH, Moghadas SM, Galvani AP (2025) Integrating artificial intelligence with mechanistic epidemiological modeling: a scoping review of opportunities and challenges. Nat Commun 16(1):1–18

Yi YJ, Kim EJ, Choi EJ (2017) Linkage among school performance, housing prices, and residential mobility. Sustainability 9(6):1075

Yoshida T, Murakami D, Seya H (2024) Spatial prediction of apartment rent using regression-based and machine learning-based approaches with a large dataset. J Real Estate Financ Econ 69(1):1–28

Zhang C, Jia S, Yang R (2016) Housing affordability and housing vacancy in China: the role of income inequality. J Hous Econ 33:4–14

Zhang Y, Chen J, Han Y, Qian M, Guo X, Chen R, Xu D, Chen Y (2021) The contribution of Fintech to sustainable development in the digital age: ant forest and land restoration in China. Land Use Pol 103:105306

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by (i) the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-16067531) and (ii) Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund (Of 2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. A.: Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualization. Y. S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—original draft, Supervision. H. J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing— original draft, Supervision. K. A.: Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, S., Song, Y., Jang, H. et al. Asymmetric impacts of artificial intelligence on housing price valuation across education levels. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1884 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06153-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06153-4